Mexico Set

Len Deighton

Long-awaited reissue of the second part of the classic spy trilogy, GAME, SET and MATCH, when the Berlin Wall divided not just a city but a world.A lot of people had plans for Bernard Samson…When they spotted Erich Stinnes in Mexico City, it was obvious that Bernard Samson was the right man to ‘enrol’ him. With his domestic life a shambles and his career heading towards disaster, Bernard needed to prove his reliability. and he knew Stinnes already – Bernard had been interrogated by him in East Berlin.But Bernard risks being entangled in a lethal web of old loyalties and old betrayals.All he knows for sure is that he has to get Erich Stinnes for London.Who’s pulling the strings is another matter…

Cover designer’s note (#u9c0e2a0f-d19c-58b3-a995-31eaa329af39)

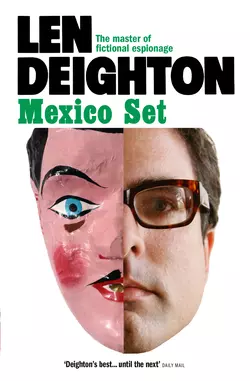

Some years ago I attended a design congress in Oaxaca, Mexico, where for a few pesos I purchased some wonderful papier mâché masks, my favourite being the umbrella salesmen, a moustachioed gentleman with a gold tooth. This image seemed to fit perfectly as a matching half to Len Deighton’s protagonist Bernard Samson’s face in Mexico Set. This two-faced quality seemed, to me, to speak volumes for the nature of the business that Bernard is in, and also to the conflicted nature of his character.

Some time later I was invited to speak at a design conference in Queretaro, Mexico. To my delight the event took place during the festival of ‘Día de los Muertos’, ‘The Day of the Dead’, during which time many wonderful related artefacts are sold. One of these items comes from the folk art of ‘papel picado’, the brightly coloured tissue paper-cuts. I thought that the image of a skeleton reading a book would be a most appropriate illustration for this book’s back cover.

At the heart of every one of the nine books in this triple trilogy is Bernard Samson, so I wanted to come up with a neat way of visually linking them all. When the reader has collected all nine books and displays them together in sequential order, the books’ spines will spell out Samson’s name in the form of a blackmail note made up of airline baggage tags. The tags were drawn from my personal collection, and are colourful testimony to thousands of air miles spent travelling the world.

Arnold Schwartzman OBE RDI

LEN DEIGHTON

Mexico Set

Copyright (#u9c0e2a0f-d19c-58b3-a995-31eaa329af39)

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Hutchinson & Co. (Publishers) Ltd 1984

Copyright © Pluriform Publishing Company BV 1984

Introduction copyright © Pluriform Publishing Company BV 2010

Cover designer’s note © Arnold Schwartzman 2010

Cover design and photography © Arnold Schwartzman 2010

Thanks are due to the following for permission to quote lines from ‘Bye-Bye Blackbird’:

The Remick Music Corporation, New York and Detroit, and EMI Music Publishing Limited,

London. Copyright © 1926, 1948

Len Deighton asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780008124991

Ebook Edition © March 2015 ISBN: 9780007387199

Version: 2017-09-07

Contents

Cover (#uef38c34b-36f1-5f0f-a318-b8ef23e407c4)

Cover Designer’s Note (#u18ddf34e-5c6c-5891-9c26-f4a66bab2bdf)

Title Page (#u8393171f-6879-5fad-a73b-289a198cee88)

Copyright (#ufdec6311-cbc7-5107-acc6-ed671762f692)

Introduction (#ue203dc77-49d8-5683-83a9-33b20067448d)

Chapter 1 (#uaf7f9076-dcf9-530a-805f-445943f0ecf7)

Chapter 2 (#ufd5258aa-cc93-552d-9118-f84c9044ea5f)

Chapter 3 (#u1b74b20a-c8a6-5065-af24-767b6f78156a)

Chapter 4 (#u12af5a2f-8eb9-5306-b852-e67bc1dcbe3f)

Chapter 5 (#u156ec08a-9951-5fcd-b5e6-f11ec0f7b326)

Chapter 6 (#ucfd4521a-af60-51c3-9f7d-2a8a3c28fb47)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Len Deighton (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Introduction (#u9c0e2a0f-d19c-58b3-a995-31eaa329af39)

During the First World War the neutral Netherlands had been the arena in which the rival spy services brawled. In the Second World War it was Portugal that served that purpose. In the Cold War the arena eventually became Mexico. It was in safe houses in Mexico City where the officers of the GRU and those of the KGB clashed, reasoned or sometimes socialized with their Allied opposite numbers. For Moscow, Washington and London these contacts were vital, but for the personnel stationed there the job was a consignment to the promotional rubbish heap. No interesting memoirs were written by the men who spent the Cold War years in Mexico. No indiscreet revelations were spilled into the well-paid serializations that sold the newspapers of that time. Mexico City only came into the headlines as a stopover for Lee Harvey Oswald when the assassination of President John Kennedy was being investigated.

The very first time I visited Mexico I was staying at the YMCA in Los Angeles. I was a penniless art student; well, perhaps that overstates it: let’s say I was living from hand to mouth and being saved from starvation by the care and consideration given me by the mother of an American artist I knew in London. Left to my own devices on my last day I ate supper from a hot-dog stand. Los Angeles was not the gourmet’s paradise that it later became, and street food was America’s answer to the fugu fish. I spent the night groaning in the toilets and when daylight finally arrived I was feeling very ill. In my pocket I had a Greyhound Bus ticket that would take me a few hundred miles into a country I knew nothing about and, with that physical stamina and grim determination that is the currency of the young and foolish, I dragged myself down to the bus depot, threw myself across the back seat and closed my eyes. You may wish to note that the back seat of a Greyhound Bus is not the best place to be if you are alternately praying for help and wishing to die. The sort of buses that are built for Mexico are fitted with robust and unyielding suspensions. The rearmost part of the chassis takes an undue proportion of the punishment that comes with loose surface roads and pot-holes. I recall every jolt of that journey but towards the end of it I was sitting upright and looking out of the window trying to see through the grime and the dust. As always, the Greyhound Bus got me there. During the nineteen fifties I did so many thousands of miles on Grey Buses that they used me in their advertising.

I survived the journey. I climbed down from the bus into the sweaty noon of Mexico’s west coast, spotted a bench and a Coca Cola stand and I started writing some notes for my diary. I’m told that nowadays this region of Mexico is packed with luxury hotels, motor-yachts and marinas but back in the nineteen fifties it was just a succession of small villages punctuating empty stretches of bleak, cactus strewn landscape. But the traveller counting the pennies gets a far more authentic impression of a country than any luxury tour can provide. The Mexicans were kind and generous to me and, if the steady diet of beans and tortillas I ate became monotonous, I knew that was only because I wasn’t as hungry as those around me. I felt at home. From that time I have always enjoyed being with Mexicans, and nowadays I am delighted to have become a part of a kind and joyful Mexican family.

I have always contrived to visit places at their least attractive time. Ski resorts in high summer, Asia when the monsoons come, Algeria in the annual rainstorms and the French Riviera when the restaurants are shuttered and the casinos being renovated. It may sound perverse but I can only get under the skin of foreign destinations when the lipstick and powder has been set aside and the spots and pimples are there for all to see. So, when I researched Mexico Set I saw it in the stormy season when the steely thunderclouds reach down lower and lower upon the thirsty earth until torrential rain arrives to lash the streets with fury.

Mexico Set opens with Bernard Samson and Dicky Cruyer in Mexico City. For Bernard the problems are piling higher and higher. While Berlin Game saw Bernard battered by professional dilemmas we now see the complex uncertainties of his private life. In this book I am able to do a few of the things that made the whole nine-book project so worthwhile for me. Instead of going back to start all over again with a new story I could take my characters deeper and deeper into the lives that, while being so weird and wonderful, are burdened with the domestic everyday events that we all endure.

Every writer wants to maximize everything: intriguing characters, labyrinthine plot, humorous asides, unfolding landscape, crisp dialogue. But now I didn’t have to cram all that tightly together; having the space granted by the planned future books gave me a freedom to do something better than I had ever done before. Of course every story worth reading has all of the above. Berlin Game with its dénouement set the scene. After that Mexico Set used arguments, anger and confidences to reveal new sides of the characters and their shifting attitudes to each other. Many important characters arrive in subsequent volumes but by the end of this book all the stars are on the stage. Yet in this book – and I know this is going to sound corny – Mexico is the star. It is a wonderful country, its cruel landscape tormented by its amazing weather patterns. With the ever-present danger of ending up writing a travel guide dominated by weather reports, I have kept Mexico as a persistent backdrop to the story of Bernard Samson.

