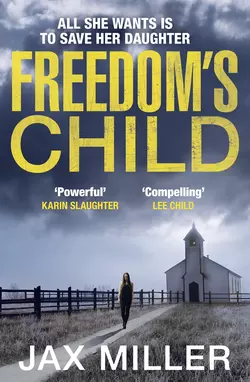

Freedom’s Child

Jax Miller

A heart-stopping debut thriller about a woman named Freedom, who will stop at nothing to save the daughter she only knew for two minutes and seventeen seconds.Call me what you will: a murderer, a cop killer, a fugitive, a drunk…Freedom Oliver has spent the last eighteen years living a quietly desperate life under Witness Protection in a backwater of Oregon after being exonerated of her husband’s murder.But now Freedom’s daughter Rebekah is missing, the same one who was wrenched from her arms just moments after birth. Freedom slips her handlers and embarks on an epic journey across the US to Kentucky, determined to find her child.No longer under the protection of the U.S. Marshalls, Freedom is tracked by her late husband’s psychotic brothers, who will stop at nothing in their quest for vengeance. But they are not the only threat she faces as she draws nearer to the horrifying truth behind Rebekah’s disappearance…

Copyright (#u91bc10fd-43c2-5ba4-9742-17336419c8bd)

Harper

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2015

Copyright © Jax Miller 2015

Jax Miller asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2015

Cover photographs © Jacket layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2015

Cover design © www.headdesign.co.uk (http://www.headdesign.co.uk)

Cover photographs © Anne Heine/Alamy (chapel in landscape); Stephen Mulcahey/Arcangel Images (female figure)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This is a work of fiction. Any references to real people, living or dead, real events, businesses, organizations and localities are intended only to give the fiction a sense of reality and authenticity. All names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and their resemblance, if any, to real-life counterparts is entirely coincidental. The only exception to this are the characters Dean Scott, Syd Fraser, and Tony Wishart – who have given their express permission to be fictionalized in this volume – and Hector, the resident Banff Police Station ghost, who hasn’t. All behaviour, history, and character traits assigned to these individuals have been designed to serve the needs of the narrative and do not necessarily bear any resemblance to the real people. The Tarlair Outdoor Swimming Pool signage appears courtesy of Aberdeenshire Council.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Source ISBN: 9780007595914

Ebook Edition © June 2015 ISBN: 9780008132798

Version 2015-12-02

Praise for Freedom’s Child: (#u91bc10fd-43c2-5ba4-9742-17336419c8bd)

‘A terrific read from a powerful new voice’

Karin Slaughter

‘Original, compelling and seriously recommended’

Lee Child

‘Seldom has a literary creation bounced off the page with as much raw vitality … one of the standout debuts of the year’

Guardian

‘There’s a reckless power to Miller’s untamed prose … she’s just plain amazing’

New York Times

‘A relentless and fiercely compelling debut. Freedom’s Child will hold you captive until the very last page’

Richard Montanari

‘A propulsive, full-throttle tale of revenge and redemption’

Irish Times

‘Freedom’s Child isn’t just a great debut, it’s a great book with one of the most angry, complex and compelling heroines this side of a certain girl with a certain tattoo’

Simon Toyne

‘I loved it. Such an original new voice’

Kate Medina

‘Brilliant’

Julia Crouch

‘Freedom’s Child is a remarkable novel that is as emotionally gripping as it is pulse-pounding. Equally heartbreaking and hard-boiled, Jax Miller has delivered a sensational debut novel’

Ivy Pochoda

‘Freedom’s Child is a page-turning tale of redemption that explores the complicated, intertwined bonds of motherhood and justice’

Elizabeth L. Silver

‘Horror, mistrust, deception and a cracker of a female protagonist. A top-notch, right rollicking read’

Writing.ie

‘A ferocious, witty, tough-as-nails debut’

The Times (South Africa)

‘Abounds with a charged rawness which is quite compelling to witness’

Jaffa Reads Too

‘This is a tense, absorbing read with a restless energy about it that appealed to me completely … I’m sticking with this author for life’

Liz Loves Books

Dedication (#u91bc10fd-43c2-5ba4-9742-17336419c8bd)

For Babchi and the boss of the city.

And to Pat Raia, the Robin to my Gotham.

Table of Contents

Cover (#u3bf91da9-2bc1-5fb5-b41b-aeb338687265)

Title Page (#u2a65a191-5e4c-5ae1-b34f-3e240432e141)

Copyright (#u01833ade-13f4-593d-8d6b-1109cae5c062)

Praise for Freedom’s Child (#u1d44d08e-c31e-539c-98ce-8c4943944007)

Dedication (#u814e7161-6cdd-51e4-96be-933890775210)

Prologue (#ub9a5133c-9c8b-5318-9664-f11e26efa016)

Part I (#uc20ce825-76c1-5e8a-8b02-7b7095f212f8)

Chapter 1: Freedom and the Whippersnappers (#u0b9ff948-42ff-5bfb-bcf8-26a7103b4cb2)

Chapter 2: Mason and Violet (#u157a48af-eb5c-5708-a0f5-42d2c570acda)

Chapter 3: The Cockroach (#ucf8b95e9-21a3-5236-aacf-573463b7994e)

Chapter 4: Home to ma (#ufd97ca1b-21ca-5a12-bb73-c1c309ecbae8)

Chapter 5: The Need to Know (#u6f045af8-3cd7-5625-b6d7-43057c06998c)

Chapter 6: The Music of the Devil (#u6a1ec7d6-9c06-551f-bc5f-50fede97c2e9)

Chapter 7: High School Sweetheart (#u44ad4f94-d429-5685-8311-5ac705e5a656)

Chapter 8: The Suicide Jar (#u1dc9d4dd-05f6-5acc-9a0b-712e1d502375)

Chapter 9: Freedom and Passion (#ue2136444-c111-51e9-8240-61310f57dbed)

Chapter 10: The Delaney House (#ue3de75b9-f3cc-5c4a-99bb-0b180c715eb6)

Chapter 11: Copper (#u849ca1d5-0724-5edc-9134-14b8694fe37c)

Chapter 12: The Firm and the Archangel (#ufeab913d-0078-5154-b09f-584a8574643e)

Chapter 13: On The Breast (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14: Mattley (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15: The Empty Womb (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16: Peter (#litres_trial_promo)

Part II (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17: The Bluegrass (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18: Freedom in Jesus (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19: The Third-Day Adventists (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20: The Nose of a Viper (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21: A Favor (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22: The Land of Freedom (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23: Freedom and Sacrifice (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24: Freedom and the Road Less Traveled (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25: Cat’s Cradle (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26: The End of Autumn (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27: America the Beautiful (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28: Charmed (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29: The Legend of Freedom (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30: Cuckoo (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31: Sunset (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32: Run, Rebekah, Run (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33: Speak Udda Debble (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34: The Whipping Post (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35: Freedom and Discovery (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36: Retired (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37: Freedom and Surrender (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38: Freedom McFly (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 39: The Shadows of the Phoenix (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 40: The Skin of Butterfly Wings (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 41: Sunrise (#litres_trial_promo)

Part III (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 42: Eggshells (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 43: The General Store (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 44: With Prejudice (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 45: Stripped (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 46: All Debts Are Paid (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 47: When Life Gives You Lemons (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 48: The Deacons (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 49: Their Blood, Your Hands (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 50: Cabin Fever (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 51: A Parade of White (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 52: Whistler’s Field (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 53: A Parade of Black (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 54: Sunday (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 55: Painter (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 56: Sovereign Shore (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

(#u91bc10fd-43c2-5ba4-9742-17336419c8bd)

Prologue (#u91bc10fd-43c2-5ba4-9742-17336419c8bd)

My name is Freedom Oliver and I killed my daughter. It’s surreal, honestly, and I’m not sure what feels more like a dream, her death or her existence. I’m guilty of both.

It wasn’t long ago that this field would ripple and rustle with a warm breeze, gold dancing under the blazes of a high noon sun. The Thoroughbreds, a staple of Goshen, would canter along the edges of Whistler’s Field. If you listen close enough, you can almost hear the laughter of farmers’ children still lace through the grain, a harvest full of innocent secrets of the youthful who needed an escape but didn’t have anywhere else to go. Like my Rebekah, my daughter. My God, she must have been beautiful.

But a couple weeks is a long time when you’re on a journey like mine. It could almost constitute something magnificent. Almost.

I catch my breath when I remember. Somewhere in this field, my daughter is scattered in pieces.

