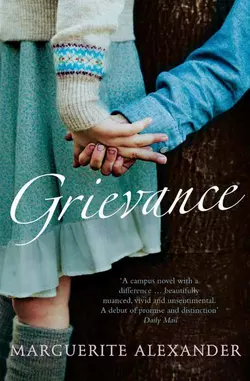

Grievance

Marguerite Alexander

A moving novel about the relationships within families and between friends, told through the touching story of a young woman starting out on a new life in London, on a quest to escape the claustrophobia of her small hometown.Nora Doyle, a young Irish girl, has come to university in London. The promise of a loving and idyllic childhood was brutally cut short when she was forced to assume the responsibility of looking after her Downs syndrome brother while her parents, devastated by his birth, retreated into their collapsed lives. Only Nora gave her brother the love, care and attention he needed, but she had to endure the watchful eye of her bullying, dogmatic father and the resentment of her crushed, self-pitying mother.To escape the small-town claustrophobia of a Northern Ireland battered by political and religious divisions, Nora begins a new life in London. But instead of finding friends and caring adults to make up for her own lack of parental love and normal family life, she unwittingly becomes the obsession of her narcissistic lecturer and finds it hard to connect with her peers. Too late she realises that she can escape from her family, but her behaviour and relationships with those around her continue to be shaped by her upbringing.Written with sensitivity and a rare emotional insight, this is a richly woven story about how we make connections and what it is that severs them.

Grievance

Marguerite Alexander

For Rachel, Chloë, Hannah and Tom

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#u957d6389-039a-511a-aebf-58f0a3b2253f)

Title Page (#ubbbf133e-78c2-5286-b214-565402d98a48)

PART ONE Animals (#u87a66b33-4d3a-5e8d-8094-bec5d1b34266)

London (#uee75d80e-a54f-55da-a646-7426e56b5048)

Ballypierce (#u2b006085-5853-5f7b-9cd3-5944f5f44bee)

PART TWO Servants (#uab4b9f90-1dbb-580d-98c6-f7cbbab2b9a4)

London (#u61a4aa5b-d081-5bc6-aa10-cd0db4fdc60a)

Ballypierce (#litres_trial_promo)

PART THREE Rituals and Meaning (#litres_trial_promo)

London (#litres_trial_promo)

Ballypierce (#litres_trial_promo)

PART FOUR Ecstasy and Longing (#litres_trial_promo)

London (#litres_trial_promo)

Ballypierce (#litres_trial_promo)

PART FIVE The Slaying of the Father (#litres_trial_promo)

London (#litres_trial_promo)

Ballypierce (#litres_trial_promo)

PART SIX Understanding Women (#litres_trial_promo)

London (#litres_trial_promo)

Ballypierce (#litres_trial_promo)

PART SEVEN Exile (#litres_trial_promo)

London (#litres_trial_promo)

Ballypierce (#litres_trial_promo)

EPILOGUE (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PART ONE Animals (#ulink_b5a30344-8e14-5345-b09d-39b0b4262af6)

London (#ulink_cbc72def-3e1e-51dc-b210-4fc9266fef4f)

It is, Steve supposes, the particular quality of the September afternoon that makes the group so picturesque. The air is so still that the few leaves that are ready to fall drift to the ground with a kind of languor, their colours, in their slow descent, caught in the slanting rays of the sun. It was to enjoy the effect that Steve had lingered; otherwise he might not have noticed the young people at all. There are about half a dozen, mostly seated, one or two of the young men lying, under the handsome chestnut tree in the college quadrangle.

A picnic seems to be in progress. A woollen rug is spread on the grass, dotted with plates of food and large jugs of Pimm’s, its colour harmonising with the autumnal tones of the setting. It must be somebody’s birthday, or perhaps a celebration of reunion at the beginning of the new academic year. Their clothes are unusually bright for undergraduates and one of the girls, who is wearing a floral printed summer dress, has some kind of wreath on her long, crinkly red hair. As Steve watches, she picks up the jug and fills the glasses that stretched arms hold out to her. None of the group is familiar to him, but he’s just returned after a year’s sabbatical and is unlikely to recognise students he doesn’t teach.

He is just about to move on when one of the reclining young men suddenly sits bolt upright and, as he speaks, waves his long, gangly arms in the air. Steve is too far away to catch what he has said, but the gales of laughter that greet the young man’s performance drift across the quad towards him. He smiles to himself, shut off from the joke but pleased by the scene.

He is just about to move on to his office when another group of young people, equally striking but quite different from the first, claims his attention. With an immediate feeling of revulsion, quickly followed by shame, Steve realizes that a number of this second group have a severe mental handicap. They roll their heads and mutter to themselves, apparently indifferent to their surroundings. It seems that, left to themselves, they would shuffle aimlessly along, but the expedition is given an air of purpose by the others, young helpers who are all linked by the arm to their special charges, whom they are guiding across the quad. There is a young woman with Down’s syndrome, whose shoulder-length silky light-brown hair briefly reminds him of his daughter, Emily, but this one point of resemblance heightens the cruelty of the contrast between them. He takes in her face, its tiny features puckered with anxiety; her hands, clutching the arm of the athletic young woman who is leading her; the large thighs and buttocks in the shapeless tracksuit bottoms. Then he turns away, finding his own curiosity inappropriate.

He can’t think what they might be doing here. He wonders whether, in his absence, his colleagues have initiated some outreach programme, possibly attracting government money. It’s the kind of well-meaning, but ultimately pointless, scheme that a junior minister might consider worthy of funding. Unless it’s an initiative by one of the student Christian groups. His interest withers, as it always does, at the thought of active religious commitment (but only in this context: religion as an expression of nationalism or oppression or political discontent is another matter entirely).

Because he doesn’t want to cut across the slow, straggling line, he switches direction and makes a loop that brings him closer to the party of picnickers and, for the first time, notices a girl who, from his earlier position, had been partly obscured. She is more simply and austerely dressed than the others, in white T-shirt and black jeans, small, slender, finely moulded and delicately featured, with the kind of colouring – black hair, blue eyes and pale, almost white skin – that immediately makes his heart leap.

He is particularly struck by her attitude. She is kneeling, body upright from the knees, looking intently away from her friends. Steve slows down and sees that she is following the progress of the last pair in the group crossing the quad.

At first he thinks that her interest is in the young guide, so unlikely does it seem that an educated girl of her generation would stare so blatantly at someone with an obvious mental handicap. The young man is tall, fair-haired, tanned and would, Steve imagines, gaze deep into the eyes of anyone prepared to listen and tell them how much God loves them. He feels a vague resentment that such a remarkable girl should squander her attention on such an unworthy object.

Almost immediately, however, he decides he’s mistaken. To his practised eye, her manner does not suggest sexual interest. He looks as closely as he can at the muscular Christian’s partner, who is on the far side and can only be seen in profile. He, too, is tall and fair-haired, but his features, like those of the girl who reminded him of Emily, are marked by Down’s syndrome. Their arms are linked, but the arrangement seems purely mechanical, the one showing no awareness of the other’s presence.

Steve’s attitude to the guide changes to respect, particularly for his attempts to interest his charge in their surroundings. His free arm is busy indicating points of interest in the quad and he keeps up a steady flow of conversation, but the other boy’s head remains averted, whether or not as a deliberate snub, it’s impossible to say. Then as the pair, who have been drifting away from the rest of the group, turn to catch up, Steve sees that the boy with Down’s syndrome is holding a long chiffon scarf in a brilliant pink. Never taking his eyes off the scarf, and with remarkably deft and practised movements, he waves it in an elaborate series of loops to produce an effect of some beauty.

Steve supposes it was the scarf that caught the girl’s eye, and then she became mesmerised by the performance. Still a puzzle remains, that she should find the boy so compelling that she forgets her friends and the party taking place around her. He is struck by the irony: he has been transfixed by the girl, who shows no awareness of his presence, while the boy, who has eyes only for his scarf, absorbs her.

