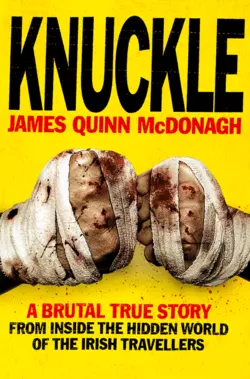

Knuckle

James Quinn McDonagh

When a simmering family feud between three clans of Irish travellers erupts after one member dies following a pub fight in London, the clans decide to go to war.Knuckle is the true story of James Quinn McDonagh – clan head and champion bare-knuckle fighter. It’s a journey from his grandfather’s horse-drawn caravan at the side of the road to the country lanes of Ireland where he stood, fists bloodied and bandaged, fighting a clan war that he never asked for.Two men, two neutral referees, a country lane. No gloves, no biting, no rests. The last man standing wins, takes home the money, and more importantly, the bragging rights.Caught in a brutal cycle of violence that has left men dead, houses burned and lives destroyed, James tells a story that opens up a hidden world – revealing why history repeats itself, and why he can never go home…‘A charismatic clan leader’- New York Times

Dedication (#ulink_0a755022-6fef-5a9a-80e5-2e5237202cad)

I would like to dedicate this book to my grandson,

James Quinn McDonagh

Contents

Cover (#ua9fbae32-72a9-5e91-ae7d-22251643f6c2)

Title Page (#u6609ce53-d09d-5a3a-9655-bded783d7bde)

Dedication

Prologue: Any Edge Is Worth Having

Chapter 1 - Born a Traveller

Chapter 2 - Boxing Gloves

Chapter 3 - England

Chapter 4 - The Beginning …

Chapter 5 - Nevins I: Ditsy Nevin

Chapter 6 - Nevins II: Chaps Patrick

Chapter 7 - Joyces I: Jody’s Joe Joyce

Chapter 8 - Joyces II: The Lurcher

Chapter 9 - The Night at the Spinning Wheel

Chapter 10 - Nevins III: Davey Nevin

Chapter 11 - The End …

Epilogue: The Traveller’s Life

Picture Section

Acknowledgments

Knuckle - The Film (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue (#ulink_4e941917-b01a-5792-b962-f8f1e08e0158)

ANY EDGE IS WORTH HAVING (#ulink_4e941917-b01a-5792-b962-f8f1e08e0158)

It was half-six in the morning when my eyes flicked open. Normally I would have been up half an hour already, into my clothes and out for a run. But with today being the day of the fight I wasn’t moving. All the exhausting weeks of training were now over – whatever else happened today, that was done with. An end to the jogging, weight-lifting, circuit training, the sparring that had gone on day after day for three months.

The last couple of weeks I had been winding down my training anyway, as I didn’t want to risk an injury in the days before the fight, but it was still a relief to think it was over. No more hitting bags for over an hour at a time. I could sleep a bit longer, I could eat what I wanted, and, what was more important, I could go out and enjoy myself again. I could drink what I wanted, when I wanted. No more sneaking out on a Sunday night to sink a few pints. No more setting out to jog on a Monday morning with a hangover, and turning up at the gym dripping wet – having cheated by getting a lift most of the way and pouring some water over my head just before I got there to make it look like I’d been sweating with the effort I’d put in.

Was I ready? I didn’t know. I’d done everything I could to be ready, but it was never easy. I was probably in the best shape I had ever been in. I had trained more intensively for this fight than any I had fought before. I was physically at my best and I knew that; I felt confident. I had my plans – I’d thought long and hard about how to fight, how I was going to act, and how I was going to beat him. I’d thought of what I might have to do if that didn’t work, so I had my back-up plan as well. I was prepared.

No one, though, is ever really ready for a fight like this. A man could go out and get a punch to the head that could kill him. Or he could kill someone. If I hit the man hard, like I planned to, but he slipped and fell, banged his head down on the ground – he could die. That would be with me for ever.

I lay in bed and said a few prayers. I blessed myself and prayed to God for my health, that of my wife and boys, and of my family. I said the Our Father and the Hail Mary. I prayed that the fight would go well, and that I would win. I guessed that I wasn’t the only one praying that day to win my fight but I thought, Lord, I didn’t ask for this fight, he did, so listen to me first.

You’ve got to try. Any edge is worth having.

Theresa stirred beside me and I said, ‘I’m going to go and get some milk and the papers,’ and got up and dressed. We were living in a settled house then, in a quiet area of Dundalk, in County Louth, and the shops were close by. Back home again, I started reading the papers over a cup of tea. I wasn’t trying to distract myself; I was calm, and relaxed. I knew I’d done everything I could to prepare for today and just had to wait till it was time to leave for the fight.

When a fight is called, each side will appoint their own referee from a neutral clan. It’s up to the two referees to see that fair play takes place, but before they start, the arrangements for the fight itself have to be sorted out. Both sides have to agree to the site of the fight, and the timing. Sometimes this can drag on, and then I’d know that the other side was messing with my head to get their edge over me.

I was going to be fighting Paddy Joyce – ‘the Lurcher’, he’d been nicknamed – around lunchtime. That was the idea anyway. The fight could have been delayed, though, so I needed to eat a meal that would last me through the day; I couldn’t be doing with getting hungry or tired at the wrong time. So instead of my usual breakfast I needed to get a decent meal in me now as it would most likely be the only food I’d get till the evening. I had put aside a sirloin steak in the fridge for the morning, along with some onions and a couple of eggs. That did fine.

About 9 a.m. my daddy, Jimmy Quinn, and my brothers Curly Paddy, Michael and Dave showed up. We had a cup of tea together, the four of them offering me encouragement all the time. Curly Paddy and Michael had been some of my sparring partners and they kept me focused on what I had to do later on. JJ, my son, had kept me company while I trained, and now he sat quietly with his uncles and Auld Jimmy while we talked. All the time, my phone didn’t stop ringing, people telling me they were coming down to support me, calling to wish me success, that sort of thing. I decided to make my way over to my uncle Thomas’s as I didn’t want the rest of the clan turning up on my doorstep. My neighbours had already complained about the number of cars parked around my home, some blocking their driveways, and my landlady had made it clear she didn’t much care for travellers. A hundred or so milling about outside my front door wouldn’t make me a popular man, but at my uncle Thomas’s site no one would care. Thomas didn’t really go in for the fighting himself, but he was happy to have us gather there and to see me off when it was time.

When I was ready to go I took Theresa to one side, told her I was going to win my fight, and promised to come back safely. ‘God bless you, James,’ she said, though she wasn’t happy I was fighting. She wanted me to win – ‘Up the Quinn McDonaghs!’ she’d say when I went off – but she wasn’t happy; she never had been. All the time I’d been training she’d been the one holding the family together; she always held the family together. ‘Take this and keep it with you,’ she said, and pressed into my hand a small laminated picture of a saint. Whenever I fought I’d receive these little gifts from the women in the family, my mother and aunts included. As I fought with no vest on I only had one place to slip these relics, as we called them, into, and that was my sock. By the time I left for my uncle’s site, I had five of them to fit in.

When we reached the site the clan had already started gathering. The Quinn McDonaghs all lived close by, our name marking out the triangle of land we thought of as home: from Dublin out west to Mullingar, up north to Dundalk and back south to Dublin again. There are Sligo McDonaghs, Mohan McDonaghs, Bumby McDonaghs, Galway McDonaghs, Mayo McDonaghs, even McDonaghs in England; but the Quinn McDonaghs are confined to that triangle of near enough fifty miles by fifty miles by fifty miles. At my uncle Thomas’s site, my uncles and cousins – dozens of them – were standing about waiting. One wore a white T-shirt printed with:

James

The Mightey

Quinn

Mc

Donagh

To pass the time they were playing a game of toss. I joined in, just to keep myself busy more than anything else. Heads and harps, we used to call it before the Euro came in. When I was 12 years old I’d see men out in Cara Park, in Dublin, tossing coins on a Thursday, when ‘the labour’ paid out in the morning. They’d lose all the money they’d just been given to feed their families for the rest of the week: forty, fifty pounds gone, just on the chance that the coin would keep coming up heads. They’d have three or four small kids and they’d have to go back to their wives and family with their dole gone, lost in the toss pit. They’d struggle on for the following week, and then go straight out to gamble again.

