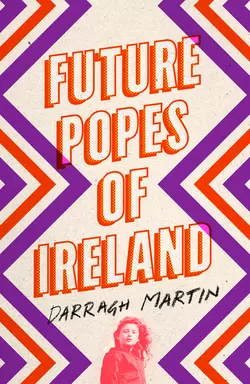

Future Popes of Ireland

Darragh Martin

A big-hearted, funny and sad novel about the messiness of love, family and belief‘Hilarious and timely, a dazzling debut’ John Boyne‘Bustling, bubbly, bittersweet fun’Daily Mail‘Bulging, big-hearted, a pleasure to read’Irish Times‘Think Zadie Smith. But much funnier’Sunday Independent‘Very moving, highly entertaining, clever and funny’Sunday Times (Ireland)‘Funny, warm and full of heart’ Image MagazineIn 1979 Bridget Doyle has one goal left in life: for her family to produce the very first Irish pope. Fired up by John Paul II’s appearance in Phoenix Park, she sprinkles Papal-blessed holy water on the marital bed of her son and daughter-in-law, and leaves them to get on with things. But nine months later her daughter-in-law dies in childbirth and Granny Doyle is left bringing up four grandchildren: five-year-old Peg, and baby triplets Damien, Rosie and John Paul.Thirty years later, it seems unlikely any of Granny Doyle’s grandchildren are going to fulfil her hopes. Damien is trying to work up the courage to tell her that he’s gay. Rosie is a dreamy blue-haired rebel who wants to save the planet and has little time for popes. And irrepressible John Paul is a chancer and a charmer and the undisputed apple of his Granny’s eye – but he’s not exactly what you’d call Pontiff material.None of the triplets have much contact with their big sister Peg, who lives over 3,000 miles away in New York City, and has been a forbidden topic of conversation ever since she ran away from home as a teenager. But that’s about to change.

(#ua7f65e4a-e754-5b6c-abf8-3078013cdb95)

Copyright (#ua7f65e4a-e754-5b6c-abf8-3078013cdb95)

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk (http://www.4thEstate.co.uk)

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2018

Copyright © Darragh Martin 2018

Photograph of girl on cover © Plainpicture

Cover design by Jack Smyth

Darragh Martin asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008295394

Ebook Edition © August 2018 ISBN: 9780008295417

Version: 2018-08-31

Dedication (#ua7f65e4a-e754-5b6c-abf8-3078013cdb95)

For Aoife, Gillian, Caroline and Brendan

Contents

Cover (#u88cc9087-1993-5fc2-98f7-e43259ea4e71)

Title Page (#u38d6070d-9fd4-5691-a472-b9a1bac532fc)

Copyright (#u87c2f27f-881c-5a23-9c5c-e0aba0f5cc12)

Dedication (#u284fb3dc-bf75-55fb-b06e-ee89c5a7130a)

I. Baptism (#u8c34fb33-f60a-59f9-854e-127deedf1a9c)

II. Beatification (#u3c261a57-dcca-5e31-95e8-a3bc4c3670aa)

III. Communion (#uf322e6d1-470e-58c7-8d3a-c75fb88ab6e4)

IV. Confirmation (#litres_trial_promo)

V. The Revolutions of Rosie Doyle (#litres_trial_promo)

VI. The Pride of Damien Doyle (#litres_trial_promo)

VII. The Tricks of John Paul Doyle (#litres_trial_promo)

VIII. Boom (#litres_trial_promo)

IX. Bust (#litres_trial_promo)

X. Last Rites (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Series I:

Baptism (#ua7f65e4a-e754-5b6c-abf8-3078013cdb95)

(1979–1980)

1

Holy Water Bottle (1979)

It was September 1979 when Pope John Paul II brought sex to Ireland. Granny Doyle understood his secret message immediately. An unholy trinity of evils knocked on Ireland’s door (divorce! abortion! contraception!) so an army of bright-eyed young things with Miraculous Medals was required. Phoenix Park was already crammed with kids listening to the Pope’s speech – chubby legs dangling around the necks of daddys; tired heads drooping against mammys – but Granny Doyle knew that none of these sticky-handed Séans or yawning Eamons would be up for the task. No, the lad who would rise from the ranks of priests and bishops to assume the ultimate position in the Vatican would have to come from a new generation; the Popemobile had scarcely shut its doors before the race was on to conceive the first Irish Pope.

First in line was Granny Doyle, armed with a tiny bottle of papal-blessed holy water. The distance between Granny Doyle’s upheld bottle and the drops flying from the Pope’s aspergillum was no obstacle; this was not a day for doubt. Helicopters whirred above. The Popemobile cruised through the streets. A new papal cross stretched towards the sky, confident as any skyscraper, brilliantly white in the sun’s surprise rays. All of Dublin packed into Phoenix Park in the early hours, equipped with folding chairs and flasks of tea. Joy fizzed through the air before the Pope even spoke. When he did, it was a wonder half a million people didn’t levitate immediately from the pride. The Pope loved Ireland, the Pope loved the Irish, the Irish loved the Pope; this was a day when a drop of precious holy water could catapult across a million unworthy heads and plop into its destined receptacle.

Granny Doyle replaced the pale blue lid on the bottle and turned to her daughter-in-law.

‘Sprinkle a bit of this on the bed tonight, there’s a good girl.’

A version of this sentence had been delivered to Granny Doyle on her wedding night, by some fool of a priest who was walking proof of why Ireland had yet to produce a pope. Father Whatever had given her defective goods, clearly, for no miracle emerged from the tangled sheets of 7 Dunluce Crescent that night or for a good year after, despite all the staying still and praying she did on that mattress. Then, all she had for her troubles was Danny Doyle, an insult of an only child, when all the other houses on Dunluce Crescent bulged with buggies. Ah, but she loved him. Even if he wasn’t the type of son destined for greatness, the reserves of Shamrock Rovers as far as his ambitions roamed, he was good to her, especially since his father had passed. Nor was he the curious sort, so much the better for papal propagation; he didn’t bat an eyelid as Granny Doyle transferred the bottle of water to her daughter-in-law’s handbag. His wife was equally placid, offering Granny Doyle a benign smile, any questions about logistical challenges or theological precedent suppressed. Only Peg seemed to recognize the importance of the moment, that divil of a four-year-old with alert eyes that took in everything: Peg Doyle would need glasses soon, for all the staring she did, and Granny Doyle could summon few greater disappointments than a bespectacled grandchild.

In truth, it was her mother’s handbag that had Peg’s attention, not the bottle of holy water. After a long day of disappointment, when it became clearer that the Pope would not be throwing out free Lucky Dips into the crowd, Catherine Doyle’s handbag was Peg’s only hope. It might have a Curly Wurly hidden in its folds. Or Lego. Perhaps, if Peg was lucky, there might be a book with bright pictures, which her mother would read to her, squatted down on the grass while meaner mammys kept their kids focused on the tiny man on the tiny stage. Peg knew it definitely wouldn’t contain her copybook, which was the one treasure she really desired. Since she’d started school a few weeks ago, Peg had come to love her slim copybook, with its blank pages waiting for Peg’s precise illustrations to match her teacher’s instructions. My Home and My Mother and the gold star worthy My Street were lovingly rendered in crayon, letters carefully transcribed from the blackboard – Very Good, according to Peg’s teacher. It would be weird to take homework on a day out, Peg’s mother said, as if squishing into a field to squint at a man with a strange hat wasn’t weird at all.

Peg sighed: the holy water bottle disappeared into the handbag, one quick zip cruelly thwarting Peg’s happiness. Her mother didn’t notice her gaze, looking instead in the direction of the stage, like all the other grown-ups. That was the way of Peg’s parents: they looked where they were supposed to, straight ahead, at the green man, at the telly. Granny Doyle had different kinds of eyes, ones that explored all the angles of a room, eyes that glinted at her now. Peg avoided that gaze and focused on her new leather shoes, both consolation and source of deeper disappointment. On the one hand, the bright black school shoes were the nicest Peg had ever owned. She had endured multiple fittings in Clarks before they found a pair that were shiny enough to impress a pope and sensible enough not to suggest a toddler Jezebel. They were perfect. Except they would be better in the box. They looked so pretty there, Peg thought mournfully, remembering how nicely the tissue paper filled them, how brightly the shoes had shone, before the trek across tarmac and the muck of Phoenix Park had got to them. The morning had contained more walking than Peg could remember and not a bit of it had been pleasant: a blur of torsos that Peg was dragged through, the grass an obstacle course of dew and dirt. Only the thought of the shoebox – the smell of newness still clinging to the tissue, waiting for Peg’s nose once she ever got home – kept Peg’s spirits up; soon, she would be back in 4 Baldoyle Grove, in her room with its doll’s house and shoebox and soft carpet.

