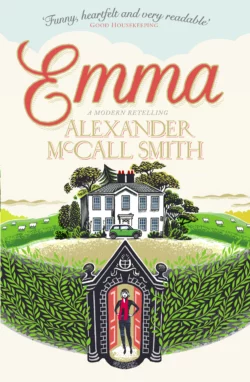

Emma

Alexander McCall Smith

Beloved and bestselling author Alexander McCall Smith lends his delightful touch to the Austen classic, Emma.‘It's comfort reading at its most soothing’ IndependentPrepare to meet a young woman who thinks she knows everything.Fresh from university, Emma Woodhouse triumphantly arrives home in Norfolk ready to embark on adult life with a splash. Not only has her sister, Isabella, been whisked away on a motorcycle up to London, but her astute governess, Miss Taylor is at a loose end, abandoned in the giant family pile, Hartfield, alongside Emma’s anxiety-ridden father. Someone is needed to rule the roost and young Emma is more than happy to oblige.As she gets her fledging design business off the ground, there is plenty to delight her in the buzzing little village of Highbury. At the helm of her own dinner parties and instructing her new little protégée, Harriet Smith, Emma reigns forth. But there is only one person who can play with Emma’s indestructible confidence, her old friend and inscrutable neighbour George Knightley – this time has Emma finally met her match?You don’t have to be in London to go to parties, find amusement or make trouble. Not if you’re Emma, the very big fish in the rather small pond. But for a young woman who knows everything, Emma has a lot to learn about herself.Ever alive to the uproarious nuances of human behaviour, and both the pleasures and pitfalls of village life, beloved author Alexander McCall Smith’s Emma is the busybody we all know and love, and a true modern delight.

Copyright (#u71490385-224c-5920-bc53-c4211a23fbd5)

The Borough Press

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2014

Copyright © Alexander McCall Smith 2014

Cover illustration © Iain McIntosh 2014

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Alexander McCall Smith asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007553884

Ebook Edition © June 2015 ISBN: 9780007553877

Version: 2016-08-25

Dedication (#u71490385-224c-5920-bc53-c4211a23fbd5)

For my daughters, Lucy and Emily

Contents

Cover (#ufa88f8c7-51a3-5c0e-985c-5d0e02c89ef1)

Title Page (#ue1a76009-ebc0-559b-a88b-8edf3c33d63e)

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

About the Author

Also by Alexander McCall Smith

About the Publisher

1 (#u71490385-224c-5920-bc53-c4211a23fbd5)

Emma Woodhouse’s father was brought into this world, blinking and confused, on one of those final nail-biting days of the Cuban Missile Crisis. It was a time of sustained anxiety for anybody who read a newspaper or listened to the news on the radio, and that included his mother, Mrs Florence Woodhouse, who was anxious at the best of times and even more so at the worst. What was the point of continuing the human race when nuclear self-immolation seemed to be such a real and imminent possibility? That was the question that occurred to Florence as she was admitted to the delivery ward of a small country hospital in Norfolk. American air bases lay not far away, making that part of England a prime target; their bombers, she had heard, were on the runway, ready to take off on missions that would bring about an end that would be as swift as it was awful, a matter of sudden blinding light, of dust and of darkness. Quite understandably, though, she had other, more pressing concerns at the time, and did not come up with an answer to her own question. Or perhaps her response was the act of giving birth itself, and the embracing, through tears of joy, of the small bundle of humanity presented to her by the midwife.

There are plenty of theories – not all of them supported by evidence – that the mother’s state of mind during pregnancy may affect the personality of the infant. There are also those who believe that playing Mozart to unborn children will lead to greater musicality, or reciting poetry through the mother’s stomach will increase the chances of having linguistically gifted children. That anxiety may be transmitted from mother to unborn baby is an altogether more believable claim, and indeed Henry Woodhouse appeared to be proof of this. From an early age he showed himself to be a fretful child, unwilling to take the risks that other boys delighted in and always interested in the results when his mother took his temperature with the clinical thermometer given to her by the district nurse.

‘Is it normal?’ was one the first sentences he uttered after he had begun to speak.

‘Absolutely normal,’ his mother would reply. ‘Ninety-eight point four. See.’

This disappointed him, and he always showed satisfaction when a doubtful reading required the insertion of the mercury bulb under his tongue a second time.

