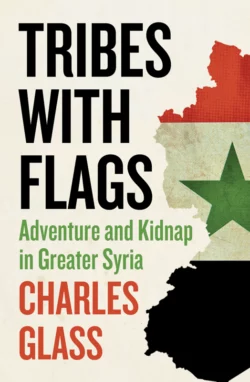

Tribes with Flags: Adventure and Kidnap in Greater Syria

Charles Glass

‘Tribes With Flags’ is the gripping story of Charles Glass's dramatic journey through Greater Syria which provides background context to a troubled region once again in the headlines.Charles Glass began his journey through the former Arab nations of the Ottoman Empire by exploring farms, refugee camps and feudal palaces to capture the full spectrum of Levantine life. But his literary and spiritual ramble was abruptly interrupted when on 17 June 1987 he was kidnapped by Shi'a militants. What followed, 62 days later, was a daring escape that captivated the world’s media.In this classic travelogue, the former ABC Middle East correspondent records an adventure which took him through Turkey, Syria, Israel, Jordan and the Lebanon. An honest, colourful and immediate tale of wanderlust and history, ‘Tribes with Flags’ is an essential back-story to our understanding of the complexity of the region, and the gripping testimony of one of the few hostages who has escaped its maelstrom to tell his tale.

TRIBES

WITH

FLAGS

Adventure and Kidnap in Greater Syria

CHARLES GLASS

Dedication (#ua3066dda-5bba-5807-a4ca-2473aaec538d)

For Julia, Edward, George, Hester,

Beatrix and Fiona

and to the memory of Mouna Bustros

Detail from “Syria”, Tallis’ Atlas, 1841

Epigraph (#ua3066dda-5bba-5807-a4ca-2473aaec538d)

“A man may find Naples or Palermo merely pretty;

but the deeper violet, the splendour

and desolation of the Levant waters

is something that drives into the soul.”

James Elroy Flecker

Beirut, October 1914

CONTENTS

Title Page (#ucc81769e-846f-5fb7-b545-91129f94b440)

Dedication

Frontispiece (#uc2ffe8cd-2d01-57b1-bca9-9b7d1bb790b9)

Epigraph

New Introduction by the Author

PART ONE

1The Legacy of Alexander

2The Army of the Levant

3The Last Ottoman

4Minarets and Belfries

5No-Man’s-Land

PART TWO

6Six-Star Brandy

7Where Armies Failed

8A Consular City

9The Survivors and the Dead

10The Village of a Pasha

11The Road

PART THREE

12The Old City

13Meleager’s World

14This Bad Century

15Queen of the Desert

16Provincial Loyalty

17Enemies of the Goddesses

PART FOUR

18Excursions

19A Blood Feud in the Mountains

20Foul is Fair

21The Ghetto

22Monks and Martyrs

23The Family and the Plain

24The Slumber of the Dead

25Disrespectful Dancing

26The Last Day

PART FIVE

27The Black Hole

28Recalled to Life

About the Author

Also by Charles Glass

Copyright

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION (#ua3066dda-5bba-5807-a4ca-2473aaec538d)

Twenty-five years ago, I traveled by land through what geographers called Greater Syria to write a book. The journey began in Alexandretta, the seaside northern province that France ceded to Turkey in 1939, and meandered south through modern Syria to Lebanon. From there, my intended route went through Israel and Jordan. My destination was Aqaba, the first Turkish citadel of Greater Syria to surrender to the Arab revolt and Lawrence of Arabia in 1917. For various reasons, my journey was curtailed in Beirut in June 1987. (I returned to complete the trip and a second book, The Tribes Triumphant, in 2002.)

The ramble on foot and by bus and taxi gave me time to savor Syria in a way I couldn’t as a journalist confronting daily deadlines. People loved to linger over coffee and tea, play cards, and talk.

Many of the civilian members of the Baath Party, whose founders claimed to believe in secularism and democracy, deserted its ranks when the party took power in 1963. They rejected the militarization of the party, which kept power not through elections but by force of the arms of its members within the army. Among those who left the party was the father of Rulla Rouqbi. I met his daughter a few weeks ago at the hotel she manages in Damascus. Faissal Rouqbi had died in April 2012, and this explained why the attractive fifty-four-year-old was dressed in black. A vigorous supporter of the revolution that began in Syria a year earlier, she believed hers was the same struggle her father had waged against one-party military rule.

“I was questioned twice by the security forces,” she told me in the hotel’s coffee shop, which looks out onto a busy downtown street. “They did it just to show me they know what I am doing and they are here.” She said that, because young dissidents gathered in her coffee shop with their computers, the police cut the hotel’s WiFi connection. Nonetheless, several young people were there discussing the rebellion—much as their forefathers did in the old cafés of the souks that the French destroyed to put down their revolts—over strong Turkish coffee or newly fashionable espresso.

The rebellion against tyranny was by 2012 turning into a sectarian and class war that threatened to destroy Syria for a generation and drive out those with the talent, education, or money to thrive elsewhere. Neither side spoke of conciliation. The endgame for each was the destruction of the other. Foreign backers appeared, as in Lebanon from 1975 to 1990, to encourage confrontation in their own rather than Syrian interests. Nothing had changed since Britain and France occupied the Ottoman provinces of Greater Syria during World War I.

A glimmer of hope came from the economist Nabil Sukkar, formerly with the World Bank. “The opposition is not going to retreat,” he told me in Damascus. “The stalemate could last to 2014.” Bashar al-Assad’s term of office was scheduled to end in that year, when, Sukkar believed, he could stand down without losing face or having his Alawite community punished. He continued, “For [Kofi] Annan to succeed, there has to be compromise from both sides. The regime must stop killing, and the opposition must stop smuggling [arms]. And foreigners must stop sending arms. Then there can be a cease-fire and a transition government.” However unlikely that seems today, it could work if Russia and Iran compel the regime and the United States, Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Qatar push the opposition to achieve it. Otherwise, Syrian will fight Syrian—just as the Lebanese did—in what the respected Lebanese journalist Ghassan Tueini called “a war for the others.”

Three great fears dominated the uprising of 2011 and 2012: that the regime would emerge stronger and more violent; that Syria’s traditional tolerance and respect for people of different religious and ethnic communities would falter if a strongly Sunni Muslim fundamentalist regime replaced it; and that, with neither side able to destroy the other, the conflict would escalate and linger as Lebanon’s did. Nowhere were these fears more apparent than in my favourite Syrian city, Aleppo.

Archaeologists believe that human beings settled on the hilltop that became Aleppo, on the plains two hundred miles north of Damascus, around eight thousand years ago. Cuneiform tablets from the third millennium BC record the construction of a temple to a chariot-riding storm god, usually called Hadad; mid–second millennium Hittite archives point to the settlement’s growing political and economic power. Its Arabic name, Haleb, is said to derive from haleb Ibrahim, “milk of Abraham,” for the sheep’s milk the biblical patriarch offered to travelers in Aleppo’s environs. Successive conquerors planted their standards on the ramparts of a fortress that they enlarged and reinforced over centuries to complete the impressive stone Citadel that dominates the city today.

“It is an excellent city without equal for the beauty of its location, the grace of its construction and the size and symmetry of its marketplaces,” wrote the great Arab voyager, Ibn Battutah, when he visited in 1348. During the Renaissance, Aleppo was Islam’s third most important city, after Constantinople and Cairo. The modern Lebanese historian Antoine Abdel Nour praised it in his Introduction à l'Histoire Urbaine de la Syrie Ottomane: “Metropolis of a vast region, situated at the crossroads of the Arab, Turkish and Iranian worlds, it represents without doubt the most beautiful example of the Arab city.” Its beauty reveals itself in the elegance of its stone architecture, redolent of historic links to Byzantium and Venice; and in the diversity of its peoples—Arabs, Armenians, Kurds, eleven Christian denominations, Sunni Muslims, a smattering of dissident Shiite sects from Druze to Ismailis, ancient families of urban patricians, and peasant and bedouin immigrants from the plains—that make it a microcosm of all Syria.

