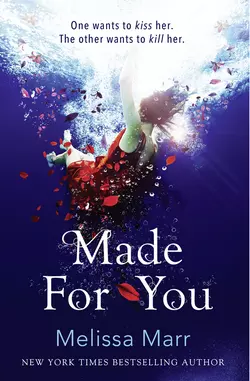

Made For You

Melissa Marr

Contemporary, racy thriller packed with chilling twists, unrequited obsession and high-stakes. From New York Times bestselling author Melissa Marr.Eva Tilling wakes up in the hospital to discover an attempt has been made on her life. But who in her sleepy town could have hit her with their car? And why? Before she can consider the question, she finds that she's awoken with a strange new skill: the ability to foresee people's deaths when they touch her.While she is recovering from the hit-and-run, Nate, an old friend, reappears, and the two must traverse their rocky past as they figure out how to use Eva's power to keep her friends -and themselves – alive. But the killer is obsessed and will stop at nothing to get to Eva…

Copyright (#ulink_6dedffe6-7a8e-5ec6-a63c-e5f4ce4cdc37)

First published in hardback in the USA by HarperCollins Publishers Inc in 2014

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London, SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Copyright © Melissa Marr 2014

Design and typography © www.blacksheep-uk.com

Flower and girl © Getty Images

Melissa Marr asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007584208

Ebook Edition © 2014 ISBN: 9780008118174

Version: 2015-01-14

Dedication (#ulink_7c5fc8ad-ac46-5e0f-b3b4-3b635d9d98ce)

For the nurses, techs, and doctors in NICU, CCN, and Pediatrics at Eastern Maine Medical Center in Bangor, Maine. There aren’t words enough to tell you how much I appreciate your care, support, and love this past year.

Contents

Cover (#u54551d86-a53a-512d-81a2-02ffbd16a53c)

Title Page (#ud7aff6d3-cc73-5ea2-80d1-6dde173770cd)

Copyright (#u46f67fa9-ea0b-53ee-a363-81080b0c71a4)

Dedication (#ufb15ba5b-f66d-5cea-8dbf-48f4b03eaf4c)

Day 0: “The Party”: Eva (#ucbb8293d-07bf-5df9-942e-ff1e446230e0)

Day 1: “The Act”: Judge (#ud943d452-2b7e-5791-a148-31e3d2e87eaa)

Day 3: “The Vision”: Eva (#u8269dff6-5390-52df-a25c-1371403b577d)

Day 5: “The Visit”: Judge (#uff4fb9c4-2166-570d-a084-093c4fc2c3c8)

Day 5: “The Detective”: Eva (#u8babaa34-5575-5e16-b9eb-acbfef0694a2)

Day 6: “The Piper-Ettes”: Grace (#ub61af886-a12d-5364-80ce-97e2ae73eeec)

Day 6: “The Surprise”: Eva (#u17a59da6-d571-5794-90d0-95bc3f34eaa1)

Day 6: “The Girl”: Judge (#uf2c35d97-8eab-5d22-93c8-c514be9464da)

Day 7: “The Best Friend”: Eva (#ub56976fa-3568-520f-897c-b00bb694b3b6)

Day 8: “The Crush”: Eva (#u206fec22-e585-53d9-8d69-0baa89bb1dac)

Day 8: “The Message”: Judge (#u6a2aec11-5b85-57e5-bfd8-71fdea055c3f)

Day 9: “The News”: Eva (#litres_trial_promo)

Day 9: “The Sleepover”: Eva (#litres_trial_promo)

Day 10: “The Parents”: Eva (#litres_trial_promo)

Day 10: “The Stalker”: Judge (#litres_trial_promo)

Day 11: “The Ex-Boyfriend”: Eva (#litres_trial_promo)

Day 11: “The Lies”: Grace (#litres_trial_promo)

Day 11: “The Job”: Eva (#litres_trial_promo)

Day 12: “The Sacrifice”: Judge (#litres_trial_promo)

Day 13: “The Veil”: Eva (#litres_trial_promo)

Day 13: “The Admission”: Grace (#litres_trial_promo)

Day 13: “The Funeral”: Eva (#litres_trial_promo)

Day 13: “The Substitute”: Judge (#litres_trial_promo)

Day 13: “The Pictures”: Eva (#litres_trial_promo)

Day 14: “The Flowers”: Eva (#litres_trial_promo)

Day 14: “The Plan”: Grace (#litres_trial_promo)

Day 14: “The Adulterer”: Judge (#litres_trial_promo)

Day 14: “The Testing”: Eva (#litres_trial_promo)

Day 14: “The Proof”: Eva (#litres_trial_promo)

Day 14: “The Task”: Judge (#litres_trial_promo)

Day 14: “The Kiss”: Eva (#litres_trial_promo)

Day 14: “The Challenge”: Judge (#litres_trial_promo)

Day 15: “The Talk”: Eva (#litres_trial_promo)

Day 15: “The Epiphany”: Judge (#litres_trial_promo)

Day 15: “The Cabin”: Grace (#litres_trial_promo)

Day 15: “The Gun”: Eva (#litres_trial_promo)

Day 15: “The Fight”: Judge (#litres_trial_promo)

Day 15: “The Confession”: Eva (#litres_trial_promo)

Day 15: “The Pipe”: Grace (#litres_trial_promo)

Day 15: “The Killer”: Eva (#litres_trial_promo)

Day 136: “The Aftermath”: Eva (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Melissa Marr (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

DAY 0: “THE PARTY” (#ulink_6160a43e-9c93-57f3-aeec-24eb733e8495)

Eva (#ulink_6160a43e-9c93-57f3-aeec-24eb733e8495)

“DID YOU SEE HER?” Piper whispers, lifting the same plastic cup of wine she’s been holding the past two hours as if it hides her. It’s a prop. She’s sober. She always is. She’s also hopelessly prone to melodrama.

I nod, face carefully blank. Of course I saw her. I’ve seen every single girl that flirts with Nate at these parties.

I’d rather not be a witness to it, but that’s one of the downsides to being me: I’m expected to be at every party. Like Piper and the rest of our crowd, I am here because it’s who I am and what I do. Nate isn’t one of us, hasn’t been for a couple years, so he doesn’t always attend, but when he does, he inevitably goes upstairs or down a darkened hallway with some girl. I pretend not to care. My act works on everyone but Piper and Grace, who sit on either side of me.

“She’s not even that pretty,” Piper lies.

Grace says nothing.

The girl is no prettier than us, but she’s not less attractive either.

Nate is a lot more than good-looking. Tall and lean without being gangly, short dark hair that’s cut in an almost military style, and muscles that make it hard not to find an excuse to touch his arms. Even though he has no social standing, he has to use exactly zero effort to convince girls to wander off into the dark with him.

We used to be friends. He used to be my best friend. Then his parents got divorced, and he became someone I didn’t know. I still watch him, but I never speak to him. I haven’t since the start of sophomore year. Every time I see him glance my way as he walks past with a girl, I think of the last time I tried to talk to him.

It’s the first party of the year, and my parents are away again. I’m sitting with Grace, a new girl who moved from Philadelphia to tiny little Jessup, North Carolina.

“Who’s he?” Grace asks.

“Nathaniel Bouchet.” I look at him, standing in the doorway surveying the room like a hunter. He doesn’t look like my Nate anymore. He’s always been wiry, but now he looks like he works at his physique. I swallow, realizing that I’m staring and that he can tell.

“Excuse me a minute,” I say.

Robert and Reid are sitting with us, but I excuse myself to walk over to Nate. It’s been forever since we spoke. He hasn’t called or come to see me in weeks. I never catch him at school either. I miss him. Even after he stopped being around the rest of our friends, he was still my friend. I thought that would never change, but now, I think I might be wrong.

I’ve had a couple drinks, and it gives me the courage to ignore his dismissive glance and walk up to him.

“Nate,” I start.

I only want to talk, to go back to the way we were, but he looks right at me, his gaze roaming from my sandals up my jeans and over my blouse and ending on my face. “Not interested.”

Then he steps around me like we’re strangers. He just walks past me like I’m not there, like he doesn’t know me, like we haven’t been in one another’s lives since we were in preschool. I feel like everyone there is staring at us, but if they are, no one mentions it—not to me, at least. My last name protects me from that, and for a change, I’m glad to be a Cooper-Tilling.

Nate, on the other hand, has just sealed his pariah reputation. It was bad enough that his parents divorced, and he suddenly seemed to forget that there were clothes in colors other than black. Now, he’s been rude to me in front of everyone. If he was trying to make the rest of my friends declare him invisible, he just succeeded.