In due course this anxiety took the form of dietary fads, one after another, involving the rejection of various common foodstuffs (wheat, dairy products, and so on) and the enthusiastic embracing of rather more esoteric fare (royal jelly and malt biscuits being early favourites). These fads tended not to last long; by the time he was eighteen and ready to go to university, he was prepared to eat a normal vegetarian diet, provided it was supplemented by a pharmacopoeia of vitamin pills, omega oils, and assorted enzymes.

‘My son’, said his mother with a certain pride, ‘is a valetudinarian.’

That sent her friends to the dictionary, which gave her additional satisfaction. To dispatch one’s friends to a dictionary from time to time is one of the more sophisticated pleasures of life, but it is one that must be indulged in sparingly: to do it too often may result in accusations of having swallowed one’s own dictionary, which is not a compliment, whichever way one looks at it.

Henry Woodhouse – known to most as Mr Woodhouse – did not follow the career that had been expected of generations of young Woodhouses. While his father had assumed that his son would farm – in an entirely gentlemanly way – the six hundred acres that surrounded their house, Hartfield, the young man had other plans for himself.

‘I know what you expect,’ he said. ‘I know we’ve been here for the last four hundred years …’

‘Four hundred and eighteen,’ interjected his father.

‘Four hundred and eighteen, then. I know that. And I’m not saying that I want to go away altogether; it’s just that I want to do something else first. Then I can farm later on.’

His father sighed. ‘You would be a gentleman farmer,’ he said. ‘You do know that, don’t you?’

The young Woodhouse smiled. ‘I’ve never quite understood that concept. What exactly is the difference between a gentleman farmer and a farmer pure and simple?’

This question was a cause of some embarrassment to the older Woodhouse. ‘These matters shouldn’t need to be spelled out,’ he said. ‘Indeed, it’s not a question that one really likes to answer. And I’m surprised that you feel you need to ask it. A gentleman farmer …’ There was a pause, and then, ‘A gentleman farmer doesn’t actually farm, if you see what I mean. He doesn’t do the work himself. He usually has somebody else to do it for him, unless …’

‘Yes? Unless?’

‘Unless he doesn’t have the money. Then he has to do it himself.’

‘Like us? We don’t have the money, do we?’

‘No, we don’t. We did once, but not any more. And there’s nothing dishonourable about that. Having no money is perfectly honourable. In fact, having no money can often be a sign of good breeding.’

‘And a sign of poverty too?’

There was another sigh. ‘I feel we’re drawing this out somewhat. The point is that it would be a very fine thing if you chose to farm rather than to be … what was it you wanted to be?’

‘A design engineer.’

This was greeted with silence. ‘I see.’

‘It’s an important field. And we need to do more engineering design in this country or we’ll be even more thoroughly overtaken by the Germans.’ This, the young Woodhouse knew, was a fruitful line of argument to adopt with his father, who worried about the Germans and their twentieth-century lapses.

‘The Germans do a lot of that sort of thing?’

‘They do,’ he assured his father. ‘That’s why they’ve been so successful industrially. Their cars, you know, go on virtually forever, unlike so many of our own cars that I’m afraid won’t even start.’

‘Engineering design,’ muttered his father – and left it at that. But the argument had been won by the younger generation, and less than a year later Mr Woodhouse was enrolled as a student of his chosen subject, happy to be independent and away from home, doing what he had always wanted to do.

It proved to be a wise choice. After graduating, Mr Woodhouse joined a small firm in Norwich that specialised in the design of medical appliances. He enjoyed his work and was appreciated by his colleagues, even if they found him unduly anxious – some even said obsessive – when it came to risk assessment in the development of products. The work was interesting, but perhaps not challenging enough for the young engineer, and in his spare time he puzzled over various drawings and prototypes of his own invention, including a new and improved valve for the liquid-nitrogen cylinders used by dermatologists. This device was to prove suitable for other applications, and once he had patented it under his own name – rather to the annoyance of the firm, who mounted an unsuccessful legal challenge – he sold a production licence to a Dutch manufacturer. This provided him with financial security – with a fortune, in fact, with which he was able to renovate Hartfield, revitalise the farm and set up his increasingly infirm parents in the gatehouse. Their ill health unfortunately robbed them of a long retirement, and within a very short time Mr Woodhouse found himself the sole owner of Hartfield.

