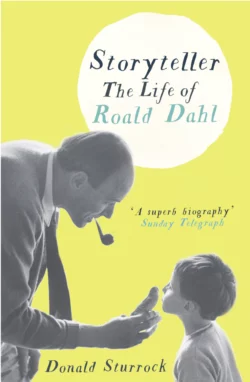

Storyteller: The Life of Roald Dahl

Donald Sturrock

The authorised biography of one of the greatest storytellers of all time, written with complete and exclusive access to the archives stored in the Roald Dahl Museum and Story Centre.Roald Dahl pushed children's literature into new and uncharted territory. More than fifteen years after his death, his popularity around the globe continues to grow, and worldwide sales of his books have now topped 100 million.The man behind the stories, however, remains an enigma. Dahl was a single-minded adventurer, an eternal child, but his public persona was characterised by his blunt opinions on taboo subjects. Described as an anti-Semite, a racist and a misogynist, he felt ignored and undervalued by the literary establishments of London and New York.To his readers, though, Dahl was always a hero, and since his death his reputation has been transformed. His wild imagination is now celebrated, along with his quirky humour and his linguistic elegance. Figures like Willy Wonka, the BFG and the Grand High Witch are nothing less than immortal literary creations, and in a recent poll he beat J. K. Rowling to win the title of Britain's favourite author.In this masterly biography, Donald Sturrock draws on a huge range of source material that has become available since Dahl's death. The result is revealing, compelling and a pure joy to read.

DONALD STURROCK

Storyteller

The Life of Roald Dahl

Copyright (#u146a6ad4-446d-572e-a044-156c49de32a9)

Harper Press

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/)

First published in Great Britain by HarperPress in 2010

This ebook edition first published in 2010

Copyright © Donald Sturrock 2010

Cover photograph © Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images

Some images were unavailable for the electronic edition.

Donald Sturrock asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007254774

Ebook Edition © SEPTEMBER 2010 ISBN: 9780007397068

Version: 2016-10-12

For my parents, Gordon and Margaret

I don’t lie. I merely make the truth a little more interesting …

I don’t break my word—I merely bend it slightly….

ROALD DAHL, from his Ideas Books, No. 1 (c. 1945-48)

Contents

Cover (#u9b0d2f6f-018e-54f5-b57f-d10d118d2009)

Title Page (#u27d41592-508d-5944-bf7c-b9972a98b256)

Copyright

Dedication (#u5cf0f8f8-207a-5657-9f2c-655e0e6f4dff)

PROLOGUE

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

Notes

Bibliography

Index

About the Author

Acknowledgements

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE (#u146a6ad4-446d-572e-a044-156c49de32a9)

Lunch with Igor Stravinsky

ROALD DAHL THOUGHT BIOGRAPHIES were boring. He told me so while munching on a lobster claw. I was twenty-four years old and had been invited for the weekend to the author’s home in rural Buckinghamshire. Dinner was in full swing. A mixture of family and friends were devouring a platter brimming with seafood, while a strange object, made up of intertwined metal links, made its slow way around the table. The links appeared inseparable, but Dahl had told us all they could be separated quite easily by someone with sufficient manual dexterity and spatial awareness. So far none of the guests had been able to solve it. As I waited for the puzzle to come round to me, I tried to respond to Roald’s disdain for biography. I mentioned Lytton Strachey, Victoria Glendin-ning, Michael Holroyd. But he wasn’t having any of it. Sitting in a high armchair, at the head of his long pine dining table, he leaned back, took a swig from his large glass of Burgundy, and returned to his theme with renewed relish. Biographers were tedious fact-collectors, he argued, unimaginative people, whose books were usually as enervating as the lives of their subjects. With a glint in his eye, he told me that many of the most exceptional writers he had encountered in his life had been unexceptional as human beings. Norman Mailer, Evelyn Waugh, Thomas Mann and Dr Seuss were, I recall, each dismissed with a wave of his large hand, as tiresome, vain, dreary or insufferable. He knew I loved music and perhaps that was why he also mentioned Stravinsky. “An authentic genius as a composer,” he declared, throwing back his head with a chuckle, “but otherwise quite ordinary.” He had once had lunch with him, he added, so therefore he spoke from experience. I tried to think of subjects whose lives were as vivid as their art: Mozart, Caravaggio, Van Gogh perhaps? His intense blue eyes looked straight at me. That wasn’t the point, he said. Why on earth would anyone choose to read an assemblage of detail, a catalogue of facts, when there was so much good fiction around as an alternative? Invention, he declared, was always more interesting than reality.

As I sat there, observing the humorous but combative glint in his eye, I sensed that, like a boxer, he was sparring with me. He had thrown a punch and been pleased that I jabbed back. Now he had thrown me another. This one was more difficult to parry. It would be hard to take it further without the exchange becoming detailed and perhaps wearisome. I hesitated. I wondered at his own life. He had just written two volumes of memoirs, one of which he had given to me to read in draft. So I knew the rough outline of his first twenty-five years: Norwegian parents, a childhood in Wales, miserable schooldays, youthful adventures in Newfoundland and Tanganyika, flying as a fighter pilot, a serious plane crash, then a career as a wartime diplomat in Washington. I had already told him privately that I found the books compelling. Did he want me to repeat the compliment over dinner as well? It was hard to tell. At that moment the metal links were presented to me and the conversation moved on. Soon, too, his huge pointy fingers had plucked the puzzle from my inept hands and he had begun confidently to demonstrate its solution. Later on, at the end of a meal which had concluded with the offer of KitKats and Mars Bars dispensed from a small red plastic box, he took his two dogs out into the garden. A few minutes later he returned, wished everyone good night, and retired theatrically from the public space of the drawing room into the privacy of his bedroom.

Half an hour later, I was walking up the frosty path from the main building to the guest house in the garden. The atmosphere was absolutely still. A fox shrieked in the distance. I stopped for a moment and looked up at the clear winter sky. I was struck by how many stars I could see. Great Missenden was less than an hour’s drive from London, but the lights of the city seemed far, far away. Some cows stirred in a nearby field. I looked about me. Gentle hills curved around the garden on all sides. At the top of the lane a vast beechwood glowered. The dark outline of the 500-year-old yew tree that had inspired Fantastic Mr Fox loomed over me. In the orchard, moonlight glinted on the gaily painted gypsy caravan that he had recreated in Danny the Champion of the World. An owl fluttered low into the yew. I turned and opened the door to my room.

Soon, I found myself examining the books in the bookcase by my bedside. There was certainly no biography here. Most of it was crime fiction: Ed McBain, Agatha Christie, Ellery Queen, Dick Francis. As I pulled out a volume, I noticed some ghost stories too, an insect encyclopedia, the diary of a Victorian priest, and a book of poetry by D. H. Lawrence. All of the books looked as if they had been read. I reflected again on our exchange over dinner, and wondered whether Roald had actually met Stravinsky. Perhaps he had simply made that remark to disconcert me? Before I switched off the light, I remember thinking that next day I would flush him out. I would ask him how he had come to have lunch with the great composer. Needless to say, I got distracted and forgot to do so.

