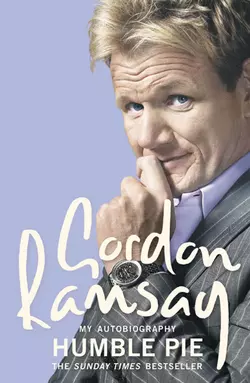

Humble Pie

Gordon Ramsay

Everyone thinks they know the real Gordon Ramsay: rude, loud, pathologically driven, stubborn as hell. But this is his real story…This is Gordon Ramsay’s autobiography – the first time he has told the full story of how he became the world’s most famous and infamous chef: his difficult childhood, his brother’s heroin addiction and his failed first career as a footballer: all of these things have made him the celebrated culinary talent and media powerhouse that he is today. Gordon talks frankly about:• his tough childhood: his father’s alcoholism and violence and the effects on his relationships with his mother and siblings• his first career as a footballer: how the whole family moved to Scotland when he was signed by Glasgow Rangers at the age of fifteen, and how he coped when his career was over due to injury just three years later• his brother’s heroin addiction.• Gordon’s early career: learning his trade in Paris and London; how his career developed from there: his time in Paris under Albert Roux and his seven Michelin-starred restaurants.• kitchen life: Gordon spills the beans about life behind the kitchen door, and how a restaurant kitchen is run in Anthony Bourdain-style.• and how he copes with the impact of fame on himself and his family: his television career, the rapacious tabloids, and his own drive for success.

Humble Pie

Gordon Ramsay

Copyright (#ulink_dbf8ad3b-925d-5fbe-be5e-7cd74632693f)

Harper

An Imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2006 This edition 2007

Copyright text © Gordon Ramsay 2006, 2007

The Author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9780007229680

Ebook Edition © FEBRUARY 2010 ISBN: 9780007279869

Version: 2015-03-18

To Mum, from cottage pie to Humble Pie – you deserve a medal.

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#u56ac6ce9-12de-5986-865a-20878aee661f)

Title Page (#u3e4c007b-3496-5cb5-9849-fca6663ba39b)

Copyright (#ueb8840ef-c461-5b81-99a4-fcd9809a7b93)

Dedication (#u4be18776-eb1f-5aaf-8726-da54b414eba2)

Foreword (#u5ebbcbcc-41b5-543e-891b-23cbf6730204)

Chapter One: Dad (#u8fdb6ba8-4453-587f-a36d-5909e3ed3552)

Chapter Two: Football (#ub658f90f-910a-58e2-9af1-8f2ca2d4f25a)

Chapter Three: Getting Started (#udc2c4459-5682-545d-a1c1-b372c9bda3b8)

Chapter Four: French Leave (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Five: Oceans Apart (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six: A Room Of My Own (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven: War (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight: The Great Walk-out (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine: The Sweet Smell Of Success (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten: Ronnie (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven: Down Among The Women (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve: Welcome To The Small Screen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen: New York, New York (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen: Family (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen: The Important Things In Life (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Picture Credits (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

FOREWORD (#ulink_5a17936e-3f6c-558f-b99d-e4c6a70eff2a)

IN MY HAND, I’ve got a piece of paper. It’s Mum’s handwriting, and it’s a list – a very long list – of all the places we lived until I left home. I look at this list now, and there are just so many of them. My eye moves down the page, trying to take in her spidery scribble, and I soon lose track. These places mean very little to me: it’s funny how few of them I can remember. In some cases, I guess that’s because we were hardly there for more than five minutes. But in others, it’s probably more a case of trying to forget about them as soon as possible. When you’re unhappy in a place, you want to forget about it as soon as possible. You don’t dwell on the details of a house if you associate it with being afraid, or ashamed, or poor – and as a boy, I was often afraid and ashamed, and always poor.

Life was a series of escapades, of moves that always ended badly. The next place was always going to be a better place – a bit of garden, a shiny new front door – the place where everything would finally come right. But it never did, of course. Our family life was built on a series of pipe dreams – the dreams of my father. And he was a man whose dreams always turned to dust.

I don’t think people grasp the whole me when they see me on television or in the pages of some glossy magazine. I’ve got the wonderful family, the big house, the flash car in the drive. I run several of the world’s best restaurants. I’m running round, cursing and swearing, telling people what to do, my mouth always getting me into trouble. They probably think: that flash bastard. I know I would. But it’s not about being flash. My life, like most people’s, is about keeping the wolf from the door. It’s about hard work. It’s about success. Beyond that, though, something else is at play. Is it fear? Maybe. I’m as driven as any man you’ll ever meet. I can’t ever sit still. Holidays are impossible. I’ve got ants in my pants – I always have had. When I think about myself, I still see a little boy who is desperate to escape, and anxious to please. The fact that I’ve long since escaped, and long since succeeded in pleasing people, has made little or no difference. I just keep going, moving as far away as possible from where I began. Where am I trying to get to? I wonder…Work is who I am, who I want to be. I sometimes think that if I were to stop, I’d cease to exist.

This, then, is the story of that journey – so far. The tough childhood. My false start in football. The years I spent working literally twenty hours a day. My battles with my demons. My brother’s heroin addiction. The death of my father, and of my best friend. I’m just forty, and it seems, even to me, such an amazingly long journey in such a short time.

Will I ever get there? You tell me.

CHAPTER ONE DAD (#ulink_682e990d-e41b-5d25-ae53-570c88cfe7b3)

THE FIRST THING I can remember? The Barras – in Glasgow. It’s a market – the roughest, most extraordinary place, people bustling, full of second-hand shit. Of course, we were used to second-hand shit. In that sense, I had a Barras kind of a childhood. But things needn’t really have been that bad. Mostly, the way our life was depended on whether or not Dad was working – and when I was born, in Thornhill Maternity Hospital in Johnstone, Renfrewshire, he was working. Amazingly enough.

Until I was six months old, we lived in Bridge of Weir, which was a comfortable and rather leafy place in the countryside just outside Glasgow. Dad, who’d swum for Scotland at the age of fifteen – an achievement that went right to his head, if you ask me – was a swimming baths manager there. And after that, we moved to his home town, Port Glasgow – a bit less salubrious, but still okay – where he was to manage another pool. Everything would have been fine had he been able to keep his mouth shut. But he never could. Sure as night followed day, he would soon fall out with someone and get the sack; that was the pattern. And because our home often came with his job, once the job was gone, we were homeless. Time to move. That was the story of our lives. We were hopelessly itinerant.

What kind of people were my parents? Dad was a hard-drinking womaniser, a man to whom it was impossible to say ‘no’. He was competitive, as much with his children as with anyone else, and he was gobby, very gobby – he prided himself on telling the truth, even though he was in no position to lecture other people. Mum was, and still is, softer, more innocent, though tough underneath it all. She’s had to be, over the years. I was named after my father, another Gordon, but I think I look more like her: the fair hair, the squashy face. I have her strength too: the ability to keep going no matter whatever life throws at you.

Mum can’t remember her mother at all: my grandmother died when she was just twenty-six, giving birth to my aunt. As a child, she was moved around a lot, like a misaddressed parcel, until, finally, she wound up in a children’s home. I don’t think her stepmother wanted her around, and her father, a van driver, had turned to drink. But she liked it, despite the fact that she was separated from her father and her siblings – it was safe, clean and ordered. The trouble was that it also made her vulnerable. Hardly surprising that she married my father – the first man she clapped eyes on – when her own family life had been so hard. She just wanted someone to love. Dad was a bad lot, but at least he was her bad lot.