‘Come on, you come with me. We’ve a long drive ahead of us.’

The shoebox would have to wait; Granny Doyle had other plans for Peg. The grown-ups had been negotiating while Peg had been daydreaming and it suddenly became clear that Peg’s feet would not be taking her back to 4 Baldoyle Grove that night. Peg looked forlornly up at Granny Doyle’s handbag. She knew exactly what it contained: wooden rosary beads and bus timetables and certainly not a Curly Wurly; some musty old Macaroon bar, perhaps, which Peg would have to eat to prove she wasn’t a brat or some divil sent to break Granny Doyle’s heart, an organ that Peg had difficulty imagining. It’ll be a great adventure, Peg heard Granny Doyle say, the slightest touch of honey in her voice before briskness took over with Come on, now and Ah, don’t be acting strange. Acting strange was a popular pastime of Peg’s, never mind that most of the grown-ups paraded in front of her deserved such treatment. Peg looked up at her parents. They were useless, of course; they couldn’t refuse Granny Doyle anything.

‘Come on, now,’ Granny Doyle said, in a softer voice, feeling a stab of affection for her odd little grandchild. A calculating creature with far more brains than were good for her, perhaps, but Peg could be shaped into some Jane the Baptist for a future Pope. There was no doubt that such a child was coming – 29 September 1979 was not a day for doubt! – and Granny Doyle felt a similarly surprising wave of love for the crowds that only a few hours ago had been intolerable. Euphoria trailed in the air and Granny Doyle clung on, sure that this was the date when all the petty slights of her life could be shirked off, the superiority of Mrs Donnelly’s rockery nothing to the woman who would grandmother Ireland’s first Pope. Even the plod of the brainless crowd could be handled with tremendous patience, especially when she had her elbows at the ready.

‘We’re going to have a great weekend,’ Granny Doyle said, cheeks flushed.

Peg had no choice but to follow, a long line of grown-ups to be pulled through as her shoes sighed at the injustices of outside.

Later, when Peg scoured photos of the Pope’s visit to Phoenix Park, she found it difficult to remember the crowds or the stage or even the man. She had a nagging uncertainty about whether she could remember this moment at all; perhaps she had come to realize the significance of the event for her life and had furnished a memory shaped from fancy and photographs. Later, there would be the jolt that here was perhaps her first mistake; in her darker moments, Peg Doyle would wonder if everything might have uncoiled differently had she never taken her grandmother’s hand.

But Granny Doyle’s grip was not one to be resisted and Peg found herself pulled into the crowds before she could wish her parents goodbye. Something else that Peg would always wonder about: did she remember her parents extending their arms at the same time before she was whisked off? A gesture hard to read, halfway between a wave and an attempted grab, nothing that was strong enough to counteract the pull of Granny Doyle or the tug of the future.

2

Handbag (1979)

There is no record of what happened to the contents of the holy water bottle. As with many of the items in this history – the Blessed Shells of Erris; the Miraculous Condom; the Scarlet Communion Dress – no material evidence has remained.

Given the personalities involved, it seems likely that Catherine Doyle sprinkled the holy water on the bed-sheets as instructed. Both the angle of the holy water as it fell from the bottle and the arc of Catherine Doyle’s eyebrows as she poured it have been lost to history. Did she do it with great ceremony, like a woman from the Bible pouring water from a jar? Was there instead a rueful roll of the eyes, an ironic dance routine? Can a more erotic encounter be discounted? Elbows propped on strong shoulders, legs curved around a supple frame, a conspiratorial glance between the two. Fingers dipped into a bottle, tracing the contours of a body, travelling across thighs, honing in on the source, the pump of future Popes …

This history refrains from comment. It is enough to report that when Granny Doyle emptied her daughter-in-law’s handbag nine months later and donated all of Catherine Doyle’s things to the St Vincent de Paul, no bottle of holy water was found inside, empty or otherwise.

3

Folding Chairs (1979)

She could almost walk to Galway, Granny Doyle felt, still buzzing from seeing the Pope that morning. Even Dunluce Crescent felt fresh as she turned the corner, as if the glow from Phoenix Park was contagious, no part of Dublin untouched. The quiet cul-de-sac tingled with life, its unassuming brick houses suddenly resplendent in this papal-endorsed sunlight. Her house was the finest, Granny Doyle knew that: 7 Dunluce Crescent had a grand garden and a large porch extension that gleamed in the sharp sun. Granny Doyle felt a surge of pride for her son, for this was Danny’s greatest achievement. He could build things, had built the finest porch in Killester; who cared if that upstart Mrs Donnelly had added a water feature to her rockery?

The only emotion Peg felt at seeing Dunluce Crescent was relief – which was misplaced, as her little legs had barely flopped onto one of the porch’s folding chairs before Granny Doyle was making grand plans to leave again. ‘We’ll have to beat the traffic,’ she called out from the kitchen, as if any other Dubliners would be mad enough to chase the Pope around the country. ‘He’ll be well on his way,’ Granny Doyle added, keen to share her radio updates with her friends gathered in the porch. Glass was the great friend of gossip and the porch served as the de facto community centre for the other old biddies on the street. They had all moved into the crescent within a few years of each other in the late Fifties and here they were, families raised and husbands buried, their lives moving in synch, morning Masses in Killester Church and the excitement of Saturday’s Late Late Show and Sunday roasts shared with disappointing children and glowing grandchildren and every event unpicked in Granny Doyle’s porch, which contained a folding chair for each of the auld ones on Dublin’s own Widows’ Way.

Peg imagined Granny Doyle’s neighbours as the fairies from Sleeping Beauty. Mrs McGinty was the tall, stern one and she mostly ignored Peg, which was far from the worst thing an adult could do. The McGintys had never had children and with her husband long gone, Mrs McGinty’s life revolved around the Legion of Mary, the youth branch of which she chaired with zeal. Mrs McGinty stood poker-still in the porch, eager to get going, the boot of her car packed the night before.

Mrs Nugent was her opposite in almost every way. A tiny woman, full to the brim with mischief and gossip, Mrs Nugent had enough energy to power the road through a blackout. Hearing that Peg was joining them, Mrs Nugent unleashed a stream of chat – isn’t that brilliant, pet? and won’t we have a great adventure, love? – gabbling onwards as if she’d never met a silence she couldn’t fill. Worse, she’d decided to bring one of her many grandchildren along for the trip, some ball of fury and flying limbs whose name Peg declined to remember, but who might as well have been called Stop That! for the number of times Mrs Nugent directed the sentence towards her.

Mrs Fay was the only one of Granny Doyle’s neighbours who had the temperament of a Disney fairy. A large woman with a kind face and impeccably coiffed white hair, Mrs Fay’s shoulders could easily have accommodated wings. Mrs Fay kept a basket of proper chocolate bars by her door for Halloween, not cheap penny sweets like Mrs Nugent or hard nuts and apples like Mrs McGinty. All sorts of other delights awaited beyond the threshold of 1 Dunluce Crescent, Peg imagined: freshly baked biscuits, shelves filled with books, curtains with tassels she could spend an afternoon admiring. Mrs Fay still had a Mr around, so she wouldn’t be joining them – a shame, because Mrs Fay was the only one of them who had noticed her new shoes and Peg was sure she’d stash decent treats in her handbag.

‘He’s left Drogheda,’ Granny Doyle shouted from the kitchen, information that seemed to add urgency to her clattering, even though the Youth Mass they were planning to catch in Galway wasn’t until the next morning.

‘He’ll be lunching with the priests in Clonmacnoise next,’ Mrs McGinty said.

‘Isn’t it a crying shame that Father Shaughnessy gets to meet him,’ Mrs Nugent fumed. ‘And him a slave to the drink.’

Mrs McGinty tutted, a sophisticated sound that conveyed both that she would never criticize the clergy so openly and that Father Shaughnessy was not the sort who should be lunching with the Pope.

‘Oh dear!’ Mrs Fay said.

Long ago, Mrs Fay had decided that most events could be met with an oh dear! or a lovely! and thus she was always ready to temper the world’s delights or iniquities.

Meanwhile, Mrs Nugent had found a new topic to animate her.

‘Did I tell you that Anita’s Darren is going to be one of the altar boys at the Mass tomorrow?’

‘So you said,’ Mrs McGinty said in a thin tone.

‘Lovely!’ Mrs Fay offered.

Darren Nugent’s proximity to a pope was enough to summon Granny Doyle from the kitchen. Before her brilliant holy water idea, she’d been tired of Dunluce Crescent’s many connections to the Pope. Mrs McGinty had a fourth cousin who was concelebrating the Mass in Knock. Not only was Mrs Brennan’s brother-in-law due to sing at the choir in Galway, but didn’t he get his big break at her Fiona’s christening, so she was basically responsible for his career. Even pagan Mrs O’Shea who could only be glimpsed at the church at Christmas, Easter at a pinch, had a shafter of a son who had helped clean the Popemobile. Now Granny Doyle could bear it all with fortitude, convinced that no Darren would ever develop a posterior suitable for a papal chair.

