Hope

Len Deighton

Bernard Samson returns to Berlin in the second novel in the classic spy trilogy, FAITH, HOPE and CHARITY.Bernard is trying hard to readjust his life in the face of questions about his wife Fiona, and her defection to the East. Is she the brilliant high-flyer that her Department seems to think she is? Or is she a spent force, a wife and mother unwilling or unable to face her domestic responsibilities? Bernard doesn’t know but is determined to find out.Bernard’s boos Dicky Cruyer is certainly not anxious to reveal what he knows, as he jostles for power with Fiona herself in London Central, and takes to the road with Bernard on a mysterious mission to Poland.This reissue includes a foreword from the cover designer, Oscar-winning filmmaker Arnold Schwartzman, and a brand new introduction by Len Deighton, which offers a fascinating insight into the writing of the story.

Cover designer’s note

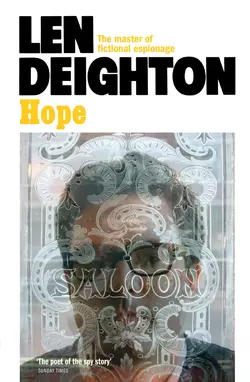

Wishing to continue the notion of Bernard Samson spying through windows or doors, I took the author’s very good suggestion of having the book’s protagonist peering through a glass public house window. I found a perfect example among my collection of photographs that I had taken of windows, this one from a London pub. Combined with the title of this book, Hope, it conjures up the saying “last chance saloon”, in which there is always hope, even for an ageing spy who is on the ropes in both his career and his love life!

For the back cover, I placed a china souvenir of London’s Tower Bridge on a map of divided Berlin and straddled it across the Berlin Wall, which I likened to the River Thames. As readers of this series will by now know, London has exported something – or rather someone – more precious than a souvenir to the Eastern side of the Berlin Wall, and our Bernard still lives in hope of returning them to the West.

At the heart of every one of the nine books in this triple trilogy is Bernard Samson, so I wanted to come up with a neat way of visually linking them all. When the reader has collected all nine books and displays them together in sequential order, the books’ spines will spell out Samson’s name in the form of a blackmail note made up of airline baggage tags. The tags were drawn from my personal collection, and are colourful testimony to thousands of air miles spent travelling the world.

Arnold Schwartzman OBE RDI

Len Deighton

Hope

Copyright

This novel is entirely a work of fiction.

The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

This paperback edition 2011

First published in Great Britain by

HarperCollinsPublishers 1995

HOPE. Copyright © Len Deighton 1995.

Introduction copyright © Pluriform Publishing Company BV 2011.

Cover designer’s note © Arnold Schwartzman 2011. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Len Deighton asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 9780007395750

EBook Edition © MAY 2011 ISBN: 9780007395798

Version: 2017-08-10

Contents

Cover designer’s note

Copyright

Introduction

1

A caller who wakes you in the small dark silent…

2

September is the time many visitors choose to visit Poland.

3

Dicky was silent for much of the time we were…

4

The following day brought no further news of either George…

5

‘You haven’t told me what it’s like in Warsaw these…

6

‘What a lovely idea – to take the children to see…

7

‘Your wife loathes me,’ said Gloria. ‘She won’t be happy…

8

‘Hold on, Bernard, hold on. I’m just a simple old…

9

After my bruising encounter with Theo’s son I went to…

10

I awoke in the middle of the night, bathed in…

11

What Lisl called ‘the flashy new American hotel’ was really…

12

Now Poland was truly in the grip of winter. My…

13

‘Don’t do this to me, Bernard,’ said George.

About the Author

Other Books by Len Deighton

About the Publisher

Introduction

In 1945 Europe was devastated. Food was scarce and bitter hatred was in the air. Parts of France, Belgium, Holland and the western half of Germany was battered but the vast area of land over which the Red Army had advanced was now largely rubble, a barren wasteland where millions of ‘displaced persons’, undernourished, infirm and undocumented, wandered in confusion.

Stalin ordered his Red Army to cling tight to all their gains. His promises made to Prime Minister Churchill and President Roosevelt, that the people of Eastern Europe would be allowed free elections, were ignored. The nations of Eastern Europe became satellites of Russia, ruled by expatriates who had been tutored in Moscow. Red Army soldiers complete with tanks and artillery remained in evidence everywhere.

With American generosity, programs such as the ‘Marshall Plan’ slowly revived the countries of Western Europe. But American hopes for a revised and truly democratic Russian political system faded as Moscow exerted its brutal power at home and abroad. An Iron Curtain had come down between the nations of the West and those in the East, and there was no reconciliation. Russia’s military occupation zone was the eastern half of Germany and its heartless rule was fuelled by memories of the barbaric German violation of the Russian Motherland.

In the summer of 1961 the communists built a wall to surround the Western Sector of Berlin. It was, said Nikita Khrushchev, the Russian Premier, ‘a barrier to Western Imperialism’. Anyone in the East trying to take a closer look at Western Imperialism was likely to be shot. Hundreds were killed in attempts to get to the West and the East German border guards were given commendations and bonus payments for killing escapers.

Situated amid this ocean of repression called the Soviet Zone of Germany there was a small island of capitalism. This was the sector of Berlin that had been assigned to British, American and French control. These three sectors of Berlin covered about 185 square miles and about two million people lived there. Technically it remained a ‘military occupation zone’ where soldiers still made all the important decisions. To get from this British-American-French ‘island’ to ‘West Germany’ traffic was confined to three specific highways, all of them over 100 miles long. Wandering off the approved roads could lead to difficulties. On a journey from Prague to Berlin, I was detained in a Russian Army barrack complex until, in the small hours of morning and with a help of an amiable Russian colonel and my bottle of duty-free cognac, I was released to continue my journey.

Any writer who pins his story to fixed dates had better hold on to his hat for it is likely to be a rough and rocky ride. My whole Bernard Samson series was based upon the belief that the Berlin Wall would fall before the end of the century. There were many times when I went to bed convinced that this assumption had been a reckless gamble, and there were many people asking me where the plot was going. Sometimes I thought I heard a measure of Schadenfreude. More than one expert advised me to forget the Wall, tear my plan down, and radically change its direction. I didn’t yield to my fears. I stuck to my lonely task and to the original scenario and eventually was vindicated.

It is unlikely that the true and complete story of the collapse of the Wall and the whole communist system will ever be told. But the overall pattern is now fairly clear and the signs were there long before the newspapers and the TV camera crews arrived for the finale. The election of Karol Wojtyla to be John Paul II, a Polish Pope, changed the world’s history. Here was a fearless man not afraid to declare that communism was a vile and repressive tyranny that denied the freedom that everyone deserved. His outspoken challenge, unlike those of most politicians, did not vary from time to time and place to place, no matter how unwelcome it was to some of his audiences. His words frightened the dictators, disturbed the apparatchiks, and made Poland’s Catholics into a network of frontline activists. The Polish-American Catholics of Chicago provided a great deal of the money; the CIA added more and worked with the Vatican to route it to Poland’s anti-communist networks. George Kosinski personifies the muddled, almost schizophrenic, mindset of many Poles. His fears and double-dealing provide us with a glimpse of the struggle, and Hope depicts the vital days when the USSR was deciding whether to move with military force against its recalcitrant ally or hold still and hope for the best. Warsaw was deeply in debt to Western banks and Moscow was in no position to pick up the bill. Bernard Samson is in Poland and near the frontier when the Soviet Union was poised and ready to occupy its politically unreliable but strategically essential neighbour. The events depicted here reflect the tension as the Poles waited for the tanks to come rolling westwards.

As Poland’s communist regime was being undermined by the bravery of the Polish Pope, the Lutheran Church in communist Germany became more and more important in the struggle against Moscow. In Hope Bernard’s journeys to the East record the fierce repressive measures the German regime resorted to when it became the final outpost of the communist empire.

Tying a story to events is not something to be undertaken lightly. But having a timescale for the stories provided some benefits. Hope was bountiful: with the astonishing Hurricane that tore a path through London, minor asides such as the Swiss elections and the devastating collapse of the world’s stock exchanges. At the end of the year the Pope and Gorbachev met in the Vatican. What more eventful background could any writer wish for?