On Monday, I find out that he slept with Piper’s cousin, Julie, who was visiting. She’s three years older than us, a freshman at Duke. After that, it became a thing to talk about which girl he chose for the night when he turned up at parties. After that, I didn’t talk to him—or let him see me watching him—ever again.

Piper is waiting for her cue, for me to tell her what to think. It’s how things are in Jessup. She’s one of the elite, but I’m the one she follows. My parents are the top of the food pyramid here. It’s not a situation I cherish, and I pretend not to notice.

I simply play my part, fulfill their expectations and smile. It’s the best plan I have.

I know that Piper is hoping for permission to tear Nate down, but I’m not going there. “She’s no different than the last three. He’ll leave in the morning with her phone number, but he won’t use it.”

“What are you two whispering about?” Reid asks as he flops down next to Piper and drapes an arm around her shoulders. They’re not dating; he simply has no awareness of personal space.

Piper shrugs him off. “Losers.”

“I’ll protect you,” Reid promises.

“Who’s to say you weren’t the problem we were discussing?” Piper says, but she doesn’t mean anything by it. Reid is one of us.

“Yeung.” Reid glances at Grace and nods at her, then turns to me. “Eva.”

“I have a first name!” Grace snaps.

Before they start bickering Piper quickly redirects the conversation. “Did you guys want to go to Durham for the Bulls game? Daddy has a bunch of tickets that he said we could use.”

I tune them out. It’s far too easy to do, really. The conversation, the people, the whole party is like most every other Friday for the past couple years. Sometimes I want to ask them if they’re happy, if they enjoy their lives or if they feel like they’re just playing roles like me.

Grace tolerates Jessup, but this is only a pit stop for her. Reid is hard to decipher; he never gives a straight answer. On the other hand, my boyfriend, Robert, seems to like being one of the town darlings. He has an entourage everywhere he goes—and likes it. I don’t. They’re my friends though, so I smile at them before I top off my glass of lukewarm wine from a bottle that has my grandfather’s last name on the label.

Politely, I carry the bottle over to Robert where he still stands with Grayson and Jamie. Robert absently kisses the top of my head and holds his cup out toward me. The other boys are drinking beer, but Robert always drinks wine from the Cooper Winery when I’m with him.

I don’t glance toward the doorway that leads to the bedrooms. I don’t think about Nate kissing some girl who isn’t me. No, not at all. Not even a little.

After I fill Robert’s cup, I wait. I’m not clingy; I don’t interrupt. I simply wait until the boys notice and walk away. Once they’re gone, Robert looks at me carefully, studying my face for a moment before asking, “Is everything okay?”

“I’m bored.”

He laughs. “All of our friends and a bunch of people from school are here, and you’re bored?”

“Piper only wants to gossip. Reid is … Reid. Grace is pouting or maybe arguing with Reid by now. You”—I poke him in the chest—“were over here, so yes, I’m bored.”

He grins, sips his wine, and waits. I can’t deny that he’s one of the best-looking boys I’ve ever seen. He’s certainly one of the best-looking in Jessup. Basketball, baseball, and tennis keep him in perfect shape, and he has the bluest eyes of anyone I know. It’s not his fault that I wish they were chocolate brown instead.

“Can we leave? Maybe drive out to—”

“You know better than that,” he interrupts quietly. “Everyone would want to come with us as soon as we said we were heading out.”

Everyone, of course, means our closest friends, but they’re the same people I’ve spent the past few hours with—really, the past seventeen years with if I want to get technical. They’re my friends, and I love them. Sometimes, though, I want to be just a girl with her boyfriend, not a girl, her boyfriend, and their dozen closest friends.

“Fine.” I blush a little before suggesting, “We could go to one of the bedrooms …”

“With all of our friends out here?” Robert looks at me like I suggested we have sex on the coffee table.

“Just to fool around,” I clarify.

He leans in and kisses me briefly, lips closed, and then he wraps an arm around my waist. “Come on.”

For a moment I think he’s agreed with me, but then I realize that he’s headed back to the sofa. He murmurs in my ear, “We can do that at your house any day. Tomorrow, I’ll meet you at Java the Hut, and then we’ll go to your house for a dessert.”

I nod. There’s no way to say that it isn’t really physical contact I want.

I want to feel swept away. I want to not sit here listening to gossip while Nate has sex in another room. I want to be wanted—and distracted. Instead, I sit next to Robert, our hands twined together, and resume the same routine.

“You totally missed it,” Piper gushes. “You will never believe what Davey Jackson just did!”

Nothing ever changes, not here, not for me.

DAY 1: “THE ACT” (#ulink_9c399431-6fa6-5ecf-aa38-515f4e5951df)

Judge (#ulink_9c399431-6fa6-5ecf-aa38-515f4e5951df)

I SIT AND WAIT in my stolen car. The engine is still; the lights are off. I can’t even listen to music. I don’t want anyone to see or hear me.

I thought Eva understood me. Last night, she proved me wrong. She looked straight through me like I wasn’t there and spent half the night paying attention to him, one of the countless people who will never ever deserve her. He’s not right for her. I am.

When I see Eva walking away from the mostly empty parking lot and heading down the deserted street, I wish I had another option. I’ve been waiting for her to see the real me for so long, doing the things she asked of me so she would know I was the one for her.

I listened to every secret message she gave me. She was like a goddess in my mind.

Maybe that’s where I went wrong. The Lord ordered that “Thou shalt have no other gods before me.” In my heart, I raised Eva up like a false idol. That was a mistake. Now I have to atone, not just for my sake, but for the safety of my future children. The good book says “I the Lord thy God am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children.” I have to protect the children I’ll one day have.

“I’m sorry. I’m so sorry.” I say the words quietly as I wait for her.

I picture her even after I can’t see her anymore. She could’ve called Grace to pick her up tonight. She didn’t. It would have been a sign if she had. I watch the signs. Eva Tilling—princess of Jessup, North Carolina—is alone. I made sure she would be, but I hoped we would be saved from this.

I turn the key, and the engine wakes. I turn on the stereo and shift out of park. My eyes burn, and my hands tighten on the steering wheel as I drive toward her. I flick the high beams on and turn the music up so loud that she can probably hear it now. I feel like I can hear the gravel crunch under the tires as I swerve onto the shoulder, but I can’t, not over the music. I searched for the perfect song, “Lift Me Up,” to tell her all the things I can’t say. I hope she is listening. I know the Lord is.

I feel like my heart is beating in tune with the thundering drums, and I slam the gas pedal down before I can hesitate. I feel the thump, and through my tears, I see her hit the hood of the car and slide off.

I don’t slow down. I can’t. I can’t even look in the rearview mirror. I did it, but it hurt. God, it hurt to sacrifice the one person I thought was meant to be mine. My Eva is bleeding along the side of the road. This was the only choice left to me.

I had to kill her.

DAY 3: “THE VISION” (#ulink_fb496fe0-a20b-54ce-a347-c70a67b831d0)

Eva (#ulink_fb496fe0-a20b-54ce-a347-c70a67b831d0)

MY MIND IS FUZZY. I hear unfamiliar noises, and I don’t know why. My eyelids weigh too much, and I can’t make them open to see where that awful beeping is. I think about sitting up, but if I can’t move my eyelids, I surely can’t move my whole body. I try anyhow. Someone grabs my arm, speaks softly in words I can’t make out, but it doesn’t matter.

All that really matters suddenly is that I’m falling.

I know I’m already on my back but somehow I still fall.

I fall into someone. I know it’s not my skin I’m wearing even though it somehow is mine for the moment. The woman I am inside is waiting for her grandson, Ethan. He should have been here by now. My chest hurts. I have—no, she has—had this twinge all day, and even though it’s probably nothing, it scares me.

Somewhere in my mind, I remind myself that this is not me, that I am Eva Elizabeth Tilling. I am only seventeen, and I have no children or grandchildren.

I try to pull myself out of her skin, but I’m stuck here. My heart hurts. It feels like the beats are going too fast, like I’ve been drinking nothing but caffeine for days, and somehow it keeps going faster and faster. My hands tighten on the arms of the chair. I need to get up, to call someone, to do something. Ethan isn’t here, and I can’t drive, and I think my heart is going to pound out of my chest.

I hear footsteps. He comes into the room. I look up to see a boy standing there.

His hands are on me, helping me not to fall so fast to the ground. I try to say something, but my heart stops racing. I feel it stop.

“Eva?” Grace’s voice interrupts my death, pulling me back into my own skin with a snap, making me try to squirm away from the nurse who holds my wrist in her hand.

I feel her hand like it’s burning me. I try to look to see if the skin is red, but I still can’t focus my eyes.

“You’re awake,” the nurse says, before releasing my wrist to write something on the folded-up paper in her hand.

