Horse Under Water

Len Deighton

The dead hand of a long-defeated Nazi Third Reich reaches out to Portugal, London and Marrakech in Deighton’s second novel, featuring the same anonymous narrator and milieu of The IPCRESS File, but finds Dawlish now head of the secret British Intelligence unit, WOOC(P).The Ipcress File was a debut sensation. Here in the second Secret File, Horse under Water, skin-diving, drug trafficking and blackmail all feature in a curious story in which the dead hand of a long-defeated Hitler-Germany reaches out to Portugal, London and Marrakech, and to all the neo-Nazis of today's Europe.The detail is frightening but unfaultable; the story as up to date as ever it was. The un-named hero of The Ipcress File the same: insolent, fallible, capricious - in other words, human. But he must draw on all his abilities, good and bad, when plunged into a story of murder, betrayal and greed every bit as murky as the waters off the coast of Portugal, where the answers lie buried.

Cover designer’s note (#ud4d5103b-538c-5db3-b705-e1238fa9c861)

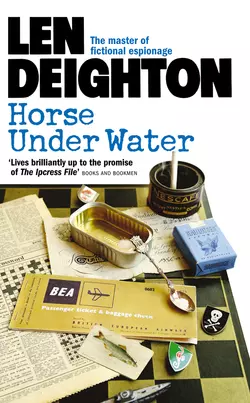

In creating cover designs for the new publication of Len Deighton’s quartet of spy novels, I came up with the metaphor of the chess game as it relates to the spy game. Three enamel U-boat sub-mariners’ cap badges became pawns on the chessboard.

A constant feature of Deighton’s nameless protagonist’s Charlotte Street WOOC(P) office was the ubiquitous pack of Gauloises cigarettes and the ever-present tin of Nescafé. (This very same street was used as the location for the HQ of the nest of spies in Alfred Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondent.) The Swiss had invented instant coffee prior to World War II, but it only became available in the UK in the 1950s, so when freeze-dried soluble grains were introduced a while later they became the beverage of choice for the Swinging London set. My search for a UK Nescafé tin of that period ended when I located one in far-off Australia!

Finding a contemporary, key-opened Portuguese sardine tin became virtually impossible. Discovering the illustration of a sardine on a cigarette card and a crested souvenir spoon from Lisbon became much easier, thanks to eBay!

My wife, Isolde, who produces all of my art work, and is a dab-hand at Photoshop, reproduced the period British European Airways ticket, incorporating the exact flight number described in the book.

One obsession of Deighton’s nameless protagonist is solving crossword puzzles. Since I have kept copies of the illustrations I produced for the London Sunday Times during the 1960s, I was able to find among the pages of the newspaper a crossword puzzle of the period.

The 1943 German postage stamp on the spine of the book depicts a German U-boat. The group of cigarette cards on the back of the cover spells out in semaphore K.U.Z.I.G. and Y. The nautical interpretation of these letters is referred to in the book as ‘Permission granted to lay alongside’.

Some years ago, given the possibility of producing a feature film on the subject of the Nazi plan to flood the Allied economy with counterfeit money, I purchased a fake £20 note.

On meeting a survivor of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp where, as an engraver, he was forced to produce the counterfeit bank notes, I showed him my note, which he held to the light and proudly proclaimed, ‘Yes, it’s one of ours!’

I photographed the jacket set-up using natural daylight, with my Canon OS 5D digital camera.

Arnold Schwartzman OBE RDI

LEN DEIGHTON

Horse Under Water

Copyright (#ud4d5103b-538c-5db3-b705-e1238fa9c861)

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape 1963

Copyright © Pluriform Publishing Company BV 1963

Introduction copyright © Pluriform Publishing Company BV 2009

Cover designer’s note © Arnold Schwartzman 2009

Cover design and photography © Arnold Schwartzman 2009

Len Deighton asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebook

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780586044315

Ebook Edition © MARCH 2015 ISBN: 9780007343010

Version: 2017-05-22

I cannot tell how the truth may be;

I say the tale as ’twas told to me.

SCOTT

Perhaps the worst plight of a vessel is to be caught in a gale on a lee shore. In this connection the following … rules should be observed:

1. Never allow your vessel to be found in such a predicament …

CALLINGHAM, Seamanship: Jottings for the Young Sailor

Contents

Cover (#uefa7b8e0-6807-54ca-b14d-d5534bab9b6c)

Cover designer’s note

Title Page (#u37daf404-251d-5834-a0b5-232065e55a81)

Copyright

Epigraph (#u6efb6c7c-989f-5c6a-a05f-2b9a2f2c4581)

Introduction

Solution

Horse Under Water: Secret File No. 2

1. Sweet talk

2. Old solution

3. Undersea need

4. Man with a tail

5. No toy

6. Ugly rock

7. Short talk

8. I hit it

9. I sit on it

10. Sort of boat

11. Help

12. Sort of man

13. More to do

14. Portuguese O.K.

15. Reaction in the market

16. One too many

17. Da Cunha lays it down

18. Sad song

19. Never say this

20. Enemy

21. Are the wages of this, that?

22. Charly raises its head

23. In the same one

24. Threads of a story

25. Ready to jump?

26. The point of a pen

27. Gain this or lose it

28. The boat gets one

29. Entreaty

30. Grave trouble

31. From a friend

32. For this game

33. Jean when I find her

34. Awakening

35. At the door

36. Sort of Secrets

37. Two readings

38. Chin wag

39. Inside a cabinet

40. H without an H

41. It’s moving

42. Hidden within treason

43. Friday on a Portuguese calendar

44. W.H.O. is part of this not me

45. Man and boy are this

46. Little else to give

47. Relinquish

48. Ivor Butcher entertains

49. And again

50. One named OSTRA has no number

51. Where I shine

52. I see better with this

53. Long arm

54. Ossie moves like double this

55. In me for a change

56. Deep signal

57. Lost letter in the mail

58. To put it together hastily

Last Word

Appendixes

Footnotes

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author

By Len Deighton

About the Publisher

Introduction (#ud4d5103b-538c-5db3-b705-e1238fa9c861)

The Ipcress File, my first book, was written in two separate sessions. It was started when I was on vacation in the South of France. Porquerolles is an island off Toulon. In those days there was very little to do there other than sit and look at the Mediterranean, and eat and drink at regular intervals. So I whiled away the sunny days writing a story.

I have always enjoyed being in France. As a moderately successful illustrator, I decided to live there. I had an energetic and encouraging artist’s agent in London and she sent work to me. My overheads were small, for the isolated cottage I lived in was Spartan accommodation for hunters. It was high on a windy hillside in the Dordogne and the forest that provided game for the hunters started within inches of the door. It had no heating other than a wood stove and drinking water was drawn from an ancient well about three hundred yards away. Day began with getting the stove started and going for water. Until the wood was burning bright, there could be no hot tea.

Rural life was enchanting but it was too good to last. Art directors of advertising agencies and magazines all preferred to deal with artists they could shout at in person. As the flow of illustration jobs diminished, I had more time for writing. But money diminished too and I reluctantly gave up my idyll and returned to London. (Not so long ago I went back to find the little cottage. It was still exactly as I remembered it but no smoke rose from the chimney. It was unoccupied and the windows were unwashed. I shed a tear and stole away.) But in those weeks of waiting for work to arrive I had continued writing the uncompleted story I had begun in Porquerolles. By the time I left for London, the story had become a book and it was more or less complete. But being almost broke I had no time for anything other than work. The manuscript of The Ipcress File was put on a shelf and forgotten until I met a literary agent at a party in London’s Swiss Cottage.

It was when The Ipcress File was accepted by a publisher that I took seriously the idea of writing books for a living. They were even talking about making a film of it. By that time I had done enough drawings to be solvent again, and with enough money to be on vacation in a dramatically situated, but somewhat shabby, cliff top apartment in Portugal. It was there on a balcony overlooking the Atlantic that I started scribbling in longhand the story that became my second book, Horse Under Water. In those days Southern Portugal was a remote region. There was no airport nearer than Lisbon and the journey from there to the south coast was gruelling. But it was worth it. The Algarve, on the very edge of Europe, is a pictorial region and I always delight in being there.

Many of the ideas in the book dated from earlier times. In the nineteen thirties, when I was a small child, my father had taken me to many museums but I particularly enjoyed the War Museum. To me the tanks, artillery pieces and aircraft were like gigantic toys and I have never lost my fascination with large examples of machinery.

So when I moved into the Elephant and Castle neighbourhood of London – where I lived for many years – the War Museum in Lambeth was within easy walking distance and it became a haunt of mine. It was a time when the Army, Navy and RAF, and many civilian agencies, began passing over to the War Museum books, films and documents that had become history rather than operational reference. A proportion of these items were technical ones seized from various German archives at the end of the war. I found it fascinating but the Museum found them an almost overwhelming burden.