By the age of fifteen, it was time for her to make her own way in the world. First of all, she worked as a children’s nanny. Then, at sixteen, she began training as a nurse. She moved into a nurses’ home – a carbolic soap and waxed floors kind of a place – where the regime was as strict as that of any kitchen. In the outside world, it was the Sixties: espresso bars had reached Glasgow and all the girls were trotting round in short skirts and white lipstick. But not Mum. To go out at all, a ‘late pass’ was needed, and that only gave you until ten o’clock. One Monday night, she got a pass so that she could go highland dancing with a girlfriend of hers. But when they got to the venue, the place was closed. That was when the adrenalin kicked in. Why shouldn’t they take themselves off to the dance hall proper, like any other teenagers? So that was what they did. A man asked Mum to dance, and that was my father, his eye always on the main chance. He played in the band there, and she thought he was a superstar. She was only sixteen, after all. And when it got late, and time was running out and there was a danger of missing the bus, all Mum could think of was the nightmare of having to ask the night sister to take her and her friend back over to their accommodation. Then he and his friend offered to drive them back in his car. Well, she thought that was unbelievably exciting, glamorous even. He was a singer. She’d never met a singer before.

After that, they met up regularly, any time she wasn’t on duty. When she turned seventeen, they married – on 31 January, 1964, in Glasgow Registry Office. It was a mean kind of a wedding. No guests, just two witnesses, no white dress for her, and nothing doing afterwards, not even a drink. His parents were very strict. His father, who worked as a butcher for Dewhursts, was a church elder. Kissing, cuddling, any kind of affection was strictly forbidden. My Mum puts a lot of my father’s problems in life down to this austere behaviour. She has a vivid memory of a day about two weeks after she was married. Her new parents-in-law had a room they saved for best, all antimacassars and ornaments. Her father-in-law took Dad aside into that room, and her mother-in-law took Mum into another room, and then she asked Mum if she was expecting a baby.

‘No, I’m not,’ said Mum, a bit put out.

‘Then why did you go and get married?’ asked her new mother-in-law.

I’ve often asked Mum this question myself. It’s a difficult one. I’m glad I’m here, obviously. But my father was such a bastard, and he treated her so badly, that it’s hard, sometimes, not to wonder why she stayed with him. Her answer is always the same. ‘He wanted to get married, and I thought “Oh, it would be nice to have my own home and my own children”.’ But she knew he was trouble, right from the start.

Ten months later, my sister Diane came along, and Dad got the job at a children’s home in Bridge of Weir. They were given a bungalow on the premises and my poor mother really did think that all her dreams had come true. There was a swimming pool in the grounds, where he was an instructor and manager. According to Mum, it was lovely – idyllic, even. Then it started – the drinking and the temper. She found out that even as they had been getting married, Dad had been on probation for drinking and fighting – though he told her that it wasn’t his fault and, like an idiot, she believed him. She was madly in love, you see. The violence against her started soon after that. He would slap her about and, not having had any other experience with men, she assumed that this was what every woman had to put up with. When her father told her that Dad was bad, she refused to believe him. She’d pay a visit home and, when she took off her coat, there were bruises on her arms, and maybe a cut to her eye or her lip.

‘Oh, I just banged into a cupboard, Dad,’ she’d say. He’d accuse her of telling lies, of covering up. But she was deaf to it all, of course.

Next was the job in Port Glasgow. The prodigal son returns. Dad had all sorts of big ideas about that – his swimming career meant that everyone in the town knew him. They got a nice council house, and I think Mum felt quite settled. But Dad was all over the place – ‘fed up’ he used to call it, a pathetic euphemism. The womanising got steadily worse – he’d go out at night, and not come back until the morning. Then he’d get changed and go straight off to the pool to work. By now, I was around, and Mum was pregnant with my brother, Ronnie. One morning, Dad came home and announced that his car had been stolen. He made a big show of phoning the police to report it. Of course, it was complete bollocks. What had actually happened was that he’d been with a woman, had a few drinks, and knocked down an old man in what amounted to a hit-and-run. Despite his best efforts, it wasn’t long before the police found out and it was all over the papers. There was nothing else for it. Port Glasgow wasn’t a very big place, and it was certainly too small for us now. We had to leave, literally overnight. Diane was toddling, I was in a pushchair, and Mum was pregnant. But did he care? No, he didn’t. It was straight on the train to Birmingham, and who knows why. It could just as easily have been Newcastle, or Liverpool. He may as well have stuck a pin in a map, at random. We knew no one. We spent the night at New Street Station, waiting for the sun to come up so that Dad could walk the streets, looking for somewhere to live. What a desperate sight we must have made; you can all too easily imagine people walking past, looking down at the pavement in their embarrassment.

We found a room in a shared house. Amazingly, Dad only got probation and a fine for the hit-and-run, and he soon picked up a job as a welder. The room was horrible, or so Mum tells me, but we just had to make the best of it. We shared a kitchen – in fact, a cooker in the hall – and a bathroom with another family. Meanwhile, Dad joined an Irish band, and all the usual kinds of women were soon hanging onto his every word. If he went out on a Friday night, you were lucky if you saw him again before Sunday. Needless to say, the welding soon went by the way. He wanted to spend more time with the band; he was convinced, despite all evidence to the contrary, that he was going to be a rock-and-roll star. Even at such a young age, these fantasies of his would make me sick. We’d spend time with him going from market to market looking for music equipment. The money he used to spend was extraordinary, and hard to take. There we’d be, looking at these Fender Stratocasters and Marshall amplifiers – the fucking dog’s bollocks of the music world – and we’d be dressed in rags. All our clothes were from jumble sales, our elbows and knees patched over and over again. How did he fund his shopping habit? Loan sharks, mostly. His debts still come back to haunt me now – our names are the same, and I’ll occasionally get investigated by companies trying to recoup the cash he owes them.

The older I got, the harder this kind of treatment got to bear. I remember when Choppers and Grifters were the big things. Well, of course, we never, ever had a new bike. On birthdays, I used to get a £3.99 Airfix model kit. However much I enjoyed putting those things together, you could tell they’d come from somewhere like the Ragmarket, which was Birmingham’s version of the Barras. There’d be half of it missing, or the cardboard box it came in would be so wet and soggy that you wouldn’t have wiped your arse with it. Christmas was terrible. When we were older, Mum always used to work in a nursing home, doing as much double-time as she could, sometimes not even coming home on Christmas Day. I used to dread Christmas.

And then the bailiffs would show up. We’d be evicted, Dad’s van would be loaded up, and that would be it. Off to the nearest refuge, or round to the social services pleading homelessness. He was always telling them that he was ill, trying to get sickness benefit. In reality, though, he’d be out gigging three or four times a week.

As a teenager, I used to be ashamed of some of the places we lived. We always seemed to end up in the worst of places: the ones that were riddled with damp, with nails exposed everywhere, the ones that had been left like pigsties by other families. I never used to let on to girlfriends – I’d make them drop me off round the corner. It wasn’t so much that I was embarrassed about living on an estate, or in a tenement block. It was more the state of our home itself. Every time he got violent, any ornament, any present we’d bought for Mum, a vase or a picture frame – anything nice – would be smashed or thrown through a window or destroyed, simply because it belonged to her.

I think we built up a lot of insecurity as children. I used to find it so intimidating, walking into yet another new school. Academically, we were never in one place long enough to develop any kind of attention span – and in any case, Dad was hardly the kind of man to insist on you doing your homework. Only poofs did homework. The same way only poofs went into catering. No, he was much more interested in trying to turn us into a country version of the Osmonds. Diane, Ronnie and Yvonne, my younger sister, all sing and play musical instruments. They didn’t really have any choice about that, Dad was obsessed. But something in me wasn’t having it, and I never went along with his plan. That’s not to say I wasn’t just as scared of him as they were. My tactic was to keep my head down and my nose clean. I never drank or smoked, and when I was asked to lug his bloody gear about the place, I just got on with the job. It’s ironic, really, that people think of me as so forceful and combative, a real aggressive bastard, because that’s the precise opposite of how I was as a kid. Until I was big enough to take him on in a fight, I wouldn’t have said ‘boo’ to a goose.

