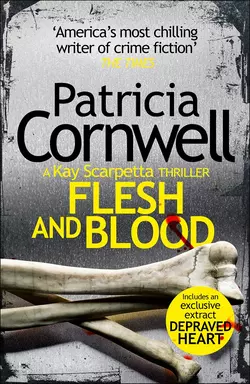

Flesh and Blood

Patricia Cornwell

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 474.54 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: It’s Chief Medical Examiner Dr Kay Scarpetta’s birthday, and while she’s enjoying a leisurely morning, a man is shot dead five minutes from her house. The bullet tore through him as he unloaded groceries from his car. Yet nobody heard or saw a thing.It looks like the work of a serial sniper – one who leaves no trace except for tiny copper fragments, and whose seemingly impossible shots cause instant death. As Scarpetta investigates, uncovering details that only she can analyze, she begins to suspect that the killer is sending her a message.Adding to Scarpetta’s growing unease is the sense that those closest to her are keeping secrets. And when her pursuit of the sniper takes Scarpetta to a shipwreck off the Florida coast, she comes face to face with shocking evidence that implicates her niece Lucy – Scarpetta’s very own flesh and blood…