Juggernaut

Juggernaut

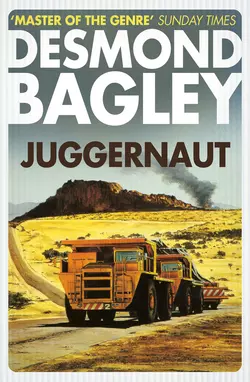

Desmond Bagley

Action thriller by the classic adventure writer set in Africa.It is no ordinary juggernaut. Longer than a football pitch, weighing 550 tons, and moving at just five miles per hour, its job – and that of troubleshooter Neil Mannix – is to move a giant transformer across an oil-rich African state. But when Nyala erupts in civil war, Mannix’s juggernaut is at the centre of the conflict – a target of ambush and threat, with no way to run and nowhere to hide…

DESMOND BAGLEY

Juggernaut

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_33a9aef5-d1f9-5538-abe2-bd9255635763)

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Collins 1985

Copyright © Brockhurst Publications 1985

Cover layout design Richard Augustus © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Desmond Bagley asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9780008211394

Ebook Edition © August 2017 ISBN: 9780008211400

Version: 2017-06-29

CONTENTS

Cover (#u5b47423a-ba76-5039-bb1b-9f900dfa0233)

Title Page (#uc7150c75-88b3-5c8d-92d5-94be0845075c)

Copyright (#u76d04578-b1b7-56ec-a014-f1fa6e49e9e4)

Juggernaut (#uacf33b38-a695-5bf2-92a9-3858f32f5a4b)

One (#u7bba76d8-aa83-5ff9-9761-d6aaf4296770)

Two (#u36d52048-84b1-5bb2-bcb1-e3322f16118c)

Three (#u90108dc7-1d51-5c0b-a30c-0a4745caa67d)

Four (#u5dd08539-9c55-5cb5-8c28-5f8d22555cc6)

Five (#u72f70cb3-daf4-5fe4-a150-c31f711523d6)

Six (#u8e580fbd-0d3a-5b5c-8931-881717c6b983)

Seven (#uc0e636e7-bf20-5b98-ab45-489a1c9928c8)

Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

JUGGERNAUT (#ulink_2c6424b2-f041-5808-9156-d496b65edf27)

ONE (#ulink_0e025d1f-bc88-59f6-93f2-74bef38078fc)

The telephone call came when I was down by the big circular pool chatting up the two frauleins I had cut out of the herd. I didn’t rate my chances too highly. They were of an age which regards any man of over thirty-five as falling apart at the seams; but what the hell, it was improving my German.

I looked up at the brown face of the waiter and said incredulously, ‘A phone call for me?’

‘Yes, sir. From London.’ He seemed impressed.

I sighed and grabbed my beach robe. ‘I’ll be back,’ I promised, and followed the waiter up the steps towards the hotel. At the top I paused. ‘I’ll take it in my room,’ I said, and cut across the front of the hotel towards the cabana I rented.

Inside it was cool, almost cold, and the air conditioning unit uttered a muted roar. I took a can of beer from the refrigerator, opened it, and picked up the telephone. As I suspected, it was Geddes. ‘What are you doing in Kenya?’ he asked. The line was good; he could have been in the next room.

I drank some beer. ‘What do you care where I take my vacations?’

‘You’re on the right continent. It’s a pity you have to come back to London. What’s the weather like there?’

‘It’s hot. What would you expect on the equator?’

‘It’s raining here,’ he said, ‘and a bit cold.’

I’d got used to the British by now. As with the Arabs there is always an exchange of small talk before the serious issues arise but the British always talk about the weather. I sometimes find it hard to take. ‘You didn’t ring me for a weather report. What’s this about London?’

‘Playtime is over, I’m afraid. We have a job for you. I’d like to see you in my office the day after tomorrow.’

I figured it out. Half an hour to check out, another hour to Mombasa to turn in the rented car. The afternoon flight to Nairobi and then the midnight flight to London. And the rest of that day to recover. ‘I might just make it,’ I conceded, ‘but I’d like to know why.’

‘Too complicated now. See you in London.’

‘Okay,’ I said grouchily. ‘How did you know I was here, by the way?’

Geddes laughed lightly. ‘We have our methods, Watson, we have our methods.’ There was a click and the line went dead.

I replaced the handset in disgust. That was another thing about the British – they were always flinging quotations at you, especially from Sherlock Holmes and Alice in Wonderland. Or Winnie the Pooh, for God’s sake!

I went outside the cabana and stood on the balcony while I finished the beer. The Indian Ocean was calm and palm fronds fluttered in a light breeze. The girls were splashing in the pool, having a mock fight, and their shrill laughter cut through the heated air. Two young men were watching them with interest. Goodbyes were unnecessary, I thought, so I finished the beer and went inside to pack.

A word about the company I work for. British Electric is about as British as Shell Oil is Dutch – it’s gone multinational, which is why I was one of the many Americans in its employ. You can’t buy a two kilowatt electric heater from British Electric, nor yet a five cubic foot refrigerator, but if you want the giant-sized economy pack which produces current measured in megawatts then we’re your boys. We’re at the heavy end of the industry.

Nominally I’m an engineer but it must have been ten years since I actually built or designed anything. The higher a man rises in a corporation like ours the less he is concerned with purely technical problems. Of course, the jargon of modern management makes everything sound technical and the subcommittee rooms resound with phrases drawn from critical path analysis, operations research and industrial dynamics, but all that flim-flam is discarded at the big boardroom table, where the serious decisions are made by men who know there is a lot more to management than the mechanics of technique.

There are lots of names for people like me. In some companies I’m called an expeditor, in others a troubleshooter. I operate in the foggy area bounded on the north by technical problems, on the east by finance, on the west by politics, and on the south by the sheer quirkiness of humankind. If I had to put a name to my trade I’d call myself a political engineer.

Geddes was right about London; it was cold and wet. There was a strong wind blowing which drove the rain against the windows of his office with a pattering sound. After Africa it was bleak.

He stood up as I entered. ‘You have a nice tan,’ he said appreciatively.

‘It would have been better if I could have finished my vacation. What’s the problem?’

‘You Yanks are always in such a hurry,’ complained Geddes. That was good for a couple of laughs. You don’t run an outfit like British Electric by resting on your butt and Geddes, like many other Britishers in a top ranking job, seemed deceptively slow but somehow seemed to come out ahead. The classic definition of a Hungarian as a guy who comes behind you in a revolving door and steps out ahead could very well apply to Geddes.

The second laugh was that I could never break them of the habit of calling me a Yank. I tried calling Geddes a Scouse once, and then tried to show him that Liverpool is closer to London than Wyoming to New England, but it never sank in.

‘This way,’ he said. ‘I’ve a team laid on in the boardroom.’

I knew most of the men there, and when Geddes said, ‘You all know Neil Mannix,’ there was a murmur of assent. There was one new boy whom I didn’t know, and whom Geddes introduced. ‘This is John Sutherland – our man on the spot.’

‘Which spot?’

‘I said you were on the right continent. It’s just that you were on the wrong side.’ Geddes pulled back a curtain covering a notice board to reveal a map. ‘Nyala.’

I said, ‘We’ve got a power station contract there.’

‘That’s right.’ Geddes picked up a pointer and tapped the map. ‘Just about there – up in the north. A place called Bir Oassa.’

Someone had stuck a needle into the skin of the earth and the earth bled copiously. Thus encouraged, another hypodermic went into the earth’s hide and the oil came up driven by the pressure of natural gas. The gas, although not altogether unexpected, was a bonus. The oil strike led to much rejoicing and merriment among those who held on to the levers of power in a turbulent political society. In modern times big oil means political power on a world scale, and this was a chance for Nyala to make its presence felt in the comity of nations, something it had hitherto conspicuously failed to do. Oil also meant money – lots of it.

‘It’s good oil,’ Geddes was saying. ‘Low sulphur content and just the right viscosity to make it bunker grade without refining. The Nyalans have just completed a pipeline from Bir Oassa to Port Luard, here on the coast. That’s about eight hundred miles. They reckon they can offer cheap oil to ships on the round-Africa run to Asia. They hope to get a bit of South American business too. But all that’s in the future.’

The pointer returned to Bir Oassa. ‘There remains the natural gas. There was talk of running a gas line paralleling the oil line, building a liquifying plant at Port Luard, and shipping the gas to Europe. The North Sea business has made that an uneconomical proposition.’

