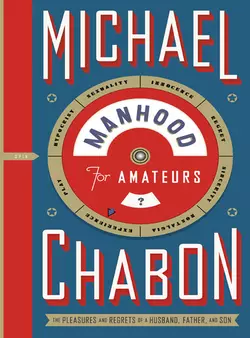

Manhood for Amateurs

Michael Chabon

Michael Chabon, author of ‘Wonder Boys’ and the Pulitzer Prize-wining ‘The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay’ , offers his first major work of non-fiction: an autobiographical narrative as inventive, beautiful and powerful as his novels.A shy manifesto; an impractical handbook; the true story of a fabulist; an entire life in parts and pieces: Manhood for Amateurs is the first sustained work of personal writing from Michael Chabon. In these insightful, provocative, slyly interlinked essays, one of our most brilliant and humane writers presents his autobiography and vision of life in the way so many of us experience our own: as a series of reflections, regrets and re-examinations, each sparked by an encounter, in the present, that holds some legacy of the past.What does it mean to be a man today? Chabon invokes and interprets and struggles to reinvent for us, with characteristic warmth and lyric wit, the personal and family history that haunts him even as it goes on being written every day. As a son, a husband and above all as a father of four young children, Chabon’s memories of childhood, of his parents’ marriage and divorce, of moments of painful adolescent comedy and giddy encounters with the popular art and literature of his own youth, are like a theme played – on different instruments, with a fresh tempo and in a new key – by the mad quartet of which he now finds himself co-conductor.At once dazzling, hilarious and moving, ‘Manhood for Amateurs’ is destined to become a classic.

MICHAEL CHABON

Manhood for Amateurs:The Pleasures and Regrets of aHusband, Father, and Son

Dedication (#ulink_0adabab0-405d-53c3-a475-c683e2d96dc6)

To Steve Chabon

Epigraph (#ulink_d0a834c2-49bd-525e-92ce-69d0fdbe66db)

Anything worth doing is worth doing badly.

– G. K. CHESTERTON

Contents

Cover (#u88827c50-d2c5-51d5-a965-232ec44c5ebc)

Title Page (#u941e6958-125e-5453-a9b5-b6295f4e72c5)

Dedication (#u84fd3052-d3db-5c1f-9714-5dc42d80446d)

Epigraph (#u806f394a-f2fe-53ee-be4f-1b63149144aa)

[ I ] SECRET HANDSHAKE (#uf49661df-dd4d-568d-a57f-fdbc58c8824f)

The Losers’ Club (#uf21bc30f-6571-5f47-85ef-3d51cc08b335)

[ II ] TECHNIQUES OF BETRAYAL (#u9882bd42-f8d7-512d-a5f3-b4385a394a37)

William and I (#u51d9ef24-8bc6-5d2f-ba3b-a3c3e72d33d9)

The Cut (#u5b28f736-fd6d-5c70-be50-254f7f82c7fa)

D.A.R.E. (#u771f2ea8-491a-5c51-80ba-2818b0df3a24)

The Memory Hole (#u28366355-2d27-5874-a805-970b975ebfb9)

The Binding of Isaac (#ufb01789e-f2cf-5df5-a2b7-646845337472)

[ III ] STRATEGIES FOR THE FOLDING OF TIME (#u5f645f64-7d28-50f2-bcf2-4a57ae3eaa6f)

To the Legoland Station (#u503c621a-442f-567f-8ce8-215ef25e7a8d)

The Wilderness of Childhood (#u5609da61-666f-5e73-9cd3-d296760af79f)

Hypocritical Theory (#ud1a169c8-6536-58a3-862e-b5f143707832)

The Splendors of Crap (#litres_trial_promo)

[ IV ] EXERCISES IN MASCULINE AFFECTION (#litres_trial_promo)

The Hand on My Shoulder (#litres_trial_promo)

The Story of Our Story (#litres_trial_promo)

The Ghost of Irene Adler (#litres_trial_promo)

The Heartbreak Kid (#litres_trial_promo)

A Gift (#litres_trial_promo)

[ V ] STYLES OF MANHOOD (#litres_trial_promo)

Faking It (#litres_trial_promo)

Art of Cake (#litres_trial_promo)

On Canseco (#litres_trial_promo)

I Feel Good About My Murse (#litres_trial_promo)

[ VI ] ELEMENTS OF FIRE (#litres_trial_promo)

Burning Women (#litres_trial_promo)

Verging (#litres_trial_promo)

Fever (#litres_trial_promo)

Looking for Trouble (#litres_trial_promo)

A Woman of Valor (#litres_trial_promo)

[ VII ] PATTERNS OF EARLY ENCHANTMENT (#litres_trial_promo)

Like, Cosmic (#litres_trial_promo)

Subterranean (#litres_trial_promo)

XO9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Sky and Telescope (#litres_trial_promo)

[ VIII ] STUDIES IN PINK AND BLUE (#litres_trial_promo)

Surefire Lines (#litres_trial_promo)

Cosmodemonic (#litres_trial_promo)

Boyland (#litres_trial_promo)

A Textbook Father (#litres_trial_promo)

[ IX ] TACTICS OF WONDER AND LOSS (#litres_trial_promo)

The Omega Glory (#litres_trial_promo)

Getting Out (#litres_trial_promo)

Radio Silence (#litres_trial_promo)

Normal Time (#litres_trial_promo)

Xmas (#litres_trial_promo)

The Amateur Family (#litres_trial_promo)

[ X ] CUE THE MICKEY KATZ (#litres_trial_promo)

Daughter of the Commandment (#litres_trial_promo)

Other Works (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

[ I ] SECRET HANDSHAKE (#ulink_ac75882f-c4ac-5f41-b6d1-b1e34ed54831)

The Losers’ Club (#ulink_cb4b55e2-5792-593a-b72b-56b1dc6bedd7)

I typed the inaugural newsletter of the Columbia Comic Book Club on my mother’s 1960 Smith Corona, modeling it on the monthly “Stan’s Soapbox” pages through which Stan Lee created and sustained the idea of Marvel Comics fandom in the sixties and early seventies. I wrote it in breathless homage, rich in exclamation points, to Lee’s prose style, that intoxicating smartass amalgam of Oscar Levant, Walter Winchell, Mad magazine, and thirty-year-old U.S. Army slang. Doing the typeset and layout with nothing but the carriage return (how old-fashioned that term sounds!), the tabulation key, and a gallon of Wite-Out, I divided my newsletter into columns and sidebars, filling each one with breezy accounts of the news, proceedings, and ongoing projects of the C.C.B.C. These included an announcement of the first meeting of the club. The meeting would be open to the public, with the price of admission covering enrollment.

For a fee of twenty-five dollars, my mother rented me a multipurpose room in the Wilde Lake Village Center, and I placed an advertisement in the local newspaper, the Columbia Flier. On the appointed Saturday, my mother drove me to the Village Center. She helped me set up a long conference table, surrounding it with a dozen and a half folding chairs. There were more tables ready if I needed them, but I didn’t kid myself. One would probably be enough. I had lettered a sign, and we taped it to the door. It read: COLUMBIA COMIC BOOK CLUB. MEMBERSHIP/ADMISSION $1.

Then my mother went off to run errands, leaving me alone in the big, bare, linoleum-tiled multipurpose room. Half the room was closed off by an accordion-fold door that might, should the need arise, be collapsed to give way to multitudes. I sat behind a stack of newsletters and an El Producto cash box, ready to preside over the fellowship I had called into being.

In its tiny way, this gesture of baseless optimism mirrored the feat of Stan Lee himself. In the early sixties, when “Stan’s Soapbox” began to apostrophize Marvel fandom, there was no such thing as Marvel fandom. Marvel was a failing company, crushed, strangled, and bullied in the marketplace by its giant rival, DC. Creating “The Fantastic Four” – the first “new” Marvel title – with Jack Kirby was a last-ditch effort by Lee, a mad flapping of the arms before the barrel sailed over the falls.

But in the pages of the Marvel comic books, Lee behaved from the start as if a vast, passionate readership awaited each issue that he and his key collaborators, Kirby and Steve Ditko, churned out. And in a fairly short period of time, this chutzpah – as in all those accounts of magical chutzpah so beloved by solitary boys like me – was rewarded. By pretending to have a vast network of fans, former fan Stanley Leiber found himself in possession of a vast network of fans. In conjuring, out of typewriter ribbon and folding chairs, the C.C.B.C., I hoped to accomplish a similar alchemy. By pretending to have friends, maybe I could invent some.

