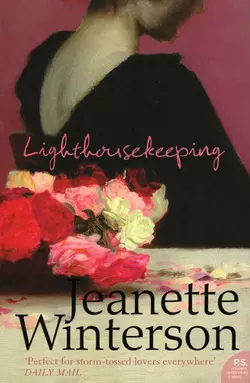

Lighthousekeeping

Jeanette Winterson

From one of Britain’s best-loved literary novelists comes a magical, lyrical tale of the young orphan Silver, taken in by the ancient lighthousekeeper Mr. Pew, who reveals to her a world of myth and mystery through the art of storytelling.Motherless and anchorless, Silver is taken in by the timeless Mr. Pew, keeper of the Cape Wrath lighthouse. Pew tells Silver ancient tales of longing and rootlessness, of the slippages that occur throughout every life. One life, Babel Dark’s, a nineteenth-century clergyman, opens like a map that Silver must follow, and the intertwining of myth and reality, of storytelling and experience, lead her through her own particular darkness.A story of mutability, talking birds and stolen books, of Darwin and Stevenson and of the Jekyll and Hyde in all of us, Lighthousekeeping is a way into the most secret recesses of our own hearts and minds. Jeanette Winterson is one of the most extraordinary and original writers of her generation, and this shows her at her lyrical best.

Lighthousekeeping

Jeanette Winterson

For Deborah Warner

‘Remember you must die’

MURIEL SPARK

‘Remember you must live’

ALI SMITH

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#u1612e824-c976-5a54-849f-73c466b90e98)

Title Page (#ub6359308-b268-5d69-a219-39c09a193115)

Epigraph (#u8991553c-7e17-570b-a16a-abeab219c429)

TWO ATLANTICS (#u844e4ef5-2721-58cb-b9c8-991a43676eaf)

My mother called me Silver. I was born part precious metal part pirate. (#u339d5615-3b08-5fd5-8ced-df7ec06fe1b5)

A beginning, a middle and an end is the proper way to tell a story. But I have difficulty with that method. (#ufaee3da3-90c4-504d-b0d9-c8a080f6665c)

KNOWN POINT IN THE DARKNESS (#u0a7c9d0f-b1e3-5a04-ae74-a14a112441d3)

As an apprentice to lighthousekeeping my duties were as follows: (#ub84c7581-9ed7-5098-86ff-a883156605c8)

Cliff-perched, wind-cleft, (#ud3fd9560-316c-573b-af09-cdadc13dfb1c)

Tell me a story, Pew. (#uedf979d5-ea0e-577b-b0b1-a679a6dbb71a)

To make an end of it Dark had decided to marry. (#u032857ce-774e-5658-86e1-2eabe2057fdf)

TENANT OF THE SUN (#litres_trial_promo)

The moon shone the night white. (#litres_trial_promo)

The door was his body. (#litres_trial_promo)

Tell me the story, Pew. (#litres_trial_promo)

GREAT EXHIBITION (#litres_trial_promo)

This way to the Cobra. Wonders of the East! (#litres_trial_promo)

Pew – why didn’t my mother marry my father? (#litres_trial_promo)

A stranger in his own life, (#litres_trial_promo)

How were you born, Pew? (#litres_trial_promo)

The mystery of Pew was a mercury of fact. (#litres_trial_promo)

That day in the lighthouse (#litres_trial_promo)

Eyes like a faraway ship, Pew was sleeping. (#litres_trial_promo)

Tell me a story, Pew. (#litres_trial_promo)

A PLACE BEFORE THE FLOOD (#litres_trial_promo)

Dark was walking his dog along the cliff path (#litres_trial_promo)

It was our last day as ourselves. (#litres_trial_promo)

A place before the Flood. (#litres_trial_promo)

Tell me a story, Silver. (#litres_trial_promo)

NEW PLANET (#litres_trial_promo)

This is not a love story, but love is in it. That is, love is just outside it, looking for a way to break in. (#litres_trial_promo)

Dark was looking at the moon. (#litres_trial_promo)

I sometimes think of myself, up at Am Parbh. (#litres_trial_promo)

TALKING BIRD (#litres_trial_promo)

Two facts about Silver: It reflects 95% of its own light. It is one of the few precious metals that can be safely eaten in small quantities. (#litres_trial_promo)

The seahorse was in his pocket. (#litres_trial_promo)

1859 (#litres_trial_promo)

Tell me a story, Silver. (#litres_trial_promo)

SOME WOUNDS (#litres_trial_promo)

Some wounds never heal. (#litres_trial_promo)

The pot of Full Strength Samson was finished. (#litres_trial_promo)

Tell me a story, Silver. (#litres_trial_promo)

Love is an unarmed intruder. (#litres_trial_promo)

Pew (#litres_trial_promo)

THE HUT (#litres_trial_promo)

This is a love story. (#litres_trial_promo)

His heart was beating like light. (#litres_trial_promo)

Tell me a story, Silver. (#litres_trial_promo)

Part broken part whole, you begin again. (#litres_trial_promo)

P.S. (#litres_trial_promo)

About the author (#litres_trial_promo)

From Innocence to Experience (#litres_trial_promo)

LIFE AT A GLANCE (#litres_trial_promo)

WRITING LIVES (#litres_trial_promo)

Top Ten Books (#litres_trial_promo)

About the book (#litres_trial_promo)

Endless Possibilities (#litres_trial_promo)

Read On (#litres_trial_promo)

Have You Read? (#litres_trial_promo)

Find Out More (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise (#litres_trial_promo)

By the same author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

TWO ATLANTICS (#ulink_1f22101e-7721-5e5c-a0c4-997a771a2f37)

My mother called me Silver. I was born part precious metal part pirate. (#ulink_66b79f8e-de29-5d98-95d1-1411546b98d3)

I have no father. There’s nothing unusual about that, even children who do have fathers are often surprised to see them. My own father came out of the sea and went back that way. He was crew on a fishing boat that harboured with us one night when the waves were crashing like dark glass. His splintered hull shored him for long enough to drop anchor inside my mother.

Shoals of babies vied for life.

I won.

I lived in a house cut steep into the bank. The chairs had to be nailed to the floor, and we were never allowed to eat spaghetti. We ate food that stuck to the plate – shepherd’s pie, goulash, risotto, scrambled egg. We tried peas once – what a disaster – and sometimes we still find them, dusty and green in the corners of the room.