In the final year of the war, there had been tremendous scientific advances in undersea warfare and I pursued these reports – British, American and German – with particular zeal. The War Museum’s librarian asked me to help by categorizing the material I examined, so that I became an unofficial member of the Museum staff. At the time, I had no idea that the notes I made would be used for anything other than my interest in history. It was during my stay in Portugal, when I was asking local people about German activity there during the war, that I recalled all that underwater warfare material. The book’s plot fell into place and I started writing.

Like The Ipcress File, this second book was started with a fountain pen and locally purchased school exercise book. I had not named the hero of The Ipcress File. A Canadian book-reviewer said it was symbolic and pretentious but in fact it was indecision. Now, writing a second book, I found it an advantage to have an anonymous hero. He might be the same man; or maybe not. I was able to make minor changes to him and his background. The changes had to be minor ones for the WOOC(P) office was still in Charlotte Street and Dawlish was still the hero’s ‘chief’. There were very few modifications but I realized that (although Deighton is a Yorkshire name, and I had lived briefly in the city of York) identifying him as a northerner would make demands on my knowledge that I could not sustain. It would be more sensible to give him a background closer to my own.

The indomitable Harry Saltzman, who had coproduced the James Bond films and was making The Ipcress File, solved everything with the sort of unhesitating practical move for which he was renowned. Michael Caine was cast to play the hero of that film and Michael was a Londoner, as I was.

He was named Harry Palmer. It was the right decision. Michael and the man of whom I’d written fused perfectly. I am indebted to Michael for the dimensions his skill and talent provided to my character. Having no underwater skills, knowledge or experience, I went to the Royal Navy and asked for help. Everyone at the Admiralty was one hundred per cent helpful. They sent me to the Royal Navy’s diving school and this experience is described here more or less as it happened. It was only when I was half-way through the course, and up to my neck in water on the ladder of the diving tank, that I confessed that I could not swim. They were shocked and apprehensive on my behalf but as I said: ‘What is the point of wearing all this scuba gear if you can manage without it?’ The chief instructor gave a grim smile and nodded me down into the water. Those were the days when you didn’t have to wonder why health and safety allowed the war to be won!

Len Deighton, 2009

Solution (#ud4d5103b-538c-5db3-b705-e1238fa9c861)

1 Parley

2 Nostrum

3 Air

4 Me

5 Pistol

6 Gib

7 Brief

8 Road

9 Gun

10 U

11 Aid

12 Frog

13 Read

14 Sim

15 Um

16 Bills

17 Lore

18 Fado

19 Die

20 Foe

21 Sin

22 Sex

23 Boat

24 Yarn

25 Yes

26 Ball

27 All

28 Tip

29 Pray

30 Entreaty

31 Aid

32 Old

33 Nods

34 Rude

35 Guard

36 Black

37 Reread

38 Gas

39 D.D.

40 A.I.T.C.

41 Film

42 Reason

43 Sex

44 UNO

45 Deep

46 Life

47 Forgo

48 Sings

49 Echo

50 File

51 Shoes

52 Set

53 Baix

54 Yo

55 Jam

56 Beep

57 Ail

58 Tack

Horse Under Water (#ud4d5103b-538c-5db3-b705-e1238fa9c861)

1 Sweet talk (#ulink_4bfdb7e1-9fa7-52d4-8676-d799c4a79f31)

Marrakech: Tuesday

Marrakech is just what the guide-books say it is. Marrakech is an ancient walled city surrounded with olive groves and palm trees. Behind it rise the mountains of the high Atlas and in the city the market place at Djemaa-el-Fna is alive with jugglers, dancers, magicians, story-tellers, snake-charmers and music. Marrakech is a fairy-tale city, but on this trip I didn’t get to see much more of it than a fly-blown hotel room and the immobile faces of three Portuguese politicians.

My hotel was in the old city; the Medina. The rooms were finished in brown and cream paint and the wall decorations were notices telling me not to do various things in French. From the next room came the sound of water dripping into the stained bath tub and the call of an indefatigable cricket, while through the broken fly-screens in the window came the musical sound of an Arab city selling its wares.

I removed my tie and put it over the back of my chair. My shirt hung suddenly cold against the small of my back and I felt a dribble of sweat run gently down the side of my nose, hesitate and drop on to ‘Sheet 128: Transfer of sterling assets of Government of Portugal held in United Kingdom, Mandates or Dependencies to successor Government’.

We sipped oversweet mint tea, munched almond, honeysticky cakes, and I took comfort in the idea of being back in London inside twenty-four hours. This may be a millionaire’s playground, but no self-respecting millionaire would be seen dead here in the summer. It was ten past four in the afternoon. The whole town was buzzing with flies and conversation; cafés, restaurants and brothels had standing room only; the pickpockets were working to rota.

‘Very well,’ I said, ‘availability of thirty per cent of your sterling assets as soon as the British Ambassador in Lisbon is satisfied that you have a working control within the capital.’ They agreed to that. They weren’t delirious with joy but they agreed to that. They were hard bargainers, these revolutionaries.

2 Old solution (#ulink_daef5999-4b50-546f-9111-354752778800)

London: Thursday

The W.O.O.C.(P) owned a small piece of grimy real estate on the unwashed side of Charlotte Street. My office had an outlook like a Cruikshank illustration to David Copperfield, and subsidence provided an isosceles triangle under the door that made internal telephones unnecessary.

Dawlish was my chief. When I gave him the report on my negotiations in Marrakech he laid it on his desk like the foundation stone of the National Theatre and said, ‘Foreign Office are going to introduce a couple of new ideas for tackling the talks with the Portuguese revolutionary party.’

‘For us to tackle them,’ I corrected.

‘Top marks, my boy,’ said Dawlish, ‘you cottoned on to that aspect of their little scheme.’

‘I’m covered in the scar tissue of O’Brien’s good ideas.’

‘Well, this one is better than most,’ said Dawlish.

Dawlish was a tall, grey-haired civil servant with eyes like the far end of a long tunnel. Dawlish always tended to placate other departments when they asked us to do something difficult or stupid. I saw each job in terms of the people who would have to do the dirty work. That’s the way I saw this job, but Dawlish was my master.

On the small, antique writing-desk that Dawlish had brought with him when he took over the department – W.O.O.C.(P) – was a bundle of papers tied with the pink ribbon of officialdom. He riffled quickly through them. ‘This Portuguese revolutionary movement …’ Dawlish began; he paused.

‘Vós não vedes,’ I supplied.

‘Yes, V.N.V. – that’s “they do not see”, isn’t it?’

‘“Vós” is the same as “vous” in French,’ I said; ‘it’s “you do not see”.’

‘Quite so,’ said Dawlish, ‘well this V.N.V. want the F.O. to put up quite a lump sum of money in advance.’

‘Yes,’ I said, ‘that’s the trouble with easy payment plans.’

Dawlish said, ‘Suppose we could do it for nothing.’ I didn’t answer. He went on, ‘Off the coast of Portugal there is a boat full of money. It’s money that the Nazis counterfeited during the war. English and American paper money.’

I said, ‘Then the idea is that the V.N.V. boys get the money from the sunken boat and use it to finance their revolution?’

‘Not quite,’ said Dawlish. He probed the hot pipe-embers with a match. ‘The idea is that we get the money from the sunken boat for them.’

‘Oh no!’ I said. ‘You surely haven’t agreed to that. What do F.O. Intelligence Unit

get paid for?’

‘I sometimes wonder,’ agreed Dawlish, ‘but I suppose the F.O. have their troubles too.’

‘Don’t tell me about them,’ I said, ‘it might break me up emotionally.’

Dawlish nodded, removed his spectacles and dabbed at his dark eye-sockets with a crisp handkerchief. Behind him on the window ledge the sun was rolling dusty documents into brandy snaps.

In the street below a man with a twin horn was dissatisfied with the existing disposition of traffic.

‘V.N.V. say that off the Portuguese coast there is a wrecked ship.’

Dawlish could never tell you anything without drawing a diagram. He drew a small formalized ship on the notepad with a gold pencil. ‘It was a German naval vessel en route to South America in March 1945. Inside it there is a considerable amount of excellent counterfeit currency, sterling five-pound notes, fifty-dollar bills and some genuine Swedish stuff. It was for high-ranking Nazis seeking exile, of course.’ I said nothing. Dawlish dabbed his eyes and I heard the traffic outside begin to move again.