It was then February 1986. I had known Dahl six months. The previous autumn, as a fledgling documentary director in the BBC’s Music and Arts Department, I had proposed making a film about him for Bookmark, the corporation’s flagship literary programme. Nigel Williams, the producer, himself an established playwright and novelist, had decided that the Christmas edition of the show would be devoted to children’s literature. Twenty-five years ago this was still a field that many people in the UK arts affected to despise, and for once none of the programme’s older, more experienced directors seemed keen to put forward any ideas. I was the most junior on the team. I wanted desperately to make a film. Any film. So I took my chance. It was an obvious suggestion — a portrait of the most famous and successful living children’s writer. The motivation however behind my plan was largely opportunistic. At that point, I had read none of Dahl’s children’s fiction other than Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. On the other hand, as a thirteen-year-old, I had read most of his adult short stories, feasting on them with concentrated relish from behind a school desk during maths lessons. My adolescent mind had revelled in their grotesqueries, their complex twists and turns, and their spare, elegant, strangely sexy prose.

I remember Nigel Williams’s smile. How he looked at me when I mentioned Roald Dahl. It was knowing, almost wicked. “Okay,” he said. “If you can persuade him to do it.” I paused. Was he thinking about money? The programme had a tiny budget and always paid its contributors the most modest of disturbance fees. It wasn’t cash, however, that was on Nigel’s mind. “You know his reputation?” he asked rhetorically. “Unbelievably grumpy and difficult. He’ll never agree to take part.” I nodded, although this was actually news to me, for my impression of Dahl the man at that point was in fact one of singular lightness. Four years earlier, while I was an undergraduate, he had taken part in a debate at the Oxford Union. “Romance is bunk” was the motion. Dahl had contributed to it memorably, arguing that romance was no more than a euphemism for the human sex drive. He was a great entertainer — witty, subversive, and often risque. At one point he challenged a young woman in his audience to try and “get romantic” with a eunuch. At another he joked that a castrated male was similar to an aeroplane with no engine, because neither could get up. As I walked out of Nigel’s office, all this was still fresh in my memory. Maybe Dahl will be cantankerous, I thought, but I am sure he will be funny, too. I discovered from press cuttings that he lived in a village called Great Missenden. I searched a telephone directory for Dahl, R. and there was his phone number. Ten minutes later I was calling him to discuss the project. Our conversation was brief and to the point. “Come to lunch,” he said. “There are good train services from Marylebone.”

A week later, I was standing outside the bright yellow front door of Gipsy House, his modest eighteenth-century whitewashed home. I rang the bell. An explosion of dogs barking heralded the arrival of a gigantic figure in a long red cardigan. He looked down at me. He was six foot five inches tall, craggy and broad of beam. His body seemed larger than the doorway and far, far too big for the proportions of the cottage. He ushered me through into a cosy sitting room where a log fire burned generously in the fireplace. He seemed a trifle surprised. I asked if I had got the date wrong. “No,” he said. “I was expecting you.” He asked me to wait a moment, then left the room. His strides were huge and ponderous, but strangely graceful — a bit like a giraffe. On one wall a triptych of distorted Francis Bacon heads glared out at me alarmingly, reminding me that for years, Dahl’s adult publishers had dubbed him “the Master of the Macabre”. On an adjacent wall, another Bacon head — this one a distorted swirl of green and white — returned my gaze. Around them a dazzlingly eclectic group of paintings and artefacts decorated the room: colourful oils, a collection of outsize antique Norwegian pipes, a primitive mask, a sober Dutch landscape and some stylized geometric paintings. I learned over lunch that these were the works of the Russian Suprematists: Popova, Malevich and Goncharova.

His wife Liccy (pronounced “Lici” as in the middle two syllables of her name, Felicity) returned five minutes later and suggested I go through into the dining room, where he was waiting for me. Over a lunch of smoked oysters, served from a tin — I don’t recall any wine — we discussed the documentary. In the week leading up to our meeting I felt I had become an expert on his work and had read everything of his that I could get my hands on. I asked him some questions about his early life and about childhood. He told me how easy he found it to see the world from a child’s perspective and how he thought that this was perhaps the secret to writing successfully for children. His memoir of childhood, Boy, had recently been published. I wanted to use this as the backbone of the film and so we talked about Repton, the school where he had spent his teenage years, fifty years earlier. He told me what a miserable time he had had there and we talked about the ethics of beating, for which the school was famous. We pencilled some provisional shooting dates in his diary. Then I asked whether I could see his writing hut. I had read about it and wanted to film there. I anticipated he might say no and tell me that it was too private a place to show to a film crew. But he did not bat an eyelid, and, after lunch, he took me to see it. We walked down a stone path bordered with leafless lime saplings, tied onto a bamboo framework that arched gently over our heads. He explained to me that in time the saplings would grow around the structure and make a magical, shady tunnel.

He opened the door to the hut and I went inside. An anteroom, stuffed with old picture frames and filing cabinets, led directly into his writing space. The walls were lined with aged polystyrene foam blocks for insulation. Everything was yellow with nicotine and reeked of tobacco. A carpet of dust, pencil sharpenings and cigarette ash covered the worn linoleum floor. A plastic curtain hung limply over a tiny window. There was almost no natural light. A great armchair filled the tiny room — Dahl frequently compared the experience of sitting there to being inside the womb or the cockpit of a Hurricane. He had chopped a huge chunk out of the back of the chair, he told me, so nothing would press onto the lower part of his spine and aggravate the injury he suffered when his plane crashed during the war. A battered anglepoise lamp, like a praying mantis, crouched over the chair, an ancient golf ball dangling from its chipped arm. A single-bar electric heater, its flex trailing down to a socket near the floor, hung from the ceiling. He told me that by poking it with an old golf club he could direct heat onto his hands when it was cold.

Everything seemed ramshackle and makeshift. Much of it seemed rather dangerous. Its charm, however, was irresistible. An enormous child was showing me his treasures: the green baize writing board he’d designed himself, the filthy sleeping bag that kept his legs warm, and — most prized of all — his cabinet of curiosities. These were gathered on a wooden table beside his armchair and included the head of one of his femurs (which had been sawn off during a hip replacement operation twenty years earlier), a glass vial filled with pink alcohol, in which some stringy glutinous bits of his spine were floating, a piece of rock that had been split in half to reveal a cluster of purple crystals nestling within, a tiny model aeroplane, some fragments of Babylonian pottery and a metal ball made, so he assured me, from the wrappers of hundreds of chocolate bars. Finally, he pointed out a gleaming steel prosthesis. It had been temporarily fitted into his pelvis during an unsuccessful hip replacement operation. He was now using it as an improvised handle for a drawer on one of his broken-down filing cabinets.

