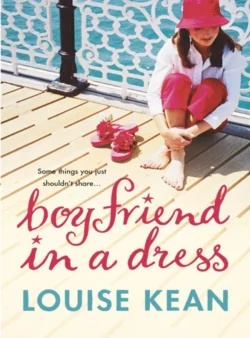

Boyfriend in a Dress

Louise Kean

A novel about cross-dressing, social apathy, and seeing the best in people, a little too late.It started when I came home and found my bloody pointless stupid bastard boyfriend, Charlie, on my sofa, in my blue Lycra dress. He was having some sort of breakdown.It transpired that Charlie had been having an epiphany of sorts. The previous night, standing on his balcony, he had witnessed an attack – on a woman he'd just kicked out of his bed. Ahsen and shaken, on his way to work the next day, he had found a dead body in the train toilets and now here he was, in a dress, sobbing uncontrollably.I had been ready to dump Charlie once and for all – he was an unfaithful bastard (so was I, but not to the same extent). But he convinced me to run off with him to Devon for a week to sort his head out and I decided I owed him that much. Sizzling in the unlikely heatwave that week, everything changed between us, as we sucked on ice-creams naked on deckchairs, and hi-jacked an old people's bowling green. But despite the fact that our relationship had never been so strong and never meant so much to either of us, could we handle what was waiting for us back in London?

LOUISE KEAN

Boyfriend in a Dress

Dedication (#ulink_bf96ba38-6aaf-53d6-8056-92ae18b7d2e6)

For Mum & Dad

Epigraph (#ulink_e047945c-0c39-5dbb-95b3-c6d50a26ab31)

I used to be Snow White … then I drifted

MAE WEST

It takes two to speak the truth – one to speak, and another to hear

HENRY DAVID THOREAU

Contents

Cover (#udd5d11a6-a3b6-565f-ac96-64dd86930aeb)

Title Page (#uab182fe1-7433-58e7-9a71-d0eff0f733b6)

Dedication (#ude92a26c-c227-5469-84bf-c14b69974ae8)

Epigraph (#u97c90682-ab3f-51d4-82a9-a596df13b2fa)

The First Time I Ran Away (#u58a0bb1f-2a92-5ab7-8faa-fcffd7b88f8f)

Amen to That (#uc3753a47-2438-5e54-a5a3-2a0872fca517)

Psycho (#ub8975b50-e49d-57e8-87eb-495cd19774cd)

My Penis Is … (#u55400534-7392-503f-9930-829bbc54d564)

Stripped Bare (#ud6604f5b-51da-5046-8253-11692b877c16)

My Green-Eyed Monster (#u38142b66-ddc6-5b75-bcf4-0711b6d9c04d)

Dressed to Kill (#uc25c18f0-5b2b-541a-b329-6c3ae902a30b)

What Charlie Has to Say for Himself (#ucf899d88-5aee-5c6e-8d3c-ead937a242ee)

I’m With Stupid (#u5f13cc40-8354-5b81-94f4-0101201256c9)

We’re All Going On a … (#u49032879-63ad-574d-9109-20d99e3569e1)

Mind My Decanter! (#u6ec0a7f0-bce9-5004-884a-7cfe9e96d76a)

Bowls! (#u704c7382-718e-565f-be43-728dced25687)

Food for Thought (#u0cf7fa86-64f5-5ef8-8ccd-346518d1ec5e)

Highlights (#u3a32bc3f-81c4-5000-a48b-413600dc6a86)

Swim When You’re Winning? (#u07ed1e8f-e90d-5cea-9ee5-70e7bed8bcb7)

Two Inspectors Call (#u3d0c5497-8b9e-5636-8d9b-fb4b9708326f)

Gone but not Forgotten (#u1a98f6af-d3bd-5f75-b92e-d067d742da51)

Who Cares? (#u0860e9e8-a576-5553-905f-bdf3c5bf1494)

Starting Again (#u0f18781a-90c8-5ff5-980b-5d36290a6a42)

Back to Life (#u1972e004-81cb-5321-94b4-1b825f22c4e5)

Closure, I Promise (#u57e79d62-5bc2-5ae8-a6de-83178be80f0c)

Socrates Says (#u604b04fd-d5b0-551f-9962-d138d84bfad5)

A Date with Disaster/Destiny (#u98da0413-9e11-5ecf-980c-533e1f0a8333)

What’s Wrong? (#u5a7a4f42-9673-581b-bbf6-8d015848f0ea)

Completely Nuts (#uec694796-9ea3-5e3e-8567-4f2bc1246425)

Confession Time (#uf01e32ba-e61a-5472-a36a-1cb8eefac343)

Small Truths (#u410da351-c331-5805-8da4-06bf7257a6da)

Starting Again, Again (#uba4a17c0-5a41-5939-9771-51bdeb529011)

When it Rains, it Pours (#u8e492921-14ad-5022-bbad-615f50796155)

One Step Forward or Two Steps Back? (#u29df46bd-8d78-5c41-b58f-a09e1ca60c2f)

Sleeping on It … (#u090f9924-0f16-59e4-969b-2deb0af66aa7)

Should I Stay or Should I Go? (#u830def47-60db-5af8-a3b0-43e0cb85aeae)

Starting Again, Part Three (#u38c65823-527d-5b74-be38-e12a4f3c5fd4)

Almost Romantic (#ub0082705-c66a-5f7a-b92f-e321e52f9bee)

Perspective (#u8e311f4b-d617-52e8-abf8-76d871eae6b1)

Good Grief (#uf6c1aa0b-9b7f-561e-92ba-faad9ab44ec7)

It Could Be So Different (#u82b359bc-a53d-538b-96cc-3f4cc5254f07)

Doing the Maths (#u16c60641-bec3-5f93-9c25-43d5a38990d2)

What is There to Think? (#u8743bd78-332d-59bc-a5f6-3957f3cbeccf)

Epilogue – After All That (#u1ff8d50c-9adf-5401-85a6-a230a83cb451)

Acknowledgements (#u64e91269-4ec2-5acd-992d-82504e980bc0)

About the Author (#uc490b6ba-4eec-59f8-ac3b-b7c889e104e4)

By the Same Author (#ua1e07d41-d3db-5cd9-82cd-1eb4b9a19af0)

Copyright (#u8e6bed28-6da0-502e-80c0-cdf1345724a2)

About the Publisher (#ubad42fe1-9dce-5037-a5ee-9d18097a3e91)

The First Time I Ran Away (#ulink_7dcdbd61-9e8f-5467-b044-e74ae940ba24)

‘I’m sorry, what?’