If the coin turned up harps, then the other guy would step in. I’ve seen men walk away from the toss pit with up to IR£800 in their hands. I’ve lost six hundred in an afternoon myself, all on the toss of a coin. I had a run of luck that day that didn’t help. It was at my brother Michael’s wedding, and I had to borrow two hundred from someone else just to have some spending money for the rest of the evening. I felt bad about that but it helped me when it came to a fight – I knew what it was like to lose money, and didn’t want to lose the purse. I knew how bad I felt after losing a few hundred, so how bad would it be if I was to lose ten, twenty, or even thirty grand?

I won a little bit and lost a little bit of money that day at the wedding. I didn’t take that as any kind of omen at all – it was just something that relaxed me. Playing toss meant I didn’t go into fight mode too early. Trying to get myself up too soon would just make me tense and tired. It was only when I was on my way to the fight that I’d get into character. That may sound funny, but it’s true. I’m not a violent man; to take up the challenge of these fights was something I did for our family name. The character the rival clans – the Joyces, the Nevins – thought I was, some kind of tough guy – they’d created that. I hadn’t. I had no interest in fighting other than defending the name of the Quinn McDonaghs, and winning that purse.

Soon there were well over a hundred people around me. The Quinn McDonaghs were out in force because I was fighting for our name and they’d come to support me. My uncle Chappy – one of the nicest people I know – came over, and he was riled up by the fight. He gripped my arm with his hand. ‘James, you listen to me. You see them people’ – he waved south, in the direction of where the fight would take place, and I nodded as he continued – ‘all them Joyces and all them Nevins. They’ve never beaten you. Now you’ve done your training, you know what you’re doing. Come back here and do not lose. I’m telling you straight: do not lose this, you make sure that you beat him, and if you beat him you’ve them all beat.’ That’s how much it meant to everyone, that even someone like Chappy could get worked up by the fight. If I beat the Lurcher, then, as Chappy told me, ‘That’s them people gone for ever.’ Big Joe Joyce had said the same to me when he called to arrange the day and time of the fight. ‘You’re fighting the best man of the Joyces. If you beat him, there’ll be no more. We’ll leave you alone,’ he’d said, although I didn’t think for a moment they would. The only hope I had of making sure they didn’t send for me again was if I really hurt the Lurcher. That might be the only way of stopping further fights.

I knew, too, what it would mean if I lost this fight. Then every Joyce and Nevin would be queuing up to take a shot at the Quinn McDonaghs. The other clans had pushed me up onto this place where I was their target, so if one of them managed to knock me down, then in their eyes they would have knocked down the whole Quinn McDonagh clan. To them that’s what this fight meant.

A reporter had shown up who’d heard about the fight and wanted to come and talk to me and then put some pictures of the fight in the paper. I told him why we were fighting. ‘There’s bad blood between the two families, and it’s been going on for years.’ My dad added, ‘Fifty years.’ The reporter also asked about the purse and if the fight was really about that. I smiled but explained that all that meant was ‘a few quid for Christmas too’.

What the reporter didn’t understand was that if I did win, I wasn’t winning £20,000. When we got the money at the end of the fight we’d first give each referee £500. And then I hadn’t put up £10,000 on my own; my family and I had gone to uncles and cousins and everyone would put in a little, a few hundred or maybe more. That way, if I lost, no one lost a lot of money, and if I won, then everyone would get a little share. Winning the fight wouldn’t make me a rich man, but I didn’t tell the reporter that.

The rest of my cousins and uncles then came over to offer me a few words of praise, encouragement and advice. Back-seat drivers, I call them; people with great beer guts who lived in the pub and had never trained in their lives telling me what to do, how to put myself about – and I was the one who’d put in about fourteen weeks’ training for this. So I smiled and thanked them but I didn’t really listen. Once I was standing there in front of Paddy the Lurcher, I’d be the only one who was there to fight him.

I didn’t know what sort of fighter he was going to be, because I’d never seen him fight, although he would have seen the videos of my fights. I didn’t even know what he looked like now, as I hadn’t seen him since the London days nearly fourteen years ago. I’d had some feedback from someone who’d seen him train, and the report said he’d bust the punch-bag hanging in Big Joe’s shed during training.

Hang on a second; how can you bust a punch-bag? Muhammad Ali didn’t bust a punch-bag. What bag was the Lurcher boxing now? A paper bag? A plastic bag? The man is an animal, I was told. He’s breaking the bags off the wall. You’re better off calling the fight off. Was this a game plan of the Joyces? I wondered. There was an awful lot of money riding on this fight and if I refused to fight him I’d lose it all. Was I being fed some line here? Was this meant to get back to me to upset me in my training?

That wasn’t for me to worry about; if anything, it inspired me to train harder. I kept a clear head; I’d fought before, and each time the fight had been out in the open air. This man hadn’t, and his record was one of bullying people, and all the tales I’d heard – of him beating this man, beating that – didn’t worry me because I had no way of knowing if they were people he knew he could beat before a fight, if they were no match for him. There were no tapes to watch, so they could have been what we call ‘fair fights’, or they might not have been. I wasn’t going to give him a chance, and I figured that if I kept my concentration, stuck to my plans, changed from one plan to another if necessary when I was fighting, I’d be OK. I knew I was fit enough.

When I was a kid growing up, I’d trained to be a boxer, I’d learned the basic moves. Left hand slightly out, right hand just above the chin, left leg out, back leg secure. From the age of 16, though, I had no training and the moves that I’d learned before I’d now refined into my own style. Come out, step forward, hit, step off. I’d sparred with people the Lurcher’s size, as far as I could tell, and I’d prepared myself to move quickly so he wouldn’t be able use his height and weight against me.

While I was fighting I’d keep my left arm out in front of me, feeling my way, my fist close to whoever I was fighting so my opponent couldn’t see me clearly enough. If he tried to slap my left arm away, the next minute my right would be sitting in his face. ‘The fishing pole’, the Joyces and the Nevins called it. They didn’t like it one bit. It disturbed my opponents, and broke their concentration. All my trainers when I was in boxing clubs as a young teenager told me not to use my left arm like that, but it was a tactic that always worked for me. I wasn’t going to change it, because it kept me at arm’s length from danger, I’d tell everyone. It was a shield to protect me. I could use it like a poker, jabbing at someone’s eye.

Ned Stokes, my referee, and two of his sons drove into the site about half-eleven. We shook hands. ‘I wish you luck, James. I hope it goes well for you,’ he said. I took a phone call off Paddy’s referee, Patrick McGinley, and relayed what he’d said to me to Ned: that we were meeting him and the Lurcher in a place down in Drogheda, about twenty miles to the south. To the cheers and applause of the waiting crowd, we got into Ned’s car, his sons in the one behind, and drove away.

From Dundalk it was just under half an hour’s drive on the M1. As he drove Ned Stokes talked about nothing in particular, a pleasant chat designed to take my mind off what the next couple of hours would bring. Once we came off the motorway and into Drogheda I had to find somewhere to wind myself up and get myself into fight mode. My phone would still have been ringing if I hadn’t switched it off. Having a moment to yourself is a rare thing for any traveller, and as for myself I found that there were some days when my house felt like Piccadilly Circus. I needed some time alone now. ‘Pull into this McDonald’s, will you, Ned,’ I said. ‘I need to use the toilet.’

