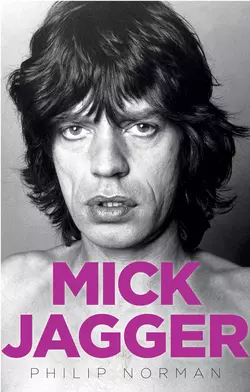

Mick Jagger

Philip Norman

A miracle of still-plentiful hair, raw sex-appeal, and strutting talent . The frontman of one of the most influential and controversial groups of all time. A musical genius with a career spanning over four decades. Mick Jagger is a testament at once to British glamour and sensual decline, the ultimate architect and demi-god of rock.Bestselling biographer Philip Norman offers an unparalleled account of the life of a living legend, Mick Jagger. From Home Counties schoolboy, to rebel without a cause to Sixties rock sensation and global idol, Norman unravels with astonishing intimacy the myth of the inimitable frontman of The Rolling Stones. MICK JAGGER charts his extraordinary journey through scandal-ridden conspiracy, infamous prison spell, hordes of female admirers and a knighthood while stripping away the colossal fame, wealth and idolatry to reveal a story of talent and promise unfulfilled.Understated yet ostentatious; the ultimate incarnation of modern man's favourite fantasy: 'sex, drugs and rock 'n' roll', yet blessed with taste and intelligence; a social chameleon who couldn't blend in if he tried; always moving with the Jagger swagger yet modest enough to be self-deprecating, Mick was a paradoxical energy that reconfigured the musical landscape.This revelatory tour de force is ample tribute to a flawed genius, a Casanova, an Antichrist and a god who, with characteristic nonchalance realised the dreams of thousands of current contenders and rocker pretenders, longevity, while coasting on a sea of fur rugs.

TO SUE, WITH LOVE

CONTENTS

Cover (#uf990933b-471c-5803-8e2d-19ba31dff337)

Title Page (#uce304b1c-2501-57e5-bde3-246e3bf91a84)

Dedication (#u1b6755a3-0b0e-5841-baf9-1649d30d2364)

Prologue: Sympathy for the Old Devil

PART I: ‘THE BLUES IS IN HIM’

ONE India-Rubber Boy

TWO The Kid in the Cardigan

THREE ‘Very Bright, Highly Motivated Layabouts’

FOUR ‘Self-Esteem? He Didn’t Have Any’

FIVE ‘“What a Cheeky Little Yob,” I Thought to Myself’

SIX ‘We Spent a Lot of Time Sitting in Bed, Doing Crosswords’

SEVEN ‘We Piss Anywhere, Man’

EIGHT Secrets of the Pop Stars’ Hideaway

NINE Elusive Butterfly

TEN ‘Mick Jagger and Fred Engels on Street Fighting’

PART II: THE TYRANNY OF COOL

ELEVEN ‘The Baby’s Dead, My Lady Said’

TWELVE Some Day My Prince Will Come

THIRTEEN The Balls of a Lion

FOURTEEN ‘As Lethal as Last Week’s Lettuce’

FIFTEEN Friendship with Benefits

SIXTEEN The Glamour Twins

SEVENTEEN ‘Old Wild Men, Waiting for Miracles’

EIGHTEEN Sweet Smell of Success

NINETEEN The Diary of a Nobody

TWENTY Wandering Spirit

TWENTY-ONE God Gave Me Everything

Postscript

Picture Section

List of Searchable Terms

Acknowledgements

Also by Philip Norman

Copyright

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE (#uf7997d5a-a073-50fc-b55b-2677213b6dcb)

Sympathy for the Old Devil (#uf7997d5a-a073-50fc-b55b-2677213b6dcb)

The British Academy of Film and Television Arts is not normally a controversial body, but in February 2009 it became the target of outraged tabloid headlines. To emcee its annual film awards – an event regarded as second only to Hollywood’s Oscars – BAFTA had chosen Jonathan Ross, the floppy-haired, foul-mouthed chat-show host who was currently the most notorious figure in UK broadcasting. A few weeks previously, Ross had used a peak-time BBC radio programme to leave a series of obscene messages on the answering machine of the former Fawlty Towers actor Andrew Sachs. As a result, he had been suspended from all his various BBC slots for three months while comedian Russell Brand, his fellow presenter and accomplice in the prank (who boasted on air about ‘shagging’ Sachs’s granddaughter) had bowed to pressure and left the corporation altogether. Since the 1990s, comedy in Britain has been known as ‘the new rock ’n’ roll’; now here were two of its principal ornaments positively straining a gut to be as naughty as old-school rock stars.

On awards night at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, a celebrity-packed audience including Brad Pitt, Angelina Jolie, Meryl Streep, Sir Ben Kingsley, Kevin Spacey and Kristin Scott-Thomas received two surprises outside the actual winners list. The first was that the bad language everyone had anticipated from Jonathan Ross came instead from Mickey Rourke on receiving the Best Actor award for The Wrestler. Tangle-haired, unshaven and barely coherent – since movie acting also lays urgent claim to being ‘the new rock ’n’ roll’ – Rourke thanked his director for this second chance ‘after fucking up my career for fifteen years’, and his publicist ‘for telling me where to go, what to do, when to do it, what to eat, how to dress, what to fuck . . .’

Having quipped that Rourke would pay the same penalty he himself had for ‘Sachsgate’ and be suspended for three months, Ross moderated his tone to one of fawning reverence. As presenter of the evening’s penultimate statuette, for Best Film, he called on ‘an actor and lead singer with one of the greatest rock bands in history’; somebody for whom this lofty red-and-gold-tiered auditorium ‘must seem like one of the smaller venues’ (and who, incidentally, could once have made the Sachsgate scandal look very small beer). Almost sacrilegiously, in this temple to pure acoustic Mozart, Wagner and Puccini, the sound system began chugging out the electric guitar intro to ‘Brown Sugar’, that 1971 rock anthem to drugs, slavery and interracial cunnilingus. Yes indeed, the award giver was Sir Mick Jagger.

Jagger’s entrance was no simple hop up to the podium but a lengthy red-carpet walk from the rear of the stage, to allow television viewers to drink in the full miracle. That still-plentiful hair, cut in youthful retro sixties mode, untainted by a single spark of grey. That understated couture suit, worn in deference to the occasion but also subtly emphasising the suppleness of the slight torso beneath and the springy, athletic step. Only the face betrayed the sixty-five-year-old, born at the height of the Second World War – the famous lips, once said to be able to ‘suck an egg out of a chicken’s arse’, now drawn in and bloodless; the cheeks etched by crevasses so wide and deep as to resemble terrible matching scars.

The ovation that greeted him belonged less to the Royal Opera House or the British Association for Film and Television Arts than to some giant open-air space like Wembley or Dodger Stadium. Despite all the proliferating genres of ‘new’ rock ’n’ roll, everyone knows there is only one genuine kind and that Mick Jagger remains its unrivalled incarnation. He responded with his disarming smile, a raucous ‘Allaw!’ and an impromptu flash of Rolling Stone subversiveness: ‘You see? You thought Jonathan would do all the “fuck”-ing, and Mickey did it . . .’

The voice then changed, the way it always does to suit the occasion. For decades, Jagger has spoken in the faux-Cockney accent known as ‘Mockney’ or ‘Estuary English’, whose misshapen, elongated vowels and obliterated t consonants are the badge of youthful cool in modern Britain. But here, amid the cream of English elocution, his diction of every t was bell clear, every h punctiliously aspirated as he said what an honour it was to be here tonightt, then went on to reveal ‘how it all came aboutt’.

A neat little joke followed, perfectly pitched between mockery and deference. He was here, he said, under ‘the RMEP – the Rock Stars–Movie Stars Exchange Programme . . . At this moment, “Sir” Ben Kingsley [giving the title ironic emphasis even though he shared it] will be singing “Brown Sugar” at the Grammys . . . “Sir” Anthony Hopkins is in the recording studio with Amy Winehouse . . . “Dame” Judi Dench is gamely trashing hotel rooms somewhere in the US . . . and we hope that next week “Sir” Brad and the Pitt family will be performing The Sound of Music at the Brit Awards.’ (Cut to Kevin Spacey and Meryl Streep laughing ecstatically and Angelina explaining the joke to Brad.)

Opening the envelope, he announced that the Best Film award went Danny Boyle’s Slumdog Millionaire – so very much what people used to consider him. But there was no doubt about the real winner. Jagger had scored his biggest hit since . . . oh . . . ‘Start Me Up’ in 1981. ‘It took a lot to out-glamour that place,’ one academician commented, ‘but he did it.’