This is the point, to me, where art and fandom coincide. Every work of art is one half of a secret handshake, a challenge that seeks the password, a heliograph flashed from a tower window, an act of hopeless optimism in the service of bottomless longing. Every great record or novel or comic book convenes the first meeting of a fan club whose membership stands forever at one but which maintains chapters in every city – in every cranium – in the world. Art, like fandom, asserts the possibility of fellowship in a world built entirely from the materials of solitude. The novelist, the cartoonist, the songwriter, knows that the gesture is doomed from the beginning but makes it anyway, flashes his or her bit of mirror, not on the chance that the signal will be seen or understood but as if such a chance existed.

After I had been sitting at that big empty conference table for what felt like quite a long time, the door opened and a woman stuck her head in. I can still see her in my memory: her short blond hair parted in the center, her eyes metering the depth and density of the room, the tug of disappointment at the corners of her mouth.

“Oh,” she said, seeing how things were with the Columbia Comic Book Club.

A moment later, her son pushed past her into the room. He was a kid about my age, blond like his mother, skinny, maybe a little girlish. For a moment he stared at me as if I puzzled him. Then he gazed up at his mother. She put her hands on his shoulders.

“I have a newsletter,” I said at last, sliding the stack across the table.

The woman hesitated, then urged her son toward me, figuring or hoping, I suppose, that something could be salvaged, some kind of club business transacted. But the boy pushed back. That multipurpose room was not anywhere he wanted to be. God knows what kind of Araby he had erected, what fabulous tents he had pitched, in his own imagination of the event. A wordless argument followed, conducted by the bones of his shoulders and the fingers of her hands. At last she gave in to the force of his disappointment or to the barrage of failure rays that were pouring from the kid across the room.

“One dollar,” she said seriously, considering the sign I had taped to the door with the same kind of black electrician’s tape that was holding my eyeglasses together. “I think that might be a little too much for us.”

I don’t remember what kind of shape I was in when my own mother returned, or how she comforted me. I was a stoical kid, even an inexpressive one, given to elaborate displays of shrugging things off. In looking back at that day, I see now how much the brief existence of the C.C.B.C. had to do with mothers and sons, what a huge, even overwhelming maternal task is implied by that worn-out word encouragement. In spite of whatever consolation my mother may have offered, that was the moment when I began to think of myself as a failure. It’s a habit I never lost. Anyone who has ever received a bad review knows how it outlasts, by decades, the memory of a favorable word. In my heart, to this day, I am always sitting at a big table in a roomful of chairs, behind a pile of errors, lies, and exclamation points, watching an empty doorway. My story and my stories are all, in one way or another, the same, tales of solitude and the grand pursuit of connection, of success and the inevitability of defeat.

Though I derive a sense of strength and confidence from writing and from my life as a husband and father, those pursuits are notoriously subject to endless setbacks and the steady exposure of shortcoming, weakness, and insufficiency – in particular in the raising of children. A father is a man who fails every day. Sometimes things work out: Your flashed message is received and read, your song is rerecorded by another band and goes straight to No. 1, your son blesses the memory of the day you helped him arrange the empty chairs of his foredoomed dream, your act of last-ditch desperation sends your comic-book company to the top of the industry. Success, however, does nothing to diminish the knowledge that failure stalks everything you do. But you always knew that. Nobody gets past the age of ten without that knowledge. Welcome to the club.

[ II ] TECHNIQUES OF BETRAYAL (#ulink_881c2976-85f9-5bf4-8157-5182ce2d815b)

William and I (#ulink_88dd1668-d39a-5c5a-9778-af299e22514a)

The handy thing about being a father is that the historic standard is so pitifully low. One day a few years back I took my youngest son to the market around the corner from our house in Berkeley, California, a town where, in my estimation, fathers generally do a passable job, with some fathers having been known to go a little overboard. I was holding my twenty-month-old in one arm and unloading the shopping cart onto the checkout counter with the other. I don’t remember what I was thinking about at the time, but it is as likely to have been the original 1979 jingle for Honey Nut Cheerios or nothing at all as it was the needs, demands, or ineffable wonder of my son. I wasn’t quite sure why the woman in line behind us – when I became aware of her – kept beaming so fondly in our direction. She had on rainbow leggings, and I thought she might be a little bit crazy and therefore fond of everyone.

“You are such a good dad,” she said finally. “I can tell.”

I looked at my son. He was chewing on the paper coating of a wire twist tie. A choking hazard, without a doubt; the wire could have pierced his lip or tongue. His hairstyle tended to the cartoonier pole of the Woodstock-Einstein continuum. His face was probably a tad on the smudgy side. Dirty, even. One might have been tempted to employ the word crust.

“Oh, this isn’t my child,” I told her. “I found him in the back.”

Actually, I thanked her. I went off with my boy in one arm and a bag of groceries in the other, and when we got home I put a plastic bowl filled with Honey Nut Cheerios in front of him and checked my e-mail. I was a really good dad.

I don’t know what a woman needs to do to impel a perfect stranger to inform her in the grocery store that she is a really good mom. Perhaps perform an emergency tracheotomy with a Bic pen on her eldest child while simultaneously nursing her infant and buying two weeks’ worth of healthy but appealing break-time snacks for the entire cast of Lion King, Jr. In a grocery store, no mother is good or bad; she is just a mother, shopping for her family. If she wipes her kid’s nose or tear-stained cheeks, if she holds her kid tight, entertains her kid’s nonsensical claims, buys her kid the organic non-GMO whole-grain version of Honey Nut Cheerios, it adds no useful data to our assessment of her. Such an act is statistically insignificant. Good mothering is not measurable in a discrete instant, in an hour spent rubbing a baby’s gassy belly, in the braiding of a tangled mass of morning hair. Good mothering is a long-term pattern, a lifelong trend of behaviors most of which go unobserved at the time by anyone, least of all the mother herself. We do not judge mothers by snapshots but by years of images painstakingly accumulated from the orbiting satellite of memory. Once a year, maybe, and on certain fatal birthdays, and at our weddings or her funeral, we might collate all the available data, analyze it, and offer our irrefutable judgment: good mother.

In the intervals – just ask my wife – all mothers are (in their own view) bad. Because the paradoxical thing, or one of the paradoxical things, about the low standard to which fathers are held (with the concomitant minimal effort required to exceed the standard and win the sobriquet of “good dad”) is that your basic garden-variety mother, not only working hard at her own end of the child-rearing enterprise (not to mention at her actual job) but so often taxed with the slack from the paternal side of things, tends in my experience to see her career as one of perennial insufficiency and self-doubt. This is partly because mothers are attuned, in a way that most fathers have a hard time managing, to the specter of calamity that haunts their children. Fathers are popularly supposed to serve as protectors of their children, but in fact men lack the capacity for identifying danger except in the most narrow spectrum of the band. It is women – mothers – whose organs of anxiety can detect the vast invisible flow of peril through which their children are obliged daily to make their way. The father on a camping trip who manages to beat a rattlesnake to death with a can of Dinty Moore in a tube sock may rest for decades on the ensuing laurels yet somehow snore peacefully every night beside his sleepless wife, even though he knows perfectly well that the Polly Pocket toys may be tainted with lead-based paint, and the Rite-Aid was out of test kits, and somebody had better go order them online, overnight delivery, even though it is four in the morning. It is in part the monumental open-endedness of the job, with its infinite number of infinitely small pieces, that routinely leads mothers to see themselves as inadequate, therefore making the task of recognizing their goodness, at any given moment, so hard.