‘The V.N.V. want us to help them retrieve these items. For “help them retrieve” you can read “present them with”. F.O. see this as a way of supporting what they think is an inevitable change of power, without implicating us too deeply, or costing any money. Comment?’

I said, ‘You mean the Portuguese revolutionaries are to use the counterfeit U.S. money and the genuine Swedish stuff to buy guns and generally finance a political Paul Jones, but the English money they can’t use because the design of the fiver has been changed.’

‘Quite so,’ said Dawlish.

I said, ‘I’m cynical. Do you have the name of the ship, charted position of the wreck and German bills of lading from Admiralty Historical Department?’

‘Not yet,’ said Dawlish, ‘but I have confirmed that there have been a fair number of counterfeit fivers in that region. They may have come from a wreck. Also V.N.V. have a local fisherman who is confident about locating it.’

‘Item 2,’ I continued, ‘the idea is that we mount a subversive operation in Portugal, which is a dictatorship whichever side of the dispatch box you rest your feet. This in itself is a tricky enterprise, but we are going to do it, in cooperation with, or on behalf of, this group of citizens whose openly avowed aim it is to overthrow the government. This you tell me is going to cause H.M.G. less embarrassment than planting a few hundred thousand into a bank account for them.’

Dawlish pulled a face.

‘O.K.,’ I said, ‘so don’t let’s have any false ideas about motivation. It’s a way of saving money at a considerable risk – our risk. I can see the working of the P.S.T.’s

eager little mind. He is going to organize a revolution while the Americans have to finance it because there are so many counterfeit dollars turning up all over the world. But Treasury are wrong.’

Dawlish looked up sharply and began tapping his pencil on the desk diary. The twin horn had nearly reached Oxford Street. ‘You think so?’ he said.

‘I know so,’ I told him. ‘These Portuguese characters are tough guys. They have been around. They will get rid of the British stuff all right, then the Treasury will be all long faces and little pink memos.’

We sat in silence for a few minutes while Dawlish drew a choppy sea above his drawing of a boat. He swivelled his chair round so that he could see through the dingy windows, jutted his lower lip forward and beat it with his pencil. In between this he said ‘Ummm’ four times.

He turned his back to me and began to speak. ‘Six months ago O’Brien told me that he knew of one hundred and fifty experts on world currency. He said there were seven who knew all the answers about moving it, but when it came to moving and changing it illegally, O’Brien said that you would be his choice every time.’

‘I’m flattered,’ I said.

‘Perhaps,’ said Dawlish, who considered illegal talent a dubious virtue; ‘but Treasury may have second thoughts, if they know how strongly you are against it.’

‘Don’t sell tickets on the strength of it,’ I told him. ‘What F.S.T.

will pass up a chance of saving perhaps a million pounds sterling? He probably has the College of Heralds designing a coat of arms already.’

I was right. Within ten days I had a letter telling me to report to the R.N. Instructional Diving School (Shallow Dive Course No. 549) at H.M.S. Vernon. The F.S.T. was going to get an earldom and I would get an Admiralty diving certificate. As Dawlish said when I complained, ‘But you are the obvious choice, old boy.’ He inscribed the numeral ‘one’ on his notepad and said, ‘One, Lisbon 1940, many contacts, you speak a bit of the lingo. Two,’ he wrote ‘two’, ‘currency expert. Three,’ he wrote ‘three’, ‘you were in on the first contacts with the V.N.V. in Morocco last month.’

‘But do I have to go on this frogman course?’ I asked. ‘It will be wet and cold and it’ll all take place in the early hours of the morning.’

‘Physical comfort is just a state of mind, my boy, it will make you fighting fit; and besides,’ Dawlish leaned forward confidentially, ‘you’ll be in charge, you know, and you don’t want these blighters nipping below for a crafty smoke.’ Dawlish then uttered a curious polyphonic sound, rather high-pitched at first, ending in a vibrating palate and terminated by the distribution of tobacco ash throughout the room. I stared incredulously; Dawlish had laughed.

3 Undersea need (#ulink_fb5e30d3-c559-54fc-8ea5-092ad017588e)

There is a point on the A3 near Cosham at which the whole of Portsmouth Harbour comes suddenly into view. This expanse of inland water is a vast grey triangle pointing to the Solent. The edges are sharp serrated patterns of docks, jetties and hards enclosing the colourless water.

A penetrating drizzle had been leaking through the low cloud since I had joined the A3 at Kingston Vale about 6.45 a.m. Window display men were junking polystyrene Xmas trees and ordering gambolling lambs. On their way to work people were sneaking a look at shop windows to see how much their relatives had paid for the presents they had received.

The snow had been around a long time. Layer upon layer had crystallized and hardened into abstract shapes. Now it sat like a delinquent child glaring at passers-by and daring them to try moving it. The ground had absorbed so much cold that rain made a slippery layer on the ice. I slowed as crowds of factory and dockyard workers swarmed across the streets. I turned into the red-brick gate of H.M.S. Vernon. A rating stood there in oilskins that gleamed like patent leather. He waved me to a halt. I walked to the porch where half a dozen sailors in damp saggy raincoats sat huddled together, hands in pockets. From the brittle Tannoy came a message for the duty watch. I knocked at the counter.

A young rating looked up from the assorted parts of a bicycle bell that lay before him on the table.

‘Can I help you sir?’

‘Instructional Diving Section,’ I said.

He asked the operator for a number and sat, eye-glazed, waiting to be connected. On the notice board I read about the Q.M. of the watch being responsible for boilers when there were men in cells. Under it hung a copper bugle with highly polished dents. I signed into the visitors’ ledger ‘Time of arrival 08.05’, a drip of rain spattered on to the page. Inside the office were the highly polished lino and blancoed belts that go with military police systems everywhere in the world. A two-badge seaman took over the phone and clobbered the receiver rest a few times. A P.O. emerged, holding a brown enamel teapot. He looked at my Admiralty authority.

‘That’s all right – take him over to Diving.’ He disappeared still holding the teapot in both hands.

The rain hammered the concrete roadways and paths and large freshly painted ships’ figureheads dribbled pensively. The Instructional Diving Section was a barn-like building that echoed to the noise of metal drums being moved. Behind a wire screen was a hardboard counter and a muscular rating.

‘Course 549?’ he asked.

‘Yes,’ I said. He eyed my civilian raincoat doubtfully. Over the Tannoy came the clang of one bell in the forenoon watch. A tall one-stripe hooky exchanged a Gauloise cigarette for half a cup of dark brown tea and I warmed my hands on the enamel sides of the mug. I knew it would all take place in the early hours of the morning.

The grey winter light and wet fog crept through the tiny windows and illuminated the rigid lines of school desks, engraved with hearts, patterns, and initials. I looked around the classroom. At the other desks were quiet, smooth-faced N.O.s with carefully dirtied gold stripes wrapped around brushed blue worsted. They talked quietly together in a well-bred clubby sort of way. I found my cigarettes and lit up. Behind me someone was saying ‘… and the bedrooms will be all G-Plan too …’

‘Here we go,’ someone else said. The door clicked open. With a smooth legerdemain perfected amid the tyranny of gunrooms the class came to attention on half-smoked cigarettes.

The golden arm of a senior officer waved us back to relaxation and gave us some ‘team spirits’, some ‘work hard and play hards’ one ‘welcome aboard’ and then gave us Chief Petty Officer Edwards.

C.P.O. Edwards was a pink man. His face was the same shade all over, neither more pink at the lips nor less pink around the eye sockets. He clasped a pink right hand inside a pink left hand and thrust them floorwards as though trying to cope with an almost unmanageable weight. His hair was short and the colour of ‘tickler’ and he was anxious to find out how high he could lift his chin without losing sight of his class.

‘Seeing how this is an officers’ course some young gentlemen may feel that the due care and attention in respect of hours of commencement need not be observed. I would like to correct this impression right away. Late arrivals will not, repeat not, enter the classroom after the door is closed but will report to the Lieutenant-Commander’s office. Third door on the right down the corridor. Any questions. Right.’ There could be no questions.

On the lapel of C.P.O. Edwards’s serge jacket was a star, a diver’s helmet, a crown of red thread, and a small C. C.P.O. Edwards was a professional diver, an expert, a ‘Clearance Diver’. He walked to the rear of the class and put large cardboard boxes on each desk. ‘Don’t you dare touch till you are told to,’ he shouted to the young paymaster lieutenant in the front row, adding, some moments after, ‘sir.’ A couple of the officers grinned at each other but I didn’t see anyone start opening a box.

‘Right, have–your–notebooks–ready–and–I–don’t–want–anybody–asking–for–a–pencil,’ he said, probably for the thousandth time. ‘This is your kit, check it; sign for it. I don’t want anybody asking me for a spare hood. Look after your gear and it will look after you. Lose something and come and tell me about it and you know what I shall do? Do you, sir? Do you know what I will do?’ The Chief was talking to the officer with the G-Plan bedroom.

