Honeyville

Daisy Waugh

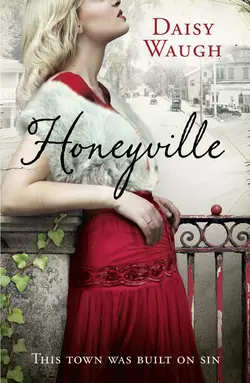

A hooker. A mistress. A murder. This town was built on sin.The town of Trinidad, Colorado was a tough place to be a woman in 1913. But it was the best place in the West to find one, if you had the cash.Honeyville, they used to call it.A murder throws Inez and Dora together – two women from opposite sides of town, in a town built for men. Against all odds, the well born girl and the high class hooker are drawn together in friendship…But this is a town that is rotten to the core, and beyond the rustling of silk skirts, the dancing and laughter, deadly unrest is building…Welcome to Honeyville – a town living by its own rules, where nothing is quite as it seemsA STORY INSPIRED BY A LOST CHAPTER IN AMERICAN HISTORY

HONEYVILLE

DAISY WAUGH

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 77–85 Fulham Palace Road Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Publishers

Copyright © Daisy Waugh 2014

The following are copyright lines to be used as applicable

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2014

Cover design by Becky Glibbery. Cover photographs © Sarah Ann Wright / Trevillion Images (woman); Ilina Simeonova / Trevillion Images (clothing); akg-images (street scene); Shutterstock.com (http://Shutterstock.com) (railing, pillar)

Daisy Waugh asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

The Nice People of Trinidad © Max Eastman published in The Masses July 1914 reprinted with permission of the Estate of Yvette Eastman.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007431779

Ebook Edition © November 2014 ISBN: 9780007500406

Version 2014-09-24

PRAISE FOR DAISY WAUGH (#uf0dd83b0-f101-590f-aa7e-a8a3236d793b)

‘The delicately constructed plot keeps you guessing until the end’

TLS

‘Unputdownable’

Daily Mail

‘Dazzlingly evoked’

Sunday Times

‘Gripping … powerful, evocative’

The Lady

‘A gripping, bittersweet love story’

Sunday Times

‘Impeccably researched and beautifully written’

Daily Mail

‘Daisy Waugh delivers her engaging tale with wit and a real lightness of touch’

Literary Review

‘Written in deft, engrossing prose, this story is dizzy with glamour and heartbreak’

Easy Living

Wilson, Jenny Wilson

This book is for you.

Contents

Title Page (#ub6ede4f5-590b-57bd-a4fc-2669b17b4b87)

Copyright (#u86e39629-15f4-515e-bdf2-6d0f9eaff6d4)

Praise for Daisy Waugh

Dedication (#u328041e8-9146-570e-b6ba-d71f94c29833)

1

2

3

4 (#u8857bd6c-8411-52c5-bf68-ef91d418075d)

5 (#ucec3951e-a7fd-5490-bcdd-e9d3c5d7312f)

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

Acknowledgements

Read on for more from Daisy Waugh (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep reading… Last Dance With Valentino

Keep reading… Melting the Snow on Hester Street

About the Author

Also by Daisy Waugh

About the Publisher

1 (#uf0dd83b0-f101-590f-aa7e-a8a3236d793b)

April 1933 Hollywood, California

I saw Max Eastman last night. He turned up at dinner very late, apologizing to us all as if the evening had been on hold for his arrival, and it occurred to me how lonesome it must be to shine the way Max does, to feel that you can never simply slide into a room and sit down. I don’t think he knows any other way to behave, except as the star of the show.

He arrived with a little writer friend – one of these East Coast novelists, trying to recoup a living from the studios. I don’t remember his name. There were twenty-five or so places laid at the table and I had no idea Max was joining us. Our hostess never mentioned it – I imagine because she wasn’t aware of it herself, until he walked through the restaurant door. Max Eastman is quite a celebrity, after all. And we do love a celebrity in this town.

When he loped into the room last night, I’ll be honest: my heart stopped. And this morning, when I opened my eyes, my face was covered with tears. I’ve never experienced it before – to wake, from crying. Had I been dreaming? I can’t remember. But I woke with a hundred images swimming through my head. Of Trinidad, Colorado, as it was almost twenty years ago. Of Xavier, as he was then. Of myself. Of Max and Inez as they were together; and the blood drying on the old brick pavements.

I still have the letter she wrote to him, its envelope spattered in Trinidad’s blood. When he loped into the room I felt many things: shock, delight, anger, affection, regret … and an image of the damn letter came to mind, yellow with age, brown with blood, nestling at the bottom of my jewel box. I felt ashamed. I should never have read it. I should have sent it on to him twenty years ago.

There was an empty place beside me at the long res- taurant table, and Max flopped himself into it with the same long-limbed, bashful elegance that was ever his.

‘Is it taken?’ he asked, though he’d already pulled back the chair.

‘Please!’ I said. ‘Sit!’ But I didn’t look at him directly. I was embarrassed. Either he would recognize me or he wouldn’t, and I wasn’t prepared for either.

Max made himself comfortable. He took the napkin from his empty plate and dropped it still folded onto his lap. He reached for the wine and sloshed it into both our glasses. He had been at the theatre, he explained, having sat through what was ‘possibly the lousiest play I’ve seen all year. And I only went out of loyalty. Which is always a mistake, isn’t it? Now I shall have to think of something encouraging to say about the damn thing … And I’m terribly fond of the writer, so God knows, I’ll have to come up with something …’

He asked if I had seen the play. I told him not, although I had heard good things spoken of it. ‘Well don’t!’ he cried. ‘If your life depends on it.’ And he proceeded to pull the wretched thing apart.

‘Max, old chum!’the East Coast novelist shouted at him across the table. ‘Forget about the darned play, won’t you? I’ve been telling the guys about your adventures in Marmaris. Why don’t you tell them yourself?’

‘Not Marmaris,’ Max said, looking pained. ‘I was in Büyükada.’ He pronounced it Buy-u-khad-a with the soft notes and little hisses, like a man who knew what he was about.

He had just returned from a week in Buy-u-khad-a, he explained, visiting with his old friend-in-exile, Leon Trotsky.

‘I’m amazed he’s still alive,’ the novelist said. ‘It can only be a matter of time before Stalin sends his people to take a pop.’ He made a limp white pistol shape of his hand.

And Max was off. It was his favourite topic: if not the domestic particulars of Trotsky’s new life in Turkey (which fascinated us trivial Hollywood folk), then the failure of communism, the evil of Stalin, the tragedy of post-revolution Russia. His trip to Büyükada had obviously been a failure.

‘It was quite a trek, after all. To come from Antibes, and I came with one single object in mind: to offer comfort to my old friend. Because he simply exists out there, you know? Plotting and brooding – waiting. It’s rather pathetic. One ear out for the pop.’

‘Pop,’ the novelist said. ‘Awful.’

‘Last time I laid eyes on the fellow we were in Moscow!’ Max continued. ‘Stalin was a nobody – a booby. A nothing. It was Leon who held the future in his hands … We believed in a new world … We were friends!’ Max paused. He fiddled with his napkin, furrowed his brow and I don’t suppose there was a person at the table who didn’t want to stretch across and smooth it for him. ‘Do you know,’ he said at last, ‘in all the week he and I spent together in Büyükada, Leon didn’t ask me a single question about my life.’He looked around at the table. ‘Isn’t that rather extraordinary?’

The conversation turned back to movies. (You can’t keep the conversation from movies for long in this town.) They were discussing the special effects in King Kong but I couldn’t contribute. After a moment or two, Max turned to me: ‘I’m guessing you and I may be the only people in this town who haven’t yet watched it, right?’

‘I think so,’ I smiled.

And then, finally, came the pause I suppose I had been waiting for. He took up his wine glass, and slurped from it in a show of nonchalance – not for me, but for everyone else. He leaned in close.

‘We’ve met before, Dora,’ he said.

‘Well of course we have, Max,’ I said, maybe just a half-second late. I had almost lulled myself into imagining the danger was passed. I smiled into his honest eyes, until he blinked. ‘Don’t tell me you have only now remembered?’

‘Certainly not,’ he said. ‘I spotted you at once! Why do you think I made such a beeline for the seat?’

‘It was the only one that was empty.’

He laughed, and shook his head. ‘You know, you don’t look a day older,’ he said.

And I said – the difference being that, in his case, except for the grey in his hair, it was true: ‘Neither do you, Max. Not a day older. You must have a portrait in an attic somewhere.’

