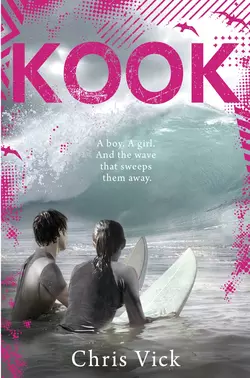

Kook

Kook

Chris Vick

A heart-pounding love story that grips like a riptide, and doesn’t let go…Fifteen-year old Sam has moved from the big city to the coast – stuck there with his mum and sister on the edge of nowhere.Then he meets beautiful but damaged surfer-girl Jade. Soon he’s in love with her, and with surfing itself. But Jade is driven by an obsession: finding and riding a legendary huge wave no one has ever ridden.As the weeks wear on, their relationship barrels forward with the force of a deep-water wave – into a storm, to danger … and to heartbreak.

Copyright (#ufac75bba-ed4a-58d2-bed8-05e500306047)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2016

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

1 London Bridge Street, London, SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins website address is: www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/)

Copyright © Chris Vick 2016

Cover photographs © Colin Anderson/Blend Images/Corbis (boy); Erik Isakson/Blend Images/Corbis (girl); Shutterstock.com (http://Shutterstock.com) (all other images).

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2016

Chris Vick asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of the work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Ebook Edition © MARCH 2016 ISBN: 9780008158330

Source ISBN 9780008158323

Version 2016-01-29

Dedication (#ufac75bba-ed4a-58d2-bed8-05e500306047)

For Sarah and Lamorna

Table of Contents

Cover (#u2a3b8096-d4a7-501b-ad5f-d70a16d45ea3)

Title Page (#u1b0e2820-6608-5941-8a82-a8fd50564377)

Copyright (#u889af600-0f01-50bc-ac69-c5d2b066e2f0)

Dedication (#ub8d37568-118d-5a56-a4ef-6f27fb440f2e)

Epigraph (#ubb13ecc2-8fac-5066-8751-8bb047201a97)

Chapter 1 (#u4f3e1ace-4673-5df7-ae76-64d5aec3f81a)

Chapter 2 (#u04da6a13-8cee-5f8d-8b3e-e33510fd3a62)

Chapter 3 (#u1c58560d-32bb-5d93-b1fd-cc008d61745b)

Chapter 4 (#u156d7ad6-971a-5b61-b7c7-810e232715b9)

Chapter 5 (#u8c7465f1-e3fb-5f88-a4dc-cdd081e87d93)

Chapter 6 (#u1ea31dcd-5b51-58dd-9482-46293c068941)

Chapter 7 (#u1578dd14-c406-5971-aad2-747627b34a43)

Chapter 8 (#u8ac2df4a-20e1-59dd-a1fe-3ad6c576f410)

Chapter 9 (#u77780e5d-ae51-5391-92d4-03a838de0231)

Chapter 10 (#u1f0d77cf-9522-5a14-8246-dc11eb4015df)

Chapter 11 (#ue8549827-bf23-5823-8f18-d1cbb05050c9)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 39 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 40 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 41 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 42 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 43 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 44 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 45 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 46 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 47 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 48 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 49 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 50 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 51 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Kook: (surfer slang): a learner, a wannabe.

(#ufac75bba-ed4a-58d2-bed8-05e500306047)

(#ufac75bba-ed4a-58d2-bed8-05e500306047)

JADE GOT ME in trouble from day one.

We moved back to Cornwall one Saturday, early last September. Mum, my kid sister Tegan, and me.

It was a sunny day, with a cool wind. The first day of autumn, or maybe the last of summer.

We drove through the village of Penford, and after a five-minute drive over the moor, bounced our way down a broken track.

When we got there, I saw why the rent was cheap. There were two cottages, storm-beaten old things, with moss on their roofs and rotten wood windows, nestled between the clifftops and the moor. There were stone walls to keep the sheep away, a few brush trees bent into weird shapes by the wind, and not much else.

Half a mile downhill, the land ended in a sharp line at the clifftop.

We were going to live in one cottage. Jade, her dad and their dog already lived in the other. They came over in the afternoon when Mum was arguing with the removal guy about why it wasn’t her fault the track had knackered the van’s suspension.

Jade’s dad introduced them both. Jade hung back and let him do the talking. He said about borrowing a cup of sugar any time and other neighbourly stuff. I didn’t pay any attention. I was working hard trying not to stare at Jade.

Her hair was long and black. Her eyes were sea blue-and-green, shining out of a honey brown face. Jade had a glow about her, something no old T-shirt and denim jacket could hide.

She took one look at me with those sea eyes and curled her lips into a half-smile. It put a hook in me.

“How old are you, Sam?” her dad said.

“Sorry, what?” I said.

“How old are you?”

“Fifteen.”

“Right. You’ll be going to Penwith High with Jade then. You can help each other with homework, hang out and stuff.” He was over keen. I think it was awkward for Jade as well as me. I found out later he’d checked me with one look and reckoned I’d be A Good Influence on Jade. Different from the type she normally hung out with.

We went into the kitchen to drink tea and eat a cake they’d brought with them, her dad – Bob – and Mum chatting away about Cornwall, me and Jade competing at who-can-say-the-least. She liked Tegan though. Jade gave her bits of cake to feed to the scruffy sheep dog.

When they stood to go, Bob said, “Jade was going to take Tess for a walk. You could go with her… Oh, daft, aren’t I? You’re unpacking. Another time.”

“That’s okay,” said Mum. “You go, Sam, but not too long. If it’s all right with Jade?”

“Okay.” Jade and her dog were out of the kitchen before I could say a word.

Jade made a line for the nearby hill, pelting straight up the path like she was on a mission.

“What’s the hurry?” I said, catching her up.

“I need to check something.” She had a Cornish accent. But soft; husky.

At the top we climbed up on to a large, flat rock and sat down. She pulled a pack of cigarettes out of her pocket and, using me as a wind shelter, lit one.

Beyond the moor was the sea, blue and white and shining. The light of it hit me so hard I had to screw up my eyes. I hadn’t seen the Cornish sea in years, not since I was four, after Dad died. I couldn’t even remember it much. I hadn’t expected that just looking at it would make my head spin. It was big as the sky.

“Great view,” I said.

“Yeah. Right. Hold this,” she said, passing me the cigarette. She pulled a tiny pair of binoculars from her denim jacket, fiddled with the focus and pointed them at the distant sea. Along the coast was a thin headland of cliff knifing into the Atlantic. Jade didn’t move an inch. She just stared through the binocs, reaching out a hand for the cigarette once in a while. The dog lay beside her, its black and white head on her lap.

Then, suddenly, she sat upright, tense, like she’d noticed something. All I could make out was a thin line of white water, rolling into the distant cliff.

“What you looking at?” I said.

“Signposts.”

“What?”

“That’s the spot’s name.” She sighed, and pocketed the binocs. “I can see the waves there, that’s why it’s called Signposts. Swell’s about three foot. Do you surf, Sam?”

“No.”

“Shame. I do.” She jumped off the rock, leaving me holding the smouldering fag butt. And I thought, Oh, right, see you then. But…

“Come on!” she shouted, running down the hill.

“Surfing?” I shouted. But she’d already gone too far to hear me.

(#ufac75bba-ed4a-58d2-bed8-05e500306047)

AS I RAN, I was thinking, Shit, this is already nothing like London.

The moors in the sun were nothing like the flats that filled up the sky in Westbourne Park. Running off to the beach was nothing like heading to the dog-turd littered park for a kickaround. And Jade was nothing like… any girl I’d ever met. She wasn’t just beautiful. There was something about her. Something raw and naked. Something you wanted to look at – had to look at – but felt you shouldn’t.

We went past our place and straight to their cottage. They’d built a wooden barn-garage right next to it. It was full of junk: an old washing machine, bikes, crates of books. I clocked the surfboards stacked against the wall, but she walked past them to a ladder leading up to an attic. I was going to follow her, but she said, “No, wait here.”

After a minute or two, she climbed back down, carrying a wetsuit and towel.

“What’s up there?” I asked. She didn’t answer. She stood by the surfboards, eyeing them up before choosing the middle one of the three – a blue beaten-up old thing about half a foot taller than she was, with a V shaped tail.

“Love this fish,” she said, stroking its edge. “Flies in anything.” She balanced the suit and towel over her shoulder and stuck the board under one arm. Then she took an old bike from where it leant against a fridge.

“You can borrow Dad’s bike,” she said.

“But I don’t surf.”

“You said. Come anyway. Don’t be a kook.”

