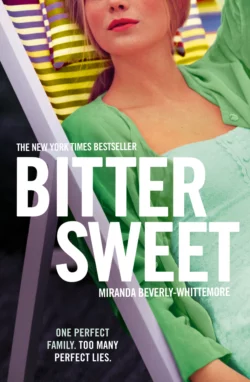

Bittersweet

Miranda Beverly-Whittemore

One perfect family.Too many perfect lies.Small-town girl Mabel Dagmar is out of her depth. At her elite East Coast college, unversed in the nuances of casual privilege, she is ignored, especially by her dormmate, Ev Winslow, whose pedigree disguises a chequered past. Then out of nowhere Ev softens and Mabel finds herself entering the world of the elite, with an invitation to the Winslows’ private estate, Winloch, that very summer.Days spent swimming in watery coves evaporate into nights at glamorous cocktail parties. And as the formality melts away with one Winslow brother in particular, Mabel is left to think that her summer has all but become a golden dream.But when Mabel looks a little closer at the Winslows, probing beneath their glossy exterior, what she uncovers in their past is almost as shocking as what she finds out about their present. Beneath the beauty is a rotten core.And not everyone is quite as they seem…

Copyright (#ue039d61b-4f81-558e-9d0a-3049c9a25ac5)

The Borough Press

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London, SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by The Borough Press 2014

Copyright © Miranda Beverly-Whittemore 2014

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Cover photographs © Morgan Norman / Gallery Stock (front cover); Shutterstock.com (http://Shutterstock.com) (back cover)

Miranda Beverly-Whittemore asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007536672

Ebook Edition © 2014 ISBN: 9780007536665

Version: 2015-04-23

Dedication (#ue039d61b-4f81-558e-9d0a-3049c9a25ac5)

For Ba and Fa, who shared the land,

and Q, who gave me the world

Contents

Cover (#u19b30a80-22a6-5aa0-ac9f-cbcfa9872efd)

Title Page (#u8d3ce059-87d0-5350-8e18-40ca8a3f4961)

Copyright

Dedication

February

Chapter One: The Roommate

Chapter Two: The Party

Chapter Three: The Invitation

June

Chapter Four: The Call

Chapter Five: The Journey

Chapter Six: The Window

Chapter Seven: The Cleanup

Chapter Eight: The Stroll

Chapter Nine: The Aunt

Chapter Ten: The Inspection

Chapter Eleven: The Brothers

Chapter Twelve: The Painting

Chapter Thirteen: The Inevitable

Chapter Fourteen: The Collage

Chapter Fifteen: The Girl

Chapter Sixteen: The Rocks

Chapter Seventeen: The Voyage

Chapter Eighteen: The Rescue

Chapter Nineteen: The Discovery

Chapter Twenty: The Wedding

Chapter Twenty-One: The Kiss

July

Chapter Twenty-Two: The Secret

Chapter Twenty-Three: The Book

Chapter Twenty-Four: The Turtles

Chapter Twenty-Five: The Evening

Chapter Twenty-Six: The Mother

Chapter Twenty-Seven: The Festivities

Chapter Twenty-Eight: The Fireworks

Chapter Twenty-Nine: The Enigma

Chapter Thirty: The Apology

Chapter Thirty-One: The Date

Chapter Thirty-Two: The Scene

Chapter Thirty-Three: The Swim

Chapter Thirty-Four: The Morning

Chapter Thirty-Five: The Pile

Chapter Thirty-Six: The Threat

Chapter Thirty-Seven: The Woods

Chapter Thirty-Eight: The Sister

Chapter Thirty-Nine: The Revelation

Chapter Forty: The Return

Chapter Forty-One: The Proof

Chapter Forty-Two: The Good-bye

Chapter Forty-Three: The Waiting

Chapter Forty-Four: The Widow

August

Chapter Forty-Five: The Aftermath

Chapter Forty-Six: The Row

Chapter Forty-Seven: The Picnic

Chapter Forty-Eight: The Key

Chapter Forty-Nine: The Theft

Chapter Fifty: The Director

Chapter Fifty-One: The Camp

Chapter Fifty-Two: The Witness

Chapter Fifty-Three: The Jailbreak

Chapter Fifty-Four: The Memory

Chapter Fifty-Five: The Handoff

Chapter Fifty-Six: The Service

Chapter Fifty-Seven: The Truth

Chapter Fifty-Eight: The Curse

Chapter Fifty-Nine: The Chaperone

June

Chapter Sixty: The End

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Miranda Beverly-Whittemore

About the Publisher

February (#ue039d61b-4f81-558e-9d0a-3049c9a25ac5)

CHAPTER ONE (#ue039d61b-4f81-558e-9d0a-3049c9a25ac5)

The Roommate (#ue039d61b-4f81-558e-9d0a-3049c9a25ac5)

BEFORE SHE LOATHED ME, before she loved me, Genevra Katherine Winslow didn’t know that I existed. That’s hyperbolic, of course; by February, student housing had required us to share a hot shoe box of a room for nearly six months, so she must have gathered I was a physical reality (if only because I coughed every time she smoked her Kools atop the bunk bed), but until the day Ev asked me to accompany her to Winloch, I was accustomed to her regarding me as she would a hideously upholstered armchair – something in her way, to be utilized when absolutely necessary, but certainly not what she’d have chosen herself.

It was colder that winter than I knew cold could be, even though the girl from Minnesota down the hall declared it ‘nothing.’ Out in Oregon, snow had been a gift, a two-day dusting earned by enduring months of gray, dripping sky. But the wind whipping up the Hudson from the city was so vehement that even my bone marrow froze. Every morning, I hunkered under my duvet, unsure of how I’d make it to my 9:00 a.m. Latin class. The clouds spilled endless white and Ev slept in.

She slept in with the exception of the first subzero day of the semester. That morning, she squinted at me pulling on the flimsy rubber galoshes my mother had nabbed at Value Village and, without saying a word, clambered down from her bunk, opened our closet, and plopped her brand-new pair of fur-lined L.L.Bean duck boots at my feet. ‘Take them,’ she commanded, swaying in her silk nightgown above me. What to make of this unusually generous offer? I touched the leather – it was as buttery as it looked.

