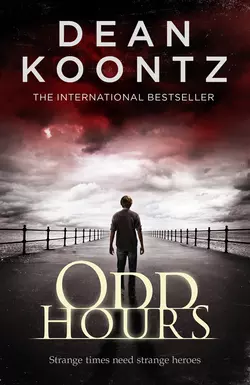

Odd Hours

Dean Koontz

From the mind of Dean Koontz, the 400 million copy worldwide bestseller, comes this supernatural tale of good and evil, and life and death. Find out why Odd Thomas is the master storyteller’s most talked about creation.Strange times need strange heroes.Odd Thomas lives always between two worlds. He can see the lingering dead and knows that even in chaos, there is order, purpose, and strange meaning that invites our understanding but often thwarts it.Intuition has brought Odd Thomas to the quaint town of Magic Beach on the California coast. As he waits to learn why he has been drawn there, he finds work as a cook and assistant to a once-famous film actor who, at eighty has become an eccentric with as long a list of fears as he has stories about Hollywood’s golden days.Odd is having dreams of a red tide, vague but worrisome. By day he senses a free-floating fear in the air of the town, as if unleashed by the crashing waves. But nothing prepares him for the hard truth of what he will discover as he comes face to face with a form of evil that will test him as never before…

Copyright (#ulink_fd458b01-4f48-5868-aa7d-b9dec8a76118)

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2008

Copyright © Dean Koontz 2008

Dean Koontz asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007267552

Ebook Edition © 2013 ISBN: 9780007287314

Version: 2017-10-16

This fourth Odd adventure is dedicated to Bruce, Carolyn, and Michael Rouleau.

To Michael because he makes his parents proud.

To Carolyn because she makes Bruce happy.

To Bruce because he has been so reliable all these years, and because he truly knows what it means to love a good dog.

I feel my fate in what I cannot fear.

I learn by going where I have to go.

—Theodore Roethke, “The Waking”

Table of Contents

Title Page (#u3e90792a-d8ac-51c0-acce-dd34ef8ca0d6)

Copyright (#u9a17524e-f6a6-5519-9d3b-b2117170e409)

Dedication (#u12450d96-93f7-5be3-9bab-1880fc6512bd)

Epigraph (#u79b1ab40-3785-5c03-8bd3-ac4a4b1f0ae5)

Chapter 1 (#u2843aea8-ff58-58fb-bbfe-6d43aab4c6d4)

Chapter 2 (#ue6bc56f0-56c8-5676-814d-f5fe18329845)

Chapter 3 (#u72e73255-0d9e-5fec-8b9b-05b7fe646fd9)

Chapter 4 (#u078bf2c6-b406-53dd-8e0f-039c9599cf86)

Chapter 5 (#u7ad6d2ec-9611-583e-8638-b6ba35457c5f)

Chapter 6 (#u6652864d-5b09-586c-826d-c01e82adef97)

Chapter 7 (#u4d76b038-6752-535d-8d04-aa0f303be8a7)

Chapter 8 (#u0fcf8ee3-006c-5469-9a32-c411aaefa8ad)

Chapter 9 (#u06977325-bd76-5253-9c65-d99179d3bf4f)

Chapter 10 (#u58942ceb-b306-5bee-ae85-cefe3b82ab29)

Chapter 11 (#u5c4f141a-9f80-557b-b05a-8d998be1270a)

Chapter 12 (#u9a9e2604-0bd1-532f-ae90-5e7ef4c75316)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 39 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 40 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 41 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 42 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 43 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 44 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 45 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 46 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 47 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 48 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 49 (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Dean Koontz (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 1 (#ulink_c7d34e06-f07c-58b3-905e-9e824142108a)

It’s only life. We all get through it.

Not all of us complete the journey in the same condition. Along the way, some lose their legs or eyes in accidents or altercations, while others skate through the years with nothing worse to worry about than an occasional bad-hair day.

I still possessed both legs and both eyes, and even my hair looked all right when I rose that Wednesday morning in late January. If I returned to bed sixteen hours later, having lost all of my hair but nothing else, I would consider the day a triumph. Even minus a few teeth, I’d call it a triumph.

When I raised the window shades in my bedroom, the cocooned sky was gray and swollen, windless and still, but pregnant with a promise of change.

Overnight, according to the radio, an airliner had crashed in Ohio. Hundreds perished. The sole survivor, a ten-month-old child, had been found upright and unscathed in a battered seat that stood in a field of scorched and twisted debris.

Throughout the morning, under the expectant sky, low sluggish waves exhausted themselves on the shore. The Pacific was gray and awash with inky shadows, as if sinuous sea beasts of fantastical form swam just below the surface.

During the night, I had twice awakened from a dream in which the tide flowed red and the sea throbbed with a terrible light.

As nightmares go, I’m sure you’ve had worse. The problem is that a few of my dreams have come true, and people have died.

While I prepared breakfast for my employer, the kitchen radio brought news that the jihadists who had the previous day seized an ocean liner in the Mediterranean were now beheading passengers.

Years ago I stopped watching news programs on television. I can tolerate words and the knowledge they impart, but the images undo me.

Because he was an insomniac who went to bed at dawn, Hutch ate breakfast at noon. He paid me well, and he was kind, so I cooked to his schedule without complaint.

Hutch took his meals in the dining room, where the draperies were always closed. Not one bright sliver of any windowpane remained exposed.

He often enjoyed a film while he ate, lingering over coffee until the credits rolled. That day, rather than cable news, he watched Carole Lombard and John Barrymore in Twentieth Century.

Eighty-eight years old, born in the era of silent films, when Lillian Gish and Rudolph Valentino were stars, and having later been a successful actor, Hutch thought less in words than in images, and he dwelt in fantasy.

Beside his plate stood a bottle of Purell sanitizing gel. He lavished it on his hands not only before and after eating, but also at least twice during a meal.

Like most Americans in the first decade of the new century, Hutch feared everything except what he ought to fear.

When TV-news programs ran out of stories about drunk, drug-addled, murderous, and otherwise crazed celebrities—which happened perhaps twice a year—they sometimes filled the brief gap with a sensationalistic piece on that rare flesh-eating bacteria.

Consequently, Hutch feared contracting the ravenous germ. From time to time, like a dour character in a tale by Poe, he huddled in his lamplit study, brooding about his fate, about the fragility of his flesh, about the insatiable appetite of his microscopic foe.

He especially dreaded that his nose might be eaten away.

Long ago, his face had been famous. Although time had disguised him, he still took pride in his appearance.

I had seen a few of Lawrence Hutchison’s movies from the 1940s and ’50s. I liked them. He’d been a commanding presence on screen.

Because he had not appeared on camera for five decades, Hutch was less known for his acting than for his children’s books about a swashbuckling rabbit named Nibbles. Unlike his creator, Nibbles was fearless.

Film money, book royalties, and a habit of regarding investment opportunities with paranoid suspicion had left Hutch financially secure in his old age. Nevertheless, he worried that an explosive rise in the price of oil or a total collapse in the price of oil would lead to a worldwide financial crisis that would leave him penniless.

His house faced the boardwalk, the beach, the ocean. Surf broke less than a minute’s stroll from his front door.

Over the years, he had come to fear the sea. He could not bear to sleep on the west side of the house, where he might hear the waves crawling along the shore.

Therefore, I was quartered in the ocean-facing master suite at the front of the house. He slept in a guest room at the back.

Within a day of arriving in Magic Beach, more than a month previous to the red-tide dream, I had taken a job as Hutch’s cook, doubling as his chauffeur on those infrequent occasions when he wanted to go out.

My experience at the Pico Mundo Grill served me well. If you can make hash browns that wring a flood from salivary glands, fry bacon to the crispness of a cracker without parching it, and make pancakes as rich as pudding yet so fluffy they seem to be at risk of floating off the plate, you will always find work.

At four-thirty that afternoon in late January, when I stepped into the parlor with Boo, my dog, Hutch was in his favorite armchair, scowling at the television, which he had muted.

“Bad news, sir?”

