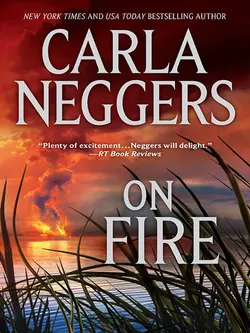

On Fire

Carla Neggers

In a tragic accident, Emile Labresque's research ship went down, killing a wealthy philanthropist and four crew members. Emile, his granddaughter, Riley St. Joe, and the captain, Sam Cassain, barely escaped with their lives. But a year later, when Sam's body washes up on a beach, it looks as if someone is trying to cover up murder…and all evidence points to Emile.Riley can't believe her grandfather is capable of the vicious crimes, and she is determined to clear his name. But when Emile disappears, Riley turns to the only person willing to help–John Straker, an FBI special agent, who is compelled to help Riley because of his friendship with the old man.Riley and Straker are total opposites from different worlds, but they have something in common–a determination to expose a murderer and save Emile's life…and a passion they're finding harder and harder to ignore.

Praise for the novels of Carla Neggers

“Readers have come to expect excellence from Neggers, and she delivers it here. The pairing of aristocratic spy Will with butt-kicking heroine Lizzie is inspired, and the multistrand plot is extremely absorbing.”

—RT Book Reviews on The Mist

“When it comes to romance, adventure and suspense, nobody delivers like Carla Neggers.”

—Jayne Ann Krentz

“Suspense, romance and the rocky Maine coast—what more could a reader ask? Carla Neggers writes a story so vivid you can smell the salt air and feel the mist on your skin.”

—Tess Gerritsen on The Harbor

“Well-drawn characters, complex plotting and plenty of wry humor are the hallmarks of Neggers’s books.”

—RT Book Reviews on Cold Pursuit

“Neggers’s engaging romantic mystery neatly blends fiction with authentic detail.”

—Publishers Weekly on Tempting Fate

“Readers will be turning the pages so fast their fingers will burn…a winner!”

—Susan Elizabeth Phillips on Betrayals

“[A] tight, twisty and exceedingly well-told thriller…a surefire winner.”

—Providence Journal on The Angel

“No one does romantic suspense better!”

—Janet Evanovich

On Fire

Carla Neggers

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

To my nieces and nephews: Blythe, Sarah Mae,

Tommy, Rose, Chris, Timothy, David,

Sarah Elizabeth, Emily, Dan, McKinzie, Scarlett

and Marena…and to Kate and Zachary…

you’re a great bunch!

Contents

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Prologue

R iley St. Joe sloshed through three inches of frigid seawater. The Encounter pitched and rolled under her, its old metal hull moaning and creaking as it took on more water. Trapped like rats on a sinking ship, she thought. Her stab at humor caught her by surprise—but it helped keep her on her feet as she made her way to her grandfather. They were in the diving compartment deep in the bowels of the ship, a raging engine fire and catastrophic flooding cutting them off from the rest of the crew.

After three decades at sea, the Encounter—the old minesweeper Emile Labreque and Bennett Granger had had refitted as an oceanographic vessel—was going down in the North Atlantic. There was nothing Riley could do about it. More to the point, there was nothing her grandfather, the stubborn, brilliant, visionary oceanographer Emile Labreque, could do about it.

She grabbed his thin arm. He was seventy-five, wiry and fit, and he had to know what was happening. He knew his ship better than anyone. He stared at the watertight door that had shut fast against the fire and flooding, sealing them in the bowels of the ship. “Emile, we have to take the submersible,” she shouted. “We don’t have any choice.”

“I’m not going anywhere. The pumps will handle the flooding. The crew will put the fire out.”

“The pumps won’t do anything, and if the crew’s smart, they’re getting into the life rafts now. Emile, the Encounter’s sinking. If we stay here, we’ll go down with it.”

He tore his arm from her grip. His dark eyes were wild, his lined, leathery face and white hair all part of the legend that was Emile Labreque. He took a deep breath. “You go. Take the submersible. Get out.”

“Not without you.”

“I need to see to the crew.”

“You can’t. Even if you could get the doors open, the fire’s too intense. And if you didn’t fry to a crisp, you’d drown. Sam will have to see to the crew.” Sam Cassain was the ship’s captain, but Emile would consider the Encounter and her crew his own responsibility. Riley struggled to stay on her feet. Rats. We’re trapped like rats. She fought off panic. “Emile—damn it, you know I’m right.”

He knew. He knew better than she that the Encounter was lost. An engine explosion, a spreading fire, a hull breach—they had only minutes. “The submersible’s only built for one,” he said.

“It’ll handle two. Sam would have sent out an SOS by now. The Coast Guard’s probably already on their way. They’ll pick us up before we run out of air.”

“We’ll have three, maybe four hours at most.”

“It’ll be enough.”

Emile placed a palm on the watertight door, shut his eyes a moment. The Encounter was as famous as he was, the base for his oceanographic research, the documentaries he’d taped, the books he’d written. Now, its day was done.

He turned to her. “We’re out of time. Let’s go.”

Five hours later, Riley numbly accepted a blanket from a Coast Guard crewman and wrapped it around herself. The crewman was saying something, but she couldn’t make out his words. She’d stopped shaking. Her eyelids were heavy, her heart rate steady. But her hands were clammy and very white, and she simply couldn’t make out what he was trying to tell her.

I must be in shock.

Her throat burned and ached from tension and fatigue, from gasping for air as oxygen slowly ran out in the tiny, cramped submersible she and Emile had shared for almost four endless hours.

“My grandfather.” She didn’t know if her words came out. “How is he?”

The crewman frowned as if she’d made no sense.

“Emile—my grandfather.”

“We’re going to get you some help, okay?” The crewman touched her arm through the blanket. “Just hold on.”

“I’m not hurt.” She felt as if she were shouting, but couldn’t hear her own words. “The crew—are they all right? They made it to the lifeboats?”

“Miss St. Joe—”

Something in his face, his tone, sent a stab of dread straight through her. Oh God. “How many? How many died?”

The eyes of the nearby crew turned toward her, and she realized she must have shouted this time. The crewman winced. He was Coast Guard all the way. Every death at sea pained him. He said nothing, and Riley knew. There had been deaths aboard the Encounter. Not everyone had made it off alive.

A man yelled, and she looked up and saw three crewmen holding back Sam Cassain. He was tall and tawny-haired, a thickly built man, a firebrand, a good captain with a propensity for mouthing off. He would speak first, think later.

Riley saw her crewman grimace, as if he wanted to protect her from Sam’s words. Too late. She could make them out clearly.

“Five died,” Sam yelled. “Five. And it’s your goddamned grandfather’s fault. The great Emile Labreque. He’s responsible. He knows it.”

“Who?” Riley clenched the blanket tightly around her, her fingers rigid, her stomach lurching. “Who died? Sam, for God’s sake—”

He couldn’t have heard her, but he shouted, “Bennett Granger’s dead. He fried in the fire. He never had a chance to make it to the lifeboats. Think Emile should be the one to tell your sister, your brother-in-law?”

Riley couldn’t speak. Bile rose in her throat. Bennett Granger was the chief benefactor and cofounder of the Boston Center for Oceanographic Research. He and her grandfather had been friends for fifty years. His son had married Emile’s granddaughter, Riley’s sister. God. Who would tell Matthew and Sig?

“Get him out of here,” her crewman shouted.

“You mark my words, Riley St. Joe,” Sam said, his voice deadly. “I warned Emile. I told him the Encounter was an old girl and we needed to take more precautions. He wouldn’t listen. His mission always came first. Now five people are dead. That’s on his shoulders, not mine.”

Riley struggled to get to her feet. The crewman held her by the elbow, keeping her from going after Sam—or from passing out. “Don’t,” he said softly. “There’ll be an investigation. This will all sort itself out in due time.”

“But Emile—my grandfather—”

“He’s in the infirmary. He’ll be okay.”

Every part of her, mind and body, was spent. She couldn’t even lick her parched lips. “The fire was an accident. It wasn’t Emile’s fault. It wasn’t anybody’s fault.”

The crewman made no response, but his eyes told her everything. He agreed with Sam Cassain. He believed Emile Labreque was responsible for the explosion and the fire that sank the Encounter and killed five people.

Riley clutched the folds of her blanket. Bennett. Oh, God. She wished she could start the day over and save the Encounter, save Bennett, save the crew. But the old ship was gone, and five people were dead, and Emile…her grandfather, she thought, was doomed.

