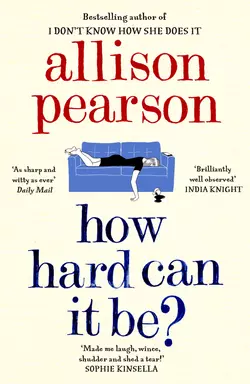

How Hard Can It Be?

How Hard Can It Be?

Allison Pearson

Kate Reddy is counting down the days until she is fifty, but not in a good way.Fifty, in Kate’s mind, equals invisibility, and she’s caught between her traitorous hormones, unknowable teenage children and ailing parents.She’s back at work after a break, now that her husband Rich has dropped out of the rat race to master the art of mindfulness. But just as Kate is finding a few tricks to get by, her old client and flame Jack reappears – complicated doesn’t even begin to cover it…

Copyright (#ulink_0ad0f96b-2a72-5e3a-9670-98305f08be52)

The Borough Press

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Copyright © Allison Pearson 2017

Cover design by Claire Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Hand lettering by Ruth Rowland. Cover illustration by Henn Kim

Allison Pearson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Source ISBN: 9780008150556

Ebook Edition © May 2018 ISBN: 9780008150549

Version: 2018-03-22

Praise for How Hard Can It Be? (#ulink_0a0638f7-e4a3-5869-aa16-b74e92fd5e46)

‘Revolutionary … Both funny and unflinching’

ELIZABETH DAY, Daily Telegraph

‘Once again, countless women will recognise themselves … Pearson has a gift’

The Times

‘Zesty, razor-sharp and hilarious … Get ready for Kate!’

TINA BROWN, magazine editor and bestselling author

‘Sharply observed and very funny’

Woman & Home

‘Made me laugh, wince, shudder and shed a tear!’

SOPHIE KINSELLA

‘As sharp and witty as ever … hugely enjoyable’

Daily Mail

‘Funny, heart-breaking, wise and delightful’

SOPHIE HANNAH

‘How Hard Can It Be? is that rare thing: a sequel that matches and even surpasses the original’

Daily Telegraph

‘Brilliantly well observed’

INDIA KNIGHT

‘Pearson deftly balances despair-inducing observations with escapist pizzazz’

Mail on Sunday

‘Pearson makes a sharp point about the lack of value and status that society places on the onerous job of a stay at home mother … in these pages, there is a raw honesty’

Financial Times

‘Sparkling, funny and poignant, this is a triumphant return for Pearson and hopefully not the last we will hear of Kate’

Daily Express

‘A cutting edge of its own’

Metro

‘Wildly entertaining’

Reader’s Digest

‘[Pearson] nails the comedy and the pathos of daily domestic life like no one else’

Country Life

‘Poignant and smart takes on the pressures affecting working mothers … laugh out loud funny’

Women’s Agenda

‘[Peason writes] with acid and a daunting determination to tell it like it is’

New Zealand Herald

Dedication (#ulink_10d9c04a-9318-52ae-9a2a-f896e4969ed9)

For Awen and Evie,

my mother and my daughter

Epigraph (#ulink_10d9c04a-9318-52ae-9a2a-f896e4969ed9)

Conceal me what I am, and by my aid

For such disguise as haply shall become

The form of my intent.

William Shakespeare, Twelfth Night

Nobody tells you about the balding pudenda.

Whoopi Goldberg

Contents

Cover (#ucf7a6c42-569f-5421-9638-87e69fd92f5f)

Title Page (#u343c1de5-c45d-5a9e-9c7b-c3d8fa6d7312)

Copyright (#uc7a39da7-2baa-5d5c-8df0-6f150aa4e665)

Praise (#u3d16ba53-2809-5bd4-b7e2-a8b269051e95)

Dedication (#ue88133f8-40e2-52b5-b12b-fd629d2362ef)

Epigraph (#uffe8321d-3a41-5ce4-ab24-ecda437ac99a)

Prologue: Countdown to Invisibility: T minus six months and two days (#ua92c7fbc-75ec-5e35-bc0e-0593a1def1c9)

1. Bats in the Belfie (#u02b281bc-f673-532e-bdbd-8b0cc5288ef1)

2. The Has-been (#uea2ad9a5-6f2c-502e-a3d8-731f32fba2c8)

3. The Bottom Line (#ub04d491a-faaa-5619-89c8-090984fe0d24)

4. Ghosts (#ufc34d1e1-e3c4-56ae-9029-02db33be0351)

5. Five More Minutes (#ue5ad5165-e9a1-5073-aba9-d0210178d368)

6. Of Mice and Menopause (#litres_trial_promo)

7. Back to the Future (#litres_trial_promo)

8. Old and New (#litres_trial_promo)

9. Genuine Fake (#litres_trial_promo)

10. Rebirth of a Saleswoman (#litres_trial_promo)

11. Twelfth Night (or What You Won’t) (#litres_trial_promo)

12. Catch-32 (#litres_trial_promo)

13. Those Stubborn Areas (#litres_trial_promo)

14. The College Reunion (#litres_trial_promo)

15. Calamity Girl (#litres_trial_promo)

16. Help! (#litres_trial_promo)

17. The Rock Widow (#litres_trial_promo)

18. The Office Party (#litres_trial_promo)

19. Coitus Interruptus (#litres_trial_promo)

20. Merry Christmas (#litres_trial_promo)

21. The Mere Idea of You (#litres_trial_promo)

22. Madonna and Mum (#litres_trial_promo)

23. Never Can Say Goodbye (#litres_trial_promo)

24. For Whom the Belfie Tolls (#litres_trial_promo)

25. Cut to the Quick (#litres_trial_promo)

26. Redemption (#litres_trial_promo)

27. Guilty Secret (#litres_trial_promo)

28. 11

March (#litres_trial_promo)

29. After All (#litres_trial_promo)

Footnotes (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Allison Pearson (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PROLOGUE (#ulink_9d6dd4ec-9a1f-5b84-aacb-6051318a7640)

COUNTDOWN TO INVISIBILITY: T MINUS SIX MONTHS AND TWO DAYS (#ulink_9d6dd4ec-9a1f-5b84-aacb-6051318a7640)

Funny thing is I never worried about getting older. Youth had not been so kind to me that I minded the loss of it. I thought women who lied about their age were shallow and deluded, but I was not without vanity. I could see the dermatologists were right when they said that a cheap aqueous cream was just as good as those youth elixirs in their fancy packaging, but I bought the expensive moisturiser anyway. Call it insurance. I was a competent woman of substance and I simply wanted to look good for my age, that’s all – what that age was didn’t really matter. At least that’s what I told myself. And then I got older.

Look, I’ve studied the financial markets half my life. That’s my job. I know the deal: my sexual currency was going down and facing total collapse unless I did something to shore it up. The once-proud and not unattractive Kate Reddy Inc was fighting a hostile takeover of her mojo. To make matters worse, this fact was rubbed in my face every day by the emerging market in the messiest room in the house. My teenage daughter’s womanly stock was rising while mine was declining. This was exactly as Mother Nature intended, and I took pride in my gorgeous girl, I really did. But sometimes that loss could be painful – excruciatingly so. Like the morning I locked eyes on the Circle Line with some guy with luxuriant, tousled Roger Federer hair (is there any better kind?) and I swear there was a flicker of something between us, a sizzle of static, a frisson of flirtation right before he offered me his seat. Not his number, his seat.

‘Totes humil’, as Emily would say. The fact he didn’t even consider me worthy of interest stung like a slapped cheek. Unfortunately, the impassioned young woman who lives on inside me, who actually thought Roger was flirting with her, still doesn’t get it. She sees her former self in the mirror of her mind’s eye as she looks out at the world and assumes that’s what the world sees when it looks back. She is quite insanely and irrationally hopeful that she might be attractive to Roger (likely age: thirty-one) because she doesn’t realise that she/we now have a thickening waist, thinning vaginal walls (who knew?) and are starting to think about spring bulbs and comfortable footwear with considerably more enthusiasm than, say, the latest scratchy thongs from Agent Provocateur. Roger’s erotic radar could probably detect the presence of those practical, flesh-coloured pants of mine.

Look, I was doing OK. Really, I was. I got through the oil-spill-on-the-road that is turning forty. Lost a little control, but I drove into the skid just like the driving instructors tell you to and afterwards things were fine again; no, they were better than fine. The holy trinity of midlife – good husband, nice home, great kids – was mine.

