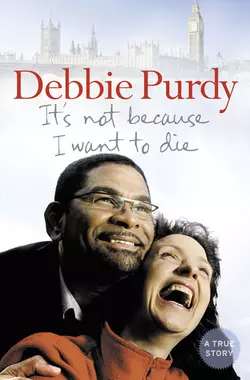

It’s Not Because I Want to Die

Debbie Purdy

Debbie Purdy doesn't want to die. She has far too much to live for. But when the time comes, and the pain is so unbearable that she cannot go on, she wants her husband to be by her side, holding her hand until the end; and she wants to know that he won't be arrested.Debbie Purdy – the face of Britain's right-to-die campaign – suffers from multiple sclerosis. She was diagnosed in 1995 – barely a month after she met her now-husband, Omar Puente, in a bar in Singapore. Within weeks she flew back out to meet Omar and, despite her devastating diagnosis, their relationship grew, as together they travelled Asia doing all the things they loved. When Debbie's health left her no choice but to go back to the UK, Omar followed. They married in 1998.But since the death in 2002 of motor neurone disease sufferer Diane Pretty, who lost her legal battle to have her husband help her take her own life, there has been dark cloud on the horizon for Debbie. She is in pain all the time, with poor circulation, headaches, bed sores and muscle cramps. Once or twice a week, she falls in the shower, presses her panic button and waits for complete strangers to come and help. People pity Debbie, saying she must feel undignified. She disagrees. The only thing she thinks is undignified is having no control over her life or death.When the pain becomes unbearable Debbie wants to be able to choose to end her life, surrounded by her loved ones. In England and Wales this is considered assisting suicide – a crime punishable by up to 14 years imprisonment. Debbie fears as a black foreigner Omar is more likely to face prosecution. All she wants is for the law to be clarified. Then she can make sure Omar never crosses the line.At the end of July 2009 Debbie's long fight was finally rewarded with a court ruling that the current lack of clarity is a violation of the right to a private and family life, and the Director of Public Prosecutions being ordered to issue clear guidance on when prosecutions can be brought in assisted suicide cases, bringing hope and reassurance thousands nationwide.Now, with passion and honesty, Debbie shares her unique story. Told with the joie-de-vivre and grace for which she has become known, Debbie describes her life and her battle.

It’s Not Because I want to Die

Debbie Purdy

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#uaf0c4079-4d8a-50eb-8256-9c8269243b0d)

Title Page (#ud7ed494a-7e4e-5ca8-b387-0c122c301a4d)

Preface (#ub3624381-4e42-5737-b2fb-122eb2fec211)

Chapter 1 A Heart in Chains (#uccf9b53d-746e-5277-bede-98528b3bf370)

Chapter 2 Wading through Honey (#ue2ca5f33-9446-5bd2-af0a-dee188d48560)

Chapter 3 ‘Can I Scuba-Dive?’ (#ua19fc413-ff5e-546e-b5ce-20e13544165e)

Chapter 4 My Beautiful Career (#ufb36297c-fe23-5c3a-b104-f6e0a71a2205)

Chapter 5 The Boys from Cuba (#uf5ba360b-4e4b-5883-a968-eaaaec72d84c)

Chapter 6 ‘My Missus’ (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7 ‘Your Grass Is White’ (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 In Sickness and in Health (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 The Baby Question (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 The View from 4 Feet (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 The Big Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 Let’s Talk about Death (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 The Speeding Train (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 Cuban Roots (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 A Negotiated Settlement (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 A Short Stay in Switzerland (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 Entering the Fray (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 My High-Tech House (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 Some Real-Life, Grown-Up Decisions (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 My Day(s) in Court (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 Round Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 The Tide Turns (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 My Own Little Bit of History (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 Listening to All Sides (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 Lucky Me (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Preface (#ulink_71b042f4-51a3-5eeb-89fe-c055aba7d131)

‘Jump!’ the instructor yelled.

I obeyed instinctively, then immediately regretted it. What the hell was I doing jumping out of a perfectly good aeroplane 3,000 feet in the air?

‘One thousand and one.’ Training kicked in and I adopted the spread-eagle position, face down. Why am I doing this? What was I thinking?

‘One thousand and two,’ I counted aloud, as we’d been taught, then squinted upwards. Was there any way back into the plane? Surely there had to be. I was still attached by a static line that would pull my chute open. Could I climb up it?

‘One thousand and three.’ The Doc Martens I was wearing were too wide and my feet were shaking, hitting each side so rapidly I thought they might come loose and fall off. I can’t believe I’m doing this, I thought. This is so stupid.

Terror was making me alert to every tiny sensation and I could feel the blood pumping hard through my veins.

‘One thousand and four. Check, shit, malfunction. If your parachute hasn’t deployed by the time you’ve finished counting, you’re in trouble and it’s time to open your secondary chute. Just then, though, I felt a gentle lift and I was pulled upright as my main chute opened. The static line detached and I felt intense relief as I looked up at the billowing white canopy. I’ve never felt so grateful to see anything!

The relief was short-lived because I then looked down and saw that there was nothing between me and the ground. I was falling more slowly, but I was still very definitely falling.

It was deathly quiet up there, and very peaceful. I’d been told to scope out a big yellow cross on the ground and aim for that using the toggles on either side of my chute to change direction, but I couldn’t even see the damn cross. Where the hell was it? I spotted a parachute in front of me and thought I would just aim for that in the hope that it was aiming for the cross. All the guys who were jumping with me that day had seemed cool, calm and confident, so I figured that whoever I was following was going the right way.

I played with the toggles but wasn’t sure how much effect I was having. I kept aiming for the guy ahead and praying that he wasn’t headed for a tree. I still couldn’t see the cross, but by that stage I didn’t care if I was miles away so long as I hit the ground with both feet and didn’t end up hanging from an electricity cable or the upper branches of a tree.

Suddenly the ground was right there and I closed my eyes and went into autopilot, rolling on impact as we’d been taught. When I opened my eyes, I looked down my body to make sure nothing was broken or bleeding and realised my arm was lying on a yellow cross. I’d landed right on top of the target. The guy I had been following was a few hundred yards further on. There was no blood. I was alive and intact.

The instructor who filled out my logbook later wrote, ‘GATW,’ meaning ‘Good all the way.’ I didn’t mention that it was a matter of luck rather than careful control. I felt fantastic. Sheer terror turned to sheer exhilaration and I asked, ‘When can I have another go?’

That was in 1981 and I was 17 years old.

In 1995, fourteen years later, a doctor said to me, ‘When I first saw you, I thought you had MS,’ and inside my head I started to count, one thousand and one.

He organised an MRI scan and a lumbar puncture. One thousand and two.

It was MS and I was in freefall, scared and lonely. One thousand and three.

I walked into the arrivals hall at Singapore’s Changi Airport and saw Omar waiting. I felt a gentle lift and I was upright again – still falling, but I knew I was safe and would be able to control my descent.

I haven’t hit the ground yet. What follows is the story of my journey down so far.

Chapter 1 A Heart in Chains (#ulink_5078ed64-1ba9-5881-8ced-87ab6ac8d244)

In January 1995, at the age of 31, I had recently moved to Singapore and was earning my keep with a pen. (Well, a Mac laptop, but that’s product placement!) I wrote brochure copy for an adventure travel company, and music reviews and features for a number of magazines. A welcome perk of my job was that I got into all the live music clubs free, so of course I was having fun (especially as the bars wouldn’t take money from me for drinks). I shared a flat with an Australian bass player, Belinda, and a Japanese teacher, Tetsu, and was dating my fair share of men without having anyone serious on the scene.

One night Belinda came home from work raving about a band she had seen playing in a club called Fabrice’s. ‘There are seven gorgeous men,’ she said, ‘and they’re explosive on stage. You have to see them.’

‘What are they called?’

‘The Cuban Boys.’

I rang Music Monthly to ask if they’d be interested in a review and they said, ‘Sure.’

I was interested in exploring why foreign musicians were frequently paid so little. I had dreams of doing some investigative journalism to rival All the President’s Men. It was a genuine problem, but I have to admit I was looking for a problem I could bury myself in solving.