‘We should just know zat ze ghost is zere, we shouldn’t be able to see it! ’Ave it taken out of ze script. Get somebody else to do it. Sack ’im first.’

You can barely even make out the Spanish accent now, although when my boss first came to this country two years ago, when he first took the job as the head of television development, it was actually impossible to understand three out of four words he said. He told me six months ago, through a toothy Spanish smile, that he swore a lot in those early days, at all of the producers and scriptwriters he worked with, and got away with it. I know that is a lie. He thinks it ingratiates himself with me, with ‘the team’. We know that he would eat his own hands if it pleased the producers. José isn’t fooling anybody any more. It only takes a couple of months for the political animal to show its face.

‘José, I can’t just sack him, I need a reason.’ I don’t know how many times I have had this conversation with him. He still cannot grasp the fact that somebody has to do something wrong before you give them their marching orders.

‘Look at ’iz ’air! It is all wrong. ’E ’as to go!’ José thumps the boardroom table violently.

‘You want me to sack him because of his hair? I don’t think hairstyles are specified in the contract, José – besides, what’s wrong with his hair?’

‘Oh, everything. It is so … so British. ’E ’as no flair.’ He sighs wearily. I too am British, I will never understand. José has slicked back black hair. That apparently is the hair to have.

‘José, why don’t we just ask him to rewrite, if you don’t like it, but in all honesty, I have to say I don’t know how we are going to make the sequel to Evil Ghost without an actual ghost.’

‘Yes, but zis is for TV, it is very different, Nicola.’

‘I know, we’ve got a tenth of the budget.’

‘I cannot work like zis,’ José says, as he holds his head in his hands.

‘Look, why don’t I just tell him to make the ghost a bit more … subtle.’

‘Yes, maybe zat will work.’ José comes alive again.

‘Tell ’im it should be more like … more like a big gap.’

‘Just a big gap,’ I repeat, although I know I am pushing my luck, but it’s just such a stupid thing to say. We are not a TV company who lets our audience ‘sense’ anything any more. If you can’t see it, in all its graphically-enhanced, action-packed splendour, it ain’t us. Subtlety went out with the sequel. And promotional tie-ins. Both of which we are very good at, I might add.

‘Zat’s what I said.’ The toothy grin is warping into gritted teeth.

‘You don’t think we might need to be a bit more blatant than that? You don’t think we could show something a bit scarier than … a big space? You don’t think it will just look like we had no budget and ran out of money before we could do the effects?’

‘No, it will intrigue zem.’

‘You think it will intrigue young males, fifteen to twenty-five, our primary audience?’

‘Zee audience are more sophisticated zan you give zem credit for, Nicola.’

‘Fine.’ The only thing he can’t do in a perfect English accent now is any word beginning with ‘th’ or ‘h’. It kills him, I know. But I give up. I will be told to change it eventually, or be ultimately blamed myself for the idea of leaving a big ‘space’ in our TV movie, if it ever actually makes it onto TV, probably cable at this rate. Play the game, I remind myself, as I click my pen, and write in large letters on my notepad – LEAVE A BIG SPACE. I massage the side of my head slightly, and try not to project ‘attitude’. José stares at me pointedly, daring me to tell him what an idiot he is, but I don’t bite.

‘Maybe a big space is going too far,’ José says, and I realize he is coming to his senses.

‘’Ow about a cloud of white fog instead. Try zat.’ He smiles at me. I smile back. It’s obviously happy hour at the idiot farm.

‘A cloud of white fog?’ I ask, trying not to sound numb.

‘Yes, like a mist.’ He makes a circular motion in front of him with his hands, and then nods at me to somehow ‘write that down’.

‘You want me to tell him to write a mist in. What kind of mist?’

‘A ghostly mist.’ Jesus wept!

‘Look, it’s called Evil Ghost 2: The Return. We need a ghost in it. Come on, he’s doing a good job. If the script is lacking, maybe we need another character or something. Maybe there’s something wrong with the second act.…’

‘Yes! We need … we need … something sinister – who are sinister? Work with me, Nix, work with me … the old, the old are sinister, if zey ’ave lost zer teeth … An old lady mist! It should be an old lady ghostly mist,’ he shouts, his personal Eureka. We have been doing this for over an hour.

‘An old lady?’ There are no old ladies in our script.

‘Yes, shoot it tomorrow, get me a visual, I know it will work. You can use Angela! It will be cheap.’

‘José, we can’t use Angela.’ Angela is his PA.

‘Why not?’ He looks at me, confused.

‘Because she’s thirty-nine. She might be offended.’

‘Thirty-nine? She looks older zan zat.’ He looks down solemnly; I have burst his bubble. José only employs young women, and by young, I mean under twenty-five. Luckily, Angela and I were here before him, and he hasn’t sacked us yet. I’m twenty-eight, but that is middle-aged in José’s book.

‘So?’ He looks at me expectantly, waiting for a solution. By my side, Phil, my assistant, has a blank look on his face that lets me know he has been asleep with his eyes open for the last half an hour.

‘Okay, I’ll drop in an old lady, a proper old lady – she’ll be like, eighty, José.’ He practically retches at the thought.

‘I’ll have it worked up by the designers, so we can see how it looks.’ I surrender, trying to draw the meeting to an end.

‘No, organize a shoot. I won’t attend.’ There’s a surprise.

