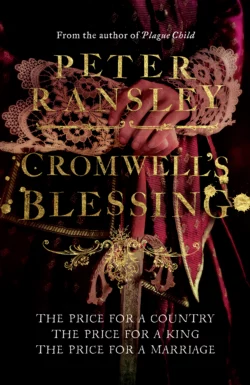

Cromwell’s Blessing

Peter Ransley

The price for a country. The price for a King. The price for a marriage. The dramatic story of Tom Neave continues…The second book in the Tom Neave Trilogy, ‘Cromwell’s Blessing’ sees Tom still determined to fight for his principles – democracy, freedom and honour – despite the growing threat to his young family, as England finds itself in the throes of bloody civil war.The year is now 1647. The King has surrendered to Parliament. Lord Stonehouse, to show his loyalty to Parliament, has named grandson Tom as his successor. But Lord Stonehouse’s son, Richard, is also Tom’s estranged father and a fervent Royalist. If the King reaches a settlement with Parliament Richard will inherit…Parliament itself is deeply divided with those demanding a strict Puritan regime pitted against more liberal Independents like Cromwell. King Charles, under house arrest, tries to exploit the divisions between them. When Richard arrives from France with a commission from the Queen to snatch the King from Parliamentary hands, he and Tom are set on a collision course. Caught between his love for his wife Anne and their young son, and his loyalty to the new regime, Tom must struggle to save both his family and the estate.

Copyright (#ulink_53e90a7c-5995-58d9-b830-10424725218e)

HarperPress

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

77–85 Fulham Palace Road

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperPress in 2012

Copyright © Peter Ransley 2012

Peter Ransley asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007312405

Ebook Edition © September 2014 ISBN: 9780007463596

Version: 2014-10-10

Dedication (#ulink_8b380c3a-8d5b-50ee-8f90-208ca40cfc55)

For Finlay

Contents

Cover (#u0075ddc9-7e14-5188-8f56-d3e95b792a45)

Title Page (#uc370eb48-7089-5aa0-b136-b29effe26a40)

Copyright (#ue080a878-76af-5f3e-93d5-605e91673658)

Dedication (#u74a1b37f-65cf-508e-9412-706f20ad68ce)

Map (#u4a9609c4-9566-5791-a0e7-a8c48b7678aa)

Part One: A Silver Spoon (#u45c82fc8-87c2-5892-b548-64c1648a14cd)

Chapter 1 (#uf7405d1f-5335-59b4-a465-06b8a4519700)

Chapter 2 (#ucb6674a8-db5d-5ff8-9d49-ad08bfa392cc)

Chapter 3 (#u47bf174c-5690-52e3-b7b7-e8e839322fc7)

Chapter 4 (#ua38b01ff-99fe-5c07-8613-5c452ec83137)

Chapter 5 (#u07679227-4bb9-5f0c-9a35-61bb698d5e52)

Chapter 6 (#uabda263f-491b-51f2-b3b1-d238d2bc984c)

Chapter 7 (#u426986a3-825a-5ead-a53b-daad94bc247b)

Chapter 8 (#u7db258ec-64a1-574c-bfc1-e036370ae372)

Chapter 9 (#uc16e8bd0-99b4-5516-816b-281a3ba701a5)

Chapter 10 (#u0bcffbdb-99ae-592b-9d0e-081142bef498)

Part Two: Cromwell’s Blessing (#u148a4c84-cdbf-5299-83b1-bf04c64e0648)

Chapter 11 (#u30b257f5-df41-5412-9d1d-4139174a8af8)

Chapter 12 (#u39cc75df-2e17-57d5-aa33-6f31888ec55e)

Chapter 13 (#uaf874527-c1b8-5e58-97c6-db8253ef55fc)

Chapter 14 (#u66166e87-c0ea-5148-989d-9be591bbb6b8)

Chapter 15 (#ue71c58a1-e796-538c-a8db-d20d6f5ab9b1)

Chapter 16 (#ud4e9b979-932f-57bf-9a6d-bc83b41c9bb0)

Chapter 17 (#uace4caa3-a0d7-5ab4-8b1c-c675cd875a72)

Chapter 18 (#uc6d10de5-6eab-591e-8c5b-2bf07d003f4a)

Chapter 19 (#u21cb48c1-869c-5022-92b5-d2db04440a6f)

Chapter 20 (#u05b8e85a-5e30-5e5b-a147-dd36f7dc9135)

Chapter 21 (#u3f25d6d2-cf76-5dc9-820a-ed0f7ee3c97e)

Chapter 22 (#udb48c13c-c813-5aa8-acfe-6f13d0334add)

Chapter 23 (#u1f59036a-472a-5e29-a60f-d85b2f64305a)

Chapter 24 (#u476e261f-f7bb-5cc0-adaa-e2402f07d2bb)

Chapter 25 (#ub084a544-d8c7-5371-a6fc-5ed4f09696ca)

Chapter 26 (#u8911ac71-188e-5d88-8761-9fd580cf1e3b)

Chapter 27 (#u2ec68ca5-0a76-5e65-adcb-6e1d487467e6)

Chapter 28 (#u91266e0d-d764-5b74-847f-b423b4da0746)

Part Three: Without (#u6dae030c-940d-581b-b67c-86eb5373d8dd)

Chapter 29 (#ue3847921-189e-5377-98d8-9519470fa5ff)

Chapter 30 (#uff07e766-9816-5a0f-b253-0f1daf8ff91d)

Chapter 31 (#uc3b84543-dea9-5d8c-a48b-11f02d1a76e7)

Chapter 32 (#u9c111665-d711-5e61-b395-1dc46ebad65a)

Chapter 33 (#u0efae671-2343-5413-972f-3eff7325c111)

Chapter 34 (#u56e3439d-e3aa-566a-abc4-61cb28fd8b51)

Chapter 35 (#u8a858162-3b98-5d84-afe4-e96b5493f58f)

Chapter 36 (#uc4a21909-ef52-570e-be32-6873d18210bb)

Part Four: The Signature (#u776c77fa-33c0-5356-971b-9fe7a7bc509c)

Chapter 37 (#u2a770074-a672-51f6-92f9-5e03ae169232)

Chapter 38 (#u8c9eb8ee-7b91-50a2-b18c-4a0b3b2eb282)

Chapter 39 (#u2923042d-34ad-5899-9e58-f7175db5e516)

Historical Note (#u3ba2de09-3f19-51e9-8d35-768cf6db34b9)

Read an extract from THE KING’S LIST (#u7d790d71-f3c8-5e8f-8c5c-c542aa7f6744)

Acknowledgements (#u06e3b37e-239b-584c-8eb8-86a3b342f62c)

About the Author (#uf1d579e0-f1a6-5866-aba7-b6d9e5eec24e)

Also by Peter Ransley (#ude52c2b8-4de9-59f3-8054-42c486a0e85e)

About the Publisher (#ue215659f-70b3-5da8-bc91-00589159411d)

PART ONE (#ulink_28586cf0-f6b4-563e-a08e-891fa75ed796)

1 (#ulink_e8dd1017-f89c-56d7-8819-77adda638389)

I could not stop shivering. That February morning in 1647 was the coldest, bleakest morning of the whole winter, but it was going to be far colder, far bleaker for Trooper Scogman when I told him he was going to be hanged.