Goshen, named after the Land of Goshen from the Book of Genesis, somewhere between Kentucky’s famous bourbon trails in America’s Bible Belt. The gallops of Thoroughbreds that haunt this dead pasture are replaced with the hammering in my rib cage. The mud cracks below me as I cross the frostbitten field, steps ripping the earth with each fleeting memory. The skies are that certain shade of silver you see right before a snowstorm; now, the color of my filthy fucking soul.

I’m reminded of the sheriff behind me with an itchy finger and a Remington aimed between my shoulder blades. I’m reminded of my own white-knuckled grip on my pistol.

Call me what you will: a murderer, a cop killer, a fugitive, a drunk. You think that means anything to me now? In this moment? The frost pangs my lungs in such a way that I think I might vomit. I don’t. Still out of breath, I use the dirty robe to wipe blood from my face. I don’t even know if it’s mine. There’s enough adrenaline surging through my veins that I can’t feel pain if it is.

“This is it, Freedom,” the sheriff calls out in his familiar southern drawl. The tears make warm streaks over my cold skin. The cries numb my face, my lips made of pins and needles. There’s a lump in my throat I can’t breathe past. What have I done? How the hell did I end up here? What did I do so wrong in life that God deemed me so fucking unworthy of anything good? I’m not sure. I’ve always been the one with the questions, never the answers.

PART I (#u91bc10fd-43c2-5ba4-9742-17336419c8bd)

1 (#u91bc10fd-43c2-5ba4-9742-17336419c8bd)

Freedom and the Whippersnappers (#u91bc10fd-43c2-5ba4-9742-17336419c8bd)

Two Weeks Ago

My name is Freedom, and it’s a typical night at the bar. There’s a new girl, a blonde, maybe sixteen. Her eyes are still full of color; she hasn’t been in the business long enough. Give it time. Looks like she can use something to eat, use some meat on her bones. I know she’s new because her teeth are white, a nice smile. In a month or two, her gums will shelve black rubble, and she’ll be nothing but bone shrink-wrapped in skin. That’s what happens in that line of work. The perks of being young are destroyed by the lurid desires of men and the enslavement of drug addiction. Such is life.

A biker has her by her golden locks, heading for the parking lot. The place is too busy, nobody notices. He blends in with the other leather vests and greasy ponytails, the crowd crammed from entrance to exit. But I notice. I see her. And she sees me, eyes glassed over with pleading, a glint of innocence that may very well survive if I do something. But I have to do something now.

“Watch the bar,” I yell to no one in particular. I’m surprised by my own agility as I jump over the bar and into the horde, pushing, elbowing, kicking, yelling. I find them, a trail of perfume behind the young girl. I take the red cap of the Tabasco sauce off with my teeth and spit it out. The biker can’t see me coming up behind him as he tries to leave the bar; he towers over me by a good foot and a half. I cup my palm and make a pool of hot sauce.

* * *

I still own the clothes I was raped in. What can I say? I’m a glutton for punishment. My name is Freedom, though seldom do I feel free. Those were the terms I made with the whippersnappers; if I did what they wanted, I could change my name to Freedom. Freedom McFly, though I never got to keep the McFly part. They said it sounded too Burger King-ish. Too ’80s. Fucking whippersnappers.

Freedom Oliver it is.

I live in Painter, Oregon, a small town showered in grit, rain, and crystal meth, where I tend a rock pub called the Whammy Bar. My regulars are fatties from the West Coast biker gangs like the Hells Angels, the Free Souls, and the Gypsy Jokers, who pinch my husky, tattooed flesh and cop their feels.

“Let me get a piece of that ass.”

“Let me give you a ride on my bike.”

“How ’bout I give you freedom from those pants?”

I hide my disgust behind a smile that convinces the crowd and stick my chest out a little more; it brings in the tips, even if it makes me shudder. They ask where my accent’s from and I tell them Secaucus, New Jersey. Truth be told, it’s from a shady area on Long Island, New York, called Mastic Beach. It’s not like the peckerwoods can tell the difference.

I tear out my umbrella in the early morning after my shift is over and the bar is closed. I squint through the October rains and the smoke of a Pall Mall. I swear to God, it’s rained every day since I was born. To my left, adjacent to the Whammy Bar, is Hotel Painter. The neon letters drone through the rain, where some key letters are knocked out so the sign spells HOT PIE. Appropriate, given that it’s one of those lease-by-the-hour roach motels that offer ramshackle shelter to anyone wanting to rent cheap pussy. The ladies huddle under the marquee of the reception desk to hide from the rain and yell their good-byes my way. I wave back. Goldilocks isn’t there. Good. Looks like the night’s slowed down.

Fuck this umbrella if it doesn’t want to close. I chuck it to the dirt lot and climb into the rusty hooptie of a station wagon. I remove my nose ring and put the smoke out in an overflowing ashtray.

“Jesus Harry Christ,” I scream, alarmed by a knock on the window. I can’t see through the condensation and open it a crack to find a couple suits. “Whippersnapping jack holes.” They look at me like I’m nuts, but I’m pretty sure they expect it. People have a hard time trying to understand what I say most of the time. “Isn’t it late for you guys?”

“Well, you keep making us come out here like this,” says one of them.

“It was an accident.” I shrug as I get out of the car.

“Trying to blind a man with Tabasco sauce was an accident?”

“Semantics, Gumm,” I say as I fiddle with the keys. “Guy got rough with one of the girls, so I slapped him on the cheek. Only I missed his cheek and got his eyes. I only just so happened to have Tabasco sauce spill in my hand not a moment before. Besides, he’s not pressing charges, so I’m sorry you guys had to make the trip from Portland.”

“You’re walking on thin ice,” says Howe.

“Tabasco won’t blind you.” I shake the rain from my hair. “Just hurts like fuck and keeps you awake.”

“Well, he was mad enough to call the cops. If it weren’t for us, you’d be sitting in jail right now,” says Gumm.

“Besides, an eye patch suits him.” I lead them into the closed pub, turn on the power, and grab three Budweisers. They eyeball the beverages. “Relax. I won’t tell,” I offer.

The lights are dim, borderline interrogational, above the island bar in the middle of a large, old wooden floor furnished with the occasional pool table. The scent of stale smoke hangs heavy, etched in the wood’s grooves like a song impressed on a vinyl record. The music turns on to Lynyrd Skynyrd. U.S. Marshals Gumm and Howe each flip a stool down from the bar and sit.

“You know how it goes,” says Agent Gumm, with his salt-and-pepper hair, handlebar mustache, and sagged jowls. He doesn’t want to be here, I can tell. I don’t want him here either. Court-mandated. Fuck the system. Let’s get this over with. We’ll fill out the forms, I’ll get a lecture. Consider this a warning. Yeah, yeah, it’s always considered. To Gumm’s side is Agent Howe, who does a quick read over the files in their manila envelopes. “How’s this job treating you, Freedom?”

“I’d come up with a clever remark, but I’m too tired for the bullshit.” I wipe my leather jacket with a bar towel. “Just slap me on my wrist and we can all be on our way, why don’t you?”

“Was just asking about the job, is all,” says Howe, a handsome man in his early forties with jet-black hair and green eyes. I’d bang him. Well, maybe if he wasn’t such an asshole. Though I doubt that’d stop me anyway.

“Let’s cut the shit. You two didn’t come all the way here from Portland to get on my ass about a tiny bar scuffle.”

They twirl their bottles between their palms. Gumm uses his sleeve to wipe the sweat from his beer off the wood. They look at each other with those raised eyebrows, the kind of look that says, Are you going to tell her or should I?

“Will ya just spit it out?” I roll my eyes and hop onto the bar in front of them. I pull their envelopes from under me and sit Indian-style, their eyes level with my knees.

“Freedom, Matthew was released from prison two days ago. He was granted an appeal and won.” Gumm pretends to cough with the words. Well, isn’t that just dandy? I rest my elbows on my knees, chin on my fists. Which facial expression shall I feign? I go for ignorance, as if I have no idea who this Matthew is that they’re talking about. But I do. It’s why I am a protected witness. In the Witness Protection Program. WPP. Whips. Whippersnappers. But lucky me, I was dismissed with prejudice, meaning I cannot be charged for the same crime twice. Thank God for small favors.

“And?” I don’t want them to know that my heart is pounding and I’m starting to sweat.

Gumm leans in closer. “For a time to be determined, we are heightening your protection. We’ll have one of ours come see you on a weekly basis. Keep a low profile.”

“You mean lower than a biker bar in the middle of nowhere?”

“A small cross to bear for killing a cop, Freedom.” And there are those nasty looks and curled lips from these guys that I know all too well. “C’mon, you’ve got nothing to lose if you admit it already. I mean, you can’t be tried again for it. We know you did it.”