He had married by then, and in a way that surprised people. Everyone had assumed that the only person willing to take on this rather anxious and obsessed engineer would be either a woman of great charity – and there are plenty of women who seem prepared to marry a project husband – or a woman whose sole interest was financial. His wife was neither of these, being a warm and personable society beauty with a considerable private income of her own. Happily married, Mr Woodhouse enjoyed the existence of a country gentleman even if he continued with his engineering job for some years. A daughter was born in the year following their wedding – that was Isabella – and then another. This second daughter was Emma.

When Emma was five, Mrs Woodhouse died. Emma did not remember her mother. She remembered love, though, and a feeling of warmth. It was like remembering light, or the glow that sometimes persists after a light has gone out.

Had he not had the immediate responsibility of looking after two young daughters unaided, Mr Woodhouse could well have lapsed into a state of depression. With the irrationality of grief, he blamed himself for the loss of his wife. She may have died of exposure to a virulent meningeal infection as random and undetectable as any virus may be, but he still reproached himself for failing to ensure that her immune system was not in better order. If only he had insisted – and he would have had to insist most firmly – that she had followed the same regime of vitamin supplements as he did, then he believed she might have shrugged off the virus in its first exploratory forays. After all, the two of them breathed much the same air and ate the same things, so surely when she encountered the virus there was every chance that he must have done the same. In his case, however, Vitamins C and D had done their job, and if only he had persuaded her that taking fourteen pills a day was no great hardship, if one washed them down, as he always did, with breakfast orange juice … If only he had shown her the article from the Sunday Times which referred to work done in the United States on the efficacy of that particular combination of vitamins in ensuring a good immunological response. She scoffed at some of his theories – he knew that, and took her gentle scepticism in good spirit – but one did not scoff at the Sunday Times. If only he had taken the whole matter more seriously then their poor little Isabella and Emma would still have their mother and he would not be a widower.

Such guilty thoughts commonly accompany grief and equally commonly disappear once the rawness of loss is assuaged. This happened with Mr Woodhouse at roughly the right stage of the grieving process; now he found himself thinking not so much of the past but of how he might cope with the future. In the immediate aftermath of his wife’s death he had been inundated with offers of help from friends. He was well liked in the county because he was always supportive of local events, even if he rarely attended them. He had given generously to the appeal to raise money for a new scout hall, uncomplainingly paid his share of the cost of restoring the church roof after a gang of metal thieves had stripped it of its lead, and had cheerfully increased the value of the prize money that went with the Woodhouse Cup, a trophy instituted by his grandfather for the best ram at the local agricultural show. He never went to the local pub, but this was not taken as a sign of the standoffishness that infected some of the grander families in the neighbourhood, but as a concomitant of the eccentricity that people thought quite appropriate for a man who had, after all, invented something.

‘He invented something,’ one local explained to newcomers to the village. ‘You don’t see him about all that much – but he invented something all right. Made a ton of money from it, but good luck to him. If you can invent something and make sure nobody pinches the idea, then you’re in the money, big time.’

He was surprised – and touched – by the generosity of neighbours during those first few months after his wife’s death. There was a woman from the village, Mrs Firhill, who had helped them in the house since they had returned to Hartfield, and she now took it upon herself to do the shopping for the groceries as well as to cook all the meals. But even if day-to-day requirements were met in this way, there was still a constant stream of women who called in with covered plates and casserole dishes. Every Aga within a twenty-mile radius, it seemed, was now doing its part to keep the Woodhouse family fed, and at times this led to an overcrowding of the household’s two large freezers.

‘It’s not food they need,’ remarked Mrs Firhill to a friend, ‘it’s somebody to tuck little Emma in at night. It’s somebody to take a look in his wardrobe and chuck out some of the old clothes. It’s a wife and mother, if you ask me.’

‘That will come,’ said the friend. ‘He’s only in his thirties. And he’s not bad-looking in the right light.’

But Mrs Firhill, and most others who knew him, disagreed. There was a premature sense of defeat in Mr Woodhouse’s demeanour – the attitude of one who had done what he wanted to do in the first fifteen years of adult life and was now destined to live out the rest of his days in quiet contemplation and worry. Besides, it would try the patience of anybody, people felt, to live with that constant talk of vitamins and preventative measures for this and that: high-cocoa-content chocolate for strokes, New Zealand green-lipped mussel oil for rheumatism, and so on. It would not be easy to live with that no matter what the attractions of Hartfield (eleven bedrooms) and the financial ease that went with marrying its owner.