I turned up at Fabrice’s on the afternoon of 25 January, toting my notebook and camera, to sit in on the band’s rehearsals. My first thought was that ‘the Cuban Boys’ was a strange name for a group that had seven blokes and three girls in it. My second thought was that Belinda had been exaggerating. Only two of the band members, Emilio and Juan Carlos, were particularly good-looking, while the rest could be described as having ‘good personalities’.

It was the band leader, Omar Puente, who came over to talk to me for the interview, and I thought he seemed a bit Mafioso with his little moustache. He sat opposite me looking very serious and frowning in concentration as we struggled to overcome the language barrier. I spoke English, some Norwegian and a little French, while Omar spoke Spanish, Russian and a little French, so French it was. It took me about twenty minutes to get a single quotable sentence. (I wasn’t 100 per cent sure of how much I understood, but he didn’t read English, so I was unlikely to be sued.)

I picked up the camera and motioned that I wanted to take a picture of them playing. Omar indicated in sign language that they should get changed into their performance outfits, instead of the casual clothes they were wearing.

‘No, don’t bother,’ I said. ‘If you could just play a number for me as you are, that would be fine.’ I motioned towards the stage.

When they started playing, I was instantly impressed. They had a really good sound, and Omar’s violin-playing was fantastic. The repertoire comprised modern and traditional Cuban dance music, but Omar also did a little Bach as a solo and I could hear humour as well as hard work and technique in his playing. On the violin he obviously felt in control; he was a complete master of it.

In the middle of the set, the band launched into a version of ‘La Cucaracha’. The percussionist, Juan Carlos, stood on his chair and put one leg on his conga drum. Then they all stopped playing and did pelvic thrusts in time to the ‘Da-da-da-da dah-dah’ bit in the chorus. It was crude and obscene, but mesmerising.

I came back to Fabrice’s later that night to watch the proper show. The band was not dressed up in their performance shirts, so I figured Omar had been trying to be interesting for the press. (Now I realise it was me he was trying to impress.) He had a very charismatic presence, interacting with the audience and chatting to them between numbers, and moving around the stage with ease. He wasn’t the best-looking band member, but you couldn’t take your eyes off him, mainly because you wanted to see what he would do next. All the band members moved with an easy, natural rhythm, the music was note-perfect, and their set was a huge hit with the regulars at Fabrice’s.

After they finished playing, Omar walked off stage and came over to sit beside me, bringing his friend Rolando, who spoke a bit of English and tried to translate for us.

‘Will you be nice about us in your magazine?’ Omar and Rolando asked. Well, that’s what they were trying to ask.

‘Of course,’ I said. They were so earnest and incredibly entertaining to watch that being anything less than glowing about them would have been like kicking a puppy.

The two of them would feverishly converse in Spanish, words tripping over one another, for several minutes before Omar would try to say something in English.

‘Do you live in Singapore?’ he asked next, and I told him that I did.

Our scintillating conversation floundered a bit when one of Rolando’s girlfriends arrived, but Omar didn’t leave my side for the rest of the evening except to get back on stage and play the second set.

At two or three in the morning, when Singapore was winding down, I was in the habit of stopping at a market for an early breakfast on the way home. I invited Omar to join me so we could continue trying to talk. We borrowed an English–Spanish dictionary, as Rolando didn’t consider his role much fun and the girlfriend clearly was. We walked down to the market and bought bowls of congee (a kind of rice porridge) and some other snacks, and sat at a roadside table to eat.

Now we were away from his job and the band, Omar dropped his earlier, more fatherly persona and started to be flirtatious, touching my arm and offering me bites of his food to sample. It dawned on me that he thought I had asked him on a date. I was just being professional and finishing the interview (I think). He was all smiles and charm until he accidentally bit on a piece of chilli, which ruined his composure. His eyes started watering and he was coughing and spluttering. I handed him a bottle of water to cool his mouth down. Not the most romantic start, and nothing to indicate that this would be the love of my life.

I still hadn’t asked about how much the band was being paid, so I opened the dictionary at the word ‘fee’. Omar signalled, ‘Twenty,’ with his fingers.

‘A day?’ I was horrified.

He nodded.

I thought we were talking about Singapore dollars, which

are worth a lot less than US dollars. Believing that the band was being paid a tiny fraction of what their Singaporean counterparts would earn, my trade-unionist instincts kicked in and my hackles rose. After some frantic investigation, though, I realised that he was telling me how much their daily allowance was, rather than their total fee, and he was talking in US dollars.

I later learned that their income had also been affected by a bad business decision. Most musicians pay an agent fee to whoever got them the job. For this type of long-term contract, it’s usually no more than 15 per cent, and if two or more agents are involved they share the fee. Omar had been a band leader for a short time and his business skills were only marginally better than his language ones. Consequently, his limited (to put it politely) English meant that the Cuban Boys were paying two agents 15 per cent each, which resulted in the ten Cubans receiving just 70 per cent of the fee. It didn’t seem right, but no one person was to blame. The band saved most of their pay to buy instruments, as they would need better equipment to be the next ‘super group’. I could see they would also need better business sense.

We had been speaking at cross-purposes and not even in the same language. It’s hard to make sense when you have to flick through a whole dictionary to locate every word, and even when you find the right one, cultural references mean you still speak at cross-purposes.

After I’d finished eating, I stood up to leave, laying my hands against my cheek to indicate that I needed to sleep. Dawn was breaking and people with normal jobs were starting to make their way to work. Omar asked, ‘Fabrice’s?’ and I realised he was inviting me to come to the gig that evening. I couldn’t make it, so I shook my head and said, ‘Au revoir. A bientôt.’ The Singapore music scene was tiny and I had no doubt we would bump into each other again before too long.

Years later we would still disagree on the details of the day we met. I remember wearing a little black dress, looking sexy and sophisticated, whereas he said I was wearing a white T-shirt and a black skirt. (I know he’s wrong because he says I wasn’t wearing a bra!) I probably had the skirt and T-shirt on in the afternoon for the interview (but with a bra) and the dress on in the evening when I returned to the club for the set. He says it was me who came on to him, whereas I know it was definitely him. He says he was initially attracted by my bottom, and even said so in an Observer article in 1998. (Talking about the size of a girl’s bottom in print must be grounds for divorce!) I wasn’t really that interested in him at first, but I loved the way he played violin. We had the same experience, but we both have different memories of it. Mine, of course, are right!

A couple of days after meeting Omar, Belinda and I went to a jam session at Harry’s Bar – all the musicians in Singapore ended up there on Sundays because if you played you got free drinks – and as soon as we walked in I spotted Omar. He came straight over, but there was an awkward silence because there wasn’t much we could say without someone to translate for us. Normally, you would move on and talk to someone else at this point, but Omar sat down. We listened to the music and had a few drinks. Every time a male friend of mine came over to chat, Omar positioned himself between me and the other man like a bodyguard and watched intently. I wasn’t sure that I wanted this sort of attention, but I felt flattered to be pursued by someone so ‘present’. Gradually I realised that he seemed to have decided I was his.

Back at the flat I shared with Tetsu and Belinda, Belinda quizzed me about him. ‘He looks pretty interested. How about you?’

‘A moot point – we can’t even discuss the weather. He seems nice, but he could be an axe murderer for all I know.’

Belinda couldn’t communicate with him either, and his easy charm and macho display at Harry’s rang warning bells. Besides, her own experience of Latin musicians hardly endeared Omar to her. She herself knew charming Latin men who would quickly make beautiful declarations of love, mean it when they said it, but then leave the room and fall in love with someone else, before finally going home to a wife and kids.

Omar was only a year and a bit older than me – 33 when we met – but he took responsibility for the whole band, and being a band leader is probably the closest thing to being a parent you can get without having to change nappies. Omar could never relax properly at Fabrice’s, where he had nine Cuban kids to look out for. The language barrier was the main problem for them all, but there was always something ready to trip them up. They had a safe refuge on stage. When the band members were together, they could be themselves – crazy and funny, a little wild but always in control – and they had their fearless leader, who was, like any parent, ready to do anything to protect them. Omar loved his band, his music and his life. There was no language barrier with a violin in Omar’s hands.