One

R iley ignored the slight tremble in her hands and jammed the two ends of her high-performance paddle together. She zipped up her life vest. There was no reason to be nervous. She’d kayaked the coves and inlets of Schoodic Peninsula since she was six years old. Today’s conditions were near perfect: a bright, clear, still September morning, halfway between low tide and high tide.

She squinted at her grandfather, who’d come down from his cottage to the short stretch of gravelly beach to see her off. “Come with me,” she said.

He shook his head. “You go on. You need to get back out on the water.”

“I’ve been out on the water. Caroline Granger had us onto her yacht for a cocktail party Friday night.”

“Cocktails.” Emile snorted. “That’s not getting out on the water.”

She knew what he meant. She hadn’t been on a boat, a ship, even a kayak, since the Encounter disaster a year ago. On the Granger yacht off Mount Desert Island Friday night, she couldn’t make herself go below. She’d never been claustrophobic, not until the watertight doors had shut her and Emile into the diving compartment, not until the two of them had endured the hot, cramped, terrifying hours in the experimental submersible.

This had to end, she told herself. She was a scientist, director of marine and aquatic animal recovery and rehabilitation at the Boston Center for Oceanographic Research. She couldn’t get spooked about the water.

“I shouldn’t kayak without a partner.”

Emile shrugged. “You’ll stay close to shore. Just watch out for fog rolling in later.”

“You’re sure you won’t come with me?” she asked him.

“I can kayak anytime I want.”

One of the perks of his exile, he seemed to be saying. After the disaster of the Encounter, Emile Labreque had shocked the world by retiring to the Maine fishing village where his family had settled generations earlier. It had been his home base for years; he owned a small cottage, where Riley and her sister had spent summers growing up. He looked after a small, private nature preserve on a part-time basis. The last hurrah of a legend.

He eyed Riley as she dragged her shocking pink, siton-top ocean kayak to the water’s edge. He wore his trademark black Henley and khakis, and at seventy-six, he was as alert and intense as ever. She’d inherited his lean, wiry physique, his dark hair and eyes, his sharp features—and, some said, his single-mindedness.

“You’re planning to stop on the island?”

She nodded. “I packed a lunch. If the fog doesn’t roll in, I’d like to have a little picnic on the rocks, like the old days.”

He gazed out at the water. The bay sparkled in the morning sun. Labreque Island was farther up the point, almost at the mouth of the bay—a tiny, windswept landscape of rock, evergreens and sand that had been in Emile’s family since the turn of the century.

“I should warn you. John Straker’s staying at the cottage.”

“Straker? Why? What’s he doing back here?”

“He took a couple of bullets a while back. He came home to recuperate. I let him use the cottage on the island.”

Riley digested this news as if it were a hair ball. John Straker wasn’t one of her favorite people. He’d left the peninsula years ago to join the FBI. A lot of people in his home village couldn’t believe the FBI had accepted him. She’d only seen him a few times since. “Who shot him, criminals or his friends?”

“A fugitive who took a couple of teenagers hostage. It had something to do with domestic terrorism.”

“Right up Straker’s alley. Anyone else hurt?”

Emile shook his head. “You know, John’s not much company on a good day.”

“This is true. I’ll just have to keep to the other side of the island. He won’t even know I’m there. I didn’t realize the cottage on the island was still inhabitable.”

“He’s fixed it up a bit. Not much.”

“How long’s he been out there?”

“Since April.”

She shuddered, then grinned at her grandfather. “Well, tough. I’m not afraid of John Straker. Will you be here when I get back?”

“I doubt it.”

She hesitated, debating. “I’m stopping in Camden on my way back to Boston. Is there anything you want me to tell Mom and Sig?”

“No.”

Riley nodded without comment. Perhaps, she thought, too much had been said already. Her mother and sister—Emile’s only daughter and older granddaughter—blamed him for the Encounter, for Bennett Granger’s death, for the deaths of four crew members and friends, for Riley’s near death. For Emile’s near death and the shattering of a lifetime’s reputation.

Of course, everyone blamed Emile for the Encounter. Except Riley. Sam Cassain’s assessment of what had happened—his conviction that Emile had cut too many safety corners—wasn’t enough for her. She needed hard evidence before she could damn her grandfather to the pits of hell. But she was in a distinct minority.

Emile wished her well and started back along the path up to his rustic cottage. Corea, Prospect Harbor, Winter Harbor, Schoodic Point. These were the places of her childhood, tucked onto a jagged, granite-bound peninsula, one of dozens that shaped and extended Maine’s scenic coastline. Riley knew all its inlets, bays and coves. It was here she’d discovered her own love for the ocean, one that had nothing to do with being a Labreque or a St. Joe but only with being herself.

It was here, too, that she’d drawn blood in her one and only act of out-and-out violence, when she’d hurled a rock at John Straker. He was sixteen, she was twelve, and he’d deserved it. His own mother had said so as she’d handed him a dish towel for the blood and hauled him down to the doctor’s office. He’d required six stitches to sew up the slit Riley had left above his right eye. She wondered if he’d had to explain the scar to the FBI. Amazing they’d let him in. Bonked on the head by a twelve-year-old. It couldn’t bode well.

Now he’d been shot. Domestic terrorism. She grimaced. Well, she had no intention of letting a cranky, shot-up FBI agent ruin her picnic on her favorite island.

She slid her kayak into the incoming tide. Given the warm weather, she’d opted against a wet suit and wore her Tevas without socks. Maine water was never warm, but she’d be fine. Her shirt and drawstring pants were of a quick-drying fabric, and she’d filled two dry packs with all the essentials. One held her picnic lunch. The other held everything she might need if she got stranded for any reason: waterproof matches, rope, emergency thermal blanket that folded up into a tiny square, rations she’d eat only in an emergency, aluminum foil, portable first-aid kit, flashlight, compass, charts, whistle, marine band radio, extra water and her jackknife. And duct tape. She’d zipped an extra compass, matches and a water bottle into her life vest, in case she got separated from her kayak.

All in all, she deemed herself ready for anything, even a recuperating John Straker.

She laid her paddle across her kayak and walked into the ankle-deep water, which wasn’t as cold as she’d expected. Maybe sixty-five degrees. Downright balmy for this stretch of Maine. She dropped into her seat, did her mental checklist and set off into deeper water, her strokes even and sure, all uneasiness gone. This was what she needed. A solo kayak trip in the clean, brisk Maine air, along the familiar rockbound coast with its evergreens, birches, wild blueberry bushes and summer cottages. The water was smooth, glasslike, the air so still she could hear the dipping of her paddle, the cry of gulls, the putter of distant lobster boats.

Yes, she thought. Emile was right. She needed to get back out on the water.

Two hours later, she was tired, hungry and exhilarated. A fog bank had formed on the eastern horizon, but she thought she’d be finished with her picnic and safely back at Emile’s before it arrived. The swells and the wind had picked up on the ocean side of Labreque Island, but she worked with them, not against them, as she paddled parallel to shore, looking for a landing spot. The island was a mere five acres of sand, rock, pine, spruce and a few intrepid beeches and birches, all of which took a pounding from the North Atlantic winds, surf and storms. The ocean side had imposing rock ledges, and the water tended to be choppier—but Emile’s ancient cottage, and thus John Straker, was on the bay side.

The waves pushed her toward shore. Despite the island’s rugged appearance, its ecosystem was fragile, Riley knew. She wanted to find a spot that would provide a smooth landing for her and an unintrusive one for the island. Just an inch of lost soil could take hundreds of years to replace. A sandy beach was her first choice; next best was a sloping rock ledge.

She found a spot that would do. It wasn’t great—little more than an indentation amid the steep rock cliffs and ledges and deep water swirling around huge granite boulders. The swells had picked up. If she capsized and bonked her head on a rock, she’d be seal food. This, she thought, was why one didn’t kayak alone. She concentrated, maintaining her center of gravity. A tilt to the left or the right could turn her over, even in a stable ocean kayak. She maneuvered her vessel perpendicular to the shore and, with strong strokes, propelled it straight toward the rocks.

Rocks scraped the bottom of her kayak, and she jumped out, yelping at the sting of the much colder water. Moving fast, she dragged the craft up onto the rocks, not stopping until she was well above the tide line. She sat on a rounded boulder, warmed by the midday sun, to catch her breath. Despite the worrisome fog bank hovering on the horizon, the view was stunning, well worth the small risk of running into Special Agent Straker.

It was hard to think of him as an FBI agent. The John Straker she’d known had been intent on becoming a lobsterman or a jailbird. She’d never believed he’d leave Washington County. His parents still lived in the same house where his mother had grown up, a ramshackle place in the village. His father was a lobsterman. His grandfather had worked in the local sardine canneries.