‘I can get you all Darren’s autograph tomorrow if you want,’ Mrs Nugent offered.

‘He’ll have to learn how to write first,’ Mrs McGinty tutted.

Granny Doyle was more magnanimous.

‘That would be an honour,’ she said, locking the inside door and scooping Peg up off her chair. ‘And you’ll have to get me yours as well: didn’t you say that the Pope winked at you?’

This was a well-placed grenade, Mrs McGinty’s fury at the blasphemy involved in a winking Pope strong enough to get them all out of the porch before it shattered. ‘He did, looked at me right in the eye and winked,’ Mrs Nugent insisted, chortling all the way down the footpath, displeasure the lubricant that kept them all together because Mrs McGinty lived to judge and Mrs Nugent lived to incite judgement. Granny Doyle beamed, loving the chat and her neighbours and her street and her granddaughter and even Stop That!, who at least had the wisdom to raid Mrs Donnelly’s rockery when she was after missiles to launch at passing traffic.

Peg clambered into the back of Mrs McGinty’s battered Fiat, beside Stop That!, who had abandoned her rocks to investigate the weaponry potential of seat belts. Mrs Nugent shuffled in beside them, stop that! and are you all right, pet? and it was not a bit of dirt in his eye! launched between the last few precious puffs of a cigarette. Peg wriggled away from Stop That’s seat-belt attack to look out the back window. Mr Fay had joined his wife on the side of the road, the better to properly see off their car. Both Fays thought that attending the Pope’s Youth Mass would be lovely, so there was slim chance they’d rush forward to rescue Peg. They stood there, smiling and waving, on the side of the quiet street in the afternoon sun. Peg gazed at the porch behind them, enticingly empty, the perfect place to spend the day, if Mrs McGinty hadn’t pressed her shoe against the accelerator.

Dunluce Crescent was only a scrap of a street, so by the time Peg’s head bobbed up again, they had already turned the corner and the kind smiles and waves of the Fays had disappeared from view, replaced with rows of other red-brick houses, indifferent to the motion of their car, waiting instead for fresh coats of paint and attic conversions and tarmac paving over gardens, the fortunes of the Doyles nothing to them.

4

Roll of Film (1979)

The next morning, something of a holiday spirit remained. They slept in, skipped the Sunday Mass, left the sheets in a tangle around their limbs. Danny Doyle still had some film left in the camera from the day before, so of course he clicked.

‘You dirty pervert,’ she called.

He smiled and wound the film again.

‘You’ll never be able to develop this.’

She fixed her hair, posing now, legs twined around each other in the air, no hand outstretched. Lying naked on their bed. Something between a smile and a smirk. It was the last shot. The film started to rewind as he pressed down, making him worry that it might not come out.

5

Plastic Spade (1979)

Peg woke up to the Pope’s nose brushing her forehead.

‘Isn’t this brilliant? They were selling them two for a pound at Guineys.’

Mrs Nugent continued to wave the commemorative tea towel in her face while Mrs McGinty’s expression conveyed the blasphemy involved in drying dishes with the Pope’s face.

‘You’re not going to use that, are you?’

‘Of course not,’ Mrs Nugent said.

Granny Doyle snorted to show her displeasure with the ornamental display of a potentially useful object. Mrs Nugent ignored the pair of them.

‘I’m going to get it autographed!’

‘By your Darren?’ Mrs McGinty asked slyly.

‘By her winking boyfriend,’ Granny Doyle said.

The titters that followed were too much for Mrs McGinty, who rounded on the slumbering Peg and Stop That!

‘We’ll never get anywhere if this lot don’t get a move on,’ she said.

Peg groaned. She’d hardly had a wink of sleep in the small folding bed she’d shared with Stop That!, who spent her dreams battling supernatural foes, limbs jagging towards Peg as she vanquished monsters. They’d arrived in Mayo late last night, the lot of them bundling into Granny Doyle’s childhood home in Clougheally, at the edge of the Atlantic. It wasn’t at all on the way to the Pope’s Mass in Galway but it was a place to rest their heads and a chance to pick up further flock for their mad pilgrimage. A clatter of second cousins were coming with them, as well as Nanny Nelligan, Granny Doyle’s mother. Peg couldn’t help staring at her great-grandmother, whose many wrinkles announced that she’d been born in the nineteenth century and whose constant sour expression suggested that she might have been happier staying there. It was a shock to Peg that anybody could be older than Granny Doyle, yet here was this ancient creature, clad in dark shawls and muttering in Irish, roaming around her creaky house at the edge of the sea.

The house was haunted, Peg was sure of it, another reason she had hardly slept. They could definitely hear ghosts, Stop That! had agreed, in a rare moment of interest in something Peg said. ‘That’s just the wind,’ Granny Doyle scolded, but Peg was sure she was lying; Peg caught the fear in Granny Doyle’s eyes too. Even if it was the wind, it wasn’t an earthly gust; Peg’s window at home never rattled like this. It was the house, with its black-and-white photographs of people who had died, and its doors, which creaked with the ache of being opened, and its air, thick with secrets and sadness. Besides, Clougheally would be glad of the ghost, there wasn’t much to the village otherwise: a few other houses, with scraps of farm; one newsagent’s; two pubs.

‘Will we have a quick trip to the strand before we head off?’

Aunty Mary, at least, knew that the only sensible thing to do in that house was to escape. Aunty Mary was Granny Doyle’s younger sister, though Peg called her Aunty, because she seemed to belong to a different generation to the hair-curling ladies of Dunluce Crescent. Aunty Mary kept her hair grey and styled into a severe bob. The trousers she wore matched the seen-it-all stride of her legs and say-what-you-like set of her chin. Peg was sure that the students in the Galway secondary school where she taught were terrified of Mary Nelligan. Not Peg, though: Peg never saw a trace of this Scary Mary. Aunty Mary was the one to show Peg the spider plant where scraps from Nanny Nelligan’s bone soup could be hidden, sure that thing’ll be glad of them, or the rock on the strand where notes could be left for fairies, we’ll see what they say, never a trace of harshness about her voice when she spoke to Peg.

Granny Doyle had gone off to get Nanny Nelligan ready for the day, so Aunty Mary seized her advantage.

‘It’d be a crime not to say hello to the sun on a day like this.’

She had Peg and Stop That! dressed and marching down the path to the beach before Mrs McGinty could object; Aunty Mary had a way of getting what she wanted.

Seeing the dawn on Clougheally strand was something that everybody should want, Peg was sure of it. The Atlantic rushed towards them, bringing the news from New York, went the saying – not that anybody in Clougheally paid any mind to the sea’s gossip, enough goings-on in Mayo to be busy with. Peg stared at the horizon, amazed at the sight of sky and sea for ever. A cluster of small fishing boats braved Broadhaven Bay and some bird swooped this way and that but otherwise the place was tremendously empty, a delight after all the bustle of Phoenix Park. Peg could easily imagine the Children of Lir soaring through a similar sky and settling on Clougheally’s boulder, its claim to fame and name: Cloch na n-ealaí, the Stone of the Swans (an English error, Aunty Mary tutted, for carraig would have been the appropriate word for a boulder, though Peg liked the smallness of stone, as if the place was sized for her).

Peg made Aunty Mary tell her the story of the Children of Lir every time they visited. King Lir had four children, Fionnuala and her three brothers, who were as good as could be. Too good for their wicked stepmother, in fact: she had them turned into swans and sentenced the poor creatures to nine hundred years of exile around the loneliest places of Ireland. They cried and suffered and huddled in each other’s wings but after nine hundred years they turned into wrinkly grown-ups, met Saint Patrick, and got baptized before they died. Clougheally appeared in the part with the suffering: three hundred of the Children of Lir’s years of exile were spent in Erris, the borough in County Mayo where Clougheally was located. Local legend had it that they huddled together on a special stone and looked out at the Atlantic. It still stood there, so the story went, the Stone of the Swans, a boulder on the other edge of the beach, treacherously perched on a mound of rocks: a scary place to spend centuries.

‘Stop that!’

Stop That! had a different interest in the Children of Lir’s boulder: it was the most dangerous item to climb on the beach, so she made a beeline towards it.

‘Would you not play a nice game or something?’ Mrs Nugent huffed, her feet finally on the beach.

