London Match

Len Deighton

Long-awaited reissue of the final part of the classic spy trilogy, GAME, SET and MATCH, when the Berlin Wall divided not just a city but a world.The spy who’s in the clear doesn’t exist…Bernard Samson hoped they’d put Elvira Miller behind bars. She said she had been stupid, but it didn’t cut any ice with Bernard. She was a KGB-trained agent and stupidity was no excuse.There was one troubling thing about Mrs Miller’s confession – something about two codewords where there should have been one. The finger of suspicion pointed straight back to London.And that was where defector Erich Stinnes was locked up, refusing to say anything.Bernard had got him to London; now he had to get him to talk…

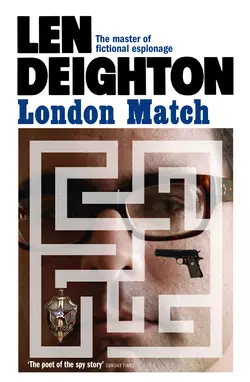

Cover designer’s note (#u86bf1dc7-af96-5a24-ac9e-e85bd184c6d3)

On reading a synopsis for one of Len Deighton’s trilogies I was immediately taken by the sentence, ‘And we are back in the mazes of Secret Service mystery and intrigue – mazes that now lead into Samson’s own tangled past.’ There I found my concept for the London Match cover! I would place him within the maze, trapped, with pathways leading to danger, in the form of the gun, and perhaps worse, the KGB, represented here by one of the agency’s badges – this Soviet-era icon features the hammer and sickle together with Cyrillic letters for ‘KGB’ and ‘USSR’.

Some years ago I was commissioned to design a calendar for a leading British sign company. I decided to use the many door numbers that I had photographed during my travels around the world, showing a different number for each day of the year. I contacted the Prime Minister’s press secretary, who kindly gave me permission to photograph the door of Number 10 Downing Street. This photograph has once again found a good use adorning the back cover of this book of intrigue in London’s Whitehall.

At the heart of every one of the nine books in this triple trilogy is Bernard Samson, so I wanted to come up with a neat way of visually linking them all. When the reader has collected all nine books and displays them together in sequential order, the books’ spines will spell out Samson’s name in the form of a blackmail note made up of airline baggage tags. The tags were drawn from my personal collection, and are colourful testimony to thousands of air miles spent travelling the world.

Arnold Schwartzman OBE RDI

LEN DEIGHTON

London Match

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Hutchinson & Co. (Publishers) Ltd 1985

Copyright © Pluriform Publishing Company BV 1985

Introduction copyright © Pluriform Publishing Company BV 2010

Cover designer’s note © Arnold Schwartzman 2010

Cover design and photography © Arnold Schwartzman 2010

Len Deighton asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008125004

Ebook Edition © March 2015 ISBN: 9780007387205

Version: 2017-05-23

Contents

Cover (#u983afc60-45d7-5dc6-9071-3b08e3ea2ead)

Cover Designer’s Note (#u8b31242f-e538-5f84-a00e-a7966b1181ce)

Title Page (#u18b3be76-f459-5ac1-9d07-c79da49159a0)

Copyright (#u734e3f95-80cb-5d61-828e-c91971091c5c)

Introduction (#uc1fc7ff0-0fca-5440-b06c-c3d9e54f1c76)

Chapter 1 (#u8bab3e98-690e-53fc-ab40-d978a935770d)

Chapter 2 (#u40b9bd72-7f27-5ef0-8482-382e6341d7b2)

Chapter 3 (#u89a30654-55af-593b-9277-60bc2369cafa)

Chapter 4 (#ua8a59788-7840-5699-964a-81f0f7ed17c0)

Chapter 5 (#ude1af3aa-519d-550f-9fb6-a0fc6e58b6bd)

Chapter 6 (#u8e6e6695-96b3-5be0-837a-0082ec42cd5f)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Further Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By Len Deighton (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Introduction (#u86bf1dc7-af96-5a24-ac9e-e85bd184c6d3)

Despite its title, London Match is a book largely about Berlin. The Berliners were familiar to me; their general demeanour; their humour closely resembled the cocky Londoners I grew up among. But the physical texture of Berlin is not like London, which is generously ventilated with parks and squares. Berlin is martial and monolithic and always has been. Berlin is like no other town I have ever seen. It fascinates me, and in many ways it became my home but there is no denying its grim grey ugliness. Its wide streets make the unrelenting vista of apartment blocks seem less oppressive. But only slightly so. To cope with overcrowding, the great apartment blocks were built one behind the other. Some tenements were so vast that there were three or four Hinterhöfe – or back courtyards. These were so small that sunlight was lost before it could find its way into the hintermost yard. In the early thirties it was calculated that more than ninety per cent of Berlin’s population were packed tightly into these grim five-storey buildings. Berlin, expanded by reparations of the Franco–Prussian War, was designed to absorb the impoverished agricultural workers who came flooding from the Eastern lands seeking jobs in the factories and sweatshops.

Ugly, dirty and crowded – sweaty in summer and freezing in winter – what is the secret attraction of this town? The population is a part of it. The endless upheavals of the past century have brought a weird mixture of people to a town that has never found its place in history. And like many others regularly brought to the brink of despair, Berliners have learned how to smile. Always from the east, there came to the city a steady stream of people looking for shelter. Persecution drove many, and revolution brought more. Painters and writers such as George Grosz and Alfred Döblin provided a lasting record of a town where skirts were short and pounding jazz was at its most frenetic. Emperor Wilhelm had disappeared into exile and Czarist Dukes were working as nightclub doormen. Sex, psychology and cycle racing were major obsessions, and money was singularly meaningful in a town where the currency had collapsed to zero time and time again.

After the debacle in the summer of 1945 the Red Army occupied the Eastern half of the city while fugitives of every kind sought a hazardous sanctuary in its West. But there was no sanctuary; just new kinds of danger. Only the agile survived. Some were saints and some were despicable but most of them were somewhere in between. I came to know many of Berlin’s dodgers and drifters but I had no right to judge them and didn’t attempt to do so. This was not just because I was a writer. Many years ago, I resolved never to resort to the poison of hatred. I had found that hatred wears and destroys the hater and it erects a barrier to understanding that makes objectivity impossible. This had an effect on my writing. Critics remarked upon the absence of villains and the neutrality of the storyteller. I didn’t mind this verdict. Researching my World War Two history books had already brought me into contact with a wide range of veterans of all ranks and specializations, and from both sides of the fighting. By the time I came to write London Match I was being discreetly approached by jaded warriors of the Cold War. These included people at many different levels, with many different motives; some in no way benign. I learned a new sort of discretion. The anecdotal material built up quickly and I soon had enough material for a hundred Bernard Samson books. But books are not assemblies of anecdotes, no matter how dramatically effective, disgusting, inhuman or deeply moving, the stories proved. The nine Bernard Samson stories would stand or fall on the credibility of the principal characters and ever-changing social situation to which they were exposed. Here was a boardroom drama in which the consequence of being ‘outvoted’ was not losing a job, but losing your life. It was an elderly Silesian building contractor who said that to me. He wasn’t talking about my books; he was talking about the dangerous cross-border life he had survived in his youth. He had been ‘out voted’ without losing his life, but some of the fingernails of his left hand were missing.

The times in which our story is set were times of confusion. Western Europe had been saved by the spilled blood of young Americans, and there was widespread gratitude, admiration and respect for the nation which was now the world’s most powerful and most economically successful. But Eastern Europe was ruled by Stalin; a brutal despot who had at one time befriended Hitler and his criminal regime. The Red Army which had invaded Poland and the Baltic states was now used to snuff out any glimmer of democracy in a vast area stretching from Vladivostok to the edge of West Germany. For most people in the West there was a simple distinction between good and evil, between the free societies and the totalitarian ones. But not for everyone. As the nineteen sixties became the seventies there was a slow shift in loyalties. No one openly disputed the existence of Soviet Russia’s secret police, its gulags and the number of its citizens who disappeared each year. But the communist propaganda machine persuaded many Europeans that America’s military presence, and the weapon technology that discouraged Moscow’s territorial ambitions, was as much of a threat as the armies of the USSR. Such people – many of them academics, writers, intellectuals and politicians – liked to proclaim that the USA was just as bad as the USSR. Some said it was worse. Some said that Marxist theory provided a promise of world order that was inevitable and desirable.