‘I’ll larf, sir, that’s what I will do; larf.’ The Chief gave no sign of laughing either now or at any future time: I thought for a moment that LARF was some strange nautical verb.

There are lots of different degrees of diving skill. The first dives are done with the divers on the end of a leash like a well-bred poodle taking a dip. At the end of three weeks we would be shallow-water divers – the lowest form of submarine life. We were training to be amateurs.

Any member of ship’s crew could volunteer for this course and become the one to do inverted pressups on the barnacles to discover a foreign limpet of destruction. Others might stay here at Vernon to shake off the leash of authority and swim alone in the dark sea as a Free Diver; but it was the Clearance Divers who spent long professional years to learn the whole box of tricks from copper helmet to rubber flippers. C.P.O. Edwards was such a man.

Finally we were allowed to open the big brown boxes while the C.P.O. sang the contents to us.

‘Combinations, blue woollen, one. That’s it, son. A blue woollen man knitted by an old maid. Frocks, white woollen, one. That’s it – I know it’s a roll-neck pullover but you sign for a Frock. I’m not responsible for Naval Nomenclature. Helmet, blue woollen, one. Keep your head warm – one of the first rules of diving. Right. Mittens, free flooding, one pair. Right. Neck ring, one. No, that’s your neck seal. A neck ring is metal.’ He made a clucking noise in the throat and walked across the room, in tacit protest at an appalling state of ignorance. ‘Right. Neck clamp, one. Metal, son, the thing that fits on your neck ring. Right. Neck seal, one. Well where did you put it? Look, he’s got it on his desk,’ then in a louder voice, ‘look after your gear, already you are mixing it all up. I’m telling you, the rating divers on the other course will pounce on you lot like a jaunty onto a Crown and Anchor game.’

By now everyone was examining the gear like kids on Christmas morning. There were the one-piece black rubber suits, with two-way stretch and tight-fitting wrists, and the belt and the undersea knife. By now the classroom looked like a war-surplus store.

‘Do we have the rest of the day off, chiefie?’ someone asked.

‘There’s a couple of things on the agenda,’ said C.P.O. Edwards. ‘Muster at the sick bay for a medical, half an hour with the recompression chamber and a quick dip into the tank for all of you.’

‘Today?’ said G-Plan. He looked out of the window; across the roads of the depot the rain was bouncing back up and making a thick pile carpet of wetness.

‘Yes, you’ll be snug and dry in the tank,’ said Edwards. ‘It’s no depth, son, do you the world of good. Next. Instruction period Two: (a) dealing with wet gear, (b) stowing wet gear and (c) underwater signals.’

‘We aren’t going to have much time for lunch,’ said G-Plan. The chief relished this moment. He smiled a calm old-fashioned smile.

‘Lunch will be served at the diving position, sir. ‘Hot coffee and sandwiches.’ There was a bustle of comment. ‘It’s better in the long run you’ll find,’ the Chief said to no one in particular. ‘You won’t be running up a lot of mess bills and if you are going to be divers it’s not a lot of good to you all that drinking at the wardroom bar.’

If one pressed flat against the wall, which I was learning to call a bulkhead, only a small portion of the heavy rain hit you. Behind us the Artificer Divers were welding and hammering at the benches. After we had been in the tank they would resume the same tasks under water. The diving tank was a grey-painted gasometer, reinforced with crisscross girders. Above us in a boiler suit ‘dhobied’ almost white was the tall one-stripe hooky. He called down to us, ‘Ready for number four.’

The sub-lieutenant with the G-Plan bedroom shuffled forward, awkward in the flippers. The wind cut a thin rasher of water from the top of the tank and slopped it over the side. It hit the concrete with a crack and splashed around our black rubber legs. Number four was at the top. The tall leading seaman mouthed instructions that were kicked aside by the wind and swept across the harbour. Number four nodded and began to descend the ladder into the tank.

I looked through one of the glass panels. It was the size of a large TV screen. The sea water inside was cloudy green and small flecks of animal and vegetable matter swayed in neutral buoyancy. I watched number four stumbling across the floor of the tank. The suit suddenly ejected a stream of bubbles from the relief valve on his left shoulder. He had allowed the counter-lung to build up too much pressure. In war time such a mistake could cause instant death. They were tricky to use, these oxygen sets, but skilfully operated no tell-tale bubbles ever reached the surface. The diver breathes in and out of the rubber bag using the same air over and over, topping it up with oxygen while absorbing the CO

by means of the absorbent canister. Number four was learning how to move under water now, leaning forward as though in a powerful headwind, but his over-inflated rubber lung had lifted him clear of the floor. He was almost horizontal before he had gripped the metal ladder. Now the sailor on the ladder tapped a signal and G-Plan began to haul himself upward.

Soon he was back under the leaky lean-to, dripping wet, smiling and wiping the back of his hand across his face before putting a cigarette in it. He drew on the fag and breathed out of an open mouth, revelling in the dirty warmth of the smoke. We awaited his verdict.

‘Nothing to it,’ he said. ‘My kid could do it.’

‘That officer there,’ the voice of C.P.O. Edwards came effortlessly along the whole length of the jetty, ‘neglecting his diving gear.’ The whole place sprang to life, the sibilant sound of fags being doused, equipment tidied and welding torches lit echoed around the hut.

‘Leading seaman Barker. Get these trainees on the ladder.’ Edwards’s sentences ended on an authoritative high note, and the leading hand almost toppled into the tank in his haste, as Edwards’s metal-tipped heels moved ever closer.

‘Number eight, please,’ said the leading seaman rather plaintively. Our numbers were painted across each and every metal part of the equipment. ‘Eight,’ I heard the hooky say again. I looked at my own absorbent canister. I was number eight. ‘The civilian officer, sir, who is always late.’ I was No. 8.

‘Nice and cosy’, the L.S. made sure the square wraparound mask was watertight, and the mouthpiece between my teeth, then gave me a gentle slap on the arm. Through the eyepiece everything was enlarged and I found difficulty in even locating the ladder’s top step. The water was dense and very cold. Only when one’s eyes descend below the waterline is one suddenly under water. A few large white bubbles sped upward past my eyes, escaping from the folds of the rubber suit. The water closed upon me like a green trapdoor and light shimmered and danced as the wind’s rough file tore notches in the smooth surface.

‘Wanch Wanch.’ The noise of the air rattling around the breathing bag was deafening. I touched the soft black rubber of the counter-lung across my chest, and, deciding it was too soft, turned the brass tap of the bypass. The compressed oxygen roared through the reducing valve and an explosion of white bubbles rushed past my left ear. Too much. It was tricky. Still listening to my breath I noticed that I was breathing faster just as the instructor said everyone did. I deliberately held my breath for a moment. Shallow breathing didn’t give the CO

absorbent enough time to do its job and could result in CO

poisoning, which in turn causes one to breathe shorter until intoxication, giddiness and blackout occur. I must stop even thinking about such things. By holding one’s breath the slight sound of the wind upon the water, the creak of the metal, and the noises of the people outside became audible. I went close to the vision panels. I felt the pressure of the water constricting my arms and legs. The rain still swept across the jetty. I breathed out, the air clattered like a bundle of firewood. Across the floor of the tank the light made patterns of green and white.

My right sock had wrinkled underfoot. I raised my leg and found I could lean forward on the water. I walked two steps but the density prevented me making progress. I bobbed. I leaned forward again and made a paddling motion. I noticed how clear my hands were. They and everything else around me had taken on a new interest and wonder. I studied the small scar on the palm of my right hand. It was like seeing a colour transparency of it. I looked up at the surface of the water and tried to guess how deep I was. It was difficult to judge shape, size or distance down here.

I wondered what the time was and walked back to the glass panel to try to see the dockyard clock. Two ‘art divers’ were standing in the way. I decided to ‘guff up’ again and gave the bypass valve a little twist. It was a better attempt and although I bounced a couple of feet off the bottom little or no air came out of the relief valve. The other trainees were making a lot of noise. The clatter of them around the tank competed with the noise of my breathing. It was the hooky tapping a spanner upon the top rung of the ladder. A signal for me to ascend. I remembered what Edwards had said; men become forgetful and complacent under water.

As my head broke the surface the light was dazzling and the reflections from the water almost painful to my eyes, which had adjusted to the gentle green underwater conditions. A hooter sounded somewhere across the harbour and I was suddenly aware of all the noisemakers. I dragged my heavy body and its three oxygen bottles out of the water. Down below G-Plan had a large medicine bottle. It contained rum. Watching until Edwards had gone across the jetty he passed it to me.