At the thought of him lurking just a few acres through rock, trees and brush she began to set up her picnic: an early Mac, wild-blueberry muffins, cheddar cheese, two brownies and sparkling cider. Using her jackknife, she carved the apple into wedges and the cheese into thin slices, then layered the two.

Perfection, she thought, tasting the cheese and apple, smelling the sea and the pine needles and the barest hint of fall in the air. Seagulls cried in the distance, and trees and brush rustled in the breeze. Everything else fell away: the stress and trauma of the past year; the questions about herself, her family, her work, what she wanted, what she believed; the break-neck pace of her life in Boston. She was here, alone on an isolated island she’d first visited as a baby.

She was on her first brownie when she realized the fog bank had moved. She jumped to her feet. “No! I need more time!”

But the fog had begun its inexorable sweep inland, eating up ocean with its impenetrable depths of gray and white. Riley knew she couldn’t get back to Emile’s before it reached the bay. She paced on the rocks, cursing her own arrogance as she felt the temperature drop and the dampness seep into her bones. The mist and swirling fog quickly blanketed the water, then the rocks, then the island itself. Her world shrank, and she swore again, because she should have known better and skipped her island picnic.

“No use swearing,” a voice said behind her. “Fog’ll do what it’ll do.”

Riley swallowed a curse and came to an abrupt halt on her boulder. Straker. He materialized out of milky fog and white pines, exactly as she remembered him. Two bullets and his years as a special agent of the Federal Bureau of Investigation hadn’t changed him. He was still thickly built, tawny-haired, gray-eyed and annoying.

“You’re the oceanographer,” he said. “You should have known the fog’d get here before you could sneak off.”

“I’m not clairvoyant.”

“I knew.”

Of course he’d know. He was the Maine native who knew everything. As if timing a fog bank were part of his genetic makeup. “Have you been spying on me?”

His eyes, as gray as the fog, settled on her. He didn’t answer. His heavyweight charcoal sweater emphasized the strength and breadth of his powerful shoulders. He didn’t look as if he’d been shot twice. He didn’t, Riley thought, look as if he’d done anything with his life except fish the coast of downeast Maine. He looked strong, fit, at ease with his island environment—and not happy about having her in it. But wisely or unwisely, she’d never been afraid of John Straker.

“Well, Straker, if possible you’re even worse than I remember.”

“Fog could be here for hours. Days. It’s going to get cold.”

It was already cold. “I tried not to disturb you.”

“I spotted you through my binoculars. You’re hard to miss. You looked like you were paddling a pink detergent bottle.”

“It’s a bright color so boats will see it. Forest green and dark blue wouldn’t stand out against the background of water and trees.”

He narrowed his eyes, the only change in his expression. “No kidding.”

He was making fun of her. No matter how much time she’d spent in Maine, how many degrees she had or what her experience—no matter how long he himself had stayed away—he was the local and she was the outsider. It was an old argument. He still had the scar on his right temple from one installment he’d lost.

“I thought Emile would warn you off. I’m not much company these days.”

“Emile did warn me, and you’ve never been much company, Straker. Where were you shot?”

“Up near the Canadian border.”

The man did try one’s nerves. He always had, from as far back as she could remember. When she was six and he ten, he’d enjoyed jerking her chain. He jerked everyone’s chain.

“Obviously your smart mouth’s still intact,” she stated.

“Everything’s intact that’s supposed to be intact.” He squinted out at the fog and mist; there was no wind now, no birds crying near or far. “You could be here until morning. Have fun.”

Naturally, he had no intention of inviting her back to the cottage to wait out the fog—and Riley would freeze to death before she asked. “I love the fog,” she told him.

He vanished into the trees.

She thrust her hands onto her hips and yelled, “And don’t you dare spy on me!”

He was gone. He wasn’t coming back. He’d let her sit out here and freeze. When she’d been eleven and gotten into trouble in high winds after taking one of Emile’s kayaks into the bay without permission, Straker had plucked her from the water in his father’s lobster boat. He’d been unmerciful in telling her what an idiot she was and had promised that next time he’d let her drown.

And she’d cried. It had been awful. She’d been cold, wet and scared, and there was fifteen-year-old John Straker threatening to pitch her overboard if she didn’t stop crying. “You made your bed,” he’d told her. “Lie in it.”

“Bastard,” she muttered now. She’d never intimidated John Straker. That was for sure.

She scooted off her boulder and unstrapped her dry pack. Damn. She was supposed to be back in Boston tonight, at work in the morning. She’d come to Maine last Wednesday for a round of fund-raising dinners, meetings and informal lectures at the Granger summer home on Mount Desert Island. Caroline Granger, Bennett’s second wife and now his widow, had decided to end her year of mourning and invited the directors and staff of the Boston Center for Oceanographic Studies north, perhaps to indicate she was ready to take her husband’s place as the center’s benefactor.

No one had mentioned Emile Labreque, living in exile a stone’s throw to the north. Riley hadn’t even told her father, Richard St. Joe, a whale biologist with the center, that she was extending her stay a few days to visit her grandfather.

With a groan of frustration, she dug out her emergency thermal blanket. It looked and felt like pliable aluminum foil. She unfolded it section by section, telling herself it’d be worse if she’d been unprepared. There was no shame in having to use her emergency supplies.

Still, she felt self-conscious and humiliated. She blamed Straker. He enjoyed seeing her in this predicament.

She climbed up onto a different boulder and threw the blanket over her shoulders. It was effective, but un-romantic. A fire was a last resort. Fires on islands could be deadly, and even a small campfire could scar a rock forever. She’d have to find a sandy spot.

She clutched her crinkly blanket around her, her windbreaker already limp and cold from the dampness, and followed a narrow path along the top of the rock ledge. It was just past high tide, and below her only the water’s edge was visible through the shroud of fog. Her path veered down among the rocks. She took it, relieved to have a safe outlet for her restless energy.

Fog was normal, she reminded herself. It wasn’t like an engine explosion and a raging fire aboard a ship. This wasn’t the Encounter. This was a great morning on the water with an aggravating ending—but not a traumatic one, not a dangerous one.

The path came to an end at the base of a huge, rounded boulder that Riley remembered from hikes on the island in years past. In happier days, she thought. Her parents, her sister, and later Matthew Granger would pack a couple of coolers and head out to Labreque Island for the day. Emile and Bennett had seldom joined them. There was always work, always the center. Now Bennett was dead, Emile was living in exile, his daughter wasn’t speaking to him and his granddaughter’s marriage to Matthew Granger was in turmoil.

Her sister’s husband had made a brief appearance on Mount Desert Island, long enough to demonstrate he hadn’t put the tragedy of the Encounter and his father’s death behind him. Matt shared Sam Cassain’s belief that Emile should be in jail on charges of negligent homicide.

Riley shoved back the unwelcome rush of images and plunged ahead, leaping from rock to rock, heedless of the fog, her flapping blanket, the memories she was trying to escape.

She walked to the edge of a flat, barnacle-covered boulder below the tide line. At its base, water swirled in cracks and crevices with the receding tide, exposing more barnacle-covered rocks, shallow tide pools, slippery seaweed. Her Tevas provided a firm grip on the rocks, although her toes were red and cold.

Should have packed socks, she thought. Straker had probably noticed her bare feet and smugly predicted frozen toes. She pictured him sitting by the cottage woodstove, warm as toast as he waited for the fog to lift and his unwelcome visitor to be on her way.

She leaped over a yard-wide, five-foot-deep crevice and climbed up a huge expanse of rock, all the way out to its edge. At high tide, the smaller rocks, sand and tide pools that surrounded its base now would be covered with water, creating a mini-island. She stood twenty feet above the receding tide. Ahead there was nothing but fog. It was like standing on the edge of the world.

Straker could have given her five damned minutes to warm her toes by the woodstove and have a cup of hot coffee. He could have lent her socks.

“Never mind Straker,” she muttered into the wall of fog.

Something caught her eye, drawing her gaze to the left. She peered down at water, rocks, seaweed and barnacles. Probably it was nothing. Fog could be deceiving.

Not this time.

Riley felt her blanket drop, heard herself gasp. Oh God.

Amid the rocks, seaweed and barnacles, facedown and motionless in the shallow water, was a man’s body.

Straker heard Riley yelling bloody murder and figured he had no choice. He had to see what was up. He walked out onto his rickety porch, where a pale, white sun was trying to burn through the fog. With any luck, the stranded Miss St. Joe could be on her way in less than an hour. She had always been…inconvenient.

He heard her thrashing through the brush alongside the cottage, heedless of the maze of paths that connected all points of the small island.