Most mornings I woke up and knew exactly who I was: Major Thomas Stonehouse, heir to the great estate of Highpoint near Oxford, if my grandfather, Lord Stonehouse, was to be believed. Now the Civil War was over, sometimes, in that first moment of waking, I woke up as Tom Neave, one-time bastard, usurper and scurrilous pamphleteer.

That morning was one of them.

I should have left it up to Sergeant Potter to tell Scogman, but he would have relished it: taunted Scogman, left him in suspense. At least I would tell him straight out.

My regiment was billeted at a farm near Dutton’s End, Essex, part of an estate seized by Parliament from a Royalist who had fled the country. The pail outside was solid ice. The dog opened one eye before curling back into a tight ball. Straw, frosted over in the yard, snapped under my boots like icicles. A crow seemed scarcely able to lift its wings as it drifted over the soldiers’ tents.

More soldiers in their red uniforms were snoring in the barns, where horses were also stabled. We were a cavalry unit, the justification for calling Cromwell’s New Model Army both new and a model for the future. Whereas the foot soldiers were pressed men, who would desert as soon as you turned your back, the cavalry were volunteers. They were the sons of yeomen or tradesmen, who brought to war the discipline of their Guilds. They joined not just for the better pay – and the horse which would carry their packs – but because they were God-fearing and believed in Parliament.

Except for Scogman.

I approached the wooden shed which was the camp’s makeshift prison. I half-hoped Scogman had escaped, but I could see the padlock, still intact, and the guard asleep, huddled in blankets.

Scogman on the loose would have been worse. The countryside would have been up in arms. Villagers resented us enough when we were fighting the war. Now it was over, and we were still here, they hated us.

Six months had passed since the Royalist defeat at the battle of Naseby. Yet the King was in the hands of the Scots. We were supposed to be on the same side – but the Scots would not leave England until they were paid and there were rumours they were doing a secret deal with the King. In spite of the stone in his bladder, his piles and his liver, Lord Stonehouse was in Newcastle, negotiating for the release of the King.

‘We could not govern with him,’ he wrote tersely to me. ‘But we cannot govern without him.’

The guard, Kenwick, was a stationer’s son from Holborn – I knew them all by their trades. I prodded him gently with my boot. ‘Still there, is he?’

Kenwick shot up, turning with a look of terror towards the shed, as if expecting to see the padlock broken, the door yawning open. He saluted, found the key and made up for being asleep on duty by bringing the butt of his musket down on a bundle of straw rising and falling in the corner. The bundle groaned but scarcely moved. Kenwick brought the butt down more viciously. The bundle swore at him and began to part. Somehow, I thought resentfully, even in these unpromising conditions, Scogman managed to build up a fug of heat not found anywhere else on camp.

I waved Kenwick away as, with a rattle of chains, Scogman stumbled to his feet. His hair was the colour of the dirty straw he emerged from, the broken nose on his cherub-like face giving him a look of injured innocence. Trade: farrier, although sometimes I thought all he knew about horses was how to steal them.

‘At ease, Scogman.’

He shuffled his leg irons. ‘If you remove these, sir, I will be able to obey your order. Major Stonehouse. Sir.’ He brought up his cuffed hands in a clumsy salute.

Kenwick bit back a smile. I stared at Scogman coldly.

He was about my age, twenty-two, but looked younger, thin as a rake, although he ate with a voracious appetite. Scoggy was the regiment’s scrounger. He stole for the hell of it, for the challenge. In normal life he would have been hanged long ago. But when a regiment lived off the land he became an asset.

It only took one person to point out a plump hen, and not only would chicken be on the menu that night, but a pot in which to cook it would mysteriously appear. There were many who looked the other way in the regiment, except for strict Presbyterians like Sergeant Potter and Colonel Greaves, but in war the odds had been on Scoggy’s side. In this uneasy peace his luck had run out. Scoggy had been caught stealing not just cheese, but a silver spoon. Not only that. He had stolen it from Sir Lewis Challoner, the local magistrate.

I chewed on an empty pipe, knocked it against my boot and cleared my throat. Scogman could read my reluctance and in his eyes was a look of hope. I cursed myself for coming. I should have sent Sergeant Potter. Scoggy would have known, however Potter taunted him, there was no hope. I struggled to find the words. In my mouth was the taste of the roast suckling pig Scoggy had somehow conjured up after Naseby. Even Cromwell had eaten it, praising the Lord for providing such fare to match a great victory. Cromwell believed in the virtue of his cavalry to the point of naivety, but when they sinned, he was merciless. I must follow my mentor’s lead.

‘You know the penalty for stealing silver, Scogman?’

‘Yes, sir. Permission to speak, sir.’

‘Go on,’ I said wearily.

‘Wife and children in London, sir. Starving.’

He knew I had a son. We had talked over many a camp fire about children we had never or rarely seen. ‘You should have waited for your wages like everyone else.’

‘We’re three months behind, sir. There’s talk we’re never going to be paid what we’re owed.’

It was true Parliament was dragging its feet over the money the troops were owed, and a host of other problems, like indemnity and injury benefits. Meanwhile soldiers scraped by on meagre savings, borrowed or stole.

‘That’s nonsense. Of course you’ll be paid. Eventually. You should tighten your belt like everyone else.’

Scogman glanced down at his belt, taut over the narrow waist of his red uniform. Again Kenwick repressed a smile. I took the spoon from my pocket. My breath fogged it over. It looked a miserable object to be hanged for. ‘Why the hell did you steal a silver spoon?’

He couldn’t resist it. ‘Because I never had one in my mouth, sir.’

Kenwick showed no sign of laughing, after looking at my expression.

‘You will go before the magistrate.’

Even then he didn’t believe me. ‘I’d rather be tried by you, sir.’

‘I’ll bet you would. Sir Lewis may be lenient. Lock him up, Kenwick.’

I turned away, but not before I caught Scogman’s cockiness, his bravado, shrivel like a pricked bladder. Outside, while the crows flapped lazily away, I tried to do what Cromwell did when he ordered a man’s death. He prayed for his soul; it was not his order, he told himself, but God’s will. Then he would unclasp his hands and go on to his next business. Rising over the thud of the door and the rattle of the padlock came Scogman’s voice.

‘Lenient? Sir Lewis Challoner, sir? He’s a hanging magistrate! Major Stonehouse!’

I put my hands together but could not find the words to form a prayer.

2 (#ulink_5a5d9b90-3973-5ad5-9318-3f627f0f5287)

Sir Lewis was also the local MP. He was, Lord Stonehouse had warned me, one of the more amenable Presbyterian MPs and a man I must be careful to cultivate.

There were now two parties. The Presbyterians were conservative, strict in religion, and softer in the line they pursued with the King. The Independents, led by Cromwell, were tolerant to the various religious sects that had sprung up during the war, such as Baptists and Quakers. They wanted to make sure the absolute power of the King, who had plunged the country into five years of devastating war, was removed.

That, at least, was how I saw it. My burning ambition was to be one of the Independent MPs who reached that settlement. I was Cromwell’s adjutant when Lord Stonehouse suggested I was sent here to quell the unrest. He did not say so, but I was sure it was a test – handle the delicate relationship between soldiers and villagers and I would be on my way to Parliament. It was all the more important because the New Model Army was Cromwell’s power base. Discredit the army, and you discredited him.

Word about Scogman got round quickly. Troopers saluted me, but averted their eyes and muttered in corners. I retired to the farm kitchen where Daisy, the kitchen maid, brought me bread and cheese and small beer. Her eyes were red. She sniffed and wiped her nose with the corner of her apron. Scogman not only stole chickens, pigs and silver spoons; he stole hearts. She kept poking the fire, scrubbing an already scrubbed pot and sniffing, until she turned to me, blurting out the words.