‘You want me to organize a shoot – for an old woman in mist?’

‘Zat’s what I said.’ I’m going to get told off after this meeting. I’m being ‘negative’.

‘But it’ll cost twenty times as much as just working it up on the Mac.’

‘Yes, but it ’as to be realistic.’ He gives me a patronizing smile.

I sigh, as José sucks on a biscuit with a smile.

‘Set it up for tomorrow. I’m in Spain on Friday,’ José says through a mouth full of Digestive.

‘Tomorrow? But it’s five-thirty now!’

‘Nicola, ’ow ’ard can it be? It’s just mist, and an old woman.’ He smiles at Phil, and raises his eyes to heaven at me. Phil doesn’t respond.

‘We’ll have to get a smoke machine.’ I nudge Phil, whose pen darts towards his pad, and just draws a line.

José thumps the table with his hand, and looks straight at me.

‘No, for fuck’s sake – it ’as to be realistic for fuck’s sake!’

‘But we’re in the middle of a heatwave; where am I supposed to find mist by tomorrow?’ I ask coldly, trying not to lose my temper.

For emphasis, I wipe the beads of sweat off the back of my neck, and blow a hair off my cheek that has stuck.

‘I’m sure you’ll find a way.’ José regains his composure and smiles at me again, through gritted teeth. He hasn’t broken a sweat for the last two weeks, in the middle of this freakishly hot May. The man is ice. You could pour vodka down his ear and watch it come straight out of the other end, with your mouth open beneath what I am sure is a below-average length penis, while everybody cheers and claps. I am left with a horrible mental image. If it wasn’t eighty-five degrees outside, I’d shudder.

‘Are we done zen?’ José asks cheerily, and pushes back his chair.

‘I suppose. So for now, the scriptwriter can stay?’ I say, as confirmation.

‘Yes, but tell ’im to cut ’iz ’air.’ José pulls a face, and saunters out without a care in the world.

I nudge Phil again – his pen darts towards his pad and underlines the line he made earlier.

‘Phil,’ I say, losing my temper.

‘Wha?’ he says, as his eyes desperately try to focus.

‘I’m going for a cigarette. Go downstairs and conference in Naomi and Jules.’

‘Your mates?’ he asks, confused, even though he has done it a thousand times before.

‘Yes, you have their numbers. I’ll be back in five minutes.’

‘Get me a Twix,’ I hear him shout after me as I head for the lifts.

I sigh and hit the button for ‘ground’, and try desperately to ignore the mirrors on all sides of me in the lift, reflecting my shiny face back at me. It is too hot for May. I love it and hate it. If it holds until the weekend, I’ll love it. If it breaks on Friday, it’ll just be a pain in the arse. There is nothing worse than working in the summer. Actually, there are a lot of things which are much worse – torture with acid and sandpaper isn’t great, I’ve heard – but this is … frustrating.

I lean against the side of our building, with the sun pouring onto my eyelids, and inhale.

I was fourteen, dressed in my school uniform, and hiding behind a petrol pump. My exasperated parents drove up and down the road in front of me. I could see the car crawling back past the church, past the petrol station opposite. I didn’t want to go to my first confirmation meeting. My friends were all at the cinema, but I was ducking behind the four star. After too many arguments to go into, I had succumbed to being driven to St Jude’s, our church, because my parents didn’t trust me to get there on my own. I waved at them as they pulled away in our old Orange Datsun that my mum swore had ‘character’, and walked up the few steps to the door, but didn’t ring the bell, waiting for the car to recede into the distance so I could make a run for it. But the door suddenly flew open, and Sister Margarita sprung out of nowhere, grinning like the village idiot: she’d been at the holy wine … again.

‘Jesus Christ!’ was my unfortunate cry of shock.

‘Nicola Ellis!’ she managed to slur back in mock outrage – she’d heard worse, hell, she’d said worse herself, but she was obliged to at least seem offended.

‘Sorry, Sister,’ I mumbled and made a break for it. I dashed off down the steps, and stood, half excited, looking both ways deciding which new path to follow. Which is when I noticed the mobile baked bean tin handbrake turn at the end of the road, and suddenly my mum and dad were on my tail like the Dukes of Hazzard hit Kent. I managed to make it to the petrol station before they drove past – my dad may have been angry, he may even have done an illegal turn, but he wasn’t going to do more than thirty in a built-up area. So I ducked and dived as they went along and their sixth parental sense stopped them driving off in the other direction. They were going to track me down. It was a matter of principle, and it would make my nanny happy.

As they cruised past the church again, looking like a pair of terribly respectable kerb crawlers, I found my feet and dashed off in the other direction. The Datsun caught me as I sprinted towards the park, and I heard my mother’s voice say wearily from behind a wound down window,

‘Nicola, get in the car, please.’

There was no point fighting it. For me the compulsion to run has always been there, but when I am caught, as I am always caught, a tidal wave of guilt at doing what I want to do manifests itself in a desperate need to make amends. My dad walked me up the steps and rang the doorbell to the nuns’ house, as I hung my head in shame.

‘Don’t run off again – it’s getting dark, it’s not safe,’ was all he said. And I obeyed. Sister Margarita swung open the door again, still smiling like she had a Wagon Wheel stuck in her mouth. At the sight of me she managed to say,

‘Blasphemer!’ covering my father in a shower of holy saliva.

‘Sorry, Sister,’ I said again, as my dad eyed her nervously, and wiped himself off. Her cheeks were purple and riddled with veins, and her nose was bright red, her wimple lopsided, with an ear popping out of one side.

‘I’ll pick you up in an hour and a half. Be here,’ my dad said, and kissed me goodbye. I waved to my mum, who waved back, smiling that it would be okay. So I end up doing the thing I’m running from anyway, just with the added bonus of feeling like a bad person for daring not to please somebody else. I was the only latecomer, but I was already feeling guilty, so I was instantly top of the class.

I go back upstairs, and throw the Twix at Phil on my way past his desk, and he catches it with cricket hands and cries ‘Howzat!’