His deep and rounded voice rolled an ominous note into every syllable: “Mars is warming.”

“We don’t live on Mars.”

“It’s warming at the same rate as the earth.”

“Were you planning to move to Mars to escape global warming?”

He indicated the silenced anchorman on the TV. “This means the sun is the cause of both, and nothing can be done about it. Nothing.”

“Well, sir, there’s always Jupiter or whatever planet lies beyond Mars.”

He fixed me with that luminous gray-eyed stare that conveyed implacable determination when he had played crusading district attorneys and courageous military officers.

“Sometimes, young man, I think you may be from beyond Mars.”

“Nowhere more exotic than Pico Mundo, California. If you won’t need me for a while, sir, I thought I’d go out for a walk.”

Hutch rose to his feet. He was tall and lean. He kept his chin lifted but craned his head forward as does a man squinting to sharpen his vision, which might have been a habit that he developed in the years before he had his cataracts removed.

“Go out?” He frowned as he approached. “Dressed like that?”

I was wearing sneakers, jeans, and a sweatshirt.

He was not troubled by arthritis and remained graceful for his age. Yet he moved with precision and caution, as though expecting to fracture something.

Not for the first time, he reminded me of a great blue heron stalking tide pools.

“You should put on a jacket. You’ll get pneumonia.”

“It’s not that chilly today,” I assured him.

“You young people think you’re invulnerable.”

“Not this young person, sir. I’ve got every reason to be astonished that I’m not already permanently horizontal.”

Indicating the words MYSTERY TRAIN on my sweatshirt, he asked, “What’s that supposed to mean?”

“I don’t know. I found it in a thrift shop.”

“I have never been in a thrift shop.”

“You haven’t missed much.”

“Do only very poor people shop there or is the criteria merely thriftiness?”

“They welcome all economic classes, sir.”

“Then I should go one day soon. Make an adventure of it.”

“You won’t find a genie in a bottle,” I said, referring to his film The Antique Shop.

“No doubt you’re too modern to believe in genies and such. How do you get through life when you’ve nothing to believe in?”

“Oh, I have beliefs.”

Lawrence Hutchison was less interested in my beliefs than in the sound of his well-trained voice. “I keep an open mind regarding all things supernatural.”

I found his self-absorption endearing. Besides, if he were to have been curious about me, I would have had a more difficult time keeping all my secrets.

He said, “My friend Adrian White was married to a fortune-teller who called herself Portentia.”

I traded anecdotes with him: “This girl I used to know, Stormy Llewellyn—at the carnival, we got a card from a fortune-telling machine called Gypsy Mummy.”

“Portentia used a crystal ball and prattled a lot of mumbo jumbo, but she was the real thing. Adrian adored her.”

“The card said Stormy and I would be together forever. But it didn’t turn out that way.”

“Portentia could predict the day and very hour of a person’s death.”

“Did she predict yours, sir?”

“Not mine. But she predicted Adrian’s. And two days later, at the hour Portentia had foretold, she shot him.”

“Incredible.”

“But true, I assure you.” He glanced toward a window that did not face the sea and that, therefore, was not covered by draperies. “Does it feel like tsunami weather to you, son?”

“I don’t think tsunamis have anything to do with the weather.”

“I feel it. Keep one eye on the ocean during your walk.”

Like a stork, he stilted out of the parlor and along the hallway toward the kitchen at the back of the house.

I left by the front door, through which Boo had already passed. The dog waited for me in the fenced yard.

An arched trellis framed the gate. Through white lattice twined purple bougainvillea that produced a few flowers even in winter.

I closed the gate behind me, and Boo passed through it as for a moment I stood drawing deep breaths of the crisp salted air.

After spending a few months in a guest room at St. Bartholomew’s Abbey, high in the Sierra, trying to come to terms with my strange life and my losses, I had expected to return home to Pico Mundo for Christmas. Instead, I had been called here, to what purpose I didn’t know at the time and still had not deduced.

My gift—or curse—involves more than a rare prophetic dream. For one thing, irresistible intuition sometimes takes me places to which I would not go by choice. And then I wait to find out why.

Boo and I headed north. Over three miles long, the boardwalk serving Magic Beach was not made of wood but of concrete. The town called it a boardwalk anyway.

Words are plastic these days. Small loans made to desperate people at exorbitant interest rates are called payday advances. A cheesy hotel paired with a seedy casino is called a resort. Any assemblage of frenetic images, bad music, and incoherent plot is called a major motion picture.

Boo and I followed the concrete boardwalk. He was a German shepherd mix, entirely white. The moon traveling horizon to horizon moved no more quietly than did Boo.

Only I was aware of him, because he was a ghost dog.

I see the spirits of dead people who are reluctant to move on from this world. In my experience, however, animals are always eager to proceed to what comes next. Boo was unique.

His failure to depart was a mystery. The dead don’t talk, and neither do dogs, so my canine companion obeyed two vows of silence.

Perhaps he remained in this world because he knew I would need him in some crisis. He might not have to linger much longer, as I frequently found myself up to my neck in trouble.

On our right, after four blocks of beachfront houses came shops, restaurants, and the three-story Magic Beach Hotel with its white walls and striped green awnings.

To our left, the beach relented to a park. In the sunless late afternoon, palm trees cast no shadows on the greensward.

The lowering sky and the cool air had discouraged beachgoers. No one sat on the park benches.

Nevertheless, intuition told me that she would be here, not in the park but sitting far out above the sea. She had been in my red dream.

Except for the lapping of the lazy surf, the day was silent. Cascades of palm fronds waited for a breeze to set them whispering.

Broad stairs led up to the pier. By virtue of being a ghost, Boo made no sound on the weathered planks, and as a ghost in the making, I was silent in my sneakers.

At the end of the pier, the deck widened into an observation platform. Coin-operated telescopes offered views of ships in transit, the coastline, and the marina in the harbor two miles north.

The Lady of the Bell sat on the last bench, facing the horizon, where the moth-case sky met the sullen sea in seamless fusion.

Leaning on the railing, I pretended to meditate on the timeless march of waves. In my peripheral vision, I saw that she seemed to be unaware of my arrival, which allowed me to study her profile.

She was neither beautiful nor ugly, but neither was she plain. Her features were unremarkable, her skin clear but too pale, yet she had a compelling presence.

My interest in her was not romantic. An air of mystery veiled her, and I suspected that her secrets were extraordinary. Curiosity drew me to her, as did a feeling that she might need a friend.

Although she had appeared in my dream of a red tide, perhaps it would not prove to be prophetic. She might not die.

I had seen her here on several occasions. We had exchanged a few words in passing, mostly comments about the weather.

Because she talked, I knew she wasn’t dead. Sometimes I realize an apparition is a ghost only when it fades or walks through a wall.

On other occasions, when they have been murdered and want me to bring their killers to justice, they may choose to materialize with their wounds revealed. Confronted by a man whose face has imploded from the impact of a bullet or by a woman carrying her severed head, I am as quick as the next guy to realize I’m in the company of a spook.

In the recent dream, I had been standing on a beach, snakes of apocalyptic light squirming across the sand. The sea had throbbed as some bright leviathan rose out of the deep, and the heavens had been choked with clouds as red and orange as flames.

In the west, the Lady of the Bell, suspended in the air above the sea, had floated toward me, arms folded across her breast, her eyes closed. As she drew near, her eyes opened, and I glimpsed in them a reflection of what lay behind me.

I had twice recoiled from the vision that I beheld in her eyes, and I had both times awakened with no memory of it.

Now I walked away from the pier railing, and sat beside her. The bench accommodated four, and we occupied opposite ends.

Boo curled up on the deck and rested his chin on my shoes. I could feel the weight of his head on my feet.

When I touch a spirit, whether dog or human, it feels solid to me, and warm. No chill or scent of death clings to it.

Still gazing out to sea, the Lady of the Bell said nothing.

She wore white athletic shoes, dark-gray pants, and a baggy pink sweater with sleeves so long her hands were hidden in them.

Because she was petite, her condition was more apparent than it would have been with a larger woman. A roomy sweater couldn’t conceal that she was about seven months pregnant.