‘It’s my fault, sir.’

‘Your fault, Daisy?’

‘He stole the silver spoon for me, sir.’

‘Why on earth would he do that?’

‘It’s, it’s … a sign of love, sir.’ She scrubbed the scrubbed pot and went as red as the fire. ‘Is it true, sir … you’re going to hang Scoggy?’

‘No, Daisy.’ Her eyes brightened. I gulped down the remaining beer. ‘He’s going before the magistrate.’

She burst into tears and fled.

Worst of all was Sergeant Potter who congratulated me for getting rid of that evil, thieving bastard. That would send a message to the other God-forsaken backsliders! The regiment was getting out of control and Dutton’s End was up in arms. Had I marked the minister’s sermon, echoing other sermons throughout Essex calling for a petition to Parliament to disband the army, which from being a blessing had become a curse, a leech, sucking the life-blood from village and country?

I winced when he said his only regret was that he could not tie the neckweed himself and retreated to the outhouse where I had my office. I wrote the letter to Sir Lewis, handing Scogman over to his jurisdiction and asking him for a leniency I knew he would not grant. I sent for Lieutenant Gage to deliver it. Instead I got Captain Will Ormonde.

Of all the delicate situations at Dutton’s End Will was the most sensitive. We had rioted together in the uprising for Parliament, the riots that had driven the King from London. We had fought in the first battles of the war together. When this regiment’s Colonel, Greaves, had fallen ill, Will had expected promotion. Instead, I had been sent to take temporary charge. He was right to think bitterly that it was because of Lord Stonehouse he had been passed over. But it was only partly that. He was too hot-headed and radical. Before I got here, he had made a bad situation worse.

Will was in his early twenties but, like all of us, looked older. He wore his hair long to cover an ear mutilated by a sabre slash.

‘You can’t send Scoggy to that bastard, Tom. We’ve all eaten his meat.’

‘This isn’t meat. It’s a felony.’

‘He’s denied it.’

‘Will, he was seen at the robbery! I searched his pack and found the spoon there. I’ve given him warning after warning.’

‘I know,’ he conceded. ‘But Scoggy.’

That was his best argument. But Scoggy. Scoggy was more than a scrounger. A thief. A womaniser. He was a joke at the end of a day of despair. The man who could always find a beer, whose flint was dry when everyone else’s was wet.

Will stared at the letter I had written, sealed and ready for Lieutenant Gage to deliver. ‘Try him here.’

‘Parliament wants felonies passed to the civil authority.’

‘Parliament.’ There was disappointment, frustration, impatience in his voice.

‘It’s what we fought for.’

His answer was to pull out a sheet of paper. ‘Have you seen this?’

I knew what it was before he handed it to me. There was a rebellion in Ireland and the army was trying to raise volunteers. The paper contained the names of the men in the regiment. Only a few had ticks by them. They were rootless men like Bennet, a gunsmith, who had developed a taste for war and was the regiment’s crack marksman. The last thing the vast majority wanted was to go to Ireland. They wanted, above everything else, what I wanted – to go home.

‘The men believe they won’t be paid unless they agree to go to Ireland.’

‘That’s nonsense.’

‘That’s what Potter’s saying.’

‘I’ll speak to him.’ I picked up the letter.

‘Tom. If you send that letter to Sir Lewis the soldiers will riot.’

My mouth was suddenly dry. I got up, opened the door and shouted for Lieutenant Gage. I waited until I was sure of controlling my voice. ‘There is to be no riot, Will. You are to keep order.’

His fists were clenched, his face a dull red. I could see Lieutenant Gage approaching. Will brought his hand up in a salute and barked savagely: ‘Very good, sir.’ He almost cannoned into Gage on his way out. I handed Gage the letter and gave him instructions for delivery.

It was a few minutes before I could stop shaking.

There was a lane with high hedgerows not far from the shed where Scogman was kept. It twisted away from the camp towards Dutton’s End and I hoped that, if the bailiff took Scogman that route, any disturbance could be kept to a minimum. The last thing I expected was for Sir Lewis Challoner to come for his prey himself.

He had been a Royalist at the beginning of the war but when he had seen which way the wind was blowing had changed sides, bringing a vital artillery train to Parliament. He rode into the farmyard followed by his bailiff Stalker. He looked as if he had lunched well, spots of grease gleaming on his ample chins as he smiled affably down at me from his horse.

‘Well, well, Major. We are returned to the rule of law, are we?’

‘We never left it, Sir Lewis,’ I said, returning his smile.

There was a cheer from somewhere nearby, and the smile went from Sir Lewis’s face. Soldiers had appeared from the barn and the stables. Daisy was at the kitchen window, dabbing her face with her apron. Bennet, the marksman, was cleaning his musket. The dog that followed him on his poaching expeditions was at his heels.

I could smell the wine on Sir Lewis’s breath as I went close to him. ‘Better do this as quietly and quickly as possible.’

He gave me a fat, innocent, smile. ‘You can control your men, can’t you, Major?’

‘You are provoking them, Sir Lewis,’ I said coldly. ‘I will not have it. If you want him, take him.’

He glared down at me. ‘Very well. The felon, Stalker.’

Stalker did not smile. He was a devout Puritan and gave the soldiers a gloomy but satisfied look, as if the world, which had been upside down, had righted itself again and he was back in control. He nodded to several of them, as if to say – I know you. You stole a ham. And you, you fornicator. She’s with child. Don’t worry. I have you all on my list. Some of the men slipped away under his gaze. Others muttered angrily. Only Bennet returned his gaze with interest, and patted the growling dog gently.

I got my horse and led the two of them across the fields. Sir Lewis still seemed eager to pursue an argument. He jerked his thumb back at the soldiers. ‘Some of those fellows, I believe, think the final authority rests not with the King, nor the Commons, but the people.’

I shook my head. ‘They might in a London alehouse. Not here.’

His pale eyes narrowed. ‘Is that so?’

‘Most are not interested in politics, Sir Lewis. All they want is to be paid what they’re owed, go home to their families, work and no longer be a burden to the countryside.’

‘They are pagans,’ Stalker said. ‘They declare themselves preachers. Spread false doctrine.’

‘They only pray here, Mr Stalker, because you will not allow them in your church.’

‘Because they are rabble, sir.’

‘They preach because they have no minister available. Is it not better that they try to reach God, than not try at all?’

Sir Lewis pursed his lips. ‘Dangerous, sir, dangerous.’ But he was mollified by the sight of Scogman in chains being bundled into a cart by Sergeant Potter. Stalker rode off towards them, and Sir Lewis thawed even further, to the extent he said he could see why Lord Stonehouse put such an extraordinary amount of trust in so young a man. He gave me a prodigious wink and began to rhapsodise about the beauty of the countryside around us. It was neglected, but the soil was rich and it was well watered. He gave me another wink, a slap on the back and said perhaps we could meet again to talk about country affairs. I was somewhat bemused by this abrupt change of heart, but put it down to the wine at lunch and – perhaps a little – to my diplomacy.

‘My regards to Lord Stonehouse,’ he said, and made as if to leave.

I turned away, expecting Sir Lewis and Stalker to ride off immediately, escorting the cart and its prisoner down the lane to avoid the soldiers. But I heard Scogman give a yell of pain.

