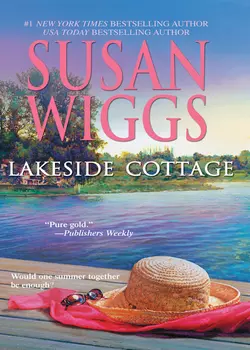

Lakeside Cottage

Susan Wiggs

IF YOU TRUST YOUR HEART, YOU’LL ALWAYS KNOW WHO YOU ARE…Each summer, Kate Livingston returns to her family’s lakeside cottage, a place of simple living and happy times – a place where she hopes her son, Aaron, can blossom. But her quiet life gets a bit more interesting with the arrival of a mysterious new neighbour, JD Harris.JD has a good reason for being secretive. In a moment of sheer bravery, the Washington, D. C. , paramedic prevented a terrible tragedy – and became a national hero. He’s hardly able to remember who he was before the media frenzy… until he escapes to this lovely, remote part of the Northwest.Now Kate and Aaron have rekindled the joy of small pleasures and peace, something JD thought he’d never have again. But how long will his blissful anonymity last before reality comes banging at his door?

Praise for the novels of SUSAN WIGGS

“True and unforgettable.”

—Booklist on Lakeside Cottage

“Wiggs excels at portraying the delicate dynamics

among lovers, friends and family members,

and her keen awareness of sensory detail

ensures that the scents and sounds of Rosa’s kitchen

are just as palpable as the heady attraction

between the protagonists.”

—Publishers Weekly on Summer by the Sea

“A human and multilayered story exploring duty

to both country and family.”

—Nora Roberts on The Ocean Between Us

“Susan Wiggs tackles contemporary issues

in the crucible of family with gutsy poignancy

and adroit touches of whimsy that make

for an irresistible read.”

—BookPage on Home Before Dark

“Wiggs tackles some very difficult family issues

in this tightly woven tale. Cleverly uncovering secrets

at the perfect pace, she draws you into the tale

with each passing page, allowing her characters’

emotions and motivations to flow out of the book

and into your heart.”

—RT Book Reviews on Home Before Dark

“Home Before Dark is a beautiful novel, tender and wise. Susan Wiggs writes with bright assurance, humor and compassion about sisters, children and the sweet and heartbreaking trials of life—about how much better it is to go through them together.” —New York Times bestselling author Luanne Rice

Also by SUSAN WIGGS

TABLE FOR FIVE

SUMMER BY THE SEA

THE OCEAN BETWEEN US

A SUMMER AFFAIR

HOME BEFORE DARK

ENCHANTED AFTERNOON

PASSING THROUGH PARADISE

HALFWAY TO HEAVEN

THE YOU I NEVER KNEW

The Chicago Fire trilogy

THE FIREBRAND

THE MISTRESS

THE HOSTAGE

THE HORSEMASTER’S DAUGHTER

THE CHARM SCHOOL

THE DRIFTER

THE LIGHTKEEPER

Author’s Note

Dear Reader,

Thank you for spending time at the lake with Kate, JD and the kids. Lake Crescent in the Olympic Peninsula is truly one of the most magical places in the world. I hope your own summers are filled with as much love and personal discovery as Kate’s was.

Researching Callie’s story line was an eye-opener for me. According to the Centers for Disease Control, over the last five years there has been a tenfold increase in type 2 diabetes among children. This is due in large part to a sugar-rich diet (think about how many soft drinks some kids consume each day) and a sedentary lifestyle (all those hours online, playing video games or watching TV). Teenagers also tend to disregard the long-range consequences of their behavior, and they’re notorious for putting off lifestyle changes for another day. A life-threatening disease like diabetes directly contradicts a teen’s illusion that she’s invincible. The good news is, diet and exercise will dramatically improve a young person’s prognosis. Simply participating in a sport or even taking a daily walk or bike ride can change a patient’s life. She can achieve glycemic control through exercise and healthy eating. For more information, I recommend the Web site www.diabetes.org and the book In Control: A Guide for Teens With Diabetes by Jean Betschart-Roemer and Susan Thorn.

My next novel, Just Breathe, is the story of a woman whose marriage ends just as new life begins, when she discovers she’s pregnant with twins. Events take an unexpected turn when she escapes to her hometown by the sea, where she discovers that love can be even sweeter the second time around.

Best wishes,

Susan Wiggs

www.susanwiggs.com

Lakeside Cottage

Susan Wiggs

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

To Martha Keenan, my editor and dear friend,

who shepherded twelve of my books to

publication. Thanks for everything.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Heartfelt thanks to my first readers, the Port Orchard Brain Trust: Rose Marie, Lois, Susan P., Krysteen, P.J., Anjali, Kate and Sheila. I’m grateful to Lori Cross, the best reader and proofreader in the world. I am indebted to paramedic and writer Andy Gienapp, and to the Office of Public Affairs of Walter Reed Army Medical Center—per your request, I’ve fictionalized significant details about the hospital layout and security routine so no one gets in trouble.

I’m grateful to Annelise Robey of the Jane Rotrosen Agency for her input. And to my agent, Meg Ruley—thanks for being a true believer.

PART ONE

“… as you all are aware, the President looks forward to visiting some of our brave troops at Walter Reed on Christmas Eve. It’s an opportunity for the President to thank those in our military who have served and sacrificed to make the world a safer place, and make America more secure. He will also give remarks to the medical personnel at Walter Reed and thank them for the outstanding job they do. However, because of the space limitations, it will be an expanded pool. So it will probably just be one camera, and then the correspondents will be able to attend it ….”

—The White House, Office of the Press Secretary

“Everybody loves a hero. People line up for them, cheer them, scream their names. And years later tell how they stood for hours in the cold rain just to catch a glimpse of the one who taught them to hold on a second longer. I believe there’s a hero in all of us who keeps us honest, gives us strength, makes us noble, and finally allows us to die with pride, even though sometimes we have to be steady, and give up the thing we want the most. Even our dreams.”

—Spider-Man 2

One

Washington, D.C. Christmas Eve

The ambulance backing into the bay of Building One looked like any other rig. It appeared to be returning from a routine transport run, perhaps moving a patient to the stepdown unit, or a stabilized trauma victim to Lowery Wing for surgery. The rig had its customary clearance tags for getting through security with a minimum of hassle, and the crew wore the usual crisply creased navy trousers and regulation parkas, ID tags dangling from their pockets. Even the patient looked ordinary in every respect, in standard-issue hospital draping, thermal blankets and an O

mask.

Special Forces Medical Sergeant Jordan Donovan Harris wouldn’t have given the crew a second glance, except that he was bored and had wandered over to Shaw Wing, to the glassed-in observation deck on the mezzanine level. From there, he could view the ambulance bays and beyond that, Rock Creek Park and Georgia Avenue. The trees were bare and stark black against a blanket of snow, ink drawings on white paper. Traffic trundled along streets that led to the gleaming domes and spires of the nation’s capital. A fresh dusting of powder over the 147-acre compound gave the Georgian brick buildings of the Walter Reed Army Medical Center a timeless, frozen, Christmas-card look. Only the activity at the intake bays hinted that the campus housed the military’s highest level of patient care.

Although there was no one around, Harris knew he was being watched. There were more security cameras here than in a Las Vegas casino. It didn’t matter to him, though. He had nothing to hide.

Boredom was desirable in the life of a paramedic. The fact that he was idle meant nothing had gone wrong, no one’s world had been shattered by a motor-vehicle accident, an unfortunate fall, a spiking fever, an enraged lover with a gun. For the time being, no one needed saving. Yet for a medic, whose job was to save people, that meant there was nothing to do.

He shifted his stance, grimacing a little. His dress shoes pinched. All personnel present wore dress uniform today because the President was on the premises to visit ailing soldiers and spread holiday cheer. Of course, only a lucky few actually saw the Commander-in-Chief when he visited. His rounds were carefully orchestrated by the powers that be, and his entourage of Secret Service agents and the official press corps kept him walled off from ordinary people.

So Harris was a bit startled when he saw a large cluster of black suits and military brass exiting the main elevator below the mezzanine. Odd. The usual route for official visits encompassed Ward 57, where so many wounded veterans lay. Today it seemed the tour would include the in-processing unit, which had recently undergone renovations courtesy of a generous party donor.

The visitors flowed along a spotless corridor. Instinctively, Harris stiffened his spine and prepared to snap to, not that anyone would notice whether or not he did. Old habits died hard.

