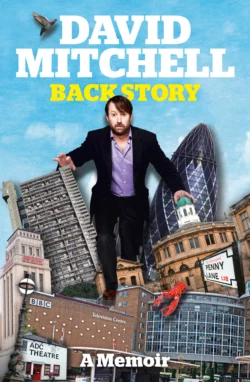

David Mitchell: Back Story

David Mitchell

David Mitchell, who you may know for his inappropriate anger on every TV panel show except Never Mind the Buzzcocks, his look of permanent discomfort on C4 sex comedy Peep Show, his online commenter-baiting in The Observer or just for wearing a stick-on moustache in That Mitchell and Webb Look, has written a book about his life.As well as giving a specific account of every single time he's scored some smack, this disgusting memoir also details:• the singular, pitbull-infested charm of the FRP (‘Flat Roofed Pub’)• the curious French habit of injecting everyone in the arse rather than the arm• why, by the time he got to Cambridge, he really, really needed a drink• the pain of being denied a childhood birthday party at McDonalds• the satisfaction of writing jokes about suicide• how doing quite a lot of walking around London helps with his sciatica• trying to pretend he isn’t a total **** at Robert Webb’s wedding• that he has fallen in love at LOT, but rarely done anything about it• why it would be worse to bump into Michael Palin than Hitler on holiday• that he’s not David Mitchell the novelist. Despite what David Miliband might think

For VC (M)

Contents

Cover (#ud81b6a59-cce5-5440-b654-c5a66e3171c3)

Title Page (#u4d783aa3-8f14-511d-a50c-149aea58324f)

Dedication (#ud07ee4c3-b92b-5c65-b1c1-ddbb7227320b)

Introduction

1 The Fawlty Towers Years

2 Inventing Fleet Street

3 Light-houses, My Boy!

4 Summoning Servants

5 The Pianist and the Fisherman

6 Death of a Monster

7 Civis Britannicus Sum

8 The Mystery of the Unexplained Pole

9 Beatings and Crisps

10 The Smell of the Crowd

11 Cross-Dressing, Cards and Cocaine

12 Presidents of the Galaxy

13 Badges

14 Play It Nice and Cool, Son

15 Teenage Thrills: First Love, and the Rotary Club Public Speaking Competition

16 Where Did You Get That Hat?

17 I Am Not a Cider Drinker

18 Enthusiasm in Basements

19 God Is Love

20 The Cause of and Answer to All of Life’s Problems

21 Attention

22 Mitchell and Webb

23 We Said We Wouldn’t Look Back

24 The Lager’s Just Run Out

25 Real Comic Talent

26 Going Fishing

27 Causes of Celebration

28 The Magician

29 Are You Sitting Down?

30 Peep Show

31 Being Myself

32 Lovely Spam, Wonderful Spam

33 The Work–Work Balance

34 The End of the Beginning

35 Centred

Picture Section

Copyright

About the Publisher

Introduction (#u04b57298-596e-5838-a99b-cfab9a8c8d06)

This is one of those misery memoirs. And it’s one of those celebrity memoirs. It’s also a very personal journey, a manual for urban ramblers and a weight-loss guide. Surely it’ll sell?

I realise the whole ‘Let me tell you about my pain’ thing is a classic envy-avoidance technique. What it’s saying is: if you envy me my interesting job, my relative affluence and moderate fame, then don’t. Because I struggle daily with a dark and terrible problem. With some it’s drugs, abuse, depression, the loss of loved ones, the terrible illness of a child – well, you can’t have it all, I suppose, and so I’ve made do with a bad back.

What do you reckon to that then, enviers!? Eh? You want to swap!? Ow, my back! You want to swap places!? Well go ahead, if you like terrible pain and misery, hardly assuaged at all by getting to be on TV! Eek, my poor spine! You want to take my place in the horror dome!? Ow, it’s creaking and spasming! Well, make my day! By which I mean life!

I’m assuming here that my life is enviable enough to require this mitigating strategy. Well, I admit it – I think it is. Aside from being born into the free and affluent West and never having had to worry about food, shelter and warmth, I do basically think I’m a jammy sod. I’m not saying there aren’t things that worry and upset me a lot, but I reckon everyone gets that. And I make a very good living doing something I love, a state of affairs that tends to be envied by those who don’t share it. Of course there will be loads of people who don’t envy me at all. I probably envy them. I expect they’ll have all yachts and kids and stuff.

What this book isn’t is one of those novels by David Mitchell. You know, David Mitchell the novelist. I’m sure he would never allow a sentence with ‘isn’t is’ in it like that. Everyone says he’s a very good novelist but I’ve never checked, partly because I resent him for sharing my name without asking and partly because I do a lot of my novel reading on the Tube and it would feel weird to be reading a book with my name on it in public. If one of the people who conflate me and the novelist saw that, they’d think I was sitting there reading my own book. ‘He might as well spend the whole journey admiring his own reflection in a hand mirror,’ such a person might think.

David Miliband is such a person (although he might take a less than averagely dim view of narcissism). I was once in a London park, on a crisp winter afternoon, feeding some bread to the ducks with a girl, when David Miliband wandered up with his kids. He stood there, a couple of yards behind us, for what felt like minutes. He was playing with his children in the park at the weekend, like a perfectly normal husband and father, who is being portrayed by a power-crazed Martian.

The woman I was with urgently wanted us to say hello. She was all interested, I don’t know why. I couldn’t see the point in bothering him. I thought it would be embarrassing. I was right.