‘Ha! Yes. I think maybe we both do. Gosh – but it’s terrific to see you, Dora. I mean … Don’t you think so?’ He sounded uncertain – as uncertain as I felt. ‘It’s too incredible! Here we are. Still standing. After all these years.’

‘Here we are,’ I repeated. ‘Still standing!’

‘Oh, but you must know I recognized you, Dora!’ He sounded a little petulant. ‘How could I possibly not?’

‘Well, I recognised you, of course. But you’ve gotten so famous since. I see your photograph.’ I smiled at him. ‘I guess I had the advantage.’

‘I would have greeted you as soon as I sat down. But then when you didn’t acknowledge me …’ He looked so tactful and tortured I had to struggle not to laugh. ‘I imagine that your particular situation … I mean, you look so terribly well, Dora. And I didn’t want to advertise the circumstances. Not that …’

‘Well, it would be nice if you didn’t stand on the table and shout the absolutely exact circumstances. One has to maintain a semblance of respectability. In these autumn years. Don’t you think? Even in Hollywood.’

‘Ha!’ he bellowed. ‘We surely do! Even in Hollywood!’ We laughed, and the long years since last we met seemed to fade away. ‘Well, I apologize,’ he said. ‘Please accept my apology. I was trying to be chivalrous. In my oafish way. But I’m a fool. I see it now.’

His hand was on the table top between us, long fingers busy rolling small crumbs of bread. So much anxious energy still! I felt a rush of affection for him. ‘Dear Max,’ I said. ‘Ever chivalrous.’ He grimaced, as well he might. But I had meant it. At least, I had meant it up to a point.

The novelist was yelling at him again – something emphatic about Charlie Chaplin. This time Max ignored him. He said: ‘You remember that crazy evening, Dora? The first night. It was anarchy – the striking miners had taken over the streets, and she was just buzzing with it all. I never saw a woman quite so alive. I remember looking at her that night – in the Toltec saloon – with the guns rattling out there on Main Street. She was beautiful. God. The woman of my dreams. I think I fell in love, right there and then.’ He laughed, shaking his head. ‘Don’t you remember? It was so damn exciting.’

Of course I remembered.

‘We truly believed the world was going to change. Or maybe not you, Dora. You’d seen too much of the world already. But during the siege – those ten crazy days – the rest of us: John Reed, God rest his soul, and me and Upton, and Inez of course – and all the reporters who piled in. We believed it! The world was actually going to change. Not just in Colorado …’

‘Ten Days That Shook the World.’

‘Ha! That’s right. Only imagine. John might have written it about our own, home-grown revolution.’

‘And thank God he didn’t,’ I said.

Max nodded energetically. In the intervening years, since returning from Russia, he had undergone a political volte-face that (according to the newspaper articles I read) had made him enemies on both sides. ‘It seemed possible, though, didn’t it? Colorado might have been just the beginning. It was …’ he paused, seeming to lose himself in thought. ‘You remember that Union chap, used to hang around Inez? Handsome as hell – I was rather jealous of him.’

‘Lawrence O’Neill.’ I laughed. ‘You didn’t need to be jealous of him, Max. Inez adored you. But yes, I remember him.’

‘Well he was another, turned up in Moscow later. Or, not in Moscow, actually. Dear God.’ He sighed. ‘That is … Last I heard, he was on his way to Solovki. Poor bastard.’

Solovki Labour Camp. Poor bastard, indeed. Even here in sunny California, the name Solovki resonates with everything that is cruel and broken in the New Russia. Lawrence O’Neill hadn’t crossed my mind in many years, but I was shocked – of course I was. Shocked and very sorry. I had been fond of him. ‘But didn’t he fight on the side of the revolution, just like the rest of you? What did he do so terribly wrong?’

Max looked at me, pityingly. He sighed with enor- mous weariness, appeared to hesitate, and then to think better of answering: ‘Oh God, but Dora,’ he said instead, brightening in a breath, ‘don’t you re- member darling Inez – and her terrible, dreadful, awful, appalling poem?’Grinning, he pulled back his shoulders, threw back his head: ‘For the strikers shall fight and they shall fall …’

‘Fight Freedom!’I cried.The words came to me as if I’d heard them yesterday. Max and I both remembered the poem perfectly and we finished it together with our fists aloft:

And they will rise

And they will call –

Fight Freedom!

’Til all

In America is fair

And the wind in the trees blows freedom to our streets and all

Good-Americans-take-care-and-pledge-forever-themselves-to-share …

She had gone out that morning with Max and a whole bunch of other reporters, to see the carnage for herself. The guards hadn’t allowed her into the camp, of course. But she had smelled it, seen it, felt it, and she was wild with righteousness, buzzing with the horror – crazier than I had ever seen her. We were in the Toltec saloon, a great gang of us, and from the hidden pocket of that pantaloon skirt she was so proud of (it celebrated her status as a ‘modern woman’), in front of all the cleverest in America (or so it seemed to us then: really it was a motley crew of poets and writers, intellectuals and newspaper columnists who had descended on Trinidad that week), Inez pulled out a sheet of paper. She announced that she had written a poem.

I tried to stop her. Max, with all his wit and chivalry, had tried to stop her, too. But Inez had written the damn thing. She would not be silenced.

Upton and the others had leapt on the opportunity to mock her, as Max had known they would. And as the evening progressed and more liquor was consumed, they began to chant poor Inez’s ridiculous poem aloud – and fall off their chairs with laughter – only to climb back onto them and begin chanting the wretched thing again. Inez took it on the chin. Bless her, I don’t think she cared a bit. She simply laughed and chanted along with them. ‘Y’all wait and see,’ she said. ‘It’ll catch on!’ … The smell of young, burning flesh still lingered on the prairie that night, and we knew it. But it was a wild night. I do believe we were never happier.

‘Fight Freedom!’ muttered Max, lost in his memories. He pushed his plate away and hunched over his long legs, deep in thought. ‘The last time I saw her, we had a most idiotic squabble,’ he said at last. ‘Like a couple of spoiled kids.’

I knew it already, from the letter. But I could hardly admit to that. ‘I’m not surprised,’ I said.

‘Hm?’

‘Well. I read the article you wrote.’

He hesitated. ‘You mean – the tea party piece?’

‘The one she helped you with.’

‘Oh. Gosh, no.’ Max laughed. ‘That wasn’t what we fought about.’

‘Oh, I think it was! She was mortified.’

‘Nonsense!’ He laughed again. ‘I was reporting a story, Dora! It was why I ever came to Trinidad in the first place. She understood that perfectly. Besides …’ He stopped, seemed once again to think better of whatever he was about to say. ‘I’d offered her a job on the magazine! She’d already sent on half her luggage!’

‘I know. I helped her to pack it. She was so excited.’

‘So don’t tell me,’ he laughed, ‘don’t tell me that kid didn’t know what she was about.’

‘I don’t think she had the faintest idea. I don’t think there was ever a “kid” more out of her depth.’

But he didn’t seem to hear. ‘We used it as a perching-place in our editorial meetings for years, you know. “Inez’s Packing Case”. We used to read submissions aloud and if something was truly, spectacularly bad, one of us would sort of launch something at the packing case, and shout out—’

‘Fight Freedom?’

‘Fight Freedom.’ He sighed again. ‘Well. It was funny back then, I guess. I still have that case somewhere. That’s right. The darned packing case arrived OK. But Inez? Never turned up. I wrote her. A bunch of letters.’

‘You wrote to her?’

‘After we printed the tea party piece.’ He had the grace, at last, to look at least a little shamefaced. ‘When she didn’t materialize in New York.’

‘Where did you send the letters?’

He shrugged. ‘I don’t remember. A post-office box? It’s been a long time, Dora.’

‘I never saw any letters. I wonder what became of them?’

‘Well – but never mind the letters, Dora.’ He leaned towards me. ‘For God’s sakes, never mind the letters. What became of her? That’s what I’ve been trying to ask you. What became of Inez? She simply disappeared.’

Max told me last night that he was here in Hollywood on one of his famous speaking tours. It’s why he has come to California. He is on an anti-communist speaking tour. I think. Or maybe an in-favour-of-poetry tour. He is still a poet, after all. Last I heard him speak, twenty years ago, he was stirring up revolution in the bloody coalfields outside Trinidad, Colorado. He was a fine speaker, too. Passionate. Persuasive.

In any case, they must be paying him well. They have put him up at the Ambassador for the entire week. And I am invited to lunch with him again on Friday, which is just five days away. I have told him about her letter. I have told him I will deliver it to him at last.

We have plenty to catch up on, I think.