The advanced world was split into two distinct halves. The dividing line was drawn down through the middle of Germany. Grimly determined Marxists of the DDR built a barrier against the Federal Republic and killed any of their compatriots trying to join the exuberant capitalists on the other side of it. For added complexity, the town of Berlin had been created as an island in the middle of the DDR and this island was neatly divided between the two combatants. Berlin became the place where the fate of the world would be decided. What writer could resist such a fateful and bloody forum, or should that be amphitheatre? Not I. This was not old history. This was now. This was happening all around me and it was happening to people I knew well.

The fires of the misnamed Cold War did not burn with consistent fury. There were times when both sides toned down their activities for weeks at a time. Sometimes this was a result of orders due to a relaxing of attitudes between Moscow, London and Washington. But more often it was because the people at the sharp end of the conflict wearied, or needed rehabilitation after some particularly destructive blow. I have tried to reflect the way in which this happened. And while the nine books are not in any way an attempt to write Cold War history, I have linked the episodes to actual happenings. And, because writers of fiction are able to test the boundaries of secrecy, I was able to use material generously passed to me by those who were gagged by over-assertive officialdom. I put my thanks on record.

Len Deighton, 2010

1 (#u86bf1dc7-af96-5a24-ac9e-e85bd184c6d3)

‘Cheer up, Werner. It will soon be Christmas,’ I said.

I shook the bottle, dividing the last drips of whisky between the two white plastic cups that were balanced on the car radio. I pushed the empty bottle under the seat. The smell of the whisky was strong. I must have spilled some on the heater or on the warm leather that encased the radio. I thought Werner would decline it. He wasn’t a drinker and he’d had far too much already, but Berlin winter nights are cold and Werner swallowed his whisky in one gulp and coughed. Then he crushed the cup in his big muscular hands and sorted through the bent and broken pieces so that he could fit them all into the ashtray. Werner’s wife Zena was obsessionally tidy and this was her car.

‘People are still arriving,’ said Werner as a black Mercedes limousine drew up. Its headlights made dazzling reflections in the glass and paintwork of the parked cars and glinted on the frosty surface of the road. The chauffeur hurried to open the door and eight or nine people got out. The men wore dark cashmere coats over their evening suits, and the women a menagerie of furs. Here in Berlin Wannsee, where furs and cashmere are everyday clothes, they are called the Hautevolee and there are plenty of them.

‘What are you waiting for? Let’s barge right in and arrest him now.’ Werner’s words were just slightly slurred and he grinned to acknowledge his condition. Although I’d known Werner since we were kids at school, I’d seldom seen him drunk, or even tipsy as he was now. Tomorrow he’d have a hangover, tomorrow he’d blame me, and so would his wife, Zena. For that and other reasons, tomorrow, early, would be a good time to leave Berlin.

The house in Wannsee was big; an ugly clutter of enlargements and extensions, balconies, sun deck and penthouse almost hid the original building. It was built on a ridge that provided its rear terrace with a view across the forest to the black waters of the lake. Now the terrace was empty, the garden furniture stacked, and the awnings rolled up tight, but the house was blazing with lights and along the front garden the bare trees had been garlanded with hundreds of tiny white bulbs like electronic blossom.

‘The BfV man knows his job,’ I said. ‘He’ll come and tell us when the contact has been made.’

‘The contact won’t come here. Do you think Moscow doesn’t know we have a defector in London spilling his guts to us? They’ll have warned their network by now.’

‘Not necessarily,’ I said. I denied his contention for the hundredth time and didn’t doubt we’d soon be having the same exchange again. Werner was forty years old, just a few weeks older than I was, but he worried like an old woman and that put me on edge too. ‘Even his failure to come could provide a chance to identify him,’ I said. ‘We have two plainclothes cops checking everyone who arrives tonight, and the office has a copy of the invitation list.’

‘That’s if the contact is a guest,’ said Werner.

‘The staff are checked too.’

‘The contact will be an outsider,’ said Werner. ‘He wouldn’t be dumm enough to give us his contact on a plate.’

‘I know.’

‘Shall we go inside the house again?’ suggested Werner. ‘I get a cramp these days sitting in little cars.’

I opened the door and got out.

Werner closed his car door gently; it’s a habit that comes with years of surveillance work. This exclusive suburb was mostly villas amid woodland and water, and quiet enough for me to hear the sound of heavy trucks pulling into the Border Controlpoint at Drewitz to begin the long haul down the autobahn that went through the Democratic Republic to West Germany. ‘It will snow tonight,’ I predicted.

Werner gave no sign of having heard me. ‘Look at all that wealth,’ he said, waving an arm and almost losing his balance on the ice that had formed in the gutter. As far as we could see along it, the whole street was like a parking lot, or rather like a car showroom, for the cars were almost without exception glossy, new, and expensive. Five-litre V-8 Mercedes with car-phone antennas and turbo Porsches and big Ferraris and three or four Rolls-Royces. The registration plates showed how far people will travel to such a lavish party. Businessmen from Hamburg, bankers from Frankfurt, film people from Munich, and well-paid officials from Bonn. Some cars were perched high on the pavement to make room for others to be double-parked alongside them. We passed a couple of cops who were wandering between the long lines of cars, checking the registration plates and admiring the paintwork. In the driveway – stamping their feet against the cold – were two Parkwächter who would park the cars of guests unfortunate enough to be without a chauffeur. Werner went up the icy slope of the driveway with arms extended to help him balance. He wobbled like an overfed penguin.

Despite all the double-glazed windows, closed tight against the cold of a Berlin night, there came from the house the faint syrupy whirl of Johann Strauss played by a twenty-piece orchestra. It was like drowning in a thick strawberry milk shake.

A servant opened the door for us and another took our coats. One of our people was immediately inside, standing next to the butler. He gave no sign of recognition as we entered the flower-bedecked entrance hall. Werner smoothed his silk evening jacket self-consciously and tugged the ends of his bow tie as he caught a glimpse of himself in the gold-framed mirror that covered the wall. Werner’s suit was a hand-stitched custom-made silk one from Berlin’s most exclusive tailors, but on Werner’s thickset figure all suits looked rented.

Standing at the foot of the elaborate staircase there were two elderly men in stiff high collars and well-tailored evening suits that made no concessions to modern styling. They were smoking large cigars and talking with their heads close together because of the loudness of the orchestra in the ballroom beyond. One of the men stared at us but went on talking as if we weren’t visible to him. We didn’t seem right for such a gathering, but he looked away, no doubt thinking we were two heavies hired to protect the silver.

Until 1945 the house – or Villa, as such local mansions are known – had belonged to a man who began his career as a minor official with the Nazi farmers organization – and it was by chance that his department was given the task of deciding which farmers and agricultural workers were so indispensable to the economy that they would be exempt from service with the military forces. But from that time onwards – like other bureaucrats before and since – he was showered with gifts and opportunities and lived in high style, as his house bore witness.

For some years after the war the house was used as transit accommodation for US Army truck drivers. Only recently had it become a family house once more. The panelling, which so obviously dated back to the original nineteenth-century building, had been carefully repaired and reinstated, but now the oak was painted light grey. A huge painting of a soldier on a horse dominated the wall facing the stairs and on all sides there were carefully arranged displays of fresh flowers. But despite all the careful refurbishing, it was the floor of the entrance hall that attracted the eye. The floor was a complex pattern of black, white and red marble, a plain white central disc of newer marble having replaced a large gold swastika.

Werner pushed open a plain door secreted into the panelling and I followed him along a bleak corridor designed for the inconspicuous movement of servants. At the end of the passage there was a pantry. Clean linen cloths were arranged on a shelf, a dozen empty champagne bottles were inverted to drain in the sink and the waste bin was filled with the remains of sandwiches, discarded parsley, and some broken glass. A white-coated waiter arrived carrying a large silver tray of dirty glasses. He emptied them, put them into the service elevator together with the empty bottles, wiped the tray with a cloth from under the sink, and then departed without even glancing at either of us.

‘There he is, near the bar,’ said Werner, holding open the door so we could look across the crowded dance floor. There was a crush around the tables where two men in chef’s whites dispensed a dozen different sorts of sausages and foaming tankards of strong beer. Emerging from the scrum with food and drink was the man who was to be detained.