Geddes shifted the pointer further north, holding it at arm’s length. ‘Up there between the true desert and the rain forests is where Nyala plans to build a power station.’

Everyone present had already heard about this, but still there were murmurs and an uneasy shifting. It would take more than one set of fingers to enumerate the obvious problems. I picked one of them at random.

‘What about cooling water? There’s a drought in the Sahara.’

McCahill stirred. ‘No problem. We put down boreholes and tapped plenty of water at six thousand feet.’ He grimaced. ‘Coming up from that depth it’s pretty warm, but extra cooling towers will take care of that.’ McCahill was on the design staff.

‘And as a spin-off we can spare enough for local irrigation and consumption, and that will help to put us across to the inhabitants.’ This from Public Relations, of course.

‘The drought in the Sahara is going to continue for a long time yet,’ Geddes said. ‘If the Nyalans can use their gas to fuel a power station then there’ll be the more electricity for pumping whatever water there is and for irrigating. They can sell their surplus gas to neighbour states too. Niger is interested in that already.’

It made sense of a kind, but before they could start making their fortunes out of oil and gas they had to obtain the stuff. I went over to the map and studied it.

‘You’ll have trouble with transport. There’s the big stuff like the boilers and the transformers. They can’t be assembled on site. How many transformers?’

‘Five,’ McCahill said. ‘At five hundred megawatts each. Four for running and one spare.’

‘And at three hundred tons each,’ I said.

‘I think Mister Milner has sorted that out,’ said Geddes.

Milner was our head logistics man. He had to make sure that everything was in the right place at the right time, and his department managed to keep our computers tied up rather considerably. He came forward and joined me at the map. ‘Easy,’ he said. ‘There are some good roads.’

I was sceptical. ‘Out there – in Nyala?’

He nodded thoughtfully. ‘Of course, you haven’t been there yourself, have you, Neil? Wait until you read the full specs. But I’ll outline it for you and the others. After they got colonial rule their first president was Maro Ofanwe. Remember him?’

Someone made a throat-slitting gesture and there was a brief uneasy laugh. Nobody at the top likes to be reminded of coups of any sort.

‘He had the usual delusions of grandeur. One of the first things he did was to build a modern super-highway right along the coast from Port Luard to Hazi. Halfway along it, here at Lasulu, a branch goes north to Bir Oassa and even beyond – to nowhere. We shouldn’t have any trouble in that department.’

‘I’ll believe that road when I see it.’

Milner was annoyed and showed it. ‘I surveyed it myself with the boss of the transport company. Look at these photographs.’

He hovered at my elbow as I examined the pictures, glossy black-and-white aerial shots. Sure enough, there it was, looking as though it had been lifted bodily from Los Angeles and dumped in the middle of a scrubby nowhere.

‘Who uses it?’

‘The coast road gets quite a bit of use. The spur into the interior is under-used and under-maintained. The rain forest is encroaching in the south and in the north there will be trouble with sand drifts. The usual potholes are appearing. Edges are a bit worn in spots.’ This was common to most African tarmac and hardly surprised me. He went on, ‘There are some bridges which may be a bit dicey, but it’s nothing we can’t cope with.’

‘Is your transport contractor happy with it?’

‘Perfectly.’

I doubted that. A happy contractor is like a happy farmer – more or less nonexistent. But it was I who listened to the beefs, not the hirers and firers. I turned my attention back to Geddes, after mending fences with Milner by admiring his photographs.

‘I think Mister Shelford might have something to say,’ Geddes prompted.

Shelford was a political liaison man. He came from that department which was the nearest thing British Electric had to the State Department or the British Foreign Office. He cocked an eye at Geddes. ‘I take it Mr Mannix would like a rundown on the political situation?’

‘What else?’ asked Geddes a little acidly.

I didn’t like Shelford much. He was one of the striped pants crowd that infests Whitehall and Washington. Those guys like to think of themselves as decision makers and world shakers but they’re a long way from the top of the tree and they know it. From the sound of his voice, Geddes wasn’t too taken with Shelford either.

Shelford was obviously used to this irritable reaction to himself and ignored it. He spread his hands on the table and spoke precisely. ‘I regard Nyala as being one of the few countries in Africa which shows any political stability at the present time. That, of course, was not always so. Upon the overthrow of Maro Ofanwe there was considerable civil unrest and the army was forced to take over, a not atypical action in an African state. What was atypical, however, was that the army voluntarily handed back the reins of power to a properly constituted and elected civil government, which so far seems to be keeping the country on an even keel.’

Some of the others were growing restive under his lecturing, and Geddes cut in on what looked like the opening of a long speech. ‘That’s good so far,’ he said. ‘At least we won’t have to cope with the inflexibility of military minds.’

I grinned. ‘Just the deviousness of the political ones.’

Shelford showed signs of carrying on with his lecture and this time I cut in on him. ‘Have you been out there lately, Mister Shelford?’

‘No, I haven’t.’

‘Have you been there at all?’

‘No,’ he said stiffly. I saw a few stifled smiles.

‘I see,’ I said, and switched my attention to Sutherland. ‘I suggest we hear from the man on the spot. How did you find things, John?’

Sutherland glanced at Geddes for a nod of approval before speaking.

‘Well, broadly speaking, I should say that Mister Shelford seems correct. The country shows remarkable stability; within limits, naturally. They are having to cope with a cash shortage, a water shortage, border skirmishes – the usual African troubles. But I didn’t come across much conflict at the top when we were out there.’

Shelford actually smirked. Geddes said, ‘Do you think the guarantees of the Nyalan Government will stand up under stress, should it come?’

Sutherland was being pressed and he courageously didn’t waver too much. ‘I should think so, provided the discretionary fund isn’t skimped.’

By that he meant that the palms held out to be greased should be liberally daubed, a not uncommon situation. I said, ‘You were speaking broadly, John. What would you say if you had to speak narrowly?’

Now he looked a little uncomfortable and his glance went from Geddes to Shelford before he replied. ‘It’s said that there’s some tribal unrest.’

This brought another murmur to the room. To the average European, while international and even intercounty and intercity rivalries are understandable factors, the demands of tribal loyalties seem often beyond all reason; in my time I have tried to liken the situation to that of warring football clubs and their more aggressive fans, but non-tribal peoples seemed to me to have the greatest difficulties in appreciating the pressures involved. I even saw eyebrows raised, a gesture of righteous intolerance which none at that table could afford. Shelford tried to bluster.

‘Nonsense,’ he said. ‘Nyala’s a unified state if ever I saw one. Tribal conflict has been vanquished.’

I decided to prick his balloon. ‘Apparently you haven’t seen it, though, Mister Shelford. Conflict of this sort is never finished with. Remember Nigeria – it happened there, and that’s almost next door. It exists in Kenya. It exists throughout Africa. And we know that it’s hard to disentangle fact from fiction, but we can’t afford to ignore either. John, who are the top dogs in Nyala, the majority tribe?’

‘The Kinguru.’

‘The President and most of the Cabinet will be Kinguru, then? The Civil Service? Leading merchants and businessmen?’ He nodded at each category. ‘The Army?’

Here he shook his head. ‘Surprisingly enough, apparently not. The Kinguru don’t seem to make good fighters. The Wabi people run the military, but they have some sort of tribal affiliation with the Kinguru anyway. You’ll need a sociologist’s report if you want to go into details.’

‘If the Kinguru aren’t fighters they may damn well have to learn,’ I said, ‘Like the Ibo in Nigeria and the Kikuyu in Kenya.’

Someone said, ‘You’re presupposing conflict, Neil.’

Geddes backed me. ‘It’s not unwise. And we do have some comments in the dossier, Neil – your homework.’ He tapped the bulky file on the table and adroitly lightened the atmosphere. ‘I think we can leave the political issues for the moment. How do we stand on progress to date, Bob?’

‘We’re exactly on schedule,’ said Milner with satisfaction. He would have been pained to be behind schedule, but almost equally pained to have been ahead of it. That would show that his computers weren’t giving an absolutely optimum arrangement, which would be unthinkable. But then he leaned forward and the pleased look vanished. ‘We might be running into a small problem, though.’

There were no small problems in jobs like this. They were all big ones, no matter how small they started.