Documentary records of Ottoman Turkey’s dominion over Aleppo from 1516 to 1918 portray communities of Muslims, Christians and Jews living in the same neighborhoods. In Tunis, Jews were obliged to rent living space, by contrast, Aleppo’s governors imposed no restrictions on house ownership by members of any religious group or by women. It was not unusual for large mansions to be divided into apartments in which Muslim, Jewish and Christian families dwelled with little more than the usual rancor that afflicts neighbors everywhere. Unlike more xenophobic Damascus, Aleppo encouraged Europeans to trade and dwell within the city walls. The European powers, beginning with Venice in the sixteenth century, established in Aleppo the first consulates in the Ottoman Empire, to guard the interests of their expatriate subjects. Descendants of Marco Polo, the Marcopoli family, retained the office of Italian honorary consul well into the twentieth century.

In a neglected corner of the old Bahsita Quarter, behind several old office buildings, stands a monument to Aleppo’s historic mélange. The Bandara Synagogue was built on a site of Jewish worship that predates by two centuries the AD 637 Arab-Muslim conquest of Aleppo. Its courtyard of fine cut-stone arches and domes resembles the arcaded cloister of the nearby Al-Qadi Mosque. The Jewish community of Aleppo, like its larger counterpart in Damascus, gradually made its way to New York after the founding of Israel. The last Jews departed en masse in 1992, when then-President Hafez al-Assad lifted restrictions on their emigration. Suddenly, Damascus and Aleppo were bereft of an ancient and significant strand of their social fabric. The synagogue, restored by Syrian Jewish exiles, is the forlorn relic of a community that thrived for ages before vanishing under the weight of war between Syria and Israel. It is also a harbinger of what Aleppo’s Christians apprehend as their fate if the latest uprising leads to all-out war or domination by Sunni Muslim fundamentalists.

“Am I worried?” Archbishop Mar Gregorius Ibrahim Yohanna, metropolitan in Aleppo of the Syrian Orthodox Church asked rhetorically. “Yes. Am I afraid? No.” The archbishop’s concern is widespread among Christians of both Arab and Armenian origin, who claim to make up nearly 10 percent of Aleppo’s 2.5 million people. (Their proportion, while half what it was fifty years ago, may have halved again to 5 percent, owing to Christian emigration, a low birthrate, and the steady influx of rural Muslims into the city. The Syrian government does not publish statistics by religion.) The archbishop, whose PhD thesis at Britain’s Birmingham University was on Arab Christianity before Islam, insisted that Christians should not take sides between the government and its opponents. Unlike the Christians of Lebanon, Syrian Christians do not have their own political parties or armed militias. Mar Gregorius elaborated, “The only weapon we can use is to leave the country. I don’t believe it’s right.” Those who are leaving, even if only for the duration of the conflict, provide a rationale similar to the one Syrian Jews gave me in 1992: they were escaping, not the Assad regime, but the Muslim fundamentalists who might overwhelm it.

“Many Christians have left,” Dr. Samir Katerji, a fifty-eight-year-old architect and member of the Syrian Orthodox Church, told me. “Many Armenians have bought houses in Armenia. Even the Muslims are leaving.” Katerji, who designed the amphitheater for outdoor films in the Aleppo Citadel, had “visited my aunt’s house,” a local euphemism for going to prison, several times. The security services arrested him for his outspoken criticism of the Assad regime and the Baath Party. “I feel the majority of the Syrian people is against this government,” he told me over a drink in his office. “It’s a very bad government. Governments and armies everywhere are dirty, even the Vatican.” While lamenting Syria’s lack of basic political freedoms, including free speech and assembly, he acknowledged, “We have social freedom. We are free to declare our thoughts and beliefs and to practice our Christianity.” He condemned murderers within the regime, but had no faith in the regime’s armed opponents: “Inside the opposition are also murderers who will not allow stability.”

Instability brought on by armed rebellion, mass demonstrations, regime violence, and economic sanctions has unsettled Syrian’s many minorities. The Alawites are concentrated in the west near the Mediterranean, the Kurds in the east beside the Euphrates, and the Druze in the south in Jebel ed Druze, so those minorities have territorial bases from which to negotiate their survival no matter who takes power. (In Beirut, just before I crossed the border to Syria, Walid Jumblatt told me he had advised his fellow Druze in Syria to join the rebellion. “They swim in a Sunni sea, not an Alawite sea,” he said, mentioning what happened to those Algerians who sided with the French during the war of independence: many were killed and the rest fled to France.) The Christians, however, are thinly dispersed among Aleppo, Damascus, Wadi Nasara, Qamishli, and other parts of the country. Having witnessed the flight of two million Iraqi Christians to Syria during Shia-Sunni fighting after 2003, they anticipate a similar exodus from Syria if the anti-regime rebellion descends into a tribal war between Alawites and Sunnis that will trap them in the middle. Reluctant to leave their ancestral homeland, which they regard as Christianity’s cradle, they are confronted with demands from both the revolutionaries and the regime to declare themselves. They have resisted as communities so far, although individual Christians are fighting for and against the regime. The Armenian Catholic archbishop of Aleppo, Monsignor Butros Marayati, told me, “We cannot say one side has truth and the other does not, because both sides have faults.” He added that 171 Armenians in Homs have died as members of the security forces or in cross fire, but not as deliberate targets of either side.

Minorities who benefited from the policies of the Alawite minority regime hesitate to turn their backs on it during a time of crisis. Moreover, many Christians view the opposition’s driving force, despite its many secular and liberal adherents, as Sunni fundamentalism battling Alawi upstarts. The fundamentalists, they believe, will deprive them of social freedom in the name of political liberation. An Armenian high school teacher, whom I have known for many years, became uncharacteristically loquacious when explaining her support for the Assad regime:

I’m free. I am safe. … “You’re a kafir [unbeliever]”: I have not heard that phrase for thirty years. At the school, some of my friends are Muslim Brothers. They respect me, and I respect them. Who is responsible for that? … Look at this terror. Is this what Obama wants? Is this what Sarkozy wants? Let them leave us alone. If we don’t like our president, we won’t elect him. This is from a woman who is sixty years old, and I’ve been free for thirty years. I should be afraid to go out? I should cover myself? Women should live like donkeys? … We are citizens. We are equal. Everybody is free with his religion.

She, along with many other Aleppines in the past year, has installed a steel-reinforced front door to her house. This is one sign that the security she and many other Christians felt under Assad père et fils, the regime’s primary justification, is dissipating. Tales of the rape, kidnapping, and murder of Christians in Homs, the city halfway between Aleppo and Damascus that has become this revolution’s Barcelona, have created unease among their coreligionists throughout Syria. In Aleppo, bombs that damaged security force centers took with them nearby Christian apartments, schools, and churches.

Aleppo is tranquil most of the time. There are no soldiers on the streets, and the nightlife that was suspended out of caution in the first months of the rebellion has returned to downtown and the outdoor cafés along Azizieh Square. But, Aleppines of all faiths wonder, for how much longer?

On April 13, Good Friday for the Orthodox churches, I spent the morning walking through the Aleppo Citadel and drinking coffee below its main gate. Families traversed a stone footbridge, supported by seven Roman arches over a dry moat, from a pedestrian plaza at ground level several hundred feet to the Citadel entrance. On the stone walk in front of a row of outdoor cafés, a man in a Nike baseball cap played soccer with his son and daughter, about three and four years old, also in baseball caps. Another little boy with an ice cream cone in one hand chased his father, a tall young man in jeans and tennis shoes. A few families were having breakfast, others coffee and soft drinks. A woman wearing a Superman blue sweater and a matching scarf over her hair promenaded while holding a pink balloon at the end of a bit of string. Beside her were two young women, probably her daughters, in tight slacks, their hair loose on their shoulders. A man pushing a kiosk on bicycle wheels sold cotton candy. The sweet aroma of apple-scented Persian tobacco, smoked through ornate water pipes by women and men, swam though the air. In the dry moat, a half dozen preteens played soccer. Since the conflict began in March 2011, no tourists have checked into the ancient hospital that is now the five-star Carlton Citadel Hotel. Its restaurant terrace, however, filled with Syrians at lunchtime.

In the spring of 1987, also at Eastertime, I made notes in one of these cafés as I was doing twenty-five years later. Thousands of Christians were visiting one another’s churches and exchanging flowers, without provoking so much as an awkward glance from their Muslim neighbors. I was worried about finishing this book, thinking about the next stage of my journey to wartime Lebanon and whether it would be safe in that era of kidnapping foreigners. Syria then seemed solid, unchanged and unchangeable, like the Soviet Union that provided what little international backing it had. The Assad regime had been in place since 1970, the Alawite minority since a coup in 1966, and the Baath Party since 1963. The combined military-party-family structure had survived multiple assaults: the two-year Muslim Brotherhood uprisings in Aleppo and Hama that ended violently in the spring of 1982; Israel’s destruction of its air force and armor that summer in Lebanon; and an attempted putsch by the president’s brother in 1983. Syria’s regime, founded on the primacy of the single party and the army with its intelligence apparatus, resumed control of Lebanon with American approval in 1985, and acquired a Lebanese ally, Hezbollah, whose steady humiliation of the Israeli Army in south Lebanon allowed it to enjoy reflected glory.