He may have been the responsible one, the father figure of the Cuban Boys, but it didn’t stop him messing around on stage. One night not long after I’d met Omar, he introduced the band – ‘Juan Carlos on conga, Julio on drum kit…’ – and then he pointed to me in the audience, making everyone turn to look, and said, ‘Allì tienes a la mujer que tiene mi corazón encadenado.’

‘What did he just say?’ I pestered a friend, who was laughing by my side.

He translated: ‘There’s the woman who has my heart in chains.’

I went crimson (something I was to do a lot with Omar). I liked the fact that he was so public about trying to win me over. It was flattering…but still I had my reservations. Latin men and all that.

It’s difficult forming an impression of someone at the best of times, even more so when you don’t speak the same language and you can’t have a conversation, but while watching Omar perform I felt I was getting to know the man. Of all instruments, I think the violin is closest to a voice and I believe you can get a sense of who a person is by the way that they play. Omar’s character came across in his music, and what I saw was someone who was witty and intelligent and caring. It would have taken me years to work that out based on our staccato verbal communications, but his violin-playing told me who he was.

For two and a half weeks I saw Omar nearly every night at Fabrice’s or, earlier in the evening, at one of Singapore’s other music venues (of which there were many). As soon as I arrived, he would stride across the room to kiss me hello and stand by my side, warning off competitors. He’d play his set on stage, then walk straight over the raised area that adjoined the stage to come back and stand by me. He seemed devoted, but still all my friends were saying, ‘Latin musicians? You don’t want to go near one.’

On Valentine’s Day I went for dinner with another man, an engineer who was a friend of the manager of Fabrice’s. We’d known each other for a couple of months and he was very attractive, so when he’d asked me out I’d thought, Great.

He was charming and attentive, and we had a lively conversation over our meal. Then, at midnight, we drifted along to Fabrice’s, because that’s where everyone went in the early hours. As soon as we walked in, though, I spotted Omar and felt uncomfortable. I didn’t want him to see me with another man. He got up on stage to play his set and I led my date over to join a group of friends, making sure I sat at the opposite side of the table from him.

My date was puzzled by my hot–cold attitude and asked, ‘Do you want to dance, Debbie?’

‘No, not really. I’m fine, thanks.’ I realised I didn’t want Omar to see me on a date. I had been proclaiming disinterest

for a couple of weeks, but my reluctance to let him see me with another man spoke volumes and I had to admit, to myself at least, that this charming enigma was burrowing his way under my skin.

My date came over to sit beside me and slipped his arm around my shoulders. Immediately I jumped up. ‘Must go and chat to someone,’ I gabbled. ‘I’ll be back in a minute.’

The poor man didn’t know what was going on. Every time he tried to lay a finger on me, I’d quickly check whether we were in Omar’s line of sight from the stage, and if we were I’d jump up manically and find someone else to talk to. I made sure we weren’t alone, inviting everyone I knew to join us at our table. By the end of the evening my poor date had certainly got the message that I wasn’t interested in him romantically – either that or he had concluded that I was deeply neurotic.

I didn’t talk to Omar that night because he was working and we’d left by the time he came off stage, but several times I saw him watching me with a confused expression. For my part, that was the night I finally accepted that I was hugely attracted to him. Latin musician or not, I was going to have to go out with this man. It didn’t look as though I had a choice.

The next day when I got home from work at the adventure travel company, Belinda said to me, ‘You’ll never guess what! He called. Several times.’

‘Omar? He called here? What did he say?’ Belinda didn’t speak any Spanish either, so I knew it couldn’t have been a long chat.

‘He said, “Party. Tonight,” and he left the address. That was all.’

A mutual friend of ours was having a party that evening and Omar had phoned to make sure I would be there. I think I blushed I was so pleased. ‘What do you reckon?’

‘Oh, Debbie, for goodness’ sake, just go for it and save us all the hassle. Please.’

I grinned. That’s exactly what I planned to do.

The party was at the home of an American guy and he’d set up a barbecue on his balcony. It was late when I got there and the main room was heaving with people. I stood in the entrance, peering around to see who I knew, and locked eyes with someone staring straight back at me: Omar. He hurried over.

‘You came,’ he said in English. ‘That’s good.’

He got me a drink and Rolando came over to translate for a while so we could have a slightly more sophisticated conversation than our usual monosyllables. When Omar went to the barbecue to get some food, I took the opportunity to ask Rolando a question that had been on my mind: was Omar married? I pointed at Rolando’s wedding finger and motioned a ring. He shook his head, but I wanted to double-check, given my distrust of Latinos, musicians and men in general, so I asked Rolando directly.

He frowned and scratched his cheek before saying, ‘I’m not sure. He’s never mentioned anything about a wife. We just play together. We aren’t close. Sorry – I can’t help you there.’

I later found out that Omar and Rolando had been best friends for fifteen years and knew all there was to know about each other. Rolando hadn’t wanted to answer my question in case he contradicted something that Omar had told me, so he’d just avoided it. It was the same for all the band members: they would have laid down their lives for each other. They were a long way from home, and they depended on each other, so economy with the truth over romantic interludes was second nature. It was behaviour like this that gave Latin musicians their reputation (but they also have a reputation for steadfast loyalty, and that’s true as well).

I circulated, chatting to people I knew, while Omar hovered by my side doing his bodyguard impression. As the party broke up, we went back to Harry’s Bar and I knew that I was happy with Omar beside me. Everyone was watching us and wondering, Will they? Won’t they? because his pursuit of me was good gossip in our orbit.

In the early hours of the morning he walked me home to my flat and I was amused because he did that gentlemanly thing of constantly moving so that he was between me and the road. I tried to explain to him that the tradition derived from days when ladies didn’t want their beautiful gowns to get splashed by passing carriages, which was hardly likely to be a problem in modern-day Singapore. First of all, I had left my beautiful gown at home, and secondly, the roads were bonedry. I’m not sure he understood my explanation, delivered in a mixture of French, English and sign language, like an elaborate game of charades.

Shortly after that he kissed me for the first time, which was nice. More than nice. He remained a perfect gentleman, though, dropping me back at the flat I shared with Belinda and Tetsu, and asking if he could see me the next evening. He gave me his phone number and taught me how to greet the person who answered the phone: ‘Quiero hablar con mi mulato lindo.’ I repeated the phrase until I could say it to his satisfaction, and we kissed one last time before he headed off down the road, turning to give me a wave as he left my sight.

He and the band members loved it when I phoned the next day – I thought I was greeting them and commenting on the wonderful day; in fact I was asking to speak to ‘my beautiful mulatto’!

Nevertheless, the next night I was right there when Omar played his set at Fabrice’s and he gazed straight at me as he sang many of the numbers. When he was introducing the band, he went through all their names, then at the end said, ‘Allì tienes a la mujer que tiene mi corazón encadenado,’ and I knew without being told what that meant. I had his heart in chains. From then on he said it every night I was there.

The evening after we’d slept together for the first time, he walked off stage in the middle of the Cuban Boys’ set and came over to kiss me, which was incredibly romantic. Our friends in the audience cheered and clapped. I blushed, because I embarrass easily, but I loved it at the same time.

Neither of us had much money, but it didn’t matter – we were living in a beautiful city, had some great friends, and both of us had jobs that we loved and would have paid for the privilege of doing. We had the added advantage of being welcome guests at most of the places we wanted to go. (It seems silly, but business is business and I was more welcome than Omar because I could publicise the venue.) We would talk in odd words and phrases we’d picked up of each other’s language, supplemented by whole sentences when Rolando or someone else was around to translate for us. After the Cuban Boys’ set at Fabrice’s, we would go for breakfast at the market or pick up some food from the 7-Eleven in Orchard Road, then walk home together in the early morning light. It was lovely, despite the fact that I sometimes had to go straight to work without any sleep.

I had a book of Chinese horoscopes in my room and Omar asked me when my birthday was, then worked out that I was born in the Year of the Rabbit, so from then on he called me ‘Rabbit’. That was his pet name for me. He was born in the Year of the Ox, so I didn’t do the same.

We had a fantastic two weeks together, full of music and city lights (and I guess the food and wine didn’t hurt the atmosphere). At the beginning of March a neurology appointment I had booked in Brighton meant I had to go to England. Omar and the band were going to Indonesia for a month to do some gigs at a club in Jakarta.