Milner said, ‘Construction is well advanced and we’re about ready to take up the big loads. The analysis calls for the first big haul to be one of the boilers but the government is insisting that it be a transformer. That means that the boiler fitters are going to be sitting around on their butts doing nothing while a transformer just lies around because the electrical engineers aren’t yet ready to install it.’ He sounded aggrieved and I could well understand why. This was big money being messed around.

‘Why would they want to do that?’ I asked.

‘It’s some sort of public relations exercise they’re laying on. A transformer is the biggest thing we’re going to carry, and they want to make a thing of it before the populace gets used to seeing the big flat-bed trundling around their country.’

Geddes smiled. ‘They’re paying for it. I think we can let them have that much.’

‘It’ll cost us money,’ warned Milner.

‘The project is costing them a hundred and fifty million pounds,’ said Geddes. ‘I’m sure this schedule change can be absorbed: and if it’s all they want changed I’ll be very pleased. I’m sure you can reprogramme to compensate.’ His voice was as smooth as cream, and it had the desired effect on Milner, who looked a lot happier. He had made his point, and I was sure that he had some slack tucked away in his programme to take care of such emergencies.

The meeting carried on well into the morning. The finance boys came in with stuff about progress payments in relationship to cash flow, and there was a discussion about tendering for the electrical network which was to spread after the completion of the power plant. At last Geddes called a halt, leaned over towards me and said quietly, ‘Lunch with me, Neil.’

It wasn’t an invitation; it was an order. ‘Be glad to,’ I said. There was more to come, obviously.

On the way out I caught up with Milner. ‘There’s a point that wasn’t brought up. Why unship cargo at Port Luard? Why not at Lasulu? That’s at the junction of the spur road leading upcountry.’

He shook his head. ‘Port Luard is the only deep water anchorage with proper quays. At Lasulu cargo is unshipped in to some pretty antique lighters. Would you like to transship a three hundred ton transformer into a lighter in a heavy swell?’

‘Not me,’ I said, and that was that.

I expected to lunch with Geddes in the directors’ dining room but instead he took me out to a restaurant. We had a drink at the bar while we chatted lightly about affairs in Africa, the state of the money market, the upcoming by-elections. It was only after we were at table and into our meal that he came back to the main topic.

‘We want you to go out there, Neil.’

This was very unsurprising, except that so far there didn’t seem to be a reason. I said, ‘Right now I should be out at Leopard Rock south of Mombasa, chatting up the girls. I suppose the sun’s just as hot on the west coast. Don’t know about the birds though.’

Geddes said, not altogether inconsequentially, ‘You should be married.’

‘I have been.’

We got on with the meal. I had nothing to say and let him make the running. ‘So you don’t mind solving the problem,’ he said eventually.

‘What problem? Milner’s got things running better than a Swiss watch.’

‘I don’t know what problem,’ Geddes said simply. ‘But I know there is one, and I want you to find it.’ He held up a hand to stop me interrupting. ‘It’s not as easy as it sounds, and things are, as you guessed, far from serene in Nyala under the surface. Sir Tom has had a whisper down the line from some of the old hands out there.’

Geddes was referring to our Chairman, Owner and Managing Director, a trinity called Sir Thomas Buckler. Feet firmly on the earth, head in Olympus, and with ears as big as a jack rabbit’s for any hint or form of peril to his beloved company. It was always wise to take notice of advice from that quarter, and my interest sharpened at once. So far there had been nothing to tempt me. Now there was the merest breath of warning that all might not be well, and that was the stuff I thrived on. As we ate and chatted on I felt a lot less cheesed off at having lost my Kenya vacation.

‘It may be nothing. But you have a nose for trouble, Neil, and I’m depending on you to sniff it out,’ Geddes said as we rose from the table. ‘By the way, do you know what the old colonial name for Port Luard used to be?’

‘Can’t say that I do.’

He smiled gently. ‘The Frying Pan.’

TWO (#ulink_e31c1a42-fad4-5225-9d95-f39172db5c69)

I left for Nyala five days later, the intervening time being spent in getting a run down on the country. I read the relevant sections of Keesing’s Archives but the company’s own files, prepared by our Confidential Information Unit, proved more valuable, mainly because our boys weren’t as deterred by thoughts of libel as the compilers of Keesing.

It seemed to be a fairly standard African story. Nyala was a British colony until the British divested themselves of their Empire, and the first President under the new constitution was Maro Ofanwe. He had one of the usual qualifications for becoming the leader of an ex-British colony; he had served time in a British jail. Colonial jails were the forcing beds of national leaders, the Eton and Harrow of the dark continent.

Ofanwe started off soberly enough but when seated firmly in the saddle he started showing signs of megalomania and damn near made himself the state religion. And like all megalomaniacs he had architectural ambitions, pulling down the old colonial centre of Port Luard to build Independence Square, a vast acreage of nothing surrounded by new government offices in the style known as Totalitarian Massive.

Ofanwe was a keen student of the politics of Mussolini, so the new Palace of Justice had a specially designed balcony where he was accustomed to display himself to the stormy cheers of his adoring people. The cheers were equally stormy when his people hauled up his body by the heels and strung it from one of the very modern lampposts in Independence Square. Maro Ofanwe emulated Mussolini as much in death as in life.

After his death there were three years of chaos. Ofanwe had left the Treasury drained, there was strife among competing politicians, and the country rapidly became ungoverned and ungovernable. At last the army stepped in and established a military junta led by Colonel Abram Kigonde.

Surprisingly, Kigonde proved to be a political moderate. He crushed the extremists of both wings ruthlessly, laid heavy taxes on the business community which had been getting away with what it liked, and used the money to revitalize the cash crop plantations which had become neglected and run down. He was lucky too, because just as the cocoa plantations were brought back to some efficiency the price of cocoa went up, and for a couple of years the money rolled in until the cocoa price cycle went into another downswing.

Relative prosperity in Nyala led to political stability. The people had food in their bellies and weren’t inclined to listen to anyone who wanted a change. This security led outside investors to study the country and now Kigonde was able to secure sizeable loans which went into more agricultural improvements and a degree of industrialization. You couldn’t blame Kigonde for devoting a fair part of these loans to re-equipping his army.

Then he surprised everybody again. He revamped the Constitution and announced that elections would be held and a civil government was to take over the running of the country once again. After five years of military rule he stepped down to become Major General Kigonde, Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces. Since then the government had settled down, its hand greatly strengthened by the discovery of oil in the north. There was the usual amount of graft and corruption but no more so, apparently, than in any other African country, and all seemed set fair for the future of Nyala.

But there were rumours.

I read papers, studied maps and figures, and on the surface this was a textbook operation. I crammed in a lot of appointments, trying to have at least a few words with anybody who was directly concerned with the Nyala business. For the most part these were easy, the people I wanted to see being all bunched up close together in the City; but there was one exception, and an important one. I talked to Geddes about it first.

‘The heavy haulage company you’re using, Wyvern Haulage Ltd. They’re new to me. Why them?’

Geddes explained. British Electric had part ownership of one haulage company, a firm with considerable overseas experience and well under the thumb of the Board, but they were fully occupied with other work. There were few other British firms in the same field, and Geddes had tendered the job to a Dutch and an American company, but in the end the contract had gone to someone who appeared to be almost a newcomer in the business. I asked if there was any nepotism involved.

‘None that I know of,’ Geddes said. ‘This crowd has good credentials, a good track record, and their price is damned competitive. There are too few heavy hauliers about who can do what we want them to do, and their prices are getting out of hand – even our own. I’m willing to encourage anyone if it will increase competition.’

‘Their price may be right for us, but is it right for them?’ I asked. ‘I can’t see them making much of a profit.’

It was vital that no firm who worked for us should come out badly. British Electric had to be a crowd whom others were anxious to be alongside. And I was far from happy with the figures that Wyvern were quoting, attractive though they might be to Milner and Geddes.

‘Who are they?’

‘They know their job, all right. It’s a splinter group from Sheffield Hauliers and we think the best of that bunch went to Wyvern when it was set up. The boss is a youngish chap, Geoffrey Wingstead, and he took Basil Kemp with him for starters.’

I knew both the names, Wingstead only as a noise but Kemp and I had met before on a similar job. The difference was that the transformer then being moved was from the British industrial midlands up to Scotland; no easy matter but a cake-walk compared with doing any similar job in Africa. I wondered if Wyvern had any overseas experience, and decided to find out for myself.