I know there’s a double standard at work; I suppose if I’m honest, I would have to acknowledge that in my worst moments, I’m grateful for it, for the easy credit that people – mothers, for God’s sake – are willing to extend to me for doing very little at all. It’s like pulling into a parking space with a nickel in your pocket to find that somebody left you an hour’s worth of quarters in the meter. This double standard has been in place for a long time now, though over the past few decades a handful of items – generally having to do with cooking and caring for babies – have been added to the list of minimum expectations for a good father. My father, more or less like all the men of his era, class, and cultural background, went for a certain amount of spasmodically enthusiastic fathering, parachuting in from time to time with some new pursuit or project, engaging like an overweening superpower in a program of parental nation-building in the far-off land of his children before losing interest or running out of emotional capital and leaving us once more to the regime of our mother, a kind of ancient, all-pervasive folkway, a source of attention and control and structure so reliable as to be imperceptible, like the air. My father educated me in appreciating the things he appreciated, and in ridiculing those he found laughable, and in disbelieving the things he found dubious. When I was a small boy, tractable and respectful and preternaturally adult, with my big black glasses and careful phraseology, he would take me on house calls and at-home insurance physicals along with his stethoscope and Taylor hammer. When he was done being a father for the time being, he would leave me in my corner of his life, tucked into the black bag of his affections. At night sometimes, if he made it home from the hospital, he would come in and lean down and brush my soft cheek with his scratchy one.

If the lady in the rainbow tights had seen us walking down a street in Phoenix, Arizona, in 1966, with me swinging my plastic doctor bag full of candy pills and deneedled hypos and trying to match my stride to his, she probably would have told him that he was a good dad, too. And she would not have been saying very much less or more than she was saying to me.

My father, born in the gray-and-silver Movietone year of 1938, was part of the generation of Americans who, in their twenties and thirties, approached the concepts of intimacy, of authenticity and open emotion, with a certain tentative abruptness, like people used to automatic transmission learning how to drive a stick shift. They wanted intimacy, but they were not sure how far they could trust it to take them. My father didn’t hug me a lot or kiss me. I don’t remember holding his hand past the age of three or four. When I got older and took an interest in the art of becoming a grown-up, it proved hard to find other, nonphysical kinds of intimacy with him. He didn’t like to share his anxieties about his work, relationships, or life, rarely took me into his confidence, never dared to admit the deepest intimacy of all – that he didn’t know what the hell he was doing.

In 1974 I saw a musical cartoon called “William’s Doll.” It was a segment in that echt-seventies, ungrammatically titled children’s television special created by Marlo Thomas, Free to Be You and Me. The segment, based on a book by Charlotte Zolotow, was about a boy who begs his bemused parents to buy him a baby doll, a request to which they are nonplussed if not, in the case of William’s father, outright hostile. William is mocked, scolded, and bullied for his desire, and his parents try to bribe him out of it. But William persists, and in the end his wise grandmother overrules his father and buys him a doll.

Even as a boy of ten, I could feel the radical nature of the mode of being a father that “William’s Doll” was holding out to me:

William wants a doll

So that when he has a baby someday

He’ll learn how to dress it

Put diapers on double

And gently caress it

To bring up a bubble

And care for his baby

Like every good father should learn to do.

I was moved by the sight of the animated William reveling, grooving, in the presence of the baby doll that his grandmother placed in his waiting arms. There was a promise in the song and the sight of him of a different way of being a father, a physical, quiet, tender, and quotidian way free of projects and agendas, and there was a suggestion that this way was something not merely possible or commendable but long-desired. Something was missing from William’s life before his grandmother stepped in and bought him a doll, and by implication, something was missing from the life of William’s father, and of my father, and of all the other men who were not allowed to play with dolls. Every time I listened to the song on the record album, I felt the lack in myself and in my father.

My dad did what was expected of him, but like most men of the time, he didn’t do very much apart from the traditional winning of bread. He didn’t take me to get my hair cut or my teeth cleaned; he didn’t make the appointments. He didn’t shop for my clothes. He didn’t make my breakfast, lunch, or dinner. My mother did all of those things, and nobody ever told her when she did them that it made her a good mother.

The fact of the matter is that – and fuck the woman in the rainbow tights for her compliment – there’s nothing I work harder at than being a good father, unless it’s being a good husband, which doesn’t come any easier but tends not to get remarked on when I’m standing in line at the supermarket. I cook and clean, do the dishes, get the kids to their appointments, etc. Many times over, I have lived entire days whose only leitmotifs were the vomitus and excrement of my offspring and whose only plot was the removal and disposal thereof. I have made their Halloween costumes and baked their birthday cakes and prepared a dozen trays of my mother-in-law’s garlic chicken wings for class potlucks because last names starting with A – F had to bring the hors d’oeuvres. In other words, I define being a good father in precisely the same terms that we ought to define being a good mother – doing my part to handle and stay on top of the endless parade of piddly shit. And like good mothers all around the world, I fail every day in my ambition to do the work, to make it count, to think ahead and hang in there through the tedium and really see, really feel, all the pitfalls that threaten my children, rattlesnakes included. How could I not fail when I can check out any time I want to and know that my wife will still be there making those dentist appointments and ensuring that there’s a wrapped, age-appropriate birthday present for next Saturday’s pool party? All I need to do is hold my kid in the checkout line – all I need to do is stick around – and the world will crown me and favor me with smiles.

So, all right, it isn’t fair. But the truth is that I don’t want to be a good father out of egalitarian feminist principles. Those principles – though I cherish them – are only the means to an end for me.

The daily work you put into rearing your children is a kind of intimacy, tedious and invisible as mothering itself. There is another kind of intimacy in the conversations you may have with your children as they grow older, in which you confess to failings, reveal anxieties, share your bouts of creative struggle, regret, frustration. There is intimacy in your quarrels, your negotiations and running jokes. But above all, there is intimacy in your contact with their bodies, with their shit and piss, sweat and vomit, with their stubbled kneecaps and dimpled knuckles, with the rips in their underpants as you fold them, with their hair against your lips as you kiss the tops of their heads, with the bones of their shoulders and with the horror of their breath in the morning as they pursue the ancient art of forgetting to brush. Lucky me that I should be permitted the luxury of choosing to find the intimacy inherent in this work that is thrust upon so many women. Lucky me.

The Cut (#ulink_236bede9-af5e-57ea-b90b-ca43146fd13d)

If you are a Jew, eight days after your son is born, you hand him to a man with a scalpel, and the man uses his fine instrument to cut off a small piece of your new baby. It is for this reason, though you will have to take my word on the matter, that my penis has no prepuce, or foreskin: My parents voluntarily had it sliced off by a little old guy with a sharp blade when I was eight days old. The same procedure was performed at the same age on my father, and on my grandfathers, all of whom were in attendance that afternoon, and on their fathers and grandfathers, stretching back to the time when knives were shards of obsidian or flint. The stated reason for this minutely savage custom is that God – the God of Abraham – commanded it.

That is not an argument that ought to hold a lot of water with me. I have confused ideas of deity, heavily influenced by mind-altering years of reading science fiction, that do not often trouble me, but one thing I know for certain, and have known since the age of five or six, is that I really can’t stand the God of Abraham. In fact, I consider Him to constitute the pattern to which every true asshole I have ever known in my life has pretty well conformed. In His infinite capacity to engineer and experience disappointment, in His arbitrary and capricious cruelty, and in the evident pleasure He derives from the exercise thereof, there is probably a sharp insight into the nature of fathers generally, since at one time or another, if not on a daily basis, each of us fathers is the biggest asshole in the world. Or else the God of Abraham is a metaphor, crude but effective, for the caprice, brutality, and disappointment of life itself. I don’t know. In any case, nothing having to do with this particular version of God and His supposed Commandments could ever satisfactorily explain my willingness to subject my sons, of which I have two fine examples, to mutilation: the only honest name for this raw act that my wife and I have twice invited men with knives to come into our house and perform, in the presence of all our friends and family, with a nice buffet and a Weekend Cake from Just Desserts.

“Why are we doing this again?” my wife asked me, not for the first time, on the night of the seventh day of our second son’s life.

We were in bed, sitting up against the headboard, semi-comatose, dazzled by sleeplessness in a way that felt shared and almost pleasurable. The baby was at her breast, working his jaw, the nipple impossibly huge in his astonished little mouth. I leaned my shoulder against my wife’s, and she laid her head against my cheek, and together our bodies formed a kind of cupped palm around the baby in her arms. The lamp clipped to the headboard enclosed us in a circle of soft light. I doubt that any rational observer could have inferred from that intimate huddle, from the shelter we had formed of ourselves, the date we had made for the baby and his foreskin at one o’clock the following afternoon.

“I guess,” she said, attempting to answer her own question, “he ought to match his big brother.”