I had never seen her with a companion.

From her neck hung the pendant for which I had named her. On a silver chain hung a polished silver bell the size of a thimble. In the sunless day, this simple jewelry was the only shiny object.

She might have been eighteen, three years younger than I was. Her slightness made her seem more like a girl than like a woman.

Nevertheless, I had not considered calling her the Girl of the Bell. Her self-possession and calm demeanor required lady.

“Have you ever heard such stillness?” I asked.

“There’s a storm coming.” Her voice floated the words as softly as a breath of summer sets dandelion seeds adrift. “The pressure in advance weighs down the wind and flattens the waves.”

“Are you a meteorologist?”

Her smile was lovely, free of judgment and artifice. “I’m just a girl who thinks too much.”

“My name’s Odd Thomas.”

“Yes,” she said.

Prepared to explain the dysfunctional nature of my family that had resulted in my name, as I had done countless times before, I was surprised and disappointed that she had none of the usual questions.

“You knew my name?” I asked.

“As you know mine.”

“But I don’t.”

“I’m Annamaria,” she said. “One word. It would have come to you.”

Confused, I said, “We’ve spoken before, but I’m sure we’ve never exchanged names.”

She only smiled and shook her head.

A white flare arced across the dismal sky: a gull fleeing to land as the afternoon faded.

Annamaria pulled back the long sleeves of her sweater, revealing her graceful hands. In the right she held a translucent green stone the size of a fat grape.

“Is that a jewel?” I asked.

“Sea glass. A fragment of a bottle that washed around the world and back, until it has no sharp edges. I found it on the beach.” She turned it between her slender fingers. “What do you think it means?”

“Does it need to mean anything?”

“The tide washed the sand as smooth as a baby’s skin, and as the water winked away, the glass seemed to open like a green eye.”

The shrieking of birds shattered the stillness, and I looked up to see three agitated sea gulls sailing landward.

Their cries announced company: footfalls on the pier behind us.

Three men in their late twenties walked to the north end of the observation platform. They stared up the coast toward the distant harbor and marina.

The two in khakis and quilted jackets appeared to be brothers. Red hair, freckles. Ears as prominent as handles on beer mugs.

The redheads glanced at us. Their faces were so hard, their eyes so cold, I might have thought they were evil spirits if I hadn’t heard their footsteps.

One of them favored Annamaria with a razor-slash smile. He had the dark and broken teeth of a heavy methamphetamine user.

The freckled pair made me uneasy, but the third man was the most disturbing of the group. At six four, he towered half a foot above the others, and had that muscled massiveness only steroid injections can produce.

Unfazed by the cool air, he wore athletic shoes without socks, white shorts, and a yellow-and-blue, orchid-pattern Hawaiian shirt.

The brothers said something to him, and the giant looked at us. He might be called handsome in an early Cro-Magnon way, but his eyes seemed to be as yellow as his small chin beard.

We did not deserve the scrutiny we received from him. Annamaria was an ordinary-looking pregnant woman, and I was just a fry cook who had been fortunate enough to reach twenty-one years of age without losing a leg or an eye, or my hair.

Malevolence and paranoia cohabit in a twisted mind. Bad men trust no one because they know the treachery of which they themselves are capable.

After a long suspicious stare, the giant turned his attention once more to the northern coast and the marina, as did his cohorts, but I didn’t think they were done with us.

Half an hour of daylight remained. Because of the overcast, however, twilight seemed to be already upon us. The lampposts lining the pier brightened automatically, but a thin veil of fog had risen out of nowhere to aid and abet the coming dusk.

Boo’s behavior confirmed my instincts. He had gotten to his feet. Hackles raised, ears flattened, he focused intently on the giant.

To Annamaria, I said, “I think we better go.”

“Do you know them?”

“I’ve seen their kind before.”

As she rose from the bench, she closed the green orb in her right fist. Both hands shrank back into the sleeves of her sweater.

I sensed strength in her, yet she also had an aura of innocence, an almost waiflike air of vulnerability. The three men were the kind to whom vulnerability had a scent as surely as rabbits hidden in tall grass have a smell easily detected by wolves.

Bad men wound and destroy one another, although as targets they prefer those who are innocent and as pure as this world allows anyone to be. They feed on violence, but they feast on the despoiling of what is good.

As Annamaria and I walked off the observation deck and toward the shore, I was dismayed that no one had come onto the pier. Usually a few evening fishermen would already have arrived with rods and tackle boxes.

I glanced back and saw Boo moving closer to the three men, who were oblivious of him. The hulk with the chin beard looked over the heads of the other two, again staring at Annamaria and me.

The shore was still distant. The shrouded sun slowly sank behind a thousand fathoms of clouds, toward the drowning horizon, and rising mist damped the lamplight.

When I looked back again, the freckled pair were approaching at a brisk walk.

“Keep going,” I told Annamaria. “Off the pier, among people.”

She remained calm. “I’ll stay with you.”

“No. I can handle this.”

Gently, I pushed her ahead of me, made sure that she kept moving, and then turned toward the redheads. Instead of standing my ground or backing away, I walked toward them, smiling, which surprised them enough to bring them to a halt.

As the one with the bad teeth looked past me at Annamaria, and as number two reached inside his unzipped jacket, I said, “You guys know about the tsunami warning?”

Number two kept his hand in his jacket, and the poster boy for dental hygiene shifted his attention to me. “Tsunami?”

“They estimate twenty to thirty feet.”

“They who?”

“Even thirty feet,” I said, “won’t wash over the pier. She got scared, didn’t want to stay, but I want to ride it out, see it. We must be—what?—forty feet off the water. It could be cool.”

Throughout all this, the big guy had been approaching. As he joined us, number two asked him, “You hear about a tsunami?”

I said with some excitement, “The break slope on the shore here is twenty feet, but the other ten feet of the wave, man, it’s gonna wipe out the front row of buildings.”

Glancing back, as if to assess the potential for destruction, I was relieved to see Annamaria reaching the end of the pier.

“But the pier has deep pilings,” I said. “The pier will ride it out. I’m pretty sure. It’s solid. Don’t you think the pier will ride it out?”

The big guy’s mother had probably told him that he had hazel eyes. Hazel is a light golden-brown. He did not have hazel eyes. They were yellow rather than golden, and they were more yellow than brown.

If his pupils had been elliptical instead of round, I could almost have believed that he was a humanoid puppet and that an intelligent mutant cat was curled up in his skull, peering at me through the empty sockets. And not a nice intelligent mutant cat.

His voice dispelled the feline image, for it had a timbre more suited to a bear. “Who’re you?”

Instead of answering, I pretended excitement about the coming tsunami and looked at my wristwatch. “It could hit shore in like a few minutes. I gotta be on the observation deck when it comes.”

“Who’re you?” the hulk repeated, and he put his big right paw on my left shoulder.

The instant he touched me, reality flipped out of sight as if it were a discarded flashcard. I found myself not on the pier but on the shore instead, on a beach across which squirmed reflections of fire. A hideous bright something rose in a sea that pulsed with hellish light under an apocalyptic sky.

The nightmare.

Reality flipped into view again.

The hulk had snatched his hand back from my shoulder. With his wide eyes focused on his spread fingers, he looked as if he had been stung—or had seen the red tide of my dream.

Never before had I passed a dream or a vision, or a thought, or anything but a head cold, to someone else by a touch. Surprises like this spare me from a dull life.

Like the cold-jewel stare of a stone-temple god, the yellow gaze fixed on me again, and he said, “Who the hell are you?”

The tone of his voice alerted the redheads that an extraordinary event had occurred. The one with his hand inside his jacket withdrew a pistol, and the one with bad teeth reached into his jacket, most likely not for dental floss.

I ran three steps to the side of the pier, vaulted the railing, and dropped like a fry cook through mist and fading light.

Cold, dark, the Pacific swallowed me, my eyes burned in the brine, and as I swam beneath the surface, I fought the buoyant effect of the salt water, determined that the sea would not spit me up into a bullet-riddled twilight.