I was lucky to find so much of my story in Poland where communism collapsed so suddenly. The attractions of Warsaw are there for anyone to inspect but I was lucky to find the hideous Rozyckiego market so perfect for my purpose. Explorations into the countryside brought me to the Kosinki’s grand old family mansion, a place even more mysterious than I had envisioned. Both places are faithfully described here in the book; there was no need to change a thing. As with many of the research trips I have made for my books I found it very beneficial to return to the location at the season it was to be depicted in my story. The Polish countryside in winter is not to be found in the tourist brochures but despite the discomfort and inconvenience I liked this strange fairy-tale mix of dreams and nightmares.

Every writer has different priorities, which makes reading fiction so rewarding. After the basic idea, my own priority has always been dialogue. From dialogue characterization must follow and from characterization comes motivation and plot. For all of the above reasons I try to inform the reader by dialogue and, when I read and reread the drafts of my books prior to publication, I search for ways of transforming authorial comment and description into dialogue.

At a creative writing school in California the students read (and enjoyed) studying the Bernard Samson books in reverse order. They noted and analyzed the changing character of Bernard and were kind enough to show me some of the results. By assigning various specific fictional characters to student teams the class unravelled the complex weave of the plot. Even without such close examination most readers immediately see that Bernard – without telling outright lies – is inclined to bend the truth to his own advantage.

But dialogue and characterization is more important than truth and plot. The purpose of characterization is to demonstrate the changes that take place as the story proceeds. I consider this process vital. Whether the time span is short as it is in Bomber (when there is only 24 hours from cover to cover) or long as in Winter (a family story lasting half a century) the characters must be seen to change, and that means to change in response to the events of the story. The Bernard Samson books take the characters through several years and the man we join in the first chapter of this book, Hope, is older, wiser and more psychologically battered than the man in the first book, Berlin Game. But Bernard, whatever his shortcomings, is always a loyal friend to us.

Len Deighton, 2011

1

Mayfair, London. October 1987.

A caller who wakes you in the small dark silent hours is unlikely to be a bringer of good news.

When the buzzer sounded a second time I reluctantly climbed out of bed. I was at home alone. My wife was at her parents’ with our children.

‘Kosinski?’

‘No,’ I said.

The overhead light of the hallway shone down upon a thin, haggard man in a short waterproof flight-jacket and a navy-blue knitted hat. In one hand he was carrying a cheap briefcase of the sort that every office worker in Eastern Europe flaunts as a status symbol. The front of his denim shirt was bloody and so was his stubbly face, and the outstretched hand in which he held the key to my apartment. ‘No,’ I said again.

‘Please help me,’ he said. I guessed his command of English was limited. I couldn’t place the accent but his voice was muffled and distorted by the loss of some teeth. That he’d been badly hurt was evident from his hunched posture and the expression on his face.

I opened the door. As he tottered in he rested his weight against me, as if he’d expended every last atom of energy in getting to the doorbell and pressing it.

He only got a few more steps before twisting round to slump on to the low hall table. There was blood everywhere now. He must have read my mind for he said: ‘No. No blood on the stairs.’

He’d taken the stairs rather than the lift. It was the choice of experienced fugitives. Lifts in the small hours make the sort of sound that wakens janitors and arouses security men. ‘Kosinski,’ he said anxiously. ‘Who are you? This is Kosinski’s place.’ If he had been a bit stronger he might have been angry.

‘I’m just a friendly burglar,’ I explained.

I got him back on his feet and dragged him to the bathroom and to the tub. He rolled over the edge of it until he was full length in the empty bath. It was better that he bled there. ‘I’m Kosinski’s partner,’ he said.

‘Sure,’ I said. ‘Sure.’ It was a preposterous claim.

I got his jacket off and pushed him flat to open his shirt. I could see no arterial bleeding and most of the blood was in that tacky congealed state. There were a dozen or more deep cuts on his hands and arms where he had deflected the attack, but it was the small stab wounds on his body that were the life-threatening ones. Under his clothes he was wearing a moneybelt. It had saved him from the initial attack. It wasn’t the sort of belt worn by tourists and backpackers, but the heavy-duty type used by professional smugglers. Almost six inches wide, it was made of strong canvas that from many years of use was now frayed and stained and bleached to a light grey colour. The whole belt was constructed of pockets that would hold ingots of the size and shape of small chocolate bars. Now it was entirely empty. Loaded it would have weighed a ton, for which reason there were two straps that went over the shoulders. It was one of these shoulder straps that had no doubt saved this man’s life, for there was a fresh and bloody cut in it. A knife-thrust had narrowly missed the place where a twisted blade floods the lungs with blood and brings death within sixty seconds.

‘Just a scratch,’ I said. He smiled. He knew how bad it was.

To my astonishment George Kosinski, my brother-in-law, arrived five minutes later. George who had left England never to return was back! I suppose he’d been trying to head off my visitor, for he showed little surprise to find him there. George was nearly forty years old, his wavy hair greying at the temples. He took off his glasses. ‘I came by cab, Bernard. A car will arrive any minute and I’ll take this fellow off your hands.’ He said it as casually as if he were the owner of a limousine service. Then he took out a handkerchief and began rubbing the condensation from his thick-rimmed glasses.

‘He loses consciousness and then comes back to life,’ I said. ‘He urgently needs attention. He’s lost a lot of blood; he could die any time.’

‘And you don’t want him to die here,’ said George, putting his glasses on and looking at the comatose man in the bathtub. His eyes were tightly closed and his breathing slow, and with the sort of snoring noise that sometimes denotes impending death. George looked at me and said: ‘I’m taking him to a Polish doctor in Kensington. He’s expected there. He’ll relax and trust someone who can talk his language.’ George moved into the drawing-room, as if he didn’t want to think about the man expiring in my bathtub.

‘It’s internal bleeding, George. I think he’s dying.’

This prognosis showed no effect on George. He went to the window and looked down at the street as if hoping to see the car arrive. I think it was done to reassure me rather than because he really thought he’d see the promised car. George was Polish by extraction and a Londoner by birth. He was not handsome or charming but he was direct in manner and unstinting in his generosity. Like most self-made men he was intuitive, and like most rich ones, cynical. Many of the men he did deals with, and the ones who sat alongside him on his charity committees, were Poles, or considered themselves as such. George went out of his way to be sociable with Poles, but he was a man of many moods. Where his supporters found a cheerful self-confidence others encountered a stubborn ego. And when his mask slipped a little, his energetic impatience could become raging bad temper.

Now I watched him marching backwards and forwards and around the room, flapping the long vicuna overcoat, or cracking the bones of his knuckles, and displaying that kind of restless energy that some claim is part of the process of reasoning. His face was clenched in anger. You wouldn’t have recognized him as a man grieving for his desperately loved wife. Neither would you have thought that this apartment had been until recently his own home, for he blundered against the chairs, kicked his polished brogues at the carpets and fumed like a teetotaller held on a drunk-driving charge.

‘He had nowhere to go,’ said George.

‘You’re wrong,’ I said, waving the key at him. ‘He had a key to this apartment. He tried the doorbell only to discover if it was clear.’

George scowled. ‘I thought I’d called in all the keys. But perhaps you’d better have the locks changed, just to be on the safe side.’ He lifted his eyes quickly, caught the full force of the annoyance on my face and added: ‘They can’t just walk the streets, Bernard.’

‘Why not? Because they’re illegals? Because they don’t have papers or passports or visas? Is that what you mean?’ I put the key in my pocket and resolved to change the locks just as soon as I could get someone along here to do it. ‘Damn you, George, don’t you have any consideration for me or Fiona? She’ll be furious if she hears about this.’

‘Must you tell her?’

‘She’ll see the blood on the mat in the hall.’

‘I’ll send someone round to clean up.’

‘I’m the world’s foremost expert on cleaning blood marks off the floor,’ I said.

‘Then get a new mat,’ he said with exasperation, as if I was capriciously making problems for him.

‘I can’t think of anything more likely to excite Fiona’s suspicions than me going out to buy a new mat.’

‘So confide in her. Ask her to keep it to herself.’

‘It wouldn’t be fair to ask her. Fiona is big brass in the Department nowadays. And anyway she wouldn’t agree. She’d report it. She prefers doing things by the book, that’s how she got to the top.’

George stopped pacing and went to take a brief look at the man in the bath, who was even paler than before, although his breathing was marginally easier. ‘Don’t make problems for me, Bernard,’ he said in an offhand manner that angered me.

‘My employers…’ I stopped, counted to ten and started again. More calmly I said: ‘The sort of people who run the Secret Service have old-fashioned ideas about East European escapers having the doorkey to their employees’ homes.’