The shooting went without incident. Though it was the first time he had ever been filmed in his writing hut, and indeed the first time that the BBC had made a documentary about him, there were no rows, no difficulties, and no grumpiness. Roald charmed everyone and I occasionally wondered how he had come to acquire his reputation for being irascible. His short fuse had not been apparent to me at all. Years later, however, I discovered that I just missed seeing it on my very first visit. Not long after he died, Liccy explained why I had been abandoned in his drawing room. For, standing in his doorstep, I had not made a good impression. Roald had gone straight to her study. “Oh Christ, Lic, they’ve sent a fucking child,” he had groaned. Liccy encouraged him to give me a chance and I think my youth and earnestness eventually became an asset. I even felt at the end of the two-day shoot as if Roald had become a friend. In the editing room, putting the documentary together, I was reminded of the suspicion that still surrounded Dahl in literary circles. Nigel Williams, concerned that Dahl appeared too sympathetic, insisted that I shoot an interview with a literary critic who was known to be hostile to his children’s fiction. This reaction may have been largely a result of a trenchantly anti-Israeli piece Dahl had written for The Literary Review two years earlier. The article had caused a great deal of controversy and fixed him as an anti-Semite in many people’s minds. But there was, I felt, something more than this in the atmosphere of wariness and distrust that seemed to surround people’s reactions to him. Something I could not quite put my finger on. A sense perhaps that he was an outsider: misunderstood, rejected, almost a pariah.

I must have visited Gipsy House six or seven times in the next four years. Gradually, I came to know his children: Tessa, Theo, Ophelia and Lucy. Many memories of those visits linger still in the brain. Roald’s excited voice on the telephone early one morning: “I don’t know what you’re doing next Saturday, but whatever it is, you’d better drop it. The meal we’re planning will be amazing. If you don’t come, you’ll regret it.” The surprise that evening was caviar, something he knew I had never tasted. True to the spirit of the poacher at his heart, he later explained that it had been obtained, at a bargain price, in a furtive transaction that seemed like a cross between a John Le Carre spy novel and a Carry On film. The code phrase was: “Are you Sarah with the big tits?” Another evening, I remember him opening several of the hundreds of cases of 1982 Bordeaux he had recently purchased and that were piled up everywhere in his cellar. The wines were not supposed to be ready to drink until the 1990s, but he paid no attention. “Bugger that,” he declared. “If they’re going to be good in the 1990s, they’ll be good now.” They were. I recall his entrances into the drawing room before dinner, always theatrical, always conversation-stopping, and his loud, infectious laugh. Being in his company was always invigorating. You never quite knew what was going to happen next. And whatever he did seemed to provoke a story. Once, on a summer’s morning outside on the terrace, he taught me how to shuck my first oyster, using his father’s wooden pocketknife. He told me he had carried it around the world with him since his schooldays. Years later, when I told Ophelia that story, she roared with laughter. “Dad was having you on,” she explained. “It was just an old knife he had pulled out of the kitchen.”

Roald’s physical presence was initially intimidating, but when you were on your own with him, he became the most compelling of talkers. His quiet voice purred, his blue eyes flashed, his long fingers twitched with delight as he embarked on a story, explored a puzzle, or simply recounted an observation that had intrigued him. It was no surprise that children found him mesmerizing. He loved to talk. But he could listen, too — if he thought he had something to learn. We often discussed music. He preferred gramophone records and CDs to live performances — his long legs and many spinal operations had made sitting in any sort of concert hall impossibly uncomfortable — and he enjoyed comparing different interpretations of favourite pieces, seeming curiously ill at ease with relative strengths and merits. A particular recording always had to come out top. There had to be a winner. This attitude informed almost every aspect of life. Whether it was food, wine, painting, literature or music, “the best” interested him profoundly. He liked certainty and clear, strong opinions. I don’t think I ever heard him say anything halfhearted. And despite a life that had been packed with incident, he lived very much in the present and seldom reminisced. I recall only one brief conversation about being a fighter pilot and none at all about dabbling in espionage, or mixing with wartime Hollywood celebrities, Washington politicos and New York literati.

Occasionally he name-dropped. I recall him telling me, for no particular reason, that one well-known actor had been a bad loser when Roald beat him at golf. And then, of course, there was that improbable lunch with Stravinsky. But, though he was clearly drawn both to luxury and to celebrity, he took as much pleasure in a bird’s nest discovered in a hedge as he did in a bottle of Chateau Lafleur 1982 or the bon mots of Ian Fleming and Dorothy Parker. He delighted in ignoring many of the usual English social boundaries and asking people personal questions. He did it, I suspect, not because he was interested in their answer, but because he revelled in the consternation he might provoke. In that sense he could be cruel. Yet, though his fuse was a famously short one, I actually saw him explode only once. He was on the telephone to the curator of a Francis Bacon exhibition in New York, who wanted to borrow one of his paintings and had called while he had guests for dinner. She said something that annoyed him, so he swore at her furiously and slammed the phone down. I recall feeling that the gesture was self-conscious. He was playing to an audience. His temper subsided almost as soon as the receiver was back in its cradle.

Even then, I was dimly aware that this showy bravado was a veneer, a carapace, a suit of armour created to protect the man within: a man who was infirm and clearly vulnerable. Several dinner invitations were cancelled at short notice because he was unwell. Once, Liccy told me on the phone that the “old boy” had nearly met his maker. Yet he always rallied, and the next time I saw him, he would look as robust and healthy as he had been before. Always smoking, always drinking, always controversial, he appeared a life force that would never be extinguished. So his death, in November 1990, came as a shock. At his funeral, a tearful Liccy, who knew my passion for classical music, asked if I would help her commission some new orchestral settings of some of Roald’s writings and thereby achieve something he had wanted: an alternative to Prokofiev’s Peter andthe Wolf that might help attract children into the concert hall. I had just left the BBC to go freelance and jumped at the opportunity. Over the next few years, I encountered Roald’s sisters, Alfhild, Else and Asta, as well as his first wife, Patricia Neal. They all took part in another longer film I made about Dahl in 1998, also for the BBC, which Ophelia presented, and in which she and I explored together some of the themes of this book for the first time. Many of the interviews with members of his family quoted in this book date back to this period.

Shortly before he died, Roald nominated Ophelia as his chosen biographer. In the event that she did not want to perform this task, he also made her responsible for selecting a biographer. This came as something of a shock to her elder sister Tessa, who had hoped that she would be asked to write the book. Nevertheless, it was Ophelia who took up the challenge of sifting through the vast archive of letters, manuscript drafts, notebooks, newspaper cuttings and photographs her father had left behind him in his writing hut. Living in Boston, however, where she was immensely busy with her job as president and executive director of Partners in Health, the Third World medical charity she had co-founded in 1987, made the research time-consuming, and she found it increasingly hard to find time to complete the book. Eventually, when she got pregnant in 2006, she decided to put her manuscript on the shelf and asked me whether I would like to try and take up the challenge of writing her father’s biography. It was a tremendous leap of trust on her part to approach me — a first-time biographer — to write it. She did so, she told me, because I was outside the family, yet also because I had known her father and liked him. She felt that someone who had not met him would find it almost impossible to put together all the disparate pieces of the jigsaw puzzle that made up his complex and extravagant personality. Everything in the archive — now housed in the Roald Dahl Museum and Story Centre at Great Missenden, which had opened the previous year — was placed at my disposal. With characteristic generosity, Ophelia even allowed me to draw on the manuscript of her own memoir. Tessa too, despite an initial wariness, has subsequently freely given me her time and energies. I could not possibly have written the book without their cooperation as well as that of their siblings Theo and Lucy. I am profoundly grateful to all of them.

