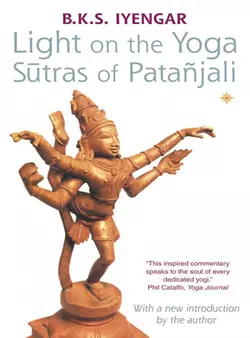

Light on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali

Литагент HarperCollins

Note that due to the limitations of some ereading devices not all diacritical marks can be shown.BKS Iyengar’s translation and commentary on these ancient yoga sutras has been described as the “bible” of yoga.This edition contains an introduction by BKS Iyengar, as well as a foreword by Godfrey Devereux, author of Dynamic Yoga.Patanjali wrote this collection of yoga wisdom over 2,000 years ago. They are amongst the world’s most revered and ancient teachings and are the earliest, most holy yoga reference.The Sutras are short and to the point – each being only a line or two long. BKS Iyengar has translated each one, and provided his own insightful commentary and explanation for modern readers.The Sutras show the reader how we can transform ourselves through the practice of yoga, gradually developing the mind, body and emotions, so we can become spiritually evolved.The Sutras are also a wonderful introduction to the spiritual philosophy that is the foundation of yoga practise.The book is thoroughly cross-referenced, and indexed, resulting in an accessible and helpful book that is of immense value both to students of Indian philosophy and practitioners of yoga.

B.K.S. IYENGAR

Light on the Yoga

Sutras of Patañjali

Copyright (#ulink_4526e0fe-8092-585c-83ab-150fa1a65a79)

Thorsons

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/)

Thorsons is a trademark HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

Published by Thorsons 1996

Published by The Aquarian Press 1993

First published in Great Britain by George Allen & Unwin, 1966

Copyright © B.K.S. Iyengar 1993

B.K.S. Iyengar asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007145164

Ebook Edition © JUNE 2012 ISBN: 9780007381623

Version: 2017-02-21

Dedication (#ulink_9b07acc8-604a-511c-b6e5-18f5bc397b55)

This work is my offering to

my Invisible, First and Foremost Guru

Lord Patañjali

Contents

Cover (#ue94a6c37-98e9-56ff-8c4f-b24eaa5c7a0e)

Title Page (#uf8425bb6-13cc-5aa6-a192-fe0fe958ff7a)

Copyright (#uac87ece3-5e65-5d3b-9bc5-762f63288c33)

Dedication (#u7e2a3c97-d313-5231-be21-b8e226e41051)

Foreword by Godfrey Devereux (#u2e05922e-5d2d-53cc-b3de-61aef99c986d)

Introduction to the New Edition by B.K.S. Iyengar (#uce30ae6d-7b92-5e2b-b8d1-39ce319991c7)

Patañjali (#ucb0b363a-f3eb-540e-9e77-da2c27458bd2)

The Yoga Sutras (#u3a985006-10a6-5a63-8944-dd7f4a453604)

Themes in the Four Padas (#ufd07e0a2-ecf5-59ec-9ee1-843240f0898d)

Samadhi Pada

Sadhana Pada (#ulink_70de480e-94c9-5de6-a7cf-550e9187105a)

Vibhuti Pada (#ulink_173e9141-f0aa-5cb8-aac2-cd7b76d5ff57)

Kaivalya Pada (#ulink_8efd46f0-c49c-517c-9f26-1b87f9e21f34)

Yoga Sutras Text, translation and commentary (#u04cfa326-5a41-555b-9fe1-a2836bd83b65)

Part I Samadhi Pada (#uec85d178-d790-58de-89a3-63bc7007bf87)

Part II Sadhana Pada (#litres_trial_promo)

Part III Vibhuti Pada (#litres_trial_promo)

Part IV Kaivalya Pada (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Appendix I A Thematic Key to the Yoga Sutras (#litres_trial_promo)

Appendix II Interconnection of Sutras (#litres_trial_promo)

Appendix III Alphabetical Index of Sutras (#litres_trial_promo)

Appendix IV Yoga in a Nutshell (#litres_trial_promo)

List of Tables and Diagrams (#litres_trial_promo)

Glossary (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Invocatory Prayers (#litres_trial_promo)

A note from Sir Yehudi Menuhin (#litres_trial_promo)

Hints on Transliteration and Pronunciation (#litres_trial_promo)

List of important terms in the text (#litres_trial_promo)

On Yoga (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

By the same author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Foreword by Godfrey Devereux, author of Dynamic Yoga (#ulink_ee533314-1863-5cd6-a67e-548c4e5ebb0a)

Patañjali’s Yoga Sutras are the bible of yoga. However, their inaccessibility in the hands of scholars and academics has left yoga practitioners adrift with neither chart nor compass. B.K.S. Iyengar’s translation, based on over fifty years of dedicated and accomplished practice and teaching, is unique in its relevance and utility to contemporary yoga practitioners. The depth of his practice and understanding shines through his elucidation of the often terse and obscure sutras. Iyengar’s ability to elucidate Patañjali in pragmatic terms is an extension of his clarification of the subtlety and integrity of yoga practice. This is most evident in the rigorous precision with which he understands and articulates the body in yoga postures. However, it goes further and much deeper than that. In his unique investigation of alignment, Iyengar not only reveals the therapeutic necessity of stuctural integrity in the body, but also its subtle and equally necessary impact on the flow of energy and consciousness in the mind.

What Iyengar has proved, for those willing to apply themselves to test it, is that the apparent divide between matter and spirit, body and soul, and physical and spiritual is only that: apparent. Through his insistence on structural integrity he has opened the spiritual doorway to millions of people for whom the mind would otherwise never give up its subtleties. Here, in his presentation of Patañjali, that door is flung wide open. This is especially clear, to even the least academically minded student, in his profound and practical interpretations of the sutras relating to Asana and pranayama. Here, especially, Iyengar’s genius comes as a great gift of clarity and insight that can only deepen the understanding and support the practice of any keen student.

Iyengar’s incomparable experience as an Indian teacher of Westerners, combined with his experience as a Brahmin and participant in a genuine lineage of the yoga tradition, gives his perspective an authority and authenticity that is all too often lacking. It offers a lucid and pragmatic interpretation of the insights and subtleties of yoga’s root guru. To practice yoga without the profound and panoramic inner cartography of the Yoga Sutras is to be adrift in a difficult and potentially dangerous ocean. To use that map without the compass of Iyengar’s deep and authoritative experience, is to handicap oneself unnecessarily. No yoga practitioner should be without this classic and invaluable work.

Introduction to the New Edition by B. K. S. Iyengar (#ulink_fcb84738-4a82-56ab-abfa-b2e68d6bd9ab)

I express my sense of gratitude to Thorsons, who are bringing out my Light on the Yoga Sutras of Patañjali in this new attractive design, as a feast not only for the physical eyes but also for the intellectual and spiritual eye.

As a mortal soul, it is a bit of an embarrassment for me with my limited intelligence to write on the immortal work of Patañjali on the subject of yoga.

If God is considered the seed of all knowledge (sarvajña bijan), Patañjali is all knower, all wise (sarvajñan), of all knowledge. The third part of his Yoga Sutras (the vibuti pada) makes it clear to us that we should respect him as a knower of all knowledge and a versatile personality.

It is impossible, even for sophisticated minds, to comprehend fully what knowledge he had. We find him speaking on an enormous range of subjects – art, dance, mathematics, astronomy, astrology, physics, chemistry, psychology, biology, neurology, telepathy, education, time and gravitational theory – with a divine spiritual knowledge.

He was a perfect master of cosmic energy; he knew the pranic energy centres in the body; his intelligence (buddhi) was as clean and clear as crystal and his words express him as a pure perfect being.

Patañjali’s sutras make use of his great versatility of language and mind. He clothes the righteous and virtuous aspects of religious matters with a secular fabric and in so doing is able to skilfully present the wisdom of both the material and the spiritual world, blending them as a universal culture.

Patañjali fills each sutra with his experiential intelligence, stretching it like a thread (sutra), and weaving it into a garland of pearls of wisdom to flavour and savour by those who love and live in yoga, as wise-men in their lives.

Each sutra conveys the practice as well as the philosophy behind the practice, as a practical philosophy for aspirants and seekers (sadhakas) to follow in life.

What is sadhana?