“Straker—Straker, my God, there’s a dead body on the rocks!”

He made a face. A dead body. Uh-huh.

He went back inside. His two rooms were toasty warm. He had a nice beef stew bubbling on the stove. The fog, the cold, the shifting winds were all reminders that summer was coming to an end. He couldn’t stay out here through the winter. A decision had to be made. What next in his life?

“Straker!”

Riley didn’t like sharing her island with him. She wasn’t above conjuring up a dead body just to get back at him for leaving her out in the cold fog. He’d known her since she was a precocious six-year-old who liked to recite the Latin names of every plant and creature she pulled out of a tide pool.

She pounded up the stairs onto the porch. She didn’t bother knocking, just threw open the door. “Didn’t you hear me?”

He stirred his stew. The steam, the rich smells were a welcome contrast to the cold, wet presence of Riley St. Joe. She was small and wiry like Emile, with his shock of short dark hair, his dark eyes, his drive and intensity. She had her mother’s quirky laugh, her father’s straight nose. She was difficult, competitive and a know-it-all. And she seemed to have no idea how much he’d changed since he’d left Schoodic Peninsula.

It was a great stew. Big chunks of carrots and red potatoes, celery, onions, sweet potatoes, a splash of burgundy. Not much meat. Since getting shot, he’d tried to be careful with his diet. His FBI shrink had urged him not to isolate himself, but his FBI shrink hadn’t grown up on the coast of Maine. Two hours out of the hospital, John had headed home. When Emile caught him camped out on Labreque Island, he’d offered him use of the cottage. There was no telephone, no mail, not much of a dock and the only power source an old kerosene generator and wood. Straker had accepted.

As a consequence, Emile’s younger granddaughter was in his doorway. He glanced at her from his position at the stove. She was pale, shaking, eyes wide.

“I heard you,” he said.

“Bastard—why didn’t you come? You know more about…oh, damn.”

She turned even paler. Straker put down his slotted spoon. Hell. Maybe she had seen a dead body. “Finish your sentence. This is good. I want to hear what it is you think I know more about than you do.”

“Dead bodies.”

It was almost a mumble. He said, “The fog can fool you.”

“Damn it, Straker, you don’t need to tell me about fog. I saw his—his—his hair and his hand—” Her eyes rolled back in her head. “I think I’m going to throw up.”

He sighed. Damned if he needed that. “Bathroom’s in there.”

“I know where the damned—”

She interrupted herself with a curse and lurched across the linoleum floor to the short hall that led straight to the bathroom. It was in an ell tacked onto the cottage. In the old days, there’d just been an outhouse. Straker had locked her into it once when she was eight or nine and especially on his nerves. Emile hadn’t been too pleased with him. Riley, the little snot, had screamed and carried on far more than was necessary. Straker had it in the back of his mind that was what she was doing now. Exaggerating, going for the drama.

He followed her, although not with great speed or enthusiasm. Still, if she choked on her tongue or something it was a long trek to an emergency room.

Between moaning and swearing at him, she got rid of the contents of her stomach. She managed fine. Straker, leaning in the doorway, found himself noticing the shape of her behind as she bent over the tank. He grimaced. He’d been out on his deserted island longer than he’d thought.

Leaving that realization for later pondering, he went out to the kitchen and checked the kettle he kept on the woodstove. The water was bubbling. He got down a restaurant-style mug Emile had probably lifted from a local diner a million years ago, dangled a tea bag in it and poured in the hot water.

Riley staggered back into the main room. She was trembling visibly and had a wet washcloth pressed to her forehead. Her color had improved, if only from the blood rushing to her head from pitching her cookies.

“It was the brownie,” she said, dropping onto an ancient wooden folding chair at the table.

Straker shoved the mug in front of her. The table was in front of a big picture window overlooking the bay, still enveloped in fog. “I thought it was the dead body.”

“I wouldn’t have thrown up if I hadn’t eaten the brownie.”

But she didn’t smile. There was no spark in her dark, almond-shaped eyes.

“I don’t have a phone,” he said. “We can use the radio on my boat to notify the police. I’ll go have a look, make sure you weren’t seeing things.”

“I’ll go with you.” She tried a sip of the tea, the tea bag still dangling. “I don’t want to stay here alone.”

“If the guy’s dead, he’s not going to come crawling in here.”

That rallied her. She pushed her chair back so forcefully it almost tipped over. She was still trembling, but she squared her shoulders. “Just let’s go.”

She took a couple more quick sips of tea, wiped at her face once more with the wet washcloth and pushed past him to the door. She looked a little wobbly, but Straker kept his mouth shut. Riley wasn’t one to like having her weaknesses pointed out to her. He wondered if this was her first dead human. Her job put her in contact with stranded whales and dolphins.

Then he remembered last year’s tragedy. Five dead, a narrow escape with her own life. She hadn’t retreated to a deserted island to lick her wounds. Physically unharmed, she’d returned to her work at the Boston Center for Oceanographic Studies. Straker doubted she’d acknowledge any mental scars from her ordeal.

He followed her along a wet, winding path. She pushed hard, although her head had to be pounding and her energy drained from being sick. The fog continued to hang in, thick, damp and cold, reducing visibility to just a few feet despite the sun’s attempts to burn through.

Straker felt the familiar tightness in his chest and incipient sense of panic that had nothing to do with following Riley St. Joe to a corpse. Fog had come to make him feel claustrophobic, as if his soul had spilled out of him and claimed the rest of the world.

Maybe he should have picked a cabin in the Arizona desert.

“There.” Riley stood on a rock ledge and pointed toward the water, which Straker could smell but not see. But he knew this stretch of coastline, knew the rocks, the tide pools, the currents. She turned to him. Her skin, hair, eyes had all taken on the milky grayness of the fog. “He’s caught on the rocks. The tide must have brought him in. He might go out again with high tide, but I don’t think so. I can show you—”

“I’ll find him.”

Straker charged down the rocks. He’d grown up on this coast, was comfortable jumping from rock to rock in any weather. And his physical wounds were long healed. He was in better shape now than he’d been in the past two or three years. But he wasn’t ready to go back to work. He trusted his instincts, his training, his experience. It wasn’t that. He just didn’t have much use for people. In the past six months, he’d grown accustomed to life alone.

Now a body had washed onto his deserted island. Maybe it was an omen. If he didn’t go back to work, work would come to him.

Of course, Riley had said nothing about murder. It was probably some poor bastard who’d taken a header off his boat.

The tide had moved out, and he made his way over barnacles and slick seaweed. He came to the water, just a few inches deep now. A giant hunk of granite loomed to his right. Riley would have been up there, he reasoned, looking down at the water.

Gravelly sand shifted under him. He stepped up onto a flat brown boulder, still wet from the receding tide. Not far ahead, waves slapped gently against rocks and sand.

He sensed the body before he saw it. His muscles tensed as he called upon the discipline and professionalism his work had instilled in him. He’d seen dead bodies before. He knew what to do.

This one was still, bloated, soaked. He’d put on jeans and a red polo shirt for his final day. He was about five feet off, facedown, as if he’d tripped and fallen running in from the water.

The gulls had been at him.

Straker turned away.

Riley materialized a few yards behind him. “You found him?”

“Go to my boat. Radio the police. I’ll wait here.”

“Why? If he’s dead—”

He looked at her. She was ghostlike, smaller than he remembered. “I’ll fight off the gulls.”

Two

L ou Dorrman tied up his boat and tossed Riley’s pink kayak onto Emile’s dock. She thanked him, hoping he’d make short work of dropping her off, then head back to the island. But he climbed out onto the dock after her. He was the local sheriff, a paunchy, gray-haired, no-nonsense cop who’d said for years that John Straker would come to a bad end. Someone was bound to shoot him, run him over or beat him senseless. That a body had turned up on the island where he was recuperating was no surprise to Lou Dorrman.

That Riley was there, too, obviously troubled him. He glowered at her. “What’re you doing hanging around John Straker?”

Her teeth chattered. The fog had burned off, leaving behind a warm, sunny afternoon, but she couldn’t stop shivering. It was nerves and dehydration—and the lingering, horrible image of the man she’d found on the rocks. Straker had made her put on an overshirt after the police had arrived. She’d had to roll up the sleeves about six times to get them to her wrists. The heavyweight chamois smelled of sawdust and salt water.

“I was having a picnic,” she said.

Dorrman nodded without understanding. “Hell of a picnic.”

“Do you have any clues about the body—who it was—”

“Not yet. There was no identification on him. The medical examiner will do an autopsy. We should know more soon.”