Stop That!’s idea of a game was scouring the sand for the ideal missile to fling at whatever poor bird was flapping its wings in the distance. Peg left her to it, guarding the treasures on her own corner of the beach. Aunty Mary had given her a plastic spade and the beach was hers to explore. There were all sorts of brilliant things to find: pennies that might come from different countries and brightly coloured pieces of glass and so many shells that Peg could have spent the day cataloguing them. Peg didn’t rush, supremely content sifting sand from shells, arranging her little collection in order of size. She’d pick the prettiest to bring back to her windowsill in Dublin and she might even draw one in her copybook. Aunty Mary stood to the side, helping Peg spot a gem occasionally, mostly just watching her, quietly. Even Mrs Nugent kept her chat inside, enjoying her morning cigarette and cup of tea on the empty beach, that spectacular stretch of sand, where the flap of wings from across the bay could be heard on the right day. Organizing her collection of shells on the sand in the morning sun, Peg felt a surge of happiness.

But there was Granny Doyle, a cloud across the sky.

‘What are the lot of ye doing? Mammy’s waiting in the car and we’d want to get going if we’re to miss the crowds.’

Aunty Mary braced herself and shot Peg a such are the trials of life glance.

Mrs Nugent stubbed out her cigarette on one of Peg’s shells and turned towards her granddaughter.

‘For the love of God, stop that, would you: you have your dress wet through! We had better get going: I’d say the Pope is only dying to get my autograph!’

6

Toast Rack (1979)

Catherine was the one to venture downstairs, eventually. She’d have to check the clock and phone Peg and deal with the day, though not yet. First, breakfast. She smiled as she caught a glimpse of her body in the kitchen window. Her bare toes drummed against the lino as she eyed the steel toast rack suspiciously; she wished the toast would pop faster, afraid the spell would break if she stayed away too long.

They’d eat the toast in bed, she decided, not waiting until it cooled to butter it.

7

Vatican Flag (1979)

Even the rain couldn’t break the buzz in the air. Granny Doyle didn’t even bother with her brolly. Nobody in Galway racecourse would have their spirits broken by a bit of drizzle. Pope John Paul II wasn’t going to be dampened. If anything, he had more energy, as if Ireland had recharged him, not a problem for him to burst into song upon request. The crowd started it, tens of thousands of voices roaring out the song that had become his anthem.

He’s got the whole world in his hands,

He’s got the whole wide world in his hands.

Granny Doyle looked around the crowd and beamed. Galway racecourse was a sea of Vatican yellow flags, like an All Ireland where everybody was on the same team. Everybody was singing along: Mrs Nugent waving her tea towel and belting out the tune; Mrs McGinty thrilling in her best Church Lady voice designed to test stained glass; her mother bobbing her beshawled head in time with the beat; the Clougheally crowd of second cousins joining in, joyfully out of key.

The Pope stayed on the stage after the Mass, joy widening his face. When he spoke it was with the heart-heave of a teenage Romeo, a fallible and unscripted pronouncement, one all the more charming for it: ‘Young People of Ireland: I Love You.’

The crowd erupted into a cheer that travelled like a Mexican wave.

Mrs Nugent chuckled.

‘Didn’t I tell you he’s always talking to me?’

Even Mrs McGinty managed a laugh at this; it was impossible to frown. If she’d had a bottle large enough, Granny Doyle would have captured the happiness in the field and been a rich woman for years.

‘Quick now, we’ll take a photograph.’

Granny Doyle passed the camera to Mrs Nugent, scooped up Peg and marched over to her mother. Aunty Mary was left to the side; no harm, she’d only spoil it.

‘Big smile for the camera, like a good girl,’ Granny Doyle said to Peg.

Mrs Nugent fumbled for the button.

‘All right now, one … two … three … cheese and onion!’

The photograph was a remarkable coup, heralding never-again-seen skills from Mrs Nugent. Peg, Granny Doyle, and Nanny Nelligan squinted at the camera in the foreground, Pope John Paul II was flanked by Bishop Casey and Father Cleary in the background, heroes all three. A special effect of the morning sun gave the appearance of halos, the smiles of all three women stretching to meet the light.

Months later, Peg clutched the photograph, thrilled at a memento she was allowed to keep. Granny Doyle had given it to her for Christmas, pleased that her plan had worked and that it was only a matter of months before some John Paul Doyle arrived into the world. Peg loved the photograph, even though her shoes were outside the frame. It was evidence that she was somebody who mattered, somebody who had once shared the sunlight with a pope. For years she clung to the sanctity of this snapshot, even when she might better have torn it in two. It captured the moment precisely: an island united, crowds of the devoted, everybody as happy as Heaven.

8

Bloody Tea Towel (1980)

The first miracle of John Paul Doyle was survival.

In other circumstances, the tea towel might have been kept for posterity, a version of Veronica’s sweat-soaked shroud. A former nurse, Granny Doyle cleaned up the kitchen her son couldn’t face. She picked up the chair that had fallen and scrubbed it down. She returned the phone to its table on the hall. She mopped the blood from the floor, decided it was best not to keep the mop. She scooped out the half-eaten breakfast cereal into the bin, washed and dried the bowl, returned it to the cupboard.

The tea towel was put in its own plastic bag and sealed in another bin-bag before it was thrown away.

9

Catherine Doyle Memorial Card (1980)

Danny Doyle lit another cigarette. He’d had to blow the smoke out the window, back when he was a teenager. Now it didn’t matter if the little room filled with smoke, with his Da dead and Granny Doyle too worn out to shout at him. She was busy with the babbies, leaving Danny to his old box room and its sad yellow aura, the source of which it was hard to locate. It couldn’t be the amber on the window from his smoking; the curtains were always drawn, especially in the day. The yellow of the curtains had faded to a pale primrose, hardly enough to explain the aura. So, it might just be the jaundice about his heart; what else was sad and yellow?

Another fag. Something to keep his hands busy. He wished there were cigarettes for the brain, something that his thoughts could wrap around and find distraction in. Brain cigarettes? He was going mad, he had to be. Sure you’re not high? That’s what she would have said, with an arch of her eyebrow – he could hear her voice clear as anything in the room – and Danny Doyle felt a sharp pain in his chest at the thought that the only place Catherine Doyle was in the room was trapped in a tiny rectangle.

There she was, smiling at him from a plastic memorial card. Her name (Catherine Doyle), her dates (1951–1979), some prayers and platitudes (May She Rest in Peace; Oh My Jesus, Forgive Us Our Sins and Save Us From the Fires of Hell). He’d let Granny Doyle pick the photo for the memorial card, and the sensible photo she’d chosen would not have been out of place in a Legion of Mary newsletter: this was not a Catherine Doyle he recognized. Surrounded by prayers and a pastel background, this woman was not the type to let toast crumbs fall onto a bed or push her face into silly shapes when Peg was taking a bath; this was not a woman who could quack. Staring at the memorial card, it was hard to remember the tone that she had used to tell the stories that put Peg to sleep or to admonish him when he’d forgotten to pick up milk, harder to imagine how ‘Danny’ might have sounded from her mouth, what shades of affection and exasperation might have coloured it.

Danny picked up the roll of film instead of another cigarette. Where could you take it? Not Brennan’s chemist. Nowhere on the Northside. Maybe some shop in town, some alley off O’Connell Street. But then, the thought of it, a stranger staring at her naked body, looking at him like he was some sort of pervert: he couldn’t do it.

Danny Doyle turned the capsule over and over in his hand, the single bed in his old box room already sagging with sadness underneath him.

10

Statue of the Sacred Heart (1980)

Peg stared at the holy water font in the hallway. It was one of the many features of 7 Dunluce Crescent that did not appear in her doll’s house. It was a small ceramic thing, hanging precariously by a nail, a picture of the Virgin Mary on the front. Much too high for Peg to dip her finger into, which meant she relied upon Granny Doyle or her father to bless her as she passed the threshold. Neither was particularly diligent. Peg felt that she’d lost two parents for the price of one. Danny Doyle spent all his days in the box room with the curtains shut, all the Lego castles that they were going to build forgotten in Baldoyle, along with everything Peg had ever cared about (her doll’s house; her shoebox; her life!). Granny Doyle was too busy charging about the house after the triplets to worry about the fate of Peg’s soul. Peg almost felt as if she were becoming invisible.

‘In or out, child, are you coming in or out?’

Granny Doyle still had eyes for Peg when she got in the way. Peg retreated down the dark hallway and left Granny Doyle to her chorus of old ladies. The triplets were asleep at the same time, so the chance to tell everybody just how busy she was could not be missed by Granny Doyle. Peg heard Mrs Fay’s warm voice and suppressed the desire to rush into the porch and see if she’d brought any sweets in her handbag. It wasn’t worth the fuss. Peg couldn’t face Mrs Nugent telling her that you’re a brave girl, aren’t you, love? or Mrs McGinty trying to find some softness in her face or Granny Doyle losing patience and banishing her outside, where she hadn’t a single friend to hopscotch beside. Besides, it wasn’t sweets Peg was after; she’d lost her whole life, even a Curly Wurly wouldn’t cut it.