Then suddenly this long, suspended moment, to which the still September air and slanting rays of golden sunshine have contributed, is broken. The young man and the boy with the scarf are gone, along with the rest of their group. And the young woman has dropped back on her heels and turned to her friends, who now seem to Steve noisy, even raucous, after the intense quiet of the boy and the girl who was watching him. He turns away in the direction of his office.

As the afternoon slides into memory, Steve comes to see it as marking the end of his sabbatical, gaining importance with the new turn of events. But memory can be treacherous. What stays in the mind is the girl, for whom everything else becomes merely setting – not just the chestnut tree and the early-autumn sunshine, but her friends too. In the manner of sheep and goats, they serve to emphasise her difference: her apartness, her seriousness and her intensity.

Her beauty is striking enough against her own immediate background, but when the other young people, so cruelly served by nature, are brought into play, it acquires iconic value. What he forgets, as the days pass, is her mysterious absorption in the boy with the pink chiffon scarf. It may be that it’s beyond his scope to see someone so signally lacking in beauty and intelligence as capable of meaning.

In responding as he does, reordering and refiguring the world according to unexamined prejudices, he makes a fatal error, one that he is always careful to warn his students against. He ignores the context in which he first saw the girl, all those other elements in the scene that are crucial to understanding. And context, as he has spent so much of his professional life arguing, is different from background, which gives the central object transcendent status, encouraging the interpreter to impose his own meaning.

Meanwhile Steve picks up the threads of his professional life and falls back into patterns and routines. There is his new undergraduate course on Irish literature to think about. He has his first sessions with two new doctorate students, both too awed by his reputation to do more than mouth the platitudes into which his own once groundbreaking work has fossilised. There are emails and letters to answer and papers to read, but while he dispatches everything with his usual efficiency, he feels himself to be only half there, semi-detached from his professional self. This isn’t just because he’s been away from it all. The truth is that, although nobody but his wife Martha yet knows of his plans, he is already planning at least a partial escape, in search of another outlet for his talents, and hopes to make an even bigger impact than, as a young scholar, he made on the academic world.

He’s pulled back sharply into the here and now when Charles Rowe pays his welcome-back call. Just for that moment Steve wishes, as must his colleague, that they were still in the time of Rowe’s beloved Jane Austen when a card left on a platter might do the trick.

Steve knows that it’s Rowe even before he’s in the room. There is a shuffling sound outside the door, the unmistakable signal of Rowe’s approach, then a light, tentative knock, followed by a much louder one, in case the first wasn’t heard, both indications of his unease at the prospect of seeing Steve.

‘Yes, come in.’ Steve turns from his desk as Rowe’s overlarge head twists round the door. He wonders whether, as a boy, his colleague was encouraged to see it as stuffed with brains to compensate for the embarrassment it must have caused.

‘Ah, Steven. Good. You’re here. Excellent.’ The words are carefully articulated, suggesting a stutter, once painfully overcome, which always seems on the verge of returning in Steve’s presence: although they’ve rubbed along well enough together for some time now, it’s clear that Rowe has never recovered from the shock he received when Steve was first appointed to the English department and set about overturning the cherished assumptions of his older colleagues.

This was in the early eighties, the beginning of the Thatcher era, when young men (and a few young women) like Steve brazenly presented themselves as a countercultural revolutionary force. Ignoring much of the traditional canon, Steve required his students to read French critics and philosophers like Foucault and Barthes. Rowe, ever eager to learn, dipped into them himself, and finding the prose impenetrable – an unhappy afternoon spent struggling with one paragraph of Derrida has left painful scars on his memory – dismissed them as rubbish, then found to his dismay that the students lapped them up. When they started quoting what he came to think of as the ‘Gallic wreckers’ in essays he had set, he was at a loss how to grade them.

For Rowe and others of his generation, there was a seismic shift. Literature as a repository of eternal values was dismissed in favour of the idea that it was all culturally determined. Even worse was the thought that some of the most valued works in English were hoodwinking their readers into accepting bourgeois values. Jane Austen came under scrutiny and Rowe had to swallow the bitter pill that Mansfield Park, his own favourite, was not after all about personal morality and religious vocation but slavery. It seemed that the only ‘correct’ way to read a text was to concentrate on those who were ‘marginalised’ (another new concept) by it: colonial subjects, women, homosexuals. And slaves. The forces of righteousness had arrived.

Traditionalists like Rowe, who in the beginning found comfort in dismissing the new critical theories as absurd – ‘the emperor’s new clothes’ was the phrase he used with like-minded colleagues – were soon silenced by Steve. His face had a way of setting in contempt at opinions different from his own, and this induced an acute sense of humiliation in those who had been foolhardy enough to voice them. For one so young, Steve was remarkably confident – a confidence that was rapidly justified by events. His first book sold in numbers previously undreamed-of in academic circles and made him something of a celebrity. Overnight it seemed that the ideas he and others of his generation pioneered had become the new orthodoxy, leaving Rowe and his bewildered colleagues with no choice but to conform.

Once the battle was won, harmony of a sort was restored; since Steve’s early appointment to a professorship, which made him, in hierarchical terms, Rowe’s equal, he has behaved with impeccable courtesy towards him, as he does now, getting to his feet in deference to the older man and ushering him to a chair.

‘Well, just for a few minutes, perhaps,’ Rowe says. ‘Far be it from me to disturb you when you’re h-hard at it.’

Steve tries not to look while Rowe, clutching a stack of papers as justification for his visit, makes his ungainly way to the chair, then sinks into it. His condition seems to have deteriorated rapidly over the past year, since Steve last saw him, if indeed there is a condition, other than the process of ageing. He can’t be more than sixty-three or -four, Steve thinks. Only fifteen years older than I am. Christ.

‘You’re looking very well,’ Rowe says. ‘Restored, if I might say so.’

Steve, who is leaning back against his bookshelves, arms folded and ankles crossed, raises an eyebrow in reply. He’s not sure that he likes the idea of being in need of restoration, of being on the downward side of a curve where his inevitable decline may, from time to time, be halted, but never reversed; where a renewal of youthful vigour, after much-needed restoration, will inevitably be short-lived.

‘Not that you ever…’ says Rowe, hastily. ‘Oh dear, you work so admirably hard that I imagined the break…’ This sentence, too, fails and Rowe lowers his eyes in shame.

‘It was, as you say, restorative,’ says Steve, suddenly relenting. It seems churlish to take out his disaffection on Rowe.

His colleague rewards this small act of kindness with a relieved smile that briefly shows discoloured teeth. ‘Not too much time in the library, I hope?’

‘Some, but I also did the Joyce trail – Dublin, Paris, Trieste, Zürich.’ Steve has always avoided studies of individual writers before, preferring theoretical exposition, accompanied by theatrical sleight-of-hand, to overturn the received meaning of canonical texts. Before his sabbatical, however, he announced his intention to write a book on James Joyce.

‘Ah, I envy you.’ Rowe is beginning to relax, to lose the persecuted expression that he wore on entering the room. ‘Jane Austen doesn’t provide her acolytes with quite the same opportunities for travel.’

‘No, I suppose not. So, what can I do for you, Charles?’ Steve nods in the direction of Rowe’s bundle of papers.

‘Ah, yes,’ says Rowe, leafing through them. ‘Here’s something to get you back into the swing of things. I thought I’d bring you up to date with preparations for the Gender and Ethnicity Conference.’

His manner is shyly confident, that of a man offering a particularly rare treat. His confidence is all the more poignant, or piquant, in view of the battering he has received over the years from the keepers of the new orthodoxies. If anybody is responsible for his present sorry state – his pathetic anxiety to please, his physical deterioration, the stutter that seems always on the verge of returning – then it’s probably Steve himself, in creating a climate in which Rowe has been obliged to conform to ideas that he may not even understand, let alone endorse.

‘That’s very thoughtful of you, Charles,’ Steve says. ‘Leave it with me and I’ll give you my comments as soon as I’ve had the chance to read all the material.’