His favourite punishment was the belt. You’d get whacked on the back of your legs with it for something as innocent as going into the fridge and drinking his Coke. I say ‘whacked’. The truth is, I would get completely fucked over for that sort of thing. But what would really set him off were lies. I’d lie about things because I was too scared to tell him the truth, ‘Yeah, Dad, it was me who went in the fridge and took your Coke’ – and then he’d go absolutely fucking ballistic. Of course, what I didn’t realise at the time was that it wasn’t so much the Coke he was bothered about as the fact that he wouldn’t have a mixer for his precious Bacardi. He was the kind of drinker who couldn’t open a bottle without finishing it. You’d watch the stuff disappear, and your heart would sink.

Yvonne was born in Birmingham. One night, when Mum was six months pregnant, a neighbour had to call the police as Dad was dishing out some domestic violence on Mum. He was taken away. Mum was taken to hospital and ended up signing consent forms for the three of us to be taken into a children’s home for ten days. She visited every day. Then Dad was released and he came back home.

Next stop was Daventry, where we had quite a nice council house. It even had a garden. This time, Dad got a job as a rep, but he was still doing his band work and, thanks to the buying of yet more equipment, the debts were building. One day, he told Mum to pack – only the belongings she could fit in his precious van – and we were off again, to Margate where, for a time, we lived in a caravan. He never explained, or tried to justify his behaviour. We did as we were told. That was easily the worst place we ever lived, horrendous. I shudder to think of it. We didn’t even have enough money for the gas bottle to keep the place warm. The rain just came pelting down, while inside we shivered, and wondered how long we were going to be there. We were saved by the council, who put us back into a bed-and-breakfast.

Then it was back up to Scotland again, followed by another stint in Birmingham, and then on to Stratford-upon-Avon. Dad had somehow managed to get another job at a swimming pool. But he couldn’t settle. Off he’d go: off to France, to America. He never sent money home; it was up to Mum to earn our keep. When he came back from his stint abroad, we moved to Banbury, Oxfordshire, where he was going to run a newsagent’s shop. Everything was great for a while. We lived above the shop, and the guy who owned it was lovely. This was Dad’s big chance to get it right, if you ask me. But no, he had to screw it all up. One day, while I was getting something out of the fridge, I noticed that the lining of the door was loose. Unnaturally loose. And something was hidden in there – a wad of cash, it must have been at least £300. I remember feeling very sick, I nearly threw up then and there. Dad was on the fiddle. Not long after that, of course, the owner found out, and we were out on our ear again.

So then it was back up to Scotland – Glasgow. Dad had heard that the country and western scene was better up there. But I was a teenager by now, and I decided not to go. The council gave Diane and me a flat and so we stayed put. I was doing a catering course at college, sponsored by the local Round Table who’d even helped me to buy my first set of knives – but, in any case, I don’t think Dad wanted either of us around. He just couldn’t control Diane the way he’d controlled Mum, and that left him feeling frustrated because in the old days she’d sung with him, been dragged around all the seedy clubs. He had thought she was his, and when it turned out that she wasn’t, that she had a mind of her own, he just couldn’t take it. Later, when Diane got married, she didn’t want him anywhere near her. It was me who gave her away.

As for me, I was public enemy number one. Up in Glasgow, Mum would have to sneak out of the flat if she wanted to ring me. I certainly wasn’t allowed to ring her. I had finally crossed a line when I was fifteen. I was going out with a girl called Stephanie, and one night I came back late – too late, in his eyes.

‘Get your stuff out of my house, and go and live with her,’ he said.

‘I’m sixteen next week,’ I said. ‘I can go where I like.’

I’d already been given some kind of big radio for the upcoming birthday, and he threw it at me, from the top of stairs. ‘I can’t believe you’ve done that,’ I said. ‘You know damn well that Mum bought it for me.’ I knew she’d got it on hire purchase, which was costing her £8 a month, and I couldn’t bear it. ‘I’d rather you did that to me than to something that hasn’t even been paid for,’ I said.

At that, he came storming down the stairs. At first, I stood my ground. Then I saw the look in his eyes. That was why I bolted, and I’m not ashamed to admit it. I don’t think that I would be here today if I’d stopped and tried to confront him. For the first time, I felt that he really might kill me. I remember him teaching me how to swim by holding my head under the water for minutes on end – I’d end up struggling and gasping for air – so I’d always known he was a sadistic bastard. But I saw something different in his eyes that day – a glint that chilled me. There was nothing there. It was a kind of madness.

Of course, once Diane and I were out of the way, he turned his attention to whoever else was available. Ronnie was his pal, mostly, so now it was Yvonne’s turn to take the sort of treatment that I had suffered previously.

By that time, I was already trying to make headway as a cook, on the first rung on the ladder, busting my nuts in a kitchen, and it was unimaginably painful – hearing this stuff from Mum, her voice down the telephone. Yvonne had grown up more quickly than the rest of us – she had a baby in her teens, and she was a real ‘ducker and diver’, but he just pushed her too far, there was too much pressure, and she was going under.

Meanwhile, Mum was still getting knocked about. She was working in my Uncle Ronnie’s shop in Port Glasgow – he was a Newsagent – and she’d come in early in the morning, sometimes not having been to bed at all, with bruised lips and black eyes, and my uncle would say: ‘Oh, Helen, you can’t serve the customers looking like that,’ and she’d say: ‘Well, it was your brother that did this to me.’ But, of course, no one intervened. It was a different time then. Domestic violence was still considered a private matter, something for couples to sort out between themselves.

‘That’s bloody terrible,’ he’d say. ‘You should hit him back.’

Fat lot of good that advice was. Things got so bad that Mum finally worked up the courage to leave him, and the council gave her, Ronnie and Yvonne a flat. But Dad was soon back, pleading forgiveness, promising that everything would be different. And so it would be, for a few weeks. Then he’d start sliding again, back to his old ways, all this anger always pouring out of him. Oh, he was good at crying crocodile tears, but his heart was an empty space where all the normal feelings a man has for his family should have been.

Next, they embarked on some kind of house swap, and the four of them ended up in Bridgwater in Somerset. Same old story…No sooner had they settled in than Dad was off again – this time on a cruise ship. He took Diane with him, to sing, which put Mum’s mind at rest a little because even after everything he’d done to her, she was still worrying that he would run off with someone else, and she had this idea that a cruise would be full of beautiful women. Diane was engaged by this time, and her fiance and Mum saved up to go out and meet the ship in Venice. Mum worked so hard – she had three part-time jobs on the go all at the same time. But when they got there, no sooner had they boarded the ship than Dad had some big, drunken argument with the man who was in charge of the entertainment. This ended with Dad, in a fit of pique, sabotaging all the ship’s musical equipment, at which the captain told him he had to leave. They all came back to London by bus – a fine end to Mum’s dream trip. Did he feel bad about this? Did he feel guilty? Not at all. He had got his revenge, and that was all that mattered.

It was in Bridgwater that he committed the final transgression, and departed our lives – almost for good, if not quite. It’s a time I cannot think about without feeling the blood pulsing in my temples, though I was not even there when it happened. I’m not sure what I’d have done if I had been.

Dad had had a couple of drinks, but he certainly knew what he was doing; this attack was calculated, clever even, not some dumb, drunken rage. He came home from work one night, and he just started. There was no ‘trigger’. Mum was in bed, with a mug of hot milk. He poured it all over her, even as she lay there, leaving bad scalding to her chest. Then he dragged her downstairs, and the beating started. By the time the ambulance arrived, she looked like she’d done five rounds with a heavyweight boxer. Her eyes were completely closed, her face swollen and pulped. First, she was taken to a hospital, then to a refuge. Dad, of course, didn’t stay to face the music. He disappeared at the first sound of a police siren.

A few days later, I finally tracked him down. He was with a woman called Anne, whom he would later marry.

‘Mum’s been in hospital for three days,’ I said. ‘And she’s still wearing sunglasses.’

‘Well, she asked for it,’ he said.

That was when the social services and all the other authorities got fully involved, and a restraining order was taken out on him. He wasn’t allowed anywhere near the house.

But when Mum went home, she found everything that she had built up and saved for smashed to smithereens. He hadn’t left as much as a light bulb intact.