He let himself relax a little. From his glassed-in vantage point, he craned his neck for a glimpse of the world leader but saw only the press and bustle of the entourage, led by the sergeant major of the army. A moment later, a civilian administrator greeted everyone with a wide smile. She looked as gracious and welcoming as a Georgetown hostess. Apparently, her domain was on the itinerary and she appeared eager to point out its excellence.

Harris knew that her name was Darnelle Jefferson and that she had worked here for a quarter of a century. She was fond of telling that to anyone who would listen. Looking at her, you’d never guess what the regulars here knew—that like many civilian administrators, she tended to spend her entire day being a pain in the ass to all personnel and creating a mountain of paperwork to justify her own existence. Still, she looked cheerful and efficient in a Christmas-red dress with the requisite yellow ribbon pinned to her bosom, and the wattage of her smile increased as the impossible occurred. The President separated from the pack and stepped forward for a photo op.

Then, even more surprisingly, Mrs. Jefferson took charge of the tour, leading the group along the wide, gleaming corridor. Two cameramen trolled along beside them, the big lenses of their cameras capturing every movement and nuance for the nightly news. The party stopped off at the first intake room, where a wounded soldierhad arrived from another facility. Harris knew that the official photos and film would portray the President with the soldier and his family in an intimate circle around the hospital bed. The pictures wouldn’t show the vigilant Secret Service, or the booms and mikes hovering just out of sight.

That’s showbiz, thought Harris. He didn’t understand how anyone could put up with public life. To have everyone’s scrutiny on you was a peculiar sort of torture, as far as he was concerned.

The entourage was on the move again, down the scrubbed hallway toward the Talbot Lounge, one of the newly renovated waiting areas, where a twelve-foot noble fir stood, decked in splendor by one of D.C.’s finest florists. They stopped for more photos. Harris could see flashes going off, but he’d lost sight of the President.

Elsewhere in the same wing, the recently delivered patient lay in an intake room flanked on two sides by wire-embedded glass walls. The transport crew had gone to the main desk to fill out their report, and no hospital personnel had arrived yet to in-process the newcomer. The staff members on duty were probably just like Harris, slacking off as they tried to get a look at the President. The patient lay alone, no family member or friend standing by to comfort him in this strange new world. Some people just didn’t have anybody. Harris himself might be a prime example of that, if not for Schroeder. He and Sam Schroeder had been best friends for years, since meeting in a battle zone in Konar Province, Afghanistan. Sam and his family made up all that was important to Harris, and he told himself it was enough.

He took the stairs down to the main level, hoping to get a look at the President’s face. He didn’t know why. Maybe it was the fact that he’d spent a decade serving this country and another four years at the hospital, keeping people from dying. He sure as hell ought to be able to catch a glimpse of the President up close. A memo had advised that there would be a reception later at the hospital rec center—with the Gatlin Brothers performing—but that was sure to be a mob scene.

A pair of marines in dress blues stood sentinel at the double doors to the unit. Harris gestured with his clipboard and flashed his ID, projecting an air of brisk efficiency. Once inside the unit, he had to act busy or they’d know he was loitering in order to see the President, a practice that was frowned upon.

Harris stopped outside the admittance room where the new arrival lay. He took a chart from the U-shaped holder on the door, flipped up the metal cover and pretended to be studying it.

The sound of footsteps and voices grew louder as the presidential party approached.

“… new Cardiothoracic Stepdown Unit is equipped with state-of-the-art monitoring equipment,” Mrs. Jefferson explained in broad, grave tones. “It’s now our country’s leading center of clinical care, research and evaluation.” She droned on as though reading from a prepared script, and Harris tuned her out.

The party drew closer. Finally Harris caught a glimpse of the Commander-in-Chief. His expression was set in his trademark look of compassion, one that had endeared him to the nation for two terms. The President and the hospital administrator separated from the group. Darnelle Jefferson led the way toward the in-processing unit where the new arrival lay.

Damn, thought Harris, time to disappear. Quickly—but not too quickly—he slipped into an admit room, connected to the unit by a set of green swinging doors. By looking through the round portals, he could see straight through to the next two rooms. He focused on the new patient through the glass, expecting him to be lying there quiet and alone, probably scared shitless, unaware that the President of the United States was just a few steps away.

Except that the guy wasn’t quiet. For a cardiac patient, he seemed awfully busy, sitting up on the gurney, tearing away his mask.

Harris studied the chart he’d grabbed from the rack outside the door. Terence Lee Muldoon. He was a combat vet, a transferee from a U.S. military hospital in Landstuhl, Germany. The chart listed him as twenty-five years old—damn young for heart trouble.

In his time, Harris had seen thousands of cardiac patients. The condition was always characterized by a grayish pallor and palpable look of fatigue.

Not this character. Even from a distance and through two sets of doors, Harris could see that his face was a healthy pink, his movements economical and assured.

At that moment, the entourage stopped in the corridor and the President and Mrs. Jefferson entered Muldoon’s room. The glassed-in cubicle was too small to accommodate more visitors, and the bodyguards hovered outside, craning their necks, their gazes constantly on the move, their lips murmuring into their hidden radios. A pair of photographers pressed their camera lenses against the glass. The President greeted Muldoon with a handshake, then moved behind the gurney for the requisite photo op.

There was never a specific moment when Harris decided something was wrong. He never saw a maniacal gleam in the impostor’s eyes or heard some sort of evil cackle like in the movies. Real evil didn’t work that way. It was all quite … ordinary.

Sweet baby Moses, thought Harris.

There was also never a particular moment when Harris decided to take action. Making a decision implied a thought process that simply didn’t happen. Harris—and the unsuspecting President—had no time for that. Flipping the silent alert signal on his shoulder-mounted radio, he slipped through the double doors into the next in-processing room, adjacent to where the President was. He knew the security cameras were recording his movements, but the stranger next door didn’t appear to have noticed him.

Harris refrained from shouting or making any sudden movements. The patient was not yet aware of him, and he didn’t want to draw attention to himself. He had to move fast, though, because his movements were going to look highly suspicious to the security cameras. Those watching him were going to think he was a nutcase or worse—a bad guy.

The flow of events unfolded with a peculiar inevitability. Later—much, much later—Harris would watch the videos made by both the security monitors and the press corps, but he would remember none of it.

Seconds before the personnel in the hallway responded to the alert, the patient swept aside the thermal blanket. With his free hand, he yanked away the gown to reveal rows of dynamite duct taped to a body-hugging vest.

“Anybody takes me out,” he screamed at the glass wall, “and I go up like the Fourth of July. And I take this whole wing of the building with me.” He leaped to the floor and glared at the horrified crowd on the other side of the glass. His fist closed around the igniter, ready to detonate the explosives.

The President stood stock-still. Darnelle Jefferson gave a hiccuping gasp of sheer terror. Harris froze, too experienced to let fear get in the way. He recognized the shield tattooed on Muldoon’s forearm. It was the iron falcon and sword of a Special Forces unit.

So they were dealing with a rogue from Special Forces, as highly trained as Harris himself, a disciplined killer gone awry. The assassin hadn’t seen him yet. He was strutting in front of the wire-embedded glass while a dozen firearms were aimed at him.

Harris studied the homemade explosive vest and wondered how the hell the transport crew had failed to notice it. The explosives appeared to be plastic ordnance with an igniter operated by a toggle mechanism secured with more duct tape and connected to wires that would activate the explosives. It would have to be detonated manually, unless there was a secondary trigger he wasn’t seeing.

Outside the cubicle, bodyguards and marines broke into action. Honed by countless drills, procedure would be followed to the letter. There would be an immediate lockdown, all units would come to full alert and alarms would shriek across the vast, snowy campus of Walter Reed. Even now, a security squadron was probably surrounding the building.

Mrs. Jefferson made a tiny sound for such a big woman and fainted dead away, taking a Lifepak monitor along with her. It crashed to the floor, startling Muldoon, and Harris was sure he’d spook and ignite the explosives. His left hand, which had been gripping the manual trigger, let go momentarily as he regrouped.

Darnelle had given Harris a seconds-long window of opportunity. Knowing he had a chance was all he needed. It was only one chance, though. If he blew it, they were all toast. Or confetti, more accurately.