There were many surprises and puzzles in store for me on the journey — not least the discovery of how many contradictions animated his personality. The wild fantasist vied with the cool observer, the vainglorious boaster with the reclusive orchid breeder, the brash public schoolboy with the vulnerable foreigner, who never quite fit into the English establishment although he liked to describe himself as “very English … very English indeed”.

A delight in simple pleasures — gardening, bird-watching, playing snooker and golf — counterbalanced a fascination for the sophisticated environment of grand hotels, wealthy resorts and elegant casinos. His taste in paintings, furniture, books and music was refined and subtle, yet he was also profoundly anti-intellectual. He could be a bully, yet prided himself on defending the underdog. For one who always relished a viewpoint that was clear-cut, these incongruities were not entirely unexpected. With Roald there were seldom shades of grey. I was also to learn that, as he rewrote his manuscripts, so too he rewrote his own history, preferring only to reveal his private life when it was quasi-fictionalized and therefore something over which he could exert a degree of control. Many things about his past made him feel uncomfortable and storytelling gave him power over that vulnerability.

So now, in 2010, a wheel has come full circle. Little did I imagine when Roald and I had that conversation over dinner in 1986 that, twenty-four years later, I would finally answer his challenge by writing this book. It is an irony that I hope he would have appreciated. For seldom can a biographer have been presented with such an entertaining and absorbing subject, the narrative of whose picaresque life jumps from crisis to triumph, and from tragedy to humour with such restless swagger and irrepressible brio. Presented with so much new material — including hundreds of manuscripts and thousands of letters — I have tried, everywhere possible, to keep Dahl’s own voice to the fore, and to allow the reader to encounter him as I did, “warts and all”. Sometimes I have wished that I could convey the chuckle in his voice or seen the twinkle in his eye that doubtless accompanied many of his more outrageous statements.

Moreover, his tendencies to exaggeration, irony, self-righteousness, and self-dramatization made him a particularly slippery quarry, and my attempts to pick through the thick protective skein of fiction that he habitually wove across his past may not always have been entirely successful. I have tried to be diligent and a good fact-checker, but if a few misjudgements and errors have crept in, I hope the reader will pardon them. I make no claim to be either encyclopedic or impartial. I am not sure either is even possible. Nevertheless, I have tried to write an account that is accurate and balanced, but not bogged down in minutiae. That is something I know Roald would have found unforgivable. So, while I remain uncertain if he ever had lunch with Igor Stravinsky, I have to confess that now I no longer care. It was perhaps a STORYTELLER’s detail, a trifle. Compared with so much else, whether it was true or false seems ultimately of little importance.

CHAPTER ONE (#u146a6ad4-446d-572e-a044-156c49de32a9)

The Outsider

IN JULY 1822, The Gentleman’s Magazine of Parliament Street, Westminster, reported a terrible accident. Its correspondent described how a few weeks earlier, in the tiny Norwegian hamlet of Grue, close to the border with Sweden, the local church had burned down. It was Whit Sunday and the building was packed with worshippers. As the young pastor warmed to the themes of his Pentecostal sermon, the aged sexton, tucked away in an unseen corner under the gallery, had felt his eyelids becoming heavy. By his side, in a shallow grate, glowed the fire he used for lighting the church candles. Gently its warmth spread over him and very soon he was fast asleep. Before long, a smell of burning was drifting through the airless building. The congregation stirred, but obediently remained seated as the priest continued to explain why the Holy Spirit had appeared to Christ’s apostles as countless tongues of fire. The smell got stronger. Smoke started to drift into one of the aisles. The sexton meanwhile snoozed on oblivious. By the time he awoke, an entire wall of the ancient church was ablaze. He ran out into the congregation, shouting at the worshippers to save themselves. Suffocating in the thick smoke, they pressed against the church’s sturdy wooden doors in a desperate attempt to escape the flames. But the doors opened inwards and the pressure of the terrified crowd simply forced them ever more tightly shut. Within ten minutes, the entire church, which was constructed almost entirely out of wood and pine tar, became an inferno. That day over one hundred people met, as the magazine described it, “a most melancholy end”, burning to death in what is still the most catastrophic fire in Norwegian history.

Only a few people survived. They did so by following the example of their preacher. For Pastor Iver Hesselberg did not join the rush toward the closed church doors. Instead, he jumped swiftly down from his pulpit and, with great practical purpose, began piling up Bibles under one of the high windows by the altar. Then, after scrambling up them to the relative security of the window ledge, he hurled himself through the leaded glass and out of the burning edifice to safety. Some might have called his actions selfish, but all over Europe newspapers praised the cool logic of the enterprising priest, who thought his way out of a crisis and did not succumb to the group stampede. Here was a man of his time, they wrote, a thinker: an individual who stood outside his flock. Grateful for his second chance in life, Pastor Hesselberg evolved into a philanthropist and public figure. A contemporary remembered him as “a strict man who preached fine sermons”, a staunch Lutheran who was also a liberal idealist, visiting the poor and teaching them arithmetic, as well as how to read and write. He even founded a parish library.

Hesselberg ended his days as a distinguished theologian and eventually a member of the Norwegian parliament, where he helped to ensure that all public buildings in Norway would in future be built with doors that opened outwards. His son, Hans Theodor, attempted to follow in his footsteps. He trained for the priesthood and married into one of Norway’s most distinguished families. His wife was a descendant of Peter Wessel, a Norwegian naval hero, who had been killed in a duel in 1720.

They settled at Vaernes,* (#ulink_5557ab62-58d3-5fe3-aa1c-58e1c4f20700) a large farm not far from Trondheim, the ancient capital of Norway, whose magnificent Romanesque cathedral, built on the shrine of Norway’s patron saint, St Olave, almost a millennium ago, evokes a virtually forgotten age when Scandinavia was a key spiritual centre of Christian Europe.

In Vaernes, Hans Theodor raised eleven children, but he lacked his father’s shrewd judgement and talent for hard work. He drank excessively, managed his estates incompetently, and never practised as a priest. He was also an incorrigible — and unsuccessful — gambler. Bit by bit, he was forced to sell off his lands to pay his gaming debts. One evening he went too far. He staked the village storehouse in a game of cards and lost. Outraged at this disregard for his responsibilities to his flock, the local community forced him to sell what remained of the farm. Hans Theodor moved to Trondheim, where he died a pauper in 1898.

But his children went out into the world and prospered — many entering the burgeoning Norwegian middle classes. Two became merchants, one became an apothecary, another a meteorologist. Yet another, Karl Laurits, trained as a scientist, then studied law and eventually went to work in Christiania, now Oslo, as an administrator in the Norwegian Public Service Pension Fund. In 1884 he married Ellen Wallace, and the following year, his first daughter, Sofie Magdalene, was born in Kristiania.† (#ulink_01bea79e-0ed3-5e30-9e8e-ca6778521fc2) Thirty-one years later, on a crisp autumn day in South Wales, she would give birth to her only son, Roald.