Phil follows me into my office mumbling ‘not out!’ as I slump at my desk.

‘We should throw more things in the office, it brightens my day,’ he says, and lingers near the door.

‘Are they on?’ I ask, ignoring him, looking at flashing buttons on my phone.

‘Yep, they’re holding. Is Naomi the fit one?’ he asks seriously.

‘They’re both fit, they’re my friends,’ I reply, wearily.

‘Yes, but not girl “they are both lovely and funny” fit, bloke fit?’

‘I wouldn’t know,’ I say, and hit the red button and mouth ‘shut the door,’ at Phil, who slumps out of the room. He really would prefer just to sit and listen to my conversation for twenty minutes.

When nothing happens – I can’t work this damn phone, it’s like something out of Star Trek – I press the button again, and instantly hear the girls talking at the other end.

‘Oi, I’m here,’ I say, and press some buttons on my keyboard, checking new emails for anything important.

‘“Oi”? How rude is that? She keeps us waiting, and then says “Oi”!’ Naomi is indignant.

‘Sorry, hello, I apologize for my lateness, I was in some stupid bloody meeting for hours, at the end of which we established we are going to put an old lady in fog to scare people.’

‘Like Last Of the Summer Wine?’ Nim asks.

‘Yes, just like that. Are we still on for tonight?’

‘I am, but I’m going to be late. I have to meet the Countess of Wessex.’ Jules is a fundraiser, she keeps meeting royalty; we don’t ask why.

‘What time are you going to be finished?’ Nim asks.

‘About seven.’

‘Cool, that’s good for me,’ I say, turning my attention to the photos on my desk that have been sent through by our agency of young wannabes to play our leading man. They are all useless. I wanted gritty and urban, I’ve got sons of Lionel Blair.

‘Shit, I’m finished at six, what am I supposed to do for an hour?’ Nim works in the City, meaning she works normal hours, unlike myself and Jules, who chose ‘interesting’ careers, instead of being well paid and working sociable hours. Nim has both, and even though she has to put up with banking arseholes all day, she has pots of cash, and wants to go out every night. I have to talk to her about that. I don’t want her to end up like Charlie.

‘Shop, write personal emails, go to the gym, whatever,’ Jules is saying at the other end of the phone.

‘I should go to the gym.’

‘Well, there you go, do that,’ I say, as an email entitled ‘Play this now!’ flashes up from Phil. I open it, distracted, and try and smack a monkey with a hand as fast as I can by pulling back my mouse and then whizzing it across my desk.

‘So seven? Dinner or drinks?’ I say, as I swing my mouse into my in-tray, sending papers flying everywhere, and swing it back.

‘Shit, hold on.’ I find and press hold, and shout out for Phil, who opens the door seconds later,

‘Phil, what’s your fastest smack?’

‘Four hundred and thirty-six miles an hour,’ he replies, and wanders over to stand behind my PC.

‘Bloody hell,’ I say and pull my mouse back, determined to beat his score. I whack the mouse and a tune plays and the computer declares I have smacked the monkey at five hundred and two miles per hour.

‘Shit,’ Phil says, and grabs my mouse from me, and has a go himself, as I press hold again.

‘Sorry, did we decide?’ I ask.

‘Yep, drinks and dinner, Café Bohème,’ Jules says.

‘Cool, I’ll see you later.’

‘Can I bring some guys from my office?’ Nim asks.

‘Who?’ Jules asks suspiciously, knowing full well that she doesn’t want to run into at least two of them.

‘Neither of them,’ Nim pre-empts her.

‘They’re nice,’ as some sort of explanation.

‘And they work at your office?’ I ask, incredulous. I know some of the guys who work with Nim; they know Charlie.

‘Yes, some of them are nice.’

‘None that I’ve met,’ I say.

‘They’ve just started.’

‘Oh, okay, cool.’

‘See you later then, I’ve got to go,’ I say, as I see Phil smack the monkey at six hundred miles an hour.

‘Cool, byeeeee,’ we all squeal off the phone, trying to go higher than each other.

‘Give me that.’ I grab the mouse off Phil, who is looking smug. I smack it a couple more times, but can’t beat his score. He strolls around to the front of my desk, wipes the sweat off his forehead, and throws himself into a chair.

‘Are you going out with them tonight?’ he asks, the picture of innocence.

‘Yep.’

‘What time?’

‘Seven.’ I start going over the photos again, trying to see past the crowned teeth and sunbed tans.

‘Can I come for a couple? I’m meeting the boys at eight.’

‘Yep,’ I say, and then, ‘these are shit.’ I throw the photos across my desk, lean back in my chair, and sigh. ‘What time is it?’

Phil checks his watch.

‘Ten to six.’

‘Have you got any more games?’ I ask wearily.

‘Of course, but aren’t we supposed to set up that shoot or something?’

‘Shit, SHIT, yes! Well done! Call Tony, get him on the case. I’ll make some calls.’

I grab my numbers.

‘What exactly am I supposed to ask him?’ Phil hasn’t moved from the chair.

I look at him and feel bad at the prospect of making him work hard for the next hour. ‘Don’t worry, I’ll call him.’ I plug the number into my phone, as Phil closes his eyes in front of me, deciding it’s time for a well-earned nap.

‘Out,’ I shout at him and point at the door.

‘Alright, darlin’.’ I hear Tony’s Scouse greeting on the hands free and pick up the receiver. ‘I was just about to leave – whattdaya need?’

‘Tone, I need a massive favour, hon. A shoot tomorrow. I need mist. For Evil Ghost 2.’

‘Not a problem, you tell me how much.’

‘And an old lady.’

‘Eh?’

‘I need an old woman, but I’d rather not pay for her, I haven’t got the cash. Is there anybody that you know – how old is your mother?’

‘Not old enough, I’m from Liverpool, remember.’

‘Of course, she’s probably younger than me.’

‘Pack it in.’