“Heart attack.” I’m shaking all over and cold like I’ve just been wrapped in icy sheets. Every part of me, other than my wrist, feels frigid.

“No, sweetie. You’re fine.”

“Heart attack,” I manage to say, even as I notice that my heart isn’t aching now. Just a dream. It was a dream. I’m not a mother, much less a grandmother. I don’t know anyone named Ethan either. I can’t remember what he looked like. I only remember the voice, the fear in it, and the way his hands felt strong while he helped slow my fall. I can see the whole thing playing over in my mind, can catalogue everything but his face.

“Your pulse is fine,” the nurse says as she puts medicine into the tube that hangs from an IV bag beside the bed. “Your heart is fine, Eva.”

“I don’t want to die. So cold.” I feel like I’m drifting again, and I’m scared, so I grab the nurse’s hand. “Freezing.”

“I’ll get a warm blanket,” she promises.

I’m cold, and I hurt all over. I close my eyes. I’m not sure how long I float in that nebulous state between awake and dreaming. When I hear the sound of footsteps, squeaky soles on the tile floor, I wonder if the pain or the footsteps woke me.

I look over at the white-clad woman. She moves a tube that hangs on the side of my bed and stretches to me. It’s obviously an IV line, but I don’t know why it’s there—or why I’m here.

I feel the cold start to crawl up my arm as the medicine travels through my vein from my wrist upward. It’s a disturbing feeling, one I’d like to stop, but by the time I force my lips open to ask the nurse about it, I’m alone in my room. My mind is encased in an ever-increasing fog, and I’m pretty sure the fog is because of that tube in my arm.

I’m not sure if moments or minutes pass before I ask, “Where am I?”

If someone answers, I don’t hear it. Sleep or drugs make the fog and weight stronger, and I’m out again. When I wake the next two times, I try again to ask questions, but if anyone answers—or hears me—I’m not aware of it. All I know is that I hurt, and then I’m drifting away. Maybe that’s why I dreamed of dying: I hurt from my legs to my head. Vaguely, I realize that between the hurt, the IV, and the nurse, I’m obviously in a hospital. I’m just not sure why.

In one of my moments of lucidity, I realize that I can’t move my arms or right leg, but I’m not sure if it’s from the medicine pumping into my veins or if there’s another reason.

“I’m right here,” Grace says from somewhere nearby. I can’t see her, but I’d know her voice anywhere.

“Grace?” With far too much effort, I try to focus on the shape in the chair that is apparently my usually hyper friend.

“Rest. You’re safe, sweetie. We’re here,” Mrs. Yeung says, and I realize that Grace’s mother is somewhere beside her. “You just came out of surgery.”

Grace hurries over to stand beside the bed. “You’re going to be okay, though, and I’m here with you.”

“Don’t leave me, Gracie.”

“I won’t,” she promises, and I am relieved. There’s no one in this world I trust more than Grace Yeung.

“Everything is okay now,” Grace says. She reaches out one hand as if she’s going to brush it over my face, but she doesn’t actually touch me. It’s only the shadow of her hand that lands on me.

“You’re going to be okay,” Mrs. Yeung repeats.

I glance at her and then look back at Grace. She nods in agreement, and then I’m out again.

This time my dreams are a strange mix that may be a series of wakeful moments and unconsciousness. If not, I’m dreaming about nurses and Grace sliding a chair near the bed with a horrible screeching noise—which seems a bit unlikely.

“Why am I here?” I ask, possibly again, possibly for the first time. I don’t remember if I’ve asked, but it’s the most reasonable question after “where am I?”

As promised, Grace is still here. Mrs. Yeung isn’t with her now, but that doesn’t matter. The chair is beside the bed, and her voice is quiet as she answers, “They had to bring you to Durham. You’re in Mercy Hospital. You were unconscious; ‘head trauma,’ they said, but you woke up late last night. This morning, you had surgery on your leg for a broken femur.”

I nod.

“They had to delay the surgery a day, but they operated today. It went well,” Grace says. “You’re in a new room now. You were in ICU.”

“Hazy.”

“You’re still coming out of the anesthesia. Plus, they gave you sedatives,” she explains.

Time passes, and eventually, my head feels clearer. I swallow, trying to speak with a tongue that feels too thick and a mouth that feels too dry, before repeating, “Why am I here?”

Grace doesn’t answer for a moment, so I watch her face for answers. People are more transparent than they think. Even with whatever medicines pump through the IV tubes, I have enough clarity of mind to see the worry and the anger in Grace’s face. Whatever happened to land me in this bed sent my best friend into a mix of emotions that she’s trying to hide.

“Your parents really should be here to tell you this,” Grace starts. Her lips press together in a judgmental way that’s very familiar when my parents are mentioned. She’s far more judgmental about my parents than I am. I like the independence I have because of their travel and work schedule.

I glance at the giant vase of flowers in the room and know that it’s from them. There are other smaller arrangements, but the big one is orchids, my favorite flower. It’s huge and overflowing. “They sent those.”

“These were waiting when we got to your new room,” Grace says, but she scowls again. Orchids don’t make up for their absence in her book, but I’m sure they have a reason for being away. They always do. Most of the reasons boil down to them forgetting that I’m not actually an adult yet—not that I’m complaining.

“Why did I need surgery?”

“There was an accident,” Grace says, her expression going from angry to gentle in a blink.

I grab her hand and tug.

She straightens her arm so our clasped hands rest on the edge of the hospital bed. She looks almost as tired as I feel. She squeezes my hand and stares at me. Her eyes are red and puffy, and I can tell she’s been crying a lot and sleeping only a little. “I’m glad you’re okay,” she whispers. “I was so scared. You must’ve been terrified.”

“I don’t think I … I don’t remember anything,” I tell her. My voice wavers a little, but I’m not as upset as I probably should be. I feel sort of like I’m in a haze, which raises another question. “What am I on?”

“An antiseizure drug, a muscle relaxer, and … I’m not sure what else.” Grace glances at the bag of medicine. “Sugar water or something for hydration. Plus sedatives and stuff from the surgery.”

“Where’s your mom?” I ask. I’d heard Mrs. Yeung earlier, but I don’t see her.

When my parents travel, she’s my unofficial mom. Truthfully, she fills that function even when they’re home, but when they’re away, she has a signed power of attorney form for emergencies. My parents trust her completely—and for good reason. Mrs. Yeung has all the traits that “good Christians” in the South are supposed to have, including a few that my parents lack. She’s a stay-at-home mom who gave up a career to move to our little backwater town in North Carolina with her husband when he got a chance at his dream job.

“She had to leave,” Grace says. “We’ve been here a lot, and Jimmy had to miss a game already. She wanted to stay till you woke, but—”

“She was here when I needed her,” I interrupt. “She’s awesome.”

Grace scoffs. “Yeah, you say that because you don’t live with her. The other day …”

I know that Grace is still talking, but I can’t focus on what she’s saying. Things don’t add up. I remember leaving the coffee shop. Robert was to meet me, but he didn’t show. We didn’t argue at the party the night before. He was distant, but we didn’t fight or anything. We never really fight. We’re friends who’ve known each other since the cradle and decided to date last year, but honestly, we still mostly feel like friends who sometimes have sex. Fighting isn’t an issue for us, so when he didn’t show for our date and didn’t answer when I called—or when I texted him—I was confused.

Both my parents and Grandfather Cooper were out of town. Grandfather Tilling was home, but he goes to bed early, so I didn’t want to bother him, and I felt stupid calling Grace to come pick me up when it was only a couple miles to walk. Really, it would’ve taken longer for Grace to get there than it would for me to walk it.

“I was on my way home. I remember that. Robert forgot me or something.” I look at Grace, as if her face holds the secrets I can’t find inside my memories. Sometimes with Grace it kind of does. She’s very readable. She squeezes my fingers, and I notice that I’m still holding on to Grace’s hand.

“You got hit by a car when you were walking, sweetie.”

“Hit? Like someone ran over me?” I try to remember, but I have nothing. It’s a bright blur there when I try to think about it.

“Yes.” She starts to tear up and adds quickly, “But you’ll be okay. You hit your head; they call it a traumatic brain injury. That’s why you can’t remember things, and you have a broken leg, some bruised ribs, and … lots of black and blue.”

But Grace looks down and won’t meet my eyes, and I know there’s more.