Half a century ago, when the Rolling Stones ran neck and neck with the Beatles, one question above all used to be thrown at the young Mick Jagger in the eternal quest to get something enlightening, or even interesting, out of him: did he think he’d still be singing ‘Satisfaction’ when he was thirty?

In those innocent early sixties, pop music belonged exclusively to the young and was thought to be totally in thrall to youth’s fickleness. Even the most successful acts – even the Beatles – expected a few months at most at the top before being elbowed aside by new favourites. Back then, no one dreamed how many of those seemingly ephemeral songs would still be being played and replayed a lifetime hence or how many of those seemingly disposable singers and bands would still be plying their trade as old-age pensioners, greeted with the same fanatical devotion for as long as they could totter back onstage.

In the longevity stakes, the Stones leave all competition far behind. The Beatles lasted barely three years as an international live attraction and only nine in total (if you discount the two they spent acrimoniously breaking up). Other bands from the sixties’ top drawer like Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd and the Who, if not fractured by alcohol or drugs, drifted apart over time, then re-formed, their terminal boredom with their old repertoire, and one another, mitigated by the huge rewards on offer. Only the Stones, once seemingly the most unstable of all, have kept rolling continuously from decade to decade, then century to century; weathering the sensational death of one member and the embittered resignations of two others (plus ongoing internal politics that would impress the Medicis); leaving behind generations of wives and lovers; outlasting two managers, nine British prime ministers and the same number of American presidents; impervious to changing musical fads, gender politics and social mores; as sexagenarians still somehow retaining the same sulphurous whiff of sin and rebellion they had in their twenties. The Beatles have eternal charm; the Stones have eternal edge.

Over the decades since their joint heyday, of course, pop music’s essentials have hardly changed. Each new generation of musicians hits on the same chords in the same order and adopts the same language of love, lust and loss; each new generation of fans seeks the same kind of male idol with the same kind of sex appeal, the same repertoire of gestures, attitudes and manifestations of cool.

The notion of a rock ‘band’ – young ensemble musicians enjoying fame, wealth and sexual opportunity undreamed of by their historic counterparts in military regiments or northern colliery towns – was well established by the time the Stones got going, and has not changed one iota since. It remains as true that, even though the pop industry mostly is about illusion, exploitation and hype, true talent will always out, and always endure. From the Stones’ great rabble-rousing hits like ‘Jumpin’ Jack Flash’ or ‘Street Fighting Man’ to obscure early tracks like ‘Off the Hook’ or ‘Play with Fire’, and the R&B cover versions that came before, their music sounds as fresh as if recorded yesterday.

They remain role models for every band that makes it – the pampered boy potentates, lolling ungraciously on a couch as flashbulbs detonate, the same old questions are shouted by reporters, and the same facetious answers thrown back. The kind of tour they created in the late sixties is what everyone still wants: the private jets, the limos, the entourages, the groupies, the trashed hotel suites. All the well-documented evidence of how soul-destroyingly monotonous it soon becomes, all Christopher Guest’s brilliant send-up of a boneheaded travelling supergroup in This Is Spinal Tap, cannot destroy the mystique of ‘going on the road’, the eternal allure of ‘sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll’. Yet try as these youthful disciples may, they could never reproduce the swath which the on-road Stones cut through the more innocent world of forty-odd years ago, or touch remotely comparable levels of arrogance, self-indulgence, hysteria, paranoia, violence, vandalism and wicked joy.

Above all Mick Jagger, at any age, is inimitable. Jagger it was who, more than anyone, invented the concept of the ‘rock star’ as opposed to mere singer within a band – the figure set apart from his fellow musicians (a major innovation in those days of unified Beatles, Hollies, Searchers et al.) who could first unleash, then invade and control the myriad fantasies of enormous crowds. Keith Richards, Jagger’s co-figurehead in the Stones, is a uniquely talented guitarist, as well as the rock world’s most unlikely survivor, but Keith belongs in a troubadour tradition stretching back to Blind Lemon Jefferson and Django Reinhardt, continuing on to Eric Clapton, Jimi Hendrix, Bruce Springsteen, Noel Gallagher and Pete Doherty. Jagger, on the other hand, founded a new species and gave it a language that could never be improved on. Among his rivals in rock showmanship, only Jim Morrison of the Doors found a different way to sing into a microphone, cradling it tenderly in both hands like a frightened baby bird rather than flourishing it, Jagger-style, like a phallus. Since the 1970s, many other gifted bands have emerged with vast international followings and indubitably charismatic front men – Freddie Mercury of Queen, Holly Johnson of Frankie Goes to Hollywood, Bono of U2, Michael Hutchence of INXS, Axl Rose of Guns N’ Roses. Distinctive on record they might be, but when they took the stage they had no choice but to follow in Jagger’s strutting footsteps.

His status as a sexual icon is comparable only to Rudolph ‘the Sheik’ Valentino, the silent cinema star who aroused 1920s women to palpitant dreams of being thrown across the saddle of a horse and carried off to a Bedouin tent in the desert. With Jagger, the aura was closer to great ballet dancers, like Nijinsky and Nureyev, whose seeming feyness was belied by their lustful eyeballing of the ballerinas and overstuffed, straining codpieces. The Stones were one of the first rock bands to have a logo and, even for the louche early seventies, it was daringly explicit – a livid-red cartoon of Jagger’s own mouth, the cushiony lips sagging open with familiar gracelessness, the tongue slavering out to slurp an invisible something which, very clearly, was not ice cream. This ‘lapping tongue’ still adorns all the Stones’ literature and merchandise, symbolic of who controls every department. To modern eyes, there could hardly be a cruder monument to old-fashioned male chauvinism – yet it finds its mark as surely as ever. The most liberated twenty-first-century females perk up at the sound of Jagger’s name while those he captivated in the twentieth still belong to him in every fibre. As I was beginning this book, I mentioned its subject to my neighbour at a dinner party, a seemingly dignified, self-possessed Englishwoman of mature years. Her response was to re-create the scene in When Harry Met Sally where Meg Ryan simulates orgasm in the middle of a crowded restaurant. ‘Mick Jagger? Oh . . . yes! Yes, YES, YES!’

Sexual icons are notoriously prone to fall short of their public image in private; look at Mae West, Marilyn Monroe or, for that matter, Elvis Presley. But in the oversexed world of rock, in the whole annals of show business, Jagger’s reputation as a modern Casanova is unequalled. It’s questionable whether even the greatest lotharios of centuries past found sexual partners in such prodigious number, or were so often saved the tiresome preliminaries of seduction. Certainly, none maintained his prowess, as Jagger has, through middle and then old age (Casanova was knackered by his mid-thirties). What Swift called ‘the rage of the groin’ is now known as sex addiction and can be cured by therapy, but Jagger has never shown any sign of considering it a problem.

Looking at that craggy countenance, one tries but fails to imagine the vast carnal banquet on which he has gorged, yet still not sated himself . . . the unending gallery of beautiful faces and bright, willing eyes . . . the innumerable chat-up lines, delivered and received . . . the countless brusque adjournments to beds, couches, heaped-up cushions, dressing room floors, shower stalls or limo back seats . . . the ever-changing voices, scents, skin tones and hair colour . . . the names instantly forgotten, if ever known in the first place . . . Old men are often revisited in dreams, or daydreams, by the women they have lusted after. For him, it would be like one of those old-style reviews of the Soviet army in Red Square. And at least one of the gorgeous foot soldiers is among his BAFTA audience tonight, seated not a million miles from Brad Pitt.

By rights, the scandals in which he starred during the 1960s should have been forgotten decades ago, cancelled out by the teeming peccadilloes of today’s pop stars, soccer players, supermodels and reality-TV stars. But the sixties have an indestructible fascination, most of all among those too young to remember them – the condition known to psychologists as ‘nostalgia without memory’. Jagger personifies that ‘swinging’ era for Britain’s youth, both its freedom and hedonism and the backlash it finally provoked. Even quite young people today have heard of his 1967 drug bust, or at least of the Mars bar which figured so lewdly in it. Few realise the extent of the British establishment’s vindictiveness during that so-called Summer of Love; how tonight’s witty, well-spoken knight of the realm was reviled like a long-haired Antichrist, led to court in handcuffs, subjected to a show trial of almost medieval grotesquerie, then thrown into prison.

He is perhaps the ultimate example of that well-loved show-business stereotype, the ‘survivor’. But while most rock ’n’ roll survivors end up as bulgy old farts in grey ponytails, he is unchanged – other than facially – from the day he first took the stage. While most others have long since addled their wits with drugs or alcohol, his faculties are all intact, not least his celebrated instinct for what is fashionable, cool and posh. While others whinge about the money they lost or were cheated out of, he leads the biggest-earning band in history, its own survival achieved solely by his determination and astuteness. Without Mick, the Stones would have been over by 1968; from a gang of scruffball outsiders, he turned them into a British national treasure as legitimate as Shakespeare or the White Cliffs of Dover.