For all his political strength and canniness, Hafez al-Assad had a weak heart that made his mortality a source of opportunity for his enemies (Israel Radio announced his death about fifteen years early) and apprehension by his friends. He groomed his toughest, oldest son, as did his fellow dictators in the hereditary republics of Iraq, Egypt, and Libya, to assume power as naturally as the crown princes of Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Oman, and Qatar. That child, Bassel, died in a car crash in 1994, so a younger son, Bashar, was drafted from his London medical studies to assume his brother’s place as heir to the throne. On his father’s death in 2000, Bashar, with his British-born wife at his side, promised reforms that he failed to implement. The Baathist slogan, “Unity, progress, socialism,” still plastered on the Citadel in 1987, was already fading from the assaults of sun and rain. Twenty-five years later, it has disappeared altogether.

Syrians seemed in 1987, if not content, reconciled to a fate that was preferable to the regime of terror they observed in Saddam’s Iraq to their east and the anarchy of Lebanon in the west. (The Lebanese Druze leader, Walid Jumblatt, said of Beirut’s gunmen at the time, “They don’t even obey the law of the jungle.”) The type of dissident intellectuals that Saddam Hussein would torture to death before assassinating their families would in Syria receive a dressing-down from security officials and sometimes a few weeks behind bars to restore them to the path of Baathist righteousness. Torture was reserved for more serious dissidents, the army’s would-be coup-makers and, after 2001, suspected terrorists discreetly transferred to Syrian custody by the CIA. It was cruel; it was efficient; and, until students demonstrated against it in the remote southern border town of Dera’a in March 2011, it was as impregnable as Aleppo’s Citadel.

When Dera’a’s students opened the gate of protest, everyone became a critic of the regime. Even servants of the state complained of corruption among the president’s immediate family and the security services’ use of surveillance, informers, detention and torture to maintain elite privileges. The foreign media officer at the Ministry of Information, an attractive young woman named Abeer Al-Ahmad, surprised me in April 2012 by offering introductions to “opposition leaders.” This would have been unimaginable in 1987, even if they were merely the “official” opponents running in May’s parliamentary elections. The regime allowed the campaign, along with a new constitution and ostensible suspension of the long-standing state of emergency, to meet some of the demands of the real opposition led for the most part by young people in the streets.

The young, born too late to have seen the regime’s suppression of the Muslim Brothers’ rebellions in Aleppo and Hama between 1980 and 1982, came of age during an era of superficial reforms. After Bashar-al-Assad succeeded his father in 2000, government primary and high schools abandoned military-style uniforms for students and granted everyone access to modern telecommunications. (Under his father, even international news agencies had needed government permission to install a fax.) This illusion of liberty seemed to whet an appetite for the substance. Youngsters, who did not share the older generation’s experience of prison and torture, ignored their elders’ caution by calling on other youngsters to join them the streets.

Orwa Nyarabia is a thirty-five-year-old film producer, who among other activities organizes the Damascus Film Festival. He has worked with younger colleagues to organize peaceful demonstrations and street theater to undermine belief in the all-powerful, all-knowing regime. He confesses to embarrassment that he has avoided arrest while all the youngsters in his office have spent short periods in jail. For him, the protests that erupted in Dera’a last year were not surprising. “It’s been cooking for a while,” he told me in the coffee shop of Damascus’s Omayyad Hotel. “In my domain, documentaries, we showed films on dictatorship in Burma and China. The censors passed it, but the audience came out discussing Syria.” When his film festival asked audiences to vote for the best film in 2008, the newspaper headline was, “First Free Vote in Syria.” He said, “The regime blackmailed us with accusations that we were about political provocation. I told them I’m a total liberal businessman.”

Most opponents of the regime, apart from the “official” candidates, dismissed the May elections as irrelevant. Most recall a joke told about the referenda staged every five years by Hafez al-Assad, to endorse his tenure. An official brought him the results: “Mr. President, you have won again with 99.9 percent approval. Only 450 people voted against you.” The president glowered. The official pleaded, “What more could you want?” The president replied, “Their names.”

Nyarabia said that when young people in Dera’a campaigned to ban smoking in public places as far back as 2005, “It was really to have a campaign.” The opposition is finding its way, learning from mistakes and making new ones. It lacks the experience of the regime, as well as the regime’s armory of control. “Two weeks ago, I was talking to the leader of a militia,” Nyarabia, who is half Alawite and half Sunni, said. “There is a danger of becoming sectarian. They are becoming anti-Alawi rather than anti-regime.” The reason for this, he and his friends believed, was that Saudi Arabia provided arms and funds to those closest to its own Wahhabi ideology rather than to liberal democrats. This, combined with threats from Syrian mullahs broadcasting on satellite television from Riyadh, frightens the minorities more than anything else about the opposition.

So far, the regime is holding out. There have been no defections from the regime among its senior members, although this is less an indicator of loyalty than of cold calculation that the opposition is a long way from achieving power. Few soldiers have deserted the army to join the rebels. Some people from Homs told me of their anger at the Free Syrian Army for making their city the crucible of the revolution, then abandoning the populace to its fate when the regime counterattacked.

Like Vichy France, Syria today is divided into supporters of the regime; résistants; and the attentistes, who await the outcome before choosing sides. Most of those I spoke to in all three camps rejected military intervention by the United States, Britain, France and, especially, Turkey, to solve their problems. The Armenian Catholic archbishop, Monsignor Maryati recalled, “Relating to Turkey, many Armenians in Aleppo came from the massacres in Turkey and were forced to leave their country in 1915. They found in Aleppo a secure shelter. They have the rights of any Syrian. They became part of the Syrian identity. They had many martyrs who defended Syria. Psychologically and spiritually, we have some worries—especially intervention by Turkey. We are afraid to be forced into a new emigration.” Even the non-Armenian bishops who spoke to me in Aleppo and Damascus dreaded invasion by the Turkish army. Turkey, they pointed out, does not allow churches to conduct services freely as in Syria and prevented Arabs in Hatay Province, part of Syria until the French gave it to Turkey in 1938, from speaking their language. In Syria, they can speak whatever language they want. In Aleppo, Muslim children are the majority in most Christian-run schools where teaching is in French. As the Armenians fear the Turks, Alawites and Christians fear Sunni Salafists who chant,

Messiahi alla Beirut (Christians to Beirut),

Alawiah alla tabut (Alawis to the coffin).

Syria’s anti-imperial history dates from its violent rejection of the French occupation of Syria from 1920 to 1945, when the French destroyed much of Damascus and other cities to maintain their rule. The near-universal view is that the United States, which until 2004 shipped suspects to Syria for special treatment, objects less to the regime’s repression than to its alliance with Iran. If the United States and Israel are contemplating an attack on Iran’s nuclear facilities, it would make sense to sever the link between Syria and Hezbollah in Lebanon. Some Syrians fear the revolution has become a tool of the United States, Saudi Arabia, and Israel to defeat Iran. That was not why the uprising began nor why so many have become part of it. The perception that outside powers are changing the revolution’s objectives can only rob it of popular support, particularly at a time when the regime has the upper hand militarily and opponents resort to sending car bombs into security buildings and busloads of policemen that kill as many civilians as soldiers.

One Christian said to me in a whisper, “I shit on this revolution, because it is forcing me into the arms of the regime.”

Charles Glass

Dauphin, Alpes-De-Haute-Provence, France

PART ONE (#ua3066dda-5bba-5807-a4ca-2473aaec538d)

CHAPTER ONE (#ua3066dda-5bba-5807-a4ca-2473aaec538d)

THE LEGACY OF ALEXANDER (#ua3066dda-5bba-5807-a4ca-2473aaec538d)

Three dogs pulled and tore the flesh from the corpse. The lamb’s rib-cage was already bare, and still they clawed at the body and snatched lumps of meat with their jaws. They had opened the animal up from its soft stomach, and the wool was stretched aside to expose the food within. The entrails were mostly eaten, but the lamb’s head was untouched. Its eyes were open and blank. The dogs’ paws, their jowls and the hair around their eyes were stained, like the ground, dark red. One dog growled for a moment to warn another not to tread on its portion of the dead prey. Then it silently rejoined the feast, the grim work of devouring what each could of the lamb before they abandoned its carcass to the flies.

