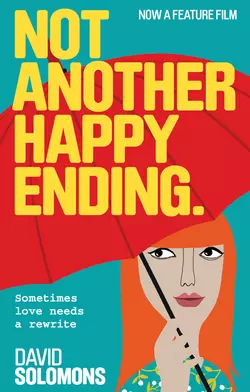

Not Another Happy Ending

David Solomons

Sometimes love needs a rewriteThe stunning romantic comedy from David Solomans, Winner of the 2016 Waterstones Children’s Book PrizeWith her debut novel, Happy Ending, JANE LOCKHART pulled off that rare double – critical acclaim and mainstream success.But now, with just the last chapter of the follow-up book to write, she encounters crippling writer’s block. She has no idea how her story ends…This is not good news for her publisher, TOM DUVAL. His company is up against the wall financially and the only thing that will save him is a massive hit, in the form of Jane’s next novel.When he discovers that his most important author is blocked, Tom realises that he has to unblock her or he’s finished. Everyone knows that you have to be unhappy to be really creative, so Tom decides that the only way he’s going to get her to complete the novel is to make her life a misery…Set within the Scottish publishing industry, and filmed against a stunning backdrop of both romantic and hip Glasgow locations, Not Another Happy Ending is perfect for fans of One Day. “Engagingly watchable” – Mark Adams, Screen Daily “…has more heart than most Hollywood rom-coms…an entertaining diversion and an example of mainstream Scottish cinema that easily holds its own” – Rob Dickie, Sight On SoundAbout the authorDavid Solomons is the BAFTA-shortlisted screen screenwriter of The Great Ghost Rescue, The Fabulous Bagel Boys and Five Children and It. He lives in Dorset with his wife, Natasha Solomons, and their young son. Not Another Happy Ending is his first novel.

DAVID SOLOMONS was born in Glasgow and now lives in Dorset with his wife, Natasha, and son, Luke. He also writes screenplays.

Not Another

Happy Ending

David Solomons

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

For Natasha and Luke, with love.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#ubcb252ad-69d3-543f-a7c3-e24152d1e3b1)

They say that a writer ploughs a lonely furrow. So, with that in mind, I'd like to thank my enormous support team.

My editor Donna Condon and the team at Harlequin. From the first drop of Sancerre it was meant to be.

Copy editor Robin Seavill for straightening out my Brontës and my Beethoven.

Lit agent Stan who has unwittingly unleashed another member of the Solomons family on to the reading public. A mere pawn in our plans for global domination. Bwahahaha.

Film agents Elinor Burns and Anthony Mestriner for their friendship and advice and for sticking by this one (and all the rest) through thick, thin and meh.

Producers Claire Mundell and Wendy Griffin, and director John McKay. This might be the first novel to have been produced and directed before it was written.

Karen Gillan and Stanley Weber for saving me from the inevitable question about who I'd like to play Jane and Tom in a film of the book.

My son, Luke. For not only giving me the opportunity to name him after a Star Wars character but also reminding me that everything's OK even when it feels like it isn't. Luke, I am your father. Never gets old.

And my wife, Natasha, a brilliant writer, all round Renaissance woman (though her specialty is the eighteenth century) and the love of my life.

Table of Contents

Cover (#u0b349615-e785-5580-81aa-768e061f2d35)

About the Author (#uebe58ae2-b1a6-595c-8df2-6ab4e9aa3df8)

Title Page (#ua0ea9f6c-7011-579c-9a90-d9288af5752c)

Dedication (#u73f15658-5e00-5019-93df-19e2fb41ed11)

Acknowledgements

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Epilogue

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 1 (#ubcb252ad-69d3-543f-a7c3-e24152d1e3b1)

‘Here Comes the Rain Again’, Eurythmics, 1984, RCA

Dear Jane,

Thank you for submitting your novel, The Endless Anguish of My Father.

Ten years ago it would probably have received a warm reception, but there is quite enough misery to be found on the non-fiction shelves just now, so, in fiction, we're currently very much into happy stories with happy endings.

At the moment we are enjoying wonderful success with a novel entitled Come to Me, an exotic and erotic tale of revenge and redemption, with a fabulously feisty female lead and a Hollywood ending. If you were willing to make some adjustments to the novel's dénouement you might also be happy to entertain some other minor reshapings: set it in LA or Bangkok rather than Glasgow, say; make your main protagonist a jet-set-y interior designer, for instance, rather than a shelf-stacker; and tweak the key relationship so that, rather than one between father and daughter, it's between our cosmopolitan interior designer—who is actually, despite her success and fabulous wardrobe, just a little girl at heart—and a father figure, who happens to be a domineering (but gorgeous!) film producer. If you were to reposition the novel in that kind of way, then I'd be very happy to reread.

You can certainly write, but these days it's so difficult to launch a new writer—however talented—who's writing about the wrong things.

I have recycled your manuscript.

Yours sincerely,

Cressida Galsworthy

Assistant Editor

Well, thought Jane, at least Cressida gets points for sustainability.

She made space on the notice-board—in a moment of dejection she'd referred to it as her Board of Pain, and the name had stuck—and pinned up this latest rejection, then sat back to admire the varied collection of publishers’ and agents’ rebuffs.

Until she began submitting her novel she hadn't appreciated that there were so many polite ways to say no. Forty-seven examples, to date. The rejection didn't hurt so much; the opinion of some woman in W1 she'd never met was of no consequence to Jane. She had survived far worse in her twenty-five years than anything Cressida—or Olivia or Sophie (so many Sophies)—could throw at her. But early on in the process she realised that the letters could be useful. There were writers who stuck inspirational messages over their desks to spur them on: you can do it … believe in yourself … open that window of opportunity! But encouraging slogans didn't work for Jane; she shrank from their brimming optimism. She was far more likely to want to jump head first out of that window of opportunity. Instead, she bought the board at her favourite vintage store off Great Western Road, nailed it to the wall by the large bay window of her airy, white flat and artfully arranged the naysaying letters. She could hear their honking dismissals as she penned each new query letter and packaged up the latest hopeful submission. I didn't love it. I didn't love it enough. I hated it. Their lack of enthusiasm was grist to her dark Satanic mill.

The printer spewed out another copy of the manuscript, and as she waited for the four hundred pages of her thus far ill-starred debut to stack up she hoisted the sash window, leaned on the sill and took a deep breath.

The air smelled of trees after the rain. Half a dozen slender poplars lined the quiet West End street, in full leaf now that what passed for the Scottish summer had arrived. Beyond them stood a blond sandstone terrace, a mirror to the building Jane's flat occupied. From the top floor someone practised the cello. The doleful strings drifted over the treetops, and suddenly the flats were miserable dolls’ houses with naked windows through which Jane glimpsed desperate lives: a raging argument between husband and wife, the tired old lady with no visitors, the self-harming teenage girl crying in her bedroom. On the street below a wan-faced young mother slouched behind a squeaking pushchair, cigarette jammed between chapped lips, flicking ash over a wailing infant.

The cellist took a break from his practice and reality was instantly restored. The windows revealed no more heartache than a tired executive mourning a slice of burnt toast, and in a patch of sunlight beneath the trimmed poplars it was a smart young mother wheeling a silver-framed pram, talking to her child in a voice as groomed as her suit.

Jane roused herself from her melancholy flight of fancy. This was the West End of Glasgow, a dear green place of well-kempt gardens, specialist delicatessens, and more convertibles per square mile than anywhere else in Europe.

She still couldn't quite believe she lived here. She had grown up in the East End of the city. It was four and a half miles away, but may as well have been a million, her life until the age of sixteen spent in one of the brutalist tower blocks more readily associated with the mean city of legend.

Residents never referred to them as tower blocks; they were always the ‘high flats’. Plain language hid a litany of flaws as deep as their rotten foundations: walls thin as cigarette paper, alien mould choking every corner, a stagnant pool of water in the basement referred to with typical humour as ‘the spa’, and stairwells daubed with crude graffiti that always bothered Jane less for its vulgarity than for its incorrect use of the apostrophe (in retrospect, a clear sign of bookish leanings to come). She laughed when she heard people reminisce about growing up on the schemes: ‘Aye, we might have been poor, but we were happy.’ What a load of crap. It was a miserable place to exist.

She'd only got out thanks to her mum. She remembered the letter arriving on her twenty-first birthday. It was from her mum, which came as something of a surprise since she'd died fourteen years earlier. They'd had so little time together that now when Jane tried to picture her face it was like reaching through water. Turned out mum had squirrelled away most of the wages she made at the Co-op in some kind of get rich quick scheme invested in Jane's name soon after she was born. The letter duly arrived with a valuation and a note on how to claim her inheritance—god, it sounded like something out of Dickens.