‘I mean it.’ She climbed back into bed. ‘If you think I’m going out in that, in those, you’re deranged.’

Inspired by her act of generosity, by the belief that boots must be broken in (and spurred on by the daily terror of a stockpiling peasant – sure, at any moment, I’d be found undeserving and sent packing), I forced my frigid body out across the residential quad. Through freezing rain, hail, and snow I persevered, my tubby legs and sheer weight landing me square in the middle of every available snowdrift. I squinted up at Ev’s distracted, willowy silhouette smoking from our window, and thanked the gods she didn’t look down.

Ev wore a camel-hair coat, drank absinthe at underground clubs in Manhattan, and danced naked atop Main Gate because someone dared her. She had come of age in boarding school and rehab. Her lipsticked friends breezed through our stifling dorm room with the promise of something better; my version of socializing was curling up with a copy of Jane Eyre after a study break hosted by the house fellows. Whole weeks went by when I didn’t see her once. On the few occasions inclement weather hijacked her plans, she instructed me in the ways of the world: (1) drink only hard alcohol at parties because it won’t make you fat (although she pursed her lips whenever she said the word in front of me, she didn’t shy from saying it), and (2) close your eyes if you ever have to put a penis in your mouth.

‘Don’t expect your roommate to be your best friend,’ my mother had offered in the bold voice she reserved for me alone, just before I flew east. Back in August, watching the TSA guy riffle through my granny underpants while my mother waved a frantic good-bye, I shelved her comment in the category of Insulting. I knew all too well that my parents wouldn’t mind if I failed college and had to return to clean other people’s clothes for the rest of my life; it was a fate they – or at least my father – believed I’d sealed for myself only six years before. But by early February, I understood what my mother had really meant; scholarship girls aren’t meant to slumber beside the scions of America because doing so whets insatiable appetites.

The end of the year was in sight, and I felt sure Ev and I had secured our roles: she tolerated me, while I pretended to disdain everything she stood for. So it came as a shock, that first week of February, to receive a creamy, ivory envelope in my campus mailbox, my name penned in India ink across its matte expanse. Inside, I found an invitation to the college president’s reception in honor of Ev’s eighteenth birthday, to be held at the campus art museum at the end of the month. Apparently, Genevra Katherine Winslow was donating a Degas.

Any witness to me thrusting that envelope into my parka pocket in the boisterous mail room might have guessed that humble old Mabel Dagmar was embarrassed by the showy decadence, but it was just the opposite – I wanted to keep the exclusive, honeyed sensation of the invitation to myself, lest I discover it was a mistake, or that every single mailbox held one. The gently nubbled paper stock kept my hand warm all day. When I returned to the room, I made sure to leave the envelope prominently on my desk, where Ev liked to keep her ashtray, just below the only picture she had posted in our room, of a good sixty people – young and old, all nearly as good-looking and naturally blond as Ev, all dressed entirely in white – in front of a grand summer cottage. The Winslows’ white clothing was informal, but it wasn’t the kind of casual my family sported (Disneyland T-shirts, potbellies, cans of Heineken). Ev’s family was lean, tan, and smiling. Collared shirts, crisp cotton dresses, eyelet socks on the French-braided little girls. I was grateful she had put the picture over my desk; I had ample time to study and admire it.

It was three days before she noticed the envelope. She was smoking atop her bunk – the room filling with acrid haze as I puffed on my inhaler, huddled over a calculus set just below her – when she let out a groan of recognition, hopping down from her bed and plucking up the invitation. ‘You’re not coming to this, are you?’ she asked, waving it around. She sounded horrified at the possibility, her rosebud lips turned down in a distant cousin of ugly – for truly, even in disdain and dorm-room dishevelment, Ev was a sight to behold.

‘I thought I might,’ I answered meekly, not letting on that I’d been simultaneously ecstatic and fretful over what I would ever wear to such an event, not to mention how I would do anything attractive with my limp hair.

Her long fingers flung the envelope back onto my desk. ‘It’s going to be ghastly. Mum and Daddy are angry I’m not donating to the Met, so they won’t let me invite any of my friends, of course.’

‘Of course.’ I tried not to sound wounded.

‘I didn’t mean it like that,’ she snapped, before dropping back into my desk chair and tipping her porcelain face toward the ceiling, frowning at the crack in the plaster.

‘Weren’t you the one who invited me?’ I dared to ask.

‘No.’ She giggled, as though my mistake was an adorable transgression. ‘Mum always asks the roommates. It’s supposed to make it feel so much more … democratic.’ She saw the look on my face, then added, ‘I don’t even want to be there; there’s no reason you should.’ She reached for her Mason Pearson hairbrush and pulled it over her scalp. The boar bristles made a full, thick sound as she groomed herself, golden hair glistening.

‘I won’t go,’ I offered, the disappointment in my voice betraying me. I turned back to my math. It was better not to go – I would have embarrassed myself. But by then, Ev was looking at me, and continuing to stare – her eyes boring into my face – until I could bear her gaze no more. ‘What?’ I asked, testing her with irritation (but not too much; I could hardly blame her for not wanting me at such an elegant affair).

‘You know about art, right?’ she asked, the sudden sweetness in her voice drawing me out. ‘You’re thinking of majoring in art history?’

I was surprised – I had no idea Ev had any notion of my interests. And although, in truth, I’d given up the thought of becoming an art history major – too many hours taking notes in dark rooms, and I wasn’t much for memorization, and I was falling in love with the likes of Shakespeare and Milton – I saw clearly that an interest in art was my ticket in.

‘I think.’

Ev beamed, her smile a break between thunderheads. ‘We’ll make you a dress,’ she said, clapping. ‘You look pretty in blue.’

She’d noticed.

CHAPTER TWO (#ue039d61b-4f81-558e-9d0a-3049c9a25ac5)

The Party (#ue039d61b-4f81-558e-9d0a-3049c9a25ac5)

THREE WEEKS LATER, I found myself standing in the main, glassy hall of the campus art museum, a silk dress the color of the sea deftly draped and seamed so I appeared twenty pounds lighter. At my elbow stood Ev, in a column of champagne shantung. She looked like a princess, and, as for a princess, the rules did not apply; we held full wineglasses with no regard for the law, and no one, not the trustees or professors or senior art history majors who paraded by, each taking the time to win her smile, batted an eye as we sipped the alcohol. A single violinist teased out a mournful melody in the far corner of the room. The president – a doyenne of the first degree, her hair a helmet of gray, her smile practiced in the art of raising institutional monies – hovered close at hand. Ev introduced me to spare herself the older woman’s attention, but I was flattered by the president’s interest in my studies (‘I’m sure we can get you into that upper-level Milton seminar’), though eager to extract myself from her company in the interest of more time with Ev.