Rowe fails to respond to Steve’s dismissal. ‘We’ve taken the liberty – or, rather, I’ve taken the liberty – I must take full responsibility here…’ he pauses to send Steve a complicit smile, a sure sign, for all his disclaimers, that he has little doubt of pleasing ‘…to put your name forward for the main session of the conference. Something on Irish ethnicity, perhaps, since that seems to be the direction your interests are taking? I thought some advance publicity for the book – not, of course, that you ever need…’

No, I don’t, thinks Steve, angry even while knowing that Rowe means no harm. His reputation alone is enough to guarantee all the publicity he needs. Besides, the department ought to be able to see that he’s moved beyond giving a paper at any conference Rowe is capable of organising. Of course, his name is associated with these ideas – his book on critical theory, although published twenty years ago, is still included on reading lists, not just for literature but for history and anthropology students – but now it’s for the foot soldiers to carry on a battle that’s been largely won. It’s true that he’s about to teach a course on Irish literature, but if he has to teach, he might as well amuse himself.

He’s sufficiently in control of his own reactions, and aware of the danger of burning his boats, to say, ‘Thank you, Charles. It’s nice to know I wasn’t forgotten in my absence. But may I think about it? I’d really rather not commit myself to anything until I see how much time I can squeeze out of all this.’ He makes a sweeping movement with his arm that vaguely encompasses the full range of professional duties suggested by the crowded desk. ‘More than anything, I’m anxious to get on with the book.’

Rowe is disappointed, but not crushed. He has suffered so many defeats in the course of his working life, even when, as on this occasion, he is sure that his actions will be welcomed. ‘Of course, Steven. Whatever you think best. If you could let me know in time to find an alternative speaker – if that’s what you decide, of course…’

He struggles to his feet, makes his ungainly way across the room, then pauses at the door and lifts his arm in farewell before leaving.

Steve sinks into his chair and sits for a while with his head in his hands, wondering how he’s going to be able to put in his time until his means of escape materialises. He had embarked on his sabbatical, and his book on Joyce, with the idea of changing direction but without realising how far in a new direction he would be taken. He’d known for a while that the critical revolution he had helped bring about had peaked; that there was no longer any shock value in overturning expectations when, for new generations of students, deconstruction was already commonplace. He had become a victim of his own success. But the nature of that success was, he had come to feel, rather limited.

In the decade and a half since he made his name, public interest in the academy has shifted away from the post-structuralist approach to literature that once tore apart English departments (the new craze is for reading groups, where no expertise is needed to pitch in with an opinion) towards science and the grand narratives of the neo-Darwinians and astrophysicists. The change can be charted through radio talk-shows, where he is no longer a valued guest, in which the hosts, former devotees of the arts, struggle to ask scientists meaningful questions.

At the same time, those of his arts colleagues who have maintained or strengthened their public profiles – for Steve’s weakness is that he craves public recognition, only feels fully alive when he is ahead of his peers – have moved into biography and cultural history (in at least one well-known case, the history of science), where they have found a way of overturning received ideas through a gossipy, personality-driven, accessible approach. If anything short of a miracle is capable of restoring a spring to Rowe’s step, Steve thinks, it would be the knowledge that he, the once formidable champion of the obscure and arcane processes of critical theory, is now weighing the merits of accessibility.

What attracted him to Joyce was the opportunity he saw for a flashy tour de force, a critical and biographical work that mimicked Joyce’s own writing. Through a combination of deep scholarship and a light, knowing manner, he would illuminate Joyce and find his own way back to the talk-show circuit. And there was an additional beauty in his original idea: that it needn’t look like a desperate move to revive a flagging career since it could be presented as a development of his earlier interests. For was not Joyce himself, like many Irish writers, a kind of deconstructionist? And wasn’t the shift in focus to an Irish writer entirely consistent with his own known interest in colonial writing?

It certainly wasn’t a disadvantage, in his original calculations, that Ireland had become a fashionable topic, not just for former colonial oppressors but, it seemed, globally: Ireland was the only country in the European Union that all the others could agree to admire, a nation that had transformed itself economically without losing any of its lovableness. A new book on Joyce would be a reminder of a different moment in Irish history and of the persistent literary creativity of the Irish. And it would also launch Steve into a new phase in his career, as commentator on Ireland more generally, an informed outsider with the skills and knowledge to take on Ireland’s new identity.

His motives, while self-interested, were never cynical. He was genuinely engaged by the subject, while the still unresolved situation in Ulster – where his allegiances were and are, of course, with the minority Catholic population – would offer him full scope for the committed political position (on the side of the oppressed, the marginalised, the silenced) with which his name is associated. Once that wider role, to which his book on Joyce would give him access, has been secured.

Then an extraordinary thing happened. During his sabbatical he visited Ireland – Dublin, Galway, Cork, places associated with Joyce and his wife Nora – and fell in love. Not with a person, but with the place and its people. It seemed that all the clichés currently employed for contemporary Ireland, about its dynamism, its vibrancy and vitality, about a young, highly educated population that was comfortable both with ideas and popular culture, about a nation that had thrown off the shackles of the past to forge a new identity, were true. And although he never visited the North, his experience of the Republic confirmed his political sympathy for the Northern Irish Catholics, who had only to free themselves of the last vestiges of colonialism to effect the same transformation.

He felt a euphoria of a kind that was new to him. He had gone to Ireland deeply committed to the theoretical position that had underpinned his work – that there is no such thing as a fixed national character that justifies hostile stereotypes, only a set of characteristics that are a response to historical circumstance – and had the satisfaction of seeing his theories triumphantly vindicated. The drab, pious, inward-looking Ireland that he had visited once as a student and found uncongenial, despite the magnificent literature and a history that could only enlist his sympathy, had disappeared as the people had responded to new opportunities. What had been for Steve an idea had become a romance.

Having always seen himself as the least sentimental, most rational of men, this new emotional attachment to his subject has taken Steve by surprise so, of course, he rationalises it. His enthusiasm, he argues, is for the pleasure of being right, of testing a theory and finding it true. And he has enough self-awareness to see that the revelation of Ireland came to him at a moment when the need for change in his own life had become a yearning. Ireland’s transformation was an inspiration.

So why is he sitting in his office, with his head in his hands, the picture of misery? He’s begun to wake up in the night with a feeling of dread because his book on Joyce has stalled and the bright new future he has envisaged for himself seems to depend on it. He urges himself to be patient, that it’s only his eagerness to move his life into a new phase that has produced the deadlock. But this has no effect on the panic he feels whenever he tries to work. What if he never achieves anything again, comparable to that precocious leap to academic stardom? Sometimes he feels on the verge of a creative breakthrough, the realisation of which will confound the world and force the admission that, highly though he was estimated before, he was in fact underestimated. At such times, the germ of a startling idea hovers on the edge of his consciousness, but when he tries to pull it to the centre of his mind, where it can be examined and developed, it proves elusive, not only refusing to shift but disappearing altogether.

He gets up and wanders over to the window, hoping to see something that will distract him, like the scene under the chestnut tree, but there’s nothing beyond the usual comings and goings. Maybe, he tells himself, this period of sterility is the prelude to a major breakthrough. If he can only be patient, not panic and be alert to possibilities, who knows?

There are more immediate claims on his attention, however, and soon the opening session of his course on Irish literature arrives.

‘So, one of our objectives on this course is to restore to the Irish their literary heritage.’

The room is packed with second-year students who have come in expectation of a performance from Professor Steven Woolf. His reputation has preceded him and so far he’s done nothing to disappoint them. He’s seated on, rather than behind, the desk, his motorcycle helmet perched next to him, and his stance draws attention to his effortless command of the subject, for he is speaking without notes, enforcing their attention, demanding their complicity in the critical position he’s outlining. He’s dressed like them, in leather jacket and jeans, though his were almost certainly bought new rather than second-hand, which both erases and confirms the differences between them. He hasn’t lost his youthful edge, the impression he gives of belonging to a generation in the vanguard of change, but he is also a legendary figure, occupying a position to which they might aspire but will almost certainly never reach. In asserting his intention to restore to the Irish what they have lost he speaks as their champion, as one who has the authority to make a grand gesture of restitution.