“I guess,” I said, recognizing this as a variant of a common justification advanced by Jews inclined, in most other respects, to disregard the Commandments of the God of Abraham: that it would somehow disturb or gravely puzzle a child to contemplate the difference in appearance between his own hooded penis and his father’s peeled one. Possibly it might hang him up about penises in general. In turn this might lead, via unspecified, possibly mythical, psychological processes, to some kind of sexual dysfunction, oedipal collapse, Kafkaesque problems with authority.… That part of the argument tended to get left to the imagination. It was usually enough to intone the reasonable principle that a son ought genitally to match his father in order to evoke a cognizant nod of the head in the listener – a spouse, a gentile friend, a gentile spouse. I knew this matching-penises argument was a favorite among interfaith couples, frequently advanced by the non-Jewish partner as she attempted to get her mind around the idea of letting some nut with a scalpel come after her baby’s little thing.

“But who knows?” I continued. “None of their other parts have to match. They could have different eye color, different hair, different noses, differently shaped heads. One of them could have a fissured tongue or a rudimentary third nipple.” I have a rudimentary third nipple, which was why this particular example occurred to me. “What’s the big deal about the penis? By the time this guy here gets old enough that he starts making a critical study of penises, he probably won’t be seeing his brother’s very often.”

“Yeah,” she said, letting the argument flutter to the ground like a losing lottery ticket.

We had been through all of the standard arguments – hygiene, cancer prevention, psychological fitness, the Zero Mostel tradition – the first time around, with our oldest son, and found that they are all debatable at best, while there is plenty of convincing evidence that sexual pleasure is considerably diminished by the absence of a foreskin. But I never know how to think about that one. It is like in A Princess of Mars, in which we are informed that on the red planet Barsoom they have nine colors in their spectrum and not seven; I have tried and failed many times to imagine those extra Barsoomian colors.

“What?” my wife asked, sensing my abstraction from the matter at hand.

“I was thinking about the Mars books of Edgar Rice Burroughs,” I said glumly.

“Do they feature ritual genital mutilation?”

“Not that I recall.”

The baby popped off the breast, and sighed, and considered one of the anemone wisps of drifting smoke, like the aftermath of a bursting skyrocket, that I imagined his thoughts to resemble. At seven days he gave evidence of a melancholy or even mournful nature. He sighed again, and so I sighed, thinking that we were about to confirm, in the worst possible way, all the lugubrious ideas about the world that he already seemed to have formed. Then he burrowed back in for another go at his mother.

“If it was a girl,” my wife said, “we would never.”

“Never.”

We had been through this, all of this, before. Every time some brave doctor or grown victim spoke out against the ritual mutilation of girls’ labias in certain subcultures, we were duly outraged.

“It’s not one bit less barbaric than what they do over there,” my wife said. “Not one.”

“Agreed.”

“It’s madness. The more I think about it, the more insane it seems.”

I said I thought that was probably true of everything our religion expected us to do, from burying a pot in the ground because one day a meatball accidentally rolled inside of it, to replacing the hair you had shaved off, out of modesty, with a fabulous-looking five-thousand-dollar wig. In fact, I said, most human social behavior probably fit the formula she had just proposed – for example, neckties. But my observation failed to impress or even, it seemed, to register with my wife. She was gazing down at our little boy with the eyes of a betrayer, filled with pity and tears.

“You have to at least promise me,” she said, “that it’s not going to hurt him.”

As with the first time, we had shopped around the mohel market, looking for a guy who used, or would permit us to use, an anesthetic cream. Traditionally, the only painkiller was a drop of sweet wine introduced between the lips on the wine-soaked tip of a cloth, and a lot of mohelim stuck to that way of doing things. Some of them would suggest giving the boy Tylenol an hour beforehand. And then there were those who prescribed a cream such as Emla. The mohel who was coming tomorrow had given us complicated instructions that involved filling a bottle nipple with the Emla well before the procedure, then fitting it right over the penis, having first enlarged the hole in the tip of the nipple to permit the flow of urine. It was reassuring to think of the entire organ being immersed, steeped in numbing unguent, for hours beforehand. But even the absence of pain, if we could assure it, did not really detract from the fundamental brutality of the business.

“It’s not going to hurt,” I told her, though of course, having never immersed my entire penis in anesthetic cream and then subjected it to minor surgery, I had no idea whether it was going to hurt him or not. That was one of the skills you learned as a father fairly early on, and it had roots as ancient as whatever words Abraham had crafted to lure his son Isaac up that mountainside to the high place where he would bare his beloved child’s breast to the heavens, as he had been commanded to do by the almighty asshole or by the god-shaped madness whose voice was rolling like thunder through his brain. It was not the making of a covenant that the rite called Brit Milah commemorated, but the betrayal of one. Because you promised your children, simply by virtue of having them, and thereafter a hundred times a day, that you would shield them, always and with all your might, from harm, from madness, from men with their knives and their bloody ideas. I supposed it was never too soon for them to start learning what a liar you were.

I reached down and stroked the baby’s cheek.

“It’s not going to hurt,” I promised him, and he looked up at me, his gaze solemn and melancholy, without the slightest idea of what lay in store for him in this world but ready – born ready – to believe me.

D.A.R.E. (#ulink_07738d74-b1c4-5593-8905-369d701578e6)

One night when she was thirteen, my older daughter opened the discussion at dinner with something that had apparently been troubling her: a problem in the interpretation of rock lyrics. Since she saw the film Across the Universe, her interest in the Beatles had intensified, and lately, I had been fielding many such interpretative queries in my capacity as Senior Fellow in Beatle Studies – deciding whether or not, at the end of “Norwegian Wood,” the singer burns down the girl’s house because she makes him sleep in her bathtub; and working hard not to have to explain to my older son, not quite eleven at the time, what delectable treat was signified in Liverpool slang by the phrase “fish and finger pie.” (So tasty that the singer orders four of them!)

“Dad,” my daughter said, “when he goes ‘I get high with a little help from my friends,’ is he talking about getting high high? Or is he just saying that being around his friends makes him feel really, really, like, happy?”

The ten-year-old was at the kitchen counter pouring himself a glass of milk, but in the instant that preceded my reply, without even looking his way, I could feel him training his detectors on me, his array of receiving dishes all swiveling in my direction. Every time somebody fired one up in a movie, the kid looked simultaneously troubled and intrigued by the sight. He is a clear thinker who likes his questions settled, and I had seen him wrestling for some time with the mixed messages our culture puts out about the pleasures and disasters of drug and alcohol use.

“High high,” I said.

My daughter’s cheeks colored as I met her gaze, in embarrassment and in pleasure, too, I thought, as though her insight had been confirmed in a way that gratified her sense of her own sophistication.

I could remember this moment in my own life, when I was exactly her age and had yet to encounter actual marijuana: the sudden consciousness, a flower of preteen lore and hermeneutics, that the lyrics to Beatles songs were salted with and in some cases constructed entirely from sly and overt references to drug use. Not just “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” or “She Said She Said,” which supposedly re-creates an acid-powered conversation between John Lennon and Peter Fonda, but less obvious numbers like “Girl,” on Rubber Soul, which was, it was claimed, a protracted allegory of marijuana use, with the hissed sighs that punctuate its choruses meant to represent the sound of someone taking a big, long toke. The line Roll up for the mystery tour, I had been told, referred to the rolling of joints.

So I recognized that flush in my daughter’s cheeks. She was a good girl, and I had once been a good boy, and I remembered that simultaneous sense of disapproval and fascination with the lyrical misbehavior of the boys from Liverpool. Thirteen is the age at which you begin to become fully aware of hypocrisy, contradiction, ambiguity, coded messages, subtexts; it is the age, therefore, at which you must begin to attempt to sort things out for yourself, to grab hold, if you can, of any shining thread in the dizzying labyrinth. And there, for me as for my children three decades later, were the Beatles, passing with astonishing and even brutal swiftness from the self-censoring radio-ready plaintext of “Love Me Do” and “I Wanna Hold Your Hand” to the encrypted thickets of songs like “I Am the Walrus” or “Happiness Is a Warm Gun”: the eight-year chronicle in music of the band’s attempt to sort things out for themselves as they came of age, the oeuvre itself a dazzling mass of puzzles and contradictions to be sorted.

“Dad, what does it feel like?” my son said, returning to the table with his glass of milk.