She remembered sitting on the floor by the front door reading the contents with growing disbelief. The money was enough for a healthy deposit on her new flat; her new life. It was surprising enough that the dodgy investment had reaped a profit, but the bigger surprise was that her mum had contrived to keep the money out of her dad's thieving hands.

A breeze at the open window ruffled the rejection letters on the board. Set amongst them was a faded Polaroid of an older man, face scored with deep lines, eyes surprisingly soft, one pile driver arm wrapped around a ten year-old girl. In the photograph the late afternoon sun has caught her hair, turning the hated ‘ginger’ a deep, sunset red. Father and daughter are both smiling. But then, that was the summer before it happened.

Mum had taken the snap on a day out to the beach at Prestwick. Unusually, the sun had shone all day, just like it should in a memory. She remembered on the way home afterwards stopping in Kilmarnock at Varani's for ice cream. Best in the world, her dad used to say. Not that to her knowledge her father had ever been outside Scotland. Of course she couldn't be sure of his travel itinerary since then, not after he walked out on them later that year. He left a few months after the photograph was taken, on her birthday. She laughed. How much more of a cliché could you get? Her hand brushed the faded photograph. That was the last time she'd had ice cream from Varani's.

Her eye fell on a flourishing umbrella plant on her desk, its soft, green leaves trailing across the top of her laptop screen. It had been a present from him a few years ago; the only evidence in a decade that he was still alive. When it arrived she prepared herself for the inevitable follow-up: the drunken, apologetic phone call in the middle of the night; the knock at the door with a bunch of petrol station flowers. Neither of them came; only more silence.

The leaves were dry to her touch. She gave the plant a quick spray from a water bottle she kept close by. They didn't have a garden in the high flats, but her dad had installed a window box and she remembered planting it with him. It was a shady spot, he explained, so they filled it with Busy Lizzies in summer and hardy cyclamen in winter. The water-spray hissed. Thinking about it, she wasn't even sure why she kept his plant.

With a whine the printer finished its work. She packaged up the latest submission into a large buff envelope and wrote out the address of the next publisher on her hit list. Tristesse Books were based in Glasgow. Tristesse was French for something she couldn't quite remember. She'd taken Higher French at school, but only just passed the exam. Je m'appelle Jane. J'habite à Glasgow. That was about the extent of her conversation. That and, at a push, she reckoned she could order a saucisson.

Outside, the sky darkened, dampening the earlier promise of sunshine. The wind swirled around the trees, sending a flurry of rain against the open window. Hurriedly, she slid it shut and stood for a moment gazing at her reflection in the rain-soaked pane. Her hair was still long and straight and red, its neat fringe framing a pair of bright green eyes held open in what seemed to be a state of permanent surprise at the vagaries of the big, bad world. When the kids at school had taunted her for being a ‘ginger’, her dad had pulled her onto his knee and together they'd watched his (pirated) copy of Disney's The Little Mermaid. The first few times she didn't understand the message that however tough the journey, even redheads are allowed a happy ever after. Instead, through a terrible misreading, Ariel and her singing friends gave her a horror of losing her voice, and for years the slightest hint of hoarseness convinced her that the end of her little life was imminent.

The superstitions and playground taunts of childhood were long gone, but now she attracted a different kind of unwelcome attention, from the Armani-skinned lizards with large cufflinks who frequented the bars on Byres Road. And these days there was no dad to tell her it would all turn out happily in the end.

He was the one who'd inadvertently introduced her to the world of books, dropping her off in the public library to wait while he took care of a little business at the bookies across the street and then nipping in for a swift pint—or nine—at the pub next door. As he gambled and drank away their benefit money she immersed herself in books.

Even after he walked out of her life she continued to visit the library, just in case he came back. She hated him for leaving, but more than anything else she wanted him to come back. And as she waited for him to swing through the door with his big grin and too-loud voice, she read. The library was her playground, her university. Here she was surrounded by familiar faces. Hello, Cinderella. Cheer up, Tess. Good day, Mr Darcy. As the years passed, The Brothers Grimm became The Brothers Karamazov until one day she picked up a pen and began to write her own stories.

Raindrops streamed down the cheeks of her reflection in the window. She remembered what ‘tristesse’ meant.

After almost a decade in Scotland, Thomas Duval still dreamt in French. Four years of university in Glasgow, followed by a brief internship with Edinburgh publisher Klinsch & McLeish (ending in a spectacular bust-up with the notoriously spiky Dr Klinsch) and then five years building up Tristesse had left him a fluent English speaker trailing a wisp of a French accent along with the added charm of a stray Scottish vowel. But at night, in his dreams, he was once more the golden boy from the Côte d'Azur, raised under hot blue skies, bestride his old Benelli motorbike racing the rich kids in their Ferraris and Lambos along the twisting coast road between Saint-Tropez and Cannes. And always with a different girl riding pillion. Mais, bien sûr.

But somehow despite the sun-soaked childhood, when he'd first arrived in Glasgow something stirred in his soul. He'd always loved Walter Scott, James Hogg, the gloomy heart of the Scottish canon. The first time it rained he walked around the city without an umbrella until he was wet to the skin. He'd never felt so alive, which was ironic, since he came down with a bout of flu and missed the rest of Freshers’ Week. But his affair with Scotland had begun. His family thought he was mad. He ignored them and bought an umbrella. Soon, the tanned limbs of Brigittes and Hélènes gave way to the pale, freckled legs of Karens and Morags.

Still asleep, Tom reached an arm around the shape beside him in the wide bed. He began to mutter in French, a low, rhythmical sound, languid and masculine, capable of snapping knicker elastic at twenty paces, then slid one hand beneath the rumpled sheets—and froze. His smile slipped, replaced with a glower of cheated surprise.

He sat up and flung the covers from the bed. Beside him lay a chunky six-hundred pager. He'd just tried to make sweet love to a manuscript, and not even one worthy of his moves. A glance at the title—The Unbearable Sadness of Daal—brought back last night's bedtime reading: mediocre writing, derivative plot and two hundred pages too long.

He huffed and turned a bleary eye to the small bedroom. Manuscripts littered every surface. Uneven stacks of them sprang from the floor like heroes turned to stone by a Gorgon's stare. He was behind in his reading, as usual. He had put his romantic life on the back burner in favour of pursuing a different prize—glittering success as a publisher. So far he was frustrated on both fronts, not helped by his strict adherence to one of his few rules: never shag a writer—especially not one of your own. He was still looking for The One. Just one critically acclaimed—and more crucially—best-selling book would take his struggling company to another level.

Once showered and dressed he stood over the espresso machine as it gurgled and hissed in protest before grudgingly offering up a shot of treacle-black coffee. Tom drained the cup and immediately poured another. His broad frame filled the narrow galley kitchen like a Rodin bronze in an elevator. The living quarters were crammed into a mezzanine above Tristesse's offices and consisted of two small bedrooms and a holiday camp for bacteria masquerading as a kitchen, littered with plates growing more life than the average Petri dish. Less cordon bleu, more cordoned off.

He juggled a new manuscript and a piece of toast. Concentration fixed on the page he failed to notice that the marmalade he spread thickly over the toast was in fact mayonnaise. He took a bite. Disgusted, he toed open the pedal-bin at the end of the counter—and discarded the manuscript. Swiping a finger across his phone he checked the time.

‘Roddy!’ He barked towards the second bedroom. ‘School!’ There was a thud from inside like a cadaver being dropped by a slippery-fingered mortician, the distinctive chink of many empty beer bottles being inexpertly stepped over and then the door swung open. Out shambled a figure in a state of confusion and a brown corduroy suit.

‘Have you seen my tie?’

‘You mean the brown one,’ mocked Tom, ‘to match the chic suit?’

Roddy stuck out his chin defensively. He was a slightly built man with the sort of boyish face always ID'd when buying a six-pack. He tugged at one of the large lapels. ‘It's not brown,’ he insisted. It flapped like a Basset hound's ear. ‘I'll have you know this is fine Italian tailoring and the young lady who sold it to me called it marrone.’

‘You do know that's just Italian for “brown”, right?’

Roddy ignored him, moving aside manuscripts to continue his search. ‘So have you seen my tie or not?’

‘Hey, careful with those,’ said Tom, waving his toast at the unread scripts. ‘I have a system.’

‘Ah-ha!’ Roddy produced a red bow tie from behind one of the stacks and slipped it around his neck.

‘You're seriously going to wear that to school?’

‘It's a valid choice.’

‘For Yogi Bear, maybe.’