Yet behind all the idolatry, wealth and superabundant satisfaction is a story of talent and promise consistently, almost stubbornly, unfulfilled. Among all his contemporaries endowed with half a brain, only John Lennon had as many opportunities to move beyond the confines of pop. Though undeniably an actor, as Jonathan Ross introduced him to BAFTA, with both film and TV roles to his credit, Jagger could have developed a parallel screen career as successful as Presley’s or Sinatra’s, perhaps even more so. He could have used his sway over audiences to become a politician, perhaps a leader, such as the world had never seen – and still has not. He could have extended the (often overlooked) brilliance of his best song lyrics into poetry or prose, as Bob Dylan and Paul McCartney have done. At the very least, he could have become a first-echelon performer in his own right instead of merely fronting a band. But, somehow or other, none of it came to pass. His film-acting career stalled in 1970 and never restarted in any significant way, despite the literally dozens of juicy screen roles he was offered. He did no more than toy with the idea of politics and has never shown any signs of wanting to be a serious writer. As for going solo, he waited until the mid-eighties to make his move, creating such ill-feeling among the other Stones, especially Keith, that he had to choose between continuing or seeing the band implode. As a consequence, he is still only their front man, doing the same job he was at eighteen.

There is also the puzzle of how someone who fascinates so many millions, and is so clearly super-intelligent and perceptive, manages to make himself so very unfascinating when he opens those celebrated lips to speak. Even since the media first began pursuing Jagger, his on-the-record utterances have had the kind of non-committal blandness associated with British royalty. Look into any of the numerous ‘Rolling Stones in their own words’ compilations published in the past four decades and you’ll find Mick’s always the fewest and most anodyne. In 1983, he signed a contract with the British publishers Weidenfeld & Nicolson to write his autobiography for the then astounding sum £1 million. It should have been the show-business memoir of the century; instead, the ghostwritten manuscript was pronounced irremediably dull by the publishers and the entire advance had to be returned.

His explanation was that he ‘couldn’t remember anything’, by which of course he didn’t mean his birthplace or his mother’s name but the later personal stuff for which Weidenfeld had stumped up £1 million and any publisher today would happily pay five times as much. That has been his position ever since, when approached to do another book or pressed by interviewers for chapter and verse. Sorry, his phenomenal past is all just ‘a blur’.

This image of a man whose recall disappeared thirty years ago like some early-onset Alzheimer’s victim’s is pure nonsense, as anyone who knows him can attest. It’s a handy way of getting out of things – something he has always had down to a fine art. It gets him out of months boringly closeted with a ghostwriter, or answering awkward questions about his sex life. But the same blackboard-wipe obliterates career highs and lows unmatched by anyone else in his profession. How is it possible to ‘forget’, say, meeting Andrew Loog Oldham or living with Marianne Faithfull or refusing to ride on the London Palladium’s revolving stage or getting banged up in Brixton Prison or featuring in Cecil Beaton’s diaries or being spat at on the New York streets or inspiring a London Times editorial or ditching Allen Klein or standing up to homicidal Hell’s Angels at the Altamont festival or getting married in front of the world’s massed media in Saint-Tropez or being fingerprinted in Rhode Island or making Steven Spielberg fall on his knees in adulation or having Andy Warhol as a child-minder or being stalked by naked women with green pubic hair in Montauk or persuading a quarter of a million people in Hyde Park to shut up and listen to a poem by Shelley?

Such is the enduring paradox of Mick: a supreme achiever to whom his own colossal achievements seem to mean nothing, a supreme extrovert who prefers discretion, a supreme egotist who dislikes talking about himself. Charlie Watts, the Stones’ drummer, and the one least affected by all the madness, put it best: ‘Mick doesn’t care what happened yesterday. All he ever cares about is tomorrow.’

So let’s flick through those yesterdays in hopes of refreshing his memory.

PART I (#uf7997d5a-a073-50fc-b55b-2677213b6dcb)

‘THE BLUES IS IN HIM’ (#uf7997d5a-a073-50fc-b55b-2677213b6dcb)

CHAPTER ONE (#uf7997d5a-a073-50fc-b55b-2677213b6dcb)

India-Rubber Boy (#uf7997d5a-a073-50fc-b55b-2677213b6dcb)

To become what we call ‘a star’, it is not enough to possess unique talent in one or another of the performing arts; you also seemingly need a void inside you as fathomlessly dark as starlight is brilliant.

Normal, happy, well-rounded people do not as a rule turn into stars. It is something which far more commonly befalls those who have suffered some traumatic misery or deprivation in early life. Hence the ferocity of their drive to achieve wealth and status at any cost, and their insatiable need for the public’s love and attention. While awarding them a status near to gods, we also paradoxically view them as the most fallible of human beings, tortured by past demons and present insecurities, all too often fated to destroy their talent and then themselves with drink or drugs or both. Since the mid-twentieth century, when celebrity became global, the shiniest stars, from Charlie Chaplin, Judy Garland, Marilyn Monroe and Edith Piaf to Elvis Presley, John Lennon, Michael Jackson and Amy Winehouse, have fulfilled some if not all of these criteria. How, then, to account for Mick Jagger, who fulfils none of them?

Jagger bucked the trend with his very first breath. We expect stars to be born in unpromising locales that make their later rise seem all the more spectacular . . . a dirt-poor cabin in Mississippi . . . a raffish seaport . . . the dressing room of a seedy vaudeville theatre . . . a Parisian slum. We do not expect them to be born in thoroughly comfortable but unstimulating circumstances in the English county of Kent.

Southern England has always been the wealthiest, most privileged part of the country, but clustered around London is a special little clique of shires known rather snootily as ‘the Home Counties’. Kent is the most easterly of these, bounded in the north by the Thames Estuary, in the south by Dover’s sacred white cliffs and the English Channel. And, rather like its most famous twentieth-century son, it has multiple personalities. For some, this is ‘the Garden of England’ with its rolling green heart known as the Weald, its apple and cherry orchards and hop fields, and its conical redbrick hop-drying kilns or oast houses. For others, it conjures up the glory of Canterbury Cathedral, where ‘turbulent priest’ Thomas à Becket met his end, or stately homes like Knole and Sissinghurst, or faded Victorian seaside resorts like Margate and Broadstairs. For others, it suggests county cricket, Charles Dickens’s Pickwick Papers, or ultra-respectable Royal Tunbridge Wells, whose residents are so famously addicted to writing to newspapers that the nom de plume ‘Disgusted, Tunbridge Wells’ has become shorthand for any choleric elderly Briton fulminating against modern morals or manners. (‘Disgusted, Tunbridge Wells’ will play no small part in the story that follows.)

In the two thousand years since Julius Caesar’s Roman legions waded ashore on Walmer Beach, Kent has mainly been a place that people pass through – Chaucer’s pilgrims ‘from every shire’s ende’ trudging towards Canterbury, armies bound for European wars, present-day traffic to and from the Channel ports of Dover and Folkestone and the Chunnel. As a result, the true heart of the county is difficult to place. There certainly is a distinctive Kentish burr, subtly different from that of neighbouring Sussex, varying from town to town, even village to village, but the predominant accent is dictated by the metropolis that blends seamlessly into its northern margins. The earliest linguistic colonisers were the trainloads of East End Cockneys who arrived each summer to help bring in the hop harvest; since then, proliferating ‘dormitory towns’ for city office workers have made London-speak ubiquitous.

Jagger is neither a Kentish name nor a London one – despite the City lawyer named Jaggers in Dickens’s Great Expectations – but originated some two hundred miles to the north, around Halifax in Yorkshire. Although its most famous bearer (in his ‘Street Fighting Man’ period) would relish the similarity to jagged, claiming that it once meant ‘knifer’ or ‘footpad’, it actually derives from the Old English jag for a ‘pack’ or ‘load’, and denotes a carter, peddler or hawker. Pre-Mick, it adorned only one minor celebrity, the Victorian engineer Joseph Hobson Jagger, who devised a successful system for winning at roulette and may partly have inspired a famous music-hall song, ‘The Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo’. The family could thus claim a precedent for hitting the jackpot.

