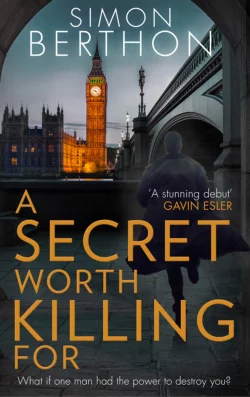

A Secret Worth Killing For

Simon Berthon

‘A stunning debut novel…It could not be more timely.’ – Gavin EslerSomebody knows where the bodies are buried…Newly-appointed Minister of State Anne-Marie Gallagher appears to have an unblemished record. Only she knows the truth. In the early 1990s, she was embroiled in the IRA’s violent past, and integral to a mission which went disastrously wrong.So far, skeletons have remained in their closets. But, unknown to Anne-Marie, DCI Jon Carne has just received an anonymous tip-off. The co-ordinates lead Carne to a body – badly decomposed after twenty-five years underground.When news of the discovery reaches Westminster, Anne-Marie knows that she is at risk of being exposed. And with Carne closing in, there’s not much time for the new minister to decide how far she’ll go to keep her past where it belongs…Power comes at a price in this sharp, smart political thriller – perfect for fans of Charles Cumming and Mick Herron.‘A stunning debut novel from a top TV producer, A Secret Worth Killing For takes us from the back streets of Belfast during the Troubles to power and parliament in London. It could not be more timely.’ – Gavin EslerPreviously published as Woman of State

A Secret Worth Killing For

Simon Berthon

Copyright (#ulink_85886ce5-68e6-5b2c-bb04-14a3cd5e0bf5)

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2017

Copyright © Simon Berthon 2017

Simon Berthon asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © July 2017 ISBN: 9780008214388

Version: 2018-02-06

As a journalist, historian and documentary maker, SIMON BERTHON has long been fascinated by the secrecies, deceits and ambitions of the state. His previous books are Allies at War and Warlords (with Joanna Potts). A Secret Worth Killing For is his first novel.

For Penelope,

and for Helena and Olivia

Contents

Cover (#ub633ffe6-f8f8-5e1c-a6c6-56a8f06e3fa4)

Title (#u9586d245-a455-51cd-a54f-f301e666a8d0)

Copyright (#ulink_1a257612-2705-5afb-9d44-a853bd9f77c6)

About the Author (#u353afa41-77a8-56ae-956f-dbf574964756)

Dedication (#ue9d88975-a19b-5439-b376-adde65b25953)

CHAPTER 1 (#ulink_074ac322-9792-5426-adb7-de6c69ada544)

CHAPTER 2 (#ulink_90f678c4-84d8-5029-bc46-e793cc9dab10)

CHAPTER 3 (#ulink_c90041f6-648a-591c-930f-213bdc3146c4)

CHAPTER 4 (#ulink_89d2d596-d89c-588c-ae16-cf3a2a18cdf1)

CHAPTER 5 (#ulink_a984c5f1-b4bf-55f1-bf8f-5657dd24bc56)

CHAPTER 6 (#ulink_f3085439-751b-5140-a5b5-ac7f6c9ccca3)

CHAPTER 7 (#ulink_01d2da84-fa7f-52a7-bf51-3ee3bdbda10b)

CHAPTER 8 (#ulink_9058ad59-78e5-531c-a02f-e861c4490fa5)

CHAPTER 9 (#ulink_eb696f72-0a36-5d57-95f3-7b0c075b13d3)

CHAPTER 10 (#ulink_2e85d1e2-29a9-5dd0-aade-4efa4cdce09b)

CHAPTER 11 (#ulink_353acb3d-f688-56b2-8041-bb4085cb116c)

CHAPTER 12 (#ulink_919fdd8f-fa6d-5284-b9c4-ad5def1f814b)

CHAPTER 13 (#ulink_f82e3af8-14d7-5930-8a32-ee896e8a4445)

CHAPTER 14 (#ulink_e7f4ca4f-adc8-5f7e-975d-362812f880ac)

CHAPTER 15 (#ulink_2257c53a-299b-53df-ae15-82c2e684cb5a)

CHAPTER 16 (#ulink_4600f665-877f-5af7-b6f4-dcf48ab1cd7d)

CHAPTER 17 (#ulink_48c9f96f-778f-5d56-849a-3e8d28526736)

CHAPTER 18 (#ulink_50ab5cba-75ba-5af5-a3b1-5b1c660fe1bb)

CHAPTER 19 (#ulink_df2252ec-66ff-5f35-b092-87c8b444dd78)

CHAPTER 20 (#ulink_e1cd7645-5e10-5ca8-a6e6-66d13a9e86c5)

CHAPTER 21 (#ulink_83f07150-bef7-56aa-9c77-35abdb6a7095)

CHAPTER 22 (#ulink_e25784bf-f8e6-5178-a1be-3a229282cfa7)

CHAPTER 23 (#ulink_dbc1e45b-adf6-5fea-8b55-3b995bde6d51)

CHAPTER 24 (#ulink_7a2e8f34-b457-5f96-96a5-1b863edec7fa)

CHAPTER 25 (#ulink_c66c2ff9-d75d-5f06-a9ca-9bb72d7dfb6a)

CHAPTER 26 (#ulink_2ea619c1-ac9a-5efa-b4e0-4e99f39761c8)

CHAPTER 27 (#ulink_05484f94-5f72-5e64-a47e-0ca1484a01f7)

CHAPTER 28 (#ulink_b2bb7da0-0fe7-5df9-b10f-ed64d9cb1bcb)

CHAPTER 29 (#ulink_bb6c79a4-f681-5e7b-bf9e-e11ef46b47ce)

CHAPTER 30 (#ulink_22fff708-8a93-547b-8d03-485d3739278b)

CHAPTER 31 (#ulink_d0c51b84-2305-59a9-8d29-d457aa68fd01)