‘Gulpers,’ he said and I thanked him sincerely. The gentle warmth raced around my veins like a hot-rod Ford.

In the hut there were warm towels and dry clothing and C.P.O. Edwards. I could hear his voice while I dressed. ‘… practical working. Theory five: the physiology of diving and Artificial Respiration. Wednesday, Theory six: recognizing an under-charged set – it’s dangerous to risk an almost empty bottle – and then the practical at Horsea Island in the afternoon. Thursday: Symptoms of CO

poisoning, of Oxygen poisoning (or anoxia) – what the Navy call “Oxygen Pete”, of Air Embolism or what divers call “chokes”, of Decompression Sickness – what we call “staggers” but what you’ve probably heard them in films calling “bends”. And lastly Shallow Water Blackout – what the quack calls “syncope” just fainting really but it’s more frequent when you are on Oxygen.’

It made me feel like I’d just had all of them.

‘That leaves Friday,’ Edwards’s voice continued, ‘for a morning of diving and a simple revision and written test in the afternoon.’

G-Plan said, ‘We will have learnt it all by then, chief? What are you going to find us to do on Monday morning?’

‘Monday morning you start all over again,’ said Edwards. He stepped outside the door and raised his powerful voice. ‘They’re spending too much time on the ladder, Barker. They aren’t on the steps of the Prince Regent’s bathing machine.’ Then turning back into the hut again his voice lowered. ‘Yes, you’ll be starting all over again on Monday. Theory seven: Preparation and service of Swimmers’ Air Breathing Apparatus. That’s the aqua-lung works with a demand valve and compressed air – quite different to these oxygen sets. And by the way, Stewart,’ that was G-Plan’s name, ‘if the officer of the watch comes round, you’ll keep that medicine bottle of yours out of sight. I wouldn’t like him to think any of my divers were not well.’

‘Yes Chief,’ said Stewart. He had eyeballs in his buttons that Edwards.

4 Man with a tail (#ulink_a099f6ac-eda2-5541-b833-87ed04236842)

Some heavy lorries making smoke at Horndean, a sharp rainstorm rolling across Hindhead, grass as green as crème de menthe, and then bright sunshine as I came on to the Guildford by-pass. I watched my mirror, then tuned the radio to France III.

Putney Bridge and into King’s Road; shiny, shoddy and deep-frozen. Bald men with roll-neck pullovers. Girls with bee-swarm hair-dos and trousers that left nothing to the imagination. Left, up Beaufort Street, past the Forum cinema and on to Gloucester Road. Men with dirty driving gloves and clean copies of Autosport, and landladies weighed down with shillings from insatiable gas-meters. Left again, on to Cromwell Road Clearway. Now I was quite sure. The black Anglia was following me.

I turned again and pulled up by the phone box on the corner. The Anglia came past me slowly as I searched for a threepenny piece. I watched out of the corner of my eye until it stopped perhaps seventy yards up the one-way street, then I got quickly back into my car and backed around the corner on to Cromwell Road again. This left the black Anglia seventy yards up a one-way street. Now to see how efficient they were.

I drove on past Victorian terraces behind which unpainted bed-sitters crouched, pretending to be one grand imperial household instead of a molecular structure of colonial loneliness.

I stopped. From under the front passenger seat I reached for the 10 × 40 binoculars that I always store there. I wrapped a Statesman around them, locked the car and walked over to Jean’s flat. Number 23 had peach curtains and was a maze of corridors down which the draught got a running start at the ill-fitting doors. I let myself in.

A fan heater provided a background hum while Jean tinkled around the kitchen fixing a big jug of coffee. I watched her from the kitchen doorway. She was wearing a dark-brown woollen suit; her tan had not faded and the hair that hung across her deep forehead was still golden from the summer sun. She looked up; calm, clear and as still as a three-quarter-grain Nembutal.

She said, ‘Did you straighten out the Navy?’

‘You make me sound pragmatic,’ I said.

‘And it’s not true, is it?’ She poured the coffee into the big art-pottery cups. ‘You were followed here, you know.’

‘I don’t think so,’ I said quietly.

‘Don’t do that,’ said Jean.

‘What?’

‘You know very well. It’s your Oreste Pinto voice. You say things to provoke a fuller reply.’

‘All right. All right. Relax.’

‘You don’t have to tell …’

‘I was followed by a black Anglia, BGT 803, maybe all the way from Portsmouth, certainly from Hindhead. I’ve no idea who it is, but it could be the Electrolux company.’

‘Pay them,’ said Jean. She stood well back from the window still looking down towards the street. ‘They could be from the refrigerator company; one of them has an icepick in his hand.’

‘Very funny.’

‘You have a wide circle of friends. The gentlemen across the road feature an azure Bristol 407. It’s rather dreamy.’

‘You’re joking, of course.’

‘Come and see, child of Neptune.’

I walked to the window. There was a Bristol 407 of brilliant blue, sufficiently muddied to have done a fast journey down the A3. It was awkwardly parked amid the dense mortuary of vehicles in the street below. On the pavement a tall man in a flat peaked cap and short bold-patterned overcoat looked like a wealthy bookmaker. I focused the Zeiss and studied the two men and their car carefully.

I said, ‘They aren’t working for any department we know, judging from the tax bracket they’re in. Bristol 407 indeed.’

‘Do I detect a faint note of envy?’ asked Jean, taking the binoculars and looking down upon my would-be companions.

‘Yes,’ I said.

‘You wouldn’t join the enemies of democracy and threaten the existence of freedom-loving western capitalism for a Bristol 407, would you?’

‘What colour?’

Jean was looking out of the tall narrow window. ‘He’s getting back into it again. They are going to park outside 26.’ She turned back to me. ‘Do you think they are Special Branch?’

‘No: only West End Central cops have big cars.’

‘Do you think they’re friends?’

‘No, they wouldn’t let an overcoat like that through the front door of the H.O.’

Jean put down the field-glasses and poured out the coffee in silence.

‘Go on,’ I said, ‘there are plenty more security departments.’ Jean handed me the big cup of black coffee. I sniffed it. ‘It’s Continental roast.’

‘You like Continental roast, don’t you?’

‘Sometimes,’ I said.

‘What are you going to do?’

‘I’ll drink it.’

‘About the men.’

‘I’ll find out who they are.’

‘How?’ asked Jean.

‘Well, I shall go upstairs, climb out along the roofs, find another skylight, go down through the house. You, meanwhile, put on my overcoat and move about near the window so that they catch sight of what they think is me. At a prearranged time-lapse, say twenty minutes, you will go across and start up the engine of my VW. They will have to pull out the Bristol in order to have any chance of catching my car before it disappears. Got it?’

Jean said, ‘Yes,’ very slowly and doubtfully.

‘By that time I shall be in the porch of, say, Number 29. When they get their car started I will take a potato, which I shall have taken from your vegetable basket and, running forward, crouching very low, I shall jam the raw unpeeled potato on to their exhaust pipe and hold it there. It’s only a matter of moments before the pressure builds up enough to blow the cylinder head off with a tremendous crash.’ Jean giggled. ‘There they will be with an expensive disabled car. They will never get a taxi at this time of day at Gloucester Road cab rank, so they will have to ask for a lift in the VW, which by this time will have had the heater going long enough to make it warm and comfortable. On the way to wherever they wish to go I shall say – quite casually, mark you – “what are you two young fellows doing in this neck of the woods on a Saturday midday?” and from one thing and another I shall soon find out who they work for.’

Jean said, ‘It’s not had a good effect on you, that Naval Depot.’

I dialled the Ghost exchange number and switchboard answered. I put a hand over the mouthpiece while asking Jean, ‘What is the code word for the week-end?’

‘Fine pickle you’d be in without me,’ she said from the kitchen.

‘Don’t carp, girl. I haven’t been in to the office for a week.’

‘It’s “cherish”.’

‘Cherish,’ I said to the switchboard operator, and he connected me to the W.O.O.C.(P) duty officer, ‘Tinkle’ Bell.

‘Tinkle,’ I said, ‘cherish.’

‘Yes,’ said Tinkle. I heard the click of the recording machine being switched into the circuit. ‘Go ahead.’

‘I have a tail. Anything on W.M.?’ Tinkle went to look at the Weekly Memoranda sheets that came from the Joint Intelligence Agency at the Ministry of Defence. I heard Tinkle’s outsize brogue shoes pad lightly back to the desk. ‘Not a sausage, old boy.’

‘Do me a favour, Tinkle.’

‘Anything you say, old boy.’

‘You have someone you could leave in charge if you nipped down to Storey’s Gate for me?’

