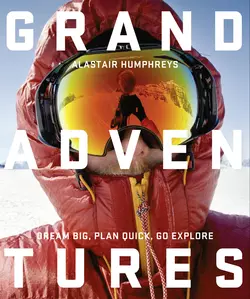

Grand Adventures

Alastair Humphreys

Recommended for viewing on a colour tablet.Adventure – something that’s new and exhilarating, outside your comfort zone. Adventures change you and how you see the world, and all you need is an open mind, bags of enthusiasm and boundless curiosity.So what’s a GRAND ADVENTURE – it is the most life-changing, career-enhancing, personality-forging, fun adventure of your life.Following on from his popular Microadventures, in Grand Adventures Alastair Humphreys shines a spotlight on the real-life things that get in the way: stuff like time, money or your other commitments. Grand Adventures is also crammed with hard-won wisdom from people who have actually been there and done that: by boat and boot, car and kayak, bicycle and motorbike. People who had one epic trip then returned to normal life, or who got bitten so badly by the bug that they devoted their life to the pursuit of adventure. Young people, old people. Men, women. Mates, couples, families. Extraordinary, inspiring people. People like you.Saving your pennies, overcoming inertia, generating momentum, getting out the front door: if you want it enough, you can do it.Tiny steps to a grand adventure.Are you in?

COPYRIGHT (#u3689e309-d6a2-59bd-97c6-37b83ba5049b)

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com (http://WilliamCollinsBooks.com)

This eBook edition published by William Collins in 2016

Text © Alastair Humphreys, 2016

The author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Cover photograph © Alastair Humphreys

Cover design by This Side

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this eBook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

Source ISBN: 9780008129347

Ebook Edition © March 2016 ISBN: 9780008131944

Version: 2016-03-03

For my parents,

Who taught me to save up, work hard

and make stuff happen.

© Alastair Humphreys

CONTENTS

COVER (#u215f21bd-c653-549e-b8fd-1b58d745b9ee)

TITLE PAGE (#u60bab3c4-2c80-5b0e-9d03-3337171d870b)

COPYRIGHT

DEDICATION (#uf30357e9-dc73-5c9e-bc0b-4f2cf9dde84b)

INTRODUCTION

Part 1 PLAN

MONEY

TIME

COMMITMENTS AND RELATIONSHIPS

HATCH A PLAN

KIT LIST

Part 2 CHOOSE

BICYCLE

FOOT

ANIMAL

WATER

MOTOR

TRAVEL

CLIMB

EVERYDAY

GRANDER

BIOGRAPHIES

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION (#u3689e309-d6a2-59bd-97c6-37b83ba5049b)

Everyone loves adventure. Bookshops have bulging travel sections. Adventure film festivals are springing up all over the world. The web groans with exciting expedition blogs. I love adventure so much that I turned it into my job. I am a professional adventurer. It says as much on my business card, so it must be true. (Never mind that I made them myself in one of my many procrastinating-from-book-writing mornings.) I write books, give talks and make films about the adventures I’ve done, such as cycling round the world, crossing oceans or staggering through the heat of deserts. Enough people enjoy hearing these stories for me to earn a living from them. This means that more people read about adventures than go on big trips themselves. But this book aims to help you realise that grand adventures are within your grasp, that you can begin taking the steps necessary to make them happen for you, too. Why settle for reading about adventures when you could be out in the wild doing them yourself?

‘Why settle for reading about adventures when you could be out in the wild doing them yourself?’

Many of my friends are also adventurers. They’ve climbed great mountains, trekked to the Poles, exciting stuff like that. These are special experiences. I love sitting in the pub with my adventurous friends, listening to increasingly far-fetched tales as last orders approaches. But here’s an important thing: I know these guys and girls well enough to see that they are not particularly special people. They are ordinary people, but they do things that many people deem to be more than ordinary, even extra-ordinary. Being an adventurer is not a genetic gift. I know, for example, that I certainly am not brave, strong or athletic, yet I claim to be an adventurer. Usain Bolt was born fast. Albert Einstein was born brainy. Living adventurously, however, is nothing more than a choice.

© Archie Leeming

When I left university I made the choice to make the best I could of my abilities and resources and see how far I could ride my bike. I didn’t have a fancy bike. I didn’t ride fast. I didn’t spend much money. I got lost a lot. I napped under trees. I carried a bicycle repair book because I had little idea about bottom brackets or rear derailleurs. And yet I eventually succeeded in cycling the whole way round the world. I spent £7000 on the four-year trip. I did not choose to do it on such a shoestring: it’s just that this was the sum total of my worldly wealth. I preferred to get going and make it happen rather than saving and saving and never beginning. Four years of banana sandwiches was a small price to pay for eking out my money into so many memories.

When people dream of adventure they are generally not discouraged by the difficulties of the journey itself. Extremes of heat and cold; basic and uncomfortable conditions; the physical and mental struggle: these are actually often part of the appeal! The struggle, many of us feel, is preferable to boring routine.

So what is it that actually gets in the way, if not the hazards of the wild? Why do lots of people long for adventure and enjoy reading about it but not many actually get out there and do it?

I didn’t think that it could be explained by a lack of practical skills, fitness or equipment. It’s not as concrete as that. I guessed that what inhibits most people are the mental barriers in their head: it’s too hard, too scary, too uncertain…

Through my blog, I decided to ask what it was that stood between people and the adventures they dreamed of. From around 2,000 responses, here are the most common issues:

— Time

— Money

— Family / partners / commitments

— Fear

— Society pressure

— No companion to go with

— Getting time off work

— Getting work afterwards

And these were mentioned, too:

— Solo female travel / safety

— Lazy / procrastination

— School holiday system

— Lack of knowledge

— Ideas

— The unknown

— Kit / logistics

— Lonely

— Fitness / health

I found it fascinating that not one person mentioned the worry of falling down a crevasse or getting eaten by a tiger. The greatest obstacles to people’s adventures all lie before the journey even begins. In other words, getting to the start line is the hardest part!

Wrestling snakes, paddling rapids, tying a bowline with your teeth, pitching a tent in a typhoon: all this stuff is so much easier than getting off the sofa, committing to action and beginning.

© Alastair Humphreys

A similar example sometimes happens out on an expedition: leaving the tent when a blizzard is howling outside and your sleeping bag is snug can feel nigh on impossible. But when you do get out (it’s usually a weak bladder rather than a strong will that eventually forces you into action), the world is never as grim as you’d imagined it to be from the safe cocoon of your sleeping bag. The raging blizzard you’d pictured is often just a bit of windy snow. Feeling sheepish, you pack away the tent and get on with the journey.

What’s more, the practical preparations for launching a journey are also far easier than mustering the cojones to commit in the first place, to do something difficult and daunting and daring with your life.

There is a lovely Norwegian phrase that translates into ‘the Doorstep Mile’. It refers to how hard it is to begin something, how hard it is to get out your front door and commit to action. This book helps tackle the Doorstep Mile.

‘Do you dream of having a massive adventure but can’t see how you will ever get the chance to do it? If so, this book is for you!’

The first half of the book tackles the barriers that make it hard to begin. The second half helps you choose which adventure is right for you.

Do you dream of having a massive adventure but can’t see how you will ever get the chance to do it? Do you long to explore but don’t know how to begin? Do you look enviously at other people’s trips but think it’s not what ‘people like you’ do? If so, this book is for you!

My aim is to help you commit to begin planning your dream adventure, to get you in motion. That’s all. After that, the rest is easy – and up to you.

© Leon McCarron

© Alastair Humphreys

This book helps you shine a spotlight on what is getting in the way of the most amazing, life-changing, career-enhancing, personality-forging, memory-making adventure of your life. If you really, truly want to experience a big adventure, you can do it. You can do it. You can. Grand Adventures looks at the obstacles stopping you and shows that there are ways round them, if you choose to do it. Will you?

I spent an absorbing year interviewing many adventurers for this book, seeking hard-won wisdom from people who have been there and done the kind of trips we all dream of. I’m only sorry there was not space to include them all. (The in-depth interviews are all available to read on www.alastairhumphreys.com/GrandAdventures (http://www.alastairhumphreys.com/GrandAdventures).) They’ve done it all: Everest, the North and South Poles, the Amazon and Sahara, all seven continents, the oceans – even going up to Space! All of them once took that huge step of committing to their very first adventure. I hope that you will take inspiration from them because they were once just like you: itching to hit the road but nervous about how to make it happen.