2 (#uf0dd83b0-f101-590f-aa7e-a8a3236d793b)

August 1913 Trinidad, Colorado

Inez and I were in the drugstore on North Commercial the first time we met. Under normal circumstances, Trinidad being Trinidad and we ladies both knowing our place, we would never have exchanged a word. I would have gazed at her from beneath the rim of my extravagant hat and wondered how she could put up with the limits of her respectable life: and she would have looked at me, from beneath the rim of her more restrained affair and felt – what?

Pity, probably.

And irritation about the hat. I dressed flamboyantly, in silks and lace and satin. It’s what made me all but invisible to the good ladies on Main Street, and in the drugstore on North Commercial.

There were no other customers in the store that day. It was just the two of us. Behind the counter, Mr Carravalho was coaxing Inez into parting with a few extra dollars for a skin-freshening potion which, had I been inclined, I might have told her didn’t work, since I had already tried it myself. I might have told her that she didn’t need any such potion in any case. Her skin was quite fresh enough. Everything about her seemed, in my weary state, to sing with a freshness and vim long since lost to me.

I knew who she was. Inez Dubois cut quite a dashing figure in our small town. She worked at the library, though it was generally believed that she had money of her own, and no need to work. She was unmarried, so far as I knew, about 26 or 27 years old. She lived with her aunt and uncle, Mr and Mrs McCulloch, who owned one of the finest houses in Trinidad, and she ran around town in her own little Ford Model T motorcar.

She looked, I used to think, rather like a beautiful doll: with small, pointed nose, and thick golden hair and round grey eyes, and a tiny, slim body that seemed to fizz with energy and life. I had seen her driving up Main Street towards the public library, her scarf flowing behind her, just like Isadora Duncan. And I had seen her at the issue desk in the library. In fact, on several occasions, being an enthusiastic reader, I had presented her with novels to stamp (respectable novels, I should add, nothing like the filthy French novels dear old William used to send me. They didn’t stock those at the Carnegie Library of Trinidad). There were occasions when I sensed she might have liked to talk, if only to share her literary opinions of the novels I was borrowing. But she always stamped and returned them without quite looking my way.

So there we were in Carravalho’s Drugstore. I was waiting in line to stock up on the usual medications, essential for my trade. Mr Carravalho knew me well and would have a package already prepared for me, and I was in no hurry. Which was fortunate, since Inez Dubois was taking her time. She was fussing and flirting with Mr Carravalho, informing him of her dire need to buy ‘something’to refresh her look, what with the heat of this long summer.

It was a warm August evening – a beautiful evening, after a burning hot day, and it being a Friday, there was much noise and festivity on the street. Beneath the rattle of the tram and the Salvation Army choir, singing its lungs out on the corner of Elm Street, there came laughter and chatter in a score of different languages. It was the busy, noisy, carefree sound you only heard in Trinidad when the hot, dust-filled prairie wind had eased at last, and the sun had cooled, and the long working week was almost over. Miners from the neighbouring camps were piling in off the trolley cars, the brick-factory workers were making their way from the north end of town, and the distillery workers too, and the shop clerks, the farm hands and the cattlemen, the hustlers, the rangers: they were all on the streets that evening. Trinidad was wearing its glad rags. I remember reflecting that it would likely be a busy night at Plum Street.

The door to Mr Carravalho’s shop stood open as I waited, and I was content to linger there, catching the evening breeze, listening in on the chatter. But my tranquillity was interrupted suddenly by angry shouts from the street. There, framed by the store’s door and only a few yards from where I stood, three men had appeared as if from nowhere and, in the space of a second – the second it took for me to locate them – a violent fight had broken out between them.

I recognized all three men. Two were private detectives, from the notorious Baldwin-Felts detective agency, hired by the coal company to report on revolutionary activity among the workers. They and their like had been throwing their weight around Trinidad these past few months. They roamed the streets with handguns tucked under their shirts, picking fights when and wherever the fancy took them. Nobody seemed to stop them – except Phoebe, my boss and the proprietress of Plum Street. Phoebe didn’t ban many men from our parlour house, so long as they could stand the bill. So it was a measure of how brutish they were that she had banned entrance to all the Baldwin-Felts men. They had a reputation for violence, here and across Colorado – all over America in fact. Wherever employers hired them to harass and intimidate their workers.

The third man wasn’t much better. Another out-of-towner, come to Trinidad to make mischief. It was Captain Lippiatt, employed by the other side. He was a Union man. And I knew him, because he had visited us at the parlour house.

The three men stood chest to chest, eyeball to eyeball, in the middle of North Commercial, the spit flying in each other’s faces: three great bulls of male-hood, of pure and dangerous absurdity, it seemed to me. I had no wish to be anywhere near them. I slipped deeper into the store.

Inez, on the other hand, seemed unaware of the danger. She looked up from her skin-freshening packaging, and exclaimed, ‘Oh my!’ at such a volume that one of the spitting men – it was Lippiatt – paused momentarily to glance in.

‘Mr Carravalho, what are they doing?’ she asked, ‘What on earth do you suppose they’re arguing about?’

‘Union men,’ he muttered, shrinking a little behind his high wooden counter. ‘Hush up now, Miss Dubois. We don’t want them coming in here.’

‘All three are Union men?’ she asked, staring brazenly and without dropping her voice. ‘Then why are they fighting? You might have thought, after all the trouble they cause, they would at least have the decency to agree with one another.’

‘There’s a bunch of them in town this week,’ he replied. ‘Causing trouble. Some kind of delegation at the theatre. Talking about a strike—’

‘But they’re not all Union men,’ I interrupted. I wasn’t supposed to speak to the likes of Miss Inez Dubois. And nor she to the likes of me, except in a soul-saving, charitable capacity. Mr Carravalho looked shocked and embarrassed. They both did. But I persevered. It wasn’t that I had any special loyalty to the Union men (far from it), but it struck me as just plain ignorant to pretend that the battle on our streets was being fought by only one army. ‘One of them is, but the other two on the right are Baldwin-Felts men. You know that, Mr Carravalho. They’re coal company heavies. And it’s no good taking sides. Those men are as bad as each other.’

The fight, meanwhile, seemed to have disbanded. Lippiatt was gone. Even so, the two Baldwin-Felts detectives lingered. They crossed over to the far side of the street, looking cautiously about them, dust whipping round their boots. The Friday night crowd gave them plenty of space.

‘What are they doing?’ Inez asked.

It was hard to tell. They were leaning side by side of each other against a power post directly opposite us, hands resting on guns that poked ostentatiously from under their shirts. They gazed up the street towards the Union offices a few doors down, but nothing happened.

‘Well!’ Inez sighed. ‘Thank goodness for that! Is it over? I should be heading back.’

‘I’m sure you’re right, Miss Dubois,’ Mr Carravalho said. ‘It’s rather late for a lady to be trekking the streets. And on an evening like this. With the Union coming into town.’ He shot me a glance. ‘You hurry on home. Will you be taking that?’ he indicated the package still in her hand.

She looked down, remembering it. ‘Why yes!’ she cried, as if it was quite the boldest and happiest decision she had ever settled upon. ‘Sure, I’ll take it! Why not?’ And while Mr Carravalho wrapped it, she looked again, past me – through me, I suppose – to the street outside, where the two detectives had still not moved on.

‘They really ought to get going,’ she muttered, sounding nervous at last. She squinted a little closer, noticed the hands and guns. ‘Aunt Philippa says they are quite trigger-happy, these Union men. Do you think it’s safe to walk home?’

‘Pardon me,’ I said again, ‘but those aren’t Union men.’

She wasn’t listening. ‘It’s getting so rowdy, our little town,’ she muttered; I’m not certain which of us she was addressing. ‘I really don’t know why we have to put up with it. I begin to think – Oh! Oh Mr Carravalho! Oh my gosh—’

Captain Lippiatt had returned. He must have dashed directly into the Union office, snatched up the gun and turned straight back again. It explained, perhaps, why the Baldwin-Felts brutes had lingered. Perhaps they had known he was coming back.

Lippiatt charged towards them through the scattering crowd. ‘See now,’he shouted, ‘see now, cock chafers, see if you’ll repeat what you just said to me!’ He shook his gun at them. ‘Do you dare say it now, sons of bitches?’

In an instant the street emptied. On the corner of Elm Street, the choir stopped its singing and melted into the retreating crowd. But we were trapped. Directly before us, the detectives snatched up their own guns. Lippiatt was already beside them, his handgun poking at them. There was a confusing scramble of limbs, and more cursing, and then a shot. One of the detectives had been hit in the thigh.

Inez screamed. I put a hand on her shoulder to quiet her and she buckled beneath my touch. I let her fall.