Then, in no particular order, my husband lost his job and tuned into his inner Dalai Lama. He would not be earning anything for two years, as he retrained as a counsellor (oh, joy!). The kids entered the twister of adolescence at exactly the same time as their grandparents were taking what might charitably be called a second pass at their own childhood. My mother-in-law bought a chainsaw with a stolen credit card (not as funny as it sounds). After recovering from a heart attack, my own mum lost her footing and broke her hip. I worried I was losing my mind; but it was probably just hiding in the same place as the car keys and the reading glasses and the earring. And those concert tickets.

In March it’s my fiftieth. No, I will not be celebrating with a party and yes, I probably am scared to admit I am scared, or apprehensive (I’m not quite sure what I am, but I definitely don’t like it.) To be perfectly honest, I’d rather not think about my age at all, but significant birthdays – the kind they helpfully put in huge, embossed numbers on the front of cards to signpost The Road to Death – have a way of forcing the issue. They say that fifty is the new forty, but to the world of work, my kind of work anyway, fifty may as well be sixty or seventy or eighty. As a matter of urgency, I need to get younger, not older. It’s a question of survival: to get a job, to hold onto my position in the world, to remain marketable and within my sell-by date. To keep the ship afloat, the show on the road. To meet the needs of those who seem to need me more than ever, I must reverse time, or at least get the bitch to stand still.

With this goal in mind, the build-up to my half-century will be quiet and totally uneventful. I will not show any outward sign of the panic I feel. I will glide towards it serenely, no more sudden swerves or bumps in the road.

Well, that was the plan. Then Emily woke me up.

1 (#ulink_6e39665d-49f3-54d2-8668-45fde7d1b069)

BATS IN THE BELFIE (#ulink_6e39665d-49f3-54d2-8668-45fde7d1b069)

SEPTEMBER

Monday, 1.37 am: Such a weird dream. Emily is crying, she’s really upset. Something about a belfry. A boy wants to come round to our house because of her belfry. She keeps saying she’s sorry, it was a mistake, she didn’t mean to do it. Strange. Most of my nightmares lately feature me on my unmentionable birthday having become totally invisible and talking to people who can’t hear me or see me.

‘But we haven’t got a belfry,’ I say, and the moment I speak the words aloud I know that I’m awake.

Emily is by my side of the bed, bent over as if in prayer or protecting a wound. ‘Please don’t tell Daddy,’ she pleads. ‘You can’t tell him, Mummy.’

‘What? Tell him what?’

I fumble blindly on the bedside table and my baffled hand finds reading glasses, distance glasses, a pot of moisturiser and three foil sheets of pills before I locate my phone. Its small window of milky, metallic light reveals that my daughter is dressed in the Victoria’s Secret candy-pink shorty shorts and camisole I foolishly agreed to buy her after one of our horrible rows.

‘What is it, Em? Don’t tell Daddy what?’

No need to look over to check that Richard’s still asleep. I can hear that he’s asleep. With every year of our marriage, my husband’s snoring has got louder. What began as piglet snufflings twenty years ago is now a nightly Hog Symphony, complete with wind section. Sometimes, at the snore’s crescendo, it gets so loud that Rich wakes himself up with a start, rolls over and starts the symphony’s first movement again. Otherwise, he is harder to wake than a saint on a tomb.

Richard had the same talent for Selective Nocturnal Deafness when Emily was a baby, so it was me who got up two or three times in the night to respond to her cries, locate her blankie, change her nappy, soothe and settle her, only for that penitential playlet to begin all over again. Maternal sonar doesn’t come with an off-switch, worse luck.

‘Mum,’ Emily pleads, clutching my wrist.

I feel drugged. I am drugged. I took an antihistamine before bed because I’ve been waking up most nights between two and three, bathed in sweat, and it helps me sleep through. The pill did its work all too well, and now a thought, any thought at all, struggles to break the surface of dense, clotted sleep. No part of me wants to move. I feel like my limbs are being pressed down on the bed by weights.

‘Muuuu-uuuumm, please.’

God, I am too old for this.

‘Sorry, give me a minute, love. Just coming.’

I get out of bed onto stiff, protesting feet and put one hand around my daughter’s slender frame. With the other, I check her forehead. No temperature, but her face is damp with tears. So many tears that they have dripped onto her camisole. I feel its humid wetness – a mix of warm skin and sadness – through my cotton nightie and I flinch. In the darkness, I plant a kiss on Em’s forehead and get her nose instead. Emily is taller than me now. Each time I see her it takes a few seconds to adjust to this incredible fact. I want her to be taller than me, because in the world of woman, tall is good, leggy is good, but I also want her to be four years old and really small so I can pick her up and make a safe world for her in my arms.

‘Is it your period, darling?’

She shakes her head and I smell my conditioner on her hair, the expensive one I specifically told her not to use.

‘No, I did something really ba-aa-aa-aad. He says he’s coming here.’ Emily starts crying again.

‘Don’t worry, sweetheart. It’s OK,’ I say, manoeuvring us both awkwardly towards the door, guided by the chink of light from the landing. ‘Whatever it is, we can fix it, I promise. It’ll be fine.’

And, you know, I really thought it would be fine, because what could be so bad in the life of a teenage girl that her mother couldn’t make it better?

2.11 am: ‘You sent. A picture. Of your naked bottom. To a boy. Or boys. You’ve never met?’

Emily nods miserably. She sits in her place at the kitchen table, clutching her phone in one hand and a Simpsons D’oh mug of hot milk in the other, while I inhale green tea and wish it were Scotch. Or cyanide. Think, Kate, THINK.

The problem is I don’t even understand what it is I don’t understand. Emily may as well be talking in a foreign language. I mean, I’m on Facebook, I’m in a family group on WhatsApp that the kids set up for us and I’ve tweeted all of eight times (once, embarrassingly, about Pasha on Strictly Come Dancing after a couple of glasses of wine), but the rest of social media has passed me by. Until now, my ignorance has been funny – a family joke, something the kids could tease me about. ‘Are you from the past?’ That was the punchline Emily and Ben would chorus in a sing-song Irish lilt; they had learned it from a favourite sitcom. ‘Are you from the past, Mum?’

They simply could not believe it when, for years, I remained stubbornly loyal to my first mobile: a small, greyish-green object that shuddered in my pocket like a baby gerbil. It could barely send a text message – not that I ever imagined I would be sending those on an hourly basis – and you had to hold down a number to get a letter to appear. Three letters allocated to each number. It took twenty minutes to type ‘Hello’. The screen was the size of a thumbnail and you only needed to charge it once a week. Mum’s Flintstone Phone, that’s what the kids called it. I was happy to collude with their mockery; it made me feel momentarily light-hearted, like the relaxed, laid-back parent I knew I never really could be. I suppose I was proud that these beings I had given life to, recently so small and helpless, had become so enviably proficient, such experts in this new tongue that was Mandarin to me. I probably thought it was a harmless way for Emily and Ben to feel superior to their control-freak(ish) mother, who was still boss when it came to all the important things like safety and decency, right?

Wrong. Boy, did I get that wrong. In the half hour we have been sitting at the kitchen table, Emily, through hiccups of shock, has managed to tell me that she sent a picture of her bare backside to her friend Lizzy Knowles on Snapchat because Lizzy told Em that the girls in their group were all going to compare tan-lines after the summer holidays.

‘What’s a Snapchat?’

‘Mum, it’s like a photo that disappears after like ten seconds.’

‘Great, it’s gone. So what’s the problem?’

‘Lizzy took a screenshot of the Snapchat and she said she meant to put it in our Facebook Group Chat, but she put it on her wall by mistake so now it’s there like forever.’ She pronounces the word ‘forever’ so it rhymes with her favourite, ‘Whatevah’ – lately further abbreviated to the intolerable ‘Whatevs’.

‘Fu’evah,’ Emily says again. At the thought of this unwanted immortality, her mouth collapses into an anguished ‘O’ – a popped balloon of grief.

It takes a few moments for me to translate what she has said into English. I may be wrong (and I’m hoping I am), but I think it means that my beloved daughter has taken a photo of her own bare bum. Through the magic of social media and the wickedness of another girl, this image has now been disseminated – if that’s the word I want, which I’m very much afraid it is – to everyone in the school, the street, the universe. Everyone, in fact, but her own father, who is upstairs snoring for England.

‘People think it’s like really funny,’ Emily says, ‘because my back is still a bit burnt from Greece so it’s like really red and my bum’s like really white so I look like a flag. Lizzy says she tried to delete it, but loads of people have shared it already.’

‘Slow down, slow down, sweetheart. When did this happen?’