George put on his conciliatory hat. ‘I can see that. It was a terrible mistake. I’m truly sorry, Bernard.’ He patted my shoulder. ‘That means you will have to report it, eh?’

‘You’re playing with fire, George.’ I wondered if perhaps the death of his wife, Tessa, had turned his brain.

‘It’s simply that I’m not supposed to be in this jurisdiction: tax-wise. I’m in the process of losing residence. Just putting it around that I’ve been in England could cause me a lot of trouble, Bernard.’

I noted the words – jurisdiction, tax-wise. Only men like George had a call on words like that. ‘I know what you’re doing, George. You’re asking some of these roughnecks to investigate the death of your wife. That could lead to trouble.’

‘They are Poles – my people. I have to do what I can for them.’ His claim sounded hollow when pitched in that unmistakable East London accent.

‘These people can’t bring her back, George. No one can.’

‘Stop preaching at me, Bernard, please.’

‘Listen, George,’ I said, ‘your friend next door isn’t just a run-of-the-mill victim of a street mugging or a fracas in a pub. He was attacked by a professional killer. Whoever came after him was aiming his blade for an artery and knew exactly where to find the place he wanted. Only the canvas moneybelt saved him, and that was probably because it was twisted across his body at the time. I think he’s dying. He should be in an intensive-care ward, not on his way to a cosy old family doctor in Kensington. Believe me, these are rough playmates. Next time it could be you.’

I had rather hoped that this revelation might bring George to his senses, but he seemed quite unperturbed. ‘Many of these poor wretches are on the run, Bernard,’ he said cheerfully. ‘Nothing in the belt, was there? And yes, you’re right. It’s inevitable that the regime infiltrates their own spies. Black-market gangsters and other violent riffraff use our escape line. We screen them all but it takes time. This one was doubly unlucky; a really nice youngster, he wanted to help. If you could see some of the deserving cases. The youngsters… It’s heart-breaking.’

‘I can’t tell you how to run your life, George. I know you’ve always contributed generously to Polish funds and good causes for these dissidents and political refugees. But the communist government in Warsaw sees such overseas organizations as subversive. You must know that. And there is a big chance that you are being exploited by political elements without understanding what you’re doing.’

George rubbed his face. ‘He’s hurt bad, you think?’ He stroked the telephone.

‘Yes, George, bad.’

His face stiffened and he picked up the phone and called some unknown person, presumably to hurry things along. When there was no answer to his call he looked at me and said: ‘This won’t happen again, Bernard. I promise you that.’ He waited only a few minutes before trying his number again and got the busy signal. He crashed the phone down with such force that it broke. I had been crashing phones down into their cradles for years but I’d never broken one. Was it a measure of his anger, his grief, his embarrassment, or something else? He held up his hands in supplication, looked at me and smiled.

I sighed. No man chooses his brother-in-law. They are strangers society thrusts upon us to test the limits of our compassion and forbearance. I was lucky, I liked my brother-in-law; more perhaps than he liked me. That was the trouble; I liked George.

‘Look, George,’ I said in one final attempt to make him see sense. ‘To you it’s obvious that you’re not an enemy agent – just a well-meaning philanthropist – but don’t rely upon others being so perceptive. The sort of people I work for think that there is no smoke without fire. Cool it. Or you are likely to find a fire-extinguisher up your arse.’

‘I live in Switzerland,’ said George.

‘So a Swiss fire-extinguisher.’

‘I told you I’m sorry, Bernard. You know I wouldn’t have had this happen for the world. I can’t blame you for being angry. In your place I would be angry too.’ Both his arms were clasped round the cheap briefcase as if it was a baby. I suddenly guessed that it was stuffed with money; money that had come from the exchange of the gold.

At that I gave up. There are some people who won’t learn by good advice, only by experience. George Kosinski was that sort of person.

Soon after that a man I recognized as George’s driver and handyman arrived. He brought a car rug to wrap around the injured man and lifted him with effortless ease. George watched as if it was his own sick child. Perhaps it was pain that caused the injured man’s eyes to flicker. His lips moved but he didn’t speak. Then he was carried down to the car.

‘I’m sorry, Bernard,’ said George, standing at the door as if trying to be contrite. ‘If you have to report it, you have to. I understand. You can’t risk your job.’

I cleaned the mat as well as possible, got rid of the worst marks in the bathroom and soaked a bloody towel in cold water before sending it to the laundry. In my usual infantile fashion, I decided to wait and see if Fiona noticed any of the marks. As a way of making an important decision it was about as good as spinning a coin in the air, but Fiona had eyes for little beyond the mountains of work she brought home every evening, so I didn’t mention my uninvited visitors to anyone. But my hopes that George and his antics were finished and forgotten did not last beyond the following week, when I returned from a meeting and found a message on my desk summoning me to the presence of my boss Dicky Cruyer, newly appointed European Controller.

I opened the office door. Dicky was standing behind his desk, twisting a white starched handkerchief tight around his wounded fingers, while half a dozen tiny drips of blood patterned the report he had brought back from his meeting.

There was no need for him to explain. I’d been on the top floor and heard the sudden snarling and baritone growls. The only beast permitted through the guarded front entrance of London Central was the Director-General’s venerable black Labrador, and it only came when accompanied by its master.

‘Berne,’ said Dicky, indicating the papers freshly arrived in his tray. ‘The Berne office again.’

I put on a blank expression. ‘Berne?’ I said. ‘Berne, Switzerland?’

‘Don’t act the bloody innocent, Bernard. Your brother-in-law lives in Switzerland, doesn’t he?’ Dicky was trembling. His sanguinary encounter with the Director-General and his canine companion had left him wounded in both body and spirit. It made me wonder what condition the other two were in.

‘I’ve never denied it,’ I said.

The door to the adjoining office opened. Jennifer, the youngest, most devoted and attentive of Dicky’s female assistants, put her head round the door and said: ‘Shall I get antiseptic from the first-aid box, Mr Cruyer?’

‘No,’ said Dicky in a stagy whisper over his shoulder, vexed that word of his misfortune had spread so quickly. ‘Well?’ he said, turning to me again.

I shrugged. ‘We all have to live somewhere.’

‘Four Stasi agents pass through in seven days? Are you telling me that’s just a coincidence?’ A pensive pause. ‘They went to see your brother-in-law in Zurich.’

‘How do you know where they went?’

‘They all went to Zurich. It’s obvious, isn’t it?’

‘I don’t know what you’re implying,’ I said. ‘If the Stasi want to talk to George Kosinski they don’t have to send four men to Zurich; roughnecks that even our pen-pushers in Berne can recognize. I mean, it’s a bit high-profile, isn’t it?’

Dicky looked round to see if Jennifer was still standing in the doorway looking worried. She was. ‘Very well, then,’ he said, sitting down suddenly as if surrendering to his pain. ‘Get the antiseptic.’ The door closed and, as he tightened the handkerchief round his fingers, he noticed the bloodstains on his papers.

‘You should have an anti-tetanus shot,’ I advised. ‘That dog is full of fleas and mange.’

Dicky said: ‘Never mind the dog. Let’s keep to the business in hand. Your brother-in-law is in contact with East German intelligence, and I’m going over there to face him with it.’

‘When?’

‘This weekend. And you are coming with me.’

‘I have to finish all that material you gave me yesterday. You said the D-G wanted the report on his desk on Monday.’

Dicky eyed me suspiciously. We both knew that he recklessly used the name of the Director-General when he wanted work done hurriedly or late at night. ‘He’s changed his mind about the report. He told me to take you to Switzerland with me.’

Now it was possible to see a little deeper into Dicky’s state of mind. The questions he had just put to me were questions he’d failed to answer to the D-G’s satisfaction. The Director had then told Dicky to take me along with him, and it was that that had dented Dicky’s ego. The nip from the dog was extracurricular. ‘Because it’s your brother-in-law,’ he added, lest I began to think myself indispensable.

Using his uninjured hand Dicky picked up his phone and called Fiona, who worked in the next office. ‘Fiona, darling,’ he said in his jokey drawl. ‘Hubby is with me. Could you join us for a moment?’

I went and looked out of the window and tried to forget I had a crackpot brother-in-law in whom Dicky was taking a sudden and unsympathetic interest. Summer had passed; we had winter to endure before it came again but this was a glorious golden day, and from this top-floor room I could see across the London basin to the high ground at Hampstead. The clouds, gauzy and grey like a bundle of discarded bandages, were fixed to the ground by shiny brass pins pretending to be sunbeams.