‘I hope like hell we’ve got this right,’ I said. The man was not just a run-of-the-mill bureaucrat; he was the private secretary to a senior member of the Bonn parliament.

I said, ‘If he digs his heels in and denies everything, I’m not sure we’ll be able to make it stick.’

I looked at the suspect carefully, trying to guess how he’d take it. He was a small man with crew-cut hair and a neat Vandyke beard. There was something uniquely German about that combination. Even amongst the over-dressed Berlin social set his appearance was flashy. His jacket had wide silk-faced lapels, and silk also edged his jacket, cuffs and trouser seams. The ends of his bow tie were tucked under his collar and he wore a black silk handkerchief in his top pocket.

‘He looks much younger than thirty-two, doesn’t he?’ said Werner.

‘You can’t rely on those computer printouts, especially with listed civil servants or even members of the Bundestag. They were all put onto the computer when it was installed, by copy typists working long hours of overtime to make a bit of spare cash.’

‘What do you think?’ said Werner.

‘I don’t like the look of him,’ I said.

‘He’s guilty,’ said Werner. He had no more information than I did, but he was trying to reassure me.

‘But the uncorroborated word of a defector such as Stinnes won’t cut much ice in an open court, even if London will let Stinnes go into a court. If this fellow’s boss stands by him and they both scream blue murder, he might get away with it.’

‘When do we take him, Bernie?’

‘Maybe his contact will come here,’ I said. It was an excuse for delay.

‘He’d have to be a real beginner, Bernie. Just one look at this place – lit up like a Christmas tree, cops outside, and no room to move – no one with any experience would risk coming into a place like this.’

‘Perhaps they won’t be expecting problems,’ I said optimistically.

‘Moscow know Stinnes is missing and they’ve had plenty of time to alert their networks. And anyone with experience will smell this stakeout when they park outside.’

‘He didn’t smell it,’ I said, nodding to our crew-cut man as he swigged at his beer and engaged a fellow guest in conversation.

‘Moscow can’t send a source like him away to their training school,’ said Werner. ‘But that’s why you can be quite certain that his contact will be Moscow-trained: and that means wary. You might as well arrest him now.’

‘We say nothing; we arrest no one,’ I told him once again. ‘German security are doing this one; he’s simply being detained for questioning. We stand by and see how it goes.’

‘Let me do it, Bernie.’ Werner Volkmann was a Berliner by birth. I’d come to school here as a young child, my German was just as authentic as his, but because I was English, Werner was determined to hang on to the conceit that his German was in some magic way more authentic than mine. I suppose I would feel the same way about any German who spoke perfect London-accented English, so I didn’t argue about it.

‘I don’t want him to know any non-German service is involved. If he tumbles to who we are, he’ll know Stinnes is in London.’

‘They know already, Bernie. They must know where he is by now.’

‘Stinnes has got enough troubles without a KGB hit squad searching for him.’

Werner was looking at the dancers and smiling to himself as if at some secret joke, the way people sometimes do when they’ve had too much to drink. His face was still tanned from his time in Mexico and his teeth were white and perfect. He looked almost handsome despite the lumpy fit of his suit. ‘It’s like a Hollywood movie,’ he said.

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘The budget’s too big for television.’ The ballroom was crowded with elegant couples, all wearing the sort of clothes that would have looked all right for a ball at the turn of the century. And the guests weren’t the desiccated old fogies I was expecting to see at this fiftieth birthday party for a manufacturer of dishwashers. There were plenty of richly clad young people whirling to the music of another time in another town. Kaiserstadt – isn’t that what Vienna was called at a time when there was only one Emperor in Europe and only one capital for him?

It was the makeup and the hairdos that sounded the jarring note of modernity, that and the gun I could see bulging under Werner’s beautiful silk jacket. I suppose that’s what was making it so tight across the chest.

The white-coated waiter returned with another big tray of glasses. Some of the glasses were not empty. There was the sudden smell of alcohol as he tipped cherries, olives, and abandoned drinks into the warm water of the sink before putting the glasses into the service lift. Then he turned to Werner and said respectfully, ‘They’ve arrested the contact, sir. Went to the car just as you said.’ He wiped the empty tray with a cloth.

‘What’s all this, Werner?’ I said.

The waiter looked at me and then at Werner and, when Werner nodded assent, said, ‘The contact went to the suspect’s parked car … a woman at least forty years old, maybe older. She had a key that fitted the car door. She unlocked the glove compartment and took an envelope. We’ve taken her into custody but the envelope has not yet been opened. The captain wants to know if he should take the woman back to the office or hold her here in the panel truck for you to talk to.’

The music stopped and the dancers applauded. Somewhere on the far side of the ballroom a man was heard singing an old country song. He stopped, embarrassed, and there was laughter.

‘Has she given a Berlin address?’

‘Kreuzberg. An apartment house near the Landwehr Canal.’

‘Tell your captain to take the woman to the apartment. Search it and hold her there. Phone here to confirm that she’s given the correct address and we’ll come along later to talk to her,’ I said. ‘Don’t let her make any phone calls. Make sure the envelope remains unopened; we know what’s in it. I’ll want it as evidence, so don’t let everybody maul it about.’

‘Yes, sir,’ said the waiter and departed, picking his way across the dance floor as the dancers walked off it.

‘Why didn’t you tell me he was one of our people?’ I asked Werner.

Werner giggled. ‘You should have seen your face.’

‘You’re drunk, Werner,’ I said.

‘You didn’t even recognize a plainclothes cop. What’s happening to you, Bernie?’

‘I should have guessed. They always have them clearing away the dirty dishes; a cop doesn’t know enough about food and wine to serve anything.’

‘You didn’t think it was worth watching his car, did you?’

He was beginning to irritate me. I said, ‘If I had your kind of money, I wouldn’t be dragging around with a lot of cops and security men.’

‘What would you be doing?’

‘With money? If I didn’t have the kids, I’d find some little pension in Tuscany, somewhere not too far from the beach.’

‘Admit it; you didn’t think it was worth watching his car, did you?’

‘You’re a genius.’

‘No need for sarcasm,’ said Werner. ‘You’ve got him now. Without me you would have ended up with egg on your face.’ He burped very softly, holding a hand over his mouth.

‘Yes, Werner,’ I said.

‘Let’s go and arrest the bastard … I had a feeling about that car – the way he locked the doors and then looked round like someone might be waiting there.’ There had always been a didactic side to Werner; he should have been a schoolteacher, as his mother wanted.

‘You’re a drunken fool, Werner,’ I said.

‘Shall I go and arrest him?’

‘Go and breathe all over him,’ I said.

Werner smiled. Werner had proved what a brilliant field agent he could be. Werner was very very happy.

He made a fuss of course. He wanted his lawyer and wanted to talk to his boss and to some friend of his in the government. I knew the type only too well; he was treating us as if we’d been caught stealing secrets for the Russians. He was still protesting when he departed with the arrest team. They were not impressed; they’d seen it all before. They were experienced men, brought in from the BfV’s ‘political office’ in Bonn.

They took him to the BfV office in Spandau, but I decided they’d get nothing but indignation out of him that night. Tomorrow perhaps he’d simmer down a little and get nervous enough to say something worth hearing before the time came when they’d have to charge him or release him. Luckily it was a decision I wouldn’t have to make. Meanwhile, I decided to go and see if there was anything to be got out of the woman.

Werner drove. He didn’t speak much on the journey back to Kreuzberg. I stared out of the window. Berlin is a sort of history book of twentieth-century violence, and every street corner brought a recollection of something I’d heard, seen, or read. We followed the road alongside the Landwehr Canal, which twists and turns through the heart of the city. Its oily water holds many dark secrets. Back in 1919, when the Spartakists attempted to seize the city by an armed uprising, two officers of the Horse Guards took the badly beaten Rosa Luxemburg – a Communist leader – from their headquarters at the Eden Hotel, next to the Zoo, shot her dead and threw her into the canal. The officers pretended that she’d been carried off by angry rioters, but four months later her bloated corpse floated up and got jammed into a lock gate. Now, in East Berlin, they name streets after her.

But not all the ghosts go into this canal. In February 1920 a police sergeant pulled a young woman out of the canal at the Bendler Bridge. Taken to the Elisabeth Hospital in Lützowstrasse, she was later identified as the Grand Duchess Anastasia, the youngest daughter of the last Czar of All the Russias and only survivor of the massacre.