‘It was like seven thirty but I didn’t notice for ages. You told me to put my phone away when we were having dinner, remember? My name was at the top of the screenshot so everyone knows it’s me. Lizzy says she’s tried to take it down but it’s gone viral. And Lizzy’s like, “Em, I thought it was funny. I’m so sorry.” And I don’t want to seem like I’m upset about it because everyone thinks it’s really hilarious. But now all these people have got my like Facebook and I’m getting these creepy messages.’ All of that comes out in one big sobbing blurt.

I get up and go to the counter to fetch some kitchen roll for Em to blow her nose because I have stopped buying tissues as part of recent family budget cuts. The chill wind of austerity blowing across the country, and specifically through our household, means that fancy pastel boxes of paper softened with aloe vera are off the shopping list. I silently curse Richard’s decision to use being made redundant by his architecture firm as ‘an opportunity to retrain in something more meaningful’ – or ‘something more unpaid and self-indulgent’ if you were being harsh, which, sorry, but I am at this precise moment because I don’t have any Kleenex to soak up our daughter’s tears. Only when I make a mess of ripping the kitchen paper along its serrated edge do I notice that my hand is shaking, quite badly actually. I place the trembling right hand in my left hand and interlink the fingers in a way I haven’t done for years. ‘Here is the church. Here is the steeple. Look inside and see all the people.’ Em used to make me do that little rhyme over and over because she loved to see the fingers waggling in the church.

‘’Gain, Mummy. Do it ’gain.’

What was she then? Three? Four? It seems so near yet, at the same time, impossibly far. My baby. I’m still trying to get my bearings in this strange new country my child has taken me to, but the feelings won’t stay still. Disbelief, disgust, a tincture of fear.

‘Sharing a picture of your bottom on a phone? Oh, Emily, how could you be so bloody stupid?’ (That’s the fear flaring into anger right there.)

She trumpets her nose on the kitchen roll, screws up the paper and hands it back to me.

‘It’s a belfie, Mum.’

‘What’s a belfie for heaven’s sake?’

‘It’s a selfie of your bum,’ Emily says. She talks as though this were a normal part of life, like a loaf of bread or a bar of soap.

‘You know, a BELFIE.’ She says it louder this time, like an Englishman abroad raising his voice so the dumb foreigner will understand.

Ah, a belfie, not a belfry. In my dream, I thought she said belfry. A selfie I know about. Once, when my phone flipped to selfie mode and I found myself looking at my own face, I recoiled. It was unnatural. I sympathised with that tribe which refused to be photographed for fear the camera would steal their souls. I know girls like Em constantly take selfies. But a belfie?

‘Rihanna does it. Kim Kardashian. Everyone does it,’ Emily says flatly, a familiar note of sullenness creeping into her voice.

This is my daughter’s stock response lately. Getting into a nightclub with fake ID? ‘Don’t be shocked, Mum, everyone does it.’ Sleeping over at the house of a ‘best friend’ I’ve never met, whose parents seem weirdly unconcerned about their child’s nocturnal movements? Perfectly normal behaviour, apparently. Whatever it is I am so preposterously objecting to, I need to chill out, basically, because Everyone Does It. Am I so out of touch that distributing pictures of one’s naked arse has become socially acceptable?

‘Emily, stop texting, will you? Give me that phone. You’re in enough trouble as it is.’ I snatch the wretched thing out of her hands and she lunges across the table to grab it back, but not before I see a message from someone called Tyler: ‘Ur ass is well fit make me big lol!!!

’

Christ, the Village Idiot is talking dirty to my baby. And ‘Ur’ instead of ‘Your’? The boy is not just lewd but illiterate. My Inner Grammarian clutches her pearls and shudders. Come off it, Kate. What kind of warped avoidance strategy is this? Some drooling lout is sending your sixteen-year-old daughter pornographic texts and you’re worried about his spelling?

‘Look, darling, I think I’d better call Lizzy’s mum to talk about wha—’

‘Nooooooo.’ Emily’s howl is so piercing that Lenny springs from his basket and starts barking to see off whoever has hurt her.

‘You can’t,’ she wails. ‘Lizzy’s my best friend. You can’t get her in trouble.’

I look at her swollen face, the bottom lip raw and bloody from chewing. Does she really think Lizzy is her best friend? Manipulative little witch more like. I haven’t trusted Lizzy Knowles since the time she announced to Emily that she was allowed to take two friends to see Justin Bieber at the O2 for her birthday. Emily was so excited; then Lizzy broke the news that she was first reserve. I bought Em a ticket for the concert myself, at catastrophic expense, to protect her from that slow haemorrhage of exclusion, that internal bleed of self-confidence which only girls can do to girls. Boys are such amateurs when it comes to spite.

All of this I think, but do not say. For my daughter cannot be expected to deal with public humiliation and private treachery in the same night.

‘Lenny, back in your basket, there’s a good boy. It’s not getting up time yet. Lie down. There, good boy. Good boy.’

I settle and reassure the dog – this feels more manageable than settling and reassuring the girl – and Emily comes across and lies next to him, burying her head in his neck. With a complete lack of self-consciousness, she sticks her bottom in the air. The pink Victoria’s Secret shorts offer no more cover than a thong and I get the double full-moon effect of both bum cheeks – that same pert little posterior which, God help us, is now preserved for posterity in a billion pixels. Emily’s body may be that of a young woman, but she has the total trustingness of the child she was not long ago. Still is in so many ways. Here we are, Em and me, safe in our kitchen, warmed by a cranky old Aga, cuddled up to our beloved dog, yet outside these walls forces have been unleashed that are beyond our control. How am I supposed to protect her from things I can’t see or hear? Tell me that. Lenny is just delighted that the two girls in his life are up at this late hour; he turns his head and starts to lick Em’s ear with his long, startlingly pink tongue.

The puppy, purchase of which was strictly forbidden by Richard, is my proxy third child, also strictly forbidden by Richard. (The two, I admit, are not unrelated.) I brought this jumble of soft limbs and big brown eyes homejust after we moved into this ancient, crumbling-down house. A little light incontinence could hardly hurt the place, I reasoned. The carpets we inherited from the previous owners were filthy and sent up smoke signals of dust as you walked across a room. They would have to be replaced, though only after the kitchen and the bathroom and all the other things that needed replacing first. I knew Rich would be pissed off for the reasons above, but I didn’t care. The house move had been unsettling for all of us and Ben had been begging for a puppy for so long – he’d sent me birthday cards every single year featuring a sequence of adorable, beseeching hounds. And now that he was old enough not to want his mother to hug him, I figured out that Ben would cuddle the puppy and I would cuddle the puppy, and, somehow, somewhere in the middle, I would get to touch my son.

The strategy was a bit fluffy and not fully formed, rather like the new arrival, but it worked beautifully. Whatever the opposite of a punchbag is, that’s Lenny’s role in our family. He soaks up all the children’s cares. To a teenager, whose daily lot is to discover how unlovable and misshapen they are, the dog’s gift is complete and uncomplicated adoration. And I love Lenny too, really love him with such a tender devotion I am embarrassed to admit it. He probably fills some gap in my life I don’t even want to think about.

‘Lizzy said it was an accident,’ says Em, stretching out a hand for me to pull her up. ‘The belfie was only supposed to be for the girls in our group, but she like posted it where all of her other friends could see it by mistake. She took it down as soon as she realised, but it was too late ’cos loads of people had already saved it and reposted it.’

‘What about that boy you said was coming round? Um, Tyler?’ I close and open my eyes quickly to wipe the boy’s lewd text.

‘He saw it on Facebook. Lizzy tagged my bum #FlagBum and now everyone on Facebook can see it and knows it’s like mine, so now everyone thinks I’m like just one of those girls who takes her clothes off for nothing.’

‘No they don’t, love.’ I pull Em into my arms. She lays her head on my shoulder and we stand in the middle of the kitchen, half hugging, half slow-dancing. ‘People will talk about it for a day or two then it’ll blow over, you’ll see.’

I want to believe that, I really do. But it’s like an infectious disease, isn’t it? Immunologists would have a field day researching the viral spread of compromising photographs on social media. I’d venture that the Spanish flu and Ebola combined couldn’t touch the speed of photographic mortification spreading through cyberspace.

Through the virus that is Internet porn, and in the blink of an eye, my little girl’s bare backside had found its way from our commuter village forty-seven miles outside London all the way to Elephant and Castle where Tyler, who is what police call ‘a known associate’ of Lizzy’s cousin’s mate’s brother, was able to see it. All because, according to Em, dear Lizzy had her settings fixed to allow ‘friends of friends’ to see whatever she posted. Great, why not just send it directly to the paedophile wing of Wormwood Scrubs?