As we parted on that night in early March, he said to me, ‘See you in a month, Rabbit.’

My life was perfect. I was doing things I loved in a new and exciting city, and I’d just met someone who made the sunniest day a little brighter. I was living a dream, but I didn’t really realise how lucky I was. I took it all for granted. I guess I felt entitled to everything life could offer. As I boarded the plane, I couldn’t wait to get back and carry on living my wonderful life.

Chapter 2 Wading through Honey (#ulink_7d593648-8893-5eeb-a633-2ca1117a34f3)

The reason I had a neurology appointment was because I’d been noticing my body behaving a bit strangely over the last year or so. There were lots of little things – nothing major – but they seemed to indicate something odd was going on.

The weirdest incident had been in August 1994, when I’d collapsed in the street back in Yorkshire, where I lived at the time. I’d spent the day walking around Leeds city centre with an American friend called Greg, who was thinking of moving to the UK and wanted to explore what kind of work he might be able to get. We’d walked for miles into recruitment companies and coffee shops. Greg needed to get a feel for the city as well as the jobs. On the way back, when we were only a couple of hundred yards from my home in Bradford, all of a sudden my legs gave way beneath me and I collapsed on the pavement.

‘What’s going on? Did you trip?’ Greg stretched out an arm to help me.

‘I don’t know.’ I grabbed his hand and tried to pull myself up, but my legs wouldn’t take my weight: they were weak and unresponsive. ‘Isn’t that strange?’ I felt silly more than anything else. Greg was super-fit, and although I knew I’d been getting a bit out of condition, I hadn’t thought it was quite that bad.

‘Can’t you get up?’

‘I just need to rest a while and then I’ll be fine.’ At least, I hoped I would.

‘Try again,’ Greg coaxed me, concerned and more than a little embarrassed to be seen with a woman who was sitting in the gutter on a busy main road. People passing clearly thought I was drunk.

I summoned all my strength, clung on to Greg’s arm and tried to haul myself up, but my legs still wouldn’t support my weight. An image of the Billy Connolly sketch in which he imitates a Glaswegian ‘rubber drunk’ flashed through my head. I had rubber legs, it seemed, without a drop of booze having passed my lips.

‘It’s no use,’ I said. ‘We’ll have to call a cab.’

Greg seemed glad to be given something to do. Before long he was helping me into the back of a local cab. Two minutes later Greg and the driver got me into the house by holding me on either side and more or less carrying me until I was ensconced in an armchair in my front room.

‘You have to see a doctor,’ Greg insisted. ‘That shouldn’t happen. Shall I phone for someone?’

‘If you want to do something useful,’ I told him, ‘make a cup of tea.’ A universal British cure-all.

We sat and drank our tea and talked about the job opportunities Greg had found, and a few hours later my legs seemed to be back to normal, so I brushed aside all his nagging about doctors and tests and making a fuss. I’m an arrogant sod and prided myself on my physical prowess. I’d completed several parachute jumps, skied, played netball for my county team and learned to waterski off Hong Kong, so a day’s walking shouldn’t have fazed me.

Over the next couple of weeks, though, I gave it some more thought, wondering what was going on and whether I needed to do anything about it. I’d noticed a few other odd things. For example, I was a keen horse-rider, but now it took me quite a lot of effort to get my foot in the stirrup and swing myself up on to the horse. I’d always had a good seat, which you achieve by using your thigh muscles to hold your position on the saddle, but recently I’d been a bit like a sack of potatoes being bounced around as the horse cantered across the field.

Then there was my eyesight. I’d noticed that words were getting slightly blurred on the page. Curiously, it seemed to get worse when I was too hot. I figured that everyone’s eyesight deteriorates as they get older, but I was only 31. Should it be starting that early?

Having lived all over the world, I’d been back in the UK for almost four years before I moved to Singapore in September 1994 and I blamed the British climate for many of my symptoms. I’d put on a bit of weight, so that could have been one factor, but I mostly blamed the sedentary indoor life I’d been leading. When I was out in the Far East, I was always rushing around waterskiing, swimming or cycling. On Christmas Day we would spit-roast a turkey on the beach, decorate palms with tinsel and splash around in the surf. Back in cold, rainy Bradford, Christmas meant eating far too much, drinking more than was good for you and falling asleep in front of the TV.

I had come back to the UK in 1990 to help look after my mum. She had been ill for several years and my sisters had been shouldering the responsibility. I felt it was time that I shared it. When Mum died in 1992, it came as an incredible shock, despite the fact that we’d all known she was ill. It was nice to get close to my family again and I’d planned on staying for a bit, but I was beginning to feel old, putting on weight and generally feeling ‘not right’.

Then, in 1994, a friend of mine, a singer called Mildred Jones, called to invite me out to Singapore, where she had a contract at the piano bar in the Hilton Hotel. She said I could stay with her and she would introduce me to people who would help me to find work.

It was an irresistible offer and I took less than a nanosecond to reply. ‘Sure. I’m on my way.’

I found people to look after the house I owned in Bradford and booked a plane ticket for 24 September. Before I left, I decided to pay a quick visit to my GP just to be on the safe side.

I sat down in his surgery and let the words pour out. ‘I’ve been a bit out of sorts recently. I’m sure it’s partly grieving for Mum, but also I’ve put on some weight that I need to lose, and living in the UK doesn’t really suit me. I prefer a hot climate and an outdoor lifestyle. Anyway, I’m solving it by moving out to Singapore next week. What do you think?’

‘That all sounds very sensible,’ the doctor said, a bit bowled over by the speed at which I can talk when I get going.

All the symptoms I presented him with were subjective: a bit tired, feeling slightly weak, generally depressed. I answered my own questions as I spoke and he just agreed with me. I didn’t have a massive tumour anywhere. I wasn’t in pain. There was nothing concrete that might have made him suspicious that there was anything going on. Besides, I didn’t want to hear any bad news. All I wanted was reassurance. I had a plane to catch and an exciting new life waiting for me, so I more or less presented him with a fait accompli.

‘So I’m fine to go?’

‘Yes,’ he said, looking somewhat baffled by the onslaught. ‘Have a good time.’

The symptoms didn’t go away in Singapore’s sunnier climes, though. If anything, they got worse. I started walking everywhere to try and get fit but found my legs were tired after short distances, and I couldn’t swim as many lengths of a swimming pool as I used to. Then, within three weeks of my arrival, I got a phone call that shattered my world. It was from my auntie Judy’s husband, Uncle Paul.

‘Debbie?’ he said. ‘Your dad is dead.’

‘What? You’re joking!’ He’d come out with it so abruptly that I assumed it was a sick practical joke, even though I knew Paul would never be so cruel.

Auntie Judy took the phone from him. ‘I’m so sorry,’ she said. ‘I’m afraid he had a heart attack.’

‘Really? My dad? Are you sure?’ He was such a life-force it didn’t seem possible.

‘His girlfriend was with him at the time, but there was nothing that could be done. He was dead before the ambulance got here.’ She was trying hard to hold back the tears and not doing too well.

I had talked to Dad the week before I left the UK. He’d been living in the States and was due to arrive in England a couple of days before I left so that we would see each other, but work had delayed him. I’d enquired about changing my flight, but it was a cheap ticket and to change it would cost almost as much as I’d paid for it in the first place. Instead we’d agreed to meet when he came to Southeast Asia a few months later.

I put the phone down and looked around at the friends in the room. They were watching me with concern, having picked up the gist of the call.

‘I’m an orphan,’ I told them, before bursting into tears.

The shock was monumental. How could there have been no warning signs at all? It felt like the end of the world.

One of Mildred’s friends bought me a plane ticket home for the funeral, and my sisters, Tina, Gillian and Carolyn, and my brother, Stephen, and I clung to each other in disbelief. More than two years had passed since Mum’s funeral, but it felt very recent. We hadn’t lived with Dad for a long time, but we still felt bereft. Even in your 30s you want to feel that you have someone to fall back on. Uncle Tony and Auntie Judy, his brother and sister, were inconsolable. They had been close to him all their lives and the three of them adored each other.