“Getting high?” I said. This time there was no hesitation. I had thought about this conversation, imagined it, planned for it, enough that I ought to have been ready; but even though I had spoken often with my wife (who for many years taught a class at Boalt Hall, UC Berkeley’s law school, called “Legal and Social Implications of the War on Drugs”) about our parental approach to talking about drug use, now that the moment was actually upon me (and she just happened to be out of town), I found that I was not ready at all. I was caught completely off guard. And maybe that’s why I came right out with the truth.

“It feels pretty good,” I said. “It makes you feel like you’re really, uh, being with the people you’re with. It makes you insanely hungry and thirsty. It makes you paranoid. It makes your heart race. It makes you sluggish. It makes you think things are really funny that might not actually be that funny at all.”

“Like dead bodies?” my younger daughter suggested brightly. She was only six years old, but it looked like she was going to be in on this discussion, too.

“Uh, yeah, well, no, more like a bad Elvis movie,” I said. “It makes you have thoughts that seem really, really deep and profound, and then the next day when you remember them, they seem totally lame.”

“I wrote a poem in a dream I had,” the thirteen-year-old said. “The same thing happened with that.”

“Wait,” the ten-year-old said. “Wait. You mean – have you actually smoked marijuana?”

Here it was, the big moment, the one we had all been waiting for, dreading, preparing for years in advance.

“Duh!” the thirteen-year-old informed her brother, doubling down on her proven-worldly views of the role of drugs in modern culture. “Like, every adult over a certain age has done it.”

“Well, not every adult,” I said. “But yes. I have.”

“How many times?” my son said, eyes wide.

So far, even blindsided as I had been by the abrupt onset of this conversation, I hadn’t violated the guiding principle my wife and I had decided on for its eventual proper conduct: I had been honest. But now I had a moment’s pause before replying, unwilling to pronounce those two simple words: one million.

The first person I ever saw smoking pot was my mother, sometime around 1977 or so, sitting in the front seat of her friend Kathy’s car, passing a little metal pipe back and forth before we went in to see a movie at the Westview in Catonsville, Maryland. I have a dim sense that at fourteen I neither disapproved of nor felt any surprise at this behavior, leading me to conclude that my mother already must have told me, prepared me with the information, that she was “experimenting” with pot (because that was all it ever amounted to for her – a brief reagent test conducted within the beaker of her new status as a single woman in the great wild laboratory of the 1970s). If I was shocked by the idea of my mother breaking the law, that shock must have been mitigated by the casualness, and by the lack of shame or embarrassment with which my mother, an otherwise upright, sober, and law-abiding taxpayer, went about it. It appeared to be no big deal for a couple of grown women to smoke a bowl: an innocent, everyday sign of the times. Nevertheless, smoking marijuana remained for years afterward nothing I had any interest in trying myself, not so much because I feared its effects or even because it was against the law but simply because I was a good boy, and as such I looked down my nose with a cosmic, Galactus-sized censoriousness at the kids I knew – stoners, burnouts – who smoked it. I would not have minded breaking the law or getting high, but I could not abide the thought of being bad.

I clung to my increasingly cumbersome and ineffectual goodness, fighting a series of rearguard actions against the increasing presence in my life of rock and roll and sex, until, like the personnel of the U.S. embassy in Saigon leaping to the helicopters, I abandoned it entirely, at once. Early in October of my first term at Carnegie Mellon University, I was taught the rudiments of bong-handling by a team of experts. I lay down on the floor of a dorm room in Mudge Hall, under the light of a single red bulb, and swam through layers of warmth and well-being while an apparently infinite, starry, velvet-bright quantity of wonder was ladled into my ears by Jeff Beck, Jan Hammer and his spacefaring Group.

That was 1980. I smoked marijuana (with odd European forays into the mysteries of hashish) over the course of the next twenty years, never every day, mostly on weekends or when some came around, but at times with all the fierce passion of a true hobbyist. The price went up, and the quality improved so acutely that the nature of the high began to alter without quite changing, like a television picture increasing the resolution of its image. My level of dope-smoking peaked, becoming nearly habitual just after the breakup of my first marriage in 1990, and began to dwindle thereafter as the elevated concentrations of THC (or something) took a toll and I found that getting high often left me feeling apprehensive, hypercritical of myself, and prone to an unwelcome awareness of my life as nothing but a pile of botched and unfinished tasks. Over the course of these pot years I graduated from college, got a master’s degree, wrote a number of novels, paid my bills and my taxes, etc. I was never arrested, never got into any kind of trouble, never broke anything that could not be repaired. Mostly it had been fun, sometimes hugely; sometimes not at all. Marijuana could intensify the sunshine of a perfect summer day, but it could also deepen the gloom of a wintry afternoon; it had bred false camaraderies and drawn my attention to deep flaws and fault lines when what mattered – what matters so often in the course of everyday human life – were the surfaces and the joins.

Be honest, my wife and I had agreed.

“I have smoked it a number of times,” I told my son. “But I don’t do it anymore.”

This was true. Without ceremony or regret, I smoked marijuana for the last time in 2005 – having not smoked any for at least a year before that – when I found myself, stoned out of my brain and very much not following the plot of Stephen Chow’s God of Cookery, unexpectedly called upon to engage in some urgent full-on parenting: There was an abortive sleepover and a necessary stretch of late-night driving to be done. Though I somehow managed to pull it off, gripping the wheel, heart pounding, the world beyond the windshield as trackless and unfathomable as any Jeff Beck guitar solo, I spent the next hour fighting off the knowledge that I was not up to the task, and I vowed that I would never risk putting my children or myself in that position again. On some fundamental level, I was no longer willing to endure, or capable of enjoying, that kind of fun.

“Why did you stop?” those children wanted to know. “Because it’s really illegal?”

“Well, it is really illegal,” I agreed. “In some ways, a lot more illegal than it used to be when I was younger. But that’s not really it. It has to do with, well, with being ready, you know. It’s just not something I’m ready to do anymore. And it’s not something you guys are ready to do, either. Right?”

“Right,” they said at once, with all the firmness and certainty I would have mustered myself in those years before I sailed off into the red light and velvet darkness.

“The truth is,” I told them, then pushed myself to live up to the principle my wife and I had established for contending not only with this issue but with all the other hypocrisies that life as a parent entails. I want to tell you / My head is filled with things to say, as George Harrison once sang, When you’re here / All those words, they seem to slip away. “The truth is that I’m confused about what to tell you,” I said. “But I mostly want us all to tell each other the truth.”

They said that sounded all right to them and that I shouldn’t worry. That’s just what I would have said at their age.

The Memory Hole (#ulink_a2ede531-c79c-5bfa-a2f1-8f761a885070)

Almost every school day, at least one of my four children comes home with art: a drawing, a painting, a piece of handicraft, a construction-paper assemblage, an enigmatic apparatus made from pipe cleaners, sparkles, and clay. And almost every bit of it ends up in the trash. My wife and I have to remember to shove the things down deep, lest one of the kids stumble across the ruin of his or her laboriously stapled paper-plate-and-dried-bean maraca wedged in with the junk mail and the collapsed packaging from a twelve-pack of squeezable yogurt. But there is so much of the stuff; we don’t know what else to do with it. We don’t toss all of it. We keep the good stuff – or what strikes us, in the Zen of that instant between scraping out the lunch box and sorting the mail, as good. As worthier somehow: more vivid, more elaborate, more accurate, more sweated over. A crayon drawing that fills the entire sheet of newsprint from corner to corner, a lifelike smile on the bill of a penciled flamingo. We stack the good stuff in a big drawer, and when the drawer is finally full, we pull out the stuff and stick it in a plastic bin that we keep in the attic. We never revisit it. We never get the children’s artwork down and sort through it with them, the way we do with photo albums, and say “That’s how you used to draw curly hair” or “See how you made your letter E’s with seven crossbars?” I’m not sure why we’re saving it except that getting rid of it feels so awful.