CHAPTER 2 (#ulink_6f3eb8c8-ca06-5291-9258-9322919737cd)

Stung, my wide-open eyes salted the seawater with tears.

As I breast-stroked and frog-kicked, the marine murk at first seemed to be without a scintilla of light. Then I became aware of a sullen-green phosphorescence, universally distributed, through which faint amorphous shadows writhed, perhaps clouds of sand swept off the bottom or long undulant stalks and fronds of seaweed.

The green dismalness abruptly darkened into true gloom. I had swum under the pier, between two of the many concrete columns on which the timber support posts stood.

A blind moment later, I encountered another column bristling with barnacles. I followed it to the surface.

Gasping for air that smelled of iodine and tar, that tasted of salt and chalk, I clung to the encrusted concrete, the barnacles sharp and slick under my hands, and I pulled my sweatshirt sleeves down to protect against cuts as best I could.

At the moment low on energy, the ocean rolled rhythmically and without violence between the pilings, toward shore. Although tame, it nevertheless sought to pull me away from the column.

Every minute I strove to hold fast would drain my strength. My sodden sweatshirt felt like a heavy flak jacket.

The liquid soliloquy of the sea echoed in murmurs and whispers along the pier floor, which was now my ceiling. I heard no shouts from above, no thunder of running footsteps.

Daylight as clouded and as gray as bilge water seeped into this sheltered space. Overhead, an architecture of thick vertical posts, horizontal tie beams, struts, and purlins dwindled into shadows.

The top of this piling, on which one of the posts stood, lay less than three feet above my head. I toed and kneed and clawed upward, repeatedly slipping backward but stubbornly gaining more ground than I lost.

These barnacles were of the stalkless variety, snugged tight to the concrete. As inch by inch I pulled myself out of the water, the calcareous shells of the crustaceans cracked and splintered, so the air smelled and tasted chalkier than ever.

This was no doubt a cataclysm for the barnacle community. I felt some regret about the destruction I wreaked, although not as much as I would have felt if, weighed down and weakened by my sodden clothes, I had sunk deep into snares of seaweed, and drowned.

Seated on the thirty-inch-diameter concrete base, an eighteen-inch-diameter wooden column rose high into shadows. Thick stainless-steel pitons had been driven into the wood to serve as handholds and as anchors for safety lines during construction. Using these, I pulled myself onto the six-inch ledge that encircled the post.

Standing there on my toes, dripping and shivering, I tried to find the bright side to my current situation.

Pearl Sugars, my maternal grandmother, a fast-driving and hard-drinking professional poker player now deceased, always encouraged me to find the bright side of any setback.

“If you let the bastards see you’re worried,” Granny Sugars said, “they’ll shake you, break you, and be walking around in your shoes tomorrow.”

She traveled the country to high-stakes private games in which the other players were men, most of them not nice men, some of them dangerous. Although I understood Granny’s point, her solemn advice conjured in my mind an image of scowling tough guys parading around in Granny’s high-heels.

As my racing heart slowed and as I caught my breath, the only bright side I could discern was that if I lived to be an old man—a one-eyed, one-armed, one-legged, hairless old man without a nose—at least I wouldn’t be able to complain that my life had lacked for adventure.

Most likely the mist and the murky water had prevented the hulk with the chin beard and the two gunmen from seeing that I had taken refuge under the pier. They would expect me to swim to shore, and they would by now be arrayed along the beach, searching the low swells for a swimmer.

Although I had leaped off the pier in the last quarter of its length, the tide had carried me closer to land as I’d been swimming for cover. I remained, however, seaward of the structure’s midpoint.

From my current perch, I could see a length of the shore. But I doubted that anyone patrolling the beach would have been able to catch sight of me in the deepening gloom.

Nevertheless, when not throwing myself headlong into trouble and leaping off piers, I am a prudent young man. I suspected I would be wise to ascend farther into the webwork of wood.

In some cozy high redoubt, I would roost until the thugs decided that I had drowned. When they went away to raise a toast to my death in whatever greasy barroom or opium den their kind frequented, I would safely go ashore and return home, where Hutch would be washing his face in sanitizing gel and waiting for the tsunami.

Piton to piton, I climbed the pole.

During the first ten feet or so, those eyeletted spikes were solidly planted. Perhaps the greater humidity near the water kept the wood swollen tight around them.

As I continued to ascend, I found some pitons that moved in my hands, the aged and drier wood having shrunk somewhat away from them. They bore my weight, did not pull loose.

Then under my right foot, a piton ripped from the post. With a clink, the spike bounced off the concrete below, and I could even hear the faint plop as it met the sea.

I have no incapacitating fear of either heights or darkness. We spend nine months in a nurturing darkness before we’re born, and we aspire to the highest of all places when we die.

As the day faded and as I climbed into the substructure of the pier, the shadows grew deeper, more numerous. They joined with one another like the billowing black cloaks of Macbeth’s witches as they gathered around their cauldron.

Since going to work for Hutch, I had read some of the volumes of Shakespeare’s plays that were in his library. Ozzie Boone, the famous mystery writer, my mentor and cherished friend in Pico Mundo, would be delighted if he knew that I was thus continuing my education.

In high school, I had been an indifferent student. In part, my lack of academic achievement could be attributed to the fact that while other kids were at home, dutifully poring through their Macbeth assignment, I was being chained to a pair of dead men and dumped off a boat in the middle of Malo Suerte Lake.

Or I was bound with rope, hanging from a rack in a refrigerated meat locker, beside a smiling Japanese chiropractor, waiting for a quartet of unreasonable men to return and torture us, as they had promised to do.

Or I had stepped into the parked motor home of an itinerant serial killer who might return at any moment, where I had discovered two ferocious attack dogs that were determined to keep me from leaving, against which I had no weapons or defenses except one fluffy pink dust mop and six cans of warm Coke, which when shaken spewed foamy streams that terrified the killer canines.

As a teenager, I always intended to do my homework. But when the supplicant dead come to you for justice and you also have occasional prophetic dreams, life tends to interfere with your studies.

Now, as I hung twenty feet above the surface of the sea, the witchy shadows closed around me so completely that I couldn’t see the next piton thrusting from the pole above my head. I halted, pondering whether I could ascend safely in the pitch dark or should retreat to the narrow concrete ledge below.

The penetrating odor of creosote, applied to preserve the wood, had grown thicker as I climbed. I could no longer smell the ocean or the wet concrete pilings, or even my sweat: only the astringent scent of the preservative.

Just as I decided that prudence—which, as you know, is one of my most reliable character traits—required me to go back down to the ledge, lights blinked on under the pier.

Fixed to numerous wooden posts, five feet below my position, floodlights were directed down toward the sea. A long line of them extended from one end of the structure to the other.

I could not recall if the underside of the pier had been illuminated on other nights. These lamps might be automatically activated every evening at dusk.

If the floodlights were only for emergency situations, such as in the event someone fell off the pier, then perhaps a responsible citizen had seen me go over the side and had alerted the authorities.

More likely, the hulk and the redheaded gunmen had known where to find the switch. In that case, they had glimpsed me underwater, making for cover, and they had wasted no time scanning the incoming tide for a shorebound swimmer.

As I hung there in a quandary, trying to decide whether this meant I should continue upward or perhaps return to the water, I heard what for a moment I thought was a chain saw in the distance. Then I recognized the sound as that of an outboard engine.

After ten or fifteen seconds, the engine throttled back. The consequent throbbing chug could not be mistaken for anything but an outboard.

Cocking my head left, right, I tried to hear around the thick support to which I clung. Sounds bounced deceptively through the ranks of posts and crossbeams and ricocheted off the gently rolling water, but after half a minute, I was sure the craft was proceeding slowly shoreward from the ocean-end of the pier.

I looked westward but could not see the boat for the intervening substructure. The pilot might be cruising in open water, paralleling the pier, or he could be threading through the pilings to conduct a more thorough search.

Although the floodlamps were below my position and were directed downward, light bounced off the moving water. Shimmering phantoms swooped up the columns, across the horizontal beams, and fluttered all the way up against the underside of the pier deck.