Roddy frowned. ‘That makes no sense. Yogi Bear never wore a bow tie. It was a necktie—and it wasn't even red, it was green. Wait, are you thinking of the Cat in the Hat?’

‘If I pretend I just arrived from France and don't understand anything you're saying will you stop talking?’

‘Just for that I'm having your muesli.’

Roddy swiped a bowl off the draining board, wiped a spoon on his trousers and dived in.

‘Hmm?’ Tom looked up from his reading. ‘We're out of muesli. Haven't bought any in weeks.’

Roddy gagged as he spat out the ancient slurry. ‘Aw, you're kiddin’. That's criminal. That's unsanitary, that is. We live in squalor, you know that?’ He threw down the bowl. ‘I'll get something in the staff room.’ He turned to go and paused in the doorway. ‘Oh, don't forget, you've got Nicola coming in this afternoon.’

Tom grunted. A couple of years ago he'd discovered Nicola Ball, a writer of novels set in the unpromising world of public transport (one notable sex scene in her debut had brought whole new meaning to the phrase ‘double-decker’). Recently, she'd featured on some influential lit. crit. blog, hovering near the middle of a list of ‘Scottish novelists to watch under the age of 30’, and the annoying girl wouldn't stop reminding him about it at every opportunity. However, her sales didn't match her bumptiousness.

A buzzer sounded from downstairs.

‘Get that, will you?’ Tom strolled off, head buried in the latest novel plucked from the slush-pile.

‘No can do,’ spluttered Roddy. ‘I've got Wuthering Heights with my Third Years …’ He checked his watch. ‘In fifteen minutes. Bollocks.’

The buzzer went again and Tom padded resentfully downstairs. Roddy's question trailed after him: ‘When are you going to hire an actual secretary?’ The answer was simple: when he could afford one. Which right now felt a long way off.

The postman might as well have been holding a ticking bomb. He brandished what Tom recognised through long acquaintance as unwelcome correspondence from the bank and credit card company.

‘Lovely morning,’ the postman said cheerily, ‘though there's a bit of rain forecast for later.’

Reluctantly, Tom took the mail, which included half a dozen fat A4 envelopes—more manuscripts—and closed the door. With a dissatisfied grunt, he shuffled the official letters to the bottom of the pile and made his way along the narrow passage to his office, deftly navigating around towers of cardboard boxes filled with expensively produced books fresh from the printer. He shuddered at the financial risk; each title was a long shot of vomit-inducing odds, a fragile paper boat set sail on the roughest publishing market since William Caxton thought ‘Hey, what if I put the ink in here?’

Tom threw the mail onto his desk and sat down heavily. Napoleon glowered up at him. It was a bust of the great Emperor, a gift from Roddy on the launch of Tristesse Books, which Tom was in no doubt also conveyed a pointed comment on his high-handed manner. He looked round his tiny office with its clutter of contracts, press releases and inescapable manuscripts; a battered velour sofa with the stuffing knocked out of it (appropriately) and a couple of low, uncomfortable chairs, perfect to intimidate writers. It wasn't exactly the Palace of Fontainebleau.

He turned his frustration to the morning mail, tearing open the top envelope and removing the bulging manuscript from within. He scanned the cover and blew out his cheeks in disbelief. Then held it out in front of him, squinting at the title to make sure he'd read it correctly. Which he had. There it was, in black and white, Cambria twenty-four point. Quelle horreur.

‘The Endless Anguish of My Father,’ he read aloud, allowing each word its full weight and bombast. ‘By Jane Lockhart.’

Worst title this year? Certainly it was the worst this month. Briefly he pondered summoning the author for a meeting, purely for the satisfaction of telling her just what a brainless title she had concocted and, he felt confident asserting this without condemning himself to the unpleasant task of reading one more word, that she was a hopeless case with no chance of making a career as a novelist. But he was busy. Taking the manuscript in the tips of his fingers, he gave a shudder of disgust.

‘Ms. Lockhart … au revoir.’ And with that he tossed it into the cavernous wastepaper basket by the side of his desk.

CHAPTER 2 (#ubcb252ad-69d3-543f-a7c3-e24152d1e3b1)

‘Tinseltown in the Rain’, The Blue Nile, 1984, Linn Records

THE BOWLER WAS a great idea. She rocked that hat. It was her lucky hat, always had been. Not that Jane could recall specific examples of its effect on her good fortune at this precise moment, but she was sure there must have been some in the past.

It was an awesome hat. It had been a last-second decision to take it to the meeting and she'd plucked it from its hook above the umbrella stand along with her favourite red umbrella. Not that the umbrella was lucky. Who has a lucky umbrella? In fact, weren't they notoriously unlucky objects? Yes, it was bad luck to walk under them. No, that couldn't be right. That was ladders, of course. Open them! You weren't supposed to open them indoors in case … what? Non-specific, umbrella-related doom, she supposed.

Oh god, she was losing it.

It was nerves. The email from Thomas Duval of Tristesse Books inviting her—correction, summoning her—to a Monday morning meeting had arrived last thing on Friday, leaving her all weekend to obsess. It had to be bad news; nothing good ever happened on a Monday morning. But if that were the case then why demand a meeting? If he wasn't interested in publishing her novel, surely he would have rejected her in the customary pro forma fashion, and he hadn't Dear Jane-d her, not yet.

She felt a spike of anticipation, which was instantly brought down by a hypodermic shot of self-doubt. Perhaps he was some sort of sadist who got his kicks torturing writers in person. But that seemed so unlikely. She'd been propping herself up with this line of thinking throughout most of the weekend, extracting every last drop of hope from it, until halfway through the longueur of her Sunday afternoon she decided to Google him and discovered that Thomas Duval was indeed just such a sadist. The Hannibal Lecter of publishing, blogged one aspirant author who'd evidently suffered at his hands. Attila the Hun with a red Biro, recorded another.

She dismissed the opinions of a few affronted authors—all right, fourteen—as a case of sour grapes and sought out a more cool-headed assessment of his reputation. There was scant information available on the Bookseller’s site, the industry's go-to journal, but she dug up half a dozen snippets of news. The names changed, but on each occasion the substance remained the same: breaking news—Thomas Duval falls out acrimoniously with another of his writers, who storms out in high dudgeon, swearing never to write one more word for that arrogant, temperamental sonofabitch.

Well, at least he was consistent.

She jumped on the subway at Kelvinbridge and rode the train to Buchanan Street in the centre of town. By the time she reached the surface, the early rain had given way to patchy sunshine and she enjoyed a pleasant stroll through George Square to the Merchant City. European-style café culture had come late to Glasgow—until 1988 if you said barista to a Glaswegian you risked a punch on the nose. But when it did arrive it came in a tsunami of foaming milk. An area of the city once referred to as the ‘toun’ these days sported sleek cafés on every corner, where, at the first warming ray, outside tables sprouted like sunflowers, and were just as swiftly populated by chattering, sunglasses-wearing crowds who always seemed to be waiting just off screen for their cue.

Jane headed along cobbled Candleriggs past the old Fruit Market, before stopping outside a set of electric gates. One of the residents was leaving and as the gates whirred open she slipped inside, finding herself in a large, sunlit courtyard bordered by a Victorian terrace on one side and a glassy office block on the other.

She made her way over to the far corner and at the door, she inspected the nameplate. This was the place all right. She hadn't really paid attention to the Tristesse Books logo before, but a large version of it was stencilled on the wall: a white letter ‘T’ suspended in a fat blue drop of rain. As she pushed the buzzer it struck her that it wasn't rain at all, but a teardrop.

Jane had been kicking her heels for half an hour, waiting in the hot, cramped Reception room for her meeting with Thomas Duval. She could hear him through the wall, shouting in rapid-fire French. He may not have been ordering a saucisson, but it wasn't difficult to catch the gist—someone was getting it in le neck.

Though his fury wasn't directed at her, with each fresh salvo Jane shrank deeper into the waiting-room chair. After fifteen minutes of listening to him rant she'd contemplated making her excuses and slinking out, but the possibility that he had read and liked The Endless Anguish of My Father was enough to encourage her to stay put and suffer.

Across the room she could see Duval's secretary trying to ignore the furious noises coming from his boss's office. At least, Jane assumed the man sitting at the desk was his secretary. For some reason she'd pictured Thomas Duval's secretary as one of those pencil-skirt wearing, bespectacled ah-Miss-Jones-you're-beautiful types, whereas the figure valiantly shielding the phone receiver from the angry French volcano on the other side of the wall was a twentysomething man in a brown corduroy suit and red bow tie. Now that she studied him carefully, he looked less like a secretary and more as if he was channelling a fifty-year-old schoolteacher.