4.19 am: Emily is asleep at last. Outside, it’s black and cold, the first chill of early autumn. I’m still getting used to night in a village – so different from night in a town, where it’s never truly dark. Not like this furry black pelt thrown over everything. Quite close by, somewhere down the bottom of the garden, there is the shriek of something killing or being killed. When we first moved here, I mistook these noises for a human in pain and I wanted to call the police. Now I just assume it’s the fox again.

I promised Em I would stay by her bed in case Tyler or any other belfie hounds try to drop in. That’s why I’m sitting here in her little chair with the teddy bear upholstery, my own mottled, forty-something backside struggling to squidge between its narrow, scratched wooden arms. I think of all the times I’ve kept vigil on this chair. Praying she would go to sleep (pretty much every single night, 1998–2000). Praying she would wake up (suspected concussion after falling off bouncy castle, 2004). And now here I am thinking of her bottom, the one that I trapped expertly in Pampers and which is now bouncing around the worldwide web all by itself, no doubt inflaming the loins of hordes of deviant Tylers. Uch.

I feel ashamed that my daughter has no sense of modesty because whose fault is that? Her mother’s, obviously. Mine – Emily’s Grandma Jean – instilled in me an almost Victorian dread of nakedness that came from her own strict Baptist upbringing. Ours was the only family on the beach that got changed into swimwear inside a kind of towelling burqa, with a drawstring neck my mum had fashioned from curtain flex. To this day, I hardly glance at my own backside, let alone offer it up to public view. How in the name of God did our family go, in just two generations, from prudery to porn?

I desperately need to talk to someone, but who? I can’t tell Richard because the thought of his princess being defiled would kill him. I flick through my mental Rolodex of friends, pausing at certain names, trying to weigh up who would judge harshly, who would sympathise effusively then spread the gossip anyway – in a spirit of deep concern, naturally. (‘Poor Kate, you won’t believe what her daughter did.’) It’s not like laughing with other mums about something embarrassing Emily did when she was little, like that Nativity play when she broke Arabella’s halo because she was so cross about getting the part of the innkeeper’s wife. (A dowdy, non-speaking role with no tinsel; I saw her point.) I can’t expose Em to the sanctimony of the Muffia, that organised gang of mothers superior. So, who on earth can I trust with this thing so distressing and surreal that I actually feel sick? I go to my Inbox, find a name that spells ‘unshockability’ and begin to type.

From: Kate Reddy

To: Candy Stratton

Subject: Help!

Hi hon, you still up? Can’t remember the time difference. It’s been quite a night here. Emily was lured by a ‘friend’ into posting a photo of her naked derrière on Snapchat which has now been circulated to the entire Internet. This is called a ‘belfie’, which I’m old enough to think might be short for Harry Belafonte. Worried that heavy-breathing stalkers are about to form a queue outside our house. Seriously, I feel Jurassic when she talks to me. I don’t understand any of the tech stuff, but I do know it’s really bad. I want to murder the little idiot and I want to protect her so badly.

I thought this parenting lark was supposed to get easier. What do I do? Ban her from social media? Get her to a nunnery?

Yours in a sobbing heap,

Kx

A Technicolor image pings into my head of Candy at Edwin Morgan Forster, the international investment company where we both worked, must be eight or nine years ago. She was wearing a red dress so tight you could watch the sashimi she ate for lunch progressing down her oesophagus. ‘Whad you lookin’ at, kid?’ she would jeer at any male colleague foolish enough to comment on her Jessica Rabbit silhouette. Candace Marlene Stratton: proud, foul-mouthed export of New Jersey, Internet whizz, and my bosom buddy in an office where sexism was the air that we breathed. I read about a discrimination case in the paper the other day, some junior accountant complaining that her boss hadn’t been respectful enough in his use of language. I thought: Seriously? You don’t know you’re born, sweetie. At EMF, if a woman so much as raised her voice, the traders would yell across the floor, ‘On the rag are you, darling?’ Nothing was off limits, not even menstruation. They loved to tease female staff about their time of the month. Complaining would only have confirmed the sniggerers’ view that we couldn’t hack it, so we never bothered. Candy, who subsisted on coke back then – the kind you gulped from a can and the kind you snorted up your nose – sat about fifteen feet away from me for three years, yet we hardly spoke. Two women talking in the office was ‘gossiping’; two men doing exactly the same was ‘a briefing’. We knew the rules. But Candy and I emailed the whole time, in and out of each other’s minds, venting and joking: members of the Resistance in a country of men.

I never thought I would look back on that time with affection, let alone longing, only suddenly I think how exciting it was. It tested me in a way that nagging kids to do their homework, cooking nine meals a week and getting a man in to do the gutters – the wearisome warp and weft of life – never does. Can you be a success as a mother? People only notice when you’re not doing it right.

Back then, I had targets I could hit and I knew that I was good, really good at my work. Camaraderie under pressure; you don’t realise what a deep pleasure that is until it’s gone. And Candy, she always had my back. Not long after she gave birth to Seymour, she headed home to the States to be near her mom, who longed to babysit her first grandchild. It allowed Candy to start an upmarket sex-toy business. Orgazma: for the woman who’s too busy going to come (or maybe the other way around). I’ve only seen Candy once in the years since we both left EMF, although, forged in the heat of adversity, ours are the ties that bind. I really wish she was here now. I’m not sure I can do this by myself.

From: Candy Stratton

To: Kate Reddy

Subject: Help!

Hey Sobbing Heap, this is the Westchester County 24-Hour Counselling Service. Calm down, OK. What Emily did is perfectly normal teen behaviour. Think of it as the 21

century equivalent of love letters tied with a red ribbon in a scented drawer … only now it’s her drawers.

Count yourself lucky it’s just a picture of her ass. A girl in Seymour’s class shared a picture of her lady garden because the captain of the football team asked to see it. These kids have NO sense of privacy. They think because they’re on the phone or computer in their own home it’s safe.

Emily doesn’t realise she’s walking butt-naked down the information superhighway looking like she’s got her thumb out and she’s trying to hitch a ride. Your job is to point that out to her. With force if necessary. I suggest hiring some friendly nerd to see how much he can track down online and destroy. You can ask Facebook to take obscene stuff down I’m pretty sure. And restrict her privileges – no Internet access for a few weeks until she’s learned her lesson.

You should get some sleep, hon, must be crazy late there?

Am here for you always,

XXO C

5.35 am: It’s now so late that it’s early. I decide to unload the dishwasher rather than go back to bed for a futile hour staring at the ceiling. This perimenopause thing is playing havoc with my sleep. You won’t believe it, but when the doctor mentioned that word to me a few months ago the first thing that popped into my head was a Sixties band with moptop hair: Perry and the Menopauses. Dooby-dooby-doo. Perry was smiling, unthreatening, and almost certainly wearing a hand-knitted Christmas jumper. I know, I know, but I’d never heard of it before and I was relieved to finally have a name for a condition that was giving me broken nights then plunging me down a mineshaft of tiredness straight after lunch. (I’d vaguely wondered if I had some fatal illness and had already moved on to touching scenes by the graveside where both kids cried and said if only they’d appreciated me while I was still alive.) If you have a name for what’s making you scared you can try to befriend it, can’t you? So Perry and I, we would be friends.

‘I can’t afford to take an afternoon nap,’ I explained to the doctor. ‘I’d just like to feel like my old self again.’

‘That’s not uncommon,’ she said, typing busily into my notes on the screen. ‘Classic textbook symptoms for your age.’

I was relieved to have classic symptoms; there was safety in numbers. Out there were thousands, no, millions of women who also walked around feeling like they were strapped to a dying animal. All we wanted was our old self back, and if we waited patiently for her she would come. Meanwhile, we could make lists to combat another of Perry’s delightful symptoms. Forgetfulness.

What did Candy say in her email? Find some nerdy guy who can track down Emily’s belfie and wipe it? ‘Perfectly normal teen behaviour.’ Maybe it’s not so bad after all. I take a seat in the chair next to the Aga, the one I bought on eBay for £95 (absolute bargain, it only needs new springs, new feet and new upholstery) and start to make a list of all the things I mustn’t forget. The last thing I remember is a dog with no sense of his own size jumping onto my lap, his tail beating against my arm, silky head resting on my shoulder.

7.01 am: The moment I wake I check my phone. Two missed calls from Julie. My sister likes to keep me up to date on our mother’s latest adventure, just to make it clear that, living three streets away in our Northern home town, it’s she who has to be on call for Mum, who has so far refused to adopt any behaviour which might be called ‘age appropriate’. Every Wednesday morning, Mum prepares all the vegetables for Luncheon Club, where some of the diners who she calls ‘the old people’ are fifteen years her junior. This fills me with a mixture of pride (look at her spirit!) and exasperation (stop being so bloody independent, will you?). When is my mother going to accept that she too is old?