And in this assessment people were right: Mr Woodhouse had no intention of remarrying and firmly but politely rejected the dinner-party invitations that started to arrive nine months after his wife’s death. Nine months was just the right interval, people felt: remarriage, it was generally agreed, should never occur within a year of losing one’s spouse, which meant that the nine-month anniversary was just the right time to start positioning one’s candidate for the vacancy. But what could anybody do if the man in question simply declined every invitation on the grounds that he had a prior engagement?

‘There’s no need to lie,’ one rebuffed hostess remarked. ‘There are plenty of diplomatic excuses that can be used without telling downright lies. Besides, everybody knows he has no other engagements – he never leaves that place.’

The fact that no new Mrs Woodhouse was in contemplation meant that something had to be done about arranging care for Isabella and Emma. With this in mind, he consulted a woman friend from Holt, who had a reputation for knowing where one could find whatever it was one needed, whether it was a plumber, a girl to work in the stables, a carpet layer, or even a priest.

‘There’s a magazine,’ she said. ‘It’s called The Lady, and it’s – how shall we put it? – a bit old-fashioned, in a very nice sort of way. It’s the place where housekeepers and nannies advertise for jobs. There are always plenty of them. You’ll find somebody.’

He took her advice, and ordered a copy of The Lady. And just as he had been told, at the back of the magazine there were several pages of advertisements placed by domestic staff seeking vacancies. Discreet butlers disclosed that they were available, together with full references and criminal-record checks; trained nannies offered to care for children of all ages; and understanding companions promised to keep loneliness at bay in return for self-contained accommodation and all the usual perks.

He wondered who would still possibly require, or afford, a butler, but the fact that butlers appeared to exist suggested that there was still a need for them somewhere. It was easier to imagine the role played by ‘an energetic, middle-aged couple, with clean driving licences and an interest in cooking’; they would have no difficulty in finding something, he thought, as would the ‘young man prepared to do a bit of gardening and house maintenance in return for accommodation while at agricultural college’. And then, at the foot of the second page of these advertisements, there was a ‘well-educated young woman (26) wishing to find a suitable situation looking after children. Prepared to travel. Non-smoker. Vegetarian.’

It was the last of these qualifications that attracted his attention. He thought it hardly necessary these days to mention that one was a non-smoker; it would be assumed that any smoking would be done discreetly and away from others, it now being such a furtive pastime. Far more significant was the vegetarianism, which indicated, in Mr Woodhouse’s view, a sensible interest in nutrition. And as his eye returned to the text of the advertisement he saw that even if it was included in a column in which it was the sole entry, that column was headed ‘Governesses’.

Governesses, he thought, were perhaps on the same list of endangered species as butlers. He did not know anybody who had had a governess, although he had recently read that in Korea and Japan, where ambitious families took the education of their children in such deadly earnest, the practice of hiring resident tutors to give young children a competitive edge in examinations was widespread. These people, if female, could be called governesses, and were probably no different from the governesses that British families used to inflict on their children in the past. Of course the word had a distinctly archaic ring to it, being redolent of strictness and severity, but that need not necessarily be the case. He recalled that Maria von Trapp, after all, was a governess – as well as being a former nun – and she had been anything but severe. Would this well-educated young woman (26) possibly have a guitar – just as Maria von Trapp had? He smiled at the thought. He did not think he would make a very convincing Captain von Trapp.

The advertisement referred to a box number at the offices of The Lady and he wrote that afternoon asking the advertiser to contact him by telephone. Two days later, she called and introduced herself. He noticed, with pleasure, her slight Scottish accent: a Scottish governess, like a Scottish doctor, inspired confidence.

‘My name is Anne Taylor,’ she said. ‘You asked me to phone about the position of governess.’

They arranged an interview. Miss Taylor was available to travel to Norfolk at any time that was convenient to him. ‘I am not currently in a situation,’ she said. ‘I am therefore very flexible. There are plenty of trains from Edinburgh.’