“What’s a kook?”

“It’s what you are,” she said, getting on the bike.

“Do you want me to carry…” I started. But she was already out of the door, riding the bike with one hand, and holding the board under her arm with the other. The dog followed, jumping and wagging its tail.

“How d’you do that?” I said.

“Practice!” she shouted.

It was making me dizzy. One minute we’re eating cake, then we’re up a hill, then we’re off to the beach. And she was bossy. That annoyed me. But I was dead curious, and yeah, she was that pretty, you wouldn’t not follow her. I grabbed her dad’s bike and pedalled after her.

After ten minutes we took a path off the road and cycled down a stony trail, with the dog running behind us, stopping where the ruined towers and walls of an old tin mine hung to the cliff edge.

We dumped the bikes. Jade led us past a ‘DANGER – KEEP OUT’ sign by the mine and down a steep path that ended by a huge granite boulder, right on the cliff edge. She walked up to the large rock, and put the board on top of it, stretching, nudging it over the top with her fingertips. She left it there, balancing. Then, placing her body tight against the rock, and still with the towel and wetsuit over her shoulder, she moved around the rock, till she disappeared. A few seconds later the board disappeared too, pulled over the rock’s edge. The dog ran up the cliff and over the boulder.

It was like they’d just vanished.

I stepped up to the cliff edge and looked down. The sight of the sea hit me in the gut. It must have been a thirty-foot drop. She’d shimmied around the rock, casual as anything, along a ledge inches wide. If you slipped, you’d fall. If you were lucky, you’d grab a rock and hold on. Chances were, you’d go over. And die.

“Coming?” said her voice, from behind the rock, teasing me.

“Sure,” I said. I knew that without the drop I could do it easy, so why not now? I wasn’t going to bottle it in front of this girl.

I pushed my face against the cool stone and edged around the rock. The volume of life was turned up. I could hear every shuffle of my feet, every breath echoing around my head, every beat of my heart. I couldn’t see my feet; I just had to trust they were going in the right place.

It only took about ten seconds, but they were long ones.

When I came round, I was panting and she was smiling, with a raised eyebrow and half of her mouth curling, like she was amused.

The path – hidden from the other side of the rock – hugged the cliff, with sheer cliff on one side and a steep drop on the other. It was no more than two feet wide. A tricky climb down. But like with the bike and carrying the board, Jade made it look easy. I guessed she’d done it a hundred times before.

There was no beach when we reached the bottom, just a flat ledge of reef, rock pools and seaweed. Far out to sea, the wind was messing up the ocean, chasing white peaks across the bay. But here the water was still, dark glass. Somewhere between this secret cove and the open sea were two surfers, sat on their boards, still as statues.

“Tell anyone about this place and they’ll kill you,” said Jade, pointing at them and sounding like she wasn’t kidding. Surrounding herself with the towel, she started to change. She had a swimsuit on under her hoody. She must have changed into it when she was in the garage attic.

And there I was again. Staring. I don’t think I was dribbling, or had my mouth open or anything. But I might have been, the way she glared at me.

“Oh, sorry,” I said, and looked away. “There’s no waves.” It was flat calm, apart from a gentle lapping at the rock’s edge.

“Long wave period. Watch.”

After a couple of minutes, like a clockwork doll coming to life, one of the surfers flipped his board round and started paddling towards the shore. At first I couldn’t see why, but then, behind him, hard to see against the sea-glare, was a wall of water. It jacked up, rising out of the blue till it formed a feathering edge. The surfer angled his board, paddled a stroke or two, pushed up with his arms and swung his feet beneath him, landing on the board, and in one swoop was riding down and across the wave, gliding in a long line before weaving the board in a series of snake shapes. The wave broke perfectly, carrying the surfer one step ahead of the white mess behind him. Then the other surfer did the same thing on the wave behind. Their whoops echoed around the cliff.

And I got it. Even then, I got it.

It looked like freedom.

Jade appeared at my shoulder, in her wetsuit. “I’m gonna get some of that. Look after Tess,” she shouted. She ran to where the rock met the water’s edge and launched herself into the sea, landing on the board and paddling powerfully into the dark water.

As the sun sank in the sky, I sat down with the dog at my side and watched.

They made it look easy, carving up and down the faces of the waves, spinning their bodies and boards round like they were dancing on water.

So yeah, I got it. And this place was part of the buzz I was feeling, this secret cove and the girl and the surfing and the sun falling into the sea. They all added up to something good. Something not-London.

When another surfer arrived it felt wrong, like he’d invaded my own little bit of heaven. Which was crazy. I was the stranger there.

He was about my age, tall and big shouldered, with a lot of scruffy black hair, a scraggy would-be beard and big cow eyes. But there was something intense about those eyes. They were full alert, with a thousand-yard stare, like he was looking through me. He wasn’t smiling; his natural look was a sneer. He came over and stood closer to me than he needed to. He looked at Tess like he was puzzled. I think he recognised the dog.

“Your mate’s out there?” he said, pointing out to sea.

“No, I’m with this girl…” I said. He looked out to sea, frowning. “I don’t mean with…” I stumbled. “She just… brought me here.”

“Right. You a surfer?”

“No,” I said. He nodded, like I’d said the right answer, and left me alone.

*

Jade returned after an hour or more in the water. And I was thinking that was good, I needed to get back.

“Well, that was a score. Did you see me, Sam? Real fun waves,” she said, strutting up to me.

She’d been hard edged before; now she was grinning like an idiot and was super friendly, like she’d taken some happy drug.

“Tempted?” she asked.

I shook my head. “Look, I’d better be getting back.”

“Wait for me,” she said, pleading with her eyes.

That was okay. It was getting late in the afternoon. I’d need to get back and help Mum, but ten minutes more was no big deal. But then two of the surfers came back in, out of the water, and Jade went over to talk to them. I didn’t want to hurry her, but I knew it was late, that Mum would be getting wound up. After she’d chatted a bit, Jade came back over to change.

“Rag and Skip are gonna make a fire up top. Let’s stay.”

“I can’t.”

“Oh.”

I watched the guy still out there, and tried not to look too much at Jade changing, fumbling around with a towel and her clothes. The bits of flesh I saw were the colour of honey, or dark sand. Her body was muscly, but curvy too. I’d seen that when she was in her wetsuit. A body shaped by years in the water. The hook twisted.

The surfer – the one who had asked me who I was – was still out there, further than the others had sat, waiting for the last wave. He got it too, a real freak, bigger than all the other waves that day. Jade and the others stopped what they were doing and watched. This guy was good. All the other surfers had moved with the wave, letting it dictate what they did, but he was in charge of it, slicing deep arcs, pulling crazy turns, gouging huge chunks of water out of the wave and sending spray that caught the light in rainbow colours. Halfway along the wave, he pulled one turn too hard, just as the wave was crashing. It punched him into the water, chewing him up in a soup of white water and arms and legs.

“Is he all right?” I asked.

They all laughed. One of the surfers, a stocky guy with curly, long blond hair shouted out, “Cocky bastard!”

Jade was changed now. She came up to me, speaking in a low voice, drying her hair.

“They’re sooooo jealous. They can’t surf like that.” She was still grinning. “Come on. Meet the others, let G know you’re okay,” she said, throwing her wet towel at me.

“Who?”

“Him, the cocky bastard.” She pointed at the surfer getting out of the water. “I spoke to him out there. He’s not thrilled I brought you here.”

“Why did you?” I threw the towel back at her.

“Just cuz you were there, I suppose.” She shrugged.

“What about your dad? Won’t he miss you?”

“Nah. He won’t care. Anyway, Dad’s bike’s got lights on, mine hasn’t, so you have to wait and…” She paused, looking at me. “Where’s your dad, Sam, or is it just you, your mum and sister?”

A lot of people wouldn’t have asked. They would have thought it was nosey. Not Jade.

“Yeah. It is. Just us,” I said.

We’d come back to Cornwall to make peace with my dad’s mum, my grandma, who I hadn’t seen in over ten years. Not since Dad died. And now she was dying. Of cancer. But I didn’t want to explain all that. Not to Jade; not then.

So yeah, it was ‘just us’ in that small house. And right then I didn’t want to be there, unpacking boxes. And Jade was being nice. Really nice. And I thought, How many chances will I get to make friends?

We stayed.

(#ufac75bba-ed4a-58d2-bed8-05e500306047)

BACK UP TOP, beyond the rock we’d climbed around, where we’d left the bikes, was the entrance to the old mine. Another ‘DANGER – KEEP OUT’ sign was stuck on a grille protecting the way in. But they’d cut through the grille then padlocked it back up. Inside they had their own little treasure store: surf kit, piles of driftwood, four-gallon plastic containers full of some brown liquid. Even rugs and a battered old guitar.