‘Mm-hmm. Yeah. Oh yeah, he's a wonderful writer. So unremittingly bleak.’ The secretary paused as the caller on the other end of the phone asked a question. ‘No, Tristesse doesn't publish him any more,’ he said haltingly. ‘A little disagreement with …’ He glanced towards Duval's office door, cupping the receiver against the rising din. ‘She's one of my favourites!’ he said, responding to a fresh enquiry. ‘Yes, long-listed for the Booker, you know.’ His left eye twitched. ‘Right after she was sectioned.’ He listened again, one corner of his mouth sinking mournfully. ‘No. She left too.’

This was becoming ridiculous. How long would Duval make her wait in this tiny, airless cellar of a room? For all he knew she had taken time off her actual, proper job to show up at his beck and call. Not that she had a proper job any more. She'd quit the supermarket at the beginning of the year, when they offered her a place on the management trainee programme. She'd started off stacking shelves and here they were offering her a suit and a key to the executive WC. It was a sign; she knew, that if she took it then her life would go into the toilet metaphorically as well, taking her far away from her writing.

In the end it didn't even feel like her decision. She had to write; it was as simple as that. So she jumped, a great, giddy, don't-look-down leap of faith. And here she was. Forty-seven rejection letters later. Savings countable on the fingers of one hand … Was it stuffy in here, or was it her?

She yawned and stretched her legs, knocking the low table in front of her on which perched a stack of teetering manuscripts. They wobbled alarmingly and she dived to steady them, noticing as she did that the top novel was entitled A Comedy in Long Shot. Not a bad title. She immediately compared it with her own, placing each in an imaginary ranking system. Hers scored higher, she felt sure. The Endless Anguish of My Father had been tougher to come up with than the rest of the novel. But the day it popped into her head she knew it was the one. It had the ring of authenticity, rooted in truth, in life; six words that spoke to the eternal verities. And it looked good when she typed it across the cover page.

Something glinted behind the paper stack. A single golden page coiled into a scroll and set on a plinth. It was an award. An inscription ran along its base. She picked it up to read: ‘Thomas Duval. Young European Publisher of the Year, 2010.’ She turned the award another notch. ‘Runner-up.’

‘Miss Lockhart?’

Duval's secretary had crept up on her. Startled, she dropped the award. It landed against the wooden floor with a resounding clang and rolled under a sofa. Apologising profusely, Jane fell to her knees and scrabbled to retrieve it, a part of her brain belatedly registering that the shouting from the office had ceased.

‘What the hell are you doing?

She looked up into the face of Thomas Duval and felt her own flush. He was handsome in a way that would make Greek gods sit around and bitch. It wasn't the rangy stubble, or the thick wave of hair that demanded you run your fingers through its luxuriant tangle, or the intense stare from behind his Clark Kent spectacles. OK, it might have been some of those things. His distracting features were currently arranged to display a mixture of anger and puzzlement, but, she noted with a sinking feeling, they definitely tipped towards anger. She was also vaguely aware of a draught located around her backside and knew then that in her pursuit of the runaway award her skirt had ridden up and currently resided somewhere around her waist. As she covered her modesty (oh, way too late for that) she made a show of polishing the golden award with one corner of her sleeve.

‘I'm so sorry. I didn't mean to—I was just, y'know, touching it. I mean not touching—that sounds like molesting, like I'm some kind of pervert …’ she drew breath, ‘which I'm not.’ She ventured a smile. ‘Young European Publisher of the Year … Runner-up? That's really impressive.’ Don't make a joke. Don't make a joke. ‘I have a swimming certificate.’

Across the room the secretary chuckled, for which she was immensely grateful. Duval silenced him with a scowl. Certain that her submissive kneeling position wasn't helping her case, Jane picked herself up off the floor, laying a hand on the vertiginous stack of manuscripts for leverage. She leaned on the unsteady pile and the scripts toppled over, crashing to the floor. Random pages flew up around her ears.

Duval narrowed his eyes. ‘Who are you?’

She stuck out a hand in greeting. ‘Jane Lockhart …?’ Duval ignored the proffered hand. She withdrew it awkwardly, turning the action into a waving gesture she hoped came across as insouciant. ‘I wrote The Endless Anguish of My Father?’

‘Ah,’ he grunted. ‘Yes.’ He turned his back on her and began to walk away.

So that was it, she thought—another rejection. And I've shown him my pants.

‘What are you waiting for?’ he snapped over his shoulder.

She threw a questioning glance at the secretary, who motioned her to follow the disappearing Duval. Hurriedly gathering up her hat and umbrella she stumbled after him.

She was not sure what compelled her to do so—blame it on the confusion of believing she was about to be unceremoniously ejected onto the street—but by the time he had led her into his office she was again wearing the bowler hat. She was confronted with his broad back as he gestured her curtly into a low seat, then slid behind his desk and looked up. He leaned in with a quizzical expression, mouth half open.

‘It's my lucky hat,’ she pre-empted his question.

‘No one has a lucky hat.’

Something about this man made her want to argue. ‘What about leprechauns?’

He screwed up his face. ‘What?’

‘They're lucky. They wear hats.’ Oh god, she was doing it again. Stop talking. Stop talking right now. ‘Y'know, with the green and the buckle and … Ah … Ah!’ She sat up, raising one finger triumphantly. ‘You can have a thinking-cap.’

He sneered. ‘It's not the same thing at all.’

‘No. No it isn't.’ Sheepishly, she removed the offending bowler. ‘I only wore it to offset the umbrella,’ she confessed, then asked brightly, ‘Have you ever wondered why it's bad luck to open an umbrella indoors?’

Duval gazed at her steadily. ‘The superstition arose during the late 18

century when umbrellas were larger, with heavy, spring-loaded mechanisms and hard metal spokes. Open one in the confines of a drawing room and the consequences could be destructive.’

‘Oh.’

He drew a tired breath and fished a manuscript from under a pile. She recognised it immediately as her own, although the pages appeared crumpled at the corners and was that the brown crescent of a coffee stain on the cover? This must be a good sign. Clearly, the turned-down corners were evidence of the hours Duval had spent reading and then rereading; the stain conjured a long, espresso-fuelled night, his head bent over her novel mesmerised by the spare, elegant prose, those sharp, intelligent eyes tearing up at the emotive tale.

‘I'll be honest with you,’ he said, tossing the well-worn manuscript down on the desk, ‘I put this in the bin without reading a single word.’

Or, there was that.

She looked down and played nervously with her ring. It was made from an old typewriter key, the word ‘backspace’ in black letters on a silver background. She'd bought it with her last pay packet, a fitting gift to launch her on her new career as a novelist. She felt a lump in her throat and swallowed hard. She swore she wouldn't cry in front of him.

‘That title …’ He made a long, sucking sound through his teeth.

She had a feeling it wasn't the only thing that sucked. She glimpsed a straw and clutched at it. ‘But you took it out again.’

‘Hmm?’

‘Of the bin. Something must have made you take it back out.’

‘Yes.’ He fiddled with the small bust of Napoleon. ‘A fly.’

Had he just admitted to using the novel she'd slaved over for the last year and a half as a fly swatter?

‘It was a highly persistent fly,’ he added in a conciliatory tone. He pushed a bored hand through his hair. ‘I'm busy, so I'll keep this brief. I read your novel. I'm afraid it needs work. A lot of work.’

Hot tears pricked her eyes. She blinked furiously, trying to hold back the waterworks. She hadn't cried in years, not since her dad left, and now here was this man making her feel like that little girl again. It wasn't the rejection—she'd shrugged off dozens without resorting to tears. It must be him. The bastard. To actually reject her face to face.

‘But it has potential, so I'm going to publish it.’

What a complete and utter shit. Making her come all the way here just to wait in his stupid little office, only to be told—

Wait. What?

‘Ms. Lockhart?’ He peered into her stunned face. ‘Are you all right?’

‘Publish? Me?’ She just had to check. ‘In a book?’

He gave an exasperated sigh. ‘I'm offering you a two-book deal. It will mean a lot of rewriting—definitely a new title—and neither of us will get rich. But I think you have it in you to be a writer and, unfashionable as it may seem, that is what I came here to find.’

She waited for the punchline, searching his face for the appearance of a grin that would say, ‘only joking’, but it didn't come. He was serious. This man wanted to publish her novel. This kind, wonderful man. There was only one rational response to the news.

She dissolved into tears.