CHAPTER 32 (#ulink_53aada0c-da18-5945-bc4c-2955a2c3ea1e)

CHAPTER 33 (#ulink_b128c968-01a3-53e8-9e52-bfb2ce3a9001)

CHAPTER 34 (#ulink_d21cb722-da3d-51a5-9b4e-68bfb1245673)

CHAPTER 35 (#ulink_fcd3b863-cd13-58b8-82d7-e5210785af37)

CHAPTER 36 (#ulink_de33853a-0395-5e55-bc2f-1fefa77d942a)

CHAPTER 37 (#ulink_ef78ea92-862c-5bbc-9e5c-b7b75a8e00a1)

Acknowledgements (#ulink_70ba00c0-6bbf-59fb-8391-7bf06ef1850e)

CHAPTER 1 (#ulink_638be387-5bdf-55f5-b933-f96f795e0e5b)

July 1991

‘The movement needs your help.’ She’s lying next to him in Falls Park, the summer of 1991. A-levels are over, the sun shines, university beckons. A scholarship at Trinity College, Dublin, is in the offing and, in the case of clever Maire Anne McCartney, the teachers are confident.

‘Whaddya mean, Joseph?’ she asks, propping herself on an elbow and looking down into his eyes.

‘You’re committed, aren’t you,’ he says. It’s a statement – a confirmation – not a question.

‘Course,’ she replies. ‘Politically, anyway. Freedom, equality.’

‘Politics won’t get us there. It’s the struggle that matters.’

‘I’d never stand in your way, Joseph, you know that. It’s just not the way for me.’ She leans down and gives him a peck on the forehead.

The brightness of the day illuminates him, the chiselled chin, full lips, straight nose, the sparkle in his azure eyes. She expects him to put his arms round her, pull her on to him and roll in the grass till they laugh themselves to a halt. Last night they made love three times; she can still feel him inside her.

He turns away, avoiding her. She detects a tightening in his eyes, a clenching of the cheeks she’s never quite seen before.

‘You know I love you, don’t you, Maire?’

‘Course I do. And I love you too, Joseph. Don’t I always say it?’

‘You do. But just this once I need you too,’ he says, turning back to her. ‘I mean the movement needs you.’

A quiver of alarm. ‘I dunno what you mean.’ He shifts away again. ‘You better tell me,’ she urges.

His eyes swivel and engage hers with a ferocious intensity. ‘There’s a Brit peeler over here – name of Halliburton – Special Branch. On some kind of loan. We’ve been tracking him. He gets lonely at night, drinks in the Europa, eyes up the bar girls. But doesn’t follow through. Around eleven, he’s in his car, heading back to Castlereagh. They’re either housing him in the station or somewhere near; we’re not sure. We wanna speak with him.’

‘Speak with him, Joseph? Whaddya mean, speak with him?’

‘Interrogate him. Find out what he’s doing. Get some intelligence.’

‘And then what? When you’ve interrogated him.’

‘Just scare him. Let him know we’re onto him. Suggest it’s time he leaves.’

‘What’d be the point of that?’

‘Propaganda. How we ran a Brit SB man out of our island. It’ll read well.’

‘And that’s all?’

‘Aye, that’s all.’

She rolls over and sits up straight – he raises himself alongside her.

‘Does Martin know ’bout this?’ she asks. ‘Course he knows.’

‘And ’bout you speaking to me.’

‘He would, wouldn’t he? But it couldn’t come from him, could it? Not brother to sister. Wouldn’t be right.’

‘But he knows.’

‘Well, he would.’

She stands up, the warmth of the sun heating her back through her light-red jumper. It’s not enough in itself to create the sweat that’s prickling her. He springs up and ranges alongside.

‘We just need you to attract him. Your quick wits, quick tongue, it’ll be easy. Just a chat-up in the bar, you’re a student wanting a free drink. You take him to a flat. We got one ready in the university area.’

He outlines the plan. All she’s doing is picking up a bloke over a drink. Happens every night, hundreds of times over. She’s listening hard – he cranks it up. ‘Look, Maire, there are moments when you can’t just stand by and look on. Be a passive observer. At some point, everyone has to do their bit. Look at the leadership now, the politicians. Do you think all they ever did was talk?’

‘I’ve just finished A-levels, Joseph.’ Her first instinct is to repel him but right now, at this moment, she doesn’t want to show weakness that could invite his disapproval.

‘Aye, you’ve done well. But you’re eighteen now, grown up. An adult. You’ve responsibilities.’

‘What about responsibilities to myself?’

‘That’s just selfishness. It’s not just the struggle, it’s your friends, your family, your community.’

She halts abruptly. Divis mountain ahead, so often a dour, brooding darkness, seems almost radiant, a mass of green light.

‘I’ve never got involved in that way.’

‘Aye, but this isn’t like that.’

‘You promise me it’s just to interrogate him?’

‘Aye.’

‘No violence. No beating. Just propaganda. Just to show you can do it.’

‘Aye.’

‘I need to hear you promise me, Joseph.’

‘That’s fine. I promise.’

‘You give me your word.’

‘Aye.’

‘And Martin approves?’

‘Aye, he would, that’s for sure. No doubt ’bout that.’

She thinks in silence. She remembers the hunger strikers dying when she’s still a girl and the hatred for the British oppressor. Three years later, she shares her big brother’s pleasure when the IRA blows up Mrs Thatcher’s hotel in Brighton. She knows the cause is just but, for her, school, good results, getting to university become the priority. The British state is still hateful, but her belief in the ‘armed struggle’ deflates like a slow puncture.

Yet Joseph has touched a nerve, a lightning rod brushed by lingering guilt. Maybe he’s right and she’s been selfish. She copped out when others didn’t. If what they’re planning is for propaganda, not violence, perhaps it’s just another act of cowardice to keep on avoiding it.

She flicks a glance at him. What if he’s lying? Just talking shite? When did they last let a peeler walk free? She looks away. He’s never lied to her before. Not that she knows, anyway.