This was not the first shooting I’d seen on the streets of Trinidad, nor would it be the last. But it was the closest I had ever been: so close I could swear I heard the soft thump of bullet as it hit his flesh. Afterwards some of the blood got onto my silk shoes, and no matter how well I scrubbed them, it would never shift.

There came another shot, this one from the handgun of the other detective. Lippiatt staggered back. Another shot, and he fell to the ground. And this I can never forget – the first detective stumbled forward and aimed his gun at Lippiatt as he lay helpless at his feet, and he shot him through the neck. Tore a hole through Lippiatt’s neck with the bullet. And then he shot him again, through the chest. That’s when the blood began to flow.

A couple of Union men appeared within moments, while we stood still, looking on, frozen with fear. They carried his body back into their Union lair, a thick trail of blood following them along the way. Lippiatt was dead. And I knew his name because last time he’d been in town, he paid me a visit at the Plum Street Parlour House. He was an Englishman. Or he had been English, once. Just as I had. It was the only reason I recalled him at all. Perhaps the only reason he chose me before the other girls. We didn’t talk about our Englishness in any case. Nor about anything else, come to that. Very taciturn, he was. Unsmiling. Smelled of the tanner – and my disinfectant soap. But they all smell of that. And he left without saying thank you. I can’t say I was sorry he was dead. But even so, it was a shock, to have been standing right there and seen it happen … and to remember (dimly) the feel of the man between my legs. And then there was Inez, collapsed on the floor at my feet. Poor darling.

I was shaken up. We all were. But Inez seemed to take the drama personally, as if it was her own mother who’d been slain before her eyes. She sat on the floor, her long blue skirt in a sober pool around her, and her little hat lopsided. She wouldn’t stand, no matter how Mr Carravalho and I, and finally Mrs Carravalho, tried to coax her. She simply sat and swayed, face as white as a ghost.

‘That poor man,’ she kept saying, with the tears rolling down her cheeks. ‘That poor, poor gentleman! One minute he was alive, right there beside me – he looked at me! Didn’t you see? Only a second before he looked at me … And now he is absolutely dead!’

3 (#uf0dd83b0-f101-590f-aa7e-a8a3236d793b)

Perhaps, while Inez is down there on the drugstore tiles, grieving the death of my old client, I should pause to explain something about our small town of Trinidad.

Forty years earlier it had been nothing: just a couple of shacks on the open prairie; a pit stop for settlers on the Santa Fe trail. Then came the ranchers and the cowboys, and then the prospectors. Elsewhere, they found iron and oil, silver and gold. Here, in Southern Colorado, buried deep in the rocks under that endless prairie, they found coal. It was the ranchers who settled in Trinidad. It was the coal men who made it rich. And in August 1913, our little town stood proud, a great, bustling place in the vast, flat, open prairie land. Trinidad boasted a beautiful new theatre, seating several thousand; an opera house as grand as its name suggests, a score of different churches and a splendid synagogue; there were numerous schools, two impressive department stores, a large stone library, and a tram that ran to the city from the company-owned mining settlements, or ‘company towns’ in the hills. There were hotels and saloons and dancing halls, and pawn shops and drugstores and stores selling knick-knacks of every kind, and a large brick factory, and a brewing factory and – because of all that – but mostly because of the coal, there were people in Trinidad from just about every country in the world.

In 1913, Trinidad was the only town in Colorado that tolerated my trade. Consequently, there existed on the west side of Trinidad – from that handsome new theatre, and on and out – a district a quarter the size of the entire town which was dedicated to gentlemen’s pleasure: saloons (uncountable) and – according to the city censor – at least fifteen established brothels. Which number, by the way, was the tip of the iceberg. It didn’t take into account the vast quantity of independent girls – the ‘crib’ girls, who operated from small single rooms, and who worked and lived together in shifts; nor the dance-hall girls, nor the pathetic ‘sign-posters’, who worked not in rooms but wherever they could: in dark corners, shoved up against walls behind the saloons.

For most of us (not perhaps the sign-posters) Trinidad was a good place to be a whore, and a good place to find one. Snatchville, they used to call it. Ha. And the punters came from far and wide. Prostitution wasn’t simply legal in ol’ Snatchville, it was an integral part of the city. There was a Madams’ Association – a hookers’ mutual society, if you like – so rich and influential it funded an extension of the trolley line into our red-light district, and the building of a trolley bridge. ‘The Madams’ Bridge’, folk called it: built by the whores, for the whores, although really the whole town benefited. It meant the men travelling down from the camps could be transported directly into our district, without getting lost along the way, or disturbing the peace of the better neighbourhoods. The Madams’ Association provided medical care and protection to the girls, too, so long as they were attached to a brothel. And a recuperation house, not a mile out of the city, where we could retire for a week or so, if we needed a break.

Trinidad was wealthy: cosmopolitan in its own provincial fashion, conservative and yet radical. It was new, and crazy, and busting with life. But for all that, it was only a small town.

From its centre, where North Commercial crossed Main (only a few yards from where Lippiatt was shot), the entire city was never more than a ten-minute walk away: the library, where Inez worked, the jail, the city newspaper, the City Hall. Everything was clustered around the same twenty or so blocks. From the red-light district in the west, with its saloons and dancehalls, to the ladies’ luncheon clubs, church halls, and elegant tearooms in the east, the distance was hardly more than a few miles.

The ladies of Trinidad spent their dollars in the same stores. We attended the same movie theatres. We washed the same prairie dust from our hands and clothes. And yet, it was as if we lived in quite separate realities; as if we couldn’t see one another. Only the men travelled freely between our two worlds.

Inez and I, living side by side in a small, dusty town in the middle of the Colorado prairie might, our entire lives, have brushed past one another on the sidewalk, at the grocery store, the drugstore, the library, the doctor’s waiting room, at our famous department store – and never once exchanged a glance or a word. Inez and I were as shocked as each other by the evening that followed Lippiatt’s death.

… I suppose, at this point I should also explain something about myself, too? I don’t much want to, and that’s the truth. But how in the world (the question begs) did an educated English woman, thirty-seven years old and the daughter of two Christian missionaries, find herself divorced, childless and working in an upmarket Colorado brothel? How indeed.

Well, because we all find ourselves somewhere, I guess.

It’s all anyone needs to know. There, but for the grace of God … This isn’t a story about me, in any case. It’s a story about Inez and Trinidad, and the war that came to Snatchville and tore us all apart.

So there Inez sat, or slumped, on the drugstore tiles. And there were Mr and Mrs Carravalho hovering around her, polite but, I sensed, with a hint of impatience. Outside, there was panic in the voices now, and anger too. The Carravalhos wanted to close up and get home as quickly as possible. But Inez, wrapped in her own horror, was oblivious to their concerns. I might have gone on my way, come back to the shop another day. I had plenty else to do, and I was meant to be working that evening. But Lippiatt’s blood was still slick on the street outside, and I didn’t much relish the idea of venturing into the angry crowd myself. Not yet.

Mrs Carravalho disappeared into the back of the shop and returned with brandy. A single serving, for Inez – until her husband sent her back for the bottle and three more glasses. I took mine, swallowed it down and felt better at once. Inez took only the daintiest of sips, and continued to whimper.

I told her she’d feel stronger if she drank the thing down in one. She looked at me directly, I think for the first time, and immediately did as I suggested. The alcohol hit the back of her throat and she shuddered. The three of us looked on, intrigued, as the brandy continued its internal journey, until at length she looked up at the three of us, considered us one by one, and grinned.

‘Thank you all so much. I think, perhaps …’ She belched, and I laughed. Couldn’t help it. She glanced at me again, uncertain whether she dared to laugh too, and decided against it. ‘I think I should probably head home.’

‘Excellent idea,’ Mr Carravalho said.

His wife looked at her doubtfully. ‘It’s set to turn pretty mean out there. You want my husband to escort you?’

‘No, no!’ Inez said, though she plainly did.

‘Well if you are certain,’ he answered quickly.

I took her empty brandy glass and placed it with my own on the counter. I said, ‘We can leave together if you like. Just until we’re through the craziness. It’ll be much quieter on the other side of Main Street.’

There was an embarrassed pause.

‘Well I’m sure I don’t think … Honey?’ muttered the wife, looking at me suspiciously. But Mr Carravalho was apparently too busy to notice. ‘I really don’t think,’ she muttered again.

‘What’s that dear?’ He was locking up, counting notes. Protecting the business.

Inez ignored them and turned to me. ‘Which way are you headed?’ she asked boldly, and immediately blushed. ‘That is to say, I am headed east. Perhaps. I mean, for certain, I am heading east. And I don’t know – if maybe we are headed in different directions?’