In these quivering reflections, I was revealed. An easy target.

If I descended now, I would be going down to death.

Considering the events of the last couple of years, I was ready for death when my time came, and I did not fear it. But if suicide damns the soul, then I would never see my lost girl again. Peace is not worth the slightest risk of being denied that reunion.

Besides, I suspected that Annamaria was in trouble and that I had been drawn to Magic Beach, in part, to help her.

I climbed more rapidly than before, hoping to find a junction of beams or an angular nest between purlins and posts where I would be hidden not merely from the floodlamps reflecting off the water but also from probing flashlights, if the searchers had any.

Although I wasn’t afraid of heights, I could have composed an almost infinite list of places that I would rather have been than up a pier post, much like a cat treed by wolves. I counseled myself to be grateful that, indeed, there were not vicious attack dogs below; although on the other hand, to assist in self-defense, I didn’t have even so much as a fluffy pink dust mop or a six-pack of warm Cokes.

CHAPTER 3 (#ulink_a3691fd3-2d88-5aa2-8092-a77f1ff1e6b3)

Monkey-quick but clumsy in my desperation, I scrambled up the post, feet stepping where my hands had grasped a moment earlier.

A loose piton cracked out of dry wood underfoot and fell away, and rang off concrete below. The chug of the approaching outboard masked the sound of the water receiving the steel.

The post bypassed a massive crossbeam. I clambered and clawed sideways onto that horizontal surface with such an ungainly series of maneuvers that no observer would have mistaken me for a member of a species that lived in trees and ate bananas by the bunch.

Although the beam was wide, it was not as wide as I was. Like radiant spirits, the leaping bright reflections of floodlamps off the rolling sea soared and swooned over me, making of me a pigeon, easy plinking for a practiced gunman shooting from below.

Fleeing on all fours is fine if your four are all feet, but hands and knees don’t allow much speed. Grateful that I was not afraid of high places, wishing that my stomach shared my insouciance about heights, I stood and my stomach sank.

I peered down into the drink and grew a little dizzy, then glanced west toward the grumble of the outboard. The ranks of intervening pier supports hid the boat from me.

At once, I discovered why high-wire walkers use a balance pole. With my arms tucked close to my sides and hands tensely fisted, I wobbled as if I were a drunk who had failed out of a twelve-step program in just four steps.

Defensively, I spread my arms and opened my hands. I cautioned myself not to look down at my feet but, instead, at the beam ahead, where I wanted my feet to go.

Quivering specters of reflected light painted an illusion of water across the beam and the surrounding posts, raising in me the irrational feeling that I would be washed off my perch.

This high above the sea, under the cowl of the pier, the odor of creosote intensified. My sinuses burned, and my throat. When I licked my dry lips, the taste of coal tar seemed to have condensed on them.

I halted and closed my eyes for a moment, shutting out the leaping ghosts of light. I held my breath and pressed away the dizziness, and moved on.

When I had crossed half the width of the pier, the north-south beam intersected another running east-west.

The outboard had grown louder, therefore nearer. Still the searchers had not hoved into view below.

I turned east, onto the intersecting beam. Always putting foot in front of foot on the narrow path, I was not as fleet as a ballet dancer hurrying en pointe across a stage, but I made swift progress.

My jeans did not accommodate such movement as well as a pair of tights would have. Instead they kept binding where too much binding would squeeze my voice into a permanent falsetto.

I crossed another intersection, continuing east, and wondered if I might be able to flee through this support structure all the way to shore.

Behind me, the outboard growled louder. Above the buzz of the engine, I heard the boat’s wake slapping against the concrete support columns twenty feet below, which suggested not just that the craft was making greater speed than previously but also that it was close.

As I approached another intersection, two radiant red eyes, low in front of me, brought me to a stop. The fairy light teased fitfully across the shape before me, but then revealed a rat sitting precisely where the two beams joined.

I am not afraid of rats. Neither am I so tolerant that I would welcome a swarm of them into my home in a spirit of interspecies brotherhood.

The rat was paralyzed by the sight of me looming over it. If I advanced another step, it had three routes by which it could flee to safety.

In moments of stress, my imagination can be as ornate as a carousel of grotesque beasts, standing on end like a Ferris wheel, spinning like a coin, casting off kaleidoscopic visions of ludicrous fates and droll deaths.

As I confronted the rat, I saw in my mind’s eye a scenario in which I startled the rodent, whereupon it raced toward me in a panic, slipped under a leg of my jeans, squirmed up my calf, squeaked behind my knee, wriggled along my thigh, and decided to establish a nest between my buttocks. Through all of this, I would be windmilling my arms and hopping on one foot until I hopped off the beam and, with the hapless rodent snugged between my cheeks, plunged toward the sea just in time to crash into the searchers’ boat, smashing a hole in the bottom with my face, thereupon breaking my neck and drowning.

You might think that I have earned the name Odd Thomas, but it has been mine since birth.

The racket of the outboard sawed through the support posts, echoing and re-echoing until it seemed that legions of lumberjacks were at work, intent on felling the entire structure.

When I took a step toward the rat, the rat did not relent. As I had nothing better to do, I took another step, then halted because the noise of the outboard abruptly became explosive.

I dared to look down. An inflatable dinghy passed below, wet black rubber glossy under the floodlamps.

The hulk in the Hawaiian shirt sat on the stern-most of two thwarts, one hand on the steering arm of the engine. He piloted the boat with expertise, weaving at speed between the concrete columns, as if late for a luau.

On the longer port and starboard inflation compartments that formed the rounded bulwarks of the craft, in yellow letters, were the words MAGIC BEACH/HARBOR DEPT. The dinghy must have been tied up to the pier; the giant had boldly stolen it to search for me.

Yet he never looked up between the floodlamps as he passed under me. If the dinghy doubled as a search-and-rescue craft, waterproof flashlights would be stowed aboard; but the hulk wasn’t using one.

The small craft disappeared among the staggered rows of columns. The engine noise gradually diminished. The ripples and dimples of the dinghy’s modest wake were smoothed away by the self-ironing sea.

I had expected to see three men in the boat. I wondered where the dead-eyed redheads had gone.

The other rat had vanished, too, but not up a leg of my blue jeans.

Exhibiting balletic poise, foot in front of foot, I stepped into the junction of beams, which the trembling rodent had once occupied. I meant to continue shoreward, but I stopped.

Now that the blond giant was under the pier, between me and the beach, I was not confident of continuing in that direction.

The mood had changed. An overwhelming sense of peril, of being in the mortal trajectory of a bullet, had propelled me into frantic flight. Now death seemed no less possible than it had before the passage of the dinghy, but less imminent.

The moment felt dangerous rather than perilous, characterized by uncertainty and by the tyranny of chance. If a bullet was coming, I now had hope of dodging it, though only if I made the right moves.

I looked north, east, south along the horizontal beams. West, over my shoulder. Down into floodlit tides. I looked up toward the underside of the pier deck, where the dancing sea translated itself into phrases of half-light that swelled and fluttered and shrank and swelled in an eerie choreography through geometric beams and braces.

I felt as indecisive as the feckless mob in The Second Part of King Henry the Sixth, Act 4, when they vacillate repeatedly between swearing loyalty to the grotesque Cade, then to the rightful king.

Shakespeare again. Once you let him into your head, he takes up tenancy and will not leave.

The sound of the outboard engine had been waning. Abruptly it cut out altogether.

Briefly the silence seemed perfect. Then the wordless whispering and the soft idiot chuckling of the sea began to echo off surrounding surfaces.

In the brief period since the dinghy had passed under me, it could not have traveled all the way to the beach. It had probably gone little more than half that distance.

The hulk at the tiller would not surrender steering to the sea and let it pinball the dinghy from post to post. He must have somehow tied up to one of the concrete columns.

He would not have moored the dinghy unless he intended to disembark from it. Already he must be climbing into the pier support structure ahead of me.