Except, of course, that such an act of restitution is now redundant. He is impressive, but the group is not without sceptics.

‘I’d have thought they’d got the hang of claiming their own heritage by now,’ says Nick Bailey, one of the stars of the year, to his friend Pete Taylor, who is sprawled across his chair as usual, as if he doesn’t know where to put his unusually long arms and legs.

‘World leaders, my son,’ says Pete. ‘But you can see his problem. What do you do when the disadvantaged refuse to stay shackled and destroy all your arguments?’

Steve stops abruptly and glances in their direction. As his eye comes to rest, first, on Pete, then on Nick, he is briefly puzzled, before the professional mask is resumed. ‘This isn’t a lecture,’ he says. ‘You’re quite free to make your point to the room at large – if it’s something you’re prepared to share.’

The two young men exchange a look, and then Pete says, ‘We were saying that the Irish seem to be pretty good at exploiting their own heritage these days. That’s when they can spare the time from being a tiger economy and relaxing with sex, drugs and rock and roll. I just wondered whether our idea of the Irish wasn’t a bit out of date.’

Steve is too practised to take offence, or at any rate to show that he has, especially since Pete’s point has been made with a good-humoured lack of aggression. When he responds, his manner is smooth and impenetrable.

‘You’re quite right that the Irish are no slouches in manipulating popular history for tourism, but that isn’t quite what I had in mind. I’m merely signalling my intention to look at texts not as timeless works of imperishable genius that are part of the English literary canon but in the context of Irish history, Irish society and Irish politics, and of the power relations that, however concealed, have shaped the writers’ attitudes.’ He pauses before landing his parting shot. ‘And it’s worth remembering, before we get too carried away, that there is one part of the island of Ireland where history isn’t yet over, and where the inhabitants don’t yet feel free to surrender themselves to the rock-and-roll culture. I don’t intend putting this to the test, but I would hazard a guess that even here, in this very room, there are pockets of ignorance about the historical roots of the situation in Northern Ireland that you’ve all grown up with.’

There is no doubting Steve’s political engagement and, duly chastened, Nick, Pete and the few others who are inclined to levity, settle down. However predictable Steve’s views might be to those who have read his books, his own history commands respect. This generation of students hadn’t yet started primary school when his book on critical theory was published, at the beginning of the Thatcherite revolution. The left, disabled by defeat, had embarked on a long and acrimonious quarrel with itself, but Steve’s particular brand of Marxism – playful, subversive, disrespectful of authority – offered a new kind of Utopian vision. English lecturers were being hired and fired according to divisions Steve had helped to create. People subscribed to a belief in him as they might to a religion. His ideas, like the Falklands War, created opposing camps. And, of course, it went without saying that if you were in favour of Steve you were against British action in the Falklands.

His status, however, is not just a matter of the theories promoted in his published work. He marched with the miners and was kicked by a policeman. This is a matter of record, captured by a BBC cameraman. And when he appeared on late-night arts programmes – for this was the beginning of his career as a minor television personality – he extended the academic debate into the public issues of the day, claiming, as he is now, that there is no distinction between critical and political practice.

He is known to have turned down a chair at Oxford, where he started his career as an undergraduate, and although some of his colleagues have hinted – privately, to one or two favoured students – that Steve’s preference is to be as close as possible to the television studios, that he may even, at this moment, be turning his attention to Irish literature because, in the current political climate when ideology is felt to be a handicap, Ireland is the flavour of the month and an issue on which righteous indignation might still be expressed, many here prefer to believe that he rejected Oxford on the grounds of élitism.

He is a star turn, and they are as mesmerised by his personal style as by what he has to say: the leather jacket, the desert boots, the motorcycle helmet on the desk, while the satchel that holds his papers is thrown casually onto the floor. And it isn’t as though the style has been cultivated to compensate for deficiencies in appearance, as is all too evidently the case with one or two of the younger lecturers. His black hair, brushed back from his face, is thick and only slightly greying, his mouth is full, red and sensual, his eyes, behind the wire-framed glasses, large, dark and – well, yes, brooding, as one or two of the girls concede to each other, cliché though it is.

The mind of Phoebe Metcalfe is as likely as not to be preoccupied with such matters, so her friends are surprised when, instead of a note to that effect – enlivened, as her communications usually are, with a little drawing of a smiling face and other icons expressive of good cheer – she makes an intervention that shows she has been attending to the substance of Steve’s argument. He has just delivered his thoughts on the question of national character.

‘I must make clear, right at the outset,’ he has said, ‘that I don’t want any of the texts that we’ll be reading explained by a woolly reference to national character, as though that’s a fixed and mysterious essence that we all more or less understand. The Irish have suffered more than most from the stereotypes that other people have imposed on them. Like all national stereotypes, they tell us more about the prejudices of those who use them than about the Irish themselves.’

He sounds genuinely indignant, and one or two remember that Steve is Jewish, which might account for his fellow feeling with another racially stereotyped group. He removes his glasses to massage the bridge of his nose and in that pause of temporary sightlessness he fails to see Phoebe, who is already bobbing excitedly up and down in her chair. His sight restored, Steve returns to his argument.

‘We’ve already had a contribution to that effect, of course. We used to see the Irish as commercially backward and God-fearing, one or both due to some flaw in the national character. Now, the Republic at any rate is an economic model for the rest of Europe and one of its coolest holiday destinations. Meanwhile, revelations of child abuse have undermined the hold of the Church in less than a generation. So, characteristics that once seemed fixed are vulnerable to changing circumstances.’

Phoebe finally explodes: ‘Oh, but the Irish are special and, like, different?’

Steve has been intermittently aware of her throughout the session, although so far he has restrained himself from showing annoyance. There is a general air of noise and bustle about her that suggests, to his trained eye, someone with poor concentration. Her chair seems to scrape every time she moves, which is a good deal more often than others find necessary. She has spent most of the class so far trying, and rejecting, a series of pens that are kept in an enormous carpet bag; and each time one is replaced by another, the bag is dragged from floor to lap and back again. And in the gaps allowed by her fidgeting, she has made a series of attempts – all, so far, unsuccessful – to engage the girl next to her in whispered conversation. Now, however, all her efforts are concentrated on developing her argument.

‘I mean, we all, like, know that the Irish are spiritual and charming and fantastic story-tellers, which is why they’re such brilliant writers? Why is that a stereotype? It’s, like, common sense? And if we need a reason for it, surely it’s because they’re Celts? And the Celts are amazingly imaginative and sensitive. And surely they have an oral tradition? You know what I mean?’

While she’s speaking, the ripples of amusement throughout the room suggest that her views are known and affectionately tolerated. Steve takes in her long, crinkly red hair, pale freckled face and light blue eyes. She could be Irish or, since her accent – English public school overlaid by London demotic – doesn’t suggest that, of Irish descent. Whatever her racial identity, however, she favours a Camden Market ethnicity in dress. A sheepskin Afghan coat, which must take real dedication to wear on such a close, muggy day, is slung over the back of her chair, while a flowing Indian print dress, decorated with quantities of beads, scarves and silver bangles, covers her soft, full figure.

Steve’s own particular brand of Irish romance (though it’s a term he’s reluctant to use), rooted as it is in historical reality, makes him particularly hostile to the one so aptly embodied in this flabby, messily eclectic girl.

‘It’s as well Phoebe doesn’t realise she’s just made his point for him,’ Nick says to Pete. ‘She’s told him pretty much everything he needs to know about her.’

‘He’s wondering whether he’s got an alien in the class,’ Pete whispers back. ‘Phoebe will challenge his rationalism, if anybody can.’

What’s challenging Steve about Phoebe, however, is the niggling sense that he knows her from a different context. Then he remembers the scene under the chestnut tree and places her as the Dionysian figure in the summer dress, with the wreath of daisies in her hair, holding the jug of Pimm’s. The picturesque stillness of that moment, snatched from time and larger circumstance, evaporates in the human reality of this girl, who is mouthing clichés as though nobody has thought of them before.