‘I dare say we are,’ I said. ‘But we can walk on up to Second or Third Street together. It’s sure to be quieter up there.’

Inez glanced through the window. The sheriff had arrived and an angry gaggle had mustered round his motor, making it impossible for him to get out. It looked menacing.

‘Well,’ she said at last, ‘if it’s all the same to you, I think that would be just daisy. Thank you.’ As she stood up, she seemed to totter a little. Carefully, eyes closed in concen- tration, she straightened herself. ‘Shall we get going?’

‘You know I really don’t think …’ Mrs Carravalho murmured yet again, sending baleful looks at her husband.

‘Well, unless you want me to leave you here alone,’ her husband snapped at last, ‘with all the trouble brewing and the store unguarded, and the week’s takings still in the register, and you, no use with a handgun …’

‘Well but even so,’ she was saying.

We left them squabbling and stepped out into the teeming street, Lippiatt’s blood still damp between the bricks at our feet.

We had hardly walked a half-block before she stopped, grasped hold of my shoulder.

‘Hey, what do you say we sit down?’ she said. Her face was whiter than ever.

‘You want something more to drink?’ Truth be told, I didn’t feel so hot myself.

She nodded.

We might have stopped at the Columbia Hotel, just across the street. Or at the Horseshoe Club, ten doors down. Or at the Star Saloon at the corner. There was no shortage of choice. But we stopped at the Toltec. At the moment she grasped hold of me, and I was convinced she might faint right away, it happened we were right bang beside its entrance. So we turned in, and plumped ourselves at a table at the end of the room, as far from the hubbub as possible.

The Toltec was plush and newly opened then; a saloon attached to a swanky hotel, both of which, I knew, were popular with visiting Union men. It was a saloon much like any other, maybe a little more comfortable. There was a high mahogany bar running the length of the room, an ornate, pressed-tin roof, still shiny with newness, and a lot of standing room. We sat beneath that shiny ceiling and ordered whiskey. A bottle of it. And for a while the bar was quiet.

‘Everyone’s out on the streets,’ the barman told us as we settled ourselves at the table.

‘Making trouble,’ Inez said.

‘Depends on your way of looking at things,’ muttered the barman.

We filled our glasses and turned away from him. ‘But you know everyone I know agrees,’ she told me, sucking back on her whiskey. (She may not have been accustomed to liquor, but I noticed she had taken a liking to it fast enough.) ‘These anarchists come into town with their crazy ideas, and then they infiltrate the camps and stir up the miners. The men were perfectly happy before the Unions came in. And now look where we are! Death on every doorstep! Murder at the drugstore!’

‘To Captain Lippiatt,’ I said, to shut her up. I didn’t want to talk politics – not with anyone, and least of all with her. ‘May he rest in peace.’

She stared at me, whiskey glass halted. ‘Captain Who?’ and then, ‘You know his name? You mean to say you knew him?’

‘Hardly very well. But yes, I guess knew him.’

‘How?’ And then, in a rush of embarrassment, and without giving me a chance to answer: ‘Oh gosh but never mind that!Did I tell you already – I work at the library. Do you ever go in there? You should. I’ll bet there are plenty books I could show you that you might enjoy.’

‘I love to read,’ I told her. ‘And I am often in the library. I’ve seen you in there before.’

‘It’s quite a thrill you know,’ she skipped on (I imagine the library was the very last thing she wanted to talk about). ‘I mean, once you get over the shock of it, and all. It’s quite a thrill to be here in this saloon. I’ve been walking past saloons all my life, never even daring to peep in. And now here I am,’ she beamed at me, ‘in a saloon! With you! It feels like the greatest adventure.’

‘I suppose it is,’ I said. ‘For you and me both.’

‘Do you suppose your friend Mr Lippiatt—’

‘Oh, I wouldn’t say he was a friend.’

‘No. But do you suppose he had a wife? Or children? Or anything like that? Maybe a mama. I think I should go visit them. Don’t you think I should?’

I laughed. ‘Whatever for?’

‘Whatever for? He and I, we looked at each other. Don’t you see the significance?’

‘Not really.’

‘Well, mine was probably the last human face, the last decent human face, not in the process of slaughtering him, which that poor gentleman ever laid eyes on. And then – Pop! He was dead.’ She sniffed. Picked up her glass. Glanced at me. ‘Y’know this is silly. Here we are, you and me, drinking in a saloooon together.’ She rolled the word joyfully around her mouth. ‘And I don’t even know your name. I am Inez Dubois, by the way.’

‘How do you do.’

‘I live with my aunt and uncle. Mr McCulloch. You’ve probably heard of him? Have you?’

‘No,’ I said automatically. Whether I had heard of him or not.

‘Mr McCulloch is my uncle.’

‘So you said.’

‘Well, he’s one of the old families. Ranching. Cattle. That’s where his money comes from. So he’s got no business with the coalmines, thank blame for that …’ She glanced at me. Already, her eyes were growing fuzzy with liquor. ‘Don’t you think so?’

‘It’s all the same to me.’

‘Even if the miners do get a fair wage. And nice homes and little yards and free schools and everything they could possibly ask for. Well, it’s all stirred up by the Unions now, isn’t it? And I would hate that. Just wouldn’t feel right, you know? To live off other people’s discontent. Whereas the ranchers aren’t like that. They’re altogether …’ She frowned. ‘Well, anyway, they’re not the same.’

Inez Dubois looked and behaved much younger than her age. She was twenty-nine years old, she told me that night (making her eight years my junior), the orphaned child of Mrs McCulloch’s sister, who died alongside Inez’s father in what Inez described as, ‘one of these train-track accidents’. She didn’t go into details, and I didn’t ask for them. Her parents died back in 1893, in Austin, Texas, and after the funeral Inez and her older brother Xavier were sent to Trinidad to live with their only living relation. The McCullochs had no children, and though Richard McCulloch was aloof and uninterested, his wife treated her nephew and niece as her own. Inez never moved out. Her brother Xavier, on the other hand, had left town some ten years previous, at the age of twenty-five, and though he wrote to Inez once a week, often enclosing a variety of books and magazines he believed might educate or amuse her, he’d not returned to Colorado since.

‘He’s in Hollywood now. Silly boy,’ Inez said, though by my calculation, he was a good six years her senior. ‘He’s making movies,’ she said. ‘Though I’ve never actually seen any, so I don’t suppose he really is. He says I would love it in Hollywood. It’s summertime – only cooler – a cooler summer, all year long. Sounds heavenly doesn’t it? Shall we go there together?’ She giggled. ‘After what happened today, I tell you I’m just about ready to leave this place. I wasn’t far off ready before. And now … Truthfully. I’m sick to death of it. Are you?’

‘Kind of …’ I laughed. It must have sounded more mournful than I intended.

She looked at me with her big, earnest eyes. She said, ‘You do realize, don’t you, that there are about a million questions I want to ask you. About everything. Only I guess I have a pretty good idea what it is you do.’She looked so uncomfortable I thought she might burst into tears again. I had to bite my lip not to smile. ‘And I don’t mean to pry. It’s probably why I’m yakking on like this. It just makes me nervous, that’s all. Because here we are, sitting here, and we’ve been through this terrible, awful thing together, when normally we wouldn’t even speak. And I was impolite to you in the drugstore, but you know I didn’t mean to be. I guess I just didn’t know any better. Because we can’t live more than a handful of miles apart and yet …’ She took a breath. ‘I don’t quite even know where to begin.’

‘Well you could begin,’ I said, ‘by asking my name.’

She opened her mouth—

‘And maybe even hushing up long enough to find out the answer.’

4 (#uf0dd83b0-f101-590f-aa7e-a8a3236d793b)

She discovered my name eventually. Though I’m not convinced she really registered it until some time later. I told her a little about myself – as little as I could – and watched her wide eyes watering, torn between outrage and pity.

‘You don’t need to feel sorry for me,’ I said, when her pitying expression was too much.

‘Oh but I don’t,’ she cried quickly, eyes sliding away.

‘After all, I am freer than most women and freer than any wife. I have money of my own. A wife doesn’t.’

‘Yes of course!’

‘A husband can beat and rape his wife and there is nothing she can do to prevent it. If a man beats me or rapes me, it is against the law. And even if it weren’t, here in Trinidad, we girls have friends who can make his life a misery. I have freedom. And one day,’ I told her, ‘when I have saved enough, I can stop this work altogether. And do what I have always planned to do—’

‘Yes?’ Inez asked, brightening. ‘Yes, and what is it?’