To meet Wingstead I drove up to Leeds, and was mildly startled at what I found when I got there. I was all in favour of a new company ploughing its finances into the heart of the business rather than setting up fancy offices and shop front prestige, but to find Geoff Wingstead running his show from a prefab shed right in amongst the workshops and garaging was disturbing. It was a string-and-brown-paper setup of which Wingstead seemed to be proud.

But I was impressed by him and his paperwork, and could not fault either. I had wanted to meet Kemp again, only to be told that he was already in Nyala with his load boss and crew, waiting for the arrival of the rig by sea. Wingstead himself intended to fly out when the rig was ready for its first run, a prospect which clearly excited him: he hadn’t been in Africa before. I tried to steer a course midway between terrifying him with examples of how different his job would be out there from anything he had experienced in Europe, and overboosting his confidence with too much enthusiasm. I still had doubts, but I left Leeds and later Heathrow with a far greater optimism than I’d have thought possible.

On paper, everything was splendid. But I’ve never known events to be transferred from paper to reality without something being lost in the translation.

Port Luard was hot and sweaty. The temperature was climbing up to the hundred mark and the humidity was struggling to join it. John Sutherland met me at the airport which was one of Ofanwe’s white elephants: runways big enough to take jumbos and a concourse three times the size of Penn Station. It was large enough to serve a city the size of, say, Rome.

A chauffeur driven car awaited outside the arrivals building. I got in with Sutherland and felt the sweat break out under my armpits, and my wet shirt already sticking to my back. I unbuttoned the top of my shirt and took off my jacket and tie. I had suffered from cold at Heathrow and was overdressed here – a typical traveller’s dilemma. In my case was a superfine lightweight tropical suit by Huntsman – that was for hobnobbing with Cabinet ministers and suchlike – and a couple of safari suits. For the rest I’d buy local gear and probably dump it when I left. Cheap cotton shirts and shorts were always easy to get hold of.

I sat back and watched the country flow by. I hadn’t been to Nyala before but it wasn’t much different from Nigeria or any other West African landscape. Personally I preferred the less lush bits of Africa, the scrub and semi-desert areas, and I knew I’d be seeing plenty of that later on. The advertisements for Brooke Bond Tea and Raleigh Bicycles still proclaimed Nyala’s British colonial origins, although those for Coca-Cola were universal.

It was early morning and I had slept on the flight. I felt wide awake and ready to go, which was more than I could say for Sutherland. He looked exhausted, and I wondered how tough it was getting for him.

‘Do we have a company plane?’ I asked him.

‘Yes, and a good pilot, a Rhodesian.’ He was silent for a while and then said cautiously, ‘Funny meeting we had last week. I was pulled back to London at twelve hours’ notice and all that happened was that we sat around telling each other things we already knew.’

He was fishing and I knew it.

‘I didn’t know most of it. It was a briefing for me.’

‘Yes, I rather guessed as much.’

I asked, ‘How long have you been with the company?’

‘Seven years.’

I’d never met him before, or heard of him, but that wasn’t unusual. It’s a big outfit and I met new faces regularly. But Sutherland would have heard of me, because my name was trouble; I was the hatchet man, the expeditor, sometimes the executioner. As soon as I pitched up on anyone’s territory there would be that tightening feeling in the gut as the local boss man wondered what the hell had gone wrong.

I said, to put him at his ease, ‘Relax, John. It’s just that Geddes has got ants in his pants. Trouble is they’re invisible ants. I’m just here on an interrupted vacation.’

‘Oh quite,’ Sutherland said, not believing a word of it. ‘What do you plan to do first?’

‘I think I’d like to go up to the site at Bir Oassa for a couple of days, use the plane and overfly this road of theirs. After that I might want to see someone in the Government. Who would you suggest?’

Sutherland stroked his jaw. He knew that I’d read up on all of them and that it was quite likely I knew more about the local scene than he did. ‘There’s Hamah Ousemane – he’s Minister for the Interior, and there’s the Finance Minister, John Chizamba. Either would be a good starting point. And I suppose Daondo will want to put his oar in.’

‘He’s the local Goebbels, isn’t he?’

‘Yes, Minister for Misinformation.’

I grinned and Sutherland relaxed a little more. ‘Who has the itchiest palm? Or by some miracle are none of them on the take?’

‘No miracles here. As for which is the greediest, that I couldn’t say. But you should be able to buy a few items of information from almost anyone.’

We were as venal as the men we were dealing with. There was room for a certain amount of honesty in my profession but there was also room for the art of wheeling and dealing, and frankly I rather enjoyed that. It was fun, and I didn’t ever see why making one’s living had to be a joyless occupation.

I said, ‘Right. Now, don’t tell me you haven’t any problems. You wouldn’t be human if you didn’t. What’s the biggest headache on your list right now?’

‘The heavy transport.’

‘Wyvern? What exactly is wrong?’

‘The first load is scheduled to leave a week from today but the ship carrying the rig hasn’t arrived yet. She’s on board a special freighter, not on a regular run, and she’s been held up somewhere with customs problems. Wyvern’s road boss is here and he’s fairly sweating. He’s been going up and down the road checking gradients and tolerances and he’s not too happy with some of the things he’s seen. He’s back in town now, ready to supervise the unloading of the rig.’

‘The cargo?’

‘Oh, the transformers and boilers are all OK. It’s just that they’re a bit too big to carry up on a Land Rover. Do you want to meet him right away?’

‘No, I’ll see him when I come back from Bir Oassa. No point in our talking until there’s something to talk about. And the non-arrival of the rig isn’t a topic.’

I was telling him that I wasn’t going to interfere in his job and it made him happier to know it. We had been travelling up a wide boulevard and now emerged into a huge dusty square, complete with a vast statue of a gentleman whom I knew to be Maro Ofanwe sitting on a plinth in the middle. Why they hadn’t toppled his statue along with the original I couldn’t imagine. The car wove through the haphazard traffic and stopped at one of the last remaining bits of colonial architecture in sight, complete with peeling paint and sagging wooden balconies. It was, needless to say, my hotel.

‘Had a bit of a job getting you a room,’ Sutherland said, thus letting me know that he was not without the odd string to pull.

‘What’s the attraction? It’s hardly a tourist’s mecca.’

‘By God, it isn’t! The attraction is the oil. You’ll find Luard full of oil men – Americans, French, Russians, the lot. The Government has been eclectic in its franchises.’

As the car pulled up he went on, ‘Anything I can do for you right now?’

‘Nothing for today, thanks, John. I’ll book in and get changed and cleaned up, do some shopping, take a stroll. Tomorrow I’d like a car here at seven-thirty to take me to the airport. Are you free this evening?’

Sutherland had been anticipating that question, and indicated that he was indeed available. We arranged to meet for a drink and a light meal. Any of the things I’d observed or thought about during the day I could then try out on him. Local knowledge should never be neglected.

By nine the next morning I was flying along the coast following the first 200 miles of road to Lasulu where we were to land for refuelling before going on upcountry. There was more traffic on the road than I would have expected, but far less than a road of that class was designed to carry. I took out the small pair of binoculars I carried and studied it.

There were a few saloons and four-wheel drive vehicles, Suzukis and Land Rovers, and a fair number of junky old trucks. What was more surprising were the number of big trucks; thirty – and forty-tonners. I saw that one of them was carrying a load of drilling pipe. The next was a tanker, then another carrying, from the trail it left, drilling mud. This traffic was oil-generated and was taking supplies from Port Luard to the oilfields in the north.

I said to the pilot, a cheerful young man called Max Otterman, ‘Can you fly to the other side of Lasulu, please? Not far, say twenty miles. I want to look at the road over there.’

‘It peters out a mile or so beyond the town. But I’ll go on a way,’ he said.

Sure enough the road vanished into the miniature buildup around Lasulu, reemerging inland from the coast. On the continuation of the coastal stretch another road carried on northwards, less impressive than the earlier section but apparently perfectly usable. The small harbour did not look busy, but there were two or three fair-sized craft riding at anchor. Not easy to tell from the air, but it didn’t seem as though there was a building in Lasulu higher than three storeys. The endless frail smoke of shantytown cooking fires wreathed all about it.