He burst through the double doors, everything focused on the assailant’s trigger hand. His entire body launched itself at the assassin in a single-move tactic, one he’d been trained for but had never used until now.

Muldoon went down, screaming as Harris crushed the man’s left wrist to disable his hand. They hit the floor together. Muldoon was shocky from the crushed wrist. That was something.

There was a sound like a rifle shot. Harris felt something hit him like a cannonball. Jesus, had the son of a bitch detonated the explosives?

No, the igniter, Harris realized. The impact had triggered it, but it had misfired. That was the good news. The bad news was, the failed explosion was killing him. His limbs went immediately ice cold as if everything had been sucked out of him. He was aware of movement all around, the President taking cover, the frenzy of highly trained Secret Service men jolted into action. Alarms bayed and someone was screaming. A furious ringing sound blared in his ears. The reek of chemicals seared his throat.

The world dissolved into double images as Harris’s consciousness seeped away like the blood on the floor. Sounds stretched out with an eerie echo, as though shouted down a well. “Freeze … freeze, freeze….” The barked order reverberated through Harris’s head. “Nobody move! oove, oove….”

Harris’s pulse was thready. Lying in a widening pool of blood, he imagined each system shutting down, one by one, a theater’s lights going dim after a final performance. He felt himself quiver, or maybe it was the assassin struggling against him. To die like this, he thought, at the President’s feet. That just sucked. Offended his sense of propriety. Sure, it wouldn’t matter to him after he was gone. It shouldn’t matter at all, but somehow it did.

Harris could see his own reflection in the dome of the 360-degree security camera mounted in the ceiling. Blood spreading out like an inky carpet. It always looks worse than it is, he told himself. He said that to his patients all the time.

The swarm descended, a pandemonium of black suits and dress uniforms as the Secret Service came forward to apprehend the crazy and secure the chief executive.

Harris was cold and headed somewhere dark. He could feel himself slipping, falling into a black well.

“Make way,” a loud voice barked, the words echoing, then fading. “Somebody get this man some help.”

PART TWO

“The best way to escape from a problem is to solve it.”

—Alan Saporta, American musician

Two

Port Angeles, Washington Summer

“It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single woman in possession of a half-grown boy must be in want of a husband.” Squinting through her vintage cat’s-eye glasses, Mable Claire Newman defied Kate Livingston to contradict her.

“Very funny,” Kate said. “You tell me this every year.”

“Because every summer, you come back here, still single.”

“Maybe I like being single,” Kate told her.

Mable Claire aimed a look out the window of the property management office at the half-grown boy and his full-grown beagle, playing tug-of-war with a sock in Kate’s Jeep. “Are you at least dating someone?”

“Dating I can manage. It’s getting them to come back that seems to be the problem.” Kate offered a self-deprecating grin, an almost jaunty grin, just wide enough to hide behind. Men were often startled to discover she was a mother; she’d had Aaron at twenty and had always looked young for her age. And when they saw what a handful her boy was, they tended to head straight for the door.

“They’re nuts, then. You just haven’t run into the right fellow.” Mable Claire winked. “There’s a guy staying at the Schroeder place you ought to meet.”

Kate gave an exaggerated shudder. “I don’t think so.”

“Wait until you see him. You’ll change your mind.” She opened a cupboard with an array of tagged house keys and found the one marked with Kate’s name. “I didn’t expect you until tomorrow.”

“We decided to come up a day early,” Kate said, hoping there would be no further questions. Though Mable Claire had known Kate through all the summers of her life, she wasn’t ready yet to talk about what had happened. “I hope that’s okay.”

“Nothing wrong with starting the summer a day early. The housekeeping and yard crew have already been to your place. School out already?” she asked, tilting her head for a better view of Kate’s boy through the window. “I thought the kids had another week.”

“Nope. The final bell rang at three-fifteen yesterday, and third grade is just a bad memory for Aaron now.” Kate dug through her purse, looking for her key chain. Her bag was littered with small notes to herself because she never trusted her own memory. Besides, this made her feel organized and in control, whether or not she actually was. She had a number of projects lined up for the summer. She needed to re-grout the downstairs bathroom tile at the cottage. Paint the exterior trim. Not to mention renewing the bond with her son, reinventing her career and finding herself.

In that order of importance? She had to wonder at her priorities.

“So are you going to be all right,” Mable Claire asked, “just the two of you in that big old house?”

“We’ll be fine,” Kate said, though it felt strange to be the only one in the family headed for the lake house this summer. Every year, all the Livingstons made their annual pilgrimage to the old place on Lake Crescent, but recently everything had changed. Kate’s brother, Phil, his wife and four kids had relocated to the East Coast. Their mother, five years widowed, had remarried on Valentine’s Day and moved to Florida. That left Kate and Aaron in their house in West Seattle, on their own a continent away. Sometimes it felt as though an unseen force had taken her close-knit family and unraveled it.

This summer it would be just the two of them—Kate and her son—sharing the six-bedroom cottage.

Quit wallowing, she warned herself, and smiled at Mable Claire. “How have you been?” she asked.

“Good, all things considered.” Mable Claire had lost her husband two years before. “Some days—most days—I still feel married, like Wilbur never really left me. Other times, he seems as distant as the stars. I’m all right, though. My grandson Luke is spending the summer with me. Thanks for asking.”

On the form to activate trash pickup, Kate filled in the dates. The summer loomed before her, deliciously long, a golden string of empty days to fill however she wished. A whole summer, all to herself. She could take the entire time to figure out her life, her son, her future.

Mable Claire peered at her. “You’re looking a little peaked.”

“Just frazzled, I think.”

“Nothing a summer at the lake won’t cure.”

Kate summoned up a smile. “Exactly.” But suddenly, one summer didn’t seem like enough time.

“‘In want of a husband,’ my eye,” Kate muttered as she locked the Jeep at the Shop and Save, leaving the window cracked to give Bandit some fresh air. Aaron was already scurrying toward the entrance. Heck, thought Kate, watching a guy cross the parking lot, at this point I’d settle for a one-night stand.

He was a prime specimen in typical local garb—plaid shirt, Carhartts, work boots, a John Deere cap. Tall and broad-shouldered, he walked with a commanding, almost military stride. Longish hair and Strike King shades. But was that a mullet under the green-and-yellow cap? From a distance, she couldn’t tell. Ick, a mullet. It was only hair, she conceded. Nothing a quick snip of the scissors couldn’t fix.

“Mom? Mom.” A voice pierced her fantasy. Aaron rattled the cart he’d found in the parking lot.

“You’re acting like an impatient city dweller,” she said.

“I am an impatient city dweller,” he replied.

They passed beneath the sign of the giant laughing pink pig, which had stood sentinel over the grocery store for as long as Kate could remember. The marquee held a sign that advertised, Maple Sweet Bacon—$.99/lb.

What are you so happy about? Kate wondered, looking at the pig. She and Aaron went inside together to stock up on supplies, for the lake house had sat empty since last year. Something in Kate loved this process. It was like starting from scratch, with everything new. And this time, all the choices were hers to make. Without her mother or older brother around, Kate was the adult in charge. What a concept.

“Mom? Mom.” Aaron scowled at her. “You’re not even listening.”

“Oh. Sorry, buddy.” She selected some plums and put them in the cart. “I’m a bit preoccupied.”

“Tell me about it. So did you get fired or were you laid off?” he asked, hitching a ride on the grocery cart as she steered toward the next aisle. He regarded her implacably over the pile of cereal boxes and produce bags.

She looked right back at her nine-year-old son. His curiously adult-sounding question caught her off guard. “Maybe I quit,” she said. “Ever think of that?”

“Naw, you’d never quit.” He snagged a sack of Jolly Ranchers from a passing shelf and tossed them into the cart.

Kate put the candy back. Jolly Ranchers had yanked out more dental work than a bad dentist. “Why do you say I’d never quit?” she asked, taken aback. As he grew older, turning more and more into his own person, her son often said things that startled her.

“Because it’s true,” he said. “The only way you’d ever quit on your own is if something better came along, and I know for a fact that it hasn’t. It never does.”

Kate drummed her fingers on the handle of the shopping cart, the clear plastic scratched with age. She turned down the canned-goods aisle. “Oh, yeah?” she asked. “What makes you so darned sure?”

“Because you’re freaking out,” he informed her.

“I am not freaking out,” said Kate.