Peg made her way into the empty sitting room, an eerie space with the telly turned off. The room had rules, invisible lines that demarcated territory as sharply as barbed wire. Granny Doyle sat in the armchair by the window, its cushions shaping themselves around her body, even in her absence. Danny Doyle took his father’s spot in the armchair by the television, dinner tray propped on his knees when he watched the football. Guests took their pick of the chairs by the wall. Peg might have switched on the telly or clambered onto one of the forbidden armchairs but what would be the point? How could she care about cartoons? There hadn’t been a television in her stately doll’s house, only a library with walls of miniature books that Peg had arranged carefully. Peg squeezed her eyes shut and longed for some magic to make her small and safe and transported inside the doll’s house but no, she was stuck in her stupid-sized body, too small to escape and too big to disappear.

Peg ambled past the dining room, with its mantelpiece filled with forbidden figurines, photos of people who Granny Doyle never saw, and postcards from places she had never been to. It was the nicest room in 7 Dunluce Crescent: sun streaming through the curtains and catching the dust in the afternoon. People hardly ever went inside, much less dined there.

Peg meandered towards the kitchen, the heart of the house. But what was here for her? No bright gingham tablecloth like in her doll’s house, for starters, only some grubby thing splattered with stains. The smell of bone soup and burnt rashers clinging to the curtains. More pictures of the Virgin Mary than Peg could count, as if she were a family member. And Granny Doyle’s wireless, the radio she kept on all day, so the patter of indignant listeners and reassuring men filled the room, no space for any thoughts.

If Aunty Mary had been visiting, Peg might have been able to escape to the back garden. Here at least was some quiet, the hedge nice and big to hide behind, a large stone where fairies could leave presents, so Aunty Mary said, her face gleeful when they overturned the slab and uncovered an old sixpence beside the scurrying woodlice. Aunty Mary had the key to the shed, too, and here, beside the reek of petrol from the lawnmower and the jumble of abandoned possessions, were piles of books in cardboard boxes. Peg longed to put them on a shelf and move them about until they were arranged by colour or size or whatever took her fancy. She couldn’t read them yet, but Aunty Mary left her be. No aren’t you a brave girl? or you’ll be a good girl and help your gran, won’t you? Aunty Mary even gave Peg some books with pictures, to be getting on with, while Peg took ‘a little break’ from school to help out her granny with the triplets. But Aunty Mary was in Galway, teaching other children. The back door was locked and Peg didn’t have the key, even if she could have reached the handle.

Aunty Mary might have understood why Peg was so upset at the loss of her copybook, another victim of the move. Peg had cried for a solid day when she realized her copybook was gone, her tears intensifying when Granny Doyle came home with a new one, its lines all the wrong size and none of Peg’s pictures or attempts at the alphabet preserved inside.

‘I want my copybook,’ Peg dared to say, face red with the rage, fists clenched at such an unjust world.

‘Ah love,’ Danny Doyle sighed, patting her on the head and shuffling up the stairs, no use, as usual.

‘I went to Nolans special for that,’ Granny Doyle said, in a voice that was trying to be nice, even as she opened up the impostor copybook.

‘I want my copybook,’ Peg repeated, wishing that Aunty Mary or her mother or somebody sensible were there, but she only had Granny Doyle, who turned to the counter and started to chop onions. Granny Doyle had a formidable back, which tensed to show just how much she wasn’t listening, but Peg wouldn’t let her win this fight. ‘I want my copybook,’ she howled, hoping that the words might smash windows or send the house tumbling down or right the ways of this wrong world. But all they did was send Granny Doyle’s hands to her brow, onions abandoned as she turned around.

‘Be quiet or you’ll wake the triplets.’

This could not stop Peg, whose words had turned into wails.

‘I want my copybook!’

‘Listen, Missy, I won’t tolerate this carry-on …’

Peg would carry on crying until she exploded, I want my copybook and I want my old house and I want my mammy clear in every scream and sob.

‘Just shut up!’

‘I want my copybook! I want—’

The slap pulled the air from Peg’s lungs. A quick tap across the face, it only stung for a second, but Peg felt the air in the room shift in that instant. Granny Doyle’s face reddened. She turned back to her onions as if nothing had happened, leaving Peg stock-still in the middle of the kitchen, her face turning white from the shock of it. Something her mother had never done. A violation. Peg knew then that her tears would be of no use here. She swallowed them inside, thinking that this was revenge of sorts. Fury filled her instead, a colder kind that kept her face pale. Her composure remained, even as Granny Doyle turned around in frustration – ‘see, you’re after waking the triplets’ – Peg’s mask fixed as Granny Doyle made a great show of taking away the new copybook and bringing it to ‘somebody who’ll appreciate all I do for them’. Lines had been drawn that day: there would be no more need for slaps or tears. Peg understood there was no out-wailing a baby; if she wanted her way in 7 Dunluce Crescent, she’d have to be inventive.

‘Are you all right, love? Would you not want to go outside and get some fresh air?’

It was Mrs Nugent, in to heat up the kettle for a fresh round of tea. This was all grown-ups did: made tea and smoked and offered Peg things she didn’t want.

‘I can see if my Clare’s ones are about? Tracey might even let you play with her new Barbie, though you’re not allowed to give it a perm, the cheek of her, trying to make it out like me! Though, I says, you’d be paying a lot more for a doll with this quality hair, wouldn’t you!’

Peg looked longingly out at the back garden, where the books Aunty Mary had brought were locked up in the shed. There wasn’t a hope that Mrs Nugent would read her mind.

‘Staying here to look after the young ones, are you, pet? Aren’t you a brilliant help to your gran? Janey, I wish some of my lot were more like you!’

Peg left Mrs Nugent, who continued to chat to the radio, and trudged upstairs. She would look in on her siblings, cosied up in their cots in the biggest room in the house. They weren’t even cute, like Peg’s doll. All they did was sleep and cry and stare, the last action being apparently a great achievement. ‘Isn’t he a great one for looking at you?’ the ladies in the porch said. ‘Oh, he’s a sharp one,’ Granny Doyle agreed. He was John Paul Doyle, the only one of the triplets who warranted such attention. Granny Doyle had recognized her future Pope immediately in the runt of the litter, the one who had struggled to stay alive. Granny Doyle knew that cunning trumped primogeniture and here was the Jacob to Esau, a battler who could cut the queue to the head of the Vatican: Ireland’s first Pope, John Paul Doyle!

A great one for his poos: that was how Peg saw John Paul. Helping Granny Doyle with the endless parade of cloth nappies through the house, Peg had excellent insight into the triplets’ characters. While Damien produced nice little nuggets of poo that could be easily cleaned up, John Paul’s explosive shits were messy and unpredictable. A testament to the luxury of riches that Granny Doyle piled upon him – for he would be the first to have a scoop of mashed potato; the baby who’d get the extra bit of bottle – but Peg knew that there was more to it than nurture: it was John Paul’s nature to cause trouble, something he excelled at.

Any sensible person would have placed their bets for papal stardom on the other two babies, docile creatures who were happier sleeping than staring. Damien had the capacity to sit quietly in his high chair; unlike John Paul, he did not need to play ‘food or missile?’ with every object that crossed his path. He was as placid as could be; he was doomed from the get-go.

Rosie was a trickier character to get a handle on. The only one named by her father, Rosie somehow managed to wriggle away from the moniker of ‘Catherine Rose Doyle’ before she could talk. Even as a baby there was something vague and dreamy about Rosie Doyle; she had none of the solidity of a ‘Rose’ or a ‘Catherine’. Against the perversity of John Paul and the purity of Damien, Rosie was a perpetual hoverer, a swirl of characteristics, none of them fussed enough to dominate. For the record, her poos, those reliable auguries of the future, were hard to classify, trickles that were neither solid nor liquid, not quite committing themselves to any shade of the spectrum.

One thing Peg was sure of: they were all united against her. If there were any magic to be found in 7 Dunluce Crescent, it was all concentrated in the triplets’ room; eerie the ways in which they seemed to be connected, as if some elastic band that Peg could never see looped them together. How else to explain how they could all wake up at the same instant or wail as one? Or not quite as one, Peg realized, as she creaked open the door innocently and peered at her slumbering siblings. John Paul woke the second she looked at him; she was sure of it. His little face looked up at Peg, cunning glinting in his eyes before he opened his mouth. The elastic band snapped into place and there the three of them were, miraculously awake and immediately furious at the world. That was the way of the triplets: John Paul set the tune and the other two followed. ‘Ssssh,’ Peg tried but it was hopeless. She could hear the commotion in the porch below; she’d be murdered.