She'd always wondered how she'd feel if—she corrected herself—when the moment finally came and the flood of ‘no's’ was stemmed by one small, clear ‘yes’. In the end it wasn't even a ‘yes’ so much as a ‘oui’. Vive la France! Vive le Candleriggs! But this was more than an air-punching victory, it was … happiness. That's what it felt like. Through great hiccupping sobs she could see him watching her, confused. ‘I'm sorry. I didn't mean to …’she blubbed. ‘It's been so … so long … so many rejections … I have a board.’

‘You have a board?’

‘Of rejection letters. I call it my Board of Pain.’

‘Well,’ he said with a straight face, ‘that's completely normal.’

‘It is?’ Oh good, that was a relief.

‘So, how many publishers turned you down exactly?’

‘All of them,’ she said, palming away tears. ‘Well, obviously not all of them. All of the big ones, I mean.’ She caught his eye. ‘Not that I'm saying you're not big. I'm sure you're very … important. I mean, really, I should have sent you my novel ages ago, given that it's set in Glasgow and so are you.’

‘So why didn't you?’

‘Umm.’ This was awkward. ‘Because I'd never heard of you?’

He grunted.

‘But then I read The Final Stop by Nicola Ball and I loved it and she is really talented and really young and I saw your logo on the spine and, well, here I am.’

She lapsed into a renewed bout of weeping.

The office door swung open and the secretary in the brown suit entered, flourishing a paper tissue from a man-sized box. He'd come prepared. ‘I'm sorry about him. He was like this at uni. Everywhere he went—crying women.’

She took the tissue and blew her nose loudly.

‘Roddy—’said Duval, trying to explain that, as unlikely as it appeared, this time he was not the cause of the great lamentation.

Roddy wagged a finger. ‘Uh-uh. You lot are supposed to be charming. Charmant, n'est-ce pas?’

Jane shook her head, struggling to form words through the wracking sobs.

‘I've told you,’ snapped Duval, ‘never try to talk French to me, you—’

‘Happy!’ Jane's outburst silenced both men. ‘No, really.’ She bounced out of the low seat. ‘I've … I've never been so happy in all my life.’

She hugged a surprised Roddy and then circled round his desk to embrace Duval. Gosh, up close he was very tall. In her exuberance she knocked over her umbrella. It sprang open, an inauspicious red blot in the centre of the room.

But it was probably nothing to worry about.

CHAPTER 3 (#ubcb252ad-69d3-543f-a7c3-e24152d1e3b1)

‘Nine Million Rainy Days’, The Jesus and Mary Chain, 1987, Bianco y Negro

‘THIS IS THE marketing department … And this is sales … And this is publicity.’

‘Hi, I'm Sophie,’ said a shiny young woman with a sleek bob and perfectly applied make-up.

‘Sophie Hamilton Findlay,’ said Tom, ‘three names, three departments. You blame Sophie if no one reviews your book, or if you can't find it in all good bookshops. Don't blame her for not marketing it … I don't give her any money for that.’

They turned a hundred and eighty on the spot.

‘And this is George. He's production.’

A pinched face looked up from a wizened baked potato overflowing with egg mayonnaise.

‘I'm on lunch.’

‘You blame George if the print falls off the page, or if the pages themselves fall out. So, you've met the rest of the team. Any questions?’

‘Well …’ Jane began.

‘Good.’ Duval clapped his hands. ‘Time to get to work.’

When he suggested heading out of the office for their first editorial meeting Jane pictured them moving to a quiet corner of Café Gandolfi sipping espressos and arguing about leitmotifs. He had different ideas. One thinks at walking pace, he pronounced, and took off along Candleriggs at a clip, brandishing her manuscript and a red pen. Andante!

She scurried after him, his loping stride forcing her to trot to keep up. The man thought fast. He did not approve of the modern fashion of editing at a distance, he explained, with notes issued coldly via email; adding with a grin that he preferred to see the whites of his writers’ eyes.

‘Readers are only impressed by two things,’ he said. ‘Either that a novel took just three weeks to write, or that the author laboured three decades.’ He sucked his teeth in disgust. ‘And then dropped dead, preferably before it was published. No one cares about the ordinary writer. The grafter. Like you.’

Ouch. A grafter? Really? She'd been harbouring hopes that she was an undiscovered genius.

‘And publishers are no better.’ He turned onto Trongate, carving a swathe through commuters and desultory schoolchildren, warming to his theme. ‘Do you recall that book about penguins?’

‘Which one?’ The previous year the book charts seemed to be awash with talking penguins, magically realistic penguins, melancholy penguins, there had even been an erotic penguin.

He slapped a hand against her manuscript. ‘My point exactly! One book about penguins sells half a million copies and suddenly you can't move for the waddling little bastards.’ He stopped, slumping against a doorway. His shoulders heaved like a longbow drawing and loosing. ‘The giants are gone,’ he said sadly.

Giants? Penguins? Was every day going to be like this? He set off again at a lick.

‘So many modern editors neglect the great legacy they have inherited. They are uninterested in language or, god forbid, art; and would prefer a mediocre novel they can compare to a hundred others than a great one that fits no easy category. They care only about publicity and book clubs and film tie-ins.’ He spat out the list as if it curdled his stomach. ‘Most editors are little more than cheerleaders, standing on the sidelines waving their pom-poms.’ He turned to her. ‘I have no pom-poms,’ he growled. Then thumped a palm against his chest. ‘I care. I care about the work. I care about your novel.’

He stopped again and she felt she ought to fill the silence that followed. ‘Thanks,’ she said brightly.

Duval cocked his head and looked thoughtful. ‘Of course, it is not a good novel.’

Sonofa—

‘But it could be.’ He pushed a hand through his hair. ‘So I say this to you now, without apology. From this moment, Jane, we will spend every waking hour together until I am satisfied. It will be hard. Lengthy. I will make you sweat.’

Uh, could he hear himself?

‘I will stretch you. Sometimes I will make you beg me to stop.’

Apparently not.

‘I do this not because I am a sadist—whatever you might have heard—I do this to give an ordinary writer a chance to be great.’

That was terrific, she was impressed—moved, even—but could he not give the ‘ordinary writer’ stuff a rest?

They came to a busy intersection. Pedestrians streamed past them. At the kerb the drivers of a bus and a black cab loudly swapped insults over a rear-ender; the aroma of frying bacon fat drifted from a van selling fast food. He ignored them all, shutting out the traffic and the smells and the noise, for her.

‘I promise that no one has ever looked at you the way I shall. Not even your lover.’

Jane swallowed. ‘I don't have a lover,’ she heard herself admit. ‘Right now I mean. I've had lovers, obviously. Not loads. I'm not, y'know, “sex” mad. I don't know why I brought up sex. Or why I put air quotes round it. I'm totally relaxed about … y'know … sex. And yet I just whispered it. Very relaxed. I think it's because you're French. You're all so lalala let's have a bonk and a Gauloise. Oh god. I'm so sorry about … well, me, Mr Duval. Should I call you Mr Duval? It sounds so formal. Maybe I could call you Robert.’

‘You could,’ he said, ‘but my name is Thomas.’

‘Thomas! Yes. I knew that. I was thinking of the other one. From The Godfather? Played the accountant.’

‘Tom.’

‘No, it was definitely Rob—oh, I see. Tom. Short for Thomas. I had a friend called Thomas. Well, when I say “friend” I—’

‘Stop talking.’

‘Yes. Yes, I think that would be a good idea.’ She dropped her head, stuck out a foot and screwed a toe into the pavement.

‘OK,’ he declared. ‘Now our work begins.’

And with those words the months spent at her desk writing for no one but herself were at an end. Now they would embark on a journey of discovery, together, to prepare her novel for … Publication. Suddenly, the sacrifices seemed worth it: losing touch with friends, turning on the central heating only when the ice was inside the windows, baked beans almost every day for three months straight, all to reach this pinnacle of a moment.

‘Do you want a roll and sausage?’ asked Duval.

‘Do I want a—?’

He marched off in the direction of the fast-food van.

‘Morning, Tommy,’ the owner greeted him. ‘The usual?’

‘Aye, Calum, give me some of that good stuff.’ Duval took the sandwich, then showed it excitedly to Jane as if he were a botanist and it a new species of orchid. ‘And not just any sausage, oh no. A square sausage. See how it fits so perfectly inside the thickly buttered soft white bap? Genius! But then, what else would one expect from the nation who gave the world the steam engine, the telephone and the television? This is why I love the Scots. Now, a soupçon of brown sauce.’ He squeezed a drop from the encrusted spout of a plastic bottle, patted down the top of the roll and sank his teeth into it. Paroxysms of delight ensued. ‘And to think that France calls itself the centre of world cuisine.’