One of the gang, a short, wiry kid with sun-blond hair called Skip, made a fire and ran around getting rugs and cushions for us to sit on. Big G – the serious guy with the cow eyes – Jade and me sat where Skip put us. The last of the crew, Rag, brought out two of the demijohn containers. The others were all fit, looked strong, and dressed in jeans and hoodies. Rag was different. He had a gut bulging out from his filthy T-shirt. He wore tartan trousers and finished the look with a Russian fur hat. He looked stupid, but it seemed deliberate.

“My finest batch yet,” said Rag, pouring the beer into mugs. “Guests first.” He handed me one, and poured a little of his own drink on the ground. They all said, “Libations,” and held their mugs to the sky.

“What’s that you’re doing?” I said.

“Libations. An offering to the sea gods.” It was hard to tell if Rag was joking. No one laughed though. Maybe they were just a superstitious lot. I thought it was weird, but I didn’t say so. “Now, Sam, tell me. How is it?” said Rag, pointing at my mug of foaming brown liquid, a serious frown on his face.

I drank, and pulled a squirming face. “This is your best?” I said.

“It’s all right,” said Skip, “you just have to get through the first one. A bit like his songs.”

“Aaah, a request?” said Rag.

“No!” they all shouted. But he fetched the guitar from the mine anyway, and banged out a sketchy folk song while we sat around the fire. He could play and sing pretty well, but he spoilt it a bit when he lifted a leg on the final note and farted loudly.

“Sorry about that,” he said, grinning.

“Liar! You disgusting pig,” said Jade. She got up, and started beating him round the head, while the others fell about laughing.

The dog even barked at him.

We drank. Big G and Rag were smoking roll-ups too, so I didn’t even notice someone had produced a spliff, till it was under my nose. Jade was passing it straight past me to Big G, just assuming I didn’t smoke, and that pissed me off, so I grabbed it and took some. I got an itchy tickle in my throat that threatened to turn into spluttering, but I got rid of it with more of the foul beer. I passed it to Big G, who took a few long drags.

They talked about the day’s waves and their plans for autumn.

“Thank Christ summer’s over,” said Big G.

“I thought you surfers liked summer?” I said, trying not to cough. They shook their heads and smiled.

“Autumn’s where it’s at,” Skip explained, sitting bolt upright. “The water’s warm. There’s no grockles clogging the line up. And we get storms, maybe even a ghost storm.”

“What’s that?” I said.

“A massive autumn storm…”

“An equinox storm?” I said.

Silence.

“What?” said G.

“Equinox,” I explained. “The midpoint between the summer and winter solstices. You get a lot of big storms then, or that’s what’s believed, as the Earth turns on its axis…” I suddenly wished I’d kept my mouth shut.

“You some kind of geek?” said Big G.

“No,” I said, lying. “What’s this ghost storm?”

“I’ll tell you what it is,” said Big G, pointing at me, sounding just as narky as he had on the shore. “It’s a bullshit myth they put in books for tourists, a load of shit about a storm that raises ghosts from shipwrecks. What is true is that storms come out of the blue. Or a bad storm gets ten times worse for no reason. They’re called ghost storms. They’re violent. They kick up big waves that catch people off guard…”

“Like the one that creamed you today?” said Rag, taking off his ridiculous hat and letting his long blond hair fall out. They laughed. I joined in, but the look Big G gave me shut me up quickly.

“What about you? What do you do for kicks?” said Big G.

“Bit of footy. Xbox.”

This got them shaking their heads. “Don’t get it, man,” said Big G, stroking his wispy beard.

“You think I should be out surfing, waiting for the ghost storm?” I didn’t mean to sound like I was taking the piss, but that’s how it came out of my stupid mouth.

Big G picked up a stick and poked the fire. “Last year two miles off the Scillies,” he said, “there was this tiny island with this old dude living on it. Nothing there but one fisherman’s cottage, a small harbour and a smokery. Ghost storm came out of nowhere. A massive wave swept through, north of the island, ripped open a cargo ship like a sardine can, trashed two fishing boats. Then it hit this little island where this guy lived. All gone. The house, boat, everything. No body found neither…”

“How can water do that?” I said. I was curious. Again, I didn’t mean it to come out like it did. I really wanted to know about it. I had reasons to want to know. Good ones. I knew what water could do. But it sounded like I was having a go.

“You know anything about the power of water?” said Big G.

“No, not really,” I said, lying again.

“I’ll show you,” said Big G. He stood, picked up the near- empty plastic container, and poured the last of the beer into his mug …

Then threw the empty demijohn straight at me.

I caught it, but only just. Drops of beer splashed over my jeans.

“What you do that for?” I said. I looked to Jade, seeing what she’d do, but she smiled, like it was no biggy.

“Easy, right? Nice and light,” said Big G, then he picked up the other full one, with both hands and threw it over the flames. I caught that one too, but I fell backwards, with the weight of it. The others froze. No one spoke for a bit. Jade stared at the ground, embarrassed.

“Steady,” said Rag, “the kid only asked.”

Big G sat back down. “Yeah, sorry, mate,” he said. “Just making a point.”

He’d done that all right. That was four gallons. It was nothing. Even a small wave was hundreds of times heavier than what I’d just felt. But I didn’t like how he’d made his point.

“Maybe we’ll get a storm big enough for the Devil’s Horns,” said Jade, changing the subject. They all got stuck into a long conversation then, about surfing these legendary offshore islands when the big winter storms came. I drank more beer. It seemed every time I was halfway through my mug, Rag would fill it up.

I listened, not really able to join in. But I was fascinated. Not so much by what they said, but by them. They were different from London kids. I’d imagined the Cornish would be right hicks, kind of innocent. But this lot seemed… what? I couldn’t say streetwise. But like they’d seen a few things. Done a few things. As they were Jade’s mates, I guessed they were her age. My age. But they seemed older.

“Do a lot of surfers go to these islands?” I said, trying to join in. Rag disappeared into the mine entrance and came back with a surf mag, which he put in front of me, tapping the picture on the cover.

On the cover was an old black and white photo showing a small island, with a lighthouse on it. And in the corner of the picture, in scrawled writing: ‘Devil’s Horns, 1927’. Behind the lighthouse, rising out of the sea, was a giant wave. A dark tower of water curling and breaking, topped by a white froth. It was about to hit the island. Maybe even swallow it. In white letters, against the dark black of the wave’s face, it read:

“No one’s surfed it,” Skip explained. “That’s the point. It’s like the Holy Grail. There’s this old myth about this big wave spot and all the ships that have gone down there. It’s calm most of the time, but in the right conditions it goes off. But there are a dozen islands it could be. More. And who wants to go looking when a storm kicks in? It’s an old fishermen’s legend, you see. No one knows where it is. So no one’s surfed it…”

“No one’s surfed it and lived,” said Big G. “There were two surfers from Porthtowan went missing two years back. Their car was found in Marazion. Some reckoned they’d headed out to the Horns.”

“And you’re going to surf this place?” I asked.

“Why not?” said Jade. “If we could find it. We’ll film it with GoPro cameras, stick it on YouTube. We’ll be fucking legends. Every surf mag in the country will want a piece of us!” She was all attitude and bravado, laughing like it was a joke, but kind of believing herself too.

“But you don’t even know where it is,” I said.

“Detail, Sam! You kook killjoy,” she said, grinning.

My skin was tingling from the sun and fresh air, and the beer and smoke were giving me this lazy, glowing feeling. It was cool, but when another spliff did the rounds it all piled up on me quick and I began to get dizzy.

“I’m going,” I said, standing, staggering a bit.

“Was it something we said?” said Rag.

“No, just got to get home. I’m in enough shit as it is.”

“Might as well make it worth the bollocking, mate,” said Rag. But I had to go, and Jade didn’t argue.

I cycled in front, watching the ground race towards us in the cycle light, with Jade following behind. The moon was up, bathing the moors and sea in silver-blue light. There were no cars or streetlights, just this place, with me and Jade whooshing along on our bikes. I can’t remember what we said exactly – I think she was more wrecked than I was – but I know we held this messed up conversation, her bragging about how she was going to surf the Devil’s Horns, and become this famous surfer. Me taking the piss. Then she sang this old Moby song. A slow, haunting tune. Something about being lost in the water, about fighting a tide.

It was like the theme tune of that night. It filled up my head as I raced along, with Jade behind me, the dog following, watching the bike lights eating up the road.