Above the washbasins in the toilet was a mirror. I stared into it and spoke to myself. ‘This is your day, pal. Are you going to do it?’ I hadn’t planned to talk to myself, it just came to me at that moment. I thought of what those lads, my supporters, had been telling me to do; good things, advising me, encouraging me, telling me that the Lurcher was no good and that he couldn’t fight, and trying to get me worked up. But they weren’t here now, I told myself. I was the one who’d have to go out and fight for them all, for the Quinn McDonagh name. The weight of that lay heavily on my shoulders and on some days that pressure told on me, but today wasn’t one of those days. I was strong and fit and determined, and I wanted to go and fight Paddy. I wanted to hit him, to hurt him. To do that now meant I had to hate him. I remembered seeing him in London years ago, watching him bully people, and I focused on that as it helped me create that hatred. This was part of what I had to do – slipping into the role of James the fighter, James Quinn, son of Jimmy Quinn, a role I only have because it’s been forced on me.

It wasn’t hard to find reasons to hate Paddy Lurch; for the past few months I’d neglected so much of my life as I concentrated on this fight, what with the training and the dieting. If I didn’t work, I didn’t earn any money. I’d not spent time with my family. Instead I’d been in the gym, in that boxing ring, day after day for weeks on end. I’d not been to the pub to enjoy myself. I’d had to stop almost everything I was doing so that I could be ready for today. Paddy was the cause of that and the more I thought about what I’d had to stop and what I’d missed out on, the angrier I became. I wanted him to feel the pain that I’d felt for those endless weeks, the pain I’d felt in my muscles and joints as I trained, the aches I’d had those early mornings as I pulled myself out of bed to go jogging. I’d used every moment of the last few weeks to focus my anger on him. No spare time, no drink. No work, no money. All because of the Lurcher.

I needed to get angry because I had to stand in front of Paddy and try to hurt him. I had to be ready to cut his face, to cause him to get stitches under his eyes. Ready to knock him down, ready to give him concussion. Ready to disfigure him with a blow to the nose or the cheek. Ready to hit him hard enough on the head to give him a haemorrhage. Did I care? No. I hadn’t asked for this fight. He had. He was the one who’d made us do this, not me, and I used that to get myself more angry, to really start to hate the man and all those in his clan who’d put him up to fight me. We were here because of him, we were both risking our health and maybe even our lives because of him, and that made me angrier still.

A travelling man’s life is shorter than a settled man’s; the average life expectancy for a travelling man is sixty-seven years. That’s twenty years less than for a settled man. We Quinn McDonaghs have a high rate of heart disease and cancer; there’s heart problems in many of my uncles as well as my mother and father. So why was I adding to the problem by going out to maybe end this man’s life or maybe – if I took a blow in a bad way – my own? The anger boiled hotter.

Good. It was working. I looked into the mirror and repeated, ‘Today, James, you can do it.’

I had been provoked into this fight, and I had no choice but to win it. I had to succeed because if I didn’t hit him, hurt him, knock him down and keep him there, he’d do exactly that to me. I didn’t want to do this. I’m not someone who seeks fights; I’ve never looked for a scuffle in a pub on a Saturday night. I wasn’t proud that I was going to be doing this, I wasn’t happy; but this is what the fights were about. If I was going to win it was because I was ready to do everything I had to. I hated the Lurcher with a vengeance. I had to, otherwise I wasn’t going to win my fight. If I hadn’t hated him, I’d have felt sorry for him, I’d have felt pity – but I didn’t. I didn’t feel sorrow or pity, or compassion. I felt hatred. I wanted to get stuck in, hurt and maim that person. Hurting him badly would make another man think twice before challenging me, and that meant no more fights. So the hatred drove my aggression, and I needed that. That person has upset my whole life, I was thinking, and he’s getting me a name that I don’t like.

The name. It was all about the name.

I left the toilet and got back into the front car. While I’d been inside, Ned had taken the call telling us which location to go to, so with one of his sons in the car behind we set off again. The location was only five minutes away. I held my hands out to the lads in the back and they went to work, running bandages over my hands, thumbs and wrists.

As soon as we arrived at the site I wasn’t happy. I climbed out of the car and looked around but I knew we weren’t going to stay. There was nothing wrong with the place itself; it was the number of people already there to watch the fight I wasn’t pleased to see. I had deliberately left my family behind, and nobody had come with me except the referee, who was independent anyway, and his two sons; a cameraman, to tape the fight so that it could be seen by everyone back in Dundalk later on; and my second, who I needed to tie up my bandages. I’d expected Paddy Lurch to have the same around him too. Instead there was a gang of about fifteen or so there, hanging about waiting for the fight to start. I recognised some faces right away, people I’d fought in the past, Chaps Patrick, Ditsy Nevin, and a dozen or so other Nevins hanging around with them both. There is no doubt whose side they’d all be on when the fight started and I didn’t think that made it fair at all. No wonder Paddy Lurch had suggested this place for the fight. He might as well have said we’d fight at his house.

I got back into the car. ‘I ain’t fighting here,’ I said to Ned. He said, ‘Yes, the agreement we made was none of them people were coming to the fight, there was no other spectators.’ Patrick McGinley had come over to talk to Ned and had his head in through the driver’s window and he heard what Ned was saying. ‘That’s all right, James,’ Patrick said. ‘If you don’t want to fight here, then we won’t fight here.’

The Nevins didn’t like it when they saw me get back into the car. Chaps Patrick, though, came up and said, ‘Would you mind, James, if me and the lad come to the fight?’ He had his young son with him, a boy of about 7 or 8. Why he wanted to bring a kid to watch two men knock lumps out of each other I don’t know. ‘That’s all right, I don’t mind if you two come but’ – I pointed at the Nevins lined up alongside Ditsy – ‘I don’t want those others there.’

This set Ditsy off. Ned was turning the car round and Ditsy started yelling at me, ‘Get out and fucking fight, you cowardly fuck, yer. Get out and fight yer man here.’ I turned to Ned and said, ‘Now you see why I don’t want them there.’ Ned said, ‘James, I understand 100 per cent,’ and we drove away, Ditsy still gesturing and yelling at the car as we left him behind.

Ned drove to the end of a quiet back lane outside Drogheda, and the car with his boys and one with Chaps Patrick followed on. The bandages on my fists were tightened and checked by my second and I pulled off my sweatshirt and started to walk back up the lane to where we were going to fight. It was a grey November day, probably cold, but I didn’t notice, as I’d started to block out what was going on around me. I was narrowing my focus on the things that mattered now, because concentration would win me the fight. One moment when I was not looking at my opponent, where his fists were, what his feet were doing, and – most importantly – where his eyes were looking to, and it could all be over. I’d learned that; fighting someone, their eyes would look where they wanted to go to next, where they wanted to aim for, where they were planning to hit me. It never failed, this; I knew I had a moment to strike back before they could hit me if their eyes led the way. I never took my gaze off my opponent’s face; if I had to hit him on his chin, I knew it was somewhere below his eyes and nose. I didn’t need to look to know that.

At this point I still hadn’t seen the Lurch. Ahead I could see a couple of cars pull up and stop, and a guy got out of one of them. I knew that Paddy was a red-haired feller, big, and I believed a little slow in his movements; but this man was rolling his shoulders, stretching out his neck, shaping himself in a way that I hadn’t expected – someone who knew what he was about. I asked Ned, ‘Is that Paddy Lurch? Is that the Lurch, Ned?’ ‘No,’ he said, looking over at the man. ‘That’s young Maguire.’ I didn’t even know what the Lurch looked like and I was about to fight him.

Then he stepped out of McGinley’s car and there was no doubt this was him. He was as big as me, in tracksuit bottoms and a red vest, and bandages on his hands. I nodded over and he nodded back at me, the courtesy of a head wave but no more. The two referees came over to check my bandages – to make sure I’d nothing tied under the bandages that would make a punch more painful – and were happy enough with them. Then they called the Lurcher, still wearing his red vest, over and we listened while Ned ran over the rules. ‘The agreement is, if a man is down he gets up. Arms round each other is a foul, but when you’re in tight, no man can stop it. No fouling, no dirty punches. If you break, you break clean.’

The Lurch pulled off his vest and said, ‘There’s one thing I want to say, James: your brother Paddy’s the cause of all of this.’