When he replies, he ignores Phoebe and addresses the group more generally. ‘The Celtic origins of Ireland were so distorted and sentimentalised in the nineteenth century that they exist for us as myth rather than useful historical reality.’

While he is speaking, however, he thinks of the other girl, who claimed his attention for herself, not as an element in a larger picture, beautiful in any setting, her face enlivened more by thought than by the occasion. He glances quickly round the room, to see if she, too, is there, and as his eyes come to rest on her, the girl next to Phoebe, who has been keeping her head down, resisting her companion’s attempts to distract her, looks up. She is unmistakably the girl in the black jeans and white T-shirt.

His eyes meet hers and, at this closer range, he sees their clear, dark blue, set in a small face of perfect symmetry. He notices, as he did before, a remarkable self-possession; that she is unusual in being able to look at another person without smiling. She seems to him complete and apart, isolated from the commonplace reality around her. The difference between her and Phoebe is so marked, the one so grossly material, the other light and ethereal, that they could belong to different species. Before she lowers her eyes he tries to read their expression but finds it unfathomable.

Steve’s total disengagement is broken abruptly by another student, a fierce-looking girl with many-studded ears. ‘Could I take us back to a point you made just a minute ago – about child abuse among priests weakening the power of the Catholic Church? I’d say that you were taking too rosy a view of modern Ireland in implying that all that – the power of the Church and of patriarchy generally – is now in the past when Irish women are still denied the right to abortion.’ Emma Leigh is a notable feminist, women’s officer in the union and scourge of any lecturer who fails to give due prominence to the female perspective.

Startled out of his reverie Steve, who prides himself on his sharpness and speed in argument, finds it difficult to adjust to the change in topic. When his brain clears, he is immediately irritated by the stridency of this young woman, so different from the stillness and quiet of the other, whom he has been contemplating with such pleasure. That doesn’t stop her being right, of course. All his life he has been a champion of women’s rights, but her intervention suddenly seems like a meaningless cliché when set against his own recent experience of Ireland.

Forcing himself to look at Emma, who is sitting back in her chair – smirking with satisfaction, it seems to him, at having landed a punch – he says, ‘I don’t think that’s an issue that can be discussed without considering the full complexity of modern Ireland.’

His manner is dismissive, one that he perfected early in his career for crushing older colleagues, who were forced, often against their better judgement, to concede that he knew more than they did. Emma, although silenced for now, doesn’t conceal her outrage, and may well prove a tougher opponent than the likes of Rowe. And although most of the group are relieved by this reprieve from Emma’s agenda, which has been known to dominate entire sessions, some see that Steve has been wrong-footed, that in failing to give modest support to Emma’s views, he has violated his own known principles. Are they to take it that he is always right, even when he is wrong?

Smiling now, as though aware that he has lost ground, Steve says, ‘I suggest that we turn aside from these general observations, seductive though they are, and look at the first text on your syllabus, Swift’s Modest Proposal, published in 1729 – or, to give it its full title, A Modest Proposal for Preventing the Children of poor People inIreland, from being a Burden to their Parents or Country; and for making them beneficial to the Public. All beginnings are arbitrary, of course, but for me Swift marks the start of an authentic tradition of Irish writing in English.’

On the subject of Swift, their first writer, and Swift’s famous essay, their first text, Steve becomes particularly animated. When Pete asks whether Swift, a member of the Protestant Ascendancy, was ‘really’ Irish, Steve replies, ‘It’s difficult to say what he “really” was, just as it isn’t always easy to decide what he “really” thought, because he occupied some kind of boundary between competing versions of reality. On the one hand he was an Anglican clergyman who tried to gain preference in London, to be close to the centre of power. On the other, his experience of Ireland made him an increasingly robust critic of English policy there. Like a number of Anglo-Irish writers – Beckett, Wilde, Yeats – he was a master of assumed identities and used them to destabilise the reader’s sense of reality within the text.’

Some of these contradictions belong to Steve too: he craves to be at the centre, where the action is, yet has made his reputation by championing the marginal and silenced. Unlike Swift, who was born in Ireland, he has no claim to an Irish identity, yet speaks as though he alone can get beyond the disfiguring stereotypes to an understanding of the ‘real’ Ireland, even though he rejects the validity of such a concept on theoretical grounds.

There follows a brief discussion on whether Swift was mad – Phoebe remembers a television programme to that effect – and on his persistent use of irony, ably led by Nick Bailey, who shows welcome signs of intelligence. As Nick is speaking, Steve recognises him, and his friend Pete, as members of the group under the chestnut tree, and tries to resist the temptation to speculate on their relationship with ‘his’ girl, who still hasn’t spoken, though she smiles when Pete takes over from Nick the lead in discussion.

‘I really like the way he softens you up,’ says Pete. ‘The voice or speaker or whatever he is goes on about how sorry he is for the Irish and how they can’t feed their children and there’s no work for them, and he’s come up with a solution for making the children useful.’

Steve nods. ‘“Sound and useful members of the Commonwealth” is the ideal proposed.’

‘Right,’ says Pete. ‘And you think he’s going to come up with some kind of light, clean industry – children did work at this time, didn’t they? – maybe with some kind of government investment, and instead he suggests that as soon as they’re a year old, and won’t be, like, breast-fed any more, Irish babies should be eaten.’

‘Why babies?’ Steve asks.

‘Well, I suppose you wouldn’t fancy them when they’re any older,’ Pete replies. ‘He says that fourteen-year-old boys would be a bit stringy.’

When the laughter has died down, a girl Steve hasn’t noticed before – small, with dark, curly hair and, Steve thinks, what children’s books used to describe as a ‘merry’ look, the kind of girl who is usually the heroine’s confidante – takes the audacious step of topping Pete’s remark: ‘But at least they’d be organic.’

Instead of just laughing with the rest, Pete beams his appreciation at Annie Price, whose remark will be remembered as one of the highlights of the course. Their paths haven’t crossed much before, but each recognises in the other a kindred spirit and their partnership will be one of the success stories of the year.

Then, just as Steve thinks that the class will be over before ‘his’ girl has spoken, she intervenes in a way that alters the course of the discussion.

‘Surely we’re outraged because babies are so vulnerable,’ she says, and as she speaks two little spots of colour rise to her cheeks. There is an awkward sincerity about her, as though it requires effort for her to speak so publicly, but she’s been driven to it by her concern for babies. Steve notices none of this, however, or that the self-possession he’s attributed to her isn’t total. What is electrifying is her accent, which is immediately identifiable as Northern Irish; and Steve, who is the least superstitious of men, has the strange and elating sense that fate has intervened on his behalf.

What he’d really like to do is end the session now, take her off and find out everything about her, but instead he nods enthusiastically and says, ‘It is outrageous, of course, you’re right to remind us of that, and the more so because it’s shockingly funny. I’m sorry, you didn’t introduce yourself…’

‘Nora. Nora Doyle,’ the girl says, looking at him levelly without smiling.

There is a suspended moment of silence throughout the room as they observe Steve’s reaction. It’s known that Steve is writing a book about Joyce, and that Joyce’s wife, Nora, was the model for Molly Bloom. And although barely a handful of them have read Ulysses, more have read Molly Bloom’s notorious soliloquy, whose scatological preoccupations couldn’t be further from what they know of the demure and reserved Nora Doyle.

Steve acknowledges the connection with a raised eyebrow and a smile. ‘It’s good to have an Irish member of the class. You must be sure to keep us all on our toes.’

At this point Emma weighs in with the claim that no woman would write about the eating of babies, even with satirical intent. And while Steve could point out that such unfounded assertions are inappropriate in academic discourse, he privately acknowledges that, outside this rarefied field, she’s probably right, and lets it ride, hoping that indulging her in this instance will go some way to placating her.