Some people are raised on a hill, others in the valley. Most of us are brought up on the flat. I came at life at an angle, and that’s how I’ve lived ever since.

At night my mother tucked me into a hammock slung cross-wise against the slope. In the gentle sway of the night, I dreamed of a place where I wouldn’t be fighting gravity with my own body weight. My mother and I had to rope us together like a pair of climbers, just to achieve our own front door. One slip, and we’d be on the railway line with the rabbits.

‘You’re not an outgoing type,’ she said to me, though this may have had much to do with the fact that going out was such a struggle. While other children were bid farewell with a casual, ‘Have you remembered your gloves?’ I got, ‘Did you do up all the buckles on your safety harness?’

Why didn’t we move house?

My mother was a single parent and she had conceived out of wedlock. There had been no lock on her door that night when my father came to call. So she was sent up the hill, away from the town, with the curious result that she looked down on it.

Salts. My home town. A sea-flung, rock-bitten, sand-edged shell of a town. Oh, and a lighthouse.

They say you can tell something of a person’s life by observing their body. This is certainly true of my dog. My dog has back legs shorter than his front legs, on account of always digging in at one end, and always scrambling up at the other. On ground level he walks with a kind of bounce that adds to his cheerfulness. He doesn’t know that other dogs’ legs are the same length all the way round. If he thinks at all, he thinks that every dog is like him, and so he suffers none of the morbid introspection of the human race, which notes every curve from the norm with fear or punishment.

‘You’re not like other children,’ said my mother. ‘And if you can’t survive in this world, you had better make a world of your own.’

The eccentricities she described as mine were really her own. She was the one who hated going out. She was the one who couldn’t live in the world she had been given. She longed for me to be free, and did everything she could to make sure it never happened.

We were strapped together like it or not. We were climbing partners.

And then she fell.

This is what happened.

The wind was strong enough to blow the fins off a fish. It was Shrove Tuesday, and we had been out to buy flour and eggs to make pancakes. At one time we kept our own hens, but the eggs rolled away, and we had the only hens in the world who had to hang on by their beaks while they tried to lay.

I was excited that day, because tossing pancakes was something you could do really well in our house – the steep slope under the oven turned the ritual of loosening and tossing into a kind of jazz. My mother danced while she cooked because she said it helped her to keep her balance.

Up she went, carrying the shopping, and pulling me behind her like an after-thought. Then some new thought must have clouded her mind, because she suddenly stopped and half-turned, and in that moment the wind blew like a shriek, and her own shriek was lost as she slipped.

In a minute she had dropped past me, and I was hanging on to one of our spiny shrubs – escallonia, I think it was, a salty shrub that could withstand the sea and the blast. I could feel its roots slowly lifting like a grave opening. I kicked the toes of my shoes into the sandy bank, but the ground wouldn’t give. We were both going to fall, falling away from the cliff face to a blacked-out world.

I couldn’t hang on any longer. My fingers were bleeding. Then, as I closed my eyes, ready to drop and drop, all the weight behind me seemed to lift. The bush stopped moving. I pulled myself up on it and scrambled behind it.

I looked down.

My mother had gone. The rope was idling against the rock. I pulled it towards me over my arm, shouting, ‘Mummy! Mummy!’

The rope came faster and faster, burning the top of my wrist as I coiled it next to me. Then the double buckle came. Then the harness. She had undone the harness to save me.

Ten years before I had pitched through space to find the channel of her body and come to earth. Now she had pitched through her own space, and I couldn’t follow her.

She was gone.

Salts has its own customs. When it was discovered that my mother was dead and I was alone, there was talk of what to do with me. I had no relatives and no father. I had no money left to me, and nothing to call my own but a sideways house and a skew-legged dog.

It was agreed by vote that the schoolteacher, Miss Pinch, would take charge of matters. She was used to dealing with children.

On my first dismal day by myself, Miss Pinch went with me to collect my things from the house. There wasn’t much – mainly dog bowls and dog biscuits and a Collins World Atlas. I wanted to take some of my mother’s things too, but Miss Pinch thought it unwise, though she did not say why it was unwise, or why being wise would make anything better. Then she locked the door behind us, and dropped the key into her coffin-shaped handbag.

‘It will be returned to you when you are twenty-one,’ she said. She always spoke like an Insurance Policy.

‘Where am I going to live until then?’

‘I shall make enquiries,’ said Miss Pinch. ‘You may spend tonight with me at Railings Row.’

Railings Row was a terrace of houses set back from the road. They reared up, black-bricked and salt-stained, their paint peeling, their brass green. They had once been the houses of prosperous tradesmen, but it was a long time since anybody had prospered in Salts, and now all the houses were boarded up.

Miss Pinch’s house was boarded up too, because she said she didn’t want to attract burglars.

She dragged open the rain-soaked marine-ply that was hinged over the front door, and undid the triple locks that secured the main door. Then she let us in to a gloomy hallway, and bolted and barred the door behind her.

We went into her kitchen, and without asking me if I wanted to eat, she put a plate of pickled herrings in front of me, while she fried herself an egg. We ate in complete silence.

‘Sleep here,’ she said, when the meal was done. She placed two kitchen chairs end to end, with a cushion on one of them. Then she got an eiderdown out of the cupboard – one of those eiderdowns that have more feathers on the outside than on the inside, and one of those eiderdowns that were only stuffed with one duck. This one had the whole duck in there I think, judging from the lumps.

So I lay down under the duck feathers and duck feet and duck bill and glassy duck eyes and snooked duck tail, and waited for daylight.

We are lucky, even the worst of us, because daylight comes.

The only thing for it was to advertise.

Miss Pinch wrote out all my details on a big piece of paper, and put it up on the Parish notice board. I was free to any caring owner, whose good credentials would be carefully vetted by the Parish Council.

I went to read the notice. It was raining, and there was nobody about. There was nothing on the notice about my dog, so I wrote a description of my own, and pinned it underneath:

ONE DOG. BROWN AND WHITE ROUGH COATED TERRIER. FRONT LEGS 8 INCHES LONG. BACK LEGS 6 INCHES LONG. CANNOT BE SEPARATED.

Then I worried in case a person might mistake it was the dog’s legs that could not be separated, instead of him and me.

‘You can’t force that dog on anybody,’ said Miss Pinch, standing behind me, her long body folded like an umbrella.

‘He’s my dog,’

‘Yes, but whose are you? That we don’t know, and not everybody likes dogs.’