‘Lurch, there’s no need for this,’ I told him. ‘You shouldn’t have sent for me, you should have sent for Paddy.’

‘I don’t send for murderers,’ he replied. The fight hadn’t started and he was goading me. I started to answer back but Ned broke in.

‘Excuse me, boys,’ he said, talking over us both. ‘No bad language, boys.’

‘No biting, no holding, no head-butting,’ added Patrick McGinley. ‘Now shake hands.’

‘No,’ Paddy said immediately, and I retorted, ‘No, no shaking hands.’

The referees stepped back.

I moved forward, hopping from foot to foot, my left arm in front of me, right curled back, ready to land the first blow.

Chapter 1 (#ulink_032faf90-80e5-5e4c-b4b3-00c497f9fe99)

BORN A TRAVELLER (#ulink_032faf90-80e5-5e4c-b4b3-00c497f9fe99)

Growing up, this fighting thing never came into my mind. I never thought either about being a policeman, being a solicitor, being a fireman – none of those. I was a traveller, and they weren’t things that I would even have thought of doing with my life. I would do what travellers did. That was the only path open to me.

I was born in County Westmeath in 1967. For my first few years I lived with my grandfather, Auld Daddy, my mother, older brother Curly Paddy and older sister Bridgie, all of us in an old-fashioned barrel-top wagon, the kind pulled by horses. The main bed was inside at the back of the wagon, and there was a little stove to keep us warm and a box for the bread. To keep me safe when I was a baby while he slept, my grandfather would loop a bit of rope around my middle and tie the other end around his ankle. If I tried to crawl off, the rope would tug and he’d wake up.

Auld Daddy had two horses, one to tow the wagon, the other to breed from, so we could sell the foals. We wouldn’t sleep in the wagon, not us kids anyway; we would sleep under the wagon, or at the side of the road in a ‘tent’ made of branches from the hedges. The dogs would sleep anywhere they could; they weren’t pets, they were working dogs. My mother would cook on an open fire, and she’d wash our clothes with water from the river. In the summertime, when it was warm, we’d sit by the fire and we’d sing songs and be told stories of Irish myths from many years ago. The story-teller, usually Auld Daddy, would tell us ghost stories about the banshees, to frighten us off to bed.

We’d sleep in the tent, in straw that the farmer would give us when we arrived. My mother would shake it all up, spread the blanket out, and I’d climb in. I’d wrap the blanket round me and as I sank into the straw it would just fall around me. It was like a big quilt, nice and warm on a cold night.

To an outsider it might have looked romantic, a simple life like that, but it wasn’t, it was very hard. In the summer it might have looked the same as a nice camping trip but if you go camping you only go for a few days and then come home, whereas we were living like that all year round. In the winter it was a very harsh life. Rural Ireland was poor then and travellers were the poorest of the poor. In those days travellers lived off the land, making things like clothes pegs that could be sold door to door and at the markets, and from the seasonal work farmers would give them, such as picking spuds in the autumn. We had to beg for clothes from the local families, the settled people. We had no other way of getting basics of that sort.

I was born when my father was in England. He’d travelled over there for work, got mixed up in some trouble, and ended up in prison. If years back a man was in jail or away working, his wife would go back to her family, so my mother went back to her father, and he looked after her. The first time my father saw me I was 2½ years old.

My father was Jimmy Quinn, son of Mikey Quinn. Those names go through the generations: I’m James Quinn, it’s my son’s name, and my grandson’s name, and before Mikey came Martin, and before him was Mickey McDonagh. Mickey married a woman called Judy Caffrey and together they had five sons and five daughters. Mickey’s mother was one of three sisters known as ‘the Long Tails’ for the dresses they wore. All these names I grew up with around the fire; there was nothing written down about our family and stories like those, about these memorable dresses, only survive because they were passed on. Travellers’ lives were mostly just hidden away in history. Mickey’s son Martin was my great-grandfather and he went on to have five sons as well. His wife was a Joyce, Winnie Joyce, and her brother Patsy married Martin’s sister, linking the Joyces and the Quinn McDonaghs together right through to this day. One of my grandfather’s brothers also had several children, among them Padnin Quinn, Davey ‘Minor Charge’ Quinn, and Cowboy Quinn – and my mother. The Nevins also married into the family back in those generations – so we’re all related, even if we do feud with each other.

There is a Quinn connection going back a long way, even though we’re the Quinn McDonaghs. I never knew why we always made such a thing of the ‘Quinn’ part and didn’t really pay much attention to the ‘McDonagh’ bit, but I was told two versions of the story when I was growing up. Both involve Mickey McDonagh coming back into a camp, chased by the police. One version says it was because he was running from them after stealing something, the other says it was because he didn’t want to be conscripted into the British Army for the First World War. Either way, when the police came into the camp and discovered there were five Michael McDonaghs on the site, he was asked, ‘Are you Mickey McDonagh?’, to which he said ‘Me? No, I’m Michael Quinn,’ taking his mother’s maiden name (Abigail Quinn was another of the Long Tail sisters), and from then on the Quinn McDonagh name was used.

My uncle Michael was known as Chappy; my uncle Martin was known as Buck; my uncle Kieran was known as Johnny Boy. Most of the time I never knew why some people had the nicknames they had, but even as children we all knew why my father’s cousin Bullstail Collins was called Bullstail and not Martin Collins. One day he was standing by a farmer’s gate and the bull in the field was scratching his arse against the fence. Martin Collins decided to tie his tail onto the gate and hit him with the stick. The bull went and the tail stayed – and that’s why he’s always known as Bullstail.

When I was growing up my dad travelled with his family round the area of Ireland we lived in, and when I was a little boy I loved to hear their stories. My father grew up with seven brothers and five sisters, and with all those mouths to feed everyone had to contribute. (Large families were a feature of traveller life, and my sister married a man with twenty-two brothers and sisters. My own wife Theresa has seventeen uncles and aunts.) In the 1940s and 1950s life on the roads was very, very rough, and my father used to say if it hadn’t been for the farmers the travelling people of Ireland wouldn’t have survived. The farmers gave them work and – when they were able to – donations of food and clothing as well. My father’s family lived off what they could earn and what they were given.

One of the stories we all heard when growing up was about the Christmastime when my father went out, with two of his older sisters, to see if they could get him some shoes. He was only 3½ years old. ‘I was walking out with nothing on my bare feet, in the snow,’ he’d say, and we’d all try to imagine how cold that must have been. His childhood had gone quickly and by the age of 11 he was in the fields with his family picking spuds from August through to the winter. ‘The first day’s wages I ever got,’ he’d tell us as we sat by the crackling fire, ‘was a half a crown for walking with a plough over at Carnaross, County Meath, and that’s back in the 1950s.’ He would describe his battle with the heavy plough and the thick, heavy soil. With his wages he bought a beer but he’d always make sure we knew that he’d ‘given my mother a shilling’.

The family would eat what they could find, and share what they had with whoever was around them. My father loved to tell us about the time he and his brother Buck went out and gathered some spuds and carrots from the field, which they gave to their mother to put in her large pot (as children we all feared the witches’ pot, as we called it). Then they went out and caught a couple of rabbits and a hare, and then managed to catch a duck in a local pond, and – and this was the risky thing – a pheasant too. All of these went into the pot with whatever else my granny could find and their family, and the five families around them, feasted on that for dinner. As children we couldn’t understand how anyone could eat all of those things at one time, but I suppose if you’re very hungry, as they all were, you wouldn’t care. Certainly my father remembered the entire pot being emptied that night.

Just as we were told how good and kind the farmers and their families were in those days, we’d also be reminded of what could happen if we weren’t respectful of them in return. When my father was young, his uncle was out in Galway somewhere and had a confrontation with the farmer beside whose land he was staying. The farmer accused him of raiding the hedges for timber to keep his fire going and my father’s uncle denied this, saying he’d scavenged the timber from where it had fallen on the side of the road. He stood up to talk to the farmer, and the farmer claimed he saw him pulling out an iron bar and thought he was going to hit him, so he produced a gun and blew my dad’s uncle’s head off. Killed him like that, over his own fire by the side of the road. The farmer was taken to court about it but he claimed he’d shot him in self-defence and no one disagreed with him. So we were told always to mind what the farmer told us and not to think we could do as we liked. That story was often repeated to us to remind us that the law didn’t always look too favourably on travellers and so we should be careful not to come into contact with the police if we could help it.