In truth the ‘plan’, if I could even call it such a thing, was no closer to fruition than it had been the first day I’d dreamed it up, seven or so years ago. I regretted mentioning it, and felt aggrieved with myself for having done so. But she wouldn’t let it go. She demanded to know what it was, my secret plan: what I might otherwise do that would save my wicked soul. I told her. I was a singer once.

Instant tears sprung. ‘A singer!Why, and you can be again!’ she cried. ‘You could sing at our own opera house! I just bet you could! You’re so dashing and beautiful and everything … I’ll ask Mr Haussman. He’s the manager. He’s quite an acquaintance of my uncle. I just bet you—’

‘But I don’t want to sing at the damn opera house,’ I snapped.

‘Well, of course you do!’

‘I am sick and tired of people looking at me—’

‘Even so …’

‘However, I admit it – I would love to teach others to sing.’

‘Well then!’ Inez was irrepressible: ‘You could start today! What’s stopping you?’

‘Plenty of things.’

‘Well? Name them!’

But I didn’t want to. I didn’t want to talk about my dreams. I didn’t need to be saved by her. ‘I don’t want to start today. I enjoy myself,’ I said. Or at any rate (I didn’t add), I used to. But a girl can have too much of a thing. ‘I earn good money. And I never have to cook or clean – or listen to any man bellyaching … or at any rate not for long. And then,’ I leaned in and winked, ‘well, they lay down their dollars. And then they fuck off. Out of my bed, out of my room. Out of my life.’

She gasped, as I had intended.

‘Better a whore than a wife,’ I said. ‘Any day.’

Inez was neither of course. She was a lady with a rich and indulgent aunt, who volunteered her time at the library. Inez could do whatever and go wherever she liked. It made my head spin to imagine it.

She was ‘looking for love’, she told me. (I could have told her to save herself the trouble.) Instead we spent much of the evening talking about that. Inez and her search for love. Her search for adventure. Her search for a bigger life. She was restless.

‘Aunt Philippa has almost despaired of me,’ Inez said with a hint of pride. ‘She’s utterly convinced I’m going to die an old maid. And I tell her – well of course I shan’t!But you know, Dora, I do begin to wonder myself sometimes. I know I look younger than I am. People always say I do. But I’m going to be thirty next birthday – it’s old. For a lady. Don’t you think?’ She glanced at me. ‘I mean to say – you probably … Maybe you—’

‘Oh, I already have a husband,’ I muttered. I hadn’t intended to confide in her. Certainly not. But there it was: the effect of her warmth, surprising me, inviting me to reciprocate. I had no close confidantes, and didn’t want any. But she was difficult to resist.

‘You do?’

‘Somewhere. I haven’t laid eyes on him in seven years or so. But I certainly had a husband. Until I woke up one morning … And there – he was gone!’ I looked at her astonished face, eyes filling with sorrow yet again, and I burst out laughing. ‘Inez,’ I declared – and I think by then I had almost come to believe it. ‘It was the best morning of my life!’

‘But why? Did he? Was he—’

‘A louse. He ran off with our savings.’

‘No! And … children?’ she asked, tentatively. ‘What happened to the—’

‘No children.’

‘Oh. Well. I guess that’s something.’

A silence fell.

‘Well!’ Inez filled it, bless her. ‘It looks like I won’t be troubled by any little rug rats of my own either. The rate I’m going. And it’s not like I’ve been starved of suitors. Believe me, Dora. Just about every halfway eligible gentleman in Colorado has thrown his hat in the ring.’

‘I’ll bet.’

‘Everyone in town knows I’m wealthy. Rather, they know my Uncle Richard is wealthy. And they know my aunt will be sure to make Uncle Richard make me wealthy too, the day I become a bride. It’s what Aunt Philippa goes around telling everyone.’

‘You probably have gentleman queuing round the block.’

‘Well – yes. That is, I did. I’ve lost count of the gentlemen I’ve refused. And it’s not that I’m fussy.’

‘Of course not!’

‘It’s just that the gentlemen in this town … I don’t like to be insulting. And I guess – well, maybe you see a different side of them.’

‘I guess I probably do.’

‘But they’re so darned dull with me! All they seem to talk about is business. Who made how many dollars buying this or that piece of real estate. And then they talk about hunting. Which is all very well, except I’m not interested. And then they talk about their automobiles. I spend half an hour with them and I’m already thinking to myself, well you’re such a dull fish – why, I’d far prefer to spend the rest of my life with my nose buried inside a novel than to have to spend another ten minutes listening to you.’

I laughed.

She looked at me curiously. ‘If it’s not too silly to ask,’ she said, ‘do they talk about their automobiles with you?’

Just then the door to the street burst open. Two men, brawny bodies buttoned tight under high woollen waistcoats, necks sweating in collar and tie, strode into the room with such purpose and energy that everyone in the saloon, half full by then, paused in their conversation to inspect them. The two men seemed oblivious to the attention, didn’t glance from left to right, but marched directly to the bar. They looked grim, of course. And on the shirtsleeve of the man closest, I could see a smear of blood. Lippiatt’s blood. I knew it was Lippiatt’s – rather, I suspected it, because I recognized the men as having accompanied Lippiatt on his visit to Plum Street all those weeks ago. We – that is, the three men, a couple of the girls and I – had shared a few drinks, whiled away an hour or so in the ballroom before dispersing to our separate bedrooms. I wondered if they would recognize me.

I hoped so. I hoped that they would spot me and come across. They were at the centre of it all this evening, and I was curious to know what had happened since we saw Lippiatt’s body being dragged away down the street.

‘Dora!’ Inez whispered so loudly, my name echoed off the wooden floors. ‘He has blood in his sleeve! Do you suppose—?’

‘Hush!’ I said.

But he had already turned. They both had. They looked us up and down. We made an incongruous pair. The man without blood on his sleeve looked at me more closely. He turned to the other, muttered something … Yes, the other one nodded. Yes, indeed. It was me. The hooker from Plum Street. Both men raised a hand.

‘What? Do they know you?’ asked Inez, aghast. ‘Those terrifying-looking gentlemen?’

I wasn’t sure how to answer. It happened I couldn’t remember either of their names. And, until they chose to acknowledge me, I was duty bound – honour bound – to deny it anyway.

‘Dora!’ shouted the dark one.

And so it was decided.

They picked up their glasses and crossed the room towards us. ‘A sight for sore eyes,’ he said. ‘May we join you? Are you working tonight?’ They glanced at Inez, uncertain where she quite fitted in.

‘Working?’ Inez cried out. ‘Does she look like she is working? She most certainly is not working. Thank you very much …’ She studied them more closely, through whiskey-glazed eyes, and seemed to like what she saw. ‘However,’ she added, looking pointedly at the blonder one, the man with the blood on his shirt, ‘whatever your names may be, if you would like to sit yourselves down here …’ She missed the seat, patted the air around it and then seemed to lose her nerve. She glanced at me.

If I had sent the men away, how different things would be today! I didn’t do that. The excitement on her face – and the blood on his sleeve, and heck, they were two attractive men, and we were unaccompanied and a little drunk. I nodded, inviting the two of them to join us.

As they pulled up their chairs, Inez muttered something soft and briefly sobering about, ‘Aunt Philippa being worried.’ I could have called a halt to it then, I suppose. Or she could. She could have said to the men – ‘I really ought to be going.’ I might have walked with her to her home, since by then she was already canned, and certainly not able to make the journey alone. But I was canned too. I was off duty. I was having a good time. I don’t believe the thought even crossed my mind. ‘You said yourself you wanted to meet some new men,’ I whispered, and winked at her.

She swayed with laughter. ‘Oh, you’re shocking!’ she said gleefully. ‘I am in too deep now, for sure!’

Lawrence O’Neill was the taller, blonder, handsomer of the two, and the one with blood on his sleeve. He was an Irishman from Missouri; an activist, employed by the UMWA (United Mine Workers of America) to do his worst in Trinidad. Back then, of course, before the Great War and the revolution in Russia, the battle between labour and capital was mustering strength and fury in every corner of the globe. It happened that, for the time being, the UMWA had designated Trinidad its American centre. It was here, among the mines of Colorado, that the Union was concentrating its funds, its fight – and all its best people. Lawrence O’Neill from Missouri was among them, he told us. And, yes, it was Captain Lippiatt’s blood on his sleeve.

We were all where we shouldn’t have been that night. I should have been working, of course. Inez should have been at home with her aunt, playing bezique. And, on the night their friend was murdered, you would have thought those two Union men had better things to do than while away the hours with a small-town librarian and a tired old girl like me.

‘Tell me, Inez Dubois,’ Lawrence O’Neill leaned his body in towards her, his expression teasing.