Are the stories based on real people? Scott Fitzgerald argued with Ernest Hemingway about the nature of fiction. Writing to a friend who was deeply offended by the way she was depicted in his book, Fitzgerald said: ‘In my theory, utterly opposite to Ernest’s, about fiction i.e. that it takes half a dozen people to make a synthesis strong enough to create a fiction character – in that theory, or rather in despite of it, I used you again and again in Tender [is the Night].’ And so it is that most writers take manners and gestures and other bits and pieces from the people they meet, they steal slices from the landscape, relive the pain and joy of their experience. In this way the writer pushes beyond reality in pursuit of some sort of truth.

Len Deighton, 2010

1 (#u9c0e2a0f-d19c-58b3-a995-31eaa329af39)

‘Some of these people want to get killed,’ said Dicky Cruyer, as he jabbed the brake pedal to avoid hitting a newsboy. The kid grinned as he slid between the slowly moving cars, flourishing his newspapers with the controlled abandon of a fan dancer. ‘Six Face Firing Squad’; the headlines were huge and shiny black. ‘Hurricane Threatens Veracruz.’ A smudgy photo of street fighting in San Salvador covered the whole front of a tabloid.

It was late afternoon. The streets shone with that curiously bright shadowless light that precedes a storm. All six lanes of traffic crawling along the Insurgentes halted, and more newsboys danced into the road, together with a woman selling flowers and a kid with lottery tickets trailing from a roll like toilet paper.

Picking his way between the cars came a handsome man in old jeans and checked shirt. He was accompanied by a small child. The man had a Coca Cola bottle in his fist. He swigged at it and then tilted his head back again, looking up into the heavens. He stood erect and immobile, like a bronze statue, before igniting his breath so that a great ball of fire burst from his mouth.

‘Bloody hell!’ said Dicky. ‘That’s dangerous.’

‘It’s a living,’ I said. I’d seen the fire-eaters before. There was always one of them performing somewhere in the big traffic jams. I switched on the car radio but electricity in the air blotted out the music with the sounds of static. It was very hot. I opened the window but the sudden stink of diesel fumes made me close it again. I held my hand against the air-conditioning outlet but the air was warm.

Again the fire-eater blew a huge orange balloon of flame into the air.

‘For us,’ explained Dicky. ‘Dangerous for people in the cars. Flames like that, with all these petrol fumes … can you imagine?’ There was a slow roll of thunder. ‘If only it would rain,’ said Dicky. I looked at the sky, the low black clouds trimmed with gold. The huge sun was coloured bright red by the city’s ever-present blanket of smog, and squeezed tight between the glass buildings that dripped with its light.

‘Who got this car for us?’ I said. A motorcycle, its pillion piled high with cases of beer, weaved precariously between the cars, narrowly missing the flower seller.

‘One of the embassy people,’ said Dicky. He released the brake and the big blue Chevrolet rolled forward a few feet and then all the traffic stopped again. In any town north of the border this factory-fresh car would not have drawn a second glance. But Mexico City is the place old cars go to die. Most of those around us were dented and rusty, or they were crudely repainted in bright primary colours. ‘A friend of mine lent it to us.’

‘I might have guessed,’ I said.

‘It was short notice. They didn’t know we were coming until the day before yesterday. Henry Tiptree – the one who met us at the airport – let us have it. It was a special favour because I knew him at Oxford.’

‘I wish you hadn’t known him at Oxford; then we could have rented one from Hertz – with air-conditioning that worked.’

‘So what can we do …’ said Dicky irritably ‘… take it back and tell him it’s not good enough for us?’

We watched the fire-eater blow another balloon of flame while the small boy hurried from driver to driver, collecting a peso here and there for his father’s performance.

Dicky took some Mexican coins from the slash pocket of his denim jacket and gave them to the child. It was Dicky’s faded work suit, his cowboy boots and curly hair that had attracted the attention of the tough-looking woman immigration officer at Mexico City airport. It was only the first-class labels on his expensive baggage, and the fast talking of Dicky’s Counsellor friend from the embassy, that saved him from the indignity of a body search.

Dicky Cruyer was a curious mixture of scholarship and ruthless ambition, but he was insensitive, and this was often his undoing. His insensitivity to people, place and atmosphere could make him seem a clown instead of the cool sophisticate that was his own image of himself. But that didn’t make him any less terrifying as friend or foe.

The flower seller bent down, tapped on the window glass and waved at Dicky. He shouted ‘Vamos!’ It was almost impossible to see her face behind the unwieldy armful of flowers. Here were blossoms of all colours, shapes and sizes. Flowers for weddings and flowers for dinner hostesses, flowers for mistresses and flowers for suspicious wives.

The traffic began moving again. Dicky shouted ‘Vamos!’ much louder.

The woman saw me reaching into my pocket for money and separated a dozen long-stemmed pink roses from the less expensive marigolds and asters. ‘Maybe some flowers would be something to give to Werner’s wife,’ I said.

Dicky ignored my suggestion. ‘Get out of the way,’ he shouted at the old woman, and the car leaped forward. The old woman jumped clear.

‘Take it easy, Dicky, you nearly knocked her over.’

‘Vamos! I told her; vamos. They shouldn’t be in the road. Are they all crazy? She heard me all right.’

‘Vamos means “Okay, let’s go”,’ I said. ‘She thought you wanted to buy some.’

‘In Mexico it also means scram,’ said Dicky driving up close to a white VW bus in front of us. It was full of people and boxes of tomatoes, and its dented bodywork was caked with mud in the way that cars become when they venture on to country roads at this rainy time of year. Its exhaust-pipe was newly bound up with wire, and the rear panel had been removed to help cool the engine. The sound of its fan made a very loud whine so that Dicky had to speak loudly to make himself heard. ‘Vamos; scram. They say it in cowboy films.’

‘Maybe she doesn’t go to cowboy films,’ I said.

‘Just keep looking at the street map.’

‘It’s not a street map; it’s just a map. It only shows the main streets.’

‘We’ll find it all right. It’s off Insurgentes.’

‘Do you know how big Mexico City is? Insurgentes is about thirty-five miles long,’ I said.

‘You look on your side and I’ll look this side. Volkmann said it’s in the centre of town.’ He sniffed. ‘Mexico, they call it. No one here says “Mexico City”. They call the town Mexico.’

I didn’t answer; I put away the little coloured town plan and stared out at the crowded streets. I was quite happy to be driven round the town for an hour or two if that’s what Dicky wanted.

Dicky said, ‘Somewhere in the centre of town would mean the Paseo de la Reforma near the column with the golden angel. At least that’s what it would mean to any tourist coming here for the first time. And Werner Volkmann and his wife Zena are here for the first time. Right?’

‘Werner said it was going to be a second honeymoon.’

‘With Zena I would have thought one honeymoon would be enough,’ said Dicky.

‘More than enough,’ I said.

Dicky said, ‘I’ll kill your bloody Werner if he’s brought us out from London on a wild-goose chase.’

‘It’s a break from the office,’ I said. Werner had become my Werner I noticed and would remain so if things went wrong.

‘For you it is,’ said Dicky. ‘You’ve got nothing to lose. Your desk will be waiting for you when you get back. But there’s a dozen people in that building scrambling round for my job. This will give Bret just the chance he needs to take over my work. You realize that, don’t you?’

‘How could Bret want to take your job, Dicky? Bret is senior to you.’

The traffic was moving at about five miles an hour. A small dirty-faced child in the back of the VW bus was staring at Dicky with great interest. The insolent stare seemed to disconcert him. Dicky turned to look at me. ‘Bret is looking for a job that would suit him; and my job would suit him. Bret will have nothing to do now that his committee is being wound up. There’s already an argument about who will have his office space. And about who will have that tall blonde typist who wears the white sweaters.’

‘Gloria?’ I said.

‘Oh? Don’t say you’ve been there?’

‘Us workers stick together, Dicky,’ I said.

‘Very funny,’ said Dicky. ‘If Bret takes over my job, he’ll chase your arse. Working for me will seem like a holiday. I hope you realize that, old pal.’

I didn’t know that the brilliant career of Bret was taking a downturn to the point where Dicky was running scared. But Dicky had taken a PhD in office politics so I was prepared to believe him. ‘This is the Pink Zone,’ I said. ‘Why don’t you park in one of these hotels and get a cab?’