My mouth feels like the desert looks, and I have to swallow before I can prompt, “And? Am I …” I look down at my feet and quickly wiggle my toes. Then I glance at my stomach and arms. There’s a bandage on my right forearm, as well as scrapes and cuts on my hands. The cuts aren’t as bad on my left arm, but my right biceps is liberally decorated with slashes and dots. My left arm is scratched and cut, but nothing severe. Looking at my skin isn’t going to tell me if there’s something really wrong under it though. “Did I lose an organ or …”

“No! You still have all your organs; you’re not paralyzed. You’ll be fine,” Grace hurriedly assures me. “They put a plate in your leg, but that’s not going to mean much other than physical therapy. You hit your head pretty hard, and we were scared about that. You were out for a while, but you’re awake now and seem okay so … that’s good, too.”

She’s still avoiding saying something though. I know her too well for her to succeed at it. For someone so eager to dive into confrontation with most people, she treats me like I’m in need of sheltering. I take a deep breath and ask, “And? Just tell me.”

“There was a lot of glass. That’s all. You got some cuts, like on your arm. The big injuries were your leg and your head … your brain, really, but it seems like they’ll be fine.” She holds my gaze as if staring at me will keep me from reading whatever secrets she wants to hide. I know she’ll tell me; she always tells me even when she doesn’t want to do so. Earlier this year, when Amy blabbed to everyone at school that I had slept with Robert, Grace tried to protect me. She shielded me from the things people were saying, but even then, she gave in after a couple of days and spilled. I don’t want to wait this time.

“Gracie … what aren’t you saying?”

She sighs and hedges, “You’re going to have some scars on your face. It’s not really that b—”

“Mirror.”

“Sweetie, maybe not yet.”

“Mirror,” I repeat, louder this time.

“Eva, let’s just wait until you’re feeling better, and it’s heal—”

“Please.”

I watch Grace dig through her bag and pull out the little silver compact that her grandmother gave her for her sixteenth birthday. For a moment, Grace holds it in her hand, squeezing it so tightly that her knuckles look like the skin has grown thinner there.

She holds it out to me, and I don’t let myself hesitate. I’m not vain, not really. I’m not the most beautiful girl in the world, but I’ve always been pretty enough to not be jealous or insecure. I have dark blue eyes, a smallish nose, lips that look pouty, and cheekbones that are defined without looking razor-sharp. I’m not opposed to wearing makeup, but I’ve always been happy that I don’t need it.

I gaze at the reflection in the glass. The girl I see now needs makeup badly. Red lines crisscross my face. Dark blue stitches highlight some of them. As much as I want to, I can’t look away from the tiny reflection of myself, and I’m glad that Grace’s mirror is so small.

I reach up to touch the black-and-blue marks and cuts on my throat, but before I can, Grace grabs my hand. “No touching. The nurses said you shouldn’t irritate the wounds. We had to keep your wrists restrained at first.”

Even as she tells me that I was tied to my bed, which is disturbing on some basic level, I can’t look away from my reflection. I dart my tongue out to touch the cut on my lip and promptly wince. I don’t hurt like I should, and I know that it’s because of the medicine coursing through my body. One particularly long cut runs from just under my eye to the side of my cheek where it curls under my ear and vanishes into my hair. That one has been stitched. Vaguely it registers that the ones deep enough to need stitches are the ones that’ll scar the most. Some of the others are only shallow cuts like the ones on my arm, so I think they’ll fade.

The tiny cuts vanish under the top of my shirt, and I look at my arms again. I was wearing a long-sleeved shirt when I walked home. Maybe that protected them a little, or maybe it was just how I hit the ground or how the car hit me. All I know for sure is that it’s my face that took the worst of the impact. I glance back at the mirror, hoping for a moment that it isn’t as bad as I first thought. It is though. No amount of healing is going to make these all vanish.

I close my eyes, and Grace takes the mirror from my hand. She doesn’t tell me that everything is okay or that it’s not as bad as it looks. She might try to hide things from me when she thinks it’s for my own good, but she doesn’t ever lie to me.

The day of the accident was the last day I was pretty.

DAY 5: “THE VISIT” (#ulink_d0d8b559-d08b-5e51-9ba9-c2092fbd4e54)

Judge (#ulink_d0d8b559-d08b-5e51-9ba9-c2092fbd4e54)

WHEN THE CAR HIT Eva, the thump of her body was louder than I expected. It reminded me more of hitting a deer than a possum. I’m not sure why I was surprised. Girls aren’t the same size as possums, but I suspect I thought more of her nature than her size. The initial thump of her body was followed by a thud as she fell against the car hood. I’ve dreamed about it twice since I hit her, since I thought I’d killed her.

I swallow and keep walking toward the entrance. No one looks at me any more than they do the nurses and techs that fill the halls at Mercy Hospital. I’m part of the scenery here. I’m nobody important.

Neither is she.

I can’t tell anyone that though. They wouldn’t understand. It’s not that I need approval. I don’t. I don’t need a lot of things. What I do need is to see Eva. I’ve been thinking about it—thinking about her—since she fell. I have to know if she’s really alive.

The article in the Jessup Observer says she is. I carefully clipped it out to save for my book, but after the fourth read, I needed a second copy because the ink was smeared and the edges were crumpled. I was careful with the second copy. Now, though, I hold the original clipping in my hands.

Eva Tilling, the granddaughter of both Davis Cooper IV (Cooper Winery owner and CEO) and of the esteemed Reverend Tilling, suffered multiple serious injuries after a hit-and-run earlier this week.

Miss Tilling, 17, underwent surgery this week and remains at Mercy Hospital in Durham, where she was transported after the incident. She is in critical but stable condition.

The victim was walking unaccompanied when she was run down by an as yet unknown vehicle. Authorities believe Tilling was only alone for moments after being struck when another passing vehicle saw her unconscious along the road and called 911.

The Jessup sheriff’s office is looking for witnesses to the incident. They said evidence has been recovered but declined to discuss specifics.

An arrest has not been made at this time.

The staff at the Jessup Observer would like to extend our prayers and thoughts to both the Tilling and Cooper families during this difficult time.

I know the staff writer has to suck up to the Cooper-Tilling family. No matter what They do, they’re always thought innocent. The paper is only one of the many things They control. I didn’t realize it a few years ago, but I see it now: Jessup is owned by Them, the ones who support the crazy rules that govern every interaction in Jessup. I’m not ruled by Them, not now, not ever again. Eva wasn’t either, but that changed. She became corrupt. I have seen it, dirt on her flesh where the corruption has begun to take root. She was the shining light, the proof that not everyone believed Their lies. Then she fell. She became just as guilty as the rest of Them, so I had to act before the corruption consumed her. It’s like a disease, eating away at all that’s good and pure.

I ran over her to save her.

I was willing to let her die in order to save her. I’m like Abraham with Isaac, willing to sacrifice the one I love above all others. Like Abraham, I lowered the knife—or car, in my case—but God spared my beloved one. Now, I am waiting, hoping, praying for a reward for my faithfulness.

I’m praying that her acceptance will be my reward.

As I approach the metal detector at the hospital, I wrap my arm around the large arrangement of flowers as I fish out my wallet with my other hand. I don’t have an ID in it, but I brought an empty one so as not to draw attention. I drop it and my clipboard into the bin, and then I step through the arch with the flowers. The guard barely looks at me.

I look a little older than I am, and with the scruffy facial hair and hat, the guard probably assumes I’m in my early twenties. He sees the flowers and uniform, and he fills in the rest of the facts to match the image. It’s enough for him to shift his attention to the next person. I gather my items and keep moving.

The flowers aren’t ostentatious, but they’re still large enough to be believable as a gift from the paper. My clothes are nondescript enough—black trousers, navy button-up, and a navy-and-white ball cap. My shoes are plain black, too. Nothing here stands out. Still, I tug the ball cap down a bit farther to shade my face and hold the floral arrangement up and to the side. I stopped in earlier to get a look around the lobby. A camera aims at the door, and another sits in the back far corner of the ceiling behind the reception desk.

A bored woman glances up as I approach the desk.

“Pediatrics,” I say.

“Fourth floor.” She motions toward the elevators.

A second security guard stands nearby, but he’s not here to stop deliveries. Being the intersection of the east–west I-40 and north–south I-85, Durham has long been a high drug-trafficking area. It’s not as bad as it once was, but the hospitals have security due to drug-related crimes.

Inside the elevator, I look at the flowers. We talked about the language of flowers in one of our lit classes because of Hamlet, so I know that Eva will figure it out. The flowers I picked are yellow roses (for apology and a broken heart), white roses (for silence and purity), red carnations (for passion), and white daisies (for innocence). The daisies were in Hamlet too, so I know she’ll see them as a clue. She’ll figure it out.