Oh, but she was. She absolutely was. At night, she walked the floors and stared out the window, often staying up so late she could see the lights of Seattle’s ferry terminals go out after the last boat came into the dock. That was the time she felt most alone and most frightened. That was when Kate the eternal optimist gave way to Kate in the pit of despair. If she had any interest in drinking, this would be the time to reach for a bottle. L’heure bleue, the French called it, the deep-blue hour between dark and dawn. That was when her relentlessly cheerful façade fell away and she engaged in something she hated—wallowing. This was her time to reflect on where she’d been and where she was going. This was when her lonely struggle to raise Aaron felt almost too hard to carry on. By the time the sun came up each morning, she snapped herself out of it and faced the day, ready to soldier on.

“We should get stuff marked with the WIC sticker,” Aaron advised, pointing out a green-and-black tag under a display of canned tuna.

She put back the can of albacore as though it had bitten her. “Why on earth would you say that?”

“Chandler told me his mother gets tons of stuff with WIC. Women, Infants and Children,” he explained. “It’s a feld … fed … Some kind of program for poor people.”

“We are not poor people,” Kate snapped.

She didn’t realize how loudly she’d spoken until a man at the end of the aisle turned to look at her. It was the same one she’d stared at in the parking lot, only he was much closer now. Beneath a five-o’clock shadow, she could make out a strong, clean jawline. He had traded the shades for a pair of horn-rimmed glasses, one side repaired with duct tape. In the split second that she met his gaze, she observed that his eyes had the depth and color of aged whiskey. But duct tape? Was he a loser? A nerd?

She whipped around to hide her flaming cheeks and shoved the cart fast in the other direction.

“See?” Aaron said. “This is how I know you would never quit your job. You get too embarrassed about being poor.”

“We are not—” Kate forced herself to stop. She took in a deep, calming breath. “Listen, bud. We are fine. Better than fine. I wasn’t getting anywhere at the paper, and it was time to move on, anyway.”

“So are we poor or not?”

She wished he would lower his voice. “Not,” she assured him.

In reality, her salary at the paper was barely a living wage, and the majority of her income came from the Seattle rental properties left to her by her father. Still, the job had defined her. She was a writer, and now that she’d been let go, she felt as though the rug had been ripped out from under her. “This means we get to spend the whole summer together, just the two of us.” She studied Aaron’s expression, spoke up before he turned too forlorn. “You got a problem with that?”

“Yeah,” he said with a twinkle of mischief in his eye. “Maybe I do.”

“Smart aleck.” She tugged the bill of his Seattle Mariners baseball cap down over his eyes and pushed onward. Lord, she thought, before she knew it, her little red-haired, freckle-faced boy would be as tall as she was.

The storm of his mood struck as it always did, without warning and no specific trigger. “This is stupid,” he snapped, his eyes narrowing, the color draining from his face. “It’s going to be a stupid, boring summer and I don’t even know why I bothered to come.”

“Aaron, don’t start—”

“I’m not starting.” He ripped off his hat and hurled it to the floor in the middle of the aisle.

“Good,” she said, trying to keep her voice emotionless, “because I have shopping to do. The quicker we finish, the quicker we get to the lake.” “I hate the lake.”

Hoping they hadn’t attracted any more attention, she steered the cart around him and fumbled through the rest of the shopping without letting on how shaken she was. She refused to allow his inability to control his behavior control her. When would it end? She had consulted doctors and psychologists, had read hundreds of books on the topic, but not one could ever give her the solution to Aaron’s temper and his pain. So far, the most effective solution appeared to be time. The minutes seemed endless as she worked her way up and down the aisles, ignoring him the whole time. Sometimes she wished she could get into his head, find the source of his pain and make it better. But there was no Band-Aid or salve for the invisible wounds he carried. Well-meaning people claimed he needed a father. Well, duh, thought Kate.

“Mom,” said a quiet, contrite voice behind her. “I’m sorry, Mom. I’ll try harder not to get all mad and loud.”

“I hope so,” she said, her heart quietly breaking, as it always did when they struggled. “It’s hurtful and embarrassing when you lose your temper and yell like that.”

“I know. I’m sorry,” he said again.

She knew a dozen strategies, maybe more, for where to go with this teachable moment. But they’d just driven three hours from Seattle, and she was anxious to get to the cottage. “We need stuff for s’mores,” she said.

Relief softened his face and he was himself again, eager-to-please Aaron, the one the teachers at his school saw so rarely. His storms were intense but quickly over, with no lingering bitterness.

“I’ll go,” he said, and headed off on the hunt.

Some practices at the lake house were steeped in tradition and ancient, mystical lore. Certain things always had to be done in certain ways. S’mores were just one of them. They always had to be made with honey grahams, not cinnamon, and the gooey marshmallow had to be rolled in miniature M&Ms. Nothing else would do. Whenever there was a s’mores night, they also had to play charades on the beach. She made a mental list of the other required activities, wondering if she’d remember to honor them all. Supper had to be announced each evening with the ringing of an old brass ship’s bell suspended from a beam on the porch. Come July, they had to buy fireworks from the Makah tribe’s weather-beaten roadside stand, and set them off to celebrate the Fourth. To mark the summer solstice, they would haul out and de-cobweb the croquet set and play until the sun set at ten o’clock at night, competing as though life itself depended on the outcome. When it rained, the Scrabble board had to come out for games of vicious competition. This summer, Aaron was old enough to learn Hearts and Whist, though with just the two of them, she wasn’t sure how they’d manage some of the games.

All the lakeside-cottage traditions had been invented before Kate was born, and were passed down through generations with the solemnity of ancient ritual. She noticed that Aaron and his cousins—her brother Phil’s brood—embraced the traditions and adhered to them fiercely, just as she and Phil had done before them.

Aaron came back with the crackers, miniature M&Ms and marshmallows.

“Thanks,” she said, adding them to the cart. “I think that’s about it.” As she trolled through the last aisle, she noticed the guy in the John Deere cap again, studying a display of fishing lures. This time Aaron spotted him, too. For a moment, the boy’s face was stripped of everything except a pained combination of curiosity and yearning as he sidled closer. The guy hooked his thumb into the rear pocket of his pants, and Aaron did the same. The older he got, the more Aaron identified with men, even strangers in the grocery store, it seemed.

Then she caught herself furtively studying the object of Aaron’s attention, too. The stranger had the oddest combination of raw masculine appeal and backwoods roughness. She wondered how much he’d overheard earlier.

Snap out of it, she thought, moving the cart to the checkout line. She didn’t give a hoot about what this Carhartt-wearing, mullet-sporting local yokel thought of her. He looked like the kind of guy who didn’t have a birth certificate.

“Aaron,” she said, “time to go.” She turned away to avoid eye contact with the stranger, and pretended to browse the magazine racks. This was pretty much the extent of her involvement with the news media. It was shameful, really, as she considered herself a journalist. She didn’t watch TV, didn’t read the papers, didn’t act like the thing she said she was. This was yet another personal failing. Thanks to her late unlamented job, her work had consisted of nothing more challenging than observing Seattle’s fashion scene.

People magazine touted a retrospective: “Reality TV Stars—Where Are They Now?”

“A burning issue in my life, for sure,” Kate murmured.

“Let’s get this one about the two-headed baby.” Aaron indicated one of the tabloids. Kate shook her head, although her eye was caught by a small inset photo of a guy with chiseled cheeks and piercing eyes, a military-style haircut and dashing mustache. American Hero Captured by Terrorist Cult, proclaimed the headline.

“Let’s get a TV Guide,” Aaron suggested. “We don’t have a TV.”

“So I can see what I’m missing. Wait, look, Mom.” He snatched a newspaper from the rack. “Your paper.” He handed it over.

Kate’s hands felt suddenly and unaccountably cold, nerveless. She hated the pounding in her throat, hated the tremor of her fingers as she took it from him. It was just a stupid paper, she told herself. It was the Seattle News, a dumb little weekly crammed with items about local bands and poetry slams, film reviews and fluffy culture articles. In addition to production and layout, her specialty for the past five years had been fashion. She had generated miles of ink about Seattleites’ tendency to wear socks with Birkenstocks, or the relative merits of body piercing versus tattooing as a fashion statement.

Apparently not quite enough miles, according to Sylvia, her editor. Instead of a five-year pin for distinguished service, Kate had received a pink slip.