‘Oh, you’re David Mitchell,’ said David Miliband, adding politely to my companion: ‘I love his books.’

This was nice of him. But it was a complicated moment. He can’t have known that there were a comedian and a novelist both called David Mitchell and mistaken me for the other one, because he recognised my face. He must have just assumed we were the same person.

Or he knew perfectly well I was only the comedian, and had particularly enjoyed This Mitchell and Webb Book, my most recent publication at the time. In fact, my only publication at the time. But he’d said ‘books’. Perhaps he was looking ahead? Yes, that must be it. He was so confident he’d enjoy my future volumes, he was already able to say he loves them. Thinking about it, I’d have been quite justified in putting that quote on the cover.

But I’m not the novelist, I’m the one who’s a bit known from TV. And of course there are millions of other David Mitchells who are neither. Was it the pain of my slightly problem back that gave me the need, the will and the focus to become one of the David Mitchells that potential Prime Ministers mistake for one of the others? Was it because I was maddened yet driven by a constant sciatic throb that I was able to conceive of sketches and characters that were marginally more amusing than those of people who didn’t end up on TV? Is it the desire to get up and stretch that inspires my trademark panel show ‘rants’? Would I happily exchange all the success for a less problematic spine? Or is my aching back so completely a part of me that, metaphorically bitter and literally twisted though it makes me, I wouldn’t change it if I could? Do I, as Captain Kirk said in Star Trek V, ‘need my pain’?

You will find the answers to all those questions in this book. Indeed in this section. On this very page. In this paragraph. In fact, in two words’ time. It is ‘No.’ To all of them.

I know what you’re thinking. Why didn’t BBC Four snap this up? It would make a cracking documentary. Good point. It would be gold dust. Me moaning about my back, pottering around stiffly, interviewing other people about their niggles, talking to specialists, shaking my head with concern as I’m told about the annual man-hours lost nationally, before suddenly putting an anguished hand to a cricked neck. They could even have clips of The Simpsons, for God’s sake. That episode where Homer goes to the chiropractor.

But no, when it comes to celebrities moaning about their problems, they only want to hear about depression and madness. The liberal media have a tremendous bias in favour of disorders of the nervous system’s cerebral centre rather than its provincial offshoots. It’s London-centricity made anatomical and there was no shifting any TV commissioner to the Salford that is my spine.

Yet, let me tell you, back pain is a fascinating topic – as long as it’s your own. It may not be fun to think about, largely because it happens in the context of nagging back pain – it’s like trying to solve an engrossing country house murder while gradually being murdered yourself – but it’s never boring.

That was my situation in 2007. It was really worrying me. I tried everything. By which I mean, I tried some things. You can’t try everything. The world is full of evangelists – people who are convinced the answer lies in acupuncture, chiropractic, osteopathy, physiotherapy, cod liver oil or changing the pocket you keep your wallet in. I tried some remedies, and felt guilty that I wasn’t trying more, but also tired because the condition stopped me sleeping properly. Even Poirot’s little grey cells might have misfired if he was being occasionally bonked on the head by an invisible candlestick as he tried to address the suspects.

I took note of the things that I wanted to hear (such as ‘you can fix it by sitting on a ball’) and not the things I didn’t (such as ‘you might need a major operation’) – like you do when you’re infatuated with someone and can’t yet bring yourself to draw the dispiriting conclusion that they don’t fancy you. That would mean you’d have to start the incredibly unpleasant process of getting over them. In those circumstances – and I feel this gives an insight into the mentality of the stalker – you treasure any sign of affection or kindness and build great castles of reason around them in your mind: how could they possibly have said that, smiled then, noticed this, if they didn’t on some level return your feelings? Meanwhile you ignore the overwhelming body of evidence of their indifference and the fact that they’re often really quite pleasant to a wide range of people without that meaning they’d ever be willing to have sex with them. (More of this later.)

It’s a sign of how deep my despair became, and yet how stubbornly I avoided dealing with the subject via official medical channels because of my weird fear of doctors and hospitals, that I started sitting on a ball – and indeed that I still sit on a ball, that I’m sitting on a ball as I write this. A giant inflatable yoga ball. Apologies if that’s shattered your image of me lounging in a Jacuzzi smoking a cigar while dictating these words to an impatient and topless Hungarian supermodel. But, no, I’m perched alone on a preposterous piece of back-strengthening furniture in my bedroom in Kilburn surrounded by dusty piles of books and old souvenirs from the Cambridge Footlights.

You have no idea how greatly sitting on a ball offends me aesthetically and challenges my sense of who I am. Or maybe you do. After all, you have bought a book written by me – you’re probably aware of my tweedy image. You’ve probably guessed that all things ‘new age’ tend to make me raise a sceptical eyebrow. And a sceptical fist, which I bang sceptically on the table while wryly starting a sceptical chant of ‘Fuck off! Fuck off! Fuck off!’ before starting sceptically to throw stuff and scream: ‘You can shove your trendy scientifically unsubstantiated bullshit up your uncynical anuses!’

To me, sitting on a ball feels a bit wind chimes. It’s got a touch of the homeopathic about it. In homeopathic terms: a massive overdose. It smacks of wheat intolerance. Which, to me, smacks of intolerance. And I’m very intolerant of it.