‘Certainly, old chap, pleasure.’

‘Thanks, Tinkle. I wouldn’t bother you on Saturday if it wasn’t important.’

‘Precisely, old boy. I know that.’

‘Go up to the third floor and see Mrs Welch – that’s W-e-l-c-h – and tell her you want one of the C-SICH

files. Any one. I tell you what, make it a file we’re already holding. You with me?’

‘Sinking fast, old boy.’

‘Ask her for some file we already have and she’ll tell you we already have it, but you say we haven’t. She will show you the receipt book. If she doesn’t offer to, raise hell and insist that she does. Get a good eyeful of all the receipt signatures down the right-hand column. What I want to know is who receipted file 20 W.O.O.C.(P) 287.’

‘That’s one of our personal dossiers,’ said Tinkle.

‘Mine, to be precise,’ I said. ‘If I know who’s handled my file lately I have a lead on who might be tailing me.’

‘Very crafty,’ said Tinkle.

‘And, Tinkle,’ I added, ‘I want a quick check on two car registrations, a black Anglia and a Bristol 407.’ I waited while Tinkle read back the numbers.

‘Thanks, Tinkle, and ring me back at Jean’s.’

Jean poured me a third cup of coffee and produced some pancakes with sugar and cream. ‘You are a bit careless on an open line, aren’t you?’ she said. ‘C-SICH and file numbers and all that.’

I said, ‘If anyone listening isn’t in the business it will be gibberish, and if they are, they were taught that stuff in Dzerzhinski Street.’

‘While you were on the phone your Anglia arrived.’

I walked to the window. Four men were talking, well down the road. Soon two of them got into the Bristol and drove away, but the Anglia remained outside.

Jean and I spent a lazy Saturday afternoon. She washed her hair and I made lots of coffee and read a back issue of the Observer. The TV was just saying ‘… a Blackfoot war party wouldn’t be using a medicine arrow, Betsy …’ when the phone rang.

‘It was the Director of Naval Intelligence,’ I said into the phone before he could speak.

‘Blimey,’ said Tinkle, ‘how did you know?’

‘I thought D.N.I. would screen a visiting civilian pretty thoroughly before letting him into their diving school.’

Tinkle said, ‘Well, good thinking, old boy. Central Register

and C-SICH both booked your files out to D.N.I. on September 1st.’

‘What about the car registrations, Tinkle?’

‘The Anglia belongs to a man named Butcher, initials I. H., and the Bristol to a Cabinet Minister named Smith. Know them?’

‘I’ve heard the names before. Perhaps you would do an S6 report on both of them and leave it in the locked “in” tray.’

‘O.K.,’ said Tinkle and rang off.

‘What did he say?’ Jean asked.

‘I’m riding shotgun on the noon stage,’ I said. Jean made a noise and continued to paint a finger-nail flame orange.

Finally I said, ‘The cars belong to a Cabinet Minister named Henry Smith and to a little thug named Butcher who does a cut-price service in commercial espionage on the “seduced secretary” system.’

‘What a lovely system,’ Jean said.

‘You haven’t seen Butcher,’ I said. ‘My file, incidentally, went to D.N.I. on September 1st.’

‘Butcher,’ Jean said. ‘Butcher. I know that name.’ She painted another nail. Suddenly she shouted, ‘The ice-melting report.’

What a memory she had. Butcher had sold us an old German laboratory report about a machine to melt ice at an amazing speed. ‘What can you remember of that report?’ I asked her.

‘I couldn’t understand it properly,’ she said, ‘but the rough idea was that by rearranging the molecular structure of ice it would instantaneously become water. Or vice versa. That’s something the Navy might be keen on now that there are missile submarines that have to find a hole in the polar ice-pack before they can fire them.’ She held her hand at arm’s distance and studied the orange nails for a minute.

‘Yes,’ I said, ‘Butcher had the report. Navy want the report … That’s the connexion. I’m a genius.’

‘Why are you a genius?’ Jean asked.

‘For getting myself a secretary like you,’ I said. Jean blew me a kiss.

‘What about Mr Smith the Cabinet Minister?’ Jean asked.

‘He’s just having his car borrowed,’ I said. But I wasn’t sure about that. I looked at Jean and stubbed out my cigarette.

‘My nails are still wet,’ Jean said, ‘you mustn’t.’

5 No toy (#ulink_6b21e970-27e6-5c71-ab2c-eaf613809596)

My two weeks at Portsmouth passed quickly and I came home with a small Admiralty shallow-water certificate suitable for framing, and incipient pneumonia, although Jean said it was a sore throat. Monday I stayed in bed all day. Tuesday was a cold bright morning in September that warned you that winter was all set to pounce.

A letter from the Admiralty arrived authorizing me to take possession of the R.N. underwater gear from the school and charged it to me! The same post brought me another bill for the repair of the refrigerator and a final demand for the rates. I nicked my chin while shaving and bled like I’d sprung a leak. I changed into another shirt and arrived at Charlotte Street to find Dawlish in a quiet rage because I had made him late for the Senior Intelligence Conference that takes place in that strange square room of the C.I.G.S. the first Tuesday in each month.

It was a terrible day and it hadn’t even begun yet. Dawlish went through all the rigmarole of my new assignment: radio code words and priorities for communicating with him.

‘I’ve persuaded them to give you the equivalent authority to Permanent Under-Secretary, so don’t let them down. It might be useful if you deal with Denning

or the Lisbon Embassy. You’ll remember that after last year they said they would never give us a rank above Assistant Secretary again.’

‘Big deal,’ I said, eyeing the papers on his desk. ‘P.U.S. and they send me on a Night Tourist aeroplane.’

‘All we could get,’ said Dawlish. ‘Don’t be so class-conscious, my boy, you don’t want us to demand that they off-load some unfortunate taxpayer; why, you’d have the whole of Gibraltar polishing its blanco – or whatever soldiers do.’

‘All right,’ I said. ‘All right, but you don’t have to be so bloody gay about it all.’

Dawlish turned over the next paper on his desk. ‘Equipment.’ Before he could read on I interrupted.

‘That’s another thing, they’ve put about two thousand quids’ worth of Admiralty equipment on my personal charge.’

‘Security, old chap, don’t want those career-mad Admiralty people to know all our little secrets.’

I nodded. ‘Look,’ I said, ‘I’ll need your signature if I am to draw a pistol from War Office armoury.’ There was a long silence, broken only by the sound of Dawlish blinking.

‘Pistol?’ said Dawlish. ‘Are you going out of your mind?’

‘Just into my second childhood,’ I said.

‘That’s right,’ said Dawlish, ‘they are nasty, noisy, dangerous toys. How would I feel if you jammed your finger in the mechanism or something?’

I picked up the air ticket and underwater-gear inventory and walked to the door.

‘West London 9.40,’ he said; ‘try to have the Strutton report ready before you leave, and …’ He removed his glasses and began to polish them carefully. ‘You have a pistol of your own that I am not supposed to know about. Don’t take it with you, there’s a good chap.’

‘Not a chance,’ I said, ‘I can’t afford the ammunition.’

That day I completed my report for the Cabinet on the Strutton Plan. The plan was to have a new espionage network of people feeding information back to London. All of them would be telephone, cable, telex operators or repair engineers working in embassies or foreign government departments. It meant setting up employment agencies abroad which would specialize in this type of employee. As well as describing the new idea my report had to outline the operations side, i.e. planning, communications, cut-outs,

post boxes

and a superimposed system

and, most important as far as the Cabinet report was concerned, costing.

Jean finished typing the report by 8.30 p.m. I locked it into the steel ‘out’ box, switched on the infra-red burglar-alarm system and set the special phone system to ‘record’. Next door was our telephone exchange: Ghost, used in the same way that the Government used Federal exchange. Anyone dialling one of our numbers by mistake heard about a minute and a half of the ‘number obtainable’ signal before it began ringing. After that the night operators next door challenged the caller, then our phone rang. There were advantages; I could for instance call a number on Ghost from any phone and have the operator connect me to anywhere in the world without attracting attention.

Jean put the typewriter ribbons into the safe. We said good night to George the night man and I put my tickets for B.E.A. 062 into my overcoat.

Jean told me about the carpet she’d bought for her flat and promised to fix me dinner when I returned. I told her not to leave the Strutton Plan report with O’Brien, suggested at least three different excuses she could give him, and promised to look out for a green suede jacket in Spain, size 36.

6 Ugly rock (#ulink_ab3ccea2-791e-5ba3-9e64-c3854dc4dae5)

The airport bus dredged through the sludge of traffic as sodium-arc lamps jaundiced our way towards Slough. Cold passengers clasped their five-shilling tickets and one or two tried to read newspapers in the glimmer. Cars flicked lights, shook their woolly dollies at us and flashed by, followed by ghost cars of white spray.