There are stories and photographs from men and women who have travelled by boat and boot, car and kayak, bike and motorbike, home-made raft and hi-tech spaceship. People who had one great trip then returned to normal life. Those bitten so badly by the bug that they devoted their life to the pursuit of adventure. There’s youngsters and old folks; men and women; mates, couples and families; fit, fat or disabled. Extraordinary, inspiring people. People like you.

The only thing that stands between you dreaming of adventure and you being an adventurer is committing to it. Together, we’ll show you that, whether it’s cycling to the Sahara, walking across Australia or rafting the Amazon, the longest journeys really do all begin with a single step. They are, in fact, nothing more than lots of tiny, easy steps. Tiny, yes; easy, yes, but you’ve still gotta take ’em.

(#u3689e309-d6a2-59bd-97c6-37b83ba5049b)

(#u3689e309-d6a2-59bd-97c6-37b83ba5049b)

Most people cite money as one of their big worries in life. It’s certainly seen as the largest obstacle to adventure. When people say to me ‘I’d love to do a big adventure, but…’ it is usually money that appears to be stopping them.

People who daydream about winning the lottery often say, ‘I’d go and see the world. I’d have an adventure!’ But you won’t win the lottery. That’s not the way the world, or probability, works, alas! (Especially if you’re not wasting your money on lottery tickets in the first place and instead are saving for an adventure.)

Will you just accept that because you won’t win the lottery you won’t have that dream adventure? Or maybe you’ll settle for doing something when you retire? (Gambling on the hope that you are not dead or decrepit by then…)

Before you do, there are two vital things to realise about money and adventures:

Adventures can be much cheaper than you might imagine. Not only that, it’s relatively painless to save enough money without having to rely on a lottery ticket.

If I can demonstrate that the biggest hurdle is easy to get over, hopefully it will convince you that any other obstacles in your way can be fixed, too.

When it first dawned on me, this simple little sum stopped me in my tracks – for its simplicity, and for its implications.

If you put aside £20 a week, within a year you will have saved £1,000. One thousand pounds. In all its glory, a thousand quid…

£20 is not a particularly large amount of money for me, and that’s probably the case for many of us who are in the privileged position in life of even being able to dream of adventures. I spend £20 in the pub, or on a meal to cook for a few friends. £20 is within my financial comfort zone.

But £1,000 does feel like a large amount of money to me. For much of the world, of course, it’s an impossibly vast sum. For some people it’s mere loose change. But I imagine that most people reading this book are, approximately, on a similar financial level to me: £1,000 sounds like a lot of money, but it’s more or less achievable if I set my mind to saving £20 a week.

I know from experience that £1,000 is enough to fund a phenomenal trip. I once flew to India, walked from one coast of the country to the other, and then flew back home for far less than that. I have cycled thousands of miles through extraordinary places for £1,000, a grand adventure. Almost all of the trips I have done – including canoeing the Yukon, crossing Iceland and cycling round the world – I funded by saving up my own money and then doing the trip as cheaply as I could manage.

If you travel under your own steam, eat inexpensive food and sleep in a tent then expeditions don’t cost much once you’ve bought the essential equipment and plane ticket.

Some of my more recent trips, in places such as Greenland and the Atlantic, have required sponsorship, because they’re beyond the depths of my wallet. But I’m a strong believer that you should walk before you run. Building up a solid CV of expeditions will help you secure sponsorship further down the line, but the best thing to do is begin with exciting projects that you can pay for yourself. Some of the journeys described in this book are expensive, but the lessons you can draw from them will help with any debut, budget expedition.

Saving a little bit of money regularly and seeing how that accumulates into a large amount is a handy metaphor for everything in this book. Things that seem daunting at first are not nearly so bad once you begin chipping away. Start small, but do start. Start rubbish, then get good along the way.

I have chosen £1,000 as a pretty arbitrary figure upon which to hang the adventures in this book simply because I loved the neat simplicity of putting aside £20 a week then hiking off into the sunset a year later. You can do something amazing for less than £1,000, although many journeys will cost more than that. It doesn’t really matter; this is not the book to help you with detailed budget planning. It’s simply the spark which, I hope, will light the fire inside you and get you to commit to the journey of a lifetime. After that, you’re halfway there.

© Alastair Humphreys

A more useful way of thinking about expedition budgets than absolute figures such as ‘£1,000’ is to consider how long it takes you to earn the money. There is the absurd social convention of spending between one and three months’ salary on an engagement ring. (If anybody ever proposes to me I would far rather they spend that money on a grand adventure for the two of us than a highly squashed pebble.) So rather than focusing too much on the notional figure of £1,000, perhaps you should try to think about what fraction of your income you’re able to save for an adventure.

Throughout this book, never think, ‘I can’t do that’. Instead, try to think of a way round the difficulty that still fits within your particular circumstances. If you can’t afford to save £20 a week, save £10 instead: you’ll still get there in two years. Just put aside what you can when you can. More often than not, replacing the words ‘I can’t do that’ with ‘I choose not to do that’ will give you an honest insight into how much you truly want to make something happen. Are you really in the position of saying ‘I can’t save £20/£10/£5 a week’ or is it more like ‘I choose not to save £20/£10/£5 a week’?

If I gave you £1,000 to go on an adventure, what would you go and do? Grab a pen and write a list of ideas. Physically write them, don’t just think it – you’re more likely to make stuff happen if it’s set down in black and white.

I am not actually going to give you £1,000. I’m a Yorkshireman. However, I am going to help you begin saving it. If you can save up that much money and therefore eliminate the biggest perceived barrier that stops people having the adventure of their lives, what else can stop you making this thing happen?

HERE ARE A FEW SUGGESTIONS FOR IDEAS OF ADVENTURES YOU COULD HAVE FOR £1,000:

‘I would go south, hitch-hiking into Africa.’

Steve Dew-Jones, hitch-hiked to Malaysia.

‘I would leave the front door with my camping kit, and I’d just walk. It’d be really interesting to walk without a destination, away from home day after day. It wouldn’t be very expensive, so that £1,000 might last a very long time.’

Hannah Engelkamp, walked 1000 miles round Wales with a donkey.

‘I’d jump on a skateboard and go around India.’

Jamie McDonald, ran 5,000 miles across Canada.

‘I’d go climbing illegally in China – it’s the permits that cost so much. Or I’d go somewhere you don’t really need permits, like Kyrgyzstan or Tajikistan.’

Paul Ramsden, climbed ‘lots of big mountains’.

‘I’d cycle to Istanbul. If I made sure my bike was fairly worthless, I could leave it there and then just fly home for £70 at the end.’

Tom Allen, cycled, packrafted, walked, hitch-hiked and rode horses on five continents.

‘I like the idea of sea kayaking from Finland to Sweden through the archipelago.’

Karen Darke, Paralympian and expeditions by bike, sea kayak and sit-ski.

‘I would sail out to the West Face of Ball’s Pyramid and climb it: it’s only 2,270 foot high, but 312 miles off the east coast of Australia.’

James Castrission, kayaked the Tasman Sea.

‘I’d like to walk to the midnight sun. Set out from home and walk north up to the Arctic Circle.’

Sean Conway, first person to complete a ‘length of Britain’ triathlon.

Some people may consider spending £1,000 on adventure to be a flippant use of money. I know that it is not saving the world, but I suspect that, when I’m on my death bed, I’ll be more grateful for the experiences that adventures have given me than for spending that amount of money on things like a massive TV or a trendy handbag.

You know that when you are old and looking back on your life you’d prefer to remember a bike ride through Borneo or a train journey across Tibet rather than the extra work you did and the extra £1,000 you’re going to have to pay death duty on. So why don’t you get out there and do it?

THERE ARE TWO WAYS TO GET MORE MONEY IN LIFE:

Earn more. Or spend less. I’m definitely not the right person to advise with Point 1, but here are some ideas to help you begin spending less money.

Remember, in order to save £1,000 for your adventure you need to save less than £3 each day for a year.