The other major lifestyle change I adopted was walking. That was the only thing about which there appeared to be any consensus among the people offering me advice: that walking, even if it hurt, always helped. Resting, oddly, did not. Resting oddly certainly didn’t. (Take that, Lynne Truss!) Walking was something I could do. This was so much more approachable as a solution than either the conventional medicine route (doctors, painkillers, scans, scalpels, unconsciousness) or any of the trendier alternatives, a lot of which – yoga and pilates, for example – seemed to involve going to classes.

I don’t think men can really go to yoga classes, can they? I mean, it would be weird. All the women would just think you were there in the hope of a covert ogle or to hit on them afterwards. This is what I had always suspected until I was talking to a female friend about yoga. It was a group conversation in the pub. She was extolling the virtues of her yoga classes and saying how everyone should go until one of the men present asked: ‘But wouldn’t it be weird for a man?’

She seemed surprised. She thought for a moment. Then she said: ‘Yes, you’re right. It would be really weird. I was just recommending it because I go and I like it. But, no, of course if a man turned up, we’d all assume he was a pervert.’

But you seldom get called a pervert just for walking, unless you’re naked and circling a primary school. So I started to walk, first for half an hour and then for an hour every day, and let me tell you it has cured my back. I get the occasional niggle, but then, who doesn’t? But it doesn’t feel fragile any more and I can bend down without having to take a few minutes to plan.

That’s the main advantage. There’s a secret other one, which is that I’ve lost about two stone in weight. But that’s incidental. I refuse to let myself be pleased about it. Or rather I’m in total denial of how pleased I am about it. I don’t want to think of myself as that vain – or to admit that I’d even noticed the lamentable chubbiness that encroached over successive Peep Show series. If it made me a bit trimmer, that’s a happy accident. Not even that, an irrelevant accident. I’m not the sort of person to care about that sort of thing: I don’t go to gyms or diet. I fear that calorie counting, if I ever tried it, would be a short hop from powdering my wig, dousing myself in scent and speaking French to passers-by. I just take a daily constitutional. In a British sort of way.

And it turns out that I like walking. I find it relaxing – differently from, if not necessarily more than, watching television. It gives me some time to think, without the self-consciousness of having set aside some time to think. I find I’m more aware of the weather and the seasons and I have a much greater knowledge of the city I live in. If ignorance of one-way systems and not having a driving licence weren’t a handicap, I’d be able to qualify as a taxi driver.

In this book, I’ll take you on one of my walks – and I promise I won’t go on about my back. It’s a walk through my life, really, but I’ll try to point out some of the notable London landmarks along the way so you can use it as a travel guide if you prefer. But it’s basically a weight-loss manual.

- 1 - (#u04b57298-596e-5838-a99b-cfab9a8c8d06)

The Fawlty Towers Years (#u04b57298-596e-5838-a99b-cfab9a8c8d06)

Anyone watching me lock my front door would think that I was trying to break in: frantically yanking the handle up and down, pulling it hard towards me and then pushing against the frame with a firmness that’s just short of a shoulder barge. Then running round to the kitchen window and furtively peering in. In fact I’m checking that the door’s properly locked and then that the gas is off. This is the wrong way round but I’m relatively new to having gas and so the neuroticism about it kicks in marginally later than my door doubts, which date from having a locker at school.

I never had anything of any value in my locker – not so much as a Twix. But the fact that it was lockable meant it should be locked, meant that I had to remember to lock it, meant that I had to check that it was locked, meant that I had to remember if I’d checked that it was locked.

That was the advent of my school-leaving dance (by which I mean the odd routine I put myself through every day before going home, not a sort of prom; my school didn’t have a prom, it was in Britain – in fact it had a ball; I didn’t go). The steps were: locking my locker, checking it absent-mindedly, walking out of the room, pausing unsure whether I’d checked it, returning to the locker, annoyed the whole way about the time I was almost certainly wasting; approaching the locker with such a complete expectation that it was locked that my mind wandered and I barely noticed myself check it so that when, moments later, I was leaving the school again, I wasn’t one hundred per cent sure that I’d checked it or that, in that moment of complacent absent-mindedness, I’d have noticed if it wasn’t locked; turning back again.

To say that this could go on for hours would be an exaggeration but it could take a quarter of an hour. In time I learned that the key was to concentrate when checking the locker. Take a mental photograph of the moment. Say to myself: ‘Here I am, now, me, sane, with a locked locker. Remember this in the doubting moments to come.’

But the concentration is tiring so, having gone through it with the door today, I’m unwilling to unlock it to go and check the gas when, by peering through the window, I can probably check the alignment of the hob knobs. (I wonder if that’s where the biscuit got its name. I’m suspicious about that biscuit’s name. It’s like Stinking Bishop: recent, yet quickly adopted as a go-to reference for those wishing to be cosily humorous. It got its Alan Bennett licence too early and easily. I suspect the advertising agency was involved.)

I adjust the collar of my jacket, massaging a slightly jarred wrist from my high-energy security check. It’s a spring day and slightly too warm for a jacket really – certainly once I get walking. Unless the temperature is absolutely Siberian, a brisk walk always warms me up, especially when I’ve got a jacket on. Or at least warms up the middle of my back, which then sweats through my shirt. So I have to wear a jacket to hide that.

My walk begins on the exterior staircase from my flat, which I have to descend carefully in case there’s sick or a used needle. Listen to me, glamorising the place! There’s never sick or a needle! This is Kilburn, not Harlesden. I mean wee or a bit of cling-film from one of those little cannabis turds. Sometimes some kids are sitting at the bottom. One of them might say: ‘Hey, are you the guy from Peep Show?’ I am, so I nod.