My wife came in, her face darkened with the stern expression that I’d learned to recognize as one she wore when wrenched away from something that needed uninterrupted concentration. Fiona’s work load had become the talk of the top floor. And she handled the political decisions with consummate skill. But I saw in her eyes that bright gleam a light bulb provides just before going ping.

‘Yes, Dicky?’ she said.

‘I’m enticing your hubby away for a brief fling in Zurich, Fiona my dearest. We must leave Sunday morning. Can you endure a weekend without him?’

Fiona looked at me sternly. I winked at her but she didn’t react. ‘Must he go?’ she said.

‘Duty calls,’ said Dicky.

‘What did you do to your hand, Dicky?’

As if in response, Jennifer arrived with antiseptic, cotton wool and a packet of Band-Aids. Dicky held his hand out like some potentate accepting a vow of fidelity. Jennifer crouched and began work on his wound.

‘The children were coming home on Sunday,’ Fiona told Dicky. ‘But if Bernard is going to be on a trip, I’ll lock myself away and work on those wretched figures you need for the Minister.’

‘Splendid,’ said Dicky. ‘Ouch, that hurts,’ he told Jennifer.

‘I’m sorry, Mr Cruyer.’

To me Fiona said: ‘Daddy suggests keeping the children with him a little longer.’ Perhaps she saw the quizzical look in my face for, in explanation, she added: ‘I phoned them this morning. It’s their wedding anniversary.’

‘We’ll talk about it,’ I said.

‘I’ve told Daddy to reserve places for them at the school next term, just in case.’ She clasped her hands together as if praying that I would not explode. ‘If we lose the deposit, so be it.’

For a moment I was speechless. Her father was doing everything he could to keep my children with him, and I wanted them home with us.

Dicky, feeling left out of this conversation, said: ‘Has Daphne been in touch, by any chance?’

This question about his wife was addressed to Fiona, who looked at him and said: ‘Not since I called and thanked her for that divine dinner party.’

‘I just wondered,’ said Dicky lamely. With Fiona looking at him and waiting for more, he added: ‘Daph’s been a bit low lately; and there are no friends like old friends. I told her that.’

‘Shall I call her?’

‘No,’ said Dicky hurriedly. ‘She’ll be all right. I think she’s going through the change of life.’

Fiona grinned. ‘You say that every time you have a tiff with her, Dicky.’

‘No, I don’t,’ said Dicky crossly. ‘Daphne needs counselling. She’s making life damned difficult right now. And with all the work piled up here I don’t need any distractions.’

‘No,’ said Fiona, backing down and becoming the loyal assistant. Now that Dicky had manoeuvred himself into being the European Controller, while still holding on to the German Desk, no one in the Department was safe from his whims and fancies.

Dicky said: ‘Work is the best medicine. I’ve always been a workaholic; it’s too late to change now.’

Fiona nodded and I looked out of the window. There was really no way to respond to this amazing claim by the Rip Van Winkle of London Central, and if I’d caught her eye we might both have rolled around on the floor with merriment.

We stayed at home that evening, eating dinner I’d fetched from a Chinese take-away. Fulham was too far to go for shrivelled duck and plastic pancakes but Fiona had read about it in a magazine at the hairdresser’s. That restaurant critic must have led the dullest of lives to have found the black bean spare-ribs ‘memorable’. The bill might have proved even more memorable for him, had restaurant critics been given bills.

‘You don’t like it?’ Fiona said.

‘I’m full.’

‘You’ve eaten hardly anything.’

‘I’m thinking about my trip to Zurich.’

‘It won’t be so bad.’

‘With Dicky?’

‘Dicky depends upon you, he really does,’ she said, her feminine reasoning making her think that this dependence would encourage me to overlook his faults for the sake of the Department.

‘No more rice, no more fish and no more pancakes,’ I said as she pushed the serving plates towards me. ‘And certainly no more spare-ribs.’

Fiona switched on the TV to catch the evening news. There was a discussion between four people best known for their availability to appear on TV discussion programmes. A college professor was holding forth on the latest news from Poland. ‘…Historically the Poles lack a consciousness of their own position in the European dimension. For hundreds of years they have acted out a totemic role that they lack the capacity to sustain. Now I think the Poles are about to get a rude awakening.’ The professor touched his beard reflectively. ‘They have pushed and provoked the Soviet Union… The Warsaw Pact autumn exercises are taking place along the border. Any time now the Russian tanks will roll across it.’

‘Literally?’ asked the TV anchor man.

‘It is time the West acted,’ said a woman with a Polish Solidarity badge pinned to her Chanel suit.

‘Yes, literally,’ said the professor with that determined solemnity with which those past military age discuss war. ‘The Soviets will use it as a way of cautioning the hotheads in the Baltic States. We must make it absolutely clear to Chairman Gorbachev that any action, I do mean any action, he takes against the Poles will not be permitted to provoke a major East–West conflict.’

‘Who will rid me of these troublesome Poles? Is that how the Americans see it?’ the Solidarity woman asked bitterly. ‘Best abandon the Poles to their fate?’

‘When?’ said the TV anchor man. Already the camera was tracking back to show that the programme was ending. A gigantic Polish eagle of polystyrene on a red and white flag formed the backdrop to the studio.

‘When the winter hardens the ground enough for their modern heavy armour to go in,’ answered the professor, who clearly knew that a note of terror heard on the box in the evening was a newspaper headline by morning. ‘They’ll crush the Poles in forty-eight hours. The Russian army has one or two special Spetsnaz brigades that have been trained to suppress unruly satellites. One of them, stationed at Maryinagorko in the Byelorussian Military District, was put on alert two days ago. Yes, Polish blood will flow. But quite frankly, if a few thousand Polish casualties are the price we pay to avoid World War Three, we must thank our lucky stars and pay up.’

Loud stirring music increased in volume to eventually drown his voice and, while the panel sat in silhouette, a roller provided details of about one hundred and fifty people who had worked on this thirty-minute unscripted discussion programme.

The end roller was still going when the phone rang. It was my son Billy calling from my father-in-law’s home where he was staying. ‘Dad? Is that you, Dad? Did Mum tell you about the weekend?’

‘What about the weekend?’ I saw Fiona frowning as she watched me.

‘It’s going to be super. Grandad is taking us to France,’ said Billy, almost bursting with excitement. ‘To France! Just for one night. A private plane to Dinard. Can we go, Dad? Say yes, Dad. Please.’

‘Of course you can, Billy. Is Sally keen to go?’

‘Of course she is,’ said Billy, as if the question was absurd. ‘We are going to stay in a château.’

‘I’ll see you the following weekend then,’ I said as cheerfully as I could manage. ‘And you can tell me all about it.’

‘Grandad’s bought a video camera. He’s going to take pictures of us. You’ll be able to see us. On the TV!’

‘That’s wonderful,’ I said.

‘He’s already taken videos of his best horses. Of course I’d rather be with you, Dad,’ said Billy, desperately trying to mend his fences. Perhaps he heard the disappointment.

‘All the world’s a video,’ I improvised. ‘And all the men and women merely directors. They have their zooms and their pans, and one man in his time plays back the results too many times. Is Sally there?’

‘That’s a good joke,’ said Billy with measured reserve. ‘Sally’s in bed. Grandad is letting me stay up to see the TV news.’ Fiona had quietened our TV, but over the phone from Grandad’s I could hear the orchestrated fanfares and drumrolls that introduce the TV news bulletins; a presentational style that Dr Goebbels created for the Nazis. I visualized Grandad fingering the volume control and urging our conversation to a close.

‘Sleep well, Billy. Give my love to Sally. And to Grandad and Grandma.’ I held up the phone, offering it, but Fiona shook her head. ‘And love from Mummy too,’ I said. Then I hung up.

‘It’s not my doing,’ said Fiona defensively.

‘Who said it was?’

‘I can see it on your face.’

‘Why can’t your father ask me?’

‘It will be lovely for them,’ said Fiona. ‘And anyway you couldn’t have gone on Sunday.’

‘I could have gone on Saturday.’ The silent TV pictures changed rapidly as the news flashed quickly from one calamity to another.

‘It wasn’t my idea,’ she snapped.

‘I don’t see why I should be the focus of your anger,’ I said mildly. ‘I’m the victim.’

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘You’re always the victim, Bernard. That’s what makes you so hard to live with.’

‘What then?’

She got up and said: ‘Let’s not argue, darling. I love the children just as much as you do. Don’t keep putting me in the middle.’

‘But why didn’t you tell me?’ I said.