Worst of all, Dad had left a note on the mantelpiece. It said: ‘One night, when you are least expecting it, I’ll come back and finish you off’. Even after the restraining order came into effect, there were some evenings when Mum would be sitting in alone and the phone would ring and she’d hear his voice telling her that he was on his way. Many nights, you would have seen a patrol car parked outside the house, just in case. How she slept, I’ll never know.

Journalists have often asked me whether I loved Dad, whether I had any love at all in my heart for him. The truth is that any time I tried to get close, I’d just come up against this competitive streak in him. Later, my feelings for him hardened into hatred. Everything he did, I was determined to do the opposite. I never wanted to follow in his footsteps, and that’s why I never picked up a fucking guitar, and that’s why I never sat at the fucking piano. Were there any good times? Not really. I suppose the only thing that I really admired about him was the fact that he was a fisherman. He was a great fisherman, there’s no two ways about it. But even that got tainted by all the other stuff.

Ronnie was good at keeping Dad’s secrets, but I made the mistake of telling Mum exactly what he used to get up to. After that, I was never taken fishing again. We used to go to this campsite on the River Tay in Perth – salmon fishing. Ronnie and I would be sitting on the riverbank at nine o’clock at night on our own, fishing, while Dad and his mate Thomas would be out drinking. He’d give us a fiver between us, and tell us to keep ourselves amused. I remember one time when the weather was bad, it was raining heavily, and we’d booked into this little bed-and-breakfast. That night, Ronnie and I ended up sleeping in the bathroom because Dad had brought some woman back. I can’t have been older than twelve at the time.

After a while, Dad went off to Spain, and I didn’t see him for many years. I was too busy trying to make a success of my life, but even if I hadn’t been working every hour God sent, I had no real wish to see him. Dad, though, had a way of turning up when you least expected him, like a bad penny. It was towards the end of 1997. I was busy trying to win my second Michelin star by this point – which should give you some idea of how much time had passed – when I got a call from Ronnie telling me that Dad was in Margate. He’d had an argument with Anne, and Anne’s sons, and he’d upped and left.

I called him on the number Ronnie had given me – I don’t know why. He sounded very low.

‘I’m here to see my doctor,’ he said.

‘Come on,’ I said. ‘Why are you really here?’

‘No, I’m back just to have a check-up.’ There was a pause. Then he said: ‘Can I see you?’

‘Yeah, yeah, I’ll come down.’

It had been a difficult year. My wife, Tana, and I were expecting our first baby. And I was involved in all sorts of legal wrangles over my restaurant, Aubergine. Still, I drove down there. There was something in me that couldn’t refuse his request. We were to meet on the pier where we used to go fishing back when we had lived in the town ourselves, so I knew exactly where he’d be. I got out of my car and I saw this old, frail, white-haired man with bruises on his face, and marks on his knuckles. I felt stunned. This was the man I’d been scared of for so long, brought so low, so pathetic and feeble.

We went and had breakfast in a little cafe. The waiter came over and asked us what we would like and, straight away, Dad started into me, telling me that when I was at home I always used to steal his bread. The words came out of nowhere. Another unwarranted attack.

‘What’s happened to you?’ I said.

‘Oh, Anne and I separated, and I had an argument with one of her sons and he tried to have a go at me.’

‘Look at the state of you. Where are you living?’

He pointed at the car park, and there, as ever, was his Ford Transit van. We went out and I opened it up and inside there were all his possessions: his music equipment, his clothes, and these silly lamps – paraffin lamps – and an inflatable camp bed in the back with these awful net curtains in the windows.

We finished our breakfast, and we went for a walk on the pier, and it was so sad. So I went to the bank, and I got out £1,000 and I gave it to him for the deposit on a flat. I thought that at least I could do the right thing by him. And that’s what he did, he got a little one-bedroomed basement flat. A week later, I went back to see him again. He told me that he was going to be on his own for Christmas. I was in two minds as to what to do. Then I decided: this is not the right time to introduce him to Tana. I felt sorry for him, real pity, but nothing more. And anything I did feel had nothing to do with him being my father; I just felt sorry that a man had to be on his own at that time of year. It seemed so desolate, so bleak.

On Christmas Eve, he telephoned. Anne was coming over to spend the week with him, and they were going to try and resolve their differences. That was the last time I ever spoke to him. Looking back, I wonder if he knew that his time was running out. He’d gone back to Margate because that was where he’d gone on holiday with his parents, as a boy. Perhaps it had happy memories for him. It certainly didn’t for me. Driving back to London after that last visit, I cried my eyes out. What a waste of a life.

After hearing that he and Anne had made up, I booked him a table at Aubergine for the 21st of January, 1998. That was going to be a big, big day for me. First of all, that was Michelin Guide day. The new edition. Second, I was going to introduce this guy, my father, to all my staff. I’d spoken of him so little, most of them didn’t even know I had a father. The truth is that he embarrassed me. When I was eighteen, a girlfriend gave me a gold chain, a massive gold chain – bling before bling was invented – and Dad was envious of it, so incredibly envious. One day he asked me if he could wear it. So I gave it to him. That was the kind of power he had because at the time I loved it half to death. Later, I remember shuddering, seeing him look like some East End spiv, dripping in gold. There was my chain, and sovereign rings, and chunky gold bracelets, all topped off with a white leather jacket. I had never known how to describe this man to anyone, let alone my staff. I’d reinvented myself, I suppose. I’m not ashamed of that. I’ve never tried to pretend anything else. All I knew was that I didn’t want to be like him, and any time I came even close to doing so, I would put the fear of God into myself. My father was in some box that, metaphorically speaking, I’d hidden in a dusty corner of the attic years ago.

And then there was my fear of being used. A while before he came back to England, during a busy service at Aubergine, someone came to me saying I had a phone call from my brother-in-law. At the time, I didn’t have a brother-in-law.

‘Dave, here,’ said the voice.

‘Look, Dave,’ I said. ‘I’m fucking busy right now. I haven’t got time for pranks. You can call me back at fucking midnight.’

But he persisted. He refused to get off the line.

‘Look, Dave,’ I said, again. ‘I don’t know who the fuck you are but this is not the right fucking time. I’m not fucking happy.’

‘Well, I don’t care where you are or what you’re cooking,’ said the voice. ‘My Mum is married to your dad.’

Then it clicked. That, you see, was how little I thought of Dad, and how little I knew about his new life. The voice said: ‘I read that you do consultancy work for Singapore Airlines and my watch is from Singapore, and I can’t get a battery in this country. Is there any chance you could get one for me next time you are out there?’

Perhaps you can imagine how I felt.

‘Are you taking the fucking piss?’ I said.

I put down the phone. Some guy I’d never even met ringing me in the middle of service to ask me to get him a new battery for his watch. I simply could not believe it.

It was New Year’s Eve when we heard that my father died. The family were all in London, staying with me and Tana. It must have been about 3.30 a.m. We’d been in bed for an hour. Then the phone rang. I woke up and answered it and all I could hear was screaming. At first, I thought someone was trying to wish me a Happy New Year, but this person was in hysterics. She kept going on about some drug, how it hadn’t worked. She kept going on about someone called Ricky Scott. I put down the phone. Then, as it began to sink in, I called this person back. It was Anne, and ‘Ricky Scott’ was Dad. Apparently, he’d changed his name. Scott was his mother’s maiden name.

It was his alcoholism that had killed him. Of course, I drove straight down there, to the hospital. I felt fucking robotic. I was just going through the motions. That was the first time I had ever laid eyes on Anne. ‘Oh my God,’ she gasped. ‘You’re so like your father.’ All I remember is lots of people smoking, and drinking tea. I was asked if I wanted to see him – Dad. I said no.

‘I can’t believe you’re not going to see him,’ she said.

‘Well, that’s my choice,’ I said. I knew I wouldn’t be very good at seeing a dead person. It just wasn’t something I could put myself through. Years later, a close friend of mine died. I was asked to go and identify the body. But I couldn’t. I had to send someone else. I wasn’t any stronger then.