Dicky seemed relieved at the idea of letting a cab driver find Werner Volkmann’s apartment but, being Dicky, he had to argue against it for a couple of minutes. As he pulled into the slow lane the dirty child in the VW smiled and then made a terrible face at us. Dicky glanced at me and said, ‘Are you pulling faces at that child? For God’s sake, act your age, Bernard.’ Dicky was in a bad mood, and talking about his job had made him more touchy.

He turned off Insurgentes on to a side-street and cruised eastwards until we found a car-park under one of the big hotels. As we went down the ramp into the darkness he switched the headlights on. This was a different world. This was where the Mercedes, Cadillacs and Porsches lived in comfort, shiny with health, smelling of new leather and guarded by two armed security men. One of them pushed a ticket under a wiper and lifted the barrier so that we could drive through.

‘So your school chum Werner spots a KGB heavy here in town. Why did Controller (Europe) insist that I come out here at this stinking time of year?’ Dicky was cruising very slowly round the dark garage, looking for a place to park.

‘Werner didn’t spot Erich Stinnes,’ I said. ‘Werner’s wife spotted him. And there’s a departmental alert for him. There’s a space.’

‘Too small; this is a big car. Alert? You don’t have to tell me that, old boy. I signed the alert, Remember me? Controller of German Stations? But I’ve never seen Erich Stinnes. I wouldn’t know Erich Stinnes from the man in the moon. You’re the one who can identify him. Why do I have to come?’

‘You’re here to decide what we do. I’m not senior enough or reliable enough to make decisions. What about there, next to the white Mercedes?’

‘Ummmmm,’ said Dicky. He had trouble parking the car in the space marked out by the white lines. One of the security guards – a big poker-faced man in starched khakis and carefully polished high boots – came to watch us. He stood arms akimbo, staring, while Dicky went backwards and forwards trying to squeeze between the white convertible and a concrete stanchion that bore brightly coloured patches of enamel from other cars. ‘Did you really make out with that blonde in Bret’s office?’ said Dicky as he abandoned his task and reversed into another space marked ‘reserved’.

‘Gloria? I thought everyone knew about me and Gloria,’ I said. In fact I knew her no better than Dicky did but I couldn’t resist the chance to needle him. ‘My wife’s left me. I’m a free man again.’

‘Your wife defected,’ said Dicky spitefully. ‘Your wife is working for the bloody Russkies.’

‘That’s over and done with,’ I said. I didn’t want to talk about my wife or my children or any other problems. And if I did want to talk about them Dicky would be the last person I’d choose to confide in.

‘You and Fiona were very close,’ said Dicky accusingly.

‘It’s not a crime to be in love with your wife,’ I said.

‘Taboo subject, eh?’ It pleased Dicky to touch a nerve and get a reaction. I should have known better than to respond to his taunts. I was guilty by association. I’d become a probationer once more and I’d remain one until I proved my loyalty all over again. Nothing had been said to me officially, but Dicky’s little flash of temper was not the first indication of what the department really felt.

‘I didn’t come on this trip to discuss Fiona,’ I said.

‘Don’t keep bickering,’ said Dicky. ‘Let’s go and talk to your friend Werner and get it finished. I can’t wait to be out of this filthy hell-hole. January or February; that’s the time when people who know what’s what go to Mexico. Not in the middle of the rainy season.’

Dicky opened the door of the car and I slid across the seat to get out his side. ‘Prohibido aparcar,’ said the security guard, and with arms folded he planted himself in our path.

‘What’s that?’ said Dicky, and the man said it again. Dicky smiled and explained, in his schoolboy Spanish, that we were residents of the hotel, we would only be leaving the car there for half an hour, and we were engaged on very important business.

‘Prohibido aparcar,’ said the guard stolidly

‘Give him some money, Dicky,’ I said. ‘That’s all he wants.’

The security guard looked from Dicky to me and stroked his large black moustache with the ball of his thumb. He was a big man, as tall as Dicky and twice as wide.

‘I’m not going to give him anything,’ said Dicky. ‘I’m not going to pay twice.’

‘Let me do it,’ I said. ‘I’ve got small money here.’

‘Stay out of this,’ said Dicky. ‘You’ve got to know how to handle these people.’ He stared at the guard. ‘Nada! Nada! Nada! Entiende?’

The guard looked down at our Chevrolet and then plucked the wiper between finger and thumb and let it fall back against the glass with a thump. ‘He’ll wreck the car,’ I said. ‘This is not the time to get into a hassle you can’t win.’

‘I’m not frightened of him,’ said Dicky.

‘I know you’re not, but I am.’ I got in front of him before he took a swing at the guard. There was a hard, almost vicious, streak under Dicky’s superficial charm, and he was a keen member of the Foreign Office judo club. Dicky wasn’t frightened of anything; that’s why I didn’t like working with him. I folded some paper money into the guard’s ready hand and pushed Dicky towards the sign that said ‘Elevator to hotel lobby’. The guard watched us go, his face still without emotion. Dicky wasn’t pleased either. He thought I’d tried to protect him against the guard and he felt belittled by my interference.

The hotel lobby was that same ubiquitous combination of tinted mirror, plastic marble and spongy carpet underlay that international travellers are reputed to admire. We sat down under a huge display of plastic flowers and looked at the fountain.

‘Machismo,’ said Dicky sadly. We were waiting for the top-hatted hotel doorman to find a taxi driver who would take us to Werner’s apartment. ‘Machismo,’ he said again reflectively. ‘Every last one of them is obsessed by it. It’s why you can’t get anything done here. I’m going to report that bastard downstairs to the manager.’

‘Wait until after we’ve collected the car,’ I advised.

‘At least the embassy sent a Counsellor to meet us. That means that London has told them to give us full diplomatic back-up.’

‘Or it means Mexico City embassy staff – including your pal Tiptree – have a lot of time on their hands.’

Dicky looked up from counting his traveller’s cheques. ‘What do I have to do, Bernard, to make you remember it’s Mexico? Not Mexico City; Mexico.’

2 (#u9c0e2a0f-d19c-58b3-a995-31eaa329af39)

This was a new Werner Volkmann. This was not the introverted Jewish orphan I’d been at school with, nor the lugubrious teenager I’d grown up with in Berlin, nor the affluent, overweight banker who was welcome on both sides of the Wall. This new Werner was a tough, muscular figure in short-sleeved cotton shirt and well-fitting Madras trousers. His big droopy moustache had been trimmed and so had his bushy black hair. Being on holiday with his twenty-two-year-old wife had rejuvenated him.

He was standing on the sixth-floor balcony of a small block of luxury apartments in downtown Mexico City. From here was a view across this immense city, with the mountains a dark backdrop. The dying sun was turning the world pink, now that the stormclouds had passed over. Long ragged strips of orange and gold cloud were torn across the sky, like a poster advertising a smog-reddened sun ripped by a passing vandal.

The balcony was large enough to hold a lot of expensive white garden furniture as well as big pots of tropical flowers. Green leafy plants climbed overhead to provide shade, while a collection of cacti were arrayed on shelves like books. Werner poured a pink concoction from a glass jug. It was like a watery fruit salad, the sort of thing they pressed on you at parties where no one got drunk. It didn’t look tempting, but I was hot and I took one gratefully.

Dicky Cruyer was flushed; his cowboy shirt bore dark patches of sweat. He had his blue-denim jacket slung over his shoulder. He tossed it on to a chair and reached out to take a drink from Werner.

Werner’s wife Zena held out her glass for a refill. She was full-length on a reclining chair. She was wearing a sheer, rainbow-striped dress through which her suntanned limbs shone darkly. As she moved to sip her drink, German fashion magazines, balanced on her belly, slid to the ground and flapped open. Zena cursed softly. It was the strange, flat-accented speech of eastern lands that were no longer German. It was probably the only thing she’d inherited from her impoverished parents, and I had the feeling she would sometimes have been happier without it.

‘What’s in this drink?’ I said.

Werner recovered the magazines from the floor and gave them to his wife. In business he could be tough, in friendships outspoken, but to Zena he was always indulgent.

Werner raised money from Western banks to pay exporters to East Germany, and then eventually collected the money from the East German government, taking a tiny percentage on every deal. ‘Avalizing’ it was called. But it wasn’t a banker’s business; it was a free-for-all in which many got their fingers burned. Werner had to be tough to survive.

