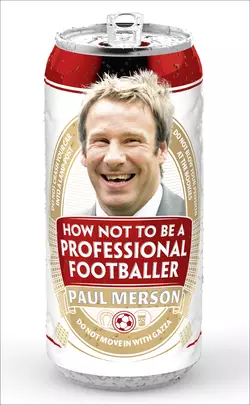

How Not to Be a Professional Footballer

How Not to Be a Professional Footballer

Paul Merson

An anecdote-driven narrative of the classic footballer's ‘DOs and DO NOTs’ from the ever-popular Arsenal legend and football pundit Paul Merson, aka ‘The Merse’.

When it comes to advice on the pitfalls of life as a professional footballer, Paul Merson can pretty much write the manual. In fact, that's exactly what he's done in this hilarious new book which manages to be simultaneously poignant and gloriously funny.

Merson was a prodigiously talented footballer in the 80s and 90s, gracing the upper echelons of the game - and the tabloid front pages - with his breathtakingly skills and larger-than-life off-field persona.

His much-publicised battles with gambling, drug and alcohol addiction are behind him now, and football fans continue to be drawn to his sharp footballing brain and playful antics on SkySports cult results show Soccer Saturday.

The book delights and entertains with a treasure chest of terrific anecdotes from a man who has never lost his love of football and his inimitable joie de vivre through a 25-year association with the Beautiful Game.

The DO NOTs include:

DO NOT adopt 'Champagne' Charlie Nicholas as your mentor

DO NOT share a house with Gazza

DO NOT regularly place £30,000 bets at the bookie's

DO NOT get so drunk that you can't remember the 90 minutes of football you just played in

DO NOT manage Walsall (at any cost)

How Not to be a Professional Footballer is a hugely entertaining, moving and laugh-out-loud funny story.

HOW NOT TO BE A

PROFESSIONAL FOOTBALLER

PAUL MERSON

with Matt Allen

Contents

Title Page (#u0119fb13-1152-5b3d-9a64-7170185f0b3c)

A Note from the Author

Introduction - Last Knockings

Lesson 1 - Do Not Go to Stringfellows with Charlie Nicholas

Lesson 2 - Do Not Drink 15 - Pints and Crash Your Car into a Lamppost

Lesson 3 - Do Not Cross Gorgeous George

Lesson 4 - Do Not Shit on David Seaman’s Balcony

Lesson 5 - Do Not Bet on Scotland on Your Wedding Day

Lesson 6 - Do Not Wax the Dolphin before an England Game

Lesson 7 - Do Not Go to a Detroit Gay Bar with Paul Ince and John Barnes

Lesson 8 - Do Not Wander Round Nightclubs Trying to Score Coke

Lesson 9 - Do Not Get So Paranoid That You Can’t Leave the House

Lesson 10 - Do Not Ask for a Potato Peeler in Rehab

Lesson 11 - Do Not Miss a Penalty in the UEFA Cup

Lesson 12 - Do Not Leave Arsenal with Your William Hill Head On

Lesson 13 - Do Not Let Gazza Move into Your House

Lesson 14 - Do Not Ask Eileen Drewery for a Short Back and Sides

Lesson 15 - Do Not Give Gazza the Keys to the Team Bus

Lesson 16 - Do Not Tell Harry Redknapp You’re Going into Rehab only to Bunk off to Barbados for a Jolly

Lesson 17 - Do Not Smile at a Sex Addict Called Candy

Lesson 18 - Do Not Try to Outwit Jeff Stelling

Lesson 19 - Do Not Admit Defeat (the Day-to-Day Battle)

Appendix

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

A Note from the Author

One thing before we crack on: an apology. You’ll only hear it from me on this one page because I’ve read too many life stories and books where people are constantly tripping over themselves to make up for all the bad things they’ve done. Page after page after page of it, and after a while it just doesn’t ring true.

The thing is, you’re going to read a lot of bad things over the following pages, and some of it is pretty shocking. The last thing you need to get through is a million and one apologies as well, so you’re only reading the one, but it’s sincere. For the terrible things I’ve done and to some of the people I’ve hurt and let down: I’m sorry.

Introduction

Last Knockings

I’ll tell you how bad it got for me. At my lowest point as a gambler, the night before an away game for Aston Villa, I sat on the edge of my bed in a Bolton hotel room and thought about breaking my own fingers. I was that desperate not to pick up the phone and dial in another bet. At that time in my life I’d blown around seven million quid with the bookies and I wanted so badly to stop, but I just couldn’t – the next punt was always too tempting. Slamming my own fingers in a door or breaking them one by one with a hammer was the only way I knew of ending the cycle. It was insanity really. The walls had started closing in on me.

When I was bang on the cocaine, I sold my Arsenal blazer to a dealer because I’d run out of money in the pub and I was desperate to get high. All the lads at Highbury had an official club jacket, tailored, with the team crest emblazoned on the front. It was a badge of honour really, something the directors, coaching staff and players wore with pride. It said to everyone else: ‘Being an Arsenal player is something special.’ It meant nothing to me, though, not at my most desperate. I was out of pocket and there wasn’t a cashpoint around, so I swapped it for one pathetic gram, worth just £50. The next day I told Arsenal’s gaffer, George Graham, that the blazer had been nicked out of the back of my car. Well, at that stage in my life a made-up story like that seemed more realistic than the truth.

At the peak of my game, I was drinking more lager tops than the fans. I would go out three, four, five nights a week and drink pints and pints and pints, usually until I couldn’t drink any more. Some nights I wouldn’t go home. I’d leave training, go on the lash, fall asleep in the bar or finish my last beer at silly o’clock. Before I knew it, I was in a taxi on my way to training, then I’d go through the whole cycle all over again. Unless I’d been nicked, that is.

That happened once or twice. One night, I remember going into the boozer for a few beers and a game of pool with a mate. We got plastered. While we were playing, some lads kept having a go at us, shouting across the bar and making wisecracks, probably because they recognised me. This mate of mine was a bit of a wild card, I never knew how he was going to react when he was pissed. This time he blew up with a pool cue. A chair was thrown through the window; he smashed up the optics. It all kicked off and there was blood everywhere. The bar looked like a scene from a Chuck Norris film.

We ran home. I was covered in claret, so I chucked my shirt in the washing machine, turned it on and went to bed. That was my drunk logic at work: I thought the problem would magically disappear if I stuck my head under the covers. I even ignored my now ex-wife, Lorraine, who was standing there, staring at me, wondering what the hell was going on as I pretended to be asleep. It wasn’t long before the police started banging on the front door. Lorraine let them in, and when they steamed into the bedroom, I made out they’d woken me up.

‘Ooh, all right officer,’ I groaned, rubbing my bloodshot eyes. ‘What’s the matter?’

The copper wasn’t falling for it. ‘Get up, you fucking idiot. You’re under arrest.’

I was off the rails, but in those days I could get away with it most of the time. There were no camera phones or random drugs tests and footballers weren’t followed by the paparazzi 24/7, which was a shame for them because they would have loved me today.

I was an England international and I played for some massive clubs. I made my Arsenal debut in 1986 and retired from playing 20 years later. In the course of my Highbury career I won two League titles (1989, 1991), an FA Cup (1993), a League Cup (1993) and a UEFA Cup Winners’ Cup (1994). I won the Division One title with Portsmouth in 2003 and got promotion to the Premier-ship with Middlesbrough in 1998. I played in the last FA Cup Final at the old Wembley with Villa. I was capped for England 21 times, scoring three goals. I had a pretty good CV.

Off the pitch I was a nightmare, battling with drinking, drugging and betting addictions. I went into rehab in 1994 for coke, compulsive gambling and boozing. There were newspaper stories of punch-ups and club bans; divorces and huge, huge debts. I was a headline writer’s dream, a football manager’s nightmare, but I lived to tell the tale, which as you’ll learn was a bloody miracle.

Through all of that, playing football was a release for me. My managers knew it, my team-mates knew it and, most of the time, the supporters knew it, too. Wherever I went, whoever I played for or against, the fans were always great to me. Well, maybe not at Spurs, but I got a good reception at most grounds – I still do. I think the people behind the goals watching the game looked at me and thought, ‘He’s like us.’ I lived the life they did. A lot of them liked to drink and have a bet, and some of them might have even taken drugs at one point in their lives. They all thought the same thing about me: ‘He plays football for a living, but he’s a normal bloke.’ They were right, I was a normal bloke and that was my biggest problem. I was just a lad from a council estate who liked a lorryload of pints and a laugh. I didn’t know how to live any other way, and I had to learn a lot of hard lessons during my career because drinking and football didn’t mix – they still don’t.