‘Okay, but you have to find me some old dear, preferably one without her own teeth, who’ll work for a hundred quid tops tomorrow morning.’

‘Not a problem, darlin’.’

‘You are a star.’

I go over the details with Tony for the next twenty minutes, try my best to discuss last night’s Liverpool game with him without sounding bored, make some more calls, and then head for the toilets to sort my make-up out. I catch Phil chatting to the boys at the end of the corridor, playing imaginary cricket shots and laughing. I don’t bother telling him to do what he should be doing: actual work. I’m done for the day.

At seven Phil and I wander up the road into Soho, dodging tourists and drinkers, completely oblivious to the pace at which everything moves around us, or the gulps of steaming pollution-filled air we are inhaling. It is still hot, but becoming bearable. The restaurant is cool inside, and Nim is already at the bar. I kiss her hello, and Phil looks like he wants to do the same, but she turns back to the barman.

‘What are you having?’ she asks over her shoulder, while gesturing with a twenty-pound note at the young French guy behind the bar with a mole on his cheek that looks like eyeliner. These are vain days. Everybody’s caking it on, and moisturizing themselves into a slippery mess that enables us to slide past each other down the street. I can’t remember the last time I saw a real spot on anybody I actually know. Strangers have them, but they don’t count. Hell, even Phil hides his blemishes now. I had to buy him blackhead strips from the chemist because he was too embarrassed to buy them himself. It used to be condoms. The world is spinning differently these days.

‘Dry Martini,’ I say.

‘Phil?’ she asks, as he shifts uncomfortably, about to reach for his wallet.

‘Oh, I’ll have a pint of Stella, thanks.’

‘Did you go to the gym?’ I ask, over her shoulder at the bar.

‘No, played some monkey-slapping game and then came over here.’

We sip our drinks, and I catch Phil staring as Nim takes her jacket off.

‘I don’t know how you work in a suit in this weather,’ I say as a distraction.

‘It’s not so bad, the blokes aren’t even allowed to take off their ties,’ she says, and sips her gin and tonic.

Phil is chatting to the guys from Nim’s office about last night’s Liverpool game. I could join in, but I’ve done my football talk already today. The boys wear make-up and the girls know the offside rule. Mostly due to the fact that the footballers seem to have got better looking, and the boys need to look like them to get a girlfriend. The icecaps are melting – the sea is the only thing today that is growing less shallow.

‘How’s work?’ Nim asks.

‘Shit – you?’

‘Boring,’ she says, and we move onto more interesting topics.

‘How’s Charlie?’ she asks eventually.

I turn my nose up, but say ‘fine.’ We move on again to more interesting topics.

Jules turns up late, and we are seated at our table.

Two hours later, we are lashed on some new cocktail one of the guys from Nim’s work has introduced us to. But it’s the tequila that really pushes us all over the edge – the implication that we got drunk by mistake on some new and peculiar concoction is a lie. We wanted to get drunk, so we drank tequila. There are no real mistakes any more, not where losing yourself is concerned. In every other facet of your life maybe, but the pursuit of oblivion is a knowledgeable one. Nobody is snorting that coke for you. Phil has completely forgotten about his mates, and is falling asleep at one end of the table, while Nim shrugs his head off her shoulder. The whole place is giggling in the end of the day heat, and I start to think about going home. We kiss our goodbyes outside, making the responsible decision not to go dancing on a school night, and Nim’s mates help me put Phil in a cab back to his grandfather’s house in some leafy south-west London road where car insurance is still affordable. I walk to the tube with one of them, Craig, who is a few years younger than I am.

‘So, Naomi tells me your boyfriend works around the corner from us.’

‘Yep, at Frank and Sturney, he’s been there for a few years, started there straight out of university – like you,’ I say, and hope to hell that this sweet, funny, young guy doesn’t turn out the same way.

‘Are you enjoying the job?’ I ask, at the same time as he decides to ask for my number.

We stop outside the tube and look at each other uncomfortably.

‘I don’t think so,’ I say, and he looks down at his smart City shoes, embarrassed.

I lean forward and catch him with a kiss, and he is surprisingly quick to react and kiss me back. As we stand on the street, kissing, I feel his tongue and his breath, and let it drag me back five years, out of London, into the country, onto a campus, surrounded by friends. It is a young kiss, not cynical, not dirty, but the kind of kiss you got at the end of the night back in the days of lectures, of drinking all day on a Wednesday, and taking your washing home to your mum.

‘That’s just because of the sun,’ I say, as I pull back and smile, remembering I have grown up since then. He smiles back.

‘Are you sure?’ he says, all of a sudden the confident young City thing, stepping into a new world of arrogance fuelled by an ever-growing bank account. He will turn out like Charlie, they can’t help themselves – it’s a breeding ground, almost a social experiment.

‘Yep, I’ve got … Charlie.’ The words ‘relationship’ and ‘boyfriend’ stick in my throat and refuse to come out. Neither my head nor my heart will let them.

I sit on the tube home, drunk, and try not to get upset. I only ever let myself get really upset when I’m drunk. My head flops from side to side, and the heads of all the other drunk people around me, opposite me, do the same. The middle-aged couple who came up to town to see a show squirm in their seats in the corner, and pray they won’t get leaned on, making mental notes not to come again until at least Christmas. It’s our city now, us drunk young things on the tube late at night, it stopped being their’s years ago, when people started to ignore the beggars instead of acknowledging them with a turned-up nose or an incensed disgusted remark. Nobody says anything any more. They are as much a part of life as Switch and internet shopping.

I phone Nim as I get off the train, staggering in the dark towards my flat.

‘Why are you crying?’ she asks straight away.

‘I’m just being stupid,’ I say as I wipe the tears away from my face, and try to stop them reappearing immediately in the corners of my eyes.

‘It must be something,’ she says, and I can’t help myself saying something stupid.

‘I’m alone, aren’t I!’

I hear Nim laugh slightly.

‘How melodramatic, Miss Ellis. Besides, you have Charlie.’