Miss Pinch was a direct descendent of the Reverend Dark. There were two Darks – the one who lived here, that was the Reverend, and the one who would rather be dead than live here, that was his father. Here you meet the first one, and the second one will come along in a minute.

Reverend Dark was the most famous person ever to come out of Salts. In 1859, a hundred years before I was born, Charles Darwin published his Origin of Species, and came to Salts to visit Dark. It was a long story, and like most of the stories in the world, never finished. There was an ending – there always is – but the story went on past the ending – it always does.

I suppose the story starts in 1814, when the Northern Lighthouse Board was given authority by an Act of Parliament to ‘erect and maintain such additional lighthouses upon such parts of the coast and islands of Scotland as they shall deem necessary’.

At the north-western tip of the Scottish mainland is a wild, empty place, called in Gaelic Am Parbh – the Turning Point. What it turns towards, or away from, is unclear, or perhaps it is many things, including a man’s destiny.

The Pentland Firth meets the Minch, and the Isle of Lewis can be seen to the west, the Orkneys to the east, but northwards there is only the Atlantic Ocean. I say only, but what does that mean? Many things, including a man’s destiny.

The story begins now – or perhaps it begins in 1802 when a terrible shipwreck lobbed men like shuttlecocks into the sea. For a while, they floated cork up, their heads just visible above the water line, but soon they sank bloated like cork, their rich cargo as useless to life as their prayers.

The sun came up the next day and shone on the wreck of the ship.

England was a maritime nation, and powerful business interests in London, Liverpool and Bristol demanded that a lighthouse be built here. But the cost and the scale were enormous. To protect the Turning Point, a light needed to be built at Cape Wrath.

Cape Wrath. Position on the nautical chart, 58° 37.5° N, 5°W.

Look at it – the headland is 368 feet high, wild, grand, impossible. Home to gulls and dreams.

There was a man called Josiah Dark – here he is – a Bristol merchant of money and fame. Dark was a small, active, peppery man, who had never visited Salts in his life, and on the day that he did he vowed never to return. He preferred the coffee-houses and conversation of easy, wealthy Bristol. But Salts was the place that would provide the food and the fuel for the lighthousekeeper and his family, and Salts would have to provide the labour to build it.

So with much complaining and more reluctance, Dark bedded for a week at the only inn, The Razorbill.

It was an uncomfortable place; the wind screeched at the windows, a hammock was half the price of a bed, and a bed was twice the price of a good night’s sleep. The food was mountain mutton that tasted like fencing, or hen tough as a carpet, that came flying in, all a-squawk behind the cook, who smartly broke its neck.

Every morning Josiah drank his beer, for they had no coffee in this wild place, and then he wrapped himself tight as a secret, and went up onto Cape Wrath.

Kittiwakes, guillemots, fulmars and puffins covered the headland, and the Clo Mor cliffs beyond. He thought of his ship, the proud vessel sinking under the black sea, and he remembered again that he had no heir. He and his wife had produced no children and the doctors regretted they never would. But he longed for a son, as he had once longed to be rich. Why was money worth everything when you had none of it, and nothing when you had too much?

So, the story begins in 1802, or does it really begin in 1789, when a young man, as fiery as he was small, smuggled muskets across the Bristol Channel to Lundy Island, where supporters of the Revolution in France could collect them.

He had believed in it all, somewhere he did still, but his idealism had made him rich, which was not what he intended. He had intended to escape to France with his mistress and live in the new free republic. They would be rich because everyone in France was going to be rich.

When the slaughtering started, he was sickened. He was not timid of war, but the tall talk and the high hearts had not been for this, this roaring sea of blood.

To escape his own feelings, he joined a ship bound for the West Indies and returned with a 10% share in the treasure. After that, everything he did increased his wealth.

Now he had the best house in Bristol and a lovely wife and no children.

As he stood still as a stone pillar, an immense black gull landed on his shoulder, its feet gripping his wool coat. The man dared not move. He thought, wildly, that the bird would carry him off like the legend of the eagle and child. Suddenly, the bird spread its huge wings and flew straight out over the sea, its feet pointed behind it.

When the man got to the inn, he was very quiet at his dinner, so much so that the wife of the establishment began to question him. He told her about the bird, and she said to him, ‘The bird is an omen. You must build your lighthouse here as other men would build a church.’

But first there was the Act of Parliament to be got, then his wife died, then he took sail for two years to repair his heart, then he met a young woman and loved her, and so much time passed that it was twenty-six years before the stones were laid and done.

The lighthouse was completed in 1828, the same year as Josiah Dark’s second wife gave birth to their first child.

Well, to tell you the truth, it was the same day.

The white tower of hand-dressed stone and granite was 66 feet tall, and 523 feet above the sea at Cape Wrath. It had cost £14,000.

‘To my son!’ said Josiah Dark, as the light was lit for the first time, and at that moment Mrs Dark, down in Bristol, felt her waters break, and out rushed a blue boy with eyes as black as a gull. They called him Babel, after the first tower that ever was, though some said it was a strange name for a child.

The Pews have been lighthousekeepers at Cape Wrath since the day of the birth. The job was passed down generation to generation, though the present Mr Pew has the look of being there forever. He is as old as a unicorn, and people are frightened of him because he isn’t like them. Like and like go together. Likeness is liking, whatever they say about opposites.

But some people are different, that’s all.

I look like my dog. I have a pointy nose and curly hair. My front legs – that is, my arms, are shorter than my back legs – that is, my legs, which makes a symmetry with my dog, who is just the same, but the other way round.

His name’s DogJim.

I put up a photo of him next to mine on the notice board, and I hid behind a bush while they all came by and read our particulars. They were all sorry, but they all shook their heads and said, ‘Well, what could we do with her?’

It seemed that nobody could think of a use for me, and when I went back to the notice board to add something encouraging, I found I couldn’t think of a use for myself.

Feeling dejected, I took the dog and went walking, walking, walking along the cliff headland towards the lighthouse.

Miss Pinch was a great one for geography – even though she had never left Salts in her whole life. The way she described the world, you wouldn’t want to visit it anyway. I recited to myself what she had taught us about the Atlantic Ocean…

The Atlantic is a dangerous and unpredictable ocean. It is the second largest ocean in the world, extending in an S shape from the Arctic to the Antarctic regions, bounded by North and South America in the West, and Europe and Africa in the East.