Under the curatorship of my mother, my brother’s and my collected artwork is, if I may say so, a vastly more impoverished archive. From the years preceding high school there is almost nothing at all. The countless scenes of strafing Spitfires taking heavy German ack-ack fire, the corrugated-cardboard-and-foil George Washington hatchets, the clay menorahs (I never did make any dreidels out of clay), the works in crayon resist and papier-mâché and yarn and in media so mixed as to include Cheerios, autumn leaves, and dirt – gone, all of it. Do I care? Does it pain me to have lost forever this irrefutable evidence of my having been, if neither a prodigy nor an embryonic Matisse, a child? If my mother had held on to more of my childhood artwork, would I be happier now? Would the narrative that I have constructed of the nature and course of my childhood be more complete? I guess ultimately, I have no way of answering these questions. It’s like wondering whether sex would be more pleasurable if I had not been worked over by that old Jew with a knife at the age of eight days. How much more pleasurable, really, do I need it to be?

When I run across one of the pieces of artwork that my mother did save – paintings that I made in my junior and senior years of high school, for the most part – the prevailing emotion I experience, with breathtaking vividness, is the acute discontent that I felt at the time of their creation, a dissatisfaction purified of any residual sense of pride or accomplishment. Their flaws of perspective and construction, the places where I cheated or fudged or simply could not pull something off, even a faint tempera-scented whiff of the general miasma of mortification and insufficiency in which I then swam – they all present themselves to my sight and recollection with a force that makes me a little ill.

I’m not trying to excuse the act of throwing away my children’s artwork. The crookedest mark of a colored pencil on the back of a bank-deposit envelope, vaguely in the shape of a fish, is like a bright, stray trace of the boundless pleasure I take in watching my kids interact with the world. The set of processes joining their minds to their fingertips is a source of profound interest and endless speculation, a mystery that, through their artworks, my children endlessly expound. I know that if I live long enough, a time will come when their childhoods will strike me as having been mythically brief. Almost nothing will remain of these days, and they will be women and men, and I will look back on the lost piles of their drawings and paintings and sketches, the cubic yards of rubbings and scratchings consigned to the recycling bin, the reef’s worth of shells, sand, and coral glued to their découpage souvenirs of vacations in Hawaii and Maine, and rue my barbarism. I will be haunted by the memory of the way my younger daughter looks at me when she chances upon a crumpled sheet of paper in the recycling bin, bearing the picture, the very portrait, of five minutes stolen from the headlong rush of their hour in my care: She looks betrayed.

“I don’t know how that got in there,” I tell her. “That was clearly a mistake. What a great dog.”

“It’s a girl kung fu master.”

“Of course,” I say. When she isn’t looking, I throw it away again.

It’s not only her artwork that I’m busy throwing away. Almost every hour that I spend with my children is disposed of just as surely, tossed aside, burned through like money by a man on a spree. The sum total of my clear memories of them – of their unintended aphorisms, gnomic jokes, and the sad plain truths they have expressed about the world; of incidents of precociousness, Gothic madness, sleepwalking, mythomania, and vomiting; of the way light has struck their hair or eyelashes on vanished afternoons; of the stupefying tedium of games we have played on rainy Sundays; of highlights and horrors from their encyclopedic history of odorousness; of the 297,000 minor kvetchings and heartfelt pleas I have responded to over the past eleven years with fury, tenderness, utter lack of interest, or a heartless and automatic compassion – those memories, when combined with the sum total of photographs that we have managed to take, probably add up, for all four of my children, to under 1 percent of everything that we have undergone, lived through, and taken pleasure in together.

The truth is that in every way, I am squandering the treasure of my life. It’s not that I don’t take enough pictures, though I don’t, or that I don’t keep a diary, though iCal and my monthly Visa bill are the closest I come to a thoughtful prose record of events. Every day is like a kid’s drawing, offered to you with a strange mixture of ceremoniousness and offhand disregard, yours for the keeping. Some of the days are rich and complicated, others inscrutable, others little more than a stray gray mark on a ragged page. Some you manage to hang on to, though your reasons for doing so are often hard to fathom. But most of them you just ball up and throw away.

The Binding of Isaac (#ulink_ea1175a0-0536-50b2-b521-4e799c6a0f87)

I was there, in Grant Park, on the night when Barack Obama began to shoulder all the possible meanings of his victory. You could hear it in his voice as the weight of it settled on him, and in the simple, judicious gravity of his language. You could see it in the glint, like the reflection of some awful or awesome vista, that lit his tired eyes. On a giant television screen to the right of the dais we could see what the world was seeing, and we could begin to imagine all the things that for Obama and for all of us were going to change henceforward. It was heady to contemplate, and thrilling, and after such a fierce and interminable campaign, there was also a tremendous sense of relief as we passed from the months of active wishing to this hour of having it be so. But among the most powerful emotions that stirred me as I stood there in the crowd, on that unseasonably warm evening with my son Abraham perched on my shoulders, was sadness. And that caught me a little unawares. I felt guilty about it. I knew I was only supposed to be happy at that moment, thrilled, grave, tired, relieved, duly awestruck – but happy. Yet I couldn’t stop thinking about his two little girls.

Like the rest of the world, even many of those who had (by their own accounts the next morning) voted, connived, pontificated, or railed against Barack Obama, I held my breath as I watched him first walk out to the podium that night with Michelle, Malia, and Sasha. The four of them, dressed in shades of red and black, seemed to catch and hold a different kind of light, the light of history, astonishing and clear. Time stopped, and I was conscious as I have been very few times in my life – the morning of September 11, 2001, was, terribly, another – of seeing something that had never been seen. It was not only the beauty, or the blackness, or the youth of the new first family, or some combination of the three. It was the unmistakable air of mutual engagement the Obamas give off, the sense of being a fully operational – loving, struggling, seeking, adjusting, testing, playing, mythologizing, arguing, rationalizing, celebrating, compromising, affirming, denying – family. I felt that I had never seen a presidential family that was so clearly a working family in the sense of the everyday effort involved. When I was born, there were children in the White House, though they moved out, half orphaned, before I was six months old. I can remember Tricia Nixon’s wedding, and Amy Carter and Chelsea Clinton getting braces or rolling Easter eggs on the White House lawn. But none of those families ever reminded me, ever seemed to reflect – at the fundamental level of daily operations where every great, august, well-reasoned principle and theory you profess or hold dear gets proved or shattered – my own.

With his daughters darting around his long legs, I saw Barack Obama as a father, like me. And I folded my hands behind my son’s knobby back, to bolster him there on my shoulders, and gave his bottom a squeeze, and watched those radiant girls waving and smiling at the quarter-million of us, faces and voices and starry camera flashes, and thought I would never have the nerve or the strength or the sense of mission or the grace or the cruelty to do that to you, kid. There are no moments more painful for a parent than those in which you contemplate your child’s perfect innocence of some imminent pain, misfortune, or sorrow. That innocence (like every kind of innocence children have) is rooted in their trust of you, one that you will shortly be obliged to betray; whether it is fair or not, whether you can help it or not, you are always the ultimate guarantor or destroyer of that innocence. And so, for a moment that night, all I could do was look up at the smiling little Obamas and pity them for everything they did not realize they were now going to lose: My heart broke, and I had this wild wish to undo everything we all had worked and hoped so hard, for so long, to bring about.

And then I noticed the way I seemed to be exempting myself, holding myself aloof, from responsibility for the kind of injury that I imagined Barack Obama had determined to inflict upon his children in the service of his conviction, his calling, his sense of duty, his altruism, his tragic or glorious destiny, and I felt the burden of my son weigh heavier on my own shoulders. You don’t have to become the president of the United States to betray your children. Being a father is an unlimited obligation, one that even the best of us, with the least demanding of children, could never hope to fulfill entirely. Children’s thirst for their fathers can never be slaked, no matter how bottomless and brimming the vessel. I have abandoned my children a thousand times, failed them, left their care and comfort to others, wandered in by telephone or e-mail from the void of a life on the road, issued arbitrary and contradictory commands from my mountaintop when all that was wanted was a place on my lap, absented myself from their bedtime routine on a night when they needed me more than usual, forestalled, deferred, or neglected their needs in the name of something I told myself merited the sacrifice. All that was in the very nature of fatherhood; it came with the territory.

Now, when I looked at Obama, whose own father had taken off when he was still a small boy, never to return, the pity I felt was for him. I hoisted my son higher on my shoulders and thought about his distant ancestor and namesake, armed with the fire and the knife of his great purpose, leading his son up Mount Moriah to pay the price that must be paid for the sacrifice that must be offered.

“Look at him,” I urged my son. “Look at Barack. Look at Malia and Sasha. Abraham, look at them, remember them. You’ll remember this night for the rest of your life.”