Momentarily, a cloud obscures the sun, turning the mountainside an unyielding brown. He’s saying nothing, the quiet oppresses her. Time seems to freeze – the flapping of a bird’s wing high above reduced to the slowest of motions.

His expression has retreated to that beautiful poet’s dolefulness when she’s about to disappoint him. Like those early months after the first full kiss when she wouldn’t go the whole way. Until she did. If she says no to this plea – a plea he’s made with such passion – will he ever forgive her? Might she even lose him? She thinks of asking – but doesn’t want to hear his answer.

She turns. It’s visceral – she just can’t displease him. ‘OK, I’ll do it. Just this once. For you.’ It’s as if the words have tumbled out of her mouth before she even made a decision. A sudden consolation – maybe she’ll still be able to get out of it. She chides herself for even thinking it. Her rational self re-engages. ‘And there’ll be no violence?’

‘Yes, there’ll be no violence.’

She’s told her mother she’ll be in for tea that evening. Rosa has cooked cottage pie and peas, one of Maire’s favourite dishes. She plays with her food, even forgetting to splash it with ketchup, and speaks little.

‘What’s up with you, Maire?’ asks Rosa.

‘Aye, girl, you need to eat,’ chips in her father. Rosa casts him a warning glare to keep out of it.

‘Sorry, Mum,’ she says. ‘Just not feeling hungry. Dunno why.’

Rosa, who’s come to realize that Maire must be sleeping regularly with Joseph, betrays a sudden alarm. ‘Not feeling sick, are you, love?’

Maire looks up with a wan smile. ‘It’s OK, Mum, I’m not feeling sick.’

‘Well that’s all right, then, love.’ At any other time, Maire would hug her mother out of sheer love for her maternal priorities. On this evening she feels only emptiness in the pit of her stomach.

As they’re clearing plates, the front door clangs opens and Martin breezes in, bestowing smiles and kisses all round. Maire suddenly wonders what her parents think of him; whether they even know his prominence in the movement. Politics in general are sometimes discussed at home, but the rights and wrongs of violence are no-go. It’s only, and infrequently, mentioned when she’s alone with her brother. They must suspect – they’d be blind not to – but have decided it’s best to keep out.

‘Hey, little sister, you’re looking gorgeous as ever,’ Martin declares, not a care in the world.

Maire attempts a show of response but recoils. Surely he must know about Joseph’s conversation with her today and her acquiescence. She wonders at his bravado, and the masking of his double life as happy-go-lucky son and IRA commander.

He notices her listlessness. ‘What’s up, kid?’ How can he even contemplate such a question? She searches for a hint.

‘It’s nothing,’ she says, ‘just a chat I was having with Joseph.’

‘So how’s the world’s greatest revolutionary doing?’ There’s an edge of condescension in her brother’s tone. Again she flinches at his duplicitousness.

‘Full of schemes, as always,’ she replies.

‘Aye, that he is,’ says Martin. ‘That he certainly is.’

He’s giving her nothing. Literally nothing. No comfort, no support, not a hint of empathy. Perhaps that’s the way it has to be.

They decide to try it the next Saturday night. More people milling, more cover, guards more likely to be down.

She prepares. She’s cut her hair, taking three inches off the long auburn tresses, and used straighteners to remove the waves and curls. Instead of the hint of side parting, she brushes the hairs straight back, revealing the fullness of her face and half-moon of her forehead. She examines the slight kink in her small, roman-shaped nose. As always, she dislikes it. She applies mauve mascara and brighter, thicker lipstick to her cupid lips. She wears a black leather skirt, above the knee but not blatantly short, and a bright-pink, buttoned blouse that doesn’t quite meet it in the middle. The gap exposes a minuscule fold of belly. She pinches the flesh angrily. Through the blouse, a skimpy black lace-patterned bra, exposing the top of her firm small breasts, is visible. The overall effect is not a disguise, just a redesign. While it doesn’t make her look cheap or a tart, she’s unmistakably a girl out for a good time.

She’s steeled herself, told herself it’s just a job. Clock on, clock off three hours later. Thoughts of how to pull out have besieged her every minute since she said yes – even though she instantly knew she couldn’t. But once she’s done it, that’ll be it. Never again.

She’s kidding herself. Once you’re in, they’ve a hold over you – you’re complicit. She thinks of her brother – did he recruit Joseph? How did they get their hold over him? She remembers that tightness in his face. Did they ever need to?

She arrives just after 8.30 p.m.

As agreed, she finds a bar table with two chairs, sits down and appears to be waiting for her date to arrive. A waiter comes – she orders a vodka and Coke.

He’s already there, sitting at the bar. The description, both of him and his clothing, is accurate. Late thirties, sandy hair retreating at the sides, a ten pence sized bald spot on top covered by straggles of hair that offer an easy mark of recognition from the rear. On the way in, she’s been able to catch more; the beginnings of a potbelly edging over fawn-belted, light-brown trousers. Brown loafers and light coloured socks, dark-brown leather jacket. Perhaps the brown is an off-duty discard of the policeman’s blue. On his upper lip, a pale, neatly trimmed moustache. Brown-rimmed, narrow spectacles sitting on the bridge of a hook nose. Somewhat incongruously, pale blue eyes. From those first glimpses, he seems a nicer-looking man than she expected. A relief, given one part of the task that lies ahead. But ugliness becomes a victim more easily.

They say he usually drinks one or two before chatting up the bar girls and waitresses. Around 9.15, when she’s been waiting three-quarters of an hour for her elusive date to arrive, she walks towards the bar. She places herself beside him.

‘Another vodka and Coke,’ she demands, louder than necessary.

He turns to her with a raise of the eyebrows.

‘Bastard hasn’t shown,’ she says, glaring at him as if to say, ‘Whaddya want?’

‘He’s a fool.’ He eyes her with frank admiration. The accent is English, south not north. A confirmation.