Think about all the ways you spend money and where you can make some savings. Consider the small changes you can make which will help lead to a big adventure and a big change in your life. I’m not advocating anything drastic, just tiny tweaks that won’t hurt day-to-day but will accumulate into big piles of cash. If you think you’ll struggle, try writing down every single thing you spend in the course of a week – you might be surprised where you can make some savings for your Adventure Fund.

If you’re serious about saving money, do some Googling: there are blogs more knowledgeable and specific on the subject than I could ever pretend to be. But I hope this section will get you thinking. All the examples below are worth trading for the adventure of a lifetime, especially as they generally make your life healthier anyway.

— Daily routine: Cut out a daily takeaway coffee and you’ve almost made it to £1,000 in a year already. Take a packed lunch to the office and you’re really saving.

— Commuting: Can you work from home occasionally? Can you share a lift or cycle one day a week?

— Home bills: Turn your thermostat down a notch and put on a jumper. Wash your clothes at a lower temperature. Have an occasional cold shower (they are good for the soul, the environment and your bank balance!). Sell your telly.

— Entertainment: Eat out less often or search online for restaurant discount vouchers.

— Alcohol: A pint in a London pub often costs £5. One fewer pints a week and you’ve saved almost 25 per cent of your £1,000. If you’re tempted for ‘just one more’, consider that the price of that drink can easily equate to a day on the road in some of the world’s wildest, cheapest and most exciting regions. Which would you rather have? Beer tastes better on a beach in Belize anyway!

— Smoking: Stop it.

— Eat more veg: An average UK family spends £5,300 per year on food. A moment’s Googling leads me to a site of recipes that will feed a family for just £1,168 per year.

— Stick to essentials: Only buy stuff you really need. We all suffer from ‘stuffocation’. Look around your house and ask, ‘Do I need this?’ When did you last use or wear some of it? Would you miss it if it were gone? Sell ten things on eBay and transfer the proceeds to your Grand Adventures fund. eBay is a great place to buy all the kit you need for your adventure, too. You can save a fortune this way.

I hope I’ve demonstrated that saving £1,000 is achievable through taking small steps. Remember that the same metaphor applies to all the other obstacles standing in your way. Overcoming inertia, generating momentum, getting out the front door, beginning: if you want it enough, you can do it.

Tiny steps. Grand adventures. Are you in?

WISE WORDS FROM FELLOW ADVENTURERS

JAMIE BOWLBY-WHITING

HITCH-HIKED THOUSANDS OF MILES, RAFTED THE RIVER DANUBE AND WALKED ACROSS ICELAND

It is possible to travel entirely without money by a combination of free camping, Couchsurfing and foraging.

HANNAH ENGELKAMP

WALKED A LAP OF WALES WITH AN ECCENTRIC DONKEY

Money-wise, if you do something that involves walking and camping, it’s likely to be an awful lot cheaper than ordinary life. Really, it’s a matter of getting your head around stopping what you’re doing now and just doing something completely different.

DAVE CORNTHWAITE

MADE 25 NON-MOTORISED JOURNEYS

I learned to just downsize my life and limit my outgoings, which I think is a nice lesson overall.

ALICE GOFFART & ANDONI RODELGO

CYCLED ROUND THE WORLD FOR SEVEN YEARS

During those years, including having two children on the way, we spent less than €50,000. That’s what some people spend on a car, and nobody asks them how they did it.

ANTS BOLINGBROKE-KENT

NUMEROUS VEHICLE-POWERED EXPEDITIONS

My money diet mantra was ‘no unnecessary spending’. The only clothes I bought were off eBay or from charity shops (difficult as a lover of fashion). I made sure my saving didn’t overly impact on my relationship, though. This adventure malarkey can be rather selfish and I wanted to save cash, but that couldn’t mean becoming a miserly bore.

GRAHAM HUGHES

VISITED EVERY COUNTRY IN THE WORLD WITHOUT FLYING

When asked how can I afford to travel so much, I feel like retorting with: how can you afford your rent? To keep a dog? To have children? To smoke? When I travel, I have no rent to pay, so 100 per cent of the money I have can go on travel.

JAMIE MCDONALD

RAN 200 MARATHONS ACROSS CANADA

I spent three years saving up for a house. The only reason was because everyone else was doing that. I was just choosing it for someone else’s sake. So I bought a second-hand bicycle for 50 quid out of the newspaper and I flew to Bangkok. And then I cycled home back to Gloucester.

ANDY KIRKPATRICK

BIG WALL CLIMBING & WINTER EXPEDITIONS

Before my first trip to the Alps I was working in a job where I got £100 a week, and just the bus ticket from Sheffield to the Alps cost me £99! I saved one week’s pay, spent it on the ticket and packed in my job. Every penny we spent was considered.

JASON LEWIS

SPENT 13 YEARS CIRCUMNAVIGATING THE PLANET BY HUMAN POWER

I ended up in the clink [prison] in east London for trying to run out the door of the chandlery there with our shit bucket and a scrubbing brush, coming to the total of £4.20. I was rugby tackled by security guards at Woolworths. So yeah, we were just desperate.

© Alice Goffart and Andoni Rodelgo

© Tim and Laura Moss

MATT EVANS

TRAVELLED OVERLAND FROM THE UK TO VIETNAM

I bought a big ceramic savings pot that needed to be smashed to get all the money inside. Every day we came in from work and put all the loose change in our pockets into it. No excuses. This might sound silly but after a while it became normal, and when we finally had a grand ‘Smashing of the Jar’ ceremony, we had £962.28 in it. That’s quite a lot of money for a small daily ritual that didn’t seem to take much effort. The funny thing was, once we’d saved up the money without living like hermits or living on beans on toast, we looked at each other and wondered why we hadn’t been making these changes to our lives since we met. We hadn’t felt unduly broke, we hadn’t lost any friends, and we didn’t feel as though we’d worked our fingers to the bone. Yet somehow we’d saved enough money to have the adventure of a lifetime. All it took was a little thinking, a few tweaks and a bit of willpower.

SEAN CONWAY

FIRST PERSON TO COMPLETE A ‘LENGTH OF BRITAIN’ TRIATHLON

I don’t have much money, so I just got loads of credit cards. That kind of got the funding out of the way initially.

KEVIN CARR

RAN AROUND THE WORLD

Unless what you’re considering is crazy expensive, it’s probably much less hassle to work a part-time second job/overtime than it is to chase sponsors.

PATRICK MARTIN SCHROEDER

TRYING TO CYCLE TO EVERY COUNTRY IN THE WORLD

I know this: travelling made me richer, even if I have less money. The slower you travel, the less money you spend. Money is probably not the thing stopping you, but the fact that you have to leave your comfort zone. That you have to do something scary. Once you step over that line, once you are on the road, everything gets easier.

CHRIS MILLAR

CYCLED TO THE SAHARA

I worked as a rickshaw driver to save some pennies, get fit and learn the basics of bicycle maintenance.

NIC CONNER

CYCLED FROM LONDON TO TOKYO FOR £1,000

We realised with our pay cheques it wasn’t going to be too much of a budget we were going to be living on, so we thought, ‘Right. Let’s work with this and make it a challenge.’

JAMES KETCHELL

CYCLED ROUND THE WORLD, ROWED THE ATLANTIC, CLIMBED EVEREST

I was working as an account manager for an IT company. I moved back home with my parents; this made a big difference to my finances. Not particularly cool when you’re in your late twenties but it goes back to how much you want something. I took on an extra job delivering Chinese food in the evenings.

© Alastair Humphreys

A SHORT WALK IN THE WESTERN GHATS

I once walked 600 miles across southern India because I wanted a challenge but didn’t have the time or money to walk 6,000 miles. I was trying to understand what drives me to go on all these adventures I feel addicted to. In order to understand, I felt I had to push myself really hard…

Head thumping, heat shimmering, sun beating. The loneliness I felt in crowds of foreign tongues, staring at one foreign face. Bruised feet, dragging spirit, bruised shoulders slumped. Can’t think. Can’t speak. Just walk. The monotony of the open road.

These are common complaints on a difficult journey. I often get them all in a single day, and I know there will be more of the same tomorrow. Most days involve very little except this carousel of discomfort. It doesn’t sound like much of an escape.