I ran back to see the cart had come to a stop at the beginning of the lane. Scogman was being manhandled from it by Stalker and Sergeant Potter. They were threading a rope through his chains with the intention of tying it to Stalker’s saddle. I hurried back to them.

‘Sir Lewis, for pity’s sake take him in the cart! You will rouse my soldiers!’

He put on a puzzled look, belied by his quivering jowls. ‘The New Model Army? It is a model of discipline, Major, is it not?’

Scogman pulled away, tripping and falling. His britches were torn and his legs bleeding where the chains had cut into them.

‘Release him. Take him in the cart, or you do not take him at all.’ I struggled to keep my voice even.

Stalker hesitated. Sir Lewis lifted his head. I could see why they called him a hanging magistrate as he gave me a look of unflinching hostility. But he kept his voice friendly, even jovial, taking out the letter I had sent him.

‘This is your signature, sir? Your seal, is it not? You have released him to me and I will have him as I will. Good day to you, sir. Get on with it, Stalker! What are you waiting for, man?’

Stalker yanked Scogman towards his horse and tied him to his saddle. I stood impotently. What a stupid, naive fool I was to think a man like Challoner would ever be in a mood for compromise. He wanted to drag his prisoner through the town to demonstrate his power. Stones, rotting vegetables and shit would be hurled at him. He would be lucky to enter prison alive.

Diplomacy? Far from helping to heal the wounds between town and soldiers, releasing Scogman would inflame them.

At least if God had made me eternally hopeful – or hopelessly naive – he had given me the quick wit to get out of the mire I found myself in. Or perhaps, as some had held, ever since I was born, it was the Devil.

And mire it was. Crows rose and flapped as soldiers, aroused by Scogman’s screaming, streamed from the farm. Will was keeping them half-heartedly under control, but I saw the barrel of a musket poking through the hedge. Stalker was riding slowly, Scogman stumbling after, almost under the hooves of Challoner’s following horse. As they saw the soldiers, Stalker urged his horse into a trot. Scogman stumbled and fell. He made no sound as he was dragged from the ditch into the lane and back again. Perhaps he would not cry out in front of his fellow soldiers. More likely he was barely conscious.

I pushed through the hedge but could not see the musketeer. It must be Bennet. If it was, Sir Lewis was as good as dead. We would no longer just have a problem of unrest but a major crisis that the Presbyterian majority in Parliament would seize on against Cromwell. I heard the click of the dog lock, releasing the musket’s trigger.

‘Wait!’ I shouted to Sir Lewis. ‘You have forgot the evidence!’

I pulled the spoon from my pocket. The ridiculous-looking spoon, slightly bent. A man’s life. Sir Lewis, a stickler for correctness in his court, checked his horse.

‘Get down from your horse unless you want to be shot,’ I said.

‘Go to hell.’

‘Get down, man, or I cannot guarantee your life!’

He saw the barrel of the musket. He had courage, I’ll grant him that. He tried to ride forward, his horse’s hooves an inch from Scogman’s face, but at that same moment I made a grab for his horse’s reins and Stalker, catching sight of the musket, slid from his saddle. Sir Lewis lurched and fell clumsily to the ground. A cheer rose from the watching soldiers before Will quietened them.

I tried to help Sir Lewis up, but he shoved me away, lips, jowls shaking in a face so puce with rage I thought he had had a stroke. I apologised to him and said I thought a mistake had been made.

For a moment he could not trust himself to speak. Then his face gradually resumed its normal dull red colour and he found his chilling, courtroom voice. ‘A mistake! Sir, you have made the mistake of your life! I will have you in the same cell as him,’ and he pointed at Scogman, who was coming round, staring up at us in bewilderment.

‘He may not have committed a felony.’

‘May not …? May not …? He stole silver, sir!’

‘Blake!’ I shouted across the field. ‘Where is Trooper Blake?’

Blake pushed his way through the soldiers, who had by now spilled into the lane ahead of us. He was an odd man, prematurely bald, slightly hunchbacked, but the soldiers respected him because he could fix almost anything, from a leaking pot to a broken flintlock.

‘Trade?’ I said.

‘Journeyman silversmith, sir,’ Blake said with a salute. ‘City of London, Goldsmiths’ Guild.’

He straightened, losing some of his stoop, and his eyes gleamed with pride, a pride that began to be reflected in many of the sullen, punch-drunk faces around him. These were men who had almost forgotten they had trades, and another life, and were beginning to wonder, in this purgatory of waiting, whether they would ever return to them. They began to grin as I handed the spoon to Blake.

‘What do you think this is, Blake?’

‘A – it’s a spoon, sir.’

There was a volley of laughter from the men until Sergeant Potter shouted them into some kind of order.

‘No, man! I mean, is it silver?’

Challoner snarled at me for what he called my equivocation but then, in spite of himself, watched as Blake bit the spoon, polished it and bent it. Finally he peered short-sightedly at the leopard’s head on the back of the handle. There was complete silence, except for the rattle of chains as Scogman stumbled to his feet. Blake seemed wholly concerned with making as honest and accurate a judgement as he could, no matter that a man’s life was at stake.

‘Mmm. It’s difficult to say, sir.’

‘Your opinion, man!’

Blake caught the sharpness of my tone and slowly it dawned on him that I wanted him to perjure his craftsman’s judgement. ‘Well … the leopard’s head mark is very crude … I would say it’s a fake.’

Someone held Scogman up as he almost collapsed. Challoner tried to grab the silver spoon before it disappeared into my pocket again. ‘Give it to me! I’ll have it assayed!’

‘Lieutenant Gage!’ I shouted.

Gage cottoned on much more quickly than Blake. Stepping forward into my makeshift court, he declared himself to be from Gray’s Inn, giving the impression of a lawyer, rather than the clerk he was. Blake valued the spoon at a few pence. Thefts above a shilling were a hanging offence. Whether a soldier might be punished by the army or the civil courts for a lesser offence was a grey area. I told Challoner I would punish Scogman myself. By this time he was almost incoherent with rage.

‘Justice? You call this New Model Justice? I’ll give you justice!’

On one side I had Challoner threatening me. On the other, the grinning soldiers and Will whispering in my ear that I had the judgement of Solomon. I could not stand either of them. I could not stand myself. I had fondly imagined I would bring both sides closer with my diplomacy. Now they were so far apart there would be open warfare between town and soldiers. I was filled with a cold ferocious anger which I could scarcely keep under control. Stalker was helping Challoner back on his horse when I stopped him.

‘Justice? I will show you justice!’

I snatched the whip from Stalker’s saddle and told Sergeant Potter to unchain Scogman.

‘Strip him.’

There was not much to strip. His britches were in shreds from being dragged along the lane and his jerkin came off in two pieces. His fair hair was dark with matted blood and weals stood out on his ankles and wrists. He stumbled groggily as Sergeant Potter spreadeagled him against a fence. Still he grinned at his mates and, when he saw Daisy peering from the edge of the crowd, waggled his sex at her. Cheers rose when she fled into the farmhouse.

Challoner watched from his horse, his curled lip indicating he believed this to be as much a masquerade as the spoon.

I tossed the whip to Bennet, the man I believed had held the musket, which had disappeared. ‘Twenty lashes.’

In spite of his bravado, Scogman would scarcely have been able to stand without the ropes that tied his hands to the fence. His knees buckled. Blood ran from a fresh head wound and trickled slowly down his back. Ben, the surgeon, took a step towards me, but turned away when he saw my expression. He knew this mood of mine.