At the airport everything was closed and half the lighting switched off to save the cost of the electricity we had paid seven and six airport tax for. A long thin line of passengers shuffled down the centre of the draughty customs hall while Immigration men snapped passports in their faces with impartial xenophobia. In the lounge a blonde with smudged mascara played us a gay tune on her teeth with a ballpoint pen before we were sealed into the big, shiny, aluminium pod.

Sitting near the front of the aircraft was a plump man in a plastic raincoat. His red face was familiar to me and I tried to remember in what connexion. He was bellowing loudly about the air conditioning.

The surrounding airport was twittering with Klee-like coloured lights and signs. Inside the cabin the strongest had fought for and won their window seats, sick bags were ready and cabin temperature control set at ‘Roast’. Starters whined, dipped the cabin lights to half strength and heaved at the propeller blades. The big motors pounded the wet air, settled into a roar and dragged us up the black ramp of night.

The automatic pilot took control; white plastic cups danced and shuddered across the little stage clipped before me, shedding plastic spoons and large wrapped sugar segments.

I could see the back of the plump man’s head. He was shouting. I tried to remember everyone who had been involved in the ice-melting file transaction, and wondered if Dawlish had checked this passenger list.

Eight thousand feet. Beneath us green veins of street-lighting X-rayed Weymouth on to the night. Then only the dark sea.

Thin damp triangles of bread clung helpless across the pliable plate. I ate one. The steward poured hot coffee from the battered metal pots in appreciation. Constellations of city lights merged with icicles of stars suspended in the cavern of the sky.

I dozed until – Plonk Plonk – the undercarriage came down and cabin lighting was turned fully bright to open sleep-moted eyes. As the plane rumbled to a halt anxious holidaymakers clasped last year’s straw hats and groped towards the exit door.

‘Goodnightsirandthankyou … goodnightsirandthankyou … goodnightsirandthankyou …’ The stewardess bestowed a low communion upon departing passengers.

The plump man edged his way along the plane towards me. ‘Number 24,’ he said.

‘What?’ I said nervously.

‘You are number 24,’ he said loudly. ‘I never forget a face.’

‘Who are you?’ I asked.

His face bent into a rueful smile. ‘You know who I am,’ he shouted. ‘You are the man in flat number twenty-four and I am Charlie the milkman.’

‘Oh yes,’ I said weakly. It was the milkman with the deaf horse. ‘Have a good holiday, Charlie. I’ll settle up when you get back.’

‘Coaches for Costa del Sol,’ the loudspeakers were saying. The Customs and Immigration gave a perfunctory sleepy nod and stamped ‘30 days’ on the passport.

I could see a square, solid, British figure fighting through the Costa del Sols. ‘Welcome to Gibraltar,’ said Joe MacIntosh, our man in Iberia.

7 Short talk (#ulink_c393107d-e0a1-5f62-bd63-3b8b43f97efa)

Joe MacIntosh drove me out to one of the married-officer accommodations along Europa Road past the military hospital. It was 3.45 a.m. The streets were almost empty. Two sailors in white were vomiting their agonizing way to the Wharf and another was sitting on the pavement near Queen’s Hotel.

‘Blood, vomit and alcohol,’ I said to Joe, ‘it should be on the coat of arms.’

‘It’s on just about everything else,’ he said sourly.

After we’d had a drink Joe promised to brief me in the morning before he went on ahead. I slept.

We had breakfast in the mess and the water supply wasn’t quite as salty as I remembered it. Joe filled in some of the details.

‘We have been hearing about this counterfeit paper money for some years; it’s being washed up out of the sea.’

I nodded.

‘I’ve made a little sketch map.’

Joe opened his wallet and pulled out a page of a school exercise book. On it was drawn a shaky tracing of the south-western quarter of the Iberian peninsula. The Straits of Gibraltar were in the bottom right-hand corner. Lisbon was near the top left. Small mapping-pen crosses had been inked in along the coastline. The 100-kilometre stretch between Sagres (on the extreme south-western tip) and Faro curved, in a 100-kilometre-long bay. Trapped into the curve like bubbles were most of Joe’s little marks.

Joe began to tell me the arrangements he had made. ‘The nearest town to the wreck is Albufeira, here …’ Joe hadn’t changed much from the tall, muscular, Intelligence Corps lieutenant who came to Lisbon as my assistant in 1942. ‘… This is a list of all the wrecks that have happened between Sagres and Huelva and …’ Scores of young Intelligence Officers came to Lisbon in ’41 and ’42, all anxious to spend one strenuous week bringing the Axis to its knees. Mostly they fell prey to the simplest little security traps we set or they got into arguments with Germans in cafés. We hooked their new boys and they hooked ours, and old timers (anyone who had spent more than three months there) exchanged sardonic smiles with their enemy opposite number over thimbles of black coffee. ‘… using an Italian civilian frogman with whom I have worked before. He is perhaps the best frogman in Europe today. If you stop overnight in the town I have marked I’ll phone him to meet you there. Code word: conversation. I’ll be going by another route.’

‘Joe,’ I said. Through the window I could just see Mount Hacho on the North African mainland across the clear air and sunny water of the Straits. ‘What have you been told about this operation?’

Joe slowly brought a packet of cigarettes from his pocket, took one and offered them.

‘No thanks,’ I said. He lit his own and then put away his matches. His hands moved very slowly but I knew his mind was working like lightning.

He said, ‘You know the Wren with the rather large …’

‘I know the one,’ I said.

‘She’s the cipher clerk,’ Joe said. ‘I was chatting her up the other day when I noticed a clip-board with carbons of all the messages I’ve sent from here to London over the last two months. They all had BXJ in the corner. I’d never heard of that priority before, so I asked her what it was.’ He dragged on the cigarette. ‘They are sending all our signals traffic to somebody in London for analysis.’ Joe looked at me quizzically.

‘Who?’ I said.

‘She’s only the clerk,’ Joe said, ‘it’s the signals officer that redirects them, but she …’ He tailed off.

‘Go on.’

‘She’s not sure.’

‘So she’s not sure.’

‘But she thinks it goes to somebody c/o the House of Commons.’

I signalled for some more coffee and the Spanish waitress brought us a big jug. ‘Have some coffee,’ I said, ‘and relax; it’ll all work out.’

He gave me a shy Li’l Abner smile. ‘I wanted to tell you,’ he said, ‘but it sounds so unlikely.’ We went down to Andalusian Cars in City Mill Lane to pick up a grey Vauxhall Victor for me and a Simca for Joe. He started out for Albufeira and would be there before evening. I had some things to attend to in Gibraltar and my journey would be in two hops.

It was still the same squalid town that I remembered from wartime. Huge barrack-like bars with everything breakable long since removed or broken. Accordion music and drunken singing, red-necked military policemen bullying fat soldiers, thin-lipped army wives weaving among the avaricious Indian shopkeepers on the sun-bright pavement. The secret of enjoying Gibraltar, a ship’s doctor had once told me, is not to get off the boat.

8 I hit it (#ulink_c595d339-29d3-5fb1-90a2-1a856edf9a0e)

Wednesday morning

The end of Gibraltar’s High Street is Spain. Grey-suited frontier guards nodded, looked for transistor radios and watches, then nodded again. I drove through a couple of hundred yards of dead ground, then through the second control post. The road winds back through Algeciras, and looking across Algeciras Bay one sees the whole of Gib. lying there like a wedge of stale cheese; from the heights where the apes stare down to the airport, to the south where the Ponta de Europa drops away to the sea.

After Algeciras the road began to climb. At first it was dry as burnt toast, but soon white steamy cloud twined through the wheels or sat in heaps on the quiet road. To the left a cliff top was as jagged as a picnic tin. The road descended and followed the beaches northward. It was 3 p.m. The sky was as blue as the Wilton diptych and the warm air drew the smog from my lungs.

Sucking nourishment from the Seville highway, Los Palacios is a huge, gangling village that would be a town if it could afford the paving stones. Great loops of underpowered electric bulbs stared fish-eyed into the twilight as I drove in. One café had a new Seat

1400 outside it. The name EL DESEMBARCO was painted in gaunt letters, deep set into the dark doorway. I put my foot softly on to the brake. A big diesel lorry hooted behind me as I pulled off the roadway. The lorry parked too and the driver and his mate went inside. I locked up and followed.