Sadhana is a methodical, sequential means to accomplish the sadhana’s aims in life. The sadhana’s aims are right duty (dharma), a rightful purpose and means (artha), right inclinations (kama) and ultimate release or emancipation (moksa).

If dharma is the atonement of duty (dharma sastra), artha is the means to purification of action (karma sastra). Our inclinations (kama) are made good through study of sacred texts and growth towards wisdom (svadhyaya and jñana sastra), and emancipation (moksa) is reached through devotion (bhakti sastra) and meditation (dhyana sastra).

It is dharma that uplifts man who has fallen physically, mentally, morally, intellectually and spiritually, or who is about to fall. Therefore, dharma is that which upholds, sustains and supports man.

These aims are all stages on the road to perfect knowledge (vedanta). The term vedanta comes from Veda, meaning knowledge, and anta meaning the end of knowledge. The true end of knowledge is emancipation and liberation from all imperfections. Hence the journey, or vedanta, is an act of pursuit of the vision of wisdom to transform one’s conduct and actions in order to experience the ultimate reality of life.

Due to lack of knowledge or misunderstanding, fear, love of the self, attachment and aversion with respect to the material world, one’s actions and conduct become disturbed. This disturbance shows as lust (kama), wrath (krodha), greed (lobha), infatuation (moha), intoxication (mada) and malice (matsarya). All of these emotional turbulences affect the psyche by veiling the intelligence.

The yoga sadhana of Patañjali comes to us as a penance in order to minimise or eradicate these disturbed and destructive emotive thoughts and the actions that accrue from them.

The yoga sadhana of Patañjali

The Sadhana is a rhythmic, three-tiered practice (sadhana-traya), covering the eight aspects or petals of yoga in a capsule as kriya yoga, the yoga of action, whereby all actions are surrendered to the Divinity (see Sutra II.1 in the sadhana pada). These three tiers (sadhana-traya) represent the body (kaya), the mind (manasa) and the speech (vak).

Hence:

At the level of the body, tapas, or the drive towards purity, develops the student through practice on the path of right action (karma marga).

At the level of the mind, through careful study of the self and the mind in it’s consciousness, the student develops self-knowledge, svadhyaya, leading to the path of wisdom (jñanamarga).

Later, profound meditation using the voice to pronounce the universal aum (see Sutras I.27 and 28) directs the self to abandon ego (ahamkara), and to feel virtuousness (silata), and so it becomes the path of devotion (bhakti marga).

Tapas is a burning desire for ascetic, devoted sadhana, through yama, niyama, Asana and pranayama. This cleanses the body and senses (karmendriya and jñanendriya), and frees one from afflictions (klesa nivrtti).

Svadhyaya means the study of the Vedas, spiritual scriptures that define the real and the unreal, or the study of one’s own self (from the body to the self). This study of spiritual science (atma sastra) ignites and inspires the student for self-progression. Thus svadhyaya is for restraining the fluctuations (mano vrtti nirodha) and in its wake comes tranquillity (samadhana citta) in the consciousness. Here the petals of yoga are pratyahara and dharana, besides the former aspects of tapas.

Isvara pranidhana is the surrender of oneself to God, and is the finest aspect of yoga sadhana. Patañjali explains God as a Supreme Soul, who is eternally free from afflictions, unaffected by actions and their reactions or by their residue. He advises one to think of God through repeating His name (japa), with profound thoughtfulness (arthabhavana), so that the seeker’s speech can become sanctified and thus the seed of imperfection (dosa bija) or defect be eradicated (dosa nivrtti) once and for all.

From here on, his sadhana continues uninterruptedly with devotion (anusthana). This practice, (sadhana-ana) will go on generating knowledge until he touches the towering wisdom (see Sutra II.28 in the sadhana pada).

Through the capsule of kriya yoga, Patañjali explains the cosmogony of nature and how to ultimately co-ordinate nature, in body, mind and speech. Through discipline tapas, study – svadhyaya, and devotion – Isvara pranidhana, the student can become free from nature’s erratic play, remaining in the abode of the Self.

In Sutra II.19 in the sadhana pada, Patañjali identifies the distinguishable, or physically manifest (visesa) marks and the non-distinguishable, or subtle, (avisesa) elements which comprise existence and which are transformed to take the individual to the noumenal (linga) state. Then through astanga yoga, coupled with sadhana-traya, all nature, or prakrti (alinga) becomes one, merged.

He defines the distinguishable marks of nature as the five elements: earth, water, fire, air and ether; (pañca-bhuta); the five organs of action (karmendriya); the five senses of perception (jñanendriya), and the mind (manas). The non-distinguishable marks are defined as the tanmatra (sound, touch, shape, taste and smell) and pride (ahamkara). These twenty-two principles have to merge in mahat (linga), and then dissolve in nature (prakrti). The first sixteen distinguishable marks are brought under control by tapas – practice and discipline, the six undistinguishable ones by svadhyaya – study and abhyasa – repetition. Nature, prakrti, and mahat,the Universal Consciousness, become one through and in Isvara pranidhana.

At this point all oscillations of the gunas that shape existence terminate and prakrtijaya, a mastery over nature, takes place. From this quiet silence of prakrti, Self (purusa) shines forth like the never fading sun.

In the Hathayoga Pradipika Svatmarama explains something very similar. He says that the body, being inert, tamasic, is uplifted to the level of the active, rajasic, mind through Asana and pranayama with yama and niyama. When the body is made as vibrant as the mind, through study, svadhyaya and through practice and repetitions, abhyasa, both mind and body are lifted towards the noumenal state of sattva guna. From sattva guna the sadhaka follows Isvara pranidhana to become a gunatitan (free from gunas).

Patañjali also addresses Svatmarama’s explanation of the different capabilities and therefore expectations for weak (mrdu), average (madhyama) and outstanding (adhimatra) students (see I.22). He guides the most basic beginner (the tamasic sadhaka) to follow yama, niyama, Asana, and pranayama as tapas, to become madhyadhikarins (vibrant and rajasic), and to intensify this practice into pratyahara (withdrawal of the senses) and dharana (intense focus and concentration) as their path of study, svadhyaya, and then to proceed towards sattva guna through dhyana (devotion), and to gunatitan (the state uninfluenced by the gunas) into samadhi, the most profound state of meditiation – through Isvara pranidhana.

By this graded practice, according to the level of the sadhaka, all sadhakas have to touch the purusa (hrdayasparsi), sooner or later through tivra samvega sadhana (I.21).

Hence, kriya yoga sadhana-traya envelopes all the aspects of astanga yoga, each complimenting (puraka) and supplementing (posaka) the others. When sadhana becomes subtle and fine, then tapas, svadhyaya and Isvara pranidhana, work in unison with the eight-petals of astanga yoga, and the sadhanaka’s mind (manas), intelligence (buddhi) and ‘I’ ness or ‘mineness’ (ahamkara) are sublimated. Only then does he become a yogi. In him friendliness, compassion, gladness and oneness (samanata) flows benevolently in body, consciousness and speech to live in beatitude (divya ananda).

This is the way of the practice (sadhana), as explained by Patañjali that lifts even a raw sadhaka to reach ripeness in his sadhana and experience emancipation.

I am indebted to Thorsons for this special edition of Light on the Yoga Sutras of Patañjali, enabling readers to take a dip in sadhana and savour the nectar of immortality.

B.K.S. IYENGAR

14 December 2001

Patañjali (#ulink_419ac2c1-7979-5f06-ab99-a3abbcc3103e)

First I would like to tell you something about Patañjali, who he was and what was his lineage. Historically, Patañjali may have lived some time between 500 and 200 B.C., but much of what we know of the master of yoga is drawn from legends. He is referred to as a svayambhu, an evolved soul incarnated of his own will to help humanity. He assumed human form, experienced our sorrows and joys, and learned to transcend them. In the Yoga Sutras he described the ways of overcoming the afflictions of the body and the fluctuations of the mind: the obstacles to spiritual development.

Patañjali’s words are direct, original and traditionally held to be of divine provenance. After more than twenty centuries they remain fresh, fascinating and all-absorbing, and will remain so for centuries to come.

Patañjali’s 196 aphorisms or sutras cover all aspects of life, beginning with a prescribed code of conduct and ending with man’s vision of his true Self. Each word of the sutras is concise and precise. As individual drops of rain contribute towards the formation of a lake, so each word contained in the sutras conveys a wealth of thought and experience, and is indispensable to the whole.