‘In the drink? Fruit juices,’ said Werner. ‘It’s too early for alcohol in this sort of climate.’

‘Not for me it isn’t,’ I said. Werner smiled but he didn’t go anywhere to get me a proper drink. He was my oldest and closest friend; the sort of close friend who gives you the excoriating criticism that new enemies hesitate about. Zena didn’t look up; she was still pretending to read her magazines.

Dicky had stepped into the jungle of flowers to get a clearer view of the city. I looked over his shoulder to see the traffic still moving sluggishly. In the street below there were flashing red lights and sirens as two police cars mounted the pavement to get around the traffic. In a city of fifteen million people there is said to be a crime committed every two minutes. The noise of the streets never ceased. As the flow of homegoing office workers ended, the influx of people to the Zona Rosa’s restaurants and cinemas began. ‘What a madhouse,’ said Dicky.

A malevolent-looking black cat awoke and jumped softly down from its position on the footstool. It went over to Dicky and sank a claw into his leg and looked up at him to see how he’d take it. ‘Hell!’ shouted Dicky. ‘Get away, you brute.’ Dicky aimed a blow at the cat but missed. The cat moved very fast as if it had done the same thing before to other gringos.

Wincing with pain and rubbing his leg, Dicky moved well away from the cat and went to the other end of the balcony to look inside the large lounge with its locally made tiles, old masks and Mexican textiles. It looked like an arts and crafts shop, but obviously a lot of money had been spent getting it that way. ‘Nice place you’ve got here,’ said Dicky. There was more than a hint of sarcasm in his remark. It was not Dicky’s style. Anything that departed much from Harrod’s furniture department was too foreign for him.

‘It belongs to Zena’s uncle and aunt,’ explained Werner. ‘We’re taking care of it while they’re in Europe.’ That explained the notebook I’d seen near the telephone. Zena had neatly entered ‘wine glass’, ‘tumbler’, ‘wine glass’, ‘small china bowl with blue flowers’. It was a list of breakages, an example of Zena’s sense of order and rectitude.

‘You chose a bad time of year,’ complained Dicky. ‘Or rather Zena’s uncle chose a good one.’ He drained the glass, tipping it up until the ice cubes, cucumber and pieces of lemon slid down the glass and rested against his lips.

‘Zena doesn’t mind it,’ said Werner, as if his own opinions were of no importance.

Zena, still concentrating on her magazine, said, ‘I love the sun.’ She said it twice and continued to read without losing her place.

‘If only it would rain,’ said Werner. ‘It’s this build-up to the storms that makes it so unbearable.’

‘So you saw this chap Stinnes?’ said Dicky very casually, as if that wasn’t the reason that the two of us had dragged ourselves four thousand miles to talk to them.

‘At the Kronprinz,’ said Werner.

‘What’s the Kronprinz?’ said Dicky. He put down his glass and used a paper napkin to dry his lips.

‘A club.’

‘What sort of club?’ Dicky stuck his thumbs into the back of his leather belt and looked down at the toes of his cowboy boots reflectively. The cat had followed Dicky and looked as if it was about to reach up above his boot to put a claw into his thin calf again. Dicky aimed a vicious little kick at it but the cat was too quick for him. ‘Get away,’ said Dicky, more loudly this time.

‘I’m sorry about the cat,’ said Werner. ‘But I think Zena’s aunt only let us use the place because we’d be company for Cherubino. It’s your jeans. Cats like to claw at denim.’

‘It bloody hurts,’ said Dicky, rubbing his leg. ‘You should get its claws clipped or something. In this part of the world cats carry all kinds of diseases.’

‘What’s it matter what sort of club?’ said Zena suddenly. She closed the magazine and pushed her hair back. She looked different with her hair loose; no longer the tough little career girl, more the lady of leisure. Her hair was long and jet black and held with a silver Mexican comb which she brandished before tossing her hair back and fixing it again.

‘A club for German businessmen. It’s been going since 1902,’ said Werner. ‘Zena likes the buffet and dance they have on Friday nights. There’s a big German colony here in the city. There always has been.’

‘Werner said there would be a cash payment for finding Stinnes,’ said Zena.

‘There usually is,’ said Dicky slyly, although he knew there would be no chance of a cash payment for such a routine report. It must have been Werner’s way of encouraging Zena to cooperate with us. I looked at Werner and he looked back at me without changing his expression.

‘How do you know it really is Stinnes?’ said Dicky.

‘It’s Stinnes all right,’ said Werner stoically. ‘His name is on his membership card and his credit at the bar is in that name.’

‘And his cheque book,’ said Zena. ‘His name is printed on his cheques.’

‘What bank?’ I asked.

‘Bank of America,’ said Zena. ‘A branch in San Diego, California.’

‘Names mean nothing,’ said Dicky. ‘How do you know this fellow is a KGB man? And, even if he is, what makes you so sure that this is the johnny who interrogated Bernard in East Berlin?’ A brief movement of the hand in my direction. ‘It might be someone using the same cover name. We’ve known KGB people do that. Right, Bernard?’

‘It has been known,’ I said, although I was damned if I could recall any examples of such sloppy tactics by the plodding but thorough bureaucrats of the KGB.

‘How much?’ said Zena. And, when Dicky looked at her and raised his eyebrows, she said, ‘How much are you going to give us for reporting Stinnes? Werner said you want him badly. Werner said he was very important.’

‘Steady on,’ said Dicky. ‘We don’t have him yet. We haven’t even positively identified him.’

‘Erich Stinnes,’ said Zena as if repeating a prepared lesson. ‘Fortyish, thinning hair, cheap specs, smokes like a chimney. Berlin accent.’

‘Beard?’

‘No beard,’ said Zena. Hastily she added, ‘He must have shaved it off.’ She did not readily abandon her claims.

‘So you’ve spoken with him,’ I said.

‘He’s there every Friday,’ said Werner. ‘He’s a regular. He works at the Soviet Embassy, he told Zena that. He says he’s just a driver.’

‘They’re always drivers,’ I said. ‘That’s how they account for their nice big cars and going wherever they want to go.’ I poured myself some more of Werner’s fruit punch. There was not much of it left, and the bottom of the jug was a tangle of greenery and soggy bits of lemon. ‘Did he talk about books or American films, Zena?’

She swung her legs out of the reclining chair with a display of tanned thigh. I saw the look in Dicky Cruyer’s face as she smoothed her dress. She had that sexy appeal that goes with youth and health and boundless energy. And now she knew she had the right Stinnes her pearly grey eyes sparkled. ‘That’s right. He loves old Hollywood musicals and English detective stories …’

‘Then that’s him,’ I said, without much enthusiasm. Secretly I’d hoped it would all come to nothing and I’d be able to go straight back to London and my home and my children. ‘Yes, that’s “Lenin”; that’s the one who took me down to Checkpoint Charlie when they released me.’

‘What will happen now?’ said Zena. She was short; she only came up to Dicky’s shoulder. Some say short people are aggressive to compensate for their small stature, but look at Zena Volkmann and you might start thinking that aggressive people are made short lest they take over the whole world. Either way Zena was short and the aggression inside her was always bubbling along the edges of the pan like milk before it boils over. ‘What will you do about him?’

‘Don’t ask,’ Werner told her.

But Dicky answered her, ‘We want to talk to him, Mrs Volkmann. No rough stuff, if that’s what you are afraid of.’

I swallowed my fruit punch and got a mouthful of tiny pieces of ice and some lemon pips.

Zena smiled. She wasn’t frightened of any rough stuff; she was frightened of not getting the money for arranging it. She stood up and twisted her shoulders, slowly stretching her arms above her head one after the other in a lazy display of overt sexuality. ‘Do you want my help?’ she said.

Dicky didn’t answer directly. He looked from Zena to Werner and back again and said, ‘Stinnes is a KGB major. That’s too low a rank for the computer to offer much on him. Most of what we know about him came from Bernard, who was interrogated by him.’ A glance at me to stress the unreliability of uncorroborated intelligence from any source. ‘But he’s senior staff in Berlin. So what is he doing in Mexico? Must be a Russian national. What’s his game? What’s he doing in this German club of yours?’

Zena laughed. ‘You think he should have joined Perovsky’s?’ She laughed again.

Werner said, ‘Zena knows this town very well, Dicky. She has aunts and uncles, cousins and a nephew here. She lived here for six months when she first left school.’

‘Where, what, how or why is Perovsky’s?’ said Dicky. He was German Stations Controller. He didn’t like being laughed at, and I could see he was taking a little time getting used to Werner calling him Dicky.