Yet escape is a key part of the appeal of the road. All my adult life I have felt the need to get away. The intensity and frequency of this desire ebbs and flows but it has never gone altogether. Perhaps it is immaturity, perhaps a low-tolerance threshold. But there is something about rush hour on the London underground, tax return forms and the spirit-sapping averageness of normal life that weighs on my soul like a damp, drizzly November. It makes me want to scream. Life is so much easier out on the road. And so I run away for a while. I’m not proud of that, but the rush of freedom I feel each time I escape keeps me coming back for more. Trading it all in for simplicity, adventure, endurance, curiosity and perspective. For my complicated love affair with the open road.

Escaping to the open road is not a solution to life’s difficulties. It’s not going to win the beautiful girl or stop the debt letters piling up on the doormat. (It will probably do the opposite.) It’s just an escape. A pause button for real life. An escape portal to a life that feels real. Life is so much simpler out there.

But it is not only about running away. I am also escaping to attempt difficult things, to see what I am capable of. I don’t see it as opting out of life. I’m opting in. Total cost: £500, including flight

(Extract from There Are Other Rivers)

CROSSING A CONTINENT

With three weeks to spare, my friend Rob and I decided to cycle across Europe. We flew to Istanbul and began riding home. The maths was quite simple: we had to ride 100 miles a day, every single day. We had £100 each to spend (plus money for ferries), which meant a budget of £5 a day.

I remember the stinking madness of the roads of Istanbul. I remember our excitement as we made it out of the city. I remember reaching the Sea of Marmara and how refreshing it felt to run into the water to cool down. Then it was back on the bike and ride, ride, ride.

Cycling 100 miles a day was really tough for me back then and this was a gruelling physical challenge. But that was what we wanted. We were invited into a family’s home for strong coffee and fresh oranges. We peered at a dead bear beside the road. I waited for my friend for ages at the top of a winding hairpin pass in Greece. I was annoyed at his slowness. But then he arrived with his helmet full of sweets – like a foraged basket of blackberries – that a passing a driver had given him. Those bonus free calories tasted so good!

I remember the satisfaction of seeing the odometer tick over to ‘100’ each day. I remember the simple fun of finding a quiet spot to camp, in flinty olive groves as the sun set over the sea. Those were good days. Total cost: £100 plus flight

© Alastair Humphreys

IS £1,000 REALLY ENOUGH MONEY FOR AN ADVENTURE?

There is an assumption that adventures have to be expensive. They need not be. This is particularly true if you overcome another assumption: that you have to fly far away in order to have an adventure. Hatching an adventure that begins and ends at your front door is not only cheaper, it’s also satisfying. It creates a story that is easier for your friends and family to engage with and get involved with, and it leaves you with fond memories every time you leave your front door in future.

So, if you are trying to do a big trip for less than £1,000, I recommend cutting the expense of a plane ticket. Cycle away from your front door on whatever bike you own or can borrow and see how far you get.

However, you can get some great bargains on plane tickets. For example, if you decide to commit £200 of your £1,000 to a plane ticket, a website like Kayak (www.kayak.co.uk/explore) shows enticing options of where you can go for that amount of money. Writing this now, I had a look at the website. I could fly from London to Nizhny Novgorod for £190. I have never even heard of Nizhny Novgorod but instantly my mind starts to fill with ideas…

Here’s a cursory budget outline to help you start making plans and to realise that trips are neither as complicated nor as expensive as you might fear.

— Boring but important stuff: insurance, vaccinations, first aid supplies: £200.

— Equipment that you don’t already own or can’t borrow from a mate: £400 will get you a lot of stuff from eBay.

— Costs along the way: ferries, repairs, visas, an ill-advised piss-up in a dangerous but exciting port: £200

— Daily food budget: £5 per day. You could easily live on half this amount, or twice this amount, according to how you like to travel. But £5 will buy you pasta, oats, bread, bananas, veg and a tin of tuna, even in an expensive part of the world. Never pay for water. Just refill your bottles from a tap, purifying the water if necessary.

With £200 remaining, you have enough for 40 days on the road at £5 a day. If you set off from your front door and cycle a pretty leisurely 60 miles a day, and have one day off each week, that still amounts to an impressive 2,000-mile journey. You could cycle from London to Warsaw and back, San Francisco to Vancouver and back, or Copenhagen to Marseille and back. New York to New Orleans and back is a bit far, but York to Orleans is definitely do-able… If you choose to walk, run or swim you won’t travel so fast but your equipment costs will be lower so you will have more days on the trail.

You might choose to spend a bit more or a bit less on different things. You’ll probably find your own budget spreadsheet to be a little more complicated than mine here. But I hope you are starting to realise that the financial element of an adventure is within your grasp.

(#u3689e309-d6a2-59bd-97c6-37b83ba5049b)

If you are in the fortunate position of even being able to dream of undertaking a big adventure, getting hold of £1,000 may not be the biggest hurdle. After all, it’s less money than many holidays, kitchen upgrades, wedding dresses or TVs cost. But not many people have both plenty of money and plenty of time (at least not whilst they are still young enough to climb Rum Doodle without their knees hurting).

For many, the scarcest resource in life is time. That is why I wrote Microadventures, a book about squeezing local adventures into the confines of real life. Microadventures challenge you to look at how you spend the 24 hours you have each day and to try to re-prioritise things a little bit.

But grand adventures require more than 24 hours. If you’re yearning to cross a continent, chasing the days west until the sun sets into the ocean before you, you’ll need to find a bigger chunk of time. There is never an easy time to find that time. Too many people are willing to settle for waiting until they retire, and this always makes me sad. The actor Brandon Lee’s grave is inscribed with these words:

‘Because we don’t know when we will die, we get to think of life as an inexhaustible well. And yet everything happens only a certain number of times, and a very small number really. How many more times will you remember a certain afternoon of your childhood, an afternoon that is so deeply a part of your being that you can’t even conceive of your life without it? Perhaps four, or five times more? Perhaps not even that. How many more times will you watch the full moon rise? Perhaps twenty. And yet it all seems limitless …’

Have a look at www.deathclock.com (http://www.deathclock.com); it’s one of my favourite websites! You add various parameters about your life (age, weight, gender, whether you smoke) and it will calculate the date you are likely to die. A big, unstoppable clock begins counting down the remaining seconds of your life.

I have the date of my predicted death scheduled into my diary. Morbid, perhaps, but it takes deadlines to spur most of us into action, and that non-extendable deadline scares the hell out of me. I have so much I want to get done before 8 September 2050!

Life, they say, is what happens while you’re busy making plans. Time is ticking, life is short. These days everyone is busy. We’re racing time, always chasing time. Bragging about how busy we are is one of our era’s favourite things to do. But, as the pithy viral Tweet said, ‘We all have the same 24 hours that Beyoncé has.’ It’s up to us to carve out time to make bootylicious stuff happen. When I was younger I would simply think of a trip, then go and do it. Now that I’m older and busier it’s more often a case of making a chunk of time available and then coming up with a plan that fits into that time slot.

There is no simple solution. This book will not solve the lack-of-time conundrum. I’d be rich if it did. But it might get you excited enough to resolve to solve it yourself: to begin the conversations with the people in your life – your family, your boss, yourself – about how it might be possible to pause the racing rhythm of daily life for long enough to do something different and really memorable. After all, each hour that passes, each dreary commute, each bleary Monday morning – these are hours on the hamster wheel that you have spent and will never be able to recoup or spend again. So spend them wisely.

One of my favourite feelings on expeditions is how much time I have. I don’t have more time, of course, I’ve just freed it up to do stuff that feels important to me. I wake at dawn, the diary is empty and the day stretches long before me. I drink tea and watch the sun rise. All I need to do today is make some miles. And then I will sit again, weary but satisfied, in some place I have never been before, and watch the sun set. The days are not busy, but they are full and fulfilling. I cherish spending that time. At home my days feel short and hurried. Yet at the end of most of them I’ve accomplished nothing memorable. What a waste!

I hope that this book persuades you to find a way to find time to fill your days with what feels important and worthwhile to you, not with the stuff that conventional society deems you ought to be doing.