The black and white mongrels and the lamb were the only signs of life or death in the barren limestone hills. We were on the highway to Alexandretta, and the driver had stopped the bus and gone into a solitary hut just off the road. No one asked why. This was not, I would learn, unusual. Buses did not keep schedules here, and drivers made their money from more than the transport of passengers. They delivered food and parcels, they carried letters, they smuggled gold, cigarettes, coffee, refugees, drugs and weapons across borders. “A bus like this,” one man explained, “can support a whole family.”

Several passengers including myself had used the unscheduled stop to get out and stretch our legs. The sun was going down. I walked several yards from the bus to be alone. I was watching the dogs when another passenger approached me. “Do you have a degree?” he asked me in English. His accent was slight. He seemed to be in his mid-forties. He wore a grey zip jacket, khaki irousers and old, unpolished shoes. On his lip was a thin moustache.

“I’m sorry … ?” I said.

“A degree in something, from a university?”

“Yes, in philosophy.”

“Falsafi,” he said in Arabic. Then in English, “That’s very good.”

“And you?”

“Mechanical engineering.” “Something practical, not like philosophy ...”

“I have a textile factory in Damascus,” he said. “I’m here to buy materials.”

“Are they better here in Turkey than in Syria?”

“Ha,” he laughed. “You cannot find them in Syria. Anyway, this is Syria.”

“Surie al-Kubra?” Greater Syria, I asked in Arabic.

He laughed again, patting my back. “You speak Arabic?”

“Only a little.”

“Smoke?” He held out an open pack of Marlboro. “You have a family?”

I nodded.

“I have three children,” he said proudly.

The Syrian textile manufacturer had established that, for the duration of the bus journey, we belonged to the same tribe. We were both non-Turks, both had university degrees and both had children. It was bond enough to keep loneliness and the dogs at bay on the dark, perilous road, in a bus crowded with forty strangers, in a land that was not ours. The driver came out of the hut, carrying a small package. We followed him onto the bus. Without discussion, the Syrian took the empty seat next to mine. The bus coughed and bumped its way towards Alexandretta, while the Syrian and I talked into the night.

It was nearly midnight when we reached the edge of Alexandretta, a port town whose form it was impossible to distinguish beyond the glare of the highway and car lights. When we passed a sign which said in Turkish and English, “Iskenderun, pop. 173,700”, I asked the driver to stop. Handing me down my bags and typewriter, the Syrian told me to call him when I reached Damascus. I agreed, knowing it was unlikely. We would not need each other there, where he would be home among his people, where I had friends, where our common levels of education and fatherhood counted for nothing. Alliances here lasted only as long as the need for them, a truth we implicitly shared as he reached his hand out the window to shake mine in farewell. Now alone at the side of the road, I watched the red lights of the bus disappear into the warm Levantine night.

The first strains of the music woke me early. The only sound which should have disturbed the peace of Friday, the Muslim sabbath, was the muezzin’s call to prayer. The sound coming through my window was from a brass band, whose music sounded like a cross between a Handel anthem and a John Philip Sousa march. I went downstairs to the lobby of the Hatayli Oteli and looked out the front door towards the seafront. A parade of what looked like half the population of Alexandretta was marching along the corniche like irregulars at the end of a long campaign. Women carried wreaths and men wore ribbons, and all walked out of step with the triumphal music.

Was this, I wondered, Turkey’s national day? Had democracy been restored? Perhaps war had been declared? I asked the porter what was happening. Discovering we had no common language, I pointed at the parade and tried to look puzzled.

“Polis Bayram,” he said. “Bayram” was Arabic, and apparently also Turkish, for “feast” or “holy day”. “Polis” was Turkish for “police”, and pronounced the same way. I learned later in the day that Turkey was celebrating the anniversary of the founding in 1845 of the Ottoman Police. Everyone in Iskenderun seemed to be wearing a small green and red paper badge, with the Turkish crescent and star in its centre, saying, “10 Nisan Polis Günü”. Despite the obvious enthusiasm of the crowd for the festivities, there was something strange about it. Turkey was the first country I’d known to celebrate the creation of a police force. It seemed to me that the establishment of the police was an admission of failure, an acknowledgement that man was inherently evil and had to be controlled, a cause for regret rather than joy.

No one in the hotel spoke anything other than Turkish, but a young man and young woman behind the reception desk struggled to recall a few words of English. I wanted to telephone the tourist office to see whether I could obtain a car and guide to show me around Alexandretta. I telephoned the number listed in the Fodor Guide, which turned out to be the house of an irate woman speaking only Turkish. The receptionists found another number. It was the tourist office, but the man at the other end spoke no English. The receptionists suggested I walk to the tourist office and assured me someone there would speak English. In a way, they were right.

The hotel porter led me along the wide seafront drive, where drab concrete offices and shops faced the port, to the tourist office on the ground floor of an old building. Inside, a man in a tweed jacket and necktie introduced himself as Mehmet Udimir. He spoke a few, very few, words of English. He said Udimir meant Iron, and made a fist to show it. He was the only person in the tiny, cavern-like room. I explained I needed a guide. He handed me a pamphlet.

Iskenderun is situades atthe foot of the Amanos mountains. It’s about 5 km. wide. The elimate is temperate, and during the winter it is like spring … The raining season is winter. The surrounding mountains are covered with fir forests. Iskenderun is one of the most important port-towns of Turkey. Iskenderun was founded (Alexandrietta) by Alexander the Great after his victory at Issos, The town, in order to distinguish it from Iskendiriye (Alexandria) in Egypt, was given the name of Alexandria Minor in the 17the century …

“No, no,” I said. “Not this sort of guide. I need a man who speaks English, to show me the historic buildings.”

“Okay,” he said, standing up, walking outside and locking the door behind us. I had acquired a guide.

“You see church first,” he said, turning left and leading us away from the seafront into the town. “Church is very old.”

“How old?”

He thought for a minute, but could not give me the date in English. He took a pen and paper out of his pocket and wrote. He handed me the paper. It said, “1901.”

“Very old,” I said.

“Then you see library,” he promised.

“How old is that?”

He wrote again on the paper and handed it to me. “1868.”

We had not reached the relics of Alexander’s invasion, but we were headed, as far as time goes, in the right direction. We walked past the Roman Catholic Church of the Annunciation, but he did not stop there. He merely pointed at it, saying, “Church very old,” and continued across a small, leafy side road to the library. Mehmet Udimir took me into a shaded courtyard behind a stone wall and into a building which looked as though it had once been a large private house on two floors. We walked upstairs, passing reading rooms where schoolchildren were studying. On the walls of each room were portraits – some of them photographs, others prints of oil paintings – of the father of modern Turkey, Moustafa Kemal Atatürk. An Islamic historian in Beirut had once told me, “Atatürk was a man of contradictions, even in his name: Moustafa means ‘chosen one’, Kemal means ‘perfection’, Atatürk means ‘Father of the Turks’. Yet he was neither chosen nor perfect nor even a Turk.”

We walked into an office, and I sat down on one of three wooden chairs facing a large desk. Mehmet sat behind the desk and under another portrait of Atatürk. This painting was almost life-size, in full colour, and showed Atatürk in white tie and tails, his arms casually folded, looking handsome and rather like Noël Coward. His red hair, blue eyes and reddish lips looked anything but Turkish, and it was little wonder his enemies had accused him of having a Greek father and a Jewish mother.

An ancient man, wearing an old, baggy suit, shuffled slowly into the office carrying a tray with glasses of tea on it. His facial features were like a Mongolian’s. He said nothing to either of us, but put the glasses on the desk. It was clear that Mehmet Udimir was not merely the director of tourism in Alexandretta, he was also the chief librarian. I felt as though I’d strayed into one of those small American towns in which the same man, simply by changing hats, served as policeman, judge, fire chief, mayor and coroner. I was certain that if I asked Mehmet to take me to the head of the chamber of commerce, we would walk into another office, where he would sit down behind another desk and another old man would bring us tea. That way, I could confirm the answers to my questions to the tourism director with quotes from the chief librarian and the head of the chamber of commerce. It was an old journalistic trick, but one Mehmet inadvertently prevented me from playing by never telling me anything.