Refuelling was done quickly at the airstrip, and then we turned inland. From Lasulu to Bir Oassa was about 800 miles and we flew over the broad strip of concrete thrusting incongruously through mangrove swamp, rain forest, savannah and the scrubby fringes of desert country. It had been built by Italian engineers, Japanese surveyors and a mixture of road crews with Russian money and had cost twice as much as it should, the surplus being siphoned off into a hundred unauthorized pockets and numbered accounts in Swiss banks – a truly international venture.

The Russians were not perturbed by the way their money was used. They were not penny-pinchers and, in fact, had worked hard to see that some of the surplus money went into the right pockets. It was a cheap way of buying friends in a country that was poised uncertainly and ready to topple East or West in any breeze. It was another piece laid on the chessboard of international diplomacy to fend off an identical move by another power.

The road drove through thick forest and then heaved itself up towards the sky, climbing the hills which edged the central plateau. Then it crossed the sea of grass and bush to the dry region of the desert and came to Bir Oassa where the towers of oil rigs made a newer, metal forest.

I spent two days in Bir Oassa talking to the men and the bosses, scouting about the workings, and cocking an ear for any sort of unrest or uneasiness. I found very little worthy of note and nothing untoward. I did have a complaint from Dick Slater, the chief steam engineer, who had been sent word of the change of schedule and didn’t like it.

‘I’ll have thirty steam fitters playing pontoon when they should be working,’ he said abrasively to me. ‘Why the bloody hell do they have to send the transformers first?’

It had all been explained to him but he was being wilful. I said, ‘Take it easy. It’s all been authorized by Geddes from London.’

‘London! What do they know about it? This Geddes doesn’t understand the first damn thing about it,’ he said. Slater wasn’t the man to be mealy-mouthed. I calmed him down – well, maybe halfway down – and went in search of other problems. It worried me when I couldn’t find any.

On the second day I had a phone call from Sutherland. On a crackling line full of static and clashing crossed wires his voice said faintly, ‘… Having a meeting with Ousemane and Daondo. Do you want …?’

‘Yes, I do want to sit in on it. You and who else?’ I was shouting.

‘… Kemp from Wyvern. Tomorrow morning …’

‘Has the rig come?’

‘… Unloading … came yesterday …’

‘I’ll be there.’

The meeting was held in a cool room in the Palace of Justice. The most important government man there was the Minister of the Interior, Hamah Ousemane, who presided over the meeting with a bland smile. He did not say much but left the talking to a short, slim man who was introduced as Zinsou Daondo. I couldn’t figure whether Ousemane didn’t understand what was going on, or understood and didn’t care: he displayed a splendid indifference.

Very surprising for a meeting of this kind was the presence of Major General Abram Kigonde, the army boss. Although he was not a member of the government he was a living reminder of Mao’s dictum that power grows out of the muzzle of a gun. No Nyalan government could survive without his nod of approval. At first I couldn’t see where he fitted in to this discussion on the moving of a big piece of power plant.

On our side there were myself, Sutherland, and Basil Kemp, who was a lean Englishman with a thin brown face stamped with tiredness and worry marks. He greeted me pleasantly enough, remembering our last encounter some few years before and appearing unperturbed by my presence. He probably had too much else on his plate already. I let Sutherland make the running and he addressed his remarks to the Minister while Daondo did the answering. It looked remarkably like a ventriloquist’s act but I found it hard to figure out who was the dummy. Kigonde kept a stiff silence.

After some amiable chitchat (not the weather, thank God) we got down to business and Sutherland outlined some routine matters before drawing Kemp into the discussion. ‘Could we have a map, please, Mister Kemp?’

Kemp placed a map on the big table and pointed out his bottlenecks.

‘We have to get out of Port Luard and through Lasulu. Both are big towns and to take a load like this through presents difficulties. It has been my experience in Europe that operations like this draw the crowds and I can’t see that it will be different here. We should appreciate a police escort.’

Daondo nodded. ‘It will certainly draw the crowds.’ He seemed pleased.

Kemp said, ‘In Europe we usually arrange to take these things through at extreme off-peak times. The small hours of the night are often best.’

This remark drew a frown from Daondo and I thought I detected the slightest of headshakes from the Minister. I became more alert.

Kigonde stirred and spoke for the first time, in a deep and beautifully modulated voice. ‘You will certainly have an escort, Mister Kemp – but not the police. I am putting an army detachment at your service.’ He leaned forward and pressed a button, the door of the room opened, and a smartly dressed officer strode towards the table. ‘This is Captain Ismail Sadiq who will command the escort.’

Captain Sadiq clicked to attention, bowing curtly, and then at a nod from Kigonde stood at ease at the foot of the table.

Daondo said, The army will accompany you all the way.’

‘The whole journey?’ Sutherland asked.

‘On all journeys.’

I sensed that Sutherland was about to say something wrong, and forestalled him. ‘We are more than honoured, Major General. This is extremely thoughtful of you and we appreciate it. It is more of an honour than such work as this usually entails.’

‘Our police force is not large, and already has too much work. We regard the safekeeping of such expeditions as these of the greatest importance, Mister Mannix. The army stands ready to be of any service.’ He was very smooth, and I reckoned that we’d come out of that little encounter about equal. I prepared to enjoy myself.

‘Please explain the size of your command, Captain,’ Daondo said.

Sadiq had a soft voice at odds with his appearance. ‘For work on the road I have four infantry troop carriers with six men to each carrier, two trucks for logistics purposes, and my own command car, plus outriders. Eight vehicles, six motorcycles and thirty-six men including myself. In the towns I am empowered to call on local army units for crowd control.’

This was bringing up the big guns with a vengeance. I had never heard of a rig which needed that kind of escort, whether for crowd control or for any other form of safety regulations, except in conditions of war. My curiosity was aroused by now, but I said nothing and let Sutherland carry on. Taking his cue from me he expressed only his gratitude and none of his perturbation. He’d expected a grudging handful of ill-trained local coppers at best.

Kigonde was saying, ‘In the Nyalan army the rank of captain is relatively high, gentlemen. You need not fear being held up in any way.’

‘I am sure not,’ said Kemp politely. ‘It will be a pleasure having your help, Captain. But now there are other matters as well. I am sorry to tell you that the road has deteriorated slightly in some places, and my loads may be too heavy for them.’

That was an understatement, but Kemp was working hard at diplomacy. Obviously he was wondering if Sadiq had any idea of the demands made by heavy transport, and if army escort duty also meant army assistance. Daondo picked him up and said easily, ‘Captain Sadiq will be authorized to negotiate with the civil bodies in each area in which you may find difficulty. I am certain that an adequate labour force will be found for you. And, of course, the necessary materials.’

It all seemed too good to be true. Kemp went on to the next problem.

‘Crowd control in towns is only one aspect, of course, gentlemen. There is the sheer difficulty of pushing a big vehicle through a town. Here on the map I have outlined a proposed route through Port Luard, from the docks to the outskirts. I estimate that it will take eight or nine hours to get through. The red line marks the easiest, in fact the only route, and the figures in circles are the estimated times at each stage. That should help your traffic control, although we shouldn’t have too much trouble there, moving through the central city area mostly during the night.’

The Minister made a sudden movement, wagging one finger sideways. Daondo glanced at him before saying, ‘It will not be necessary to move through Port Luard at night, Mister Kemp. We prefer you to make the move in daylight.’

‘It will disrupt your traffic flow considerably,’ said Kemp in some surprise.

‘That is of little consequence. We can handle it.’ Daondo bent over the map. ‘I see your route lies through Independence Square.’

‘It’s really the only way,’ said Kemp defensively. ‘It would be quite impossible to move through this tangle of narrow streets on either side without a great deal of damage to buildings.’

‘I quite agree,’ said Daondo. ‘In fact, had you not suggested it we would have asked you to go through the Square ourselves.’

This appeared to come as a wholly novel idea to Kemp. I could see he was thinking of the squalls of alarm from the London Metropolitan Police had he suggested pushing a 300-ton load through Trafalgar Square in the middle of the rush hour. Wherever he’d worked in Europe, he had been bullied, harassed and crowded into corners and sent on his way with the stealth of a burglar.