‘I don’t “have” Charlie at all. We just keep going, like the Queen Mum. But even she died in the end.’

‘Well, then do something,’ she says.

‘I will, thanks, hon, I’ll speak to you at the weekend.’

I fall through my front door, and into bed.

I should do something.

Amen to That (#ulink_6f19541d-a3c9-5631-8bab-58759eabf857)

When I was sixteen a kiss was a wonderful thing. The mere idea of pressing my open lips to some boy’s mouth lit a fuse of excitement within me that sizzled its way through my bloodstream, and I could only imagine the joyride that would follow when I realized what to do with my hands. A kiss was a great step forward into the world of people who drove cars and owned their own houses and had babies. I was still learning, still believed I could somehow ‘do it wrong’. A kiss was enough for me then. It was the world.

At twenty-eight, a kiss just never seems to be enough. Today it’s all about sex. I have sex because I can, I am allowed, I have that house, I drive a car. I know that nice girls only kiss on the first date, but the whole notion of being a ‘nice girl’ is relegated to my teens, when it passed out of my consciousness, and I realized I was perfectly within my rights to go further than that without stigma, because stigma was just sexism, and I am a liberated woman. That’s my excuse at least.

Sex can be many things, and about many things. It can be animal, fatal, it is political, natural, it is a weapon, it is illegal in some countries, it is about control: there is even some particularly vicious propaganda out there that says it is something to do with love. It is easy to become obsessed with it, and its emotional effects, and the physical realities it can leave behind. I live in a world obsessed with something it still finds it hard to talk about. Religion stamps its ugly muddied footprints all over the sex act for so many of us, and it is this notion that true love waits that muddles my subconscious time and time again. The very fact that I should postpone some random physical act for three weeks because then I will know that it is ‘right’ makes a rebel of me. Do anything too soon and you are cheating yourself, you have low self esteem, you are desperate, you are, in a word, a ‘slag’. I don’t want those rules to apply to me, but still I feel them hanging over my head like the ‘snood’ my grandmother knitted me when I was fourteen.

I’ve realized recently, as you’ve probably already guessed, that a good Catholic schooling has affected me more than I previously thought. I never labelled my hang-ups before, but now I do and I name them ‘convent school’. Guilt is like a sperm stain on a suede skirt – it shouldn’t be there, you want to get rid of it, but even dry cleaning won’t get it out – basically, if you want to keep wearing the skirt, you’re stuck with it. You can try to ignore it, but accept that it is always going to be there, making everything not quite perfect.

I feel guilty about everything – about the big things and the small things, the things I haven’t done, the things I should have done. Rationally, I know I should really focus on the actions of my hooded teenage tormentors rather than their words.

The nuns mostly seemed angry, and I seriously believe it was due to their ‘lifestyle choice’. Their major release of emotion, as far as I could see, was belting out a good hymn. Now I can only manage to hit a high ‘C’ with a little help from the man of my choice, and yet they manage it most days in church, but I honestly doubt we’re feeling quite as good when it happens. Although it’s very possible that there are ‘nun exercises’ that compensate for their chastity and produce the same ‘reaction’ – you can probably even buy the video in Woolworth’s – it’s why they are always so keen to sing everything an octave too high. Bless ’em for trying, I suppose. You’ve got to get your kicks somewhere, and one bonus is that they don’t get itching diseases their way, or mild concussion from an unforgiving headboard.

But their frustration, or restraint, or choice, or whatever it is, has had a knock-on effect. They managed to get to me at a particularly vulnerable stage in my mental and emotional development, and even though I personally have chosen to pursue a life where sex is allowed, I still feel guilty about doing it the first time, the next time, too many times with too many people, not loving the one I’m with. I can’t help feeling that if only somebody had p-p-picked up these penguins once or twice, I’d have a much healthier sexual mindset now.

And even though I can admit that, with regard to this particular incident, the incident in question, the sex itself isn’t the only thing I have to feel guilty about, and that there are feelings and emotional repercussions that weigh just as heavily on my mind, it is still a big part of my guilt. No need to hide the truth from everybody, including my mother, but most importantly, Charlie. I could have been so much happier. But I can’t change it now. This is me.

You wouldn’t know to look at me that I am so terribly mixed-up – my hair is long, my eyes are brown. I burn first, then tan. I stand five feet seven in bare feet. I look perfectly normal, perfectly average. I don’t know my vital statistics. This is the measure of me, I suppose.

I like ordinary things: red wine, whisky goes down smoothly, Martinis the most. Lychee Martinis are my favourite – swollen with vodka like a juicy alcohol eyeball.

I like to go dancing, any kind. I have a few drinks and do stupid things. Once at a summer barbecue in the garden of one of my friend’s houses, as we all fought the chill and the need to go inside at nine p.m., I tried to do a front roll over a piece of plastic cord that had been hung between a tree branch and some guttering as a makeshift washing line. We had been drinking since three. It was positioned over paving stones nearly two metres off the ground. I got halfway over and the cord snapped. I fell face down onto the paving, and chipped my front tooth. I still have a lump on the back of my head from that one, which I should probably get checked out. The tooth got fixed the next day obviously; you can see that.

I wake up early the next day, another wild warm day when you feel like big things are supposed to happen. The sky is bright blue, even at eight in the morning, dusted with fairy-tale clouds, and the air already smells of cut grass – the community servicers have been out early – and I fight the urge to have ice cream for breakfast.

I wake up on my own. I spend the first twenty minutes breathing in the heat and the sun and the silence. The phone doesn’t ring, I am left alone, the way it should be on a day like this. Everybody is praying for something to happen to their lives, to whisk them away on the sunshine express to a much better time.

Instead of ice cream, I light a cigarette, and hang over my balcony which overlooks the communal gardens that nobody uses, in case they have to sit twenty feet from somebody they don’t know. A breeze creeps up, and everything sways, including me. A spider stuck in the middle of its cobweb rocks to and fro, and seems to enjoy it, and the hairs on my arms search up for the sun. I feel it, where I always feel it, in the small of my back, and the heat closes my eyes, and I dream, standing. I breathe warm air, think I hear music somewhere, not here. It is a small bliss. It is a beautiful day. I know something should happen today. It makes me feel giddy. I should do something. This thought snaps me back to reality, and the moment is gone.