Bennet smoothed the lash between his fingers. He measured his stance. The crowd fell silent. The whip cracked. Scogman winced and his eyes jerked shut, although the tip of the whip barely touched his flesh. Bennet’s natural love of violence was held in check by the feeling of his watching colleagues. Perhaps, instead, he gained a perverse pleasure from taunting Stalker and Challoner by not drawing blood. The whip cracked harmlessly again, and this time there was no doubt about it, Scogman joined in the masquerade, jerking and writhing theatrically.

Challoner turned his horse away in contempt and disgust.

I wrenched the whip from Bennet’s hand and lashed out clumsily at Scogman’s back. He gave one startled cry and then fell silent. I wanted him to cry out, to scream, but where he had performed for Bennet, he would not perform for me. After the first line of blood the watching faces disappeared and I saw nothing and heard nothing, until my arm was gripped and Ben pulled me away. I stared at him blankly, then at the whip, then at what I at first took to be a piece of raw meat in front of me. It was all I could do to swallow back the vomit that rose in my throat.

I flung the whip back at Challoner.

‘Satisfied?’

3 (#ulink_a2c1089b-213e-5581-b48c-96884d08d24d)

Over the next few days Challoner continued hounding me to hand Scogman over, but I refused. Ben told me he was not expected to live. The least I could do was let him die under Daisy’s care for, while there was a shred of life left in him, Challoner would certainly hang him.

Ben wanted to purge me, saying my humours were severely out of balance, but I would have none of it. I had a curt letter from Lord Stonehouse in Newcastle, ordering me to go home. Colonel Greaves had recovered, and was returning to the regiment.

I rode alone from Essex to London. The countryside was bare, many fields overgrown with weeds, while all the troop movements had left the roads looking as though a giant plough had been taken to them. In a world upside down, even the seasons had not escaped. Spring was not merely late; it looked as if it would never appear. Most of the trees had been chopped down for firewood, during the Royalist blockade of Newcastle that had stopped coal ships coming to London.

All I could see was Scogman’s raw, bleeding back and the sullen resentful faces of my men. No – no longer my men. I had lost them. Lost myself. By the time I arrived in London, those memories had left me in total darkness. My wife Anne knew the mood, the strange blackness that came over me, and saw it in my face when I half-fell from my horse into her arms. Her embrace was more soothing than any physic, blotting out the memory of that bleeding back.

For days I slept or wandered in the garden of our house in Drury Lane, where Anne’s green fingers had planted an apple tree. The one in Half Moon Court where we had played as children, then snatched our first kisses, had been chopped down in the last bitter winter of the war. I felt the first, tight swelling of the buds on the young tree, still black, waiting for the warmth of the sun. There would be spring in this little garden; perhaps the tree would bear its first fruit.

Cromwell lived in the same lane and I screwed up my courage to go and see him, but was told he was ill, with an abscess in the head which would not clear. The news made me even more disconsolate.

‘You are not yourself, sir,’ said Jane, the housekeeper.

I tried to laugh it off. ‘Exactly, Jane! I am not myself. I must find myself! Where am I?’

Was I with the sullen resentful men, or was I, could I ever be, with people like Challoner?

‘Where am I?’ I said to my son Luke, who, when I had arrived, had stared in wonder at this strange man tumbling from a horse into his mother’s arms. ‘Am I under the chair, Luke? No! The table?’

Luke ran to Jane, covering his face in her skirts. ‘Come, sir!’ she laughed. ‘Tom is your father!’

‘Fath-er?’

It grieved me that I had spent half my life finding out who my father was, and now Luke did not know his. He had dark curls, in which I fancied there was a trace of red, and the Stonehouse nose; what in my plebeian days I called hooked, but Lord Stonehouse called aquiline. Although Luke’s grandfather doted on him, he treated the boy very sternly. Perhaps because of that, Luke often ran to him, as he did to the ostler, Adams, who would level a bitten fingernail at him and order him to keep clear of his horses, or he would not answer for the consequences. Luke would run away yelling, then creep quietly back for another levelled nail before at last Adams would snatch him up screaming and plonk him in the saddle. I felt a stab of petty resentment he would not play these games with me, and went upstairs to the nursery to find my daughter Elizabeth.

She was a few months old. Anne had been bitterly disappointed she was not a boy. It was a rare week which did not see at least one child buried in our old church of St Mark’s and Anne wanted as many male heirs as possible to reinforce Lord Stonehouse’s promise I should inherit.

Lord Stonehouse’s first son, Richard, had gone over to the Royalists, and when Lord Stonehouse had declared I would inherit I had fondly imagined it was because of my own merit. In part, perhaps it was. But it was also because he had been discovered helping Richard escape to France. Declaring me as his heir not only saved Lord Stonehouse’s skin. It enabled him to back both horses: whoever ruled, it was the estate that mattered, keeping and expanding the magnificent seat at Highpoint and preserving the Stonehouse name at the centre of power.

Elizabeth, little Liz, did not look a Stonehouse. In my present, rebellious mood, she was my secret companion. Or was it weapon?

‘Liz Neave,’ I whispered to her, giving her the name I had grown up with when I was a bastard in Poplar, and knew nothing of the Stonehouses. She had scraps of hair, still black, but I fancied I could see a reddish tinge. Her nose was not aquiline, or hooked, but a delicious little snub. Anne called her fractious, but her crying reminded me of my own wildness.

When I held out my finger she stopped crying, gripping it with her hand so tightly, I could not stop laughing. Her lips, blowing little bubbles of spit, formed their first laugh. I swept her up, and hugged her and kissed her. Fractious? She was not fractious! I rocked her in my arms until she fell asleep.

I went to our old church, St Mark’s, to see the minister, Mr Tooley, about Liz’s baptism. Anne wanted it done in the old way, with water from the font in which she had been baptised, and godparents. Mr Tooley still did it, although the Presbyterians, who were tightening their grip on the Church, frowned on both.

The church was empty, apart from an old man in a front pew, his clasped hands trembling in some private grief. The familiar pew drew out of me my first prayer for a long time. I feared Scogman was dead. I prayed for forgiveness for my evil temper. For Scogman’s soul. He was a thief, but he stole for others, as much, if not more than for himself. There was much good in him, he was kind and cheered others – by the time I had finished he was near sainthood and I was the devil incarnate. One thing came to me. I determined to find Scogman’s wife and children and do what I could for them. I swore I would never again let my black temper gain control of me.

The man rose at the same time as I did. It was my old master, Mr Black, Anne’s father. I had never before seen tears on his face. He drew his sleeve over his face when he saw me.

‘Tom … my lord …’

I wore a black velvet cloak edged with silver. My short sword had a silver pommel and my favourite plumed hat was set at a rakish angle.

‘No, no, master … not lord yet … and always Tom to thee.’

I embraced him and asked him what was the matter. He told me he might be suspended from the Lord’s Table.

‘Thrown out of the Church? Why?’

He told me the Presbyterians were setting up a council of lay elders. The most virulent of the elders, who morosely policed moral discipline in the parish, was none other than Mr Black’s previous journeyman printer, my old enemy Gloomy George.

I could not believe it. We had fought a long, bloody war for freedom and tolerance, and what we had at the end of it was Gloomy George. I began to laugh at the absurdity of it, but stopped when I saw what distress Mr Black was in. The Mr Black I knew would have laughed too, but this one trembled in bewilderment so much that I sat him down.