Ev whispered each guest’s name into the whorl of my ear – how she kept track of them, even now I do not know, except that she had been bred for it – and I realized that somehow, inexplicably, I had ended up the guest of honor’s guest of honor. Ev may have beguiled each attendee, but it was with me that she shared her most private observations (‘Assistant Professor Oakley – he’s slept with everyone,’ ‘Amanda Wyn – major eating disorder’). Taking it all in, I couldn’t imagine why she wouldn’t want this: the Degas (a ballerina bent over toe shoes at the edge of a stage), the fawning adults, the celebration of birth and tradition. As much as she insisted she longed for the evening to be over, so did I drink it in, knowing all too well that tomorrow I’d be back in her winter boots, slogging through the sleet, praying my financial aid check would come so I could buy myself a pair of mittens.

The doors to the main hall opened and the president rushed to greet the newest, final guests, parting the crowd. My diminutive stature has never given me advantage, and I strained to see who had arrived – a movie star? an influential artist? – only someone important could have stirred up such a reaction in that academic group.

‘Who is it?’ I whispered, straining on tiptoe.

Ev downed her second gin and tonic. ‘My parents.’

Birch and Tilde Winslow were the most glamorous people I’d ever seen: polished, buffed, and obviously made of different stuff than I.

Tilde was young – or at least younger than my mother. She had Ev’s swan-like neck, topped off by a sharper, less exquisite face, although, make no mistake, Tilde Winslow was a beauty. She was skinny, too skinny, and though I recognized in her the signs of years of calorie counting, I’ll admit that I admired what the deprivation had done for her – accentuating her biceps, defining the lines of her jaw. Her cheekbones cut like razors across her face. She wore a dress of emerald dupioni silk, done at the waist with a sapphire brooch the size of a child’s hand. Her white-blond hair was swept into a chignon.

Birch was older – Tilde’s senior by a good twenty years – and he had the unmovable paunch of a man in his seventies. But the rest of him was lean. His face did not seem grandfatherly at all; it was handsome and youthful, his crystal-blue eyes set like jewels inside the dark, long eyelashes that Ev had inherited from his line. As he and Tilde made their slow, determined way to us, he shook hands like a politician, offering cracks and quips that jollified the crowd. Beside him, Tilde was his polar opposite. She hardly mustered a smile, and, when they were finally to us, she looked me over as though I were a dray horse brought in for plowing.

‘Genevra,’ she acknowledged, once satisfied I had nothing to offer.

‘Mum.’ I caught the tightness in Ev’s voice, which melted as soon as her father placed his arm around her shoulder.

‘Happy birthday, freckles,’ he whispered into her perfect ear, tapping her on the nose. Ev blushed. ‘And who,’ he asked, holding out his hand to me, ‘is this?’

‘This is Mabel.’

‘The roommate!’ he exclaimed. ‘Miss Dagmar, the pleasure is all mine.’ He swallowed that awful g at the center of my name and ended with a flourish by rolling the r just so. For once, my name sounded delicate. He kissed my hand.

Tilde offered a thin smile. ‘Perhaps you can tell us, Mabel, where our daughter was over Christmas break.’ Her voice was reedy and thin, with a brief trace of an accent, indistinguishable as pedigreed or foreign.

Ev’s face registered momentary panic.

‘She was with me,’ I answered.

‘With you?’ Tilde asked, seeming to fill with genuine amusement. ‘And what, pray tell, was she doing with you?’

‘We were visiting my aunt in Baltimore.’

‘Baltimore! This is getting better by the minute.’

‘It was lovely, Mum. I told you – I was well taken care of.’

Tilde raised one eyebrow, casting a glance over both of us, before turning to the curator at her arm and asking whether the Rodins were on display. Ev placed her hand on my shoulder and squeezed.

I had no idea where Ev had been over Christmas break – she certainly hadn’t been with me. But I wasn’t lying completely – I’d been in Baltimore, forced to endure my Aunt Jeanne’s company for the single, miserable week during which the college dorms had been shuttered. Visiting Aunt Jeanne at twelve on the one adventure my mother and I had ever taken together – a five-day East Coast foray – had been the highlight of my preteen existence. My memories of that visit were murky, given that they were from Before Everything Changed, but they were happy. Aunt Jeanne had seemed glamorous, a carefree counterpoint to my laden, dutiful mother. We’d eaten Maryland crab and gone to the diner for sundaes.

But whether Aunt Jeanne had changed or my eye had become considerably more nuanced in the intervening years, what I discovered that first December of college was that I’d rather shoot myself in the head than become her. She lived in a dank, cat-infested condo and seemed puzzled whenever I suggested we go to the Smithsonian. She ate TV dinners and dozed off in front of midnight infomercials. As Tilde turned from us, I remembered, with horror, the promise my aunt had extracted from me at the end of my stay (all she’d had to do was invoke my abandoned mother’s name): two interminable weeks in May before heading back to Oregon. I dared to dream that Ev would come with me. She’d be the key to surviving ThePrice Is Right and the tickle of cat hair at the back of the throat.

‘Mabel’s studying art history.’ Ev nudged me toward her father. ‘She loves the Degas.’

‘Do you?’ Birch asked. ‘You can get closer to it, you know. It’s still ours.’

I glanced at the well-lit painting propped upon a simple easel. Only a few feet separated me from it, but it may as well have been a million. ‘Thank you,’ I demurred.

‘So you’re majoring in art history?’

‘I thought you were majoring in English,’ the president interrupted, suddenly at my side.