‘Killing babies is about the most transgressive of all human acts,’ says Nick, ‘but surely the whole point of this piece is that the Irish are described as though they’re animals, of a different species, and it’s a small step from that to see them as a saleable, and edible, commodity.’

‘That’s right,’ says Steve, oblivious of his own recent, private relegation of Phoebe to a different species from Nora. ‘What’s interesting is that the speaker seems initially to be complicit in the way the English, or the Protestant Ascendancy, view the Irish, but then manages to turn the argument against them by taking their attitude to its logical conclusion. He’s saying, in effect, that you might as well be eating them for all the effort you’re making to keep them alive. And, of course, history tells us – I’m thinking here of the Holocaust or apartheid – that the persistent use of animal imagery creates a climate where those others can be treated in any way that the ruling hegemony sees fit.’

Then, just when he’s on the point of dismissing them, Nora speaks again, but this time she is almost playful; he wonders whether she is teasing him. ‘I hope we shan’t be seeing the Irish as victims of the English all the time,’ she says.

Steve is surprised, forced to confront the unwelcome possibility that, despite her name, she might be Protestant. ‘Unfortunately that has been the history of the two countries.’

‘Just as long as we acknowledge that the process we’ve just been discussing isn’t all in one direction. It’s true that the Irish haven’t had the opportunity to oppress the English, but they might take a certain comfort in seeing them as animals.’ Then before he has framed a reply, she says, ‘I don’t suppose that the IRA bomber sees – or saw, if the peace process holds – his victims as human beings with the same capacity for suffering as himself.’

Relieved, Steve says, ‘None of us would argue with that, although we still have a responsibility to investigate the cause of the violence.’

As he finishes speaking, he gives a nod of dismissal, turns away from the class and walks over to the window. He is not quite as absorbed in his own thoughts as he seems: he is aware of his students packing up their bags, pulling on jackets and forming into groups as they drift out of the room. He turns to face Nora as she, too, makes her way between the seats.

‘I just wanted to repeat what I said earlier,’ he said, ‘that it’s good to have an authentically Irish member of the class. At least, I assume you’re the only one, unless there are others who are keeping their heads down.’

‘I wouldn’t know,’ she says, attentive but not smiling. Steve realises that, although he has seen her smile, she hasn’t yet smiled at him, and wonders how long he’ll have to wait for that. ‘I’ve come into contact with most people in the group, but not everybody. And there are what you might call the London Irish, like Nick.’

‘We don’t get a large number of Irish students here, though there are a few. May I ask what brought you?’

‘Oh, this and that. You know.’

‘You thought you’d spread your wings?’

‘Something like that.’

This is much harder work for Steve than the class he’s just given, but he persists none the less. ‘Well, we’re honoured. These are exciting times in Northern Ireland. You must feel you’re missing out.’

‘You mean with the Assembly and all?’

‘Well, yes. You are in favour of what’s going on?’

Nora hesitates briefly and, when she speaks, chooses her words with care: ‘My family’s Catholic. On the whole, Catholics are more likely to support the Good Friday Agreement.’

Steve smiles his relief, although he is puzzled by the form her reply takes, as though she is at pains to give as little information as is consistent with candour. ‘I thought as much. Your name, I suppose. It tends to be something of a giveaway in Ireland.’

‘Well. Certainly according to Seamus Heaney it does, though I’ve never been stopped by an RUC man.’

‘No, I suppose not. Young women aren’t usually thought to pose the same kind of threat as young men.’ Finding nothing else to say, and uncomfortable at her reluctance to volunteer any information about herself – a rare characteristic in his experience of young people – Steve releases her. ‘Well, I’ll see you next week.’

He watches her leave the room and notices that Phoebe Metcalfe is just outside the door, waiting for her. Not for the first time he wonders at the friendships formed by students and remembers some of the people he has had to avoid since Oxford. He gives them time to move on – he wouldn’t put it past Phoebe to waylay him and offer him her views on the little people – before picking up his helmet and satchel and leaving.

Half an hour later, Phoebe, Nora and Nick are seated at a Formica table in Marco and Gianna’s, the local Italian coffee bar. Usually Pete would be with them, but when last seen he had given them a distracted wave as he chatted up Annie Price. They are all drinking cappuccinos, and Phoebe, having declared herself to be ‘sinking’ with hunger, is eating a large cinnamon Danish that her friends have declined to share.

‘So, what did he want?’ Phoebe asks Nora, not for the first time, but now that they’re seated Nora can hardly evade the question. Phoebe’s learned from experience that Nora will give away as little as possible without appearing eccentric, and so attracting an even more unwelcome degree of attention; persistent questioning usually produces some result, however grudging.

Nora takes time to form her reply. Her manner, as so often, suggests someone much older. ‘He wanted to make sure that I was a Catholic.’

Phoebe’s round face, pink now from the coffee and the steaminess of the atmosphere, puckers in bewilderment. With Nick and Nora she often seems like a child, puzzling out the ways of the adult world. ‘But why? He doesn’t strike me as someone who cares about religion. Is he going to ask all of us? Is that allowed?’

‘It’s because he doesn’t want the embarrassment, some way into the term, of finding out that he has a wicked Ulster Protestant in his midst,’ explains Nick.

‘But why does it matter?’

‘Because it would be politically compromising for him to single out Nora as a favoured student, then find that she was on the wrong side.’

‘But what does politics have to do with religion?’ Phoebe asks, but before either of them can answer, says, ‘On second thoughts, don’t bother. I wish he’d stop banging on about it, whatever. I thought this was meant to be a literature course.’

‘Everything is political for Steve, but when he comes to Ireland he happens to be right.’

Nick is watching Nora as he says this, but she is staring absently into the remains of her cappuccino. Like Steve, he has given some thought to the nature of Nora’s friendship with Phoebe, and thinks he has arrived at a partial explanation. Phoebe, for all her questions, is fundamentally incurious. As on this occasion, she dismisses any information that is incompatible with her worldview. He judges that this suits Nora well. In the year he’s known her she’s been persistently evasive about her background – remarkably so, given that her accent immediately identifies her as coming from one of the few parts of the United Kingdom that impinges on everybody’s consciousness.

She is sometimes eager, as she was in today’s class, to express a view on Ireland, often with the implied suggestion that the English fail to understand it, then seems to regret drawing attention to herself. Always her opinions on Ireland are cast in strictly impersonal terms, as though she has arrived at an opinion through studying the subject rather than as a result of experience. As far as he can remember, she has never volunteered an anecdote about her childhood or parents, the kind of stuff that’s common currency among students who, in the early days of friendship, like to define and establish who they are. When such occasions arise, and members of a group try to outdo each other with stories of an outrageous parent or eccentric upbringing (for everything is exaggerated in the interests of glamour), Nora falls silent, or turns the conversation, or makes an excuse to leave. It’s as though she’s afraid of being found out.

There is some discussion between them about whether Nora can’t or won’t talk about herself. Pete has always subscribed to the view that Nora doesn’t choose to talk, that she preserves her mystery so that they (the men particularly) can project their fantasies on to her. If she were known to have had a conventional middle-class background, albeit in a different place, she would be like the rest of them, apart from her extraordinary looks, of course.

Nick isn’t so sure. Within the limits she has set herself, Nora is often touchingly eager to please, almost too compliant to other people’s wishes – a characteristic that Phoebe has been quick to spot and ready to exploit. He thinks that Nora is genuinely inhibited, but by what he hasn’t yet decided. Privately – because in a gossipy environment like a university where any hint of the glamorous, subversive or criminal is immediately seized upon and enlarged – he’s speculated about an IRA connection. It’s difficult to imagine Nora actively involved, but her conformity to the role of model citizen and outstanding student – like him, she gained a first in her first-year exams – would be the perfect cover.

On the other hand, the revulsion she sometimes expresses against terrorism could be genuine. Sometimes he thinks that her adaptability, her unwillingness to impose her will, might indicate that she’s been a victim of aggression; that she’s used to keeping her head down. Whatever the cause, it’s thought that she never goes home and, as far as he knows, she spent the entire summer working in a hotel in Devon, presumably to help pay her way through college.