Riley thought she saw something in his eyes. “What is it, Sheriff?”

“Nothing. We have to do this one step at a time.” He shifted, eyeing her with a measure of sympathy. “You going to be okay? I imagine Emile’s out and about somewhere. I’ll have to round him up before too long, seeing how that’s his island.”

Last summer, it was Bennett Granger and four members of the Encounter crew. This summer…a dead body on Labreque Island. Riley pushed back the nightmare, the familiar sense of unease. “I’ll be fine on my own, thanks.” She still couldn’t stop shivering. “Sheriff, you don’t think Straker had anything to do with this, do you? I know he was shot six months ago—Emile said it had to do with domestic terrorism.”

“Domestic terrorism. Hell, that’s FBI talk. Let’s just take this one step at a time, okay? You’ll be around awhile?”

“I’m supposed to head back to Boston tonight. I have to be at work tomorrow. I was planning to visit my mother and sister in Camden on the way. I gave your deputy numbers where you can reach me.”

“All right. Go ahead. I’ll let you know if CID has any other ideas.” CID was the Criminal Investigation Division of the Maine State Police; Straker had already explained they’d handle the investigation. Dorrman cuffed her on the shoulder. “Rough day, kid. Put it behind you.”

While he sped back across the bay, Riley half carried, half dragged her kayak up to Emile’s cottage, its dark-stained wood blending into the surrounding spruce-fir forest. This was his home now, not just his periodic getaway. It hadn’t changed in years. She welcomed the familiarity of the smells and sounds, even the exposed pine roots in the path as she returned the kayak to the attached shed.

Her legs almost gave out on her, as if she were climbing Mount Katahdin instead of a few porch steps. She collapsed onto an old Adirondack chair. The wind had shifted. There wasn’t even a hint of fog in the clear September air. It was cool up on the porch, out of the sun, which only made her shivering worse.

Emile’s door was shut tight. She doubted he’d have heard the news yet. She felt acid crawl up her throat at the unbidden images of bloated flesh, pesky gulls swooping down on the hapless body.

She sprang up out of the chair. “I should have skipped that stupid picnic.”

Then Straker could have found the body on his own. Or the sea could have had it back. She struggled with the same disconcerting feeling of helplessness she’d experienced at her first whale and dolphin strandings when she was a teenager volunteering on a rescue and recovery team. Their mission was to end the suffering of animals beyond help, get the healthy ones out to sea before they died on the beaches and treat the injured, taking them back to the center for rehabilitation and, whenever possible, their eventual return to the wild. Now it was her team—but she would never get used to the death and suffering.

The man on the beach had been long past suffering.

She decided to leave Emile a note. Sympathy, commiseration, allaying her fears, venting—such niceties wouldn’t occur to him. He would expect her to continue on to Camden and Boston. He wasn’t heartless; he was simply oblivious. The urge to share her woes with him arose more from the shock of the moment than any rational reasoning on her part. She’d arrived too late to do the man on the rocks any good, and now her experience felt unfinished, as if she should do more, know more.

Would Straker dismiss the dead man and resume his isolated island life without a second thought?

She found Emile’s spare key on the windowsill and let herself in. Even less rational than wanting to cry on Emile’s shoulder was trying to get into John Straker’s mind. Time to get her things and be on her way.

But when she set off, she ended up on the side street above the village harbor, where Straker’s parents lived in a serviceable house that was at once home, shop and project. It had been in a constant state of flux for as long as Riley could remember, with gardens going in and coming out and discarded house innards piling up in the yard as various rooms underwent renovation. The glassed-in front porch served as a catchall for yard sale findings Straker’s mother planned to fix up. She was clever at fixing things up, even if she tended to underestimate the time she would require. Summer people and locals alike employed her talents in furniture restoration and upholstery—they just knew not to expect quick results.

John Straker, Sr., was a lobsterman, his pots piled up outside the garage. It was a hard, good life, and if he regretted not having his son around to share it, he would never let an outsider like Riley St. Joe know about it.

She went around back, and Linda Straker called her into her cluttered kitchen, where she was elbow deep in one of her craft projects. She had an unlit cigarette tucked between her lips. She was a strong, stubborn, imaginative woman with hair that frequently changed color—today it was brunette—and a few extra pounds on her hips.

Her son had inherited her gray eyes. They settled on Riley. “You’re here about that dead body?”

“You heard.”

“Not much happens around here I don’t hear about. Where’s Emile?”

“I don’t know. On the nature preserve, I expect. I’m on my way back to Boston.” Riley dropped into a chair; she felt awkward, as if she were twelve again and Mrs. Straker would offer her a glass of Kool-Aid. “Actually, I’m not sure why I stopped by.”

“Because you’re afraid that body’s got something to do with my son and it’s going to come back and bite you in the behind.” She took a breath, made a pretend drag on her cigarette. Her eyes were serious, experienced. “It could, you know.”

“Why do you say that?”

“Because that’s the way it’s been with John since he saw the light of day thirty-four years ago. He’s an FBI agent now, Riley. He’s seen and done things since you nailed him with that rock when you were twelve. If I were you, I wouldn’t mess with him.”

Riley fiddled with a length of twine. “Too late.”

“You couldn’t have just pretended you didn’t see that body and gone on your way?” She gave a long sigh. “No, I suppose not, and if you had, John would have known it and come after you. No way out of this one, Riley. If you’re going to go toe-to-toe with him again, don’t rely on luck. That’s my advice. Take good aim, and if you do hit him, run like hell.”

In spite of her tension, Riley managed a laugh. “I have no intention of seeing your son again, never mind throwing rocks or anything else at him.”

The back door banged open, and Straker glared in at the two women. If Riley had still had any doubts he wasn’t eighteen anymore, they would have been dispelled. He radiated hard-edged energy, the kind of raw intensity she’d expect from a man who’d gotten himself shot twice.

“Speak of the devil,” Linda Straker said, unperturbed.

He kicked the door shut behind him. “St. Joe—damn it, what the hell are you doing here?”

Riley groaned. “I’m talking to your mother. I’m allowed. Aren’t you supposed to be holed up on the island?”

“He comes into town every now and then for supplies,” his mother answered for him.

He turned to her. “I thought you quit smoking.”

“I did. It’s not lit.”

“Then what are these for?” He picked up a package of matches that Riley hadn’t even noticed and tucked them in his jeans pocket. “You’ll be puffing away the minute I leave.”

She dropped her cigarette into a brass ashtray shaped like a lobster. “There. Nazi. I deserve a cigarette after hearing you found a dead body.”

“I didn’t. Riley did.”

“You could have taught school like your sister,” his mother said, “or taken up lobstering like your father. You could have opened up a law practice in town. But no, you have to join the FBI and get shot, bring dead bodies to town.”

“That body has nothing to do with me.”

“Then it has something to do with Emile Labreque. Either way, you’ll get involved. You’ve always had a soft spot for Emile. He believed in you when no one else did. Even I had my doubts.”

“Mrs. Straker,” Riley said carefully, “just because the body was found on Labreque Island doesn’t mean Emile—”

Straker didn’t let her finish. He fingered a paper doily. “What’re you making?”

His mother bit off a sigh. “Your Christmas present. Keep your mitts off.”

“I stopped by to reassure you. I knew you’d hear what happened.” He shot Riley another nasty look, as if she’d been the one who squealed. “It’s nothing to worry about, probably just some poor bastard who fell off his boat.”

“No one’s been reported missing. You’d think—”

“Don’t think, Ma. Just let the police handle this one. And I’m fine, in case you were wondering.”

She glowered at him. “The hell you’re fine. You’ve been sitting out on that island for six months. Half the town thinks you’re a raving lunatic.”

His jaw set hard. “I’ve said my piece.”

He about-faced and walked out. Just like that. Linda Straker snatched up a huge pair of scissors. “That terrorist didn’t do half the job on him I could do right now.”

Riley judiciously said nothing.

“I’ll tell you the truth, Riley. We all breathed a sigh of relief when he went out to Labreque Island to recuperate instead of up into the spare bedroom. I’d just as soon tend a wounded tiger as him.”

Riley knew the minute she agreed with her, Linda Straker would turn on her. “Will you excuse me, Mrs. Straker?”

“Go on,” she said. “Go after him. You’re looking good, Riley—I meant to say that right off. I wasn’t sure what to expect after your grandfather’s ship went down.”

“That wasn’t his fault, you know.”

“You never know with ships,” she said, and Riley, suddenly feeling the walls closing in around her, shot outside.

She caught up with Straker in the driveway. “Where are you going?”