‘Zena is joking,’ explained Werner. ‘Perovsky’s is a big, rather run-down club for Russians near the National Palace. The ground floor is a restaurant open to anyone. It was started after the revolution. The members used to be dukes and counts and people who’d escaped from the Bolsheviks. Now it’s a pretty mixed crowd but the anti-communist line is still de rigueur. The people from the Soviet Embassy give it a wide berth. If a man such as Stinnes went in there and spoke out of turn he might never get out.’

‘Really never get out?’ I said.

Werner turned to look at me. ‘It’s a rough town, Bernie. It’s not all margaritas and mariachis like the travel posters.’

‘But the Kronprinz Club is not so particular about its membership?’ persisted Dicky.

‘No one goes there to talk politics. It’s the only place in town where you can get real German draught beer and good German food,’ explained Werner. ‘It’s very popular. It’s a social club; you get a very mixed crowd there. A lot of them are transients: airline pilots, salesmen, ships’ engineers, businessmen, priests even.’

‘And KGB men?’

‘You Englishmen avoid each other when you are abroad,’ said Werner. ‘We Germans like to be together. East Germans, West Germans, exiles, expatriates, men avoiding tax, men avoiding their wives, men avoiding their creditors, men avoiding the police. Nazis, monarchists, communists, even Jews like me. We like to be together because we are Germans.’

‘Such Germans as Stinnes?’ said Dicky sarcastically.

‘He must have lived in Berlin. His German is as good as Bernie’s,’ said Werner, looking at me. ‘Even more convincing in a way, because he has the sort of strong Berlin accent you seldom hear except in some workers’ bar in the city. It was only when I began to listen to him really carefully that I could detect something that was not quite right in the background of his voice. I’ll bet everyone in the club thinks he’s German.’

‘He’s not here to get a tan,’ said Dicky. ‘A man like that is sent here only for something special. What’s your guess, Bernard?’

‘Stinnes was in Cuba,’ I said. ‘He told me that when we talked together. Security police. I went back to the continuity files and began to guess he was there to give the Cubans some advice when they purged some of the bigwigs in 1970. It was a big shake-up. Stinnes must have been some kind of Latin America expert even then.’

‘Never mind old history,’ said Dicky. ‘What’s he doing now?’

‘Running agents, I suppose. Guatemala is a KGB priority, and it’s not so far from here. Anyone can walk through; the border is just jungle.’

‘I don’t think that’s it,’ said Werner.

I said, ‘The East Germans backed the Sandinista National Liberation Front long before it looked like winning and forming a government.’

‘The East Germans back anybody who might be a thorn in the flesh of the Americans,’ said Werner.

‘But what do you really think he’s doing?’ Dicky asked me.

I was stalling because I didn’t know how much Dicky would want me to say in front of Zena and Werner. I kept stalling. I said, ‘Stinnes speaks good English. Unless the cheque book is a deliberate way of throwing us off the scent, he might be running agents into California. Handling data stolen from electronics and software research firms perhaps.’ I was improvising. I didn’t have the slightest idea of what Stinnes might be doing.

‘Why would London give a damn about that sort of caper?’ said Werner, who knew me well enough to guess that I was bluffing. ‘Don’t tell me London Central put out an urgent call for Stinnes because he’s stealing computer secrets from the Americans.’

‘It’s the only reason I can think of,’ I said.

‘Don’t treat me like a child, Bernard,’ said Werner. ‘If you don’t want to tell me, just say so.’

As if in response to Werner’s acrimony, Zena went across to the fireplace and pressed a hidden bellpush. From somewhere in the labyrinth of the apartment there came the sound of footsteps, and an Indian woman appeared. She had that chin-up stance that makes so many Mexicans look as if they are ready to balance a water jug on their heads, and her eyes were half closed. ‘I knew you’d want to sample some Mexican food,’ said Zena. Personally it was the last thing I’d ever want to sample, but without waiting to hear our response she told the woman we would sit down immediately. Zena used her poor Spanish with a fluent confidence that made it sound better. Zena did everything like that.

‘She can understand German perfectly and a certain amount of English too,’ said Zena after the woman had gone. It was a warning to guard our tongues. ‘Maria has worked for my aunt for over ten years.’

‘But you don’t talk to her in German,’ said Dicky.

Zena smiled at him. ‘By the time you’ve said tortillas, tacos, guacamole and quesadillas, and so on, you might as well add por favor and get it over with.’

It was an elegant table, shining with solid-silver cutlery, hand-embroidered linen and fine cut-glass. The meal had obviously been planned and prepared as part of Zena’s pitch for a cash payment. It was a good meal, and not too damned ethnic, thank God. I have a very limited capacity for the primitive permutations of tortillas, bean-mush and chillies that numb the palate and sear the insides from Dallas to Cape Horn. But we started with grilled lobster and cold white wine, and not a refried bean in sight.

The curtains were drawn back so that air could come in through the open windows, but the air was not cool. The cyclone out in the Gulf had not moved nearer the coast, so the threatened storms had not come but neither had much drop in temperature. By now the sun had gone down behind the mountains that surround the city on every side, and the sky was mauve. Pin-pointed like stars in a planetarium were the lights of the city, which stretched all the way to the foothills of the distant mountains until like a galaxy they became a milky blur. The dining room was dark; the only light came from tall candles that burned brightly in the still air.

‘Sometimes London Central can get in ahead of our American friends,’ said Dicky, suddenly spearing another grilled lobster tail. Had he really spent so long thinking up a reply for Werner? ‘It would give us negotiating power in Washington if we had some good material about KGB penetration of anywhere in Uncle Sam’s backyard.’

Werner reached across the table to pour more wine for his wife. ‘This is Chilean wine,’ said Werner. He poured some for Dicky and for me and then refilled his own glass. It was Werner’s way of telling Dicky he didn’t believe a word of it, but I’m not sure Dicky understood that.

‘It’s not bad,’ said Dicky, sipping, closing his eyes and tilting his head back to concentrate all his attention on the taste. Dicky fancied his wine expertise. He’d already made a great show of sniffing the cork. ‘I suppose, with the peso collapsing, it will be more and more difficult to get any sort of imported wine. And Mexican wine is a bit of an acquired taste.’

‘Stinnes only arrived here two or three weeks ago,’ said Werner doggedly. ‘If London Central is interested in Stinnes, it won’t be on account of anything he might be planning to do in Silicon Valley or in the Guatemala rain forest; it will be on account of all the things he did in Berlin during the last two years.’

‘Do you think so? said Dicky, looking at Werner with friendly and respectful interest, like a man who wanted to learn something. But Werner could see through him.

‘I’m not an idiot,’ said Werner, using the unemotional tone but exaggerated clarity with which a man might specify decaffeinated coffee to an inattentive waiter. ‘I was dodging KGB men when I was ten years old. Bernie and I were working for the department when the Wall was built in 1961 and you were still at school.’

‘Point taken, old boy,’ said Dicky with a smile. He could afford to smile; he was two years younger than either of us, with years’ less time in the department, but he’d got the coveted job of German Stations Controller against tough competition. And – despite rumours about an imminent reshuffle in London Central – he was still holding on to it. ‘But the fact is that the people in London don’t tell me every last thing they have in mind. I’m just the chap chipping away at the coal-face, right? They don’t consult me about building new nuclear power stations.’ He poured some warm butter over his last piece of lobster with a care that suggested he had no other concern in his mind.

‘Tell me about Stinnes,’ I said to Werner. ‘Does he come along to the Kronprinz Club trailing a string of KGB zombies? Or does he come on his own? Does he sit in the corner with his big glass of Berliner Weisse mit Schuss, or does he sniff round to see what he can ferret out? How does he behave, Werner?’

‘He’s a loner,’ said Werner. ‘He probably would never have spoken to us in the first place except that he mistook Zena for one of the Biedermann girls.’

‘Who are the Biedermann girls?’ said Dicky. After the remains of the lobster course had been removed, the Indian servant brought an elaborate array of Mexican dishes: refried beans, whole chillies and the tortilla in its various disguises: enchiladas, tacos, tostadas and quesadillas. Dicky paused for long enough to have each one identified and described but he took only a tiny portion on his plate.

‘Here in Mexico the chilli has sexual significance,’ said Zena, directing the remark to Dicky. ‘The man who eats hot chillies is thought to be virile and strong.’