‘Tell you what, Lawrence O’Neill?’ she purred back at him … A little bit of confidence and polish – the thought flipped through my mind – and she might have made a fine hooker herself. ‘What shall I tell you, Lawrence O’Neill? I’ll tell you anything you want to hear.’

‘Inez, honey,’ I interrupted half-heartedly. ‘Don’t you think we ought to be heading home?’

‘What’s that, Auntie?’ she said.

It made me laugh. ‘Just take it easy, won’t you?’ I muttered. These men aren’t like the ones who talk to you about automobiles. That’s what I should have told her.The blood on their sleeves isn’t something they smeared on for after-dinner party games.

Lawrence wanted to talk about the company-owned mining camps, or ‘company towns’, as we sometimes called them. And they were towns, really: privately owned fiefdoms, fenced off from the rest of America. They had their own stores, doctors’ surgeries, chapels and schools; their own set of rules (no hookers, no liquor allowed); even their own currency: miners’ wages were paid partially in scrip, only valid in the company town’s overpriced stores. Lawrence asked her if she’d ever visited a company town herself.

Of course she’d never visited. For that matter, neither had I.

‘I never have,’ she said bluntly. ‘But my aunt goes out to the little schoolroom at Cokedale every Friday, to help them with religious instruction. Or she used to. Before it all became so troublesome out there.’

‘It’s going to get worse now,’ he said. ‘Lippiatt changes things. You watch. It’s going to turn, now.’ He said it with a grim sort of relish. His friend nodded sagely – and I remember I felt a grim sort of chill. He was right. You could smell it – the turning point. The cold-blooded murder of a Unionist, right there, on North Commercial Street. Lippiatt’s death would change everything.

But Inez didn’t seem to be listening. She prattled on without missing a beat. ‘Aunt Philippa says it was quite the nicest little school building she’s ever visited, and far nicer than St Teresa’s here in town, which by the way I attended … And she says the company provides the sweetest little homes for the workers that are as cosy as can be. And each little family has its own little yard. And plenty of people grow their own vegetables and keep chickens and I don’t know what else. And I know what you are going to say. You are going to say that it’s perfectly all right for Aunt Philippa, who arrives at Cokedale in her motorcar and leaves again in a motorcar and goes home to a lovely house with two great furnaces and servants and honeycake for breakfast and all that – Well, I’m not saying anything about that …’

He laughed – rather gently, I thought, all things considered.

‘Aunt Philippa says she simply doesn’t know what the workers are complaining of.’

‘Well,’ he said, ‘I’m going to drive you out there, Miss Inez. How about that? I’m going to drive you out there tomorrow and you can see for yourself … The numbers of men who roam about the place with half their limbs missing. Because of just how nice and cosy it is down there in those coalmines. And the women who have to beg and borrow just to feed their own children. You think the company cares for its people? They don’t give a damn for the people. They own the people. And, by the way – if they cared so much about their damn people, perhaps you can explain to me why they send their Baldwin-Felts thugs to murder them, in cold blood, right here on the sidewalk in front of everyone.’

‘You’re getting the wind behind you, Lawrence,’ I interrupted. ‘Watch out now, or you’ll blow us all the way home.’

‘And excuse me for saying,’ Inez said, taken aback by his vehemence but – to her credit – not silenced by it, ‘with respect and all: Captain Lippiatt wasn’t employed by the company. He wasn’t one of their people. That is … He was quite the opposite.’

‘He was for the miners,’ O’Neill replied.

‘Oh god,’ I sighed. ‘I think it’s time for my bed.’ I’d spent too many hours of my life, listening to men windbagging about the rights and the wrongs of organizing unions, and the rights and wrongs of company towns – and I was sick and tired of the whole subject. If you asked me – but nobody ever did. I wouldn’t have told them anyway. It was none of my business.

Inez didn’t share my feelings. That much was clear. She was leaning towards Lawrence, preparing to continue the argument, when an elderly gentleman in a worn wool suit approached the table.

‘Miss Inez?’ he said.

She looked up at him. Her face fell. ‘Oh no,’ she moaned. ‘Not now. Please, Mr Browning. Can’t you just pretend you didn’t see me?’ She belched. ‘I’m just about getting started.’

‘I’ve been looking for you here, there and everywhere,’ he said. ‘Your uncle’s waiting outside in the automobile. If you don’t come out directly, I dare say he’ll come in and haul you out by your ears.’ The old man glanced around the table: two Union men, one blood spattered – and one old hooker: drunk as lords, every one of us …’I think you had better come with me.’

With a great, childlike sigh, she set down her glass and stood up.

‘What?’ cried O’Neill. ‘You’re running off? Just as it was getting interesting?’

‘Well, you can see that I have to.’ They looked at each other, and I swear – whatever was going to happen between them was sealed, right there and then. ‘But it was fun, wasn’t it?’ she said. ‘Can we do it again?’

‘Come to the Union offices. You know where they are?’

‘Not exactly.’

‘Well – see if you can’t find out. Ask for me.’ He smiled at her, a liquor-leery smile, and I don’t believe he was thinking much about the iniquities of company towns just then. ‘I’ll be around the next few days, Miss Inez Dubois. Maybe we’ll motor out to the Forbes camp together …’

She was about to leave, but she turned back. ‘And I haven’t forgotten, Dora,’ she said, waggling a single, dainty finger. ‘I’ve not forgotten about the singing lessons, you know.’ For a second I couldn’t even think what she was talking about. ‘Thank you for a beautiful evening.’

‘I enjoyed it,’ I said.

‘It started badly though, didn’t it?’ she said vaguely. ‘Lawrence O’Neill, I am very sorry about your friend.’

‘Aye,’ he said solemnly. ‘Thank you.’

‘Well. I had better leave. Thank you all. Dora, thank you …’ She was swaying, possibly on the verge of tears again. The old man attempted to take her elbow, but she pulled it away. ‘It was the best night of my life.’

She weaved her way through the long bar, the old man protective and irritable beside her. She was a fish out of water. A fish that had swallowed far too much sauce … I see her now, reeling meekly beside the old man. There were snickers and catcalls from either side, and of course she must have heard them. She must have known what a figure she cut. And yet, there was something beyond pride, something grand and oblivious as she made her way through the room. She looked happy and alive – and carefree, and bold and young. And she reminded me of what it was like to be someone who still believed – oh, I don’t know – that life could ever be more than a thing to be gotten through.

Lawrence O’Neill, I think, watched her leave and was filled with a different sort of regret.

It was a private transaction between the two of us – strictly against Plum Street Parlour House rules. I went upstairs with him, to his rooms at the Toltec, and woke before dawn in a state of shock. I had slept with a client still beside me. I took the cash from his wallet, and left without saying goodbye.

5 (#uf0dd83b0-f101-590f-aa7e-a8a3236d793b)

I looked out for her, but I didn’t see Inez for some time after. I often wondered how her aunt had reacted when she’d rolled home that night, reeking of liquor, and I took great pleasure in trying to imagine the ride back from the Toltec, Inez and her Uncle Richard side by side, Inez belching away, jabbering about politics. That she didn’t appear at the Union offices (which fact I learned from Lawrence O’Neill when I met him on the street a week or so later) seemed to illustrate that our evening together was nothing more than an amusing deviation for her.

Inez had melted back into her parallel world of educational talks and pious ladies’ tea parties, and I pitied her for it. To my surprise, I also missed her. I considered seeking her out at the library, and once even made it as far as the library steps. But when I glimpsed her at the desk, sober and prim, gossiping with the doctor’s wife, I lost my nerve and turned back home again. I suspected that, were we to meet at the stocking counter of Jamieson’s Department Store one day (as well we might), she would not even acknowledge me.

Meanwhile, as O’Neill had predicted, Lippiatt’s murder was the talk of the town, and the talk of our visitors to Plum Street. Tempers on both sides of the argument were hot and high, and there was no meeting point between them. Only a few months earlier, up in Colorado Springs, so one of my clients informed me, Lippiatt had been found guilty of unspeakable violence against some poor young woman, and there had been moves to excommunicate him from the Union altogether. Now, of course, it was a different story. His death became a focal point. He had died a Union martyr. At the Union conference that weekend, Lawrence O’Neill and his pals wore black crepe bows on their shoulders in remembrance of his heroism. But they hadn’t watched him, as I had, returning to the fray with his handgun. They hadn’t heard the bloodlust in his shout as he waved his weapon at the two detectives … Any more than they had watched the two detectives, standing side by side over his dying body, and shooting him again – tearing a hole through his throat and then his chest.