She wasn't entirely sure he was joking. And then she realised. He'd gone native.

‘You must try one. I insist.’ He clicked his fingers as if he were ordering another bottle of the ’61 Lafite.

Moments later she stood peering at the sweating sandwich in her hands, and beyond it, Tom's grinning face.

‘OK,’ he said. ‘Now we begin.’

Ten minutes later they sat beside one another in the window of a café next door to his office. Between them lay the ziggurat of her manuscript.

‘Jane,’ he said softly, ‘there is no need to be nervous.’

‘Nervous? Me? No-o-o. Not nervous.’ A coffee machine gurgled and hissed, only partially masking the spin cycle taking place in her stomach. ‘OK, a little bit nervous.’

He smiled. ‘It's OK.’

It was then she realised what was making her nervous. He was being nice to her. The heat had gone out of his fire and brimstone, his voice, typically tense with anger, now soothed like warm ocean waves.

‘Usually I need a run-up before I start editing,’ she said. ‘Y'know: tea, a walk, regrouting the shower.’

‘Or we could just begin?’

‘What, no foreplay?’ Even as she spoke them she was chasing after the words to stop them coming out of her mouth. But it was too late. He gave a small laugh, the sort of laugh your older brother's handsome friend might give his mate's little sister. Jane's embarrassment turned to disappointment. ‘So, where d'you want to start?’

‘Call me crazy, but we could start at the beginning.’

‘OK.’ She nodded rapidly, appearing to give his suggestion serious consideration, hiding her mortification at asking such a dumb question. ‘OK yes.’ She clouted him matily on the arm. ‘You crazy Frenchman.’

He turned the top page of the manuscript. And they began.

He gave great notes. They were acute, considered, wise. Intimate.

As he had promised, the process of editing her novel forced them into a curious form of co-habitation. She would arrive at his office each morning and, following his customary breakfast of roll and sausage and black coffee, they would commence work. At first on opposite sides of his desk, then on the third day he came out and sat on the edge, balancing there comfortably, at ease in his body; a move, Jane did not fail to notice, which put her at eye level with his crotch.

Often she felt like the submissive in a highly specific S&M relationship, one with no physical contact but plenty of verbal discipline. I edit you. I. Edit. You. Ordinarily, she wouldn't have put up with any man who bossed her about as much as Tom did, but theirs was a professional relationship, she reminded herself. So she gave herself permission to be spanked. On the page.

Mostly they worked in his office, or the café next door, and whenever they reached a sticky point they would take to the streets and walk it out like a pulled muscle. Occasionally they decamped to her place. The first time he asked her—no, informed her—of the change of venue came early one morning while she was still half asleep, drowsy with last night's notes. He was on his way over, said the familiar accented voice on the other end of the phone.

When the doorbell rang she was in the shower. She stepped out, dripping, to shout down the corridor that there was a key on the lintel above the door and he should let himself in. It felt natural to give this man the run of her flat. After all, he was going to publish her. When she entered the sitting room she found him sprawled on the floor, propped on one elbow, pages scattered about him, red pen zipping through the manuscript. He looked right at home. And, watching him work steadily, intensely, she realised that he was the first man she'd properly trusted since her dad walked out.

They settled into their routine. Every day it was just the two of them, happily suspended in a bubble of literary discourse and fried egg sandwiches. One Wednesday morning, ten chapters into the edit, Jane breezed through the front door of Tristesse Books.

‘Morning, Roddy.’ She plunked a bulging paper bag on his desk. ‘I made brownies.’

There was an urgent rustle as Roddy tore open the bag. With an appreciative smile, she turned towards Tom's office. She liked Roddy; he was a good influence on Tom. If Tom had a fault—and he did—it was an impulsiveness that shaded into arrogance, and Roddy was the one who called him on it, every time. Although it was dubious how he balanced his job as a replacement English teacher with secretarial duties for Tristesse Books, he exuded an air of moral rectitude along with an insatiable appetite for her home baking. He was Jiminy Cricket to Tom's Pinocchio, she'd informed both men one cool summer night, as they sat outside at Bar 91 amidst the buzz of revellers welcoming the weekend. Tom had almost choked on his pint. Roddy just looked disappointed: couldn't he at least be Yoda to a hot-headed young Skywalker, he'd asked.

‘Uh, Jane. You can't go in there.’

She stopped at the door, one hand poised over the handle.

‘He's got someone with him. They've been in there all night.’

She could hear Tom on the other side, his voice in its by now familiar trajectory, the point and counterpoint of argument, the steady inflection and unwavering logic of his contention. And it hit her. He was giving notes.

To someone else.

She experienced a sudden light-headedness, like an aeroplane cabin depressurising at altitude, and was still reeling when the door opened and a winsomely pretty blonde girl stepped out of the office and collided with her.

‘Ooh, sorry.’

‘Sorry.’

‘No, I should be the one who … sorry.’

They disentangled themselves and the girl introduced herself.

‘Nicola Ball.’

She was wearing a severe black pinafore dress on top of a white shirt buttoned to the neck. Pellucid blue eyes gazed unblinkingly from a perfectly oval face. There was a hint of redness around her eyelids, as if she'd been crying.

‘The Last Stop,’ said Jane delightedly. ‘I loved that book.’

‘Thank you,’ said Nicola, a tremulous smile appearing on pale lips. Then her expression hardened and she cast a dark look back through the doorway to Tom's office. ‘At least someone appreciates me,’ she snarled.

‘Why are you still here?’ Tom's voice boomed out. ‘Stop socialising and start rewriting. Go. Now!’

‘I hate that man,’ Nicola hissed.

As she said it Jane felt an unexpected sense of relief. Nicola hated Tom. Good.

‘Please tell me you're not one of his,’ said Nicola.

‘Uh, one of—? Oh, I see. Well yes, I am—as you say—one of his,’ said Jane, adding an apologetic shrug since Nicola's sombre expression seemed to demand one. ‘Tom's going to publish me.’

Nicola took her hand and patted it consolingly. ‘I'm so sorry.’ She pursed her lips in an expression of graveside condolence, bowed her head and departed.

Jane watched her slip out, the triangle of her pinafore dress swinging like a tolling church bell, and felt herself smile inwardly; whatever Nicola's experience of working with Tom had been, it bore little resemblance to her own.

‘Jane?’ he called from the office. ‘Is that you?’

She never tired of hearing him say her name. She floated inside on a cloud of happiness ready to embark on the next leg of their voyage of collaboration and constructive criticism, of intellectual discussion and high-minded debate.

‘Your notes,’ Jane spluttered. ‘Your notes are burning cigarettes stubbed out on the bare arm of my creativity.’ She stepped away from his desk only to return immediately. ‘Oh, and there is no such thing as constructive criticism. The phrase reeks of foul-tasting medicine forced down gagging throats “for your own good”. Constructive criticism is a fallacy; weasel words designed to lure innocent writers like me into an ambush. This chapter is too long. There's too much set-up. This plotline doesn't pay off. Uh, perhaps that's because you cut the set-up? This character is underwritten. Show, don't tell! This chapter is still too long. I like this scene, this is a great scene—it must be cut.’ She stood before him, her face flushed, her breath shallow and rapid.

‘Are you quite finished?’ Tom responded with irritating calm.

She brushed her fringe from her eyes and sniffed. ‘Yes.’

‘Good, then we shall continue.’

Two months into the edit and Jane had lost all sense of perspective. Was he a brilliant editor or, despite his earlier disavowal, simply a sadist who enjoyed torturing novelists? Currently, she was leaning towards the latter. She half suspected that were she to pull at the antiquarian volume of Frankenstein squatting atop his bookcase a secret door would swing open to reveal a shadowy chamber and the gaunt, moaning figures of his other novelists, hanging from bloodstained bulldog clips, notes on their last drafts carved into their skin with his annoying and ubiquitous little red pen. It pained her to admit it, but Nicola Ball's expression of pity had been prophetic.

She occupied her usual spot, squirming in the low chair opposite his desk. They sat in silence as he went through her latest revisions, the only sounds the dismissive flick of manuscript pages and the scratch of that damn pen. She watched as he adjusted the bust of Napoleon, turning it precisely one inch clockwise, then two inches anti-clockwise. He did this with some regularity, but it was only latterly she'd realised that the tic inevitably preceded his delighted unearthing of a particularly egregious flaw in her manuscript.

‘This makes no sense at all,’ he muttered on cue, striking out a paragraph with a flurry of red slashes.

‘What are you cutting now?’ Sometime on Thursday she had given up any attempt to hide her irritation.