For all that I hated him, burying Dad was one of the worst days of my life. The funeral was horrible. She organised it, Anne, in a Margate crematorium so characterless it might as well have been a branch of Tesco. Oh, it was bad, really bad. We walked in, and his songs were playing, him singing. To me, that was the worst thing. And then, all these strangers…We knew no one.

Mum didn’t go, but my sisters did. And Ronnie, though not without a fight. By this time, Ronnie was a desperate heroin addict, and he was refusing to go. I was at my wits’ end. Finally, about an hour before the funeral, I gave him money so that he could buy what he needed to get him through. I thought it was better for him to be there and off his face, than not there at all. How low can you go? Very low indeed, if you’re desperate.

We carried Dad in, in his wooden box, and I could have cried. I started listening to the service, and they were calling him Ricky. That wasn’t even his name. His name’s Gordon, I thought. Why the fuck are they calling him Ricky? Then Anne turned round, and said: ‘I think your father would have wanted you to say a few words.’ So I did.

‘On behalf of the Ramsay family, I just want to say that we don’t know this “Ricky”. Dad’s name is Gordon.’ I got so upset I couldn’t even finish my sentence. I burst into tears. It took me several attempts to get the words out. Afterwards, we tried to be polite. We went and spent the requisite fifteen minutes at the knees-up that she’d organised. But I couldn’t have taken any more than that. Ronnie was out of it in any case. We could have been at a family christening for all he knew.

After that, I drove back to London and I went straight back to the kitchen. I was there, on the pass, working as hard as ever, trying not to think – or at least, to think only about the next order. I don’t think I’ve ever needed my kitchen so much in all my life.

What did my father leave me? A watch, actually. Everything else he ‘owned’ was on hire purchase anyway. He never tasted my cooking in the end, though even if he had, I doubt he would have been impressed. ‘Cooking is for poofs,’ he used to say. ‘Only poofs cook.’

But there is something else, too. Someone, I should say. Dad had another child, a girl, before he met Mum. Her parents adopted the baby. Apparently, Dad had planned on marrying her, but her parents had other ideas. One night, they went to see him sing, and then they followed him home and told him to stay away from their daughter. They threatened to beat him up. Perhaps his performance that evening had been even worse than usual. So that was that. He walked away, and went after Mum instead. My father’s parents knew all about this child, but they kept it from Mum, though she found out, of course – and several times, when she was expecting Diane, she even saw his child.

CHAPTER TWO FOOTBALL (#ulink_921262fe-c1c5-59d4-b025-0ee74d6b5800)

I MUST HAVE been about eight when I realised I was good at football. It was football, not cooking, that was my first real passion. I was a left-footed player – still am – and I was always in the back garden, or out in the close, kicking a ball against the wall. I used to long for Saturday mornings. The night before, I’d polish my boots until I got the most amazing shine on them. I remember my first pair of football boots. They were second-hand, bought from the Barras by Mum, and they didn’t fit properly; I had to wear two or three pairs of socks with them at first. But that didn’t matter to me, because owning them was more exciting than anything.

Football was one way I thought I could impress Dad. Nothing else worked. He never came into school, to see how we were doing, and he never thought our swimming was as good as his. But he and my Uncle Ronald were huge Rangers fans, and I could see that this might be a way to reach him. Uncle Ronald had a season ticket, and any time we went up to Glasgow, we would go off to Ibrox to see a game. I must have been about seven when I went to my first match. I remember being up on Ronald’s shoulders, and the incredible roar of the crowd. It was quite frightening. They still had the terraces in those days, and when the crowd celebrated, everyone surged forward: this great, heaving mass. I was always worried things might kick off, especially during derby matches. There was so much aggression between Rangers and Celtic and I could never understand why they had to be that nasty. My uncle told me that the men all worked together in the shipyard Monday to Friday but when it came to the weekend, they hated one another’s guts. I was very struck by that as a boy.

Back in Stratford, I was chosen to play under-14 football when I was just eleven, and, later, I used to be excused from rugby and athletics because I was representing the county at football; at twelve years old, I played for Warwickshire. So I had a fair idea that other people thought I was good, too. Did I enjoy it? Well, it was certainly better than rugby, which I hated. I was skinny, really skinny, and whenever we played rugby I just used to get mullered. And yes, of course I enjoyed it. I loved it. But if I am honest, it was also a good way of getting out of the house, especially at weekends. If Dad came to watch it was a special relief because at least that meant he wasn’t at home playing country and western, deafening all the neighbours, and giving Mum a hard time. He didn’t always come to watch, though. On those days, you’d come home and Dickie Davies would be on the telly, and while you desperately tried to watch the results, Dad would be busy trying to prove to you that he was a better guitarist than Hank Marvin. Sometimes, he didn’t even ask you the score, or whether or not you’d made any goals. I got used to it.

I had plenty of setbacks along the way, though, my progress was hardly meteoric. For one thing, we moved so often that I always had to secure a place in a new team. Then, when I was fourteen, I had the most terrible footballing accident. I was playing in a county match, in Leamington Spa. In the first two minutes of the game I went up to head a ball, and the miracle was that the ball went straight into the back of the net. Unfortunately, along the way, the goalkeeper had managed to punch me in the stomach and the combination of my exuberance and his mistaking the height of my jump meant that he somehow perforated my spleen. What a nightmare.

I went down and, at first, I thought I was only winded. The referee came over and sat me up and made me do all these sit-ups. I felt dizzy and weird. So he sent me off to get some water. I went to pee and suddenly I was peeing blood, and two minutes later I collapsed. An ambulance was called.

In the hospital, they didn’t know it was my spleen. First, they thought it was my appendix; then they thought it was a collapsed lung. That night, I was doubled over in pain. I was crippled with it and was crying my eyes out. The immense fucking agony, you would not have believed it. The doctors didn’t know what to do. Dad was away for some reason, in Texas, I think, and no one could get hold of Mum, so there was no one to sign the consent forms. In the end, they took me down to surgery anyway and somehow managed to repair the damage, though they took my appendix out as well, in the end. I was scared. I wanted Mum.

The operation really knocked me back. But there was worse to come. Two weeks later, an abscess developed internally. So it was back into hospital. This time, I had blood poisoning. All told, my recovery took three months from start to finish. I couldn’t do anything physical. I couldn’t run, I couldn’t jump and I couldn’t train. That was a terrible blow for a fourteen-year-old boy. And then when I started kicking the ball again, I was nervous about going into a tackle. I had lost my confidence.

If Dad had been there, at the hospital, if he’d understood how serious the situation had been, he might have been a bit more sympathetic. But he wasn’t. When he eventually came back, he announced that he’d managed to get some construction work in Amsterdam, and that he was going to take me with him while I convalesced. I was really excited, but only for one reason. I wanted to go and look at the Ajax stadium. The trouble was, it was only about ten weeks since the operation, I still wasn’t as well as I should have been, and Dad was hardly the kind of man to take care of me. For days, I was just left to wander round this stadium. We were in bed-and-breakfast accommodation, so he would go off to work (though that, predictably, lasted about three weeks), leaving me behind with four guilders to my name. You don’t realise it till later – that you’ve been abandoned. I think now: fuck, I was on my jack, wandering around, a fourteen-year-old boy who’s just had major surgery. It was fun, going to the Ajax stadium one, two, three times. But then – even the fucking gardeners got to know me. That was a very, very strange trip.

I had pictures of my heroes, Kenny Dalglish and Kevin Keegan, on my bedroom wall, but I never thought I’d be professional. Apart from anything, even after the accident, I still had terrible problems with my feet. I was cramming my feet into boots that were too small – the ethos of the day was to get boots that were a size too small. Even my coach told me to do that. Some Saturday nights, I’d sit on the side of the bath, wearing my boots, with my feet in hot water, trying to literally mould the leather around them. To this day, I’ve got toes that are bent at the end – hammer toes. By the time I’m an old man, they’ll be like claws. I never had the money for decent boots, even if they’d been the right size. I had to make them last and then, when they were finally worn out, when they looked like a few bits of old cardboard tied together with string, Mum had to secretly slip me money to buy a new pair.