‘Daddy is so worried. The stock-market has become unpredictable, he says. He doesn’t know what he’ll be worth next week.’

‘For him that’s new? For me it’s always been like that.’

This aggravated her. ‘With you on one side and my father on the other, sometimes I just want to scream.’

‘Scream away,’ I said.

‘I’m tired. I’ll clean my teeth.’ She rose to her feet and put everything she had into a smile. ‘Tomorrow we’ll have lunch, and fight all you want.’

‘Lovely! And I’ll arm-wrestle the waiter to settle the bill,’ I said. ‘Switch off that bloody TV, will you?’

She switched it off and went to bed leaving the desolation of our meal still on the table. Sitting there staring at the blank screen of the TV I found myself simmering with anger at the way my father-in-law was holding on to my children. But was Fiona fit and well enough to be a proper mother to them? Perhaps Fiona would remain incapable of looking after them. Perhaps she knew that. And perhaps my awful father-in-law knew it. Perhaps I was the only one who couldn’t see the tragic situation for what it really was.

I woke up in the middle of the night. The windows shook and the wind was howling and screaming as I’d never heard it shriek before in England. It was like a nightmare from which there was no escape, and I was an expert in nightmares. From somewhere down below in the street I heard a loud crash of glass and then another and another, resounding like surf upon a rocky shore.

‘My God!’ said Fiona sleepily. ‘What on earth…?’

I switched on the bedside light but there was no electricity. I heard clicking as Fiona tried her light-switch too. The electric bedside clock was dark. I threw back the bedclothes and, stepping carefully in the darkness, went to the window. The street lighting had failed and everything was gloomy. Two police cars were stopped close together behind a fire engine, and a group of men were conferring outside the smashed windows of the bank on the corner. They ducked their heads as a great roar of wind brought the sound of more breaking glass, and debris – newspapers and the lids of rubbish bins – came bowling along the street. I heard the distant sirens of police cars and fire engines going down Park Lane at high speed.

‘Phone the office,’ I told Fiona, handing her the flashlight that I keep in the first-aid box. ‘Use the Night Duty Officer’s direct line. Ask them what the hell’s going on. I’ll try to see what’s happening in the street.’

With the window open I could lean out and look along the street. The garbage bins had been blown over, shop-windows broken, and merchandise of all kinds was distributed everywhere: high-fashion shoes mixed with groceries and rubbish, with fragments of paper and packets being whirled high into the air by the wind. There were tree branches too: thousands of twigs as well as huge boughs of leafy timber that must have flown over the rooftops from the park. Some of them were heaving convulsively in the continuing windstorm, like exhausted birds resting after a long flight. Fragmented glass was dashed across the road, glittering like diamonds in the beams of the policemen’s flashlights.

I could hear Fiona moving around in the kitchen, then the gush of running water and the plop of igniting gas as she boiled a kettle for tea.

When she came back into the room she came to the window, putting a hand on my arm as she peered over my shoulder. She said: ‘The office says there are freak windstorms gusting over 100 miles an hour. It’s a disaster. The whole Continent is affected. The forecasters in France and Holland gave out warnings but our weather people said it wasn’t going to happen. Heavens, look at the broken shop-windows.’

‘This might be your big chance for a new Chanel suit.’

‘Will there be looting?’ she asked, as if I was some all-knowing prophet.

‘Not too much at this time of night. Black up your face and put on your gloves.’

‘It’s not funny, darling. Shall I phone Daddy?’

‘It will only alarm them more. Let’s hope they sleep through it.’

She poured tea for us both and we sat there, with only a glimmer of light from the window, drinking strong Assam tea and listening to the noise of the storm. Fiona was very English. The English met every kind of disaster, from sudden death to threatened invasions, by making tea. Growing up in Berlin I had never acquired the habit. Perhaps that was at the root of our differences. Fiona had a devout faith in England, a legacy of her middle-class upbringing. Its rulers and administration, its history and even its cooking was accepted without question. No matter how much I tried to share such deeply held allegiances I was always an outsider looking in.

‘I’ve got a long day tomorrow, so I’m going right back to bed.’ She lifted her cup and drained the last of her tea. I noticed the cup she was using was from a set I’d bought when I set up house with Gloria. I’d tried to dispose of everything that would bring back memories of those days, but I’d forgotten about the big floral-pattern cups.

Gloria’s name was never mentioned but her presence was permanent and all-pervading. Would Fiona ever forgive me for falling in love with that glamorous child? And would I ever be able to forgive Fiona for deserting me without warning or trust? Our marriage had survived by postponing such questions, but eventually it must be tested by them.

‘Me too,’ I said.

Fiona put her empty cup on the tray and reached for mine. ‘You haven’t touched your tea,’ she said. She knew about the cups of course. Women instinctively know everything about other women.

‘It keeps me awake.’ Not that there was much of the night remaining to us.

‘You’re not easy to live with, Bernard,’ she said, with a formality that revealed that this was something she’d told herself many times.

‘I was thinking about something else,’ I confessed. ‘I’m sorry.’

‘You can’t wait to get away,’ she said, as if taking note of something beyond her control, like the storm outside the window.

‘It’s Dicky’s idea.’

‘I didn’t say it wasn’t.’ She stood up and gathered the sugar and milk jug, and put them on the tray.

‘I’d rather stay with you,’ I said.

She smiled a lonely distant smile. Her sadness almost broke my heart. I was going to stand up and embrace her, but while I was still thinking about it she had picked up the tray and walked away. In such instants are our lives changed; or not changed.

With characteristic gravity the news men made the high winds of October 1987 into a hurricane. But it was a newsworthy event nevertheless. Homes were wrecked and ships sank. Cameras turned. The insured sweated; underwriters faltered; glaziers rejoiced. Hundreds and thousands of trees were ripped out of the English earth. So widespread was the devastation that even the meteorological gurus were moved to admit that they had perhaps erred in their predictions for a calm night.

I contrive, as far as is possible considering our relative ranking in the Department, to make my travel arrangements so that they exclude Dicky Cruyer. Several times during our trip to Mexico City a few years ago, I had vowed to resign rather than share another expedition with him. It was not that he made a boring travelling companion, or that he was incapable, cowardly, taciturn or shy. At this moment, he was practising his boyish charm on the Swiss Air stewardess in a demonstration of social skill far beyond anything that I might accomplish. But Dicky’s intrepid behaviour and reckless assumptions brought dangers of a sort I was not trained to endure. And I was tired of his ongoing joke that he was the brains and I was the brawn of the combination.

It was a Monday morning in October in Switzerland. Birds sang to keep warm, and the leaves were turning to rust on dry and brittle branches. The undeclared reason for my part in this excursion was that I knew the location of George Kosinski’s lakeside hideaway near Zurich. It was a secluded spot, and George had an obsession about keeping his name out of phone books and directories.

It was a severely modern house. Designed with obvious deference to the work of Corbusier, it exploited a dozen different woods to emphasize a panelled mahogany front door and carved surround. There was no reply to repeated ringing, and Dicky said flippantly: ‘Well, let’s see how you knock down the door, Bernard… Or do you pick the lock with your hairpin?’

Across the road a man in coveralls was painstakingly removing election posters from a wall. The national elections had taken place the previous day but already the Swiss were clearing away the untidy-looking posters. I smiled at Dicky. I wasn’t going to smash down a door in full view of a local municipal employee, and certainly not the sort of local municipal employee found in law-abiding Switzerland. ‘George might be having an afternoon nap,’ I said. ‘He’s retired; he takes life slowly these days. Give him another minute.’ I pressed the bell push again.

‘Yes,’ said Dicky knowingly. ‘There are few worse beginnings to an interview than smashing down someone’s front door.’

‘That’s it, Dicky,’ I said in my usual obsequious way, although I knew many worse beginnings to interviews, and I had the scars and stiff joints to prove it. But this wasn’t the time to burden Dicky with the adversities of being a field agent.

‘Our powwow might be more private if we all take a short voyage around the lake in his power boat,’ said Dicky.

I nodded. I’d noted that Dicky was nautically attired with a navy pea-jacket and a soft-topped yachtsman’s cap. I wondered what other aspects of George’s lifestyle had come to his attention.

‘And before we start, Bernard,’ he said, putting a hand on my arm, ‘leave the questioning to me. We’ve not come here for a cosy family gathering, and the sooner he knows that the better.’ Dicky stood with both hands thrust deep into the slash pockets of his pea-jacket and his feet well apart, the way sailors do in rough seas.