All of my pissed-up messes are here in this book for you to read, so if you’re a budding football superstar you’ll soon know what not to do when you start out as a professional player. Treat this book as a manual on how to avoid ballsing it up, because every chapter here is a lesson. The rest of you will have a bloody good laugh, I hope, while picking up some stories to tell your mates down the boozer. Go ahead, I’m not embarrassed about my cock-ups, because the rickets made me the bloke I am today and the truth is, everyone cocks up now and then. My biggest problem was that I cocked up more than most.

Lesson 1

Do Not Go to Stringfellows with Charlie Nicholas

‘Where Merse lays the first bet, reads his rehab diary and gets a taste of the playboy lifestyle.’

It was the beginning of the end: my first blow-out as a big-time gambler. There I was, a 16-year-old kid on the YTS scheme at Arsenal with a cheque for £100 in my hand – a whole oner, all mine. That probably sounds like peanuts for a footballer with a top-flight club today, but in 1984 this was a full month’s pay for me and I’d never seen that amount of money in my life, not all at once anyway. Mate, I thought I’d hit the Big Time.

It was the last Friday of the month. I’d just finished training and done all the usual chores that you have to do when you’re a kid at a big football club, like cleaning the baths and toilets at Highbury and sweeping out the dressing-rooms for the first-team game the next day. When that was done, Pat Rice, the youth team coach, came round and gave all the kids a little brown envelope. Our first payslips were inside, and I couldn’t wait to draw my wages out. I got changed out of my tracksuit and ran down the road to Barclays Bank in Finsbury Park with my mate, Wes Reid. I swear I was shaking as the girl behind the counter passed over the notes.

‘What are you doing now, Wes?’ I asked, as we both counted out the crisp fivers and tenners. I was bouncing around like a little kid.

‘I’m going across the road to William Hill,’ he said. ‘Fancy it?’

That’s where it all went fucking wrong. I’d never been in a bookies before, but I was never one to turn down a bit of mischief. I wish I’d known then what I know now, because Wes’s offer was the moment where it all went pear for me. The next 15 minutes would blow up the rest of my life, like a match to a stick of dynamite.

‘Yeah, why not?’ I said.

It was the wrong answer, and I could have easily said no because it wasn’t like Wes was pushy or anything. In next to no time, I’d blown my whole monthly pay on the horses and my oner was down the toilet. I think I did my money in 15 minutes, I’m not sure. I’d never had a bet in my life before. It’s a right blur when I think about it. I left the shop in a daze. Moments earlier I’d been Billy Big Time, but in a flash I was brassic. All I could think was, ‘What the fuck have I done?’

At first I felt sick about the money, I wanted to cry, and then I realised Mum and Dad would kill me for spunking the cash. As I walked down the high street, I promised myself it would never happen again. I also reckoned I could talk my way out of trouble when Mum started asking all the questions she was definitely going to ask, like:

‘Why are you asking for lunch money when you’ve just been paid?’

‘Why can’t you afford to go out with your mates?’

‘What have you done with that hundred quid Arsenal gave you?’

At that time, Mum was getting £140 from the club for putting me up at home, which was technically digs. She’d want to know why I was mysteriously skint, or not blowing my money on Madness records or Fred Perry jumpers. There was no way I was going to tell her that I’d handed it all to a bookie, she would have gone mental. As I got nearer to Northolt, where we lived, I worked out a fail-safe porkie: I was going to make out I’d been mugged on the train.

Arsenal had given me a travel pass, which meant I could get back to our council-estate house no problem. The only hitch was my face. I looked as fresh as a daisy – there were no bruises or cuts. Mum wasn’t going to believe I’d been given a kicking by some burly blokes, so as I got around the corner from home, I sneaked down a little alleyway and smashed my face against the wall. The stone cut up my skin and grazed my cheeks, and I was bleeding as I ran through our front door, laying it on thick about some big geezers, a fight and the stolen money. They fell for it, what with my face being in a right state, and I was off the hook.

Nobody asked any questions as Dad patched up the scratches and cuts, and the police were never called. Later, Mum gave me the £140 paid to her by Arsenal. I thought I’d been a genius. My quick thinking had led to a proper result, but I couldn’t have guessed that it was the first lie in a million, each one covering up my growing betting habit.

As I went to sleep that night, I told myself another lie, almost as quickly as I’d told the first.

‘Never again, mate,’ I said. ‘Never again.’

Ten years after the bookies in Finsbury Park, I went into rehab at the Marchwood Priory Hospital in Southampton. Booze, coke and gambling had all beaten me up, one by one. I never did anything by halves, least of all chasing a buzz, but I was on my knees at the age of 26. That first flutter had started a gambling addiction I still carry today.

As part of the treatment, doctors asked me to write a childhood autobiography as I sat in my room. I think it was supposed to take me back to a time before the addictions kicked in, to help get my head straight. I’ve still got the notes at home, written out on sheets of lined A4 paper. When I read those pages now, it seems my only real addiction as a lad was football, and that made me sick, too.

I was such a nervous kid that I used to wet the bed. I had a speech impediment, which meant I couldn’t pronounce my S‘s, and I had to go through special tuition to sort it out. When I started playing football I’d get so anxious that I’d freak out in the middle of school games. God knows where it came from, but I used to get palpitations during Sunday League matches and I couldn‘t breathe. My heart would pound at a million miles an hour, and the manager would have to sub me because I thought I was dying. Mum and Dad took me to our local GP for help, and once I realised the pounding heart and breathing problems were only panic attacks and that they passed pretty quickly, I calmed down a bit.

I was a good schoolboy player, turning out for Brent Schools District Under-11s even though I was a year younger than everyone else. When I was 14, I was spotted playing for my Sunday morning side, Kingsbury’s Forest United, and scouts from Arsenal, Chelsea, QPR and Watford wanted me to train with them. I went down to Watford, where I saw Kenny Jackett and Nigel Callaghan play (they were Watford players, if you hadn’t sussed), and I went to Arsenal as well. I thought I’d have more of a chance of making it at Watford because of my size – I figured a small lad like me would have more hope of getting into the first team there – but my dad was an Arsenal fan, so I did it for him. In April 1982, I signed at Highbury on associated schoolboy forms, which meant I couldn’t sign for anyone else until I was 16.

The chances of me becoming a pro were pretty slim, though. I had the skills for sure, I was sharp, quick-witted and I scored a lot of goals as a youth team player, but I was double skinny and Arsenal’s coaches were worried that I might not be big enough to make it as a striker in the First Division. I definitely wasn’t brave. When I played in games, I was terrified of my own shadow. It only needed a big, ugly centre-half to give me a whack in the first five minutes of a match for me to think, ‘Ooh, don’t do that, thank you very much,’ and I’d disappear for the rest of the game, bottling the fifty-fifty tackles.

Don Howe was the manager at Highbury, and he was pushing me about too, but it was for the best. He’d spotted the flaws in my game and wanted me to toughen up. In 1984 he called me into his office, took a look at my bony, tiny frame and said, ‘I’m not making you an apprentice, son, but I am going to put you on the YTS scheme. We get one YTS place from the government, so I have to take a gamble and I’m taking the gamble on you.’

There was a hitch, though. ‘If you don’t get any bigger, we won’t be signing you as a professional,’ he said, looking proper serious.

I didn’t care, I was made up. I prayed to God that I’d fill out. I stuffed my face with food and pumped weights during the week like a mini Rocky Balboa.

In a way, getting a YTS place was like Charlie finding the golden ticket to Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory, because it was a bit of a lottery really. Any one of a dozen kids at the club could have got that spot, but they gave it to me. The YTS players in Division One were also a bonus ball for the youth system. The government paid my wages (that oner a month), so it wasn’t like the club had to fork out any cash for me. In the meantime, I was playing football and handing cash back to Maggie Thatcher in gambling taxes. Happy days all round.