Since I decided to ‘swan off’ as my sister calls it – aka taking the difficult decision to move the family back down South so I could be near London, the place most likely to give me a well-paid job – Julie has become one of the great English martyrs, giving off a noxious whiff of bonfire and sanctimony. Never misses a chance to point out I’m not pulling my weight. Even though, when I speak to Mum, as I do most days, she tells me that she hasn’t seen my younger sister for ages. I think it’s terrible Julie doesn’t drop in to check on Mum, seeing how near she is, but I can’t say so because, in the casting for the play of our family, I am the Bad Daughter Who Buggered Off and Julie is the Unappreciated Good Daughter Who Stayed Put. I do my best to change the script; I bought Mum a computer for her birthday and told her it was from both of us, Julie and me. But making me feel guilty is one of the few bits of power my twice-divorced, vodka-chugging sister gets to wield in her hard and helpless life. I get that. Rationally, I do, and I try to be understanding, but since when could the power of reason unpick the knots of sibling rivalry? I should call Julie back, and I will, but I need to get Emily sorted out. Emily first, then Mum, then prepare for my interview with the headhunter this afternoon. Anyway, I don’t need Julie’s help to make me feel guilty about getting my priorities wrong. Guilt is where I live.

7.11 am: At breakfast, I tell Richard that Emily is sleeping in because she had a bad night. This has the virtue of being a lie that is perfectly true. It was certainly bad, right up there with the worst nights ever. Completely drained, I move through my morning tasks like a rusty, scrapyard android. Even bending over to pick up Lenny’s water bowl is such an effort I actually make encouraging sounds to get myself to straighten up. (‘Come on, ooff, you can do it!’) Am making porridge when Ben descends from his lair looking like a wildebeest tethered to three kinds of electronic device. When he turned fourteen, my lovely boy’s shoulders slumped overnight and he lost the power of speech, communicating his needs in occasional grunts and snide put-downs. This morning, however, he seems weirdly animated – talkative even.

‘Mum, guess what? I saw this picture of Emily on Facebook. Crack-ing photo.’

‘Ben.’

‘Seriously, the bottom line is she got thousands of Likes for this picture of her …’

‘BENJAMIN!’

‘Well, well, young man,’ says Richard, looking up briefly from his frogspawn yogurt, or whatever it is he’s eating these days, ‘it’s good to hear you saying something positive about your sister for a change. Isn’t it, Kate?’

I shoot Ben my best Medusa death-ray stare and mouth, ‘Tell Dad and you’re dead.’

Richard doesn’t notice this frantic semaphore between mother and son because he is absorbed in an article on a cycling website. I can read the headline over his shoulder. ‘15 Gadgets You Never Knew You Needed.’

The number of gadgets cyclists don’t know that they need is very extensive, as our small utility room can testify. Getting to the washing machine these days is like competing in the hurdles because Rich’s bike gear occupies every inch of floor. There are several kinds of helmet: a helmet that plays music, a helmet with a miner’s lamp clipped to the front, even a helmet with its own indicator. From my drying rack hang two heavy, metal locks that look more like implements used during the torture of a Tudor nobleman than something to fasten a bike to a railing. When I went in there yesterday to empty the dryer, I found Rich’s latest purchase. A worryingly phallic object, still in its box, it claimed to be ‘an automatic lube dispenser’. Is that for the bike or for my husband’s chafed backside, which has lost its cushion of fat since he became a mountain goat? It sure as hell isn’t for our sex life.

‘I’ll be late tonight. Andy and I are riding to Outer Mongolia,’ (at least that’s what I think he said). ‘OK with you?’

It’s a statement not a question. Richard doesn’t look up from his laptop, not even when I put a bowl of porridge in front of him. ‘Darling, you know I’m not eating gluten,’ he mutters.

‘I thought oats were OK? Slow release, low GI aren’t they?’ He doesn’t respond.

Same goes for Ben who I can see is scrolling through Facebook, smirking and communing with that invisible world where he spends so much of his time. Probably charting the global adventures of his sister’s bottom. With a pang, I think of Emily asleep upstairs. I told her everything would seem better in the morning and now it is the morning I need to think how to make it better. First, I have to get her father out of the house.

Over by the back door, Richard starts to put on his cycling gear, a process fraught with zips and studs and flaps. Picture, if you will, a knight getting ready for the Battle of Agincourt with a £2,300 carbon fibre bike taking the part of the horse. When my husband took up cycling three years ago, I was totally in favour. Exercise, fresh air, anything so I could be left in peace on eBay picking up ‘more junk we don’t need to clutter up this ruin’, as Richard calls it. Or ‘incredible bargains that will find a place in our magical old house’, which I prefer.

That was before it became clear that Rich wasn’t just cycling for fun. Seriously, fun did not come into it. Before my unsuspecting eyes, he morphed into one of those MAMILs you read about in the Lifestyle section of the papers, a Middle-Aged Man in Lycra who did a minimum of ten hours in the saddle every week. On his new regime, Rich rapidly lost two stone. I found it hard to be delighted about this because my own extra pounds were clinging to me with greater tenacity every year. Unlike Richard’s saddlebags, mine were no longer removable (if only you could unhook the panniers of spare flesh!). Until my late thirties, I swear all it took was four days of eating only cottage cheese and Ryvita and I could feel my ribs again. That trick doesn’t work any more.

Rich had never been fat, but he was always cuddly in a rumpled, Jeff Bridges kind of way, and there was something about the soft ampleness of his body that matched his good nature. He looked like what he was: an amiable and generous man. This angular stranger he studies in the mirror with intense interest has a taut, toned body and a heavily lined face – we have both reached that age where being too thin makes you look gaunt instead of youthful. The new Richard attracts lots of admiring comments from our friends and I know I should find him attractive, but any lustful thoughts are punctured instantly by the cycling gear. What Rich most resembles when he wears his neck-to-knee stretchwear is a giant turquoise condom. Horribly visible, his penis and testicles dangle like low-hanging fruit.

The old Rich would have appreciated how ridiculous he looks and enjoyed sharing the joke. This new one doesn’t smile much, or maybe I don’t give him much to smile about. He is permanently in a grump about the house or ‘Your Money Pit’ as he calls it, never missing an opportunity to get in a dig at the lovely builder who is skilfully helping me coax the sad old place back to life.

As he fastens his helmet, he says: ‘Kate, can you get Piotr to take a look at the bathroom tap? I think the washer he used was another of his post-war Polish cast-offs.’

See what I mean? Another sideswipe at poor Piotr. I would say something sarcastic back, like how I’m amazed that Richard even noticed something about our house when his mind is on much higher things, but suddenly feel really bad that I haven’t told him about Emily and the belfie. Instead of snapping, I go over and give him a guilty goodbye hug, whereupon my dressing gown gets snagged on a Velcro pocket flap. There are an awkward few seconds when we are stuck together. It’s the closest we’ve been for a while. Perhaps I should tell him about last night? The temptation to blurt it all out, to share the burden, is almost overwhelming, but I promised Emily that I wouldn’t tell Daddy, so I don’t.

7.54 am: With Richard and Ben safely out of the house, I go upstairs to check on Em, bearing a mug of brick-red tea with one sugar. Since she started her juicing regime, she won’t allow any sugar to pass her lips, but surely sweet tea counts as medicine in an emergency? I can only push her door so far before it jams on a pile of clothes and shoes. I squeeze through the gap and find myself in what looks like a room vacated in a hurry after an air raid. Debris is spread over a wide area and on the bedside table teeters an art installation made of Diet Coke cans.

The state of a teenager’s bedroom is such a time-honoured source of mother–daughter conflict that I guess I should have been prepared for it, but our fights over this disputed territory are never less than bruising. The latest, after school on Friday, when I insisted that her room be tidied right now, ended in furious stalemate:

Emily: ‘But it’s my room.’

Me: ‘But it’s my house.’

Neither of us was prepared to back down.

‘She’s so stubborn,’ I complained later to Richard.

‘Who does that remind you of?’ he said.

Emily is sprawled diagonally across the bed, duvet twisted about her like a chrysalis. She has always been a very active sleeper, moving around her mattress like the hands of a clock. When she’s asleep, as she is now, she looks exactly like the toddler I remember in her cot – that determined jut to her chin, the flaxen hair which forms damp curls on the pillow when she’s hot. She was born with these enormous eyes whose colour didn’t settle for a long while, as if they were still making up their mind. When I lifted her out of the cot each morning, I used to chant, ‘What colour are your eyes today? Browny bluey greeny grey?’