The paper rattled as she turned to page B1 above the fold. There, where her column had been since its debut, was a stranger’s face, grinning smugly out over the shout line. “Style Grrl,” the byline called her, the self-important trendi-ness of it setting Kate’s teeth on edge. Style Grrl, who called herself Wendy Norwich, was really Elsie Crump, who had only recently moved up from the mail room. Today’s topic was an urgent rundown of local spray-on tanning salons.

At the very bottom of the page, in tiny italic print, was the reminder, “Kate’s Fashion Statement is on hiatus.”

That was it. Her entire professional life summed up in six little words.

“What’s on hiya-tus mean?” Aaron asked.

“Kind of like on vacation,” she said, hating the thick lump she felt in her throat. She stuffed the paper back in the rack. Only I’m never coming back.

“Can I have this gum?” Aaron asked, clearly unaware of her inner turmoil. “It’s sugar free.” He showed her a flat package containing more baseball cards than bubble gum.

“Sure, bud,” she said, bending to unload her groceries onto the conveyor belt.

An older couple got in line behind her. It took no more than a glance for Kate to surmise that they’d been together forever. They had the sort of ease that came from years of familiarity and caring, that special bond that let them communicate with a look or gesture.

A terrible yearning rose up in Kate. She was twenty-nine years old and she felt as though one of the most essential joys of life was passing her by. She had never heard a man declare he loved her and mean what he said. She had no idea what it felt like to have a true partner, a best friend, someone to stay by her side no matter what. Yes, she had a son she adored and a supportive extended family. She was grateful for those things and almost ashamed to catch herself craving more, wishing things could be different.

Still, sometimes when she saw a happy couple together, embracing and lost in each other, she felt a deep pang of emptiness. Being in love looked so simple. Yet it had never happened to her.

Long ago, she’d believed with all her heart that she and Nathan had been in love. Too late, she found out that what she thought she had with him had no solid foundation, and when tested by the reality of her pregnancy, their relationship had broken apart, the pieces drifting away like sections of an ice floe.

As she unloaded the cart, Kate felt the John Deere guy watching her. She was sure of it, could sense those shifty eyes behind the glasses. He was two lanes over and his back was turned, but she knew darned well he’d been staring just a second ago. He was probably checking to see if she used food stamps.

None of your business, she thought. And you do too have a mullet. She glared at the broad, plaid shirt–covered shoulders.

She finished checking out, marveling at the amount of the bill. Ah, well. Starting over took a little capital up front. She swiped her debit card through the machine and got an error message. Great, she thought, and swiped it again. “Please wait for cashier,” the machine flashed.

“I don’t think my card’s working,” Kate said, handing it to her.

The cashier took it and put in the numbers manually. “I’m sorry, ma’am. The card’s been declined.”

Declined. Kate’s stomach dropped, but she fumbled for a smile. “I’ll write you a check,” she said, taking out her checkbook.

“We can only accept local checks,” the cashier said apologetically.

Kate glanced at the couple behind her. “I’ll pay in cash, then,” she muttered. “You do accept cash, right?”

“Have you got enough?” Aaron asked. His piping voice carried, and she knew the lumberjack guy could hear.

She pursed her lips and counted out four twenties, a ten and two ones, and thirty-three cents change. It was all the cash she had on hand. She looked at the amount on the cashier’s display. “Check your pockets, Aaron,” she said. “I’m two dollars and nine cents short.”

I hate this, she thought while Aaron dug in his Levi’s. I hate this.

She kept a bland smile in place, though her teeth were clenched, and she avoided eye contact with the cashier or with the couple behind her.

“I got a quarter and a penny,” Aaron said, “and that’s it.” He handed it over.

“I’ll have to put something back.” Kate wished she could just slink away. “I’m sorry,” she said to the older couple. She reached for the bag of Cheetos, their favorite guilty pleasure.

“Not the Cheetos. Anything but the Cheetos,” Aaron whispered through clenched teeth.

“Don’t do that,” said a deep, quiet voice behind her. “It’s covered.”

Even before Kate turned to look at him, she knew it was the guy. The mullet man, rescuing her.

She took a deep breath and turned. Go away, she wanted to tell him. I don’t need you. Instead, she said, “That’s not necessary—”

“Not a problem.” He handed two dollars to the cashier and headed out the door with his sack of groceries. “Hey, thanks,” said Aaron.

The man didn’t turn, but touched the bill of his cap as he went outside.

Thoroughly flustered, Kate helped sack the groceries and load them into the cart. She hurried outside, hoping to catch the guy before he left. She spotted him in a green pickup truck, leaving the parking lot.

“That was real nice of him, huh?” said Aaron.

“Yep.”

“You forgot to tell him thank-you.” “I didn’t forget. I was … startled, and then he took off before I could say anything.”

“You weren’t startled,” he said. “You were embarrassed.”

She opened her mouth to object. Then she let her shoulders slump. “Totally humiliated.” For Aaron’s sake, she summoned a smile. “I shouldn’t have said that. I should remind you that the kindness of strangers is a rare and wonderful thing.”

“A rare and wonderful and humiliating thing,” he said. “Help me load these groceries, smart aleck. Let’s see if we can get to the lake before the Popsicles melt.”

Three

Kate’s Jeep Cherokee had seen better days, but it was the perfect vehicle for the lake, rugged enough to take on the unpaved roads and byways that wound through the mountains and rain forests of the Olympic Peninsula. Bandit greeted them as though they’d been gone a year, sneezing and slapping the seat with his tail.

“Now to the lake,” Kate said brightly. “We’ve got the house all to ourselves, how about that?”

Aaron buckled his seat belt in desultory fashion, barely reacting to Bandit’s sloppy kisses, and she realized she’d said the wrong thing.

“It’s going to be a great summer,” she assured him.

“Right,” he replied without enthusiasm.

She could hear the apprehension in his voice. Though she wouldn’t say so aloud, she felt as apprehensive as Aaron.

He regarded her with disconcerting insight. “They fired you because of me, didn’t they?”

“No, I got fired because Sylvia is an inflexible stick of a woman who never appreciated real talent anyway. Deadlinesand the bottom line, that’s all she cares about.” Kate made herself stop. No point venting to Aaron; he already knew she was angry. The fact that Kate had been let go by Sylvia Latham, the managing editor, stung particularly. Like Kate, Sylvia was a single mother. Unlike Kate, she was a perfect single mother with two perfect kids, and because of this, she assumed everyone else could and should juggle career and family with the same finesse she did.

Kate ducked her head, hiding her expression. Aaron was clued in to much more than people expected of him. He knew as well as any other boy that one of the most basic realities of modern life was that a single mom missed work to take care of her kid. Why didn’t Sylvia get it? Because she had a perfect nanny to look after her perfect children. Until this past year, Aaron’s grandmother and sometimes his aunt watched him when he missed school. Now that they’d moved away, Kate tried to juggle everything on her own. And she’d failed. Miserably and unequivocally.

“I have to call the bank, figure out what’s the matter with my debit card,” she said, taking out her cell phone. “We don’t get reception at the lake.”

“Boooring,” Aaron proclaimed and slumped down in his seat.

“I’m with you, bud.” She dialed the number on the back of her card. After listening to all the options—”because our menu has recently changed,” cooed the voice recording—she had to press an absurd combination of numbers only to learn that the bank, on East Coast time, was already closed. She leaned her head against the headrest and took a deep, cleansing breath. “It’s nothing,” she assured Aaron. “I’ll sort it out later.”

“I need to call Georgie next,” she said apologetically.

All five grandkids—Phil and Barbara’s four, plus Aaron—called her mother Georgie and sometimes even Georgie Girl.

“Don’t talk long,” Aaron said. “Please.”

Kate punched in the unfamiliar new number and waited for it to connect. A male voice answered.

“This is Clinton Dow.” Georgie’s new husband always answered with courteous formality.

“And this is Katherine Elise Livingston,” she said, teasing a little.

“Kate.” His voice smoothed out with a smile she could hear. “How are you?”

“Excellent. We’re in Port Angeles, just about to head to the lake.”

“Sounds like a big adventure,” he said as jovially as could be. You’d never know that only last spring, he was urging her mother to sell the summer place. It was a white elephant, he’d declared, a big empty tax liability that had outlived its use to the family. With that one pronouncement, he had nearly lost the affections of his two newly acquired stepchildren. The lakeside cottage had been in the Livingston family since the 1920s, far longer than a once-widowed, once-divorced retired CPA.