He wonders what it would be like to have a relationship with her. The idea certainly appeals, but she seems to be as inhibited about sex as about everything else, and Nick is so used to girls who leave no room to doubt their willingness that he’s not sure how he would begin to break down her reserve.

Putting aside for the moment thoughts about that particular reserve, Nick decides to chance his luck with a direct question about Ireland. ‘So tell me, Nora, how, in your opinion as an insider, did Steve tackle the Irish question?’

She turns her head judiciously to one side, exactly as she might, he thinks, if she were marshalling an argument for an essay or a class presentation. It occurs to him for the first time that, although she never draws attention to her successes, she is most at ease with academic discourse, as though she has developed that side of her character at the expense of the rest.

‘He talks a lot about stereotypes, and how they tell us nothing about the country, only about the prejudices of those who subscribe to them, but he has all the prejudices about the Irish of the liberal London intelligentsia – how we’re all victims and it’s all the fault of empire, as though there’s no such thing as personal responsibility and morality. Irish Catholics are all angels, and all the others are now animals. He’s just turned the traditional model on its head.’

He wants to ask her, ‘Then what, for Christ’s sake, is the reality, or your reality?’ but knowing that will get him nowhere, says, ‘In his own way, Steve’s an old romantic. He may subscribe to a cool, post-structuralist approach, but you could see that he fancies himself as a bit of a Swift – an outsider who uses his mordant wit and superior intelligence to see further and deeper than an insider.’

‘I don’t think he’s at all romantic,’ says Phoebe. ‘I’d heard so much about him that I was expecting something more…’ Unable to find the word she wants, she lifts her arms, then drops them to express her disappointment, only just missing, in their cramped surroundings, the empty cups and plate on the table. ‘I thought he was a bit of a cold fish.’

‘So what was he like – close up and personal, I mean?’ asks Nick.

‘He looked older,’ Nora says. ‘Tired, as though a couple of hours’ work had exhausted him.’

‘I suppose he’s getting on a bit. It’s hard for ageing rebels like him to know what to do with themselves, with younger generations yapping at their heels. Do they go back on everything they’ve believed in, like those Old Labour people trying to look comfortable in a New Labour government? Or do they find a new cause for themselves? I guess that’s why he’s taken on Ireland. At the moment it’s sexier than Marxism, but I’d say he’s a bit of a latecomer to the game. Wouldn’t you, Nora?’

Nora merely shrugs, as though she’s reached the limit with this particular conversation. What she doesn’t say is that, throughout the session, Steve kept reminding her of her father. She doesn’t say it because she hasn’t yet found a way to talk about home, and to explain the resemblance she would have to tell her entire family history.

Ballypierce (#ulink_c209da3b-1559-5cf1-a634-6a7608655bf3)

Nora’s earliest precise memory is of a day shortly before the birth of her brother. She remembers that the baby’s imminence hung in the air that afternoon, charging the atmosphere and releasing in her father a restless energy. Always a boastful man, his pride in himself, and in her, seemed to know no bounds. And while she is sure, without having a clear memory of them, that there were other, similar occasions before that afternoon, she knows that there were none afterwards. This, she thinks, is why she remembers the afternoon so clearly, that it marked the end of an era: with Felix’s birth, another, altogether different, phase in their lives began.

She remembers sitting on the counter in her father’s shop, surrounded by a group of admiring men. The pretext for her being there was that her mother needed to rest. Her father had come home for lunch, as he was in the habit of doing when it was just the three of them, leaving in charge one of the succession of young women that he had working for him. His routine was sufficiently established for people to know not to take in their prescriptions over the dinner hour, when many of the other shops, which couldn’t afford extra help, closed. Her mother had told him that the midwife had called, that her blood pressure was up again and she needed rest.

‘Will I take the wee girl back with me, Bernie?’ he had asked.

‘Since when have you needed my permission?’ her mother had replied.

It was acknowledged between the three of them that she and her father were a team, and while her mother boasted of this to her acquaintance – the degree of interest that Gerald took in his four-year-old daughter was sufficiently unusual to arouse the envy of other women – her resentment at being excluded sometimes surfaced at home. Nora was hoping that the baby would be a boy, not for herself or her father, who were perfectly content, but for her mother. She and the baby boy would then form another self-contained team and the family would be perfectly balanced.

So Gerald took her back with him and she spent the first hour or so sitting at a little desk that Gerald had rigged up for her in the corner, drawing and doing a few sums that he had set her. Really, this was only marking time until a sufficient crowd had gathered, mostly other shopkeepers who had left their wives, now released from kitchen duties, in charge while they slipped out for half an hour.

Without understanding at that point precisely why, she knew that it was a mark of her father’s importance that his shop acted as a magnet for men with time on their hands during the slow, early-afternoon hours before the schools were out. Ballypierce was a largely nationalist town where incomes were low and trade rarely buoyant. But Gerald, who had grown up and gone to school with many of the other traders, was a great man among them, a pharmacist who had gone to Belfast to study. They could leave their shops, but he had to stay at his post to make up prescriptions, apart from the hour dedicated to lunch, when he insisted on a home-cooked meal. He was one of the few whose family didn’t live above the shop, having chosen instead a new bungalow, built to architect’s specifications on a hill at the edge of the town with a view over the valley. The flat above the shop was let so he was a landlord in addition to his professional status.

People might not have jobs but they still became ill and needed medicines that the Health Service funded so, whatever else was happening, the Doyles were always comfortable. And Gerald, instead of joining the Protestants at the golf course or sailing club, as he was entitled to, had stayed one of them, always ready for good craic, always pleased to see an old friend who dropped in. By comparison with others in the town, his shop was like a palace, with large plate-glass windows on both sides of the door, all the fittings built to the highest standards, always sweetly smelling from the soaps and perfumes and ladies’ cosmetics, and gleamingly clean, because Gerald insisted on the highest standards of hygiene and had been known to sack a girl whose hair always looked unwashed. And when the party was under way, Gerald would send his assistant into the little kitchenette to make them all cups of tea.

That afternoon Nora was lifted on to the counter, the one with the little room behind it where Gerald made up his prescriptions. She was wearing a navy blue smocked Viyella dress with matching tights – Gerald had requested that Bernie change her before they left – and her hair was tied back into a tight ponytail. When Gerald had started this routine, as soon as she could walk and talk and had no need of nappies, she would recite a few nursery rhymes or count to a specified number, but since he had taught her to read she was always required to show off her current level of attainment. That afternoon she read from a simplified picture-book version of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.

‘You’re a great girl, so you are,’ said Malachy McGready, the greengrocer. ‘It’s no wonder your daddy’s so proud of you. But if he gives you books like this to read, you’ll start to think you’re a wee Brit. You won’t find many Susans and Edmunds around here.’

Gerald gave a satisfied little smirk, having come prepared for just this rebuke. ‘Don’t you know who C. S. Lewis was?’ he asked. ‘Your man was born in Belfast and ended up a professor at Oxford.’

This was greeted with smiles all round, not so much that one of their own (they were by no means convinced that a man who wrote like this could be so described) had achieved so much in the wider world but because Gerald had outmanoeuvred them yet again. These afternoon gatherings, whether Nora was present or not, were not so much exchanges between equals, as enactments and affirmations of Gerald Doyle’s superiority, and if he had ever been caught out or bettered, they would have felt keen disappointment. Malachy’s scepticism was, none the less, a necessary component of the drama.

‘Is that what you’re after for the little lady here – for her to be a professor at Oxford? What’s wrong with Queen’s, or Trinity, if she must leave home?’

‘I want the best for her, and she deserves it. And if when the time comes the best is still Oxford, then we’ll have to make the sacrifice.’ As he spoke, Gerald looked down fondly at Nora, who sat swinging her legs and munching a biscuit.