But I still moaned. Being a YTS or apprentice player was a pain in the arse at times and I had to travel across London from Northolt to Highbury. Every morning without fail I’d get on the underground for 16 stops to Holborn, then I’d change to the Piccadilly Line and go the last stretch to the club. I lost count of the times I had to get off at Marble Arch to go to the loo. I had to run up the escalators of the station, nip into the khazi at McDonalds and then run back for another train.

Once I got to the ground, I’d help the other apprentices put the kit on the coach. We’d then drive 50 minutes into the countryside, train for a couple of hours and come back home again. I was constantly knackered. On the way home I’d always fall asleep on the tube. Luckily for me, Northolt was only a few stops from the end of the Central Line, so if I fell akip and woke up in West Ruislip, I didn’t have far to travel back.

It didn’t get much better for me when it came to playing football either. Because of my size I was never getting picked for the team and I was always sub. Sometimes I even had to run the line. During a pre-season game against Man United I was lino for the whole match and I had the hump, big-time. It didn’t help that my mates were getting £150 a week for working on a building site when I was only get £25.

My attitude was bad. I kept thinking, ‘I ain’t going to make it as a footballer. I’m not even playing now. What chance have I got?’ At that point I would have strolled over to the nearest construction foreman and said, ‘Give us a job’, but my dad kept saying the same thing to me again and again: ‘Keep on going.’ The truth is, I could have packed it in 50 times over.

Arsenal weren’t much of a team to look at then. When I watched them play at Highbury, which the kids had to every other Saturday, they weren’t very good. They had some great players around like Pat Jennings in goal, plus internationals like Viv Anderson, Kenny Sansom, Paul Mariner, Graham Rix and Charlie Nicholas, but Don couldn’t get them going. They were getting beat left, right and centre and the fans weren’t interested. These days, Arsenal tickets are as rare as rocking horse shit. In 1985, that team was playing in front of crowds of only 18,000.

At the same time, I started getting physically bigger and tougher in the tackles, which was a shock for everyone because my mum and dad were small. Suddenly I could look over the heads of the other fans on the North Bank. In matches I started being able to read the game, and I became what the coaches would call ‘intelligent’ on the pitch. Off it I was a nightmare, but when I was playing I was able to see the game unfolding in front of me. I could picture where players would be running and where chances would be coming from next, which a lot of other footballers didn’t. And I was lucky, very lucky, because I didn’t get injured.

See, this is the thing that people don’t tell kids about professional football: it’s so much down to luck, it’s scary. If you don’t play well in that first district game, the scout from QPR or Charlton isn’t coming back. If you get injured in your first youth team match at Wolves and miss seven months of action, chances are, you’re not getting signed. I was lucky because I avoided the serious knocks. My only bad injury came when I ripped my knee open on a piece of metal when I was 12 years old (before I’d joined Arsenal), and that now seems like a massive stroke of luck when I think about it.

I was playing football with my mates on some park land at the back of our house in Northolt. I was stuck in goal and as a ball came across I rushed out for it, quick as you like, sliding across the turf. The council were still building around the estate then, and there was rubble and crap everywhere. A piece of metal wire sticking in the ground snagged the skin on my knee and tore it right down to the bone.

It was touch and go whether I’d play football again. The doctors gave me a Robocop knee with 30 stitches on the inside, another 30 on the outside. With medical science, they pieced me together with catgut, the wire they used in John McEnroe’s tennis rackets. It gave my right leg some kind of super strength. After that I never had to use my left peg, because I could kick the ball so well with the outside of my right thanks to the extra support in my knee. When I was at Villa, our French winger David Ginola said to me, ‘You are zee best I ‘av ever seen at kicking with the outside of your foot, Merz.’ That’s some compliment coming from a great player like David, I can tell you.

As a trainee at Arsenal, I had the odd twisted ankle, a few bruises, but that was it. And then things started happening for me in the youth team. It took about seven months, but as I got bigger I became a regular in the starting line-up. I was scoring goals and playing well, while the lads in the year above me, like Michael Thomas, David Rocastle, Martin Hayes and Tony Adams, started playing in the reserves, knocking on the first-team door. I was offered a second year on my YTS contract and began training with the first team shortly afterwards. It was Big Boy stuff, but I really fancied my chances of getting a proper game. I even dreamt of watching myself on Match of the Day.

Then I made it into the reserve team. Once a youth footballer gets to that stage in his career, it can get pretty brutal. The pressure is really on to get a pro contract. Players are often chasing a place in the first-team squad with another apprentice, someone who could be their best mate. I spent a lot of time worrying whether I was going to make it or not, and it got to me. The panic attacks came back. During a reserve game against Chelsea I latched on to a through ball and rounded their keeper Peter Bonetti, who I’d loved as a kid because I was a Chelsea fan (though Ray Wilkins was my idol). But as I was about to poke it home, I got the fear and froze like a training cone. A defender nicked the ball off me and I was left there, looking like a right wally, feeling sick. A few days later I went to the doctors again, but the GP was like a fish up a tree. He told me to give up football, but I wasn’t going to do that. I loved the game too much.

At training I managed to hold it together, which was a relief because I was playing with some proper superstars. Charlie Nicholas was one of them and he was a god to the Arsenal fans. He’d come down from Celtic, where he’d smashed every goalscoring record going. Graham Rix was there too, as was Tony Woodcock and top England centre-forward Paul Mariner, who was a player and a half. It was a massive deal for me. I remember being on the training ground and thinking, ‘My God, these people are legends.’

The biggest shock was that they were all so normal. None of them were big-time, none of them were Jack-the-lads. It was a help, because I was a normal bloke too. I was determined never to become a flash Harry, which was probably what got me into trouble in the long run, and I could never say no to my mates at home. I’d already smoked weed in the park with them, but I’d packed it in when I signed Don Howe’s YTS contract. I liked it because it relaxed me, but it gave me the munchies. I’d always end the night at the counter of a 24-hour petrol station buying bars of chocolate and packets of crisps, which wasn’t the best for someone with an ambition to make it in the First Division.

I also liked a drink, which was something I was better suited to than grass. I found that the more I drank, the fewer panic attacks I’d have. I started in my early teens, knocking back the Pernod and black with mates, which was always colourful when it came back up. It didn’t put me off, though. If my mum and dad went out on a Saturday night they’d often come back and find me passed out on the sofa, surrounded by a dozen empty cans of lager.

I suppose it was good training. After I’d been working with the first team for a while, Charlie Nicholas and Graham Rix took me under their wing, but this time it was off the pitch as well as on it. They had showed me the ropes at the club and told me how to handle myself during games, and then they invited me to Stringfellows in London, a fancy footballers’ hang-out in the West End. My eyes were on stalks when I walked in for the first time, there were birds everywhere and they all wanted to meet Charlie. He had the long hair, the earring and the leather trousers. He was a football superstar, like George Best had been in the seventies.

‘Fuck, I like this,’ I thought. ‘I want to be like him.’

This was at a time long before Stringfellows became a strip club, but it might as well have been one. The girls were wearing next to nothing and there were bottles of bubbly everywhere. Tears for Fears and Howard Jones blasted out from the speakers. I looked like the character Garth from Wayne’s World because my eyes kept locking on to every passing set of pins like heat-seeking radar, and I couldn’t believe the amount of booze that was flying around. Graham Rix’s bar bill would have put my gambling binge with Wes to shame.

I crashed round at Charlie’s house afterwards, a fancy apartment in Highgate with an open-plan living-room and kitchen, plush furniture, the works. I wanted all of it. Luckily, the club had decided to sign me as a pro, and I couldn’t scribble my name down quick enough because there was nothing more I wanted in the world than to be a professional footballer. And I fancied another night in Stringfellows.

I got my contract on 1 December 1985 and at the time I thought it was big bucks, all £150 of it a week. Oh my God, I thought I’d made it, even though I was earning the same amount of dough as my mates on the building site. That didn’t stop me from celebrating. I remember going round to my girlfriend Lorraine’s house with a bottle of Moët because I reckoned I was on top of the world. The first-team players had given me a sniff of the high life available to a top-drawer footballer, and how could I not be sucked in by the glamour? I’d tasted bubbles with Champagne Charlie before we’d shared half-time oranges.

Arsenal were having a ’mare in 1986. Don resigned after a lorryload of shocking results, and George Graham turned up in May. I was gutted for Don. He was a top coach, one of the best in the world at the time. I worked with him again when he was looking after the England Under-19s, and he was phenomenal, really thorough and full of ideas. When he talked, you listened, but Don’s problem was that he didn’t have it in him to be a manager. Really, he was just too nice.