He paused to take this in with one finger still on the map. ‘There’s another very real difficulty here, though. This big plinth in the middle of the avenue leading into the Square. It’s sited at a very bad angle from our point of view – we’re going to have a great deal of difficulty getting around it. I would like to suggest –’

The Minister interrupted him with an unexpected deep-bellied, rumbling chuckle but his face remained bland. Daondo was also smiling and in his case too the smile never reached his eyes. ‘Yes, Mister Kemp, we see what you mean. I don’t think you need trouble about the plinth. We will have it removed. It will improve the traffic flow into Victory Avenue considerably in any case.’

Kemp and Sutherland exchanged quick glances. ‘I … I think it may take time,’ said Sutherland. ‘It’s a big piece of masonry.’

‘It is a task for the army,’ said Kigonde and turned to Sadiq. ‘See to it, Captain.’

Sadiq nodded and made quick notes. The discussion continued, the exit from Port Luard was detailed and the progress through Lasulu dismissed, for all its obvious difficulties to us, as a mere nothing by the Nyalans. About an hour later, after some genteel refreshment, we were finally free to go our way. We all went up to my hotel room and could hardly wait to get there before indulging in a thorough postmortem of that extraordinary meeting. It was generally agreed that no job had ever been received by the local officials with greater cooperation, any problem melting like snowflakes in the steamy Port Luard sunshine. Paradoxically it was this very ease of arrangement that made us all most uneasy, especially Basil Kemp.

‘I can’t believe it,’ he said, not for the first time. ‘They just love us, don’t they?’

‘I think you’ve put your finger on it, Basil,’ I said. ‘They really need us and they are going all out to show it. And they’re pretty used to riding roughshod over the needs and wishes of their populace, assuming it has any. They’re going to shove us right down the middle in broad daylight, and the hell with any little obstacles.’

‘Such as the plinth,’ said Sutherland and we both laughed.

Kemp said, ‘I think I missed something there. A definite undercurrent. I must say I haven’t looked at this thing too closely myself – what is it anyway – some local bigwig?’

Sutherland chuckled. ‘I thought old Ousemane would split his breeches. There’s a statue of Maro Ofanwe still on that plinth: thirty feet high in bronze, very heroic. Up to now they’ve been busy ignoring it, as it was a little too hefty to blow up or knock down, but now they’ve got just the excuse they want. It’ll help to serve notice that they don’t want any more strong men about, in a none too subtle sort of way. Ofanwe was an unmitigated disaster and not to be repeated.’

THREE (#ulink_2cbc5d29-6887-54d9-96ab-9c1a9937bdeb)

During the next few days I got on with my job, which mainly consisted of trying to find out what my job was. I talked with various members of the Government and had a special meeting with the Minister of Finance which left us both happy. I also talked to journalists in the bars, one or two businessmen and several other expatriates from Britain who were still clinging on to their old positions, most of them only too ready to bewail the lost days of glory. I gleaned a lot, mostly of misinformation, but slowly I was able to put together a picture which didn’t precisely coincide with that painted by Shelford back in London.

I was also made an honorary member of the Luard Club which, in colonial days, had strictly white membership but in these times had become multi-racial. There were still a number of old Africa hands there as well, and from a couple of them I got another whiff of what might be going bad in Nyala.

In the meantime Kemp and Sutherland were getting on with their business, to more immediate ends. On the morning the first big load was to roll I was up bright and early, if not bushy tailed. The sun had just risen and the temperature already in the eighties when I drove to the docks to see the loaded rig. I hadn’t had much chance to talk to Kemp and while I doubted that this was the moment, I had to pin him down to some time and place.

I found him and Sutherland in the middle of a small slice of chaos, both looking harassed as dozens of men milled around shouting questions and orders. They’d been at it for a long time already and things were almost ready to go into action. I stared in fascination at what I saw.

The huge rig wasn’t unfamiliar to me but it was still a breathtaking sight. The massive towing trucks, really tractors with full cab bodies, stood at each end of the flat-bed trailer onto which the transformer had been lowered, inch by painful inch, over the previous few hours. Around it scurried small dockside vehicles, fork-lift trucks and scooters, like worker ants scrambling about their huge motionless queen. But what fascinated and amused me was the sight of a small platoon of Nyalan dock hands clambering about the actual rig itself, as agile and noisy as a troop of monkeys, busy stringing yards of festive bunting between any two protruding places to which they could be tied. The green and yellow colours of the Nyalan flag predominated, and one of them was being hauled up a jackstaff which was bound to the front tractor bumpers. No wonder that Kemp looked thunderstruck and more than a little grim.

I hurried over to him, and my arrival coincided with that of Mr Daondo, who was just getting out of a black limousine. Daondo stood with hands on hips and gazed the length of the enormous rig with great satisfaction, then turned to us and said in a hearty voice, ‘Well, good morning, gentlemen. I see everything is going very well indeed.’

Kemp said, ‘Good morning, Mister Daondo – Neil. May I ask what –’

‘Hello, Basil. Great day for it, haven’t we? Mister Daondo, would you excuse us for just one moment? I’ve got your figures here, Basil …’

Talking fast, waving a notebook, and giving him no time to speak, I managed to draw Kemp away from Daondo’s side, leaving the politician to be entertained for a moment by John Sutherland.

‘Just what the hell do they think they’re doing?’ Kemp was outraged.

‘Ease off. Calm down. Can’t you see? They’re going to put on a show for the people – that’s what this daylight procession has been about all along. The power plant is one of the biggest things that’s ever happened to Nyala and the Government wants to do a bit of bragging. And I don’t see why not.’

‘But how?’ Kemp, normally a man of broad enough intelligence, was on a very narrow wave length where his precious rig was concerned.

‘Hasn’t the penny dropped yet? You’re to be the centre-piece of a triumphal parade through the town, right through Independence Square. The way the Ruskies trundle their rockets through Red Square on May Day. You’ll be on show, the band will play, the lot.’

‘Are you serious?’ said Kemp in disgust.

‘Quite. The Government must not only govern but be seen to govern. They’re entitled to bang their drum.’

Kemp subsided, muttering.

‘Don’t worry. As soon as you’re clear of the town you can take the ribbons out of her hair and get down to work properly. Have a word with your drivers. I’d like to meet them, but not right away. And tell them to enjoy themselves. It’s a gala occasion.’

‘All right, I suppose we must. But it’s damn inconvenient. It’s hard enough work moving these things without having to cope with cheering mobs and flag-waving.’

‘You don’t have to cope, that’s his job.’ I indicated Daondo with a jerk of my thumb. ‘Your guys just drive it away as usual. I think we’d better go join him.’

We walked back to where Daondo, leaning negligently against the hood of his Mercedes, was holding forth to a small circle of underlings. Sutherland was in the thick of it, together with a short, stocky man with a weathered face. Sutherland introduced him to me.

‘Neil, this is Ben Hammond, my head driver. Ben, Mister Mannix of British Electric. I think Ben’s what you’d call my ranch foreman.’

I grinned. ‘Nice herd of cattle you’ve got there, Ben. I’d like to meet the crew later. What’s the schedule?’

‘I’ve just told Mister Daondo that I think they’re ready to roll any time now. But of course it’s Mister Kemp’s show really.’

‘Thank you, Mister Sutherland. I’ll have a word with Daondo and then we can get going,’ Kemp said.

I marvelled at the way my British companions still managed to cling to surnames and honorifics. I wondered if they’d all be dressing for dinner, out there in the bush wherever the rig stopped for the night. I gave my attention to Daondo to find that he was being converged upon by a band of journalists, video and still cameras busy, notebooks poised, but with none of the free-for-all shoving that might have taken place anywhere in Europe. The presence of several armed soldiers nearby may have had a bearing on that.

‘Ah, Mister Mannix,’ Daondo said, ‘I am about to hold a short press conference. Would you join me, please?’

‘An honour, Minister. But it’s not really my story – it’s Mister Kemp’s.’

Kemp gave me a brief dirty look as I passed the buck neatly to him. ‘May I bring Mister Hammond in on this?’ he asked, drawing Ben Hammond along by the arm. ‘He designed this rig; it’s very much his baby.’

I looked at the stocky man in some surprise. This was something I hadn’t known and it set me thinking. Wyvern Haulage might be new as an outfit, but they seemed to have gathered a great deal of talent around them, and my respect for Geoff Wingstead grew fractionally greater.