Roald Dahl himself was not that interested in his ancestry or in historical detail. Though proud of his Norwegian roots, archives and public records were not his domain, and when, in his late sixties, he wrote his own two volumes of memoirs, Boy and Going Solo, he seems to have known nothing of his great-great-grandfather Hesselberg’s extraordinary escape from the church fire or of the streak of reckless gambling and alcohol addiction that had emerged in his descendants.

Yet Pastor Hessel-berg’s story would almost certainly have fascinated Roald. He would have admired his ancestor’s resourceful ingenuity, as well as his ability to think both laterally and practically in the face of a crisis. These were qualities he admired in others and they were attributes he gave to the heroes and heroines of many of his children’s books. In his own life, too, Dahl would face many moments of crisis and struggle, and seldom were his resources of tenacity or inventiveness found wanting. His psychology and philosophy was always positive. “Get on with it,” was one of his favourite phrases, recommended to family, friends and colleagues alike, and one that he put into practice many times in his life when dealing with adversity — whether that was accident, war, injury, illness, depression or death. Like Pastor Hesselberg, he seldom looked behind him. He infinitely preferred to look forward.

Yet this was only one side of the man. His daughter Ophelia once described her father to me as “a pessimist by nature”,

and a depressive streak ran through both sides of his family. Many of his adult stories revealed a jaundiced and sometimes bleak view of human behaviour, which drew repeatedly on man’s capacity for cruelty and insensitivity. His children’s writing is sunnier, more positive — though even there, early critics complained of tastelessness and brutality.

It was a charge against which he always energetically defended himself, for underneath the exterior of the humourist and entertainer lurked a fierce moralist. But he found it hard because, like many writers, he hated analysing his own writing. I remember asking him on camera why so many of the central characters in his children’s stories had lost one or both parents. He was taken aback by the question and at first even denied that this was the case. However, when, on reflection, he realized that he had made a mistake, his brain searched swiftly for a way out. He compared himself to Dickens. He had used “a trick”, he said, “to get the reader’s sympathy”. In a rare confession of error, he admitted with a smile that he “had been caught out a bit”.

What struck me most profoundly was that he seemed to make no conscious connection between his own life — he had lost his own father when he was three years old — and the worlds he created in his stories. It suggested, I thought, a kind of unexpected innocence and naivety.

Dahl’s writing career would take many twists and turns over the course of his seventy-four years, and these convolutions were intimately bound up with a complex private life that held many hidden corners, secrets and anxieties. Together they made a powerful cocktail — for Dahl was full of contradictions and paradoxes. He loved the privacy of his writing hut, yet he liked to be in the public eye. He described himself as a family man, living in a modest English village, yet he was married to an Oscar-winning movie star, and kept the company of presidents and politicians, diplomats and spies. He was fascinated by wealth and glamour. He often bragged. He gambled. He had a quick and discerning eye for great art and craftsmanship. He was drawn to the good things in life. Yet he was also a simple man, who preferred the Buckinghamshire countryside to life in the city — a man who grew fruit, vegetables and orchids with obsessive passion, who surrounded himself with animals, who bred and raced greyhounds, and who kept the company of tradesmen and artisans. He was generous, although his kindness was usually quiet and low key. Often only the recipient was aware of it. Roald himself however was no shrinking violet. He enjoyed public appearances, and delighted in being controversial. He was a conundrum. An egotistical self-publicist — notoriously brash, even oafish, in the limelight — he could also behave as slyly as the foxes he so admired. If he wanted, he could cover his tracks and go to ground.

As a writer, he was the most unreliable of witnesses — particularly when he spoke or wrote about himself. In Boy, his own evocative and zestful memoir of childhood, he begins by disparaging most autobiography as “full of all sorts of boring details.”

His book, he asserts, will be no history, but a series of memorable impressions, simply skimmed off the top of his consciousness and set down on paper. These vignettes of childhood are painted in bold colours and leap vividly off the page. They are infused with detail that is often touching, and always devoid of sentiment. Each adventure or escapade is retold with the intimate spirit of one child telling another a story in the playground. The language is simple and elegant. Humour is to the fore. Self-pity is entirely absent. “Some [incidents] are funny. Some are painful. Some are unpleasant,” he declares of his memories, concluding theatrically: “All are true.” In fact, almost all are, to some extent, fiction. The semblance of veracity is achieved by Dahl’s acute observational eye, which adds authenticity to the most fantastical of tales, and by a remarkable trove of 906 letters he kept at his side as he wrote. These were letters he had written to his mother throughout his life, and which she hoarded carefully, preserving them through the storms of war and countless changes of address.

In these miniature canvases, Dahl began to hone his idiosyncratic talent for interweaving truth and fiction. It would be pedantic to list the inaccuracies in Boy or its successor Going Solo. Most of them are unimportant. A grandfather confused with a great-grandfather, a date exaggerated, a slip in chronology, countless invented details. Boy is a classic, not because it is based on fact but because Dahl had a genius for storytelling. Yet its untruths, omissions and evasions are revealing. Not only do they disclose the author’s need to embellish, they hint as well at the complex hidden roots of his imagination, which lay tangled in a soil composed of lost fathers, uncertain friendships, a need to explore frontiers, an essentially misanthropic view of humanity, and a sense of fantasy that stemmed in large part from the Norwegian blood that ran powerfully through his veins.

Norway was always important to Dahl. Though he would sometimes surprise guests at dinner by maintaining garrulously that all Norwegians were boring, he never lost his profound affection for and bond with his homeland. His mother lived in Great Britain for over fifty years, yet never renounced her Norwegian nationality, even though it sometimes caused her inconvenience — most notably when she had to live as an alien in the United Kingdom during two world wars. Although she usually spoke to her children in English and always wrote to them in her adopted language, she made sure they also learned to speak Norwegian at the same time they were learning English; and every summer she took them to Norway on holiday. Forty years later, Roald would recreate these summer holidays for his own children, reliving memories that he would later immortalize in Boy. “Totally idyllic,” was how he described these vacations. “The mere mention of them used to send shivers of joy rippling all over my skin.”

Part of the pleasure was, of course, an escape from the rigors of an English boarding school, but for Roald the delight was also more profound. “We all spoke Norwegian and all our relations lived over there,” he wrote in Boy. “So, in a way, going to Norway every summer was like going home.”

“Home” would always be a complex idea for him. His heart may have sometimes felt it was in Norway, but the home he dreamed about most of the time was an English one. During the Second World War, when he was in Africa and the Middle East as a pilot and in Washington as a diplomat, it was not Norway he craved for, nor the valleys of Wales he had loved as a child, but the fields of rural England. There, deep in the heart of the Buckinghamshire countryside, he, his mother and his three sisters would later construct for themselves a kind of rural enclave: the “Valley of the Dahls”, as Roald’s daughter Tessa once described it. Purchasing homes no more than a few miles away from each other, the family lived, according to one of Roald’s nieces, “unintegrated … and largely without proper English friends”.