He whipped around. Every muscle in his body seemed tense, rigid, as if he was ready to burst out of his skin. “Back.”

“Back where?”

“The island.”

“I’ve got your shirt. It’s in my car.” She eyed him, becoming aware of a strange sense of uneasiness. His mother was right—he wasn’t the same kid she’d bloodied all those years ago. But she wasn’t intimidated. “You look as if you want to lock me in an outhouse.”

His eyes sparked, and his mouth drew into a sardonic smile. “That’s not it.”

Riley nearly choked. Bullet wounds, a six-month self-imposed exile. Women probably hadn’t been on his short list of things to do. Well, she’d walked into that one. “Are the police finished?”

“No.”

“Did you offer to help?”

“No.”

“You know, Straker, if I had a rock…” Riley didn’t go on. She’d pushed her luck enough with him. “What else are you doing in town, besides reassuring your mother?”

His eyes turned to slits. “Are you being sarcastic?”

“I’m not afraid of you, Straker.”

“That always was your problem.”

He turned and started down the narrow street. Riley sighed. “What about your shirt?” she called after him.

“Keep it.”

“Do you need a ride?”

“No.”

“How did you get here?”

He glanced back at her. “I live on an island. I took a boat.”

“I hate you, Straker,” she called. “I’ve always hated you.”

“Good.”

She got in her car and drove in the opposite direction. She was agitated and restless and faintly sick to her stomach, and she didn’t trust herself not to run Straker over. She headed out to the nature preserve, but Emile wasn’t around. Neither was his car or his boat. She stopped back at his cottage. Same thing.

She gripped the wheel. “Well. Push has come to shove.”

It was time to head to Camden and face her mother and sister. The first time she’d spent any time with her grandfather since the Encounter, and she’d found a dead body. No way would this go over well.

Two hours later, Riley rang the doorbell to her mother’s little, mid-nineteenth-century gray clapboard on a pretty street above Camden Harbor. When the black-painted front door opened, she surprised herself by bursting into tears.

“Emile,” Mara St. Joe said, tight-lipped. “Damn him.”

“It’s not him—he didn’t do anything.” Riley gulped in air, feeling like a ten-year-old. She brushed her cheeks with her fingertips. Thank God she hadn’t fallen apart in front of Straker. “I found a dead body.”

“I know. I heard on the radio. It’s Emile’s fault. He never should have let you kayak alone.”

She whisked Riley into the front parlor. This was her parents’ first house—her mother’s first house. Two years ago, Mara St. Joe had declared she’d had her fill of living aboard research vessels and in whatever rented apartment was nearest their work. She’d grown up like that, she’d raised two children like that and she’d had enough. She chucked her puffin and guillemot research and set off to picturesque, upscale Camden, with its windjammers and yachts and grand old houses built by legendary sea captains and shipbuilders. She became a successful freelance nature writer and bought a house. For a while, Riley wondered if her parents would call it quits, but if they’d ever considered it, they hadn’t told her. Her father was free to come and go as he pleased, which seemed to suit them both. Her parents had, and had always had, an unconventional marriage.

“Sit,” she said. “Catch your breath.”

“Mom, I’m fine. It was just pent-up tension.”

“It was just your grandfather.”

She half shoved Riley onto a wing chair. The parlor was decorated in antiques and antique reproductions in rich woods and soothing colors. Her mother, Riley thought, was not a patient woman. She was taller than Riley—taller even than Emile—with dark hair streaked white and eyes that could flare with sudden bursts of anger. People said her mother, Emile’s one and only wife, who’d died when Mara was two, had possessed a similar temper. At fifty-five, Mara knew all too well the particular kind of pain her father could inflict. It wasn’t his work that drove her crazy, she’d said—it was his single-mindedness. She didn’t care if it was in a good cause, it was workaholism by any other name, and it left her out. It left everyone out.

“Would you like a cup of tea?” she asked, obviously restraining herself.

Riley shook her head. “I’m okay now. I should have called and told you. I didn’t mean for you to hear the news on the radio.”

“I had it on while I was working. Oh, Riley.” She brushed back her hair with one hand and paced; she had on jeans and a plaid flannel tunic, her writing clothes. “Emile should have known better. And John Straker of all people…” She groaned in disbelief. “My God!”

“He let me throw up in his toilet.”

Her mother spun around at her. “He’s a lunatic! Living out on that island alone the past six months. What could Emile have been thinking when he let you go out there?”

“He didn’t let me. I just went. Mom, for heaven’s sake, I’m not twelve.”

“I still blame Emile.”

Riley sank into the chair, spent. She smiled wanly at her mother. Her reaction was exactly what she’d expected, perhaps even needed. “I’m so glad to see you, Mom. Is Sig home?”

“She’s out walking. She’ll be back any minute. Come, I’ll make tea. You’ll feel better in no time.” Mara exhaled. “Damn Emile.”

She was having twins.

Sig St. Joe slipped into the enclosed back porch of her mother’s house, which she’d fashioned into her first real studio in years. She had a worktable, 140-pound cold-pressed paper, tubes of watercolors, a dozen brushes, water jars, boards—everything she needed except inspiration.

She flopped onto a studio bed she’d covered in old quilts and pillows, just like her girlhood bed in the loft at Emile’s cottage. She’d spotted Riley’s car. She couldn’t face either her sister or her mother right now.

Twins.

She was just over four months pregnant and had told no one, including her goddamned, miserable, self-absorbed husband.

Sig sighed. That was another quarter for her mason jar. She was on a campaign to stop swearing. At the rate she was going, she’d be broke by the end of the week, or she’d have to dip into her Granger money. God forbid. She’d rather wash her mouth out with soap.

She could feel the babies move. Just a flutter. Probably they were already jockeying for position. She wasn’t prepared to have one baby, never mind two. But maybe in the long run it would be easier, because she had no intention of getting pregnant again. After Matthew Granger, she was through with men.

One day she’d have to explain to her babies what a flaming asshole their father was.

Flaming jerk, she amended, mentally putting another quarter in the jar.

He was rich, he was handsome and he was convinced her grandfather should be in jail for negligent homicide. “Emile’s criminally responsible for my father’s death. Admit it.” Sig didn’t want to admit anything. She wanted Matt to work through his anger and grief and accept that they just didn’t know what had happened aboard the Encounter. No one did. The boat was at the bottom of the North Atlantic. The official investigation was inconclusive.

No, she thought, don’t go there. Thinking about the Encounter and her father-in-law’s tragic death—the tragic deaths of the four crew members—spun her around in circles. There was nothing she could do. There was nothing Matt could do, only he couldn’t accept that, at least not yet and maybe not ever.

She just wanted to bury herself in a heap of quilts and stay out here all night, pretend she was ten again, sleeping out at Emile’s with her sister. She’d felt so safe at ten. Whatever her family’s oddities, she’d never felt anything but safe with them. Now here she was, thirty-four, pregnant, estranged from her rich husband, a failure as an artist and about to be a failure as a mother.

Sig glanced over at her worktable, where another of her abandoned paintings was still taped to her large board. The porch didn’t go with the rest of the house. It had been added in one of the various renovations over the past century or so, and her mother wanted to get rid of it. She wanted a dooryard garden. Well, it made a lousy studio. The light was bad, and there was no heat. Sig knew she couldn’t work out here much longer. It was time. She had to figure out her life.

What would she do with twins?

They’d be Granger twins. She shuddered. It wasn’t as bad as bearing the Prince of Wales, but it was damned close. Maybe she just wouldn’t tell Matt about his babies. Spare him the torture of explaining to the rest of Beacon Hill that not only had he married Emile Labreque’s granddaughter, he was now providing the murderous madman with great-grandchildren.

The door from the kitchen opened, and Riley said in an unusually small voice, “Sig? Mom thought she heard you.”

“I’m here wallowing in self-pity. Come on out. Mom send tea?”

“And raisin toast.”

“Good. I’m starving.” Eating for three. She eyed her younger sister, who looked so damned tiny and smart—and something else. “Jesus, what happened to you?”

“It’s a long story. I’m okay.”

Riley set a tray on an old gateleg table their mother had found at a yard sale and painted creamy white. Sig had messed it up with watercolor spills. Splatters of cobalt and lemon, dots of purple, one big splash of crimson. She loved spills.

“You don’t look okay,” Sig said.

Riley ignored her comment and sat on the other end of the studio bed. Sig was tall and leggy, like the St. Joes. When they were kids, Emile had called his granddaughters Big Dog and Little Dog until Mara told him to stop it, he’d give them a complex. Emile didn’t understand things like complexes.