‘This is it,’ said Werner, pulling in to the kerb. ‘Good job there’s a cop on the door, or we’d come back to find the car stripped to the chassis.’

The address the contact had given was a shabby nineteenth-century tenement in a neighbourhood virtually taken over by Turkish immigrants. The once imposing grey stone entrance, still pitted with splinter damage from the war, was defaced by brightly coloured graffiti sprays. Inside the gloomy hallway there was a smell of spicy food and dirt and disinfectant.

These old houses have no numbered apartments, but we found the BfV men at the very top. There were two security locks on the door, but not much sign of anything inside to protect. Two men were still searching the hallway when we arrived. They were tapping the walls, prizing up floorboards, and poking screwdrivers deep into the plaster with that sort of inscrutable delight that comes to men blessed by governmental authority to be destructive.

It was typical of the overnight places the KGB provided for the faithful. Top floors: cold, cramped and cheap. Perhaps they chose these sleazy accommodations to remind all concerned about the plight of the poor in the capitalist economy. Or perhaps in this sort of district there were fewer questions asked about comings and goings by all kinds of people at all kinds of hours.

No TV, no radio, no soft seats. Iron bedstead with an old grey blanket, four wooden chairs, a small plastic-topped table and upon it black bread roughly sliced, electric ring, dented kettle, tinned milk, dried coffee, and some sugar cubes wrapped to show they were from a Hilton hotel. There were three dog-eared German paperback books – Dickens, Schiller, and a collection of crossword puzzles, mostly completed. On one of the two single beds a small case was opened and its contents displayed. It was obviously the woman’s baggage: a cheap black dress, nylon underwear, low-heeled leather shoes, an apple and orange, and an English newspaper – the Socialist Worker.

A young BfV officer was waiting for me there. We exchanged greetings and he told me the woman had been given no more than a brief preliminary questioning. She’d offered to make a statement at first and then said she wouldn’t, the officer said. He’d sent a man to get a typewriter so it could be taken down if she changed her mind again. He handed me some Westmarks, a driving licence, and a passport; the contents of her handbag. The licence and passport were British.

‘I’ve got a pocket recorder,’ I told him without lowering my voice. ‘We’ll sort out what to type and have it signed after I’ve spoken with her. I’ll want you to witness her signature.’

The woman was seated in the tiny kitchen. There were dirty cups on the table and some hairpins that I guessed had come from a search of the handbag she now held on her lap.

‘The captain tells me that you want to make a statement,’ I said in English.

‘Are you English?’ she said. She looked at me and then at Werner. She showed no great surprise that we were both in dinner suits complete with fancy cuff links and patent-leather shoes. She must have realized we’d been on duty inside the house.

‘Yes,’ I said. I signalled with my hand to tell Werner to leave the room.

‘Are you in charge?’ she asked. She had the exaggerated upper-class accent that shop girls use in Knightsbridge boutiques. ‘I want to know what I’m charged with. I warn you I know my rights. Am I under arrest?’

From the side table I picked up the bread knife and waved it at her. ‘Under Law 43 of the Allied Military Government legislation, still in force in this city, possession of this bread knife is an offence for which the death sentence can be imposed.’

‘You must be mad,’ she said. ‘The war was almost forty years ago.’

I put the knife into a drawer and slammed it shut. She was startled by the sound. I moved a kitchen chair and sat on it so that I was facing her at a distance of only a yard or so. ‘You’re not in Germany,’ I told her. ‘This is Berlin. And Decree 511, ratified in 1951, includes a clause that makes information gathering an offence for which you can get ten years in prison. Not spying, not intelligence work, just collecting information is an offence.’

I put her passport on the table and turned the pages as if reading her name and occupation for the first time. ‘So don’t talk to me about knowing your rights; you’ve got no rights.’

From the passport I read aloud: ‘Carol Elvira Miller, born in London 1930, occupation: schoolteacher.’ Then I looked up at her. She returned my gaze with the calm, flat stare that the camera had recorded for her passport. Her hair was straight and short in pageboy style. She had clear blue eyes and a pointed nose, and the pert expression came naturally to her. She’d been pretty once, but now she was thin and drawn and – in dark conservative clothes and with no trace of makeup – well on the way to looking like a frail old woman. ‘Elvira. That’s a German name, isn’t it?’

She showed no sign of fear. She brightened as women so often do at personal talk. ‘It’s Spanish. Mozart used it in Don Giovanni.’

I nodded. ‘And Miller?’

She smiled nervously. She was not frightened, but it was the smile of someone who wanted to seem cooperative. My hectoring little speech had done the trick. ‘My father is German … was German. From Leipzig. He emigrated to England long before Hitler’s time. My mother is English … from Newcastle,’ she added after a long pause.

‘Married?’

‘My husband died nearly ten years ago. His name was Johnson, but I went back to using my family name.’

‘Children?’

‘A married daughter.’

‘Where do you teach?’

‘I was a supply teacher in London, but the amount of work I got grew less and less. For the last few months I’ve been virtually unemployed.’

‘You know what was in the envelope you collected from the car tonight?’

‘I won’t waste your time with excuses. I know it contained secrets of some description.’ She had the clear voice and pedantic manner of schoolteachers everywhere.

‘And you know where it was going?’

‘I want to make a statement. I told the other officer that. I want to be taken back to England and speak to someone in British security. Then I’ll make a complete statement.’

‘Why?’ I said. ‘Why are you so anxious to go back to England? You’re a Russian agent; we both know that. What’s the difference where you are when you’re charged?’

‘I’ve been stupid,’ she said. ‘I realize that now.’

‘Did you realize it before or after you were taken into custody?’

She pressed her lips together as if suppressing a smile. ‘It was a shock.’ She put her hands on the table. They were white and wrinkled with the brown freckle marks that come with middle age. There were nicotine stains, and the ink from a leaky pen had marked finger and thumb. ‘I just can’t stop trembling. Sitting here watching the security men searching through my luggage, I’ve had enough time to consider what a fool I’ve been. I love England. My father brought me up to love everything English.’

Despite this contention she soon slipped back into speaking German. She wasn’t German; she wasn’t British. I saw the rootless feeling within her and recognized something of myself.

I said, ‘A man was it?’ She looked at me and frowned. She’d been expecting reassurance, a smile in return for the smiles she’d given me and a promise that nothing too bad would happen to her. ‘A man … the one who enticed you into this foolishness?’

She must have heard some note of scorn in my voice. ‘No,’ she said. ‘It was all my own doing. I joined the Party fifteen years ago. After my husband died I wanted to keep myself occupied. So I became a very active worker for the teachers union. And one day I thought, well, why not go the whole hog.’

‘What was the whole hog, Mrs Miller?’

‘My father’s name was Müller; I may as well tell you that because you will soon find out. Hugo Müller. He changed it to Miller when he was naturalized. He wanted us all to be English.’ Again she pressed her hands flat on the table and looked at them while she spoke. It was as if she was blaming her hands for doing things of which she’d never really approved.

‘I was asked to collect parcels, look after things, and so on. Later I began providing accommodation in my London flat. People were brought there late at night – Russians, Czechs, and so on – usually they spoke no English and no German either. Seamen sometimes, judging by their clothing. They always seemed to be ravenously hungry. Once there was a man dressed as a priest. He spoke Polish, but I managed to make myself understood. In the morning someone would come and collect them.’

She sighed and then looked up at me to see how I was taking her confession. ‘I have a spare bedroom,’ she added, as if the propriety of their sleeping arrangements was more important than her services to the KGB.

She stopped talking for a long time and looked at her hands.

‘They were fugitives,’ I said, to prompt her into talking again.

‘I don’t know who they were. Afterwards there was usually an envelope with a few pounds put through my letterbox, but I didn’t do it for the money.’

‘Why did you do it?’

‘I was a Marxist; I was serving the cause.’

‘And now?’

‘They made a fool of me,’ she said. ‘They used me to do their dirty work. What did they care what happened to me if I got caught? What do they care now? What am I supposed to do?’

It sounded more like the bitter complaint of a woman abandoned by her lover than of an agent under arrest. ‘You’re supposed to enjoy being a martyr,’ I said. ‘That’s the way the system works for them.’

‘I’ll give you the names and addresses. I’ll tell you everything I know.’ She leaned forward. ‘I don’t want to go to prison. Will it all have to be in the newspapers?’

‘Does it matter?’