‘I’m the eejit,’ she says. Her drink arrives and she makes to return to her seat.

‘You might as well stay and chat till he comes. I’ll pull that stool over.’

She hesitates. It seems too easy. What’s this man really like? From nowhere she imagines him hitting her. Where did that come from? Nerves, just nerves. Her heartbeat is racing. She gathers herself. ‘I left my coat at the table.’

‘It’s OK, I’ll keep an eye on it.’ He chuckles. ‘I’m good at that.’ His remark startles her. She hopes she’s not shown it. ‘So who’s the missing boyfriend?’ he continues.

‘Ex-boyfriend. Bastard,’ she repeats. Is she overdoing it? She senses how miscast she is for this performance. She’s a quiet student who should be buried in her books. Some even say she’s gawky. Suddenly she sees that’s maybe why Joseph’s picked her. The copper will never suspect.

He shrugs and sips from his glass. Scotch and ice, must have been at least a double. ‘Men,’ he says. ‘Can’t trust them. Just like criminals and politicians. No wonder they’re usually men, too.’

‘Thatcher?’ she says.

‘Thought you girls said she was a man, too. Anyway, they got rid of her. Assassins all men.’

She makes herself laugh. He raises his glass; she raises hers and clinks.

‘Cheers,’ they chime together, grinning at each other.

‘Bet they were glad round here when she was dumped,’ he says.

‘Aye, they banged the dustbin lids.’

He pauses for another sip. ‘Sorry, should have introduced myself. Name’s Peter.’ The final confirmation.

‘Annie.’ Unless he’s lying, like her.

‘So whose side are you on, Annie?’

‘My side. Fuck ’em all.’ He frowns. ‘Sorry, I should mind my tongue.’ She sticks it out at him like a rude child. What came over her to do that? The job’s become an act, two more hours on stage before the curtain falls.

His grin widens. ‘I like your tongue. Agree with it, too.’

He’s flirting hard now. Another pause. She doesn’t want to seem like she’s making the running. Eventually, he resumes. ‘OK, I’ll try another tack. What do you do, Annie?’

‘Studying. Queen’s. Just finished first year. I’d like to travel but I don’t have money.’

‘Can’t you get a job?’

‘A job here! In Belfast! You find me one.’ A further silence. This time she feels safe to have her turn. ‘And youse?’

The hesitation is just perceptible. ‘My company’s sent me over for four months. We’re investigating setting up an office. The grants are good.’

‘Whaddya do?’

He’s thinking. ‘Financial advice. Investment. All that stuff.’

‘So you’re rich!’

‘That’ll be the day.’ He peers down at his glass.

She feels sweat on her neck and between her breasts. She moves her right hand to her left wrist to check her pulse.

He notices. ‘Are you OK?’

‘Yeah, just the heat.’ She smiles. She can’t take the tension much longer, not knowing if he’ll bite. Maybe he’s sussed something – but he hasn’t come with his own prepared story, she’s sure of that. She needs her moment of truth right now. She looks at her watch, finishes her drink and finds the line to close Act One. ‘Bastard still hasn’t shown,’ she says angrily. ‘Suppose I’d better be heading.’

His head jerks up and round. ‘Don’t do that, I’ll buy you another.’

He’s bitten. She inspects him, to make him feel he’s undergoing an examination, to ratchet up his gratitude if she accepts. ‘I probably shouldn’t,’ she says. ‘I dunno you, do I?’

‘I’m harmless as a butterfly.’ His eyes plead with her. He’s on the hook.

‘OK, then, might as well get pissed. Nothing else to do, is there?’

‘You’re the local,’ he says. ‘I was hoping you might have something in mind.’ It’s his first openly suggestive remark and it’s taken time. He’s a cautious man, but now he orders a double vodka and Coke for her, and a double Scotch for himself.

They drink and chitchat, nothing personal or controversial, but a mutual hunger in the eyes. Occasionally she flashes a look around the room. ‘Just in case the bastard’s skulking,’ she tells him. In a corner of the bar she spies a man she’s seen with Joseph once or twice. He’s always peeled off as soon as she arrives, back into his undergrowth. But not tonight. The exit door is jammed shut.

Just before 10.30, an alarm sounds, abrupt and deafening. A voice booms over the Tannoy. ‘Ladies and gentlemen, we have a bomb scare. Please evacuate the building now.’ The warning words are repeated every five seconds. They’re on cue.

‘I’ll grab my coat,’ she says.

‘I’ll wait for you,’ he replies.

They walk out into Great Victoria Street to join the hundreds retreating behind the barricades. Bomb warnings are no longer scary – the age of nightly explosions and shootings has long gone. Now it’s a meaner war. Individual murder, assassinations, suspected informers tortured and ending up with a bullet through the knees or head. A few weeks ago three IRA men were ambushed on a country lane and shot dead by the SAS. That had to come from a grass. She remembers it – no wonder Joseph, her brother and friends want an intelligence propaganda victory. Maybe what she’s doing is OK.

She sets off south and he sticks to her limpet-like. Once they reach the other side of the yellow tapes, they stop to catch their breath. Sirens and shouts echo, nothing more.

‘Bastards,’ he says, ‘why did they have to break that up? I was enjoying myself.’

‘Me too,’ she agrees. ‘Fucking eejits.’ She pauses. ‘Well, I suppose this is it, my flat’s not far. Better be away.’ She’s nearing the end of the second Act – moment of truth number two. She looks at him. ‘And you should be, too,’ she says cheekily.

‘We shouldn’t let them get away with it,’ he says. ‘Busting up the evening like that.’ He takes a breath and exhales into the night air. ‘Can I get you another drink?’

‘Reckon I’ve had plenty,’ she says.

‘Coffee, then?’ he pleads.

‘Honest, I should be heading.’

‘OK, coffee in your flat. And then I go home.’

She laughs at him. ‘You don’t give up, do you?’

‘You make it hard to,’ he says.