No such mercenary aims possessed Mick’s father, Basil Fanshawe Jagger – always known as Joe – who was born in 1913 and raised in an atmosphere of clean-living altruism. Joe’s Yorkshireman father, David, was a village school headmaster in days when all the pupils would share a single room, sitting on long wooden forms and writing on slates with chalk. Despite a small, slender build, Joe proved a natural athlete, equally good at all track-and-field sports, with a special flair for gymnastics. Given his background and idealistic, unselfish temperament, it was natural he should choose a career in what was then known as PT – physical training. He studied at Manchester and London universities and, in 1938, was appointed PT instructor at the state-run East Central School in Dartford, Kent.

Situated in the far north-west of the county, Dartford is practically an east London suburb, barely thirty minutes by train from the great metropolitan termini of Victoria and Charing Cross. It lies in the valley of the River Darent, on the old pilgrims’ way to Canterbury, and is known to history as the place where Wat Tyler started the Peasants’ Revolt against King Richard II’s poll tax in 1381 (so rabble-rousers in the blood, then). In modern times, almost its only invocation – albeit hundreds of times each day – is in radio traffic reports for the Dartford Tunnel, under the Thames, and adjacent Dartford–Thurrock Crossing, the main escape route from London for south-coast-bound traffic. Otherwise it is just a name on a road sign or station platform, its centuries as a market and brewing town all but obliterated by office blocks, multiple stores and even more multiple commuter homes. From the closing years of Queen Victoria’s reign, traffic funnelled to Dartford was not only vehicular; an outlying village with the serendipitous name of Stone contained a forbidding pile known as the East London Lunatic Asylum until a more tactful era renamed it ‘Stone House’.

Early in 1940, Joe Jagger met Eva Ensley Scutts, a twenty-seven-year-old as vivacious and demonstrative as he was understated and quiet. Eva’s family originally came from Greenhithe, Kent, but had emigrated to New South Wales, Australia, where she was born in the same year as Joe, 1913. Towards the end of the Great War, her mother left her father and brought her and four siblings home to settle in Dartford. Eva was always said to be a little ashamed of her birth ‘Down Under’ and to have assumed an exaggeratedly upper-class accent to hide any lingering Aussie twang. The truth was that in those days all respectable young girls tried to talk like London débutantes and the royal princesses Elizabeth and Margaret. Eva’s work as an office secretary, and later a beautician, made it a professional necessity.

Joe’s courtship of Eva took place during the Second World War’s grim first act, when Britain stood alone against Hitler’s all-conquering armies in France and the Führer could be seen gazing across the Channel towards the White Cliffs of Dover as smugly as if he owned them already. With summer came the Battle of Britain, scrawling the sunny Kentish skies with white vapour-trail graffiti as British and German fighters duelled above the cornfields and oast houses and gentle green Weald. Though Dartford possessed no vital military installations, it received a constant overspill from Luftwaffe raids on factories and docks in nearby Chatham and Rochester and on London’s East End. The fact that many falling bombs were not aimed at Dartford, but jettisoned by German planes heading home, made the toll no less horrendous. One killed thirteen people in the town’s Kent Road; another hit the county hospital, wiping out two crowded women’s wards.

Joe and Eva were married on 7 December 1940 at Holy Trinity Church, Dartford, where Eva had sung in the choir. She wore a dress of lavender silk rather than traditional bridal white, and Joe’s brother, Albert, acted as best man. Afterwards there was a reception at the nearby Coneybeare Hall. This being wartime – and Joe wholeheartedly committed to the prevailing ethos of frugality and self-sacrifice – only fifty guests attended, drinking to the newlyweds’ health in brown sherry and munching dainty sandwiches of Spam or powdered egg.

Joe’s teaching job and work in resettling London evacuee children exempted him from military call-up, so at least there was no traumatic parting as he was sent overseas or to the opposite end of the country. Nor, conversely, was there the urgency to start a family felt by many service people briefly home on leave. Joe and Eva’s first child did not arrive until 1943, when they were both aged thirty. The delivery took place at Dartford’s Livingstone Hospital on 26 July, the birthday of George Bernard Shaw, Carl Jung and Aldous Huxley, and the baby boy was christened Michael Philip. As a possibly more significant omen, the town’s State Cinema that week was showing an Abbott and Costello film entitled Money for Jam.

His babyhood saw the war gradually turn in the Allies’ favour and Britain fill with American soldiers – a glamorous breed, provided with luxuries the British had almost forgotten, and playing their own infectious dance music – preparatory to the reconquest of Fortress Europe. Defeated though Nazism was, it possessed one last ‘vengeance weapon’ in the pilotless V-1 flying bombs or doodlebugs, launched from France, that inflicted heavy damage and loss of life on London and its environs during the war’s final months. Like everyone in the Dartford area, Joe and Eva spent many tense nights listening for the whine of the V-1’s motor that cut out just before it struck its target. Later, and even more terrifyingly, came the V-2, a jet-propelled bomb that travelled faster than the speed of sound and so gave no warning of its approach.

Michael Philip, of course, remained blissfully unaware as a bombed, battered and stringently rationed nation realised with astonishment that it had not only survived but prevailed. One of his earliest memories is watching his mother remove the heavy blackout curtains from the windows in 1945, signifying no more nighttime fear of air raids.

By the time his younger brother, Christopher, arrived in 1947, the family was living at number 39 Denver Road, a crescent of white pebble-dashed houses in Dartford’s genteel western quarter. Joe had exchanged day-to-day PT teaching for an administrative job with the Central Council of Physical Recreation, the body overseeing all amateur sports associations throughout Britain. Accomplished track-and-field all-rounder though he still was, his special passion was basketball, a seemingly quintessential American sport that nonetheless had been played in the UK since the 1890s. To Joe, no game was better at fostering the sportsmanship and team spirit to which he was dedicated. He devoted many unpaid hours to encouraging and coaching would-be local teams, and in 1948 launched the first Kent County Basketball League.

Tolstoy observes at the beginning of Anna Karenina that, whereas unhappy families are miserable in highly original and varied ways, happy families tend to be almost boringly alike. Our star, the future symbol of rebellion and iconoclasm, grew up in just such fortunate conformity. His quiet, physically dynamic father and ebullient, socially aspirational mother were a thoroughly compatible couple, devoted to each other and their children. In contrast with many postwar homes, the atmosphere at 39 Denver Road was one of complete security, with meals, bath- and bedtimes at prescribed hours, and values in their correct order. Joe’s modest stipend and personal abstinence – he neither drank nor smoked – were enough to keep a wife and two boys in relative affluence as wartime rationing gradually disappeared and meat, butter, sugar and fresh fruit became plentiful once more.

There is an idealised image of a little British boy in the early 1950s, before television, computer games and too-early sexualisation did away with childhood innocence. He is dressed, not like a miniature New York street-gangster or jungle guerrilla but unequivocally as a boy – porous white Aertex short-sleeved shirt, baggy khaki shorts, an elasticised belt fastening with an S-shaped metal clasp. He has tousled hair, a broad, breezy smile and eyes unclouded by fear or premature sexuality, squinted against the sun. He is Mike Jagger, as the world then knew him, aged about seven, photographed with a group of classmates at his first school, Maypole Infants. The name could not be more atmospheric in its suggestion of springtime and kindly fun, of pure-hearted lads and lasses dancing round a beribboned pole to welcome the darling buds.

At Maypole he was a star pupil, top of the class or near it in every subject. As was soon evident, he possessed his father’s all-round aptitude for sports, dominating the school’s miniature games of soccer and cricket and its egg-and-spoon or sack-racing athletics. One of his teachers, Ken Llewellyn, would remember him as the most engaging as well as brightest boy in his year, ‘an irrepressible bundle of energy’ whom it was ‘a pleasure to teach’. In this seven-year-old paragon, however, there was already a touch of the subversive. He had a sharp ear for the way that grown-ups talked, and could mould his voice into an impressive range of accents. His imitations of teachers like the Welsh Mr Llewellyn went down even better with classmates than his triumphs on the games field.

At the age of eight he moved on to Wentworth County Primary, a more serious place, not so much about maypole dancing as surviving in the playground. Here he met a boy born at Livingstone Hospital like himself but five months later; an ill-favoured little fellow with the protruding ears and hollow cheeks of some Dickensian workhouse waif, though he came from a good enough home. His name was Keith Richards.

For British eight-year-olds in this era, the chief fantasy figures were American cowboy movie heroes like Gene Autry and Hopalong Cassidy, whose Western raiment was flashingly gorgeous, and who would periodically sheathe their pearl-handled six-shooters and warble ballads to their own guitar accompaniment. In the Wentworth playground one day, Keith confided to Mike Jagger that when he grew up he wanted to be like Roy Rogers, the self-styled ‘King of the Cowboys’, and play a guitar.