A few days after the funeral I caught a flight back to Singapore. I didn’t know what to do, but I wanted to stay busy or I would have sat and sobbed all day long. I’d moved into the flat with Belinda and Tetsu, and there were always people milling around and gigs to attend. I said yes to every invitation as a way of keeping myself afloat, otherwise I would have sunk under the weight of grief.

Two weeks after I got back, in November 1994, Auntie Judy called again, utterly heartbroken. She was stuttering and could hardly get the words out. ‘Tony died. It was a heart attack.’ Apparently he was making a cup of tea when he collapsed and was dead before he hit the floor. He didn’t even disturb anything in the kitchen.

I felt numb this time. It was all too much. I didn’t have the money to fly home for another funeral, so I grieved in Singapore. Still shell-shocked about Dad, it was hard to take in this new piece of information.

Then there was a third blow. On the night of Uncle Tony’s funeral, Auntie Judy died as well. I think she died of a broken heart, because she was so distraught at losing her brothers. They’d all three been so close in life that somehow it made sense that they died close together. I think it would have been unbearable for the ones left behind if it had been any other way. Nevertheless, it was devastating for the family to have three funerals in a row.

I put my head down and tried to get on with life in Singapore. What else could I do? Being on the other side of the world helped to make it seem unreal. Part of me still felt that when I next went home they’d all be there, same as ever.

Mildred was like a mother to me in this period, sweeping me up into her vast group of friends and making sure I didn’t mope around too much. Belinda saw to it that I ate and slept, and I still had my work for the adventure travel brochures and the music magazines. I spent most evenings at clubs and live music venues, and I’d usually be up on the dance floor.

I love dancing, and I was lucky enough to have been born with a decent sense of rhythm (tone deaf, but I could move), but strangely I found my body wasn’t moving the way I wanted it to. I felt as though I was wading through honey, or as if I was wearing trainers and they were sticking to chewing gum that someone had dropped on the floor. (Unlikely, as the Singaporean government had banned the sale of gum.) It wasn’t that I was tired; my movements just felt slow and strange. I thought it was because of the extra weight I’d put on back in England, so I borrowed a bike to cycle around town and get fitter. I wasn’t fat, but I definitely wasn’t as toned as I’d have liked to be.

Soon after Dad’s funeral I began to have the weirdest headaches I’d ever had in my life. It felt as if something was reaching inside my skull and squeezing my brain. They only lasted for a few seconds at a time, but they were intensely painful. I became convinced that I must have a brain tumour. This was in the days before Mo Mowlam, the Labour Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, died as a result of her brain tumour, and my preconception was that they were quite a sexy thing to have. I’d go into hospital, have my head shaved, undergo brain surgery and then recuperate. Everything would be better within a few months and I thought it would be quite exciting. I could be ‘heroic Debbie’ with my bald head, admired for my stoicism.

I flew back to England to spend Christmas with my family, and while I was up in Yorkshire I went to see a GP, presented him with my self-diagnosis and asked to be referred for a CT scan. He didn’t play along, though.

‘Let me put it this way,’ he said. ‘We doctors have to do a kind of jigsaw puzzle. Say you find a bit of blue sky. You might not know exactly where it fits, but you know it’s sky.’

I concentrated hard, trying to work out how this related to my headaches and muscle weakness.

‘There’s nothing physically wrong with you,’ he continued. ‘You were grieving for your mum and felt terrible about losing her, and then your dad died. It’s all happened at once. I’m going to refer you to a therapist who can help you to talk it through.’

So that was it! Depression wasn’t as sexy as a brain tumour, so I was a bit disappointed. I still clung to my ‘heroic Debbie’ image. I’d never been the depressive type and I wasn’t sure I believed his diagnosis, but doctors are always right, aren’t they?

I went down to stay with my uncle Paul in Brighton before my flight back to Singapore. As it happened, his friend’s son had had a brain tumour and they urged me to get a second opinion. They just had an instinct that my doctor’s diagnosis wasn’t quite right.

I went to see my uncle’s GP, a smart, no-nonsense woman with a surgery in Brighton. After listening to my description of the symptoms, she got me to lie down and drag my heel up my shin – first the left heel, then the right. I managed it, but there must have been something she didn’t like about the way I did it. She ran a few more tests and asked me lots of questions, then said she was going to refer me to a neurologist.

Good, I thought. A neurologist sounded serious and important. Surely he would be able to send me for a brain scan and we’d be a little closer to coming up with a diagnosis, something unusual and interesting.

I was warned it would be a couple of months before the appointment came through, so I went back out to Singapore, still secretly convinced I had a brain tumour. I didn’t tell Mildred or anyone else about my theory because it sounded melodramatic. In answer to their questions I said, ‘Oh, there’s nothing wrong with me,’ imagining that when I finally told them the truth they would think, Poor thing, she was trying to be brave and play it down when all along she was suffering terribly.

Peter, my boss at the adventure travel company, seemed to be happy with my work because he asked if I would like to go on a scuba-diving course on Tioman Island, off the Malaysian coast. Would I ever! The idea was that I would write a diary of my experiences that would be published by 8 Days, a magazine about what’s on in Singapore. Peter, his partner and other colleagues could already dive and they wanted someone who could write about the learning experience. Once I could dive, Peter promised that he would send me to review other scuba sites they covered.

I loved the resort on Tioman, a genuine paradise island with white sand and palm trees. The staff were bottle-feeding a little orphan monkey whose mother had been killed by poachers and everyone liked playing with him because he was so cute and cuddly.

I found the underwater world magical. If you learn to dive off the British coast, the visibility is likely to be measured in inches, feet if you’re lucky, but in the South China Sea we could see way off. It was incredible to be underwater marvelling at the rainbow-coloured fish and strange tentacled creatures, and my worries about a brain tumour faded into the distance. How could I possibly be ill when I felt so alive and exhilarated?

Back in Singapore, reality intruded when I got word that my neurology appointment would be on 6 March and the therapy session a couple of weeks later. It was time to make another trip to the UK, just after I’d started going out with Omar.

‘You won’t send anyone else on the diving trips, will you?’ I asked Peter. ‘You’ll definitely wait for me to come back?’ I think I’d have cancelled the appointments otherwise.

‘It will all be here waiting for you,’ he promised. ‘Good luck!’

On 6 March 1995 I turned up for my neurology appointment at the Royal Sussex County Hospital. I recited the list of symptoms, mentioned that my parents had died recently and ventured my humble opinion that I might have a brain tumour.

‘Lie down on the bed,’ the neurologist instructed. ‘Tell me what you can feel.’

I could see he was holding a pin, and as far as I was concerned he just touched it lightly on my foot, pressing a bit harder as he moved up my leg, then stabbing it into my thigh. That’s what I told him.

‘Actually, I applied the same pressure all the way up,’ he told me.

I blinked in surprise. It seemed I had reduced sensation in the lower parts of my legs. What on earth did that mean?

‘I’m sending you for an MRI scan,’ he said. ‘We’ll talk after that.’

I went back to my auntie Pat and uncle Dennis’s house where I was staying, puzzled by the fragments of information I’d gleaned. Why would a brain tumour cause reduced sensation in my lower legs? Was that why I’d been feeling weird when I was dancing, and why I’d collapsed in the street that day with Greg?

I’d heard it took months for MRI appointments to come through, but mine only took about ten days. Why was it so fast? Was it due to mega-efficiency on the part of the hospital, just good luck, or had the neurologist told them it was urgent?

‘It will take about forty-five minutes,’ the radiographer told me. ‘You have to lie very still on a bed that will slide inside a hollow tube, where we will take pictures of your insides a bit like a 3D X-ray. It’s a bit noisy in there, so you’ll need to wear some earplugs.’

I lay down on the bed, earplugs in place and a call button in my hand in case I got a sudden attack of claustrophobia. I was swept into the machine. There was a moment of silence, then a cacophony of clanking and long piercing beeps and a churning, whirring sound. After only a few minutes the noise stopped and I was sliding out again.

‘What’s up? You said it would take longer.’

‘I’ve got all I need,’ the radiographer told me.

‘You’ve found something, haven’t you? Is it a brain tumour?’