‘My married daughter is living in Canada. She’s married to a Spanish boy she met on holiday. They’ve applied for Canadian citizenship but their papers haven’t come through yet. It would be terrible if this trouble I’m in ruined their lives; they’re so happy together.’

‘And this overnight accommodation you were providing for your Russian friends – when did that all stop?’

She looked up sharply, as if surprised that I could guess that it had stopped.

‘The two jobs don’t mix,’ I said. ‘The accommodation was just an interim task to see how reliable you were.’

She nodded. ‘Two years ago,’ she said softly, ‘perhaps two and a half years.’

‘Then?’

‘I came to Berlin for a week. They paid my fare. I went through to the East and spent a week in a training school. All the other students were German, but as you see I speak German well. My father always insisted that I kept up my German.’

‘A week at Potsdam?’

‘Yes, just outside Potsdam, that’s right.’

‘Don’t miss out anything important, Mrs Miller,’ I said.

‘No, I won’t,’ she promised nervously. ‘I was there for ten days learning about shortwave radios and microdots and so on. You probably know the sort of thing.’

‘Yes, I know the sort of thing. It’s a training school for spies.’

‘Yes,’ she whispered.

‘You’re not going to tell me you came back from there without realizing you were a fully trained Russian spy, Mrs Miller?’

She looked up and met my stare. ‘No, I’ve told you, I was an enthusiastic Marxist. I was perfectly ready to be a spy for them. As I saw it, I was doing it on behalf of the oppressed and hungry people of the world. I suppose I still am a Marxist-Leninist.’

‘Then you must be an incurable romantic,’ I said.

‘It was wrong of me to do what I did; I can see that, of course. England has been good to me. But half the world is starving and Marxism is the only solution.’

‘Don’t lecture me, Mrs Miller,’ I said. ‘I get enough of that from my office.’ I got up so that I could unbutton my overcoat and find my cigarettes. ‘Do you want a cigarette?’ I said.

She gave no sign of having heard me.

‘I’m trying to give them up,’ I said, ‘but I carry the cigarettes with me.’

She still didn’t answer. Perhaps she was too busy thinking about what might happen to her. I went to the window and looked out. It was too dark to see very much except Berlin’s permanent false dawn: the greenish white glare that came from the floodlit ‘death strip’ along the east side of the Wall. I knew this street well enough; I’d passed this block thousands of times. Since 1961, when the Wall was first built, following the snaky route of the Landwehr Canal had become the quickest way to get around the Wall from the neon glitter of the Ku-damm to the floodlights of Checkpoint Charlie.

‘Will I go to prison?’ she said.

I didn’t turn round. I buttoned my coat, pleased that I’d resisted the temptation to smoke. From my pocket I brought the tiny Pearlcorder tape machine. It was made of a bright silver metal. I made no attempt to hide it. I wanted her to see it.

‘Will I go to prison?’ she asked again.

‘I don’t know,’ I said. ‘But I hope so.’

It had taken no more than forty minutes to get her confession. Werner was waiting for me in the next room. There was no heating in that room. He was sitting on a kitchen chair, the fur collar of his coat pulled up round his ears so that it almost touched the rim of his hat.

‘A good squeal?’ he asked.

‘You look like an undertaker, Werner,’ I said. ‘A very prosperous undertaker waiting for a very prosperous corpse.’

‘I’ve got to sleep,’ he said. ‘I can’t take these late nights any more. If you’re going to hang on here, to type it all out, I’d rather go home now.’

It was the drink that had got to him, of course. The ebullience of intoxication didn’t last very long with Werner. Alcohol is a depressant and Werner’s metabolic rate had slowed enough to render him unfit to drive. ‘I’ll drive,’ I said. ‘And I’ll make the transcription on your typewriter.’

‘Sure,’ said Werner. I was staying with him in his apartment at Dahlem. And now, in his melancholy mood, he was anticipating his wife’s reaction to us waking her up by arriving in the small hours of the morning. Werner’s typewriter was a very noisy machine and he knew I’d want to finish the job before going to sleep. ‘Is there much of it?’ he asked.

‘It’s short and sweet, Werner. But she’s given us a few things that might make London Central scratch their heads and wonder.’

‘Such as?’

‘Read it in the morning, Werner. We’ll talk about it over breakfast.’

It was a beautiful Berlin morning. The sky was blue despite all those East German generating plants that burn brown coal so that pale smog sits over the city for so much of the year. Today the fumes of the Braunkohle were drifting elsewhere, and outside the birds were singing to celebrate it. Inside, a big wasp, a last survivor from the summer, buzzed around angrily.

Werner’s Dahlem apartment was like a second home to me. I’d known it when it was a gathering place for an endless stream of Werner’s oddball friends. In those days the furniture was old and Werner played jazz on a piano decorated with cigarette burns, and Werner’s beautifully constructed model planes were hanging from the ceiling because that was the only place where they would not be sat upon.

Now it was all different. The old things had all been removed by Zena, his very young wife. Now the flat was done to her taste: expensive modern furniture and a big rubber plant, and a rug that hung on the wall and bore the name of the ‘artist’ who’d woven it. The only thing that remained from the old days was the lumpy sofa that converted to the lumpy bed on which I’d slept.

The three of us were sitting in the ‘breakfast room’, a counter at the end of the kitchen. It was arranged like a lunch counter with Zena playing the role of bartender. From here there was a view through the window, and we were high enough to see the sun-edged treetops of the Grunewald just a block or two away. Zena was squeezing oranges in an electric juicer, and in the automatic coffee-maker the coffee was dripping, its rich aroma floating through the room.

We were talking about marriage. I said, ‘The tragedy of marriage is that while all women marry thinking that their man will change, all men marry believing their wife will never change. Both are invariably disappointed.’

‘What rot,’ said Zena as she poured the juice into three glasses. ‘Men do change.’

She bent down to see better the level of the juice and ensure that we all got precisely the same amount. It was a legacy of the Prussian family background of which she was so proud, despite the fact that she’d never even seen the old family homeland. For Prussians like to think of themselves not only as the conscience of the world, but also its final judge and jury.

‘Don’t encourage him, Zena darling,’ said Werner. ‘That contrived Oscar Wilde-ish assertion is just Bernard’s way of annoying wives.’

Zena didn’t let it go; she liked to argue with me. ‘Men change. It’s men who usually leave home and break up the marriage. And it’s because they change.’

‘Good juice,’ I said, sipping some.

‘Men go out to work. Men want promotion in their jobs and they aspire to the higher social class of their superiors. Then they feel their wives are inadequate and start looking for a wife who knows the manners and vocabulary of that class they want to join.’

‘You’re right,’ I admitted. ‘I meant that men don’t change in the way that their women want them to change.’

She smiled. She knew that I was commenting on the way she had changed poor Werner from being an easygoing and somewhat bohemian character into a devoted and obedient husband. It was Zena who had stopped him smoking and made him diet enough to reduce his waistline. And it was Zena who approved everything he bought to wear, from swimming trunks to tuxedo. In this respect Zena regarded me as her opponent. I was the bad influence who could undo all her good work, and that was something Zena was determined to prevent.

She climbed up onto the stool. She was so well proportioned that you only noticed how tiny she was when she did such things. She had long, dark hair and this morning she’d clipped it back into a ponytail that reached down to her shoulder blades. She was wearing a red cotton kimono with a wide black sash around her middle. She’d not missed any sleep that night and her eyes were bright and clear; she’d even found time enough to put on a touch of makeup. She didn’t need makeup – she was only twenty-two years old and there was no disputing her beauty – but the makeup was something from behind which she preferred to face the world.

The coffee was very dark and strong. She liked it like that, but I poured a lot of milk into mine. The buzzer on the oven sounded and Zena went to get the warm rolls. She put them into a small basket with a red-checked cloth before offering them to us. ‘Brötchen,’ she said. Zena was born and brought up in Berlin, but she didn’t call the bread rolls Schrippe the way the rest of the population of Berlin did. Zena didn’t want to be identified with Berlin; she preferred keeping her options open.

‘Any butter?’ I said, breaking open the bread roll.

‘We don’t eat it,’ said Zena. ‘It’s bad for you.’

‘Give Bernie some of that new margarine,’ said Werner.

‘You should lose some weight,’ Zena told me. ‘I wouldn’t even be eating bread if I were you.’