I don’t know how I ended up in Kilburn. I’m not from here – but then hardly anyone who lives in London is from there. I think it’s slightly weird to be from London. As a child, London terrified me, largely because I considered it to be the British manifestation of New York which, on television, looked like a living hell. I think I’m largely basing this on Cagney and Lacey, who seemed to have a horrible time. It was all drugs and crowds and scruffy offices and huge locks on the inside of apartment doors.

The size of those locks was unnerving. Who or what were locks that sturdy and that numerous meant to keep out? And by the time such a gang or monster, or drug-addled gang made monstrous by their craving, was bashing on the door, you might as well just open it and hope they kill you quickly, because what’s the alternative? Escape via the garden? Oh no, no one has a garden. There’s a park you can get to on a frightening underground train full of junkies, and where you can maybe play a bit of frisbee while old ladies are raped in the bushes around you, but this is a world without gardens, without swingball and where it certainly isn’t safe to ride your bike with attached stabilisers along the pavement.

That’s what I assumed London was like. My childhood self would hate where I live now. He would also be disappointed that I’m not ruler of the world or at least Prime Minister or a wizard. But the fact that, far from a castle, mansion or cave complex, I don’t even live in a normal house with a garden and an attic and a spare room would basically make me indistinguishable, to his eyes, from a tramp.

Growing up, there were metaphorical stabilisers attached to my whole life. Born in Salisbury, brought up in Oxford and a student in Cambridge, I was 22 before I had to deal on a daily basis with anywhere other than affluent, ancient, chocolate-box cities where murders never happen but murder stories are often set. I was cosseted in deep suburban security and probably fretted about the outside world all the more as a result.

I have often suffered from the fact that warnings are calibrated for the reckless. Very sensibly, parents, teachers and people at TV filming locations who provide you with blank-firing guns for action sequences (to pick three random types of authority figure) design their remarks to prevent the fearless from accidentally killing themselves. ‘Don’t look at the sun or you’ll go blind’ … ‘A blank-firing gun is an incredibly dangerous weapon’ … ‘Verrucas can kill.’

The collateral damage is every last scrap of more timorous people’s peace of mind; the sum of their warnings makes people like me view life as a minefield. So my childhood, as I remember it, was laced with fear.

But, before I can remember, there was definitely a moment of recklessness – when I pushed at the stabilising boundaries that my doting parents had set for me. This was in Salisbury – in fact a little village just outside called Stapleford where we lived in a bungalow. I couldn’t walk but I did have a sort of walker – a small vehicle with a seat and wheels, but no engine, that I could propel along, Flintstones-style, with my bare feet. Having mastered this contraption, I apparently became unwilling to learn to walk properly but would career around in it at high speeds.

One day I took a corner too fast and smacked my head on a skirting board. There was blood everywhere. I was scarred for life. Literally. I still bear a tiny scar in between my eyebrows of which I was immensely proud as a child. And now I don’t drive. Can that be a coincidence? No, I say it CANNOT be a coincidence. Before that crash I was a fearless speed junky. I was destined for Formula One greatness. Also I was brimming with infant brain cells of which the crash must have led to a holocaust. My timorousness, my lack of a driving licence, the tiny mark on my face, my B in GCSE Biology all stem from that moment. If you don’t like this book, blame the corporate child abusers who made that deathtrap walker.

Maybe everyone is fearless in infancy and what marks us apart is our ability to absorb fears – some of us are made of sponge and soak them up while others are resistant willows that have to be repeatedly painted with the linseed oils of caution to prevent cracking from the dehydrating effect of their own imprudence. And, before you ask, no I haven’t lost control of that metaphor: I’m saying some people are thoughtful, sensitive types like me while others are wooden-headed idiots as a result of whom every foodstuff has to carry an over-cautious ‘Use by’ date. I think I should bloody sue.

I carry on along my road towards the Kilburn High Road. In many ways the Kilburn High Road isn’t very nice – it’s messy, often crowded, usually gridlocked, has a large number of terrible shops selling cheap crap, lots of places selling dodgy kebabs, about two others selling kebabs that are probably okay, pawnbrokers, pay-day loan sharks, old Irish pubs, closed old Irish pubs, closed old Irish pubs that have tried and failed to go gastro, closed old Irish clubs that have tried to go a bit nightclubby, the worst branch of Marks & Spencer in Britain and a little paved area which was almost certainly designed by ’60s planners to give the place a sense of community but is primarily used by people trying to encourage you to become Christian or Muslim with the use of leaflets, megaphones and sometimes both. There’s also an Argos.

But I like it. You probably saw that coming. I expect you’re expecting me to say that it’s vibrant next. Well it is. And also, I’m used to it and I tend to like what I’m used to. I’m not going to be here much longer but I expect I’ll come back and visit. (I expect I won’t.)

Oh, and also it’s on a Roman road, which I like. I get a sense that there’s something genuinely ancient about Kilburn as a scuzzy little strip development along the Roman road into London: that London needs, and has always needed, these little pockets of grubby prosperity. And so, as well as liking the vibrancy and familiarity, I’m comforted by the thought that Kilburn is a constant in a changing world. When the recession hit in 2008, a lot of Kilburn’s pound shops and garage-sale-style outlets closed, like weeds knocked back by a harsh frost. But they grew back in the next few months, with different names but the same displays of stuff which I can’t imagine anyone ever wanting to buy. I found that cheering.