For though Dahl was proud to be British and though he craved recognition and acceptance from English society, for most of his life he preferred to live outside its boundaries, making his own rules and his own judgements, not unlike his ancestor, Pastor Hesselberg.

As a result, English people found him odd. His best friend at prep school admitted that he was drawn to Roald because he was “a foreigner”.

And he was. Though born in Britain, and a British citizen, in many ways Dahl retained the psychology of an emigre. Later in his life, people forgot that. They interpreted his behaviour through the false perspective of an assumed “Englishness”, to which he perhaps aspired, but which was never naturally his. They saw only a veneer and they misunderstood it. In truth, Roald was always an outsider, the child of Norwegian immigrants, whose native land would become for their son an imaginative refuge, a secret world he could always call his own.

As with many children of emigrants, Roald would take on the manners and identity of his adopted home with the zeal of a convert. His sister Alfhild complained that her brother did not “recognize more how strong the Scandinavian is in us as a family”.

Ironically, however, the one British ancestor he did publicly acknowledge was the Scots patriot William Wallace. Dahl was immensely proud of the family tree that showed his direct lineage to the rebel leader who, legend has it, also stood over six foot five inches tall. Wallace had defeated the invading English armies at the Battle of Stirling Bridge in 1297, but he was to meet a grisly end at their hands eight years later, when he was captured, taken to London, and executed. The brutal details of his death would not have eluded Dahl’s antennae, which were acutely sensitive to human cruelty. Wallace was stripped naked, tied to a horse and dragged to Smithfield, where he was hanged, cut down while still alive, then publicly castrated and disembowelled. His body was hacked into four parts and his head placed as a warning on a spike atop London Bridge, along with those of two of his brothers. The English then tried to exterminate the rest of the Wallace family and they largely succeeded in doing so. A few of them escaped, making a perilous journey by boat across the North Sea to Bergen in Norway, where they settled and began a Norwegian Wallace line that survives to this day. Dahl’s grandmother, Ellen Wallace, was a descendant of those plucky fourteenth-century refugees. She married Karl Laurits Hesselberg, the grandson of the resourceful pastor who had escaped the church fire in Grue.

His father’s side of the family were somewhat different.

If the Hesselbergs were grand, middle-class, philanthropic intellectuals, the Dahls were grounded in earth and agriculture. They were ambitious, canny, uneducated and rough — albeit with an eye for craftsmanship and beauty. Roald’s father, Harald Dahl, was born in Sarpsborg, a provincial town some 30 miles from Christiania, whose principal industries in the nineteenth century were timber and brewing. Roald described his paternal grandfather Olaus as a “prosperous merchant who owned a store in Sarps-borg and traded in just about everything from cheese to chicken-wire”.

But the records in the parish church in Sarpsborg describe him simply as a “butcher”,

while other legal documents refer to him as “pork butcher and sausage maker”. They came, as it were, from the other side of the tracks. Indeed, Roald once admitted to Liccy that his mother’s family, the Hesselbergs, thought themselves “a cut above” the provincial Dahls and rather looked down their noses at them.

Dahl is a common enough name in Norway. There are currently about 12,000 of them in a population of 4.75 million. But until the nineteenth century there were hardly any at all. Olaus Dahl indeed was not born a Dahl. He was christened Olaves Trulsen on May 19, 1834, the son of Truls Pedersen and Kristine Olsdottir. After his own given name, he took his father’s first name and added sen (in English “son of”) onto the end of it in the traditional Scandinavian manner. In this way surnames changed from generation to generation, as they still do in many Icelandic families. Spelling too was erratic — in records Olaus appears also as Olavus, Olaves and Olav. But at some point in his twenties he took the decision to “Europeanize” himself and acquire a fixed family name. Many others around him were doing the same, including his future wife Ellen Andersen, who changed her name to Langenen. Why Olaus chose Dahl, which means “Valley”, is uncertain, although it seems to have been a popular choice with others who came from the lowlands rather than the mountains.

Olaus’s story is typical of that of many Norwegians in the mid-nineteenth century. He was born into a small farming community, where his parents eked out a miserable existence. There, the short summers were filled with endless chores, while the winter brought only darkness and misery. The fogs swept in from the sea, swathing their primitive homestead and few acres of land in a damp, suffocating cloak of gloom. For much of the year, life was unbearably monotonous. If contemporary accounts are an accurate guide, in one corner of their two candlelit rooms, perched above the snorting animals, his mother would probably be spinning. In another his father was getting drunk. For generations, rural families had lived like this; subsisting, struggling simply to survive, grateful for the land they owned, yet tied to it like slaves. They were illiterate and uneducated. There was little or no scope for self-improvement. They aged prematurely and died young. Olaus would not have been alone in feeling the need to escape from a landscape that drained his energies and sapped his need for change. So, at some point in his late teens, he abandoned the countryside, and went to the expanding industrial town of Sarpsborg, some 20 miles away, where the railway would soon arrive. There he got a job as a trainee butcher and set up home with Ellen, from nearby Varteig. After a few years, he opened his own butcher’s shop.

Early twenty-first-century Sarpsborg is a grim place. Gray and ugly, it is dominated by a sullen 1960s concrete and steel shopping centre, which crouches next to the mournful remains of the nineteenth-century town. The outskirts are relentlessly, oppressively industrial. It is a far cry from the ancient splendours of Trondheim, the civilized serenity of Oslo, or the picturesque fjords and fishing villages of the western coast. On a dull Saturday afternoon in November, drunken and overweight supporters of Sparta, the ailing local football team, stagger from bar to bar. The occasional raucous cheer suggests an attempt at rowdiness. But one senses their hearts are not quite in it. Depression stalks the streets. In quiet corners, solitary older inhabitants drink furtively, seeking out the darkest corners of gloomy cafés in which to hide. Others huddle in groups, saying nothing. No trace remains of the butcher’s shop where Olaus plied his trade, or of the house in Droningensgade where he raised his family and where he lived with his servant Annette and his assistant Lars Nilssen. Like so many other older Sarpsborg buildings, they have long since been destroyed.

When Olaus died in 1923 at the age of eighty-nine, Roald was only six. It is not clear that he ever met him, although in Boy he confidently describes his paternal grandfather as “an amiable giant almost seven foot tall”.

Some of the other detail he gives about the man is entirely fictitious. For example, he claimed that Olaus was born in 1820, some fourteen years earlier than he actually was. Perhaps he confused him with his great-grandfather Hesselberg, the son of the pastor from Grue, who was indeed born that year. Perhaps not. Yet this lack of concern for detail blinded him to one unexpected anomaly of his own family history. Olaus and his wife Ellen had six children: three sons and three daughters over a period of thirteen years. Harald was born in 1863, Clara in 1865, Ragna in 1868, Oscar in 1870, Olga in 1873, and finally Truls in 1876.

Examining the local baptism and marriage records, however, reveals a surprising and perhaps significant detail: Roald’s father was illegitimate. Harald was born in December 1863, but his parents did not actually marry until the following summer. He was christened on June 26, 1864, when he was six months old, and just five days after his parents’ wedding. Whether Harald was aware that he was born a bastard is unclear, but in a small community like Sarpsborg, it was unlikely that fact would have been kept a secret from him for long, and the associated stigma may well have fuelled his desire to start a new life elsewhere.