‘I don’t want to go to fucking work,’ I complain to myself, in a staccato voice, accentuating every word, as if somebody, God, maybe, might hear me and say ‘that’s ok, you don’t have to – take your passport and run away!’ It doesn’t happen, nobody says anything to me, and I sigh, facing the inevitable, and move back into my flat to get dressed.

The doorbell buzzes while I am pulling on yesterday’s jeans, having the age-old footwear debate in my head as I look at my strappy sandals sitting prettily next to my starting-to-reek trainers: longer legs, or still being able to walk by lunchtime?

‘Package for you,’ my intercom says.

‘I’m coming down.’

I button up my shirt as I run down the stairs. The delivery boy is waiting by the door – a kid really, maybe five years younger than me, but a world away. He looks like he has fun in the evenings. He likes his job in that it gives him no hassle, but it is the evenings that are his. A young black guy, good-looking and charming. He smiles, I smile back.

‘Do you need me to sign for it?’

‘Nah, it’s fine.’

He walks off as I shut the door, saunters back to his van. He looks like he gets a lot of sex. He looks like he has them queuing up. You can tell he is good in bed, in a young excitable way.

I thought my parcel would be from the book club, but it’s not. It’s the organic meat my father keeps ordering for me and having sent directly to my house. He is worried about contaminants, about what they put into beef these days. If I refuse to become a vegan, like my dad, he is going to keep ordering me ‘clean cow’ as Charlie calls it, which just makes me want to chuck it straight in the bin. Somewhere deep inside of me I know I don’t want to eat meat any more. If Charlie calls our bacon sandwich ‘pig’ I retch. I can’t eat the animal, and hear or say the animal’s name at the same time. Unfortunately I just really like the taste. It’s yet another issue I’m avoiding, I know, but today isn’t a day for confrontations, especially with myself. I just put the meat in the fridge, in the knowledge that it will probably have gone bad, organic or not, by the time I get around to cooking for myself in my own flat. Cooking for one demands minimal effort, and therefore the use of either the toaster or the microwave, and I don’t think I can put steak in either of them. Of course I don’t know for sure.

My neighbours are out now, going to work, going to the shops. I say good morning to a couple of them, the older ones. I smile at the young guy who has moved into the flat on the first floor. He is tall and broad and looks like he does a lot of sport. He is wearing a suit, which puts me off slightly, and swings a gym bag by his side. He will work out today, at the gym at work, with the other City boys, but in his own little world, picturing his muscles expanding with every bench press. I can picture his lungs, clean and clear, the little hairs swaying, not tarred and blackened like the anti-smoking programmes show me mine will be by now. He’ll sweat a lot, maybe get a little red in the face, exactly the look he’d have after sex; not that I know.

Walking is only ever a pleasure for me on a day like today, with the sun out and sensible trainers on my feet. Today is a day to smile. The man on the fruit and veg stall by the station makes a remark about melons, which I choose to ignore, my bubble will not be burst this early at least, if at all on a day like today. If I could just wander around all day, in my comfortable footwear, getting a tan, smiling to myself and not having to talk to anybody I know, it would be heaven. But I have to go to work. And even if I manage to make it through the political minefield that has become making TV programmes for a living, it won’t last. Tonight I am going over to Charlie’s, and I will cook for us both, and sit out on his much bigger balcony – with a glass of wine afterwards. It’s amazing how easy it is to ignore a problem. You just don’t say it, and it doesn’t matter. I’ve done it for years.

I was going to do something. I decided, somewhere in my sleep, to talk to Charlie about us, but on waking, today doesn’t seem to be the right day. I just want to enjoy it. I want the entire day to go without a hitch, without a raised voice or argument. Maybe I’ll leave it and talk to him next week. I’ve been seeing Charlie for nearly six years. I met him in America, but we are both British. It’s not working out. It’s more than a bad patch …

I work in Covent Garden – it’s a lovely place to be based, apart from all the fucking tourists. I know that might seem a bit strong, but I am smacked by an oversized rucksack at least three times a day, just walking from the tube to work, and back again.

By the time Tony arrives to drive us to the shoot in a studio in Islington, José has still not turned up at work. He’ll think I was running late and went straight to the shoot, which pisses me off, so I send him a quick innocuous e-mail, asking him when the video for Evil Ghost, the original film, is due for release, so that we can tie up our TV sales. We haven’t even made the film yet. This is the way that it works. By the time we get around to actually making this damn sequel we are going to have about six weeks to finish the thing. We have been teaser trailering for months on the front of all our other videos. And the thing isn’t even made. The marketing comes first, then we film. I don’t know my job title exactly. There are only thirty of us in total. We do a lot of everything, masters of all trades.

I am left to direct the shooting of the foggy woman myself. She is very sweet, actually – Tony hung up the phone after he spoke to me last night, and caught the first bus he saw. He spoke to three OAPs before he found us this one. She is grateful for the money – she lives on her pension, and after Tony proved he was legitimate, and I don’t ask him how he did this, but it had something to do with carrying shopping and playing gin rummy at her ‘Home’, she agreed to come along. She asks if she can sit behind the fog machine, because her legs aren’t as strong as they used to be, and I almost feel bad saying no, she has to stand. An old woman sitting in a cloud of smoke just doesn’t scream ‘horror’ to me.

To be honest, there are only so many ways you can shoot it. But the day itself will still cost about five grand. Tony and I spend most of the time sitting outside on the steps of the studio, smoking cigarettes and eating the muffins that were supplied by some eager beaver production assistant keen to impress the television lady. It embarrasses me slightly – I am not quite so impressed with myself. Not fresh muffin impressed. My phone rings, and I check the number before answering – it’s Phil.