Another old man, better dressed and more distinguished, came into the office. He must have been in his late sixties, and he had a trim moustache. After shaking my hand, he sat down. “I was his teacher,” he said in English, indicating Mehmet. “I am free now.”

“Retired?”

“Yes,” he said. “I come to see Mehmet one day each month.”

Mehmet smiled and appeared to ask him what he had said. They then spoke for a minute in Turkish.

“And you?” the retired teacher asked. “You are tourist?”

“Sort of,” I explained. “I am writing a book.”

“You are going to Antakya?”

“Yes.” Antakya was Turkish and Arabic for Antioch, the city in which the disciples of Christ were first given the name “Christians”.

“In Antakya, you are to look at two places famous, the church and the museum.”

The first old man returned with more tea, served as everywhere else in the Levant hot in clear glasses with no milk and much sugar.

We were talking when a thin young man with black hair, a short black beard and a hawk’s nose, came in and sat down. The retired teacher told me the young man had recently returned to Alexandretta from Istanbul after the death of his father. The father’s restaurant had closed, and he had come to arrange his family’s affairs before returning to Istanbul. The young man, in his mid-twenties, spoke a few words of English, rather like Mehmet. He offered to help me find my way around Alexandretta. His name was Munir. He told me he was half Turkish and half Iranian.

Friends in Beirut and Damascus, I said, had given me the names of people to see in Alexandretta, traders named Makzoumé and Tanzi. Mehmet tried to telephone Tanzi for me, but there was no reply. He could not find a number for Makzoumé, so he asked Munir to take me to the Makzoumé Shipping Company nearby. We finished our tea, and I thanked the director of tourism and chief librarian for his help. He and his former teacher said they would see me again.

It was a short distance to Makzoumé’s offices, back in the direction of the sea. The offices of the Makzoumé Shipping Company were more European than Oriental, with fitted carpets, modern furniture and paintings. There was no old man with tea, but there was an attractive secretary at a desk in an outer office. She showed us into Makzoumé’s inner office, where we sat in silence while he finished making telephone calls. He was an old man, a little overweight and well dressed in woollen trousers and a cardigan. He looked more European than Turkish or Arab, and, as it turned out, behaved more like a European than a Levantine.

While we sat waiting, he spoke on the telephone in Turkish, French and Arabic. When he finished, he asked me why I was there. He was the first person I met in Alexandretta who spoke fluent English. I was hopeful that he could guide me through my first day in his city. I explained that mutual friends, who had been his neighbours when he lived in Beirut, had given me his name as a man who would help me in Alexandretta.

“I don’t think so,” he said. He could do nothing, because he was leaving for Europe the next day. “Perhaps this young man can help you.”

“He is trying,” I said. “But he has been away from here for years, and he does not speak English.”

“I am sorry,” Makzoumé said, the resignation in his voice betraying more relief than regret.

As we left his offices, he called out, “You could try the British Consul.”

Munir and I walked to the Catoni Maritime Agencies, an Ottoman stone building which backed onto the sea and had for years served a secondary purpose as British Consulate in Alexandretta. The front room was a shipping company and travel agency, in which a woman was preparing airline tickets for a customer seated by her desk. I asked where we could find the British Consul.

She indicated a door to another office, and Munir and I went in. The first sights to greet us on entering were three large portraits: in the centre, of course, was Atatürk, to his right was Queen Elizabeth and on his left was Prince Philip, who in Turkey, if nowhere else, was never referred to as “Phil the Greek”. The portraits of the British queen and her husband, bedecked in medals and ribbons, were nearly as dated as that of Atatürk, obviously made many years and many chins ago. Beneath the portraits sat a soberly dressed middle-aged woman, who looked as unassuming as the luminaries behind her were grand. When she saw us, she looked up from her desk with its small British and Turkish flags and smiled. “May I help you?” she asked.

She understood immediately when I explained the purpose of my journey and why I had begun in Alexandretta. She was just old enough to remember that the province had been part of Syria until 1939, although too young to have been born when the whole region was united under the Ottomans. Hind Koba, MBE, had been Her Majesty’s Consul in Alexandretta for nearly thirty years. I told her that I had introductions to only two people in Alexandretta, Makzoumé, who had not been helpful, and Abdallah Tanzi, whose telephone did not answer.

“Abdallah Tanzi,” she said, “is my brother-in-law. We live in the same building.” She thought it would not be difficult to find him. She promised to make appointments with a variety of people who would give me some idea what Alexandretta was like and how its life had changed. Her first call was to a lawyer named Kavak, who said he could see me then.

Walking through the streets, which were becoming more crowded as the morning grew late, Munir used his few words of English, gestures and the gift of an expressive face to tell me that his life was unhappy. He was a Shüte in a Sunni Muslim country. He was half-Iranian in a land which distrusted Iran. His father was dead. He owed taxes on his father’s restaurant, which had closed as a result. He had to care for the rest of his family in Alexandretta, and he yearned for the cosmopolitan life of Istanbul. “Maybe one year,” he said. “Maybe two.” Then he could leave Alexandretta again for the pleasures of the north.

We found Kavak’s office in a modern, if run-down building, up two flights of stairs, past various shops selling women’s clothes and building supplies. A dark-haired man in his mid-thirties opened the door marked “avukat”, introducing himself as Yalçin Kavak. We followed him into a room filled with law books and a large desk covered in papers. There seemed to be no picture of Atatürk, but a small staff displayed a Turkish flag. We had been squeezed into the little office for a few minutes when Kavak invited us to lunch. Munir had to leave for an appointment, but said he would see me later at Mehmet Udimir’s library.

Kavak took me to what was called a “popular” restaurant, the Büyük Ekspres Lokantasi, for “typical” Turkish food. We found ourselves in a large rectangular room, with simple wooden tables and chairs. The walls were bare except for the mandatory portrait of Atatürk. Neither the fan nor the lights overhead were on. We sat at a table near the front window. There was no menu. A waiter asked us what we wanted. When we asked what was available, he told us to come into the kitchen. The kitchen was divided from the dining- room by nothing more than a glass-fronted refrigerator and a food warmer, both chest-high. In the refrigerator were huge chunks of raw meat, lying in trays of blood, chops, beef, spiced minced meat called kofta, all ready for grilling, and salads and cold vegetables. The warmer was full of stews, cooked vegetables, meat pies and dolma, stuffed vegetables like vine leaves and courgettes. Kavak advised me to have a kebab of beef and aubergines, with yogurt, hommous and cold artichokes to begin. The waiter looked pleased with the choice.

The restaurant was filling up with working men, businessmen and a few families with children. The waiter brought me an Efes beer, a Turkish lager apparently from Ephesus, which was cold and tasted good. Between bits of food and drink, we talked about Turkey, religion, politics and the Arab world which Turkey had once ruled and had since forgotten.

“Today in Turkey,” Kavak said, “there are some conservative people who dream of the return of the Ottoman Empire, but the military wants democracy. Meanwhile, Russia is working underground here. It wants to take advantage of Turkey.”

A minute later, he said, “Atatürk was from Thessaloniki. He was very keen on Europe and on democracy. It was very hard for Turks to accept a democratic way of life. Eighty per cent of the people think this country should be European.”

Eating my eastern food, I found it hard to think of this country as a part of Europe. All the food was good, similar in substance to that in the rest of the eastern Mediterranean, but spicier and prepared slightly differently. The hommous, a familiar paste of mashed chick-peas and tahina, was made in a Turkish way, covered not only with olive oil, as in Lebanon and Syria, but with ground red and black pepper, whole green chilli peppers and slices of tomato. As in Syria, we scooped it up with warm, flat bread, but the bread was thicker than Arabic bread and had seeds on top. Delicious as the food was, in Europe it would always be “ethnic”.

Turkey nonetheless had applied to join the European Community. Kavak said the prejudice against Turkish membership was unfair, particularly when it was based on history. “There were problems in 1914. There was persecution of the Armenians and Assyrian Christians, but it is wrong to blame Turkey for the actions of the Ottoman Empire. We do not blame West Germany today for Hitler.”