Harald undoubtedly had a hard childhood. In Boy, Roald tells the gruesome story of how, aged fourteen, his father fell off the roof of the family home, where he was repairing loose tiles, and broke his arm. A drunken doctor then misdiagnosed a dislocated shoulder, summoning two men off the street to help him put the shoulder into place. As they forcibly manipulated young Harald’s arm, splinters of bone started to poke through the boy’s skin. Eventually the arm had to be amputated at the elbow. Dahl tells the tale with his usual lack of sentiment, explaining how his father made light of his disability — sharpening a prong of his fork so he could eat one-handed, and learning to do almost everything he wanted, except cutting the top off a hard-boiled egg, with a single hand. It’s a good tale. Suspiciously good. So it is not surprising to discover that Roald confessed to one of his American editors, Stephen Roxburgh at Farrar, Straus & Giroux, that he had invented much of it and that he had particularly enjoyed devising the detail of the sharpened fork.

Photographs confirm that his father’s arm was certainly amputated. But it’s also possible that Dahl’s version of the accident hid a more squalid domestic truth and that it was a drunken parent rather than a drunken doctor who was responsible for the amputation. We don’t know if Harald was a fabricator of the truth — his wife certainly was, and she was the one who passed the family legends down to Roald — but he was studious, thoughtful, and had a passion for beautiful things. He had little in common with his father: the obstinate and rough-hewn butcher, who squandered his money betting on local trotting races.

Harald and his brother Oscar must have elected to leave Norway some time in the 1880s. Writing a hundred years later, Roald describes the decision in characteristically simple terms:

My father was a year or so older than his brother Oscar, but they were exceptionally close and soon after they left school they went for a long walk together to plan their future. They decided that a small town like Sarpsborg in a small country like Norway was no place to make a fortune. So what they must do, they agreed, was to go away to one of the big countries, either to England or France, where opportunities to make good would be boundless.

Both went to Paris, but their motivations for leaving were almost certainly more complex than Roald made out. To begin with, the two brothers were nothing like the same age. There was a seven-year gap between them. So, even if Oscar had just left school when he departed for France, Harald would have been a young man in his twenties. The fact that Roald also maintained his grandfather “forbade” his two sons to leave and that the two men were forced to “run away”

suggests it took a while for the slow-burning Harald to pluck up the courage and defy him. Two more of Olaus and Ellen’s children also left Norway at this time: Clara went to South Africa and Olga to Denmark. Only Ragna and her youngest brother, Truls, stayed behind. Truls became his father’s apprentice and eventually took over the butcher’s shop, staying with him, one suspects, largely for business reasons.

The two older Dahl brothers left Norway on a boat. It’s quite possible they worked on ships for a considerable period of time before they ended up in Paris, for both of them later went into careers that involved quite detailed knowledge of shipping. What exactly they did when they got to the French capital remains unclear. Family legend has it that they went there to be both artists and entrepreneurs — an improbable combination of skills perhaps, but one that would define Roald, in whose mind there was always a natural link between making art and making money. It was the same with his elder sister Alfhild. Sitting in the garden of her house in the Chiltern Hills, a stone’s throw away from where her brother lived, her weathered features broke into a wrinkly grin as she recalled her father and uncle, seventy years earlier. “They left Norway to become artists, you see,” she told me. “They went to make their fortune. They just assumed they could do it.”

It was as if her brother were speaking. The crackly voice, the clipped, matter-of fact delivery, the wry chuckle.

The big picture, too, is similarly vivid and compelling, always uncluttered with qualifications or a surfeit of detail. For Alfhild, Harald and Oscar were typical Nordic bohemians, who came to Paris for its glamour, its freedom, and its artistic energy. Fictionalized versions of these Scandinavian visitors appear in literature of that period — Oswald in Ibsen’s Ghosts, for example, or Louise Strandberg in Victoria Benedictsson’s play The Enchantment. They left the stern world of the North for a “great, free glorious life”

among the boulevards and cafes, where geniuses mixed cheek-by-jowl with the indigent, where anarchists plotted social revolution, and where painting was in a ferment of change that had not been seen in one place since Renaissance Florence.

Fading sepia photographs give us a glimpse of the lost world they lived in: days at the races, fancy-dress parties, lunches on summer lawns in Compiegne and Neuilly. And then they painted. It was the golden age of Norwegian painting, and in Paris Harald would almost certainly have mixed with the leading Scandinavian painters of the day, including Edvard Munch and Frits Thaulow. Not that Harald was a modernist. He was a craftsman, who carved mirrors, picture frames and mantelpieces, and painted rural scenes. A few examples of his work survive — subtle, well-crafted landscapes in the Scandinavian naturalistic style. At Gipsy House, one of them, an impressionistic pastel in green, blue and brown, still hangs by Liccy Dahl’s bedside. It is reminiscent of the dismal rural setting from which Harald’s father had fled. A clump of straggly spruces tremble by the side of a placid lake, like a skeletal family tentatively approaching the chilly waters. No sunlight illuminates the scene, nor is there any sense of human habitation. In the foreground, reeds are tugged by a gust of wind. In the background, the bare mountains rise up into the haze toward the distant sky.

The visual arts were an important and little understood aspect of Roald Dahl’s life and formed a continuous counterpoise to his literary activities. All his life he bought and sold paintings, furniture and jewellery — sometimes to supplement his literary earnings. He even opened an antique shop. That connection between business and art, which came as naturally to him as breathing, would puzzle and irritate many of Dahl’s English literary contemporaries, who resented his skill at making money and disliked the pride he took in his own financial successes. It frequently caused misunderstandings. The British novelist Kingsley Amis was typical. In his memoirs, he described his only meeting with Dahl. It was at a party given by Tom Stoppard in the early 1970s. There, Roald apparently suggested to Amis that, if he was suffering from “financial problems”, he should consider writing a children’s book, and went on to describe how he might go about doing so. Amis, who had no interest in children’s fiction, felt he was being patronized by Dahl’s suggestion that his own writing was not bringing him enough money. Dahl, for his part, was in precisely the kind of English literary environment he loathed. He knew that Amis, like most of the guests, did not respect children’s writing as proper literature and this attitude made him feel vulnerable. Drunk and ill at ease, he probably felt that the only way to keep his head up with Amis was to talk money. The clash of attitudes was bitter and fundamental. Noting that Dahl departed by helicopter, Amis concluded: “I watched the television news that night, but there was no report of a famous children’s author being killed in a helicopter crash.”

The need for financial success was in Roald’s blood. His father and his uncle Oscar had both evolved into shrewd businessmen. When the two brothers eventually separated in Paris, Oscar travelled to La Rochelle, on the west coast of France, with his new wife, Therese Billotte, whom he had rescued from a fire in 1897 at the Bazar de la Charite. As with the fire in Grue, this had killed over one hundred people.