When we moved down to Banbury, I began playing for Banbury United. I suppose that’s when I started getting noticed, though I was only paid my expenses because I was still at school. I played left back. Every term, players from our team were invited up to Oxford United, where they trained with the third or fourth team, and then played for the reserve side, which meant that they got to spend the most amazing week up there. I was picked up by coach and taken there – the first time that I’d been made to feel special, or any good at all, really. And then the travelling became more of a regular event – though I was crap at that. The coach used to make me feel so ill. A small bowl of porridge for breakfast and then, an hour later, I’d be sick as a dog. Hardly the hard man.

I remember my first serious game like it was yesterday. Dad was away and I couldn’t take Mum because, well, you don’t take your mum to football, do you? It was an English Schools competition, Oxfordshire County vs Inner London, and it was to be held at Loftus Road, the ground of Queens Park Rangers, in London. Amazing. A big, fucking stadium instead of the cow patch we had to play on in Banbury, and all the London players were from the youth teams of Chelsea, Tottenham and Arsenal. I thought we were going to get absolutely hammered – that the score would be 8-0 or something. These guys were bigger and stronger than us. But the funny thing was that we beat them 2-1. But it was a dirty game. I was taken off, fifteen minutes before the end of the second half, after a bad tackle to my knee. Another injury from which it took me ages to recover. Perhaps I was doomed when it came to football.

After I’d recovered, I played in an FA Cup youth game and it was there that a Rangers scout spotted me. They asked if I’d like to spend a week of my next summer holiday with the club. Fucking hell. I couldn’t believe it. It wasn’t just the fact that it was a professional club; it was RANGERS, the one that would really have an impact on the way Dad felt about me – or so I thought. The trouble was, Mum and Dad were going through a really shitty time then, and in a way, it put me under even more pressure. A part of me didn’t want anyone to know, just in case I couldn’t pull it off. I didn’t want to let anyone down and, in doing so, unwittingly make things even worse between them. By this point, I was sixteen and was pushing the upper age limit as far as breaking into professional football went. It was make-or-break time.

That first week was hard. I didn’t have a good time at all. I had an English accent, for one thing, so basically they just kicked the shit out of me for that. And they also made me use my right leg, which was fucking useless. We weren’t allowed to rely on only one foot, in much the same way as, in the kitchen, you must be able to chop with both hands. I’m naturally left-handed, but I can chop and peel with my right hand so if I cut myself, I’m okay – I’m prepared. Anyway, after that first week, I came back and I just hated Rangers. I hated the guts out of them. I had no problem with the training – I’ve never been afraid of hard work – but then, in the afternoons, after training, we had gone on to play snooker and eat for Britain. Food in Scotland was bad, then – unbelievably bad. It still is, in most cases. It was pie and gravy, pie and beans, or what the Scottish call a ‘slice’ – these big, square, processed slabs of sausage meat. Fucking hell. I didn’t have what you’d call a sophisticated palate, but I couldn’t stand it. And although I was in digs, with the other lads, I was very lonely. I wished I had a Scottish accent, something that would have made them feel more comfortable around me.

‘I was born in Johnstone, and Mum and Dad moved south,’ I kept trying to tell them. ‘But my gran and my uncle and aunt all live in Port Glasgow.’

They, of course, weren’t having any of it.

I suppose after that first week up there, I thought I’d really fucked it up. I was called back three times. The process was horrible, and I was in two minds about begging for a fucking contract out of Rangers. I was settled in Banbury in the flat with Diane and I’d started a foundation course in catering and it was going well, and there was this feeling, deep inside me, that something else was bubbling up. I was starting to get excited about food. Also, though Mum and Dad’s relationship was really going pear-shaped, they had moved back up to Scotland, and I was enjoying my freedom. I had my first serious girlfriend, I’d started working in a local hotel, I had a bit of money, and there was always Banbury United if I wanted football. I got about £15 a game. I wasn’t complaining. Still, I was just waiting for that call.

Mum phoned. She told me to contact my Uncle Ronald: he had some good news for me about Rangers. So that was what I did. ‘Look, things have moved on,’ he said. ‘I told you they were going to watch you, and they have, and they’re going to invite you back up.’

He gave me a number to call. It was for one of the head coaches. I couldn’t understand a word he was saying: he was speaking far, far too fast. But finally he said: ‘We want you back up. Can you bring your Dad to training on May seventeenth?’

I thought: oh, shit. At that point, I was barely speaking to Dad. I wasn’t even allowed to call the house. The trouble was that the first people the club want to talk to are your parents. They want to know that you’ve got security at home, that you’re properly supported. I was thinking: fuck, am I properly supported? No. I’m sixteen, and I’m living on my own, fending for myself. I rang Mum and asked her to tell him. I couldn’t face doing it myself.

So she did tell him and, all of a sudden he was…I don’t know. Not nice, exactly, but smarmy. He was excited now. I guess he had his eye on the main chance. He was going to live vicariously, through me. How did I feel about this? Wary and nervous. I knew he was drinking; I knew he’d been horrible to Mum; I knew what Yvonne had been through. The only thing that kept me going was the fact that Dad had promised to buy Mum a house – the first time he’d ever suggested such a thing. I hung on to that promise for dear life. I picked up on that one tiny moment, and managed to convince myself that he must have got his shit together at last. Still, it all felt so false – everyone pretending to be best mates, Dad and my uncle suddenly being so involved in my life. I had to live at home again, and take Dad to training with me every day. Being back there, I knew that things weren’t at all right. I felt it instantly. It was almost like Mum and Dad were staying together for the sake of my future at Rangers. I couldn’t bear that. It was pressure, massive pressure. It wasn’t as though I was in love with Dad and he had this amazing relationship with Mum, and all I had to do was concentrate and play football. I was worried. It was all so precarious – a house of cards that could tumble down around my ears at any moment.

This time, the training was going exceptionally well. I started playing in the testimonial games, and I was included on the first-team sheet, which was amazing. It was great, turning up to meet the bus when we were playing away from Ibrox, standing there waiting in your badge and tie, all spruced and immaculate as if you were off to a wedding. It was such a thrill. Outside the stadium, you’d be signing things like pillow cases and the side of prams, and families would turn up with their kids to have their trainers signed. Of course, they didn’t know me from Adam. They didn’t have a clue who I was. I was never a famous Rangers player because I was a member of the youth team. But, on the other hand, I was part of a squad that was doing well. The team has such a following that if you’re wearing the gear – you’re in, and that’s that.

I played for the first team twice, but only in friendlies, or pre-season. In those days, Ally McCoist had just broken into the first-team squad – we still know one another now, though for different reasons, which is really weird – and Derek Ferguson was captain of the under-21s. But it was a bad time for me, stars or no stars. Dad’s duplicity was really getting to me. Then they said: ‘We’re going to continue watching you. We’re really excited. We are going to sign you – but it’ll be next year rather than this.’ Well, that was tough. I knew I was going to go back – how could I not – but by this time, I’d been offered a cooking job in London. Somewhere, I’ve still got the letter offering it to me. It was a new 300-seater banqueting hall that had opened at the Mayfair Hotel called The Crystal Room. They were looking for four commis chefs: second commis, grade two. I don’t know what the fuck that means, even now – it’s a posh kitchen porter, basically. But the salary was £5,200 a year. Anyway, I told them that I wasn’t available to start and went back up to Rangers for the third year in a row.

This must have been the summer of 1984. Half the players weren’t there because they were travelling in Canada, so everything was much more focused on the youth players. Basically, they were deciding who was staying, who they were going to sign that year. Coisty was there, and Derek and Ian Ferguson, whose contracts were well under way. They’d been involved with the club since they were boys, and I suppose that’s all I ever really wanted to do, too: to stay put in one place, and play football, and become a local boy.