I’ve already removed the Harris Teeter grocery price tag, but I check again to be sure there are no other identifying marks that will ruin my disguise. I keep my eyes downcast in case there’s a camera in here, too. By the time I reach the fourth floor, where Eva is, my hands are trembling a little, not noticeably enough that strangers would see, but I feel it. Intentionally, I step on the long piece of my shoelace as I walk, untying it as I approach the desk. I tied and retied it repeatedly to get the length right. I’d practiced as I walked around at home, too. Today, I’m doing everything right. Today, I’m not going to get impatient. It’s hard though. I didn’t think I’d ever see her again—aside from her funeral. I knew what I’d say there. I’d planned it. The words, the pauses, I practiced. I may change it some now that I have more time.

Maybe I won’t have to say the words at all.

When I saw the article, when I found out she was alive, I knew it was a sign. God doesn’t want her to die yet. I understand that now. I was hasty. I have spent the past three days thinking about the right path, praying for clarity and considering my options. He’s giving me another chance, giving her another chance. Maybe I can make her see, and she can be redeemed. If I save her, she can live, and she’ll be so grateful for all that I’ve done to save her.

I stop at the desk and tell the receptionist, “Delivery for”—I glance at the clipboard as if I don’t know her name, as if I could ever forget her name, and read it—“Eva Tilling.”

“That girl gets more flowers than the rest of the floor combined!” the woman says as she signs on the clipboard where I silently indicate. The sheet is very convincing. I ordered my own flowers so I could have a good model for my form.

Once she walks away, I glance at my shoe as if I am just now seeing that it’s untied. No one seems to be watching, but you never know. I crouch, my posture allowing me to use my hat to hide my face as I watch her carry the flowers to a room. She taps on a door, and I finish tying the shoe as I watch her go inside.

Straightening, I glance around. No one pays much mind to delivery people. So many flowers arrive at the hospital. Why would they look at us?

I force myself not to hurry. We wouldn’t be in this situation if I had practiced patience in the first place. Hurrying is dangerous. Slow and steady wins the race, especially in the South. My grandmother told me that so often that I’m sure she’d take a switch to me if she knew that I’d messed everything up by being impatient.

I glance inside Eva’s room as I pass it. It’s only a moment, a split second, but she’s there. She’s awake and speaking softly. If I didn’t know better, I’d swear she was an angel. She’s not though. She’s one of Them. If I can’t save her, she’ll have to die. She’s been spared for now, but I need her to understand. If she doesn’t, she’ll be a sacrifice at the altar of venality.

Like the rest of Them should be.

My mouth is dry at the thought of how close I am to her now. I could walk straight into her room and visit her, but I’m not ready to talk to her. Still, I needed to see her.

I wonder if she’ll notice my name on the card. I listed several names—the editor, a few staff writers, and then I added my own in the middle. Judge. It’s not the name I was born with but it’s my true name, my soul name. I’m not really an executioner yet, and without Eva, I’m not a jury. Together, we could be a judge, jury, and executioner.

I’d despaired when I realized that she was one of Them. On the night I tried to kill her, I thought I would be always solitary. Now that she survived, I have hope again.

Outside, I pause to breathe the already thick air. Early summer in North Carolina isn’t as humid as the heat of July and August, but the air is heavy already. The sweet taste of wisteria fills my mouth, and I wonder if Eva likes the flowers. They’re not as sweet as the pale purple clusters of wisteria clinging to the trees. For her, I brought common flowers—like her, not truly special. That was my mistake before: I raised her up like a false idol. I know better now.

I cross the parking lot to the car I have today and slip on my gloves before I touch the handle. Like my uniform, it’s not memorable, a dark blue, four-door sedan. I’ll park it beside the one that has Eva’s blood on it.

DAY 5: “THE DETECTIVE” (#ulink_70d81fb8-d890-5938-8476-b8ff46ae7bdf)

Eva (#ulink_70d81fb8-d890-5938-8476-b8ff46ae7bdf)

I’M ALONE. SO FAR, my friends are respecting my “no visitors” stance, and my parents are still stuck in Europe. Apparently, there was another volcanic eruption in Iceland that pretty much shut down all the flights in and out of Europe. It was nothing but smoke, ash, and gas, but Dad explained that when that same thing happened back in 2010, flights were cancelled or disrupted for over a week. I’m not counting on them getting here anytime soon. I don’t need them to rush home anyhow. I’ve told them that several times. I told Grandfather Cooper the same thing when he called from somewhere in Alaska on one of his cruise-tour things.

Grandfather Tilling came by the hospital to sit with me, and of course, he had his congregation pray for me. It didn’t occur to me to ask him or Mrs. Yeung to be here for the police visit I’m about to have.

Right now, I wish it had.

“Are you sure you’re ready to talk to the detective, Eva?” my nurse asks again.

“Yeah.” I offer the nurse a smile, but I’m not sure if it’s encouraging with the way my cuts and bruises must still look.

“If it gets too much, you can stop the interview,” the nurse says kindly.

My nurse helps me to sit up, and maybe’s it’s silly, but I have her get my brush so I can combat some of the snarls. I don’t use a mirror because I can’t stand seeing my own reflection. I’m not sure I ever want to see my face again. I certainly don’t want my friends to see it. I’d like to cling to the image in my memory, not replace it with this one. Without a mirror, I can’t put on even the little bit of makeup I might be allowed, so there’s nothing to be done for my face.

When the police officer comes into the room, she looks at me the same way she looks at everything else: like she’s taking mental notes. I realize that she’s the first person other than Grace, Mrs. Yeung, and the hospital staff to see my face. I’m glad the detective isn’t gawking at me.

“Hi,” I say because I’m not sure what else to say. I’ve never been interviewed by a police officer before. I’d rather deal with the doctors than talk to the police.

“I’m Detective Grant,” she says. Her hair is pulled tightly back in a knot, but it only makes her features more noticeable. She wears no makeup, but her skin is enviably perfect. I realize that I wouldn’t have envied it before the accident, but now I’m looking at her and can’t help thinking that no one will ever again look at me the way I’m studying her right now.

She holds out a business card as she introduces herself, and then drops it on the stand beside my bed between my lip balm and iPhone. “I’m going to record our talk so I don’t miss anything,” she starts. Once I nod, she turns on the recorder and continues, “Why don’t you tell me what happened?”

“I don’t remember much,” I admit, feeling embarrassed at not knowing the details of what is probably the most significant thing that’s ever happened to me.

She sits in the chair beside my bed. “Tell me what you do remember.”

“I was walking home right after sunset, so it was still sort of light out.” I feel idiotic as I try to explain what little I know. “My boyfriend wasn’t answering, and I didn’t want to bother my friends, and my parents were away, and really, I’ve walked home plenty of times.”

“Did you see the vehicle?”

I think about it again. Dr. Klosky says it’s normal for there to be memory issues with head trauma, but that doesn’t do much to make me feel okay with it.

“I don’t know,” I admit.

She nods. “Were you walking on the side of the road? Were you wearing something visible?”

I try again to think back to that day, but the details aren’t there. “I always walk on the shoulder,” I say, sounding slightly desperate even to myself. “I don’t remember, but I can’t think of any reason I wouldn’t do the same things I always do … Did they find me on the side of the road?”

“Yes. The driver who found you didn’t see a car at the scene, but you were visible from the road.”

I swallow. I was visible. It was dusk. Someone hit me and left me. As the facts and her tone register, it finally occurs to me that this might not have been an accident. The monitor that keeps track of my heart rate and blood pressure beeps. We both glance at it. I’m not sure what the numbers are supposed to be, but I know they’re increasing.

My nurse today, whose name I can’t remember, pops into the room and glares at Detective Grant. She does something with the monitor, and the beeping stops. “Do you need to rest, Eva?”

I suspect Detective Grant and I both hear the real question: does this police officer need to go away? It’s not the detective’s fault I’m upset, so I shake my head. “I’m okay.”

“Do you want me to stay?” she offers.

“No. I’m okay.” It’s funny how we lie to be polite even when the evidence is present to contradict us. The monitor’s recent beeping makes it very apparent that I’m not fine.

“I’ll be back to check on you shortly,” the nurse says, sounding a lot like she’s warning us.

Once she’s gone, I look back at Detective Grant. “I get where you’re going, but no one would want to hurt me. I’m not bullied or a bully. It just doesn’t make sense. This had to be an accident.”

“What about your social life? Has anything happened recently to cause waves? Any rivalries?”

I shake my head. “I don’t do sports or clubs or anything. My boyfriend’s on the basketball team, and my best friend does track. No enemies or dramas related to either of them … or anyone else really. My life is pretty routine.”

“What about your family? Are you aware of your parents having any unusual upheavals or strange events? Threats? Anything at all that’s stood out to you.” She has one of the least readable faces I’ve seen, and her tone is level.