“Good luck proving it. And nice of you assholes to give me a heads-up.” I chug my beer and aim my chin at the door. “Be careful driving back to the big city in that rain. Don’t want you two dying in some terrible accident.” I finish the beer. “That’d just be terrible.”

At least they take the hint. Sometimes they don’t. Sometimes they overstay their welcome. Sometimes they do it on purpose just to piss me off. “By the way.” Howe rises from his stool and closes his coat. “I have to ask. Procedure, you know …” He speaks through his teeth like he has thorns in his ass.

I’ll save him the trouble, if only to get them the hell out of here faster. Their files stick to my wet boots as I bounce from the bar. I grab the soggy pages from under me and hand them over. “Don’t worry, I’m still on my meds,” but this is a blatant lie. And I think they know it’s a lie but don’t care. “No need to ask.”

* * *

I think about Matthew, released from prison after eighteen years; eighteen years of his imprisonment that secured my eighteen years of freedom.

Alone in the shitty apartment, I crawl out of wet clothes and dry my naked body against the cushions of a musty tweed couch. Alone I cry. Alone I look at an old picture of my dead husband, Mark, the one photo that survived an incident with a sink and a book of matches a couple decades ago. Alone I open a bottle of whiskey. Alone I whisper two names in the dark.

“Ethan.”

“Layla.”

Alone. Fucking whippersnappers.

2 (#ulink_e72e47aa-73ce-580b-8ebb-828e1562a31f)

Mason and Violet (#ulink_e72e47aa-73ce-580b-8ebb-828e1562a31f)

I am a boy. This woman’s arms protect me from the vastness of the ocean, blue as far as the eye can see until it forms a gray line dotted with ships. I bury my face in her neck; her laughter moves my small body. But I don’t know who she is. I look up at the sky through her red hair; pockets of sunshine flash spellbindingly through wet locks. Her body, warmer than anything I’ve ever known, a blanket in the coolness of the waves. Her skin smells of coconut and lime. The sounds of seagulls roll in my ears, and I know I love this woman, I just don’t know who the hell she is. “Who are you?” I ask. She never answers in these dreams, just a straight row of blinding white from her mouth. I can’t wake up and I’m not so sure that I want to. She turns so the waves crash into her back, screams of delight in my neck. I wrap my legs tighter around her waist. And during the stillness between the wallops, I trace the tattoos on her shoulders, pick grains of sand from the ends of her hair, and tell her I love her.

“Where is your sister?” she asks.

Mason Paul wakes, shivering in his own sweat, the air still thick even hours after making love, her taste still on his lips. What makes this recurring dream a nightmare, he doesn’t know. He uses his thumb and index finger to gently grab the bones of Violet’s wrist, moving her arm from his stomach. Mason grabs a pack of cigarettes hidden in his sock drawer and sneaks outside, his movement delicate so as not to wake her.

Still too warm for an October night in Louisville, Kentucky, Mason stands naked at the double doors of his balcony, unsure whether his shoulders are an inch higher because of the satisfaction she left with him or with trepidation from the dream. Behind him, Violet snores, sprawled on top of silk sheets the color of her name. He pulls on the Marlboro and watches the stars that glow orange to correlate with the nearing of All Saints’ Day. He pours a bourbon Manhattan with a splash of butterscotch schnapps. It smells like candy corn. It smells like Halloween. These dreams, you’d think I’m some damn mental case. He clears the phlegm of a mild hangover from his throat.

The branches of black willows swing in the large backyard of the Victorian home, a Queen Anne architecture of ivory with black fringes, one that probably housed masters and slaves more than a century ago. He brings his silver necklace to his lips, warming the cross with his breath, but it’s just habit. In recent years, Mason decided it might be less disappointing to consider God as a loosely thrown noun instead of something profound. But it reminds him of his younger sister, Rebekah, the only member of his family who hasn’t shunned him. He misses her greatly. The bourbon doesn’t help.

The home was born of old southern money from Cavendish tobacco fields that line the property’s edges, well-to-do bankers who made lucrative investments when the American economy was at its golden peaks. And now Mason, a promising twenty-four-year-old with a possible future in one day becoming the state’s most successful defense attorney after sticking his foot in the door of one of the most profitable law firms in Kentucky only weeks after acing the bar exam. Impressive at his age, but not entirely unheard of. Currently an associate at the firm, rumors of him being the next senior associate attorney swirled around the offices, which would make him the fastest to reach such a position. The result of a lot of interning, many many hours, and being smart as a whip. He flicks the cigarette down to the grass when he hears Violet turn in her sleep and pretends not to notice her.

A moment later, she wraps her lanky arms around his bare chest from behind. “You’ve been smoking, haven’t you?” Mason hears her smile bleed into the question. I always knew I’d end up with one of my coworkers. Of course, she’d be a corporate lawyer embroiled in the campaign against big tobacco companies.

Cicadas shrill in the distance and bullfrogs croak in the nearby swamps and weeping willows. Mason smirks. “Who, me?” The Manhattan glistens in the moonlight as he places his hand on hers, his gaze still in the backyard.

She squeezes him and breathes onto his back. “I can feel your heart racing with my lips.” She kisses between his shoulder blades.

“Another dream …” He takes a long draw from the martini glass.

“It’ll be OK,” but she worries her attempts at comfort fall on deaf ears.

Mason walks out of her arms and into the bedroom, sitting down on the ottoman with his bottle of Maker’s Mark, his laptop, and papers on the floor around his feet. He goes to his fake Facebook account, Louisa Horn. Thoughts of his sister Rebekah swim through the furrows of his brain. No word in days is odd for her. Hope she finally got the sense to get out of that place. Mason tries to distract himself with the pile of papers that form a cyclone around him. He shuffles through the work, breathing the vapors of bourbon between each page. He feels bad that he can’t make love to his girlfriend because of the distractions of his sister not writing and the rape case finally about to end tomorrow. It’s always that kind of stuff that gets to him. Who could get a hard-on with siblings and court trials on the brain?

“You’re still working on the Becker case?”

“Just double-checking that all my ducks are in a row for tomorrow, is all.” He looks up at her and smiles. “Otherwise, you can forget about Turks and Caicos.”

“Not a chance in hell.” Violet stretches and yawns.

He studies the photos from Saint Mary’s Hospital, the victim’s rape exam. Tender patches colored eggplant branded under her eyes and between her thighs stir something that merits another sip. Behind him, Violet looks down at the same thing.

“How many times do you have to look at those?” she asks.

“Believe me, I don’t like it any more than you do.” He traces the edges of the paper with his fingertips. He sometimes wishes he could become desensitized, lose all sympathy toward the victim like some of his colleagues. “It’s just until I can become senior at the firm, love. Maybe partner, in a few years.”

“Sell your soul to the devil?”

“More like renting it out.” From an envelope, he pulls out a photo and hands it to Violet. He speaks low onto the rim of his glass. It was the only opening in a good firm back then. It was where he was needed. But he wants to get into a different area of practice soon enough, maybe white-collar or real estate, something like that.

She examines the picture. “Where the hell did you get this?”

“An anonymous tip.” He takes the photo from her and examines it. “This is what’s going to win the case. This is what’s going to make me partner at the firm.”

“Paint the victim as a whore …” She trails off.

“I know.” Mason takes a deep breath and rubs his brow.

“It’s perfect.” Violet kisses the top of Mason’s head and walks off. “You’re going to be a fucking star.”

He watches her walk out into the hall, enjoying the way the naked skin of her backside rocks before him, something akin to the artwork painted on the inside of a virtuoso’s dream. As she disappears down the staircase, he washes the image down with another sip. His eyes wander back to the photos, the one Violet approved of: the victim, topless and laughing on his client’s lap the night of the rape in question. The Maker’s Mark gives him confidence, a little more hope than he might have if he were sober: if he can just win this case, he can move into any area of law he wants and never again have to defend another scumbag criminal.

“Where is your sister?” The question of the redheaded stranger from his dream reverberates between his ears.

“That’s a damn good question, lady,” he answers to himself as he goes back to the laptop. “Hopefully as far away from Goshen as someone like her can get.”

It doesn’t sit with him well, Rebekah not contacting him. He knows she’s naive, a bit gullible, traits that can be confused for being slow, but can be chalked up to southern hospitality. Mason clicks to her Facebook page. The inactivity is out of character—she usually posts devotional scripture daily. The last post reads: Galatians 5:19–21.