The North Atlantic is divided from the South Atlantic by the equatorial counter-current. At the Grand Bank off Newfoundland, heavy fogs form where the warm Gulf Stream meets the cold Labrador Current. In the North Western Ocean, icebergs are a threat from May to December.

Dangerous. Unpredictable. Threat.

The world according to Miss Pinch.

But, on the coasts and outcrops of this treacherous ocean, a string of lights was built over 300 years.

Look at this one. Made of granite, as hard and unchanging as the sea is fluid and volatile. The sea moves constantly, the lighthouse, never. There is no sway, no rocking, none of the motion of ships and ocean.

Pew was staring out of the rain-battered glass; a silent taciturn clamp of a man.

Some days later, as we were eating breakfast in Railings Row – me, toast without butter, Miss Pinch, kippers and tea – Miss Pinch told me to wash and dress quickly and be ready with all my things.

‘Am I going home?’

‘Of course not – you have no home.’

‘But I’m not staying here?’

‘No. My house is not suitable for children.’

You had to respect Miss Pinch – she never lied.

‘Then what is going to happen to me?’

‘Mr Pew has put in a proposal. He will apprentice you to lighthousekeeping.’

‘What will I have to do?’

‘I have no idea.’

‘If I don’t like it, can I come back?’

‘No.’

‘Can I take DogJim?’

‘Yes.’

She hated saying yes. She was of those people for whom yes is always an admission of guilt or failure. No was power.

A few hours later, I was standing on the windblown jetty, waiting for Pew to collect me in his patched and tarred mackerel boat. I had never been inside the lighthouse before, and I had only seen Pew when he stumped up the path to collect his supplies. The town didn’t have much to do with the lighthouse any more. Salts was no longer a seaman’s port, with ships and sailors docking for fire and food and company. Salts had become a hollow town, its life scraped out. It had its rituals and its customs and its past, but nothing left in it was alive. Years ago, Charles Darwin had called it Fossil-Town, but for different reasons. Fossil it was, salted and preserved by the sea that had destroyed it too.

Pew came near in his boat. His shapeless hat was pulled over his face. His mouth was a slot of teeth. His hands were bare and purple. Nothing else could be seen. He was the rough shape of human.

DogJim growled. Pew grabbed him by the scruff and threw him into the boat, then he motioned for me to throw in my bag and follow.

The little outboard motor bounced us over the green waves. Behind me, smaller and smaller, was my tipped-up house that had flung us out, my mother and I, perhaps because we were never wanted there. I couldn’t go back. There was only forward, northwards into the sea. To the lighthouse.

Pew and I climbed slowly up the spiral stairs to our quarters below the Light. Nothing about the lighthouse had been changed since the day it was built. There were candleholders in every room, and the Bibles put there by Josiah Dark. I was given a tiny room with a tiny window, and a bed the size of a drawer. As I was not much longer than my socks, this didn’t matter. DogJim would have to sleep where he could.

Above me was the kitchen where Pew cooked sausages on an open cast-iron stove. Above the kitchen was the light itself, a great glass eye with a Cyclops stare.

Our business was light, but we lived in darkness. The light had to be kept going, but there was no need to illuminate the rest. Darkness came with everything. It was standard. My clothes were trimmed with dark. When I put on a sou’wester, the brim left a dark shadow over my face. When I stood to bathe in the little galvanised cubicle Pew had rigged for me, I soaped my body in darkness. Put your hand in a drawer, and it was darkness you felt first, as you fumbled for a spoon. Go to the cupboards to find the tea caddy of Full Strength Samson, and the hole was as black as the tea itself.

The darkness had to be brushed away or parted before we could sit down. Darkness squatted on the chairs and hung like a curtain across the stairway. Sometimes it took on the shapes of the things we wanted: a pan, a bed, a book. Sometimes I saw my mother, dark and silent, falling towards me.

Darkness was a presence. I learned to see in it, I learned to see through it, and I learned to see the darkness of my own.

Pew did not speak. I didn’t know if he was kind or unkind, or what he intended to do with me. He had lived alone all his life.

That first night, Pew cooked the sausages in darkness. No, Pew cooked the sausages with darkness. It was the kind of dark you can taste. That’s what we ate: sausages and darkness.

I was cold and tired and my neck ached. I wanted to sleep and sleep and never wake up. I had lost the few things I knew, and what was here belonged to somebody else. Perhaps that would have been all right if what was inside me was my own, but there was no place to anchor.

There were two Atlantics; one outside the lighthouse, and one inside me.

The one inside me had no string of guiding lights.

A beginning, a middle and an end is the proper way to tell a story. But I have difficulty with that method. (#ulink_00f22af8-f8ac-50d0-aba8-3d788610e896)

Already I could choose the year of my birth – 1959. Or I could choose the year of the lighthouse at Cape Wrath, and the birth of Babel Dark – 1828. Then there was the year Josiah Dark first visited Salts – 1802. Or the year Josiah Dark shipped firearms to Lundy Island – 1789.

And what about the year I went to live in the lighthouse – 1969, also the year that Apollo landed on the moon?

I have a lot of sympathy with that date because it felt like my own moon landing; this unknown barren rock that shines at night.

There’s a man on the moon. There’s a baby on earth. Every baby plants a flag here for the first time.

So there’s my flag – 1959, the day gravity sucked me out of the mother-ship. My mother had been in labour for eight hours, legs apart in the air, like she was skiing through time. I had been drifting through the unmarked months, turning slowly in my weightless world. It was the light that woke me; light very different to the soft silver and night-red I knew. The light called me out – I remember it as a cry, though you will say that was mine, and perhaps it was, because a baby knows no separation between itself and life. The light was life. And what light is to plants and rivers and animals and seasons and the turning earth, the light was to me

When we buried my mother, some of the light went out of me, and it seemed proper that I should go and live in a place where all the light shone outwards and none of it was there for us. Pew was blind, so it didn’t matter to him. I was lost, so it didn’t matter to me.

Where to begin? Difficult at the best of times, harder when you have to begin again.

Close your eyes and pick another date: 1 February 1811.

This was the day when a young engineer called Robert Stevenson completed work on the lighthouse at Bell Rock. This was more than the start of a lighthouse; it was the beginning of a dynasty. For ‘lighthouse’ read ‘Stevenson’. They built scores of them until 1934 and the whole family was involved, brothers, sons, nephews, cousins. When one retired, another was immediately appointed. They were the Borgias of lighthousekeeping.