The press conference was under way, to a soft barrage of clicks as people were posed in front of the rig. Video cameramen did their trick of walking backwards with a buddy’s hand on their shoulder to guide them, and the writer boys ducked and dodged around the clutter of ropes, chain, pulleys and hawsers that littered the ground. Some of the inevitable questions were coming up and I listened carefully, as this was a chance for me to learn a few of the technicalities.

‘Just how big is this vehicle?’

Kemp indicated Ben Hammond forward. Ben, grinning like a toothpaste advertisement, was enjoying his moment in the limelight as microphones were thrust at him. ‘As the transporter is set up now it’s a bit over a hundred feet long. We can add sections up to another eighteen feet but we won’t need them on this trip.’

‘Does that include the engines?’

‘The tractors? No, those are counted separately. We’ll be adding on four tractors to get over hilly ground and then the total length will be a shade over two hundred and forty feet.’

Another voice said, ‘Our readers may not be able to visualize that. Can you give us anything to measure it by?’

Hammond groped for an analogy, and then said, ‘I notice that you people here play a lot of soccer – football.’

‘Indeed we do,’ Daondo interjected. ‘I myself am an enthusiast.’ He smiled modestly as he put in his personal plug. ‘I was present at the Cup Final at Wembley last year, when I was Ambassador to the United Kingdom.’

Hammond said, ‘Well, imagine this. If you drove this rig onto the field at Wembley, or any other standard soccer pitch, it would fill the full length of the pitch with a foot hanging over each side. Is that good enough?’

There was a chorus of appreciative remarks, and Kemp said in a low voice, ‘Well done, Ben. Carry on.’

‘How heavy is the vehicle?’ someone asked.

‘The transporter weighs ninety tons, and the load, that big transformer, is three hundred tons. Add forty tons for each tractor and it brings the whole lot to five hundred and fifty tons on the hoof.’

Everybody scribbled while the cameras ground on. Hammond added, airing some knowledge he had only picked up in the last few days, ‘Elephants weigh about six tons each; so this is worth nearly a hundred elephants.’

The analogy was received with much amusement.

‘Those tractors don’t look big enough to weigh forty tons,’ he was prompted.

‘They carry ballast. Steel plates embedded in concrete. We have to have some counterbalance for the weight of the load or the transporter will overrun the tractors – especially on the hills. Negotiating hill country is very tricky.’

‘How fast will you go?’

Kemp took over now. ‘On the flat with all tractors hooked up I dare say we could push along to almost twenty miles an hour, even more going downhill. But we won’t. Five hundred and fifty tons going at twenty miles an hour takes a lot of stopping, and we don’t take risks. I don’t think we’ll do much more than ten miles an hour during any part of the journey, and usually much less. Our aim is to average five miles an hour during a ten hour day; twenty days from Port Luard to Bir Oassa.’

This drew whistles of disbelief and astonishment. In this age of fast transport, it was interesting that extreme slowness could exert the same fascination as extreme speed. It also interested me to notice that Nyala had not yet converted its thinking to the metric unit as far as distances were concerned.

‘How many wheels does it have?’

Hammond said, ‘Ninety-six on the ground and eight spares.’

‘How many punctures do you expect?’

‘None – we hope.’ This drew a laugh.

‘What’s the other big truck?’

‘That’s the vehicle which carries the airlift equipment and the machinery for powering it,’ said Kemp. ‘We use it to spread the load when crossing bridges, and it works on the hovercraft principle. It’s powered by four two hundred and forty-hp Rolls Royce engines – and that vehicle itself weighs eight tons.’

‘And the others?’

‘Spares, a workshop for maintenance, food and personal supplies, fuel. We have to take everything with us, you see.’

There was a stir as an aide came forward to whisper something into Daondo’s ear. He raised his hand and his voice. ‘Gentlemen, that will be all for now, thank you. I invite you all to gather round this great and marvellous machine for its dedication by His Excellency, the Minister of the Interior, the Right Honourable Hamah Ousemane, OBE.’ He touched me on the arm. ‘This way, please.’

As we followed him I heard Hammond saying to Kemp, ‘What’s he going to do? Crack a bottle of champagne over it?’

I grinned back at him. ‘Did you really design this thing?’

‘I designed some modifications to a standard rig, yes.’

Kemp said, ‘Ben built a lot of it, too.’

I was impressed. ‘For a little guy you sure play with big toys.’

Hammond stiffened and looked at me with hot eyes. Clearly I had hit on a sore nerve. ‘I’m five feet two and a half inches tall,’ he said curtly. ‘And that’s the exact height of Napoleon.’

‘No offence meant,’ I said quickly, and then we all came to a sudden stop at the rig to listen to Ousemane’s speech. He spoke first in English and then in Nyalan for a long time in a rolling, sonorous voice while the sun became hotter and everybody wilted. Then came some ribbon cutting and handshakes all round, some repeated for the benefit of the press, and finally he took himself off in his Mercedes. Kemp mopped his brow thankfully. ‘Do you think we can get on with it now?’ he asked nobody in particular.

Daondo was bustling back to us. In the background a surprising amount of military deployment was taking place, and there was an air of expectancy building up. ‘Excellent, Mister Kemp! We are all ready to go now,’ Daondo said. ‘You will couple up all the tractors, won’t you?’

Kemp turned to me and said in a harassed undertone, ‘What for? We won’t be doing more than five miles an hour on the flat and even one tractor’s enough for that.’

I was getting a bit tired of Kemp and his invincible ignorance and I didn’t want Daondo to hear him and blow a gasket. I smiled past Kemp and said, ‘Of course. Everything will be done as you wish it, Minister.’

‘Good,’ he said. ‘I must get to Independence Square before you arrive. I leave Captain Sadiq in command of the arrangements.’ He hurried away to his car.

I said to Kemp, putting an edge on my voice, ‘We’re expected to put on a display and we’ll do it. Use everything you’ve got. Line ’em up, even the chow wagon. Until we leave town it’s a parade every step of the way.’

‘Who starts this parade?’

‘You do – just tell your drivers to pull off in line whenever they’re ready. The others will damn well have to fall in around you. I’ll ride with you in the Land Rover.’

Kemp shrugged. ‘Bunch of clowns,’ he said and went off to give his drivers their instructions. For the moment I actually had nothing to do and I wandered over to have another look at the rig. It’s a funny thing, but whenever a guy looks at a vehicle he automatically kicks a tyre. Ask any second-hand auto salesman. So that’s what I did. It had about as much effect as kicking a building and was fairly painful. The tyres were all new, with deep tread earthmovers on the tractors. The whole rig looked brand new, as if it had never been used before, and I couldn’t decide if this was a good or a bad thing. I squinted up at it as it towered over me, remembering the one time I had towed a caravan and had it jackknife on me, and silently tipped my hat to the drivers of this outfit. They were going to need skill and luck in equal proportions on this trip.

Kemp drew up beside me in the Land Rover with a driver and I swung in the back. There was a lot of crosstalk going on with walkie-talkies, and a great deal of bustle and activity all around us.

‘All right, let’s get rolling,’ Kemp said into the speaker. ‘Take station on me, Ben: about three mph and don’t come breathing down my neck.’ He then said much the same thing into his car radio as drivers climbed into cabs and the vast humming roar of many engines began throbbing. Captain Sadiq rolled up alongside us in the back of an open staff car and saluted smartly.

‘I will lead the way, Mister Kemp. Please to follow me,’ he said.

‘Please keep your speed to mine, Captain,’ Kemp said.

‘Of course, sir. But please watch me carefully too. I may have to stop at some point. You are all ready?’

Kemp nodded and Sadiq pulled away. Kemp was running down a roster of drivers, getting checks from each of them, and then at last signalled his own driver to move ahead in Sadiq’s wake. I would have preferred to be behind the rig, but had to content myself with twisting in the rear seat of the car to watch behind me. To my astonishment something was joining in the parade that I hadn’t seen before, filtering in between Kemp and the rig, and at my sharp exclamation he turned to see for himself and swore.

The army was coming in no half measures. Two recoilless guns, two mortars and two heavy machine guns mounted on appropriate vehicles came forward, followed by a tank and at least two troop carriers. ‘Good God,’ said Kemp in horror, and gave hasty orders to his own driver, who swung us out of the parade and doubled back along the line of military newcomers. Kemp was speaking urgently to Sadiq on the radio.

‘I’ll rejoin after the army vehicles, Captain. I must stay with the rig!’