He looked up and she was sure that his smug, infuriating face evinced surprise at her presence. Why are you even here? it said. What could you possibly have to contribute to this process? You are merely the writer. Jane struggled out of her chair—she'd meant to leap up for added effect, but her prone position made it tricky.

‘I've changed my mind,’ she said, reaching across the desk for her manuscript. ‘I don't want to be published. By you. Thank you very much.’

She had no practical reason for retrieving the manuscript; if she'd really meant what she said she could simply have walked out of the door, gone home and printed out another—but she wanted to take something away from him. She had gathered an armful of pages when she felt his hand close gently but firmly around her wrist. She was startled; was it the first time he'd touched her?

Last week she'd been surprised that he hadn't kissed her in the French style—not that French style—when she'd finally signed her contract and left with a cheque that would pay for a fabulous trip to Moscow (the one in Ayrshire, natch). It had seemed to her that he started to lean in over the signature page for the customary embrace, but pulled back at the last moment. He'd been close enough for her to feel the leading edge of his well-groomed stubble and smell his skin. She'd half expected his natural scent to be Lorne sausage, but instead he was a heady mixture of sandalwood and new books. Then why his hesitation? She had swilled copious amounts of mouthwash that morning in preparation for the signing. Just on the off chance, you understand. So it wasn't her breath. Perhaps he simply didn't fancy the idea of kissing her. Well, his loss.

He was still holding her wrist. And, for a moment, she wondered what it would be like to do it right here on his desk.

‘You can't do that,’ he said firmly.

‘I know,’ she said, shocked at where her mind had taken her. ‘Knowing my luck I'd probably end up with Napoleon in my back.’

Jane saw that he was looking at her in utter bafflement. She had seen a similar expression on his face earlier that day over a complicated sandwich and a cappuccino at the café next door. Pushing his coffee to one side he had complained that until meeting her he'd imagined his English not only to be fluent, but idiomatic—and prided himself on being almost certainly the only living Frenchman who knew his bru from his broo. However, in conversation with her he often felt like a foreigner, he said. No. Correction. Like an alien. She hadn't said so, but secretly she enjoyed the thought that she unsettled him.

She shrugged off his hand, glowered at him to get it out of her system and then with a sigh lowered herself into the knee-height chair once more. She waved at him to continue. ‘You were cutting what was no doubt my favourite passage.’

‘Bon,’ he said, gratified, and scored viciously through another paragraph.

As she watched his scurrilous red pen she wondered when it had all gone wrong. A few weeks ago she had even made him her flourless chocolate cake. Though now she thought about it the baking interlude had arisen because one of his notes had sent her into a tailspin and she had been unable to write a single word for days. Yes, she realised, he was turning her into a crazy person.

As he droned on detailing the endless failings in her novel, she decided something had to be done. What was it about Tom that made her heed his every pronouncement? It wasn't just the sculpted stubbly chin, it was the self-confidence acquired from years at an exclusive French boys’ school followed by university degrees acquired in two languages. The closest she'd come to university was on the tills at the supermarket selling lager to boozed-up students on a Saturday night.

She found herself scanning the contents of the bookcase that filled the wall behind his desk, running her eye across the well-thumbed classics, vintage and modern, dozens of them seeded with slips of paper marking favourite passages. It was a display designed to impress. But then with a little rush she realised that she'd read most of them in the library in Dennistoun during those long afternoons. She sat a little straighter—she probably knew them as well as he did. Her gaze settled on a volume of Greek myths and an idea struck her.

The problem was territorial. Like the myth of the giant Antaeus, who drew his strength from his connection to the earth, all she had to do was separate him from the square mile of the Merchant City and she was sure their relationship would achieve new levels of equality and harmony. She needed to pluck him from his comfort zone and repot him. She smiled to herself—she knew just the place.

CHAPTER 4 (#ulink_1bc74451-77c1-5456-a816-d3ad9af75b3a)

‘Laughter in the Rain’, Neil Sedaka, 1974, Polydor Records

‘YOU SAID IT WAS a Highland cottage.’

‘Yes.’

‘I heard you distinctly. An old crofthouse nestling at the end of a glen, you said.’

‘Yes.’

‘But …’

‘Yes?’

‘You made it sound …’ he hunted for the right word ‘… picturesque.’

Ignoring his accusing tone, she motioned towards the small stone dwelling with a gesture of ‘ta-da!’

His eye roved suspiciously across the outside. A chimney stack balanced like a drunken man on the roof; weeds sprouted from slate tiles that had been discarded rather than laid; of the two windows cut roughly into the facing wall, one was bricked up and the other colonised by a family of squabbling, drab-feathered birds. The whole structure tilted at a twenty-degree angle, leaning into a relentless, biting wind that howled down the most desolate glen he had ever seen.

‘Does it leak?’

Her mouth gaped, offended. ‘Of course it doesn't leak.’ She turned away, fished out a great iron key from her weekend bag, slid it into the stiff lock and shouldered her way inside. ‘So long as it doesn't rain,’ she mumbled.

There was a sucking squelch from behind her.

‘Of course. What else should I expect? Just wonderful.’

He stood up to his ankles in a sloppy brown puddle. Jane wasn't sure which looked more soggy—his trousers or his face. When she had suggested the trip up north to work on the manuscript—to finish it once and for all—she told him to bring suitable outdoor wear. So, when he'd picked her up in his car that morning, she couldn't help but notice with some surprise that he was wearing orange trainers. She declined to comment at the time; he'd obviously picked them as a reminder that he didn't have to listen to her—he was the one who gave the notes in this relationship. Well, look where it got you, she thought smugly. I say potato, you say pomme de terre.

The muddied orange trainers steamed gently in front of the fireplace as Jane stoked the sputtering fire. Beside her, Tom shivered in a faded tweed armchair, hugging himself and grumbling.

‘What's wrong now? You haven't stopped moaning since we left Glasgow.’ She threw on a handful of kindling. ‘Don't you like it here? This was my granny's cottage.’

He snorted. ‘You're telling me your granny was a crofter?’

She noted that he didn't say ‘farmer’, but used the Scottish expression. He was amazing. His English. Was amazing. Not him. He was annoying. ‘She worked on the line at Templeton's Carpets,’ she explained.

‘So, she bought this place?’ He sounded incredulous at the idea anyone would put down hard-earned money for such a dump.

‘She won it. Back in the ‘80s. One of those dodgy timeshare offers came through the door.’ He gave her a blank expression. ‘Y'know the sort of thing: You have already won one of these great prizes: a wicker basket of dried flowers, a canoe, or a Highland hideaway. All you had to do to claim your prize—and it was always the dried flowers—was sit in a conference room in an Aviemore hotel and listen to some guy's sales pitch. But my granny hit the jackpot.’ She motioned, quiz-hostess style. ‘The Highland hideaway.’

‘And to think she could have walked away with a canoe.’ He cast a disgruntled eye around the dim room. ‘If you'd wanted a change of scene there are perfectly good cafés on Byres Road,’ he grumbled. ‘With Wi-Fi.’ He flicked the switch on a standard lamp sporting a fetching floral shade. The room remained dim. ‘And electricity!’ he barked. ‘This is not natural.’

‘What are you talking about? Outside that door is actual nature.’

‘Nature is for German hikers in yellow cagoules.’ He scraped the chair across the floor, closer to the fire. ‘Can't you turn this thing up?’

Jane tossed on another log and retreated to the kitchen to make coffee. It was a while since she'd been up to the cottage. When she'd begun the novel she imagined retreating to its splendid isolation. In her head it would go like this: during the day she would alternate writing by the window (that would be the one window with glass in the frame) with long walks in the countryside where she would be inspired by clouds and daffodils. At night she would curl up by the fire and continue scratching out her masterpiece. She had decamped to the cottage to live the dream, only to find the power out, as usual. Four hours later her laptop battery died and she lost half of the chapter she'd been working on. That was the end of the romance. She returned to Glasgow the following morning and hadn't been back since.

The cupboard contained a single jar of Nescafé, a tin of powdered milk and a suspicious trail of what she hoped were only mouse droppings. She warmed the drink on an old Primus stove. It pained her to admit it, but Tom was right; the place was little more than a ruin. But it was her ruin. Her gran had left it to her, not her mum. Gran hadn't approved of mum's choice of husband—she was an astute judge of character—and though there was no grand title or country estate to disinherit her from, there was the cottage.

Tom called from the other room, imploring her through chattering teeth to hurry up with the coffee. She put up with his hectoring, thankful he wasn't asking where to find the toilet. She was delaying the inevitable moment when she had to explain the purpose of the spade by the front door.

He had moved from the armchair onto the hearth, and as she approached she saw he was holding her manuscript. She sighed. It was straight to business then.