I grew red-faced in the spotlight, and what felt like being caught in a lie. ‘Oh,’ I stammered, ‘I like both subjects – I really do – I’m only a first-year, you know, and—’

‘Well, you can’t have literature without art, can you?’ Birch asked warmly, opening the circle to a few of Ev’s admirers. He squeezed his daughter’s shoulder. ‘When this one was barely five we took the children to Firenze, and she could not get enough of Medusa’s head at the Uffizi. And Judith and Holofernes! Children love such gruesome tales.’ Everyone laughed. I was invisible again. Birch caught my eye for the briefest of seconds and winked. I felt myself flush gratefully.

After the president’s welcome toast, and the passed hors d’oeuvres, and the birthday cupcakes frosted with buttercream that matched my dress, after Ev made a little speech about how the college had made her feel so at home, and that she hoped the Degas would live happily at the museum for many years to come, Birch raised a glass, garnering the room’s attention.

‘It has been the Winslow tradition,’ he began, as though we were all part of his family, ‘for each of the children, upon reaching eighteen, to donate a painting to an institution of his or her choice. My sons chose the Metropolitan Museum. My daughter chose a former women’s college.’ This was met with boisterous laughter. Birch tipped his glass toward the president in rhetorical apology. He cleared his throat as a wry smile faded from his lips. ‘Perhaps the tradition sprang from wanting to give each child a healthy deduction on their first tax return’ – again, he was met with laughter – ‘but its true spirit lies in a desire to teach, through practice, that we can never truly own what matters. Land, art, even, heartbreaking as it is to let go, a great work of art. The Winslows embody philanthropy. Phila, love. Anthro, man. Love of man, love of others.’ With that, he turned to Ev and raised his champagne. ‘We love you, Ev. Remember: we give not because we can, but because we must.’

CHAPTER THREE (#ue039d61b-4f81-558e-9d0a-3049c9a25ac5)

The Invitation (#ue039d61b-4f81-558e-9d0a-3049c9a25ac5)

ONE TOO MANY GLASSES of champagne, one too few canapés, and an hour later, the overheated room was swimming. I needed air, water, something, or I felt sure that my ankles – bowing under my body’s pressure upon the thin, pointed pair of heels Ev had insisted I borrow – would blow. ‘I’ll be back,’ I whispered as she nodded numbly at a trustee’s story about a failed trip to Cancún. I teetered down the long, glass-covered walkway leading into the gothic wing of the museum. In the bathroom, I splashed tepid water on my face. Only then did I remember I had makeup on. But it was too late; the wetness had already wreaked havoc – smeared lips, raccoon eyes. I pumped down paper towels and scrubbed at my face until I looked like I’d slept on a park bench, but not actively insane. It didn’t matter anyway – we were just going back to the dorm. Perhaps we’d order pizza.

I traipsed back up the hallway, a woman made new with the promise of pajamas and pepperoni. I was surprised to discover the great room already empty – save the violinist packing up her instrument and the waiters breaking down the naked banquet tables. Ev, the president, Birch, Tilde – all of them were gone.

‘Excuse me,’ I said to one of the waiters, ‘did you see where they went?’

His eyebrow ring caught in the light as he raised his brows in a ‘why should I care’ I recognized from my own nights working late at the cleaner’s. I went to the ladies’ room and peeked under the bathroom stalls. Tears began to sting my eyes, but I fought against them. Ridiculous. Ev was probably headed home to find me.

‘Goodness, dear,’ the curator tsked when she caught me in there. ‘The museum is closed.’ Had Ev been by my side, she wouldn’t have said it, and I wouldn’t have quickened my departure. I plucked my lonely coat from the metal rack in the foyer, and plunged out into the cold.

There, in sight of the double doors, were Ev and her mother, their backs to me. ‘Ev!’ I called. She did not turn my way. The wind, surely, had carried off my voice. So I approached, concentrating on my steps so as not to twist an ankle. ‘Ev,’ I said when I was close. ‘There you are. I was looking for you.’

Tilde snapped her head up at the sound of my voice as though I were a gnat.

‘Hey, Ev,’ I said gingerly. She did not answer. I reached out to touch her sleeve.

‘Not now,’ Ev hissed.

‘I thought we could—’

‘What part of not now don’t you understand?’ She turned toward me, rage on her face.

I knew well what it was to be dismissed. And I knew enough about Ev to know that she had spent much of her life dismissing. But it seemed so incongruous after the night we’d had – after I’d lied for her, and she’d finally acted like my friend – and so I remained frozen, watching Tilde steer Ev to the Lexus that Birch brought around.

She didn’t come home that night. Which was fine. Normal, even. I had lived for months with Ev with no expectations of her – not of friendship, or loyalty – but by the next day, her dismissal was gnawing at me, rubbing me raw, like the heels she’d lent me, making blisters I should have anticipated, and tried to prevent.

Despite pulling on her boots and letting them cup my arches; despite allowing myself to wish, with every step I took, that the previous night’s unpleasantness had been an anomaly, the day turned worse. Six classes, five papers, four midterm projects on the horizon, a thirty-pound backpack, the onset of a sore throat, pants sodden with snowmelt, and a hollow, growing loneliness inside. Trudging up our hall as evening fell, I could smell the telltale cigarette smoke whispering from under our door and remembered our RA’s offhand comment about how next time it happened she’d be in her rights to fine us fifty bucks, and I allowed myself to feel angry. Ev had returned, but so what? I had asthma. I couldn’t survive in a room filled with smoke – she was literally trying to suffocate me. My asthma medication’s one benefit – justification for the extra weight I carried – wouldn’t do me any good if I were dead.

I gritted my teeth and told myself to be strong, that I didn’t need the damn boots. I could just write to my father and ask for a pair (why hadn’t I done that already?). I didn’t need a Degas-bestowing supermodel snob lying around my room, reminding me what a nothing I was. I gripped the doorknob and told myself to say it how Ev would say it, formulated ‘Fuck, Ev, could you smoke somewhere else?’ (I would make my voice nonchalant, as though my objection was philosophical and not an expression of poverty), and barged in.

She usually smoked atop her desk beside the window, cigarette perched in the corner of her mouth, or cross-legged on the top bunk, ashing into an empty soda bottle. But this time, she wasn’t there. As I dropped my bag, I imagined with delighted gloom that she’d left a cigarette smoldering on the bedclothes before heading out to some glamorous destination – the Russian Tea Room, a private rooftop in Tribeca. The whole dorm was doomed to go up in flames, and I would go down with it. She would be forced to remember me forever.