After years of having it shoved down his throat, Mason still knows the quote without having to look it up. “Now the works of the flesh are manifest, which are these; Adultery, fornication, uncleanness, lasciviousness, idolatry, witchcraft, hatred, variance, emulations, wrath, strife, seditions, heresies, envyings, murders, drunkenness, revellings and such like: of the which I tell you before, as I have also told you in time past, that they which do such things shall not inherit the kingdom of God.”

Below the scripture is a photo of Rebekah and their little sister, Magdalene. But Mason never met Magdalene—his mother was just pregnant with her at the time he was shunned from their church, disowned by the family.

Mason created a fake Facebook account, Louisa Horn, to stay in touch with his sister. He wonders if his parents finally worked out that Rebekah was in contact with him behind their backs. From what he understands, Rebekah was able to keep their father’s suspicions at bay by telling him that Louisa Horn was merely somebody interested in their church. Mason knew of the church’s newly added techniques of preaching in front of department stores and such, trying to lead the lost into salvation, notches in the Bible belts … and the fictional Louisa Horn was just another prospect.

Had Mason known that wanting to become a lawyer, even the mere thought of leaving home, would warrant a sudden severing of contact, he would have been more cautious. But over the years, the wiring in his dad’s brain seemed to shift and loosen from that of a normal-enough evangelistic preacher into something else, something more fanatical. None of the rumors credible, Mason could just laugh them off. But with his father’s transition only developing when Mason was a teenager, and the four-year age gap between him and Rebekah, the fervent dogmas of his father were mostly in hindsight, changes progressing after Mason left home and his family chose to have nothing to do with him.

Mason sits back, rubs his chin, and squinches his brow. He white-knuckles the neck of Maker’s Mark. The red wax coating that covers the glass makes it look like his hands are bleeding. Stigmata, he thinks, remembering an elderly lady in the community who went to his father once for guidance, convinced that she bore the wounds of Christ. But that was a long time ago, back in Goshen. Never a shortage of religious zealots there. Mason rereads the Galatians scripture from his laptop once more. He gets a shiver and thinks to himself, Run, Rebekah, run.

3 (#ulink_62fa3121-d0d7-5d56-88d8-e3dc09d1c32e)

The Cockroach (#ulink_62fa3121-d0d7-5d56-88d8-e3dc09d1c32e)

My name is Freedom and my eyelids are heavy. Through the hangover, I stretch my nakedness across the unkempt bed. My mouth tastes like death, the whiskey seeps grossly from my pores, cheekbones soggy with rye. 11:30 a.m. Not bad. My thighs, sore from hip bones; I know the feeling well. I turn over to Cal on his stomach, his naked ass in the air as he lies stiff in a dead man’s pose.

“You cockroach,” I yap as I kick him right off the bed. He takes the tangled sheets with him. “Who the hell said you could come over and fuck me?”

“You called me in the middle of the night and threw yourself at me,” he yells up from the floor. I have no reason to disbelieve him, it’s not the first time. Cal’s a cowboy, and that’s the best way to describe him. Five years my junior and looking even five years younger, Cal’s the rare sort who can pull off long blond hair and cowboy boots. I, of course, will never admit it out loud, but he has the body of a god and is hung even better than Christ himself.

I throw his white tee at him and slip into a CBGB extra-large T-shirt and stumble into the kitchen. I don’t know whose shirt this is. Could be anybody’s. It’s mine now.

I find a clean dish among a pile of ones I plan to wash someday. I pour dry farina into a chipped bowl and drown it in spiced rum. I sigh. “Was I at least good?” I tend to black out during my romps in the hay. He comes up behind me, turns me around. He picks me up and I wrap my legs around him on the dirty sink.

“As always, Free-free.” He smiles. I’m too hungover for his smile. I push him away.

“Careful, cowboy.” I take a shot from the rum, just to bite the hair of the dog. The cap’s been MIA for days now. There’s a silence that some would regard as awkward, but it isn’t, not to me. In fact, I like quiet. Quiet is good. He gulps orange juice from the carton in front of an open refrigerator. He breathes the tang from his cheeks like a fire-breathing dragon.

“Who is Mason?” He doesn’t care. He reads the ingredients of the juice. He likes the organic shit. Hippie.

“Who?” I observe the filthy kitchen. I just don’t have the energy to clean it. I haven’t had the energy in a long time.

“After you passed out,” he speaks into the pathetically empty fridge. “You were having a nightmare and kept on yelling Mason.” I play dumb, an act I play well. What can I say? I live in a world surrounded by incompetent retards, including Cal. But his skills in the sack compensate for a head full of rocks.

“I never met no Mason.” It’s a double negative, therefore I still tell the truth. A simple manipulation of words to sneak past Cal. “I probably just heard it on TV or something.” The phone rings and I rummage through the kitchen cabinets for it. I put it there when the headaches come. Cal looks at me like most people do: confused. I follow the cord to where the phone sits on a few cans of peas in the back. “Yeah?” I answer. “Yellow? Hello?” I hold the receiver tight against my jaw. I pretend to end the call, covering the hang-up with my hand. “It was the wrong number. Those good-for-nothing salesmen or something.” I’m not telling the truth.

“Your face says otherwise, Free-free.”

I hate when he calls me Free-free. It reminds me of a kid’s pet hamster. The carton of orange juice is back to his lips for seconds. Must be the gin I added to it the other day. And with that stupid grin and those washboard abs, I pretend to watch a commercial ad for Tropicana. I think of their slogan: Tropicana’s got the taste that shows on your face. Sure, if dumb is a flavor.

“I gotta shower.” I untangle the phone cord and walk for the bathroom. “Please be gone by the time I’m out.”

4 (#ulink_792636f4-bb90-58fc-8bb7-a8d7bf8cc664)

Home to Ma (#ulink_792636f4-bb90-58fc-8bb7-a8d7bf8cc664)

Three Days Ago

Matthew Delaney sits on the lidless metal commode in a solitary cell. Ossining, New York, home to Sing Sing prison. He holds a small stack of papers on his bare thighs as he wipes himself.

“Let’s do this, Delaney,” says Jimmy Doyle, the correctional officer. Matthew smiles politely and requests just another minute to finish. The officer looks away. The officers always look away. One by one, he tears each page into tiny pieces and flushes them with his piss and shit.

He kisses one last inch-long square, cut perfect with nail clippers he had snuck in more than a year ago. The scrap reads “Nessa Delaney.”

“Nessa, Nessa, Nessa,” he whispers to the wall of his six-foot-by-eight-foot cell, an old photograph with her eyes scratched out taped above his cot. “I don’t know which I might enjoy more. When I made love to you all those years ago …”

“Time to go, Delaney.” Doyle opens the steel door.

But Matthew takes one more moment to speak to Nessa. “Or when I find you and cut your arms off before drinking the blood?” He feels his guts lift with excitement, the idea of her death akin to the feeling of falling in love. The hatred and yearning for her have blended into one single emotion over the years, one he could neither resist nor fully grasp.

A smirk crawls across his face as he walks down the C-block. Toward the north end is med-sec, medium security, where, as opposed to the solitary confinement that Matthew was so accustomed to, these were shared cells with bars.

Matthew swings his bag filled with his personal belongings over his shoulder as he follows the officer, one he was well acquainted with. The inmates of the north end holler and cheer at his departure, rattling their tin cups against the bars and turning their soap wrappers into confetti, as such celebrations are afforded after a man’s time is served. At the last cell, before entering another passage of security, an inmate sporting ink of the Aryan race throws his shoe at the side of Matthew’s head.

And the smirk becomes teeth grinding.

In a swift movement that resembles something choreographed, Matthew lets his bag fall, reaching into the cell with both arms and pulling the prisoner backward against the bars. He uses his left hand to pull on his right wrist, arm wrapped around his neck and pulling tighter. “Do we have a fucking problem?” He seethes at the man, whose lips start to lose their pigment. He cannot answer, his voice constricted by Matthew’s elbow.

“Cut it out, Delaney.” The guard grabs his biceps. “You’re two steps away from freedom. You gonna throw it away because of this asshole?”

“Freedom …” He releases the man.

“Now, c’mon.” Doyle keys in a code. “Your family’s waiting.”

When they pass security and have a minute alone, Matthew sighs, the blood returning from his face and back to the rest of his body. He shakes the guard’s shoulder. “I can’t thank you enough for all you’ve done while I’ve been stuck in here, Jimmy.”

“I’ve known you since we were kids, Matty.” But Matthew knows the help came only because his mother was the guard’s go-to dealer for good cocaine and the occasional supper. Matthew couldn’t care less, as long as he could get the information his little heart so desired, information pertaining to Nessa Delaney, now known, if his information is correct, as Freedom Oliver. “I’ll come by the house and see you guys soon, gotta visit my mom down there, anyway,” he tells Matthew.