‘There are all kinds of other things I do that you wouldn’t do if you were me,’ I said. The wasp settled in my hair and I brushed it away.

She decided not to get into that one. She rolled up a newspaper and aimed some blows at the wasp. Then with unconcealed ill-humour she went to the refrigerator and brought me a plastic tub of margarine. ‘Thanks,’ I said. ‘I’m catching the morning flight. I’ll get out of your way as soon as I’m shaved.’

‘No hurry,’ said Werner to smooth things over. He had already shaved, of course; Zena wouldn’t have let him have breakfast if he’d turned up unshaven. ‘So you got all your typing done last night,’ he said. ‘I should have stayed up and helped.’

‘It wasn’t necessary. I’ll have the translation done in London. I appreciate you and Zena giving me a place to sleep, to say nothing of the coffee last night and Zena’s great breakfast this morning.’

I overdid the appreciation I suppose. I’m prone to do this when I’m nervous, and Zena was a great expert at making me nervous.

‘I was damned tired,’ said Werner.

Zena shot me a glance, but when she spoke it was to Werner. ‘You were drunk,’ she said. ‘I thought you were supposed to be working last night.’

‘We were, darling,’ said Werner.

‘There wasn’t much drinking, Zena,’ I said.

‘Werner gets drunk on the smell of a barmaid’s apron,’ said Zena.

Werner opened his mouth to object to this put-down. Then he realized that he could only challenge it by claiming to have drunk a great deal. He sipped some coffee instead.

‘I’ve seen her before,’ said Werner.

‘The woman?’

‘What’s her name?’

‘She says it’s Müller, but she was married to a man named Johnson at one time. Here? You’ve seen her here? She said she lives in England.’

‘She went to the school in Potsdam,’ said Werner. He smiled at my look of surprise. ‘I read your report when I got up this morning. You don’t mind, do you?’

‘Of course not. I wanted you to read it. There might be developments.’

‘Was this to do with Erich Stinnes?’ said Zena. She waved the wasp away from her head.

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘It was his information.’

She nodded and poured herself more coffee. It was difficult to believe that not so long ago she’d been in love with Erich Stinnes. It was difficult to believe that she’d risked her life to protect him and that she was still having physiotherapy sessions because of injuries she’d suffered in his defence.

But Zena was young; and romantic. For both of those reasons, her passions could be of short duration. And for both those reasons, it could well be that she had never been in love with him, but merely in love with the idea of herself in love.

Werner seemed not to notice the mention of Erich Stinnes’s name. That was Werner’s way – honi soit qui mal y pense. Evil to him who evil thinks – that could well be Werner’s motto, for Werner was too generous and considerate to ever think the worst of anyone. And even when the worst was evident, Werner was ready to forgive. Zena’s flagrant love affair with Frank Harrington – the head of our Berlin Field Unit, the Berlin Resident – had made me angrier with her than Werner had been.

Some people said that Werner was the sort of masochist who got a perverse pleasure from the knowledge that his wife had gone off to live with Frank, but I knew Werner too well to go in for that sort of instant psychology. Werner was a tough guy who played the game by his own rules. Maybe some of his rules were flexible, but God help anyone who overstepped the line that Werner drew. Werner was an Old Testament man, and his wrath and vengeance could be terrible. I know, and Werner knows I know. That’s what makes us so close that nothing can come between us, not even the cunning little Zena.

‘I’ve seen that Miller woman somewhere,’ said Werner. ‘I never forget a face.’ He watched the wasp. It was sleepy, crawling slowly up the wall. Werner reached for Zena’s newspaper, but the wasp, sensing danger, flew away.

Zena was still thinking of Erich Stinnes. ‘We do all the work,’ she said bitterly. ‘Bernard gets all the credit. And Erich Stinnes gets all the money.’ She was referring to the way in which Stinnes, a KGB major, had been persuaded to come over to work for us and given a big cash payment. She reached for the jug, and some coffee dripped onto the hotplate making a loud, hissing sound. When she’d poured coffee for herself, she put the very hot jug onto the tiles of the counter. The change of temperature must have made the jug crack, for there was a sound like a pistol shot and the hot coffee flowed across the counter top so that we all jumped to our feet to avoid being scalded.

Zena grabbed some paper towels and, standing well back from the coffee flowing onto the tiled floor, dabbed them around. ‘I put it down too hard,’ she said when the mess was cleared away.

‘I think you did, Zena,’ I said.

‘It was already cracked,’ said Werner. Then he brought the rolled newspaper down on the wasp and killed it.

2 (#u86bf1dc7-af96-5a24-ac9e-e85bd184c6d3)

It was eight o’clock that evening in London when I finally delivered my report to my immediate boss, Dicky Cruyer, Controller German Stations. I’d attached a complete translation too, as I knew Dicky wasn’t exactly bilingual.

‘Congratulations,’ he said. ‘One up to Comrade Stinnes eh?’ He shook the flimsy pages of my hastily written report as if something might fall from between them. He’d already heard my tape and had my oral account of the Berlin trip so there was little chance that he’d read the report very thoroughly, especially if it meant missing his dinner.

‘No one in Bonn will thank us,’ I warned him.

‘They have all the evidence they need,’ said Dicky with a sniff.

‘I was on the phone to Berlin an hour ago,’ I said. ‘He’s pulling all the strings that can be pulled.’

‘What does his boss say?’

‘He’s spending his Christmas vacation in Egypt. No one can find him,’ I said.

‘What a sensible man,’ said Dicky with admiration that was both sincere and undisguised. ‘Was he informed of the impending arrest of his secretary?’

‘Not by us, but that would be the regular BfV procedure.’

‘Have you phoned Bonn this evening? What do BfV reckon the chances of a statement from him?’

‘Better we stay out of it, Dicky.’

Dicky looked at me while he thought about this and then, deciding I was right, tried another aspect of the same problem. ‘Have you seen Stinnes since you handed him over to London Debriefing Centre?’

‘I gather the current policy is to keep me away from him.’

‘Come along,’ said Dicky, smiling to humour me in my state of paranoia. ‘You’re not saying you’re still suspect?’ He stood up from behind the rosewood table that he used instead of a desk and got a transparent plastic folding chair for me.

‘My wife defected.’ I sat down. Dicky had removed his visitors’ chairs on the pretext of making more space. His actual motive was to provide an excuse for him to use the conference rooms along the corridor. Dicky liked to use the conference rooms; it made him feel important and it meant that his name was exhibited in little plastic letters on the notice board opposite the top-floor lifts.

His folding chairs were the most uncomfortable seats in the building, but Dicky didn’t worry about this as he never sat in them. And anyway, I didn’t want to sit chatting with him. There was still work to clear up before I could go home.

‘That’s all past history,’ said Dick, running a thin bony hand through his curly hair so that he could take a surreptitious look at his big black wristwatch, the kind that works deep under water.

I’d always suspected that Dicky would be more comfortable with his hair cut short and brushed, and in the dark suits, white shirts and old school ties that were de rigueur for senior staff. But he persisted in being the only one of us who wore faded denim, cowboy boots, coloured neckerchiefs, and black leather because he thought it would help to identify him as an infant prodigy. But perhaps I had it the wrong way round; perhaps Dicky would have been happier to keep the trendy garb and be ‘creative’ in an advertising agency.

He zipped the front of his jacket up and down again and said, ‘You’re the local hero. You are the one who brought Stinnes to us at a time when everyone here said it couldn’t be done.’

‘Is that what they were saying? I wish I’d known. The way I heard it, a lot of people were saying I did everything to avoid bringing him in because I was frightened his debriefing would drop me into it.’

‘Well, anyone who was spreading that sort of story is now looking pretty damned stupid.’

‘I’m not in the clear yet, Dicky. You know it and I know it, so let’s stop all this bullshit.’

He held up his hand as if to ward off a blow. ‘You’re still not clear on paper,’ said Dicky. ‘On paper … and you know why?’

‘No, I don’t know why. Tell me.’

Dicky sighed. ‘For the simple but obvious reason that this Department needs an excuse to hold Stinnes in London Debriefing Centre and keep on pumping him. Without an ongoing investigation of our own staff, we’d have to hand Stinnes over to MI5 … That’s why the Department haven’t cleared you yet: it’s a department necessity, Bernard, nothing sinister about it.’

‘Who’s in charge of the Stinnes debriefing?’ I asked.