‘The sooner you begin to get into this mind-set, the sooner you will have that big juicy chunk of time inked into your diary and the adventure can begin’

The first task is to think carefully about how you use your time now, and how you might be able to make some time for adventure. This isn’t about stirring your porridge into your coffee, sleeping in your work suit or other handy tips like that. For a big adventure you’ll need to clear a swathe of time – weeks at least, months, maybe even a year or two.

Begin by asking yourself these questions. I know they are hard, but try to answer them as positively as you can rather than instantly dismissing them as impossible in the circumstances of your life.

What is the biggest chunk of time you might be able to carve out for an adventure? Is this long enough to do what you’d like to do? Squeeze another week on at either end. Is that long enough? How much time do you need?

When in the next year might you have time? Can you block off a non-negotiable chunk of time in your diary? It might be quite far in the future, but once it’s in the diary you can treat it as sacrosanct.

What are your time constraints? Why can’t you go away?

If it’s work, do they truly need you all the time? Could your colleagues cope without you for a while? How much loyalty and time do you owe them? Beware of misplaced loyalty. Talk to your boss about how you might be able to free up some time. Don’t just second-guess them by saying ‘it’ll never happen. They can’t do anything about it’. Have the conversation. Tell them how important this is to you, explain the benefits it will have for you and your work performance.

Imagine you were suddenly bedridden for a couple of months. Would the world cope without you? How would it manage? Could you, therefore, bugger off on an adventure for a couple of months without the world collapsing?

Could you take a sabbatical from work? Maybe you could work from the road. If you resigned, could you get your job back when you return? Could you quit, then seek a new job when you return? Or apply for a new job now but agree not to begin the position for a few months?

If you are too financially constrained to stop working, are there ways you can free yourself a little? Can you clear your credit card debts, downsize your house or rent it out, or even take out a loan? Richard Parks’ parents re-mortgaged their house to help him accomplish his expedition dream of climbing the Seven Summits and bagging both Poles. Extreme measures, perhaps, but it is important to reflect upon how important this experience is to you. You can get more money in life, but not more time.

On expeditions you often need to take bold, decisive decisions that will have a significant impact on your chances of success or staying alive. You have to be confident, clear-headed and brave enough to back yourself. The wilderness is a place for positive decisions, pushing forwards and making shit happen. The sooner you begin to get into this adventurer’s mind-set, the sooner you will have that big juicy chunk of time inked into your diary and the adventure can at last begin.

WISE WORDS FROM FELLOW ADVENTURERS

SEAN, INGRID AND KATE TOMLINSON

CYCLED THE LENGTH OF THE AMERICAS

Kate was eight: the perfect age – old enough to remember and benefit from her experiences, but not yet a reluctant stroppy teenager!

HANNAH ENGELKAMP

WALKED ROUND WALES WITH A DONKEY

Often I’d get people saying, ‘Oh, well, I’m glad you’re doing it now while you’re young, while you can’, and they’d be people in their fifties. Sometimes I’d just think, ‘Oh, for heaven’s sake, you’re just giving yourself an easy excuse.’

ROSIE SWALE-POPE

RAN AROUND THE WORLD IN HER SIXTIES.

You’re a long time dead, so you might as well get on and do it whilst you are alive!

JAMIE BOWLBY-WHITING

RAFTED DOWN THE DANUBE

It’s not the days in the office that we’ll reflect upon with nostalgia when we are old.

SARAH OUTEN

TRAVELLED ROUND THE NORTHERN HEMISPHERE BY HUMAN POWER

Treat it as you would any other project. Identify what the project is, break it down into bits and put a time frame on it, then suddenly it can happen. Monitor your progress as you go along and learn stuff on the way. I think so long as you’re flexible in that plan and willing to change and adapt, then it’s not rocket science.

COLIN WILLOX

BACKPACKED THROUGH EUROPE

People are often paralysed by fear at the difficulties of making an adventure happen (‘where will I keep my car?’). There is no perfect time to go. So tie up the loose ends you can in a reasonable time, and leave. It will be messy. You’ll screw up. There are no guarantees. Remember that this is what you want, it’s why you’re going. If you didn’t, you would stay home.

PAUL RAMSDEN

TWO-TIME WINNER OF THE PIOLETS D’OR AWARD

It’s really hard [to make the time]. I’m busy. It’s hard to find the time to get fit. The most important thing is that I get the dates in the diary maybe a year in advance. It’s then non-negotiable – if I get work offers or party invites I can then say ‘sorry, I’ll be in India’. It’s a bit brutal. There’s no compromise. It’s massively important to set those dates, otherwise it would be much easier just not to bother.

ROLF POTTS

CIRCLED THE GLOBE WITH NO LUGGAGE OR BAGS

I’d say that procrastinating about the journey is tied into the core fears that keep us from travelling. We keep thinking that there will be a better time, a time when we have more money or fewer obligations, or when the world feels safer and more open. In truth it doesn’t take as much money as most people think, obligations are something we can manage, and the world is far safer than you might think from just watching news headlines.

KIRSTIE PELLING

FOUNDER OF THE FAMILY ADVENTURE PROJECT

We made a decision to go freelance to make time to spend with the children. We started a website to record our adventures. If you voice your ambitions out loud you are more likely to achieve them.

MENNA PRITCHARD

CLIMBER

[Things like time], they’re not the reasons – they’re the excuses. Aren’t they? I really believe that if you want something enough then you will find the time, scrape together the money, and overcome your fears… But it’s all about priorities. And I know because I’m completely guilty of it myself. Ever since I became a mum, I have used it as an excuse. An excuse for not having the adventures my heart desires. There comes a time when we have to say to ourselves, ‘stop making excuses’. That if something means so much to us then it’s worth working towards, it’s worth fighting for – and, dammit, it’s worth the struggle. I don’t want life to be about the battles I never fought, the barriers I never overcame, the excuses I made.

HELEN LLOYD

LONG-DISTANCE JOURNEYS BY BIKE, HORSE, RIVER AND ON FOOT

My job in engineering, although it started as a career, is now a means to an end. It’s how I earn money to do the things I really want. I now work short-term contracts, live cheap, save up and plan another journey. For me, the mix of travel and engineering job satisfies all my needs, which I couldn’t get from just one.

GRANT RAWLINSON

HUMAN-POWERED EXPEDITIONS BEGINNING AND ENDING ON INTERESTING MOUNTAIN SUMMITS

I have a full-time job as a regional sales manager based in Singapore, travelling around Asia spending lots of time eating very nice meals with customers and staying in beautiful hotels. All of which I do not appreciate as much as a lukewarm cup of instant soup in a freezing snow cave. What is wrong with me?!

SCOTT PARAZYNSKI

ASTRONAUT AND MOUNTAINEER

[A lack of time] can probably be viewed as a cop-out on many occasions. A couple of times in my life, I’ve had the opportunity to take a leave of absence and do big things. Both my trips to Everest required some creative work-arounds at my day job, banking vacation time, initially. There are all sorts of really cool adventures that can be done on a shorter scale too.

ANT GODDARD

ROAD-TRIPPED ALL OVER THE USA

I have a young kid and a pregnant wife, so I’m in a good position to tackle the regular excuse given by people that ‘the timing’s not right for adventure now, I’m too busy, life’s too complicated.’ It’s an interesting thought because it’s kind of similar to the dilemma of if/when to have kids. The timing will never be perfect. If you wait for the perfect time you’ll miss out. Mostly everything you think you can’t leave will still be there when you get back, and travelling gives you a lot of time to think about those complications and put them in perspective. There are very few things that are honest blockers to just getting out and having an adventure, no matter how large or small the adventure is. You may feel like there are a lot of ‘what-ifs’ preventing you doing something adventurous, but the scariest one in my mind has always been ‘what if I never go? What if I stay here forever?’

ANDY MADELEY

CYCLED FROM LONDON TO SYDNEY

I realised that we only have this life to get everything done. That outweighed the fear of the unknown and gave me the momentum to bust out from the rut I found myself rolling down.