He thought for a moment before replying, reflecting on the rather formal expression not currently in a situation. There were plenty of people not currently in a situation, and he himself was one of them. Some were in this position because they had tried, but failed, to get a situation, and others because they had a situation but had lost it because … There were any number of reasons, he imagined, for losing one’s situation, ranging from blameless misfortune to gross misconduct. There were even those who lost their situation because the police had caught up with them and unmasked them as fugitives on the run, as confidence tricksters, even as murderers. Murderers. He imagined that there were non-smoking, vegetarian murderers, just as there were nicotine-addicted carnivorous murderers, although he assumed that as a general rule murderers were not regular readers of The Lady magazine. Murderers probably read one of the lower tabloids – if they read a newspaper at all. The lower tabloids liked to report murders and murder trials, and that, for murderers, would have been light entertainment, rather like the social columns for the rest of us.

Miss Taylor noticed the slight hesitation. She was not to know, of course, of his tendency to anxiety and the way in which this operated to set him off on a trail of worries about remote and unlikely possibilities, worrying about murderers advertising in The Lady being a typical example.

‘Mr Woodhouse?’

‘Yes, I’m still here. Sorry, I was thinking.’

‘I could come at any time. Just tell me when would suit you, and I shall be there.’

‘Tomorrow,’ he said. ‘Tomorrow afternoon.’

‘I shall be there,’ she said, ‘once you have told me where there is.’

There was a delightful exactitude about the way in which she spoke, and he suspected, at that moment, that he and his daughters had found their governess.

2 (#u71490385-224c-5920-bc53-c4211a23fbd5)

It did not take Mr Woodhouse long to confirm his earlier suspicion that Anne Taylor would be exactly the right person for the job.

‘You seem to be entirely suitable,’ he said, a bare hour after her arrival for the interview. ‘All we need to do, I suppose, is to sort out when exactly you can start and, of course, the terms. I doubt if any of that will be problematic.’

Miss Taylor stared at him. She seemed surprised by what he had said, and for a moment Mr Woodhouse wondered whether he had unwittingly committed some solecism. He had been careful to call her Miss Taylor rather than Anne, even if that sounded rather formal – so it could not be that. Had he said anything else, then, to which she might have taken exception?

‘I have yet to indicate whether I shall accept,’ Miss Taylor said quietly. ‘One does not assume, surely, that the person whom one is interviewing wants the position until one’s asked her.’

‘But my dear Miss Taylor,’ exclaimed Mr Woodhouse, ‘how crassly insensitive of me. I was about to raise that very issue with you and—’

‘There is no need to resort to spin, Mr Woodhouse,’ interrupted Miss Taylor. ‘When one has said the wrong thing, I find that the best policy – beyond all doubt – is not to make things worse by claiming to be doing something one was not going to do.’ She paused. ‘Don’t you think?’

He was momentarily speechless. He had not imagined that the person he had invited for interview would end up lecturing him on how to behave, and for a moment he toyed with the idea of ending their meeting then and there. He might say: ‘Well, if that’s the sort of household you think you’re coming to …’ or, ‘My idea was that I should be employing somebody to teach the girls, not me.’ Or, simply, ‘If that’s the way you feel, then shall I run you back to the railway station?’

But he said none of this. The reality of the situation was that he had two young daughters to look after and he needed help. He could easily get some young woman from the village to take the job, but she would almost certainly feed them pizza out of a box and allow them to watch Australian soap operas on afternoon television. He knew that would happen, because that was what girls from the village did; he had seen it, or if he had not exactly seen it, Mrs Firhill had told him all about it. And even she was not above eating an occasional piece of pizza from a box; he had found an empty box a few weeks previously and it could only have come from her. This young woman, by contrast, was a graduate of the University of St Andrews, spoke French – as any self-respecting governess surely should do – and had a calm, self-assured manner that inspired utter confidence. He had to get her; he simply had to. So, after a minute or so of silence during which she continued to look at him unflinchingly, he mumbled an apology. ‘You’re right. Of course you’re right …’

To which she had replied, ‘Yes, I know.’

He opened his mouth to protest, but she cut him short. ‘As it happens, I think this job would suit me very well. What I suggest is a three-month trial period during which you can decide whether you can bear me.’ And here she smiled; and he did too, nervously. ‘And whether I can bear you. Once that hurdle has been surmounted, we could take it from there.’ She paused. ‘I do like the girls, by the way.’