Patañjali chose to write on three subjects, grammar, medicine and yoga. The Yoga Sutras, his culminating work, is his distillation of human knowledge. Like pearls on a thread, the Yoga Sutras form a precious necklace, a diadem of illuminative wisdom. To comprehend their message and put it into practice is to transform oneself into a highly cultured and civilized person, a rare and worthy human being.

Though I have practised and worked in the field of yoga for more than fifty years, I may have to practice for several more lifetimes to reach perfection in the subject. Therefore, the explanation of the most abstruse sutras lies yet beyond my power.

It is said that once Lord Visnu was seated on Adisesa, Lord of serpents, His couch, watching the enchanting dance of Lord siva. Lord Visnu was so totally absorbed in the dance movements of Lord siva that His body began to vibrate to their rhythm. This vibration made Him heavier and heavier, causing Adisesa to feel so uncomfortable that he was gasping for breath and was on the point of collapse. The moment the dance came to an end, Lord Visnu’s body became light again. Adisesa was amazed and asked his master the cause of these stupendous changes. The Lord explained that the grace, beauty, majesty and grandeur of Lord siva’s dance had created corresponding vibrations in His own body, making it heavy. Marvelling at this, Adisesa professed a desire to learn to dance so as to exalt his Lord. Visnu became thoughtful, and predicted that soon Lord siva would grace Adisesa to write a commentary on grammar, and that he would then also be able to devote himself to perfection in the art of dance. Adisesa was over-joyed by these words and looked forward to the descent of Lord siva’s grace.

Adisesa then began to meditate to ascertain who would be his mother on earth. In meditation, he had the vision of a yogini by the name of Gonika who was praying for a worthy son to whom she could impart her knowledge and wisdom. He at once realized that she would be a worthy mother for him, and awaited an auspicious moment to become her son.

Gonika, thinking that her earthly life was approaching its end, had not found a worthy son for whom she had been searching. Now, as a last resort, she looked to the Sun God, the living witness of God on earth and prayed to Him to fulfil her desire. She took a handful of water as a final oblation to Him, closed her eyes and meditated on the Sun. As she was about to offer the water, she opened her eyes and looked at her palms. To her surprise, she saw a tiny snake moving in her palms who soon took on a human form. This tiny male human being prostrated to Gonika and asked her to accept him as her son. This she did and named him Patañjali.

Pata means falling or fallen and añjali is an oblation. Añjali also means ‘hands folded in prayer’. Gonika’s prayer with folded hands thus bears the name Patañjali. Patañjali, the incarnation of Adisesa, Lord Visnu’s bearer, became not only the celebrated author of the Yoga Sutras but also of treatises on Ayurveda and grammar.

He undertook the work at Lord siva’s command. The Mahabhasya, his great grammar, a classical work for the cultivation of correct language, was followed by his book on Ayurveda, the science of life and health. His final work on yoga was directed towards man’s mental and spiritual evolution. All classical dancers in India pay their homage to Patañjali as a great dancer.

Together, Patañjali’s three works deal with man’s development as a whole, in thought, speech and action. His treatise on yoga is called yoga darsana. Darsana means ‘vision of the soul’ and also ‘mirror’. The effect of yoga is to reflect the thoughts and actions of the aspirant as in a mirror. The practitioner observes the reflections of his thoughts, mind, consciousness and actions, and corrects himself. This process guides him towards the observation of his inner self.

Patañjali’s works are followed by yogis to this day in their effort to develop a refined language, a cultured body and a civilized mind.

The Yoga Sutras (#ulink_deb7e82e-1cb8-58fb-8bc4-25e6436cf020)

The book is divided into four chapters or padas (parts or quarters), covering the art, science and philosophy of life. The 196 sutras are succinct, precise, profound, and devout in approach. Each contains a wealth of ideas and wisdom to guide the aspirant (sadhaka) towards full knowledge of his own real nature. This knowledge leads to the experience of perfect freedom, beyond common understanding. Through ardent study of the sutras, and through devotion, the sadhaka is finally illumined by the lamp of exalted knowledge. Through practice, he radiates goodwill, friendliness and compassion. This knowledge, gained through subjective experience gives him boundless joy, harmony and peace.

As with the Bhagavad Gita, different schools of thought have interpreted the sutras in various ways, placing the emphasis on their particular path towards Self-Realization, whether on karma (action), jñana (wisdom) or bhakti (devotion). Each commentator bases his interpretations on certain key or focal themes and weaves around them his thoughts, feelings and experiences. My own interpretations are derived from a lifelong study of yoga, and from experiences gained from the practice of Asana, pranayama and dhyana. These are the key aspects of yoga which I use to interpret the sutras in the simplest and most direct way, without departing from traditional meanings given by successive teachers.

The four chapters or padas of the book are:

1 Samadhi pada (on contemplation)

2 Sadhana pada (on practice)

3 Vibhuti pada (on properties and powers)

4 Kaivalya pada (on emancipation and freedom)

The four padas correspond to the four varñas or divisions of labour; the four asramas or stages of life; the three guñas or qualities of nature and the fourth state beyond them (sattva, rajas, tamas and guatita) and the four purusarthas or aims of life. In the concluding sutra of the fourth pada, Patañjali speaks of the culmination of purusarthas and gunas as the highest goal of yoga sadhana. These concepts must have been wholly understood in Patañjali’s time, and therefore implicit in the earlier chapters, for him to speak of them explicitly only at the very end of the book.

The ultimate effect of following the path laid out by Patañjali is to experience the effortless, indivisible state of the seer.

The first pada amounts to a treatise on dharmasastra, the science of religious duty. Dharma is that which upholds, sustains, and supports one who has fallen or is falling, or is about to fall in the sphere of ethics, physical or mental practices, or spiritual discipline. It appears to me that Patañjali’s whole concept of yoga is based on dharma, the law handed down in perpetuity through Vedic tradition. The goal of the law of dharma is emancipation.

If dharma is the seed of yoga, kaivalya (emancipation) is its fruit. This explains the concluding sutra, which describes kaivalya as the state which is motiveless and devoid of all worldly aims and qualities of nature. In kaivalya, the yogi shines in his own intelligence which sprouts from the seer, atman, independent of the organs of action, senses of perception, mind, intelligence and consciousness. Yoga is, in fact, the path to kaivalya.

Dharma, the orderly science of duty is part of the eightfold path of yoga (astanga yoga), which Patañjali describes in detail. When the eight disciplines are followed with dedication and devotion, they help the sadhaka to become physically, mentally and emotionally stable so that he can maintain equanimity in all circumstances. He learns to know the Supreme Soul, Brahman, and to live in speech, thought and action in accordance with the highest truth.

Samadhi Pada

The first chapter, samadhi pada, defines yoga and the movement of the consciousness, citta vrtti. It is directed towards those who are already highly evolved to enable them to maintain their advanced state of cultured, matured intelligence and wisdom. Rare indeed are such human souls who experience samadhi early in life, for samadhi is the last stage of the eightfold path of yoga. Samadhi is seeing the soul face to face, an absolute, indivisible state of existence, in which all differences between body, mind and soul are dissolved. Such sages as Hanuman, suka, Dhruva, Prahlada, sankaracarya, Jñanesvar, Kabir, Svami Ramdas of Maharastra, Ramakrsna Paramahamsa and Ramata Maharsi, evolved straight to Kaivalya without experiencing the intermediate stages of life or the various stages of yoga. All the actions of these great seers arose from their souls, and they dwelled throughout their lives in a state of unalloyed bliss and purity.

The word samadhi is made up of two components. Sama means level, alike, straight, upright, impartial, just, good and virtuous; and adhi means over and above, i.e. the indestructible seer. Samadhi is the tracing of the source of consciousness – the seer – and then diffusing its essence, impartially and evenly, throughout every particle of the intelligence, mind, senses and body.

We may suppose that Patañjali’s intention, in beginning with an exegesis of samadhi, was to attract those rare souls who were already on the brink of Self-Realization, and to guide them into experiencing the state of nonduality itself. For the uninitiated majority, the enticing prospect of samadhi, revealed so early in his work, serves as a lamp to draw us into yogic discipline, which will refine us to the point where our own soul becomes manifest.