I asked him about the city. “Iskenderun,” he said, using its proper name in both Turkish and Arabic, “has changed. It was a famous seaport, very deep, for big ships. It is close to Iraq. It has been very important in supplying Iraq in the war against Iran. Many people came from eastern Turkey to settle here. We have the biggest iron and steel factory in Turkey, ISDEMIR.” ISDEMIR was the acronym of the state-owned Iskenderun Demir Celik. “The factory has 16,000 employees and 2,000 managers. This is 18,000 people plus their families. All were brought from outside.”

“Has this shifted the population balance here in favour of Turks?”

“Until 1964, perhaps sixty per cent of the people here were Arabs and forty per cent Turkish. The Arabs were mainly in agriculture and fishing. Today, the population of Iskenderun is approximately 175,000. Twenty-five per cent maximum are Arabs. The other seventy-five per cent are Turkish, with some Kurds.”

“Did they all come here for work?”

“The eastern cities in Turkey do not offer enough. People have to come to the western cities to progress. Even me, I was a lawyer in the east, in Merdin. I was doing well there, but I had to come to Iskenderun.”

“Is there any Syrian influence here?”

“If you study Hatay,” he said, using the Turkish name for the province, “you must look at Syria. In Syria, I think twenty-five per cent of the people are Alawi, forty-five per cent are Sunni and thirty per cent are Christian, including Armenians and Assyrians. The man who became president of Syria is Alawi. He didn’t come to power democratically. He wants to remain president. He puts Alawis in important positions, as military commanders and security police. He is afraid. Of what? Who is against him? The Muslim Brothers, the Iraqi Baath Party. Because of this opposition, twenty-five per cent of the population is not enough for him. This is why, I heard, clever young Alawis from Samandag, in the far south, are being taken to study at the university in Damascus. They study medicine or go into the military and don’t come back.” The Alawis are a dissident sect of Shiite Muslims, who live mainly in the hills along the sea between northern Lebanon and Alexandretta.

Kavak said he had been active in politics. “Before 1980, I belonged to the Social Democratic Party, the democratic left. In Turkey, the Communist Party is forbidden. This is why some people who are not social democrats, but Marxists, work in the Social Democratic Party. They work together and support each other. If you want to succeed, you have to cooperate with the communists. I did not want to. Also, with my work, I don’t have enough time.”

When the waiter brought us the main course, I reflected that Kavak was an unusual man, though just how unusual I had yet to discover. He looked like a conventional lawyer in his dark three-piece suit, his hair combed neatly back, his face shaved. Yet he had mentioned things that were banned in Turkey: 1914, Armenians, Kurds, Alawis who looked to Syria. In official Turkish doctrine, no massacres took place in 1914; there were no Armenians; Kurds were “mountain Turks” Alawis were Turkish without ties to the Arab world. Denial of reality was official policy.

“I was raised a Muslim,” he said, “but I became a Christian in 1970.”

The surprise on my face was difficult to conceal. In all the years I had spent in Muslim countries, I had met only one convert from Islam to Christianity, a professor of philosophy at the American University of Beirut. I had met many converts who had gone the other way, from Christianity to Islam. In Cairo, I knew an American Jew who had become a Muslim. Western Protestant missionaries in 19th-century Syria concluded after many failed attempts that Muslims could not be converted to Christianity, so they concentrated instead on turning eastern Christians, Catholic and Orthodox, into Protestants. Kavak was the first Turkish Muslim I met who had become a Christian. He was not to be the last.

“In 1914,” he recounted, “the grandfather of my father was murdered. It was at the time of the troubles. A Muslim mullah took his son, my grandfather, and raised him as his own son, as a Muslim. Our family were all Muslims. My mother was an Arab Muslim, and we spoke Arabic at home. We read the Koran in Arabic.”

“How did you change?”

“One of my family was a candidate in the elections when I was a teenager. His opponents asked people in Merdin, ‘How can you vote for an Assyrian Christian?’ We did not know what they meant. So, we went to Assyrian villagers, who told us, ‘Your family are Assyrian.’ They told us we were related. Then I learned that my great-grandfather had been killed because he was an Assyrian, when many Assyrians died along with the Armenians.”

“Was that reason enough to become a Christian?”

“When I was at the university, studying law,” he said, “I read the Bible and the Koran. Mohammed was a great leader and a clever man, but I did not find him to be a real prophet. I think maybe some Jewish people helped him, because the Koran is very close to the Old and New Testaments.”

“Is your wife a Christian?”

“She is Turkish from Istanbul,” he said. “I explained my situation to her very clearly before we were married, and she accepted it. She is ready to be baptised, but I want her to study first.”

“Is religion important here?”

“Many educated people here are not Christian, but they are not really Muslim. They don’t go to the mosque and don’t like Islamic life. It is something that exists only on the identity card, Muslim, Christian or Jewish.”

“Identity cards still state your religion? I thought this was a secular state.”

“The Turkish Republic was founded in 1923,” he said. “This is not a long time for a state, especially for a people changing their system from Islamic to secular. But we have come a very long way.”

How far had this corner of Turkey come, separated as it was from the world to which it had belonged for millennia? In 1918, when the Turkish army retreated from Syria north into Anatolia, it abandoned the province of Alexandretta, the harbour at Alexandretta town, the city of Antioch on the banks of the Orontes and the fertile fields, mountains and forests in between, its Arab population and its Armenian and Turkish minorities. For the next twenty years, it was divided from the rest of Turkey, ruled by the French as part of their League of Nations Mandate over Syria. In 1938, France held a referendum on the province’s status and created the so-called Republic of Hatay. A year later, the French gave it back to Turkey. Since then, it has been cut off from the rest of Syria. It seemed doomed in this century, as a frontier province of states to either its north or south, to be separated from at least half its historic self.

In the centre of Alexandretta’s seafront, near the port, lay a large marble plaza. On it a giant black monument, shaped like a wave about to sweep away the town and all its people, appeared to rise out of the Bay of Alexandretta. On its high summit stood two life-size sculpted figures: a woman holding an olive branch and a soldier standing to attention. Between them a large Turkish flag, secular red with the white crescent and star of Islam, fluttered in the breeze. Behind them the wave was about to crest, and below them, on a level fashioned into a smaller wave, stood four larger figures marching in a V-formation behind a man in the centre. On the left were two women, one a peasant and the other a sturdy housewife; on the right were two men, a worker and an engineer. The man and woman near the apex of the V together raised a laurel over the head of the man at the front. He stood on the lowest platform, but was larger than them all. A cape was draped cavalierly over his left shoulder, and his strong right arm was outstretched, pointing landward, as though he were emerging from the surf to redeem Alexandretta.

The heroic figure was Atatürk himself at the scene of his final triumph. His confident gaze was fixed on the last province he reclaimed from the Allies, the final piece of Turkey reassembled from the débâcle of the First World War, which saw the loss of an empire and the birth of a modern state. Like Moses, Atatürk had led his people through the water to the Promised Land, without reaching it himself. Less than a year before the French “Armée du Levant” withdrew on his terms, the “Father of the Turks” had died.

Near the Atatürk monument was a small outdoor café. I stopped there to drink a coffee. A waiter said something to me in Turkish, and I asked whether he spoke Arabic. He did. When he brought me a demi-tasse of Turkish coffee without sugar, he sat down and told me how difficult his life was. He said he worked long hours for little money. He had six children. “If I do not work,” he complained, “there is no bread.” Then he shrugged. “I’m an Arab,” he said, as if this were sufficient to explain his impoverished condition. To him and his compatriots, the Atatürk monument symbolised their defeat, the loss of their place in the Arab world and the severing of ties to their brothers in Syria. It mattered little that they, and not their “liberated” and divided Syrian cousins to the south, were living as all Syrians had lived for four centuries – under Turkish rule.

The beachless seafront was built over a large landfill, a few hundred yards of Turkey taken from the sea. On the wide pavement, it was the time of the afternoon promenade. Men pedalled past on bicycles with their wives on the back. Some had children perched in front. One man swept slowly along with one child on his handlebars and, on the back, a woman holding another child. All along the comiche, families were strolling, stopping to buy peanuts or hot, fresh popcorn from the many street vendors. The young boys’ heads were shaved to stubble. Women walked by in groups, none veiled, though many from the countryside wore brightly coloured scarves.