Sig blinked back sudden tears. She hadn’t seen her grandfather in a year. Not since the Encounter. “You’ve been to see Emile, haven’t you?”

Riley poured tea and placed a triangle of toast on the side of each saucer. Mara had gotten out the good china. Definitely something was up. Sig shifted uncomfortably, her voluminous dress drawing across her swelling abdomen. She realized her mistake, but too late.

Riley gasped, nearly dropping the teapot. “Sig—you’re pregnant!”

Sig managed a wry smile. “The trained scientist speaks.”

“When—how—” Riley blushed furiously, bringing much needed color to her cheeks; for a woman consumed with the doings of sea beasts of all kinds, Sig was amazed at how downright prudish her sister could be. “I mean, how far along are you?”

“A little over four months. I can feel them move.”

“Them?”

“I found out on Friday I’m having twins. I’ve been trying to absorb it ever since.” Saying it out loud didn’t make her feel any more in control of her situation. “I haven’t told a soul.”

“Mom—”

“She doesn’t even know I’m pregnant, never mind having twins. Neither does Matt. I haven’t seen him in…well, ages.”

Riley handed her tea and toast. “Looks as if you saw him within the last five months or so. He’s on Mount Desert Island. I ran into him. He made a brief appearance at one of Caroline’s dinners. He managed not to mention his vendetta against Emile.” Riley picked up her tea again. “He was staying on his boat. I would think he’s still there.”

“It doesn’t matter. He’s so eaten up with anger and grief over what happened to his father….” Sig waved a hand, dismissing Matthew, all the upheavals of the past year. “I just don’t care anymore.”

The color had drained back out of Riley’s face. Sig silently chastised herself. There was no point in bringing up past horrors when obviously some new one had her sister in its grip. Bennett Granger was dead. He was one of the finest men Sig had ever known, and he and Emile had been friends and partners for fifty years. That his death had led to more tragedy and pain only compounded her sorrow.

“Where’s Mom?” she asked.

“She’s slipped off to the market. She insisted I stay for dinner. She’s cooking lobster.” But Riley didn’t seize the opportunity to proceed with her own problems. “She knows, Sig. You know she does. She’s just waiting for you to say something. You can talk to her—”

“She never wanted me to marry a Granger.”

“That’s because she was afraid you’d end up living in his shadow and indulging his whims. When she realized Matt’s a regular guy, she came around.”

“He’s not a regular guy. He’s a goddamned blueblood with too much money and not enough common sense.”

“You sound as if you hate him.”

“I wish I did. My life would be so much easier.” Sig quickly sipped her tea and bit into the raisin toast; her mother had slathered on the butter. “I said ‘goddamn,’ didn’t I? That’s another quarter for the mason jar.”

“You’ve quit swearing again?”

“I was doing pretty well until I found out I’m having twins.” She inhaled, unable to concentrate on anyone’s problems but her own. “I want these babies, Riley. I want to be a good mother.”

“You will be. You just won’t be conventional. You haven’t started smoking again, have you?”

“Not a chance. And how’re your vices?”

Her sister grinned, and some of the usual spark came back into her dark eyes. “I have no vices.”

“Ha. You’re like Emile and Dad. The seven seas are your vice.”

“My passion,” Riley amended.

“Same difference. Now, are you going to tell me why you look like absolute shit?” When Riley didn’t answer, Sig winced. “I’ve really fallen off the wagon this time. I’ve been swearing like a sailor.”

But Riley had shut her eyes, and she squeezed back tears.

“Riley…”

“I found a dead body and almost threw up on John Straker.”

“Holy shit,” Sig said. “No wonder Mom’s making you lobster.”

Three

S traker didn’t settle quickly back into his routines. He heated his stew and took a steaming bowl of it onto his porch. It was early for lunch, but he didn’t care. The police had packed up late yesterday and left, at least for now. The island was quiet again, the waves, wind, gulls and familiar putter of lobster boats the only sounds. The return to solitude didn’t have the impact he’d expected. A few days ago, the quiet had soothed his soul. Now, twenty-four hours after Riley St. Joe and a dead body had violated his tranquility, it was getting on his nerves.

He spotted Lou Dorrman’s boat making its way across the bay toward the island and went down to the rickety dock. The sheriff tied up, jumped out and greeted him with a curt nod. It was as if Straker’s old life had reached into his new life to remind him there was no escape. “What’s up, Sheriff?”

“We just got word from the medical examiner. He won’t have final results for a while, but his preliminary exam suggests our John Doe took a blow to the head.”

Straker went still. “Accident?”

“CID’s treating it as a suspicious death. We need to know what role the head injury played in his death, did he take the hit before he was in the water, after—maybe when he washed in on the rocks.”

“I don’t know how he could have washed ashore, with the tide and the currents out here. Doesn’t make sense.”

Dorrman frowned. He’d gone to school with Straker’s father, had once dated Straker’s mother. “You have any visitors out here the past few days? Besides Riley.”

“Christ, Lou, if I offed someone, I wouldn’t dump his body on the rocks for Riley St. Joe to find.”

“Answer the question.”

“No. No visitors. And if our John Doe had spent any time on the island, I’d have known about it.”

“He wouldn’t have anything to do with one of your FBI cases?”

“If he did,” Straker said pointedly, “I wouldn’t be sitting on my porch eating a bowl of stew.”

Dorrman didn’t back down. “I wish you’d picked somewhere else to sit around for six months. You’re a burr on my butt, Straker. See to it we can find you if we have more questions.”

Straker eyed him, took in the red face, the unusual level of aggravation, even for Lou Dorrman. “What else?”

“What do you mean, what else?”

“Something else is eating at you.”

The sheriff huffed and gazed out at the water a moment. “I can’t find Emile.”

“Hell.”

“I checked his cottage, I checked the preserve. His boat’s gone, his car’s gone.” Dorrman shifted his back to Straker. “I don’t like it. A dead body turns up on Labreque Island one day, Emile disappears the next.”

“Did you check inside his cottage?”

“I can’t do that without a warrant.”

Straker could. “Give me a lift?”

Twenty minutes later, they put in at Emile’s dock. Straker didn’t wait for Dorrman. He headed up to the old man’s cottage, mounted the steps and tried the door. Locked. He held the doorknob, leaned his shoulder against the door and, putting his weight into it, pushed hard.

The door came on the second push. Piece of cake.

“Christ,” Dorrman said from the bottom of the stairs, “I don’t believe you.”

“I’m his friend. This is what he’d expect. I’ll be out in two minutes.”

Emile’s cottage was more cheap old man than world-famous oceanographer. He’d left most of his old life behind. The only remnants were copies of his books and documentaries on a shelf in the main room and a few pictures of his family aboard the Encounter. He’d taken out the trash, left a mug in the dish drainer, unplugged the coffeepot. Straker checked the downstairs bedroom. A tidy sailor to the last, Emile had made his bed, too.

Straker took the steep, ladderlike stairs up to the loft and came across a red bra, size 34B, under a creaky twin bed. It provided no clues as to Emile and his whereabouts. It did, however, provide fresh insight into Riley. She’d never been neat, but Straker wouldn’t have expected her to favor red underwear.

Best to keep his mind on the task at hand.

He joined Dorrman back outside. “He cleared out.”

“Kind of makes you wonder, doesn’t it?”

“Not my job to wonder. I’m going to take a drive down to Boston.” A sudden wind gusted off the bay; he was thinking up his plan as he went along, knowing already he’d regret it. He should go back to Labreque Island and reheat his stew. “I’ll let you know if I run into him.”

“You do that. Keep in touch.”

“You want to bug my car, make sure I don’t take off to Alaska?”

Dorrman sucked in a breath, controlling his irritation. “If it were up to me, Straker, you’d be hauling in lobsters with your old man. You’re not fit to be an officer of the law. Never have been.”

“Does that mean if I’d been killed instead of wounded six months ago you wouldn’t have marched in my funeral parade?”

Dorrman’s mouth stretched into a thin, mean grin. “There’d have been a fucking brawl over who got to lead that parade.”

Straker took no offense. Louis Dorrman didn’t like him. A lot of people didn’t like him. But Straker had friends, and he had people he trusted—and he did his job. He’d never been the most popular guy around. It didn’t worry him. What worried him were the dead body Riley St. Joe had found on his island and where Emile had taken himself off to.

The sheriff grudgingly gave him a ride back to the island and waited while Straker packed up, grabbed his car keys and rinsed out his stew bowl. He didn’t need to come back to find the place overrun with ants.

He climbed back into Dorrman’s boat. “My car’s at my folks’ place.”