And then I heard it: a sniffle. I squinted at the top bunk. The comforter quivered.

‘Ev?’

The sound of soft crying.

I approached. I was still in my drenched jeans, but this was electrifying.

I stood at that awkward angle, neck craned up. She was really under there. I wondered what to do as her voice began to break into a full, throaty sob. ‘Are you okay?’ I asked.

I didn’t expect her to answer. And I certainly didn’t mean to put my hand on her back. Had I been thinking clearly, I never would have dared – my anger was too proud; the gesture, too intimate. But my little touch elicited unexpected results. First, it made her cry harder. Then it made her turn in the bed, so that her face and mine were much closer than they’d ever been and I could see every millimeter of her flooding, Tiffany-blue eyes; her stained, rosy cheeks; her greasy blond hair, limp for the first time since I’d known her. Her mouth faltered, and I couldn’t help but put my hand to her hot temple. She looked so much more human this close up.

‘What happened?’ I asked, when she’d finally calmed.

For a moment it seemed as if she might start sobbing again. Instead, she fished out another cigarette and lit it. ‘My cousin,’ she said, as if that told the whole thing.

‘What’s your cousin’s name?’ I didn’t think I could stand not to know what was breaking Ev’s heart.

‘Jackson,’ she whispered, the corners of her mouth turning down. ‘He’s a soldier. Was,’ she corrected herself, and her tears spilled all over again.

‘He was killed?’

She shook her head. ‘He came back last summer. I mean, he was acting a little strange and everything, but I didn’t think …’ And then she cried. She cried so hard that I slipped off my parka and jeans and got in bed beside her and held her quaking body.

‘He shot himself. In the mouth. Last week,’ she said finally, what seemed like hours later, when we were lying beside each other under her four-ply red cashmere throw, staring up at the cracked ceiling as if this was what we did all the time. It was a relief to finally hear what had happened; I had started to wonder if this cousin hadn’t walked into a post office and shot everyone up.

‘Last week?’ I asked.

She turned to me, touching our foreheads. ‘Mum didn’t tell me until last night. After the reception.’ Her nose and eyes began to pinken in anticipation of another round of tears. ‘She didn’t want me to get upset and “ruin things.”’

‘Oh, Ev,’ I sympathized, filling with forgiveness. That was why she had snapped at me after the party – she was grief-stricken.

‘What was Jackson like?’ I pushed, and she began to weep again. It was so strange and lovely to be lying next to her, feeling her flaxen hair against my cheek, watching the great globes of sorrow trail down her smooth face. I didn’t want it to end. I knew that to stop speaking would be to lose her again.

‘He was a good guy, you know? Like, last summer? One of his mom’s dogs, Flip, was running on the gravel road and this asshole repair guy came around the curve at, like, fifty miles an hour and hit the dog and it made this awful sound’ – she shuddered – ‘and Jackson just walked right over there and picked Flip up in his arms – I mean, everyone else was screaming and crying, it, like, happened in front of all the little kids – and he carried her over to the grass and rubbed her ears.’ She closed her eyes again. ‘And afterward, he put a blanket over her.’

I looked at the picture of the gathered Winslows above my desk, although it was as silly an enterprise as opening the menu of a diner you’ve been going to your whole life; I knew every blond head, every slim calf, as though her family was my own. ‘This was at your summer place, right?’

She pronounced the name as if for the first time. ‘Winloch.’

I could feel her eyes examining the side of my face. What she said next, she said carefully. Even though my heart skipped a beat, I measured my expectations, telling myself that was the last I’d hear of it:

‘You should come.’

June (#ulink_712a0322-9b37-542a-96f6-f01714ae2584)

CHAPTER FOUR (#ulink_fc0bbc7c-be8e-5d56-867c-410e23b450b5)

The Call (#ulink_fc0bbc7c-be8e-5d56-867c-410e23b450b5)

DO THEY KNOW WE’RE coming?’ I asked as Ev handed me the rest of the Kit Kat bar I’d bought in the dining car. The train had long since whistled twice and headed farther north, leaving us with empty track and each other.

‘Naturally.’ Ev sniffed with a trace of doubt as she settled, again, on top of her suitcase under the overhang of the stationmaster’s office. She regarded my orange copy of Paradise Lost disdainfully, then checked her cell phone for the twentieth time, cursing the lack of service. ‘And now we’ll only have six days before the inspection.’

‘Inspection?’

‘Of the cottage.’

‘Who’s inspecting it?’

I could tell from the way she blinked straight ahead that my questions were an annoyance. ‘Daddy, of course.’

I tried to make my voice as benign as possible. ‘You sound concerned.’

‘Well of course I’m concerned,’ she said with a pout, ‘because if we don’t get that little hovel shipshape in less than a week, I won’t inherit it. And then you’ll go home and I’ll have to live under the same roof as my mother.’

Her mouth was set to snarl at whatever I said next, so instead of voicing all the questions flooding my mind – ‘You mean I might still have to go home? You mean you, of all people, have to clean your own house?’ – I looked across the tracks to a tangle of chickadees leapfrogging from one branch to the next, and sucked in the fresh northern air.

An invitation marks the beginning of something, but it’s more of a gesture than an actual beginning. It’s as if a door swings open and sits there gaping, right in front of you, but you don’t get to walk through it yet. I know this now, but back then, I thought that everything had begun, and, by everything, I mean the friendship that quickly burned hot between me and Ev, catching fire the night she told me of Jackson’s death and blazing through the spring, as Ev taught me how to dance, who to talk to, and what to wear, while I tutored her in chemistry and convinced her that, if she’d only apply herself, she’d stop getting Ds. ‘She’s the brainiac,’ she’d started to brag warmly, and I liked the statement mostly because it meant she saw us as a pair, strolling across the quad arm in arm, drinking vodka tonics at off-campus parties, blowing off her druggie friends for a Bogart movie marathon. From the vantage point of June, I could see my belonging sprouting from that day in February, when Ev had uttered those three dulcet words: ‘You should come.’