It was pretty perfect, that bike ride to my new home.

Bye, London, I thought. See you later. Or not.

*

When I got back, Mum was on her knees in the lounge, pulling out Victorian cups and framed pictures from a box with ‘ornaments’ written on the side. The place was a mess of boxes and newspaper. And stuff. Lots and lots of stuff. I couldn’t see where it was all going to go.

It felt weird. Seeing all the things from our London flat, but in a totally different place.

A different place. A better place? I didn’t know. But I was beginning to think it could be.

“Good walk, was it?” Mum said, not looking up, slamming a vase down on the floor, then crunching up the newspaper it had been wrapped in and throwing it over her shoulder. Her bundled up hair came loose. She blew it out of her face.

“Sorry,” I said.

“Where did you go?” She sounded sharp.

“The sea.”

She stood up, grinding her jaw. “Do you know what time it is?”

“No.”

My head felt like a balloon that needed to take off. Being stoned and drunk had felt good out there, cycling over the moors in the moonlight. But now I was closed in by this maze of boxes, with no escape from Mum’s laser stare.

“Did it occur to you I needed help?” she said, with her hands on her hips.

“Yes.”

“But you stayed out anyway.”

“Yes.”

“And why did you do that, Sam? With a whole lorry-load of boxes to unpack… We’ve got to go and see your grandmother tomorrow, and you’re starting at a new school on Monday. Do you even know where all your stuff is? Where your new uniform is?”

“Not really.”

“Not really? You either do or you don’t. Well perhaps you might… SAM!”

“What?”

“Look at me.” She stormed up to me. “What’s wrong with your eyes? They’re bloodshot.” Suddenly I was freaked, like I was totally scared but about to burst out laughing at the same time. The maze of boxes was closing in. I felt really out of it. I was thinking, I probably look wrecked too.

“Have you been drinking?” she said, sniffing the air.

“Yes, I had a beer,” I said. There was no chance of the silent treatment – this was going to run into a full rant. I got ready to take it on, already planning my escape route and excuses. But then she turned away and sighed, looking over the sea of boxes and newspaper-wrapped ornaments with this odd, empty look. Like she didn’t even know what those things were. She looked well and truly knackered.

“Just go to your room, and sort out your stuff. And get Tegan to bed too,” she mumbled. “There’s cold fish and chips if you want them.”

I didn’t. I wanted to get away, quick as I could.

Teg’s a good kid for a six-year-old. I love her, but she’s always been a nightmare at going to bed. And especially, it turned out, when she was in a new house. She eventually got into her pyjamas and stood in front of the chipped bathroom mirror practising jerky dance moves instead of washing, or brushing her teeth.

“Mum’s angry with you,” she said.

“I know,” I said, leaning against the wall.

“Jade’s nice. I like her dog. Is she your friend?”

“I dunno. I hope so.”

“Is she your girlfriend? Did you kiss her?”

I laughed. “No, Teg. Now brush your teeth.”

After a lot of begging, I put her to bed and read her a story. A story? The story. The Tiger Who Came to Tea. The one story she’d loved since she was three; the one story that was sure to get her wrapped up in her quilt, and listening. Sometimes she was asleep before I even got to the end. Not this time.

“Can we look at stars?” she said, as I walked out the door of her room.

“Sure, but not tonight. I haven’t unpacked the telescope. Goodnight, Teg.”

“But Sam, there’s millions of them. I can see—”

“Goodnight, Teg.”

*

My room was in the attic. Mum or the removal guy had put the boxes marked ‘Sam’ in there. And there was my telescope in the corner, all bubble-wrapped and Sellotaped, waiting to look at the stars. I didn’t start unpacking. I fell on the bed and listened to the distant white noise of the sea. Through the skylight I could see the stars. Even with the moon up, there were more of them in that sky than I’d ever seen.

When I closed my eyes, I could still see the waves, and hear Jade singing.

(#ufac75bba-ed4a-58d2-bed8-05e500306047)

I DIDN’T REMEMBER anything about Grandma. And I only knew what Mum had told me. That she was old and dying of cancer. That she had months left.

Maybe.

She lived in a massive house near a rocky point called Cape Kernow. A house that would be ours one day.

We’d come back, Mum said, so Grandma could get to know her one grandchild and only heir. That was me, Tegan being the result of a fling that had lasted the time it took Mum to get pregnant.

Things were pretty broken between Mum and Grandma, I knew that. They didn’t get on. There’d been some fallout after Dad died. Maybe because Mum took us to London. Mum never told me. Now we’d come back to Cornwall to help ‘mend’ things, though I didn’t have a clue as to what it was that needed mending.

I had an idea of some old manor, all dank and dark and smelling of cabbage and cat’s piss. I pictured my grandma in a huge bed, with grey hair and greyer skin, fading away, with us at her side, listening to her final, totally wise words.

I was wrong.

The house was big, square and white, with large windows and a front door painted ocean blue. The house’s name was painted on the wall in thin black letters. ‘Where Two Worlds Meet.’

A short, skinny, tanned woman answered the door. She was dressed in jeans, a smock and headscarf. At first I thought maybe she was the cleaner.

Wrong again.

Grandma had these bright blue eyes that seemed a whole lot younger than she was.

“Oh, Sam,” she said, then flung herself at me and held me tighter than anyone ever had.

“Grandma?” I said, hugging her back. Kind of. I felt embarrassed. She was a stranger. She stopped hugging, but got a good hold on my shoulders, like she wasn’t going to let me go. Not after all this time.

“My God, if he could see you now.”

“Hello, Grandma,” I said. It was odd. She was a total stranger, but she had the same eyes and square jaw as my dad. And yeah, I could see how I looked like her too.

“And you must be Tegan,” she said. Teg got ready for a big hug, but all she got was her hair ruffled.

Grandma left Mum till last. “Hello, Jean,” she said. They air kissed. Mum had a frozen smile on her.

But Grandma was really smiling. She was so happy, she was working hard to stop the tears.

“Are you… okay, Grandma?” I said.

“Never better, Sam. Come in, the kettle is on. There’s scones too.” She wiped the tears away and led us through a hall to a large lounge on the other side of the house. There were huge leather sofas and chairs, and dark red rugs covering the wooden floor. The walls were white, with bookshelves, a mirror and paintings of the sea.

But what I noticed most was the view. The house was so near the cliff, when you looked out the window you didn’t even see rock, or land, just this great big blanket of blue and green.

We sat down, while she went out to get the tea. We didn’t talk, we just sat there, taking it all in.

Grandma came back with a tray loaded up with scones and cream, jam and tea. Before she organised it all, she set Tegan up in the biggest chair, by the fireplace, with a set of crayons and a pad pulled out of a WHSmith’s bag.

She glanced at Tegan, to make sure she was distracted, then said to me, “I hope you like the house,” and gave me this weird loaded look. Then I twigged. She meant, the house I’m giving you; the house you’ll live in when I’m dead. She was going to die. We were getting the house. Some people dodge around the awkward stuff, the big stuff. Others just get to it. She was one of those. I didn’t know what to say to that.

“We’ll sort all that out,” she said, seeing the look of confusion on my face. “There is so much to plan. But first, tell me all about the move, your new cottage. What you have been up to…”

She talked on and I answered as best as I could. It was nice, but I thought it was weird how everything she said was to me, not Mum. All the time she was staring at me, real keen, and I couldn’t help but stare back. Apart from the headscarf, which I guessed was to cover her bald head from the chemo, she didn’t look ill. Not even that old.

“So, Sam. You’ll make friends here. At your new school. It’s hard to go from one place to another, where you’re a stranger. But you’ve done it before; I’m sure you’ll cope.”

She didn’t look at Mum when she said that, but the way she said it… it sounded like a dig.

“He’s met a girl,” said Tegan, scribbling away with the crayons.

“Excellent,” said Grandma. “Is she a looker?”

“Um, yeah, I guess so,” I said, “but we’re just mates. Not even that. I only just met her.”

“Are you going to ask her on a date?”

“I don’t think she goes on… dates. She’s a surfer.”

“Wonderful. A girl and a healthy activity.”

I thought maybe if Grandma had seen us round the campfire, she might not think it was such a great choice of ‘healthy activity’.

“Er, yeah,” I said, feeling awkward.

We changed the subject. All the time we talked, Grandma stared at me. A lot.

“You’re the spit of him at your age; it’s uncanny. It’s like the ghost of his teenage self came round for tea and scones.”

“Thanks,” I said, and spluttered some cream out of my mouth. I couldn’t help laughing. Grandma laughed too. Mum didn’t.