“We’re never selling the lake house,” Phil had said. “Ever. End of discussion.” It didn’t matter to Phil that he had moved cross-country, all the way to New York, and that his visits would be few and far between. For him and Kate and their kids, the lakeside retreat held all that was special and magical about summer, and selling it would be sacrilege.

“I’ll get your mother,” Clint said. “It’s great to hear from you.”

While she waited, Kate pulled the Jeep around to the far edge of the parking lot so she could look out over the harbor. She had stood in this spot, regarding this view hundreds of times in her life. She never got tired of it. Port Angeles was a strange city, an eclectic jumble of cheap sportsman’s motels and diners, quaint bed-and-breakfast getaways, strip malls with peeling paint and buckled asphalt parking lots, waterfront restaurants and shops. A few times a day, the Coho ferry churned its crammed, exhausted hull across the Strait of Juan de Fuca to Victoria, British Columbia, in all its gleaming splendor, and vehicles waited for hours for a coveted berth on board.

“So you’re headed off into the wilderness,” her mother said cheerfully into the phone.

“Just the two of us,” Kate said.

“I wish you’d decided to bring Aaron here for the summer,” Georgina said. “We’re an hour’s drive from Walt Disney World, for heaven’s sake.”

“Which is precisely why I didn’t want to bring him,” Kate said. “I’m just not a Disney sort of gal.”

“And Aaron?”

“He’d love it,” she confessed. “He would love to see you, too.” She watched her son rifling through the groceries in search of something to eat. He found the sack of golden Rainier cherries and dived in, seeing how far he could spit each pit out the window. Bandit, who was remarkably polite when his humans were eating, watched with restrained but intense concentration. “We want to be here this summer,” she reminded her mother. “It’s exactly where we need to be.”

“If you say so.” Georgina had never loved the lakeside cottage the way the rest of the Livingstons did, though in deference to her late husband and children, she’d always been a good sport about spending every summer there. Now that she’d finally remarried, however, she was more than happy to stay in Florida.

“I say so,” Kate told her mother. “I can finally spend quality time with my boy, and figure out what I want to be when I grow up.”

“You’ll both go stir-crazy,” Georgina warned.

Kate thought about her mother’s new home, a luxury condo on a golf course in Florida. Now that would make a person stir-crazy.

She let Aaron say hello to his grandmother, and then she called Phil, but got his voice mail and left a brief message. “There,” she said. “I’ve checked in with everybody who matters.”

“That’s not very many.”

“It’s not the number of people. It’s how much they matter,” she explained. It made Kate wistful, thinking about how much she would miss her brother and his family this summer. She didn’t let it show, though. She wanted Aaron to believe this would be the summer of a lifetime. Sometimes she thought she’d give anything for a shoulder to cry on, but she wouldn’t allow her son to play that role. She’d seen other single moms leaning on their kids for emotional support, and she didn’t think it was fair. That was not what kids were for.

Last year, she’d consulted a “life coach,” who’d counseled her to be her own partner in parenting and life, encouraging her to have long, searching conversations with herself. It hadn’t helped, but at least she found herself talking to someone she liked.

“Ready?” she said to Aaron, putting away the phone. She eased the Jeep out of the parking lot and merged onto Highway 101, heading west. The forests of Douglas fir and cedar thickened as they penetrated deeper into the Olympic Peninsula. Soaring to heights of two hundred feet or more, the moss-draped trees arched over the two-lane highway,creating a mystical cathedral effect that never failed to enchant her. The filtered afternoon sunlight glowed with layers of green and gold, dappling the road with shifting patterns.

There was a sense, as they traveled away from the port city, of entering another world entirely. This was a place apart, where the silences were as vast and deep as the primal forests surrounding the lake. Thanks to the vigilance of the parks department, the character of the land never changed. Aaron was experiencing everything just as she and Phil had as children, and their father and grandparents before them. She remembered sitting in the back seat of their father’s old station wagon with the window rolled down, feeling the cool rush of the wind in her face and inhaling the fecund scent of moss and cedar. Four years her senior, Phil had a special gift for annoying her until she wept, though she had long since forgiven him for all the childhood torments. Somehow, seemingly by magic, her brother had turned into her best friend over the years.

Five miles from the lake, they passed the final hill where cell-phone reception was possible, in the parking lot of Grammy’s Café, which served the best marionberry pie known to man.

At the side of the road, she spotted a green pickup truck pulled off to the side. She slowed down as she passed, and saw that the driver was bent over the front passenger side, changing a tire, perhaps.

It was the John Deere guy. The one who had bailed her out at the grocery store.

She applied the brake, then put the car in Reverse and pulled off to the shoulder. She had no idea how to change a tire and he probably didn’t want or need her help. But she stopped just the same, because like it or not, she owed him one.

“What’re you doing?” Aaron asked.

“Stay put,” she said. “Don’t let Bandit out.” She got out and walked toward the truck.

Here, surrounded by the extravagant lushness of the fern-carpeted forest, he looked even more interesting than he had in the grocery shop, a man in his element. Suddenly she felt vulnerable. This was a lonely stretch of road, and if he decided to come on to her, she’d be in trouble. Her brother often accused her of being too naive and trusting, yet she didn’t know how else to be. She did trust people, and they seldom let her down.

“Keep away,” he called to her without looking up from what he was doing. “I’ve got a wounded animal here.”

Definitely not a come-on.

She saw a half-grown raccoon lying on its side, struggling and making a terrible noise. Wearing a pair of logging gloves, the guy was trying to bag the hissing, scratching creature in a canvas sack, but the raccoon was having none of it.

Ignoring orders, Aaron jumped out. Bandit whined from the Jeep.

Kate grabbed Aaron’s shoulder and held him next to her. “What can we do to help?”

“That’s—Damn.” The guy jumped back, examining his gloved hand.

“Did it bite you?” she asked.

“Tried to.”

“Did you hit it?” Aaron asked. His chin trembled. He absolutely hated it when an animal was injured.

“Nope. Found it like this,” the man said. For the first time, he took his eyes off the raccoon and turned to look at them. The sunglasses masked his reaction, but she could tell he recognized her from the grocery store. Something—a subtle tensing in his big, lean body—reacted to her.

“Is it going to die?” Aaron asked.

“Hope not. There’s a wildlife rehab station back in Port Angeles. If I can get it there, I’m pretty sure it can be saved.”

“How can he fight like that?” Kate said. “He’s half-dead.”

“Not even close. And the survival instinct is strong when something feels threatened.”

“Hey,” Aaron said, diving into the back of the Jeep. “You can use the Igloo.”

Kate helped him empty the forty-five-gallon cooler, which had plenty of room for a half-grown raccoon. Together, they pulled the cooler out and dragged it over, easing it over the raccoon. It scrabbled around, but the stranger managed to get the lid under it. Slowly and gently, the three of them tilted the cooler until it was upright, then pressed the lid in place.

“Will he smother?” asked Aaron.

Kate opened the drain plug. “He should be all right for a while.”

The man loaded the cooler into his truck. The back was littered with tools, cans of marine varnish and a chain saw. Behind the driver’s seat was a gun rack, which held fishing poles and a coffee mug instead of guns. When he turned back, she got a good look at his face. Even with those glasses, he had the kind of rough masculinity that made her go weak in the knees—strong features, a chiseled mouth, a five-o’clock shadow. Oh, Kate, she thought, you’re pathetic.

“Thanks,” he said.

Aaron’s chest inflated in that unconscious way he had of puffing up around another male. Kate ruffled his hair. “We’re glad to help.”

“Do you live around here?” the stranger asked. “Can I bring the cooler to you when I’m done?”

Kate felt a prickle of hesitation. It was never a good idea to tell a stranger where you lived, especially if you lived in a secluded lakeside cottage where no one could hear you scream.

“I’m staying at the Schroeder place,” he said as if reading her thoughts. “It’s on Lake Crescent.”

The Schroeder place. She used to play with Sammy and Sally Schroeder when she was little. Mable Claire Newman had even mentioned this guy, only half teasing: Wait till you see him. And the guy was a rescuer of raccoons, Kate reflected. How bad could he be?

“We’re a quarter of a mile down the road from you,” she told him. “The driveway is marked with a sign that says The Livingstons. I’m Kate Livingston, and this is Aaron.”