They ended up hazel like mine and I was secretly disappointed she didn’t get Richard’s perfect shade of Paul Newman blue, though she carries the gene for those so they may yet come out in her own kids. Unbelievably, my mind has already started straying to grandchildren. (I knew you could be broody for a baby, but broody for your baby’s baby? Is that a thing?)

I can tell Emily is dreaming. There’s a movie running behind those busy, fluttering eyelids; hope it’s not a horror film. Lying on the pillow next to her head are Baa-Sheep, her first toy, and the damn phone, its screen lit up with overnight activity. ‘37 unread messages,’ it says. I shudder to think what they contain. Candy told me I should confiscate Emily’s mobile, but when I reach out to take it her legs twitch in protest like a laboratory frog’s. Sleeping Beauty ain’t going to give up her online life without a struggle.

‘Emily, sweetheart, you need to wake up. Time to get ready for school.’

As she groans and turns over, burrowing deeper into her chrysalis, the phone dings once, then again and again. It’s like a lift door opening every few seconds.

‘Em, love, please wake up. I’ve brought you some tea.’

Ding. Ding. Ding. Hateful sound. Emily’s innocent mistake started this and who knows where it will end. I snatch the phone and put it in my pocket before she can see. Ding. Ding.

On the way downstairs, I pause on the landing. Ding. Looking through the ancient mullioned window onto a still-misty garden a line of poetry comes, absurdly, alarmingly, into my head. ‘Send not to know for whom the belfie tolls. It tolls for thee.’

8.19 am: In the kitchen, or what passes for one while Piotr is building an actual kitchen, I quickly post the breakfast stuff into the dishwasher and open a tin for Lenny before checking my emails. The first one I see is from a name that has never previously bothered my Inbox. Oh, hell.

From: Jean Reddy

To: Kate Reddy

Subject: Surprise!

Dear Kath,

It’s Mum here. My first email ever! Thank you so much for clubbing together with Julie to buy me a laptop computer. You girls do spoil me. I’ve started a computing class at the library.

The Internet seems very interesting so far. Lots of funny cat pictures. Am really looking forward to keeping up with all the grandchildren. Emily told me she is on a thing called Facebook. Please can you give me her address?

Love Mum xxxx

So yesterday, I Googled ‘Perimenopause’. If you’re thinking of doing it, one word of advice. Don’t.

Symptoms of Perimenopause:

Hot flushes, night sweats and/or clammy feeling

Palpitations

Dry and itchy skin

Irritability!!!

Headaches, possibly worsening migraines

Mood swings, sudden tears

Loss of confidence, feelings of low self-worth

Trouble sleeping through the night

Irregular periods; shorter, heavier periods, flooding

Loss of libido

Vaginal dryness

Crashing fatigue

Feelings of dread, apprehension, doom

Difficulty concentrating, disorientation, mental confusion

Disturbing memory lapses

Incontinence, especially upon sneezing or laughing

Aching, sore joints, muscles and tendons

Gastrointestinal distress, indigestion, flatulence, nausea

Weight gain

Hair loss or thinning (head, pubic, or whole body); increase in facial hair

Depression

What does that leave? Oh, right. Death. I think they forgot death.

2 (#ulink_f9ea3e82-5e60-5ad3-b6d1-55d79c9e224d)

THE HAS-BEEN (#ulink_f9ea3e82-5e60-5ad3-b6d1-55d79c9e224d)

I made Emily go to school the day after the night her bottom went viral. Maybe you think I was wrong. Maybe I agree with you. She didn’t want to, she pleaded, she came up with every reason under the sun why it would be better if she stayed home with Lenny and caught up on some ‘homework’ (binge-watching Girls, I’m not that stupid). She even offered to tidy her room – a clear sign of desperation – but it felt like one of those times when you have to stick to your guns and insist that the child does what feels hardest. Get back in the saddle, isn’t that the phrase our parents’ generation used before making your child do something they don’t want to became socially unacceptable.

I told myself it would be better for Em to run the gauntlet of crude jokes and smirking whispers in the corridors than throw a sickie and hide her dread under the duvet at home. Just as when the seven-year-old Emily came off her bike in the park, the gravel cruelly embedded in her scraped and bloody knee, and I knelt before her and sucked the tiny stones out of the wound before insisting that she got back on again in case the instinctive aversion to trying what has just hurt you were to bloom into an unconquerable fear.

‘NO, Daddy, NO!’ she screamed, appealing over my head to Richard who, by then, had already bagged the softer, more empathetic parent role, leaving me to be the enforcer of manners, bedtimes and green vegetables – tedious stuff lovely, tickly daddies don’t care to get involved with. I hated Rich for obliging me to become the kind of person I had never wanted to be and would, in other circumstances, have paid good money to avoid. But the moulds of our parental roles, cast when our kids are really quite small, set and harden without our noticing until one day you wake up and you are no longer just wearing the mask of a bossy, multi-tasking nag. The mask has eaten into your face.

Come to think of it, you can probably date everything that went wrong with modern civilisation to the moment parent became a verb. Parenting is now a full-time job, in addition to your other job, the one that pays the mortgage and the bills. There are days when I think I would love to have been a mother in the era when parents were still adults who selfishly got on with their own lives and drank cocktails in the evening while children did their best to please and fit in. By the time it was my turn, it was the other way around. Did this vast army of men and women dedicated to the hour-by-hour comfort and stimulation of their offspring cause unprecedented joy in the younger generation? Well, read the papers and make up your own mind. But this was our story, Emily’s and mine, Richard’s and Ben’s, and I can only tell you what it felt like to live it from the inside. History will pass its own verdict on whether modern parenting was a science or a fearful neurosis that filled the gap once occupied by religion.

Yes, I made Emily go to school that day, and I nearly made myself late for my interview because I drove her there, instead of making her ride her bike. I remember the way she walked through the gate, head and shoulders down as if braced against a gale, although there was no wind, none at all. She turned for a second and gave a brave little wave and I waved back and gave her a thumbs-up, although my heart felt like a crushed can inside my chest. I almost wound down the window and called after her to come back, but I thought that, as the adult, I needed to give my child confidence, not show that I, too, was anxious and freaked out.

Did it start then? Was that the root of the terrible thing that happened later? If I’d played things differently, if I’d let Em stay home, if I’d cancelled the interview and we’d both snuggled under the duvet, watched four episodes of Girls back to back and let the caustic, jubilant wit of Lena Dunham purge a sixteen-year-old’s fearful shame? So many ifs I could have heeded.

Sorry, I didn’t. I had to find a job urgently. I reckoned there was enough money in the joint account to last us three months, four at most. The lump of money we put by after selling the London house for a profit and moving up North had shrunk alarmingly, first when Richard lost his job, then after the move back South when we rented for a while until we found the right place. One Sunday lunchtime, Richard casually revealed that not only would he be earning next to nothing for two years but also that, as part of his counsellor training, he was now in therapy himself twice a week, for which we would have to pay. The fees were monstrous, maiming: I felt like ringing the therapist and offering her a potted history of my husband in return for a fifty per cent discount. Who knew every quirk and wrinkle of his personality better than I did? The fact Rich was spending our food-shopping money on sessions where he got to complain about me only fuelled my sense of injustice. To make up the difference, I needed a serious, main-breadwinner position, and I needed it fast or we would be homeless and dining on KFC. So, I made my daughter get back in the saddle, just as I took myself back to work when she was four months old and had a streaming cold, the phlegm bubbling in her tiny lungs. Because that’s the deal, that’s what we have to do. Even when every atom of our being is shrieking, ‘Wrong, Wrong, Wrong’? Even then.

10.12 am: On the train to London, I’m supposed to be going through my CV and reading the financial pages in preparation for my meeting with the headhunter, but all I can think about is Emily, and Tyler’s foul, disgusting message to her. What does it feel like to be the object of such salivating lust before you’ve even lost your virginity? (At least I assume Em is still a virgin. I’d know if she wasn’t, wouldn’t I?) How many of those kinds of messages is she getting? Should I notify the school? How would the conversation with the Head of Sixth Form go: ‘Um, my daughter accidentally shared a picture of her bottom with your entire pupil body’? And what further problems might that cause Em? Isn’t it better to play it down, try to carry on as normal? I may want to kill Lizzy Knowles. I may, in fact, want her entrails hung above the school gate to discourage any future abuse of social media that mortifies a sweet, naive girl. But Emily said she didn’t want her friend to get in trouble. Best let them sort it out themselves.