The questions still unnerve me, and the monitor starts beeping again. I don’t need to look at it to know that my pulse is speeding. “Do you have a reason to think it wasn’t an accident?” I ask.

My nurse comes back in. She folds her arms over her chest and levels a stern gaze at Detective Grant, who stands but doesn’t answer me.

I look up at her. “I wish I could be more helpful. I just don’t know anything. I remember walking, and I remember being here. Things in between are just fuzzy.”

The detective nods. “Dr. Klosky spoke to me about your condition. He also said you’re improving, so as you heal, you may remember more.”

“I want to,” I stress. “If I knew who did this to me … I’d tell you. I swear I would. They left me there. I could’ve—” I cut myself off before saying the d-word and shove that thought in a box. I didn’t die, and I’m not going to die. My brain is healing, and my body is healing. Everything is going to be fine.

Detective Grant slides her hands down her already wrinkle-free trousers as if to straighten them. “If you remember anything, tell the nurses. They know how to reach me.” She points at her business card. “So do you.”

Once I’m alone again, my nurse satisfied that I’m calm and going to be resting, I think about what Detective Grant said. I can’t think of anyone who wants to hurt me—or any reason why someone would want to kill me. What seems far more likely is that someone wasn’t paying attention, hit me, panicked, and fled. Making a stupid decision in the moment seems infinitely more probable than murder. Maybe the driver is even out there feeling guilty.

It had to have been an accident. The alternative is too overwhelming to consider.

DAY 6: “THE PIPER-ETTES” (#ulink_e6880148-00bc-5508-80fd-d9e2a899b3fd)

Grace (#ulink_e6880148-00bc-5508-80fd-d9e2a899b3fd)

“HOW IS SHE?”

“Do you know when she’ll be back?”

The questions start the moment I walk into Jessup High School the next day. It’s not that they’re unexpected. Jessup has about twenty thousand people, which means that there are only two hundred or so students in my grade, which means they all have known one another since they were in preschool. Eva’s family is the biggest employer in Jessup. Although the Cooper Winery itself doesn’t have a huge staff, many of the businesses here are partially owned by the Coopers. They’re the modern equivalents of aristocracy. Added to that, Eva’s father is a minister’s son, so the combination of Cooper wealth and Tilling modesty makes Eva a veritable princess here.

“How is she?” Piper Kennelly follows me through the hall. Behind her are three of the “Piper-ettes,” the seemingly interchangeable girls who are vying for her attention or Eva’s. They stand silent but attentive. Much like Eva’s, Piper’s opinion matters.

“Awake. She’s awake and through surgery. She’s doing much, much better.”

“I’m so glad!” Piper hugs me then, which is unexpected. I realize, though, that this is about Eva. I’m the only one allowed to visit her right now, so my status with Piper and her ilk just increased.

The bulk of the day goes a lot like that. It seems like everyone who sees me asks about Eva. People who are typically nice but not friendly to me are suddenly at my side like we’re old friends. I almost hate them for their transparency.

“Tell Eva we asked after her,” another girl calls out as I walk into my second-to-last-period course. I debate pointing out that I’m not Eva’s servant, governess, or any other Southern cliché. I’ve learned though that such remarks tend to be the equivalent of fingernails on a chalkboard here, so I wave over my shoulder, hoping to keep a smile in place, and head into lit class.

In Jessup, American Lit focuses most of the attention on only one part of the country, and as much as I can appreciate Flannery O’Connor and William Faulkner, I’m pretty sure that there are giants in the field we’re skipping—giants whose works would probably be useful to know before college. Thankfully, I can order critical editions online and study up on those. I’m not sure that Mr. Ellsworth would be much use with non-Southern lit anyhow.

I shake my head and glance at reason number two that I dread this class. Slouching in the back row is Robert Baucom. Eva’s boyfriend of the past year is the epitome of everything I think is wrong with Jessup. His family, much like Eva’s, is one of the first families of Jessup. He wears the clothes that speak of money and status, and he’ll only date the kind of girls who can trace their pedigrees back to The War. If you told me—before I came here—that there were still places where social class and ancestry mattered this much, I probably would’ve laughed. Heritage, however, is no laughing matter in Jessup.

Despite my general loathing of Robert, I walk to the back of the room to try to talk to him. He’s watching me approach with a flicker of nervousness on his face. He does that a lot, as if I’m a bug and he’d like to study me, but only once I’m safely under a jar. It stopped being creepy a while ago, but it’s still irritating as hell.

He knows I’ve been opposed to Eva dating him, and although we’ve reached an uneasy truce, we’re both very aware of the other’s disdain.

“Robert.”

He nods in lieu of replying. It’s going to be one of those conversations apparently. Without Eva here to remind him that I’m not “the help,” he tends to act like a dismissive jerk when he has an audience. At Jessup High, Robert always has an audience.

I ignore the curious gazes of the people on either side of him. Reid Benson and Jamie Hall exchange one of the looks that passes for conversation among this crowd, and Grayson Lane simply stares at me. Reid and Jamie are about the most vulgar boys I’ve met in Jessup. Around here, it passes for charm with half the school, or maybe it’s their names that pass as charm, and the vulgarity is just overlooked because of it.

I smother a sigh and try again to talk to Robert. “I don’t know when you plan to see Eva, but I thought we could check our schedules to make sure we don’t overlap.”

Robert shrugs. “I’m not sure. I have exams and things, and she isn’t allowed visitors.” He knows as well as I do that if he wanted to go Eva would see him.

“Seriously?”

He doesn’t reply or look at me, instead busying himself flipping the pages in his book as if he’s searching for a passage.

Reid coughs like he’s hiding a laugh. I flip him off but don’t look away from Robert. I force a smile and step closer. “Robert?”

He looks up.

“She could’ve died.”

For a moment, he’s silent. He seems to be weighing his thoughts, and I hope that he’ll do the right thing. His friends, Eva’s friends, are watching. No one is laughing now. The thought of the Tilling-Cooper scion dying is never going to be funny in Jessup, not even for a moment while a bunch of boys try to prove they’re smart-asses.

“How is she? Really?” he asks.

“She’s recovering, but she’s lonely and upset. You visiting would help.” I want to believe there’s some good in Robert. I hope he’ll show me that now.

Instead, he looks down at his book again and says, “I’ll text her tonight.”

And my good intentions about not arguing with him slip a little. “She deserves better.”

Reid shoots me a quick secretive smile, but Robert and the other two boys are all ignoring me now. Despite being so crude, Reid usually seems like he’s trying to be nice to me. He also seems increasingly convinced that he can charm me out of my clothes.

Reid doesn’t even pretend he’s interested in dating. As he so bluntly put it late one night after everyone had either passed out, left, or retreated behind closed doors, “My grandmother would have to mainline Xanax before she’d allow me to date a non-Southern girl … especially an Asian one.” I couldn’t decide whether to give him points for honesty or slap him for being an imbecile.

Mr. Ellsworth walks into the room, so I go to my seat. Listening to him drone on about the exam schedule is almost soothing. I don’t understand a lot of Eva’s friends or her boyfriend. Half the school seems desperate to let me know that they care about Eva—whether or not they do, I can’t honestly say—but her actual boyfriend seems just as determined to be clear that he isn’t going to worry about her. Part of me wants to stop and ask Reid to explain. He’s been friends with them since birth so he must have some sort of insight.

Understanding Robert’s idiocy won’t fix it though, so I settle for hoping that this is the thing that will convince Eva to end things with him. If not, I may end up going native and spouting things like “cad” and “reprobate.” If common sense won’t make her see that he’s a jerk, maybe some Jessup-isms will get it done.

DAY 6: “THE SURPRISE” (#ulink_3a87efcb-880a-5b70-807c-60a9838bc8bd)

Eva (#ulink_3a87efcb-880a-5b70-807c-60a9838bc8bd)

MY ROOM IS GETTING dangerously close to smelling like a perfume shop. Apparently my no-visitors lie was interpreted as an invitation to send arrangements. A few flowers are nice, but after a dozen or so bouquets the scent is nauseating. I blame the smell for giving me a headache and have the nurses give away all of them—except the orchids my parents sent. They called late last night—apparently after all these years they still can’t master time-zone math. They think they can finally get a flight out, so I guess they’ll be here soon—and I’ll go home. I guess it’s good. I’m already feeling caged.

I’m off the antiseizure drug, but I’m still on the muscle relaxer. I can even have narcotics too now that my brain seems okay. The doctors and nurses focus on my brain, my leg, and nerve damage. They tell me how lucky I am that I haven’t lost any sensation in my face. They tell me how fortunate I am to be awake and seemingly not experiencing any mental degradation. They’re right. I still asked them to hang a towel covering the mirror in the bathroom. The scars horrify me.