Over the course of the spring, in each note scribbled on the back of a discarded dry-cleaning receipt, in each secretive call to my dorm room, my mother had intimated I should be wary of life’s newfound generosity. As usual, I’d found her warnings (as I did nearly everything that flowed from her) Depressing, Insulting, and Predictable – in her way, she assumed Ev was just using me (‘For what?’ I asked her incredulously. ‘What on earth could someone like Ev possibly use me for?’). But I also assumed, once my father reluctantly agreed to the summer’s arrangement, that she would lay off, if only because, by mid-May, Ev had peeled her Winloch photograph off the wall, I’d put the bulk of my belongings into a wooden crate in the dorm’s fifth-floor attic, and my summer plans – as far as I saw them – were set in stone.

So the particular call that rang through Ev’s Upper East Side apartment, the one that came the June night before Ev and I were to get on that northbound train, was surprising. Ev and I were chopsticking Thai out of take-out containers, sprawled across the antique four-poster bed in her bedroom, where I’d been sleeping for two blissful weeks, the insulated windowpanes and mauve curtains blocking out any inconvenient sound blasting up from Seventy-Third Street (a blessed contrast to Aunt Jeanne’s wretched spinster cave, where I’d spent the last two weeks of May, counting down the days to Manhattan). My suitcase lay splayed at my feet. The Oriental rug was scattered with sturdy bags: Prada, Burberry, Chanel. We’d already put in our half-hour jog on side-by-side treadmills in her mother’s suite and were discussing which movie we’d watch in the screening room. Tonight, especially, we were worn out from rushing to the Met before it closed so Ev could show me her family’s donations, as she’d promised her father she would. I’d stood in front of two swarthily paired Gauguins, and all I could think to say was ‘But I thought you had three brothers.’

Ev had laughed and wagged her finger. ‘You’re right, but the third’s an asshole who auctioned his off and donated the proceeds to Amnesty International. Mum and Daddy nearly threw him off the roof deck.’ Said roof deck lay atop the building’s eighth floor, which was taken up entirely by the Winslows’ four-thousand-square-foot apartment. Even though I was naïve about the Winslows’ money, I already understood that what summed up their status resided not in their mahogany furnishings or priceless art but, rather, in the Central Park vistas offered from nearly every one of the apartment’s windows: a pastoral view in the middle of an overpopulated city, something seemingly impossible and yet effortlessly achieved.

I could only imagine how luxurious their summer estate would be.

At the phone’s second bleating, Ev answered in a voice like polished glass, ‘Winslow residence,’ looked confused for an instant, then regained her composure. ‘Mrs Dagmar,’ she enthused in her voice reserved for adults. ‘How wonderful to hear from you.’ She held the phone to me, then flopped onto the bed, burying herself in the latest Vanity Fair.

‘Mom?’ I lifted the receiver to my ear.

‘Honey-bell.’

Instantly, I could smell my mother’s pistachio breath, but any longing was pushed down by the memory of how these phone calls usually ended.

‘Your father says tomorrow’s the big day.’

‘Yup.’

‘Honey-bell,’ she repeated. ‘Your father’s set the whole thing up with Mr Winslow, and I don’t need to remind you that they’re being very generous.’

‘Yup,’ I replied, feeling myself bristle. Who knew what Birch had finally said to get my reluctant, sullen father to agree to let me miss three months of punishing labor, but whatever it was, it had worked, and thank god for it. Still, I found it borderline insulting to suggest my father had had anything to do with ‘setting the whole thing up’ when he’d barely tolerated it, and was reminded of how my mother always sided with him, even when (especially when) her face held the pink imprint of his hand. My eyes scanned the intricate pattern of Ev’s rug.

‘Do you have a hostess gift? Candles maybe? Soap?’

‘Mom.’

Ev glanced up at the sharpness in my voice. She smiled and shook her head before drifting back into the magazine.

‘Mr Winslow told your father they don’t have service up there.’

‘Service?’

‘You know, cell phone, Internet.’ My mother sounded flustered. ‘It’s one of the family rules.’

‘Okay,’ I said. ‘Look, I’ve got to—’

‘So we’ll write then.’

‘Great. Bye, Mom.’

‘Wait.’ Her voice became bold. ‘There’s something else I have to tell you.’

I absentmindedly eyed a long, thick bolt on the inside of Ev’s bedroom door. In the two weeks I’d slept in that room, I’d never given it much thought, but now, examining how sturdy it looked, I was struck with wondering: why on earth would a girl like Ev want to lock out any part of her perfect life? ‘Yes?’

‘It’s not too late.’

‘For what?’

‘To change your mind. We’d love to have you home. You know that, don’t you?’

I almost burst out laughing. But then I thought of her burned meat loaf, sitting, lonely, in the middle of the table, with just my father to share it. Microwaved green beans, limp, in their brown juices. Rum and Cokes. No point in rubbing my freedom in. ‘I need to go.’

‘Just one more thing.’

It was all I could do not to slam the receiver down. I’d been perfectly warm, hadn’t I? And listened plenty? How could I ever make her understand that this very conversation with her, laden with everything I was trying to escape, made Winloch, with no cell phones or Internet, sound like heaven?

I could feel her trying to figure out how to put it, her exhalations flushing into the receiver as she formulated the words. ‘Be sweet,’ she said finally.

‘Sweet?’ I felt a lump rise in my throat. I turned from Ev.

‘Be yourself, I mean. You’re so sweet, Honey-bell. That’s what Mr Winslow told your dad. You’re a “gem,” he said. And, well’ – she paused, and, despite myself, I hung on her words – ‘I just want you to know I think so too.’

How could she still make me hate myself so readily? Remind me that I could never undo what I had done? The lump in my throat threatened to well into something more. ‘I’ve got to go.’ I hung up before she had the chance to protest.

But I hadn’t caught my tears in time. They flowed, hot and angry, down my cheeks against my will.

‘Mothers are such lunatic bitches,’ Ev quipped after a moment.

I kept my back to her and tried to gather my strength.

‘Are you crying?’ She sounded shocked.

I shook my head, but she could see that was exactly what I was doing.

‘You poor kitten,’ she soothed, her voice turning velvety, and, before I knew it, she was wrapping me in a tight embrace. ‘It’ll be all right. Whatever she said – it doesn’t matter.’

I had never let Ev see me walloped, had felt sure that, if she did, she would be fruitless in her comforting. But she held me firmly and uttered calm and soothing words until my tears weren’t so urgent.