Certain that I knew where the redheaded gunmen were, I looked over my shoulder, through the labyrinth of posts and beams to the west. They were not yet in sight.

One in front of me. Two behind. The jaws of a nutcracker.

CHAPTER 4 (#ulink_5b6f82eb-073a-5b59-8b2a-6c6519c66e7e)

While I dithered at the intersection of support beams, a pale form loomed out of the south, to my right.

Because occasionally spirits manifest suddenly, unexpectedly, with no regard for my nerves, I don’t startle easily. I swayed on the timber but did not plummet from it.

My visitor proved to be Boo, good dog and former mascot of St. Bartholomew’s Abbey in the California Sierra.

He could be seen by no one but me, and no touch but mine could detect any substance to him. Yet to my eyes at least, the shimmering reflections sprayed up by the rolling sea played off his flanks and across his face, as if he were as solid as I was.

Although he could have appeared in midair, he walked the crossbeam toward me, like the ghost of Hamlet’s father approaching the doomed prince on the platform before the castle.

Well, no. Boo had a tail, soft fur, and a friendly smile. Hamlet’s father had none of that, although Hollywood would no doubt eventually give him all three in some misguided adaptation.

I hoped that the Hamlet comparison was inappropriate in other ways. At the end of that play, the stage is littered with dead bodies.

Boo stopped when he knew that I had seen him, cocked his head, and wagged his tail. Suddenly facing away from me without having turned around, he padded south, paused, glanced back at me, and then continued.

Even if I had not watched a lot of old episodes of Lassie, I understood the dead well enough to know that I was expected to follow my dog. I took some small pride that, unlike young Timmy in the TV show, I didn’t need to be barked into obedience.

The blond hulk had not appeared in the east, nor the redheads in the west, so I hurried, if gingerly, after the ghostly shepherd, who led me toward the south side of the pier.

At the end of the timber path, I came to a large railed landing that served two flights of ascending stairs, one to the left, one to the right. The landing might have been a staging platform for workers of one kind or another.

When Boo climbed the stairs to the left, I went after him. The flight was short, and at the top lay a four-foot-wide railed catwalk.

The underside of the pier deck hung little more than one foot above my head. In this high corridor, where only a storm wind could have stirred the air, the stink of creosote thickened.

Darkness pooled deeper here than elsewhere. Nevertheless, the quivering marbled reflections, ever-changing on the ceiling, revealed electrical conduits, junction boxes, and copper pipes that must have been water lines.

The conduits brought power to the lampposts topside and to the emergency floodlamps below me. The copper lines served the freshwater faucets provided at regular intervals for the anglers who, on most nights, fished from the pier.

This catwalk, along which Boo led me, would be used by plumbers and electricians when problems arose with pier utilities.

After we had proceeded some distance shoreward, we came to a two-foot-by-five-foot pop-out in the catwalk. A wooden storage chest with two padlocks filled this space.

In the poor light, I could not see any words or markings on the chest. Perhaps it contained maintenance supplies.

Or interred in the chest might have been the shrunken remains of the pier master’s poor wife, Lorraine, who perhaps had been murdered twenty years ago when she complained once too often about a lingering creosote smell in his work clothes.

My eager imagination might have worked up a hair-raising image of Lorraine’s shriveled cadaver, pickled in creosote, if I had been able to believe there was actually such a position as a pier master. I don’t know where the name Lorraine came from.

Sometimes I am a mystery to myself.

Boo settled on the catwalk and rolled onto his side. He extended one paw toward me and raked the air—universal canine sign language that meant Sit down, stay awhile, keep me company, rub my tummy.

With three dangerous men searching for me, a tummy-rub session seemed ill-advised, like pausing in midflight across a howitzer-hammered battlefield to assume the lotus position and engage in some yoga to calm the nerves.

Then I realized that the brute in the orchid-pattern shirt was overdue for an appearance as he searched the support structure from east to west. The storage chest stood about two and a half feet high and offered cover that the open railing did not.

“Good boy,” I whispered.

Boo’s tail beat against the floor without making a sound.

I stretched out on the catwalk, on my side, left arm bent at the elbow, head resting on my palm. With my right hand, I rubbed my ghost dog’s tummy.

Dogs know we need to give affection as much as they need to receive it. They were the first therapists; they’ve been in practice for thousands of years.

After perhaps two minutes, Boo brought an end to our therapy session by rolling to his feet, ears pricked, alert.

I dared to raise my head above the storage chest. I peered down seven feet into the level of the support structure from which I had recently ascended.

At first I saw no one. Then I spotted the hulk proceeding along the series of east-west beams.

The eddying water far below cast luminous patterns that turned through the support structure like the prismatic rays from a rotating crystal chandelier in a ballroom. The hulk had no one to dance with, but he didn’t appear to be in a dancing mood, anyway.

CHAPTER 5 (#ulink_dc4e9527-d5bc-5b6f-8425-1eec12bcca3e)

The big man didn’t walk the beams with reticence and caution, as I had done, but with such confidence that his mother must have been a circus aerialist and his father a high-rise construction worker. His powerful arms were at his sides, a gun in one and a flashlight in the other.

He paused, switched on the flashlight, and searched among the vertical posts, along the horizontal supports.

On the catwalk, I ducked my head behind the storage chest. A moment later the probing light swept over me, east to west, back again, and then away.

Although Boo had moved past me and stood with his head through a gap in the railing, watching the giant, he remained visible only to me.

When the searcher had moved out of sight into the labyrinth of posts and purlins and struts, I rose to my feet. I continued east.

Padding ahead of me, Boo dematerialized. He appeared solid one moment, then became transparent, faded, vanished.

I had no idea where he went when he was not with me. Perhaps he enjoyed exploring new places as much as did any living dog, and went off to wander previously unvisited neighborhoods of Magic Beach.

Boo did not haunt this world in the way that the lingering human dead haunted it. They were by turns forlorn, fearful, angry, bitter. Transgressively, they refused to heed the call to judgment, and made this world their purgatory.

This suggested to me that the free will they had been given in this life was a heritage they carried with them into the next, which was a reassuring thought.

Boo seemed to be less a ghost than he was a guardian spirit, always happy and ready to serve, still on the earth not because he had remained behind after death but because he had been sent back. Consequently, perhaps he had the power and permission to move between worlds as he wished.

I found it comforting to imagine that when I didn’t urgently need him, he was in Heaven’s fields, at play with all the good dogs who had brightened this world with their grace and who had moved on to a place where no dog ever suffered or lived unloved.

Evidently Boo believed that for the immediate future I could muddle on without him.

I continued east along the catwalk until, glancing down at the opportune moment, I glimpsed the inflatable dinghy tied to a concrete column far below, bobbing gently on the floodlit swells. Here the hulk had ascended and had begun searching westward.

At least one-quarter of the pier’s length lay to the east of this position. I paused to brood about that.

As it turned out, Boo had been right to think that I would be able to puzzle my way through this development without his counsel. The hulk had not searched the last quarter of the support structure because he was confident that I could not have gone that far before he had climbed up here to look for me.

I did not believe, however, that he was as dumb as he was big. He would have left the last section unsearched only if, in the event that I slipped past him, someone waited on the shore to snare me.

Perhaps both redheads had not begun searching together from the west end of the pier, as I had imagined. One of them might be waiting ahead of me.

Had I been a dog and had Boo been a man, he would have given me a cookie, patted me on the head, and said, “Good boy.”

After climbing over the catwalk railing, I lowered myself onto a tie beam below, lost my balance, got it back. I went north toward the center of the pier.

Just before I reached the intersection with the east-west beam, I stepped off the timber, across a six-inch gap, and put one foot on a piton in one of the vertical supports. I grabbed another piton with one hand, and swung onto that post.

I descended to the concrete base column, slid down through the enshrouding colony of barnacles, breaking them with my jeans, taking care to spare my hands, and landed as quietly as I could on the sectioned floorboards of the inflatable dinghy. A softly rattling debris of broken crustacean shells arrived with me.

The boat bobbed under one of the floodlamps. I felt dangerously exposed and was eager to get out of there.