‘Oh, I love chillies,’ said Dicky, his tone of voice picking up the hint of mockery that was to be detected in Zena’s remark. ‘Always have had a weakness for chillies,’ he said, as he reached for a plate on which many different ones were arranged. I glanced at Werner who was watching Dicky with interest. Dicky looked up to see Werner’s face. ‘It’s the tiny, dark-coloured ones that blow your head off,’ Dicky explained. He took a large, pale-green cayenne and smiled at our doubting faces before biting a section from it.

There was a silence after Dicky’s mouth closed upon the chilli. Everyone except Dicky knew he’d mistaken the cayenne for one of the very mild aji chillies from the eastern provinces. And soon Dicky knew it too. His face went red, his mouth half opened, and tears shone in his eyes. He fought against the pain but he had to take it from his mouth. Then he fed himself lots and lots of plain rice.

‘The Biedermanns are a wealthy Berlin family,’ said Zena, carrying on as if she’d not noticed Dicky’s desperate discomfort. ‘They are well known in Germany. They have interests in German travel companies. The newspapers said the company had borrowed millions of dollars to build a holiday village in the Yucatan peninsula. It’s never been finished. Erich Stinnes thought I looked just like the younger sister Poppy who’s always in the newspaper gossip columns.’

There was a silence as we all waited for Dicky to recover. Finally he leaned back in his chair and managed a rueful smile. There was perspiration on his forehead and he was breathing with his mouth open. ‘Do you know these Biedermann people, Bernard?’ said Dicky. He sounded hoarse.

‘Have an avocado,’ said Werner. ‘They are very soothing.’ Dicky took an avocado pear from the bowl and began to eat some.

I said, ‘When my father was attached to the military government in Berlin he gave old Biedermann a licence to start up his bus service again. It was one of the first after the war; it started the family fortune, I suppose. Yes, I know them. Poppy Biedermann was having dinner at Frank Harrington’s the last time I was in Berlin.’

Dicky was eating the avocado quickly with his teaspoon, using it to heal the burning in his mouth. ‘That was bloody hot,’ he confessed finally.

‘There’s no way you can be sure which are hot and which are mild,’ said Zena in a gentle tone that surprised me. ‘They cross-pollinate; even on the same plant you can get fiery ones and mild ones.’ She smiled.

‘Could these Biedermann people be interesting to Stinnes?’ said Dicky. ‘For instance, might they own a factory that’s making computer software in California? Or something like that? What do you know about that, Bernard?’

‘Even if that was the case, no point in making contact with the boss,’ I said. I could see that Dicky had focused on the idea of Silicon Valley and it was not going to be easy to shake him off it. ‘The approach would be made to someone in the microchip laboratory. Or someone doing the programs for the software.’

‘We need to know the current situation from the California end,’ said Dicky with a sigh. I knew that sigh. Dicky was just getting me prepared for a sweaty week in Mexico City while he went to swan around in southern California.

‘Talk to the Biedermanns,’ I said. ‘It’s easier.’

‘Stinnes asked about the Biedermanns,’ said Werner. ‘He asked if I knew them. I used to know Paul very well, but I told Stinnes I knew the family only from the newspapers.’

‘Werner, you didn’t tell me you know the Biedermanns,’ Zena interjected excitedly. ‘They are always in the gossip columns. Poppy Biedermann is beautiful. She just got divorced from a millionaire.’

Dicky looked at me and said, ‘Better you talk to Biedermann. No sense in me showing my face. Keep it informal. Find out where he is; go and see him. Would you do that, Bernard?’ It was an order in the American style: disguised to sound like a polite inquiry.

‘I can try.’

Dicky said, ‘I don’t want to channel this through London, or get Frank Harrington to introduce us, or the whole world will know we’re interested.’ He poured himself some iced water and sipped a little. He was recovering some of his composure, when suddenly he screamed, ‘You bastard!’, his eyes fixed on poor Werner and his head thrust forward low over the table. Werner looked perplexed until Dicky, still leaning forward with his head almost on his plate, yelled, ‘That bloody cat.’

‘Cherubino, you’re very naughty,’ said Zena mildly as she bent down to disengage the cat’s claws from Dicky’s leg. But by that time Dicky had delivered a kick that sent Cherubino across the room with a howl of pain.

Zena stood up, flushed and furious. ‘You’ve hurt her,’ she said angrily.

‘I’m awfully sorry,’ said Dicky. ‘Just gave way to a reflex action, I’m afraid.’

Zena said nothing. She nodded and left the room in search of the cat.

‘Paul Biedermann is approachable,’ said Werner, to cover the awkward silence. ‘He arranged a bank guarantee for me last year. It cost too much but he came through when I needed him. He has an office in town and a house on the coast at Tcumazan.’ Werner looked at the door but there was no sign of Zena.

‘There you are, then,’ said Dicky. ‘Get on to him, Bernard.’

I knew Paul Biedermann too; I’d exchanged hellos with him recently in Berlin and hardly recognized him. He’d smashed himself up driving a brand-new Ferrari back to Mexico from a drunken party in Guatemala City. At 120 miles an hour the car had gone deep into the roadside jungle. It took the rescuers a long time to find him, and a long time to cut him free. The girl with him had been killed, but the inquiry had glossed over it. Whatever the truth of it, now one of his legs was shorter than the other and his face bore the scar tissue of over a hundred neat stitches. These infirmities didn’t help me overcome my dislike of Paul Biedermann.

‘Just a verbal report. Nothing in writing for the time being. Not you, not me, not Biedermann.’ Dicky was keeping all the exits covered. Nothing in writing until Dicky heard the results and arranged the blames and the credits with godlike impartiality.

Werner shot me a glance. ‘Sure thing, Dicky,’ I said. Dicky Cruyer was such a clown at times, but there was another, very clever Dicky who knew exactly what he wanted and how to get it. Even if it did sometimes mean giving way to one of those nasty little reflex actions.

3 (#u9c0e2a0f-d19c-58b3-a995-31eaa329af39)

The jungle stinks. Under the shiny greenery, and the brightly coloured tropical flowers that line the roadsides like the endless window displays of expensive florists, there is a squelchy mess of putrefaction that smells like a sewer. Sometimes the road was darkened by vegetation that met overhead, and strands of creeper fingered the car’s roof. I wound the window closed for a moment, even though the air-conditioning didn’t work.

Dicky wasn’t with me. Dicky had flown to Los Angeles, giving me a contact phone number that was an office in the Federal Building. It was not far from the shops and restaurants of Beverly Hills, where by now he would no doubt be sitting beside a bright blue pool, clasping an iced drink, and studying a long menu with that kind of unstinting dedication that Dicky always gave to his own welfare.

The big blue Chevvy he’d left for me was not the right sort of car for these miserable winding jungle tracks. Imported duty-free by Tiptree, Dicky’s embassy chum, it didn’t have the hard suspension and reinforced chassis of locally bought cars. It bounced me up and down like a yo-yo in the potholes, and there were ominous scraping sounds when it hit the bumps. And the road to Tcumazan was all pot-holes and bumps.

I’d started very early that morning, intending to cross the Sierra Madre mountain range and be in a restaurant lingering over a late lunch to miss the hottest part of the day. In fact I spent the hottest part of the day crouched on a dusty road, with an audience of three children and a chicken, while I changed the wheel of a flat tyre and cursed Dicky, Henry Tiptree and his car, London Central and Paul Biedermann, particularly Biedermann for having chosen to live in such a Godforsaken spot as Tcumazan, Michoacan, on Mexico’s Pacific coast. It was a place to go only for those equipped with private planes or luxury yachts. Getting there from Mexico City in Tiptree’s Chevvy was not recommended.

It was early evening when I reached the ocean at a village variously called ‘Little San Pedro’ or ‘Santiago’, according to who directed you. It was not on the map under either name; even the road leading there was no more than a broken red line. Santiago consisted only of a rubbish heap, some two dozen huts constructed of mud and old corrugated iron, a prefabricated building surmounted by a large cross and a cantina with a green tin roof. The cantina was held together by enamelled advertisements for beer and soft drinks. They had been nailed, sometimes upside-down or sideways, wherever cracks had appeared in the walls. More adverts were urgently needed.

The village of Santiago is not a tourist resort. There were no discarded film packets, paper tissues or vitamin containers to be seen littering the streets or even on the dump. From the village there was not even a view of the ocean; the water-front was out of sight beyond a flight of wide stone steps that led nowhere. There were no people in sight; just animals – cats, dogs, a few goats and some fluttering hens.