Patañjali describes the fluctuations, modifications and modulations of thought which disturb the consciousness, and then sets out the various disciplines by which they may be stilled. This has resulted in yoga being called a mental sadhana (practice). Such a sadhana is possible only if the accumulated fruits derived from the good actions of past lives (samskaras) are of a noble order. Our samskaras are the fund of our past perceptions, instincts and subliminal or hidden impressions. If they are good, they act as stimuli to maintain the high degree of sensitivity necessary to pursue the spiritual path.

Consciousness is imbued with the three qualities (gunas) of luminosity (sattva), vibrancy (rajas) and inertia (tamas). The gunas also colour our actions: white (sattva), grey (rajas) and black (tamas). Through the discipline of yoga, both actions and intelligence go beyond these qualities and the seer comes to experience his own soul with crystal clarity, free from the relative attributes of nature and actions. This state of purity is samadhi. Yoga is thus both the means and the goal. Yoga is samadhi and samadhi is yoga.

There are two main types of samadhi. Sabija or samprajñata samadhi is attained by deliberate effort, using for concentration an object or idea as a ‘seed’. Nirbija samadhi is without seed or support.

Patañjali explains that before samadhi is experienced the functioning of consciousness depends upon five factors: correct perception, misperception (where the senses mislead), misconception or ambiguousness (where the mind lets one down), sleep, and memory. The soul is pure, but through the sullying or misalignment of consciousness it gets caught up in the spokes of joys and sorrows and becomes part of suffering, like a spider ensnared in its own web. These joys and sorrows may be painful or painless, cognizable or incognizable.

Freedom, that is to say direct experience of samadhi, can be attained only by disciplined conduct and renunciation of sensual desires and appetites. This is brought about through adherence to the ‘twin pillars’ of yoga, abhyasa and vairagya.

Abhyasa (practice) is the art of learning that which has to be learned through the cultivation of disciplined action. This involves long, zealous, calm, and persevering effort. Vairagya (detachment or renunciation) is the art of avoiding that which should be avoided. Both require a positive and virtuous approach.

Practice is a generative force of transformation or progress in yoga, but if undertaken alone it produces an unbridled energy which is thrown outwards to the material world as if by centrifugal force. Renunciation acts to shear off this energetic outburst, protecting the practitioner from entanglement with sense objects and redirecting the energies centripetally towards the core of being.

Patañjali teaches the sadhaka to cultivate friendliness and compassion, to delight in the happiness of others and to remain indifferent to vice and virtue so that he may maintain his poise and tranquillity. He advises the sadhaka to follow the ethical disciplines of yama and niyama, the ten precepts similar to the Ten Commandments, which govern behaviour and practice and form the foundation of spiritual evolution. He then offers several methods through which consciousness detaches itself from intellectual and emotional upheavals and assumes the form of the soul – universal, devoid of all personal and material identity. The sadhaka is now filled with serenity, insight and truth. The soul, which until now remained unmanifest, becomes visible to the seeker. The seeker becomes the seer: he enters a state without seed or support, nirbija samadhi.

Sadhana Pada

In the second chapter, sadhana pada, Patañjali comes down to the level of the spiritually unevolved to help them, too, to aspire to absolute freedom. Here he coins the word kriyayoga. Kriya means action, and kriyayoga emphasizes the dynamic effort to be made by the sadhaka. It is composed of eight yogic disciplines, yama and niyama, Asana and pranayama, pratyahara and dharana, dhyana and samadhi. These are compressed into three tiers. The tier formed by the first two pairs, yama and niyama, Asana and pranayama, comes under tapas (religious spirit in practice). The second tier, pratyahara and dharana, is self-study (svadhyaya). The third, dhyana and samadhi, is Isvara pranidhana, the surrender of the individual self to the Universal Spirit, or God (Isvara).

In this way, Patañjali covers the three great paths of Indian philosophy in the Yoga Sutras. Karmamarga, the path of action is contained in tapas; jñanamarga, the path of knowledge, in svadhyaya; and bhaktimarga, the path of surrender to God, in Isvara pranidhana.

In this chapter, Patañjali identifies avidya, spiritual ignorance, as the source of all sorrow and unhappiness. Avidya is the first of the five klesas, or afflictions, and is the root of all the others: egoism, attachment, aversion and clinging to life. From these arise desires, sowing the seeds of sorrow.

Afflictions are of three types. They may be self-inflicted, hereditary, or caused through imbalance of elements in the body. All are consequences of one’s actions, in this or previous lifetimes, and are to be overcome through practice and renunciation in the eight yogic disciplines which cover purification of the body, senses and mind, an intense discipline whereby the seeds are incinerated, impurities vanish, and the seeker reaches a state of serenity in which he merges with the seer.

For one who lacks ethical discipline and perfect physical health, there can be no spiritual illumination. Body, mind and spirit are inseparable: if the body is asleep, the soul is asleep.

The seeker is taught to perform Asanas so that he becomes familiar with his body, senses and intelligence. He develops alertness, sensitivity, and the power of concentration. pranayama gives control over the subtle qualities of the elements – sound, touch, shape, taste and smell. Pratyahara is the withdrawal into the mind of the organs of action and senses of perception.

Sadhana pada ends here, but Patañjali extends dharana, dhyana and samadhi, the subtle aspects of sadhana, into the next chapter, vibhuti pada. These three withdraw the mind into the consciousness, and the consciousness into the soul.

The journey from yama to pratyahara, described in sadhana pada, ends in the sea of tranquillity, which has no ripples. If citta is the sea, its movements (vrttis) are the ripples. Body, mind and consciousness are in communion with the soul; they are now free from attachments and aversions, memories of place and time. The impurities of body and mind are cleansed, the dawning light of wisdom vanquishes ignorance, innocence replaces arrogance and pride, and the seeker becomes the seer.

Vibhuti Pada

The third chapter speaks of the divine effects of yoga sadhana. It is said that the sadhaka who in this state has full knowledge of past, present and future, as well as of the solar system. He understands the minds of others. He acquires the eight supernatural powers or siddhis: the ability to become small and large, light and heavy, to acquire, to attain every wish, to gain supremacy and sovereignty over things.

These achievements are dangerous. The sadhaka is cautioned to ignore their temptations and pursue the spiritual path.

Sage Vyasa’s commentary on the sutras gives examples of those who became ensnared by these powers and those who remained free. Nahusa, who belonged to the mortal world, became the Lord of heaven, but misused his power, fell from grace and was sent back to earth in the form of a snake. Urvasi, a famous mythical nymph, the daughter of Nara Narayana (the son of Dharma and grandson of Brahma), became a creeping plant. Ahalya, who succumbed to sensual temptation, was cursed by Gautama and became a stone. On the other hand, Nandi, the bull, reached Lord siva. Matsya, the fish, became Matsyendranath, the greatest hatha yogi on earth.

If the sadhaka succumbs to the lure of the siddhis, he will be like a person running away from a gale only to be caught in a whirlwind. If he resists, and perseveres on the spiritual path, he will experience kaivalya, the indivisible, unqualified, undifferentiated state of existence.

Kaivalya Pada

In the fourth chapter, Patañjali distinguishes kaivalya from samadhi. In samadhi, the sadhaka experiences a passive state of oneness between seer and seen, observer and observed, subject and object. In kaivalya, he lives in a positive state of life, above the tamasic, rajasic and sattvic influences of the three gunas of nature. He moves in the world and does day-to-day work dispassionately, without becoming involved in it.

Patañjali says it is possible to experience kaivalya by birth, through use of drugs, by repetition of mantra, or by tapas (intense, disciplined effort) and through samadhi. Of these, only the last two develop mature intelligence and lead to stable growth.

Man may make or mar his progress through good actions or bad. Yogic practices lead to a spiritual life; non-yogic actions bind one to the world. The ego, ahamkara, is the root cause of good and bad actions. Yoga removes the weed of pride from the mind and helps the seeker to trace the source of all actions, the consciousness, wherein all past impressions (samskaras) are stored. When this ultimate source is traced through yogic practices, the sadhaka is at once freed from the reactions of his actions. Desires leave him. Desire, action and reaction are spokes in the wheel of thought, but when consciousness has become steady and pure, they are eliminated. Movements of mind come to an end. He becomes a perfect yogi with skilful actions. As wick, oil and flame combine to give light, so thought, speech and action unite, and the yogi’s knowledge becomes total. For others, whose knowledge and understanding are limited, an object may be one thing, experience of the object another, and the word quite different from both. These vacillations of mind cripple one’s capacity for thought and action.