My parents like Kilburn – they liked it as soon as I moved in, despite making the mistake of eating in the greasy spoon café at the end of my road. They’re not fussy eaters but they hate bad service. They used to be hotel managers – in the 1970s, the era of Fawlty Towers and of a Britvic orange juice being an acceptable starter. But I think they were good hotel managers, for the time. That’s what they’ve always led me to believe, and they’re not, in general, boastful people.

When I was born they were joint managers of the White Hart hotel in Salisbury. They weren’t from Salisbury – my mother grew up in Swansea and my father in Liverpool – but they’d met on a degree course in Glasgow, where they were studying hotel management. And then they got married and became hotel managers and got a job working for a hotel chain and were posted to Salisbury. Posted in the military sense. I think they probably went by car.

So: Ian and Kathy Mitchell, a husband and wife running a West Country hotel in the 1970s. But instead of a Spanish waiter, they had a baby, who they kept in the cleaners’ cupboard when they were working. This was primarily because it was a large enough cupboard to have a phone in it. By which I mean, it actually had a phone in it. Almost every cupboard is large enough to have a phone in it, otherwise it’d barely be more than a box attached to a wall. I mean large enough to warrant the fitting of a phone line. So it was really a sort of terrible room. Or an amazing cupboard.

Anyway, it was where they kept the cleaning equipment for the hotel. The first word I ever said was ‘Hoover’. I didn’t even know that other brands of vacuum cleaner were available.

And the relevance of the phone? It was so I could order stuff on room service. And also so that it could be put on ‘baby monitor’, which meant that someone on reception could listen in and hear if I was crying, rather than asleep or dead, which very different states share the attribute of not requiring immediate action.

They stopped being hotel managers when I was two and we moved to Oxford, where my dad got a teaching job at the polytechnic. The decision was always explained as being to do with me – that running a hotel and family life were incompatible – which I suppose makes sense. Then again, thinking about it, my friends with children seem to find the first two years of childcare the most onerous and it always seems the impact on their careers is lessened thereafter. So maybe my parents were sick of running hotels for other reasons and rationalised it as a family decision, or just very wisely expressed it to me that way so I’d feel grateful at their sacrifice rather than irritated that they no longer had interesting jobs.

I was a bit sorry, as a child, that they didn’t run a hotel any more. And that when they had, I’d been too young to notice anything more than an industrial Hoover. (My first adjective was ‘industrial’.) (It wasn’t.) I love hotels – they’re fun and fascinating – and having one to run around in, albeit carefully and with a beady eye fixed on sharp skirting boards, would have been brilliant.

And I wanted there to be a place of which my parents were in charge. I’m hierarchical like that. I wanted them to have people working for them rather than just lots of ‘colleagues’. That makes me sound like a bit of a megalomaniac. But my hunch is that most children are like that. Ideally, my parents would have been a king and queen. Failing that, hotel manager seemed to me a bit higher up the scale than ‘people who teach hotel management at a polytechnic’. When I got older, a different snobbery came to bear: the polytechnic became a university and ‘university lecturer’ seemed better than ‘hotel manager’ – more to do with learning and less with trade. So my view changed over the period of my minority as I changed from one kind of little shit to another.

This will be grist to the mill of people who think I’m a posh twat. ‘Listen to him, nasty little snob,’ they will be thinking. They will also probably be wondering why they’ve bought a copy of his book. Or maybe not. Perhaps there’s a constituency of people – the most rabid online commenters, for example – who actually seek out the work of people they loathe. They may be skimming each page with a sneer before wiping their arse on it and flushing it down the loo. Or attempting to post it to me. If so, I’d like to say to those people: ‘Welcome! Your money is as good as anyone else’s.’

But of course being a snob and being posh are different things. Being a snob, a conventional snob, involves wanting to be posh whether you are or not, and thinking less of people who aren’t. Wanting to be posher, usually – which is why the very poshest people are seldom snobs: they know they can’t be any posher so it’s no good wishing for it.

I plead guilty to being a snob when I was a child. I definitely valued poshness, jealously guarded it to the extent that I felt I possessed it, and wanted more. My instinct was not to despise the social hierarchy but to want to climb it. So maybe it serves me right that I now get called posh all the time, when I’m not really and I’ve long since realised that it’s a worthless commodity. In fact, career-wise, it would have been more fashionable to aspire in the other direction. But I didn’t have the nous to realise that there would be any advantage in playing the ‘ordinary background’ card – or that, as a child of underpaid polytechnic lecturers, albeit one sent to minor independent schools thanks to massive financial sacrifices on those parents’ part, I completely qualified for playing it.

Had I guarded my t’s less jealously and embraced the glottal stop, I could have styled myself a person ‘with an ordinary background who nevertheless got to Cambridge and became a comedian’ rather than ‘an ex-Cambridge ex-public schoolboy doing well in comedy like you’d expect’. Both descriptions are sort of true, but people like to polarise and these days I might have been better off touting the former.

Still, I’d have been giving a hostage to fortune. The estuary-accent-affecting middle classters always get hoist by their own petard in the end, when it turns out that Ben Elton is the nephew of a knight or Guy Ritchie was brought up in the ancestral home of his baronet stepfather.

The thing is, I find the idea that my life has followed an unremarkable path of privilege rather comforting. I wanted to think I was posh because I felt, not entirely without justification, that bad things didn’t happen to posh people. If other people thought I’d be all right – even in a resentful way – I could believe it too.