He showed his relief with a broad smile. ‘I’m sure that’s reciprocated,’ he said.

Mrs Firhill had been on hand to help with the encounter and had shepherded the girls into the playroom while this discussion with Miss Taylor took place. Mr Woodhouse could tell from his housekeeper’s demeanour that she approved of Miss Taylor, and in his mind that provided the final, clinching endorsement of the arrangement. Accepting Miss Taylor’s suggestion, he called the girls back into the room and explained to them, in Miss Taylor’s presence, that she would be coming to stay with them and that he was sure that they would all be very happy.

‘But we’re happy already,’ said Isabella, giving Miss Taylor a sideways glance.

‘Then you’ll be even happier,’ said Mr Woodhouse quickly. ‘But now, Miss Taylor, we must all have a cup of tea. I prefer camomile myself, but we can offer you ordinary tea if you prefer.’

‘Camomile has some very beneficial properties,’ said Miss Taylor.

Mr Woodhouse beamed with pleasure.

The briskness with which Miss Taylor moved into Hartfield surprised Mr Woodhouse – she arrived, with several suitcases of possessions, within a week of her interview – but it was as nothing to the speed with which she reorganised the lives of the two girls. In spite of her earlier enthusiasm for the appointment, Mrs Firhill took the view that she was moving too quickly: ‘Children don’t like change. They want things to remain the same – everybody knows that, except this woman, or so it seems.’ These were dark notes of caution, uttered with a toss of the head in the direction of the attic bedroom that Miss Taylor now occupied, but the housekeeper, too, was in for a surprise; neither Isabella nor Emma resisted Miss Taylor, and from the very beginning embraced the ways of their governess with enthusiasm. The new regime involved new and exotic academic subjects – French and handwriting were Miss Taylor’s intellectual priorities – as well as a programme of physical exercise and, most importantly, riotous, vaguely anarchic fun. A bolster bar was erected in the nursery, under which soft cushions were arranged. The girls were then invited to sit astride each end of this bar, armed with down-stuffed pillows. The game was to hit each other with these pillows until one of them was dislodged and fell on to a cushion or occasionally the bare floor below. In order to level the playing field that age tilted in Isabella’s favour, Emma was allowed to use two hands, while her sister was required to keep one behind her back. White feathers flew everywhere like snowflakes in a storm, and the shrieks of laughter penetrated even Mr Woodhouse’s study, where he sat engrossed in the latest crop of scientific papers in the dietary and nutritional journals to which he subscribed.

He was bemused by the changes that he saw about him, by the constant activity, by the new enthusiasms. He watched as scrapbooks filled with cuttings from magazines and papers; as cut-out dolls found their way on to every table; as rescued animals and birds took up residence in shoe-boxes lined up at the base of the warmth-dispensing Aga; as the current of life, which had grown so sluggish after the death of his wife, now began to course once more through the house. He welcomed all of this, even if it failed to relieve his own anxiety. It was all very well to be cheerful and optimistic when one was the girls’ age, but what if you were getting to the age – as he was – when life for the immune system became much more challenging? There were dangers all about, not least those identified by the medical statisticians, whose grim work it was to reveal just how likely it was that something could go wrong. And every time he contemplated the results of new research, there was the task of adjusting his regime to increase his level of exercise – or reduce it, depending on the balance of benefit between coronary health and wear and tear on the joints; to increase the number of supplements – or decrease it, depending on whether a novel product, attractive in itself, was likely to react badly with something that he was already taking. Such balancing was an almost full-time job, and left little time for other pursuits, such as the assessment of engineering risk – a task that he was well qualified to carry out but that could be inordinately demanding if one took it seriously, as Mr Woodhouse certainly did.

The purchase of a new lawnmower was an example of just how complicated this could be. Hartfield was surrounded by extensive lawns that gave way, to the east, to a large shrubbery, much loved by the girls for games of hide-and-seek. Those games themselves had been the cause of some anxiety, as it was always possible that hiding under a rhododendron bush might bring one into contact with spiders, for whom the shade and dryness of the sub-rhododendron environment might be irresistible. Spiders had to live somewhere, and under rhododendron bushes could be just the place for them.

Mr Woodhouse had heard people saying that there were no poisonous spiders in England. He knew this to be untrue, and had once or twice corrected those who made this false assertion. On one occasion he had gone to the length of ringing up during a local radio phone-in programme when a gardening expert had reassured a caller that there were no spiders to worry about in English gardens.