Mike was indifferent to the King of the Cowboys – he was already good at being indifferent – but the idea of the guitar, and of this little imp with sticky-out ears strumming one, did pique his interest. However, their acquaintanceship did not ripen: it would be more than a decade before they explored the subject further.

At the Jaggers’, like every other British household, music was constantly in the air, pumped out of bulky valve-operated radio sets by the BBC’s Light Programme in every form from dance bands to operetta. Mike enjoyed mimicking American crooners he heard – like Johnnie Ray blubbing through ‘Just Walkin’ in the Rain’ and ‘The Little White Cloud That Cried’ – but did not attract any special notice in school singing lessons or in the church choir to which he and his brother Chris both belonged. Chris, at that stage, seemed more of a natural performer, having won a prize at Maypole Infants School for singing ‘The Deadwood Stage’ from the film Calamity Jane. The musical entertainments that appealed most to Mike were the professional Christmas pantomimes staged at larger theatres in the area – corny shows based on fairy tales like Mother Goose or ‘Jack and the Beanstalk’, but with an intriguing whiff of sex and gender blurring, the rouged and wisecracking ‘dame’ traditionally played by a man, the ‘principal boy’ by a leggy young woman.

In 1954, the family moved from 39 Denver Road and out of Dartford entirely, to the nearby village of Wilmington. Their house now had a name, ‘Newlands’, and stood in a secluded thoroughfare called The Close, a term usually applied to cathedral precincts. There was a spacious garden where Joe could give his two sons regular PT sessions and practise the diverse sports in which he was coaching them. The neighbours grew accustomed to seeing the grass littered with balls, cricket stumps, and lifting weights, and Mike and Chris swinging like titchy Tarzans from ropes their father had tied to the trees.

For the Jaggers, as for most British families, it was a decade of steadily increasing prosperity, when luxuries barely imaginable before the war became commonplace in almost every home. They acquired a television set, whose minuscule screen showed a bluish rather than black-and-white picture, allowing Mike and Chris to watch Children’s Hour puppets like Muffin the Mule, Mr Turnip and Sooty, and serials like Frances Hodgson Burnett’s Secret Garden and E. Nesbit’s The Railway Children. They took summer holidays in sunny Spain and the South of France rather than Kent’s own numerous, cold-comfort resorts like Margate and Broadstairs. But the boys were never spoiled. Joe in his quiet way was a strict disciplinarian and Eva was equally forceful, particularly over cleanliness and tidiness. From their youngest years, Mike and Chris were expected to do their share of household chores, set out in a school-like timetable.

Mike pulled his weight without complaint. ‘[He] wasn’t a rebellious child at all,’ Joe would later remember. ‘He was a very pleasant boy at home in the family, and he helped to look after his younger brother.’ Indeed, the only shadow on his horizon was that Chris seemed to be his mother’s favourite and he himself never received quite the same level of affection and attention from her. It made him slow to give affection in his turn – a lifelong trait – and also self-conscious and shy in front of strangers, and mortified with embarrassment when Eva pushed him forward to say ‘hello’ or shake hands.

The year of the family’s move to Wilmington, he sat the Eleven Plus, the exam with which British state education pre-emptively sorted its eleven-year-olds into successes and failures. The bright ones went on to grammar schools, often the equal of any exclusive, fee-paying institutions, while the less bright went to secondary-moderns and the dullards to ‘technical schools’ in hope of at least acquiring some useful manual trade. For Mike Jagger, there was no risk of either of these latter options. He passed the exam easily and in September 1954 started at Dartford Grammar School on the town’s West Hill.

His father could not have been better pleased. Founded in the eighteenth century, Dartford Grammar was the best school of its kind in the district, aspiring to the same standards and observing the same traditions that cost other parents dear at establishments like Eton and Harrow. It had a coat of arms and a Latin motto, Ora et Labora (Pray and Work); it had ‘masters’ rather than mere teachers, clad in scholastic black gowns; most important for Joe, it placed as much emphasis on sports and physical development as on academic achievement. Its alumni included the Indian Mutiny hero Sir Henry Havelock, and the great novelist Thomas Hardy, originally an architect, had worked on one of its nineteenth-century extensions.

In these new surroundings, however, Mike did not shine nearly as brightly as before. His Eleven Plus results had put him into the ‘A’ stream of specially promising pupils, headed for good all-round results in the GCE O-level exams, followed by two years in the sixth form and probable university entrance. He was naturally good at English, had something of a passion for history (thanks to an inspirational teacher named Walter Wilkinson), and spoke French with an accent superior to most of his classmates’. But science subjects, like maths, physics and chemistry, bored him, and he made little or no effort with them. In the form order, calculated on aggregate marks, he usually figured about half way. ‘I wasn’t a swot and I wasn’t a dunce,’ he would recall of himself. ‘I was always in the middle ground.’

At sports, despite his father’s comprehensive coaching, he was equally inconsistent. Summer was no problem, as Dartford Grammar played cricket, something he loved to watch as well as play, and under Joe’s coaching he could shine in athletics, especially middle-distance running and javelin. But the school’s winter team game was upper-class rugby football rather than proletarian soccer. Fast runner and good catcher that Mike was, he easily made every school rugger side up to the First Fifteen. But he hated being tackled – which often meant crashing onto his face in squelching mud – and would do everything he could to avoid receiving a pass.

The headmaster, Ronald Loftus Hudson, sarcastically known as ‘Lofty’, was a tiny man who nonetheless could reduce the rowdiest assembly to pin-drop silence with little more than a raised eyebrow. Under his regime there were myriad petty regulations about dress and conduct, the sternest relating to the fully segregated but tantalisingly near-at-hand Dartford Grammar School for Girls. Boys were forbidden to talk to the girls, even if they happened to meet out of school hours at places like bus stops. The head also used corporal punishment, as most British educators then did, without legal restraint or fear of parental protest – between two and six strokes on the backside with a stick or gym shoe. ‘You had to wait outside [his] study until the light went on, and then you’d go in,’ the Jagger of the future would remember. ‘And everybody else used to hang about on the stairs to see how many he gave and how bad it was that morning.’

All the male teachers could administer formal beatings in front of the whole class and most, in addition, practised a casual, even jocular physical violence that today would instantly land them in court for assault. Any who showed weakness (like the English teacher, ‘sweet, gentle Mr Brandon’) were mercilessly ragged and aped by Jagger, the class mimic, behind their backs or to their faces. ‘There were guerrilla skirmishes on all fronts, with civil disobedience and undeclared war; [the teachers] threw blackboard rubbers at us and we threw them back,’ he would recall. ‘There were some who’d just punch you out. They’d slap your face so hard, you’d go down. Others would twist your ear and drag you along until it was red and stinging.’ So that line from ‘Jumpin’ Jack Flash’, ‘I was schooled with a strap right across my back,’ may not be as fanciful as it has always seemed.

At number 23 The Close lived a boy named Alan Etherington, who was the same age as Mike and also went to Dartford Grammar. The two quickly chummed up, biking to school together each morning and going to tea at each other’s house. ‘There was a standing joke with us that if Mike appeared, he was trying to get out of chores his parents had given him, like washing up or mowing the lawn,’ Etherington remembers. House-proud Eva could be a little intimidating, but Joe, despite his ‘quiet authority’, created an atmosphere of healthy fun. When Etherington dropped by, there would usually be a pick-up game of cricket or rounders or an impromptu weight-training session on the lawn. Sometimes, as a special treat, Joe would produce a javelin, take the boys to the open green space at the top of The Close, and under his careful supervision allow them to practise a few throws.

Having a father so closely connected to the teaching world meant that Mike’s daily release from school was not as complete as other boys’. Joe knew several of the staff at Dartford Grammar, and so could keep close watch on both his academic performance and his conduct. There also could be no shirking of homework: he would later remember getting up at 6 A.M. to finish some essay or exercise, having fallen asleep over his books the night before. But in other ways Joe’s links with the school were an advantage. Arthur Page, the sports master – and a celebrated local cricketer – was a family friend who gave Mike special attention in batting practice at the school nets. Likewise as a favour to his father, one of the mathematics staff agreed to help him with his weakest subject even though he wasn’t in the teacher’s usual set.

Eventually, Joe himself became a part-time instructor at Dartford Grammar, coming in each Tuesday evening to give coaching in his beloved basketball. And there was one game, at least, where Mike’s enthusiasm, and application, fully matched his father’s. In basketball one could run and weave and catch and shoot with no risk of being pushed into mud; best of all, despite Joe’s patient exposition of its long British history, it felt glamorously and exotically American. Its most famous exponents were the all-black Harlem Globetrotters, whose displays of almost magical ball control, to the whistled strains of ‘Sweet Georgia Brown’, gave Mike Jagger and countless other British boys their earliest inklings of ‘cool’. He became secretary of the school basketball society that evolved from Joe’s visits, and never missed a session. While his friends played in ordinary gym shoes, he had proper black-and-white canvas basketball boots, which not only enhanced performance on the court but were stunningly chic juvenile footwear off it.