There were times when we relied on the Guards – what travellers called the Garda, the Irish Police. In my father’s young days no traveller had a telephone – just as we didn’t when I was young, of course – so if there was a death, or another reason to need to meet up with another family, then it was the Guards who would pass on a message. A traveller would go into the local Garda office and ask them to pass on a message to the Quinn McDonaghs up in Meath. The Garda would then ring some local stations and ask if we were known to be in the area, and if so, could an officer go out and find the family and carry a message to them? Usually the Guards would know who was in their area and roughly where they were, so it wouldn’t take them long to find whoever they were looking for.

The story we liked best was the one about my father meeting my mother for the first time, in 1963. He was back in Ireland, home from work in England. In the 1950s and the early 1960s many travelling men left Ireland and went to Manchester. They had heard there was work to be had there; on the side of the roads there was work in the Irish construction companies. Names like McGinley, McAlpine, you name it, my father worked for them all. Back home on holiday, he was on a bike, heading down to the water pump, when he happened upon this girl on her way to fetch some milk. At this point in the story my mother would interrupt. There was no accident about it, she’d declare; he knew where she’d be and he’d ridden down there to the pump deliberately, in the hope of seeing her. That she was related to him made the meeting easier, as there wasn’t much mixing with other clans when they travelled. People mostly stuck to themselves. It was usually only at arranged events, like the horse fairs, that boys and girls would get a chance to see each other and talk. That, and family get-togethers such as weddings.

I was born on a Tuesday in hospital and christened the following Sunday, 23 July, in the Cathedral of Christ the King in Mullingar, County Westmeath. (Years later I was married there.) My father was by then in prison in England – there was a stabbing incident in a pub and he was put inside for three years – and I was brought up by my mother and my grandfather. My mother told me many years later that she found it hard going, raising the three of us boys without her husband there. She’d go door to door looking for hand-me-downs, trying to make the money she had been given last a week. The relieving officer would give her money or sometimes a voucher to exchange for food. His title was shortened to ‘leaving officer’ and the one I can remember my mother mentioning was called Mr Scally. He was nice to us and if we were out on the road he’d come past in his car, pull over, and come out with the money or the voucher for us. No more than four or five pounds, it wasn’t much, but it helped.

Eventually my father was released and he came straight over to see us. Well, not exactly straight; he went to meet my mother’s brother to find where we were and the two of them – drinking companions from their young days – went out to celebrate his release that night. This is what travelling men do, so I suppose it’s no surprise that the following morning they did it all over again, and it wasn’t until much later that day that my father finally laid eyes on the son he’d not yet seen.

‘What do you remember about seeing me for the first time, Daddy?’ I asked my father once. He thought for a moment or two. ‘You was in bed, and you were a big lump of a boy,’ he said, which wasn’t exactly the touching memory I’d hoped to hear.

The very next morning my father saddled up the horses, which up until then my mother had looked after, and we set off, leaving Auld Daddy behind. There was no time to waste. Having no one he could turn to for help, my father needed to earn some money as quickly as he could. For the next few years we lived on the side of the road, although when my father first came back we moved about a fair bit. Maybe he was restless after being locked up in England, I don’t know, but every three weeks or so we would dismantle the tent, harness the horse up, and get out on the road looking for somewhere new where we might get some work. We would only go ten or fifteen miles down the road, because that distance was enough for the horse pulling a wagon. It was a big thing for my father too, because he’d have to rebuild the tent as well. Having the horse was all very well, but my father couldn’t do much with it. Besides, he’d seen what other travelling men could do with their trucks in England, so, soon after returning home, he bought a van for his work. He’d haul scrap in it, or put it to any use he could, to earn some money.

When we stopped for the night, the first thing my father would do was make the tent, one that would last us as long as we needed to stay put. My brother Paddy and I would be running alongside him, helping to carry the wood. The first job was to cut down the poles that would form the frame, and here hazel wood was the best as it was the easiest to get into place. A long pole would be trimmed of its bark and stuck into a bank. That would hold one end firmly while we watched my father bend the other end over and force it into the ground, making the main stay of the frame – and somewhere to hang things off the floor. This was called the rigging pole. He’d then strip smaller poles until there were enough to start weaving the wattles, as we called them, to form the canopy. Knowing there was now someone living there, the farmer might come by and give us some straw to put inside to make us more comfortable. To finish off the tent, my father would dig a trench around the sides to take away the rainwater. A tent like this could last all winter if it was properly made.

When I was a little older, Paddy and I would have our duties. I would have to get the sticks for the fire in the mornings, and Paddy had to get the water to drink and cook with. The following day I would fetch the water, while Paddy would have to go root in the farmers’ hedges for wood for the fire. Doing this meant we learned the layout of the land and all the little places where we could catch our food. My favourite was snaring rabbits. I’d be happy spending time getting my snares ready, waiting to catch some. I’d go down with a set of snares in the evenings and be there for three or four hours. Then, in the morning, I’d go round and check the snares, take the rabbit out if I’d caught one, club it, and carry it home. Sometimes of an evening I’d take the dogs up with me to chase rabbits out of the hedges. I’d send in the little terrier, he’d flush the rabbits out into the open, and the greyhound would race over and pick them up. My father would skin the rabbit (we didn’t sell the fur) and gut it and clean it up and my mother would put it in the pan with a few vegetables and boil the whole lot, and that was a lovely dinner.

To get vegetables I would sometimes raid farmers’ fields. Of course the farmers would warn us never to steal from them, but I had found a way to take what we needed without being caught. I’d go into the centre of the field where the farmer wouldn’t notice anything missing, rather than at the edges where it was obvious, and I’d lift out a few vegetables – just enough for the pot that night. When I brought whatever I’d collected home, no one said to me, ‘Where did you get them from?’ So as long as it wasn’t necessary, then no questions would be asked.

I was very proud of helping to feed my family, and I brought my first rabbit back when I was only 7. The dogs helped me; we had three, all called Jack. We had Auld Jack, who was the boss. When he was 16 we had to get him put down because a weasel blinded him. Then we had young Jack, his son; he was half bulldog, half terrier, and we had him for ten years, until he was killed by a car. We had greyhound Jack and then later on we had a little Jack Russell. All the dogs were there for hunting rabbits and hares. Hare hunting was something I never liked. I don’t really know why; whether it was because it involved a lot of running about, or because of the stories we were told round the fire when I was little. I never liked the tales that had me laying awake in bed. One was about some boys who were chasing a hare with their dog, only for the hare to turn into a banshee and kill their dog. Or there was the story where the boys were following a hare and it went out of their sight and turned into an old woman. That one also reminded me of the tale we were told of the little girls who were turned into swans by their stepmother. Some of those stories had a purpose. For instance, we were told never to throw stones at swans – ducks we could chuck stones at, and if we were lucky enough to hit and kill one we could take it home to eat – but never a swan, because of the law.

It was an essential part of a travelling man’s life to have a dog and I liked our three – Auld Jack, young Jack and Greyhound Jack – very much. They worked as a team and my father had them together for over twelve years; he always kept dogs rather than bitches, because he wasn’t into the hassle of breeding from them. They were pets to us children but their purpose first and foremost was to hunt – they were as essential to our hunting as a fishing rod is to a fisherman. (Talking of fishing, eel rolled in pastry and fried was my favourite dish of all.) The dogs weren’t allowed inside the tent, where we slept. They were rough and ready dogs, and had to fend for themselves outside.

When the older boys and the men went out hare coursing I’d try to hang back. It just never seemed to interest me, so I didn’t even try to get to like it. The greyhounds were essential for this, because they were the only ones with the speed. They were used for pheasants as well, although we always had to be careful not to take the farmers’ birds.