“I know,” the sheriff said, as if to remind Straker he knew everything that went on in his town. He was the one who’d stayed, who hadn’t gone off and joined the FBI. Dorrman gunned the engine and sped across the bay.

Riley picked up eggplant parmesan from her favorite Porter Square deli on her way home from work, where, mercifully, no one had heard about what had happened yesterday on Schoodic Peninsula. She kept the news to herself. When she’d left Mount Desert Island, she’d said only that she was taking a long weekend. She hadn’t mentioned going to visit Emile.

With any luck, there’d be a message from the police on her answering machine telling her the man she’d found had been identified, he’d died in a tragic accident, end of story.

She had a one-bedroom apartment on the third floor of a triple decker just off Porter Square in Cambridge. There was no message from the police on her machine. There was one from her mother, asking her if she was all right. Nothing from Richard St. Joe. Her father was in Bath, checking on the Encounter II, the state-of-the-art, ecologically friendly research vessel the center was having built. He would be back tomorrow.

She heated her eggplant parmesan in the microwave and whisked a bit of balsamic vinegar and olive oil together for her salad. It felt good to reacquaint herself with her routines. After dinner, she’d put in a load of laundry and clean out her fridge.

Her telephone rang, and she grabbed the portable out from under a newspaper on her kitchen table.

“What would you do if I told you I was on the curb outside your apartment?”

Straker. Her stomach knotted. “You have a sick sense of humor, Straker. You’re not on my curb. You live on a deserted island. You hate people. You wouldn’t traipse all the way to Boston just to aggravate me.”

“You wouldn’t invite me in?”

She tightened her grip on the phone. He sounded close. She remembered he didn’t have a phone on the island. She took her portable into the front room, knelt on her futon couch, leaned over and pulled back the blinds so she could peer down at the street.

It was dark, but she could make out a beat-up, rusting gray Subaru station wagon with Maine plates.

“Damn it, Straker, you are on my curb!”

“So, do I get to come in?”

She hit the off button and tossed her phone onto the couch. What did he think he was doing? Six months alone on an island—and now Boston? He’d kill someone. Someone would kill him. He was not fit for the civilized world.

It was the body. Something must have happened.

She was hyperventilating. She clamped her mouth shut and held her breath, forcing herself to count to five. If she didn’t let Straker in, what would he do?

If she did let him in, what would he do?

She unlocked her door and took the two flights of stairs two and even three steps at a time. She picked up so much momentum, she almost went head-overteakettle down the front stoop. After throwing up, all she needed was to split her head open at Straker’s feet.

He had his window rolled down.

Riley caught her breath. “I can’t believe you drove all the way down from Maine.”

He popped the last of a Big Mac into his mouth. “Now that you mention it, neither can I.”

“What do you want?”

He reached for a backpack on the floor in front of the passenger seat, rolled up his window, locked his door and climbed out. He looked just as powerful and strong and unflappable on her Porter Square sidewalk as on Labreque Island. The city didn’t make him any more or less than what he was—a man she would be wise to avoid. His own mother had said so.

“Our body came with a nasty blow to the head,” he said. “CID’s treating it as a suspicious death.”

“You mean—what—” Her stomach rolled over. “Are you suggesting he was murdered?”

“That’s my bet.”

He hoisted his backpack over one shoulder and started for her front stoop as if he’d just told her a dog had peed on her rug. Riley stayed on the sidewalk next to his car. She couldn’t move. Her knees wobbled. He wasn’t just John Straker, obnoxious teenager from her past. He was an FBI agent. He’d been shot twice by some dangerous nut on the FBI’s Most Wanted list. He’d spent the last six months as a recluse.

Straker turned back to her. He shook his head. “You aren’t going to throw up, are you?”

That unmoored her. She brushed past him and walked up the steps with as much nonchalance as she could fake. She prided herself on her ability to look reality square in the eye. Right now, the reality was that Straker was here, and she had to deal with him. She headed upstairs, assuming he would follow. He did.

“I figured you for a condo on the water,” he said from behind her.

“Too expensive.”

“Well, I guess you’re comfortable among Cambridge eggheads.”

She glanced back at him, cool. “Don’t inflict your stereotypes on me, Straker.”

He shrugged. “Tell me your apartment won’t have egghead written all over it.”

“Just shut up.”

She could feel his grin as she pushed open her door. He’d always known how to jerk her chain. He walked in past her, took in her living room with her stuff stacked and spread out everywhere and gave her a smug wink. “I rest my case.”

“I haven’t had a chance to clean—”

“You have enough books and magazines and crap in here to start your own think tank.” He walked over to her computer table, cluttered with printouts and Post-it Notes. The wall behind it was covered with nautical charts. He ran a finger over the flamingo Beanie Baby she kept on her monitor. “Egghead with a touch of kook.”

Riley gritted her teeth. “Straker, I swear I don’t know how people stand you.”

“They don’t.” He abandoned her computer and came closer to her. It was as if he’d brought an electric current into her apartment; the air sizzled. “You’re looking a little green at the gills. Want me to fetch you a drink?”

“No. I want you to tell me why you’re here.”

He lifted a stack of Audubon magazines off her futon couch, set them on the floor next to a stack of Smithsonian magazines and sat down. “Emile took off.”

“What do you mean, he took off?”

“I mean he took out the trash, made his bed, locked up and vamoosed. No car, no boat. He probably hid one—my bet’s on the car. Emile’s a sailor at heart. He’d go by water if he had a choice.”

Riley ignored a sudden chill and uneasiness. “You’re thinking like an FBI agent instead of someone who knows Emile. He does this sort of thing. He’ll go off for days at a time without telling anyone.”

“Does he always hide his car?”

“You don’t know he hid it. He could have just used it to haul supplies to his boat, then didn’t want to take the trouble of driving it back up to the cottage, so left it.”

Straker shook his head. “I don’t think so.” He leaned back and stretched out his thick legs. Riley didn’t remember him being so earthy. He seemed to exude sexuality. It had to be deliberate. A way of throwing her off balance in case she was hiding something from him. He glanced around. “No cat?”

“What?”

“I figured you’d have a cat.”

She groaned. “This is outrageous. I think you should leave.”

“I’d have to sleep in my car. I don’t have enough dough on me for a hotel.”

“Don’t you have a credit card?”

“Nope. I got rid of all my plastic after I got shot.”

He was perfectly calm, controlled and irritatingly at ease. Riley sputtered, “You can’t think…”

She fought the overwhelming sense she was losing her mind. The man she’d found may have been murdered, Emile had slipped off and John Straker, who’d been living on a deserted island for the past six months, was in her apartment. She hadn’t had a man in her apartment in months, not since after the Encounter, when the oceanographer she’d been casually dating said for her to take a few weeks to pull her head together, he’d be in touch. He hadn’t been in touch, and her life had gone on. She had her work. Romance would take care of itself.

She winced. It was dangerous to think about romance with John Straker standing inches from her. “You’re not spending the night,” she told him.

His gray eyes leveled on her. “Sure I am. Why else the backpack?”

Why else indeed. She should have connected the dots sooner, like out on the street. “Then what?”

He shrugged. “The morning will bring what the morning will bring.”

“To hell with you, Straker. You have a plan and you know it. What is it? Do you think Emile had something to do with that dead body? Do you think he’s going to contact me? Has already contacted me?” She thrust her hands onto her hips, in full outrage now. “Are you going to follow me around just in case I’m up to something nefarious?”

“Nefarious?” He grinned. “I’ve been in law enforcement for ten years, and I don’t think I’ve ever used that word.”

She all but sputtered again. “You listen to me. I do not need and will not tolerate a reclusive, lunatic FBI agent with post-traumatic stress disorder in my hip pocket.”

He got to his feet, crumpled up his Big Mac wrapper and walked through the dining room into the kitchen. Riley followed him. She wondered if she’d said something wrong. If she’d said a lot wrong. She reminded herself that everything she’d said was true and thus it might have been wiser on her part not to say it out loud. What if he snapped?

He glanced back at her. “Trash can?”

“Under the sink.”

He pulled open the cupboard and tossed in the crumpled wrapper. He turned back to her. His eyes were narrowed; his body was rigid. She wasn’t nervous, but she was on high alert. He said, “Two things.”

“Okay.”

“One, I don’t have PTSD. I’d have PTSD if the guy’d shot his hostages. He didn’t. He shot me. So, no PTSD.”

She nodded. “No PTSD.”

“Two, you need a drink.”

“I don’t need a drink. I don’t need anything—”

He sighed. “Now I remember why we threw rocks at each other when we were kids. Do you have whiskey or is wine it?”

“Wine’s it.”