‘Whatever you say, Dicky,’ I told him, but I felt sure that if Dicky went roaring in with bayonets fixed and sirens screaming, George would display a terrible anger. His Polish parents had provided him with that prickly pride that is a national characteristic and I knew from personal experience how obstinate he could be. George had started as a dealer in unreliable motor cars and derelict property. Having contended with the ferocious dissatisfied customers found in run-down neighbourhoods of London, he was unlikely to yield to Dicky’s refined style of Whitehall bullying.

Again I pressed the bell push.

‘I can hear it ringing,’ said Dicky. There was a brass horseshoe door-knocker. Dicky gave it a quick rat-a-tat.

When there was still no response I strolled around the back of the house, its shiny tiles and heavy glass well suited to the unpredictable winds and weather that came from the lake. From the house well-kept grounds stretched down to the lakeside and the pier where George’s powerful cabin cruiser was tied up. Summer had ended, but today the sun was bright as it darted in and out of granite-coloured clouds that stooped earthward and became the Alps. The air was whirling with dead leaves that settled on the grass to make a scaly bronze carpet. There was a young woman standing on the lawn, ankle-deep in dead leaves. She was hanging out clothes to dry in the cold blustery wind off the lake.

‘Ursi!’ I called. I recognized her as my brother-in-law’s housekeeper. Her hair was straw-coloured and drawn back into a tight bun; her face, reddened by the wind, was that of a child. Standing there, arms upstretched with the laundry, she looked like the sort of fresh peasant girl you see only in pre-Raphaelite paintings and light opera. She looked at me solemnly for a moment before smiling and saying: ‘Mr Samson. How good to see you.’ She was dressed in a plain dark blue bib-front dress, with white blouse and floppy collar. Her frumpy low-heel shoes completed the sort of ensemble in which Switzerland’s wealthy immigrants dress their domestic servants.

‘I’m looking for Mr Kosinski,’ I said. ‘Is he at home?’

‘Do you know, I have no idea where he has gone,’ she said in her beguiling accent. Her English was uncertain and she picked her words with a slow deliberate pace that deprived them of accent and emotion.

‘When did he leave?’

‘Again, I cannot tell you for sure. The morning of the day before yesterday – Saturday – I drove the car for him; to take him on visits in town.’ Self-consciously she tucked an errant strand of hair back into place.

‘You drove the car?’ I said. ‘The Rolls?’ I had seen Ursi drive a car. She was either very short-sighted or reckless or both.

‘The Rolls-Royce. Yes. Twice I was stopped by the police; they could not believe I was allowed to drive it.’

‘I see,’ I said, although I didn’t see any too clearly. George had always been very strict about allowing people to drive his precious Rolls-Royce.

‘In downtown Zurich, Mr Kosinski asks me to drive him round. It is very difficult to park the cars.’

‘Yes,’ I said. I hadn’t realized how difficult.

‘Finally I left him at the airport. He was meeting friends there. Mr Kosinski told me to take… to bring…’ She gave a quick breathless smile. ‘…the car back here, lock it in the garage, and then go home.’

‘The airport?’ said Dicky. He whisked off his sun-glasses to see Ursi better.

‘Yes, the airport,’ she said, looking at Dicky as if noticing him for the first time. ‘He said he was meeting friends and taking them to lunch. He would be drinking wine and didn’t want to drive.’

‘What errands?’ I said.

‘What time did you arrive at the airport?’ Dicky asked her.

‘This is Mr Cruyer,’ I said. ‘I work for him.’

She looked at Dicky and then back at me. Without changing her blank expression she said: ‘Then I arrived here at the house this morning at my usual hour; eight-thirty.’

‘Yes, yes, yes. And bingo – he was gone,’ added Dicky.

‘And bingo – he was gone,’ she repeated in that way that students of foreign languages pounce upon such phrases and make them their own. ‘And he was gone. Yes. His bed not slept upon.’

‘Did he say when he was coming back?’ I asked her.

A look of disquiet crossed her face: ‘Do you think he goes back to his wife?’

Do I think he goes back to his wife! Wait a minute! My respect for George Kosinski’s ability to keep a secret went sky-high at that moment. George was in mourning for his wife. George had come here, to live full-time in this luxurious holiday home of his, only because his wife had been murdered in a shoot-out in East Germany. And his pretty housekeeper doesn’t know that?

I looked at her. On my previous visit here the nasty suspicions to which every investigative agent is heir had persuaded me that the relationship between George and his attractive young ‘housekeeper’ had gone a steamy step or two beyond pressing his pants before he took them off. Now I was no longer so sure. This girl was either too artless, or a wonderful actress. And surely any close relationship between them would have been built upon George being a sorrowing widower?

While I was letting the girl have a moment to rethink the situation, Dicky stepped in, believing perhaps that I was at a loss for words. ‘I’d better tell you,’ he said, in a voice airline captains assume when confiding to their passengers that the last remaining engine has fallen off, ‘that this is an official inquiry. Withholding information could result in serious consequences for you.’

‘What has happened?’ said the girl. ‘Mr Kosinski? Has he been injured?’

‘Where did you take him downtown on Saturday?’ said Dicky harshly.

‘Only to the bank – for money; to the jeweller – they cleaned and repaired his wrist-watch; to church – to say a prayer. And then to the airport to meet his friends,’ she ended defiantly.

‘It’s all right, Ursi,’ I said pleasantly, as if we were playing bad cop, good cop. ‘Mr Kosinski was supposed to meet us here,’ I improvised. ‘So of course we are a little surprised to hear he’s gone away.’

‘I want to know everyone who’s visited him here during the last four weeks,’ said Dicky. ‘A complete list. Understand?’

The girl looked at me and said: ‘No one visits him. Only you. He is so lonely. I told my mother and we pray for him.’ She confessed this softly, as if such prayers would humiliate George if he ever learned of them.

‘We haven’t got time for all this claptrap,’ Dicky told her. ‘I’m getting cold out here. I’ll take a quick look round inside the house, and I want you to tell me the exact time you left him at the airport.’

‘Twelve noon,’ she said promptly. ‘I remember it. I looked at the clock there to know the time. I arranged to visit my neighbour for her to fix my hair in the afternoon. Three o’clock. I didn’t want to be late.’

While Dicky was writing about this in his notebook, she started to pick up the big plastic basket, still half-filled with damp laundry that she had not put on the line. I took it from her: ‘Maybe you could leave the laundry for a moment and make us some coffee, Ursi,’ I said. ‘Have you got that big espresso machine working?’

‘Yes, Mr Samson.’ She gave a big smile.

‘I’ll look round the house and find a recent photo of him. And I’ll take the car,’ Dicky told me. ‘I haven’t got time to sit round guzzling coffee. I’m going to grill all those airport security people. Someone must have seen him go through the security checks. I need the car; you get a taxi. I’ll see you back at the hotel for dinner. Or I’ll leave a message.’

‘Whatever you say, master.’

Dicky smiled dutifully and marched off across the lawn and disappeared inside the house through the back door Ursi had used.

I was glad to get rid of Dicky, if only for the afternoon. Being away from home seemed to generate in him a restless disquiet, and his displays of nervous energy sometimes brought me close to screaming. Also his departure gave me a chance to talk to the girl in Schweitzerdeutsch. I spoke it only marginally better than she spoke English, but she was more responsive in her own language.

‘There’s a beauty shop in town that Mrs Kosinski used to say did the best facials in the whole world,’ I told her. ‘You help me look round the house and we’ll still have time for me to take you there, fix an appointment for you, and pay for it. I’ll charge it to Mr Cruyer.’

She looked at me, smiled artfully, and said: ‘Thank you, Mr Samson.’

After looking out of the window to be quite certain Dicky had departed, I went through the house methodically. She showed me into the master bedroom. There was a photograph of Tessa in a silver frame at his bedside and another photo of her on the chest of drawers. I went into an adjacent room which seemed to have started as a dressing-room but which now had become an office and den. It revealed a secret side of George. Here, in a glass case, there was an exquisite model of a Spanish galleon in full sail. A brightly coloured lithograph of the Virgin Mary stared down from the wall.

‘What are those hooks on the wall for?’ I asked Ursi while I continued my search: riffling through the closets to discover packets of socks, shirts and underclothes still in their original wrappings, and a drawer in which a dozen valuable watches and some gold pens and pencils were carelessly scattered among the silk handkerchiefs.

‘He has taken the rosary with him,’ she said, looking at the hooks on the wall. ‘It was his mother’s. He always took it to church.’