“How do you know I won’t forget?” my endlessly, implacably reasoning five-year-old said. He has always been a bit of a contrarian, and he may not have been fully in the spirit of Grant Park that night, either. “Maybe you won’t be there.”

He was right. I won’t be there some day, one day, when he looks back and finds that he still remembers the faraway night on my long-departed shoulders, the night in Chicago when everything began to change, for him and for Malia and Sasha and for the world. But I didn’t tell him that. Let him, let all of us, I thought, hold on to our innocence a little bit longer.

[ III ] STRATEGIES FOR THE FOLDING OF TIME (#ulink_d06513cb-1a7a-5f57-9bbd-76311d871716)

To the Legoland Station (#ulink_a524e2e9-856d-521c-b4cf-c32539232820)

Squares and rectangles. That’s what we had. Squares, rectangles, and wheels with chewy black rubber tires. Sloping red “roof” bricks of which there never seemed to be enough to cover a house. Trees shaped more like real trees than the schematic dendrites you get now. Windows and doors with snap-in glazing: more squares and rectangles. Six colors: basic red, white, blue, yellow, green, and black. And that was it.

Light blue, aquamarine, orange, purple, maroon, gold, silver, plum, pink – pink Legos! – and many shades of gray: Each of the original primary and secondary tones now has at least five variants, enabling the builder of, say, a Jawa Sandcrawler model to re-create the stippling of rust and corrosion in the Sandcrawler’s hull by varying his palette of reds and grays. I still get a funny feeling, a kind of tiny spasm of moral revulsion, when I pick up a teal or lilac Lego. As for shape, Lego “bricks” left behind the orthogonal world years ago for a strange geometry of irregular polygons, a vast bestiary of hybrid pieces, custom pieces, blanks and inverts, clears and pearlescents, freaks that have their raised dots or their gripping tubes on more than one side at a time. And then there are the people – minifigs, as they’re known among Legographers: Frankenstein monsters, American Indians, Jedi knights and pizza chefs, medieval crossbowmen and Vikings, deep-sea divers and bus drivers, Spider-Man, Harry Potter, Allen Iverson – the range of occupations and personalities to be found among the denizens of the Legosphere is so wide and elaborate that perhaps only the brain of an eight-year-old could possibly master it. I remember the sense of disdain I felt toward the cylinder-headed homunculi when minifigs began to be introduced, around the time when my original interest in Legos was waning. They didn’t have the painted faces back then. Their heads were shiny yellow voids. Their arms and legs couldn’t bend, and there was something of the nightmarish, something maimed, about them. But what I most resented about the minifigs was the scale they imposed on everything you built around them. Like Le Corbusier’s humancentric Modulor scale or Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man, the minifigs as they proliferated became the measure of all things: Weapons must fit their rigid grip, doorways accommodate the tops of their heads, cockpits accommodate their snap-on asses.

It was this sense of imposition, of predetermined boundaries and contours, of a formulary of play, that I found I most resented when Legos returned to my life, around the time my eldest child turned three. (She was into Indians, or rather, “Indians,” especially Tiger Lily; we bought her a fairly complicated Lego set with war-painted minifigs, horses, tepees, a canoe, a rocky cliff.) But along with the giddy profusion of shapes and colors that had taken place during my long absence from the Legosphere, the underlying purpose of the toys also appeared to have changed.

When I first began to play with them in the late 1960s, Legos retained a strong flavor of their austere, progressive Scandinavian origins. Abstract, minimal, “pure” in form and design, they echoed the dominant midcentury aesthetic, with its emphasis on utility and human perfectibility. They were a lineal descendant of Friedrich Fröbel’s famous “gifts,” the wooden stacking blocks that influenced Frank Lloyd Wright as a child, part mathematics, part pedagogy, a system – the Lego System – by which children could be led to infer complex patterns from a few fundamental principles of interrelationship and geometry. They also made, and make to this day, a strong claim on a kid’s senses, snapping together and coming apart with a satisfying dual appeal to the ear and the fingers. They presented the familiar objects one constructed with them – airplanes, houses, cars, faces – on a quirky grid, the world dissolved or simplified into big, chunky pixels.

In their limited repertoire of shapes and the absolute, even cruel, set of axioms governing the way they could and couldn’t be arranged, Lego structures emphatically did not present – and in playing with them, you never hoped for – the appearance of reality. A Lego construction was not a scale model. It was an idealization, an approximation, your best version of the thing you were trying to make. Any house, any town, you built from Legos, with its airport and tramline and monorail, trim chimneys and grids of grass, automatically took on a certain social-democratic tidiness, even sterility (one of the notable qualities of acrylonitrile butadiene styrene, the material from which Lego bricks are made, is that it is sterile).

Orderly, functional, utopian, half imaginary, abstract, primary-colored – when I visited Helsinki a few years back, I felt as if I recognized it, the way you recognize a place from a dream.

By the late nineties, when my wife and I bought that first Indian set, abstraction was dead. Full-blown realism reigned supreme in the Legosphere. Legos were sold in kits that enabled one to put together – at fine scales, in detail made possible by a wild array of odd-shaped pieces – precise replicas of Ferrari Formula 1 racers, pirate galleons, jet airplanes. Lego provided not only the standard public-domain play environments supplied by toy designers of the past fifty to a hundred years – the Wild West, the Middle Ages, jungle and farm and city street – but also a line of licensed Star Wars kits, the first of many subsequent ventures into trademarked, conglomerate-owned, pre-imagined environments. Instead of the printed booklets I remembered, featuring suggestions for the kinds of things you might want to make from your box of squares and rectangles, the new kits came encumbered with fat, abstruse, wordless manuals that laid out, panel after numbered panel and page after page, the steps that must be followed if one hoped – and after all, why else would you nudge your dad into buying it for you? – to end up with a landspeeder just like Luke Skywalker’s (only smaller). Where Lego-building had once been open-ended and exploratory, it now had far more in common with puzzle-solving, a process of moving incrementally toward an ideal, pre-established, and above all, a provided solution.

I resented this change. When my son and I finished putting together a TIE interceptor or Naboo starfighter, usually after several weeks of struggle, a half-deranged search for one tiny black chip of sterile styrene the size of his pinkie nail, and two or three bouts of prolonged despair, the resulting object was so undeniably handsome, and our investment of time in building it so immense, that the thought of playing with it, let alone ever disassembling it, was anathema. But more than the inherent difficulty – which, after all, is an important aspect of puzzle-solving, or the shift from exploration to reproduction – I resented the authoritarian nature of the new Lego. Though I admired and enjoyed Toy Story (1995), the film has always been tainted for me by its subtext of orthodoxy: its implied assertion that there is a right way and a wrong way to play with your toys. Andy, the young hero of Toy Story, uses his toys more or less the way their manufacturers intended – cowboys are cowboys; Mr. Potato Head, with his “angry eyes,” is a suitable mustachioed villain – while the most telling sign that we are to take Sid, the quasi-psychotic neighbor kid, as a “bad boy” is that he hybridizes and “breaks the rules” of orderly play, equipping an Erector-set spider, for example, with a stubbly doll’s head. Sid is mean, cruel, heartless, crazy: You can tell because he put his wrestler doll in a dress. A similar orthodoxy, a structure of control and implied obedience to the norms of the instruction manual and of the implacable exigencies of realism itself, seemed to have been unleashed, like the Dark Side of the Force, in the once bright Republic of Lego.

But I should have had more faith in my children, and in the saving power of the lawless imagination. Like all realisms, Lego realism was doomed. In part, this was an inevitable result of the quirks and limitations inherent in the Lego System, with the distortions that its various techniques of interlocking create. The addition of painted faces and elaborately modeled headgear, weapons, and accoutrements ultimately did little to diminish the fundamental silliness of the minifig; as with CGI animation, the technology falls down at the human form. In depicting people, it makes compromises that weaken the intended realism of the whole. But the technical limitations are only part of the greater failure of realism – defined as accuracy, precision, faithfulness to experience – to live up to the disorder, the unlikeliness, and the recombinant impulse of imagined experience.