Peg had a second to decide: try and placate the triplets or run and hide? Her legs made the choice immediately; in 7 Dunluce Crescent, escape was always the answer. She shot past her father’s closed door (as if he’d be any use) and dashed into her room. Well, Granny Doyle’s room with a camp bed in the corner and a chest of drawers for Peg, no space even for a shoebox. Peg’s heart raced as she heard Granny Doyle heave her way up the stairs. The triplets had only been down for the length of one cup of tea: she’d be mad. Peg examined the room for hiding places. There was the dusty wardrobe, no hope of Narnia behind Granny Doyle’s rain macs and dry-cleaned skirts. The covers of Granny Doyle’s big bed were an option, though the smell of Granny Doyle was enough to keep her away. Under the camp bed it was, a space Peg could just about crawl into. The walls were thin enough that Peg could hear Granny Doyle shush the triplets, John Paul cradled as she launched into some country lullaby.

Peg didn’t dare move, as much as she hated the room and its statue of the Sacred Heart. It wasn’t possible to switch it off, so Granny Doyle said, so Peg had to stare at the odd statue of Jesus, with his huge red heart, throbbing brightly in the dark. For some reason, it was the statue that made it hard for Peg to find sleep, not the restless triplets in the next room. Every night, she’d lie on the small camp bed, her body tight as a tin soldier, eyes fixed on the pulsating red candle. Granny Doyle had shared the room with the Sacred Heart since her wedding night. If the statue’s light had bothered her once, it didn’t now, and her snores always filled the room before Peg’s sobs.

At least he wouldn’t tell on her, Peg thought, peeping out from under the bed to stare at Jesus. He was too busy with his heart that never stopped beating, even after death: he wasn’t bothered with the misdeeds of Peg Doyle. Nor were any of the statues or pictures of the Virgin Mary, when she thought of it. Whatever Peg did – spitting out Granny Doyle’s soup or stealing a glimpse into the dining room – had no impact on the serene smiles of the Virgin Marys dotted throughout the house. She could become invisible, Peg decided; a thought to chew on. He’d keep her secret, this statue of the Sacred Heart, not a word out of him, even as Peg heard Granny Doyle cart the triplets downstairs, the hope of rocking them to sleep surrendered.

Peg would stay here until she was caught, she decided, settling into the carpet. She dug in her elbows, ready to wait Granny Doyle out. An hour passed. Two. Peg smelled the whiff of cabbage and pork chops from the kitchen: surely Granny Doyle would fetch her now. But no, Peg heard Granny Doyle’s footsteps up and down the stairs as she delivered a tray to her father’s room, no thought to check in on Peg. Tears welled up in Peg’s eyes, their provenance unclear, as she probably wouldn’t be in trouble now. Yet to be invisible had its own hardships, the statue of the Sacred Heart’s expression unmoved by her tears, its heart continuing to flicker as night crept into the room.

It was as if the statue knew, Peg thought, years later: the statue understood that 7 Dunluce Crescent was impossibly small for all the people and feelings it was suddenly asked to contain. From the beginning, the house had been impatient to expel some of its new inhabitants, unable to contain the miracles that would push against its walls. The statue intuited this: perhaps it even anticipated the trouble that would come, the sights it would be forced to witness. Yet it kept beating on, even as dark filled every corner of the room, while Peg sobbed herself to sleep.

The statue saw what Peg didn’t: the heave of relief when Granny Doyle found her, the sign of the cross, the kiss. Granny Doyle managed to shift Peg’s floppy limbs into the camp bed. She pulled the covers around her, bewildered at the devilment that such a quiet thing could get up to.

Little do you know, the statue might have said, for surely it intuited everything that Granny Doyle and Peg would do and say to each other before their histories ran out. It kept quiet, its scarlet candle throbbing away, its lips frozen in a solemn smile, its hands outstretched in a gesture of compassion, though they were made of stone, and limited, ultimately, in their ability to provide aid.

Series II:

Beatification (#ua7f65e4a-e754-5b6c-abf8-3078013cdb95)

(2007)

1

Rosemary and Mint Hotel Shampoo (2007)

Kiss to say, honey, I’m home.

‘Hello, Mrs Sabharwal.’

Peg rolled her eyes.

‘I’ve told you, I’m not changing my name.’

‘I know, but today—’

‘That’s not how it works, you don’t own me because a year has passed, I’m not a washing machine that you bought in Walmart.’

A smile from Devansh.

‘You remembered!’

Kiss to say, of course you remembered.

Pause to savour the scent of New York City on an April evening: young love and fast food and the promise of heat.

Pause to detect something else.

‘You smell nice!’

‘Don’t sound so surprised.’

‘What is that smell?’

‘I showered after swimming. Borrowed some lady’s fancy shampoo.’

Kiss to avoid questions about rosemary and mint hotel shampoo.

Kiss to avoid questions about what Peg was doing in a hotel on a Tuesday afternoon.

Peg removed the wine and take-out containers and brandished a brown paper bag.

‘One year: paper!’

Kiss to reward ingenuity.

‘Sorry, I didn’t know you were going to cook.’

‘We can have a feast.’

‘We can’t have Chinese with pasta.’

‘Why not?’

‘I’ll put some of this in the fridge …’

‘Come here.’

Kiss to stop motion.

‘You are looking sexy today!’

Peg opened the wine.

‘Today?’

Kiss to demonstrate love in the face of provocation.

‘You know I’d never be down on the librarian chic.’

‘I know.’

Peg found a way to take a sip of wine.

‘I had a meeting in the morning with a potential dissertation supervisor.’

‘And you thought you’d seduce them into accepting you.’

‘Exactly.’

A gulp of wine to wash down a lie.

‘Let me know if you need a reference. I’m happy to vouch for your many attributes.’

‘Generous.’

‘I’ll write a letter about your exceptional fingers which are excellent at typing …’

Kiss to demonstrate a relationship between word and thing.

‘… and I can recommend your ears which can listen to lots of lectures …’

Kiss to tickle.

‘… and these eyes …’

Kiss to touch.

‘I’m starting to feel like Red Riding Hood.’

‘Does that make me the wolf?’

‘Mmmm, you’re more of a bear.’

Kiss to say, fuck you, my love.

Kiss to say, Happy Wedding Anniversary.

Kiss to say, let’s fuck across the counter amid knives and chopped peppers.

Kiss to say, yes.

Kiss to say, let’s go.

Kiss to say, but not now, first, the dinner.

Pause to chop basil and let feelings settle.

‘So, Ashima asked me to be Sara’s godfather.’

‘What?’

‘They’re having her baptized. You know what Gabriel’s like and Ashima doesn’t care but she thinks she can get Sara into some fancy-ass Catholic school, like she can’t think of a worse fate for her child than public school.’

Shoulder-rub to comfort an underpaid, overworked public high school teacher.

‘You think I’m godfather material?’

‘Keep up that belly you’ll be fat enough.’

‘Whata ar’ya talkin’ about?’

Kiss to stop impersonations.

‘I couldn’t go to the gym today; I was doing important research about this godfathering business.’

Peg walked over to Dev’s laptop, knowing, before she looked, the site that would be open.

‘Wikipedia is gymnastics of the mind.’

‘Ha.’

‘And I’ve been getting this sauce ready.’

Kiss to display gratitude.

Kiss to atone for judgement of Wikipedia reading and editing as an appropriate pastime.

Kiss to atone.

Pause to acknowledge the difficulty of approaching the topic of Peg Doyle’s family.

‘What were your godparents like?’

Peg’s godmother was Aunty Mary.

‘I’m not really in touch with them.’

But what was there to say about Aunty Mary?

‘Were they relatives?’

Irish women disappeared from time to time and that was how it went.

‘My godparents weren’t really that important.’

And then they died and upturned your life in exile, but Dev couldn’t possibly know about that; Peg had been careful not to show him the letter.

‘Thanks.’

Kiss to acknowledge the appeal of pretend-hurt Devansh Sabharwal.

Kiss to avoid further questions.

‘The main requirements are enough money to stuff a card, the ability to remember the kid’s name, and, as far as I’m aware, being a Catholic.’

‘Two out of three ain’t bad? Ashima says they’re being flexible about it. I guess it’s silly. It’s not like I’m going to start believing that dead dudes can make miracles.’

Tiny pause to tense at where the conversation was headed and search for any way to stop it.

‘Did you see the news? Pope John Paul II is on his way to becoming a saint.’

A gulp of wine to wash down a lie.

‘No.’

‘Yeah! Mad isn’t it, only two years since he’s dead and already they’ve found some evidence of a miracle so he’s halfway to being …’

She had the word in her head, despite everything.

‘Beatified.’