“Do you remember him much? Do you remember this house?” Grandma asked. I dug into my mind, tried to remember stuff, looking for something. Anything. I felt bad not giving her what she wanted.

“I helped him paint a boat once, like a sailing or maybe a row boat. I remember this dark blue paint and getting it all over my T-shirt. And he used to take me in the sea, paddling. He’d lift me up when a wave came, and say, ‘It’s only water, Sam,’ and…” But there was no “and…”. That was pretty much the total of my memories of my drowned, dead father. It didn’t upset me going through those memories. It didn’t make me happy either. I was kind of removed from them, like they were someone else’s memories.

It was different for Mum though. She didn’t say anything, but her eyes were wide and worried, darting from me to Grandma, and back again.

Then …

“That smell…” I said it before I even thought it. What was it? Leather, baking, the sea, the coal fire? All of those things together. And I remembered it. The smell of the house, and the heavy tick and tock of the clock in the hallway, with the sounds of sea and wind muffled through the walls. I wasn’t just imagining it – I did remember being there.

“I only just recognised it,” I said. “How weird is that?” I was spooked. In a good way. I was going to go on, but I clocked Mum, her eyes filling up, her hand gripping the side of the chair.

I was trying to find my memories. Maybe Mum didn’t want to find hers.

“Your mother and I need to talk,” said Grandma. “Have a look around the house. You’ll find your dad’s room up there.” She pointed at the ceiling. “There’s a few of his bits and bobs; a few things that didn’t get thrown away when you upped and left for London.”

Mum clunked her cup on the saucer and glared at a painting on the wall. She was grinding her teeth, stopping herself from saying something.

It was a good time to leave them to it. Me and Teg went upstairs. Teg was chewing her hair. I held her hand.

“This must be weird for you, Tegs. He wasn’t even your dad.”

“No, but she is my grandma,” she said, like she was totally sure it was true. I didn’t want to tell her different. We were a tight little team, me, Tegan and Mum, but there were only the three of us, and if the family got to grow, by one, that was cool. Even if it wasn’t going to be for long.

“Are we going to live here one day?” she asked. She’d clearly overheard some of what we’d talked about.

“Yeah, maybe.”

“But we live in the cottage now.”

“Look, it’s complicated. I dunno what’s going to happen.”

“Will we go back to London?”

I couldn’t blame her for asking. The situation had to be pretty freaky for her. I just didn’t know how to answer. “Reckon she’ll see how it goes down here. Mum might not decide till… later. Would you like to live here?” I said. Tegan looked around the hallway, with its big wooden doors and huge window looking over the moor. She nodded.

“Which one would be my room?” she said.

“Any one you want, but you got to bags it.” This was a game we played for slices of cake or the best place on the sofa. Now it was for something important. Her eyes lit up like it was Christmas morning. She let go of my hand and ran off to explore.

Either by fluke or some old memory, I went straight to my dad’s room. I thought it would be tidy, because the rest of the house was so neat. But it wasn’t. It was a mess. The curtains were closed, but thin, letting in a strong light. There were a load of boxes with books in. In the corner was an old record player, and a chunky grey computer from the Stone Age. On the shelves were more books, all of them about the sea. And some old metal instruments, covered with dials and numbers and cogs. I guessed they were navigation instruments.

He had clearly been a total geek. Now I knew where I got it from. He’d been an oceanographer; a scientist who looked at how currents and gulf streams and storms worked.

I was a geek too. With me it was the stars. With him it had been the sea. There was a whole new world to explore. A world of water.

I wanted to sit down and start going through all the gear, all the books. But the voices downstairs started rising. I couldn’t hear what they were saying, but it didn’t sound friendly.

“Sam!” It was Mum’s voice, shouting up the stairs.

“Just a minute.”

Mum was waiting downstairs, with Tegan, already with their coats on. Grandma was by the door, ready to open it.

“We’re going. Now,” said Mum. There didn’t seem much point asking why.

“You can come back though, Sam. Soon,” said Grandma. “Did you find anything of interest?”

“Yes. Thanks. Loads,” I said.

I hugged her.

(#ufac75bba-ed4a-58d2-bed8-05e500306047)

IF YOU’D CALLED them a gang, they would have laughed. But that’s what they were and everyone at Penwith High knew it. The Penford Crew, the Penford surfers. That’s what the other kids called them.

They didn’t really mix with anyone else, only the older lot in the sixth form over the road. The ones that surfed, that is.

If you’d said they had a leader, they’d have laughed at that too, especially Big G. But if you saw more than two of them together, Big G was there, in the middle, towering over them, looking a good two years older than he was, talking about what the waves were doing.

I didn’t know them, but from the little I’d seen, I could tell he was the most sensible. Little Skip was a bag of energy, not knowing where to spin off to next. Rag was a stoner and a joker. Big G was quiet and strong, with a rep for fighting. And Jade? I didn’t really know yet. But she seemed like trouble.

I think Big G kind of levelled them out. They looked to him to organise them. So he’d stand, arms folded, eyes staring through his mop of long, dark hair. If he didn’t reckon the surf was ‘on’, one might go, but most didn’t. If he said it was good, they all found a way. Before school, after school, weekends. Homework, family meals, out-of-school jobs delivering papers or working in cafes – none of it mattered when the waves kicked up. Once they were all off school sick, and turned up the next day suddenly better. Everyone knew where they’d been, but no one could prove it. And even if they could, no bollocking from a teacher or parent could wipe the glow away. For that gang, it was always worth it. Surfing came first. It gave them an edge, something different. They even seemed older than the others in my year. It was like everyone else was going through school, waiting to start life proper. They’d already started. In some ways, at least.

I would have liked to have been a part of it, after that first day at Tin-mines (all the spots had names – it was part of the surf thing), but if you didn’t surf, you weren’t in. And even though Skip and Rag were friendly on the first days of term, they pretty much ignored me after that.

I hadn’t conned myself into thinking I’d be their mate, but I’d hoped for something different with Jade. Largely because she was the hottest girl I’d ever seen. We got the school bus together; we lived next door. But at the bus stop was the only time she seemed to remember I existed. Apart from when we got difficult homework. Then she became my friend all of a sudden, and didn’t even try to hide why. Jade wasn’t thick, but to get what you needed to do at home you had to listen in class. And unless it was English or Art, Jade didn’t listen. At all. School bored her. The teachers bored her. The other kids bored her. She was friendly with the other girls, but none of them were like best mates. She only really talked to the other surfers. I took my notes in class, half focusing on the class, half watching her dream the day away, with her mind in the sea, knowing that later we’d be on the bus and then she’d wake up to the fact that she’d been at school for the last six hours, and she’d shove a textbook under my nose and say, “What does this mean?” Especially if it was science. My speciality. Which was half good, half bad, as I hated looking like the geek I truly was. But I also liked helping her out.

So I didn’t make friends with the surfers, but I wasn’t Sammy No-Mates either. I made two friends. Mike and Harry. They liked my Xbox, and stargazing through the telescope, and sometimes we kicked a football around. But the truth is, when I played Xbox with them, I was thinking about sitting around the campfire with Jade and her mates. I was thinking about another sunset at Tin-mines. But I didn’t surf and Jade never invited me down to the beach again.

The idea of surfing crossed my mind, but I couldn’t really swim well and we were too hard up to buy things like surfboards and wetsuits. And Mum wouldn’t have been keen. Not after Dad and what happened. So I pushed the idea away. But it nagged at me. Every time I went to sleep, listening to the sea.

*

I’d been there three weeks or so, when, on a sunny Sunday morning, Jade appeared at our front door with her dog, Tess, asking me to go for a walk. She wore trainers, jeans and a hoody, with the same denim jacket she always wore and no make-up. London girls tried a lot harder than that. Jade didn’t need to.

“No surf today then?” I said, standing in the doorway, trying to act like I wasn’t keen on the whole walk idea. She brushed the hair out of her face and looked away, in the direction of the sea.

“Honestly? Yeah, there is. But I stayed out late last night…”

“How late?”

“About two o’clock late. So Dad kind of grounded me. He’s locked my boards away, the twat. If I go off by myself, he’ll know I’m borrowing gear and going surfing, but if I’m with you…” She shrugged. That was why she was asking me to go for a walk. There were no other options. I could take it or leave it. I didn’t like it, but the alternative was homework.

We went to the sea on our bikes, with Tess following. Not Tin-mines this time. We hit the coast path, locked the bikes to an old railing and walked towards Whitesands.