Otherwise, he was an inconspicuous member of the school community, winning neither special distinction nor special censure, offering no challenge to the status quo, using his considerable wits to avoid trouble with chalk-throwing, ear-twisting masters rather than provoke it. His school friend John Spinks remembers him as ‘an India-rubber character’ who could ‘bend every way to stay out of trouble’.

By mid-1950s standards, he was not considered good-looking. Sex appeal then was entirely dictated by film stars, of whom the male archetypes were tall, keen-jawed and muscular, with close-cut, glossy hair – American action heroes such as John Wayne and Rock Hudson; British ‘officer types’ such as Jack Hawkins and Richard Todd. Mike, like his father, was slightly built and skinny enough for his rib cage to protrude, though unlike Joe he showed no sign of incipient baldness. His hair, formerly a reddish colour, was now mousy brown and already floppily unmanageable.

His most noticeable feature was a mouth which, like certain breeds of bull-baiting terriers, seemed to occupy the entire lower half of his face, making a smile literally stretching from ear to ear, and Cupid’s-bow lips of unusual thickness and colour that seemed to need double the usual amount of moistening by his tongue. His mother also had markedly full lips – kept in top condition by the amount she talked – but Joe was convinced that Mike’s came from the Jagger side of the family and would sometimes apologise, not altogether jokingly, for having passed them on to him.

As the boys in his year reached puberty (yes, in 1950s Britain it really was this late) and all at once became agonisingly conscious of their clothes, grooming and appeal to the opposite sex, small, scrawny, loose-mouthed Mike Jagger seemed to have rather little going for him. Yet in encounters with the forbidden girls’ grammar school he somehow always provoked the most smiles, blushes, giggles and whispered discussions behind his back. ‘Almost from the time I met Mike, he always had girls flocking around him,’ Alan Etherington remembers. ‘A lot of our friends seemed to be much better looking, but they never had anything like the success that he did. Wherever he was, whatever he was doing, he knew he never needed to be alone.’

At the same time, his maturing looks, especially the lips, could arouse strange antagonism in males; teasing and taunting from classmates, sometimes even physical bullying by older boys. Not for being effeminate – his prowess on the sports field automatically discounted that – but for something far more damning. This was a time when unreformed nineteenth-century racism, the so-called colour bar, held sway in even Britain’s most civilised and liberal circles. To grammar school boys, as to their parents, thick lips suggested just one thing and there was just one term for it, repugnant now but back then quite normal.

Decades later, in a rare moment of self-revelation, he would admit that during his time at Dartford Grammar ‘the N-word’, for ‘nigger’, was thrown at him more than once. The time was still far off when he would find the comparison flattering.

THOUSANDS OF BRITISH men who grew up in the 1950s – and almost all who went on to dominate popular culture in the sixties – recall the arrival of rock ’n’ roll music from America as a life-changing moment. But such was not Mike Jagger’s experience. In rigidly class-bound postwar Britain, rock ’n’ roll’s impact was initially confined to young people of the lower social orders, the so-called Teddy Boys and Teddy Girls. During its earliest phase it made little impression on the bourgeoisie or the aristocracy, both of whose younger generations viewed it with almost as much distaste as did their parents. Likewise, in the hierarchical education system, it found its first enraptured audience in secondary modern and technical schools. At institutions like Dartford Grammar it was, rather, a subject for high-flown sixth-form debates: ‘Is rock ’n’ roll a symptom of declining morals in the twentieth century?’

Like Spanish influenza forty years previously, it struck in two stages, the second infinitely more virulent than the first. In 1955, a song called ‘Rock Around the Clock’ by Bill Haley and His Comets topped the sleepy British pop music charts and caused outbreaks of rioting in proletarian dance halls, but was plausibly written off by the national media as just another short-lived transatlantic novelty. A year later, Elvis Presley came along with a younger, more dangerous spin on Haley’s simple exuberance and the added ingredient of raw sex.

As a middle-class grammar school boy, Mike was just an onlooker in the media furore over Presley – the ‘suggestiveness’ of his onstage hip grinding and knee trembling, the length of his hair and sullen smoulder of his features, the (literally) incontinent hysteria to which he aroused his young female audiences. While adult America’s fear and loathing were almost on a par with the national Communist phobia, adult Britain reacted more with amusement and a dash of complacency. A figure like Presley, it was felt, could only emerge from the flashy, hyperactive land of Hollywood movies, Chicago gangsters and ballyhooing political conventions. Here in the immemorial home of understatement, irony and the stiff upper lip, a performer in any remotely similar mode was inconceivable.

The charge of blatant sexuality levelled against all rock ’n’ roll, not merely Presley, was manifestly absurd. Its direct ancestor was the blues – black America’s original pairing of voice with guitar – and the modern, electrified, up-tempo variant called rhythm and blues or R&B. The blues had never been inhibited about sex; rock and roll were separate synonyms for making love, employed in song lyrics and titles (‘Rock Me, Baby’, ‘Roll with Me, Henry’, etc.) for decades past, but heard only on segregated record labels and radio stations. Presley’s singing style and incendiary body movements were simply what he had observed on the stages and dance floors of black clubs in his native Memphis, Tennessee. Most rock ’n’ roll hits were cover versions of R&B standards by white vocalists, purged of their earthier sentiments or couched in slang so obscure (‘I’m like a one-eyed cat peepin’ in a seafood store’) that no one realised. Even this sanitised product took the smallest step out of line at its peril. When the white, God-fearing Pat Boone covered Fats Domino’s ‘Ain’t That a Shame’, he was criticised for disseminating what was seen as a contagiously vulgar ‘black’ speech idiom.

As a Dartford Grammar pupil, the appropriate music for Mike Jagger was jazz, in particular the modern kind with its melodic complexities, subdued volume and air of intellectualism. Even that played little part in daily school life, where the musical diet was limited to hymns at morning assembly and traditional airs like ‘Early One Morning’ or ‘Sweet Lass of Richmond Hill’ (the latter another pointer to Mike’s remarkable future). ‘There was a general feeling that music wasn’t important,’ he would recall. ‘Some of the masters rather begrudgingly enjoyed jazz, but they couldn’t own up to it . . . Jazz was intelligent and people who wore glasses played it, so we all had to make out that we dug Dave Brubeck. It was cool to like that, and it wasn’t cool to like rock ’n’ roll.’

This social barrier was breached by skiffle, a short-lived craze peculiar to Britain which nonetheless rivalled, even threatened to eclipse, rock ’n’ roll. Skiffle had originally been American folk (i.e., white) music, evolved in the Depression years of the 1930s; in this new form, however, it drew equally on blues giants of the same era, notably Huddie ‘Leadbelly’ Ledbetter. Leadbelly songs like ‘Rock Island Line’, ‘Midnight Special’ and ‘Bring Me Little Water, Sylvie’, set mostly around cotton fields and railroads, had rock ’n’ roll’s driving beat and hormone-jangling chord patterns, but not its sexual taint or its power to cause disturbances among the proles. Most crucially, skiffle was an offshoot of jazz, having been revived as an intermission novelty by historically minded bandleaders like Ken Colyer and Chris Barber. Its biggest star, Tony Donegan, formerly Barber’s banjo player, had changed his first name to Lonnie in honour of bluesman Lonnie Johnson.

British-made skiffle was to have an influence far beyond its barely two-year commercial life span. In its original American form, its poor white performers often could not afford conventional instruments, so would use kitchen utensils like washboards, spoons and dustbin lids, augmented by kazoos, combs-and-paper and the occasional guitar. The success of Lonnie Donegan’s ‘skiffle group’ inspired youthful facsimiles to spring up throughout the UK, rattling and plunking on homespun instruments (which actually never featured in Donegan’s line-up). The amateur music-making tradition, in long decline since its Victorian heyday, was superabundantly reborn. Buttoned-up British boys, never previously considered in the least musical, now boldly faced audiences of their families and friends to sing and play with abandon. Overnight, the guitar changed from obscure back-row rhythm instrument into an object of young-manly worship and desire surpassing even the soccer ball. Such were the queues outside musical-instrument shops that, evoking not-so-distant wartime austerities, the Daily Mirror reported a national guitar shortage.