We were careful always not to upset the farmers, because without their help things could be very tough for us. When we left a site we would always clear up properly, because if we didn’t, then we’d never be welcome there again. We’d go round the site and bag up any rubbish so there was no sign that we’d been there. It wasn’t in our interests to leave it untidy at all, because we’d probably come back that way in four or five months’ time and want to feel the farmer was friendly towards us. There would be times when we’d arrive at a site and find it left dirty by someone else – usually someone who’d come from outside our area to use it and so not likely to have to return there. Then we’d end up clearing away their mess.

Whenever a site had been left in a mess, I would feel some prejudice towards us when we arrived. Sometimes when we turned up the farmer – or even the police – would come along and say to us, don’t stay there tonight. We knew that if we ignored that advice the likelihood was that a few bricks would be hurled our way later on, that the van windows would be broken. Obviously the family that had stayed there before us had caused trouble, and that hadn’t been forgotten. It made no difference if we said we’d not take anything we weren’t offered and clear up after ourselves: we were classed the same as the troublemakers. We would have to move on down the road a little bit. Luckily, other farmers would be on the side of the road, and accept us with open arms. They’d give us milk and water, they’d give out straw for the tent, they’d give us all a bit of farm work. It seemed to me that if we behaved like my mother and father – and the older generation – and treated the farmers and their workers with respect, we would probably be given it in return. But because of the behaviour of a few that didn’t show them respect, at times we were all treated as one and no longer welcomed where we’d been able to stop before.

Eventually we stopped travelling in a wagon. In 1971 my father bought a caravan to pull on the back of the van. Having the caravan was a big thing for us; we were on the move as my father hunted work, and all went where he had to go. But now we had moved from a tent to a caravan at the side of the road, it was all so different. Like moving from a one-bedroom apartment into a penthouse. We even had a gas cooker in there. My father and mother had the caravan for themselves and the girls. Paddy, me and my younger brother Dave had a bed made for us on a mattress in the back of the van. We’d happily sleep in the back of the van; for us it was like going camping, and it felt like a break from what we’d been used to.

Everything we did in our spare time, we had to provide ourselves, whereas nowadays kids all have video games and things like that. We’d be out all day picking spuds from 6 a.m. until about four in the afternoon. Then straight away we’d have something to eat at home before running outside to play games: football, handball, kick the can – you name it. Even though we’d been working all day, we never felt too tired to play.

A couple of years later another change came that was even more exciting – we moved into a place in Mullingar, where I can remember my mother coming home from the hospital with my sister Maggie. It was a rough area, so bad that much of it has been demolished now, but we were there for a year or so before we moved south to Dublin, where we lived for a short while in Coolock, in the north-east of the city. We never stayed anywhere long enough for me to make friends or even to get to know anyone really.

Nineteen seventy-six was a blistering summer and we stayed right next to the beach for the entire summer. I spent the whole time outdoors, all day in that heat, swimming whenever we could. We had great times there. As well as my family, Chappy was there with all his kids, so we played every kind of game we could out on the beach. We stayed there right through till it was time to move on to start the potato-picking season in County Meath.

Family life was very good. My mother and father were very good to us; they were never too strict and always tried to give us whatever they could afford. They had no education, and so for us those early years were about survival. If my parents could afford a pair of Wellingtons or a pair of shoes or other clothing for us, they’d get them for us. Like every other travelling woman in Ireland in the 1970s, my mother went from door to door knocking for handouts and old clothes, and a lot of those clothes ended up on my back and on the backs of others in the family. That was true for 99 per cent of travelling families throughout Ireland in those years. But even though things were so bad, as a child I wasn’t aware of it. As long as we had food I didn’t mind how we lived.

From when I was 9 or 10 we were out doing a lot of farm work all over County Dublin, County Louth and County Westmeath. We’d pick potatoes, sprouts, sugar beet – anything the farmers had planted we’d be there to help harvest. I don’t remember liking the work but I certainly didn’t hate it. Working hard was something that we were just brought up to believe in doing, just as we believed God is God. Work wasn’t something that we had to be taught; we knew it almost from our very first breath. We believed that it had to be done, and everyone pitched in to make it easier for the family. For example, my mother didn’t just look after all of us, but worked too, selling things at a flea market, the Hill Market in Dublin, on a Saturday.

The time came when my father started thinking how much easier he’d found it to get work in England in the early 1960s. So he went back over to Manchester and when I was 10 we all followed him over. He had also told my mother about how we could get a house over there, and how there were many travelling families – the Joyces, Keenans and Wards – there too. It was so different – I’d never seen a coloured person before, for instance – but living was not a whole lot easier then. The better times had long gone and it was a lot harder to get work than my father had expected. He found work on building sites but having his family with him made the experience harder this time. People were prejudiced against us, although not because we were travellers – we were just Irish to them. There were some who’d call us ‘tinkers’, which never bothered me much as I didn’t really know what it meant, but I was happy when we returned to Ireland. My father sold the van and bought a truck and a car. As he was the only driver, he’d put the car on the back of the truck and hook the caravan on the back of the truck, and set off like that along the roads around Dundalk again.

People in Ireland, I learned, could often be just as prejudiced as the English. We met so few other children from outside the traveller families – mainly the farmers’ children who came to see us when we moved onto a site – so we kept very much to ourselves. Not long after moving back from England my father bought a new caravan – well, new to us anyway – and it had a battery in it that could power a little 12-volt black and white television. Sitting in the trailer watching TV by the side of the road was a great thing.

I was happy going back out on the road. Lots of the sites were familiar to me and I knew where to find little hiding places and where to make dens for myself. I never thought life would change; the most my family ever wanted was a nicer car, a nicer caravan. We’d put up somewhere for the winter and be joined by other families who, like us, would travel the roads during the warmer months but rest up for the colder ones. I liked to see new faces, as much as I loved my family I could also get a little sick of the same old thing every day. Even though I had three brothers and three sisters and we all got on like a house on fire, it was still great when someone new to us was nearby. I loved to see someone different pull in beside us, strangers who might be part of the clan but still people we hadn’t seen for months. For me the great thing was that our games could be more involved because there were more youngsters joining in.

Come the spring the three or four families would each go their separate ways, and we’d move about, never sure who we’d find ourselves alongside for the night. In those days there was never any trouble between the clans; we were always careful, but the times were easier. It was only when travellers started to give up the travelling life that everything started to get more difficult. That began to happen at the end of the 1970s, when the recession hit and there was little or no work, and the only money my family had coming in was the social security. The lack of work hit everyone, not just travellers.

In 1979 I went to the horse fair at Ballinasloe, over in County Galway, with my father; it was a great experience for me but he didn’t enjoy it. My father was the kind of a man who never liked trouble, but there was always trouble at the fairs, so he avoided them if he could. As soon as we saw some fellows picking on each other, trying to provoke a fight, he said, ‘Right, Jimmy, we’re off,’ and that was it. I’ve never been to a horse fair since.

Chapter 2 (#ulink_8d28481c-c7a7-5506-8aea-ce5e182c0d9a)

BOXING GLOVES (#ulink_8d28481c-c7a7-5506-8aea-ce5e182c0d9a)

One thing that never really featured highly in my childhood was school. Like most traveller children, what I needed to learn I learned from my father out in the fields and hedgerows. The only point of going to school, as far as travellers were concerned, was to prepare a child for their Holy Communion and Confirmation by learning about religion.

My first school was the primary school in Mullingar run by the Christian Brothers. Travellers weren’t well looked after in school and I discovered it was no different at the one I attended. In the last few years the Christian Brothers’ schools have come in for criticism and I’m right behind what has been said about them. Our teacher, Brother Reagan, was a priest, and what he used to do to the small children in his class was not at all nice. He had a thick black strap, what we called the black taffy, and if he felt you needed it, he’d make you stick out your hand and would whack you hard with it. He would do this to kids as young as 6 years old. We never learned anything from him; we just feared and hated him. Traveller children weren’t expected to learn; we were simply a nuisance as far as Brother Reagan was concerned and he just wanted us to keep quiet and not bother him. We were never sure of what rules he had, so often we’d get the taffy across our hands for what seemed like nothing at all.