When met by other officers, the guard nudges Matthew in the back. “Let’s move it, Delaney.”

* * *

Mastic Beach, New York: once a hidden gem on the south shores of Long Island, adorned with summer homes and bungalows for Manhattanites getting away for beach holidays during the warmer months. In recent enough memory, it was a safe haven where everybody knew everybody and the streets were lined with crisp, white fencing. Mastic Beach had color and clear skies and everyone loved to listen to the elders speak about the place when the roads were still made of dirt and of pastoral lands before the invention of the automobile. Small businesses were family-owned and -operated, with scents of baked bread that permeated in and through Neighborhood Road. Marinas flooded with beautiful sails that poked from Moriches Bay and rose to the heavens.

But then heroin trickled its way through the sewers of Brooklyn and emptied into the streets of Mastic Beach, and before long, crime rose to astronomical levels. Where people used to smile in passing, now they keep their heads down in fear of being jumped and beaten. Stabbings are as common as visits to the Handy Pantry. The elderly are robbed and the children of Mastic grow up way too fast. Thirteen and pregnant? Congrat-u-fucking-lations. And chances are, if you actually have a grassy patch big enough to be considered a yard, then more than once you’ve seen the lights of a police helicopter looking for a suspect on foot. And in those instances, your brain runs through every troublemaker that you know from your block until you have an idea of who it is they’re looking for.

Today, Mastic Beach is the dumping ground for Section 8 government housing and every perv, creep, and sicko on the Sex Offender Registry list. The town glows red on maps because of them. Every week, the residents get letters in the mail, mandated by Megan’s Law, telling them of rapists and child molesters living only a few houses down. Small businesses have become enclaves of illegal Arabs. And the gangs have colonized the area: the Bloods, the Crips, MS-13. The whites are the minority these days. Except for the Delaneys. They’re their own gang, a whole other species.

* * *

Peter doesn’t have to count how many boxes of wine it takes to get Lynn Delaney drunk. The answer is two, the equivalent of six bottles. But it’s no wonder, when the mother of the Delaney brothers weighed in at six hundred-plus pounds.

Lynn becomes out of breath with every lift and swig of the wineglass. The cabernet stains the crevices of her smile, a smile hard to see past the quarter-ton of lard melting over the king-size bed that has to be supported by cinder blocks instead of the standard brass legs. It’s the first time Peter can remember his mother making an effort to improve her appearance, the purple lipstick stuck to her gray and hollow teeth, a result of too many root canals from years ago when she actually gave a shit about her grin.

“Luke!” she shouts across the house.

“What,” Luke whines from the kitchen.

“Grab me my hair spray off the dresser here.” The yells cause her to be out of breath.

“Get Peter to do it. He’s closer to you.”

“Peter can’t do it. Peter’s retarded.” Peter eyeballs his mother’s grotesqueness from his wheelchair. Lynn continues, “Just get me the fucking hair spray, goddamn it.”

“Fuck sake, Ma.” Luke storms up the hall to her bedroom and tosses the hair spray that was sitting only three feet away from her.

The fat under her arms jiggles as she uses the ol’ Aqua Net, the lighter fluid with a shelf life of ten thousand years, in her nappy gray curls. From the kitchen, John and Luke scream together at the Yankees game, the cracking of Heineken cans from the freezer. Peter smells the fish off his two brothers after they had spent the day down at Cranberry Dock.

It wasn’t uncommon: grown men living with their mothers in these parts. Could be blamed on a shitty economy, but it’s usually overbearing mothers who need house funding and/or lazy men, and there was a shortage of neither in Mastic Beach.

“Ungrateful little bastard,” Lynn says behind Luke’s back.

“Hey, Ma, Matthew’s pulling up!” John screams.

“I’m fucking coming.” She pumps the last of the generic wine from the box and sifts through a pillowcase full of prescription pills until she finds a Xanax to chew on. She plucks the clumps of mascara from her blue eyes, rubs her lavender nightgown straight, and burps as she turns off one of her reality judge shows.

She totters and flounders to climb aboard Mr Mobility, the poor scooter that carries her overflowing body down the hall. Peter follows in his wheelchair. She rolls down, past the crucifixes and photos of the boys when they were actually still boys. At the end of the hall next to the entrance of the living room, a small table that serves as a shrine to her dead son, Mark: a framed photo of him in his NYPD blues, smiling around burned-out tea-light candles. She kisses her hand and touches the picture of his face. She worships the dead. Many in that dirty town do. They pour the first sips of all their drinks to the ground, they get married with speeches of the greatness of lost loved ones, even if they were scum. That’s just the way it is. Praise the dead, turn the scumbags into heroes. Beside Mark’s photo are three red candles, one for each of Lynn’s miscarriages. And though she lost them before their genders could be determined, she knew, she just knew, they were all daughters and named each one, respectively, Catherine, Mary, and Josephine.

An Irish Catholic, Lynn’s made a lucrative living abusing the welfare system and five sons with as many different fathers who took her name instead of Uncle Sam’s. Delaney, a name attached to trouble and whiskey tolerance. It’s a joke around the neighborhood that even the mailman gives the Delaneys’ mail to the cops, since they’re bound to be there sooner or later. As the car pulls in the driveway, Peter watches Lynn inspect her sons lined up by the front door.

First is the youngest brother, Luke, the most charming and promiscuous of the Delaneys. Even when all the girls knew he was responsible for spreading chlamydia to some of the locals, he was still irresistible to them. With blond hair and green eyes that can pierce holes into yours, and rumors of having a porn-star-size cock, he toyed with the idea of becoming a model a few years back. But he never went anywhere with it and opted to hang drywall for a living instead and spread his seed all over Long Island. Six kids that he knows of, at least. Peter curls his upper lip at the overwhelming stench of his cologne attempting unsuccessfully to cover the smell of fluke fish and sweat.

Next is John, a stout man with all the recessive genes: green eyes, red hair, and a temper that can make the streets shake. He has a silver cap for a front tooth and a face full of red hair. He speaks very little, always has, and always seems to dress in heavy clothes, even flannels in the summer. Known as Mastic’s loan shark, John goes nowhere without his baseball bat. If you can pay him back, he’s the best there is. And if you can’t, just change your name and skip town. While everyone knows that he’s not a mute, not one person outside of his family can recall one time they ever heard him speak. Lynn scratches his beard. “Why must you always hide this pretty face?”

Peter is the one in the wheelchair with cerebral palsy, who everyone assumes is mentally retarded, even his own mother sometimes. Peter is Lynn’s excuse to collect a disability check from social services. Unlike his brothers, Peter prefers to stay in his room with pirated movies and books online, staying out of trouble, so to speak. Peter hates his mother. She talks to him like he’s a child, makes him eat the things she knows he can’t stand, and always steals the money he’s entitled to from the government, instead opting to spend it on stuffing her own face while Peter gets the scraps like a junkyard dog. And the term junkyard is fitting, given that the home is kept like a hoarder’s paradise.

His mother smooths out his loose Spider-Man tee, uses her spit to fix his black hair, and pretends not to notice when he jerks away from her. He tells her to fuck off, but no one hears him, or they don’t want to.

In one uniform motion, as if the dam breaks, they all go out to the porch to meet with Matthew. Matthew screams with a smile into his brothers’ arms as he steps out of an old Buick, a clear plastic “personal belongings” bag trailing him. Headlocks and punches in the arms and thighs are the traditional greeting of the Delaneys. And, of course, what kind of reunion would this be without the stares of the nosy neighbors, the same ones who call the police every time the Delaney household gets a little too loud in the middle of the night? Luke is the first to break out the beer.

“Let’s take it in the house,” Lynn shouts from the doorway.

Matthew holds the beer up against the light of an overcast sky. “Christ, eighteen years in the joint, this is certainly overdue.”

“What’s it like not getting laid for eighteen years?” Luke jokes on the way into the house. Lynn smacks him on the arm.

“Almost worth it, after tonight.” Matthew laughs. “Sorry, Ma.”

Inside, Metallica plays in the background as they spend the morning catching up. But the time’s come to talk about the very topic that has brought such a cloud over the family for so long: Nessa Delaney.

Find her.

Find her kids.

Bring them home.

Make the family complete once again.

* * *

The spines of the other Delaney brothers surge with currents of electricity when around Matthew and their mother. With the back doors open, leading to a small backyard, the kitchen smells of wet autumn leaves and marijuana. It’s impossible to tell where the October fog begins and the smoke ends.