‘She’s just – she’s not – she’s everything I’m afraid of becoming,’ I said finally, trying to explain something I’d never said out loud.

‘And that may be the only way that your mother and my mother are exactly the same.’ Ev laughed, offering me a tissue, and then a sweater from a bag on the floor, azure and soft, adding, ‘Put it on, you pretty thing. Cashmere makes everything better.’

Now, I looked across the Plattsburgh train depot and swelled with indulgent love at Ev’s grumpy scowl.

‘Be sweet,’ my mother had said.

A command.

A warning.

A promise.

I was good at being sweet. I’d spent years cloaked in gentleness, in wide-eyed innocence, and, to tell the truth, it was often less exhausting than the alternative. I could even see now, looking back on how Ev and I had gained our friendship, that sweetness had been the seed of it – if I wasn’t good, why on earth would I have dared to touch Ev’s sobbing self?

There was no sign of anyone coming to meet us. Ev’s mood had settled into inertia. It would be dark soon. So I headed south along the tracks, in the direction of a periodic clanging I’d heard for the past half hour.

‘Where are you going?’ Ev called after me.

I returned with a greasy trainman, toothless and gruff. He let us into the stationmaster’s office before trudging away.

‘There’s a phone in here,’ I offered.

‘The Dining Hall is the only place at Winloch there’s a phone, and no one will be there at this hour,’ she snarled, but she dialed the number anyway. It rang and rang, and, just as even I was beginning to lose hope, I spotted, through the dusty, cobwebbed window, a red Ford pickup rolling up, complete with waggling yellow Lab in the truck bed.

‘Evie!’ I heard the man’s voice before I saw him. It was young, enthusiastic. As we stepped from the office – ‘Evie!’ – he rounded the corner, opening his tanned arms wide. ‘I’m glad you made it!’

‘I’m glad you made it,’ she huffed, brushing past him. He was tall and dark, his coloring Ev’s opposite, and he looked to be only a few years older. Still, there was something manly about him, as though he’d lived more years than both of us combined.

‘You her friend?’ he asked, fiddling with his cap, grinning after her as she wrestled her suitcase in the direction of the parking lot.

I shoved Paradise Lost into my weatherworn canvas bag. ‘Mabel.’

He extended his rough, warm hand. ‘John.’ I assumed he was her brother.

CHAPTER FIVE (#ulink_017634fb-1d16-5f1b-b64e-71200fbbf87d)

The Journey (#ulink_017634fb-1d16-5f1b-b64e-71200fbbf87d)

JOHN’S FOUR-DOOR PICKUP WAS old, but it was clear he took great pride in it, second only to his yellow Lab, who barked triumphantly from the flatbed at the sight of us. Ev struggled to toss in her suitcase until John lifted it in one hand – mine was in his other. He placed them down beside the giddy canine, who was, by then, doing her best to lick Ev’s ear. ‘Down, Abby,’ John commanded as he strapped our luggage flat. The dog obeyed.

Ev let herself into the front seat, a scowl tightly knit upon her brow. ‘It stinks in here.’ She pointedly rolled down her window, but it wasn’t lost on me that she had smiled under Abby’s lapping attention.

In the backseat, I checked the dog over my shoulder. ‘She’s okay?’

John turned on the ignition. ‘She’d whine if we brought her in.’ As the engine growled to life, his hand hesitated over the radio dial, then dropped back onto the steering wheel. I would have liked music, but Ev put up an arctic front.

We drove ten miles in silence, the country road canopied in electric green. I pressed my head against the glass to watch the new maple leaves curling in the breeze. Every few turns offered a tempting glimpse of Lake Champlain’s choppy waters. I turned over in my mind which brother John might be. He seemed less the type to donate to the Met, so I decided he was the ‘asshole’ to whom Ev had referred – she clearly had a strong aversion to everything of his, save Abby.

‘Aren’t you going to apologize?’ Ev asked John when we pulled into line at the ferry that would take us from New York State to Vermont. I hadn’t known there was going to be a boat ride, and I was doing my best to hide my excitement as the muddy smell of the lake wafted up to us. Being on open water seemed just the thing.

John laughed. ‘For what?’

‘We were at that station for two hours.’

‘And it took two hours to get there,’ he countered warmly, turning on Elvis. I had only seen men capitulate when faced with Ev’s indignation.

Once onboard, I clambered up to the passenger deck. It was a clear evening. The western sky began to orange, and the clouds turned brilliant as fire.

I was glad to have left John and Ev in the pickup, figuring they could use some privacy to iron out their sibling rivalry. I opened Paradise Lost. My conversation with the college president at Ev’s birthday reception had secured my spot in the upper-level Milton course, and I was planning to have the book ‘under my belt’ by the fall, when I could read it with a professor who could tell me what it meant. It might as well have been written in Greek; it seemed to be all italics and run-on sentences, but I knew it was Important, and I loved the idea of reading a book about something as profound as the struggle between Good and Evil. I also felt an affinity for Milton’s daughter, forced to take dictation for her blind, brilliant father. It was my girlhood, but glamorous, trading sumptuous words for other people’s dirty clothing.

But just as I began the first line – ‘Of Man’s First Disobedience, and the Fruit / Of that Forbidden Tree’ – I heard a bark and lifted my eyes to see John and Abby climbing onto the deck. Beside them, a sign read NO DOGS, but a man who worked the ferry patted Abby on the head and shook John’s hand before moving belowdecks. John strode toward me, into the gusting air, one hand on Abby’s collar.

‘Where you from?’ he asked over the roaring wind.

‘Oregon.’ A seagull streamed by. My hair, whipping, stung the sides of my face. ‘But I know Ev from school.’ We looked out over the water together. The lake was oceanic. I released my finger from the book, watching the pages flutter violently before it closed on its own.

‘Is Ev okay?’ I asked.

He let Abby go. She settled at his feet.

‘Is she mad because of the inspection?’ I fished.

‘Inspection?’

‘The inspection of her cottage. In six days.’

John opened his mouth to say something, then closed it.

‘What?’ I asked.

‘I’d steer clear of all that family stuff if I were you,’ he said, after a long moment. ‘It’ll make it easier to enjoy your vacation.’