The yogi differentiates between the wavering uncertainties of thought processes and the understanding of the Self, which is changeless. He does his work in the world as a witness, uninvolved and uninfluenced. His mind reflects its own form, undistorted, like a crystal. At this point, all speculation and deliberation come to an end and liberation is experienced. The yogi lives in the experience of wisdom, untinged by the emotions of desire, anger, greed, infatuation, pride, and malice. This seasoned wisdom is truth-bearing (rtambhara prajña). It leads the sadhaka towards virtuous awareness, dharma megha samadhi, which brings him a cascade of knowledge and wisdom. He is immersed in kaivalya, the constant burning light of the soul, illuminating the divinity not only in himself, but also in those who come in contact with him.

I end this prologue with a quotation from the Visnu Purana given by sri Vyasa in his commentary on the Yoga Sutras: ‘Yoga is the teacher of yoga; yoga is to be understood through yoga. So live in yoga to realize yoga; comprehend yoga through yoga; he who is free from distractions enjoys yoga through yoga.’

(#ulink_01744293-3a3c-57dd-af4c-45740f0cb371)Themes in the Four Padas

I: Samadhi Pada (#ulink_ad4b969a-aa2d-5c05-8e71-6b611a869651)

Patañjali’s opening words are on the need for a disciplined code of conduct to educate us towards spiritual poise and peace under all circumstances.

He defines yoga as the restraint of citta, which means consciousness. The term citta should not be understood to mean only the mind. Citta has three components: mind (manas), intelligence (buddhi) and ego (ahamkara) which combine into one composite whole. The term ‘self’ represents a person as an individual entity. Its identity is separate from mind, intelligence and ego, depending upon the development of the individual.

Self also stands for the subject, as contrasted with the object, of experience. It is that out of which the primeval thought of ‘I’ arises, and into which it dissolves. Self has a shape or form as ‘I’, and is infused with the illuminative, or sattvic, quality of nature (prakrti). In the temples of India, we see a base idol, an idol of stone that is permanently fixed. This represents the soul (atman). There is also a bronze idol, which is considered to be the icon of the base idol, and is taken out of the temple in procession as its representative, the individual self. The bronze idol represents the self or the individual entity, while the base idol represents the universality of the Soul.

Eastern thought takes one through the layers of being, outwards from the core, the soul, towards the periphery, the body; and inwards from the periphery towards the core. The purpose of this exploration is to discover, experience and taste the nectar of the soul. The process begins with external awareness: what we experience through the organs of action or karmendriyas (the arms, legs, mouth, and the organs of generation and excretion) and proceeds through the senses of perception or jñanendriyas (the ears, eyes, nose, tongue and skin). That awareness begins to penetrate the mind, the intelligence, the ego, the consciousness, and the individual self (asmita), until it reaches the soul (atma). These sheaths may also be penetrated in the reverse order.

Asmita’s existence at an empirical level has no absolute moral value, as it is in an unsullied state. It takes its colour from the level of development of the individual practitioner (sadhaka). Thus, ‘I-consciousness’ in its grossest form may manifest as pride or egoism, but in its subtlest form, it is the innermost layer of being, nearest to the atman. Ahamkara, or ego, likewise has changing qualities, depending on whether it is rajasic, tamasic or sattvic. Sattvic ahamkara usually indicates an evolved asmita.

The chameleon nature of asmita is apparent when we set ourselves a challenge. The source of the challenge lies in the positive side of asmita, but the moment fear arises negatively, it inhibits our initiative. We must then issue a counter-challenge to disarm that fear. From this conflict springs creation.

Asana, for example, offers a controlled battleground for the process of conflict and creation. The aim is to recreate the process of human evolution in our own internal environment. We thereby have the opportunity to observe and comprehend our own evolution to the point at which conflict is resolved and there is only oneness, as when the river meets the sea. This creative struggle is experienced in the headstand: as we challenge ourselves to improve the position, fear of falling acts to inhibit us. If we are rash, we fall, if timorous, we make no progress. But if the interplay of the two forces is observed, analysed and controlled, we can achieve perfection. At that moment, the asmita which proposed and the asmita which opposed become one in the Asana and assume a perfect form. Asmita dissolves in bliss, or satcitananda (purity-consciousness-bliss).

Ahamkara, or ego, the sense of ‘I’, is the knot that binds the consciousness and the body through the inner sense, the mind. In this way, the levels of being are connected by the mind, from the soul, through the internal parts, to the external senses. The mind thus acts as a link between the objects seen, and the subject, the seer. It is the unifying factor between the soul and the body which helps us to uncover layer after layer of our being until the sheath of the self (jivatman) is reached.

These layers, or sheaths, are the anatomical, skeletal, or structural sheath (annamaya kosa); the physiological or organic sheath (pranamaya kosa); the mental or emotional sheath (manomaya kosa); the intellectual or discriminative sheath (vijñanamaya kosa); and the pure blissful sheath (anandamaya kosa). These kosas represent the five elements of nature, or prakrti: earth, water, fire, air and ether. Mahat, cosmic consciousness, in its individual form as citta, is the sixth kosa, while the inner soul is the seventh kosa. In all, man has seven sheaths, or kosas, for the development of awareness.

The blissful spiritual sheath is called the causal body (karana sarira), while the physiological, intellectual and mental sheaths form the subtle body (suksma sarira), and the anatomical sheath the gross body (karya sarira). The yoga aspirant tries to understand the functions of all these sheaths of the soul as well as the soul itself, and thereby begins his quest to experience the divine core of being: the atman.

The mind permeates and engulfs the entire conscious and unconscious mental process, and the activities of the brain. All vital activities arise in the mind. According to Indian thought, though mind, intelligence and ego are parts of consciousness, mind acts as the outer cover of intelligence and ego and is considered to be the eleventh sense organ. Mind is as elusive as mercury. It senses, desires, wills, remembers, perceives, recollects and experiences emotional sensations such as pain and pleasure, heat and cold, honour and dishonour. Mind is inhibitive as well as exhibitive. When inhibitive, it draws nearer to the core of being. When exhibitive, it manifests itself as brain in order to see and perceive the external objects with which it then identifies.

It should be understood that the brain is a part of the mind. As such, it functions as the mind’s instrument of action. The brain is part of the organic structure of the central nervous system that is enclosed in the cranium. It makes mental activity possible. It controls and co-ordinates mental and physical activities. When the brain is trained to be consciously quiet, the cognitive faculty comes into its own, making possible, through the intelligence, apprehension of the mind’s various facets. Clarity of intelligence lifts the veil of obscurity and encourages quiet receptivity in the ego as well as in the consciousness, diffusing their energies evenly throughout the physical, physiological, mental, intellectual and spiritual sheaths of the soul.

What is soul?

God, Paramatman or Purusa Visesan, is known as the Universal Soul, the seed of all (see 1.24). The individual soul, jivatman or purusa, is the seed of the individual self. The soul is therefore distinct from the self. Soul is formless, while self assumes a form. The soul is an entity, separate from the body and free from the self. Soul is the very essence of the core of one’s being.

Like mind, the soul has no actual location in the body. It is latent, and exists everywhere. The moment the soul is brought to awareness of itself, it is felt anywhere and everywhere. Unlike the self, the soul is free from the influence of nature, and is thus universal. The self is the seed of all functions and actions, and the source of spiritual evolution through knowledge. It can also, through worldly desires, be the seed of spiritual destruction. The soul perceives spiritual reality, and is known as the seer (drsta).

As a well-nurtured seed causes a tree to grow, and to blossom with flowers and fruits, so the soul is the seed of man’s evolution. From this source, asmita sprouts as the individual self. From this sprout springs consciousness, citta. From consciousness, spring ego, intelligence, mind, and the senses of perception and organs of action. Though the soul is free from influence, its sheaths come in contact with the objects of the world, which leave imprints on them through the intelligence of the brain and the mind. The discriminative faculty of brain and mind screens these imprints, discarding or retaining them. If discriminative power is lacking, then these imprints, like quivering leaves, create fluctuations in words, thoughts and deeds, and restlessness in the self.