I was taken out of the Christian Brothers’ school and sent to the convent school next door. My class was taught by a nun called Sister Mary. She was a saint by comparison with Brother Reagan, but she was as well the loveliest nun I’ve ever met. All the bad feelings I’d started to have about religious people changed completely when I was in her class. Where Brother Reagan was fierce and angry, Sister Mary was very pleasant, and I felt protected by her. Yet I still didn’t learn much with her, always looking forward to being out of the classroom playing.

The school playground was full with my cousins as well as my younger brothers and sisters. One of our cousins, Theresa, was in the class below mine. I didn’t see her again until ten years later on, at my brother’s wedding – and I had to be reminded who she was. Within a few days of that meeting she’d agreed to marry me.

When I’d been at the school for a while I was moved up into the next class and I stopped learning altogether. But my experience wasn’t quite as bad as my brother Paddy’s. He and several cousins, boys from the Joyces and Nevins, as well as our cousin Sammy, all roughly the same age, were put into a pre-fab building by themselves at their school. There were no desks, just a few chairs for them to sit on. ‘Here you go, lads,’ said the teacher, handing them a pack of cards. ‘Keep quiet till break time.’ That was their education, five days a week. On other days, they’d be led into the playground when they arrived in the morning and told to get on with kicking a ball about, but not to make too much noise or they’d disturb the children from settled families, who were all in class learning.

That I never learned much at school wasn’t just down to my being ignored by the teachers, or not caring; it was also because I never stayed in one school long enough. When I’d been at the school in Mullingar for a while, my father came home one night and with absolutely no warning said, ‘I’m moving us to Dundalk.’ We moved the very next day and after we’d settled into our site I was taken into a school in Dundalk, another school run by the Christian Brothers, but much better than the one in Mullingar. No one chased us to find out why I wasn’t at school; the school I had been at had no contact with us, as we had no phone and no forwarding address. No one came round to the site to see if there were any children who should be at school; the system wasn’t interested in forcing traveller children to attend school. Why should it be? We weren’t going to be doing anything with what we learned; we would be out in the fields long before the other children would be just starting to study for their exams. Travellers wouldn’t use what they might have learned because they didn’t get jobs that needed an education. That was the attitude people had then. Maybe the authorities also knew that the reason I was going to school was for what I would be given – free uniform and free shoes.

All I could tell my new teachers about what I’d learned was where I went to school and what class I had been in. I couldn’t remember what I’d learned and I still couldn’t read or write, so whenever I started a new school I was always put into the first class. They never asked me, who was your teacher, how far did you go through the school? Whatever picture books I’d been given were gone, left behind, and that was one of the main reasons my reading and writing never improved. No one at the school ever tried – as far as I know – to contact the previous schools to see what records about me they had. The teachers at each new school seemed to think it was ‘easier if we start again, James’. Which meant I never made any progress.

The time that most upset me was when I was taken aside at school and asked about my family. I didn’t know what the teacher was getting at until she used the word ‘adopted’. I couldn’t work out why, but it was because my father called himself Jimmy Quinn and the teachers had my name down as James McDonagh. I didn’t know this at the time because nobody explained things like that to me, and I was left to puzzle it out for myself.

We moved again, this time south. I was put in a school, in the middle of Cara Park, a traveller site in Coolock, where there were a few pre-fab buildings in the centre. One of these little units was a school for travellers, and us young lads went there. There were about six or seven of us of the same age going through the last stage of school at the same time, and this is where the one thing that did change things for me came about. The school at least showed some interest in getting me through my religious education, and a little nun educated me for my Confirmation. Sister Clare gave me all the prayers I needed and told me how to respond to the questions I was asked.

The day came for my Confirmation, and that day I wore a blazer. My father and mother were there, watching proudly, as were other traveller families because others were confirmed at the same time. One of them was my friend Turkey’s Paddy; we’d got on famously since we’d met. Not long afterwards his family moved on to Newry and he went swimming in a river and drowned. Turkey’s Paddy was buried in Dundalk. His mother, Maggie, came over to me at the funeral and said, ‘James, you and Paddy will never play together again,’ and I cried. I was still only a child and I’d never before experienced losing someone that close to me. I just didn’t know what that meant until the moment Turkey’s Paddy’s mother spoke to me at the funeral. She knew how close the two of us had been, and as a token of that, when she had her next child she called him James.

As soon as I could after I was confirmed, I left school, and we went away and travelled. As a travelling family was mostly moving around in the summer and working in the fields in the autumn, there wasn’t a lot of time for me to go to school anyway. I left school at 12. I’d never liked it.

My mother had only sent me to school to be prepared for my Confirmation, and once that was finished she didn’t care any more about my education. People care now. As a parent now myself I have very different feelings about education. The times have changed and what was considered OK then would not be allowed now. Back then, traveller kids were considered second class, second rate, and it didn’t interest those in charge that we weren’t getting an education. Travellers are no longer left behind and ignored in classes; in some schools, like the one my sons went to in Dundalk, there are classes just for travellers. Some see this as special treatment but I don’t, because I think traveller children have a long way to go to catch up with settled children, who are used to the idea of school, expect it, and welcome it. It will take a long time for education to become a habit for all traveller families. You can’t make that happen just by wanting it; you have to change the way everybody else thinks about it too, and that is a long-term project.

In later life I taught myself to read and write, but as a young boy the only thing I liked about school was learning about religion. All traveller families are religious, some more than others perhaps, but they all believe in God. Some may be sarcastic about it, they may do wrong, but they also believe in Holy Mother Mary and in Jesus Christ. That has never left me; as an adult I have even been on pilgrimages overseas, to Fatima in Portugal, for instance. A lot of travellers go to Lourdes. I try to attend Mass every Sunday. I believe in Heaven – that when someone has been good they will go there – and I believe in Hell. I believe in a lot of angels. The Holy Trinity is tattooed on my back. Religion is probably the most important constant in traveller life, and all families bring their children up to believe in God and to go to Mass. A newborn child must be christened, because travellers believe that a child doesn’t prosper or improve until they get that original sin taken away from them by being baptised into the Church. We pray for those who have died, we pray for their souls, we pray for each other. My wife is a very religious person. Theresa will say the Rosary every day and she will never miss Mass. She’ll walk five or even ten miles to attend.

Although I’d left school I was still unable to go and join my father in his work – I was too young – so instead I had to work at a training centre for young travelling kids. AnCo was the name of the organisation, and they would teach me a skill that would enable me to become an apprentice in a job. I chose carpentry but it was never really my thing. I did it for a while, mostly because I was paid £30.30 a week to stay on there at AnCo.

The first week I had that money in my hands I went out to spend it right away. When we were doing the farming work, all we ever got was pocket money because all that we were earning was needed to keep the home going. It meant so much to me to have my own money to spend at last. I knew what I wanted to buy first: a bike. That way I could get out, go anywhere I wanted. The second week, I bought a tape deck so I could listen to music. The third week, I bought some clothes: Shakin’ Stevens was big then with his hit ‘This Ole House’ and I bought some clothes like his. White trainers, tight jeans, a Levi jacket, black shirt, white tie: that was Shakin’ Stevens’s look on his album cover and I got it. But it wasn’t a Shakin’ Stevens record I bought first; it was Rod Stewart’s ‘Baby Jane’. I liked Rod, still do, and country and western too, and we’d dance to the records at the teenage disco that was held on the site once a week. I was happy with what I was doing: I was earning some money, I spent Friday nights at the disco, and the rest of the weekend hunting. And I went boxing.