But I had been living at Plum Street seven years by then, and I’d learned when to share my opinion and when to keep it to myself. So I kept my mouth shut. They were all fools to me.

The Plum Street Parlour House was situated in an imposing, four-storey red-brick house, which stood apart from the lesser buildings on either side of it. It was handsome: there were steps leading to the front door, and before it was a porch with ornate wrought-iron banisters. There was an electric light, set in a three-foot-high candle carved in stone by the side of the door and, on the door, a vast and shiny brass knocker. Everything about the place offered up the same message: the smell of perfume and burning opium that seemed to leak from the bricks, the shine and splendour of our brass knocker, those flamboyant railings, the rich red and gold drapes at the windows, the sparkling chandeliers within – not even a child could have been in any doubt as to the building’s function. There were other brothels, even on our street, and in handsome houses too. But ours stood out. It glowed with lubricious promise. We were the most exclusive whorehouse in town, and those of us who lived and worked in it took a certain amount of pride in the fact.

There were eight of us working girls living at Plum Street back then. In addition we had Simple Kitty greeting at the front of house, two more housemaids, two kitchen maids, a cook and a barman, a musical director, who played piano in the main parlour and organized musicians for the ballroom each night. There was also Carlos, the man-of-all-work. And overlooking us all with her beady eye and the tightest pocketbook in Colorado, there was Phoebe: once a working girl herself, now Madam to the most popular parlour house in Trinidad. Unlike me, she had learned early on how to keep hold of her money and get the hell out of the game.

Phoebe must have been among the wealthiest individuals in town, but there was never a time when she wasn’t on the lookout to be making more for herself. Any chance for another buck, Phoebe would be onto it. She’d developed a hundred sly ways to cheat the johns so that they wouldn’t feel it, or didn’t care. She used to cheat us girls too, charging interest on debts we’d run up here and there. In the early years, I hadn’t used to mind so much. I was grateful for such a comfortable place to live. But more recently my attitude had changed. After so many years on my back, splitting my earnings with Phoebe and having nothing whatsoever to show for them, I had been trying, at last, to get myself in hand. I had eased up on the laudanum. Eased up on the liquor too. And I was beginning to keep some of my money back.

One of the girls must have told Phoebe I was trying to get myself together, and she didn’t like it one bit. At thirty-seven years old, I wasn’t the youngest girl in the house, and maybe I wasn’t the prettiest either, but I knew what I was doing. I pulled in more than my fair share of business and Phoebe wasn’t ready to lose me.

The morning they shot Lippiatt she had presented me with an unpaid receipt from a dressmaker who’d been dead for two years. Maybe it was genuine – I had been drinking a lot two years before then, and the laudanum would have been playing its part. In any case, I had no way to check up on it. Even if I had, there wasn’t much I could have done about it. Phoebe held the town in her pocket. If she decided I owed her – well then, I owed her. For all its comforts and luxuries, Plum Street was a jail of sorts. Leaving it was never going to be a simple business …

As I sit here twenty years on, at my little desk overlooking the warm Pacific Ocean, it seems the greatest of miracles to me that I ever did.

But life at Plum Street had its compensations. For a few years I used to think that William Paxton was one of them. He owned a gun store in town, and a few others upstate, and from the frequency of his visits to see me, I assumed they made him a good living. He’d been my regular client since his wife was sick and dying, and he was a decent man: quiet, gentle and generous.

He used to talk to me about his wife when she was dying and, after that, when his grief had eased, about all sorts of things. Sex and music and … well, sex and music, mostly, which were our interests in common. Maybe a little bit about real estate and automobiles, too. In any case, we became friends. I told him something about my life before I came to Trinidad – not all of it true, of course. But I told him how I came from England, the child of two Christian missionaries, one long dead, the other long since returned to England – which was true. And I told him how, before circumstances changed, I used to travel the Western circuit with a group of popular musicians and stand before a full hall and sing and dance, and that once, long ago, I was quite a music hall sensation. Which was also true, so far as I recall.

He bought me a little, old-fashioned harpsichord – heaven knows how he found it – which I kept in my rooms (Phoebe said a piano would have made too much noise), and we used to sing together; or, more often, I would sing for him. I told him, as I told Inez, about how one fine day, when I was too old for this game, I wanted to open a little singing school, perhaps in Denver. He pinched me and laughed.

‘Don’t be absurd, Dora,’ he said, and I know he meant it kindly. ‘You’ll never be too old for this game. You’ll be adorable until the day you die.’

He used to tell me how much he cared for me. And I believe he did. Occasionally, when we were alone together, he used to mutter tender things; and I am convinced that in the last few weeks and months, before Lippiatt’s death seemed to change everything in our little town, his feelings for me were stronger than ever. He said to me, a month or so before Lippiatt died, that he was ‘missing the comfort of a wife’, and on another occasion, around the same time, I remember he said: ‘I want to behave to you as a gentleman should.’

Inevitably, perhaps, I played the words over until they meant what I wanted them to mean: something vast and precious. And I began to believe that he loved me and that I loved him.

Well, he came to see me in the week after Lippiatt’s death. The streets were still cluttered with angry delegates, and the sheriff’s men roamed among them, waving their guns. William sought me out at Plum Street in the midst of it, earlier in the day than was usual. If he had been anyone else, I might have kept him waiting. But William was different, and when I came down to the ballroom I greeted him warmly – too warmly. Beady Phoebe swept across the room and shot me a warning look. It was against house rules to form strong attachments. ‘For your own protection,’ she used to tell us. ‘I don’t want my girls getting their hearts all smashed up. Bad for business.’

‘No heart left to smash,’ I used to say.

But afterwards, I knew I should have listened. Our heads were side by side on the pillow … and I wince to remember the affection I felt as I looked across at him. He glanced at me, sheepish as hell, gave a tug on his moustache, which he never did before and, for the maddest moment, because he looked so terribly ill at ease, I was certain he would speak the words. He said:

‘Dora, I’ve been meaning to mention …’

‘Mention what, William?’

‘Only the fact is …’

‘Yes, William?’

‘Because I want to do right by you, Dora. Never doubt it.’

‘I never would doubt it, William.’

‘I probably would have been sunk without you, after Matty died.’ He laughed. ‘I tell myself you kept me sane. I believe you did.’

‘Nonsense. You kept yourself sane. I just …’ I couldn’t think how to finish the sentence, so I left it there.

‘Fact is, Dora …’

I stroked his face and kissed his shoulder. His shyness melted my heart! ‘The fact is, what,darling man?’ I said.

‘Fact is, I’ve met a girl in Denver.’

My heart gave a double beat of misery.

‘She’s the sweetest girl.’

‘A sweet girl?’ I repeated. ‘You have met a sweet girl in Denver?’

‘I’m sure you’d take to her.’

‘Oh. I am sure …’

‘I mean to say, if you ever met her.’ Idly, awkwardly, he stretched an arm across the bed to caress me. ‘She is the most lovely girl I ever met,’ he said, and as he spoke he continued to tweak and squeeze and massage. ‘And the beauty of it is, she’s young enough for a whole brood of children!’ He laughed. ‘Unlike you, Dora! You and I are as old as the hills.’

I smiled. And smiled again. I wasn’t so damn old.

‘And the point of it is, Dora. Well, she has very kindly – crazily – but yes, Dora. She has agreed to be my wife.’

‘Oh!’

‘Yes. I’m kind of reeling from it myself, truth be told.’

‘It’s wonderful news.’

‘Yes. Yes indeed it is. Only the reason I mention it,’ he said.

‘The reason you mention it …’ I kept smiling, but my hand brushed his away. And I can picture his face now: an expression of slight hurt, mild surprise. He rested his arm by his side. ‘Since this nonsense with Lippiatt …’ he continued. ‘Well, it was the last straw. And I want you to believe, Dora, that my only regret in all of it will be leaving you. But I have decided to settle in Denver. It’s a better city. Don’t you think?’

He seemed to expect a reply. ‘I hardly know,’ I said.

‘There is so much vice here in Trinidad,’ he said, without a trace of irony. ‘I don’t want my wife and children living in such a place. Trinidad’s not the place it used to be.’

‘But I’m sure it won’t always be like this,’ I said, as if anything I said might have altered anything. ‘It’s only these past few weeks that things have gotten so bad. I’m sure as soon as the two sides can find agreement …’

He shook his head. ‘They found a company man on the rail tracks outside Forbes camp last night. Shot dead.’ Somehow his hand had worked its way back to my breast. ‘Retaliation killing,’ he muttered. ‘It won’t be the last, either.’

‘Well, but—’

‘But … but – nothing,’ he said. ‘I just want you to be happy for me. Can you manage that? Please?’