Alongside the cantina a faded red Ford sedan was parked. Only after I pulled in alongside did I see that the Ford was propped up on bricks and its inside gutted. There were more hens inside it. As I locked up the Chevvy, people appeared. They were coming from the rubbish heap: a honeycomb of tiny cells made from boxes, flattened cans and oil-drums. It was a rubbish heap, but not exclusively so. No women or children emerged from the heap; just short, dark-skinned men with those calm, inscrutable faces that are to be seen in Aztec sculpture: an art form obsessed with brutality and death.

The smell of the jungle was still there, but now there was also the stink of human ordure. Dogs – their coats patchy with the symptoms of mange – smelled each other and prowled around the garbage. One outside wall of the cantina was entirely covered with a crudely painted mural. The colours had faded but the outline of a red tractor carving a path through tall grass, with smiling peasants waving their hands, suggested that it was part of the propaganda for some long-forgotten government agricultural plan.

It was still very hot, and my damp shirt clung to me. The sun was sinking, long shadows patterned the dusty street, and the electric bulbs which marked the cantina doorway made yellow blobs in the blue air. I stepped over a large mongrel dog that was asleep in the doorway and pushed aside the small swing-doors. There was a fat, moustachioed man behind the bar. He sat on a high stool, his head tipped forward on to his chest as if he was sleeping. His feet were propped high on the counter, the soles of his boots pushed against the drawer of the cash register. When I entered the bar he looked up, wiped his face with a dirty handkerchief and nodded without smiling.

There was an unexpected clutter inside; a random assortment of Mexican aspirations. There were sepia-coloured family photos, the frames cracked and wormeaten. Two very old Pan-American Airways posters depicted the Swiss Alps and downtown Chicago. Even the girlie pictures revealed the ambivalent nature of machismo: Mexican film stars in decorous swimsuits and raunchy gringas torn from American porno magazines. In one corner there was a magnificent old juke-box but it was for decoration only; there was no machinery inside it. In the other corner there was an old oil-drum used as a urinal. The sound of Mexican music came quietly from a radio balanced over the shelf of tequila bottles that, despite their varying labels, looked as if they’d been refilled many times from the same jug.

I ordered a beer and told the cantinero to have one himself. He got two bottles from the refrigerator and poured them both together, holding two bottles in one hand and two glasses in the other. I drank some beer. It was dark, strong and very cold. ‘Salud y pesetas,’ said the bartender.

I drank to ‘health and money’ and asked him if he knew anyone who could mend my punctured tyre. He didn’t answer immediately. He looked me up and down and then craned his neck to see my Chevvy, although I had no doubt he’d watched me arrive. There was a man who could do such work, he said, after giving the matter some careful thought. It might be arranged, but the materials for doing such jobs were expensive and difficult to obtain. Many of the people who claimed such expertise were clumsy, inexpert men who would fix patches that, in the hot sun and on the bad roads, would leak air and leave a traveller stranded. The brakes, the steering and the tyres: these were the vital parts of a motor car. He himself did not own a car but one of his cousins had a car and so he knew about such things. And on these roads a stranded traveller could meet bad people, even bandidos. For a puncture I needed someone who could make such a vital repair properly.

I drank my beer and nodded sympathetically. In Mexico this was the way things were done; there was nothing to be gained by interrupting his explanation. It was for this that he got his percentage. He shouted loudly at the faces looking in through the doorway and they went away. No doubt they went to tell the man who fixed flats that his lucky day had finally come.

We each had another beer. The cantinero’s name was Domingo. Awakened by the sound of the cash register, the dog looked up and growled. ‘Be quiet, Pedro,’ said the bartender and edged a small plate of chillies across the counter towards me. I declined. I left some money on the counter in front of me when I asked him how far it was to the Biedermann house. He looked at me quizzically before answering. It was a long, long way by road, and the road was very bad. Rain had washed it out in places. It always did at this time of year. On a motorcycle or even in a jeep it was possible. But in my Chevvy, which Domingo called my double bed – cama matrimonial – there would be no chance of driving there. Better to take the track and go on foot, the way the villagers went. It would take no more than five minutes, maybe ten. Fifteen minutes at the most. If I was going up to the Biedermann house everything was okay.

Mr Biedermann owed me some money, I explained. Might I encounter trouble collecting it?

Domingo looked at me as if I’d just arrived from Mars. Didn’t I know that Señor Biedermann was muy rico, muy, muy rico?

‘How rich?’ I asked.

‘For no one does what he gives seem little, or what he has seem much,’ said the bartender, quoting a Spanish proverb. ‘How much does he owe you?’

I ignored his question. ‘Is he up at the house now?’ I fiddled with the money on the counter.

‘He’s not an easy man to get along with,’ said Domingo. ‘Yes, he’s up at the house. He’s there all alone. He can’t get anyone to work for him any more, and his wife is seldom with him nowadays. He even does his own laundry. No one round here will work for him.’

‘Why?’

Domingo put the tip of his thumb in his mouth and upended his fist to show me that Biedermann was a heavy drinker. ‘He can get through two or three bottles of it when he’s in one of his rages. Tequila, mezcal, aguardiente or imported whisky, it’s all the same to him once he starts guzzling. Then he gets rough with anyone who won’t drink with him. He hit one of the workmen mending the floor; the youngster had to go to the dispensary. Now the men refuse to finish the work.’

‘Does he get rough with people who collect money?’ I asked.

Domingo didn’t smile. ‘When he is not drinking he is a good man. Maybe he has troubles; who knows?’

We went back to talking about the car. Domingo would arrange for the repair of my tyre and look after the car. If the beer-delivery truck arrived it would perhaps be possible to deliver the car to the Biedermann house. No, I said, it was better if the car remained where it was; I’d seen a few beer-delivery drivers on the road.

‘Is the track to the Biedermann house a good one?’ I asked. I pushed some money to him.

‘Whatever path you take, there is a league of bad road,’ said Domingo solemnly. I hoped it was just another proverb.

I got my shoulder-bag from the car. It contained a clean shirt and underclothes, swimming trunks and towel, shaving kit, a big plastic bag, some string, a flashlight, some antibiotics, Lomatil and a half-bottle of rum for putting on wounds. No gun. Mexico is not a good place for gringos carrying guns.

I took the path that Domingo had shown me. It was a narrow track made by workers going between the crops and the village. It climbed steeply past the flight of stone steps that Domingo said was all that remained of an Aztec temple. It was sunny up here while the valleys were swallowed in shadow. I looked back to see the villagers standing round the Chevvy, Domingo parading before it in a proprietorial manner. Pedro cocked his leg to pee on the front wheel. Domingo looked up, as if sensing that I was watching, but he didn’t wave. He wasn’t a friendly man; just talkative.

I rolled down my shirt-sleeves against the mosquitoes. The track led along the crest of a scrub-covered hill. It skirted huge rocks and clumps of yucca, with sharp leaves that thrust into the skyline like swords. It was hard going on the stony path and I stopped frequently to catch my breath. Through the scrub-oak and pines I could see the purple mountains over which I’d driven. There were many mountains to the north. They were big, volcanic-looking, their distance – and thus their exact size – unresolved, but in the clear evening air everything looked sharp and hard, and nearer than it really was. Now and again, as I walked, I caught sight of the motor road that skirted the spur and came in a long detour up the coast. It looked like a damned bad road; I suppose only the Biedermanns ever used it.

It took me nearly an hour to get to the Biedermann house. I was almost there before I came over the ridge and caught sight of it. It was a small house of modern design, built of decorative woods and matt black steel, its foundations set into the rocks upon which the Pacific Ocean dashed huge breakers. One side of the house was close to a patch of jungle that went right to the water’s edge. There was a little pocket of sandy beach there, and from it ran a short wooden pier. There was no boat in sight, no cars anywhere, and the house was dark.

A chainlink fence that surrounded the grounds of the house had been damaged by a landslide, and the wire was cut and bent up to provide a gap big enough to get through. The makeshift track continued after the damaged fence and ended in a steep scramble up to a patch of grass. There were flowers here; white and pink camellias and floribunda and the inevitable purple bougainvillaea. Everything had been landscaped to hide the place where a new macadam road ended at the double garage and shaded carport. But there were no cars to be seen, and wooden crates blocked the white garage doors.

So Paul Biedermann had taken flight despite the appointment I’d made with him. I was not surprised. There had always been a streak of cowardice in him.

I had no difficulty getting inside the house. The front door was locked but a ladder left on the grass reached to one of the balconies. The sliding window, secured only by a plastic clip, was easy enough to force.