‘Don’t look at me, old friend. Stinnes is a hot potato. I don’t want any part of that one. Neither does Bret … no one up here on the top floor wants anything to do with it.’

‘Things could change,’ I said. ‘If Stinnes gives us a couple more winners like this one, then a few people will start to see that being in charge of the Stinnes debriefing could be the road to fame and fortune.’

‘I don’t think so,’ said Dicky. ‘The tip-off you handled in Berlin was just for openers … a few quick forays before Moscow tumble what’s happening to their networks. Once the dust settles, the interrogators will take Stinnes through the files … right?’

‘Files? You mean they’ll be poking into all our past operations?’

‘Not all of them. I don’t suppose they’ll go back to discover how Christopher Marlowe discovered that the Spanish Armada had sailed.’ Dicky permitted himself a smile at this joke. ‘It’s obvious that the Department will want to discover how good our guesses were. They’ll play all the games again, but this time they’ll know which ones have a happy ending.’

‘And you’ll go along with that?’

‘They won’t consult me, old son. I’m just German Stations Controller; I’m not the D-G. I’m not even on the Policy Committee.’

‘Giving Stinnes access to department archives would be showing a lot of trust in him.’

‘You know what the old man’s like. Deputy D-G came in yesterday on one of his rare visits to the building. He’s enraptured about the progress of the Stinnes debriefing.’

‘If Stinnes is a plant …’

‘Ah, if Stinnes is a plant …’ Dicky sank down in his Charles Eames chair and put his feet on the matching footstool. The night was dark outside and the windowpanes were like ebony reflecting a perfect image of the room. Only the antique desk light was on; it made a pool of light on the table where the report and transcript were placed side by side. Dicky almost disappeared into the gloom except when the light reflected from the brass buckle of his belt or shone on the gold medallion he wore suspended inside his open-neck shirt. ‘But the idea that Stinnes is a plant is hard to sustain when he’s just given us three well-placed KGB agents in a row.’

He looked at his watch before shouting ‘Coffee’ loudly enough for his secretary to hear in the adjoining room. When Dicky worked late, his secretary worked late too. He didn’t trust the duty roster staff with making his coffee.

‘Will he talk, this one you arrested in Berlin? He had a year with the Bonn Defence Ministry, I notice from the file.’

‘I didn’t arrest him; we left it to the Germans. Yes, he’ll talk if they push him hard enough. They have the evidence and – thanks to Volkmann – they’re holding the woman who came to collect it from the car.’

‘And I’m sure you put all that in your report. Are you now the official secretary of the Werner Volkmann fan club? Or is this something you do for all your old school chums?’

‘He’s very good at what he does.’

‘And so we all agree, but don’t tell me that but for Volkmann, we wouldn’t have picked up the woman. Staking out the car is standard procedure. Ye gods, Bernard, any probationary cop would do that as a matter of course.’

‘A commendation would work wonders for him.’

‘Well, he’s not getting any bloody commendation from me. Just because he’s your close friend, you think you can inveigle any kind of praise and privilege out of me for him.’

‘It wouldn’t cost anything, Dicky,’ I said mildly.

‘No, it wouldn’t cost anything,’ said Dicky sarcastically. ‘Not until the next time he makes some monumental cock-up. Then someone asks me how come I commended him; then it would cost something. It would cost me a chewing out and maybe a promotion.’

‘Yes, Dicky,’ I said.

Promotion? Dicky was two years younger than me and he’d already been promoted several rungs beyond his competence. What promotion did he have his eye on now? He’d only just fought off Bret Rensselaer’s attempt to take over the German desk. I’d thought he’d be satisfied to consolidate his good fortune.

‘And what do you make of this Englishwoman?’ He tapped the roughly typed transcript of her statement. ‘Looks as if you got her talking.’

‘I couldn’t stop her,’ I said.

‘Like that, was it? I don’t want to go all through it again tonight. Anything important?’

‘Some inconsistencies that should be followed up.’

‘For instance?’

‘She was working in London, handling selected items for immediate shortwave radio transmission to Moscow.’

‘Must have been bloody urgent,’ said Dicky. So he’d noticed that already. Had he waited to see if I brought it up? ‘And that means damned good. Right? I mean, not even handled through the Embassy radio, so it was a source they wanted to keep very very secret.’

‘Fiona’s material probably,’ I said.

‘I wondered if you’d twig that,’ said Dicky. ‘It was obviously the stuff your wife was betraying out of our day-to-day operational files.’

He liked to twist the knife in the wound. He held me personally responsible for what Fiona had done; he’d virtually said so on more than one occasion.

‘But the material kept coming.’

Dicky frowned. ‘What are you getting at?’

‘It kept coming. First-grade material even after Fiona ran for it.’

‘This woman’s transmitted material wasn’t all from the same source,’ said Dicky. ‘I remember what she said when you played your tape to me.’

He picked up the transcript and tried to find what he wanted in the muddle of humms and hahhs and ‘indistinct passage’ marks that are always a part of transcripts from such tape recordings. He put the sheets down again.

‘Well anyway, I remember there were two assignment codes: Jake and Ironfoot. Is that what’s worrying you?’

‘We should follow it up!’ I said. ‘I don’t like loose ends like that. The dates suggest that Fiona was Ironfoot. Who the hell was Jake?’

‘The Fiona material is our worry. Whatever else Moscow got – and are still getting – is a matter for Five. You know that, Bernard. It’s not our job to search high and low to find Russian spies.’

‘I still think we should check this woman’s statement against what Stinnes knows.’

‘Stinnes is nothing to do with me, Bernard. I’ve just told you that.’

‘Well, I think he should be. It’s madness that we don’t have access to him without going to Debriefing Centre for permission.’

‘Let me tell you something, Bernard,’ said Dicky, leaning well back in the soft leather seat and adopting the manner of an Oxford don explaining the law of gravity to a delivery boy. ‘When London Debriefing Centre get through with Stinnes, heads will roll up here on the top floor. You know the monumental cock-ups that have dogged the work of this Department for the last few years. Now we’ll have chapter and verse on every decision made up here while Stinnes was running things in Berlin. Every decision made by senior staff will be scrutinized with twenty-twenty hindsight. It could get messy; people with a history of bad decisions are going to be axed very smartly.’

Dicky smiled. He could afford to smile; Dicky had never made a decision in his life. Whenever something decisive was about to happen, Dicky went home with a headache.

‘And you think that whoever’s in charge of the Stinnes debriefing will be unpopular?’

‘Running a witch-hunt is not likely to be a social asset,’ said Dicky.

I thought ‘witch-hunt’ was an inaccurate description of the weeding out of incompetents, but there would be plenty who would favour Dicky’s terminology.

‘And that’s not only my opinion,’ he added. ‘No one wants to take Stinnes. And I don’t want you saying we should have responsibility for him.’

Dicky’s secretary brought coffee.

‘I was just coming, Mr Cruyer,’ she said apologetically. She was a mousy little widow whose every sheet of typing was a patchwork of white correcting paint. At one time Dicky had had a shapely twenty-five-year-old divorcee as secretary, but his wife, Daphne, had made him get rid of her. At the time, Dicky had pretended that firing the secretary was his idea; he said it was because she didn’t boil the water properly for his coffee. ‘Your wife phoned. She wanted to know what time to expect you for dinner.’

‘And what did you say?’ Dicky asked her.

The poor woman hesitated, worrying if she’d done the right thing. ‘I said you were at a meeting and I would call her back.’

‘Tell my wife not to wait dinner for me. I’ll get a bite to eat somewhere or other.’

‘If you want to get away, Dicky,’ I said, rising to my feet.

‘Sit down, Bernard. We can’t waste a decent cup of coffee. I’ll be home soon enough. Daphne knows what this job is like; eighteen hours a day lately.’ It was not a soft, melancholy reflection but a loud proclamation to the world, or at least to me and his secretary who departed to pass the news on to Daphne.

I nodded but I couldn’t help wondering if Dicky was scheduling a visit to some other lady. Lately I’d noticed a gleam in his eye and a spring in his step and a most unusual willingness to stay late at the office.

Dicky got up from his easy chair and fussed over the antique butler’s tray which his secretary had placed so carefully on his side table. He emptied the Spode cups of the hot water and half filled each warmed cup with black coffee. Dicky was extremely particular about his coffee. Twice a week he sent one of the drivers to collect a packet of freshly roasted beans from Mr Higgins in South Molton Street – chagga, no blends – and it had to be ground just before brewing.