I could see how the church had changed. Mr Tooley had allowed a few images, like a picture of the Trinity, because they comforted older members of the congregation. Now it was stripped so bare and stark even the light seemed afraid to enter. Mr Black said that when Mr Tooley used to preach, stern as he was, you left counting your blessings. Now, with the Presbyterians breathing down his neck, his sermons left you counting your sins.

‘But what sin could he possibly find in you?’ I cried.

‘Nehemiah.’

‘Your apprentice? He is as devout as you are.’

‘More so. But he has become a Baptist, and refuses to come here.’

‘If he refuses you, he has broken his bond. You could dismiss him.’

Mr Black’s watery eyes flashed with some of his old fire. ‘He is a good apprentice. And he is devout. I will not dismiss a man for his beliefs.’

We sat in silence for a while. He stared at the blank wall where the Trinity had been. All his life he had been a staunch member of the congregation and the community. He was as responsible for Nehemiah as a father for his children. But the Presbyterians condemned all sects like Baptists as heresies and unless Mr Black brought Nehemiah back into the fold, he would be refused the sacraments. Friends and business would melt away. Even threatened with hell, he stuck stubbornly to his old beliefs in loyalty and duty.

‘How long has Nehemiah’s indenture to run?’

‘Nine months.’

I pretended to calculate, then frowned. ‘You are surely mistaken, master. It ends next week.’ I stared at him, keeping my face straight. ‘Once he’s indentured he can leave. Get another job.’

He returned my stare with interest. He needed no abacus or record where figures were concerned. ‘I don’t know what you’re suggesting,’ he snapped, ‘but I know when he’s indentured. To the day.’ He picked up his stick and I flinched, an apprentice again, fearing a beating. He limped out of the church and stood among the gravestones as if he was gazing into the pit.

‘The Stationery Office has his full record,’ he said.

‘Records can be lost. Once he has completed his apprenticeship he is not your responsibility. Is he good enough to be indentured?’

‘Better than most journeymen.’

‘Well then. When he is indentured I can help him get work elsewhere and you can take on another apprentice.’

‘It is most irregular,’ he muttered.

‘If everything had been regular, master, we would not have won the war. There were not half enough qualified armourers and blacksmiths to make all the arms we needed.’

He still looked troubled but said: ‘Well, well, if that is the way the world is now … But I would not know what to say to him.’

‘I will do it. We got on well, and he will listen to me.’

Elated with what I hoped would be a better attempt at diplomacy, I went to see Mr Tooley about Liz’s baptism. He was engaged in a room across the corridor. I waited in a small anteroom. A cupboard, I remembered, contained books I might occupy myself with. It was locked, but I knew where the key was hidden for I used to borrow books to improve my reading. When I opened it, out spilled a number of objects that had once been part of the church.

There were old, mouldering copies of the Book of Common Prayer which the Presbyterians had banned, brass candlesticks spotted with green mildew, the picture of the Trinity I had missed in the church, cracked and torn, and a rolled-up linen surplice. Everything that had once brought light and colour into the church had been buried here. An ineffable sense of sadness crept over me as I opened a prayer book and the musty smell brought back to me the light and comfort of the old church.

A nearby door opened and a chill ran through me as I heard the unmistakable voice of the man who had beaten me so often as a child – for the good of my soul, as he put it. I put the prayer book down on a chair and went to the door, beginning to open it so they would know I was there. But they were too intent on their argument to see me.

George was in the doorway of Mr Tooley’s study, his back to me. He was almost bald, his head gleaming as though polished.

‘You must name Nehemiah a heretic in church on Sunday, Mr Tooley.’

George used to address Mr Tooley with wheedling deference. I was amazed at his hectoring tone. Even more so by Mr Tooley accepting it, although his face was flushed and he struggled to keep his voice even. ‘I will see Mr Black again.’

‘He is obdurate. Stiffnecked. As the Proverbs have it, Mr Tooley: “Comes want, comes shame from warnings unheeded.”’

The years dropped away. He could have been talking to me when I was an apprentice. My nails bit into my palms and my cheeks were burning.

‘What irks a man more than vinegar on his tooth? A lingering messenger,’ Mr Tooley responded. ‘As the Proverbs have it.’

I gave a silent cheer. As George turned to go, I saw I had left the cupboard door wide open. Mr Tooley’s old surplice lay unrolled on the floor. Hastily, I crammed things back into the cupboard, shut the door and hid the key. During this, George fired his parting shot. It was couched more in sorrow than in anger.

‘The warning is not just for the sheep, Mr Tooley, but for the shepherd.’

‘Don’t you dare talk to me like that!’

Mr Tooley was livid with anger. George, seeing his point had struck home, twisted the knife. ‘Oh, it is not me, a humble sinner, talking. I am but the poor messenger of the council of elders, which by the 1646 ordinance …’

Ordinance! As well as proverbs, George was stuffed with ordinances, which listed the scandalous offences of renouncers of the true Protestant faith. Mr Tooley took a step towards George. His fist was clenched and a pulse in his forehead was beating. George did not move away. He cocked his head with a look of sorrow on his face, almost as if he was inviting a blow.

Afraid Mr Tooley would strike him – and afraid, for some reason, that this was exactly what George wanted – I stepped out into the corridor.

The effect on the two men could not have been more different. Mr Tooley plainly saw me as he had always seen me.

‘The prodigal son,’ he said, with a wry smile, holding out his hand.

George bowed. ‘My lord, congratulations on your good fortune. I beg to hope that your lordship realises that, in a small measure, it is due to me not sparing the rod, however much that grieved me.’

There was more of this, but I took the unction as I used to take the blows. I had promised God I would not lose my temper. There were to be no more Scogmans. Diplomacy, not confrontation. I told them there was now no need to name Nehemiah a heretic in church.

‘He has recanted?’ George said.

‘He will be leaving Mr Black.’

‘He’s been dismissed?’

I bowed almost as deeply as he did. ‘I believe people should worship according to their conscience, but the law is the law. Nehemiah will be replaced by another apprentice who will attend church in a proper manner.’

I winced as he clasped his hands and lifted his eyes. ‘God be praised! I shrank from putting Mr Black through so much distress, as I did when I applied the rod to you, but it was for the good of both your souls.’

He put out his hand. It felt as cold and slippery as the skin of a toad. I arranged the baptism with Mr Tooley in two weeks’ time. When I left I still had the clammy feeling of George’s grip. Matthew, the cunning man who had brought me up, would say I had been touched. It was a stupid superstition, but all the same I wiped my hand on the grass.

My spirits rose again when I rode into Half Moon Court. The apple tree was a sad, withered stump, but from the shop came the familiar thump and sigh of the printing press. Sarah, the servant, came out to greet me. She walked with a limp now, but her banter had not changed since she used to rub pig’s fat into my aching bruises.

‘What has tha’ done to master, Tom?’

‘Done?’ I cried in alarm.

‘He’s had a face like a wet Monday for weeks. Now he’s skipped off like a two-year-old with mistress to buy her a new hat for the baptism.’

‘I only talked to him about his problems,’ I said modestly.

‘I wish you could talk to my rheumatism. My knee’s giving me gyp.’

‘Which knee?’ I said, stretching out my hand.

‘Getaway! I know you. Think you can cure the world one minute, and need curing yourself the next.’

She hugged me just as she did when I was a child, then walked back into the house quite normally, before stopping to stare at me. ‘Why, Tom! Tha’s cured my knee!’

I stared at her, my heart beating faster. Perhaps it was something to do with my prayers that morning.