‘OK, coffee in the flat.’ Hook, line and sinker. She pounces, giving him a quick kiss on the lips. She feels him relax with pleasure and anticipation as they head towards Botanic and he puts his arm round her. Act Three is about to begin.

They’ve taken a short lease on a first-floor student flat in a street of Victorian terraces. She’s been driven past it once – she wanted a second look but they said it was too risky. There’s a Yale lock above and a mortice below – they’ve told her the mortice will be left unlocked to make it easier for her. They should be in position by now. While she and the man walk, she tries not to search for their car and them waiting inside. The street lamp is opposite the front door, illuminating the house number. She unlocks the Yale and pushes the door open.

‘Don’t you double-lock?’ he says. He’s drunk plenty but he’s still a policeman.

‘No petty crime in this town,’ she replies without a beat. She thanks heaven her brain’s quick enough to disarm him.

She switches on the stair light and leads him up. With the university on holiday, both the ground- and upper-floor flats are empty. At the top of the landing, she slots a second key into a bare wooden door and ushers him in. She’s learnt the floor plan, memorizing rooms, doors, furniture, cupboard contents, electrical appliances. They’d better have got it right. She’d better have remembered it right.

‘Sorry, it’s a bit dire,’ she says. ‘My flatmates are away for the vac but I didn’t wanna be trapped at home with my ma and da.’ She pauses, feigning embarrassment. ‘It means I’m sort of camping in the bedroom.’ She nods towards the room at the back. ‘TV’s there if you want. I’ll make coffee. Oh, bathroom’s there.’

‘Thanks,’ he says. ‘I could do with it.’

She puts on the kettle. When it begins whistling, she creeps to the front door and peers out. They’re there. She puts the palms of both hands to the window, fingers and thumbs splayed out. Ten minutes. Ten minutes till the play ends and the job’s done. She wants it over.

She’s back in the kitchen just as he pulls the plug. She hears sounds of hand washing and face scrubbing. He’s preparing, cleaning himself for her. More washing sounds. She imagines him taking out his penis and soaping it in the basin. The nerves have been there all night. Now there’s a charge of fear.

He leaves the bathroom, turns into the narrow passage and stops by her in the kitchen. She’s pouring coffee into cups. He comes behind her and puts his arms round her, moving down to the roll of her waist and round to her buttocks. She leans back against him.

‘Look what I found,’ she says. She picks up the dusty, half-drunk bottle of Teacher’s that’s been placed beside the coffee and tea jars.

‘Scotch, not Irish,’ he leers, ‘must be my lucky night. She puts her left hand behind her, pats his buttock, then moves it around past his crotch. He’s erect. She can feel the evening’s drinks rising in her throat.

‘You carry the Scotch and glasses,’ she orders.

They retreat to the bedroom and she waits to see where he puts himself. He takes off his shoes; she follows suit. There’s a double bed and double duvet, but cushions on one side only.

‘Here looks comfortable,’ he says, stretching out on the bed. ‘And I can see the telly.’

‘Is that what you’ve come for?’ she asks, flashing her most alluring smile.

‘And the coffee.’ She pours two cups and brings him one. Then she pours Scotch into a tumbler and places it beside him. He puts his arms around her to draw her towards him.

‘Not yet.’ This is the moment she knows might come but can never fully prepare for. Joseph has suggested what to do if it gets this far – he says he knows what a man really likes. And it will incapacitate him, protecting her and making it easier for the boys after she’s left. She doesn’t even want to think about that.

Again she tells herself it’s just a play – and she’s just this evening’s performer. She forces herself. ‘Close your eyes,’ she whispers in his ear. She walks round to the front of the bed and strokes him from the toes up. Through ankles, calves, knees, hamstrings, fingers moving up to the front of the waist. There they stop, unbuckle the belt, and slowly slide down the zip fastener. His eyes remain closed, though he’s breathing faster and emitting soft murmurs. She pulls his trousers from beneath him and slips his pants down. The pants’ elastic waist reaches down to his tip – as it passes over, he bursts out and upright, swollen to a size she hasn’t seen on Joseph.

‘My word,’ she gasps. He opens his eyes, looks beyond his chest and stomach at her mouth level with the engorged tip. She gives it a short touch. He murmurs again. She feels burning in her throat. She mustn’t retch.

‘I just need to go the bathroom,’ she says, ‘make myself ready.’

‘I can’t wait,’ he whispers.

‘Course you can wait. Willpower. I wanna make it fun.’

‘Oh, sweet Jesus,’ he sighs.

She closes the bedroom door behind her, goes to the bathroom and runs a tap. She re-emerges and creeps towards the front window. With her left hand she forms a zero with her thumb and forefinger and holds it against the glass. With her right hand she waves inwards. She re-enters the bathroom, stops the tap and pulls the flush. Both the flush itself and the refill are inefficiently noisy, an unexpected bonus.

Against their background sounds, she edges on her toes to the flat’s entrance, praying no floorboard creaks, and descends the stairs to the front door. As she opens it, they allow her to leave before they enter. Four of them, masked. She has a pang of sadness for the man she’s left behind and the ordeal he faces, then walks, increasing her pace with each step. The pavement is dry and smooth. It’s just as well as she’s been unable to retrieve her shoes. Joseph and his friends will tidy up. At least she’s wearing stockings.

She hurries past Botanic station, and over the roundabout into Great Victoria Street. Ahead the barricades are still up and no one is being allowed near the Europa. She stops; the fire in her throat rises. She runs to some railings, leans over, and retches. A tiny stream of bile, nothing more. It’s not nerves – or guilt – that’s brought it up, just the memory of touching him.

She straightens, skirts the crowd, turning right, then left towards the city centre. It’s still only 11.30 p.m., a single, eternal hour since they left the bar. Now she can lose herself in the late-night revellers and make her way to the black taxis heading for Andersonstown. A girl who’s had too good a night out and somehow managed to lose her shoes in the process.