I grinned at him as he cut the Captain off in mid-sentence.

‘They’re armed to the teeth,’ he said irritably. ‘Why the hell didn’t he warn me about all this?’

‘Maybe the crowds here are rougher than in England,’ I said, looking with fascination at the greatly enhanced parade streaming past us.

‘They’re using us as an excuse to show what they’ve got. They damn well know it’s all going out on telly to the world,’ Kemp said.

‘Enjoy the publicity, Basil. It says Wyvern up there in nice big letters. A pity I didn’t think of a flag with British Electric on it as well.’

In fact this show of military prowess was making me a little uneasy, but it would never do for me to let Kemp see that. He was jittery enough as it was. He gave orders as the tanks swept past, commanders standing up in the turrets, and we swung in behind the last of the army vehicles and just in front of the rig, now massively coupled to all its tractors. Ben Hammond waved down to us from his driving cab and the rig started rolling behind us. Kemp concentrated on its progress, leaving the other Wyvern vehicles to come along in the rear, the very last car being the second Land Rover with John Sutherland on board.

Kemp was watching the rig, checking back regularly and trying to ignore the shouting, waving crowds who were gathering as we went along, travelling so slowly that agile small boys could dodge back and forward across the road in between the various components of the parade. There was much blowing of police whistles to add to the general noise. We heard louder cheering as we came out onto the coastal boulevard leading to the town centre. The scattering of people thickened as we approached.

Kemp paid particular attention as the rig turned behind us into Victory Avenue; turning a 240-foot vehicle is no easy job and he would rather have done it without the extra towing tractors. But the rig itself was steerable from both ends and a crew member was spinning a ship-sized steering wheel right at the rear, synchronizing with Ben Hammond in the front cab. Motorcycle escorts took up flanking positions as the rig straightened out into the broad avenue and the crowd was going crazy.

Kemp said, ‘Someone must have declared a holiday.’

‘Rent-a-crowd,’ I grinned. Kemp sat a little straighter and seemed to relax slightly. I thought that he was beginning to enjoy his moment of glory, after all. The Land Rover bumped over a roughly cobbled area and I realized with a start that we were driving over the place where Ofanwe’s plinth had been only a few days before.

We entered the Square to a sea of black faces and colourful robes, gesticulating arms and waves of sound that surged and echoed from the big buildings all around. The flags hung limply in the still air but all the rest was movement under the hard tropical sun.

‘Jesus!’ Kemp said in awe. ‘It’s like a Roman triumph. I feel I ought to have a slave behind me whispering sweet nothings in my ear.’ He quoted, ‘Memento mori – remember thou must die.’

I grunted. I was used to the British habit of flinging off quotations at odd moments but I hadn’t expected it of Kemp. He went on, ‘Just look at that lot.’

The balcony of the Palace of Justice was full of figures. The President, the Prime Minister, members of the Government, Army staff, some in modern dress or in uniforms but some, like Daondo, changed into local costume: a flowing colourful robe and a tasselled hat. It was barbaric and, in spite of my professed cynicism, a touch magnificent.

The tanks and guns had passed and it was our turn. Kemp said to me, ‘Do we bow or anything?’

‘Just sit tight. Pay attention to your rig. Show them it’s still business first.’ Off to one side of the parade, Sadiq’s staff car was drawn up with the Captain standing rigidly at the salute in the back seat. ‘Sadiq is doing the necessary for all of us.’

The vast bulk of the rig crept slowly across Independence Square and the troops and police fought valiantly to keep the good-humoured crowd back. As soon as our car was through the Square we stopped and waited too for the rig to come up behind us, and then set off again following Sadiq, who had regained his place in the lead. The tanks and guns rumbled off in a different direction, and the convoy with its escort of soldiers crept on through narrower streets and among fewer and fewer people.

The town began to thin out until we were clear of all but a few shanties and into the beginning of the croplands, and here the procession came to a halt, with only an audience of goats and herd boys to watch us.

Sadiq’s car came back. He got out and spoke to Kemp, who had the grace to thank him and to congratulate him on the efficiency of his arrangements. Clearly both were relieved that all had gone so well, and equally anxious to get on with the job in hand. Within minutes Kemp had his men removing the bunting and flags; he was driving them hard while the euphoria of the parade was still with them.

‘This is all arsey-versey,’ I heard him saying. ‘You’ve had your celebration – now do something to earn it.’

‘I suppose they’ll do their celebrating tonight,’ I remarked to him.

Kemp shook his head.

‘We have a company rule. There’s no hard liquor on the journeys: just beer, and I control that. And they’ve got a hell of a few days ahead of them.’

‘I guess they have,’ I said.

‘A lot of trips,’ Kemp said. ‘Months of work. Right now it’s a pretty daunting prospect.’

‘You only have this one rig?’

I still felt I didn’t know as much about Wyvern as I ought to. Having seen a tiny slice of their job out here, I was in a fever to talk to Geddes back at home, and to get together with Wingstead too. Reminded of him, I asked Kemp when he was due to come out.

‘Next week, I believe,’ Kemp said.,’He’ll fly up and join us during the mid-section of the first trip. As for the rig, there’s a second one in the making and it should be ready towards the end of the job. It’ll help, but not enough. And the rains start in a couple of months too: we’ve a lot of planning to do yet.’

‘Can you keep going through the wet season?’

‘If the road holds out we can. And I must say it’s fairly good most of the way. If it hadn’t existed we’d never have tendered for the job.’

I said, ‘I’m frankly surprised in a way that you did tender. It’s a hell of a job for a new firm – wouldn’t the standard European runs have suited you better to begin with?’

‘We decided on the big gamble. Nothing like a whacking big success to start off with.’

I thought that it was Wingstead, rather than the innately conservative Kemp, who had decided on that gamble, and wondered how he had managed to convince my own masters that he was the man for the job.

‘Right, Basil, this is where I leave you,’ I said, climbing down from the Land Rover to stand on the hard heat-baked tarmac. ‘I’ll stay in touch, and I’ll be out to see how you’re getting on. Meanwhile I’ve got a few irons of my own in the fire – back there in the Frying Pan.’

We shook hands and I hopped into John Sutherland’s car for the drive back to Port Luard, leaving Kemp to organize the beginning of the rig’s first expedition.

FOUR (#ulink_781d844c-4fd9-566d-bcf6-c2291d03e5c7)

We got back to the office hot, sweaty and tired. The streets were still seething and we had to fight our way through. Sutherland was fast on the draw with a couple of gin and tonics, and within four minutes of our arrival I was sitting back over a drink in which the ice clinked pleasantly. I washed the dust out of my mouth and watched the bubbles rise.

‘Well, they got away all right,’ Sutherland said after his own first swallow. ‘They should be completely clear by nightfall.’

I took another mouthful and let it fizz before swallowing. ‘Just as well you brought up the business of the plinth,’ I said. ‘Otherwise the rig would never have got into the Square.’

He laughed. ‘Do you know, I forgot all about it in the excitement.’

‘Sadiq damn nearly removed Independence Square. He blew the goddamn thing up at midnight. He may have broken every window in the hotel: I woke up picking bits of plate glass out of my bed. I don’t know who his explosives experts are but I reckon they used a mite too much. You said it wouldn’t be too subtle a hint – well, it was about as subtle as a kick in the balls.’

Sutherland replenished our glasses. ‘What’s next on the programme?’

‘I’m going back to London on the first possible flight. See to it, will you? And keep my hotel room on for me – I’ll be back.’

‘What’s it all about? What problems do you see?’

I said flatly, ‘If you haven’t already seen them then you aren’t doing your job.’ The chill in my voice got through to him and he visibly remembered that I was the troubleshooter. I went on, ‘I want to see your contingency plans for pulling out in case the shit hits the fan.’

He winced, and I could clearly interpret the expressions that chased over his face. I wasn’t at all the cheery, easy-to-get-along-with guy he had first thought: I was just another ill-bred, crude American, after all, and he was both hurt and shocked. Well, I wasn’t there to cater to his finer sensibilities, but to administer shock treatment where necessary.

I put a snap in my voice. ‘Well, have you got any?’

He said tautly, ‘It’s not my policy to go into a job thinking I might have to pull out. That’s defeatism.’

‘John, you’re a damned fool. The word I used was contingency. Your job is to have plans ready for any eventuality, come what may. Didn’t they teach you that from the start?’