“Eighteen years is a lot of time to think. To collect. To dream,” says Matthew, between sips of his Heineken. He tilts his head to the side. “I’d be lying if I said I didn’t want the cunt dead,” his voice always smooth and velvety, like a song at a funeral. As he says the words, he swears he can detect Nessa’s scent. How could he possibly explain his love for her to his family? Who would understand? And despite being caged like an animal for nearly half his life, his eyes always smile, like he’s dying to tell the world all the secrets of the universe. The rest of the guys fidget in their seats around the kitchen table. They nod and pretend to understand, out of fear.

“She murders Mark. Your brother. My son,” Lynn begins, stoned on her Xanax-and-cabernet cocktail. “She takes my grandchildren and hides them away so that we can never see them. The children of Mark.” She absently picks the red nail polish from her fingernails. She feels the blood in her body start to curdle. She feels her feet start to swell, start to retain water from not being back in bed, decides it’s because she needs sugar and proceeds to stuff an orange Hostess cupcake into her cheek. “And then she frames you, my innocent Matthew, and sends you to prison for eighteen mother-fucking years.” Lynn shakes her head with a smile, citrusy crumbs falling in the folds of her neck. She crosses her hands, those fat little sausages with red tips like she’s ripped through someone’s flesh. “Nessa Delaney.” She sticks her tongue out and cringes, resents the fact that they once shared the same last name. “The audacity of the cunt. She must pay.” Lynn begins to sweat with the efforts of chewing and swallowing. “And we must find her children. After all, isn’t that what family’s all about?” Her sons recognize that gleam, the flames behind her eyes starting to ignite with ingenious plotting, often seen right before she shoplifts or rips a guy off from Craigslist or sends her sons to get something she wants but can’t have. “I wish we did this twenty years ago.”

“Yes, Ma, but it’s my revenge too,” Matthew says as he puts his hands on hers. “As much mine as yours.”

“They should make a saint out of me for waiting so fucking long.”

“Yes, Ma. And you waiting for me to get out so this revenge could be mine means more to me than you’ll ever know.” Lynn bats her eyes at his appreciation.

Peter starts to object but stutters over his own words. Matthew shoots him a glare so ferocious and hateful that it paralyzes him in his own wheelchair. With a flat, soulless tone he says, “And we’re all in this together.”

Peter gets his first good look at Matthew. He notices the thin threads of white at the edges of his black hair only make him look more monstrous than before, like a mane beginning to ice over. His blue eyes are still too light to match the rest of his face, those eyes that nearly turn to white when he’s doing something evil. He looks more like Lynn than ever, except he’s lean and hard. Prison hard.

“But how the hell are we supposed to find her and the kids? We know she’s been a protected witness since she killed Mark,” says Luke as he rolls another joint.

“O ye of little faith. In prison, everything is accessible for a price. Information is no exception.” Matthew taps his finger on his temple. “Everything you need to know about Nessa Delaney is in here.” He looks over to Lynn and smiles.

Lynn Delaney has never been prouder of her sons in all her years. At the sight of Matthew, the long wait almost seems worth it. In this way, her Matthew can guide the rest, be Lynn’s eyes and ears on their journey to kill her ex-daughter-in-law. “I only ask that you do things to Nessa that no mother would want to hear about until she begs to die. And I don’t need to tell you to be sure none of it gets back to this family, do I?” She sighs. “And as for your niece and your nephew, just … break the news slowly to them. Show them love. Tell them Grandmother has waited patiently for twenty years and looks forward to hugging them.” She takes a cigarette from Luke and puffs away. Her teeth are burned.

“She goes by Freedom Oliver these days,” says Matthew.

“Freedom?” Lynn scoffs. “Fucking clever.”

“Let’s leave in the morning, then.” Luke smiles at the thought of bloodshed.

“Fuck that.” Lynn kicks the bottom of the refrigerator from the motor scooter. “I’m not waiting any longer.” The steam seems to rise from her, liable to ignite the Aqua Net if she gets too angry. She brushes black cat hair from her sleeves, composes herself with a wheezing from the throat, and puts her cigarette out on the kitchen counter, no ashtray or anything. “My boys, my boys …” From her sleeve, she pulls out two fifty-dollar bags of cocaine and cuts five lines with her driver’s license in front of them, a driver’s license long expired since she hasn’t left the house in more than three years. The boys’ spines become a little more erect. When she’s done, she licks the edge of the card before turning a twenty-dollar bill into a straw. Peter can’t help but wonder how a habitual coke addict could be such a morbid size. “You don’t want to keep your mother waiting, do you?” She inhales a line through her left nostril before handing the twenty-dollar bill to Matthew. Her jaw sways back and forth, her pinkies twitch with the mechanical taste.

Matthew stares straight ahead before he snorts the next line. “No, you never have to wait for us, Mother.” The others nod, agreeing with anything to get a turn at the coke. They watch as her nose starts to bleed, as it usually does, down her face and landing on the remaining orange cupcake, the white drizzle of frosting now spotted with crimson. But Lynn doesn’t mind her warm blood falling down on her dessert, and she stuffs it in her gob anyway. She stares each one of her sons in the eyes. “Let John drive.” Lynn throws a set of keys on the table. “The plates are fake and the E-ZPass is stolen, so tolls for the bridges and turnpikes are free. You guys better head off to avoid rush hour.”

With their hearts racing with drugs, anticipation, and obedience, they leave.

Lynn watches Matthew, Luke, and John take off from the window. This is payback for Mark, you stupid bitch, she says to her reflection. She is a queen, releasing her wolves into the wild, on the hunt. As the car leaves the driveway, she sees the next-door neighbor. An old man from Puerto Rico, he paces in circles in an old and ragged green dress with black polka dots. His daughter’s mentioned before that he was showing signs of dementia. Is anyone normal anymore?

She licks the blood from her lips, hears the creak of Peter’s wheelchair turning toward her. He stammers, as if his vocal cords are trying to disconnect from his body.

“Yu, yu, you’re … a … f-f-fucking ba-ba-bitch,” Peter says.

Lynn uses the back of her hand to wipe the blood across her face, up her cheeks like war paint. She leers and says, “And here I was thinking you my-my-my-might want to eat ta-ta-ta-today …”

5 (#ulink_78628240-1854-5191-b527-50a2d98116ce)

The Need to Know (#ulink_78628240-1854-5191-b527-50a2d98116ce)

Today

My name is Freedom and I hate this woman’s looks. Yeah, it’s an antipsychotic, just give it here so I can go. Walkers Pharmacy, the Botox bitch, I call her. Too much collagen in the lips. Maybe she’s not giving me a dirty look after all. That might just be her face.

Seeing a psychiatrist is not my idea. Whippersnappers make me do it. Every week for the past eighteen years. That’s 936 hours. What good has it done? I grab my prescription and leave.

* * *

My name is Freedom and I’ll be happy the day I never have to hear ZZ Top again. As always, I leave myself about half an hour to hang out in the back before my shift starts. I sit in the office where we keep the safes, computers, security cameras, accounting and inventory records, cluttered manuals, and magazines. It’s where I take advantage of the Internet, being that I don’t actually own a computer and the service on my cell phone sucks like an eager Vietnamese prostitute.

Carrie stands behind me, but she isn’t the nosy type at all, just eyeballs the office.

“What are you doing?” I ask. I already know the answer and say it with her: I’m moving things with my mind. She’s always rearranging something. Carrie’s my boss, but a good boss. A husky lesbian, she’s one of my only friends here in Oregon. She’s rough around the edges but has a huge heart and never makes a pass at me, aside from the occasional “If you were a lesbian, my God!” She’s the gay pride-ish type, too, with tats of rainbows and naked pinup girls all over her thick arms.

I return to the computer screen and open three windows after I log in to Facebook. On one page is Mason Paul, attorney-at-law. On the second is Rebekah Paul. The third is a young girl named Louisa Horn, but I suspect it’s a fake profile: one friend, and the only activity is random posts on Rebekah’s wall. My money is on Mason, since he and his sister aren’t Facebook friends. On Facebook maps, Louisa’s locations match Mason’s. And by the looks of things, Mason has little, if any, connection anymore with his adoptive family, with the church.

I look up Galatians 5:19–21 in another tab. Above it, from yesterday, is a post from Louisa Horn that reads: “My sister in Christ, where have you been? I miss you.” It’s been a couple days since she’s posted anything or there’s been any activity from her account. It’s unlike her. “She hasn’t posted anything in a while,” I say to Carrie. I’m not supposed to talk to anyone of my past life, my life before I was Freedom Oliver. But I do. She knows who I am, who I was, who I’m looking at. I trust her. Nothing I disclose to her goes anywhere else. She even knows the things I can’t disclose to the whippersnappers.