As a coach he was perfect, a good cop to a manager’s bad cop. If a manager had bollocked the team and torn a strip off someone, I imagine Don would have put his arm around them afterwards. He would have got their head straight.

‘Now don’t you worry about it, son,’ he’d say. ‘The gaffer doesn’t really think you’re a useless, lazy fuckwit, he just reckons you should track back a bit more.’

Being a coach and a manager are two very different jobs. When someone’s a coach they take the lads training, but they don’t have the added pressure of picking the team or running the side, and that makes a massive difference. I don’t think Don could hack that. He wasn’t the only one, there have been loads of great, great coaches who couldn’t do it as a manager. Brian Kidd was a good example. He was figured to be one of the best coaches in the game when he worked alongside Fergie at United. He went to Blackburn as gaffer and took them down.

Our new manager, George Graham, was a mystery to me. I didn’t know him from Adam, apart from the fact that he was an Arsenal boy and he wanted to rule the club in a strict style. I’d heard he’d been a bit casual as a player. Some of the lads reckoned he liked a drink back in the day, and they used to call him Stroller at the club because he seemed so relaxed when he played, but when he turned up at training for the first time he seemed a bit tough to me. Straightaway, George packed me off to Brentford because he thought some first-team football with a lower league club would do me good. Frank McLintock, his old Arsenal mate, was in charge there and George was right, it did help, but only because we got so plastered on the coach journey from away games that some of the players would fall into the club car park when we finally arrived home. It prepared me for a lifetime of boozing.

I signed with Brentford on a Friday afternoon. Twenty-four hours later we played Port Vale, and what an eye-opener that was. To prepare for the game, striker Francis Joseph sat at the back of the bus, smoking a fag. We were comfortably beaten that afternoon and Frank McLintock was sacked on the coach on the way back. I thought, ‘Nice one, the fella who’s signed me has just been given the boot.’ I couldn’t believe it.

After that, though, it was plain sailing. Former Spurs captain Steve Perryman took over the club as player-manager and got us going. We didn’t lose again, and after every game we celebrated hard. I remember we played away at Bolton in a midweek match, and when we got back to the dressing-room at 9.15, a couple of the lads didn’t even get into the baths. They changed and ran out of the dressing-room so they could get to the off-licence before it closed. On the way home we all piled into a couple of crates of lager and got paro. It was a different way of life than at Arsenal. I learnt at Highbury that you could have a drink on the way home, but only if you’d done the business. At Brentford you could have a drink on the way home even if you hadn’t played well.

Going to Brentford back then was probably the best thing that could have happened to me, because it made me appreciate Highbury even more. By looking at Brent-ford I could see that Arsenal was a phenomenal club. The marble halls at Highbury, the atmosphere, the way they looked after you was top, top class. I went everywhere in the world with them during my career. We played football in Malaysia, Miami, Australia and Singapore. When we played in South Africa a few years later, we were presented with a guest of honour before the match, a little black fella with grey hair. When he shook my hand, I nudged our full-back, Nigel Winterburn, who was standing next to me.

‘Who the fuck’s that?’ I said.

Nige couldn’t believe it.

‘Bloody hell, Merse, it’s Nelson Mandela,’ he said. ‘One of the most famous people in the world.’

I’m not being horrible, but I never got that treatment at Aston Villa. They were a big club and we might have gone to Scandinavia for a pre-season tour, or played in the Intertoto Cup, but it was hardly South Africa and a handshake from Nelson Mandela. I never got that at Boro or Pompey either, and I definitely didn’t get that at Brent-ford. A couple of days after the Port Vale game, following my first day training there, I went into the dressing-rooms for a shower and chucked my kit on the floor. Steve Perry-man picked it up and chucked it back at me.

‘What are you doing?’ he said. ‘You’ve got to take that home and wash it.’

I couldn’t believe it. At Arsenal, one of the kids would have done that for me. I’d train, get changed and the next day my kit would be back at the same place in the dressing-room, washed, ironed, folded up and smelling as fresh as Interflora, even though I didn’t have a first-team game under my belt.

I loved it at Brentford and I was so grateful to them for starting my career. I go and watch them whenever I can, but I wasn’t there for long as George soon called me back. Steve had wanted to keep me for a few more months, but I knew that getting recalled to Highbury so quickly meant one thing only. It was debut time.

I was right as well. I made my first appearance against Man City at home on 22 November 1986, coming on as a sub in a 3–0 win. I ran on to the pitch and all the fans were cheering and singing for me. Then with my first touch, a shocker, I put the ball into the North Bank. It was supposed to be a cross. Instead it went into Row Z. The Arsenal fans must have thought, ‘What the fuck have we got here? This guy looks like a right Charlie.’ They didn’t know the half of it.

Lesson 2

Do Not Drink 15 Pints and Crash Your Car into a Lamppost

‘Our teenage sensation drinks himself silly and gets arrested. Tony Adams wets the Merson sofa bed.’

That’s when the boozing really started. Under George, I got to the fringes of the first team at the tail end of the 1986–87 season, and whenever I played at Highbury I’d always go into an Irish boozer around the corner from the ground afterwards. The Bank of Friendship it was called. In those days, my drinking partner was Niall Quinn, who had signed for the club a few years earlier. If you had said to me then when I was 17 or 18, ‘Oh, Niall’s going to be the chairman of Sunderland when he’s 40-odd,’ I’d have thought you were having a laugh. He wasn’t that sort of bloke.

We’d often play games in the stiffs together, which took place in midweek. On the day of a match, we’d spend hours in the bookies before heading back to Niall’s place for a spicy pizza, which was our regular pre-match meal. His house was a bomb site. I’d regularly walk into his living room and see six or seven blokes lying on the floor in sleeping bags.

‘Who the fuck are these, Quinny?’ I’d ask.

‘Oh, I dunno. Just some lads who came over last night from Ireland.’

It was hardly chairman of the board material.

My Arsenal career had started with a few first-team games here, some second-string games there, but word was starting to spread about me. My life in the limelight had begun a season earlier in the 1985 Guinness Six-aSide tournament, which was a midweek event in Manchester for the First Division’s reserve team players and one or two promising kids. I loved it because the highlights were being shown on the telly.

We lost in the final but I was in form and picked up blinding reviews whenever I played. I was performing so well that the TV commentator Tony Gubba started banging on about me, saying I was a great prospect. Then Charlie Nicholas did a newspaper interview and claimed I was going to be the next Ian Rush. Suddenly the Arsenal fans were thinking, ‘This kid must be good.’ Everyone else wanted to know what all the fuss was about.

The only person who wasn’t getting carried away was George. After my debut against City I had to wait until April 1987 before my first full game, and that was a baptism of fire because it was an away game against Wimbledon, or The Crazy Gang as most people liked to call them, they were that loony. In those days they intimidated teams at Plough Lane, their home ground. The dressing-rooms were pokey, and they’d play tricks like swapping the salt for sugar, or leaving logs in the loos, which never flushed properly. It annoyed the big teams like Arsenal who were used to luxury. Then they’d make sure the central heating was on full blast in the away room; that way the opposition always felt knackered before kick-off.

They were pretty hard on the pitch too. Vinnie Jones was their name player then, but Dennis Wise and John Fashanu could cause some damage. To be fair, they sometimes played a bit of football if they fancied it, but that day we won 2–1 in an eventful game. Vinnie got sent off for smashing into Graham Rix, and I scored my first goal for Arsenal, a header. As it was going in, their midfielder Lawrie Sanchez tried to punch it away, but he only managed to push it into the top corner. I thought, ‘The fucking cheek.’

I played in another four games as George eased me into the swing of things, but nobody else was handling me with kid gloves. In the next match I played against Man City again, this time at Maine Road, and when we kicked off I ran to the halfway line. I was watching the ball at the other end when City’s centre-half, Mick McCarthy, smashed me right across the face. He didn’t apologise but instead gave me a look that said, ‘You come fucking near me again and I’ll snap you in half.’

‘No chance of that,’ I thought. I hardly touched the ball afterwards.