Robert still hasn’t visited. He should know that I don’t include him in my no-visitors request; Grace knew it didn’t apply to her. Robert hasn’t even asked to see me. Of course, I haven’t asked him to visit either. I’m afraid of what he’ll think. Although neither Grace nor my grandfather looked at me like I’m ugly, I’m not sure I want to see what Robert’s expression is when he sees my face. Status matters to Robert. He has only dated girls who are pretty and from what his mother calls “the right families.” My last name alone wasn’t reason enough for him; it would be for her, but he’s told me frequently that he likes the way I look. Maybe he’s hoping that if he waits, I’ll be prettier. I don’t want to tell him how wrong he is.

I realize, however, that it doesn’t make sense to flinch away from the nurses or the doctors when they do their rounds. They aren’t flinching away from me. Living in the hospital means having someone come into my room to poke, prod, or check on me every couple of hours all day and all night. They’re mostly nice people, trying to be quiet when I’m napping and not staring at the mess that’s now my face. I suspect it’s easier for them because they’ve seen worse—at least I hope they have.

It makes me feel like a lousy person for thinking that, and if my father heard me, there would be a lecture on “counting my blessings.”

I hate thinking about all of this, but there’s not a whole lot else to do in the hospital. I read. I watch television. I text Grace, Robert, Piper, CeCe, and a few other people. It’s lonely, but I can’t deal with most of them seeing me yet.

I don’t even want to see me yet.

My nurse today, Kelli, is cool. She was here yesterday, too. She’s the youngest nurse I’ve had, only a few years older than me, but she’s not so old that she has that parent-vibe.

“How about a change of scenery?” Kelli busies herself opening the curtains, letting bright light pour into the room. “You could get the grand tour of Peds.”

They aren’t letting me walk yet because of the traumatic brain injury, but I don’t want to walk either, so it works out just fine. “No thanks,” I say.

“You’re moping. It won’t help to hide away in a dark room.” Kelli levels a look at me that would do Grace proud. It’s the keen gaze of someone who isn’t going to accept my excuses or whining. I’m torn between smiling at it and wishing the day nurse was the one from two days ago. She didn’t care that I was wallowing.

“Be right back.” Kelli leaves, and when she returns, she’s pushing a wheelchair. “There’s a great view down in the lounge.”

“Maybe later,” I hedge.

Kelli crosses her arms over her chest and looks at me. “You’re one of three patients I have right now, and I just checked on them. Now’s a good time.”

“Fine. Give me the grand tour.”

I reach out to grab her arm, and she helps me as I turn my body ninety degrees on the bed so I can get down. Then, she steadies me as I lower my good leg to the floor. It takes longer than I think it should every time I do this, but at least I’m getting out of bed.

After Kelli helps me into the chair and hangs my IV bag on the pole, she quietly hands me a tissue. “Do you want something for the pain?”

“Nope.” It hurts more than I expected, but I’d rather hurt than feel like puking. The muscle relaxers already make me queasy, and I’m trying to avoid as much of the pain meds as I can. I dislike the oxycodone they added on what they call “PRN” dose, which, I learned, just means “take as needed.” As far as I’m concerned, it’s not needed at all. I tried it, but it made me feel fuzzy-brained. Even without it my tongue feels fat, and my brain feels slow.

Kelli hands me the lap blanket Mrs. Yeung brought me. It’s something she made herself, and I can tell that it’s one of her more recent attempts. The stitches in this one are more even than the others I’ve seen. After I cover my cast and my bare leg with the puce and lime blanket, Kelli wheels me out of the room. It feels a little strange to be in public wearing a blanket, pajamas, and a robe, but it’s either this or have someone bring me a skirt because jeans won’t go over my cast, and even if they did, balancing on one foot to unhook jeans when I need to use the bathroom sounds like a bad idea. So, a nightgown it is.

The floor is flooded by natural light because of skylights and large windows, and the walls are decorated with photographs of nature. Huge potted plants—that I think are probably fake—add to the overall sense that the designers were trying to bring a little of the world outside into the hospital. The common area has chairs and game stations, racks of books, and a few tables. It’s as inviting as it could be considering where we are.

“This is the playroom,” Kelli says as she points to the left. “Over here is the Teen Zone.”

I snort. I don’t mean to, but I do. Then I quickly say, “Sorry.”

“I didn’t name it.” She sounds unoffended, almost happy.

We’re quiet as she pushes me through the hallway. Most of the patients’ doors are closed. A few rooms are vacant, and a few have doors wide open with families visible inside. I try not to stare. I wouldn’t want strangers invading my privacy. There are a few different types of cribs, and I guess that means that there are different ages of babies in them. That makes me feel sadder. It sucks to be in the hospital, but at least I’m old enough to ask questions and make some sense of everything. Babies can’t do that.

Maybe Kelli senses my mood shifting or maybe she’s just used to people sinking into a funk when they have more cuts on their face than Frankenstein’s monster. Regardless of the reason, she starts talking again. “I hear that your friends can’t come during the week, right?”

“Jessup is a long drive.” I sound defensive, even though I try not to. I suspect that she already knows that I asked the desk to lie for me about the no-visitors policy.

“Maybe you can talk to some people here?” Kelli suggests.

I make a noncommittal noise because, truthfully, I’m simply not looking to make friends with the other patients.

Kelli wheels me past a kitchen and a laundry room, and then into a room that is a little bigger than the “Teen Zone.” There are a couple of sofas, a few chairs, a coffee table, and a decent-size television. It’s a slightly sterile version of the sort of living room that would be in most homes.

Another nurse comes around the corner. “You’re needed at the desk.”

“Do you want to go back or wait here?”

“Here.”

She smiles like I did something wonderful and then points at a panel that’s low enough to reach from a wheelchair. “There’s a call button if you need anything. I’ll be back, but page the desk if you’re ready to go back to your room sooner.”

I nod, and she leaves.

The window in the lounge overlooks a park. A group of about six people show up after I’ve been sitting there for a few minutes. They’re playing some sort of group Frisbee game. I watch them. That’s all I can do right now. It makes me feel pitiful, which pisses me off. God knows I’m not longing to chase a Frisbee. Sitting outside in the sunlight or taking a walk would be nice though. I can’t do either of those things. I’m not sure when or if I will ever be able to either.

My leg was apparently broken in several places. My thigh—the femur, according to Dr. Klosky—has a plate screwed onto it now. He explained it. In time the bone would grow over the metal. Better that than having shards floating about and lodging where they shouldn’t be; better a plate than not healing. Knowing all of that doesn’t erase the sense of queasiness that comes whenever I think about holes being drilled into my bone. I’m not even letting myself think about the possibility of lingering effects from my brain being jarred, or the swelling that went down, or the couple days unconscious. If I think about it, I’m not sure I can stop at a few tears. I’m not sure where to direct my anger, but I’m fighting my temper more and more lately. It twists in and around the sorrow and disgust.

Suddenly, being in the lounge isn’t as relaxing as it was supposed to be. I use my hands to push my chair closer to the call button, but before I reach it, I hear someone say my name.

“Eva?”

I look over my shoulder to see Nate staring at me in shock. I don’t know why he’s here at Mercy Regional Hospital or saying my name.

I stare at him as he steps farther into the room.

He drops onto the sofa across from me, careful to keep his distance from my extended leg, but near enough to talk without needing to be loud. “Hey.”

The urge to reach up and smooth down my hair makes me shake my head. My face is a maze of cuts and stitches, and I’m wearing my pajamas and one of the world’s least attractive blankets. My hair is the least of my issues.

“Hi,” I say and immediately realize that my conversation skills are about as bad as my fashion sense right now. Nate is talking to me after all this time. I’m not sure I’d know what to say to him even if we were somewhere normal. I certainly don’t know what to say here. I’m a little comforted that he doesn’t seem to know what to say either; he just nods and looks at me.

After an awkward moment during which I consider pushing the call button repeatedly so I can escape, he asks, “Did you just get here?”

“Here?”

“Mercy.” He stretches, tilting his head left and right as if he’s been sleeping in an uncomfortable position. “I’ve been in the lounge the past few evenings, and I haven’t seen you. Plus, those”—he points at my face—“look fresh.”

I’m more than a little confused that he’s not being a jerk like he has been for the past few years. I just don’t know if I should ignore him.

Cautiously, I say, “I’ve been in for a couple days. Someone hit me with a car.”

“That sucks.”

I start laughing. It’s not funny, not really, but it’s such an understatement after everything I’ve been feeling that it seems hilarious to me. He stares at me like maybe I’m a little unbalanced, which only makes me laugh more. It takes a minute to get my laughter under control. By then, tears fill my eyes.