Kids write their own manuals in a new language made up of the things we give them and the things that derive from the peculiar wiring of their heads. The power of Lego is revealed only after the models have been broken up or tossed, half finished, into the drawer. You sit down to make something and start digging around in the drawer or container, looking for a particular brick or axle, and the Legos circulate in the drawer with a peculiarly loud crunching noise. Sometimes you can’t find the piece you’re looking for, but a gear or a clear orange cone or a horned helmet catches your eye. Time after time, playing Legos with my kids, I would fall under the spell of the old familiar crunching. It’s the sound of creativity itself, of the inventive mind at work, making something new out of what you have been given by your culture, what you know you will need to do the job, and what you happen to stumble on along the way.

All kids – the good ones, too – have a psycho tinge of Sid, of the maker of hybrids and freaks. My children have used aerodynamic, streamlined bits and pieces of a dozen Star Wars kits, mixed with Lego dinosaur jaws, Lego aqualungs, Lego doubloons, Lego tibias, to devise improbably beautiful spacecraft far more commensurate than George Lucas’s with the mysteries of other galaxies and alien civilizations. They have equipped the manga-inspired Lego figures with Lego ichthyosaur flippers. When he was still a toddler, Abraham liked to put a glow-in-the-dark bedsheet-style Lego ghost costume over a Lego Green Goblin minifig and seat him on a Sioux horse, armed with a light saber, then make the Goblin do battle with a minifig Darth Vader, mounted on a black horse, armed with a bow and arrow. That is the aesthetic at work in the Legosphere now – not the modernist purity of the early years or the totalizing vision behind the dark empire of modern corporate marketing but the aesthetic of the Lego drawer, of the mash-up, the pastiche that destroys its sources at the same time that it makes use of and reinvents them. You churn around in the drawer and pull out what catches your eye, bits and pieces drawn from movies and history and your own fancy, and make something new, something no one has ever seen or imagined before.

The Wilderness of Childhood (#ulink_1760bf03-73a2-56e8-92c4-ea0d0f65299b)

When I was growing up, our house backed onto woods, a thin two-acre remnant of a once mighty Wilderness. This was in a Maryland city where the enlightened planners had provided a number of such lingering swaths of green. They were tame as can be, our woods, and yet at night they still filled with unfathomable shadows. In the winter they lay deep in snow and seemed to absorb, to swallow whole, all the ordinary noises of your body and your world. Scary things could still be imagined to take place in those woods. It was the place into which the bad boys fled after they egged your windows on Halloween and left your pumpkins pulped in the driveway. There were no Indians in those woods, but there had been once. We learned about them in school. Patuxent Indians, they’d been called. Swift, straight-shooting, silent as deer. Gone but for their lovely place names: Patapsco, Wicomico, Patuxent.

A minor but undeniable aura of romance was attached to the history of Maryland, my home state: refugee Catholic Englishmen, cavaliers in ringlets and ruffs; pirates, battles, the sack of Washington, “The Star-Spangled Banner,” Harriet Tubman, Antietam. And when you went out into those woods behind our house, you could feel all that, all that history, those battles and dramas and romances, those stories. You could work it into your games, your imaginings, your lonely flights from the turmoil or torpor of your life at home. My friends and I spent hours there, braves, crusaders, commandos, blues and grays.

But the Wilderness of Childhood, as any kid could attest who grew up, like my father, on the streets of Flatbush in the forties, had nothing to do with trees or nature. I could lose myself on vacant lots and playgrounds, in the alleyway behind the Wawa, in the neighbors’ yards, on the sidewalks. Anywhere, in short, I could reach on my bicycle, a 1970 Schwinn Typhoon, Coke-can red with a banana seat, a sissy bar, and ape-hanger handlebars. On it I covered the neighborhood in a regular route for half a mile in every direction. I knew the locations of all my classmates’ houses, the number of pets and siblings they had, the brand of Popsicle they served, the potential dangerousness of their fathers. Matt Groening once did a great Life in Hell strip that took the form of a map of Bongo’s neighborhood. At one end of a street that wound among yards and houses stood Bongo, the little one-eared rabbit boy. At the other stood his mother, about to blow her stack – Bongo was late for dinner again. Between Mother and Son lay the hazards – labeled ANGRY DOGS, ROVING GANG OF HOOLIGANS, GIRL WITH A CRUSH ON BONGO – of any journey through the Wilderness: deadly animals, antagonistic humans, lures and snares. It captured perfectly the mental maps of their worlds that children endlessly revise and refine. Childhood is a branch of cartography.

Most great stories of adventure, from The Hobbit to Seven Pillars of Wisdom, come furnished with a map. That’s because every story of adventure is in part the story of a landscape, of the interrelationship between human beings (or Hobbits, as the case may be) and topography. Every adventure story is conceivable only in terms of the particular set of geographical features that in each case sets the course, literally, of the tale. But I think there is another, deeper reason for the reliable presence of maps in the pages, or on the endpapers, of an adventure story, whether that story is imaginatively or factually true. We have this idea of armchair traveling, of the reader who seeks in the pages of a ripping yarn or a memoir of polar exploration the kind of heroism and danger, in unknown, half-legendary lands, that he or she could never hope to find in life. This is a mistaken notion, in my view. People read stories of adventure – and write them – because they have themselves been adventurers. Childhood is, or has been, or ought to be, the great original adventure, a tale of privation, courage, constant vigilance, danger, and sometimes calamity. For the most part the young adventurer sets forth equipped only with the fragmentary map – marked HERE THERE BE TYGERS and MEAN KID WITH AIR RIFLE – that he or she has been able to construct out of a patchwork of personal misfortune, bedtime reading, and the accumulated local lore of the neighborhood children.

A striking feature of literature for children is the number of stories, many of them classics of the genre, that feature the adventures of a child, more often a group of children, acting in a world where adults, particularly parents, are completely or effectively out of the picture. Think of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, The Railway Children, or Charles Schulz’s Peanuts. Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy presents a chilling version of this world in its depiction of Cittagazze, a city whose adults have all been stolen away. Then there is the very rich vein of children’s literature featuring ordinary contemporary children navigating and adventuring through a contemporary, nonfantastical world that is nonetheless beyond the direct influence of adults, at least some of the time. I’m thinking the Encyclopedia Brown books, the Great Brain books, the Henry Reed and Homer Price books, the stories of the Mad Scientists’ Club, a fair share of the early works of Beverly Cleary. As a kid, I was extremely fond of a series of biographies, largely fictional, I’m sure, that dramatized the lives of famous Americans – Washington, Jefferson, Kit Carson, Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, Daniel Boone – when they were children. (Boys, for the most part, though I do remember reading one about Clara Barton.) One element that was almost universal in these stories was the vast amounts of time the famous historical boys were alleged to have spent wandering with bosom companions, with friendly Indian boys or a devoted slave, through the once mighty wilderness, the Wilderness of Childhood, entirely free of adult supervision.

Though the wilderness available to me had shrunk to a mere green scrap of its former enormousness, though so much about childhood had changed in the years between the days of young George Washington’s adventuring on his side of the Potomac and my own suburban exploits on mine, there was still a connectedness there, a continuum of childhood. Eighteenth-century Virginia, twentieth-century Maryland, tenth-century Britain, Narnia, Neverland, Prydain – it was all the same Wilderness. Those legendary wanderings of Boone and Carson and young Daniel Beard (the father of the Boy Scouts of America), those games of war and exploration I read about, those frightening encounters with genuine menace, far from the help or interference of mother and father, seemed to me at the time – and I think this is my key point – absolutely familiar to me.

The thing that strikes me now when I think about the Wilderness of Childhood is the incredible degree of freedom my parents gave me to adventure there. A very grave, very significant shift in our idea of childhood has occurred since then. The Wilderness of Childhood is gone; the days of adventure are past. The land ruled by children, to which a kid might exile himself for at least some portion of every day from the neighboring kingdom of adulthood, has in large part been taken over, co-opted, colonized, and finally absorbed by the neighbors.

The traveler soon learns that the only way to come to know a city, to form a mental map of it, however provisional, and begin to find his or her own way around it, is to visit it alone, preferably on foot, and then become as lost as one possibly can. I have been to Chicago maybe a half-dozen times in my life, on book tours, and yet I still don’t know my North Shore from my North Side, because every time I’ve visited, I have been picked up and driven around, and taken to see the sights by someone far more versed than I in the city’s wonders and hazards. State Street, Halsted Street, the Loop – to me it’s all a vast jumbled lot of stage sets and backdrops passing by the window of a car.