These endless cycles of fluctuation are known as vrttis: changes, movements, functions, operations, or conditions of action or conduct in the consciousness. Vrttis are thought-waves, part of the brain, mind and consciousness as waves are part of the sea.

Thought is a mental vibration based on past experiences. It is a product of inner mental activity, a process of thinking. This process consciously applies the intellect to analyse thoughts arising from the seat of the mental body through the remembrance of past experiences. Thoughts create disturbances. By analysing them one develops discriminative power, and gains serenity.

When consciousness is in a serene state, its interior components, intelligence, ego, mind and the feeling of ‘I’, also experience tranquillity. At that point, there is no room for thought-waves to arise either in the mind or in the consciousness. Stillness and silence are experienced, poise and peace set in and one becomes cultured. One’s thoughts, words and deeds develop purity, and begin to flow in a divine stream.

Study of consciousness

Before describing the principles of yoga, Patañjali speaks of consciousness and the restraint of its movements.

The verb cit means to perceive, to notice, to know, to understand, to long for, to desire and to remind. As a noun, cit means thought, emotion, intellect, feeling, disposition, vision, heart, soul, Brahman. Cinta means disturbed or anxious thoughts, and cintana means deliberate thinking. Both are facets of citta. As they must be restrained through the discipline of yoga, yoga is defined as citta vrtti nirodhah. A perfectly subdued and pure citta is divine and at one with the soul.

Citta is the individual counterpart of mahat, the universal consciousness. It is the seat of the intelligence that sprouts from conscience, antahkarana, the organ of virtue and religious knowledge. If the soul is the seed of conscience, conscience is the source of consciousness, intelligence and mind. The thinking processes of consciousness embody mind, intelligence and ego. The mind has the power to imagine, think, attend to, aim, feel and will. The mind’s continual swaying affects its inner sheaths, intelligence, ego, consciousness and the self.

Mind is mercurial by nature, elusive and hard to grasp. However, it is the one organ which reflects both the external and internal worlds. Though it has the faculty of seeing things within and without, its more natural tendency is to involve itself with objects of the visible, rather than the inner world.

In collaboration with the senses, mind perceives things for the individual to see, observe, feel and experience. These experiences may be painful, painless or pleasurable. Through their influence, impulsiveness and other tendencies or moods creep into the mind, making it a storehouse of imprints (samskaras) and desires (vAsanas), which create excitement and emotional impressions. If these are favourable they create good imprints; if unfavourable they cause repugnance. These imprints generate the fluctuations, modifications and modulations of consciousness. If the mind is not disciplined and purified, it becomes involved with the objects experienced, creating sorrow and unhappiness.

Patañjali begins the treatise on yoga by explaining the functioning of the mind, so that we may learn to discipline it, and intelligence, ego and consciousness may be restrained, subdued and diffused, then drawn towards the core of our being and absorbed in the soul. This is yoga.

Patañjali explains that painful and painless imprints are gathered by five means: pramana, or direct perception, which is knowledge that arises from correct thought or right conception and is perpetual and true; viparyaya, or misperception and misconception, leading to contrary knowledge; vikalpa, or imagination or fancy; nidra or sleep; and smrti or memory. These are the fields in which the mind operates, and through which experience is gathered and stored.

Direct perception is derived from one’s own experience, through inference, or from the perusal of sacred books or the words of authoritative masters. To be true and distinct, it should be real and self-evident. Its correctness should be verified by reasoned doubt, logic and reflection. Finally, it should be found to correspond to spiritual doctrines and precepts and sacred, revealed truth.

Contrary knowledge leads to false conceptions. Imagination remains at verbal or visual levels and may consist of ideas without a factual basis. When ideas are proved as facts, they become real perception.

Sleep is a state of inactivity in which the organs of action, senses of perception, mind and intelligence remain inactive. Memory is the faculty of retaining and reviving past impressions and experiences of correct perception, misperception, misconception and even of sleep.

These five means by which imprints are gathered shape moods and modes of behaviour, making or marring the individual’s intellectual, cultural and spiritual evolution.

Culture of consciousness

The culture of consciousness entails cultivation, observation, and progressive refinement of consciousness by means of yogic disciplines. After explaining the causes of fluctuations in consciousness, Patañjali shows how to overcome them, by means of practice, abhyasa, and detachment or renunciation, vairagya.

If the student is perplexed to find detachment and renunciation linked to practice so early in the Yoga Sutras, let him consider their symbolic relationship in this way. The text begins with atha yoganusAsanam. AnusAsanam stands for the practice of a disciplined code of yogic conduct, the observance of instructions for ethical action handed down by lineage and tradition. Ethical principles, translated from methodology into deeds, constitute practice. Now, read the word ‘renunciation’ in the context of sutra I.4: ‘At other times, the seer identifies with the fluctuating consciousness.’ Clearly, the fluctuating mind lures the seer outwards towards pastures of pleasure and valleys of pain, where enticement inevitably gives rise to attachment. When mind starts to drag the seer, as if by a stout rope, from the seat of being towards the gratification of appetite, only renunciation can intervene and save the sadhaka by cutting the rope. So we see, from sutras I.1 and I.4, the interdependence from the very beginning of practice and renunciation, without which practice will not bear fruit.

Abhyasa is a dedicated, unswerving, constant, and vigilant search into a chosen subject, pursued against all odds in the face of repeated failures, for indefinitely long periods of time. Vairagya is the cultivation of freedom from passion, abstention from worldly desires and appetites, and discrimination between the real and the unreal. It is the act of giving up all sensuous delights. Abhyasa builds confidence and refinement in the process of culturing the consciousness, whereas vairagya is the elimination of whatever hinders progress and refinement. Proficiency in vairagya develops the ability to free oneself from the fruits of action.

Patañjali speaks of attachment, non-attachment, and detachment. Detachment may be likened to the attitude of a doctor towards his patient. He treats the patient with the greatest care, skill and sense of responsibility, but does not become emotionally involved with him so as not to lose his faculty of reasoning and professional judgement.

A bird cannot fly with one wing. In the same way, we need the two wings of practice and renunciation to soar up to the zenith of Soul realization.

Practice implies a certain methodology, involving effort. It has to be followed uninterruptedly for a long time, with firm resolve, application, attention and devotion, to create a stable foundation for training the mind, intelligence, ego and consciousness.

Renunciation is discriminative discernment. It is the art of learning to be free from craving, both for worldly pleasures and for heavenly eminence. It involves training the mind and consciousness to be unmoved by desire and passion. One must learn to renounce objects and ideas which disturb and hinder one’s daily yogic practices. Then one has to cultivate non-attachment to the fruits of one’s labours.

If abhyasa and vairagya are assiduously observed, restraint of the mind becomes possible much more quickly. Then, one may explore what is beyond the mind, and taste the nectar of immortality, or Soul-realization. Temptations neither daunt nor haunt one who has this intensity of heart in practice and renunciation. If practice is slowed down, then the search for Soul-realization becomes clogged and bound in the wheel of time.

Why practice and renunciation are essential

Avidya (ignorance) is the mother of vacillation and affliction. Patañjali explains how one may gain knowledge by direct and correct perception, inference and testimony, and that correct understanding comes when trial and error ends. Here, both practice and renunciation play an important role in gaining spiritual knowledge.

Attachment is a relationship between man and matter, and may be inherited or acquired.

Non-attachment is the deliberate process of drawing away from attachment and personal affliction, in which, neither binding oneself to duty nor cutting oneself off from it, one gladly helps all, near or far, friend or foe. Non-attachment does not mean drawing inwards and shutting oneself off, but involves carrying out one’s responsibilities without incurring obligation or inviting expectation. It is between attachment and detachment, a step towards detachment, and the sadhaka needs to cultivate it before thinking of renunciation.

Detachment brings discernment: seeing each and every thing or being as it is, in its purity, without bias or self-interest. It is a means to understand nature and its potencies. Once nature’s purposes are grasped, one must learn to detach onself from them to achieve an absolute independent state of existence wherein the soul radiates its own light.

Mind, intelligence and ego, revolving in the wheel of desire (kama), anger (krodha), greed (lobha), infatuation (moha), pride (mada) and malice (matsarya), tie the sadhaka to their imprints; he finds it exceedingly difficult to come out of the turmoil and to differentiate between the mind and the soul. Practice of yoga and renunciation of sensual desires take one towards spiritual attainment.