George changed everything at Arsenal. In his first season, we won the 1986–87 Littlewoods Cup Final, beating Liverpool, 2–1, though I wasn’t involved in the game. At Wembley, Charlie scored both goals, but because he was a bit of a player in the nightclubs, George didn’t want him around. Three games into the 1987–88 season he was dropped and never played again. George later sold him. I was gutted when I heard the news, because he was such a top bloke to be around. I never saw him turn up for training with the hump. Even when things weren’t going well, or the goals weren’t going in, he always had a smile on his face.

He wasn’t the only one to be shown the door. George could see a lot of the lads were going out on the town, and they weren’t winning anything big, so he decided to make some serious changes. During the 1987–88 season players like David ‘Rocky’ Rocastle, Michael ‘Mickey’ Thomas, Tony Adams and Martin Hayes started to make the first team regularly. I was getting a lot of games too, featuring 17 times and scoring five goals, though over half those appearances came as sub.

Looking back, it was obvious what George was doing. He wanted to be around young players who could be bossed about. He wanted to put his authority on the team. Seasoned pros like Charlie wouldn’t have fallen in line with his ideas, not in the same way as a bunch of wet-behind-the-ears kids.

Full-backs Nigel Winterburn of Wimbledon and Stoke’s Lee Dixon joined the club and were followed in June 1988 by centre-half Steve Bould. Apparently, Lee had been at about 30 clubs, but I’d never heard of him before. The team transformation didn’t end with the defence. He also signed striker Alan ‘Smudger’ Smith from Leicester City. All of a sudden we were a really exciting, young side and everyone was thinking, ‘Bloody hell, this could work.’

We only finished sixth in the League in 1987–88, but the new Arsenal were starting to glue. Rocky, God bless him, was one of the best wingers of his generation. He had everything. He could pass the ball, score goals and take people on. But he was also hard as nails and could really put in a tackle. At the same time he was one of the nicest blokes ever and nobody ever said a bad word about him, which in football was a massive compliment. What a player – he should have played a million times for England and he was Arsenal through and through. When George sold him to Leeds in 1992, he was devastated, it broke his heart. It broke our hearts when he died of cancer in 2001.

We used to call Mickey Thomas ‘Pebbles’, after the gargling baby in The Flintstones, because you could never understand what he was saying, he always mumbled, but he was an unbelievable player. When it came to training, George rarely let us have five-a-side games, maybe on a Friday if we were lucky. When we did play them, he always sent Mickey inside to get changed. Because he was such a good footballer, Mickey would always take the piss out of the rest of us, and George wasn’t having that. Everything had to be done seriously, or there was no point in doing it at all.

Centre-half Steve Bould was the best addition to the first-team squad as far as I was concerned, because along with midfielder Perry Groves, who was signed from Colchester in 1986, he became one of my drinking partners at the club. His main talent, apart from being a professional footballer, was eating. Bloody hell, he could put it away. On the way home from away games, there was always a fancy table service on the coach, complete with two waiters. The squad would have a prawn cocktail to start, or maybe some salmon or a soup. Then there was a choice of a roast dinner or pasta for the main course, with an apple pie as dessert. That was followed up with cheese and biscuits. In the meantime, the team would get stuck into the lagers. If we’d won, I’d always grab a couple of crates from the players’ lounge on the way out.

Bouldy was six foot four and I swear he was hollow. We’d have eating competitions to kill time on the journey and he would win every time. Prawn cocktails, soup, salmon, roast chicken, lasagnes, apple pies, cheese and biscuits – he’d eat the whole menu and then some. Everything was washed down with can after can of lager. By the time the coach pulled into the training ground car park, we’d fall off it. I’d have to call my missus for a lift because I couldn’t drive home, but Bouldy always seemed as fresh as a daisy as he made the journey back to his gaff. He probably stopped for a curry on the way.

George worked us hard, really hard, and training was a nightmare. On Monday, we’d run in the countryside. On Tuesday, we’d run all morning at Highbury until we were sick. We’d do old-school exercises, like sprinting up and down the terraces and giving piggybacks along the North Bank. Modern-day players wouldn’t stand for it, they’d be crying to their agents every day, but George could get away with it because we were young and keen and not earning huge amounts of money. We didn’t have any power.

Still, it was like Groundhog Day and I could have told you, to the drill, what I was doing every single day of the week for the first three months of the 1988-89 season. Most of it was based on the defensive side of the game, George was obsessed by it. We would carry out drills where two teams had to keep possession for as long as possible, then we’d work with eight players keeping the ball against two runners.

In another session, George would set up a back six of John Lukic in goal, Lee Dixon and Nigel Winterburn as full-backs, and Tony and Bouldy as centre-halves, with David O’Leary protecting them in the midfield. A team of 11 players would then try to break them down. They were phenomenal defensively. If we scored more than one goal against them in training, we knew we’d done well. Sometimes George would link the back four with a rope, so when they ran out to catch a striker offside, they would get used to coming out together, arms in the air, shouting at the lino. It wasn’t a fluke that clean sheets were common for us in those days, because George worked so hard to achieve them.

We did the same thing every day, but the lads never moaned. If anyone grumbled they were soon dropped for the next match, and so we worked every morning on not conceding goals without a murmur. Everyone listened to George, because we were all frightened of what he would do if we didn’t live up to his high standards. He was nothing like the laid-back player everyone had heard about.

As a tactician he was brilliant, and his knowledge was scary, but he was even scarier as a bloke. If you didn’t do what he’d said, like getting the ball beyond the first man at a corner, he’d bollock you badly. When George walked into a room, everybody stopped talking, and nobody ever dared to challenge him if they thought what he was doing was wrong or out of order.

Our defender (or defensive midfielder, depending on the line-up) Martin Keown was the only person to have a go at George in all the time I was there. I remember we went to Ipswich and had a nightmare. God knows why the argument started, but it ended up with Martin shouting at George in the dressing-room – giving it, trying to start a ruck.

‘Come on, George!’ he yelled as the lads stared, open-mouthed. ‘Come on!’ He didn’t play for ages after that.

Fans wondered why George didn’t stay around the game much longer than he did, but it’s pretty obvious really – the players wouldn’t stand for his methods of management today. They earn too much money, they wouldn’t have to listen to him. They’d be moaning in the papers and asking for a move as soon as he’d got them giving piggybacks in training.

Wednesdays were great because George always gave the squad a day off. That meant I could get hammered on a Tuesday night, which I did every week. Often I was joined by some of the other lads, like Steve Bould, Tony Adams, Nigel Winterburn and Perry Groves. We’d start off in a local pub, then we’d go into London and drink all over town. We wouldn’t stop until we were paro. The pint-o-meter usually came in at 15 beers plus and we used to call our sessions ‘The Tuesday Club’. George knew about the heavy nights, but I don’t think he cared because we were always right as rain when we arrived for training on Thursday.

Bouldy was always up for a drink in those days, as was Grovesy, but he was a bit lighter than the rest of us. Sometimes he’d even throw his lagers away if he thought we weren’t looking. I remember the night of Grovesy’s first Tuesday Club meeting. It took place during his first week at the club, and we went to a boozer near Highbury. He stood by a big plant as we started sinking the pints, and when we weren’t looking he’d tip his drink into the pot. Grovesy threw away so much beer that by the end of the evening the plant was trying to kiss him. When we went back to training on Thursday, everyone was going on about what a big drinker he was, because he’d been the last man standing.

The following week we went into the same pub and one of the lads stood next to the plant. I think they’d worked out that Grovesy wasn’t the big hitter we’d thought he’d been, and he was right. After three drinks, Grovesey was paro and couldn’t walk. As he staggered around the pub an hour later, he confessed that he’d been chucking his drinks because he was a lightweight. That tag didn’t last long, though. After one season, he’d learnt how to keep up with the rest of us. He joined Arsenal a teetotaller and left a serious drinker.

It wasn’t just Tuesday nights that we’d go for it – I’d take any excuse for a piss-up. My problem came from the fact that I used booze to put my head right, to calm me down or perk me up. When I was a YTS player, drinking stopped the panic attacks, but when I started breaking into the first team, beer maintained the excitement of playing in front of thousands of Arsenal fans.

It’s a massive buzz playing football, especially when everything is new, like when I got my first touches against Man City at Highbury, or that goal at Plough Lane. The adrenaline that came with playing on a Saturday gave me such a rush. And if I scored, it was the best feeling in the world, nothing else came close. The problems started when I realised the buzz was short. I felt flat when I left the pitch, and I’d sit in the dressing-room after a game, thinking, ‘What am I going to do now? I can’t wait until next Saturday.’ And that’s where the drinking came in. It kept my high up.