‘That’s unfortunately untrue,’ said Mr Woodhouse to the show’s host. ‘There are several species of spider in England that have a very painful bite. The raft spider, for instance, or the yard spider can both administer a toxic bite that will leave you in no doubt about having encountered something nasty.’

The host had listened with interest and then asked whether Mr Woodhouse had ever been bitten himself.

‘Not personally,’ came the answer.

‘Or known anybody who’s been bitten?’

‘Not exactly.’

‘Well then,’ said the host, ‘I don’t think we need worry the listeners too much about what they might bump into in their gardens, do you?’

‘Oh, I do,’ said Mr Woodhouse. ‘A false sense of security is a very dangerous thing, let me assure you.’

His concern over spiders was fuelled by the information the Sydney funnel-web spider, known to be one of the most dangerous spiders in the world, had taken up residence in the London Docks and was apparently thriving in its new habitat. That did not surprise Mr Woodhouse at all, who had long thought that the ease with which goods and people could now be transported about the world was an invitation to every dangerous species to take up residence in places where they had previously been unknown. It was inevitable, he thought, that at least some travellers from Australia would bring in their luggage spiders that had taken refuge there while their suitcases were being packed. If bedbugs could do it – and they did – then why should spiders resist the temptation? He shook his head sadly; the green and pleasant land of Blake’s imagining would not be green and pleasant for long at that rate. And if spiders could do it, what about sharks, who had to swim no more than a few extra nautical miles to arrive at British beaches? Or snakes, who had only to slither into a bunch of bananas in Central America to arrive within days on the tables of people thousands of miles away? And what if they met, en route, an attractive snake of the opposite sex? Before you knew it you would have a deadly fer-de-lance population comfortably established in Norfolk. That would give those complacent gardening experts on the radio something to think about.

‘Nonsense,’ snapped Miss Taylor when he raised the issue of spiders under rhododendron bushes and queried whether the girls might not be banned from going into the shrubbery to play their games. ‘We cannot wrap ourselves in cotton wool; just imagine what we would look like. Moreover, girls and spiders have co-existed for thousands of years, as is established, I would have thought, by the continued survival of the two species: the British girl and the British spider. Cadit quaestio.’

The expression, cadit quaestio – the question falls away – was one that Miss Taylor often used when she wished to put an end to a discussion. It was virtually unanswerable, as it is difficult to persist with a question that has been declared no longer to exist – anybody doing so seems so unreasonable – and it was now being used by the girls themselves, even by Emma. She had difficulty getting her tongue round the Latin but had nonetheless recently answered ‘cadit quaestio’ when he had asked her whether she had taken her daily fish-oil supplement.

The size of the lawns around Hartfield meant that a mechanical lawnmower was required. For years Sid, who helped with the farm and with some of the tasks associated with the garden, had used an ancient petrol-driven lawnmower that he pushed before him on creaky and increasingly dangerous handles. Mr Woodhouse had decided to replace this, and had looked into the possibility of a small tractor under which was fitted a powerful rotary blade. This would enable Sid to sit on a well-sprung seat as he drove the lawnmower up and down the lawn, leaving behind him neat stripes of barbered grass.

The tractor brochure portrayed this scene as a rural idyll. A contented middle-aged man sat on his small tractor, a vast swathe of well-cut grass behind him. The sky above was blue and cloudless; in the distance, on the veranda of a summer house, an attractive wife – at least ten years younger than the man on the lawnmower – waited to dispense glasses of lemonade to her hard-working husband. But Mr Woodhouse was not so easily fooled. What if you put your foot just a few inches under the cover of the blade? What if you fell off the tractor because the ground was uneven – not everyone had even lawns – and your fingers, or even your whole hand, were to get in the way of the tractor and its vicious blade? Or what if a dog bounded up to greet its owner on the tractor and had its tail cut off? The woman dispensing lemonade so reassuringly would shriek and run out, only to slip under the lawnmower and be sliced like a salami in a delicatessen. It was all very well, he told himself, trying to avoid these possibilities and pretending that nothing like that would happen, but somebody had to think about them.