Here Mike Jagger was ahead of the game. He already owned a guitar, a round-hole acoustic model bought for him by his parents on a family trip to Spain. The holiday snaps included one of him in a floppy straw hat, holding up the guitar neck flamenco-style and miming cod-Spanish words. It would have been his passport into any of the skiffle groups then germinating at Dartford Grammar and in the Wilmington neighbourhood. But mastering even the few simple chord shapes that covered most skiffle numbers was too much like hard work, nor could he be so uncool as to thump a single-string tea-chest ‘bass’ or scrabble at a washboard. Instead, with the organisational flair already given to programming basketball fixtures, he started a school record club. The meetings took place in a classroom during lunch hour and, he later recalled, had the atmosphere of an extra lesson. ‘We’d sit there . . . with a master behind the desk, frowning while we played Lonnie Donegan.’

As bland white vocalists grew famous with cleaned-up R&B songs, the original black performers mostly stayed in the obscurity to which they were long accustomed. One notable exception was Richard Penniman, aka Little Richard, a former dishwasher from Macon, Georgia, whose repertoire of window-shattering screams, whoops and falsetto trills affronted grown-up ears worse than a dozen Presleys. While obediently parroting rock ’n’ roll’s teenage gaucheries, Richard projected what none had yet learned to call high camp with his gold suits, flashy jewellery and exploding liquorice-whip hair. Indeed, his emblematic song, ‘Tutti Frutti’, ostensibly an anthem to ice cream, had started out as a graphic commentary on gay sex (its cry of ‘Awopbopaloobopalopbamboom!’ representing long-delayed ejaculation). He was the first rock ’n’ roller who made Mike Jagger forget all middle-class, grammar school sophistication and detachment, and surrender to the sheer mindless joy of the music.

The numerous media Cassandras who predicted rock ’n’ roll would be over in weeks rather than months found speedy corroboration in Little Richard. Touring Australia in 1958, he saw Russia’s Sputnik space satellite hurtle through the sky, interpreted it as a summons from the Almighty, threw a costly diamond ring into Sydney Harbour and announced he was giving up music to enter the ministry. When the story reached the British press, Mike asked his father for six shillings and eight pence (about thirty-eight pence) to buy ‘Good Golly Miss Molly’ because Richard was ‘retiring’ and this must be his farewell single. But Joe refused to stump up, adding, ‘I’m glad he’s retiring,’ as if it would be a formal ceremony complete with long-service gold watch.

In America, a coast-to-coast network of commercial radio stations, motivated solely by what their listeners demanded, had made rock ’n’ roll ubiquitous within a few months. But for its British constituency, to begin with, the problem was finding it. The BBC, which held a monopoly on domestic radio broadcasting, played few records of any kind, let alone this unsavoury one, in its huge daily output of live orchestral and dance-band music. To catch the hits now pouring across the Atlantic, Mike and his friends had to tune their families’ old-fashioned valve wireless sets to Radio Luxembourg, a tiny oasis of teen tolerance deep in continental Europe whose nighttime English language service consisted mainly of pop record shows. Serving the occupying forces braced for nuclear attack by Communist Russia, there were also AFN, the American Forces Network, and the US government’s ‘Voice of America’, both of which sweetened their propaganda output with generous dollops of rock and jazz.

Seeing American rock ’n’ rollers perform in person was even more problematic. Bill Haley visited Britain only once (by ocean liner) and was greeted by cheering multitudes not seen since the coronation three years earlier. Elvis Presley was expected to follow hard on his heels but, inexplicably, failed to do so. For the overwhelming majority of UK rock ’n’ roll fans, the only way to experience it was on the cinema screen. ‘Rock Around the Clock’ had originally been a soundtrack (to a film about juvenile delinquency, naturally). No sooner was Presley launched than he, too, began making movies, further evidence to his detractors that his music alone had no staying power. While most such ‘exploitation’ flicks were simply vehicles for the songs, a few were fresh and witty dramas in their own right, notably Presley’s King Creole, and The Girl Can’t Help It, featuring Little Richard with new white heartthrobs Eddie Cochran and Gene Vincent. For Mike, the epiphany came in the companionable darkness of Dartford’s State cinema, with its fuzzy-faced luminous clock and cigarette smoke drifting across the projector beam: ‘I saw Elvis and Gene Vincent, and thought, “Well, I can do this.”’

Such American acts as did make it across the Atlantic often proved woefully unable to re-create the spellbinding sound of their records in the cavernous British variety theatres and cinemas where they appeared. The shining exception was Buddy Holly and his backing group, the Crickets, whose ‘That’ll Be the Day’ topped the UK singles charts in the summer of 1957. As well as singing in a unique stuttery, hiccupy style, Holly played lead guitar and wrote or co-wrote songs that were rock ’n’ roll at its most moodily exciting, yet constructed from the same simple chord sequences as skiffle. Bespectacled and dapper, more bank clerk than idol, he was a vital factor in raising rock ’n’ roll from its blue-collar status in Britain. Middle-class boys who could never hope or dare to be Elvis now used Holly’s songbook to transform their fading-from-fashion skiffle groups into tyro rock bands.

His one and only British tour, in 1958, brought him to the Granada cinema in Woolwich, a few miles north of Dartford, on the evening of 14 March. Mike Jagger – already skilled at aping Holly’s vocal tics for comic effect – was in the audience with a group of school friends, all attending their very first rock concert. Holly’s set with the Crickets lasted barely half an hour, and was powered by just one twenty-watt guitar amplifier, yet reproduced all his record hits with near-perfect fidelity. Disdaining musical apartheid despite hailing from segregated west Texas, he freely acknowledged his indebtedness to black artists like Little Richard and Bo Diddley. He was also an extrovert showman, able to keep the beat as well as play complex solos on his solid-body Fender Stratocaster while flinging himself across the stage on his knees, even lying flat on his back. Mike’s favourite number was the B-side of ‘Oh Boy!’, Holly’s second British hit fronting the Crickets: a song in blues call-and-response style called ‘Not Fade Away’, whose quirky stop-start tempo was beaten with drumsticks on a cardboard box. The lyrics had a humour previously unknown in rock ’n’ roll (‘My love is bigger than a Cadillac / I try to show it but you drive me back . . .’). This, Mike realised, was not just someone to copy, but to be.

Yet still he made no attempt to acquire the electric guitar needed to turn him into a rock singer like Buddy Holly, Eddie Cochran or Britain’s first home-grown rock ’n’ roller, the chirpily unsexy Tommy Steele. And though attracted by the idea, along with countless other British boys, he did not seem exactly on fire with ambition. Dartford Grammar, it so happened, had produced a skiffle group named the Southerners who were something of a local legend. They had appeared on a nationwide TV talent show, Carroll Levis Junior Discoveries, and then been offered a recording test by the EMI label (which lost interest when they decided to wait until the school holidays before auditioning). Easily managing the transition from skiffle to rock, they were now a washboard-free, fully electrified combo renamed Danny Rogers and the Realms.

The Realms’ drummer, Alan Dow, was a year senior to Mike, and in the science rather than arts stream, but met him on equal terms at the weekly basketball sessions run by Mike’s father. One night when Danny and the Realms played a gig at the school, Mike sidled up to Dow backstage and asked if he could sing a number with them. ‘I was specially nervous that night, because of appearing in front of all our school mates,’ Dow recalls. ‘I said I’d rather he didn’t.’

He had no better luck when two old classmates from Wentworth Primary, David Spinks and Mike Turner, started putting together a band intended to be more faithful to rock ’n’ roll’s black originators than its white echoes. Mike suggested himself as a possible vocalist, and auditioned at David’s home in Wentworth Drive. Much as the other two liked him, they felt he neither looked nor sounded right – and, anyway, lack of a guitar was an automatic disqualification.

His first taste of celebrity did not have a singing or even a speaking part. Joe Jagger’s liaison duties for the Central Council of Physical Recreation included advising television companies about programmes to encourage sports among children and teenagers – implicitly to counter the unhealthy effects of rock ’n’ roll. In 1957, Joe became a consultant to one of the new commercial networks, ATV, on a weekly series called Seeing Sport. Over the next couple of years, Mike appeared regularly on the programme with his brother Chris and other hand-picked young outdoor types, demonstrating skills like tent erecting or canoeing.

A clip has survived of an item on rock climbing, filmed in grainy black-and-white at a beauty spot named High Rocks, near Tunbridge Wells. Fourteen-year-old Mike, in jeans and striped T-shirt, reclines in a gully with some other boys while an elderly instructor soliloquises droningly about equipment. Rather than studded mountaineering boots, which could damage these particular rock faces, the instructor recommends ‘ordinary gym shoes . . . like the kind Mike is wearing’. Mike allows one of his legs to be raised, displaying his virtuous rubber sole. For his father’s sake, he can’t show what he really thinks of this fussy, ragged-sweatered little man treating him like a dummy. But the deliberately blank stare – and the tongue, flicking out once too often to moisten the outsize lips – say it all.