‘The consultant will study the images and discuss the results with you. He has to interpret them.’

I knew they had found something. They must have. Why else had it only taken a few minutes? But they wouldn’t tell me.

I was due to travel up to Yorkshire the next day to see the therapist I’d been referred to, but I rang my neurologist first.

‘Should I go to Yorkshire?’ I asked, and explained the situation.

‘No, come in to see me tomorrow morning at ten to nine, before surgery starts.’

That’s when I knew for sure that they’d found something. I spent the night imagining the worst and trying to talk myself round. My aunt and uncle drove me to the hospital the next morning and at my request they waited outside in the car park. I wanted to face this on my own.

‘So what is it?’ I asked as I sat down, more nervous than I was when I sat my O levels – and that’s saying something.

The consultant looked grave. ‘When I first saw you, I thought you had MS.’

I waited for the other shoe to drop.

‘And it is MS.’

It’s normally hard to shut me up, but I couldn’t think of a single thing to say. The consultant continued that he was going to refer me for a lumbar puncture so that he could definitely rule out a couple of other things, but said he was convinced it was multiple sclerosis. He had been pretty sure from my gait when I first walked into his office, and the MRI scan had backed up his instinct. We made an appointment to talk again after I’d had the lumbar puncture.

I left his office and walked back down to the car park, where my aunt and uncle were waiting, and still I couldn’t speak. I got into the car and stared at them wordlessly with an overwhelming sense that my life had just changed for ever.

Then I rejected it. He had to be wrong. Please, God, he simply had to be.

Chapter 3 ‘Can I Scuba-Dive?’ (#ulink_b9f8d3e3-60e4-5ed4-8e7f-b93408787455)

The only thing I knew about multiple sclerosis was that it was not a good illness to have. All I could think of was a poster I’d seen of a girl with her spine torn out and the legend ‘She wishes she could walk away from this picture too.’ Did that mean I wouldn’t be able to walk any more? That’s when I began to get upset. I couldn’t bear it if I ended up in a wheelchair.

I was in a complete state when I rang my best friend, Vera, a Viking from Oslo. ‘My life is over,’ I wailed. ‘Omar won’t want to go out with me any more. No man will. My friends won’t want to be my friends any more because I’ll be stuck at home and I won’t be able to go out. No one will want to know me. I’ll be useless.’ I must have sounded shrill and tearful.

Vera listened to my rant and then breathed deeply. I could feel her shifting her position to give the verbal equivalent of the slap you deliver to a hysterical woman.

‘You idiot! You can’t think very much of your friends if you think that. If I told you I had MS, would you stop being my friend?’

‘No, but—’

‘Well, how dare you even think I would stop being your friend just because you’ve got some disease! You wouldn’t abandon me, so why would I abandon you? Stop wallowing in it. Grow up and get on with your life!’

I felt myself start. The result was pretty much as if she had indeed delivered a heavy slap: the shock brought me back to reality. This wasn’t a romantic game, it was reality, and I was going to have to get used to it. I don’t like to admit it, but if things are out of my control I have a tendency towards self-pity. If anything was going to drive people away, it would be that, not the diagnosis. I rang a few of my more pragmatic friends to sound them out. I didn’t want people who would gush with sympathy. I wanted facts.

‘Don’t worry,’ one friend told me. ‘They’ve got a cure for it now.’ A drug called beta-interferon had been all over the news recently. ‘If you start taking it early enough, it’s got a really high success rate.’

How long had I had the disease, though? When had I first noticed my legs were getting weaker? Lots of memories flooded my brain. I thought back to when I was learning to waterski in Hong Kong in 1988, seven years earlier, and I hadn’t been able to stand up in the water. We’d tried over and over again, but I hadn’t been able to rise elegantly from the water, so I’d sat on a jetty and they’d towed me off from there. I remember feeling frustrated. Had that been an early symptom of MS, or was it just me being clumsy and impatient? (My MS has probably been unfairly blamed for many failings over the years, but if I’ve got to put up with the disease I may as well.)

I phoned other friends. Some told me they knew people with MS whose lives were barely affected. They still walked, held down jobs, had children and you’d never know they were ill except that they occasionally got a bit tired. That was comforting – that’s what I wanted to hear. I’d hoped it was a brain tumour because I’d imagined that, once treated, I’d get back to my normal self without any further repercussions, but I reckoned I could cope with a mild dose of MS that was controlled by taking this new miracle-drug, beta-interferon.

I phoned my old friend Mike. He was living in Vienna but happened to be in Paris, and he said, ‘Come out for the weekend. We’ll take your mind off things.’

We strolled along the Seine, stopping for coffee whenever my legs got tired and I started staggering. Passersby gave me scathing looks, thinking I was drunk, and I wondered if this was something I’d have to get used to.

‘Hello? Since when have you worried about what other people think?’ Mike teased.

In the evenings we went to piano bars and listened to chanteuses singing of unfaithful lovers and lost chances. It was good to be in another place, distracted from what was going to happen to me in the coming week, never mind the coming years. Mike had just broken up with his partner, the mother of his son, so we talked about that at length and didn’t dwell on my diagnosis. The only advice he gave me was about practical things, like making sure I had the insurance policy on my mortgage on my Bradford house sorted out before the diagnosis was official. Did I even have an insurance policy? I hadn’t a clue.

‘Are your savings in a high-interest, easy-access account?’ he asked.

‘What savings?’ Didn’t he know me at all? I wasn’t the kind of girl who had savings. I lived for today, spending every penny as I earned it and sometimes even before.

Still, I pretended to take note of all Mike’s nuggets of wisdom. It was good to focus on hard facts rather than speculate about the disease, and I was glad he was taking this approach and not smothering me in sympathy.

On Monday morning, after my weekend in Paris, I flew back into Gatwick Airport at 9 a.m. and jumped on a train straight to the hospital, only making it on time for my lumbar-puncture appointment because of the one-hour time difference between France and England.

The procedure was straightforward. I lay on my side on a hospital bed and curled up in a foetal position so that the doctor could stick a needle into my spine and extract some spinal fluid for testing. I was fine for the rest of the day, but the following morning I woke early feeling like I had the worst hangover of my life, with a God-awful, teeth-grinding headache that lasted for days. (I don’t object to a hangover if I deserve it, but this was just unfair.) Not everyone reacts like this to lumbar punctures, I hasten to add. More than 80 per cent of patients feel fine afterwards. Just my luck to be in the wrong percentage.

I made up a list of questions to take to my next appointment with the consultant a few days later and tried to compose myself. I wanted to come across as intelligent and able, the kind of person he would be glad to have as a patient. I wouldn’t break down or become hysterical; I’d be rational, logical and calm.

‘Are you absolutely sure it’s MS?’ I asked first, a germ of hope still lingering that he might have got it wrong. ‘Isn’t there anything else it could be?’

‘I could see the scleroses in your MRI and the lumbar puncture confirmed that it wasn’t anything else,’ he said.

‘What are “scleroses”?’ I hoped this wasn’t a dumb question.

‘Your central nervous system is like the wiring in your house. All electric cables have plastic round them to make sure that when you switch on an appliance the current just goes down the wire from the mains to the appliance. If you have a break in that plastic coating, the current leaks out and the appliance doesn’t work.’

I nodded. That made sense so far.

‘In the central nervous system the equivalent of the plastic surround is a fatty tissue called myelin. When there is damage to the myelin, it’s called a sclerosis. This disease is called multiple sclerosis because there are several places where the myelin has degenerated.’

‘How many?’

‘Different people have different degrees of the disease. If they just have a few small scleroses in unimportant areas, they might never notice any symptoms. If they have big scleroses in important areas, they will have more problems.’

‘Like not being able to walk?’

‘Like not being able to walk.’

I took a deep breath. ‘So what are my scleroses like?’

‘Not too bad. We’ll just have to wait and see how things progress.’

That was something. At least he hadn’t said, ‘Huge, gigantic, massive.’

‘I’ve heard about this drug beta-interferon. Should I start taking it straight away?’