© Anthony Goddard/Linda Martini

(#u3689e309-d6a2-59bd-97c6-37b83ba5049b)

This much is true: expeditions have cost me time, money, relationships and messed with sensible life plans and pension prospects. They do not make my life easy. They are selfish. But I do not regret any of them. Indeed, I regret a few that I have not done. Adventures have enhanced my life and – this is important – they have ultimately enhanced most of those things I just mentioned, too, despite the initial pain, suffering, worry, compromise and hassle. In other words, my journeys have been worth it in the long run.

When I set off to cycle round the world I did not have a job or a mortgage. I had no monthly bills to pay. So long as I did not spend all the money I had saved, I was free to do whatever I wanted, wherever I wanted, for however long I wanted. My life was simple. I look back at that younger me with enormous envy!

If you are young, free and single, now is the time to head for the hills and go do something extraordinary. Life will never be so simple again, for you are not yet entangled in the mesh of commitments that grows over the years. Save up a bit of cash, whatever you can manage, and then go do something crazy. It will enhance your CV and teach you more than most expensive tuition fees will ever do. If a future employer isn’t more inclined to give you a job because of your experiences then they’re not the type you want to be working for anyway. Skip this chapter and go now! You have no excuse.

Money and time constraints make life complicated, but with planning you can free yourself from some of the muddle. Far more binding are our relationships: husbands, wives, boyfriends, girlfriends and families. If your other half is also itching for adventure, then things should be straightforward and exciting. You just need to start saving and start planning today. If you both save £1,000 and are happy to share a tent then you’ve got double the money and fewer outgoings.

If you’re in a relationship and both wish to travel but you have children, adventure planning becomes more complicated. But if your brood are young enough not to have an opinion, or even if they are able to express an opinion but you can still get away with saying ‘because I told you so’, then adventures are still quite achievable.

Ingrid, Sean and their 8-year-old daughter, Kate, cycled the length of the Americas. Ingrid and Sean were accomplished kayakers and trekkers before they began. This may not appear to benefit a transcontinental cycling journey. But it does in one important way: they knew what life in the wild and on the road was like, and they wanted more of it. They had the appetite. They had momentum and confidence. Theirs was not a standing start. Overcoming the inertia of normal life and generating momentum is very difficult. It can feel overwhelmingly daunting to say ‘we are going to change our life. We are going to go and do something big and bold. We will begin on this date. And right now we are going to begin to get ready by doing x, y and z.’ It’s a lot easier just to put the telly on and watch Bear Grylls.

Ingrid and Sean had to face the challenges of arranging for Kate to miss school, dealing with the concerns of well-meaning friends and family about taking a small girl on a big adventure, and managing their plans to make them compatible with helping an eight-year-old achieve a journey that most adults would be extremely jealous of!

There are challenges and potential difficulties in taking your family down an unconventional route like this, but what an education for Kate! What an achievement! What a glorious shared adventure for the whole family to remember and savour for the rest of their lives. That is worth the hassle.

Perhaps the most potentially difficult scenario is that you desperately wish to travel the world but your other half does not, and cannot be persuaded. If you’re lucky you’ll be given their blessing and the freedom to head out and do your own thing, reuniting afterwards in a lovely cocktail of happiness, rainbows and fluffy kittens.

But you may have a partner who – wonderful though they may be – does not want to join you on a trip, and does not want you to go either. This is where things get tricky. I’m not sure my dubious Agony Aunt skills will be much help, but I shall try my best!

You’ll need to mull over a few questions to help everything proceed as amicably and smoothly as possible. This is a kind, decent thing to do, of course. But it’s also your best option for being able to wangle another leave pass to go on an adventure again in the future!

Is it the time away, the money, the risk, the person you’ll be going away with, or the inconvenience of being left to juggle everything back home by themselves?

If it’s the length of time you will be away that is the problem, can you negotiate something that is acceptable for you both? Make the best of the time you’re granted and hatch a plan that is suitably short and sharp. This will rule out cycling round the world, but won’t eliminate everything.

After cycling round the world for four years, it took me a while to learn that duration is not the key measuring stick for a ‘good adventure’. There are many other ingredients to a great trip, and time is not critical to the recipe. It took me 45 days to row across the Atlantic, and a week to walk round the M25. Both were memorable experiences. I personally feel that six weeks is a good minimum amount of time to do something really significant and rewarding. Jason Lewis suggests six months – but then he did spend 13 years on his adventure! Meanwhile climbers can get up and down something special in a couple of weeks. Ultimately, it’s better to do something short than nothing at all.

If it’s not so much the absence of your lovely personality that is the problem but the absence of your useful role in sharing life’s daily chores, can you think of ways to equal up your balance sheet before or after the trip? Bear in mind that you will be perceived to be in debt on this account for the rest of your life, even long after you feel the debt has been settled! It’s the price you’ll have to pay.

If money is the stumbling block, work out between you how much money you can justify spending, then set that as your limit for the trip. You’ll still be able to do something great: doing stuff on a daft budget often makes it more fun anyway. Try pointing out how rich Bear Grylls has become from his adventures. Do not mention that almost nobody else has, though!

If it’s the risk of the adventure that’s causing friction, focus on an idea where the risk (or the perceived risk, at least) is lower. Perceived risk is an interesting concept; people often suggest to me that rowing across the Atlantic in a little boat was very dangerous. But so long as you don’t fall off the boat, it’s really not very dangerous at all, for you are in control of most of the risks. Keep the hatches closed, keep yourself tied to the boat: chances are you’ll be fine.

© Alastair Humphreys

You might know that what you are planning is pretty safe, but the person who loves you may not. A little thoughtful compromise in this department need not dampen the adventure. There is an element of risk in every adventure, of course, just as there is some risk in driving to work each day and massive risk in sitting in front of the TV for years until your heart packs in. The most epic adventures do entail danger. The most prolific adventurers are selfish. It’s up to you to decide where you and your trip are going to lie on the spectrum.

Your choice of expedition partner can be a cause of friction. This is usually for one of two reasons.

1. Your beloved thinks your expedition buddy is a Grade A lunatic who will get you into all sorts of scrapes.

2. Your partner is jealous of your expedition partner, either because you spend waaaaay too much time chatting to each other about your impending adventure and which multi-fuel stove you should buy, or because your expedition partner is worryingly attractive.

Do your best to point out that on an expedition people are smelly, don’t change their pants for weeks, and are too tired to want to do anything except sleep when you squeeze into that too-snug tent in an evening after watching the beautiful sunset slip behind the mountains, just the two of you out there, away from the world, nobody within a thousand miles of you… Be aware that whatever you say will be construed as protesting too much. Of course, you can always suggest to your partner that they can solve this particular problem by coming along with you instead!

Finally, failing that, you’re going to have to split up. You won’t have to endure Pizza Express Couples’ Evenings on Valentine’s Day ever again. You can do all the adventures that you dream of.

But don’t blame me when you’re out in the wild, freezing cold, deeply uncomfortable, starving, scared, stinking, lonely and you find yourself questioning your dramatic decision…

WISE WORDS FROM FELLOW ADVENTURERS

SCOTT PARAZYNSKI

ASTRONAUT AND MOUNTAINEER

There are huge personal rewards in exploration, but they aren’t always enjoyed by your family, and certainly they worry for you deeply when you go away to do these kinds of things. So there is a certain selfishness, I suppose, in exploration. But if it’s done for the right reasons, if there’s some social benefit, some educational benefit... I’ve always tried to have some kind of educational outreach with the things that I’ve done. There can be some broader good as well. There’s nothing wrong with having personal satisfaction with your exploration, either. And when we do go and explore, we come back better people as well. We come back reinvigorated, I think. I came back a better parent, more appreciative of the planet, a better steward of planet Earth.

SATU VÄNSKÄ-WESTGARTH

WHITEWATER KAYAKER TURNED LONG-DISTANCE CYCLIST

[When I was pregnant] the yearning for something, a proper adventure of sorts and the need to hold on to some pieces of the old ‘I used to have a life before the kids too’ kept burning. ‘Are you really going to be away from your kids that long?’ It was an inevitable question but one which I wasn’t prepared for when it first came my way. Not so many people wondered how my main worry, the biking, would go. They wondered how I would survive without the kids. Or the kids without me.