I’d never been on a vacation before. The word sounded like an insult coming from his mouth.

‘You don’t seem like the other girls Ev’s brought,’ he added.

‘What does that mean?’

His eyes followed the seagull. ‘Less luggage.’

That was when Ev appeared, bearing ice cream sandwiches. Her version, I suppose, of an apology.

Back on land, finally close to Winloch, worry about the inspection slipped through my fingers. The roadside hot dogs were flabby, the mosquitoes ravenous, and Ev was still grumpy, but we were in Vermont, together, on an open road winding through farmland. Dusk shrouded the world.

We filled up at the only gas station I’d seen for miles, and a knackered Abby joined me in the backseat, promptly laying her heavy head upon my knee and curling into sleep. We drove on, past a shuttered horse farm, signs for a vineyard, and an abandoned passenger train car, and finally, as dusk gave way to night, onto a two-lane highway that streamed south under a starry sky. At one point, the road broke out into a causeway that looked like something out of the Florida Keys – or at least pictures I had seen of the keys – and the moon burst forth from behind the clouds. It lit a yellow ribbon on the water and cast the dark outlines of the distant Adirondacks against a purple-black sky.

‘How’s your mother?’ Ev asked. At first I thought she was speaking to me, but then, she knew how my mother was; she’d comforted me about her only the night before.

In the gap made by my racing mind, John spoke. ‘Like always.’

Oh wait, I realized, he’s not Ev’s brother.

I wanted them to go on. But Ev didn’t ask any more questions, and we crossed the causeway in silence.

On the other side of the glistening water, we were once again plunged into darkness. A sudden forest swallowed what became a gravel road. Birch trunks glowed ghostly in the moonlight. John’s headlights gave us glimpses of barns and farmhouses. He took each turn with the reckless speed of someone who has driven it a thousand times. Ev unrolled her window again to let the sweet night in, and we were embraced by the soft chirping of crickets, their pulse growing louder as we drove into a vast meadow. The moon greeted us again, a milky lantern.

We slowed after a particularly skidding turn – I could feel the rocks kicking out from under our tires. ‘We’re here,’ Ev sang. Outside stood dense forest. Nailed to one of the trunks was a small sign with hand-painted letters spelling out WINLOCH and PRIVATE PROPERTY. Our headlights pointed onto a precarious-looking road hung with warnings: NO TRESPASSING! NO HUNTING – VIOLATORS WILL BE PROSECUTED! NO DUMPING. This bore no resemblance to the grand estate which Ev had described. The skittering sound of the leaves brought to mind a movie I’d once seen about vampires. I felt a prickling up my spine.

It occurred to me then that my mother was probably right: Ev had brought me all the way here only to leave me on the side of the road, an elaborate trick not unlike the one Sarah Templeton had played on me in sixth grade, asking me to her birthday party only to disinvite me – with a roomful of classmates looking on – the moment I materialized on her doorstep, because I was ‘too fat to fit in any of the roller coaster seats.’ The doubt my mother had been planting began to spread through me – I was a fool to think Ev had actually brought me to her family’s estate for a summer of fun.

But Ev laughed dismissively, as though she could read my thoughts. ‘Thank god you’re here,’ she said, and the warmth of her cheer, and the softness of the azure cashmere, brought me back to my senses.

John flipped on the radio again. Country. We plunged into the forest as a man mourned his breaking heart.

We braked once, abruptly. A raccoon blocked our way, his eyes glowing in the glare of our headlights as he waited, front paw lifted, for us to hit him. But John flipped the lights and radio off, and we sat with the engine purring low as the animal’s strange, uneven body scurried into the scrub lining the road.

We cut our way past a smattering of unlit cottages, then tennis courts and a great, grand building glowing white in the moonlight. We turned right onto a side road – although it could hardly have been called more than a path – which we stayed on for another quarter mile before sighting a small house set at the dead end.

‘No dogs allowed, but I’ll make an exception for Abby,’ Ev offered as John pulled up in front of the cottage.

‘Don’t do her any favors.’

‘It’s not a favor,’ she replied, eyes skimming John.

He took Abby toward the woods to piddle. The night came rushing in: the rhythmic cricket clamor, the lapping of water I couldn’t see. The moon was behind a cloud. Beyond us, I could sense an expanse which I took to be the lake.

‘What do we have to do before the inspection?’ I asked Ev quietly.

‘Make it livable. Now we only have six days until my parents arrive, and I don’t even know what state it’s in.’

‘What if we can’t do it that fast?’ I asked.

Ev cocked her head to the side. ‘Are you worrying again, Miss Mabel?’ She looked back at me. ‘All we have to do is clean it up. Make it good as new.’

The moon reemerged. I examined the old house before us – an indecipherable sign nailed to it began with the letter B. The building looked rickety and weatherworn in the moonlight. I had a feeling six days wasn’t going to cut it. ‘What happens if we can’t?’

‘Then I move in with my witch of a mother and you spend the summer in Oregon.’

My lungs filled with the chemical memory of perc. My feet began to ache from a phantom day of standing behind the counter. I couldn’t go home – I couldn’t. How could I explain my desperation to her? But then I stepped into the night, and there Ev was, in the flesh, smelling of tea roses. She threw her arms wide to envelop me.

‘Welcome home,’ she murmured. ‘Welcome to Bittersweet.’

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/miranda-beverly-whittemore/bittersweet/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Miranda Beverly-Whittemore

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: One perfect family.Too many perfect lies.Small-town girl Mabel Dagmar is out of her depth. At her elite East Coast college, unversed in the nuances of casual privilege, she is ignored, especially by her dormmate, Ev Winslow, whose pedigree disguises a chequered past. Then out of nowhere Ev softens and Mabel finds herself entering the world of the elite, with an invitation to the Winslows’ private estate, Winloch, that very summer.Days spent swimming in watery coves evaporate into nights at glamorous cocktail parties. And as the formality melts away with one Winslow brother in particular, Mabel is left to think that her summer has all but become a golden dream.But when Mabel looks a little closer at the Winslows, probing beneath their glossy exterior, what she uncovers in their past is almost as shocking as what she finds out about their present. Beneath the beauty is a rotten core.And not everyone is quite as they seem…