She led me along the cliff and down a steep, rocky path, over the dunes to the deserted beach. We walked where the sand met the dune grass. White-grey granite cliffs stood at one end of the beach with a headland at the other. Inland the honey-coloured moor was spattered with soft purple heather. I’d started to love Cornwall by then, its beauty and its wildness, but I knew better than to go on about it to Jade. She took all that for granted. She didn’t know any different.

The sea was a mass of wind-smashed white peaks and dark blue troughs, with the odd shoulder-high wave trying to make a shape in all that anarchy. Jade looked at it. Hungry.

“You know, you’re mad to live here and not surf,” she said.

“I don’t like the water much.”

“What? Why?” She frowned like I’d said the most stupid thing possible. I thought we might get into it then; I thought I might tell her about Dad. But then we heard a loud cry. The scared cry of someone in trouble.

At the far end of the beach was a young girl – maybe eleven or twelve – in a wetsuit, standing knee-deep in the shore break. She was shouting and waving at the sea. A surfboard lay on the sand behind her.

“That’s Milly,” said Jade. “She’s far too young to be out by herself. Where’s her mum? What the hell is she doing?”

Jade started running. I followed.

The girl was shouting at her dog, a Jack Russell, which was caught in the surf, drifting out, really quickly, like it was being pulled on an invisible rope. Its eyes were wide with panic. Tess started barking like crazy.

“The dog’s in a rip,” said Jade.

My blood iced. “Um, we should… er…” I said. I sounded weak, feeble. I felt that way too. Jade gave me a look like a whiplash.

“I’ll take care of it,” she said, starting to strip, chucking her clothes on to the wet sand.

“No! I’ll go,” I said.

And that was it. Three simple, stupid words. I didn’t think about it; I didn’t weigh it up. I just didn’t want to look as pathetic as I felt right then. So I went. Because drowning’s better than looking weak, right?

“I’ll come too,” said Jade, undoing her laces.

“No!” I said. “It’s okay. I can do it.” I was acting like Clark Kent, ripping off his clothes to reveal his Superman costume. But there was no Superman underneath. Just my weedy, shaking body. Every inch of my skin screamed at me not to do it, but I watched myself like in some out-of-body trip, kicking off my boots, picking up Milly’s sponge surfboard, and running in.

It got deep, quickly. The cold water shocked me, its energy washing round my legs, soaking my clothes. Even the sand turned to liquid under my feet. The shore was only a few feet away, but once my feet lost touch with the sand it might as well have been a thousand miles.

I jumped on the board, dug my hands in the water and paddled. It was frenzied and clumsy, but somehow I moved forward, wobbling side to side, gasping and spluttering as I crashed through the chop, salt water catching in my throat and smacking me in the eyes. I had no idea what I was doing.

I must have been caught in the same rip as the dog, because I went a long way very quickly, but once I was out there, beyond the shore break, I couldn’t see the dog. The sea was getting smacked around by the wind and I was rocking madly, trying to stay on the board. It was chaos.

I didn’t even see the first wave – the first proper full-of-aggro wave – till it reared up in front of me. I paddled over the top and plunged downwards. A miracle. I was almost relieved, but there was another wave that had been hidden by the first one. It was bigger, but again I made it, just before it broke.

Then the third one came. A solid wall of water. As it pushed me backwards it paused, long enough to let me know what was happening. Then it tore the board from my hands and pummelled me into the sea.

There was no up, no down, no light, no dark. The world was replaced by a tornado of blue fury, and I was in the heart of it, churning over and over like a ragdoll in a washing machine.

It seemed to take forever. When it had finished, my lungs were bursting, and I was filled with sharp, high-pitched panic. A panic that had me by the heart and throat. I pushed and kicked and swam, desperate to get to the surface.

Seconds passed like years.

Eventually I surfaced, but instead of air I breathed foam, a lungful of froth that had me choking and hacking.

The next wave hit me like a truck. No spinning this time, this one just ground me downwards. Down deep, I opened my eyes. Seeing nothing but bruise-coloured dark, I panicked. Full on. My body gave in to it and I breathed water into my lungs. I heard the next wave roll over me. I swam upwards expecting another wave, half thinking there was no point because this merciless bastard force was going to keep hammering me till I gave up.

But then…

Swimming up, I saw turquoise light. The daylight world of land and air. The world that I’d been torn from was there. Just there. If I could only… get to it.

I surfaced, spasming coughs and gasps.

There was the dog, the Jack Russell, right beside me. Lucky for the dog. I would have gone back and not even have remembered it. Right then I’d have done anything to be back on land, but there the dog was, and I clung to it. I kicked my legs and thrashed with one arm and we slowly headed to the shore.

Hands and arms dragged me from the water. They had to get the dog from me. I didn’t want to let go. I tried to walk, but the sea had robbed me of strength. I felt like I was liquid. I bent over and puked.

I stayed like that a while, coughing and puking, water pouring out of my nose like a fountain.

Time slowed. I closed my eyes. I listened to the thunder in my ears. Slowly I began to breathe again.

I looked up. There were a few of them surrounding me, including Big G in his wetsuit, holding the girl’s board and grinning with delight. I’d never seen him smile before.

“Nice work,” he laughed. Skip was there, hopping about; Rag, a few others. The girl, Milly, was playing with the dog in the sand. Her mum appeared, a blonde woman, in wellies and a scarf. Posh-looking.

“I’m so sorry. I went back to the car to get a flask of tea. I was only gone a moment. Thank you so much. Biscuit owes you his life.”

A mock cheer filled the air. Everyone was smiling and laughing. Clearly what had happened was No Big Deal.

What?

I focused on standing upright and forcing a smile to my numb face, while streams of snotty water ran from my nose.

Big G and his mates picked up their boards and headed past me.

“You’re a hero,” said Skip with a nod.

“Rescue me if I get in trouble,” said Rag with a wink.

Milly and her mum walked off, making a fuss of the dog.

After they were gone, Jade clapped and whooped. When I didn’t react, she put her hand on my shoulder.

“You’re okay, right?” she asked.

“I’m fine!” I pushed her hand away and fell down on the sand. I was shaking. Numb. I was freezing too.

“Come on,” she said, “let’s get you back.”

I didn’t move at first. I didn’t even speak. I had to figure out what had just happened, had to try and put it all in some kind of order in my head. I’d nearly killed myself. Why? For the dog? No. I’d done it to impress Jade. I’d nearly drowned to make myself look good in front of a girl. The only upside was that if I hadn’t gone, I’d have been sat looking at Jade rescue the dog.

It was a pretty messed up situation all round. Half of me was telling myself what a kook I’d been, how I’d been lucky not to drown, how I’d never, ever do anything like that ever again. Ever.

The other half of me was buzzing something stupid.

(#ulink_c5fa03f9-5e8a-5787-bc7a-37de087b1491)

THE ONLY TIME I’d seen her hideaway above the garage was that first day, when she’d taken me to Tin-mines. I hadn’t been allowed in. But now I was. She didn’t want to have to explain anything to her dad by bringing me to the house.

I shivered as I stripped off my wet clothes. She didn’t do me the favour of looking away as I got down to my pants. Every time I leant forward, a fresh stream of snotty water poured out of my nose. I kept coughing up water and couldn’t get the salt sting out of my eyes.

There was a makeshift bed there, of rugs and blankets on old crates. Jade made me lie on it.

Apart from the bed, there was an old captain’s sea chest and a blue rug. Driftwood shelves had been clumsily nailed on to the white painted walls. She had books, and a pile of tattered surf mags. On the wall, a few torn out and stuck up mag pics of girl surfers.

“Who are they?” I asked.

“Layne Beachley, Lisa Andersen. Old school surfers who carved a space for us girls in the water.”

“You going to be like them?”

“Nuh-uh. They’re competition surfers. I’m going to be a big wave surfer. Sponsored. The first famous UK female big wave surfer.”

“The Devil’s Horns?”

“Yeah, when one of those storms come. What did you call it, equinoocibingbong?”

She’d remembered what I’d said that first day, even though it had been weeks.

“Equinox,” I said.

“Equi. Nox. Cool word. You know about that shit, huh?” She eyed me up. She wasn’t teasing.

“You get bigger storms in autumn. Ever wonder why?”

“Nah. I just want to know when the swells are coming. If I get footage of me surfing the Horns, I’ll be made. Sponsorship, free boards and travel, the works.” She looked up at the pictures with a glazed far off look in her eyes, then snapped out of it and turned back to me.

“Spliff?” she said. But I shook my head. She didn’t ask me about the vodka. She just got a flask, metal cup and a leather tobacco pouch out of the sea chest, then poured me a drink and started rolling herself a cigarette.