Turkish sailors, their European navy-style caps emblazoned TCB, joined the march, stealing furtive glances at the girls. Everywhere the sailors meandered, well-armed Military Police followed like vigilant dueñas. The MPs, smartly dressed from their white helmets down to the white spats over their black shoes, wore short truncheons on their hips and carried Belgian FN light automatic rifles. I saw no signs of trouble, and I suspected that, while the MPs were on duty, I wasn’t likely to. A few of the sailors were accompanied by their mothers and fathers, who had come to port to visit them.

I joined the parade of humanity on the seafront – Arab and Turkish townspeople, Alawis from the villages, Kurds from the mountains, Christians and Muslims. Mingling among the crowd, hardly noticeable until they approached you, were young boys and old men trying to make money on the pavements. They stood, dressed in old or badly fitting clothes, pleading with passers-by to give them money. Some merely begged, hands outstretched, with nothing to offer in return other than a blessing. Others shined shoes. Some sat in front of old scales, next to bits of cardboard with a few coins on top, and asked people to weigh themselves in exchange for a small donation. Most of the crowd ignored them, content to enjoy the evening promenade. Everywhere, in cafés and outdoors, in small groups and large, men sat at small tables and played cards or backgammon, all the while drinking tea or coffee, oblivious to the procession passing them by.

The sun was slow to set. The sea, where it met the breakwater, was quiet and unmoving. Nothing had disturbed Alexandretta for fifty years, an unpredicted moment of dull tranquillity in a bloody history of more than two millennia. The Bay of Alexandretta lay at the undefined point where the Aegean gave way to the Mediterranean. It was the northern frontier of the Levant – the 440 miles of coast between here and Al Arish in Gaza. Every port on this eastern Mediterranean shore, and every inland city each port served, had been invaded, besieged and destroyed dozens of times before and after Alexander the Great briefly united them in his empire. How long would this historic moment last? And when would the rest of the Levantine coast to the south, troubled by war and insurrection, enjoy again a generation of evenings like this one in Alexandretta?

CHAPTER TWO (#ulink_8df93697-879c-5fc6-bd4e-dd90853fff7c)

THE ARMY OF THE LEVANT (#ulink_8df93697-879c-5fc6-bd4e-dd90853fff7c)

For most of its life, Alexandretta managed to avoid playing a role in history. In the Levant, this meant it rarely became a battleground. Yet armies often passed through, whether Asians on their way to conquer Europe or Europeans seeking victories in the East. In 333 BC Alexander the Great defeated one of the largest armies ever assembled in antiquity, that of King Darius and his 400,000 Persians, at Issus, about twenty miles north of Alexandretta. After the battle, on an empty piece of shore, Alexander established a port town to control the northern route to Syria and named it for himself.

After Alexander’s death, the heir to his Asian empire, Seleucus, established his capital inland at the other end of a pass through the mountains and named it in honour of his father, Antiochus. Antioch, not Alexandretta, became the centre of Hellenism in Syria and, later, the third greatest city in the Roman Empire. The city declined to a backwater in the Arab and Byzantine Empires, the Crusader Kingdoms and, finally, the Ottoman Empire. Although the Romans had abandoned it even as a port, preferring Seleucia Pieria to the south, it became popular with Venetian and Genoese merchants who established trading houses there for the caravan trade with China, India and Baghdad. The French and British later won concessions from the Ottoman Sultan to do the same. It became a pleasant Mediterranean outpost, only a short sail from Venice, from which to purchase the spices of Asia. The route went from Alexandretta, through the Beilan Pass, to Antioch and Aleppo, where the great caravans across the desert from India had their terminus.

In 1834, Alexandretta missed its chance at greatness. That year, the Duke of Wellington commissioned Colonel F. R. Chesney to establish a route “between the Mediterranean Sea and H.M. possessions in the East Indies by means of steamer communication on the River Euphrates”. The route, for which Parliament voted an initial £20,000, might have become another Suez Canal, which was not constructed until fifty years later. The plan called for an expedition to take two paddle steamers in pieces to the mouth of the River Orontes near Alexandretta. There the steamers, the Tigris and the Euphrates, would be assembled and sail upriver to a point nearest the River Euphrates. They would then be taken apart, carried to the Euphrates and reassembled to sail downstream to Baghdad. Chesney discovered at the beginning that his 20-horsepower engines were not strong enough to sail against the Orontes’ four-knot currents. So, he took the boats apart at the Orontes and carried them the 140 miles to the Euphrates. Although a storm sank the Tigris, the Euphrates steamed into Baghdad just after New Year 1837.

The expedition explored the possibility of cutting a canal between the Euphrates and the sea, but lacked the resources to undertake the digging. It had been difficult enough to hire local labour to carry the ships. Twenty years later, Chesney, by now a Major-General, and a group of businessmen in the City of London obtained permission from the Sultan to construct a railway along the banks of the Euphrates from the Mediterranean to the Persian Gulf. When the British government refused to guarantee Chesney’s “Euphrates Valley Railway Company”, it was disbanded. Had either the canal or the railway been constructed, Alexandretta would have become the first Mediterranean outlet of the swiftest route to the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean, Britain’s lifeline to India. This might have led to a British invasion in the mid-19th century, to protect the route to India, as the British invaded Egypt in 1882 to seize the Suez Canal. Who knows what would have happened in 1956? One thing is certain: France would never have ceded the area to Turkey in 1939, because Britain would not have allowed France to enter in 1920.

When Kaiser Wilhelm II won the concession in 1898 from Sultan Abdul Hamid to build the Berlin–Baghdad Railway, the German engineers planned a branch line to Alexandretta to provide the first rail link between the Mediterranean and the Gulf. Luckily or not for Alexandretta, the branch line was not constructed, and the little town was left to sleep its way into the twentieth century.

Its last flirtation with history came during the First World War, when it almost became the scene of the decisive battle between the Allies and the Ottoman Empire. In 1914, Sherif Hussein of Mecca, whose son Faisal led the Arab Revolt with Lawrence of Arabia, proposed an Allied landing at Alexandretta to cut Turkey from its forces in Iraq and Syria and coincide with an uprising in Syria’s larger cities. Hussein’s plan had the support of the British strategists on the ground, Lord Kitchener, Sir Charles Monro, Sir John Maxwell and Sir Henry McMahon, but it was nonetheless rejected by the General Staff. The British had a commitment to their French allies, who, with no troops available, would not permit an invasion of Syria without them. The Allies decided instead to invade Turkey itself at a place called Gallipoli, a historic disaster which resulted in more Commonwealth dead than any other battle in the East.

The Alexandretta in which I had begun my tour of the Levant was the site of neither a decisive battle nor of a great trade route between West and East. It was merely the northern limit of what geographers, ever scornful of the changing maps of soldiers and politicians, called Syria. To the British, it was valuable, like the rest of the Levant, only as a passage to India. To the French, the Levant had special resonances, as Edward Said wrote in his book Orientalism: “In contrast, the French pilgrim was imbued with a sense of acute loss in the Orient. He came there to a place in which France, unlike Britain, had no sovereign presence. The Mediterranean echoed with the sounds of French defeats, from the Crusades to Napoleon.” For an American traveller like myself, the Levant was filled with reminders of broken promises, beginning with President Woodrow Wilson’s to the people of the Ottoman Empire that they would enjoy the right of self-determination in the post-war settlement. To the people themselves, from Alexandretta to Aqaba, avoiding all our attentions and staying well out of the movement of history was the most they could hope for.

When I awakened on my second morning in Alexandretta, I decided to move. I would continue my wanderings through the town, but stay on a quiet beach forty minutes to the south, near the end of the coast road in the village of Arsuz. The morning was pleasantly cool. There was no wind and not a cloud in the sky. Ships lay at anchor outside the port like ornaments on a cake, apparently frozen into the blue icing. Shopkeepers pulling up steel awnings and opening their doors were bringing the quiet of Saturday morning to an end. Small cafés were serving Turkish coffee and bread to workers, and old women were inspecting vegetables in the street markets.

Before leaving for Arsuz, I went to every bookshop I could find, coming upon them nestled inconspicuously between ironmongers’ and pharmacies. There seemed to be only four or five, and none specialised in books. They sold stationery, postcards, portraits of Atatürk and worry beads, and along one wall in each there were wooden shelves filled with books in no particular order. One shop had books in English, all paperback editions of Dickens, where I bought A Tale of Two Cities. There was a wide range of Turkish works: novels, poetry, engineering textbooks, children’s stories and biographies of Atatürk. There were Turkish translations of foreign writers, men like Jack London and Ernest Hemingway, and women like Ayn Rand, Rosa Luxemburg and Barbara Cartland. There were however no books in Arabic.