Well, we all survived. I felt more alive than I had for a while, away from the sleep-deprived life of a parent of young kids. I enjoyed being me. Not the mum of so-and-so. Just me. And most mornings I would join my family at the breakfast table at home, virtually, via Skype. ‘Mum goes biking today?’ my little girl would ask. Yes, Mum goes biking. And apparently she was going biking too. To be a good parent or a mum, I don’t have to be with the family 24-7 every day of the year.

The kids need security, love and an example of how life could be lived. The best example I can give them is the one of the true me, the one who dreams of adventures, and goes after her dreams. The one who comes back excited with stories to tell and then takes the whole family on microadventures.

JAMES CASTRISSION

KAYAKED THE TASMAN AND TREKKED TO THE SOUTH POLE AND BACK

I looked at the managers at work who were five years ahead of me, then the partners who were 10 or 15 years older than me, and I looked at the lives they were living and I thought about what was really important to me. I just couldn’t see myself living like that. Conformity has always freaked me out a little bit, so kayaking the Tasman was a way of identifying who I was and what I was capable of doing – and just seeing a bit of the world.

Even at the time, it was the hardest decision I’d ever had to make in my life. If I had to decide now, with a young family, I don’t know if I would have had that will.

I come from a Greek family and my mum and dad had invested so much in my education and had it all planned out for me, really. You go to school, you go to uni, get a good job... To turn my back on that was almost like a bit of a slap in the face for them. Not living up to their expectations, no one understood why I was doing it. That’s what made it so difficult.

SEAN, INGRID AND KATE TOMLINSON

FAMILY CYCLING EXPEDITION FROM ARCTIC CANADA TO PATAGONIA

Sean, our daughter Kate and I cycled from Arctic Canada to the southern tip of Chile on a single bike and a tandem pulling two trailers. We were always inspired by the idea of making a very long journey. We wanted arriving somewhere new and unknown to us every evening to become part of our daily lifestyle. We feared that if we left it a few more years Kate would not want to miss out on school and her social life. This has turned out to be one thing that we were dead right about. We are lucky to get her to ourselves for one day every other weekend now and I’m glad we made the most of her pre-teen years!’

© Alastair Humphreys

Kate offered this perspective on their adventure: ‘My parents took me away because they are crazy. They have been taking me off on adventures for as long as I can remember, although this was the longest.

‘Some of the toughest parts were also the best. The places where we had the hardest times are the moments we look back on with the fondest memories’

If I hadn’t wanted to do it, though, it wouldn’t have happened. I always get a say in the plans. I love looking back on the trip and I often think about it. It was just a way of life for two years. Some of the toughest parts of the trip were also the best parts. Like the places where we had the hardest times or felt scared are the moments we look back on with the fondest memories. I think the trip had a positive effect on my work. My Mum did schoolwork with me for about an hour every day and I had her all to myself. My Dad practised times tables with me on the bike and then asked me questions like how long it would take to get to somewhere depending on how fast we were going. As for subjects like geography and history, well, we didn’t need books because the real thing was right there in front of me. My advice to other parents if you want to travel with kids is try to do it when they are fairly young. I am 13 now and the idea of going away and leaving my friends for two years sounds much harder than back then. I think [the idea that children are not tough enough for a big adventure] is rubbish: I can tell you I was a lot tougher than my Mum and Dad!

CHRIS HERWIG

TRAVELLER AND PHOTOGRAPHER

With the arrival of our second child came the opportunity to take leave. A time for caring for our new bundle of joy, feeding him, changing his diapers and rocking him to sleep. But nowhere was it written that this could not also be a time for a bit of adventure. So we sublet our New York apartment and the four of us hit the vagabond road for a sixmonth, eleven-country round-the-world trip.

Over the six months our eleven pieces of luggage slimmed down to a large backpack and a carry-on as we slowly explored the wonders of Vietnam, Cambodia, Burma and New Zealand by train, boat, car, tuk-tuk, foot, bike, elephant and horse. We learned a great deal trying to overcome some of the challenges that came with travelling with two young kids, some of which were scary, some frustrating, but mostly fun. What to pack, where to go next, how to get there, how to make a three-year-old happy, how to keep all of us (especially the baby) safe while also having a bit of fun ourselves and proving the point that life does not have to change completely as soon as kids arrive.

KIRSTIE PELLING

6,000 MILES OF FAMILY CYCLING ACROSS THE GLOBE

An adventure is much more fun when you have kids along – in fact, in our experience they are the key to getting to know the world. They’re also often better at things than you are, as we recently found out in the Pyrenees when the kids left us way behind on the mountain.

MARK KALCH

PADDLING THE LONGEST RIVER ON EACH CONTINENT

Something like the Upper Nile and the Yangtze, which I’ll have to paddle, are two rivers that are ridiculously difficult. They have an element of danger. Decisions based on how this might affect my kids or my family will certainly have to be taken. But most of the time I am paddling in nice weather, eating as many chocolate bars as I want to, meeting really cool people and essentially just having a paddling holiday.

PAULA CONSTANT

WALKED FOR THREE YEARS FROM THE UK TO THE SAHARA

I was married when I left London. My husband and I left together. We walked the first year together. A month into the trip through the Sahara our marriage broke up. Gary left and I continued walking on my own. I don’t have a fixed opinion on whether one should do a trip with a romantic partner or not. I think it entirely depends upon the couple, the expedition, and everything. I think there are virtues to both. The first year, it meant the world to me to have a partner to walk with. And I’m not sure to this day whether or not I would have had the courage to leave on my own. Having said that, I was absolutely and utterly frustrated by the time a year had gone past. And, I would say, travel certainly heightens any trouble with a couple.

RIAAN MANSER

ROWED FROM AFRICA TO NEW YORK WITH HIS WIFE

When I look at the rowing now, I just think that [going solo] would be a step too far for me. On the topic of taking a friend with me: I think I romanticise the idea. I love the idea of taking a buddy, but that buddy would have to be a really good friend because I know what you have to go through. I’m actually glad that I took my wife, Vasti, because we did something special together. If I were to choose again, without a doubt I’d take my wife.

ANT GODDARD

DROVE AROUND THE USA WITH HIS YOUNG FAMILY

I’ve been able to work remotely while travelling, so some days I’ll have to sit in a park or coffee shop working while my wife and son get to enjoy the local sites, but work has been super-flexible and that’s definitely helped fund the trip.

GRANT ‘AXE’ RAWLINSON

HUMAN-POWERED EXPEDITIONS BEGINNING AND ENDING ON INTERESTING MOUNTAIN SUMMITS

I treated my wife even more like a princess than I normally do until she gave me permission to go on the trip!

MATT PRIOR

DROVE TO MONGOLIA IN A £150 CAR

Family-wise, my dad didn’t talk to me for a while. He thought I was being an idiot taking this risk when I had a good career [as a fighter pilot] laid out in front of me. I put this down to a generational thing: he’s used to it now and I always come back in one piece so it can’t be that bad!

© Alastair Humphreys

© Alastair Humphreys

SOLO OR WITH FRIENDS?

WISE WORDS FROM FELLOW ADVENTURERS

SEAN CONWAY

SWAM THE LENGTH OF BRITAIN, CYCLED ROUND THE WORLD

I think the benefits of travelling alone include… The freedom to change plans whenever you like and you get to live the adventure you want to live. If I had to choose, I prefer travelling alone because I often like to do long days, which isn’t for everyone.

SHIRINE TAYLOR

CYCLING ROUND THE WORLD

I think the benefits of travelling alone include…Learning more about yourself and gaining a sense of independence. When you are alone you realise that you can get through any situation. You are also able to truly figure out who you are and what you want when you are solely focused on yourself.

Whilst the advantages of going with someone else include…

It’s impossible to explain to an outsider how it feels to sleep in a slum, or to cycle up a two-day pass, so it’s nice to have someone alongside you who gets it.

You have someone to cuddle up with at night!

If I had to choose… That’s a hard one. I absolutely love travelling alone and will definitely be doing more of it throughout my life, but now that I have found ‘my person’ I wouldn’t give him up for the world. I think it’s important for everyone to travel alone at least once since it’s such an eye-opening, incredible experience.