I’d started boxing for two reasons. The first was that I hated being pushed around by other kids, and from a young age found myself bullied. Certain settled kids in Mullingar were bullies; they were a clan of their own, and a little gang of them would go about the place trying to find someone to pick on. They’d never value anything we said or did. That has all changed since those days, and when my sons were at school they learned that settled kids often look up to traveller kids. But it wasn’t like that when I was young. If a game of football or of handball was going on, I’d go to join in and these kids – who weren’t playing themselves – would stop me, push me off the field, and hit me. If they were playing and it was our turn to play, they’d push me away, kick me up the arse, shove me, slap me on the head. They would hit me hard enough to make me cry, and crying is embarrassing when you’re that age. No one would stop them because they knew that they’d get the same thing if they tried.

It wasn’t just settled kids who were the problem. I remember one time at Cara Park, I was playing with two friends on the roof of a pre-fab. Another kid came along, older than us but shorter, and told us to stay up there or he’d punch us. We were that petrified of him that we stayed up there on the roof even when he went away, and only crept down when it got to about two in the morning. There we were, the three of us, all taller than him, and we still wouldn’t come down. That’s the power bullies have over people.

I didn’t have many friends then. I’d make friends easily, but if we didn’t move off after a few weeks, then their families did. When you’re that age you really look for someone to be your friend, especially if you feel you’re picked on otherwise. So perhaps it wasn’t a surprise that I fell in with some people who lived near Cara Park, in Belcamp House, a mansion that later burned down. They were a charismatic Christian group and I started going there just for the fun of it and then really got into attending the prayer meetings and other events they organised. I made some good friends there and for a while I became very serious about being involved in their kind of Roman Catholicism. For two years I was going to prayer meetings on Tuesdays and Thursdays, as well as Mass on Sundays. Saturdays we’d meet for bible study. It’s a surprise that I had time for anything else.

My greatest friends at Belcamp House were an American family called Cullins. Brendan Cullins was around my age and became my particular friend. The family moved back to the States and – it just goes to show the difference an education can make – Brendan went on to be a brain surgeon, while I ended up someone who goes to country lanes to bash people in the face for a living.

As kids we’d always boxed a bit. We couldn’t always play football or whatever game we wanted, but boxing was something else we could do near to the site. When we came back from picking spuds or wherever we’d been, if there wasn’t time to run off and get a game going, we could stay by the trailer and box. I’d always known I wasn’t very good at football, much as I liked to run about. I was always last to be picked to go on someone’s team, and when there’s fifteen to twenty kids standing on the pitch waiting to get the game going, this can be embarrassing. I was always the last one chosen because everyone knew that no matter how hard I tried I couldn’t kick a ball. It made me feel some kind of wimp that I couldn’t kick a football straight. To this day I think I must have been the worst footballer of any traveller in the world. Trying to play handball was no better. No one would play doubles with me, even though I liked the game. They didn’t want to waste their time because again I couldn’t play it.

Just about every sport I was rubbish at; so when I realised that I could throw out my two hands well, I was pleased. I don’t know whether people were happy for me that I’d found something I could do, or if they were just being polite, when they said, ‘You know, James, you’re not bad at that boxing there,’ but that motivated me. I’d finally found something that I enjoyed and that people liked seeing me doing. It would be big-headed of me to say I was good at boxing right from the start, but I’d found something that I was better at than most other people. I only took it up in the first place because I could do it and because I thought that if I was any good I could use it to stop being bullied – I had no idea where it would take me in the end. I just wanted to be able to look after myself in years to come.

My father never had a fist-fight in his life. His brother Chappy was known as a man to have had a few fights, but not my father. If my father got into trouble, Chappy would step in and take his place or go and sort it out. He had done a bit of boxing – or a bit of fighting, shall I say – but no training. So I’m not sure why my brother Paddy and I took to it so well. I just know we did.

When I was 10 and Paddy a year or so older, we were given boxing gloves for Christmas. Paddy loved boxing from the moment he started; he still loves it to this day, and although he’s a bit old to do the training now, he still has the head for it and knows what he’s doing. As Paddy’s sparring partner, it took me a while to do more than just stand there and block his punches. But eventually I did, and that’s when people noticed I could box quite well. So I was sent along to a club to train and learn to box properly.

Paddy started to box regularly at a local gym in Dundalk. When he went for his training sessions I would sometimes go down there with him. At first I felt out of place – the other boys seemed more powerful than me and I was long and skinny then – but after a while I got to like it. I started feeling fitter from all the training I did and once I had learned to protect myself properly I really started to enjoy the boxing itself.

I joined the Dealgan Boxing Club and I trained there for about a year and a half before we moved too far away for me to travel there easily. Then, when we moved to Cara Park, I carried on my training at the Darndale Boxing Club in Coolock, where they produced great boxers like Joe Lawler, who fought in the 1986 Olympics. There I learned how to move when boxing, how to breathe – not as simple as it sounds – and it was there I would have my first fights. The first thing the trainer, Joe Russell, taught me at Darndale was to breathe in through my nose, out through my mouth. ‘James,’ Joe said, ‘every chance you get, hold back, get the breath in your body. Stand off a little, not so far he notices but far enough to give you a little time to breathe. Take every chance you can. In through the nose, out through the mouth. Don’t show you’re breathing, like this’ – he would breathe heavily and fast through his mouth – ‘don’t let them know. Just step back and be on your foot, be on your back foot, be on your toe.’ Joe would demonstrate by standing tall and breathing deeply through his nose. ‘Side step. When you feel tired, you know, just step back a little bit. Drop the hand. Let the blood flow back in. If you hold it up for five minutes it gets tired. So you have to just pull it back in and relax.’ Now Joe was talking about fighting in a ring, where there are breaks to let you recover your breath and lower your guard. Years later, when I was fighting out in the air with no ropes and no breaks, his advice was still the best I’d been given. Rest, and breathe, whenever you can.

The boxing club itself was a place I liked to go to, because the people there had an attitude towards us travellers that was completely different from what we’d encountered at school. Schools hadn’t been very good to us, whereas the boxing club welcomed us in. Having someone teach me who encouraged me to improve every time I came in – a new experience after my years at school – meant not only that I started to enjoy my boxing, but that learning came easily to me. In addition, the training did a lot for my strength and my physique. I found aggression that I didn’t have outside in the world would come to me when I was in the ring. At first I wondered where this came from, because outside the ring I thought I was a normal person, but when I stepped into the ring it was a different story. Perhaps it was because with the gloves on and someone in front of me wanting to hit me, I became a different person.

Young traveller lads on the sites we stayed on were often keen to take up the sport because it meant they could say to themselves and their friends, ‘I can handle myself, I can box.’ Sometimes boxing clubs would have as many as ten or twelve travellers as members, but as usual they would come and go, depending on where their families were living and working and whether or not they could keep up the training. Me and Paddy were the most persistent two in the club; we stuck it out for a good few years, Paddy longer than I did. My younger brother Dave joined us in the club and he too was a good boxer, but he never kept it up the way Paddy did, or went out onto the street with it the way I did.

At the club I made good progress and was paired up with Joe Lawler as my sparring partner. He was about my age but a lot lighter than me and a lot smaller too. To be honest, Joe was my biggest nightmare there. He had a right-hand punch that I couldn’t seem to avoid, and when he hit me with it I was always taken by surprise because it was phenomenally hard. He would jump up slightly and sling his hand forward, and I’d see it coming at me, riding over the top of his reach until it connected with my head – bam. I don’t think he’d be allowed to use it now, but he’d just sink it on my head and I’d feel my brain pounding. Joe was brilliant: I watched him win nearly fifty fights with a knock-out, and in all of them that right hand of his made the difference. I used to dream about that punch, it preyed on my mind so much.

The first time I stepped into the ring for a competitive fight I wasn’t successful, but as it was my first fight I hadn’t had any experience, so I wasn’t disappointed that I lost that one, and besides I knew I’d fought very well. But the next fights went my way: I won every one of the following thirteen, both club and competition fights. Ten boxers would be picked from each club and put into the ring to fight each other. The biggest fights for me were when I fought for Dublin against Galway, Cork and Limerick in the under-18 County League as a little scrawny ten-stone welterweight.