A mooring line extended from the bow ring to a cleat in the concrete: two horns of pitted steel that barely protruded past the barnacles. I did not dare untie the dinghy until I was prepared to struggle against the currents that would carry it toward land.

If I started the engine, the searchers would come at once. Considering the time that I, an inexperienced pilot, would need to negotiate among the pilings and into open water, I might not get out of pistol range before one of the gunmen arrived.

Therefore, I resorted to the oars. A pair were secured with Velcro straps against the starboard bulwark.

Because long oars were needed and space was at a premium in the dinghy, this pair had wooden paddles but telescoping aluminum poles. With a little fumbling and a lot of muttering—both activities at which I excel—I extended the oars and locked them at full length.

I fixed one oar in the port oarlock, but I kept the other one free. Because the staggered ranks of pilings would make it difficult if not impossible to paddle against the tide and also navigate around every column, I hoped to steer and propel the inflatable craft across the remaining width of the pier by pushing off one after another of those concrete impediments.

Finally I untied the belaying line from the cleat. Because the dinghy began at once to drift with the tide, I let the rope ravel on the floorboards as it wished.

Before the column receded beyond reach, I sat upon the forward thwart, seized the free oar, and used it to thrust off the concrete. Jaws clenched, pulse throbbing in my temples, I tried with all my strength to move the dinghy northward, across the shorebound tide.

And so it did, for a short distance, before the tide pulled it north-northeast, and then east. I corrected course by thrusting off the next piling, the next, the next, and although a couple of times the oar scraped or knocked the concrete, the sound was too brief and low to draw attention.

Inevitably, I could not entirely halt an eastward drift. But the distance to land remained great enough that I hoped the intervening supports would prevent anyone at that end of the pier from seeing me.

When open water lay ahead, I slipped the free pole into the starboard lock, and with both oars I rowed crosstide, pulling harder with the seaward paddle than with the landward.

In the open, I expected a bullet in the back. If it happened, I hoped that it would not cripple me, but cleanly kill me instead, and send me on to Stormy Llewellyn.

Full night had fallen while I had cat-and-moused through the support structure of the pier. The mist that had risen near dusk, just before I had decided Annamaria should leave the pier, was slowly thickening into a heartier brew.

The fog would cloak me quicker than the darkness alone. The poles creaked in the locks and the paddles sometimes struck splashes from the black water, but no one shouted behind me, and moment by moment, I felt more confident of escaping.

My arms began to ache, my shoulders and my neck, but I rowed another minute, another. I was increasingly impressed by the power of the sea, and grateful for the low sluggish waves.

When I allowed myself to look back, the shrouded glow of some of the pier lamps could still be discerned. But when I saw that the pier itself was lost to view in gray murk, I brought both oars aboard and dropped them on the sectioned floorboards.

Under a novice seaman, an inflatable dinghy can be a slippery beast, almost as bad as riding the back of an angry and intoxicated crocodile that wants to thrash you off and eat your cojones. But that’s a story for another time.

Fearful of falling overboard or capsizing the craft, I crept on my hands and knees to the rear thwart. I sat there with one hand on the steering arm of the outboard.

Instead of a starter rope, there was an electronic ignition, which I found by reading the engine as a blind man reads a line of Braille. A push of the button brought a roar, and then a whoosh of propeller blades chopping surf.

The engine noise prevented me from hearing any shouts that rose from the pier, but now the demonic trinity knew where I had gone.

CHAPTER 6 (#ulink_a99f54d4-009f-5aaf-b975-8f6f9eedb77e)

Steering straight to shore seemed unwise. The gunman who had been positioned at the landward end of the pier would race north along the beach, using the engine noise to maintain a fix on me.

The fog was not dense enough to bury all of Magic Beach. I could see some fuzzy lights from shoreside businesses and homes, and I used these as a guide to motor north, parallel to the coast.

For the first time since it had happened, I allowed myself to wonder why the big man’s hand upon my shoulder had cast me back into the previous night’s apocalyptic dream. I couldn’t be sure that he had shared my vision. But he had experienced something that made him want to take me somewhere private for the kind of intense questioning during which the interrogator acquires a large collection of the interrogee’s teeth and fingernails.

I thought of those yellow eyes. And of the voice that belonged to something that would eat Goldilocks with or without gravy: Who the hell are you?

My current circumstances were not conducive to calm thought and profound reasoning. I could arrive at only one explanation for the electrifying effect of his hand upon my shoulder.

My dream of that horrendous but unspecified catastrophe was not a dream but, beyond doubt now, a premonition. When the hulk touched me, he triggered a memory of the nightmare, which backwashed into him because the mysterious cataclysm that I had inadequately foreseen was one that he would be instrumental in causing.

The waves were too low to turn my stomach, but when my stomach turned nevertheless, it felt as viscous as an oyster sliding out of its shell.

When I had gone perhaps half a mile from the pier, I set the outboard’s steering arm, locked the throttle, stripped off the sodden sweatshirt that had encumbered me on my previous swim, and dived overboard.

Having worked up a sweat with my exertions, I had forgotten how cold the water was: cold enough to shock the breath out of me. I went under. A current sucked me down. I fought upward, broke the surface, spat out a mouthful of seawater, and gasped for air.

I rolled onto my back, using a flutter kick and a modified butterfly stroke to make for land at an easy pace. If one of the redheads waited on the shore for me, I wanted to give him time to hear the dinghy proceeding steadily north and to decide either to follow it or to return to the pier.

Besides, maybe a shark, a really huge shark, a giant mutant shark of unprecedented size would surface under me, kill me with one bite, and swallow me whole. In that event, I would no longer have to worry about Annamaria, the people of Magic Beach, or the possible end of the world.

All but effortlessly afloat in the buoyant salt water, gazing up into the featureless yet ever-changing fog, with no sounds but my breathing and the slop of water washing in and out of my ears, having adjusted to the cold but not yet aching from it, I was as close to the experience of a sensory-deprivation tank as I ever wanted to get.

With no distractions, this seemed like an ideal moment to walk my memory through the red-tide dream in search of meaningful details that had not initially registered with me. I would have been relieved to recall a neon sign that provided the month, day, and hour of the cataclysm, the precise location, and a description of the event.

Unfortunately, my predictive dreams don’t work that way. I do not understand why I have been given a prognostic gift vivid enough to make me feel morally obliged to prevent a foreseen evil—but not clear enough to allow me to act at once with force and conviction.

Because of the disturbing supernatural aspects of my life and because the weight of my unusual responsibilities outweighs my power to fulfill them, I risk being crushed by stress. Consequently, I have kept the nonsupernatural part of my life simple. As few possessions as possible. No obligations like a mortgage or a car payment to worry about. I avoid contemporary TV, contemporary politics, contemporary art: all too frantic, fevered, and frivolous, or else angry, bitter.

At times, even working as a fry cook in a busy restaurant became too complicated. I contemplated a less demanding life in tire sales or the retail shoe business. If someone would pay me to watch grass grow, I could handle that.

I have no clothes except T-shirts and jeans, and sweatshirts in cool weather. No wardrobe decisions to make.

I have no plans for the future. I make my life up as I go along.

The perfect pet for me is a ghost dog. He doesn’t need to be fed, watered, or groomed. No poop to pick up.

Anyway, drifting through fog toward the shrouded shore, I was at first unable to fish new details of the dream from memory. But then I realized that in the vision, Annamaria had not worn the clothes I had seen her wear in life.

She had been pregnant, as in life, suspended in the air above the luminous and crimson sea, a tempest of fiery clouds behind her.

As I stood on a beach crawling with snakes of light, she floated toward me, freed from the power of gravity, arms folded across her breast, eyes closed.

I recalled her garment fluttering, not as if billowing in the winds of a cataclysm, but as if stirred gently by her own magical and stately progress through the air.

Not a dress or gown. Voluminous but not absurdly so. A robe of some kind, covering her from throat to wrists, to ankles.

Her ankles had been crossed, her feet bare.

The fabric of the garment exhibited the softness and the sheen of silk, and it hung in graceful folds; yet there had been something strange about it.