Sarah laughed, then winced at the effort she had made to walk normally. She flexed her knee and rubbed it ruefully, before limping back into the house. ‘Oh, Tom, dear Tom. If tha believes that, tha’ll believe anything.’

Nehemiah was as good as any journeyman, I could see that. He was too absorbed in what had once been my daily task, to see me watching from the door. He was taller than me, and would have been handsome but for spots that erupted round his mouth and neck. It was a hard task for one man to feed the paper in the press and bring down the platen, but he did it with ease.

I wondered why he did not put the sheets out to dry, as he should have done. Instead, he interleaved them with more absorbent paper before putting them carefully in an old knapsack. I gave a cry of surprise when I saw it was my old army knapsack. Nehemiah whirled round, dropping a printed sheet, and grabbed hold of me. I thought I was strong and fit but he twisted my arms into a lock and bent me double. His strong smell of sweat and ink was overpowering. I yelled out who I was. Only then did he release me with a confused apology.

‘I – I did not recognise you. I thought you were a spy, sir,’ he muttered.

I laughed. The Half Moon printed the most boring of government ordinances. ‘A spy. What has Mr Black got to hide?’

I bent to pick up the sheet he had dropped but he snatched it up and put it in the knapsack. I shrugged. While his master was out he was doing some printing of his own. I thought him none the worse for that. Most apprentices of any enterprise did so. When I was going to be a great poet I had secretly printed my poems to Anne on that very press.

I gazed fondly at the battered knapsack, which I thought had been thrown away.

‘You do not want it, sir?’

I shook my head, and he thanked me so profusely for it my heart went out to him, for I remembered when, in my crazy wanderings, it once contained everything I had in the world.

‘How would you like to be a journeyman, Nehemiah?’

‘Very much, sir. I have dreamed of it long enough.’

‘Well then, you shall be. In a few days’ time.’

I smiled at his look of astonishment.

‘But my indentures are not over for –’

‘Nine months.’

‘And twenty days,’ he said, looking at the base of the press, where for the past year he had carved and crossed through each passing day before his release.

I told him he was as skilled as he ever would be and the paperwork was a mere formality. I would arrange it. As a journeyman, his religion would then be a matter for his own conscience. I began to go into practical details, but he interrupted me. He had a stammer, which he had gradually mastered, but it returned now.

‘Has my m-master agreed?’

‘Yes.’

‘It is …’ His face reddened, intensifying the pale blue of his eyes. ‘D-dishonest.’

I told him the rules were dishonest for apprentices – medieval rules, designed to give Guild Masters free labour for as long as possible.

‘What about George?’

‘There’ll be no trouble there. I’ve told him you were leaving.’

‘With-without telling me?’

He began to make me feel uncomfortable, particularly as I thought he was right. I had been high-handed. ‘I’m sorry, but the opportunity arose. And I was worried about Mr Black being thrown out of church.’

‘That would be a good thing,’ he said fervently.

‘A good thing?’

‘He could join the Baptists and see Heaven in this life.’

The idea was absurd. But he elaborated on it with a burning intensity until I stopped him. ‘Nehemiah, Mr Black is old and he’s been in St Mark’s all his life. I’m sorry, but you have to leave. Or go to your master’s church.’

‘Obeying G-George? Like you did?’

He knew the story of how I had struck George and might have killed him if Mr Black had not intervened. Then I had run off. I sighed. Helping him was not as easy as I blithely imagined, particularly when he brought up how I had acted like him – or even more violently – in the past. I walked outside to untether my horse. He followed me, saying he h-hoped he did not sound un-g-grateful – I detected a note of sarcasm in his stammer – but e-even with his journeyman papers he had no position to go to.

I mounted my horse. ‘I will take care of that.’ I told him of a printer who, at my recommendation, would pay him twenty-eight pound a year.

He gazed up at me, open-mouthed. ‘All f-found?’

There was no sarcasm in his stammer now. Money. Everything came down to money. I was a fool not to mention that at first. ‘All found.’

‘Twenty-eight pound!’ he muttered to himself. ‘All found!’ He caught the saddle of my horse. ‘He is one of Lord Stonehouse’s printers. I would be beholden to Lord Stonehouse.’

‘We are all beholden to someone, Nehemiah.’

‘No!’ he cried, with such violence my horse reared. ‘We are not! We are beholden to ourselves!’ He gave me that look of intensity again, then abruptly bowed his head. ‘I-I am sorry. I know I have been churlish, but I have not slept since this business began. I was a fool to think Mr Black would become a Baptist.’ He gave me a wry wincing grin and I warmed to him, for he brought back to me all the torments I went through at his age. ‘I must consult my brethren. And pray.’

‘And sleep,’ I smiled, telling him to give his answer to Mr Black in the morning.

Who would have thought peace was such hard work? It was easier to face cavalry across open fields than try to bring conflicting minds together. But I felt a surge of optimism as I rode past Smithfield on the route I used to take as a printer’s runner. I may have made a great hash of the Challoner business, but I was learning.

Next morning a letter came from Mr Black. Nehemiah had gone. He had scrupulously broken up the last forme, distributed the type and cleaned the press. In the night he had woken Sarah, apologising for taking a piece of bread, which he promised to repay. He put the bread in the old knapsack, with his Bible and a pamphlet whose title she knew, for he had read it to her interminably. It was called England’s Lamentable Slaverie. There was no printer’s mark. It was from a group naming themselves the Levellers. It declared the Commons as the supreme authority over which the King and the Lords had no veto. Also found in Nehemiah’s room was a copy of a petition to Parliament circulating round the army. It asked simply to be paid, to guarantee indemnity for acts committed during the war, and no compulsion to serve in Ireland.

Nehemiah went off at first light, breaking his bond as I had done, years before.

4 (#ulink_b000d4ad-ef63-5861-a49d-9886a0afc221)

It preyed on my mind. What Nehemiah had done was completely stupid. He could have been a journeyman, earning far more than most people of his age, free to practise his religion – what more did he want? And why did it trouble me so much?

‘I would be beholden to Lord Stonehouse.’

That was the problem, of course. He reminded me I was beholden to Lord Stonehouse. Nehemiah was like a piece of grit in bread that sets off a bad tooth. However much I told myself it was nonsense – he could be a liberated slave and see how far that got him – the ache persisted.

Anne knew, as she always did, there was something on my mind, but I refused to talk about it. She would laugh at me, just as she had when I was like Nehemiah. So I whispered it to little Liz and she put everything into proportion. I was beholden to Lord Stonehouse because I was beholden to Liz, to my whole family, to peace.

‘That’s it, isn’t it?’ I whispered.

She gurgled and put out her hand, exploring my face. I laughed with delight, held her up, kissed her and rocked her to sleep. I crept away, stopping with a start when I saw Anne watching me.

‘You never kiss me like that now.’

I bowed. ‘Your doctor has warned me against passion, madam.’

It was true. Liz had been a difficult birth. Anne had lost a lot of blood, and had been bled even more by Dr Latchford, Lord Stonehouse’s doctor. That was one of the things I hated most about being a Stonehouse. I felt like a stallion, not a lover, only allowed to cover the mare in season.

‘Dr Latchford,’ I said, giving her the doctor’s dry, confidential cough, ‘says it is too soon to have another child.’

‘Dr Latchford, fiddle!’ She picked up the mockery in my manner and drew close to me. ‘You’re back,’ she whispered.