‘I’m afraid you’re not a suitable candidate for beta-interferon,’ he said, dashing one of my pet hopes. ‘There’s a type of MS called relapsing-remitting and research suggests this drug may reduce the frequency of relapses, but I think you have another type called primary progressive. You’ve shown a pattern of mild but continuous symptoms, rather than severe episodes followed by periods of remission.’

‘Is that better?’ I wanted to ask, but didn’t. I had a feeling it wasn’t. I didn’t like the sound of the word ‘progressive’. Instead I asked, ‘What’s going to happen?’

‘Debbie, the only thing I can tell you is that it’s not going to get any better. That’s pretty much it.’ He was watching me closely for a reaction, but I was too busy weighing up his words and trying to read causes for optimism into them. ‘Get on with everything you want to do whenever you want to do it, and when you find you can’t do something, just stop.’

‘OK,’ I said cautiously.

‘Meanwhile I think we should measure you for a walking stick to help broaden your base.’

What? My base is broad enough as it is, thank you. (Like I said, my bottom just can’t be disguised, but people don’t have to comment!)

The neurologist obviously saw my confused expression. ‘I mean to steady your walking,’ he replied, smiling. ‘You’re dragging your left foot a bit.’

My walking was particularly wobbly because I’d sprained my ankle navigating some uneven ground with Mildred’s partner just before I left Singapore. We’d gone out walking in a quest for fitness and had ended up having to take a taxi home after my stumble. The episode seemed ridiculous now.

‘OK,’ I said. I hadn’t realised you needed to be measured for walking sticks, but apparently you did.

‘Any more questions?’ he asked, leaning back to indicate he had all day if I needed, even though I knew he had a bulging waiting room outside.

So I took a deep breath and asked the Big One: ‘There’s no cure, is there?’

‘No, there’s no cure.’

We sat in silence for a while, my mind blank. I knew there were dozens of questions I should be asking, but I couldn’t think of them and the list I’d made lay forgotten in my pocket. I decided I had better let him get on with his day, so I stood up, shook his hand and turned to leave.

I was halfway through the door when I turned back.

‘Can I scuba-dive?’ I asked, thinking about my job on the adventure travel brochures.

‘I don’t know. Can you?’ he replied.

It took me a few more days to process and digest all the information he had given me because it was just so contrary to what I’d expected. I’d had a good life and thought of myself as a lucky person. Suddenly things were running away from me, escalating out of my control. I’d been expecting to be diagnosed with something serious but curable, not some incurable illness that would just keep plodding on relentlessly. I wanted something glamorous with bells and whistles. I wanted miracle-drugs and dramatic surgical interventions and cutting-edge medical breakthroughs.

‘This is it, the end of my life,’ I sobbed to my sister Carolyn. ‘It’s going to get worse and worse and then I’ll die.’

‘Stop being so histrionic,’ she told me. ‘The doctor might have got it wrong. Even if he’s right, there’s bound to be something that can be done. We’ll just find out what it is and we’ll do it.’

Although they’re very different personalities, all my siblings reacted in much the same way. My brother, Stephen, was typically matter-of-fact: ‘Right, OK, let’s get on with things, then. No point making a fuss.’

The neurologist had said it was incurable. How was that possible? If my dad were still alive, I knew he would have found a cure. He’d been an incredible character. Thrown out of school at the age of 13 because he had a tendency to question the ‘correctness’ of his textbooks rather than spouting the answers teachers wanted to hear, he made a career out of his questioning mind. He was working as a photo-journalist for the Brighton News Agency when he was asked to look after a friend’s typesetting business while he was on holiday. Dad thought there had to be a better way of setting type rather than placing each letter by hand. Other people had tried, but they hadn’t been able to create the right size or shape of cathode-ray tube (the things that make televisions work). Dad didn’t have any qualifications in electronics, and he hadn’t read the books that would have told him that it wasn’t possible to manufacture a tube of the size he wanted, so he just went ahead and made the right size of tube and used it to build the Linotron 505, which was the first commercially viable cathode-ray-tube typesetting machine.

He’d always been creative. Back at the age of 13, just before he was thrown out of school, he thought of a way of improving the mechanism of wind-up gramophones and wrote to HMV to tell them about it. He got a letter by return saying they had already done it, but they were impressed by his initiative and invited him to work for them. Sadly, he had to decline on the grounds that he was just a schoolboy.

Dad had tremendous enthusiasm for a challenge, as I have, and would work on one project for a few years and take it as far as he could before moving on to the next thing. After some years working as a photo-journalist, photographer and icecream maker, he found his raison d’être in new technologies that helped to revolutionise printing. The word ‘incurable’ would never have been in his vocabulary. Like Augusto and Michaela Odone, who researched and formulated a new drug called Lorenzo’s Oil after their son, Lorenzo, was diagnosed with ALD (adrenoleukodystrophy, to give it its full name), my dad would have taken my MS diagnosis as a challenge. I’m convinced he would have cured me because he could make most things possible.

If Mum were still around, she would have given me a big hug and said, ‘Don’t worry, Debbie. We’ll get through this, whatever it takes.’ She was gone, though, and I had no one left to give me a mother’s unconditional love.

This thought made me cry more than any other. I had to face this on my own, without parents. If my dad had still been alive, I’d have gone to stay with him in America and let him take care of me. I’d have felt more secure if I had even just one parent to fall back on. My sisters and brother were sympathetic, but they had busy lives with jobs and partners, and I didn’t want to move in with them and lie on a sofa waiting for things to get worse. I had to figure out how to manage this disease on my own.

Should I stay in the UK to be near my doctors? Should I go back out to Singapore and try to carry on with life as it had been before? That seemed to be what the doctor was suggesting, but I was scared I wouldn’t be able to manage on my own out there if my symptoms worsened.

And what about Omar? We’d only been dating for two weeks before I came back to the UK for my appointments. He couldn’t be expected to take my problems on board. I didn’t even know how I could begin to explain them to him, given the language barrier. He would still be in Jakarta, but I had a phone number for the club there, so I decided to call and attempt to explain what had happened.

First of all, I rang the Spanish Embassy in London and asked the woman who answered the phone, ‘How do you say “multiple sclerosis” in Spanish?’

‘Esclerosis múltiple,’ she told me. (So glad I got that sorted!)

Then I rang Omar and tried to tell him, in our usual mishmash of languages, what was wrong.

‘Je suis malade. Esclerosis múltiple.’

I was crying and I hadn’t a clue what he was saying or even whether he had understood, but the calmness of his tone was comforting.

‘No te preocupes. Come back to Singapore.’

‘OK,’ I sniffed. I’d had a look at the flights and there was a cheap one available on 3 April, so I told him I would get that.

‘See you at Fabrice’s!’ I said, hoping he would pick up on the name and understand what I meant.

When I walked through the arrivals gate at Changi Airport expecting to be met by my boss, Peter, there was Omar standing waiting for me. I’ve never been so pleased to see anyone in my life. I ran into his arms and hugged him tightly, so relieved I couldn’t speak. It was a wonderful, euphoric feeling. But what was he doing there? How had he known which flight I was on? I hadn’t mentioned it to Mildred and he didn’t know Peter.

Peter arrived and was able to translate for us. Although he’d grown up in Germany, he and his mother were Russian, and Omar spoke Russian, so they could communicate much more easily than Omar and I could. It seems Omar had got to the airport first thing that morning and had met every single incoming flight until I arrived after lunch.

I hugged him again, overwhelmed by my emotions.

I’d been planning to stay with Peter and his partner for a while. I wasn’t sure how much work I’d be able to do, but staying with Peter would make it easier to try. I figured I’d stay in Singapore long enough to pick up my things, and maybe enjoy the city a little before having to make proper plans about my life! The immediate plan was that Peter would drive me to my flat to pick up my stuff, then take me back to his place.

When this was translated for Omar, he said not to be ridiculous. He insisted that I was to move in with him and the band. He was squeezing my hand as he spoke and looking very serious.

‘Vente a vivir con nosotros – conmigo,’ he insisted.

I thought about it for two seconds, then smiled at him and said, ‘OK!’

Peter grinned.

We picked up my belongings and drove to Jalan Lada Puteh, or Peppertree Lane, where Omar lived in a house with the three girls and six boys who were members of the band.

My parachute had opened. Omar was going to take the weight.