There was still enough daylight coming through the window for me to see that the master bedroom had been tidied and cleaned with that rigorous care that is the sign of leave-taking. The huge double bed was stripped of linen and covered with clear plastic covers. Two small carpets were rolled up and sealed into bags that would protect them from termites. Torn up and in the waste-paper basket I found half a dozen Mexico City airport luggage tags dating from some previous journey, and three new and unused airline shoulder-bags not required for the next. The sort of airline bags that come free with airline tickets were not something that the Biedermanns let their servants carry. I stood listening, but the house was completely silent. There was only the sound of the big Pacific Ocean waves battering against the rocks below the house and roaring their displeasure.

I opened one of the wardrobes. It smelled of moth repellent. There were clothes there: a man’s cream-coloured linen suits, brightly coloured pants and sweaters, handmade shoes – treed and in shoe-bags embroidered ‘P.B.’ – and drawers filled with shirts and underclothes.

In the other wardrobe, a woman’s dresses, expensive lingerie folded into tissue paper and a multitude of shoes of every type and colour. On the dressing table there was a photo of Mr and Mrs Biedermann in swimsuits standing on a diving board and smiling self-consciously. It had been taken before the car accident.

The three guest bedrooms on the top floor – each with separate balcony overlooking the ocean and private bathroom – had all been stripped bare. Inside the house, a gallery that gave access to the bedrooms was open on one side to overlook the big lounge downstairs. All the furniture was covered in dustsheets, and to one side of the lounge there was a bucket of dirty water, a trowel, some adhesive and dirty rags marking a place where a large section of flooring was being retiled.

Only when I got to Biedermann’s study, built to provide a view of the whole coastline, was there any sign of recent occupancy. It was an office; or, more exactly, it was a room furnished with that special sort of luxury furniture that can be tax-deducted as office equipment. There was a big puffy armchair, a drinks cabinet, and a magnificent wood-inlay desk. In the corner was that sort of daybed that Hollywood calls a ‘casting couch’. On it there were blankets roughly folded and a soiled pillow. A big waste-bin contained computer print-out and some copies of the Wall Street Journal. More confidential print-out was now a tangle of paper worms in the clear plastic bag of the shredder. But the notepads were blank, and the expensive desk diary – the flowers of South America, one for every week of the year in full colour, printed in Rio de Janeiro – had never been used. There were no books apart from business reference books and phone and telex directories. Paul Biedermann had never been much of a reader at school but he’d always been good at counting.

I tried the electric light but it did not work. A house built out here on the edge of nowhere would be dependent upon a generator operating only when the house was occupied. By the time I had searched the house and found no one, the daylight was going fast. The sea had turned the darkest of purples and the western skyline had almost vanished.

I went back up to the top floor and chose the last guest room along the gallery as a place to spend the night. I found a blanket in the wardrobe and, choosing one of the plastic-covered beds, I covered myself against the cold mist that rolled in off the sea. It soon became too dark to read and, as my interest in the Wall Street Journal waned, I drifted off to sleep, lulled by the sound of the waves.

It was 2.35 when I was awakened by the car. I saw its lights flashing over the ceiling long before I heard its engine. At first I thought it was just a disturbed dream, but then the bright patch of light flashed across the ceiling again and I heard the diesel engine. It never struck me that it might be Paul Biedermann or any of the family coming home. I knew instinctively that there was danger.

I slid open the glass door and went outside on to the balcony. The weather had become stormy. Thin ragged clouds raced across the moon, and the wind had risen so that its roar was confused with the sound of the breakers on the rocks below. I watched the car. The headlights were high and close together, a configuration that suggested some Jeep-like vehicle, as did the way it negotiated the bad road. It was still going at speed as it swung round the back to the garage area. The driver had been here before.

There were two voices; one of the men had a key to the front door. I went through the guest bedroom and crouched on the interior gallery so that I could hear them speaking in the lounge below.

‘He’s run away,’ said one voice.

‘Perhaps,’ said the other, as if he didn’t care. They were speaking in German. There was no mistaking the Berlin accent of Erich Stinnes, but the other man’s German had a strong Russian accent.

‘His car is not here,’ said the first man. ‘What if the Englishmen arrived before us and took him off with them?’

‘We would have passed them on the road,’ said Stinnes. He was perfectly calm. I heard the sound of him putting his weight on to the big sofa. ‘That’s better.’ A sigh. ‘Take a drink if you want it. It’s in the cabinet in his study.’

‘That stinking jungle road. I could do with a bath.’

‘You call that jungle?’ said Stinnes mildly. ‘Wait till you go over to the east coast. Wait until you go across to the training camp where the freedom fighters are trained, and cut your way through some real tropical rain forest with a machete, and spend half the night digging chiggers out of your backside. You’ll find out what a jungle is like.’

‘What we came through will do for me,’ said the first man.

I raised my head over the edge of the gallery until I could see them. They were standing in the moonlight by the tall window. They were wearing dark suits and white shirts and trying to look like Mexican businessmen. Stinnes was about forty years old: my age. He had shaved off the little Leninstyle beard he’d had when I last saw him but there was no mistaking his accent or the hard eyes glittering behind the circular gold-rimmed spectacles.

The other man was much older, fifty at least. But he was not frail. He had shoulders like a wrestler, cropped head and the restless energy of the athlete. He looked at his watch and then out of the window and then walked over to the place where the tiles were being repaired. He kicked the trowel so that it went skidding across the floor and hit the wall with a loud noise.

‘I told you to have a drink,’ said Stinnes. He did not defer to the other man.

‘I said you should frighten Biedermann. Well, you’ve frightened him all right. It looks as if you’ve frightened him so much that he’s cleared out of here. That’s not what they wanted you to do.’

‘I didn’t frighten him at all,’ said Stinnes calmly. ‘I didn’t take your advice. He’s already too frightened. He needs reassurance. But he’ll surface sooner or later.’

‘Sooner or later,’ repeated the elder man. ‘You mean he’ll surface after you’ve gone back to Europe and be someone else’s problem. If it was left to me, I’d make Biedermann a number-one priority. I’d alert every last KGB team in Central America. I’d teach him that an order is an order.’

‘Yes, I know,’ said Stinnes. ‘It’s all so easy for you people who sit at desks all your life. But Biedermann is just one small part of a complicated plan … and neither of us knows exactly what the plan is.’

It was a patronizing reproach, and the elder man’s soft voice did not conceal the anger in him. ‘I say he’s the weak link in the chain, my friend.’

‘Perhaps he is supposed to be just that,’ said Stinnes complacently. ‘One day maybe the Englishwoman will put you in charge of one of her crazy schemes, and then you’ll be able to ignore orders and show everyone what a clever man you are in the field. But until that time you’ll do things the way you’re ordered to do them, no matter how stupid it all seems.’ He got to his feet. ‘I’ll have a drink, even if you don’t want one. Biedermann has good brandy.’

Stinnes passed below me out of sight and I heard him go into the study and pour drinks. When he returned he was carrying two glasses. ‘It will calm you, Pavel. Have patience; it will work out all right. You can’t rush these things. You’ll have to get used to that. It’s not like chasing Moscow dissidents.’ He gave the elder man a glass and they both drank. ‘French brandy. Schnapps and beer are not worth drinking unless they come from a refrigerator.’ He drank. ‘Ah, that’s better. I’ll be glad to be back in Berlin, if only for a brief spell.’

‘I was in Berlin in 1953,’ said the elder man. ‘Did you know that?’

‘So was I,’ said Stinnes.

‘In ’53? Doing what?’

Stinnes chuckled. ‘I was only ten years old. My father was a soldier. My mother was in the army too. We were all kept in the barracks during the disturbances.’

‘Then you know nothing. I was in the thick of it. The bricklayers and builders working on those Stalinallee sites started all the trouble. It began as a protest against a ten per cent increase in work norms. They marched on the House of Ministries in Leipzigerstrasse and demanded to see the Party leader, Ulbricht.’ He laughed. It was a low, manly laugh. ‘But it was the poor old Mining Minister who was sent out to face them. I was twenty. I was with the Soviet Control Commission. My chief dressed me up like a German building worker and sent me out to mix with the mob. I was never so frightened in all my life.’

‘With your accent you had every cause to be frightened,’ said Stinnes.

His colleague was not amused. ‘I kept my mouth shut; but I kept my ears open. That night the strikers marched across to the RIAS radio station in West Berlin and wanted their demands to be transmitted over the Western radio. Treacherous German swine.’