The enthusiasm that Isabella and Emma felt for Miss Taylor proved to be infectious. Although Mrs Firhill had misgivings about the governess and the pace with which she introduced her changes, she found it hard to disapprove of a woman who, in spite of a tendency to state her views as if they were beyond argument, was warm and generous in her dealings with others. The conviction that she was right – the firm disapproval of those she deemed to be slovenly in their intellectual or physical habits – was something that Mrs Firhill believed to be associated with her having come from Edinburgh.

‘They’re all like that,’ a friend said to her. ‘I’ve been up there – I know. They think the rest of us very sloppy. They are very judgemental people.’

‘I hope that it doesn’t rub off on the girls,’ said Mrs Firhill. ‘But I suppose it will. There’s Emma already saying cadit quaestio – and she’s only six.’

‘Oh, well,’ said the friend. ‘Perhaps it’s the best of both worlds – to be brought up Scottish but to live somewhere ever so slightly warmer.’

Mrs Firhill nodded – and thought. There was already something about Emma that worried her even if she was unable to put her finger on what it was. Was it headstrongness – a trait that you found in certain children who simply would not be told and who insisted on doing things their way? Her cousin Else’s son had been like that, and was always getting into trouble at school – unnecessarily so, she thought. Or was it something rather different – something to do with the desire to control? There were some children who were, to put it simply, bossy, and little girls tended to be rather more prone to this than little boys – or so Mrs Firhill believed. Yes, she thought, that was it. Emma was a controller, and it was perfectly possible that Miss Taylor’s influence would make it worse: if you were brought up to believe that there was a very clear right way and wrong way of doing things, then you might well try to make other people do things your way rather than theirs.

Once Mrs Firhill had identified the issue, the signs of Emma’s desire to control others seemed to become more and more obvious. On one occasion Mrs Firhill came across her playing by herself in the playroom, Isabella being in bed that day with a heavy cold. In a corner of the room was the girls’ doll’s house – an ancient construction that had been discovered, dusty and discoloured, in the attic. Now with its walls repainted and repapered, the house was once again in use, filled with tiny furniture and a family of dolls that the girls shared between them. Long hours were spent attending to this house and in moving the dolls from one room to another in accordance with the tides of doll private life that no adult could fathom.

Unseen by Emma, Mrs Firhill watched for a few minutes while Emma addressed her dolls and tidied their rooms.

‘You are going to have stay in your room until further notice,’ she scolded one, a small boy doll clad in a Breton sailor’s blue-and-white jersey. ‘And you,’ she said to another one, a thin doll with arms out of which the stuffing had begun to leak, ‘you are never going to find a husband unless you do as I say.’

Mrs Firhill drew in her breath. It would have been very easy to laugh at this tiny display of directing behaviour, but she felt somehow that it was not a laughing matter. What she was witnessing was a perfect revelation of a character trait: Emma must want to control people if this was the way she treated her dolls. Bossy little madam, thought Mrs Firhill. But then she added – to herself, of course – without a mother. And that, she realised, changed things.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/alexander-smith-mccall/emma/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Alexander Smith

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Beloved and bestselling author Alexander McCall Smith lends his delightful touch to the Austen classic, Emma.‘It′s comfort reading at its most soothing’ IndependentPrepare to meet a young woman who thinks she knows everything.Fresh from university, Emma Woodhouse triumphantly arrives home in Norfolk ready to embark on adult life with a splash. Not only has her sister, Isabella, been whisked away on a motorcycle up to London, but her astute governess, Miss Taylor is at a loose end, abandoned in the giant family pile, Hartfield, alongside Emma’s anxiety-ridden father. Someone is needed to rule the roost and young Emma is more than happy to oblige.As she gets her fledging design business off the ground, there is plenty to delight her in the buzzing little village of Highbury. At the helm of her own dinner parties and instructing her new little protégée, Harriet Smith, Emma reigns forth. But there is only one person who can play with Emma’s indestructible confidence, her old friend and inscrutable neighbour George Knightley – this time has Emma finally met her match?You don’t have to be in London to go to parties, find amusement or make trouble. Not if you’re Emma, the very big fish in the rather small pond. But for a young woman who knows everything, Emma has a lot to learn about herself.Ever alive to the uproarious nuances of human behaviour, and both the pleasures and pitfalls of village life, beloved author Alexander McCall Smith’s Emma is the busybody we all know and love, and a true modern delight.