Her heartbeat quietens. They may have made her complicit but, should they ever try again, she knows she won’t do it, whatever the consequences. It may be their life, it’s not going to be hers.

The curtain falls.

It’s over.

CHAPTER 2 (#ulink_1dfbd69f-c6e5-5017-8eb6-96ca0a475a83)

The next day, Sunday, she stays at home in her room.

‘Coming to Mass, Maire?’ her mother yells up.

She peers down from the landing and addresses the bottom of the stairs. ‘Sorry, Ma, still a bit off colour. You and Da go on.’ She wonders why they persist.

She spends the day in her room with the local radio on. All is quiet and she feels an overwhelming relief. By evening she decides she’s calm enough to appear for tea. She comes downstairs, where her father’s watching the six o’clock television news in the living room.

‘Jeez, Maire, have a look at this.’

The screen shows the taped-off street, and the flashing lamps of police cars and an ambulance beyond. Nausea rises, this time from her midriff. She’s missed the newsreader’s introduction and a local reporter is taking up the story. ‘It seems the male victim was lured to this flat off Botanic Avenue and then set upon by attackers waiting inside. It appears that some sort of fight may have broken out, during which the man was shot dead. It’s not known at this point who the victim was or whether the attack was a purely criminal one or had a political or paramilitary connection.’

‘What the hell was going on there?’ Stephen exclaims. The news gives way to the Sunday sporting action and he buries himself in the newspaper. Another day, another shooting.

She wants to retreat to her room but forces herself to stay with her da until the end of the weather forecast. She looks into the kitchen. The smells of cooking repel her.

‘Sorry, Ma, still off the food. Must be a bug or something I ate.’

Rosa watches as she goes back up the stairs. Something unusual is going on with her daughter but she knows better than to press. It will all come out in due course, or just go away.

Maire wants to go out, to run for miles, to lose herself in exhaustion. Anything to stop thoughts. But the summer nights are short and she’s afraid of the daylight. By 10 p.m. she can stand it no longer and leaves the house without a goodbye or see you later. ‘Must be something to do with Joseph,’ Rosa mutters to Stephen.

She paces the streets for an hour, taking deep breaths, willing herself to restore the calm she’s now lost. Did they, or rather Joseph, deceive her and always intend to kill? Perhaps the policeman was carrying a gun – though, if he was, he kept it well hidden – and managed to grab it as they entered. But she heard no shots as she walked away. It surely means they must have taken control of him.

Joseph gave her his word. He used the word ‘promise’. Was it a lie? Or was he lied to? She has a horrible vision of her brother as the mastermind. Surely that can’t be. More than betrayal, what she now feels is a sickening combination of terror and her own foolishness – the knowledge that she allowed herself to be deceived. She clings on to the hope that something went wrong in the flat – that he brought his death upon himself. That, in some sense, he deserved it. She wonders who will miss him and tries to banish the thought.

Without planning it, she finds herself near Joseph’s street – he still lives with his family and they’ve used a friend’s place to sleep together. Unable to stop herself, she approaches the house. At the last minute she delays, watching for movement through any gaps in the curtains. She sees none, but some ground-floor lights are still on and she rings the bell.

Joseph’s mother answers. ‘Maire, you’re looking in late.’

‘Sorry, Mrs Kennedy.’

‘It’s OK, love, come in.’

‘I was just looking for Joseph.’

‘Haven’t seen him today, love. You know how it is with him. Always in and out.’

‘OK, Mrs Kennedy, never mind. Thanks anyway. I’d better be away.’

The next day is worse. Silence. Alone. She’s been hung out to dry. She tells herself again that this is what it must be like. Despite the falseness she feels ever surer of, she craves to see Joseph. Perhaps he really does have an explanation and it can still be all right between them. She listens out for Martin’s footsteps and one of his cheery entrances into the house. It doesn’t matter what’s said, she simply needs someone who knows to talk to.

At lunchtime, the noose tightens. ‘The victim was Inspector Peter Halliburton, who was on secondment to local police from London’s Metropolitan Police Special Branch. Mr Halliburton, aged thirty-six, was married and had two children of six and eight. There has still been no claim of responsibility for his killing,’ announces the radio news.

She thinks of him lying on the bed, his zip undone, his penis bared, a young man, husband, father, in the dying moments of his short life. She tries to justify it. He shouldn’t have come with her. He betrayed his marriage and those children. He was a representative of the occupying forces. The words and excuses taste of sulphur.

Her one good fortune is that on Monday both her parents are out and she can stay in her room without need for explanations. In the late afternoon, shortly before her mother is due home, she goes out, propelled once again by some automatic, subconscious navigation in the direction of Joseph’s home. She steels herself to ring the bell. No answer. She knocks on the door. No answer. She backs away to look up at the first floor. The curtains in Joseph’s room are drawn. Either he’s still away or deliberately avoiding her. The question jumps at her. Could they have arrested him? Are they holding him, forcing him to implicate her? Surely his mother would have known. Surely Joseph is too smart.

Early the next morning, 5.45, it happens. A violent beating on the front door, the sound of her father descending the stairs to answer it. She peeps behind a curtain of her bedroom window to see two armed police jeeps to the right and left and a police saloon, its roof light silently revolving. She hardly has time to take it in before two uniformed police enter her room with neither words nor knocking.

‘Get dressed,’ says one.

The second speaks more formally.

‘Maire McCartney?’

‘Yes.’ She tells herself to resist the tears.

‘I have a warrant to arrest you on a charge of conspiracy to murder Peter Halliburton on the night of Saturday the twenty-third of July. You have the right to stay silent. Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law . . .’

Even as she dresses herself, and they pull her hands in front of her to apply handcuffs, it’s as if it were happening to another person. It belongs to a parallel universe. The person she really is could never have degraded herself to this.

The walk down the stairs and out of the front door freezes her into self-loathing. Her mother and father watch, their eyes aflame with humiliation. She’s unable to speak, only to shake her head. Once inside the police car, she lacerates herself for being too weak to leave them words of hope.