‘Yes,’ I said. I noticed that he’d left Nice Guys Finish Dead beside his bed with a marker in the last chapter. It looked like he planned to return. On the large dressing-room table there were half a dozen leather-bound photograph albums. I flipped through them to see various pictures of George and Tessa. I’d not before realized that George was an obsessional, if often inexpert, photographer who’d kept a record of their travels and all sorts of events, such as Tessa blowing out the candles on her birthday cake, and countless flashlight pictures of their party guests. Many of the photos had been captioned in George’s neat handwriting, and there were empty spaces on some pages showing where photos had been removed.

I opened the door of a big closet beside his cedar-lined wardrobe, and half a dozen expensive items of luggage tumbled out. ‘These cases. Do they all belong to Mr Kosinski?’

‘No. His cases are not there,’ she said, determined to practise her English. ‘But he took no baggage with him to the airport. I know this for sure. I always pack for him when he goes tripping.’

‘These are not his?’ I looked at the collection of expensive baggage. Many of the bags were matching ones embroidered with flower patterns, but there was nothing there to fit with George’s taste.

‘No. I think those all belong to Mrs Kosinski. Mr Kosinski always uses big metal cases and a brown leather shoulder-bag.’

‘Have you ever met Mrs Kosinski?’ I held up a photo of Tessa just in case George had brought some woman here and pretended she was his wife.

‘I have only worked here eight weeks. No, I have not met her.’ She watched me as I looked at the large framed photo hanging over George’s dressing-table. It was a formal group taken at his wedding. ‘Is that you?’ She pointed a finger. It was no use denying that the tall man with glasses looming over the bridegroom’s shoulder, and looking absurd in his rented morning suit and top-hat, was me. ‘And that is your wife?’

‘Yes,’ I said.

‘She is beautiful,’ said Ursi in an awed voice.

‘Yes,’ I said. Fiona was at her most lovely that day when her sister was married in the little country church and the sun shone and even my father-in-law was on his best behaviour. It seemed a long time ago. In the frame with the colour photo, a horseshoe decoration from the wedding cake had been preserved, and so had a carefully arranged handful of confetti.

George was a Roman Catholic. No matter that Tessa was the most unfaithful of wives, he would never divorce or marry again. He had told me that more than once. ‘For better or worse,’ he’d repeated a dozen times since, and I was never quite sure whether it was to confirm his own vows or remind me of mine. But George was a man of contradictions: of impoverished parents but from a noble family, honest by nature but Jesuitical in method. He drove around a lake in a motor boat while dreaming of Spanish galleons, he prayed to God but supplicated to Mammon; carried his rosary to church, while adorning his house with lucky horseshoes. George was a man ready to risk everything on the movements of the market, but hanging inside his wardrobe there were as many belts as there were braces.

Downstairs again, sitting with Ursi on the imitation zebra-skin sofas in George’s drawing-room, with bands of sunlight across the floor, I was reminded of my previous visit. This large room had modern furniture and rugs that suited the architecture. Its huge glass window today gave a view of the grey water of the lake and of George’s boat swaying with the wake of a passing ferry.

The room reminded me that, despite my protestations to Dicky, George had been in a highly excited state when I was last in this room with him. He’d threatened all kinds of revenge upon the unknown people who might have killed his wife, and even admitted to engaging someone to go into communist East Germany to ferret out the truth about that night when Tessa was shot.

‘We’ll take a taxi,’ I promised Ursi. ‘And we’ll visit every place you went on the afternoon you took him to the airport. Perhaps when we’re driving you’ll remember something else, something that might help us find him.’

‘He’s in danger, isn’t he?’

‘It’s too early to say. Tell me about the bank. Did he get foreign currency? German marks? French francs?’

‘No. I heard him phoning the bank. He asked them to prepare one thousand dollars in twenty-dollar bills – American money.’

‘Traveller’s cheques?’

‘Cash.’

‘Mr Kosinski is my brother-in-law; you know that?’

‘He hasn’t gone back to his wife then?’ she said. She obviously thought that George’s wife was my sister. Perhaps it was better to leave it that way. It was a natural mistake; no one could have mistaken me for George Kosinski’s kin. I was tall, overweight and untidy. George was a small, neat, grey-haired man who had grown used to enjoying the best of everything, except perhaps of wives, for Tessa had found her marriage vows intolerable.

‘He’s in mourning for his wife,’ I said.

She crossed herself. ‘I did not know.’

‘She was killed in Germany. When I was last here he talked about finding his wife’s killer. That could be very dangerous for him.’

She looked at me and nodded like a child being warned about speaking to strangers.

‘What did you think this morning, Ursi?’ I asked her. ‘What did you think when you arrived and found he had gone?’

‘I was worried.’

‘You weren’t so worried that you called the police,’ I pointed out. ‘You went on working; doing the laundry as if nothing was amiss.’

‘Yes,’ she said, and looked over her shoulder as if she thought Dicky might be about to climb through the window and pounce on her. Then she smiled, and in an entirely new and relaxed voice said: ‘I think perhaps he has gone skiing.’

‘Skiing? In October?’

‘On the glacier.’ She was anxious to persuade me. ‘Last week he spent a lot of money on winter sport clothes. He bought silk underwear, silk socks, some cashmere roll-necks and a dark brown fur-lined ski jacket.’

I said: ‘I need to use the phone for long distance.’ She nodded. I called London and told them to dig out George’s passport application and leave a full account of its entries on the hotel fax.

‘Let’s get a cab and go to town, Ursi,’ I said.

We went to the jeweller’s first. Not even Forest Lawn can equal the atmosphere of silent foreboding that you find in those grand jewellery shops on Zurich’s Bahnhofstrasse. The glass show-cases were ablaze with diamonds and pearls. Necklaces and brooches; chokers and tiaras; gold wrist-watches and rings glittered under carefully placed spotlights. The manager wore a dark suit and stiff collar, gold cuff-links and a diamond stud in his sober striped tie. His face was politely blank as I walked with Ursi to the counter upon which three black velvet pads were arranged at precisely equal intervals.

‘Yes, sir?’ said the manager in English. He had categorized us already; middle-aged foreigner accompanied by young girl. What could they be here for, except to exchange those vows of carnal sin at which only a jeweller can officiate?

‘Mr George Kosinski is a customer of yours?’

‘I cannot say, sir.’

‘This is Miss Maurer. She works for Mr Kosinski. I am Mr Kosinski’s brother-in-law.’

‘Indeed.’

‘He came to your shop the day before yesterday. He disappeared immediately afterwards. I mean he didn’t come home. We don’t want to go to the police – not yet, at any rate – but we are concerned about him.’

‘Of course, sir,’ he said sympathetically and adjusted the velvet pad on the counter, pulling it a fraction of an inch towards him as if lining it up more precisely with the other velvet pads.

‘We thought he might have said something to you that would help us find him. He has a medical record of memory loss, and he has been under a severe domestic strain.’

The man took a deep breath, as if coming to an important decision. ‘I know Mr Kosinski. And your sister, too. Mrs Kosinski is an old and valued customer.’

Here was another one who didn’t know that Tessa was dead. So that was how George preferred it. Perhaps he felt he could keep out of trouble more easily if everyone thought there was a Mrs Kosinski who might descend upon them any minute. I let the jeweller think Tessa was my sister; it was better that way. ‘Did he purchase something here?’

‘No, sir.’ For one terrible moment I thought he’d changed his mind about helping me. He looked as if he was having second thoughts about revealing details of his customers. But then he continued: ‘No, he brought something to me, an item of jewellery for cleaning. He said nothing that would help you find him. He seemed very relaxed and in good health.’

‘That’s encouraging,’ I said. ‘Was it a wrist-watch?’

‘For cleaning? No, we don’t service watches; they have to go back to the factory. No, it was a ring he brought for cleaning.’

‘May we see it?’

‘I’ll enquire if it is on the premises. Some items have to go to specialists.’

He went through a door in the back of the shop and came back after a few minutes using a smooth white cloth to hold an elaborate diamond ring. ‘It’s a lovely piece; not at all the modern fashion, but I like it. A heart-shaped diamond mounted in platinum with four smaller baguette diamonds. Quite old. You can see how worn it is.’ He held it up, gripping it by means of the towel. The ring was dripping wet with some sort of cleaning fluid which had an acrid smell. ‘It was encrusted with mud and dirt when he brought it in. In twenty years I have never seen a piece of jewellery treated in such fashion. A ring like this has to be cleaned very carefully.’