‘But tell me, Gerald, your man, Lewis,’ said Malachy, who had picked up the discarded book and was peering at it to make sure that he had the name right, ‘would I be right in thinking he was a Protestant?’

‘Well, you would, of course. How many Catholics do you suppose went from here to Oxford before the war?’ There was that in Gerald’s manner of a man who is playing a game so elaborate that his opponent, at the moment of thinking he has caught him out, finds himself the victim of superior strategy. Gerald’s air of victory took no account of his having ignored the drift of Malachy’s argument. Then, with a sudden shift of tactics, he addressed the point that Malachy had been labouring. ‘You want to know why I give Nora stuff like this to read? Because it’s what the children of the ruling classes read, and if you want them to get on in that world, you give them a head start. Rather than have her, at forty, feeling aggrieved at the way the world has treated her, I want her out there with the best of them, showing what can be done.’

A number of them felt mildly rebuked by this, but they would no more have thought of challenging him than they would a geometric theorem or a doctor’s diagnosis. Gerald loved imparting information, surprising people, overturning their expectations; and while he needed a patsy like Malachy in order to shine, none of them was prepared to risk losing his goodwill and, with it, the dim reflection of his glory that touched them as welcome members of his circle. They enjoyed the sense of inclusion that allowed them, later, to say to a wife or customer, ‘Gerald Doyle was saying to me only the other day…’ Besides, they believed, because he had told them, that his was the voice of science, reason and progress, and they were all reluctant to pit themselves against these mysterious forces. If he seemed more than usually pleased with himself that day, they put it down to the imminently expected baby, and were prepared to indulge him.

‘The teachers will have their work cut out when she starts school,’ said Liam Doherty, who owned the best of the nationalist bars. ‘You haven’t left them much to teach her.’

‘It’s a problem, right enough,’ said Gerald. On this particular point, if on no other, he was prepared to acknowledge himself baffled. ‘But there, I almost forgot. I’ve been looking into Shakespeare with her, and her memory’s prodigious. Come on, darling,’ he said to Nora, as he lifted her down from the counter and gestured to his companions to clear a space around her. ‘Show us how you do Shylock.’

Nora composed herself briefly, then stretched our her arms and recited, ‘“I am a Jew. Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions? Fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer, as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us, do we not die? And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge?”’

After the first two short, monosyllabic sentences, this was delivered in the chanting monotone of small children reciting prayers that are beyond their understanding – a style that she had learned not from Gerald or from her mother but at the little nursery she attended in the mornings, where prayers were part of the routine.

Then, after a look of encouragement from her father, she shifted her position, hunching her shoulders into a forward stoop and holding out her right hand in a grasping gesture. ‘O my ducats, O my daughter, O my ducats, O my daughter,’ she growled, with as much depth, intensity and malice as she could muster. When she had finished, she ran over to her father and clutched him round the knees.

Her audience was genuinely speechless, not sure what to make of her performance, for all its precociousness. As was customary, it was Malachy who found a way of expressing their doubts: ‘This Shylock,’ he said tentatively, ‘wasn’t he a fellow?’

Gerald nodded. ‘The Jewish moneylender. The first Jew in literature, when writers weren’t afraid to tell the truth.’

‘She says it bravely,’ said Malachy. ‘I doubt there’s another girl her age who could match her. But were there no girls’ parts you could teach her?’

Gerald nodded slowly. ‘I looked into it, of course, but most of the young girls in his plays are only interested in love and such like and I didn’t want her head filled with that kind of nonsense. Now Portia’s different, of course. I tried her out with the “quality of mercy” speech, but there were words that even she couldn’t get her tongue round, and you have to be careful with a child like this not to tax the brain with more than it can handle.’

There were murmurs of approval for Gerald’s commendable fatherly concern. These he stilled by raising a warning finger. ‘But don’t make any mistake about it,’ he said, ‘They can’t learn soon enough how the world works.’

‘You want her to know about the Jews?’ asked Liam, doubtfully. This struck all of them as an entirely unnecessary lesson. As Irish Catholics, they had never questioned the received wisdom that Jews were treacherous, money-grubbing and only out for themselves. On the other hand, none of them had ever met a Jew, or was likely to do so.

‘I want her to learn something much more useful than that,’ said Gerald, who was, as usual, a step ahead of them. ‘I want her to realise that, not just in this instance but in almost everything you could name, people’s instincts are being suppressed by those who think they know better. Now, take the Jews.’

‘I’d rather not, thank you,’ said Tom O’Neill, the butcher, raising the biggest laugh of the afternoon.

‘Very well, then. Take Shakespeare and the Jews. Now, the English are only too ready to accept what he has to say about England – all that jingoistic nonsense about sceptred isles and brave English soldiers throwing themselves into the breach, without knowing that he was more or less forced to write it, but they don’t want to hear what he says about Jews. And yet the man was ahead of his time. He said – you heard the girl – that they’re not animals, they’re human beings, like the rest of us. They bleed, they laugh and all the rest of it. I’ll go along with that. But – and it’s an important “but” – revenge matters as much to them as food and drink, and they don’t have the same feelings for their flesh and blood as we do. His daughter runs away, and all he can think about are his ducats. But you’re not allowed to say that any more, not in England or the States. No, I just want her to learn to respect the evidence and to be fearless in saying what she knows to be right. That’s all. The Jews are incidental, they’re just an example.’

Signalling that the session was over for the afternoon, he lifted Nora up and held her, legs dangling, face on a level with his, as if he were displaying her. ‘And I want her to know that she’s more precious to her Daddy than anything else in the world, even ducats. Especially ducats.’

There was no doubt that they made an appealing picture – Gerald fresh-faced, well-tended (it was rumoured that he took home some of the lotions and creams from the shop for his own skin, and that he needed a wife at home all the time to iron the shirts that he insisted on wearing, clean, every day), dressed in the finest tweed, linen and leather, a man in the prime of life, and Nora as dainty and delicate as a little fairy.

‘And what if the next one’s a boy?’

‘It’ll make no difference. There isn’t a boy who can match her.’

Nora’s companion memory to what was to be the last occasion when her father took her to the shop with him to demonstrate her cleverness fell within days of the first. The two stand side by side, an end followed by a beginning. Everything about that second day was different, from the moment she woke up and sensed an alteration in the sounds of the house. Still in her pyjamas, she wandered through into the kitchen where her mother would be preparing the breakfast – hers to be eaten at the kitchen table, her father’s to be placed on a tray and carried through to him in the bedroom. Instead of her mother, however, there was Mrs Daly from next door, a woman of late middle age, whose children had grown and left home, moving about and, as she described it, making herself useful.

‘Now, pet, you mustn’t fret,’ she said. ‘Your daddy’s taken your mummy into the hospital, and when she comes home, please, God, she’ll have a new wee brother or sister for you. Now, what would you like for your breakfast? Will I cook you an egg or fry you a rasher?’

Nora sat and spooned cereal into her mouth while Mrs Daly pushed a cloth over the work surfaces in a show of activity. She wondered how her mother felt about having another woman in her kitchen. She knew her to be ill at ease with her neighbours in this most select area of the town and that she suspected Mrs Daly, who had time on her hands and an imagination actively engaged in the lives of others, of a tendency to snoop.

Bernie often said that her neighbours regarded her as fortunate, not just because they lived so well but also because, as an exceptionally pretty young woman, she had caught Gerald’s eye when she had come to work as an assistant at the pharmacy. And she suspected that ‘fortunate’ carried connotations of something in excess of what she deserved. Convinced that everybody around her was looking for evidence against her, she was an anxious, if unenthusiastic housekeeper, and kept her family, modest country people of whom she was now ashamed, at a distance.

There was to be no nursery this morning, and Mrs Daly was clearly relieved when, after breakfast, Nora demonstrated that she was quite capable of amusing herself. Although she wasn’t very good at playing with toys, she had other resources, and after she had spent some time drawing and looking through books, she put on her rubber boots and jacket and wandered round the garden while Mrs Daly sat with yesterday’s newspaper at the picture window in the lounge, keeping an eye on her.