But if you’re trying to make it in one of the best teams in Europe, and you don’t even sound Scottish, you’re like a huge, fucking foreigner. Luckily, I was getting big and strong and I could just about handle myself. The training went very well, this time. I remember playing in a reserve team game against Coisty. They always used to hold back two or three first-team players, and then they’d give the inside track about what you were like on the pitch. I had a good game. I was hopeful. I was feeling positive.

The following week, we were playing a massive testimonial in East Kilbride. I couldn’t believe it. I was in the squad, and I got to play. There must have been about 9,000 supporters at the game. The trouble was that they kept moving me around the pitch, playing me out of position. First I was centre back. Then I played centre mid-field, where you’ve got to have two equally strong feet, and you have to be able to twist and turn suddenly. I was really pissed off, and then, just to make things even worse, I got taken off fifteen minutes before the end. They must have made at least seven different substitutions that day. Never mind. I trained for another two weeks, and then I played in another youth team match. Another really, really good game. I was starting to think that I might be in with a chance.

Then, disaster. The pity of it is that my football career effectively came to an end in a training session – one of those bizarre training accidents where you barely realise what it is that you have done. I smashed my cartilage, seriously damaging my knee, and stupidly, I tried to play on. There had been one of those horrendous tackles that makes you even more determined not to give up. I would do whatever I was asked to do, no question. We went on to take penalties with our right foot. I’ll never forget it. We had to put a trainer on our left foot and a football boot on our right. The idea was to make your right foot work constantly. So first there was a penalty competition and then, afterwards, we had to take corners with our right foot. It must have been nearly four o’clock when they finally said, right, we’re going to divide into two teams of eleven and play fifteen minutes each way and I want you all to give it everything you’ve fucking got. By this time, we’d been training all day. Well, that was a big mistake. By the time we finished, I was in a serious amount of pain.

Afterwards, I should still have been resting up, but I tried to get back into the game too quickly. I was out for eleven long weeks, getting more and more paranoid, terrified that someone else would take my place on the bench. But no sooner was I up and running again than I played a game of squash. That was a really dumb thing to do. I tore a cruciate ligament during the game, and was in plaster for another four months. I was worried that I wouldn’t regain my match fitness. Once the plaster came off, I started training again like a demon. But I was still in a lot of pain, though I tried to ignore it. After training sessions, I would spend hours in hot and cold baths, trying to ease the pain, to reduce any swelling. Deep down, I think I knew I was in trouble, but I pushed those kinds of thoughts to the back of my mind. I would tell myself: maybe all players are in this much pain. Or: maybe I can work through it. I was determined to put in a third appearance for the first team, and in order to do that, I had to ignore the message my body was trying to send me.

But come the start of the new season, there was no getting away from it. My leg was just not the same, and this had become apparent to my bosses. Jock Wallace, the club’s manager, and his assistant, Archie Knox, called me into their office one Friday morning to give me the bad news. It was all over for me. I was not going to be signed. I was not going to play European, or even first division football. I remember their words coming at me like physical blows. It was so hard to take. But I was determined not to show how broken I felt inside. Years of standing up to Dad had put me in good stead for this performance. I might have wanted to cry, or to shout, or to punch the nearest wall, but I was damned if I was going to in front of these two. I admired Jock and I had always been intimidated by him. I certainly wasn’t going to let the side down now. I gripped my chair, and waited for the whole thing to be over. In those few minutes, all my dreams died. Part of me was wondering how I would manage to walk out of the room.

They suggested I do more physio, and maybe sign with a different club, one in a lower league. So did my father. In fact, he was pathetically eager that I take this advice. I don’t think he could bear to lose sight of the dreams he had had for me. He wanted the good times to roll. He wanted to be able to boast to his so-called friends, who had always been so much more of a success in life than him. Dad was sitting in his van just outside the ground when Wallace broke the news to me; going out there and telling him was one of the toughest things I have ever done. But I wouldn’t let him have the pleasure of seeing me cry, either. On and on he went: ‘You carry on badgering Rangers,’ he said. ‘You prove to them you are fit again.’ But far harder to take was his lack of sympathy for me. He didn’t have a single kind word for me that day, not even so much as a gentle pat on the shoulder. Later on, he even suggested that I might be exaggerating the extent of my injury. So I went home, shut myself away, and had a good cry. I couldn’t face seeing anyone. I suppose I mourned for what might have been. But I was also certain that I had no future in football. Scrabbling around playing games here and there and working some other day job to pay the bills wasn’t for me. I wanted it all, or I wanted nothing. No matter how much promise I had shown, I was always going to be labelled as the player with the gammy knee. I had to let go of the game that I loved. That was hard because I had come so close to making it, and I felt bitter for a long, long time afterwards. But I was certain that I was doing the right thing in making a clean break: I had the example of my father and his so-called music career to encourage me, didn’t I? There was no way I wanted to be a pathetic dreamer like him for the rest of my life. The very idea disgusted me. I wanted to be the best at whatever I did, not the kind of guy that people secretly laughed at behind his back. I needed a new challenge. The only question was: what would that be?

Looking back on this time, I’m struck, once again, by the cruelty of my father, and the way he dominated everything I did, even my football. I loved the game. But my involvement wasn’t about becoming a famous player with flash cars and flash houses and women hanging on my every word. It had so much more to do with proving myself to my father. I remember one night, when he was very drunk, he said to me that he used to think that I was gay when I was a little boy. I will never forget that. What is striking to me about that now is that he was so full of hatred for the idea that I might be gay; I couldn’t help but wonder why the idea made him feel so threatened. What was his problem?

The film Billy Elliot has an amazing resonance for me. I remember going to see the musical version of it on stage in London with Tana. Fucking amazing. There was a moment – you can probably guess which one – when it took me straight back to my bedroom, to Dad being furious with me and accusing me of being gay. It moved me so much that I could hardly swallow for twenty-four hours. I know that world, where things are so hard. Mum trying to bake bread because we hadn’t even enough money to buy a loaf; us all depending on fucking powdered Marvel milk for months and months on end. No wonder I was so fucking thin. You never forget all that, and when you see the same kind of life up there on the big screen, you have one flashback after another. Not to be self-pitying, but it can leave you in pieces.

Of course, going into cooking probably got Dad thinking all that crap about my being gay all over again. He always thought that any man who cooked had to be gay – and he wasn’t alone. When I started out, this country had no culture of great kitchens. It wasn’t like France – cooking was a suspect profession for a man. You may as well have said that you wanted to be a hairdresser.

When I first started working in a kitchen, I kept the two worlds – football and food – as far apart as I could. One night, when I was at Harvey’s, Coisty came in for dinner with Terry Venables. I didn’t say a word to anyone. I didn’t want the other cooks to know about my life at Rangers, and I didn’t want anyone connected with football to see me in my whites. It seems bloody silly now. But back then, it felt like a matter of life and death. What a long way I have come.

CHAPTER THREE GETTING STARTED (#ulink_3ec78cf7-8cb3-5362-a09e-022906165986)

GROWING UP, THERE wasn’t a lot of money for food. But we never went hungry. Mum was a good, simple cook: ham hock soup, bread and butter pudding, and fish fingers, homemade chips and beans. We had one of those ancient chip pans with a mesh basket inside it, and oil that got changed about once a decade. I loved it that the chips were all different sizes. She used to do liver for Dad – that was the only thing I refused to eat – and tripe in milk and onions; the smell of it used to linger around the house for days and days. Steak was a rarity: sausages and chops were all we could afford. We were poor, and there was no getting away from it. Lunch was dinner, and dinner was tea, and the idea of having a starter, main course and pudding was unimaginable. Did people really do that? If we were shopping in the Barras, and we decided to have a fish supper, we children all had to share. There was no way we would each be allowed to order for ourselves. Later on, when Mum had a job in a little tea shop in Stratford, she’d bring home stuff that hadn’t been sold. We regarded these as the most unbelievable treats: steak-and-kidney pies and chocolate éclairs.