“You know how those young’uns are.” Carrie arranges magazines that don’t need to be arranged in the first place.

“No, something’s wrong.” I don’t look away from the computer.

“You don’t know that, Freedom.” She focuses on me.

“I can feel it.” It’s true, something just isn’t right. “I hate that name, Rebekah.” I tap my nail on the screen. “Her fucking Amish Walton parents.”

“They’re not Amish.”

“No, but they might as well be.” We both smile a little as she leaves for her shift.

I browse through her photos. There’s a certain purity about Rebekah, and I don’t think this just because she’s my biological daughter. And while I’ll throw a heap of sarcasm at how she was brought up, I’m happy with her upbringing. She was raised by a good family, raised in the church. I sift through her photos: long, curly hair of ginger with spots of rust across the bridge of her nose. She has a million-dollar smile that stretches between those cute dimples, the only radiance from very conservative attire: long denim skirts over old white Keds, frilly long-sleeved button-downs.

As for Mason, it’s clear he’d found his own way, beyond the graces of God. Girls, bars, smoking, a form of rebellion that wouldn’t do too much harm, typical youth crap. With a full head of brown hair, Mason is incredibly handsome, as seen in the photos tagged to his page through Violet. Trips to Gatlinburg’s Smoky Mountains, tequila sunrises, washboard abs. Christ Almighty, he’s the spitting image of his father, that piece of shit.

Mason and Rebekah were raised by an esteemed reverend in Goshen, Kentucky, Virgil Paul and his ever-so-obedient wife, Carol. I’ve seen him preach via the Internet: a very charismatic man with a smile that makes it look like he’s in excruciating pain. He always sweats and huffs his way through his sermons in his deep southern drawl. He’s average-sized, with black hair and a square head. Tan compared to the pale children and wife he stands with after the service, to bid farewell to the born-agains and thankfuls and the newly restored. But goddamn it, it beats the hell out of the life they’d have had with me, had I tried to get them back. Then again, I don’t think I’d be in this state if I hadn’t had them in the first place.

Rebekah usually posts every evening, 7:00 p.m. on the dot. Always scripture. Always links to her family’s church’s website. And lucky me, I’m one of the most faithful online followers of the Third-Day Adventists’ webcast. My username is FreedomInJesus, and every Sunday, without fail, I follow the sermons. On several occasions, and I attribute this to being one of the oldest online members, I’ve gotten to speak through Skype with Virgil and Carol Paul, a real fucking honor to meet you nutjobs; I’m your biggest fan. I spill my heart over forgiveness and obedience and mercy and this, that, and the other. Spreading the gospel in Or-ree-gan, praise Jesus. Anything for a possible glimpse of Mason and Rebekah.

A few weeks ago I wrote letters to both of them. In fact, I have a massive pile of letters to them I keep at the house, but I never before had the heart to send them. I’ll send them one day, when the time is right, I suppose. They just seemed so happy, so blissfully unaware, I didn’t want to be the tornado to rip through their precious existence. The first time I wrote to them, I brought the letters to work and kept forgetting to take them home. When I did, I must have accidentally mixed them up with my bills. Of course.

As soon as the mailman collected them, I realized my mistake. I even chased after him, nearly mowing him down with my car to get those letters back. I ripped the mailbag from him and spilled it all over the street out of mere frustration. I knew my apartment complex was early enough in his route that there’d be a good chance I’d find them. When the mailman yelled and tried to stop me, I barked at him. Literally, I barked and growled like a dog with rabies. When he started to call the cops, I dared him. “Go ahead, call the fucking cops, see if I care!” But when the witnesses started looking out their windows, I left with a fleeting “Fuck you, man” and went on my way.

Working at the Whammy Bar, large brawls between bikers tweeking on meth aren’t all that uncommon. In those instances, I stand on the bar and pull firecrackers from my boots and throw them at the biggest guys I see.

I found the mailman again nine blocks later.

I could make him out in long socks and shorts up Lindsey Street with his bag of mail. I snuck into the back of his truck through the front and rummaged in an infinite amount of letters, but nothing was organized, none of it made sense. I looked up every few minutes to check if the nerd was coming back. And he was. But I hadn’t found the letters. And there was no way he wouldn’t see me, as the only way out was climbing over the driver’s seat, which was on the passenger side. Time to do it. Just run faster than him. Shouldn’t be too hard. Just move.

I pulled the firecrackers from my boots, where I always kept them, and lit the fuses. I usually cut them, so they explode within seconds, but I left the fuses long, to buy us time. I lit three strings, twenty firecrackers on each, and threw them in the back of the truck as I booked it. I nearly busted my ass as my foot got caught in his seat belt. He saw me. He ran. I can’t remember how many backyards I ran through.

When I reached my street, I breathed a little easier with a cigarette as I caught my breath. I squatted down and leaned against a tree on the side of the road, when lo and behold, guess who sped around the corner … and by speeding, I mean about thirty-five miles per hour, but fast enough that the mail truck’s engine sounded exhausted from the reckless speed. But I didn’t move. I smiled as he throttled in my direction. I waved. You stubborn asshole.

The truck swerved all over the street with the loud pops of firecrackers going off in the back. And for a second I imagined a scene from some kind of old Prohibition-era film. Smoke poured from the front and back, a gray that matched the layers of fog that hovered over Painter.

The only problem with this was that I probably just broke a million federal laws.

Took a lot of paperwork on the whippersnappers’ part and a thousand angry lectures from them to get out of it. It was nothing a little fake crying and a push-up bra couldn’t fix, but I got the warning.

Later that afternoon, after they’d removed the smoldering remains of the mail truck, I walked by with a bottle of Johnnie Walker to head to Sovereign Shore, my favorite place to hide. On the way, I found a stray envelope on the street. I grabbed Mason’s letter from a puddle and tucked it in my bra.

I never got Rebekah’s letter back. But I’d signed the letters Nessa Delaney instead of Freedom Oliver and addressed them to the Paul household so that if they never made it to Rebekah and Mason, the parents couldn’t suspect their faithful servant FreedomInJesus.

At the Whammy Bar, I crack my neck and think about how I should have done more to keep my children, how I didn’t try hard enough. But it’s better this way, at least for them. That’s what I keep telling myself. But the grief still makes me sick to my stomach, even twenty years later. All the milestones I missed out on. At least someone else got those opportunities, to watch two great kids grow up before their eyes. I guess.

6 (#ulink_e9db4763-65c8-5906-8079-da2c3941fa3c)

The Music of the Devil (#ulink_e9db4763-65c8-5906-8079-da2c3941fa3c)

Two Nights Ago

Darkness fills the restroom of the truckstop outside Goshen, Kentucky, where Rebekah Paul cries into a dirty mirror with each chunk of hair that falls into the sink. Her own heavy-handed snips of the scissors send whimpers echoing through the greasy, dim stalls behind her. “God, be with me,” she repeats over and over again, the muffled roars of the truck engines outside rolling in her ears. The sounds of hair slicing are loud near her cheeks; her heart races like it will break through her sternum.

The yellowed lamps over her head buzz with the dying insects they devour at two in the morning. She doesn’t recognize her own reflection, her hair bleached and chopped to the scalp. In the shadows of the restroom, the spots of blood on her collar seem black, similar to the spots on her diary back at home when the pens would leak ink. She looks down, uncomfortable in jeans and a white, tight-fitted Jack Daniel’s tee. She kisses the cross around her neck for the last time with a split lip and tucks it under her shirt so no one can see it. She grabs her backpack. “Lord, forgive me.”

The cool air feels good on her eyes as she walks out to the parking lot; the smells of autumn leaves and oil surround her. At the corner of the lot, Rebekah makes her way toward the Bluegrass bar, an old and grungy pub, as a few big rigs thunder past. She doesn’t recognize the music, something bluesy with guitars, tunes she was forbidden to listen to, the music of the devil.

She has to use both arms to pull open the wooden doors to the pub and is met by a wall of stale cigarette smoke and dirty sinners. Bearded men in suspenders with frothy mugs all turn to stare at the skinny girl, her head down, feeling the cross on her chest through her shirt. She looks around, finds an empty table in the back corner, and goes straight to it, her head aimed at her shoelaces the entire way. She can hear the whispers already, undertones of unspeakable acts they want to do to her, words that shame the Lord and secure them seats in hell right next to Satan himself. She uses her short sleeve to dab the tears from her face, the cotton painful on her skin.