“Nice to meet you. I’d shake hands, but I’ve been handling wildlife.”

For some reason, that struck Kate as funny and she giggled. Ridiculously, like a schoolgirl. She stopped herself with an effort. “So, are you one of the Schroeders?” she asked.

“A friend, actually,” he said. “JD Harris.” “JD?” Aaron echoed. “Mr. Harris to you,” Kate told him. “Everyone calls me JD, Aaron included,” the man insisted.

Aaron stood even straighter and squared his shoulders. Kate kept staring at JD Harris. There was something … it was crazy, but she was sure that behind the dark glasses, he was checking her out, and maybe even liking what he saw. And instead of being offended, she felt a flush of mutual interest.

“I’d better get this thing transported,” he said, turning away. “I’ll bring your cooler over later.”

So, thought Kate as she put the Jeep in gear and pulled out onto the road, maybe I read him wrong. Still his image lingered in her mind as she headed west. He intrigued her, even with two days’ growth of beard. Even the sunglasses gave him an unexpected sexiness, reminiscent of that guiltiest of pleasures, Johnny Depp.

Snap out of it, Kate, she told herself. He probably had a wife and kids with him. That would be good, actually. That would be great. Kids for Aaron to play with.

Her son was turned around in the seat, watching the green truck heading back toward town. “You really think that raccoon will live?”

“It was acting pretty lively,” she said.

Around the east end of the lake, the road narrowed. Like Brigadoon, the lake community was locked in the past. Decades ago, President Roosevelt had declared Lake Crescent and its surroundings a national treasure, and designated it a national park. Only those few already in residence were permitted to retain their property. No more tracts could ever be sold or developed, and improvements were restricted. The hand-built cabins and cottages and the occasional dock tucked along the shore seemed frozen in time, and an air of exclusivity served to underscore the specialness of the summer place.

The families of the lake were a diverse group who generally kept to themselves. Mable Claire Newman’s property management company looked after the vacation homes, including the Livingston place.

Kate pulled off the narrow road and turned between two enormous Sitka spruce trees. Aaron jumped out to unhook the chain across the driveway. Bandit leaped after him, ecstatic to finally be here.

Even this small act was the stuff of family ritual. The opening of the driveway chain had the ponderous significance of a ribbon-cutting ceremony. It was always done by the eldest child in the first car to arrive. He would already have the dull, worn key in one hand and a can of WD–40 in the other, because the padlock inevitably rusted over the damp, dark winter. Aaron freed the lock and let the thick iron chain drop across the gravel driveway. He stood aside, holding out his arm in an old-fashioned flourish.

Kate gave a thumbs-up sign and eased ahead. Summer was officially open for business.

With the dog at his heels, Aaron ran ahead down the driveway. It was littered with pinecones and the occasional bough blown down by the winter storms. Kate felt a familiar childlike sense of anticipation as the property came into view. A grove of ferns, some the size of Volkswagens, filled the forest floor bordering the driveway. Speared through by sunlight, it had the look of a magical bower. In fact, Kate’s grandma Charla used to tell her that fairies lived here, and Kate believed her.

She still did, a little, she thought, watching her son and the dog do a little dance of glee.

The driveway widened and lightened as the trees thinned. Ahead, like a jewel upon a pillow of emerald silk, sat the lake house.

She loved the way the lake property revealed itself to her, bit by bit. Its charms were cumulative, from the gardening shed with moss growing on the rooftop to the boathouse that not only housed a boat, but a homemade still left over from Prohibition days. As always, the lake water had a certain mesmerizing clarity, and indeed the drinking water had always been drawn from it.

The lawn had been mowed prior to their arrival. The house looked as though it was just waking up, the window shades at half mast. Over the eyebrow window were the numbers 1921, to commemorate the year the place was built. Godfrey James Livingston, an immigrant who had made a fortune cutting timber, had commissioned the lake house. The family, with somewhat willful naïveté, always referred to the place as a cottage because old Great-Grandfather Godfrey liked to be reminded of the Lake District of his boyhood in England.

Yet the term “cottage” was an irony when applied to this place. Its timber and river-stone facade spanned the spectacular shoreline, curving slightly as if to embrace the singular view of the long lake with the mountains rising straight up from its depths. The house was designed in the Arts and Crafts style, with thick timbers and multipaned dormer windows on the upper story and a broad porch that took full advantage of the setting.

Godfrey’s son—named Walden, with inadvertent prescience—was Kate’s own grandfather. He was a gentle soul who in one generation had allowed the family fortune to dwindle, mainly because he had the distinction of being a devout conservationist in an era when such a thing was all but unheard of. His passion for preserving the virgin forests of the Northwest had been spoken of in whispers, like an aberrant behavior. “He loves trees” had the same hushed scandal as “he loves boys.” Back in the 1930s when Grandfather was growing up, he had fought to protect the forests. Later, during World War II, he’d served as a medic, winning a bronze star at Bastogne. Having gained a hero’s credibility, he later appeared before Congress to urge limits on clear-cutting federal lands. In the 1950s, his enemies denounced him as a Communist.

A decade later, Grandfather came into his own. The flower children of the 1960s embraced him. He and his wife, Charla, an extremely minor Hollywood actress who had once played a bit part in a Marlon Brando movie, protested the destruction of the environment alongside hippies and anarchists. To the acute embarrassment of their grown children, they attended Woodstock and smoked pot. Walden became a folk hero, and he wrote a book about his experiences.

When Kate was a small girl, he was widowed and moved in with her family. She had loved the old man without reservation, spending hours at his side, chattering on in the way of a child, certain her listener hung on her every word.

With a patience that could only be described as saintly, he would listen to her describe the entire plot of Charlotte’s Web or every exhibit in the school science fair. Later, when she was a teenager, it was Grandfather Walden who heard all her Monday-morning quarterbacking about the weekend football games, parties, dates. Her grandfather was the keeper of all her secrets and dreams. It was to him that she first explained her ambition to become a famous international news correspondent. He was the first one she told when she was accepted in the honors program at the University of Washington. And it was to him that she had confessed the event that had changed the course of her future. “I’m pregnant, and Nathan wants me to get rid of the baby.”

“To hell with Nathan.” The old man, wheelchair-bound by then, still managed a lively gesture with his hand. “What do you want?”

Her hands had crept down over her still-flat belly. “I want this baby.”

A gleam of emotion lit his eyes behind the bifocals. “I love you, Katie. I’ll help you in any way I can.”

He’d given her the most critical element of all—his wholehearted, nonjudgmental approval. It meant the world to her. Her parents were supportive, of course. It was the role they felt compelled to play. But every once in a while, Kate sensed their frustration. We raised you for something more than single motherhood.

Only Grandfather knew the truth, that there was no career or calling more thrilling, demanding or rewarding than raising a child.

She loved her grandfather for his great heart and open mind, for his passion and honesty. She loved him for accepting her exactly as she was, flaws and all. Over the years, he gave her plenty of advice. The bit that stuck in her mind consisted of two simple words: Don’t settle.

She wished she’d done a better job following that advice, but she hadn’t, in her career, anyway. She had settled for a popular but uninfluential newspaper that required little from her, only a clever turn of phrase, a canny eye for fashion and the ability to produce eighteen hundred publishable words on a regular basis.

This was it, then, she decided, parking near the back door. This summer was her chance to find something she could be passionate about. She would do it for her own sake, in honor of her grandfather.

Grabbing the nearest grocery sack, she got out of the Jeep and unlocked the back door. At least, she thought she unlocked it. As she turned the key, she didn’t feel the bolt slide.

That’s odd, she thought, opening the door and stepping inside. The cleaners must have forgotten to lock up after themselves. They’d left the radio on, too, and an old Drifters tune was floating from the speakers. She would have to mention it to Mable Claire Newman. Crime wasn’t a problem around here, but that was no excuse for carelessness.

Other than leaving the door unlocked, the cleaners had done an excellent job. The pine-plank floors gleamed, and all the wooden paneling and fixtures glowed with a deep, oiled sheen. The shutters had been opened to dazzling sunlight striking the water.

Kate inhaled the scent of lemon oil and Windex and went to the front window. Everyone who came here rediscovered the old place in his or her own way. Kate always started with the inside of the house, checking to see that the cupboards and drawers were in order, that the clocks were set, the range and oven working, the bed linens aired, the hot water heater turned on. Only after that would she venture outside to touch each plank of the dock, to admire the lawn, and to feel the water, shivering with delight at its glacial temperature.