We were permanently on free school dinners. That was terrible. It used to make me cringe. In our first few years, of course, none of the other kids quite cottoned on to what those vouchers were about. But higher up the school it became fucking embarrassing. They’d tease you, try to kick the shit out of you. On the last Friday of every month, the staff made a point of calling out your name to give you the next month’s tickets. That was hell. It was pretty much confirmation that you were one of the poorest kids in the class. If they’d tattooed this information on your forehead, it couldn’t have been any clearer. So yes, I did associate plentiful food with good times, with status. But I’d be lying if I said I was interested in cooking. As a boy, it was just another chore. My career came about pretty much by mistake.

I latched on to the idea of catering college because my options were limited, to say the least. I didn’t know if the football would work out. I looked at the Navy and at the Police, but I didn’t have enough O levels to join either of them. As for the Marines, my little brother, Ronnie, was joining the Army, and I couldn’t face the idea of competing with him. So I ended up enrolling on a foundation year in catering at a local college, sponsored by the Rotarians. It was an accident, a complete accident. Did I dream of being a Michelin-starred chef? Did I fuck! The very first thing I learned to do? A bechamel sauce. You got your onion, and you studded it with cloves. Then you got your bay leaves. Then you melted your butter and added some flour to it to make a roux. And no, I don’t bloody make it that way any more. I remember coming home and showing Diane how to chop an onion really finely. I had my own wallet of knives, a kind that came with plastic banana-yellow handles. At Royal Hospital Road, we wouldn’t even use those to clean the shit off a non-stick pan, let alone chop with them. But we were so proud of them – and of our chef’s whites. I treated my knives and my whites with exactly the same love and reverence as I used to my football boots. I sent a picture of me in my big, white chef’s hat up to Mum in Glasgow. I think she still has it. I was so fucking proud.

Meanwhile, I had a couple of weekend jobs. The first was in a curry house in Stratford – washing up. The kitchen there wasn’t the cleanest place in the world, and they worked me into the ground. Then, in Banbury, Diane got me a job working in the hotel where she was a waitress. Again, I was only washing up, but that was when I first got the idea of becoming a chef. I was in the kitchen, listening to all the noise, and I was fascinated. I couldn’t believe the way people were shouting at each other. I was working like a fucking donkey, but the time used to fly by. I was enraptured.

After a year, one of my tutors suggested to me that I start working full-time, and attend college only on a day-release basis. I’d made good progress. That said, I was by no means the best kid in the class. In college, you can spot the students from the council estate, the ones who are basically middle-class, and the ones whose parents are so in love with their daughters that they send them to cookery school. God knows why. There are three tiers, and you can spot them a mile off. I was in the first group. I didn’t get distinctions, and I wasn’t Student of the Year. But I did keep my head down, and I did work my bollocks off. I pushed myself beyond belief. I was happy to learn the basics. I didn’t find it demeaning at all.

So I started work as a commis at the place where I’d been washing up: the Roxburgh House Hotel. The dining room was pink – pink walls, pink linen – all the waiters were French and Italian and all the cooks were English. My first chef was this twenty-stone, bald guy called Andy Rogers. He was an absolute shire horse. The kind of guy who would tell you off without ever explaining why. Dear God, the kind of food that he encouraged us to turn out. I shudder to think of it. The cooking was shocking, the menus hilarious. Take the roast potatoes. They started off in the deep fat fryer and then they were sprinkled with Bisto granules before they went in the oven, to make sure they were nice and brown. Extraordinary. The foie gras was all tinned.

We used to serve mushrooms stuffed with Camembert. One of the dishes was called a scallop of veal cordon bleu. It was basically a piece of battered veal wrapped around a ball of grated Gruyère in ham. I knew it was all atrocious, even then. I was getting all this information at college, and I would come back and try to apply it. I’d say: ‘You know there’s a short cut. To make fish stock you should only cook it for twenty minutes, otherwise it will get cloudy, and then you should let it rest before you pass it through a sieve, or it will go cloudy again.’ For this, I would get roundly bollocked by the chef. He didn’t give a fuck for college.

I stayed for about six months, and then I got a job at a really good place called the Wickham Arms, in a small village in Oxfordshire. The owners were Paul and Jackie, and the idea was that I would live above the shop, which was a beautiful thatched cottage. Unfortunately, things went pear-shaped there pretty early on. Jackie was in her thirties, I must have been about nineteen, Paul was away a lot; perhaps you can imagine what was going to happen.

Paul was mad about golf, and he loved his real ale. So he’d be off down to Cornwall, in search of these wonderful kegs. I had a serious girlfriend at the time, I’d met her at the college but she was going off to university. So that didn’t stop me. Basically, I was in charge of the kitchen, and a 60-seat dining room, and I wasn’t even properly qualified yet. I was making dishes like jugged hare and venison casserole and doing these amazing pâtés, and just reading endless numbers of cookery books. Locally, everyone loved the food, and it became a kind of hot spot. But I guess that went to my head: I was on my own, completely free, no one checking up on me. I was all over the fucking shop.

One day, while Paul was off on one of his trips, Jackie rang down to the kitchen. ‘Can I have something to eat?’ she said.

‘What would you like?’

‘Just bring me a simple salad, thanks.’

So I got together a salad with a little poached salmon and took it up.

‘Jackie, your dinner is ready.’

And she opened the door – stark bollock naked. I put the tray down, and went straight into her bedroom.

For the next six months, I led a kind of double life. There was Jackie, my teacher, and Helen, my pupil. You know what it’s like when you’re young. It’s awkward and clumsy. Sometimes, at least before I met Jackie, I used to feel that sex was like sharpening a pencil. You stick it in there, and grind it around. But Jackie was teaching me all these things, and it was amazing. The trouble was that Helen got some of the fringe benefits, which meant that she was falling more and more in love with me.

At first, Paul would only be away for a couple of days at a time. Then he started going on golfing trips to Spain for more like a week. That’s when it all got too much. It was getting heavy. Fucking heavy. Jackie told me that she loved me. The truth is that I loved making the jugged hare more than I did having sex with the boss’s wife, but the only reason I was in a position to buy and cook exactly what I wanted was precisely because I was shagging her. Things weren’t exactly going to plan and it was all getting too nerve-racking for me: that he might notice, that we might get caught, the fact that she was always telling me she was in love with me. So I told them that I was leaving to go and work in London. She went bananas.

I actually went back to the Wickham Arms two years later, for a mate’s twenty-first. Someone must have told Paul because, while she was still being very flirtatious, he was clearly not too pleased to see me. I was in the kitchen, talking to the new chef, telling him how good I thought the buffet was. There was a carrot cake sitting there and, without thinking, I stuck my finger in it. Well, one of the waitresses must have snitched on me to Paul because a split second later, he came running in and shoved me hard against the wall.

‘I should have fucking done this three years ago,’ he said. ‘You know what the fuck I’m on about.’

He then took a swing at me, but fortunately one of my mates intervened, which gave me enough time to make a very sharp exit. So I ran from the kitchen, jumped in the car and disappeared into the night. Hilarious. The next time I saw them was quite a long time later, when they turned up at Aubergine in the early part of 1998. They’d opened a new restaurant in a village in Buckinghamshire, and they brought their chef to meet me at Aubergine. By then, a lot of water had passed under the bridge. They had rung me, told me that he was a big fan of mine, and asked if they could come by. I said, sure, of course. It was embarrassing – I mean, I’d moved on, I wasn’t just poaching salmon and chopping aspic any more – but I made out it was good to see them all. The trouble was, they got pissed and a bit leery and then, when they missed the train back to Buckinghamshire, they started demanding that I offer them a bed for the night. We did try to ring around and find them a room, but hotels were £250 per night, which seem to make them even more aggrieved. I don’t know what they expected me to do – ask them back to sleep on the floor of my flat as well as cook their food? Well, I wasn’t having that. Tana was pregnant at the time, so I sent out their dessert and then I fucked off.