They take her to Castlereagh, a journey that is a badge of honour for anger-fuelled young men, a spiral into blackness for her. How do they know it was she? They must have soon worked out that the victim had been lured. Were her shoes still in the room, showing that a woman took him there? Could Joseph and friends have been so careless? Did they suspect Joseph and make the connection to her? Perhaps they’re just operating on that hunch and have no hard evidence.

She slumps in a cell for hours, allowed only to brush her teeth and visit the toilet. She’s escorted to a bleak room where a woman in a white coat takes her fingerprints and a swab from her throat. She’s brought food but her sense of time begins to fade. All she knows is that, when she’s taken to an interview room, occasional shafts of light show that it is not yet night.

Two men in suits arrive, a recording machine is switched on. They introduce themselves but she doesn’t catch their names. Again, she feels distant and disconnected. Her real self is floating on the ceiling above, looking disdainfully at the grotesque spectacle beneath.

‘We know you were with him,’ they say.

‘I’ve nothing to say,’ she says. It’s all she says that evening, again and again. At least Joseph told her to do that if anything went wrong.

‘Your brother’s a Provo, your boyfriend’s a Provo. You were with him in that bedroom. You leave, a few minutes later he’s shot dead by a gang of your friends. You’re going down, Maire. You’ve ruined your life, your career, dishonoured your ma and da. Think about it as the long night passes.’

As they foresaw, darkness brings change. The unreality, the distancing recedes. She’s in a black tunnel with no light at the end. She knows she must not allow desperation to block her thoughts, but it’s hard to not keep seeing the puzzled, frightened expressions of her ma and da as she was led away. The hopes they had for her, the trust in their golden girl – all blown apart. Whatever happens now, there will always be a before and an after in her life.

She needs a life raft, a narrative that gives her a chance of survival. She tries to peer into that night from the other end of a telescope. To live it from his point of view. To imagine that he’s not a foolish man, but a bad man. Or a man made bad by alcohol and opportunity. She doesn’t like forcing her mind to work it through – but this is no time to be nice.

The next morning, she asks for a solicitor. They tell her all in good time. She tries to insist on her rights, they ignore her. Perhaps her request accelerates their reappearance for she’s back in the interview room within twenty minutes of making it. Their tone has hardened.

‘You’ve no way out, Maire,’ says the first man.

‘Your fingerprints are all over the room,’ says the second.

‘Christ, there’s even your saliva in his pubic hair.’

‘You filthy little slut, Maire. You really want that to come up in court? You want your ma and da to hear you were sucking the dick of some poor bastard you were setting up to be shot?’

She’s ready for them. ‘You’ve nothing. Sure I was with him. Sure he “picked me up”. Not me, him. Sure he insisted on coming home with me. But he was drunk, became violent. He was trying to rape me, so I ran. What the hell would you have done?’

‘Just at the very moment your good friend Joseph and his mates happen to arrive to murder him. What a coincidence, Maire. What a fluke of timing.’

‘I dunno anything ’bout that. You’ve no evidence to say that. I was in a bar, he picked me up. I was fool enough to go with him.’ Even if she’s not kidding herself, maybe she can somehow dent their certainty. She forces on, trying to convey confidence not desperation. ‘That’s my only crime. Maybe there was some eejits following him. So what? Nothing to do with me. He’s a bad man who tried to attack me. Look at the size of me – what chance would I have had? Now I wanna solicitor.’

‘You can have a solicitor, Maire. Won’t do you any good. There’s only one way out. You tell us everything you know about Joseph Kennedy and his friends – it’s OK, it’ll just be between youse and us, no one else’ll ever know – and maybe we’ll cut you some slack.’

‘It’s your life, Maire. Your future. Think about it,’ says the second man. They leave the room and she is escorted back to her cell, the barred door clanging shut behind her, the bare walls closing in on her life.

Later that day, she sees a solicitor and offers the same account she’s given her interrogators. They were right; the solicitor tells her the evidence, the coincidence of timing are stacked against her. The rape allegation gives her a chance, but only a small one. She’s come up with it late and there’s not even any bruising.

Maire knows only one thing for certain. It looks like they don’t have anything on Joseph. If she grasses – tells them Joseph did it – and his friends find out, she’s dead. There’s no greater sin than to turn informer. Not even Martin could save her – probably wouldn’t even want to. The story always has the same ending. A lonely grave in some anonymous damp patch of field.

The next day, another spell in the interview room, this time with her solicitor present. Her interrogators arrive together and say nothing. Instead they produce a pair of shoes from a bag, the shoes she wore on the night, and hand them to her.

‘We’ve cleaned them for you, Maire,’ says one. ‘You can have them back after the trial if your prison governor allows it.’

‘Careless of your friends to leave them behind,’ says the other. They walk out with a mocking grin.

‘Might be best to own up, Maire,’ says the solicitor later. ‘Say you knew nothing about the plan to kill him. We’d go for aiding and abetting an abduction. You might get away with five years. You’d only serve half.’

Her third night in the cell is the worst. All exits are closed and it seems a one-way street to conviction and branding as a criminal. If she confesses, the full dirtiness of what she’s done need not be revealed. Her ma and da can be spared that shame. After more than two decades of the ‘war’, her community will understand her getting caught up in it. Though what a pity, they’ll say, that clever little Maire McCartney, with the whole world at her fingertips, chose to spoil everything.

What if there’s not even that deal without their piece of flesh? Everything she knows about Joseph. The names of his friends. She feels a shiver of terror.

By the night’s end, she’s come to one conclusion. She’s not a committed warrior willing to spend a lifetime in prison for the ‘cause’. She doesn’t know where it will lead – but it’s time to negotiate and see what cards she’s got left to play.

A woman police officer arrives with breakfast.

‘I’ve been thinking,’ says Maire. ‘I wanna speak to my solicitor.’

‘That won’t be necessary,’ says the woman.