When Josiah Dark went to Salts in 1802, he had a dream but no one to build it. Stevenson was still an apprentice – lobbying, passionate, but without any power and with no record of success. He started out on Bell Rock as an assistant, and gradually took over the project that was hailed as one of the ‘modern wonders of the world’. After that, everybody wanted him to build their lighthouses, even where there was no sea. He became fashionable and famous. It helps.

Josiah Dark had found his man. Robert Stevenson would build Cape Wrath.

There are twists and turns in any life, and though all of the Stevensons should have built lighthouses, one escaped, and that was the one who was born at the moment Josiah Dark’s son, Babel, made a strange reverse pilgrimage and became Minister of Salts.

1850 – Babel Dark arrives in Salts for the first time.

1850 – Robert Louis Stevenson is born into a family of prosperous civil engineers – so say the innocent annotated biographical details – and goes on to write Treasure Island, Kidnapped, The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.

The Stevensons and the Darks were almost related, in fact they were related, not through blood but through the restless longing that marks some individuals from others. And they were related because of a building. Robert Louis came here, as he came to all his family lighthouses. He once said, ‘Whenever I smell salt water, I know I am not far from one of the works of my ancestors.’

In 1886, when Robert Louis Stevenson came to Salts and Cape Wrath, he met Babel Dark, just before his death, and some say it was Dark, and the rumour that hung about him, that led Stevenson to brood on the story of Jekyll and Hyde.

‘What was he like, Pew?’

‘Who, child?’

‘Babel Dark.’

Pew sucked on his pipe. For Pew, anything to do with thinking had first to be sucked in through his pipe. He sucked in words, the way other people blow out bubbles.

‘He was a pillar of the community.’

‘What does that mean?’

‘You know the Bible story of Samson.’

‘No I don’t.’

‘Then you’ve had no right education.’

‘Why can’t you just tell me the story without starting with another story?’

‘Because there’s no story that’s the start of itself, any more than a child comes into the world without parents.’

‘I had no father.’

‘You’ve no mother now neither.’

I started to cry and Pew heard me and was sorry for what he had said, because he touched my face and felt the tears.

‘That’s another story yet,’ he said, ‘and if you tell yourself like a story, it doesn’t seem so bad.’

‘Tell me a story and I won’t be lonely. Tell me about Babel Dark.’

‘It starts with Samson,’ said Pew, who wouldn’t be put off, ‘because Samson was the strongest man in the world and a woman brought him down, then when he was beaten and blinded and shorn like a ram he stood between two pillars and used the last of his strength to bring them crashing down. You could say that Samson was two pillars of the community, because anyone who sets himself up is always brought down, and that’s what happened to Dark.

‘The story starts in Bristol in 1848 when Babel Dark was twenty years old and as rich and fine as any gentleman of the town. He was a ladies’ man, for all that he was studying Theology at Cambridge, and everyone said he would marry an heiress from the Colonies and take up his father’s business in ships and trade.

‘It was set fair to be so.

‘There was a pretty girl lived in Bristol and all the town knew her for her red hair and green eyes. Her father was a shopkeeper, and Babel Dark used to visit the shop to buy buttons and braids and soft gloves and neckties, because I have said, haven’t I, that he was a bit of a dandy?

‘One day – a day like this, yes just like this, with the sun shining, and the town bustling, and the air itself like a good drink – Babel walked into Molly’s shop, and spent ten minutes examining cloth for riding breeches, while he watched out of the corner of his eye until she had finished serving one of the Jessop girls with a pair of gloves.

‘As soon as the shop was empty, Babel swung over to the counter and asked for enough braid to rig a ship, and when he had bought all of it, he pushed it back towards Molly, kissed her direct on the lips, and asked her to a dance.

‘She was a shy girl, and Babel was certainly the handsomest and the richest young man that paraded the waterfront. At first she said no, and then she said yes, and then she said no again, and when all the yeas and nays had been bagged and counted, it was unanimous by a short margin, that she was going to the dance.

‘His father didn’t disapprove, because old Josiah was no snob, and his own first love had been a jetty girl, back in the days of the French Revolution.’

‘What’s a jetty girl?’

‘She helps with the nets and the catch and luggage and travellers and so on, and in the winter she scrapes the boats clean of barnacles and marks the splinters for tarring by the men. Well, as I was saying, there were no obstacles to the pair meeting when they liked, and the thing continued, and then, they say, and this is all rumour and never proved, but they say that Molly found herself having a child, and no legal wedded father.’

‘Like me?’

‘Yes, the same.’

‘It must have been Babel Dark.’

‘That’s what they all said, and Molly too, but Dark said not. Said he wouldn’t and couldn’t have done such a thing. Her family asked him to marry her, and even Josiah took him aside and told him not to be a panicky fool, but to own up and marry the girl. Josiah was all for buying them a smart house and setting up his son straight away, but Dark refused it all.

‘He went back to Cambridge that September, and when he came home at Christmas time, he announced his intention of going into the Church. He was dressed all in grey, and there was no sign of his bright waistcoats and red top boots. The only thing he still wore from his former days was a ruby and emerald pin that he had bought very expensive when he first took up with Molly O’Rourke. He’d given her one just like it for her dress.

‘His father was upset and didn’t believe for a minute that he had got to the bottom of the story, but he tried to make the best of it, and even invited the Bishop to dinner, to try and get a good appointment for his son.

‘Dark would have none of it. He was going to Salts.

“Salts?” said his father. “That God-forsaken sea-claimed rock?’

‘But Babel thought of the rock as his beginning, and it was true that as a child his favourite pastime when it rained was to turn over the book of drawings that Robert Stevenson had made, of the foundations, the column, the keeper’s quarters, and especially the prismatic diagrams of the light itself. His father had never taken him there, and now he regretted it. One week at The Razorbill would surely have been enough for life.

‘Well, it was a wet and wild and woebegone January when Babel Dark loaded two trunks onto a clipper bound seaward from Bristol and out past Cape Wrath.

‘There were plenty of good folks to see him go, but Molly O’Rourke wasn’t amongst them because she had gone to Bath to give birth to her child.

‘The sea smashed at the ship like a warning, but she made good headway, and began to blur from view, as we watched Babel Dark, standing wrapped in black, looking at his past as he sailed away from it forever.’

‘Did he live in Salts all his life?’

‘You could say yes, and you could say no.’

‘Could you?’

‘You could, depending on what story you were telling.’