Practice demands four qualities from the aspirant: dedication, zeal, uninterrupted awareness and long duration. Renunciation also demands four qualities: disengaging the senses from action, avoiding desire, stilling the mind and freeing oneself from cravings.

Practitioners are also of four levels, mild, medium, keen and intense. They are categorized into four stages: beginners; those who understand the inner functions of the body; those who can connect the intelligence to all parts of the body; and those whose body, mind and soul have become one. (See table 1 (#ulink_fc7a7316-8446-52a9-a3d4-2eb300e9dd4e).)

Effects of practice and renunciation

Intensity of practice and renunciation transforms the uncultured, scattered consciousness, citta, into a cultured consciousness, able to focus on the four states of awareness. The seeker develops philosophical curiosity, begins to analyse with sensitivity, and learns to grasp the ideas and purposes of material objects in the right perspective (vitarka). Then he meditates on them to know and understand fully the subtle aspects of matter (vicara). Thereafter he moves on to experience spiritual elation or the pure bliss (ananda) of meditation, and finally sights the Self. These four types of awareness are collectively termed samprajñata samadhi or samprajñata samapatti. Samapatti is thought transformation or contemplation, the act of coming face to face with oneself.

From these four states of awareness, the seeker moves to a new state, an alert but passive state of quietness known as manolaya. Patañjali cautions the sadhaka not to be caught in this state, which is a crossroads on the spiritual path, but to intensify his sadhana to experience a still higher state known as nirbija samadhi or dharma megha samadhi. The sadhaka may not know which road to follow beyond manolaya, and could be stuck there forever, in a spiritual desert. In this quiet state of void, the hidden tendencies remain inactive but latent. They surface and become active the moment the alert passive state disappears. This state should therefore not be mistaken for the highest goal in yoga.

This resting state is a great achievement in the path of evolution, but it remains a state of suspension in the spiritual field. One loses body consciousness and is undisturbed by nature, which signifies conquest of matter. If the seeker is prudent, he realizes that this is not the aim and end, but only the beginning of success in yoga. Accordingly, he further intensifies his effort (upaya pratyaya) with faith and vigour, and uses his previous experience as a guide to proceed from the state of void or loneliness, towards the non-valid state of aloneness or fullness, where freedom is absolute.

Table 1: Levels of sadhaka, levels of sadhana and stages of evolution

If the sadhaka’s intensity of practice is great, the goal is closer. If he slackens his efforts, the goal recedes in proportion to his lack of willpower and intensity.

Universal Soul or God (Isvara, Purusa Visesan or Paramatman)

There are many ways to begin the practice of yoga. First and foremost, Patañjali outlines the method of surrender of oneself to God (Isvara). This involves detachment from the world and attachment to God, and is possible only for those few who are born as adepts. Patañjali defines God as the Supreme Being, totally free from afflictions and the fruits of action. In Him abides the matchless seed of all knowledge. He is First and Foremost amongst all masters and teachers, unconditioned by time, place and circumstances.

His symbol is the syllable AUM. This sound is divine: it stands in praise of divine fulfilment. AUM is the universal sound (sabda brahman). Philosophically, it is regarded as the seed of all words. No word can be uttered without the symbolic sound of these three letters, a, u and m. The sound begins with the letter a, causing the mouth to open. So the beginning is a. To speak, it is necessary to roll the tongue and move the lips. This is symbolized by the letter u. The ending of the sound is the closing of the lips, symbolized by the letter m..AUM represents communion with God, the Soul and with the Universe.

AUM is known as pranava, or exalted praise of God. God is worshipped by repeating or chanting AUM, because sound vibration is the subtlest and highest expression of nature. Mahat belongs to this level. Even our innermost unspoken thoughts create waves of sound vibration, so AUM represents the elemental movement of sound, which is the foremost form of energy. AUM is therefore held to be the primordial way of worshipping God. At this exalted level of phenomenal evolution, fragmentation has not yet taken place. AUM offers complete praise, neither partial nor divided: none can be higher. Such prayer begets purity of mind in the sadhaka, and helps him to reach the goal of yoga. AUM, repeated with feeling and awareness of its meaning, overcomes obstacles to Self-Realization.

The obstacles

The obstacles to healthy life and Self-Realization are disease, indolence of body or mind, doubt or scepticism, carelessness, laziness, failing to avoid desires and their gratification, delusion and missing the point, not being able to concentrate on what is undertaken and to gain ground, and inability to maintain concentration and steadiness in practice once attained. They are further aggravated through sorrows, anxiety or frustration, unsteadiness of the body, and laboured or irregular breathing.

Ways of surmounting the obstacles and reaching the goal

The remedies which minimize or eradicate these obstacles are: adherence to single-minded effort in sadhana, friendliness and goodwill towards all creation, compassion, joy, indifference and non-attachment to both pleasure and pain, virtue and vice. These diffuse the mind evenly within and without and make it serene.

Patañjali also suggests the following methods to be adopted by various types of practitioners to diminish the fluctuations of the mind.

Retaining the breath after each exhalation (the study of inhalation teaches how the self gradually becomes attached to the body; the study of exhalation teaches non-attachment as the self recedes from the contact of the body; retention after exhalation educates one towards detachment); involving oneself in an interesting topic or object contemplating a luminous, effulgent and sorrowless light; treading the path followed by noble personalities; studying the nature of wakefulness, dream and sleep states, and maintaining a single state of awareness in all three; meditating on an object which is all-absorbing and conducive to a serene state of mind.

Effects of practice

Any of these methods can be practised on its own. If all are practised together, the mind will diffuse evenly throughout the body, its abode, like the wind which moves and spreads in space. When they are judiciously, meticulously and religiously practised, passions are controlled and single-mindedness develops. The sadhaka becomes highly sensitive, as flawless and transparent as crystal. He realizes that the seer, the seeker and the instrument used to see or seek are nothing but himself, and he resolves all divisions within himself.

This clarity brings about harmony between his words and their meanings, and a new light of wisdom dawns. His memory of experiences steadies his mind, and this leads both memory and mind to dissolve in the cosmic intelligence.

This is one type of samadhi, known as sabija samadhi, with seed, or support. From this state, the sadhaka intensifies his sadhana to gain unalloyed wisdom, bliss and poise. This unalloyed wisdom is independent of anything heard, read or learned. The sadhaka does not allow himself to be halted in his progress, but seeks to experience a further state of being: the amanaskatva state.

If manolaya is a passive, almost negative, quiet state, amanaskatva is a positive, active state directly concerned with the inner being, without the influence of the mind. In this state, the sadhaka is perfectly detached from external things. Complete renunciation has taken place, and he lives in harmony with his inner being, allowing the seer to shine brilliantly in his own pristine glory.

This is true samadhi: seedless or nirbija samadhi.

II: Sadhana Pada (#ulink_8e9b5ac1-0cb0-5150-9f44-20c886f60268)

Why did Patañjali begin the Yoga Sutras with a discussion of so advanced a subject as the subtle aspect of consciousness? We may surmise that intellectual standards and spiritual knowledge were then of a higher and more refined level than they are now, and that the inner quest was more accessible to his contemporaries than it is to us.

Today, the inner quest and the spiritual heights are difficult to attain through following Patañjali’s earlier expositions. We turn, therefore, to this chapter, in which he introduces kriyayoga, the yoga of action. Kriyayoga gives us the practical disciplines needed to scale the spiritual heights.

My own feeling is that the four padas of the Yoga Sutras describe different disciplines of practice, the qualities or aspects of which vary according to the development of intelligence and refinement of consciousness of each Sadhaka.

Sadhana is a discipline undertaken in the pursuit of a goal. Abhyasa is repeated practice performed with observation and reflection. Kriya, or action, also implies perfect execution with study and investigation. Therefore, sadhana, abhyasa, and kriya all mean one and the same thing. A sadhaka, or practitioner, is one who skilfully applies his mind and intelligence in practice towards a spiritual goal.

Whether out of compassion for the more intellectually backward people of his time, or else foreseeing the spiritual limitations of our time, Patañjali offers in this chapter a method of practice which begins with the organs of action and the senses of perception. Here, he gives those of average intellect the practical means to strive for knowledge, and to gather hope and confidence to begin yoga: the quest for Self-Realization. This chapter involves the sadhaka in the art of refining the body and senses, the visible layers of the soul, working inwards from the gross towards the subtle level.