I could call Richard now and tell him about the belfie, but it will distress him and the thought of having to comfort him and deal with his anxiety, as I have done for the whole of our life together, is too exhausting. No, easier to fix it myself, like I always do (whether it is a new house, a new school or a new carpet). Then, once everything is OK for Em, I will tell him.

That’s how I ended up being a liar in the office and a liar at home. If MI5 were ever looking for a perimenopausal double-agent who could do everything except remember the password (‘No, hang on, give me time, it’ll come to me in a minute’), I was a shoo-in. But, believe me, it wasn’t easy.

You may have noticed that I joke a lot about forgetfulness, but it’s not funny, it’s humiliating. For a while, I told myself it was just a phase, like that milky brain-fug I first got when I was breastfeeding Emily. I was so zombified one day, when I’d arranged to meet my college friend Debra in Selfridges (she was on maternity leave with Felix, I think), that I actually put wet loo paper in my handbag and threw the car keys down the toilet. I mean, if you put that in a book no one would believe it, would they?

This feels different, though, this new kind of forgetfulness; less like a mist that will burn itself off than some vital piece of circuitry that has gone down for good. Eighteen months into the perimenopause and I regret to say that the great library of my mind is reduced to one overdue Danielle Steel novel.

Each month, each week, each day it gets slightly harder to retrieve the things that I know. Correction. The things that I know that I knew. At forty-nine years of age, the tip of the tongue becomes a very crowded place.

Looking back, I can see all the times my memory got me out of trouble. How many exams would I have failed had I not been blessed with an almost photographic ability to scan several chapters in a textbook, carry the facts gingerly into the exam room – like an ostrich egg balanced on a saucer – regurgitate them right there on the paper and, Bingo! That fabulous, state-of-the-art digital retrieval system, which I took entirely for granted for four decades, is now a dusty provincial library staffed by Roy. Or that’s how I think of him anyway.

Others ask God to hear their prayers. I plead with Roy to rifle through my memory bank and track down a missing object/word/thingummy. Poor Roy is not in his first youth. Well, neither of us is. He has his work cut out finding where I left my phone or my purse let alone locating an obscure quotation or the name of that film I thought about the other day with the young Demi Moore and Ally Somebody.

Do you remember Donald Rumsfeld, when he was US Secretary of Defense, being mocked for talking about ‘Known Unknowns’ in Iraq? My, how we laughed at the old boy’s evasiveness. Well, finally, I have some idea what Rumsfeld meant. Perimenopause is a daily struggle with Unknown Knowns.

See that tall brunette coming towards me down the dairy aisle in the supermarket with an expectant smile on her face? Uh-oh. Who is this woman and why does she know me?

‘Roy, please can you go and get that woman’s name for me? I know we have it filed in there somewhere. Possibly under Scary School Mums or Females I Suspect Richard Fancies?’

Off Roy shuffles in his carpet slippers while Unknown But Very Friendly Tall Brunette – Gemma? Jemima? Julia? – chats away about other women we have in common. She lets slip that her daughter got all A*s in her GCSEs. Unfortunately, that hardly narrows it down, perfect grades being the must-have accessory for every middle-class child and their aspirational parents.

Sometimes, when the forgetfulness is scary bad – I mean, bad like that fish in that, that, that film

(‘Roy, hello?’) – it’s like I’m trying to get back a thought that just swam into my head then departed a millisecond later, with a flick of its minnow’s tail. Trying to retrieve the thought, I feel like a prisoner who has glimpsed the keys to her cell on a high ledge, but can’t quite reach them with her fingertips. I try to get to the keys, I stretch as hard as I can, I brush aside the cobwebs, I beg Roy to remind me what it was I came into the study/kitchen/garage for. But the mind’s a blank.

Is that why I started lying about my age? Trust me, it wasn’t vanity, it was self-preservation. An old friend from my City days told me this headhunter she knew was anxious to fill his female quota, as laid down by the Society of Investment Trusts. He was the sort of well-connected chap who can put a word in the right tufty, barnacled old ear and get you a non-executive directorship; a position on the board of a company that’s highly remunerated but requires only a few days of time a year. I figured if I had a couple of those under my belt, to supplement my financial-advice work, I could earn just enough to keep us afloat while Richard was training, while still taking care of the kids and keeping an eye on Mum and Rich’s parents as well. On paper, everything looked great. Hell, I could do two non-execs in my sleep. Full of hope, I went to meet Gerald Kerslaw.

11.45 am: Kerslaw’s office is in one of those monumental, white, wedding-cake houses in Holland Park. The front steps, of which there must be at least fifteen, feel like scaling the White Cliffs of Dover. Apart from the occasional party and meeting with clients, I haven’t worn a decent pair of shoes in a while – amazing how quickly you lose the ability to walk in heels. On the short journey from the Tube, I feel like a newborn gnu; tottering on splayed legs, I even stop to steady myself with one hand on a newspaper vendor’s stand.

‘Alright, Miss? Careful how you go,’ the guy cackles, and I am embarrassed at how absurdly grateful I am that he thinks I’m still young enough to be called Miss. (Funny how rank old sexists become charming, gallant gentlemen when you’re in need of a boost, isn’t it?)

It’s hard to comprehend how swiftly all the confidence you built up over a career ebbs away. Years of knowledge brushed aside in minutes.

‘So, Mrs Reddy, you’ve been out of the City for how long – seven years?’

Kerslaw has one of those stentorian barks that is designed to carry to the soldier mucking about at the back of the parade. He is bawling at me across a desk the size of Switzerland.

‘Kate, please call me Kate. Six and a half years actually. But I’ve taken on a lot of new responsibilities since then. Kept up my skillset, provided regular financial advice to several local people, read the financial pages every day and …’

‘I see.’ Kerslaw is holding my CV at a distance as if it is giving off a faint but unpleasant odour. Ex-Army, clip-on Lego helmet of silver hair; a small man whose shiny face bears the stretched look of someone who had always wanted to be three inches taller. The pinstripes on his jacket are far too wide, like the chalk lines on a tennis court. It’s the kind of suit only worn by a family-values politician after their cocaine-fuelled night with two hookers has been revealed in a Sunday tabloid.

‘Treasurer of the PCC?’ he says, raising one eyebrow.

‘Yes, that’s the parochial church council in the village. The books were a mess, but it was quite hard to persuade the vicar to trust me to manage their one thousand nine hundred pounds. I mean, I’d been used to running a four hundred million-pound fund so it was quite funny really and …’

‘I see. Now, moving on to your time as Chairman of the Governors at Beckles (is it?) Community College. Of what relevance might that be, Mrs Reddy?’

‘Kate, please. Well, the school was failing, about to go into special measures actually, and it took a huge amount of work to turn it around. I had to change the management structure, which was a diplomatic nightmare. You can’t believe school politics, seriously, they’re much worse than a bank, and there was all the legislation to adhere to and the inspection reports. So much red tape. An untrained person hasn’t got a hope in hell of understanding it. I instigated a merger with another school so we’d have the money to invest in frontline staff and bring down classroom sizes. It made Mergers and Acquisitions look like Teletubbies, quite frankly.’

‘I see,’ says Kerslaw, not an atom of a smile on his face. (Never watched Teletubbies with his kids, obviously.) ‘And you were not working full-time in that period because your mother was unwell, I believe?’

‘Yes, Mum – my mother – had a heart attack, but she’s much better now, made a full recovery thank goodness. I’d just like to say, Mr Kerslaw, that Beckles Community College is one of the fastest improving schools in the country, and it’s got a terrific new head who …’

‘Quite. So what I need to ask you is: if one of your children were to be ill when a board meeting was scheduled, what would you do? It’s vital that, as a non-exec director, you would have time to prepare for the meetings and, of course, attendance is compulsory.’

I don’t know how long I sit there staring at him. Seconds? Minutes? I can’t promise that my jaw isn’t resting on the green leather desktop. Do I really have to dignify that question with an answer? Even when such questions are supposed to be illegal now? It seems that I do. So, I tell the headhunter prat with his trying-too-hard red silk jacket lining that, yes, when I was a successful fund manager, my children were occasionally unwell, and I had always arranged backup care like the conscientious professional I was and that any board could have the utmost confidence in my reliability as well as my discretion.

The speech might have gone down better had a phone not chosen that exact moment to start playing the theme from The Pink Panther. I look at Kerslaw and he looks at me. Funny kind of ringtone for a stuffy old headhunter, I think. It takes a few moments to realise that the jaunty prowl of a tune is, in fact, coming from the handbag under my chair. Oh, hell. Ben must have changed my ringtone again. He thinks it’s funny.