Chapter 4 My Beautiful Career (#ulink_aa3b15ad-4d51-5997-8b7d-65aff0634dc8)

After leaving school I led a nomadic lifestyle, never staying in one place for long. My short attention span and love of adventure meant that once I felt I’d experienced a situation, I was ready to move on. This quality used to get me into trouble back at school and college, but after the MS diagnosis I felt grateful for it. Sometimes when fear and grief for my lost life got too much, I would hide in bed, pull the covers right up over my head and cry. I’d sob my heart out, feeling desperate and helpless, but then I’d hear a story on the News Channel (it’s been permanently on in my bedroom for years, only turned off at night if Omar is at home) that would make me gulp back the tears. It’s hard to feel devastated by your problems with walking when you can see the effects of the tsunami in Southeast Asia, people caught in the wreckage of Hurricane Katrina or bombs dropping on Gaza. The footage of those disasters showed people in unimaginable situations dealing with their lives as best they could, and I guess it put my problems into perspective. I could turn on the tap and get fresh, clean water to take my prescription painkillers, just phone a friend for a chat or use the computer to contact friends further afield. I will always need to mourn the ‘me’ that I’ve lost, but the desperate face of a mum who has lost her child to the war in Iraq makes me so grateful for the ‘me’ I’ve still got and not want to miss out on the things I can do.

My schoolteachers always used to complain that I didn’t apply myself, and none of them would have been surprised that by the age of 30 I’d done umpteen different jobs but never had what you might call a ‘proper career’. I took A levels in maths, economics, government and politics, and sociology, because since the age of 13 I had wanted to be prime minister. (I took maths because I was good at it and figured it would be useful if, as prime minister, I could at least balance a chequebook.) There were always lively political discussions at the dinner table at home, and with the arrogance of youth I thought I could solve the world’s problems by making the political system more fair and inclusive. I joined the Liberal Party and committed a lot of time and energy to the causes I believed would improve the world – as well as the ones that looked most fun.

I spent a couple of years knocking on doors campaigning for local councillors, and I learned wheelchair basketball and helped out at Sports Association for the Disabled. I planned to change the world by improving my corner of it. However, the more I learned about society, the more I realised that tweaking the existing status quo would be harder and less effective than building a new one. I began to read more political literature, and the more I read the more I considered myself a Marxist.

I took two of my A levels at a further-education college in Windsor. I remember my time there mainly for that first parachute jump with the Territorial Army, back in 1981, sparking my lifelong addiction to adrenaline rushes. About fifty of us, male and female, had signed up for the jump. During a couple of days away from college, I thought better of it and returned planning to drop out, but I discovered that of our original fifty, only six remained, all of them boys. That made me the last girl standing and I felt I had to do it as a matter of feminist principle.

I moved to London to do my other two A levels at a college near Old Street, and I lived in a squat – rather a nice squat, an old vicarage – with a fantastic bunch of people: a city stockbroker, a Buddhist with a motley collection of stray cats and, the reason I was there, some Marxist revolutionaries. I learned a lot, not least about choosing the battles that were most important and not being sidetracked by every little injustice you perceive. I went to Kingston Polytechnic to study sociology. Then, after a term and a half, I moved to Birmingham to read humanities (economics, politics and sociology). I made the move to Birmingham because of politics rather than education (although I think my involvement in politics was the best education available). I worked a few nights a week as a nightclub hostess, greeting people at the door and checking they conformed to the dress code (on the way in, anyway), and if we had live bands on, we had to frisk people if they looked suspicious.

In Birmingham, I decided that I wouldn’t graduate. I thought I was learning more from living, arguing and listening than I was from lectures. I bought my first house in Lozells, Birmingham, back in the days of 100 per cent mortgages, when buying was cheaper than renting. My bank manager said I should definitely go for a job selling advertising space for Thomson Directories because I had convinced him to lend me the £11,000 for the house while still a student! (These were the days when houses were homes, not investments.)

Nowadays you need a degree to become a toilet cleaner, but in the 1980s you didn’t, and when a man I met at the club offered me a job selling advertising space it seemed like a good idea. The money was better than a student grant (a historical anachronism), and although I’d had many jobs since the age of 14 – including working in a farm shop, plucking Christmas turkeys, mucking out stables and working as a hospital cleaner – this would be the first real one. It seemed about time I had a job that meant I’d stay clean, warm and dry, and that I needed to dress properly for.

I was something of a fashion victim in those days, but the phases never lasted very long. I was punk for a week or so, but found the look too uncomfortable and got impatient with the amount of time it took to get ready in the morning. For a while I had a short back and sides with tufts of differentcoloured hair – orange and blue and pink – and I’d wear tight little black dresses, making me look like a parakeet.

I started the telesales job in Birmingham, but when some friends were moving to Edinburgh I went too and found a field sales job for the Scotsman. Then, within a year, I got a job with Yellow Pages. I loved the variety of working as a field sales rep: at 9 a.m. I could be at the stylish offices of a multinational corporation, at 10.30 in a draughty barn talking to a farmer about his plant-hire sideline, and at noon I might be at a local tanning salon. I met loads of wonderful people and travelled all over Scotland and the north of England, feeling energised by my life and the people in it. Even so, I still found myself hankering after change.

My dad had been working a lot in the United States for most of the last decade, leaving my mum at home in Britain, but in 1985 he took a contract in Oslo. The following year I decided to go out and stay with him for a while. We’d only seen each other sporadically while he was in America and I missed him. We spoke on the phone, but it wasn’t the same as being part of each other’s lives. In fact, on arrival, I realised there was a rather major piece of news he hadn’t shared with me – a girlfriend called Eppy, who had two kids, aged about 12 and 15. He had never mentioned this part of his life and I was surprised, to say the least.

The night I arrived in Norway, Dad took me to stay with some Norwegian friends so he could explain to me about his living arrangements on neutral territory. He wasn’t sure how I would react, but he told me that his marriage to Mum had been unhappy (what a surprise!) and that he had been with Eppy for several years. The children were hers, not his. I was sad that he hadn’t been able to share this with his children sooner. Despite his free-thinking scientific brain, he was still conditioned by society to keep up a pretence and avoid admitting that his marriage had failed.

I must be jinxed! Not long after I arrived, the company Dad was working with went out of business, so he wasn’t needed and returned to the States. I loved it in Norway, even in winter temperatures of minus 20 degrees, and I decided to stay. I got a job selling jewellery on a market stall, which turned out to be virtually the only stall in the area that had a licence to trade. There were dozens of illegal stalls, and when the police came by, everyone would quickly load their goods under my stall and disappear.

Lots of different nationalities lived side by side – Palestinians, French, Algerians, Germans, Americans – selling jewellery, trinkets and dodgy records. There was a great community feeling. The Norwegian company Dad had worked with had paid the lease on his house for almost another year, so I stayed on when he left and shocked the neighbours by letting a few of my bohemian friends move in. One of them taught me to ski, which I took to straight away. Living in Oslo was fantastic. Great cross-country or downhill ski runs were only a short bus, tram or boat ride from the city. To me, getting there was as much fun as being there. They weren’t flashy slopes with smart restaurants and multiple chairlifts, like you find in the fashionable resorts in the Alps – just clean, family-oriented spaces. That didn’t cost anything.

A girl I met while working on the jewellery stall took me to the Café de Paris one night and I immediately loved the friendly atmosphere. The owners were a Norwegian-Algerian woman and her French husband, both of whom treated the club like an extension of their home, rather than a place of business, and it worked. It had such a warm, welcoming atmosphere, and it was a second home for a lot of foreigners – French-speaking Africans, African-Americans from the NATO base and of course a wide-eyed English girl. When they offered me a job behind the bar, I decided to accept. I continued working on my jewellery stall by day and took up residence behind the bar of the Café de Paris by night. If they hadn’t paid me to be there, I would have spent all my money on the other side of the bar. It was home-from-home and my time there would prove to be one of those rare life-changing experiences because I met loads of people who would become friends for life: my best friend Vera, Greg (the friend who was with me the day I collapsed in Bradford), Chris Merchant, who was an English singer, the American club manager Dwayne, and Mildred Jones, the singer who eventually coaxed me to Singapore.