“Drink,” she ordered. I took it off her with a trembling hand.

“What’s wrong with me?” I said, trying to laugh.

“Bit of shock.”

“I did nearly drown,” I said. The vodka burnt my throat. I liked it.

“You got slapped about a bit, but you were close in. I was there, Big G too. I’d have got you if you’d been in trouble.”

“If? I nearly drowned,” I said again, glaring at her. But she was focusing on rolling her cigarette.

“How long do you think you were down?” she said.

I thought back, to what it had been like under there, to what had happened.

“A minute. Two?”

“No, you kook! Fifteen, twenty seconds. Then you came up, and then you were down another ten. It feels like everything, but it’s nothing. It helps if you count when you’re down.”

“Count what?”

“Count the seconds. If you know what you can do on land, you know you can do it in water. It helps keep the fear off. Ten seconds down there can seem a lot longer than it is. If you surf, you get used to hold-downs.” Jade put the roll-up in her mouth and lit it, checking my face to see if I got what she was saying. “You get to like it.”

“Like… it…?” I said slowly. I’d liked it afterwards, sure. I’d felt good. But at the time?

“It was scary, right?” she said. “But you came out the other side. Didn’t it feel good?” She was calm now, focused.

“I don’t know,” I said. It was the truth. I didn’t know what I’d felt. Scared? Freaked out? Thrilled? Battered? All those things. But mostly just really alive. And I felt good I’d had a go. If she’d had to get in and rescue that dog, Jade would have been disgusted with me. Instead, here we were, talking about my adventure. And I liked her looking at me the way she did, legs crossed, smoking her roll-up, staring coolly, like she couldn’t quite make me out.

“Next time hold your breath,” she said.

“Next time? You’re funny.”

“I practise in the bath.” She reached out, took the cup off me, drank some vodka, then gave it back. I imagined Jade in the bath. Then tried to shake the idea away before I went red. Or got a boner. “I hold my nose and count, put my head under and see how long I can do. It’s not the same, but it helps train for hold-downs. You were brave. Tell Tegan. She’ll be dead proud of you.”

I had my reasons not to. I had my reasons not to tell Teg or Mum that I’d nearly drowned. Good ones. They’d have freaked.

“…and I didn’t know you couldn’t swim,” she added.

“I can swim!”

“Not really.” She squeezed the white cold flesh of my shoulder with her warm fingers. “See. Weak as shit. It was stupid of you to go in. But cool. Maybe you’ve got potential, even if you are a kook.”

Potential for what, I thought.

*

I went home once my clothes were dry. I made excuses about needing to do homework, and went and lay on my bed, watching clouds through the skylight.

Thinking.

My dad had drowned. And I wasn’t much of a swimmer. I had plenty reason not to get in the water.

But that kind of pissed me off. You shouldn’t always run away from things, should you? Sometimes, the things you are afraid of are the things you need to face up to.

I liked how I’d rescued the dog, and I’d liked lying in the den talking to Jade about it. But I hadn’t liked looking weak, like I’d almost needed rescuing.

Jade didn’t need to face up to anything. She had no fear of the water. She loved it. She loved surfing. She was happy to let it rule her life.

And I liked Jade. I liked her a lot.

I lay there a good hour, just thinking about what had happened.

About Jade. About surfing.

(#ulink_81b0aea2-f09c-531a-8999-f92ad1453764)

I GOT SKIP by himself, at school, by the water fountain.

“All right?” he said, wiping water off his lip, ready to bounce off somewhere.

“Can I ask you something?”

He put his bag on the floor and leant against the wall. “What’s up?”

“I want to surf.”

“Is that all? Jesus, you looked so serious. But you? Surf?” He shook his head. “You sure that’s a good idea after the other day? No offence, dude, but you were a real kook in the water.”

“Will you teach me?”

“There’s surf schools for that,” he said, laughing.

“I don’t want to wait till next summer…”

“They do stuff at weekends. You get to wear a yellow rashie, with ‘surf school’ on it. Might as well be an L-plate. You’ll stand out from the ten-year-olds.” He picked up his bag and started to walk away.

“Is that how you learnt?” I shouted after him. He turned. Suddenly it wasn’t a joke.

“No, I just did it. Got in, kept at it till I rode green waves. Straight up? It’s the only way. Even if you get a lesson or two, to start you off, then you got to go at it full on, for a long time.”

“Right, but you could help me?”

He came back, and spoke slowly, so I’d understand. “Me? Like I get enough hours in the water and I’m going to waste time teaching a kook. And anyway…”

“There’s only one teacher,” said a voice from behind me. Big G put a hand on my shoulder.

Shit, I thought, he must have heard it all.

“You. Surf. Why?” he glared at me.

“You need to ask, if you love it so much?” I said, giving him back a little of what he dished out. His eyes narrowed.

“I can guess. You won’t get anywhere. You’re wasting your time,” he said. He leant down, took a long drink from the fountain, then walked off.

“I live here. Why shouldn’t I surf?” I said to Skip.

“He was talking about Jade. That’s what he meant when he said you won’t get anywhere.”

“Oh. That’s… it’s… that’s not why,” I stammered, feeling hot in the face.

“Some have had a go, you know,” he said. He rolled his eyes when he saw my shock. “I don’t mean been there. I mean Rag tried it on with her, and G. Maybe he did more than try… She doesn’t seem that interested. Maybe she’s into girls. That’s what Rag reckons.”

I was burning up wanting to ask about that. But I didn’t.

“I just want to learn to surf,” I said, casual as I could.

“Whatever.” He picked up his bag, then hesitated. “By the way, how much?”

“What?”

“How much were you going to pay me? To teach you.”

“Nothing. I just thought…”

“Shit, you really are a kook,” he said, unable to stop himself smirking. “But thanks, you’re funny. You’ve made my day.” He smiled, winked and walked off.

*

I tried my luck with Rag. He got the same bus as Jade and me, but was always almost missing it. So I went to the lockers at the end of the day, knowing he’d be pissing about with books and bags. I wanted to get him alone, but he was talking to two girls.

“Rag. Have you got a mo?”

“Shoot.”

“It’s a bit… Can we talk… alone?”

“Oh, right, yeah,” he said, nodding, like he already knew what we were going to talk about. “’Scuse us, ladies.” He put his beanie over his mop of curly locks, put his arm round my shoulder and walked me out of the building. He looked over his shoulder a couple of times before he whispered in my ear.

“I don’t know who told you about me, but they’re fucking dead! I can’t get expelled. I want names, you hear? Then G will have a word with the loose-tongued bastards. Anyhow, seeing as you’re here… Mind-fuck or Mellow Summer’s Day?”

“What?” I said. I had no idea what he was talking about.

“The Mellow’s better in my humble, but most dudes go for the bang-you-into-a-coma gear. God knows why. Its proper name is Cheese or something, but I call it Mind-fuck, so no one says I didn’t warn them.”

Then I twigged. He was talking about weed. Rag dealt drugs.

“I don’t want any weed.” I said.

“Then why are we talking?”

“I want to surf. I was thinking you could help me.”

“I ain’t got the time, man.” He took his arm off me. “Sure you don’t want any weed?”

I shook my head. “I know you won’t teach me but… some tips?”

He scratched his stubbly chin.

“Sure. Don’t do it. It’s bastard hard, and distracts you from other stuff you should do. Like live your life.” He raised an eyebrow, looking serious, like he was thinking about some deep subject. “On the other hand, it’s the best thing you can ever do. Better than girls and spliff and… other stuff I can’t think of right now. That’s just my opinion. But it’s also a fact. Any surfer will tell you the same, or they’re lying. I haven’t even got it that bad, but every idiot I know who stuck at it has. Does that help, Sam? How much were you thinking of paying me anyway?”

I tried not to look too hacked off.

“Okay, forget I asked,” he said.

“How am I supposed to learn?”

“There’s only one teacher.”

“What does that even mean, Rag?”

“You’ll see. Need a board?”

“Yeah.”

“Come round Saturday morning. My bro’s got some stuff too shagged to sell to the shops. He’ll give it you cheap.” He gave me the address, and said I’d find it easy.

(#ulink_408eae17-b364-5bfe-a0ff-e7b9a2d6db51)

I WAS DEAD PLEASED Rag was going to help me. But even if he hadn’t, I’d have found a way.

I had a lot to prove. To myself. But to Jade too. Even though I had no idea how she’d react. Would she be pleased? Or would she just piss herself laughing? There was no point worrying about it. I’d decided.