There were about thirty customers in one huge barn-like room. Smoked hams and bottles were strung across the walls, and large mirrors with gold advertisements hung from the wall and gave curious sloping dimensions to the reflected drinkers. A glittering Espresso machine roared and pounded. On the black matt counter-top bills were chalked and computed by boys with damp white faces who darted between the gigantic barrels, stopping only to wring out their aprons in gestures of despair, and shout plaintive entreaties to the kitchen in high waiters’ Spanish that cut through the clouds of smoke and talk.

I girded up my conversation.

‘Deme un vaso de cerveza,’ and the waiter brought me a bottle of beer, a glass and a small oval plate of freshly boiled shrimps, moist and delicious. I asked him about rooms. He slipped his white apron over his head and hung it on a hook under the Jayne Mansfield calendar. I hate to think what it might have been advertising. The boy led me out through the rear door. To my right I saw the flare of the kitchen and caught the piquant smell of Spanish olive oil. It was almost dark.

There was a sandy courtyard at the back, partly covered with bamboo from which hung rusting neon lights. Down one side of the courtyard a glassed-in stone corridor gave access to small, cell-like rooms. I negotiated a pram and a Lambretta motor scooter and entered my room. It contained an iron bedstead with crisp clean sheets, a table and a cupboard for a chamber-pot.

‘Veinte y cinco – precios fijos si v gusta,’ said the waiter. A fixed price of twenty-five pesetas seemed O.K. to me. I dumped my overnight bag, gave a Gauloise to the waiter, lit both our cigarettes and went back to the noisy restaurant.

The waiters were serving wine, coffee, sherry, and beer as fast as they could go – putting a squirt of soda into a glass from a distance of two feet, slamming down little plates of smoked ham, salt biscuits or shrimps, arguing with the drunks while adroitly serving the sober. The big tent of sound throbbed against the rafters and hammered down again.

All through the fish soup and omelette I waited for my contact. I asked who owned the new car outside. The boss owned it. I had more Tio Pepes and watched the lorry driver who had hooted me doing a card trick. At 10.30 I wandered out front. Three men in overalls sat on the unpaved ground drinking from a flagon of red wine, two children without shoes were throwing stones at the big diesel truck and some men were arguing quietly about the market value of a used motor-cycle tyre.

I unlocked the door of the car and reached under the dashboard for the .38 Smith & Wesson hammerless 6-shot. The grips were powerful magnets. I pulled it away from the car body, folded it into the car documents, locked up and walked back to my room.

My overnight bag still had my used match lying on it, but before going to sleep I opened the little cupboard and put my gun under the chamber-pot.

9 I sit on it (#ulink_e02ea630-6a16-5bc5-a074-41901b07a5d7)

The sun was scorching the courtyard in which I took Thursday’s breakfast. Potted geraniums surrounded the well, and pink convolvulus climbed along the bamboo roofing. Half concealed by the limp washing, a large pockmarked Coca-Cola advert was bleached faint pink by the sun, and the church tower from which nine dull clanks came was toylike in the distance.

‘A friend of Mr MacIntosh, is it not, yes?’

Standing beyond my tin pot of coffee was a squat muscular man, about five feet six. His head was wide, his hair dark and waved. His face was tanned enough to emphasize the whiteness of his smile. He carried his arms in front of his body and continually plucked at his shirt cuffs. He flicked his fingers across a large area of green silk pocket-handkerchief and tapped three fingers of his right hand against his forehead with an audible tap.

‘I have the message for you which your friend request I should deliver in person.’

His manner of speaking had a strange, jerky rhythm and his voice seldom became lower at the end of each sentence, which led one to expect a few more words to appear any moment. ‘Conversion,’ he said. I knew that the real code word was ‘conversation’.

He reached inside his short pin-stripe jacket and produced a hide wallet as lumpy as a razor blade, and from it slid a business card. He replaced the wallet, smoothed his dark shirt, ran fingers slowly down his silver tie. His hands were short-fingered, powerful, and curiously pale. He offered me the card from his carefully manicured hand. I read it.

S. Giorgio Olivettini

Underwater Surveyor

MILAN VENICE

I shook the card a couple of times and he sat down.

‘You had breakfast?’

‘Thank you, I have already consumed breakfast, you permit?’

Señor Olivettini had produced a small packet of cigars. I nodded and shook my head at appropriate intervals and he lit one up and put the rest back into his pocket. ‘Conversation,’ he said suddenly, and gave a vast smile. He seemed to be my passenger to Albufeira.

I went into my room, put the gun into my trouser pocket, picked up my bag and fixed the bill. Señor Olivettini was waiting by the Victor polishing his two-tone shoes with a bright yellow duster.

For about thirty kilometres I drove in silence and Señor Olivettini smoked and contentedly filed and buffed his nails.

My pistol had worked its way under my thigh. It was an uncomfortable thing to sit on. I let the car lose speed.

‘You have planned to stop?’ said Señor Olivettini.

‘Yes, I am sitting on my gun,’ I said. Señor Olivettini smiled politely. ‘I know,’ he said.

10 Sort of boat (#ulink_54cadaf2-deff-5eb0-a939-574a5ea5f21b)

This was Giorgio Olivettini, the man who had thrown Gibraltar into a panic during the war when as an Italian naval frogman he had operated across Algeciras Bay from a secret base in an old ship.

‘We are to take cargo from a U-boat, huh?’ Giorgio asked.

‘Not a U-boat,’ I corrected gently.

‘Oh yes,’ said Giorgio confidently. ‘Your Mr Joe MacIntosh send me Kelvin Hughes echo-charts of the wreck. She is a U-boat.’

‘You’re sure?’ I asked.

‘The MS 29 is a fine echo-recorder system. I work with her before. I tell you, is a big big U-boat. You will see.’

I certainly hoped it would all become clearer to me.

‘Yes,’ I said, ‘I will see.’ Ahead I could see the roofs of Ayamonte, in the Sector de Sevilla entrusted to Brigada MCVIL.

The River Guadiana forms the frontier between Spain and Portugal. Splashed along its Spanish bank is the little white cubist town of Ayamonte.

I let the car roll down a cobbled side street until the slow-moving river lay in front. I turned and drove along the quayside, negotiating the litter of nets, broken packing-cases and rusty oil-drums. Señor Olivettini produced a U.N. passport and we both went into the tired old building that houses the officials. They looked at our passports and stamped them. On the wall was a vignetted photo of a dark-shirted officer. It was signed in a big looping signature and dated a year before the outbreak of the civil war. One man looked inside the car and I was worried about the pistol. That was just the sort of thing that would cause Dawlish to do his nut. The guard said something to Giorgio and hitched his automatic rifle higher on his shoulder. Giorgio spoke rapidly in Spanish and the brittle face of the guard splintered into loud laughter. By the time I reached the car the guard was inhaling on one of Giorgio’s cheroots.

I drove down the sloping jetty on to a splintered boat. The weight of the car strained the ropes on the hand-made bollard and the water sagged under the burden. The boat grumbled across the oily grey water as the little white buildings floated slowly away. Getting the car on to the land of Portugal is a job for at least twelve helpers, all shouting ‘Back, left-hand down, a bit more,’ etc., in fluent Portuguese. I told Giorgio to get out and make sure they had the narrow planks correctly placed under the wheels. I wasn’t keen to learn the Portuguese for ‘too far’. The car wasn’t square on the boat, and as the rear wheels rolled on to them, one of the planks shot away like a bullet. I let the clutch right in and punched the acceleration. The car leapt forward and hurtled up the steep corrugated ramp like ten thimbles across a washboard. I waited for Giorgio. He walked up the ramp smacking imaginary dust from his impeccable trousers. He looked into the window of the car, his hands nervously engaged in twisting his gold rings. He smiled briefly, took his small, new briefcase from under his arm and put it into the car. I hadn’t noticed him remove it.

‘Valuable,’ he said.

Portugal is a semi-tropical land; cared-for, cultivated, and geometrical. This is not Spain, with leather-hatted civil guards brandishing their nicely oiled automatic rifles every few scorched yards. It’s a subtle land, without sign of Salazar on poster or postage stamp.

‘What about equipment?’ I said. ‘If you are going to look at this submarine do you think you can operate in forty metres?’

‘The first, Mr MacIntosh is bringing for me; the second, yes, I can operate in forty metres. I will use compressed air, it is simple. I am a great expert in the underwater working. Sixty metres I could do.’

The westbound Estrada Principal Numero 125 out of Loule continues the descent the road has been making since S. Braz. A small police-truck hooted twice and sped past us. The road south from this junction leads only to the fishing town of Albufeira; we turned left and headed past the canning factory.

Albufeira is a town built on a ramp. The streets slope steeply uphill and the sound of low gears engaging is constantly heard. The houses that lie along the top of the ramp have their white backs inset into the top of eighty-foot cliffs.