‘Tell me!’

‘I’ll tell you this – what do you think they found in his drawer, after he was dead?’

‘Tell me!’

‘Two emerald and ruby pins. Not one – two.’

‘How did he get Molly O’Rourke’s pin?’

‘Nobody knows.’

‘Babel Dark killed her!’

‘That was the rumour, yes, and more.’

‘What more?’

Pew leaned close, the brim of his sou’wester touching mine. I felt his words on my face.

‘That Dark never stopped seeing her. That he married her in secret and visited her hidden and apart under another name for both of them. That one day, when their secret would have been told, he killed her and others besides.’

‘But why didn’t he marry her?’

‘Nobody knows. There are stories, oh yes, but nobody knows. Now off to bed while I tend the light.’

Pew always said ‘tend the light’, as though it were his child he was settling for the night. I watched him moving round the brass instruments, knowing everything by touch, and listening to the clicks on the dials to tell him the character of the light.

‘Pew?’

‘Go to bed.’

‘What do you think happened to the baby?’

‘Who knows? It was a child born of chance.’

‘Like me?’

‘Yes, like you.’

I went quietly to bed, DogJim at my feet because there was nowhere else for him. I curled up to keep warm, my knees under my chin, and hands holding my toes. I was back in the womb. Back in the safe space before the questions start. I thought about Babel Dark, and about my own father, as red as a herring. That’s all I know about him – he had red hair like me.

A child born of chance might imagine that Chance was its father, in the way that gods fathered children, and then abandoned them, without a backward glance, but with one small gift. I wondered if a gift had been left for me. I had no idea where to look, or what I was looking for, but I know now that all the important journeys start that way.

KNOWN POINT IN THE DARKNESS (#ulink_9348d88c-4e64-58ea-a0e7-a6ec3884d6aa)

As an apprentice to lighthousekeeping my duties were as follows: (#ulink_1ae5da92-3597-5291-9a9c-70b4113de29c)

1) Brew a pot of Full Strength Samson and take it to Pew.

2) 8 am. Take DogJim for a walk.

3) 9 am. Cook bacon.

4) 10 am. Sluice the stairs.

5) 11 am. More tea.

6) Noon. Polish the instruments.

7) 1 pm. Chops and tomato sauce.

8) 2 pm. Lesson – History of Lighthouses.

9) 3 pm. Wash our socks etc.

10) 4 pm. More tea.

11) 5 pm. Walk the dog and collect supplies.

12) 6 pm. Pew cooks supper.

13) 7 pm. Pew sets the light. I watch.

14) 8 pm. Pew tells me a story.

15) 9 pm. Pew tends the light. Bed.

Numbers 3, 6, 7, 8 and 14 were the best times of the day. I still get homesick when I smell bacon and Brasso.

Pew told me about Salts years ago, when wreckers lured ships onto the rocks to steal the cargo. The weary seamen were desperate for any light, but if the light is a lie, everything is lost. The new lighthouses were built to prevent this confusion of light. Some of them lit great fires on their platforms, and burned out to sea like a dropped star. Others had only twenty-five candles, standing in the domed glass like a saint’s shrine, but for the first time, the lighthouses were mapped. Safety and danger were charted. Unroll the paper, set the compass, and if your course is straight, the lights will be there. What flickers elsewhere is a trap or a lure.

The lighthouse is a known point in the darkness.

‘Imagine it,’ said Pew, ‘the tempest buffeting you starboard, the rocks threatening your lees, and what saves you is a single light. The harbour light, or the warning light, it doesn’t matter which; you sail to safety. Day comes and you’re alive.’

‘Will I learn to set the light?’

‘Aye, and tend the light too.’

‘I hear you talking to yourself.’

‘I’m not talking to myself, child, I’m about my work.’ Pew straightened up and looked at me seriously. His eyes were milky blue like a kitten’s. No one knew whether or not he had always been blind, but he had spent his whole life in the lighthouse or on the mackerel boat, and his hands were his eyes.

‘A long time ago, in 1802 or 1892, you name your date, there’s most sailors could not read nor write. Their officers read the navy charts, but the sailors had their own way. When they came past Tarbert Ness or Cape Wrath or Bell Rock, they never thought of such places as positions on the map, they knew them as stories. Every lighthouse has a story to it – more than one, and if you sail from here to America, there’ll not be a light you pass where the keeper didn’t have a story for the seamen.

In those days the seamen came ashore as often as they could, and when they put up at the inn, and they had eaten their chops and lit their pipes and passed the rum, they wanted a story, and it was always the lighthousekeeper who told it, while his Second or his wife stayed with the light. These stories went from man to man, generation to generation, hooped the sea-bound world and sailed back again, different decked maybe, but the same story. And when the lightkeeper had told his story, the sailors would tell their own, from other lights. A good keeper was one who knew more stories than the sailors. Sometimes there’d be a competition, and a salty dog would shout out “Lundy” or “Calf of Man” and you’d have to answer, “The Flying Dutchman” or “Twenty Bars of Gold“.’

Pew was serious and silent, his eyes like a faraway ship.

‘I can teach you – yes, anybody – what the instruments are for, and the light will flash once every four seconds as it always does, but I must teach you how to keep the light. Do you know what that means?’

I didn’t.

‘The stories. That’s what you must learn. The ones I know and the ones I don’t know.’

‘How can I learn the ones you don’t know?’

‘Tell them yourself.’

Then Pew began to say of all the sailors riding the waves who had sunk up to their necks in death and found one last air pocket, reciting the story like a prayer.

‘There was a man close by here, lashed himself to a spar as his ship went down, and for seven days and seven nights he was on the sea, and what kept him alive while others drowned was telling himself stories like a madman, so that as one ended another began. On the seventh day he had told all the stories he knew and that was when he began to tell himself as if he were a story, from his earliest beginnings to his green and deep misfortune. The story he told was of a man lost and found, not once, but many times, as he choked his way out of the waves. And when night fell, he saw the Cape Wrath light, only lit a week it was, but it was, and he knew that if he became the story of the light, he might be saved. With his last strength he began to paddle towards it, arms on either side of the spar, and in his mind the light became a shining rope, pulling him in. He took hold of it, tied it round his waist, and at that moment, the keeper saw him, and ran for the rescue boat.

‘Later, putting up at The Razorbill, and recovering, he told anyone who wanted to listen what he had told himself on those sea-soaked days and nights. Others joined in, and it was soon discovered that every light had a story – no, every light was a story, and the flashes themselves were the stories going out over the waves, as markers and guides and comfort and warning.’