So, in the binary world of popular opinion, I got dumped on the posh side of the fence – which is sometimes annoying as it denies me the credit for any dragging myself up by my bootstraps that I might have done (it’s not much but, you know, we never had a Sodastream). It also leaves me worrying that people will think I’m claiming to be properly posh – when proper posh people know I’m not. My blood is red and unremarkable. (Although I always remark when I see it, as my scant knowledge of medicine leads me to believe that it’s not really supposed to come out.)

This is a roundabout way of saying that my background was neither that of a Little Lord Fauntleroy, as the people who write the links for Would I Lie to You? would have it; nor was it the opposite.

But who, in the public eye, is really the opposite? Very few people who come to prominence, other than through lucrative and talent-hungry sports, genuinely come from the most disadvantaged sections of society – we just don’t live in a country with that amount of social mobility. Which is why famous people who went to a comprehensive and can sustain a regional accent do themselves a lot of favours by letting those facts come to the fore, so that journalists can infer a tin bath in front of the fire and an outside loo rather than civil servant parents who were enthusiastic theatre-goers.

Perhaps you think I’m thinking of Lee Mack. Well, I am now, obviously. But I don’t think his parents were civil servants and I wouldn’t say Lee has ever seriously pretended to be anything he’s not, any more than I have (which is quite an indictment of both our acting powers). That said, on Would I Lie to You? we’re very happy to milk comedy from people’s assumptions that he keeps whippets and I’ve got a beagle pack. And we’re both amused by the underlying truth that, in terms of our values and attitude, we’re incredibly similar. We’re middle class. We’re property owners who would gravitate towards a Carluccio’s over a Pizza Hut. I bet he’s got a pension. I know he’s got a conservatory. He used to have a boat on the bloody Thames! I live in an ex-council flat, for fuck’s sake!

But he’s got a regional accent, so the audience makes certain assumptions and I’ll happily play to them. If he doesn’t claim to be working class, I’ll do it for him. So – in spite of everything I’ve said about people’s instinct to polarise, and worrying about appearing to be something I’m really not – I’m also quite happy to accept a cheque for telling Lee not to get coal dust all over the studio while he wonders whether I shouldn’t offer a glass of water to the footman he claims I’m sitting on.

It’s a lot easier than going on TV with the premise that you’re basically normal.

- 2 - (#u04b57298-596e-5838-a99b-cfab9a8c8d06)

Inventing Fleet Street (#u04b57298-596e-5838-a99b-cfab9a8c8d06)

I’m not taking a direct route because I want the walk to last over an hour. It’s the brisk continuous walking that seems to be the best back medicine. So I turn left down Quex Road. Some of the road names round here are brilliant: just off Quex are Mutrix Road and Mazenod Avenue. Quex, Mutrix and Mazenod! They sound like robots. I wish I’d ever written anything that needed three names for robots so I could have used those. In fact, what am I doing writing this? It should be a sci-fi epic about Quex, Mutrix and Mazenod, three evil cyborgs blasting their way around the galaxy and seeing who can destroy the most planets.

I think the main reason I associate those names with robots is that I’ve always had a feeling that ‘x’ and ‘z’ are the most futuristic letters. I don’t really think they are. In fact I’m pretty sure ‘x’ in particular is about as ancient as a letter can be – it’s just two lines, after all. Anything less than that and it’s not really writing. It’s just a mark. But, because they’re not very useful letters, they somehow feel like the alphabetical equivalent of shiny silver jumpsuits.

Sadly those three street names have nothing to do with space or the future and everything to do with places in Kent. The family who owned the estate on which that bit of Kilburn was built also owned a Quex House in Kent. Mutrix and Mazenod are nearby villages. It’s a bit of a dull explanation for the names, really. Of course I’ve no idea why those villages are called that. I expect it’s because some space robots once attacked Kent. Yawn.

The first street name I was aware of was Staunton Road, which is where we moved to in Oxford. The second was Fleet Street. That’s because my parents were constantly being hassled by paps. Not really. I became aware of Fleet Street at the point when I thought it was a phrase I’d invented. It was a road name I came up with for my toy cars to drive along. I was so sure it had originated in my brain that when I came across it again, in a story about Gumdrop the vintage car (I was terribly interested in cars at the time but managed to get it out of my system a decade before everyone else got a driving licence), as a name for an ancient and famous London thoroughfare, I was furious.

I was convinced that I’d thought of it entirely separately and it seemed so unfair to me that, having displayed the genius to come up with such a demonstrably successful name for a street (I think I assumed that Fleet Street’s prominence and centuries of prosperity were somehow because of its name), I should go unrewarded. I felt like a victim of history. I could so easily have been born hundreds of years earlier and been the one to come up with the name in the first place. Surely this would have brought me great fame and fortune, I thought. I didn’t seem to realise that the identity of the inventor of the name ‘Fleet Street’ is lost in the mists of the past and that whoever it was probably went to his or her grave unlauded and unremunerated for having named a street after the nearby Fleet river.

I don’t know whether this means I was an imaginative child. I think that’s how I thought of myself, though. I was an only child for the first seven and a half years of life and so I spent quite a lot of time on my own, inventing games and pretending to be other people. I loved dressing up but at the same time it made me ashamed – very much like masturbation a few years later.

In my special costume trunk (box of old clothes) I had a highly patterned lime green and brown jumper which was too small for me but was my outfit for being someone to do with Star Trek (not actually Captain Kirk – I think I styled myself his boss). In truth there was nothing remotely Star Trekky about it, but the way it clung to my arms reminded me very much of the way the shirts in Star Trek clung to people’s arms. I also had an old pocket calculator which I could flip open in a way that was satisfyingly reminiscent of a communicator.