I sniff and wipe the tears with the back of my hand, but in doing so, I bump one of the cuts on my cheek and gasp with pain.

“Shit,” Nate mutters, and he’s at my side holding out the box of tissues from the coffee table. “I didn’t mean to make you cry.”

“It still happens when I laugh—just like when we were kids.” My voice is shaky, more from pain than tears. I’m not completely lying: I do cry when I laugh.

“I’m sorry,” he says, his hand coming down on mine—and I’m … gone. I’m unable to speak. I feel the world around me vanish before I can ask whether he means that he’s sorry for the past three years or sorry that I’m in pain.

I pull over, my tires crunching on the gravel. I wasn’t drinking at all, but my vision is off. Something is wrong with me, and I’m afraid I won’t make it to the house. I guess it’s the flu or something, but I’ve never had the flu hit so suddenly.

My mother will be irritated when I wake her, but she’d be worse if I wrecked the truck.

I shiver as I get out of the truck.

With the help of the dashboard lights, I search the cab of my truck again, hoping that my phone fell out of my pocket and under the seat. The truck is clean enough that I know it’s not there, but I don’t see how it could be anywhere else. I had it earlier at the restaurant. I called Nora to talk to her and Aaron, but my brother was asleep, so I had Nora tell him I couldn’t make it until morning.

I feel out of it, tired enough that I worry that I’m coming down with something. I need to shake it off. I can’t carry germs to him. That’s the last thing he needs.

I wonder if I have any more of those germ masks at the house. I’m fairly certain I have gloves. Even if I feel better tomorrow, I’ll wear gloves and masks. Cystic fibrosis is hard enough for him to handle without adding colds or a flu.

“Eva?”

For a moment, I remember again that I’m not Nate. I’m Eva. Then the voice saying my name is swept away by a sharp pain in my stomach. Nate’s stomach. I think about how I’m Nate and not-Nate. My stomach—Eva’s stomach—shouldn’t hurt, but I’m swept further into Nate, and it’s all I can do to try to remember I’m not really him.

The stomach cramps become bad enough that I stumble and clutch the door frame of my truck. The pain is unexpected.

I pat my jeans pockets as if I would’ve missed my phone if it were there. It’s not there. I can’t call for help if my phone is gone.

My mouth feels like it’s filled with something hot and sour. I’m not throwing up. Yet. My heart feels too fast.

Someone pulls up in front of me, their headlights shining in my face so I can’t see who’s in the car. I’m not sure if it’s a helpful stranger or someone I know. There aren’t a lot of people who drive along Old Salem Road. Aside from a few houses and the reservoir, there’s nothing out this far. Mom always says that’s the only reason she’s willing to live at “the godforsaken end of the devil’s elbow.”

The lights make the person getting out of the car look like a silhouette. He’s not a huge man. I can tell that. Hecould be a bigger woman … I open my mouth to speak, but instead puke all over the seat of my truck. Something’s wrong. Something more than the flu.

“Sick,” I force out of lips that feel oddly numb.

The person from the car is beside me, but he—or she—isn’t speaking. I can see jeans and tennis shoes, but when I look up, I can’t see a face. It’s there; it has to be, but I can’t tell anything about it.

“You should’ve stayed away.” The voice sounds almost familiar, but the person is whispering.

I’m shivering so hard that my face hurts from clenching my jaw.

My legs are shaking too, and I hit the ground. I’m sitting in a puddle of vomit. The person opens a bottle of what looks like Mad Dog 20/20, grabs my chin with a gloved hand, and tilts my head back. The alcohol pours into my mouth faster than I can swallow, and it spills down my shirt.

He takes my hand and wraps it around the bottle, and my muscles are too weak to put up much of a fight. I try, but it’s about as effective as a toddler resisting a parent. My phone hits the asphalt beside me hard enough that the screen cracks. The stranger had my missing phone.

I try to turn my head so I can throw up on the ground instead of on myself, and the person helps me this time, turning my head so I can try to get whatever I ate out of my body. As soon as I’m done though, he puts the bottle back in my mouth. He gives me a break when I start gagging, but as soon as I’ve caught my breath, the bottle is back.

I need to get away. I need to get home. Then it hits me: I’m not going to be able to walk anywhere. I blink blearily at the silhouette crouched in front of me.

Then he helps me to the ground and puts the bottle to my lips.

“Your blood alcohol should be high enough that they won’t ask a lot of questions,” he or she says.

I feel like the world is spinning. I try to turn my head as the bottle comes back, but the person holds my chin again. This time when the Mad Dog gags me and the vomit comes at the same time, there is no break. Tears fill my already blurry eyes as I try to shake my head to get away, but it doesn’t work.

I’m still shaking my head, suddenly aware of Nate saying my name over and over. He sounds panicky.

I stare at him, and my eyes tear up. He’s looking down at me; he’s not choking or vomiting. What just happened? I’m not sure if it was a seizure or hallucination or what. All I know is that he looks fine, but I’m suddenly freezing.

Then Kelli is there, stepping in front of him.

“Eva?” She squats down in front of me, and I look at her as she asks, “Can you hear me? Nod if you hear me.”

I can’t stop shivering. I’m so cold that my teeth are chattering. I nod.

My gaze drifts back to Nate. He looks worried, and I want to say something that will let him know it’s not his fault that I … what? Envisioned his murder? I don’t remember hallucinations being on the list of things Dr. Klosky discussed.

“I don’t know what happened,” he tells Kelli. “She just blanked out and started shaking. I didn’t know what to do. With my brother, I know—” He cuts himself off with a shake of his head and turns to me. “I’m sorry if I did something.”

Kelli is taking my pulse. The feel of the latex gloves on my skin is still alien after over a week of it. I know now it’s for my safety and theirs—not all of my cuts are covered. It still makes me feel unsettled, like I’m in some bad movie about contagion. I’m sure I don’t have a zombie virus or bird flu or swine flu or whatever animal-named pandemic the next big outbreak will be.

“Is she okay?” Nate asks, drawing my gaze back to him. He’s somehow better-looking to me with that expression of concern on his face. The last time I saw him look at me that way was when I slid into second base in a game when we were in elementary school. I still have a small, faded scar on my knee from that day. It was stupid, but I’d watched a game with my granddad and it hadn’t looked painful when the players in the game did it.

“I’m fine,” I try to assure them both. I hope it reassures me too, but so far it’s not working. I feel incredibly unwell right now.

“Your pulse is good, and your pulse pressure is fine. Let’s get you back to the room to check your blood pressure and oximetry.” Kelli has that tone I’ve already come to identify as “something worries me but I won’t let the patient know.” Nate obviously recognizes it, too. He stares at Kelli a beat too long and then glances at me.

I sigh. There’s no way I can tell them what I thought I saw. I pictured Nate’s death. Clearly, my brain injury isn’t as healed as everyone thinks. My poor, battered brain caused me to hallucinate—and in a macabre way.

I pause when I realize I’ve started thinking of my brain as something separate from the rest of me and add that to the list of topics I’m not interested in pondering—or mentioning to anyone.

“What room?” Nate asks suddenly. He stares at me with the sort of intensity I’ve dreamed of seeing in his eyes—but for completely the wrong sort of reason.

I don’t answer.

Kelli looks between us before telling him, “Nurses can’t give that information out.”

I take the coward’s way out and stay silent. Right now I want to go to my nice, quiet room and try not to think of why I pictured him dying so vividly and awfully. I fake a yawn that turns into a real yawn, and Nate walks away without another word. That’s the Nate I’m used to these days, the one who abandons me, not the one who sounds like he cares.

Kelli is quiet as she pushes my wheelchair back to the room. She does the same things the nurses do every four hours: check my pupils’ reaction to light, my temperature, and my blood oxygen level. Everything is fine. She also checks my CSMs—color, sensation, and motility in my toes. Then, after she helps me up so I can use the toilet, she gets me settled back in my bed and piles several blankets on me since I’m still shivering. I think my quiet acceptance of her help makes her nervous, but I’m a little freaked out myself. In all of the things they’ve told me about TBI, there was nothing about horrible visions.

I was warned about less extreme issues like headaches, dizziness, ringing in the ears, and decreased sense of taste and smell. Then there are a whole slew of major worries, like issues with memory and speech, personality shifts, difficulty expressing and reading affect, and—one of my personal favorites—decreased coordination, because becoming clumsier is what every girl wants. Nowhere on the far too long list of things-that-can-go-wrong is vivid morbidity.

“Everything looks good, but I’m going to check in with the doctor on call to see what she wants to do.” She flashes me one of the fake smiles that are meant to be reassuring, and then she heads out to the desk.