‘That’s good,’ he said, sipping it with all the studied attention of the connoisseur he claimed to be. Having approved the coffee, he poured some for me.

‘Wouldn’t it be better to stay away from Stinnes, Bernard? He doesn’t belong to us any longer, does he?’ He smiled. It was a direct order; I knew Dicky’s style.

‘Can I have milk or cream or something in mine?’ I said. ‘That strong black brew you make keeps me awake at night.’

He always had a jug of cream and a bowl of sugar brought in with his coffee although he never used either. He once told me that in his regimental officers’ mess, the cream was always on the table but it was considered bad form to take any. I wondered if there were a lot of people like Dicky in the Army; it was a dreadful thought. He brought the cream to me.

‘You’re getting old, Bernard. Did you ever think of jogging? I run three miles every morning – summer, winter, Christmas, every morning without fail.’

‘Is it doing you any good?’ I asked as he poured cream for me from the cow-shaped silver jug.

‘Ye gods, Bernard. I’m fitter now than I was at twenty-five. I swear I am.’

‘What kind of shape were you in at twenty-five?’ I said.

‘Damned good.’ He put the jug down so that he could run his fingers round the brass-buckled leather belt that held up his jeans. He sucked in his stomach to exaggerate his slim figure and then slammed himself in the gut with a flattened hand. Even without the intake of breath, his lack of fat was impressive. Especially when you took into account the countless long lunches he charged against his expense account.

‘But not as good as now?’ I persisted.

‘I wasn’t fat and flabby the way you are, Bernard. I didn’t huff and puff every time I went up a flight of stairs.’

‘I thought Bret Rensselaer would take over the Stinnes debriefing.’

‘Debriefing,’ said Dicky suddenly. ‘How I hate that word. You get briefed and maybe briefed again, but there is no way anyone can be debriefed.’

‘I thought Bret would jump at it. He’s been out of a job since Stinnes was enrolled.’

Dicky gave the tiniest chuckle and rubbed his hands together. ‘Out of a job since he tried to take over my desk and failed. That’s what you mean, isn’t it?’

‘Was he after your desk?’ I said innocently, although Dicky had been providing me with a blow-by-blow account of Bret’s tactics and his own counterploys.

‘Jesus Christ, Bernard, you know he was. I told you all that.’

‘So what’s he got lined up now?’

‘He’d like to take over in Berlin when Frank goes.’

Frank Harrington’s job as head of the Berlin Field Unit was one I coveted, but it meant close liaison with Dicky, maybe even taking orders from him sometimes (although such orders were always wrapped up in polite double-talk and signed by Deputy Controller Europe or a member of the London Central Policy Committee). It wasn’t exactly a role that the autocratic Bret Rensselaer would cherish.

‘Berlin? Bret? Would he like that job?’

‘The rumour is that Frank will get his K. and then retire.’

‘And so Bret plans to sit in Berlin until his retirement comes round and hope that he’ll get a K. too?’ It seemed unlikely. Bret’s social life centred on the swanky jet setters of London South West One. I couldn’t see him sweating it out in Berlin.

‘Why not?’ said Dicky, who seemed to get a flushed face whenever the subject of knighthoods came up.

‘Why not?’ I repeated. ‘Bret can’t speak the language, for one thing.’

‘Come along, Bernard!’ said Dicky, whose command of German was about on a par with Bret’s. ‘He’ll be running the show; he won’t be required to pass himself off as a bricklayer from Prenzlauer Berg.’

A palpable hit for Dicky. Bernard Samson had spent his youth masquerading as just such lowly coarse-accented East German citizens.

‘It’s not just a matter of throwing gracious dinner parties in that big house in the Grunewald,’ I said. ‘Whoever takes over in Berlin has to know the streets and alleys. He’ll also need to know the crooks and hustlers who come in to sell bits and pieces of intelligence.’

‘That’s what you say,’ said Dicky, pouring himself more coffee. He held up the jug. ‘More for you?’ And when I shook my head he continued: ‘That’s because you fancy yourself doing Frank’s job … don’t deny it, you know it’s true. You’ve always wanted Berlin. But times have changed, Bernard. The days of rough-and-tumble stuff are over and done with. That was okay in your father’s time, when we were a de facto occupying power. But now – whatever the lawyers say – the Germans have to be treated as equal partners. What the Berlin job needs is a smoothie like Bret, someone who can charm the natives and get things done by gentle persuasion.’

‘Can I change my mind about coffee?’ I said. I suspected that Dicky’s views were those prevailing among the top-floor mandarins. There was no way I’d be on a short list of smoothies who got things done by means of gentle persuasion, so this was goodbye to my chances of Berlin.

‘Don’t be so damned gloomy about it,’ said Dicky as he poured coffee. ‘It’s mostly dregs, I’m afraid. You didn’t really think you were in line for Frank’s job, did you?’ He smiled at the idea.

‘There isn’t enough money in Central Funding to entice me back to Berlin on any permanent basis. I spent half my life there. I deserve my London posting and I’m hanging on to it.’

‘London is the only place to be,’ said Dicky. But I wasn’t fooling him. My indignation was too strong and my explanation too long. A public school man like Dicky would have done a better job of concealing his bitterness. He would have smiled coldly and said that a Berlin posting would be ‘super’ in such a way that it seemed he didn’t care.

I’d only been in my office for about ten minutes when I heard Dicky coming down the corridor. Dicky and I must have been the only ones still working, apart from the night-duty people, and his footsteps sounded unnaturally sharp, as sounds do at night. And I could always recognize the sound of Dicky’s high-heeled cowboy boots.

‘Do you know what those stupid sods have done?’ he asked, standing in the doorway, arms akimbo and feet apart, like Wyatt Earp coming into the saloon at Tombstone. I knew he would get on the phone to Berlin as soon as I left the office; it was always easier to meddle in other people’s work than to get on with his own.

‘Released him?’

‘Right,’ he said. My accurate guess angered him even more, as if he thought I might have been party to this development. ‘How did you know?’

‘I didn’t know. But with you standing there blowing your top it wasn’t difficult to guess.’

‘They released him an hour ago. Direct instructions from Bonn. The government can’t survive another scandal, is the line they’re taking. How can they let politics interfere with our work?’

I noted the nice turn of phrase: ‘our work’.

‘It’s all politics,’ I said calmly. ‘Espionage is about politics. Remove the politics and you don’t need espionage or any of the paraphernalia of it.’

‘By paraphernalia you mean us. I suppose. Well, I knew you’d have some bloody smart answer.’

‘We don’t run the world, Dicky. We can pick it over and then report on it. After that it’s up to the politicians.’

‘I suppose so.’ The anger was draining out of him now. He was often given to these violent explosions, but they didn’t last long providing he had someone to shout at.

‘Your secretary gone?’ I asked.

He nodded. That explained everything – usually it was his poor secretary who got the brunt of Dicky’s fury when the world didn’t run to his complete satisfaction. ‘I’m going too,’ he said, looking at his watch.

‘I’ve got a lot more work to do,’ I told him. I got up from my desk and put papers into the secure filing cabinet and turned the combination lock. Dicky still stood there. I looked at him and raised an eyebrow.

‘And that bloody Miller woman,’ said Dicky. ‘She tried to knock herself off.’

‘They didn’t release her too?’

‘No, of course not. But they let her keep her sleeping tablets. Can you imagine that sort of stupidity? She said they were aspirins and that she needed them for period pains. They believed her, and as soon as they left her alone for five minutes she swallowed the whole bottle of them.’

‘And?’

‘She’s in the Steglitz Clinic. They pumped her stomach; it sounds as if she’ll be okay. But I ask you … God knows when she’ll be fit enough for more interrogation.’

‘I’d let it go, Dicky.’

But he stood there, obviously unwilling to depart without some further word of consolation. ‘And it would all happen tonight,’ he added petulantly, ‘just when I’m going out to dinner.’

I looked at him and nodded. So I was right about an assignation. He bit his lip, angry at having let slip his secret. ‘That’s strictly between you and me of course.’

‘My lips are sealed,’ I said.

And the Controller of German Stations marched off to his dinner date. It was sobering to realize that the man in the front line of the western world’s intelligence system couldn’t even keep his own infidelities secret.