And then there was a black mac. I got tremendous use out of that black mac. It spent a while as the coat I wore as one of the versions of Doctor Who I pretended to be – I think I was essaying a slightly more rainproof version of the Peter Davidson incarnation. I definitely remember putting some foliage into the buttonhole at one point to represent the stick of celery he always had pinned to his. My mother was reluctant to provide actual celery for such trivial use, which is a shame because, as it turned out, that moment of asking was the only point in my life when I was ever going to see any point in celery.

But the mac’s starring role was as the – what I now realise is called – ‘frock coat’ of an eighteenth-century king. At the time I didn’t know he was eighteenth-century, but I’ve since worked out that this was the era of historical dress I was trying to emulate when I tucked my trousers into my socks and tied a bit of string round the tails of the coat.

This is the costume I most associate with shame. I remember one Saturday, when I was wearing this costume, some older children from next door rang the doorbell because they’d hit a ball into our garden and, as my parents let them in, I was immediately and forcibly struck with shame and humiliation at my appearance and ridiculous inner life. I couldn’t have felt worse if I’d been caught wearing lipstick and a dress.

I don’t think the ball-searchers noticed at all, but I remember going off to search for the ball at the opposite end of the garden to everyone else – in a place where it couldn’t possibly have landed – just to be able to hide from them. Everyone was saying, ‘It won’t be there – what are you doing? Come and look over here!’ while I mumbled that I was just going to check here down behind the garage where no one could see me. I could sense that, more than the costume, this behaviour was making me seem like a weirdo.

That feeling of being a weirdo oppressed me. Conventional to the core, I was keenly aware that my dressing-up-and-pretending-to-be-other-people games weren’t as wholesome as climbing trees or playing football. I had a sense that there was something effeminate about dressing up – and certainly there was no worse accusation that could be levelled at me as a small child than that I was like a girl.

Maybe it was a forerunner of my early teenage fear that I might turn out to be gay. I don’t mean that to sound homophobic, although I probably was homophobic at the age of thirteen – God knows my school was a homophobic environment – but there’s no doubt that I didn’t want to be gay. I thought that would be awful and would lead to a life of mockery and self-loathing. And, as a natural pessimist, I was quite sure that my eagerness not to be gay meant I definitely would be.

I’m not. As you must have guessed by now. I mean, they’d have put that on the cover. I think I had the odd crush on girlish-looking boys in my early teens but never to the extent that I’d do anything about it or in a way that registered on the same level as my feelings when I met real girls. I hope that doesn’t disappoint anyone, by the way. Some people have speculated on the internet that I might be gay, which troubles me only in the implication that, if I were, I’d think there was something wrong with that or try to hide it.

In many ways, I think I might have been happier in my later teens if I had been gay. Certainly it would have been a difficult thing to come to terms with during puberty but, having done so, I would have had a justified sense of achievement at being brave enough to come out. Also my all-male educational history wouldn’t have thrown up such a barrier to flirting. I was basically a bit afraid of girls and women for a long time, in a way I don’t think I would have been about men even if those were the sort of human I had turned out to fancy.

Anyway these fears, doubts and thoughts were a long way ahead of me as I searched for a tennis ball where I knew there wouldn’t be one, with my trousers tucked into my socks, a bit of string tied around the mac I was wearing in the sweltering sun and plastic sword at my side. The fact that I was not a king was never more bitterly apparent than at that moment. I was just a small boy and not quite as normal as I’d have liked.

I felt I should be more into Lego. I was conscious that I wasn’t a keen reader – I much preferred television. I wanted to like porridge. It bothered me that I wasn’t more focused on the acquisition of sweets and chocolate. I’ve never been a healthy eater – my palate perversely favours fats and alcohols while sending troubled if not protesting messages to the brain when confronted with vegetation or roughage – but I’ve never much liked sweets. I like puddings, but sweets – sweet-shop sweets, cola bottles, refreshers, stuff to do with sherbet – have never really been to my taste. Which presents a bit of a problem if you aspire to be a normal boy. It’s like being a socialist on Wall Street: you find yourself not wanting the currency.

So I settled on chocolate as a respectable sort of sweet to aspire to owning. And I liked chocolate, just nowhere near as much as toast. At Christmas and Easter, therefore, I would be given quite a lot of chocolate. I would be aware that this was a good thing; that, in the economy of children, I was briefly rich. This was a state of affairs to be cherished, I reasoned. So I wouldn’t eat it. I’d hoard it. This took very little self-control as the pleasure I took from eating chocolate was massively outweighed by the displeasure I endured from ceasing to own it.

What a natural miser, you might think. I hope not – and I don’t think so. In general, I like what money buys more than the money itself. But I don’t spend a lot on chocolate. Of course, my nest egg – or nest of chocolate eggs – was no good to me. When I returned to my stash weeks later, it had taken on the taste of the packaging and developed that horrible white layer. A poor reward for my prudence.

I have no idea whether these feelings of oddness and inadequacy are normal and, if so, whether I felt them to a greater or lesser than normal extent. Is it normal to feel you’re not normal but want to be normal? I think it probably is.

I certainly don’t think that those feelings drove me to comedy. Although it may explain some of the murders (see Book 2).