‘Whaddya mean? I’ve made a decision. I need to see her.’

‘No, you don’t. You’re leaving.’

‘What?’

‘I said you’re leaving. Seems like you’re a lucky girl.’

‘You joking? That’s bad taste . . .’

‘It’s not a joke, Maire. Pack your things, your da’s coming to fetch you.’

An hour later she finds herself walking past the front desk and out to the car park. It’s a journey of utter unreality. Maybe it’s some kind of trap. But there, in the flesh, is her da. Stephen has been allowed through the gates and security barriers and is waiting. As she nears the car, he gets out and hugs her. They drive in silence, no questions asked, no answers given. When they arrive home, it’s the same, her mother waiting quietly for her.

‘Welcome home, love.’ It’s all she says.

That evening, Martin comes for tea, the entrance as nonchalant as ever, the chitchat light and jokey. In front of her parents, no reference is made to the last three days. As they’re clearing the plates, she catches Martin nodding at them. They retreat to the kitchen to wash up. He closes the door behind them.

‘You’ll get your scholarship at Trinity, you’re that smart,’ he begins. ‘Working-class Catholic girl from the North – just what they need to move with the times. But you’ll leave this city and head down to Dublin now. I got friends who’ll put you up till we find you something permanent. Only a couple of months now. Maybe you can take some time abroad. I’ll see if I can raise some money.’

‘Did you know, Martin?’ she asks.

‘Know what?’ He sounds sharp, hard even. It’s unlike him.

‘Joseph said you approved it. I mean using me.’

He shakes his head slowly, closing his eyes and rubbing them with his hands. ‘Jesus, Maire, you should know me better. I’m not even going to discuss that.’

‘Well, he said you would.’

‘He said that?’

‘Yes.’ Her brother says nothing. ‘And the plan itself? Seducing him? Shooting him?’

‘Don’t go there. It’s past now.’

‘Joseph told me it was just to interrogate him.’

‘Fuck’s sake, Maire, you’re not that naïve.’

She wants to cry but mustn’t let herself. ‘I believed him, Martin. He promised. He said it was propaganda. To show they could run a Special Branch man out of town.’

‘He said that?’

‘Yes. Several times over.’

‘OK.’ He shakes his head and looks away from her. ‘Look here, Maire, I’m not going to piss on Joseph. He’s important in the movement. You can’t expect me to do that.’

‘I wanna see him. Ask him myself.’

‘That won’t be possible.’ His eyes pierce her in that way she knows he won’t be contradicted. She looks down, silent. ‘You’re not to see him again, Maire. There’s to be no contact ever again. From you or from him.’

She feels tears welling and tries to suppress them. There’s no point in arguing. Instead she asks the obvious question. ‘Why did they let me go?’

‘You’re small fry, they’ve bigger fish. Maybe they didn’t have enough on you. Maybe they wanna see where you’ll lead them. Use you as bait against your own side. That’s why you gotta leave. That’s a reason you can never see Joseph again.’ He pauses. ‘Not the only one, mind.’ She feels herself crushed. ‘And there’s another thing, Maire. Some will say they only let you go ’cos you grassed. Another reason you gotta go.’

‘Jesus, Martin, you should know me better than that.’ She grimaces. ‘Christ, that’s what you just said, isn’t it?’ He doesn’t answer – there’s nothing more to say. Her destiny, for now, is out of her hands. ‘OK, when?’

‘Tomorrow.’

‘Tomorrow!’

‘That’s right. You better start packing.’ Her brother grasps her shoulders and speaks with a searing passion. ‘You were never meant for this, Maire. You’re the lawyer. Maybe politics one day. You’re the ballot, not the bullet. Never forget that.’

The next morning, her father drives her to Victoria Bus Station to catch the express coach to Dublin. She’s been given an address and fifty pounds. She’s never felt so alone.

A few days later, Martin visits her in Dublin. It’s been arranged that she’ll live with a Mrs Bridget Ryan, whose daughter, Bernadette, is serving time for possessing explosives. As a contribution to her board and lodging, Maire will help look after Bernadette’s three children. The husband’s no good – he was once in the movement but forced out because of his drinking. The arrangement will last the full three years of Maire’s degree.

‘You can call it your prison if you want,’ says Martin, ‘but it’ll give you a better chance than the real thing. Now, you, work hard. Don’t socialize. Don’t look for friends. No boyfriends. Trust no one. Get your degree. And then get the fuck out of this island and make something of your life.’

As she watches him disappear, Maire begins to understand the worst of what she’s done. It’s not about being used, or luring a Brit peeler to his death, or shaming her parents, or losing Joseph.

It’s that she made an error. A huge, life-changing, potentially life-destroying error. If she’s managed to get away with it, if she’s been given a second chance, she promises herself one thing.

She will never again make such an error. Not ever.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/simon-berthon/a-secret-worth-killing-for/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Simon Berthon

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: ‘A stunning debut novel…It could not be more timely.’ – Gavin EslerSomebody knows where the bodies are buried…Newly-appointed Minister of State Anne-Marie Gallagher appears to have an unblemished record. Only she knows the truth. In the early 1990s, she was embroiled in the IRA’s violent past, and integral to a mission which went disastrously wrong.So far, skeletons have remained in their closets. But, unknown to Anne-Marie, DCI Jon Carne has just received an anonymous tip-off. The co-ordinates lead Carne to a body – badly decomposed after twenty-five years underground.When news of the discovery reaches Westminster, Anne-Marie knows that she is at risk of being exposed. And with Carne closing in, there’s not much time for the new minister to decide how far she’ll go to keep her past where it belongs…Power comes at a price in this sharp, smart political thriller – perfect for fans of Charles Cumming and Mick Herron.‘A stunning debut novel from a top TV producer, A Secret Worth Killing For takes us from the back streets of Belfast during the Troubles to power and parliament in London. It could not be more timely.’ – Gavin EslerPreviously published as Woman of State