Aaron headed straight outside, the dog at his heels. He ran along the boundaries of the property, from the blackberry bramble on one end to the growth of cattails on the other. Bandit raced behind him in hot pursuit.

When they pounded out to the end of the dock, Kate bit her tongue to keep from calling out a warning. It would only annoy Aaron. Besides, she didn’t need to caution him to stay out of the water. He would do that on his own, because the fact was, Aaron refused to learn to swim.

She didn’t know why. He’d never had an accident either boating or swimming. He didn’t mind a boat ride or even wading in the shallows. But he would not go in over his head no matter what.

Kate felt badly for him. As he got older, he suffered the stigma of his phobia. Whenever one of the boys at school celebrated a birthday at the community pool, Aaron always begged off with a stomachache. When invited to try out for the swim team, he managed to lose the forms sent home from school. Last summer, he spent hours sitting on the end of the dock while his cousins—even Isaac and Muriel, who were younger than him—flung themselves off the dock and played endless games of water tag and keep-away with the faded yellow water polo ball. Aaron had watched with wistfulness, but the yearning to join them was never enough to motivate him to give swimming a try. She could tell he wanted to in the worst way. He just couldn’t make himself do it. He had to be content standing on the dock or paddling around in the kayak.

Don’t settle, she wanted to tell him. If she did nothing else this summer, she would help Aaron learn to swim. She suspected, with a mother’s gut-deep instinct, that learning to overcome fear would open him up to a world of possibility. She wanted him to know he shouldn’t make do with less than his dreams.

There. The thought had pushed its way to the surface. Aaron had “problems.” According to his teachers, the school counselor and his pediatrician, he showed signs of inadequate anger management and impulse control. A battery of tests from a diagnostician had not revealed any sort of attention or learning disorders. This had not surprised Kate. She knew what Aaron wanted—a man. A father figure. It was no secret. He told her so all the time, never knowing that each time he mentioned the subject, it was a soft blow to her heart. “You have your uncle Phil,” she always told him. Now that Phil had moved away, Aaron’s behavior in school had worsened. She’d missed one too many deadlines, attending one too many parent-teacher conferences, and Sylvia had shown her the door.

Her throat felt full and tight with unshed tears. Really, she thought, she ought to feel grateful that her son was healthy, that he loved his family and most of the time was a great kid. But those other times … she didn’t always know how to deal with him.

Maybe that was why parents were supposed to come in pairs. When one reached her limit, the other could pick up and carry on.

Or so she thought. She didn’t know for certain because she’d never had a partner in parenting Aaron. She’d had a partner in making him, of course, but Nathan had disappeared faster than the Little Red Hen’s friends in the old bedtime story.

Kate went outside and grabbed another sack of groceries. “How about a hand here?” she called to Aaron.

He turned to her and applauded.

“Very funny,” she said. “I’m letting your Popsicles melt.”

He sped across the lawn, his face flushed. Already he smelled like new leaves and fresh air. “All right already,” he said.

Kate set the sack on the scrubbed pine counter. In the sink was a tumbler half-full of water. She dumped it into the drain. The cleaners had probably left it. She put things into the freezer, then opened the fridge and found a covered disposable container with a plastic fork.

“What the.?” Kate murmured. She removed the container and put it straight in the trash. Lord knew how long it had been there.

“What’s that?” Aaron asked.

“Nothing. The cleaners left a few things behind. I’ll have to speak to Mrs. Newman about it.” She finished putting away the perishables and let Aaron go outside again to toss a stick for Bandit.

Then she grabbed two suitcases, heading upstairs. Since it was just her and Aaron this summer, she decided to take the master bedroom. It faced the lake with a central dormer window projecting outward like the prow of a ship. She’d never occupied this room before. She’d never been the senior adult at the lake. This room was for couples. Her grandparents. Then her parents, then Phil and Barbara. Well, she’d have it all to herself, all summer long, she thought with a touch of defiance.

Juggling the suitcases, she pushed open the door. Another thing the maids had forgotten—to open the drapes in here. The room was dim and close, haunted by gloom.

With a frown of exasperation, Kate set down the luggage. Her eyes hadn’t yet adjusted to the dimness. When she straightened up, she saw a shadow stir.

The shadow resolved itself into human form and surged toward her.

A single thought filled Kate’s mind: Aaron.

With that, she bolted down the stairs.

Four

JD felt the woman’s eyes on him. His pulse sped up as he sensed her gaze lingering a few seconds too long.

“Is that all the information you need from me?” he asked, pushing the form across the counter to her.

“That’ll do.” She offered a smile he couldn’t quite figure out. These days he was suspicious of every look, every smile. “Thanks, Mr …” She glanced down at the form. “Harris.”

She was young, he observed. Pretty in a fresh-faced, college-girl way, probably volunteering at the wildlife rehab station for the summer. Darla T.—Volunteer, read the tag on her pocket.

He hoped like hell she wouldn’t volunteer any information about him to her friends. Even out here, in the farthest corner of the country, he was paranoid. Sam had assured him that in Port Angeles he could escape all the hoopla that had disrupted his life since the incident last Christmas, particularly if he changed his appearance and kept a low profile.

After being accosted in every possible way—and in ways he hadn’t even imagined—he was wary. When a tabloid photographer had popped out of his apartment complex Dumpster to get a shot of him in his pajama bottoms taking out the garbage, JD knew his life would never be the same. The notion was underscored by a woman so obsessed with him that she injured herself just to get him to rescue her. The day he’d received an important classified delivery containing a toy company’s prototype of the Jordan Donovan Harris Action Figure, garbed in battle-dress uniform and hefting a Special Forces weapon the real Harris had never even seen before, was the day he’d filed for a discharge. Then, on a rainy night in April, a call came in, a reporter asking him about his mother.

JD had ripped the phone from the wall that night. It was bad enough they hounded him. When they turned like a pack of wolves on his mother, something in JD had snapped, too.

Enough.

If he had to put up with any more attention, he’d end up as loony as the guy whose bomb he’d stopped.

JD needed to disappear for a while, let the furor die down. Once he fell off the public radar, he could slip quietly back into private life. Sam had offered his family’s summer cabin and wanted nothing in return. That was just the kind of friend he was.

So far, JD’s retreat seemed to be working. His mother, Janet, was getting the help she needed, and here in this remote spot, three thousand miles from D.C., no one seemed to recognize him. Though confident that he bore no resemblance to the clean-cut military man he’d once been, he had his moments of doubt. Like now, when a pretty girl batted her eyes at him. He no longer trusted a stranger’s smile. Maybe there used to be a time when a girl smiled because she liked him, but that seemed like another person’s life. Now every friendly greeting, every kind gesture or invitation was suspect. People no longer cared who he was, only that he’d stopped a suicide bomber in the presence of the President.

The media and security cameras at the hospital had recorded the entire incident. The drama lasted only minutes, but when it was over, so was life as he knew it. TV stations around the world ran and reran the footage, and it could still be seen in streaming video on the Internet. The press had instantly dubbed him “America’s Hero,” and to his mortification, it stuck.

“It’s you I should be thanking,” he said to Darla, picking up the ice chest. “Good to know there’s a place like this in the area.”

She nodded. “We can’t save them all, but we do our best.” She handed him a printed flyer. “We can always use volunteers, ages eight to eighty. Keep us in mind.”

Carrying the now-empty cooler, he went out to his truck. Sam’s truck. Everything had been borrowed from Sam—his truck, his vacation cabin, his privacy. JD glanced again at the volunteer form and stuffed it in his back pocket. Then he headed for the car wash. Best to clean out the woman’s cooler before giving it back.

As he was pulling out of the parking lot, he heard the quick yip of a siren and looked down the road. An ambulance rig glided past at a purposeful speed, heading for the county hospital. The cars that had pulled out of its way slipped back into the stream of traffic again, ordinary people, going about their ordinary lives. Anonymity was such a simple thing, taken for granted until it was taken away.

JD felt a thrum of familiarity as the vehicle passed. That was what he was supposed to be doing. Helping. Not hiding out like a fugitive, rescuing raccoons.

Of course, once his face was splashed on the front page of newspapers and magazines across the globe, he wasn’t much good on emergency calls. Sometimes he’d attract more rubberneckers and media than a five-car pileup, just for being on the scene.