I’m always suspicious of that ‘comedy comes from pain’ reasoning. Trite magazine interviewers talk to comedians, tease a perfectly standard amount of doubt, fear and self-analysis out of them and infer therefrom that it’s this phenomenon of not-feeling-perpetually-fine that allowed them to come up with that amusing routine about towels.

Well, correlation is not causation, as they say on Radio 4’s statistics programme More or Less. Everyone’s unhappy sometimes, and not everyone is funny. The interviewers may as well infer that the comedy comes from the inhalation of oxygen. Which of course it partly does. We have no evidence for any joke ever having emanated from a non-oxygen-breathing organism. At a sub-atomic level, oxygen is absolutely packed with hilarions.

What distinguishes the comedian from the non-comedian, I always want to scream at the interviewers, is not that they are sometimes unhappy, solemnly self-analyse or breathe oxygen but that they reflect upon these and other things in an amusing way. So stop passing this shit off as insight, interviewers. You’ve not really spotted anything about the people you’re speaking to. You think you see unusual amounts of pain when it’s just performers politely glumming up so as not to rub your noses in the fact that their job is more fun than yours. So they mention that they sometimes feel lonely and hope the article plugs the DVD.

I suspect that my levels of infantile self-doubt were no more remarkable than my year of birth – which is 1974, by the way. And I certainly didn’t feel inadequate all, or even most, of the time. I often felt special and clever and like I’d probably grow up to be a billionaire toy manufacturer or captain of the first intergalactic ship with a usable living room. In those moods I didn’t want to be normal.

If I was a happy little four-, five- or six-year-old – and I think I probably was, for all my worries and doubts – it’s thanks to my parents. They always gave me the impression that they were delighted by my very existence – that I rarely did anything wrong and, if I actually did anything right, then that was a tremendous cherry on the amazing cake. I was made to be well-behaved in front of other people, but I certainly felt I could say anything to them – scream, rage, cry, worry, speculate as to the presence of wasps, ask to be addressed in the manner of an eighteenth-century king, pretend to be in a spaceship or on television, suddenly need the loo – and all would still be well.

There is really only one thing I remember about their general parental shtick which irritates me now, and that was their attitude to Oxford. They were really quite down on it. I suppose they’d only just moved there and didn’t particularly feel welcome or like they belonged there – in contrast, I think, to Salisbury with which they’d also had no previous connections but had immediately loved. My mother missed living by the sea – she still does – and my dad, who grew up in the north, has never had the accent but developed a little of the sixth sense for snootiness. And you don’t need a sixth sense for snootiness to detect it in Oxford. It’s undoubtedly a snooty place. But then it’s got a fair bit to be snooty about. (It’s also got a massive chip on its shoulder about Cambridge, which is understandable.)

I think my mum and dad imagined they’d move somewhere else before too long, so they discouraged me from getting attached to the place. You’re not really from here, you were born in Salisbury, your mum’s Welsh and your dad’s a bit Scottish, so you’re not even really English – you’re British and not really from the only place you can remember ever being in. That was the message I was given. And I can understand why.

But that’s not much use when you’re four, when you’re looking for the things that define you. You want a home town and you want to be able to bask in the illusion that it’s the best place in the world. You might even consider supporting the football team.

Such securities were denied me because, while they never said Oxford was a dump and would always concede that it was a beautiful place with a famous university, I was never allowed to forget the city’s failings – and indeed England’s. England, I was given the impression, was the snootiest part of Britain and consequently undeserving of my allegiance.

My parents still live in Oxford and I’d be very surprised if they ever leave. They have lots of friends in the area and they’ve grown very fond of it. My brother, Daniel, was born there and our parents were already coming round to the place by then. Consequently he did support the football team for a while and feels tremendous allegiance to the city, to the extent that he has, up till now, neglected to move away.

So I’ve always felt a bit rootless, but without any of the cachet of most rootless people. You know the sort: Danish father, Trinidadian mother, live in Thame (I’m thinking of a specific boy in my class). For people like that, the fact that they have no single place of allegiance is part of what defines them – it’s interesting and glamorous. Being definitely British but with your loyalties split between various unremarkable parts – Oxford, Swansea, Salisbury, the Scottish Borders – has no exotic upside to compensate for the absence of a one-word answer to the question: ‘Where are you from?’

The Danish-Trinidadian boy had real candles on his Christmas tree, which necessitated having a fire extinguisher on stand-by. And he was called Sigurd Yokumsen. I bet no one ever mistakes him for a fucking novelist.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/david-mitchell/david-mitchell-back-story-39772389/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

David Mitchell

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Юмор и сатира

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 18.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: David Mitchell, who you may know for his inappropriate anger on every TV panel show except Never Mind the Buzzcocks, his look of permanent discomfort on C4 sex comedy Peep Show, his online commenter-baiting in The Observer or just for wearing a stick-on moustache in That Mitchell and Webb Look, has written a book about his life.As well as giving a specific account of every single time he′s scored some smack, this disgusting memoir also details:• the singular, pitbull-infested charm of the FRP (‘Flat Roofed Pub’)• the curious French habit of injecting everyone in the arse rather than the arm• why, by the time he got to Cambridge, he really, really needed a drink• the pain of being denied a childhood birthday party at McDonalds• the satisfaction of writing jokes about suicide• how doing quite a lot of walking around London helps with his sciatica• trying to pretend he isn’t a total **** at Robert Webb’s wedding• that he has fallen in love at LOT, but rarely done anything about it• why it would be worse to bump into Michael Palin than Hitler on holiday• that he’s not David Mitchell the novelist. Despite what David Miliband might think