‘I’m terribly sorry,’ I say, one hand plunged into the bag, frantically searching for the mobile, while the rest of me tries to remain as upright as possible. Why does a handbag turn into a bran tub when you need to find something fast? Purse. Tissues. Powder compact. Something sticky. Uch. Glasses. Come on! It has to be here somewhere. Got it. Switching the errant phone to Silent, I glance down to see one missed call and a text from my mother. Mum never texts. It’s as worrying as getting a handwritten letter from a teenager. ‘URGENT! Need your help. Mum x’

I hope that my face remains both smiley and calm, and that Kerslaw sees only a highly suitable non-exec director opposite him, but my imagination starts to pound. Oh, God. The possibilities swarm:

1 Mum has had another heart attack and crawled across the floor to get her mobile, which has ninety seconds’ battery life left.

2 Mum is wandering around Tesco, utterly bewildered, hair uncombed, wearing only her nightie.

3 What Mum really means is: ‘Don’t worry, they’re really very nice in intensive care.’

‘You see, Mrs Reddy,’ says Kerslaw, steepling his fingers like an archdeacon in a Trollope novel, ‘our problem is that, while you undoubtedly had a very impressive track record in the City, with excellent references which attest to that, there is simply nothing you have done in the seven years since you left Edwin Morgan Forster which would be of any interest to my clients. And then, I’m afraid to say, there is the question of your age. Late forties and fast approaching the cohort parameter beyond which …’

My mouth is dry. I’m not sure, when I open it, whether any words will come out. ‘Fifty’s the new thirty-five,’ I croak. Don’t break down, Kate, whatever you do. Let’s just get out of here, please don’t make a scene. Men hate scenes, this one especially, he’s not worth it.

I get up quickly, making it look like the decision to terminate the interview is mine. ‘Thank you for your time, Mr Kerslaw. I really appreciate it. If anything comes up, I’m not too proud to go in at a considerably more junior level.’

The door seems a long way away. And the pile on Kerslaw’s carpet is so lush it feels like my heels are sinking into a summer lawn.

12.41 pm: Back on the pavement, I call my mother and could almost cry with relief when I hear her voice. She’s alive.

‘Mum, where are you?’

‘Oh, hello, Kath, I’m in Rugworld.’

‘What?’

‘Rugworld. Better choice than you get in Allied Carpets.’

‘Mum, you said it was urgent.’

‘It is, love. What d’you think I should go for? For my lounge. The sage or the oatmeal? Or they’ve got wheatgrass. Mind you it’s very dear. Seventeen pounds ninety-nine a square metre!’

One of the most crucial interviews of my entire life has just been derailed because my mother can’t decide what colour carpet she wants.

‘The oatmeal would go with everything, Mum.’ I hardly know what I’m saying. The roaring traffic’s boom, my feet screaming to be let out of their stilettos, the sickening thump of rejection. I’m too old. Outside the cohort parameter. Old.

‘Are you all right, love?’

No, I’m not. Very much not all right, pretty bloody desperate actually. All my hopes were pinned on this interview, but I can’t tell her that. She wouldn’t understand; I’d only make her worry. The years when my mother could cope with my problems are past. At some indiscernible moment, on a day like any other, the fulcrum tips and it becomes the child’s turn to reassure the parent. (One day, I will be consoled by Emily, hard though that is to imagine now.) My father’s death five years ago was the tipping point. Even though my parents were long divorced, I think Mum secretly thought Dad would come crawling back when he was old enough or, more realistically, skint and immobile enough, to stop acquiring girlfriends younger than his own daughters. This time, though, it would be her who would have the upper hand. After he was found dead in the bed of Jade, a glamour model who lived in a flat above his favourite betting shop, it was only ten months before Mum had a coronary of her own. A broken heart isn’t just a metaphor, it turns out. So, you see, my mother can no longer be confided in, or leant upon, or burdened; I am careful what I say.

‘I just had an interview, Mum.’

‘Did you? Bet it went well, love. They couldn’t ask for anyone more conscientious, I’ll say that for you.’

‘Yes, it was really good. It all came back to me. What I need to do.’

‘You know best, love. I’ll go for the oatmeal, shall I? Mind you, oatmeal can be a bit bland. I think I fancy the sage.’

After my mother has gone off quite happily to not buy a carpet, I take first a deep breath and then a decision. I told Kerslaw I wasn’t proud, but it turns out I was wrong: I am proud, he has rekindled it. Ambition was there like a pilot light inside me, awaiting ignition. If I’m too old, then I’ll bloody well have to get younger, won’t I? If that’s what it takes to get a job I could do in my sleep, then I’ll do it. Henceforth, Kate Reddy will not be forty-nine and a half, a pitiful has-been and an unemployable irrelevance. She will not be ‘fast approaching that cohort parameter’ which doesn’t apply to over-promoted dicks like Kerslaw or men in general, only to women funnily enough. She will be … She will be forty-two!

Yes, that sounds right. Forty-two. The answer to life, the universe and everything. If Joan Collins can knock twenty years off her age to secure a part in Dynasty, I can sure as hell knock seven off mine to get a job in financial services and keep my own dynasty going. From now on, against all my better instincts, and trying not to imagine what my mother would say, I shall become a liar.

3 (#ulink_90257baf-a844-5482-8f70-56e0b87023d2)

THE BOTTOM LINE (#ulink_90257baf-a844-5482-8f70-56e0b87023d2)

Thursday,5.57 am: My joints are raw and aching. It’s like a flu that never goes away. Must be Perry and his charming symptoms again. (Just like when I woke at three with a puddle of sweat between my breasts even though the bedroom was icy cold.) I’d much rather turn over and spend another hour in bed, but there’s nothing for it. After my ordeal at the hands of the evil, pinstriped headhunter, Project Get Back to Work starts here.

Conor at the gym agreed to stretch the rules and gave me his special Bride’s Deal, for women who want to look their best on the big day. I explained that I had pretty much the same goals as any newly engaged female: I needed to persuade a man, or men, to commit and give me enough money to raise my kids and do up a dilapidated old house. There would be a honeymoon period in which I would have to lull them into thinking I would always be enthusiastic, wildly attractive and up for it.

‘Basically, I need to lose nine pounds – a stone would be even better – and look like a forty-two-year-old who is young for her age,’ I explained.

‘No worries,’ said Conor. He’s a New Zealander.

So, this is where I prepare for re-entry into a real job. By real, I mean a decently paid position, unlike my so-called ‘portfolio career’ of the past few years. Women’s magazines always make the portfolio career sound idyllic: the heroine, in a long, pale, cashmere cardigan worn over a pristine white T-shirt, wafts between rewarding freelance projects whilst being home to bake scrumptious treats for adorable kids in a kitchen that is always painted a soothing shade of dove grey.

In practice, as I soon found out, it means doing part-time work for businesses who are keen to keep you off their books to avoid paying VAT – even to avoid paying you at all. So much time wasted chasing fees. For someone who works in financial services I have a weird phobia of asking people for money – for myself anyhow. I ended up with a handful of overdemanding, underpaid projects, which I had to fit in around my primary role as chauffeur/shopper/laundress/caregiver/cook/party planner/nurse/dog-walker/homework invigilator/Internet killjoy. My office, aka the kitchen table, was covered in a sprawl of paperwork, not wholesome baked goods. My annual earnings did not run to cashmere, and the white T-shirts grew sullen in the family wash.

All successful projects begin with a stern assessment of the bottom line followed by the setting of achievable goals. With everyone still safely asleep, I lock the bathroom door, pull my nightie over my head in a single movement (‘a gesture of matchless eroticism’, a lover once called it) and examine what I see in the mirror. This is what forty-nine and a half looks like. My breasts have definitely got lower and heavier. If you were being critical (and I certainly am), they look slightly more like udders than the perky pups of yore. Actually, I got away quite lightly. Some of my friends lost theirs entirely after childbirth; their boobs inflated, but once the milk dried up they shrivelled like party balloons. Judith in my NCT group got implants after twin boys sucked her dry and her husband couldn’t bear what he charmingly called her ‘witch’s tits’. He went off with his PA anyway and Judith was left with two sacks of silicon so heavy she developed back problems. My boobs kept both their size and shape but, over the years, there’s been a palpable loss of density; it’s the difference between a perfect avocado and one that’s gone to mush in its leathery case. I guess that’s what youth means: ripeness is all.

I shiver involuntarily. It’s freezing in here, even colder in the house than it is outside because Piotr hasn’t got around to upgrading the plumbing yet. To tell you the truth, I’m scared of what he’s going to find when he takes up the floorboards. The ancient radiator beneath the window emits a grudging amount of heat; its gurgling and plopping suggest serious digestive difficulties.