Cliff-perched, wind-cleft, (#ulink_8fc59c13-536e-5d28-8f62-990a755b8a56)

the church seated 250, and was almost full at 243 souls, the entire population of Salts.

On 2 February 1850, Babel Dark preached his first sermon.

His text was this: ‘Remember the rock whence ye are hewn, and the pit whence ye are digged.’

The innkeeper at The Razorbill was so struck by this sermon and its memorable text that he changed the name of his establishment. From that day forth, he was no longer landlord of The Razorbill, but keeper of The Rock and Pit. Sailors, being what they are, still called it by its former name for a good sixty years or more, but The Rock and Pit it was, and is still, with much the same low-beamed, inward-turned, net-hung, salt-dashed, seaweed feel of forsakenness that it always had.

Babel Dark used his private fortune to build himself a fine house and a walled garden and to equip himself comfortably there. He was soon seen in earnest Biblical discussion with the one lady of good blood in the place – a cousin of the Duke of Argyll, a Campbell in exile, out of poverty and some other secret. She was no beauty, but she read German fluently and knew something of Greek.

They were married in 1851, the year of the Great Exhibition, and Dark took his new wife to London for her honeymoon, and thereafter he never took her anywhere again, not even to Edinburgh. Wherever he went, riding alone on a black mare, no one was told, and no one followed.

There were disturbances at night, sometimes, and the Manse windows all flamed up, and shouts and hurlings of furniture or heavy objects, but question Dark, as few did, and he would say it was his soul in peril, and he fought for it, as every man must.

His wife said nothing, and if her husband was gone for days at a time, or seen wandering in his black clothes over the high rocks, then let him be, for he was a Man of God, and he accepted no judge but God himself.

One day, Dark saddled his horse and disappeared.

He was gone a month, and when he returned, he was softer, easier, but with plain sadness on his face.

After that, the month-long absences happened twice a year, but no one knew where he went, until a Bristol man put up at The Razorbill, that is to say The Rock and Pit.

He was a close-guarded man, eyes as near together as to be always spying on one another, and a way of tapping his finger and thumb, very rapid, when he spoke. His name was Price.

One Sunday, after Price had been to church, he was sitting over the fire with a puzzlement on his face, and it was finally got out of him that if he hadn’t seen Babel Dark before and just recently, then the man had the devil’s imprint down in Bristol.

Price claimed that he had seen Dark, wearing very different clothes, visiting a house in the Clifton area outside Bristol. He took note of him for his height – tall, and his bearing – very haughty. He had never seen him with anyone, always alone, but he would swear on his tattoo that this was the same one.

‘He’s a smuggler,’ said one of us.

‘He’s got a mistress,’ said another.

‘It’s none of our business,’ said a third. ‘He does his duties here and he pays his bills and handsomely. What else he does is between him and God.’

The rest of us were not so sure, but as nobody had the money to follow him, none of us could know whether Price’s story was true or not. But Price promised to keep a look out, and to send word, if he ever saw Dark or his like again.

‘And did he?’

‘Oh yes, indeed he did, but that didn’t help us to know what Dark was about, or why.’

‘You weren’t there then. You weren’t born.’

‘There’s always been a Pew in the lighthouse at Cape Wrath.’

‘But not the same Pew.’

Pew said nothing. He put on his radio headphones, and motioned me to look out to sea. ‘The McCloud’s out there,’ he said.

I got the binoculars and trained them on a handsome cargo ship, white on the straight line of the horizon. ‘She’s the most haunted vessel you’ll ever see.’

‘What haunts her?’

‘The past,’ said Pew. ‘There was a brig called the McCloud built two hundred years ago, and that was as wicked a ship as sailed. When the King’s navy scuttled her, her Captain swore an oath that he and his ship would some day return. Nothing happened until they built the new McCloud, and on the day they launched her, everyone on the dock saw the broken sails and ruined keel of the old McCloud rise up in the body of the ship. There’s a ship within a ship and that’s fact.’

‘It’s not a fact.’

‘It’s as true as day.’

I looked at the McCloud, fast, turbined, sleek, computer-controlled. How could she carry in her body the trace-winds of the past?

‘Like a Russian doll, she is,’ said Pew, ‘one ship inside another, and on a stormy night you can see the old McCloud hanging like a gauze on the upper deck.’

‘Have you seen her?’

‘Sailed in her and seen her,’ said Pew.

‘When did you board the new McCloud? Was she in dry dock at Glasgow?’

‘I never said anything about the new McCloud,’ said Pew.

‘Pew, you are not two hundred years old.’

‘And that’s a fact,’ said Pew, blinking like a kitten. ‘Oh yes, a fact.’

‘Miss Pinch says I shouldn’t listen to your stories.’

‘She doesn’t have the gift, that’s why.’

‘What gift?’

‘The gift of Second Sight, given to me on the day I went blind.’

‘What day was that?’

‘Long before you were born, though I saw you coming by sea.’

‘Did you know it would be me, me myself as I am, me?’

Pew laughed. ‘As sure as I knew Babel Dark – or someone very like me knew someone very like him.’

I was quiet. Pew could hear me thinking. He touched my head, in that strange, light way of his, like a cobweb.

‘It’s the gift. If one thing is taken away, another will be found.’

‘Miss Pinch doesn’t say that, Miss Pinch says Life is a Steady Darkening Towards Night. She’s embroidered it above her oven.’

‘Well, she never was the optimistic kind.’

‘What can you see with your Second Sight?’

‘The past and the future. Only the present is dark.’

‘But that’s where we live.’

‘Not Pew, child. A wave breaks, another follows.’

‘Where’s the present?’

‘For you, child, all around, like the sea. For me, the sea is never still, she’s always changing. I’ve never lived on land and I can’t say what’s this or that. I can only say what’s ebbing and what’s becoming.’

‘What’s ebbing?’

‘My life.’

‘What’s becoming?’

‘Your life. You’ll be the keeper after me.’

Tell me a story, Pew. (#ulink_ef90dff9-d7ef-5e8b-aca5-78ea20c128b4)

What kind of story, child?

A story with a happy ending.

There’s no such thing in all the world.

As a happy ending?

As an ending.