Rag lived on a council estate on the moor side of a small village called Lanust. All the houses were dull and granite and square. Rag’s house stuck out because of the choice artwork above the garage door. It was a graffiti-style spray job, about four feet high, showing a grown-up, sexy Red Riding Hood. She had a basket full of spray cans instead of apples, and with one in her hand had scrawled a message next to her, in spiky red letters, two feet high:

A thumping rap tune was blasting out of the window. It took a lot of knocking before the door was answered.

Rag took me to the garage to meet his brother, who was exactly like Rag only older, about eighteen, and perfecting the stoner look even more than Rag, with scraggy, thatched hair, a wispy beard and glazed, bloodshot eyes. There was no sign of any kind of Responsible Adult.

If Aladdin had been a surfer, his cave would have looked something like Rag’s brother’s garage. At one end was a workshop with a bench, with a half-finished board on it, and a shelf with masks and sanders. The floor was covered with a snowfall of ground white foam. Next to the bench was a line of clean, white, new boards in a rail. In the middle of the garage there were more rails, with more boards. New, old, long, short, wide, thin, white and stainless, yellow with age, smooth and pristine, dinged and knackered. Boards with single fins, boards with three fins, boards with pointed noses and pinpoint tails, longboards with blunt noses, boards with ends shaped like fish tails. At the back there were no rails. It was just a messed up mountain of boards and suits.

All round, Aladdin’s surf cave.

Seeing all this made the whole ‘me surfing’ thing very real, and not just about Jade. I thought riding one of those things might feel good. And going out in the sea and not almost-drowning might feel pretty good too.

“Ned buys and sells, fixes and shapes,” Rag explained. “Good to make a crust doing what you love, right?”

“What do you like to ride?” said Rag’s brother. “If I don’t have it, I can get it.”

I reckoned that, dopey as they looked, Rag and his “bro” might just be canny little business heads, and would probably buy or sell anything. If the price was right. And especially if what you were buying or selling was exotic herbs or surf kit.

“He’s a virgin,” said Rag, slapping me on the back. I waited for the piss-take, but it didn’t come. Instead Ned was friendly, but kind of serious.

“Okay.” He leant back, eyeing me up and down, measuring me up.

“Weight, age, fitness, how much fat on you, how much muscle, how good at swimming are you, how many press-ups can you do, how flexible are you?”

I gave him the answers, and I didn’t lie.

“I’d say foam or pop out usually,” said Ned. “Starter boards with soft tops or a factory-made shape, but they don’t do you favours in the long run. I got a custom that might be good for you.”

“Custom boards are hand crafted, Sam,” said Rag, waving his arm around the garage. “Every one is different, made for riders with different weights and abilities and for different types of surfing.”

I had to admire the sales rap. I put a nervy hand in my pocket. Seventy quid. My life’s savings. Plus a tenner ‘borrowed’ from Tegan’s piggy bank.

“You gonna do this, proper like?” said Rag. I nodded. “Then you need something that’s big and stable, but which still goes nice. Know what I’m saying?”

A board had already caught my eye, a long one, sun-red, about eight, maybe nine feet long, pointed and thin, like a rocket, but thick.

“How about that one?” I said.

They smiled like I was a five-year-old asking to drive his dad’s new Porsche. Rag ran a finger up the board’s rail, with a dreamy look in his eyes. I’d seen Jade do the same thing with a board, the day I met her, and it seemed strange to me.

“This, my friend, is a gun. A big wave board. This board is more than ten years old. It gets taken out twice a year, by Ned. If that. Put in a few years, hope you’re not busy when the storm hits, maybe you’ll get to ride a board like this one. There’s a few of these in sheds and garages round here, gathering dust, waiting for the day.” He snapped out of his daydream and got back to the business of selling.

“How about Old Faithful?” Rag said to Ned.

“That’s what I was already thinking,” said Ned. They got busy in the messy heap of boards and suits at the scrappy end of the garage. The board they pulled out was about a foot taller than me, yellow, wide, thick with three fins at the back. It was fatter, older and more battered than any other board in the place. Covered in dents and patches of fibreglass, where it had been dinged, and fixed.

I could feel the sting of being ripped off already, but Ned looked at it like it was a work of art, something he really cared about.

“We used to keep it under the lifeguard hut at Gwynsand. Anyone could use it. It’s good for small, good for big, good for learning, with enough rocker to be forgiving, but flat enough to glide. A nice all-rounder. Don’t go pulling air though.”

It sounded good, even though I had no idea what they were saying. But the look of the thing told me the truth. I felt heavy inside. They were going to flog me a board they had no hope of selling to anyone else and take me for every note in my pocket.

All the same, I took it off them, felt the weight of it. It wasn’t light but lighter than I’d expected from its size. I looked it over, and generally tried to look like I had a fucking clue.

“How much?” I said.

“Depends. You want a suit too?”

“Maybe.”

Rag patted his gut. “Before I graduated to the school of longboard, when I was all slim and lovely, I had this Ripcurl summer suit …” He dug into the mountain again and came out with a greying suit, with loose stitching and a couple of holes in it.

“Try it on.”

Now I knew this was a joke, as well as a rip-off. I stripped to my pants and put the suit on. Pulling and panting I squeezed myself into it. It took a while. It fitted, a bit too much, and it stank. If me doing this was anything to do with impressing Jade, I was beginning to feel I might have made a mistake.

“It’s a bit tight,” I said.

“Needs to be.” Ned gave me the board to hold, and they stood back to admire their work.

“He looks ready,” said Rag.

“He does.”

Again, I wondered what Jade would say. Maybe nothing, if she couldn’t get the words out for laughing. I put the board down, picked up my trousers and took out the notes. Rag couldn’t see how much was there, but he looked at the green and purple and licked his lips.

“You won’t tell Jade, will you? She’ll take the piss. I’ll tell her myself like … once I’m all right at it. Anyway, how much?” I said, swallowing. Rag pulled his gaze from the cash and looked at me square, serious.

“A hundred and fifty. And that includes the suit.”

“Oh, um, well how much just for the board?”

“Well…” He stroked his chin, considering the price… then cracked up. “I’m just messing. You think I’d sell you a suit I pissed in a thousand times?”

Ned put a hand on my shoulder.

“We’re giving you this stuff for free, but one day we may ask you a favour. Cool?”

“Cool,” I agreed, straight off, without thinking.

“I’ll ask you one more time,” said Rag. “You’re going to do this, Sam, for real?”

“Yes.” And I meant it. A grin spread across their faces. They stood back, looking me up and down, admiring what they’d made.

“You’re a surfer now, Sam,” said Rag. “One less of them…”

“…One more of us,” said Ned.

They did a comedy high-five.

(#ulink_3fe771ac-a189-5777-95a2-24df40a0428e)

MUM’S FACE WAS a right picture when I turned up with the board and suit.

There was a row. Course there was. But I was determined.

“It’s not safe,” she said.

“I’ll be careful.”

“Your father drowned at sea.”

“Mum, we live by the sea. On the edge of the moor. The edge of nowhere. There’s nothing else to do…”

Mum chewed her lip.

“Look,” I said. “If he’d died in a car crash, would you stop me learning to drive?”

“No.”

“But you’d want me to be careful, right? I’ll be careful. Safe. I promise.”

She gave in eventually, but only after I’d made a bunch of promises.

Never alone. I had to be with people who knew what they were doing.

Never when it was big or dangerous.

No going off surfing when I should be doing homework or helping in the house.

I reckon she thought I’d try it for a bit and then lose interest, as soon as I realised I wasn’t any good.

I told Mum the night before I started that I was meeting some surfers who were giving me a lesson before school. So that was broken promise number one.

I got up in the dark and sneaked downstairs. I’d laid it all out the night before: board, wetsuit, rash vest, towel, board wax, bananas and a flask of coffee for fuel. The whole thing had to run smooth. I had to be in the water super early, surf for an hour, race home, get changed and get to the bus stop in time. And then make it look to Jade like I’d just got up, before asking her if she’d been surfing. Just like every morning.

There was a chance I’d run into her at the beach, and if I did, I’d fess up. But if I could, I’d keep it a secret till I’d at least had a good crack at it. If she was surfing, she’d most likely be on the reefs, so with a bit of luck, she wouldn’t see me.

And what would she think if she did? What would she say? It was hard to guess.

All this went through my head as I cycled with the wetsuit half on, up to my waist, and the board under my arm. The bike was old and only had three gears, so I stayed in the middle one as I couldn’t change. I was wobbling and rolling like a drunk man, and how I got to the beach without falling off I have no idea. Jade had made it look easy.