© Alastair Humphreys

ANNA HUGHES

BOTH CYCLED AND SAILED 4,000 MILES AROUND THE COASTLINE OF GREAT BRITAIN

I think the benefits of travelling alone include…

People tend to offer help more if you are travelling alone.

Whilst the advantages of going with someone else include…

Sharing the views makes them more real, somehow. If I had to choose, I would go alone, because I am fiercely independent and want to do things my way! And the satisfaction of accomplishing something by yourself is wonderful.

HELEN LLOYD

ADVENTURES BY BIKE, HORSE, RIVER AND ON FOOT

The advantages of going with someone else include…

It’s safer to go places that would be difficult or more dangerous alone.

If I had to choose, I would go alone because of the freedom, but it’s still easy enough to find someone to do stuff with if I want to. So it’s the best of both worlds.

JAMIE MCDONALD

RAN 5,000 MILES ACROSS CANADA

I think the benefits of travelling alone include…Embracing the adventure, and everything around you more. You only have to focus on one person: you. Selfishly, that can be nice.

IAN PACKHAM

CIRCUMNAVIGATED AFRICA BY PUBLIC TRANSPORT

I think the benefits of travelling alone include…Gaining a much better, deeper insight into and interaction with locals and local life.

Whilst the advantages of going with someone else include…

Adopting new ideas and picking up new skills from that person. Sharing costs!

If I had to choose, I would go alone, simply for the ease of being able to go without any pre-planning.

DAVE CORNTHWAITE

SKATEBOARDED ACROSS AUSTRALIA

I think the benefits of travelling alone include…

Faster decision-making and less scope for quarrels or bother.

Whilst the advantages of going with someone else include…

They’re always going to be better at me than some/most of the things I’m capable of, which can make a difference to certain elements of a trip.

In the right team, two people can do the work of three (sometimes six can be less effective than one, though).

If I had to choose… I’d go alone. All things considered, I’ve enjoyed my solo trips better, and most of the unhappy memories I have from my journeys have been due to other people. I’ve done two trips with support teams. The first one, by skateboard, had three vans. I still don’t have a driver’s licence at the age of 34, but I bought my first three vehicles when I was 26! I don’t think I’m ever again going to do a thousand-mile expedition with a big team. It can be quite problematic. So I’m going to keep it small or solo from now on.

SARAH OUTEN

ROWED THE INDIAN OCEAN ALONE

I think the benefits of travelling alone include… You are in charge and you make it happen your own way, at your own pace.

You only have your own cabin farts to endure.

The beauty of solitude and peace is sublime.

Whilst the advantages of going with someone else include…

You do not have to make all the decisions, although compromise is required.

There’s someone else to help keep you safe, and having someone to focus on in times of need is a positive thing for me.

If I had to choose… Alone is your journey, in your style, and your pace and you can be totally open to the magic that will happen. Together can be magical, too. For me, it depends on the journey and goal and what’s needed to make it happen.

BEN SAUNDERS

SOLO TO THE NORTH POLE AND A 2-MAN RETURN JOURNEY TO THE SOUTH POLE

The hardest thing about solo expeditions – big, long ones – is the knowledge that no one else can ever, or will ever, know what it was like. In some ways, that’s very precious and very special, but in other ways, it’s frustrating when you try to explain the experience to others.

TOM ALLEN

LONG-DISTANCE CYCLIST AND FILM-MAKER

I think the benefits of travelling alone include…

Allowing your mind to unwind entirely from the utter lunacy of everyday life.

Whilst the advantages of going with someone else include… Having another person there to take photos of you looking heroic.

If I had to choose, I would go alone because an experience that is entirely your own will be a better teacher.

When we – I say ‘we’ because it was me and my best mate at the start – set off together it gave us the confidence to set off at all. That was definitely the biggest thing about planning it with a friend: we gave each other moral support, we enabled each other to get started. I can’t say if I would have done it if I’d been alone. I like to think that I would have done, because my life circumstances at the time were either to go travelling or suffer miserable, unfulfilling office jobs for the rest of my life.

But I did end up on my own as well and the experience couldn’t have been more different. Of all the things you could change about an experience, the difference between being alone and being with someone else is the biggest.

I think if someone’s too nervous to start something on their own, finding a friend to do it with will definitely help. I would just say be very careful about making sure that the friend has the same overall expectations for what the trip’s about, because it’s when people have differing expectations that things start getting difficult.

JASON LEWIS

FIRST HUMAN-POWERED CIRCUMNAVIGATION OF THE WORLD

Travelling alone is wonderful because you can do exactly what you want. If you want to travel or you want to ride your bike five miles and then stop and take the rest of the day off, you can. I’ve travelled alone for long periods, and I think I’ve come to the conclusion that I’m not very good on my own, I actually unbalance.

© Alastair Humphreys

I do prefer to be at least with one other person. Three is the ideal number, I think, because you get to share the experience. When you’re on your own, it can become quite morbid, but it’s a little too indulgent, I think. After about a month of being alone, you have no real way to appreciate, perhaps, what you’re seeing, what you’re experiencing, because you don’t have another mirror near to you to reflect some of what you may be taking for granted.

LEON MCCARRON

LONG-DISTANCE CYCLIST, WALKER, FILM-MAKER

I think the benefits of travelling alone include…

The vulnerability of a solo traveller often encourages more people to come and speak to you, while a pair or a group can look self-sufficient.

Whilst the advantages of going with someone else include…

Having a creative and decision-making sounding board, another perspective and opinion, and someone to see things you may be blind to.

If I had to choose, I would go with someone else because I like the company, and as someone who tries to film adventures, having a second person is invaluable logistically and creatively. I have no real desire to do very long trips on my own anymore. When I was young and wanted to prove myself (to myself and to the world) I needed to travel alone, but now I mostly find myself very dull.

© Alastair Humphreys

STEVE DEW-JONES

HITCH-HIKED THE AMERICAS

I think the benefits of travelling alone include: More space to think. Learning to be alone.

I find travelling solo quite lonely. Whenever I go somewhere new, I want to be able to share my thoughts with someone and to see if they feel the same way about the place. And I hate eating alone.

MATT PRIOR

ADVENTURER, FORMER FIGHTER PILOT

I think the benefits of travelling alone include:

Freedom to attach or detach yourself to or from groups without any ill-feeling. It’s easier to take risks.

Whilst the advantages of going with someone else include:

You don’t have to always introduce yourself and tell people the same story day in, day out: this gets old after a while.

If you’re on a road trip, it’s definitely worth going with a friend. Saying that, this can make or break your trip, so choose carefully. Doing a trip with someone else can create a very strong bond for life, but I have also known of best friends return and never speak again. There are people all over the place who are keen for randomness, so don’t think if you can’t find someone straightaway that you’re going to be lonely!

TIM MOSS

MOUNTAINEER, ADVENTURER, CYCLIST

I think the benefits of travelling alone include:

For me, travelling solo is a much more powerful experience. That sounds a bit melodramatic but there’s something about being on your own all the time, making every little decision by yourself and living through all these experiences without anyone around with whom you can share them.

Whilst the advantages of going with someone else include…

The highs and lows are mellower by virtue of being shared and, generally, I’d say it is easier and a lot more fun.

If I had to choose… I don’t think recommending one over the other is illuminating. If you want to test yourself, push yourself and have a deeper experience, I’d suggest going solo. If you’d rather enjoy yourself (assuming you have a good partner) and have your problems halved, go with someone else.

OLLY WHITTLE

CANOED DOWN THE MEKONG

I do most of my adventures alone and I think it’s actually more of a challenge to do them in a group, so that’s what I might plan next. Also, I think a pair is completely different from alone and a group. A pair may fall out big time, which I think is less likely in a three or more.

I think the benefits of travelling alone include:

It’s easier to actually get started.

No responsibilty for others’ safety (if you mess up, it’s only you that’s in trouble).

You don’t have to worry whether everyone is enjoying themselves (adventures are rarely pure fun).

It’s scarier, there’s a bigger sense of stretching yourself.

If I had to choose for my next adventure, I would go in a group because I’ve already done loads alone so it will give me new challenges. I probably wouldn’t choose a pair.

DOM GILL

CYCLED THE AMERICAS ON A TANDEM, PICKING UP PASSENGERS EN ROUTE