To make an end of it Dark had decided to marry. (#ulink_360b8be1-4749-54cf-9cfa-49df61a576dd)

His new wife was gentle, well read, unassuming, and in love with him. He was not in the least in love with her, but that, he felt, was an advantage. They would both work hard in a parish that fed on oatmeal and haddock. He would hew his path, and if his hands bled, so much the better.

They were married without ceremony in the church at Salts, and Dark immediately fell ill. The honeymoon had to be postponed, but his new wife, all tenderness and care, made him breakfast every day with her own hands, though she had a maid to do it for her.

He grew to dread the hesitant tread on the stairs to his room that overlooked the sea. She carried the tray so slowly that by the time she reached his room the tea had gone cold, and every day she apologised, and every day he told her to think nothing of it, and swallowed a sip or two of the pale liquid. She was trying to be economical with the tea leaves.

That morning, he lay in bed and heard the clinking of the cups on the tray, as she came slowly towards him. It would be porridge, he thought, heavy as a mistake, and muffins studded with raisins that accused him as he ate them. The new cook – her appointment – baked bread plain, and disapproved of ‘fanciness’ as she called it, though what was fancy about a raisin, he did not know.

He would have preferred coffee, but coffee was four times the price of tea.

‘We are not poor,’ he had said to his wife, who reminded him that they could give the money to a better cause than breakfast coffee.

Could they? He was not so sure, and whenever he saw a deserving lady with a new bonnet, it seemed to smell, to him, steamingly aromatic.

The door opened, she smiled – not at him, at the tray – because she was concentrating. He thought, irritably, that a tightrope walker he had seen on the docks would have carried this tray with more grace and skill, even on a line strung between two masts.

She set it down, with her usual air of achievement and sacrifice.

‘I hope you will enjoy it, Babel,’ she said, as she always did.

He smiled and took the cold tea.

Always. They had not been married long enough for there to be an always.

They were new, virgin, fresh, without habits. Why did he feel that he had lain in this bed forever, slowly filling up with cold tea?

Till death us do part.

He shivered.

‘You are cold, Babel,’ she said.

‘No, only the tea.’

She looked hurt, rebuked.

‘I make the tea before I toast the muffins.’

‘Perhaps you should do it afterwards.’

‘Then the muffins would be cold.’

‘They are cold.’

She picked up the tray. ‘I will make us a second breakfast.’

It was as cold as the first. He did not speak of it again.

He had no reason to hate his wife. She had no faults and no imagination. She never complained, and she was never pleased. She never asked for anything, and she never gave anything – except to the poor. She was modest, mild-mannered, obedient, and careful. She was as dull as a day at sea with no wind.

In his becalmed life, Dark began to taunt his wife, not out of cruelty at first, but to test her, perhaps to find her. He wanted her secrets and her dreams. He was not a man of good mornings and good nights.

When they went out riding, he would sometimes thrash her pony with a clean sing of his whip, and the beast would gallop off, his wife grabbing the mane because she was an uncertain horsewoman. He liked the pure fear in her face – a feeling at last, he thought.

He took her sailing on days when Pew would have been a brave man to take out his rescue boat. Dark liked to watch her, drenched and vomiting, begging him to steer home and when they got the boat back, half capsized with water, he’d declare it a fine day’s sailing, and make her walk to the house holding his hand.

In the bedroom, he turned her face down, one hand against her neck, the other bringing himself stiff, then he knocked himself into her in one swift move, like a wooden peg into the tap-hole of a barrel. His fingermarks were on her neck when he had finished. He never kissed her.

When he wanted her, which was never as herself, but sometimes, because he was a young man, he trod slowly up the stairs to her room, imagining he was carrying a tray of greasy muffins and a pot of cold tea. He opened the door, smiling, but not at her.

When he had finished with her, he sat across her, keeping her there, the way he would keep his dog down when he went out shooting. In the chilly bedroom – she never lit a fire – he let his semen go cold on her before he let her get up.

Then he went and sat in his study, legs flung up on the desk, thinking of nothing. He had trained himself to think of absolutely nothing.

On Wednesday afternoons, they visited the poor. He loathed it; the low houses, mended furniture, women patching clothes and nets with the same needle and the same coarse twine. The houses smelled of herrings and smoke. He did not understand how any person could live in such wretchedness. He would rather have ended his life.

His wife sat sympathetically listening to stories of no wood, no eggs, sore gums, dead sheep, sick children, and always she turned to him as he stood brooding out of the window, and said, ‘The pastor will offer you a word of comfort.’

He would not turn round. He murmured something about Jesus’s love and left a shilling on the table.

‘You were hard, Babel,’ his wife said as they walked away.

‘Shall I be a hypocrite, like you?’

That was the first time he hit her. Not once, but again and again and again, shouting, ‘You stupid slut, you stupid slut, you stupid slut.’ Then he left her swollen and bleeding on the cliff path and ran back to the Manse and into the scullery, where he knocked the lid off the copper and plunged both his hands up to their elbows in the boiling water.

He held them there, crying out, as the skin reddened and began to peel, the with the skin white and bubbled on his fingers and palms, he went outside and began to chop wood until his wounds bled.

For several weeks, he avoided his wife. He wanted to say he was sorry, and he was sorry, but he knew he would do it again. Not today or tomorrow, but it would break out of him, how much he loathed her, how much he loathed himself.

In the evenings she read to him from the Bible. She liked reading the miracles, which surprised him in someone whose nature was as unmiraculous as a bucket. She was a plain vessel who could carry things; tea trays, babies, a basket of apples for the poor.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/jeanette-winterson/lighthousekeeping-39788745/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Jeanette Winterson

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: From one of Britain’s best-loved literary novelists comes a magical, lyrical tale of the young orphan Silver, taken in by the ancient lighthousekeeper Mr. Pew, who reveals to her a world of myth and mystery through the art of storytelling.Motherless and anchorless, Silver is taken in by the timeless Mr. Pew, keeper of the Cape Wrath lighthouse. Pew tells Silver ancient tales of longing and rootlessness, of the slippages that occur throughout every life. One life, Babel Dark’s, a nineteenth-century clergyman, opens like a map that Silver must follow, and the intertwining of myth and reality, of storytelling and experience, lead her through her own particular darkness.A story of mutability, talking birds and stolen books, of Darwin and Stevenson and of the Jekyll and Hyde in all of us, Lighthousekeeping is a way into the most secret recesses of our own hearts and minds. Jeanette Winterson is one of the most extraordinary and original writers of her generation, and this shows her at her lyrical best.