I should have known better, because before I’d made it into the first team regularly, boozing had already got me into trouble. When I was 18, I got done for drink-driving. It was in the summer of 1986, I went to a place called Wheathampstead with a few people and we rounded the night off in the Rose and Crown, a lovely little boozer near my house. After a lorryload of pints, I decided to drive home, pissed out of my face, though I must have crashed into every other car outside the pub as I reversed from my parking spot. I missed the turning for my house, went into the next road and ploughed into a lamppost, which ended up in someone’s garden.

I panicked. I ran back to the Rose and Crown and sat there with my mates like nothing had happened. My plan was to pretend that the car had been stolen. It wasn’t long before the police arrived and a copper was tapping me on the back.

‘Excuse me, Mr Merson,’ he said. ‘Do you know your car has been crashed into a lamppost which is now in some-one’s garden?’

I played dumb. ‘You’re kidding?’

‘Has it been stolen?’ he asked.

I kept cool. It wasn’t hard, I’d been taking plenty of fluids. ‘Well, it must have been,’ I said, ‘because I’ve been here all night.’

The copper seemed to believe me. He offered to take me to the car, which I knew was in a right state, but just as I was leaving the pub a little old lady shouted out to us. She’d been sat there for ages, watching me.

‘He’s just got in here!’ she shouted. ‘He tried to drive his car home!’

That was it, I was done for and the policeman breathalysed me. In the cells an officer told me I’d been three times over the limit.

‘Shit, is that bad?’ I said.

He shrugged. ‘Yeah,’ he said. ‘But it’s not the worst one we’ve had tonight. We’ve just pulled a guy for being six times over. But he was driving a JCB through St Albans town centre.’

I was banned from driving for 18 months; the club suspended me for two weeks and fined me £350. Like that JCB in St Albans town centre, I was spinning out of control.

George said the same thing to me whenever I got into trouble: ‘Remember who you are. Remember what you are. And remember who you represent.’

That never dropped with me, I never got it. I was just a normal lad. I came from a council estate. My dad was a coal man. My mum worked in a Hoover factory at Hangar Lane. We were normal people and I wanted to live my life as normally as I could. I had the best job in the world, but I still wanted to have a pint with my mates. Along the way, that attitude was my downfall.

The club never really cottoned on that the drinking was starting to become a problem for me. They would never have believed that I was on my way to being a serious alcoholic. I didn’t know either. I thought I was a big hitter in the boozing department and that it was all under control. The first I knew of my alcohol problem was when they told me in the Marchwood rehab centre.

I used to put on weight because of the beer, but the Arsenal coaches never sussed. I’d worked out that when I stood on the club weights and the doc took his measurements, I could literally hold the weight off if I lent at the right angle or nudged the scales in the right way. The lads used to give me grief all the time. They used to point at my love handles and say I was pregnant, and when George walked past me in the dressing-room I’d suck my tummy in to hide the bulge. I could never have worn the silly skin-tight shirts they wear now, my gut was that bad.

People outside the club would see me drinking, and George would get letters of complaint, but I used to brush them aside when he read them out to me.

‘Paul Merson was in so and so bar in Islington,’ he’d read, sitting behind his desk, waving the letters around. ‘He was drunk and a disgrace to Arsenal Football Club.’

I’d make out they were from Tottenham fans. Then, when I got a letter banging on about how I’d been spotted drunk in town when I’d really been away with the club on a winter break, I was made up. I knew from then on I had proof that there were liars making stuff up about me. I blamed them for every letter to the club after that, even though most of them were telling the truth.

I wasn’t the only one causing aggro, my team-mates were having a right old go, too. In 1989, the year we won the title, I bought a fancy, new, one-bedroom house in Sandridge, near St Albans. It was lovely, fitted with brand-new furniture. I loved it, I was proud of my new home.

Tony Adams was one of my first guests, but he outstayed his welcome. In April 1989 we played Man United away, drew 1–1 and Tone got two goals, one for us and a blinding own goal for them. He fancied a drink afterwards, like he always did in those days, but time was running out as the coach crawled back to London at a snail’s pace and we knew the pubs would be kicking out soon. That wasn’t going to stop him, though.

‘We’re not going to get back till nearly 11, Merse,’ he said. ‘Can I stay at yours and we’ll have a few?’

I was up for it. I never needed an excuse for a drink, but at that stage in the campaign, we’d been under a hell of a lot of pressure. We’d started the season on fire, and even though we weren’t a worldy side (nowhere near as good as the team that won the title in 1991), at one stage we were top of the First Division by 15 points. Then it all went pear. We’d drawn too many matches against the likes of QPR, Millwall and Charlton. Shaky defeats at Forest and Coventry had put massive dents in our championship hopes. After leading the title race for the first half of the season our form had dropped big-time and Liverpool were hot on our heels. That night I wanted to let off steam.

I knew I could get a lock-in at the Rose and Crown. I called up my missus and asked her to make up our fancy brand-new sofa bed for Tone when we got back. Once the team coach pulled up at the training ground, we got into Tone’s car and drove to the pub.

We finished our last pint at four in the morning. Tone gave me a lift back to the house and nearly killed us twice, before parking in the street at some stupid angle. I crept inside, not wanting to wake Lorraine, put Tone to bed and crashed out. When I woke up later, Lorraine was standing over me with a copy of the Daily Mirror in her hand.

‘Look at what they’ve done to him!’ she said, showing me the back page.

Some smart-arse editor had drawn comedy donkey ears on a photo of Tone. Underneath was the headline, ‘Eeyore Adams’. And all because he’d scored an own goal. He’d got one for us too, but that didn’t seem to matter.

‘What a nightmare,’ I said.

‘Are you going to tell him?’

‘Bollocks am I, let him find out when he’s filling up at the petrol station.’

I could hear Tone getting his stuff together downstairs. Then he shouted out to us, ‘See you later, Merse! Thanks for letting me stay, Lorraine!’

When I heard the front door go, I knew we were off the hook. Lorraine got up to sort the sofa bed out so we could watch the telly, and I got up to make a cup of tea. Then Lorraine started shouting. ‘He’s pissed the bed!’

I looked over to see her pointing at a wet patch on our brand-new furniture. I was furious. I grabbed the paper and chased down the street after Tone as he pulled away in his car.

‘You donkey, Adams!’ I shouted. ‘You’re a fucking donkey!’

Lesson 3

Do Not Cross Gorgeous George

‘Because hell hath no fury like a gaffer scorned.’

After Tone’s bed-wetting incident and the 1–1 draw with Man United, Arsenal started to fly again. We beat Ever-ton, Newcastle and Boro and spanked Norwich 5–0. The only moody result was a 2–1 away defeat at Derby County which allowed Liverpool to leapfrog us in the League with one game to go. Along the way, I got us some important goals. There was an equaliser in a 2–2 draw against Wimbledon in the last home game of the season which kept us in the chase for the League, but my favourite was a strike against Everton in the 3–1 win at Goodison Park. I got on to the end of a long ball over the top and banged it home. When it flew past their keeper, Neville Southall, I ran up to the Arsenal fans, hanging on to the cage that separated the terraces from the pitch.

I loved celebrating with the Arsenal crowd. It was a completely different atmosphere at football matches back then. There was a real edge to the games. Remember, this was a time before the Hillsborough disaster and the Taylor Report and there were hardly any seats in football grounds. Well, not when you compare them with today’s fancy stadiums. The fans swayed about and the grounds had an unbelievable atmosphere. I loved it when there were terraces. Football hooliganism was a real problem back then, though. It could get a bit naughty sometimes.

I’d always learn through mates and fans when there was going to be trouble in the ground. If Arsenal were playing Chelsea at Highbury, I’d always hear whispers that their lot would be planning on taking the North Bank in a mass ruck. The players would talk about it in the dressing-room before games, and whenever there was a throw-in or a break in the play, I’d look up at the stands, just to see if it was kicking off.

You could have a bit of fun with the supporters in those days, and we often laughed and joked with them during the games. If ever we were playing away and the home lot were hurling insults at us, we’d give it back when the ref wasn’t looking. It happened off the pitch as well, but sometimes we went too far.