At school he continued to coast along, doing just enough to get by in class and on the games field. To his teachers and classmates alike he gave the impression he was there only under sufferance and that his thoughts were somewhere infinitely more glamorous and amusing. ‘Too easily distracted’, ‘attitude rather unsatisfactory’ and other such faint damnations recurred through his end-of-term reports. In the summer of 1959 he took his GCE O-level exams, which in those days were assessed by marks out of 100 rather than grades. He passed in seven subjects, just scraping through English literature (48), geography (51), history (56), Latin (49) and pure mathematics (53), doing moderately well in French (61) and English language (66). Further education being still for the fortunate minority, this was when most pupils left, aged sixteen, to start jobs in banks or solicitors’ offices. Mike, however, went into the sixth form for two more years to take A-level English, history and French. His headmaster, Lofty Hudson, predicted that he was ‘unlikely to do brilliantly in any of them’.

He was also made a school prefect, in theory an auxiliary to Lofty and the staff in maintaining order and discipline. But it was an appointment that the head soon came to regret. Though Elvis Presley had originally cast his disruptive spell over girls, he had left a more lasting mark on boys, especially British ones, turning their former upright posture to a rebellious slouch and their former sunny smiles to sullen pouts, replacing their short-back-and-sides haircuts with toppling greasy quiffs, ‘ducks’ arses’ and sideburns. The Teddy Boy (i.e., Edwardian) style, too, was no longer peculiar to lawless young artisans but had introduced middle- and upper-class youths to ankle-hugging trousers, two-button ‘drape’ jackets and Slim Jim ties.

Mike was not one to go too far – his mother would never have allowed it – but he broke Dartford Grammar’s strict dress code in subtle ways that were no less provocative to Lofty’s enforcers, sporting slip-on moccasin shoes instead of clumpy black lace-ups; a pale ‘shorty’ raincoat instead of the dark, belted kind; a low-fastening black jacket with a subtle gold fleck instead of his school blazer. Among his fiercest sartorial critics was Dr Wilfred Bennett, the senior languages tutor, whom he had already displeased by consistently performing below his abilities in French. Matters came to a head at the school’s annual Founder’s Day ceremony, attended by bigwigs from Dartford Council and other local dignitaries, when his gold-flecked jacket marred the otherwise faultless rows of regulation blazers. There was a heated confrontation with Dr Bennett afterwards, which ended with the teacher lashing out – as teachers then could with impunity – and Mike sprawled out on the ground.

Perhaps more than any other pastime, music forges friendships between individuals who otherwise have nothing whatsoever in common. Never was it truer than in late 1950s Britain, when for the first time young people found a music of their own, only to have it derided by adult society in general. A few months from now, this feeling of persecuted brotherhood would initiate, or rather revive, the most important relationship of Mike’s life. The prologue, as it were, took place in his last two years at school when, somewhat surprisingly, the genteel kid from Wilmington chummed up with a plumber’s son from Bexleyheath named Dick Taylor.

Dick’s consuming passion was not rock ’n’ roll but blues, the black music that had preceded it by something like half a century and provided its structure, its chords and its rebellious soul. For this esoteric taste he had to thank his older sister Robin, a hard-core blues fan while her friends swooned over white crooners like Frankie Vaughan and Russ Hamilton. Robin knew all its greatest exponents and, more important, knew where to find it on AFN or Voice of America, where the occasional blues record was played for the benefit of black GIs helping to defend Europe from communism. Dick, in turn, passed on the revelation to a small coterie at Dartford Grammar that included Mike Jagger.

This was unconventionality on an altogether more epic scale than shorty raincoats. Liking rock ’n’ roll with its concealed black subtext was one thing – but this was music wholly reflecting the experience of black people, which few musicians but black ones had ever authentically created. In late-fifties Britain one still very seldom saw a black face outside London, least of all in the bucolic Home Counties: hence the unimpaired popularity of Helen Bannerman’s children’s story Little Black Sambo, Agatha Christie’s stage play Ten Little Niggers and BBC TV’s Black and White Minstrels, to say nothing of ‘nigger brown’ shoe polish and dogs routinely named ‘Blackie’, ‘Sambo’ and ‘Nigger’. Nor was there any but the most marginal, patronising awareness of black culture. Mass immigration until now had come mainly from former colonies in the Caribbean, furnishing a new menial class to staff public transport and the National Health Service. The only generic black music most Britons ever heard was West Indian calypsos, full of careful deference to the host nation and usually employed as a soundtrack to first-class cricket matches.

There might seem no possible meeting point between suburban Kent with its privet hedges and slow green buses, and the Mississippi Delta with its tar-and-paper cabins, shanty towns and prison farms; still less between a genteelly raised white British boy and the dusty black troubadours whose chants of pain or anger or defiance had lightened the load and lifted the spirits of untold fellow sufferers under twentieth-century servitude. For Mike, the initial attraction of the blues was simply that of being different – standing out from his coevals as he already did through basketball. To some extent, too, it had a political element. This was the era of English literature’s so-called angry young men and their well-publicised contempt for the cosiness and insularity of life under Harold Macmillan’s Tory government. One of their numerous complaints, voiced in John Osborne’s play Look Back in Anger, was that ‘there are no good, brave causes left’. To a would-be rebel in 1959, the oppression of black musicians in pre-war rural America was more than cause enough.

But Mike’s love of the blues was as passionate and sincere as he’d ever been about anything in his life, or perhaps ever would be. In crackly recordings, mostly made long before his birth, he found an excitement – an empathy – he never had in the wildest moments of rock ’n’ roll. Indeed, he could see now just what an impostor rock was in so many ways; how puny were its wealthy young white stars in comparison with the bluesmen who’d written the book and, mostly, died in poverty; how those long-dead voices, wailing to the beat of a lone guitar, had a ferocity and humour and eloquence and elegance to which nothing on the rock ’n’ roll jukebox even came close. The parental furore over Elvis Presley’s sexual content, for instance, seemed laughable if one compared the pubescent hot flushes of ‘Teddy Bear’ and ‘All Shook Up’ with Lonnie Johnson’s syphilis-crazed ‘Careless Love’ or Blind Lemon Jefferson’s nakedly priapic ‘Black Snake Moan’. And what press-pilloried rock ’n’ roll reprobate, Little Richard or Jerry Lee Lewis, could hold a candle to Robert Johnson, the boy genius of the blues who lived almost the whole of his short life among drug addicts and prostitutes and was said to have made a pact with the devil in exchange for his peerless talent?

Though skiffle had brought some blues songs into general consciousness, the music still had only a tiny British following – mostly ‘intellectual’ types who read leftish weeklies, wore maroon socks with sandals and carried their change in leather purses. Like skiffle, it was seen as a branch of jazz: the few American blues performers who ever performed live in Britain did so through the sponsorship – charity, some might say – of traditional jazz bandleaders like Humphrey Lyttelton, Ken Colyer and Chris Barber. ‘Humph’ had been bringing Big Bill Broonzy over as a support attraction since 1950, while every year or so the duo of Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee attracted small but ardent crowds to Colyer’s Soho club, Studio 51. After helping give birth to skiffle, Barber had become a stalwart of the National Jazz League, which strove to put this most lackadaisical of the arts on an organised footing and had its own club, the Marquee in Oxford Street. Here, too, from time to time, some famous old blues survivor would appear onstage, still bewildered by his sudden transition from Chicago or Memphis.

Finding the blues on record was almost as difficult. It was not available on six-shilling and fourpenny singles, like rock and pop, but only on what were still known as ‘LPs’ (long-players) rather than albums, priced at a daunting thirty shillings (£1.50) and up. To add to the expense, these were usually not released on British record labels but imported from America in their original packaging with the price in dollars and cents crossed out and a new one in pounds, shillings and pence substituted. Such exotica was, of course, not stocked by record shops in Dartford or even in large neighbouring towns such as Chatham or Rochester. To find it, Mike and Dick had to go to up to London and trawl through the racks at specialist dealers like Dobell’s on Charing Cross Road.

Their circle at Dartford Grammar School included two other boys with the same recondite passion. One was a rather quiet, bookish type from the arts stream named Bob Beckwith; the other was Mike’s Wilmington neighbour, the science student Alan Etherington. In late 1959, during Mike’s first term in the sixth form, the four decided to form a blues band. Bob and Dick played guitar, Alan (a drummer and bugler in the school cadet force) played percussion on a drum kit donated by Dick’s grandfather, and Mike was the vocalist.