‘Right! I guess some guy in France claims that praying to the Pope cured his Parkinson’s so now the Pope just needs one more miracle and he’s Mr Beatified. Record time: it can take decades.’

‘I guess men are working out their minds on Wikipedia across the world.’

‘Ha! Yeah, I guess I got a bit distracted this afternoon … you know who else has a Wikipedia page?’

Pause to banish all conversation about the past.

‘Pope John Paul III!’

Wine to wash away lies.

‘I hadn’t seen.’

‘More than just a stub too, lots of links to YouTube and some interviews and …’

Move to the counter to banish all possibility of conversation about John Paul Doyle.

Pause to drain pasta and bitterness.

‘So you’re going to become a godfather?’

‘I know, it’s silly … I definitely can’t provide spiritual guidance …’

Bite of lip to suppress knowledge of upcoming joke.

‘Or any guidance, ha! And I don’t want to be in the middle of one of Ashima’s and Gabriel’s fights. It’s just, Sara is a great kid, you know? And it’s nice to have that kind of official connection to a kid, especially if we’re not …’

Pause to imagine children in subjunctive tenses.

Kiss to acknowledge vulnerability.

‘You’d be a brilliant godparent.’

Tiny pause to say farewell to children in subjunctive tenses.

‘Well, it’s not like I have to do it: you don’t even remember yours.’

Wine to wash down a lie.

‘No.’

What was there to say about Aunty Mary? Fairy godmothers were for children, you couldn’t ask them to stick around.

‘I’m still her uncle.’

Irish women disappeared from time to time and that was how it went.

‘I’ll still be part of her life.’

That was the path of the Doyle women (Aunty Mary; her mother; Rosie; Peg): the only way to survive exile was to forget.

‘Peg?’

Wine to wash away the past.

‘You okay?’

Kiss to wash away lies.

‘Yeah.’

2

Box of Memorial Cards (2007)

Would the Pope be getting one too? Surely, he would, with the millions who’d want to be remembering him, and who could keep track of everybody who’d passed without the handy rectangles that memorialized people? Not Granny Doyle. The balance had tilted, so that she knew more who were dead than alive; she’d be lost without her little box of laminated lives. She sat in her porch and flicked through her box of memorial cards and wondered if the Vatican had ever made a memorial card for Pope John Paul II: he was two years gone, after all, they’d plenty of time. There might even be a special memorial card now that he was bound to be beatified: some poor crater cured of Parkinson’s, already. She might have to start a new box; maybe she’d set up a special one for celebrities. Daft thoughts, she didn’t know any celebrities and, in any case, there wouldn’t be a special memorial card for the Pope – she had just checked, she hadn’t any for poor John Paul I – and Granny Doyle would have to wait for somebody else to die before she’d start a new box.

‘Daft,’ Granny Doyle said, though the radio on the chair opposite her didn’t respond. Some new yoke that John Paul had got her: Granny Doyle could swear that the news had got worse because of it. No mention of the Pope’s miracle, never any good news, only some eejit jingling on about the upcoming election (as if she’d ever betray Fianna Fáil) and the nurses on strike (never in her day) and people killing each other from Mogadishu to Kabul while ads jittered on about things she didn’t want: it was enough to send her to bed.

‘It’s a terrible world we live in,’ Granny Doyle said, although the folding chairs were silent. Poor Mrs Nugent had settled into her box of memorial cards a long time ago and her daughters hadn’t picked well at all; Mrs Nugent would have died a second death at the sight of the blotches and wrinkles in the photo. Mrs Fay hadn’t been the same since Mr Fay passed a year ago, though she at least had done well enough to pick a picture where he still had a healthy batch of hair. Mrs McGinty was still going (she’d live to a hundred; indignation would power her that far) but they weren’t talking to each other after the Pope John Paul III business. A shame, because the car outside Irene Hunter’s had been parked there all night and the Polish crowd renting Mr Kehoe’s house had received three packages in the space of an hour and all of that would have been enough to sustain the conversation for the morning.

‘Daft,’ Granny Doyle said, but the only occupants of her folding chairs were bits of plastic. Some new phone that John Paul had got her, with a camera on it, as if she wanted to be documenting her wrinkles. The new radio. And the Furby he’d got her, years ago, when she wanted company in the house but didn’t want some yappy dog or cat conning her out of cream. A daft thing it was, gibberish spouting out of its beak most days, but she had let John Paul keep it stocked on batteries, had bought them herself when he forgot. It was nice to have a voice in the house, even if all it said was ‘weeeeeee!’ or ‘me dance’ or ‘Furby sleep’. Nice to have some intelligent conversation, Granny Doyle would say, a joke between her and John Paul, something to be treasured, the thought that he was worried about her being lonely. And yet, if he were really worried about her being lonely, wouldn’t he stay over some nights like she asked?

‘Ah, well,’ Granny Doyle said, looking over at the blob of purple and yellow plastic.

You can teach it to talk, John Paul had said, back when he visited.

That thing looks like a demon, Mrs McGinty said, back when they were still talking.

Isn’t it lovely? Mrs Fay said, back when she still had some semblance of wits about her.

The Furby sat on the chair and slept. It spent most of the day sleeping, a sign of its intelligence. Granny Doyle stroked its fur but its eyes didn’t open; probably for the best – it could scare the wits out of you with its laugh. She might have forgotten to put the batteries in. She could ask John Paul to get her some, but he’d just get them delivered, along with all her messages, which was a shame when the truth of it was she didn’t mind about the milk – most of it ended up down the sink – it was her family she was starved of. Her fingers found her son’s memorial card: a fine man he looked, there. Funny how photographs couldn’t capture the size of a person. Mrs Nugent was diminished; no rectangle could capture the gossipy-eyed glory of the woman. Danny Doyle, on the other hand, looked bigger. A man who could build an empire, you might have thought. Well. She moved to the next one and there was Catherine Doyle, the dutiful daughter-in-law who’d left Granny Doyle three squalling terrors to rear instead of the one. And where were they now? Not in her box, thanks be to God, but the triplets had left her in an empty house, again. Not to mention Peg, a name like a paper-cut. Granny Doyle stiffened in her chair: no need to be remembering any of them. People made their beds; they lay in them. Except people never did make their beds properly any more, not the way her mother had taught her, not the way she had when she was a nurse, and this was a strange thing to be missing, to feel a pang for the house with all its perfectly made beds and nobody to lie in them.

‘Daft thoughts,’ Granny Doyle said, though the Furby stayed asleep.

She put the box of memorial cards under her folding chair; she couldn’t remember why she’d picked it up in the first place. A dangerous thing to be doing, the past waiting to ambush you with each turn of the card, and the threat of tears too, daft, when Granny Doyle had never been a crier. Still, now she was, tears surprising her at strange times; it struck her that there might be a medical solution, some sort of hip replacement for the heart, or at least the eyes. In the meantime, she had banned onions from the kitchen.

The Pope! That was why she had fished out the box. Two years dead, the poor man, and her knees couldn’t make it to the church to light a candle for him. She could have asked John Paul to drive her to the church, in a different life, where he hadn’t torn the heart out of her. Would Pope John Paul II be getting a card? She couldn’t remember what she had decided and she couldn’t ask Mrs McGinty. She decided instead to root out the old photos from Phoenix Park; she’d battle the stairs if she had to.

Or, she could ask John Paul to bring down a box of old photos for her; he couldn’t hire a company to do that. He was a good lad, despite everything that he’d done. He’d come if she called, if she could ever figure out which buttons on the phone to press. John Paul Doyle at least had turned out … well caught in her mind, impossible to add, because whatever successes John Paul Doyle had achieved, she couldn’t say that any of it had turned out as she’d planned, that giddy day when she’d practically conjured him into being. He might visit that weekend, yet, and the intensity of this desire – that John Paul sit beside her in the church for everybody to see – bowled her over, and she felt a hot liquid prick her eyes, and then somehow she was thinking about her other grandchildren, Damien and Rosie and Peg, taboo subjects, all of them.

The Furby opened its bright yellow eyes. Sometimes Granny Doyle wondered if Mrs McGinty was right: perhaps the creature was diabolical. Some dark nights, Granny Doyle wondered if the contraption had the voices of the disappeared trapped inside: perhaps it was on this earth to judge her. Daft thoughts – John Paul had only bought it as a joke. Still, she kept the batteries in it. Still, she was glad of its gabble, happy to have any sound in the house. Still, she chanced the name.

‘Peg?’

The sly old thing went back to sleep; if it had the voices of the disappeared inside, it wasn’t sharing them.