“Do you have anything in Arabic?” I asked an attractive young woman who worked behind the cash register in one bookshop. She did not look Turkish, her features more Semitic than Asian. I was speaking to her in Arabic.

“No, we don’t,” she answered in Arabic.

“No books? No newspapers?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

She shrugged her shoulders.

I asked for ink for my pens, and she wrapped a bottle in coloured paper like a gift. As I was leaving, a man who had heard me speaking Arabic invited me to his shop next door for coffee. While we drank coffee, other merchants drifted in and out; they seemed to spend much of their day socialising in one another’s shops. My accent in Arabic, obviously foreign, was basically Lebanese. They found it amusing, just as I found many of their pronunciations and words incomprehensible. Everyone, whether Turkish or Arab, was hospitable – in a way too hospitable. If I had accepted every offer of tea, coffee or lunch at home with a family, I would have had no time for anything else.

In the now crowded streets, many people spoke Arabic among themselves. I could hear mothers speaking it to their children, workers speaking it as they walked together along the cracked pavements. But no road, shop or advertising signs anywhere were written in Arabic. Everything written was in Turkish.

There was something disjointed about life in Alexandretta. Most people seemed to speak one language at home and among friends and another for official purposes. They thought in one language, yet they had to read another. Even the letters of this other language were foreign, since Atatürk had abandoned the “Old Turkish” Arabic script in favour of a modified Latin alphabet. They had one name at home, another on their identity papers and in public. When the names changed to Turkish, the authorities sometimes made arbitrary choices, often based on nicknames or profession. The same thing had happened in America, when new immigrants arriving at Ellis Island were greeted by Irish policemen who could not understand their foreign-sounding names, so simply gave them new, “American” names. When my grandmother arrived as a child from Mount Lebanon in the late 1890s as Nazira Makary, an Irish cop had re-christened her “Vera McCarey”, the name she kept until she married. Her stepfather, Semaan Zalloua, became “Joe Simon”. Under Turkish rule in Alexandretta, Hannoud Alexander was now Hind Koba. I discovered later that Mehmet Udimir had been born Mohamed Haj.

The Ottomans had not tampered with people in this way, leaving Arabs, Armenians, Circassians and countless other subject peoples free to speak and read their own languages, free to use their own names. Yet Turkey had become a “modern” nation, adopting Western nationalist ideology that forbade the old diversity of empire. No one complained in public. A few people, who had steadfastly defended the idea that Turkey was a democracy, begged me not to quote them by name on the subject of language and their sympathy with Syria for fear of arrest or reprisal.

I went back to the Hatayli Oteli to collect my bags. Ahmet the porter called for a taxi, several of which were parked across the road in the shade, to take me to Arsuz. Ahmet asked the driver the fare in Turkish. He then etched the figure 7,000 into the dust on top of the car. I said this was too high. The driver cursed in Arabic, so I began haggling with him in Arabic, dispensing with Ahmet as interpreter. We agreed on 5,000 Turkish Lira for a return journey, to include the wait in Arsuz while I checked in and left my bags. I wanted to be back in Alexandretta for an appointment at the old Church of the Annunciation with the Italian Franciscan priest, Padre Giovanni.

We drove along the coast road out of Alexandretta into green hills with the sea, except for a brief inland stretch, always at our right. The driver said his name was Mehrez, or Mehré in Turkish. When he asked me if I wanted to listen to Turkish music on his cassette player, I asked if he had anything in Arabic.

“Who do you like?”

“Feyrouz,” I said, the name of Lebanon’s most famous chanteuse.

“I don’t have Feyrouz, but I have Samira!” He popped in a tape of songs by Samira Tewfic, a popular Arabic singer who sang, like most Arabic singers, about love. With the music blasting in the old American taxi, we drove at speed along the deserted coast where green hills rolled gently into the blue sea.

Mehrez was curious about me. What was my nationality? Where had I learned Arabic? Where did I live? How many children did I have? What kind of work did I do?

“Sahafi,” I said, the Arabic word for journalist.

He had no idea what the word meant. I tried and failed to explain, but when I fell back on “kutub”, writer, he understood. It turned out we both had five children, two boys and three girls. When I said we lived in London, he seemed puzzled. I explained that my wife was English. He was silent. Minutes passed, and the hills which had until then hugged the coastline gave way to a fertile plain just north of Arsuz. He asked me again about London. “London is near where?”

Did he mean which part of London?

“No.”

Did he know London?

“No.”

“What do you mean?”

“Where is London?” “Fi Ingilterra,” I said. “In England.”

“Fi Ingilterra,” he repeated, knowingly. “Helou.” Helou means “sweet”, but has the connotation “pretty”. Then he said London was “helou”.

I admitted that London and England were “helou,” and after a few minutes we both agreed that Alexandretta too was “helou.”

Mehrez pointed out the sights along the Arsuz road, the onion fields, olive groves and grazing pastures where in summer people from Alexandretta and the villages went for picnics. He offered to stop at several villages where we could drink home-made arak. He seemed disappointed that I had neither the time nor, at eleven in the morning, the desire for a glass of the strong distilled grape with aniseed and asked, “Would you rather have beer?”

We reached the northern outskirts of Arsuz, hideous with new buildings in creative forms of ugliness, as though the houses had been modelled on the Lego designs of a particularly troublesome child. Most of the two-storey structures had just been built or were nearing completion. Trees had yet to be planted, so there was no shade. Concrete dust was everywhere, a side-effect of the Westernising of housebuilding in a land rich with stone and forests which had for centuries until our own provided the materials for beautiful villas, temples and theatres. It was a relief to cross the little bridge at the mouth of the River Arsuz into old Arsuz, with its small cluster of eucalyptus-shaded stone houses. Wooden fishing boats bobbed up and down beneath the bridge, beyond which, almost hidden by pines and eucalyptus, was the Hotel Arsuz.

“Rosuz is the Hellenistik name of this charming little town,” I read in Mehmet Udimir’s tourist brochure. “Coming to Antakya, Selevkos Nicador set foot to shore here. There are some mozaics and the remnants of stone pillars are to be seen in Arsuz, from the middle ages.”

Mehrez drove into the hotel courtyard, where young men were playing soccer. One of them stopped playing and took me inside one of the hotel’s two buildings. He was enormously fat, with a gentle, friendly face, and spoke English well. He told me his father owned the hotel, which had opened in 1965, and that his name was Sedat Mistikoglu. He gave me a room in the newer building, a simple bedroom with windows on two sides, one facing the sea and a sandy beach and the other with a balcony over the courtyard. In the bathroom, there was a shower. I left my bags and went downstairs, where Sedat and his younger brother Suat asked me if everything was all right. They were proud of the hotel’s modern conveniences, the telephones in each room and the new plumbing. “We have just installed solar heating,” Sedat said, beaming.

“What happens when the sun doesn’t shine?” I asked, dreading cold morning showers.

“The sun always shines here,” Sedat assured me.

Back in Alexandretta, I asked Mehrez to take me to the Catholic church. He interpreted this to mean a general tour of Christian churches. He drove to several small churches with tin roofs, first a Greek Orthodox, then an Armenian Orthodox, then a church whose denomination was not indicated. I said I was late for an appointment, that the church I wanted, the “Franciscan” church, was “old and large”. He took me to another Orthodox church, which was tiny with a miniature basilica on top. Finally, despite my limited knowledge of Alexandretta’s roads, I managed to direct him to the Church of the Annunciation. As we approached it, he made a gesture of recognition, as if to ask, “Why didn’t you say this church?”

In search of Padre Giovanni, I went into the rectory, along a corridor hung with old French morality prints. One contrasted the death of the sinner, being subsumed into hell, with that of a faithful man ascending to heaven, all in faded pastel shades. Another showed Adam and Eve in the garden, accepting the apple from the serpent. These were the visions of my own pre-Vatican II childhood, the simple messages of an older church. I heard voices coming from a room which turned out to be a large kitchen. Padre Giovanni was sitting with several other people at a long table eating lunch, but got up and walked with me to the courtyard in front of the church. The church was entirely surrounded by a high wall, leaving large gardens front and back. Both were overgrown and the façades of the church and rectory needed paint, at least, and probably repair. With only about 350 Catholics in all of Alexandretta, the cost of repairs would have been difficult to bear.