I remember when Arsenal played Chelsea at Stamford Bridge in 1993. After the game a group of their fans started chucking abuse at our team bus, they were even banging on the windows. I was sat at the back, waiting for Steve Bould’s eating competition to kick off, when all of a sudden our striker, Ian Wright, started to make wanker signs over the top of the seats. All the fans could see was his hand through the back window, waving away. They couldn’t believe it.

I nearly pissed myself laughing as the coach pulled off, but I wasn’t so happy when we suddenly stopped a hundred yards down the road. The traffic lights had turned red and Chelsea’s mob were right on top of the bus. They were throwing stuff at the windows, lobbing bottles and stones towards Wrighty’s seat. All I could think was, ‘Oh God, please don’t let them get on, they’ll kill us.’ Luckily the lights changed quickly enough for us to pull away unhurt. I don’t think anyone had a pop at the fans for quite a while after that.

All of a sudden, I was in the big time and so were Arsenal. By the time the 1988–89 season was in full swing, my name was everywhere and I had a big reputation. George had made me a regular in his team and I’d started 35 games, scoring 14 times as centre-forward. I did so well I was awarded the PFA Young Player of the Year. I even had nicknames – the Highbury crowd called me ‘Merse’ or ‘The Magic Man’. There was probably some less flattering stuff as well, but I didn’t pay any attention to that.

With our defeat at Derby and draw against Wimbledon, and Liverpool’s 5–1 win over West Ham, the title boiled down to the last game of the season, an away game at Anfield on Friday 26 May. Liverpool were top of the table by three points, we were second. Fair play to them, they’d been brilliant all year and hadn’t lost a game since 1 January. We still had a chance, though. We knew that if we did them by two goals at Anfield, we’d pinch it on goal difference.

Anfield was the ultimate place to play as a footballer back then. Before a Saturday game at Liverpool, probably around 1.30, the away team would go on to the pitch to have a walk around. George liked us to check out the surface and soak up the atmosphere on away days. Anfield was always buzzing because the Kop was packed from lunchtime. They’d sing ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’, wave their scarves, and surge backwards and forwards, side to side, like they were all on a nightmare ferry crossing to France. It always made me double nervous.

‘Oh shit,’ I’d think. ‘Here we go.’

Weirdly, I wasn’t nervous when we played them at their place on the last day of the 1988–89 season, mainly because nobody had given us a cat-in-hell’s chance of winning the League. Nobody won by two goals at Anfield in those days. Before the game, my attitude was, ‘No way, mate. It ain’t happening.’

The game had become a title decider because of the Hillsborough disaster. It had originally been scheduled for April, but after the FA Cup semi-final between Liverpool and Forest at Sheffield Wednesday’s ground, where 96 Liverpool fans were crushed to death in the stands before kick-off, it was postponed until the end of May, after the final. Liverpool got through against Forest and won the FA Cup, beating Everton of all teams 3–2, not that any Everton fan would begrudge them after all that. Now it was up to us to stop them from doing the double.

I could understand the faffing about with the fixtures, because Hillsborough was one of the worst things I’d ever seen in football. In 1985, I’d watched the Heysel Stadium disaster on the telly. It made me feel sick. I’d turned on the telly hoping to see the European Cup Final between Liverpool and Juventus, but instead I watched as bodies were being carried out. A riot had kicked off, and as fans tried to escape the trouble a wall collapsed on them. Hills-borough was just as bad. I was supposed to pick up my PFA Young Player of the Year Award at a fancy ceremony on the day that it happened, but after seeing the tragedy on the news, I really wasn’t interested. Everything seemed insignificant after all those deaths.

The fixture change pushed us together on the last day of the season in a grand finale. Because the odds were stacked against us and everyone was writing Arsenal off, it had become a free game for the lads, a bonus ball on the calendar. In our heads, we knew George had turned the team around after Don had resigned. Considering Arsenal hadn’t won the League for ages, coming second in the old First Division in 1989 would have been considered a massive achievement by everyone, even though we’d been top for ages before falling away. We were still a young side, discovering our potential, and there was no shame in being runners-up behind an awesome Liverpool team that included legends like Ian Rush, John Aldridge, John Barnes, Peter Beardsley and Steve McMahon. It would have been phenomenal really.

George still pumped us full of confidence. During the week before the game he banged on about how good we were and how we could beat Liverpool. He planned everything as meticulously as he planned his appearance, which was always immaculate. We went up to Merseyside on the morning of the game that Friday, because George wanted to cut out the nerves that would have built up overnight if the team had stayed together. We got into our hotel in Liverpool’s town centre at midday, ate lunch together and then went to our rooms for a three-hour kip.

I never roomed with anyone in those days, because nobody would share with me. The main reason was that I could never get to sleep. I was too excitable and that always drove the other lads mad. Nobody wanted to deal with my messing around before a big game, but in the end I got to enjoy my own privacy. The great thing about having a room to myself was that I could wax the dolphin whenever I wanted.

At five-thirty we all went downstairs for the tactical meeting and some tea and toast. George lifted up a white board and named the team: John Lukic in goal; a back five of Lee Dixon, Nigel Winterburn, Tone and Bouldy, with David O’Leary acting as a sweeper. All very continental. I was in midfield with Rocky, Mickey and Kevin Richardson. Alan Smith was playing up front on his own. George told us who was picking up who at set-pieces, and then he told us how to win the game.

‘Listen, don’t go out there and try to score two goals in the first 20 minutes,’ he said. ‘Keep it tight in the first half, because if they score first, we’ll have to get three or four goals at Anfield and that’s next to impossible. Get in at half-time with the game nil-nil.

‘In the second half, you’ll go out and score. Then, with 15 minutes to go, I’ll change the team around, they’ll shit themselves, you’ll have a right old go, score again and win the game 2–0. OK?’

Everyone looked at each other with their jaws open. Remember, Liverpool hadn’t lost since New Year’s Day. I turned round to Bouldy and said, ‘Is he on what I’m on here?’

None of us believed it was going to happen, not in a million years, but we really should have had more faith in George. He was one of those managers who had so much football knowledge it was scary. People said he was lucky during his career, but George made his own luck. Things happened for him because he worked for it. He was always saying stuff like, ‘Fail to prepare, prepare to fail.’ He’d read big books like The Art of War. I couldn’t understand any of it.

When we kicked off, I thought George had lost the plot. In the first half, Liverpool passed us to death. I touched the ball twice and we never looked like scoring. They never looked like scoring either, but they didn’t have to. A 0–0 draw would have won them the title, so they were probably made up at half-time. The really weird thing was, George was made up as well.

‘Great stuff, lads,’ he said. ‘Brilliant, perfect. Absolutely outstanding. The plan’s going perfectly.’

I couldn’t make it out. George was never happy at half-time. We could have been beating Barcelona 100–0 and he’d still be angry about something. I turned round to Mickey.

‘You touched it yet?’ I said.

He shrugged his shoulders. Everyone was looking at the gaffer in disbelief.

Then we went out and scored, just like George had reckoned we would. It came from a free-kick. The ball was whipped in and Alan Smith claimed he got his head to it. I wasn’t sure whether it had come off his nose, but I couldn’t have cared less – we were 1–0 up. It could have been even better, because moments later Mickey was bearing down on Bruce Grobbelaar’s goal, one-on-one. In those days, you had to have some neck to win 2–0 at Anfield. Often the Kop would virtually blow the ball out of the net. It must have freaked Mickey out because he fluffed it. All I could think was, ‘Shit, we’ve blown the League.’

Then it was game over, well, for me anyway. George took me off and brought on winger Martin Hayes, pushing him up front. Then he pulled off Bouldy and switched to 4-4-2 by replacing him with Grovesy, an extra midfielder. This was where Liverpool were supposed to shit themselves, but I was the one who was terrified. I had to watch the closing minutes like every other fan.

We were playing injury time. Their England midfielder, Steve McMahon was running around, wagging his finger and telling the Liverpool lot we only had a minute left to play. Winger John Barnes won the ball down by the corner flag in our half. He was one of the best English players I’d ever seen, but God knows what he was doing that night. All he had to do was hang on to possession and run down the clock, but for some reason he tried to cut inside his man. Nigel Winterburn nicked the ball off him and rolled it back to John Lukic who gave it a big lump down field. There was a flick on, and suddenly Mickey was one-on-one with Grobbelaar again.