Although Patañjali is held to have been a self-incarnated, immortal being, he must have voluntarily descended to the human level, submitted himself to the joys and sufferings, attachments and aversions, emotional imbalances and intellectual weaknesses of average individuals, and studied human nature from its nadir to its zenith. He guides us from our shortcomings towards emancipation through the devoted practice of yoga. This chapter, which may be happily followed for spiritual benefit by anyone, is his gift to humanity.

Kriyayoga, the yoga of action, has three tiers: tapas, svadhyaya and Isvara pranidhana. Tapas means burning desire to practise yoga and intense effort applied to practice. Svadhyaya has two aspects: the study of scriptures to gain sacred wisdom and knowledge of moral and spiritual values; and the study of one’s own self, from the body to the inner self. Isvara pranidhana is faith in God and surrender to God. This act of surrender teaches humility. When these three aspects of kriyayoga are followed with zeal and earnestness, life’s sufferings are overcome, and samadhi is experienced.

Sufferings or afflictions (Klesas)

Klesas (sufferings or afflictions) have five causes: ignorance, or lack of wisdom and understanding (avidya), pride or egoism (asmita), attachment (raga), aversion (dvesa), and fear of death and clinging to life (abhinivessa). The first two are intellectual defects, the next two emotional, and the last instinctual. They may be hidden, latent, attenuated or highly active.

Avidya, ignorance, or lack of wisdom, is a fertile ground in which afflications can grow, making one’s life a hell. Mistaking the transient for the eternal, the impure for the pure, pain for pleasure, and the pleasures of the world for the bliss of the spirit constitutes avidya.

Identifying the individual ego (the ‘I’) with the real soul is asmita. It is the false identification of the ego with the seer.

Encouraging and gratifying desires is raga. When desires are not gratified, frustration and sorrow give rise to alienation or hate. This is dvesa, aversion.

The desire to live forever and to preserve one’s individual self is abhinivesa. Freedom from such attachment to life is very difficult for even a wise, erudite and scholarly person to achieve. If avidya is the mother of afflictions, abhinivesa is its offspring.

All our past actions exert their influence and mould our present and future lives: as you sow, so shall you reap. This is the law of karma, the universal law of cause and effect. If our actions are good and virtuous, afflictions will be minimized; wrong actions will bring sorrow and pain. Actions may bear fruit immediately, later in life or in lives to come. They determine one’s birth, span of life and the types of experiences to be undergone. When spiritual wisdom dawns, one perceives the tinge of sorrow attached even to pleasure, and from then on shuns both pleasure and pain. However, the fruits of actions continue to entrap ordinary beings.

How to minimize afflictions

Patañjali counsels dispassion towards pleasures and pains and recommends the practice of meditation to attain freedom and beatitude. First he describes in detail the eightfold path of yoga. Following this path helps one to avoid the dormant, hidden sufferings which may surface when physical health, energy and mental poise are disturbed. This suggests that the eightfold path of yoga is suitable for the unhealthy as well as for the healthy, enabling all to develop the power to combat physical and mental diseases.

Cause of afflictions

The prime cause of afflictions is avidya: the failure to understand the conjunction between the seer and the seen: purusa and prakrti. The external world lures the seer towards its pleasures, creating desire. The inevitable non-fulfilment of desires in turn creates pain, which suffocates the inner being. Nature and her beauties are there for enjoyment and pleasure (bhoga) and also for freedom and emancipation (yoga). If we use them indiscriminately, we are bound by the chains of pleasure and pain. A judicious use of them leads to the bliss which is free from pleasure mixed with pain. The twin paths to this goal are practice (abhyasa), the path of evolution, of going forward; and detachment or renunciation (vairagya), the path of involution, abstaining from the fruits of action and from worldly concerns and engagements.

Cosmology of nature

In samkhya philosophy, the process of evolution and the interaction of spirit and matter, essence and form, are carefully explained.

To follow nature’s evolution from its subtlest concept to its grossest or most dense manifestation, we must start with root nature, mula-prakrti. At this phase of its development, nature is infinite, attributeless and undifferentiated. We may call this phase ‘noumenal’ or alinga (without mark): it can be apprehended only by intuition. It is postulated that the qualities of nature, or gunas, exist in mula-prakrti in perfect equilibrium; one third sattva, one third rajas and one third tamas.

Root nature evolves into the phenomenal stage, called linga (with mark). At this point a disturbance or redistribution takes place in the gunas, giving nature its turbulent characteristic, which is to say that one quality will always predominate over the other two (though never to their entire exclusion; for example, the proportion might be 7/10 tamas, 2/10 rajas, 1/10 sattva, or any other disproportionate rate). The first and most subtle stage of the phenomenal universe is mahat, cosmic intelligence. Mahat is the ‘great principle’, embodying a spontaneous motivating force in nature, without subject or object, acting in both creation and dissolution.

Nature further evolves into the stage called avisesa (universal or non-specific) which can be understood by the intellect but not directly perceived by the senses. To this phase belong the subtle characteristics of the five elements, which may be equated with the infra-atomic structure of elements. These may be explained at a basic level as the inherent quality of smell in earth (prthvi), of taste in water (ap), of sight or shape in fire (tej), of touch in air (vayu) and of sound in ether (akasa). The ‘I’ principle is also in this group.

The final stage, visesa, in which nature is specific and obviously manifest, includes the five elements, the five senses of perception (ears, eyes, nose, tongue and skin), the five organs of action (arms, legs, mouth, generative and excretory organs), and lastly the mind, or the eleventh sense. So in all, there are twenty-four principles (tattvas) of nature, and a twenty-fifth: purusa, atman, or soul. Purus permeates and transcends nature, without belonging to it.

(When purusa stirs the other principles into activity, it is the path of evolution. Its withdrawal from nature is the path of involution. If purusa interacts virtuously with the properties of nature, bliss is experienced; for such a purusa, prakrti becomes a heaven. If wrongly experienced, it becomes a hell.

Sometimes, purusa may remain indifferent, yet we know that nature stirs on its own through the mutation of the gunas, but takes a long time to surface. If purusa, gives a helping hand, nature is disciplined to move in the right way, whether on the path of evolution or involution.)

The sixteen principles of the visesa stage, are the five elements, the five senses of perception and five organs of action, and the mind. They are definable and distinguishable. At the avisesa stage, all five tanmatras – smell, taste, sight or shape, touch and sound – and ahamkara, ego, are undistinguishable and indefinable, yet nevertheless entities in themselves. At the material level of creation, tamas is greater than rajas and sattva, whereas at the psycho-sensory level, rajas and sattva together predominate.

The interaction of the gunas with these sixteen principles shapes our destiny according to our actions. Effectively, our experiences in life derive from the gross manifestations of nature, whether painful or pleasurable; that is, whether manifesting as physical affliction or as art. The delusion that this is the only ‘real’ level can lead to bondage, but fortunately the evolutionary or unfolding structure of nature has provided the possibility of involution, which is the return journey to the source. This is achieved by re-absorbing the specific principles into the non-specific, then back into the alinga state, and finally by withdrawing and merging all phenomenal nature back into its noumenal root, the unmanifested mula-prakrti, rather as one might fold up a telescope.

At the moment when the seer confronts his own self, the principles of nature have been drawn up into their own primordial root and remain quietly there without ruffling the serenity of the purusa. It is sufficient to say here that the involutionary process is achieved by the intervention of discriminating intelligence, and by taming and re-balancing the gunas to their noumenal perfect proportions, so that each stage of re-absorption can take place. Yoga shows us how to do this, starting from the most basic manifest level, our own body.

Once the principles have been withdrawn into their root, their potential remains dormant, which is why a person in the state of samadhi is but can not do; the outward form of nature has folded up like a bird’s wings. If the sadhaka does not pursue his sadhana with sufficient zeal, but rests on his laurels, the principles of nature will be re-activated to ill effect. Nature’s turbulence will again obscure the light of the purusa as the sadhaka is again caught up in the wheel of joy and sorrow. But he who has reached the divine union of purusa and prakrti, and then redoubles his efforts, has only kaivalya before him.

Characteristics of Purusa