‘He didn’t say he was going abroad? His next call was the airport.’

He shook his head sadly. ‘I’m afraid he gave no indication… it seemed as if he was on a shopping trip, doing everyday chores.’

We exchanged business cards. I gave him one of Dicky’s, an anonymous one with one of our London-based outside phone lines on it. I scribbled my name on the back of it. ‘If you remember anything else at all I’d be obliged.’

He took the card and read it carefully before putting it into his waistcoat pocket. ‘I will, sir.’

‘While you’ve been wasting your time, talking to the maid and looking at wrist-watches, I have been thinking,’ said Dicky after I told him what I had been doing that afternoon, omitting the bit about paying for Ursi’s alarmingly expensive facial and manicure.

‘That’s good, Dicky,’ I said.

‘I suppose that analytical thinking has always been my strong point,’ Dicky mused. ‘Sometimes I think I’m wasting my time at London Central.’

‘Perhaps you are,’ I said.

‘Reports and statistics. Those Tuesday morning conferences… trying to brief the old man.’ As if remembering the last time he briefed the old man, he looked at red marks on his fingers which had not completely healed over. ‘He’s here,’ said Dicky like a conjuror.

‘The old man?’

‘The old man!’ said Dicky scornfully. ‘Will you wake up, Bernard. George Kosinski. George Kosinski is here.’

‘In the hotel? You’ve seen him?’

‘No, I haven’t seen him,’ said Dicky irritably. ‘But it’s obvious when you sit and concentrate on the facts as I have been doing. Think it over, Bernard. Kosinski left home without even packing a bag. No one came to visit him; he just up and left the house. No cash, no clothes. How would he manage?’

‘What’s your theory then?’ I asked with genuine interest.

‘It’s obvious.’ He chuckled. ‘Obvious. That bastard Kosinski is right here in Zurich, laughing at us. He’s checked into one of these big luxury hotels, and he’s biding his time until we depart again.’ I said nothing; I knew what was coming; I could read Dicky’s mind when his eyes glittered that way. ‘Our visit here was leaked, Bernard old son.’

‘Not by me, Dicky.’ The reality behind Dicky’s new theory was that his experimental dalliance with investigative enquiries at the airport had been met by airport security men as boorish, obstinate and status-conscious as Dicky could be. Having failed at the airport he’d come back to the hotel to evolve a more convenient theory.

‘By someone. We won’t argue,’ he said generously. ‘Who knows? It could have been some careless remark by one of the secretaries. The Berne office knew we were coming here. They have local staff.’

I nodded. Of course, local staff. No one British must be suspected of such a thing.

‘Tomorrow you can start checking the hotels. Big and small; near and far; cheap and flashy. You can take this photo of him – I pinched it from the drawing-room – and go round and show it to them. We’ll soon find him if we’re systematic.’

‘And which hotels will you be doing?’

‘I will have to go to Berne. It’s tiresome but I must keep the ambassador in the picture or the embassy people will feel neglected.’

‘Dicky, I’m not a field agent any longer.’

‘London staff.’

‘No, I’m not London staff either. I’m on a five-year contract that can be terminated any time that someone on the top floor sends me for a medical check-up having told their tame quack to give me a thumbs-down.’

‘That’s a bloody disloyal thing to say,’ said Dicky, always ready to speak on behalf of the top-floor staff. ‘No one gets treated like that. No one! We are a family. It doesn’t serve your cause to become paranoid.’

I’d heard all that before. ‘If I’m to go schlepping around these hotels for you, I must go back on to my proper field agent per diem, with expenses and allowances.’

‘Don’t moan, Bernard. You are an awfully nice chap until you start moaning.’

‘What I’m saying…’

He waved his injured hand airily above his head. ‘I’ll see to it, I’ll see to it. If you’d rather be a field agent than wait for a proper senior staff position in London.’ I never knew how to deal with Dicky’s bland reassurances. I felt unable to pursue my argument, despite knowing that he had no intention of doing anything about it.

‘You want me to go chasing rainbows,’ I said. ‘This is Switzerland, it will cost a fortune. I must have an advance. Otherwise I’ll be spending my own money and waiting six months while London processes the expenses.’

‘Chasing rainbows?’

‘Look, Dicky. George Kosinski isn’t skulking around in some local hotel here; he’s gone.’

‘The girl told you?’

‘She thinks he’s gone skiing on the glacier.’

‘Why?’ Dicky chewed on his fingernail, anxious that he’d missed an opportunity. ‘Did Kosinski tell her that?’

‘He bought silk underwear and a ski jacket last week.’

‘That settles it then.’

‘George hates skiing,’ I explained. ‘He’s hopeless on skis and hates ski resorts.’

‘What then?’ said Dicky.

‘For one thing his bags have gone. It looks like he went to the airport in secret, and left them there ahead of time. He obviously wanted to get away without attracting attention; but who was he trying to avoid? And why?’

‘And where?’ added Dicky. ‘Where has he gone?’

‘Somewhere that gets damned cold; hence the silk underwear. My guess is Poland. He has a lot of relatives there: brothers, uncles, aunts and maybe a still-living grandfather. If he was in trouble, that’s where he might well go.’

‘We can’t depend on a few odds and ends of guesswork, Bernard.’

‘George has been raiding his old photo albums for snapshots to take along. He also took the rosary his mother gave him. It’s a trip to his family. Perhaps that’s all it is. Maybe someone is sick.’

‘That’s not all it is. Someone came here and talked to him. We know the Stasi people came through here.’

‘The girl said no one came to visit,’ I countered. I didn’t want Dicky to condemn George and then start collecting evidence.

Even Dicky could answer that one: ‘So Kosinski went out and met them somewhere else.’

‘It’s possible,’ I said. ‘But that doesn’t prove that there is anything sinister about his disappearance.’

‘I don’t like it,’ said Dicky. ‘It smells like trouble… with all that Tessa business, we can’t afford to just shrug it off. We must know for certain where he’s gone.’

‘He’s gone home to Poland,’ I said again. ‘It’s only a guess, but I know him well enough to make that kind of guess.’

‘No zlotys from the bank?’

It was a joke but I answered anyway. ‘They are not legally sold; he’d be better off with US dollar bills.’

A long silence. ‘You’re not just a pretty face, Bernard,’ he said, as if it was a joke I’d never heard before.

‘I may be wrong.’

‘Where in Poland?’

‘I got the office to sort out his passport application. His parents were from a village in Masuria, in the north-east. His brother Stefan lives in that same neighbourhood.’

‘What are you holding back, old bean?’ Dicky asked.

‘The Poles in London are a small community. I made a couple of calls from my room… a chap who runs a little chess club knows George well. He says George goes back sometimes and sends his family money on a regular basis.’

‘And?’ he persisted.

‘I can’t think of anything else,’ I said.

‘You’re holding back something.’

‘No, Dicky. Not this time.’

‘Very well then. But if this is simply your devious way of avoiding schlepping round these bloody hotels I’ll kill you, Bernard.’ He looked at me, his brow furrowed with suspicion at the thought I was withholding something. Then with that remarkable intuition that had so often come to his aid, he had it. ‘The wrist-watch,’ said Dicky. ‘Why did he take the wrist-watch for cleaning? And why would you bother to follow it up by going to the jeweller?’

‘A man like George has dozens of flashy watches. He doesn’t take them for cleaning, not when he has other things on his mind.’

‘So why follow it up? Why go to the jeweller then?’

I rubbed my face. I would have to tell him. I said: ‘It was his wife’s engagement ring.’

‘Tessa Kosinski’s engagement ring? Jesus Christ! She’s dead. In the East. You bastard, Bernard. Why didn’t you tell me right away?’

‘It was dirty, muddy, the jeweller said.’

He shook his head, and heaved a sigh that combined anger and content. ‘Never mind whether it was dirty or not. My God, Bernard, you do spring them. You mean some Stasi bastards came here with his wife’s engagement ring? They’re talking to him? Pushing him? Leading him on? Is it something about the burial?’

‘My guess is they are saying she’s still alive.’

‘Alive? Why? What would they want in exchange?’

‘I wish I knew, Dicky.’ Dicky’s phone rang. I looked at my watch, got to my feet and waved goodnight. ‘Shall I see you at breakfast downstairs?’

Dicky, bending low over the phone, twisted his head to scowl at me and held up a warning finger. I waited. ‘Hold it, Bernard,’ he said. ‘It’s London on the line. This is something you might want to stay awake thinking about.’