This time, he dinked the ball over him. It was one of the best goals I’d ever seen, one of those chips the South Americans call ‘The Falling Leaf’ – where a player pops the ball over an advancing keeper. It was never going to be easy for Mickey to chip someone like Grobbelaar, especially after missing a sitter earlier in the game, and he had a thousand years to think about what he was going to do as he pelted towards goal – talk about pressure. Mickey kept his head and his goal snatched a famous 2–0 victory and the League title.

When I think about it, that’s probably one of the most famous games ever. Even if you supported someone like Halifax, Rochdale or Aldershot at that time, you’d still remember that match, especially the moment when commentator Brian Moore screamed, ‘It’s up for grabs now!’ on the telly, or the image of Steve McMahon wagging his finger, giving it the big one. Afterwards he was sat on his arse. He looked gutted.

It was extra special for Arsenal. We hadn’t won the League for 18 years and the Kop later applauded us off the pitch. It was a nice touch. Liverpool were the best team in the land at that time. They probably figured another title would turn up at their place, sooner rather than later.

The celebrations started straight after the game. I cracked open a bottle of beer with Bouldy in the dressing-room, still in my muddy Arsenal kit. After that, we got paro on the coach home and ended up in a Cockfosters nightclub until silly o’clock. There was an open-topped bus parade on the Sunday, but everything is a blur to me. The next thing I remember it was breakfast time on Tuesday morning. I was trying to get my keys into my front door, waking up the whole street. I still haven’t got a clue what happened in those 72 hours or so in between. These days, whenever a 22-year-old comes up to me and asks for an autograph, the same thought flashes through my mind: ‘Oh, for fuck’s sake, please don’t call me Dad.’

The lads at the club called me ‘Son of George’ because they reckoned I got away with murder. They were probably right. I certainly didn’t get bollocked as much by the manager as the others, even though I was probably the most badly behaved player in the squad. For some reason, George really took a shine to me.

I remember one time when we went to a summer tournament in Miami in 1990. It was a bloody nightmare. The weather was so hot we had to train at 8.30 in the morning. One day, I stood on the sidelines, yawning, scratching my cods, when George jogged over and looked at my hand. It was halfway down my shorts.

‘You all right, Merse?’

‘Yeah, I’m fine,’ I said.

George put his arm around my shoulder. ‘No, no, you sit down, son,’ he said, thinking I’d pulled a groin muscle.

He was worried I might have overdone it in training, but the only thing I’d been overdoing was a little dolphin waxing in my hotel room.

‘Sit out this session, and don’t worry about it,’ he said.

I could see what the rest of the lads were thinking as I lazed around on the sidelines, and it wasn’t complimentary. Moments later, Grovesy and Bouldy started rubbing their own wedding tackles, groaning, hoping they’d get some of the same treatment, but George was having none of it.

That was how it was with me and George, he was good as gold all the time. He always told me up-front when I wasn’t playing, whether that was because he was dropping me or resting me. He knew I couldn’t physically cope with playing five games on the bounce because I’d be knackered. He liked to rest me every now and then, but he always gave me a heads-up. With the other lads, George wouldn’t announce the news until he’d named the team in the Friday tactical meeting. It would come as a shock to them and that was always a nightmare, because the whole squad would make noises and pull faces. George would always pull me to one side on Thursday, so I could tell the lads myself, as if I’d made the decision. He’d never let me roast.

As I went more and more off the rails throughout my Arsenal career, he must have given me a million chances. God knows why. After my run-ins with the law and the drink-driving charge, word got around the club about my problems, and George started to get fed up with the drinking stories as they started to happen more regularly. I was forever in his office for a lecture. If I’d been caught drinking again or misbehaving, he would remind me of my responsibilities, but he’d never threaten to kick me out of the club or sell me, even though I was high maintenance off the pitch.

I was saved by the fact that I never had any problems training. No matter how paro I’d got the night before, I rarely had a hangover the next morning, I was lucky. I could always tell when some players had been drinking by the way they acted in practice games – they couldn’t hack it. Me, I could always get up and play. I didn’t enjoy it, but I could get through the day, and George knew that come Saturday I’d be as good as gold for him.

Well, most of the time. In some games I played while still pissed from the previous night. In 1991 we faced Luton Town away on Boxing Day. On Christmas Day, the players had their lunches at home with the families, then we met up at Highbury for training. Afterwards, we piled on to the coach to the team hotel and I knocked back pints and pints and pints in the bar. I couldn’t help it, it was Christmas and I was in the mood. The next day, I was still hammered. During the game, a long ball came over and I chased after it. As I got within a few yards I tripped over my own feet, even though there wasn’t a soul near me. I could hear everyone in the crowd laughing and jeering. I couldn’t look towards the bench.

Even though I was Son of George, the manager would always bollock me really hard whenever he caught me drinking. I was even the first player ever to be banned from Arsenal when I caused a lorryload of trouble at an official dinner and dance event for the club at London’s Grosvenor House Hotel. The ban was only for two weeks in 1989, but it caused one hell of a stink all the same.

I was hitting the booze pretty hard that night, and this was a fancy do with dinner jackets, a big meal, and loads of beers flying around. I got smashed big-time, drinking at the bar and having a right old laugh. I was so loud that my shouting drowned out the hired comedian, Norman Collier, who was entertaining the club’s guests – including wives, directors and VIP big shots. People turned round and stared at me as I knocked back drink after drink. George and the Arsenal board were taking note.

Later, a big punch-up kicked off in the car park outside the hotel and somehow I was in the thick of it. To this day I still don’t know what happened, because I was so paro. The papers got to hear about the scuffle, and so did the fans. The next day, George told me to sort myself out and not to come back for a couple of weeks. I wasn’t even allowed to train and being shut out scared me.

I spent a fortnight lying low, trying to convince myself that I’d get back on the straight and narrow. For a while it worked. When I came back I was as good as gold, then I started downing the beers again. The Tuesday Club was into the swing of things and I was back on the slippery slope.

I got worse, and whenever I messed up and George found out, he would do me. On New Year’s Day in 1990, we were playing Crystal Palace at Selhurst Park. I was told I wasn’t in the team.

‘Nice one,’ I thought. ‘It’s New Year’s Eve and I’m in a fancy hotel with the rest of the team, let’s get paro.’

I figured being dropped was a green light for me to go out for a drink and a party. This time, I got so smashed I couldn’t even get up in the morning. George found out and named me as sub for the match just to teach me a lesson. When I fell asleep on the bench during the game, he brought me on for the last 10 minutes to give me another slap. I couldn’t do a thing – I was like a fish up a tree. I couldn’t control the ball and I felt sick every time I sprinted down the wing. We won 4–1, but after that night George vowed never to name a team on New Year’s Eve again. On a normal Saturday he would have got away with it, because I’d have behaved, but I was becoming an alcoholic and it was New Year’s Eve. It had been a recipe for disaster.

Lesson 4

Do Not Shit on David Seaman’s Balcony

‘More boozy disasters for our football dynamo; Perry Groves nearly drowns.’

Oh my God, Gus Caesar was as hard as nails. When he played in the Arsenal defence he always had a ricket in his locker and the fans sometimes got on his back a little bit because he made the odd cock-up, but what he lacked in technique he definitely made up for in physique. He was the muscliest footballer I’d ever seen. I reckon he could have killed someone with a Bruce Lee-style one-inch punch if he wanted. A lot of the time, I got the impression he was just waiting for an excuse to try it out on me. I had a habit of rubbing him up the wrong way.

It all kicked off with me and Gus in 1989, when Arsenal took the players away to Bermuda for a team holiday. The whole squad went to a nightclub and got on the beers one night, messing around, having a laugh. All of a sudden Gus started shouting at me. A drunken argument over nothing, a spilt pint maybe, had got out of hand. A scuffle broke out – handbags stuff, really – and Gus poked me in the eye just as the pair of us were being separated.

It bloody hurt and I was proper angry, but because I wasn’t much of a fighter I knew that poking Gus back would have been stupid. He would have torn me limb from limb. I reckoned on a better way to get my own back, so I let the commotion calm down, staggering away, bellyaching, checking to see if I was permanently blind. Then Bouldy and me went back to the hotel, leaving everyone behind. We walked up to reception, casual as you like, and blagged the key to Gus’s door. It was party time, I was going to cause some serious damage to his room.