“I know that hurts worse than what it looks,” says an unfamiliar voice. Rebekah looks up to see a thin and ragged man with a nicotine-stained beard and mustache and long, oily hair tucked behind a New Orleans Saints cap, black with a gold fleur-de-lis. “Here, sweetie pie, this oughtta help.” He places a tall glass of beer in front of her.

Rebekah sniffs it. “I’m not allowed to drink,” she says to the glass. “Drinking is against God.” She doesn’t even realize that it’s illegal to drink before twenty-one years of age; the subject was just never brought up at home.

“Naw, sweetie pie, you ain’t gotta worry ’bout that.” He sits close to her in the booth so that she has to move over. “Fact is, God sent me here to look out for ya. A prophecy, ya know?” It isn’t uncommon to hear such talk around Goshen.

She smells the alcohol on his breath and shifts in discomfort but listens anyway. “You’re a prophet?”

“Yes, ma’am,” he says with an incomplete smile. “Our Savior told me that you’d be here, ’n that I needed to com’n getcha outta here and help ya turn from yer evil ways and turn back to the righteous path of God. That’s what He said.”

“He did?”

“Yes’m.” He looks back over his shoulder. “Why are you running away from home? God told me you was running away.” She looks at him in astonishment—perhaps he really was sent by God. But then she looks down and doesn’t answer. “Where are ya tryna go, sweetie pie?”

“The West Coast.”

“Why, hell, that’s where I’m goin’ too.” He keeps tonguing the sockets of missing teeth in his grin. “I can give ya a ride if you want.”

Rebekah gets a bad feeling and looks around the bar. The man leans in close, pressing the front of his body against her side, and breathes heavy enough to make her ear wet. He rubs her knee. “Come with me, sweetie pie.”

She turns her head but can’t get away as he starts kissing her neck, the fog of liquor about to make her sick. God, if you want to send someone, send someone else. Please, God, she thinks to herself. “You’re too close, mister.” She tries to push him away, but she’s too weak against his weight.

“Hey,” a second man yells behind him. She breathes easier when he’s pulled away from her. “You best just leave her alone.” Rebekah sees a young man in a soiled apron that’s supposed to be white, in a stance that says he’s ready to fight. “Now, I ain’t messin’, Joe, you just get on out of here, ya hear?”

“It ain’t like that, me ’n the girl was just talkin’, is all.” He puts his hands up.

“I’ve seen enough of what you call talkin’.” The cook takes the man’s hat and throws it hard into his chest. “Now I suggest you be on your way, I ain’t playing around.”

“Fine, fine. I’m leaving,” he says as he grabs his cap and drags his feet. Rebekah watches a few men from the bar start to gather around the cook. “But you ain’t seen the last of me, kid.” Eyeballed by almost a dozen other truckers who show signs of backing the cook up, the man leaves. When he’s out the door, the men go back to their spirits. Rebekah finds herself crying again, alone with the tall glass of beer he left behind. She doesn’t know what comes over her, but she puts the foam to her lips to taste it. The bitterness of it makes her cheeks water. Forgive me, Lord. She throws her head back and chugs the first beer of her life, breathing only out of her mouth in between swallows so as not to taste it. It runs down the side of her face and neck before she slams the glass on the table. She uses her sleeve once more to pat away the ale, with heavy gasps to catch her breath. She stands up and the room spins under her feet. She looks around for the man in the apron, but he isn’t there. She can’t explain what possesses her, the need to chase after this stranger. Perhaps this is who God sent.

“Have you seen that cook with the dirty apron?” Rebekah asks a bartender.

“Your hero just went to the back for a smoke,” she answers with a smirk as she dries mugs.

Using too much strength, Rebekah nearly falls through the screen door of the kitchen that leads to the back alley. Outside, the cook sits on top of a few red milk crates near full trash bags, smoking. The vents of the kitchen hum above them. “Thank you,” she blurts out. Suddenly, she feels awkward, with intervals of clearheadedness between the bouts of dizziness.

“It was nothing.” He smiles at her. She feels a flutter to her stomach, unsure if it’s the beer or the fact that she’s never before talked to such a handsome guy in all her life. He takes a crate and places it in front of him, waving her over to sit. “Where are you heading, anyway?”

She crosses her arms, too bashful to look into his eyes. “West Coast. Or as far as I can get.”

“Away from whoever did this to you?” He points to her face.

She clears her throat and looks down. “I had it coming.”

“No woman has it coming.” He winces with anger. “You don’t deserve that.”

“No, I did.” Rebekah looks to him for a moment. “Because I sinned.”

“Everyone sins.” His cigarette goes out and he relights it. “Doesn’t make it right, though.”

“I’m Rebekah.” She holds her arms tight, unsuccessfully trying to hide her body in the snug clothes.

“Gabriel.” He holds his hand out to her.

She stares at it with hesitation for a moment. “Like the archangel.” She puts her hand in his.

“Sure.” He sucks hard on his cigarette. “Like the archangel.”

Rebekah watches him shake his hair from the hairnet, a full head of black and soft locks over jade eyes. He unties his apron to reveal a white undershirt and sleeves of tattoos. “So you’re a cook?”

“Part-time. I help my ol’ man do drywall on the weekends. Helps me pay for tuition at U of L and my rent.”

“My brother went to the University of Louisville!” she squeals. “Did you know Mason Paul? He’s a big-time lawyer now.”

“Never met a Mason Paul, but it’s an awfully big school. Name sounds familiar, though. Oh, wait, sure, I know who he is. He’s the one defending the Becker case all over the TV. That Becker, sure gonna be one hell of a linebacker, I’d say. I knew the name Mason Paul sounded familiar.”

“What is school like?”

“You’ve never been to school?” She shakes her head. Suddenly, Gabriel realizes what kind of girl she is. Must be a Mormon or something like it, the sheltered kind. And now she’s running away, rebelling, naive. Those types come a dime a dozen back at the university. “You’re not missing much.” Her purity attracts him and he doesn’t want to stop staring at her. He can see that her frail bones and soft skin have never been touched in a way that they should have by her age. It’s like looking at the sands of a shore that’s never been discovered by the ocean. But he fears she will drown out there, out in the real world, away from her shielded existence. “You shouldn’t be trying to hitch rides cross-country with truckers. It’s dangerous for girls like you.”

“It’s my only way out.” She rubs the toes of her shoes on the dirt. “Do you believe in God?”

“I believe in something …” He looks away, not wanting to appear strange when he sees her shy away from his gaze. “When was the last time you ate something?”

“Yesterday, I think.” He puts his finger up and walks back to the kitchen. He returns with a burger and fries in a foam container.

“I can’t afford it.”

“Don’t worry about money.” He watches her inspect the food as if she’s never seen anything quite like it. “You need to eat.” She uses both hands at once to shovel the food into her mouth. “Why don’t you let me take you out one day? Like a proper date, before you head off to the West Coast, I mean.”

She looks at him wide-eyed. “I’m not allowed to date boys.”

“How old are you?”

“Twenty.”

“You’re old enough to make up your own mind and stop doing what your parents ask of you.”

“I do what God asks of me.” She continues to shove the food in her face. Gabriel takes his apron and goes to use it on her arm, where some ketchup spilled. But she pulls away, fearful, like an injured bird, broken in the sun and being circled by vultures.

Gabriel stares at her with wonder, and though she’s spoken only a few words, he’s fascinated by the mystery that surrounds her. He wants to know her more, he has to know her more. He could see her vulnerability from a mile away and feels the need to wrap her innocence in a blanket and keep it away from the cruelty of a world that wants to take it from her. “I’ll take you to the West Coast.” And as he says the words, he surprises himself. But she’s a reason, the excuse he’s been looking for to drop everything around him and see the world. “I know you don’t know me, but you can trust me.” For some reason, he expected more of a joyous reaction.

“Thank you,” she says, with her eyes down and half a cheeseburger in her cheek.

“Let me take you home. We can leave in the morning.” Really, his intentions are good. “You can have my bed and I’ll sleep on the couch. OK?”

“All right.” She believes this is her prayer come true, that God sent Gabriel to save her from the man who rubbed against her and wanted to take her away. She shows a glimpse of a smile as he takes his apron and throws it in the Dumpster behind him.

“Let’s go.” He leads her through the alley and toward the truck-yard. “I’m parked right over there.” He seems to almost skip in his pace. He stretches his arms over his head and looks up to the night. “Share this moment with me.”

“What?”

Gabriel paces around her and tastes what may very well be freedom for the first time in his life. “Make a memory.”

Rebekah scurries to catch up to him, her french fries shaking in the container. “What are you talking about?” The smile aches her cheeks.

He stops her in her tracks and looks into her eyes. “Aside from family, have you ever held a man’s hand?”

“No,” she says and laughs.