3

Clerys Clock (2007)

You’re a dirty pervert, Damien Doyle imagined Mark saying, once he arrived, feeling flushed at the thought of just how excited this sentence made him feel. He covered his blush with the Irish Times, sure that the O’Connell Street crowds were judging him, though they kept on walking. Damien stole another glance up at Clerys Clock, that grand structure that jutted out from the side of the department store and portioned out the city’s time. The minute hand was closer to a quarter past; Mark was late. Mark was always late but Damien couldn’t help his own punctuality; even the thought of turning up a few minutes late caused him distress. Besides, he didn’t mind the wait; this was still novel, having somebody to wait for. A lover. Only lovers met under Clerys Clock, so the story went. Damien conjured visions of smartly dressed men waiting outside the grand department store, their hearts lifting at the sight of some pretty girl in a smock, rushing from some country train, stopping her step to a stroll, as Clerys’ clockwork took over, sweethearts confidently tick-tocking towards each other for decades. Sweethearts who probably didn’t call each other dirty perverts, Damien imagined, blushing again at this subversive meeting place: it was just possible that Clerys Clock might crash to the ground in protest.

Damien flicked through the Irish Times for distraction. He was the only eejit waiting under the clock – everybody had mobiles now, sure – and he wanted to project the impression of an upright citizen and not the kind of man waiting for the touch of his boyfriend’s tongue in his ear. So, the news. More of the same: trouble in hospitals and protests against Shell in Mayo and the election in the air. The Greens had managed to nab a small piece about their education manifesto on page 4 but it was dwarfed by a story about the government’s new climate change strategy, irritating when the Greens could use better coverage if they were going to gain seats, which they were: they had to! Damien skimmed the rest of the paper, only stopping once he found a picture of Brangelina, which sent his brain on a worried spiral about whether ‘Marmien’ was a worse couple name than ‘Dark’ until—

‘Look at you, ogling Brad Pitt in broad daylight, you big pervert.’

Mark, surprising him as always, bounding up out of nowhere.

A quick kiss, the Irish Times and Brad Pitt quickly folded into Damien’s satchel.

‘You know only grannies and boggers meet under Clerys Clock?’ Mark said.

And lovers, Damien almost said, though he held the words inside.

‘I’m just appeasing your inner bogger—’

‘I’m from half an hour out of Belfast!’

‘“Bogger” just means “not from Dublin”.’

‘Sounds right. You, my love, are definitely an auld granny.’

‘Feck off, you stupid bogger.’

Another kiss, right in the middle of O’Connell Street, grannies and boggers be damned.

This was new for Damien, all these actions that Mark could do so unconsciously – kissing a man in the street or holding hands with a man in town, not wondering whether Mrs McGinty or Jason Donnelly or who knew who would be turning off Talbot Street. Damien looked up at Clerys Clock ticking away; perhaps it had seen worse. Damien felt more self-conscious on the Northside, especially O’Connell Street; this, after all, was the home of religious nuts, where Damien himself, in his Legion of Mary days, had held up placards and bellowed chants against abortion alongside Mrs McGinty. Though the fanatics had been moved along, exiled with the Floozy in the Jacuzzi, no sign of Granny Doyle, more space on the path for more types of people, and of course –

‘That fucking yoke,’ Mark said, weaving around the Spire and the circle of tourists. Mark couldn’t walk past the Spire without a mini-rant; Damien could have set his watch by it.

‘Wasn’t Nelson’s Phallic Pillar enough? Why did they need to build another giant penis? We keep shunting shite towards the sky, all part of the same problem – instead of making space to talk to each other we keep blocking the view.’

They had reached The Oval (Damien would have preferred the Front Lounge, but Mark only drank in old-man bars), Damien getting in the Guinness while Mark continued talking. ‘The same problem’ was the subject of the dissertation that Mark sometimes worked on: ‘The Celtic Tiger Eats the Commons, 1973–2002’.

‘It’s the same shite as shopping centres. We used to have squares to discuss ideas in, now we have The Square. A great name, sounds like a place you’d want to visit and then it turns out to be an air-conditioned tomb full of stereos and shite. It’s a smart trick, usurp the language of the thing you displaced: gouge out a valley and then call the monstrosity you plonk there Liffey Valley, brilliant really. But what we need is a square where we can share ideas instead of buy shite, you know?’

Damien did know; he’d heard this part of the dissertation before. Now that he was sure the bartender couldn’t, in fact, be somebody from Dunluce Crescent, Damien relaxed and basked in Mark’s monologue. Too many words, too many ideas to implement, but wasn’t the Green Party the space for that and Mark was one of their best volunteers. Damien took another sup and admired everything about Mark: the frayed Aran jumper that he’d worn since the last millennium; the big hands that moved too much when he talked; the blue eyes that didn’t move at all, lasered in on you, so that you could see every fleck of brown or grey in them, eyes that never seemed to need a blink or a break. Meanwhile, brightly coloured insects pirouetted in the region of Damien’s diaphragm, the words fresh, even after a year: my boyfriend.

‘… and this is why we need a space to freely debate ideas!’

Damien refocused. Mark had fished out the Irish Times to mop up some spilt beer and this was an article that Damien had missed: something about Pope John Paul II being beatified, not an election issue in Damien’s opinion, though there was no telling what would get Mark going.

A thing to love about Mark: he could be so single-minded, wouldn’t be swayed by any trivial distractions once he got going.

‘Fuck all this hagiography shite! Nobody has the balls to say anything genuine when a famous person dies.’

‘I suppose people need a period of mourning,’ Damien dared.

‘No,’ Mark almost shouted. ‘All this respect the dead stuff is just a way for the right wing to solidify their myths. It was the same with Reagan: the years after a public figure dies are the critical moment when their legacy is sculpted. You have to scrawl your graffiti before the concrete sets. Nobody has the balls to call the Pope out for some of his shite: preaching that condoms are a sin in Tanzania while people are dying of AIDS. It’s fucked up that this is what makes saint material …’

Damien took a sup of Guinness and nodded; it would be a while before Mark reached his pint or his point. He had to divert conversation from the Pope, away from any talk of Pope John Paul III. It had been years since he’d talked to his brother properly, not since that business, plenty of periods in Damien’s past that he skipped over euphemistically. That other business, with Peg, who Damien definitely didn’t want to think about. Damn the lot of the Doyles, Damien thought, nothing like family to stuck-in-the-mud you in the past, when Damien aspired to be all future. This focus on the future was what he loved about working for the Green Party, a political organization for the twenty-first century, not one rooted in the bogs of some civil war best forgotten, and here was the thing to steer them away from popes.

‘Don’t worry, babe, once I’ve got a new office in Leinster House, I’ll keep you a section of wall to graffiti whatever you want.’

A thing to love about Mark: his eyes were only gorgeous, even mid-roll.

‘Right,’ Mark said. ‘The whole country’s going to change with this election.’

It was, though; Damien knew it.

‘You won’t be able to move with the paradigms shifting each other when the Greens get seven seats—’

‘When we get ten seats,’ Damien corrected him. ‘And yes, it’ll be all change. Catholic Ireland is dead and gone: it’s with Pope J.P. in the grave!’

A thing to love about Mark: he was a great at impersonating radio talk-show hosts.

‘The question is, how can we as a nation come up with ethical values that aren’t tied to religion or nationalism? The question is, how do we become a people defined by the future rather than the past? Catholicism has been swept clear away, the question is how can we fill that gaping hole?’

‘What was that you said about filling a hole?’

Mark laughed.

‘Are you pissed already?’

‘I am!’ Damien announced, fizzy with the feeling; he felt drunk all the time now, even when he hadn’t touched a drop.

4

Mitre (2007)

John Paul Doyle smiled. Smiling was his speciality: popes needed as many grins in their repertoire as politicians. A smile can take you further than a sentence, John Paul thought, something he’d write down, once he was reunited with his BlackBerry. It could be material for his biography. Or for a stand-alone stocking filler. Or, better, a self-help tome, paired with an exclusive seminar on smile-coaching. John Paul’s fingers twitched; he was lost without his BlackBerry to record the thousand and one ideas that pinballed about his brain and he was on form that morning, odd as coke wasn’t even involved: it must be the fresh air. Another idea: find something to bottle the fresh air here – a net? A bottle? – and ship it out to Dublin. Atlantic Air! John Paul was sure some eejits would drop a tenner for a sniff. He gulped in a lungful and let out a huge nowhere I’d rather be than on the edge of the Atlantic in a pair of boxers and a pope hat! beam.

In his few hours in Clougheally, John Paul had already trotted out several different smiles.

A Pope John Paul III has arrived in Clougheally! megawatt grin unleashed that morning.

A secret yeah, this kip is Clougheally, nice eh? smile flashed to the camera-guy.

A so nothing’s changed and here I am, back half-smile all for himself.

A fuck this fresh air! grin and yelp for the benefit of the camera-guy, as he stripped to his boxers.