‘Yep?’

‘Nicola, it’s me,’ he says.

‘I know, what’s wrong?’

‘There’s a problem with the teaser trailer.’ He sounds panicked. It’s rare to hear him this worried, which panics me.

‘Oh what now?’ I ask, and close my eyes, ready to concentrate on today’s catastrophe.

‘Somebody has called it porn.’

‘What?’

‘It’s been put on the front end of the new Bristo theBadger videos, and some mum has written in and called it porn.’

‘It’s what?’ I say again; I don’t know why, I heard him the first time.

‘Somebody’s put it on the new Bristo the Badger video and José’s going mad. He says it’s your fault. And then he asked if you had got me to send him an email from your computer this morning. I said no.’ Phil goes quiet at the other end of the phone.

Evil Ghost: The Return is going to be the equivalent of an eighteen certificate for television – it will be strictly post-watershed. Needless to say, the trailer that I cut was very much an eighteen certificate. Some young model, who I now have to write into the film, practically naked but for a wet bra, but it’s fine because we would have had one in there somewhere. I spliced in shots from the first film, the one with a decent budget and a film release, the one we didn’t get to make. This is what I do; you’ve got to hook your audience. And we stick it all over our adult comedy videos, our soft porn videos. It raises awareness, so when we finally come to sell the thing, we can say we already have a market. But my audience is not three- to five-year-old kids, or their mums, who stick their pride and joy in front of our bestselling kids’ video franchise, Bristo the Badger, for an hour’s peace in the mornings. As usual it has nothing to do with me. Some bright spark in the mastering department, some doped up operations type, has got confused. It’s a publicity nightmare. Not that anybody is going to care so much about that. What José is obviously doing his nut about right now is the fact that it’s going to cost us tens of thousands of pounds to recall all the tapes, and replace the trailer with something a little more three-to-five-year-old friendly. Saying that, I doubt it’s the kids themselves that have complained. More likely some young mum with a rich husband, who gets to sit about all day thinking about playing tennis, has happened to catch a glimpse of our original Evil Ghost, after hearing her offspring having a good old giggle at the naked lady on the television. Again, this is not my fault. Why doesn’t she just take her kid to the park, instead of sticking it in front of a box all morning? I have a feeling they won’t let me send a letter back saying that. And even though José knows it has nothing to do with me, you can bet he is damn well telling anybody who will listen back at the office that it is, because I am the person who doesn’t happen to be there. I am the one out, on his orders, photographing an old bird in smog.

‘Phil, I’m coming back. Don’t worry about it, it’s nothing to do with us.’

‘One last thing.’

‘What?’ Surely nothing else can be wrong.

‘Charlie called.’ I catch the tone of his voice, but ignore it. I am more surprised than anything. Charlie doesn’t call my work any more.

‘Really? Charlie? What did he want?’

‘I don’t know, but he sounded weird. I answered the phone, and he asked me if I was you. Obviously I said no, and he hung up.’

‘That’s not weird, Phil, that’s just him,’ I say. Obviously he doesn’t even recognize my voice any more.

‘Yeah, but he sounded really strange, like he was upset or something.’

‘It’s probably just the coke,’ I say, and hang up. I don’t even know if he still does it. I know he was doing a lot, a couple of months ago. I’ve stopped asking now.

I go over to Charlie’s apartment early, just to get away from José, who is making vaguely disguised accusations in my direction about ‘Badgergate’, as it has already become known by the time I get back to the office. Charlie lives in East London. We live on opposite sides of town – Charlie in his urban wasteland outer and minimalism inner on one side, and me amongst the trees and families and pubs with gardens, on the other.

If I lived with him, I’d have to see him shagging other women, and that might force me to confront things. I wouldn’t be able to ignore an orgasm in our bed.

I wonder at what point love became so trivial. I wonder when I began to deride my heart, instead of feeding it, when I decided it didn’t matter and wrote it off. I wonder when the loneliness and despair became almost laughable. I wonder when we learnt to dismiss the pathetic who went back again and again to have their hearts trampled on. I wonder when they became ‘pathetic’.

When romance does break through all the walls these days, it leaves me in tears. If people sing in tune, or run the marathon, or exemplify any kind of harmony or commitment it leaves me crying, in private of course. Because these are the things my life lacks, and I cry that I wasn’t more careful to hold onto them.

I wonder why starvation, or racism, are so much more weighty issues, so much less pathetic than the emotional heartburn caused by the one you love trampling all over your feelings, and your heart. Why is this not deemed just as bad as an earthquake? Sure it affects just you, and not ten thousand people, but you can bet your life there is more than one person in the world at any given moment feeling like their world has ended, because they have been unbearably hurt by the one they love. There must be at least ten thousand at any one time. An earthquake for every day of the year. We are told to spend our whole lives looking for real love, and then if we find it and lose it again, we are supposed to underplay it, pull ourselves together, and get on with life.

When did love become a joke?

When did I?

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/louise-kean/boyfriend-in-a-dress/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Louise Kean

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Эротические романы

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A novel about cross-dressing, social apathy, and seeing the best in people, a little too late.It started when I came home and found my bloody pointless stupid bastard boyfriend, Charlie, on my sofa, in my blue Lycra dress. He was having some sort of breakdown.It transpired that Charlie had been having an epiphany of sorts. The previous night, standing on his balcony, he had witnessed an attack – on a woman he′d just kicked out of his bed. Ahsen and shaken, on his way to work the next day, he had found a dead body in the train toilets and now here he was, in a dress, sobbing uncontrollably.I had been ready to dump Charlie once and for all – he was an unfaithful bastard (so was I, but not to the same extent). But he convinced me to run off with him to Devon for a week to sort his head out and I decided I owed him that much. Sizzling in the unlikely heatwave that week, everything changed between us, as we sucked on ice-creams naked on deckchairs, and hi-jacked an old people′s bowling green. But despite the fact that our relationship had never been so strong and never meant so much to either of us, could we handle what was waiting for us back in London?