‘Sit down.’

‘You're incredibly bossy, anyone ever told you that?’ she complained, sitting nonetheless.

‘Yes. Now be quiet and listen. This is the chapter where Janet goes to her favourite sweetshop—’

‘Glickman's,’ she interrupted. It was on the London Road. A Glasgow institution, the oldest amongst dozens in that sweet tooth of a city. Her dad used to take her on a Saturday morning to spend her pocket money: a bag of Snowies for her—moreish drops of sweet white chocolate covered in rainbow-coloured sprinkles; and a quarter of tangy Soor Plooms for him that made her mouth tingle. He always let her pay for his—a warning sign of things to come.

Jane folded her arms, bracing herself for his critique. ‘OK, so what's wrong with it? Wait, don't tell me. It's the Soor Plooms—too specific—they won't understand the reference in Croydon.’

He said nothing and instead reached into his bag for a small, white paper bag. It rustled with unbearable familiarity.

‘Are those from Glickman's?’ she asked, already knowing the answer.

He chuted the contents into his hand. Out tumbled white chocolate Snowies.

She felt sick.

He held out a single sweet with the quiet unblinking confidence of a man who knows that when he wants to kiss a girl it is inevitable; at some point she will kiss him back. He offered the sweet to her, both of them understanding that she would succumb.

‘Your dad—’ He shrugged. ‘Forgive me, Janet's dad—was an alky and a total bamstick, but you took that pain and turned it into a novel which, for the most part, isn't awful.’

‘I'm not Janet.’

He made a face as if to say, oh really? ‘A less scrupulous publisher would insist on calling this a memoir,’ he said with a nod towards the manuscript. ‘He would conveniently skip over the few sections that are fiction and sell a hundred thousand more copies. Readers love pain, particularly if they know someone really suffered.’

‘I'm not Janet.’

‘Now, for the sake of editorial distance, you need to let her go.’

‘Editorial distance?’ She felt the sag of disappointment. So this was just about the edit.

‘Yes. What else?’ Tom leant forward. ‘Janet is about to have a new life on the page. Soon, your character will belong to thousands of readers—’ he grimaced ‘—well, hundreds. You two need to go your separate ways.’ He paused. ‘So we are going to make a new memory. One that belongs to you, not her. Here, in this picturesque shit-hole.’

He pushed the Snowie towards her. ‘You are not Janet.’

‘I can't. I haven't had once since Dad …’

‘I know.’

Slowly, she parted her lips. He popped the sweetie on her tongue and her mouth filled with warm chocolate and the crunch of hundreds and thousands.

In the morning she found him asleep in the armchair, arms wrapped around her manuscript. Was it possible to feel jealous of your own novel? Nothing had happened after Snowie-gate; he had behaved like a gentleman, keeping the conversation professional, the mood workmanlike. Which was absolutely fine with her. A-OK. Hunky-flipping-dory. After all, it was perfectly natural for a modern young woman to invite an attractive man she barely knew to a cottage in the middle of nowhere. A cottage with one bedroom. There was no pretext; this weekend was all about the sex. Text. The fire had burned itself out overnight. No, that wasn't a metaphor. She gathered a handful of kindling from the basket next to the grate and built a new one.

At his suggestion after breakfast they spent the day walking the length of the glen. Around lunchtime it opened out to a dark, glassy loch. The sun was breaking through the thick layer of cloud when they came to a large flat rock by the edge of the water and Tom insisted on stopping. He reached into a chic leather messenger bag, and Jane was sure it was to retrieve the manuscript, but to her surprise he produced a couple of gourmet sandwiches from Berits & Brown and a portable espresso maker, from which he proceeded to make the most delicious cup of coffee she'd ever tasted.

‘What are you doing here?’ she asked as they ate. The clouds had cleared and now the sun hung awkwardly overhead, lost in an empty sky like a walker who's realised he's been holding his Ordnance Survey map upside down for the last four and a half hours.

‘It's a nice day, I thought we should get out.’

‘No, I don't mean here. I mean here here. In Scotland. At the risk of sounding small-town, can I ask what a Frenchman from the Côte d'Azur is doing running a publishing company in Glasgow?’

He lowered his espresso cup. ‘You know, Saint-Tropez is a lot like Glasgow.’

‘It is?’

‘No. Not one little bit.’

‘So, you fancied a change of scene?’

‘I had to get out. I was living in a pop song. A French pop song. Do you know how many hours of sunshine the Côte d'Azur receives annually?’

‘How many?’

‘A fucking lot.’

‘Wait, you're saying you came to Scotland … for the rain?’

He shrugged and rooted around the ground before picking up a smooth, circular stone.

‘Why Glasgow?’ Jane continued. ‘You do know it's Edinburgh that has the book festival, right? And if you want to be a publisher isn't Paris a more obvious choice? Or London, or New York?’

Gripping the stone in the curve of his index finger and thumb he sent it skimming across the flat loch. It sank on the second bounce. ‘Merde!’ He turned to Jane. ‘The world has been overrun by ersatz writers, musicians and artists. All we have are writers who write about writing, singers who purposely break up with their lovers so that they may sing about heartache. I came because Glasgow is still somewhere real. And I came to find someone real.’

His eyes definitely did not bore into her soul. Real eyes didn't do that. So why did she feel so utterly naked?

‘Jane, I think I came to find y—’

‘Guten Tag!’

Above them on the edge of the loch stood a party of walkers with bare knees, ruddy cheeks—and yellow cagoules. Their round smiles deepened into Teutonic puzzlement when Jane and Tom's laughter shattered the stillness.

They returned to the cottage. The weather closed in shortly before they reached shelter and they were both soaked through. When she entered the room, towelling her hair dry, she found him occupying his usual place in the armchair by the fire.

‘We need to talk about the sex,’ he announced.

The sex. Le Sex. Finally, she thought.

There were, however, cultural proprieties to be observed. A nice girl simply didn't acquiesce to such an indecent proposal. ‘I don't think we do,’ she said, folding her arms across her chest. ‘I am not talking about “the sex” with you. You've got some cheek, you know that? Just because I asked you up here doesn't mean I'm ready to jump into bed.’

‘The sex,’ he said evenly, ‘in chapter seventeen.’ He opened her novel to the relevant page.

‘Oh,’ she said, unfolding her arms. ‘Yes. That sex.’

Tom stabbed a finger at a section halfway down the page. ‘I'm confused. What is going on here?’

‘What are you talking about? It's …’ She circled behind him, craning her neck for a sight of the offending paragraph. ‘Perfectly clear.’

‘Are they having sex? Because if they are, you should know that it's improbable.’

‘Ah, well,’ she wagged a finger, ‘that's because I'm writing it from the woman's perspective—something you clearly don't understand.’

‘Right.’ He held the page at arm's length, rotating it first one way and then the other, as if looking at it from another angle would make the scene clearer. ‘So where exactly is her leg meant to be?’

Oh, the man was maddening! Jane swatted him with her towel and made a grab for the manuscript. ‘Give that back!’

He was too fast for her. He led her around the room, dangling the novel at arm's length, just out of her grasp. At first she requested him curtly but politely to desist in his childish behaviour, but when he ignored her she resorted to a tirade of foul language. He doubled up with laughter at hearing her swear. Which meant that he failed to notice the trailing cord of the standard lamp as he swept around the room once more.

‘Ow!’ He slammed into the floor, his knee taking the brunt. ‘I hate this place!’

She stood over him to gloat. ‘Serves you right. It's a good scene. It's full-blooded, lusty—’

Tom rubbed his knee mournfully. ‘—physically impossible.’

With one final cry of irritation she lunged for the manuscript. He teased it out of reach and with his other hand swept her legs from under her. She crumpled, sinking down beside him. So near to him now she saw that he had kept his promise—no lover had ever looked at her this way.

‘It's not impossible,’ she said, swallowing. ‘You just have to be … bendy.’

That raised an eyebrow. ‘This is drawn from personal experience?’

They were close enough to breathe each other's air.

‘Well, that's not something you're ever going to find out.’ She let the words hang there. Just the two of them in the overwhelming silence of the cottage. Not a milk frother to disturb the stillness.

A small part of her couldn't help but observe the situation from a distance: an unfairly attractive Frenchman, a hearthrug in front of a crackling log fire, a Highland cottage. If she'd written it, he would have struck it out. Infuriating, exasperating man.

She waited. In all the romances she'd read people kissed adverbially. Hungrily, madly, passionately. She wondered what it would be like to kiss him. Wondered about the hardness of his bristles and the softness of his lips. Wondered if she should make the first move.