Perhaps it was Nehemiah, that ache in the tooth, which made me say ‘Tom Neave’s himself again.’

‘Oh, Tom Neave! Tom Neave! I hate Tom Neave! He is nasty and uncouth and has big feet.’

I choked with laughter. This was exactly the sort of game we used to play as children after I had arrived without boots and she had mocked my monkey feet. ‘How can it be? Tom Neave or Thomas Stonehouse, my feet are exactly the same size, madam!’

‘They are not! Look at you!’

In a sense she was right. I was not really conscious of it until that moment, but since seeing Nehemiah I had taken to wearing my old army boots, cracked and swollen at the toes, but much more comfortable than Thomas Stonehouse’s elegant bucket boots. I slopped about in a jerkin with half the buttons missing and affected indifference to changing my linen.

I loved her in that kind of mood, half genuine anger, half part of our game, teased her all the more and tried to kiss her.

‘Go away! You stink, sir!’

I pulled her to me and kissed her. She shoved me away. I collided into the crib, almost knocking it over. Now really angry, she went to the door. Contrite, I followed to appease her, but the baby was giving startled, terrified cries and I returned to soothe her.

The encounter with Anne roused me. We had not slept together since I returned, but I resolved not to go to her room. Although I mocked Dr Latchford, I could see that, even when she had been out in the garden, her skin did not colour. Her blue eyes had lost some of their sparkle. She loved rushing round with Luke, but she left him more and more with Jane and Adams.

I was asleep when she came into my room and climbed into bed beside me.

‘Are you sure?’ I mumbled.

‘Sssshhh!’

‘Dr Latchford –’

‘Do you want me? Or do you want Dr Latchford?’ She leaned over me and kissed me on the mouth.

There was a violence, a hunger in that kiss that swept away the dry old doctor and all our arguments and fears, swept them away in the wonderful rediscovery of the touching of skin, bringing every feeling crackling back to life until her cheeks coloured and her eyes sparkled. We laughed at the absurdity of our arguments, at the sheer joy of being together.

We were side by side. I began to climb on top of her.

‘No!’

‘No?’

She twisted away and wriggled on top, which seemed unnatural, outlandish to me. I had heard some of the men, in their cups, talking of whores having them like men. I had reproved them, not just for the whores, but saying did they want to wear skirts, like cuckolded husbands shamed in a Skimmington? But, before I could utter a word, she had clumsily but effectively put me inside her. I was on the brink and could not stop, until she gave a cry of pain and pulled back. I checked myself but her nails dug into my back as she thrust me back into her and we came together in a confusion of pain and pleasure. She instantly rolled away and lay panting with her back towards me.

‘Are you all right?’

She nodded and curled up to sleep.

‘What was all that?’

‘Did you not like it, sir?’ she murmured. ‘It’s called world upside down.’

It was a well-worn phrase describing the chaos after the war, vividly illustrated in a pamphlet by a man wearing his britches on his head and his boots on his hands. Now it seemed to have entered the bedroom.

‘World – world –? Who on earth told you that?’

‘Lucy.’

I was outraged. ‘You talk about our love-making with that woman?’

Lucy Hay, the Countess of Carlisle, had been the mistress of John Pym, leader of the opposition to the King. Since he had died, there had been great speculation about who was now sharing her bed.

Anne sat up, fully awake, her gown half off. Her belly was slacker, her breasts full, but her neck was thinner, her cheeks pinched. ‘We talk about how a woman should keep a man when she has just had a child. About what to do when – when it is difficult to, to make love … That’s all.’

‘All!’

She hid her face on my neck and I held her to me. I could feel her heart pounding. ‘We should wait,’ I said half-heartedly. ‘You know what the doctor –’

She pulled away. ‘Wait? I want another child in my belly before you go off again!’

She spoke so loudly and ferociously I clamped my hand over her mouth. There was silence for a moment, then a cry from Liz, broken off by a stuttering cough.

‘I will not be going away again.’

‘You will. I know.’

Liz gave a long, piercing wail. ‘She’s hungry. Could you not go to her?’

‘Women who are in milk can’t conceive. The wet-nurse fed her. Don’t you want another child?’

‘Yes, but when you are well.’

‘I am well.’

I put my hand over her mouth again as footsteps stumbled past the door. I listened to Jane’s soothing, sleepy voice, the clink of a spoon against a pot of some syrup, until the coughing eventually ceased. Anne ran her finger gently down my nose and along my lips. She dropped her gaze demurely. ‘I’m sorry,’ she whispered. ‘I will not do that again, sir, if it displeases you.’

I swallowed. I could not get out of my head the vision of her being above me and began to be aroused again. She laughed out loud at my expression. ‘You’re like a small boy who’s just been told he can’t have a pie!’ As I moved to her, she stopped me with a raised finger. ‘Wait, wait, wait! Promise me you are Thomas Stonehouse, and not that stupid Tom Neave.’

I put on my deepest gentleman’s voice. I enjoyed being a gentleman when it was a game. ‘I am Thomas Stonehouse –’

‘I mean it!’ She clenched her fists. ‘Why do you put on that stupid voice? Why do you quarrel with Lord Stonehouse? You can get on with him so well when you want to!’

‘When I do what he wants.’

‘Please, Tom!’

‘All right.’

‘Promise? Promise you will not quarrel with him when he gets back from Newcastle.’

‘I promise.’

‘Touch the bed.’

When we were children we made solemn vows by touching the apple tree. Now we touched our marriage bed. Being a great lady was as much a game for her as being a gentleman was for me. But for her it was a deadly serious game. I looked at her knotted hands, her earnest, determined face, even lovelier in its fragile, faded pallor. I felt a deep, swelling surge of love for her. Being a gentleman at that moment seemed a most desirable thing to be. No more fighting. Sleeping in my own bed. Or hers. I touched the bed-head.

‘I promise.’

When the letter arrived next morning it felt like too much of a coincidence. I could not believe she had not known, before coming to my room, that Lord Stonehouse was on his way back. But she looked so shocked that I could ever think she would dissemble like that, and said it so charmingly, and was so full of excitement, and fussed so much over my linen and over a button on my blue velvet suit – in short, it was so much as if we had just been married all over again that I was completely disarmed and able to read the letter, if not with equanimity, with more composure than otherwise. Lord Stonehouse, as frugal with words as he was with money, presented his compliments and would appreciate me calling at Queen Street at noon sharp.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/peter-ransley/cromwell-s-blessing/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Peter Ransley

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The price for a country. The price for a King. The price for a marriage. The dramatic story of Tom Neave continues…The second book in the Tom Neave Trilogy, ‘Cromwell’s Blessing’ sees Tom still determined to fight for his principles – democracy, freedom and honour – despite the growing threat to his young family, as England finds itself in the throes of bloody civil war.The year is now 1647. The King has surrendered to Parliament. Lord Stonehouse, to show his loyalty to Parliament, has named grandson Tom as his successor. But Lord Stonehouse’s son, Richard, is also Tom’s estranged father and a fervent Royalist. If the King reaches a settlement with Parliament Richard will inherit…Parliament itself is deeply divided with those demanding a strict Puritan regime pitted against more liberal Independents like Cromwell. King Charles, under house arrest, tries to exploit the divisions between them. When Richard arrives from France with a commission from the Queen to snatch the King from Parliamentary hands, he and Tom are set on a collision course. Caught between his love for his wife Anne and their young son, and his loyalty to the new regime, Tom must struggle to save both his family and the estate.