Something extraordinary.

I was certain that it had been white at first. But then not white. I could not recall what color it had subsequently become, but the change of color hadn’t been the strange thing.

The softness of the weave, the sheen of the fabric. The graceful draping. The slightest flutter of the sleeves, and of the hem above the bare feet …

Scissors-kicking, the heels of my sneakered feet bumped something in the water, and an instant later my stroking hands met resistance. I flailed once at an imagined shark before I realized I had reached shallow water and that I was fighting only sand.

I rolled off my back, rose into night air colder than the water. Listening to the outboard engine fade in the distance, I waded ashore through whispering surf and a scrim of sea foam.

Out of the white fog, up from the white beach came a gray form, and suddenly a dazzling light bloomed three inches from my face.

Before I could reel backward, the flashlight swung up, one of those long-handled models. Before I was able to dodge, the flashlight arced down and clubbed me, a glancing blow to the side of my head.

As he hit me, he called me a rectum, although he used a less elegant synonym for that word.

The guy loomed so close that even in the confusing fog-refracted slashes of light, I could see that he was a new thug, not one of the three miscreants from the pier.

The motto of Magic Beach was EVERYONE A NEIGHBOR, EVERY NEIGHBOR A FRIEND. They needed to consider changing it to something like YOU BETTER WATCH YOUR ASS.

My ears were ringing and my head hurt, but I was not dazed. I lurched toward my assailant, and he backed up, and I reached for him, and he clubbed me again, this time harder and squarely on the top of the head.

I wanted to kick his crotch, but I discovered that I had fallen to my knees, which is a position from which crotch-kicking is a too-ambitious offense.

For a moment I thought the faithful were being summoned to church, but then I realized the bell was my skull, tolling loudly.

I didn’t have to be psychic to know the flashlight was coming down again, cleaving fog and air.

I said a bad word.

CHAPTER 7 (#ulink_c8613609-e5d2-5afb-a0ed-0c41294b99a8)

Considering that this is my fourth manuscript, I have become something of a writer, even though nothing that I have written will be published until after my death, if ever.

As a writer, I know how the right bad word at a crucial moment can purge ugly emotions and relieve emotional tension. As a guy who has been forced to struggle to survive almost as long as he has been alive, I also know that no word—even a really, really bad word—can prevent a blunt object from splitting your skull if it is swung with enthusiasm and makes contact.

So having been driven to my knees by the second blow, and with my skull ringing as though the hunchback of Notre Dame were inside my head and pulling maniacally on bell ropes, I said the bad word, but I also lunged forward as best I could and grabbed my assailant by the ankles.

The third blow missed its intended target, and I took the impact on my back, which felt better than a whack on the head, although not as good as any moment of a massage.

Facedown on the beach, gripping his ankles, I tried to pull the sonofabitch off his feet.

Sonofabitch wasn’t the bad word that I used previously. This was another one, and not as bad as the first.

His legs were planted wide, and he was strong.

Whether my eyes were open or closed, I saw spirals of twinkling lights, and “Somewhere over the Rainbow” played in my head. This led me to believe that I had nearly been knocked unconscious and that I didn’t have my usual strength.

He kept trying to hit my head again, but he also had to strive to stay upright, so he managed only to strike my shoulders three or four times.

Throughout this assault, the flashlight beam never faltered, but repeatedly slashed the fog, and I was impressed by the manufacturer’s durability standards.

Although we were in a deadly serious struggle, I could not help but see absurdity in the moment. A self-respecting thug ought to have a gun or at least a blackjack. He flailed at me as though he were an eighty-year-old lady with an umbrella responding to an octogenarian beau who had made a rude proposal.

At last I succeeded in toppling him. He dropped the flashlight and fell backward.

I clambered onto him, jamming my right knee where it would make him regret having been born a male.

Most likely he tried to say a bad word, a very bad word, but it came out as a squeal, like an expression of consternation by a cartoon mouse.

Near at hand lay the flashlight. As he tried to throw me off, I snared that formidable weapon.

I do not like violence. I do not wish to be the recipient of violence, and I am loath to perpetrate it.

Nevertheless, I perpetrated a little violence on the beach that night. Three times I hit his head with the flashlight. Although I did not enjoy striking him, I didn’t feel the need to turn myself in to the police, either.

He stopped resisting and I stopped hitting. I could tell by the slow soft whistle of his breathing that he had fallen unconscious.

When all the tension went out of his muscles, I clambered off him and got to my feet just to prove to myself that I could do it.

Dorothy kept singing faintly, and I could hear Toto panting. The twinkling lights behind my eyelids began to spiral faster, as if the tornado was about to lift us out of Kansas and off to Oz.

I returned voluntarily to my knees before I went down against my will. After a moment, I realized that the panting was mine, not that of Dorothy’s dog.

Fortunately, my vertigo subsided before my adversary regained consciousness. Although the flashlight still worked, I didn’t think it could take much more punishment.

The cracked lens cast a thin jagged shadow on his face. But as I peeled back one of his eyelids to be sure that I had not given him a concussion, I could see him well enough to know that I had never seen him before and that I preferred never to see him again.

Eye of newt. Wool-of-bat hair. Nose of Turk and Tartar’s lips. A lolling tongue like a fillet of fenny snake. He was not exactly ugly, but he looked peculiar, as if he’d been conjured in a cauldron by Macbeth’s coven of witches.

When he had fallen, a slim cell phone had slid half out of his shirt pocket. If he was in league with the trio at the pier, he might have called them when he heard me swimming ashore.

After rolling him onto his side, I took the wallet from his hip pocket. Supposing he had summoned help moments before I had come ashore, I needed to move on quickly and could not pore through his ID there on the beach. I left his folding money in his shirt pocket with his cell phone, and I took the wallet.

I propped the flashlight on his chest. Because his head was raised on a mound of sand, the bright beam bathed him from chin to hairline.

If something like Godzilla woke in a Pacific abyss and decided to come ashore to flatten our picturesque community, this guy’s face would dissuade it from a rampage, and the scaly beast would return meekly to the peace of the deeps.

With the fog-diffused lights of town to guide me, I slogged across the wide beach.

I did not proceed directly east. Perhaps Flashlight Guy had told the pier crew that he was on the shore due west of some landmark, by which they could find him. If they were coming, I wanted to cut a wide swath around them.

CHAPTER 8 (#ulink_7bd13a0c-a44a-5416-b8c8-f7015bb609a0)

As I angled northeast across the strand, the soft sand sucked at my shoes and made every step a chore.

Wearing wet jeans and T-shirt on the central coast on a January night can test your mettle. Five weeks ago, however, I had been in the Sierra during a blizzard. This felt balmy by comparison.

I wanted a bottle of aspirin and an ice bag. When I touched the throbbing left side of my head, I wondered if I needed stitches. My hair felt sticky with blood. I found a lump the size of half a plum.

When I left the beach, I was at the north end of the shoreside commercial area, where Jacaranda Avenue dead-ended. From there, a mile of oceanfront houses faced the concrete boardwalk all the way to the harbor.

For its ten-block length, Jacaranda Avenue, which ran east from the boardwalk, was lined with ancient podocarpuses. The trees formed a canopy that cooled the street all day and shaded the streetlamps at night. Not one jacaranda grew along its namesake avenue.

Wisteria Lane boasted no wisteria. Palm Drive featured oaks and ficuses. Sterling Heights was the poorest neighborhood, and of all the streets in town, Ocean Avenue lay the farthest from the ocean.

Like most politicians, those in Magic Beach seemed to live in an alternate universe from the one in which real people existed.

Wet, rumpled, my shoes and jeans caked with sand, bleeding, and no doubt wild-eyed, I was grateful that the podocarpuses filtered the lamplight. In conspiracy with the fog, I traveled in shadows along Jacaranda Avenue and turned right on Pepper Tree Way.

Don’t ask.

Three guys were hunting me. With a population of fifteen thousand, Magic Beach was more than a wide place in the highway, but it did not offer a tide of humanity in which I could swim unnoticed.