Billotte was from a family of painters. Her grandfather was the French writer and artist Eugene Fromentin, most famous for his naturalistic depictions of life in North Africa, while her uncle, Rene Billotte, was a commercial landscape painter, whose murals of exotic scenes still decorate Le Train Bleu, the elaborate gilded dining room of Paris’s main railway station to the South, the Gare de Lyon. In La Rochelle, Oscar started a company of fishing trawlers called Pecheurs d’Atlantique. His fleet began the practice of canning its catch on board ship, and became so successful that Roald could justifiably boast after the war that his uncle was “the wealthiest man in town”.

With the money he made, Oscar indulged himself. He purchased the Hôtel Pascaud, an elegant eighteenth-century town house, and filled it with exquisite objects. Roald would later fondly describe it as “a museum dedicated to beauty”.

Oscar was a complex character. He was an aesthete but, like his father Olaus, also something of a bully. Roald would always have a turbulent relationship with him. During the war Oscar remained in Occupied France, collaborating with the Nazis, while his son fought in the Resistance. One family legend has it that, after the war was over, he was publicly tarred and feathered by a group of bitter locals and that father and son never spoke again. However, what is certain is that this exotic French uncle, with his Viking appearance and fastidious taste, left an indelible impression on his young nephew — if only for his facial hair.

My late uncle Oscar… had a massive hairy moustache, and at meals he used to fish out of his pocket an elongated silver scoop with a small handle on it. This was called a moustache-strainer and he used to hold it over his moustache with his left hand as he spooned his soup into his mouth with his right. This did prevent the hair-ends from becoming saturated with lobster bisque … but I used to say to myself, “Why (doesn’t he just clip the hairs shorter? Or better still, just shave the (damn thing off altogether and be done with it?” But then Uncle Oscar was the sort of man who used to remove his false teeth at the end of dinner and rinse them in his finger-bowl?

Harald’s temperament, like his moustache, was less extrovert than his brother’s. And he remained in Paris a little longer. However, some time in the 1890s, when he decided that he was tired of the vie bohemienne, he headed not to La Rochelle but to South Wales, to the coal metropolis of Cardiff, where he had heard that enterprising Norwegians could make their fortune.

(#ulink_9ec5db95-45a1-5036-ac5c-032dc3df8e25)Most of the Vaernes farmlands have now been subsumed into Trondheim Airport, but the actual building Hans Theodor owned is still standing. He is buried nearby in the cemetery of Vaernes Church.

(#ulink_2c11d787-59d2-531e-bdb5-8acc219bb92f)Confusingly, the capital of Norway has undergone several changes of name. Ancient Norse Oslo was renamed Christiania in 1624 after King Christian IV of Norway rebuilt it following a disastrous fire. In 1878, Christiania was refashioned as Kristiania, and in 1925, the city became Oslo once again.

CHAPTER TWO (#u146a6ad4-446d-572e-a044-156c49de32a9)

Shutting Out the Sun

THE HISTORY OF TRADING between Norway and South Wales goes back well over a thousand years. Medieval chroniclers writing of the land of Morgannwg, now Glamorgan, in the period between the Roman settlement and the Norman Conquest celebrated the visits of Norwegian traders, comparing them favourably to the “black heathens”,

the Danes, whose intentions often seemed more inclined toward rape and pillage than commerce. Curiously, recent evidence suggests that Welsh men and women, captured in the valleys and sold into slavery, may have been the first major commodity exported from Wales to Norway;

however, by the mid-nineteenth century, trade in human souls had given way to a sophisticated, booming and lucrative business relationship based on timber, steel and above all, coal. Boats from Norway, already the third largest merchant fleet in the world, arrived in Cardiff with timber, mostly to use as pit props (which the Welsh miners called “Norways”), and left carrying coal and steel to all parts of the globe. In twenty years the city’s population doubled as it became the world’s major supplier of coal. By 1900, Cardiff was exporting 5 million tons of coal annually from more than 14 miles of seething dockside wharfage. Two thirds of these exports left in Norwegian-owned vessels. The city was consequently awash with commercial opportunities for an enterprising, intelligent young expatriate, tired of his sojourn in Paris and eager to make his fortune.

Cardiff, of course, already boasted a considerable number of resident Norwegian nationals. But the majority were transient sailors. In 1868, the Norwegian Mission to Seamen had constructed a little wooden church between the East and West Docks on land donated by the Marquis of Bute. It was a place of worship, but also a place where the ships’ crews, many of whom were as young as fourteen, could relax and read Norwegian books and newspapers, while the cargo on their boats was loaded and unloaded. A model ship hung from the ceiling, and the walls were decorated with Scandinavian landscapes and pictures of the royal families of Sweden, Denmark and Norway. The tables were even decorated with miniature Norwegian flags.

Up to 75,000 seamen passed through the Mission’s doors each year, eager for reminders of home in this hostile industrial environment. The docks were noisy, filthy, and could be terrifying — particularly to anyone from a rural background. An experienced Norwegian sea captain described the city: “It’s not difficult to find Cardiff from the sea,” he told his young nephew, who was about to sail there for the first time; “you just look for a very black sky — that’s the coal dust. In the middle of the dust, there is a white building, the Norwegian Seamen’s Church. When we see that we know we are home.”

The tiny church, with its plucky spire, quickly became a symbol for the Norwegian community in Cardiff, although most who settled there integrated with the local Welsh community, and used it simply for births, marriages and deaths.

Today it stands restored, looking out at redeveloped Cardiff Bay, as if saluting the most famous of its congregation, who was christened there in the autumn of 1916, and whose name now graces the public area between the church and the grey slate, golden steel modernity of the new Wales Millennium Centre: Roald Dahl.* (#ulink_c8533c89-8f27-5f33-9211-4fcd22495c9a)

Exactly when Harald Dahl arrived in South Wales is not clear. He does not figure in the UK census of 1891; however, by 1897 a mustachioed and dapper Harald is posing for a portrait photographer in Newport, some 15 miles along the coast from Cardiff. His long, flat face, round forehead and confident, sardonic eyes bear little resemblance to the oafish features of his father, which scowl out of an earlier page in the same family photograph album.

It’s likely that this photograph of Harald, despatched to sisters and friends in Paris, was taken not long after he arrived in the Cardiff area and began learning his trade in shipping. In 1901 the census records that he was still single, working as a shipbroker’s manager and lodging near the docks in a small redbrick terrace at No. 3, Charles Place, Barry, in the house of a retired land steward called William Adam, his wife Mary and their two adult daughters. Yet, despite his relocation to South Wales, a significant part of Harald’s heart had remained in France. He had fallen in love with a glamorous doe-eyed Parisian beauty named Marie Beaurin-Gressier. Later in the summer of 1901, he returned to Paris and married her.

Her granddaughter Bryony describes Marie as coming from “a posh ancien régime family that had become rather impoverished and down on its luck”.

Certainly, the Beaurin-Gressiers were not bourgeois. Though they had houses in Paris and in the country, near Compiègne, they seemed more inclined to sport and leisure than to commerce. Rugby was a dominating interest. Two of Marie’s brothers, Guillaume and Charles, played for Paris Stade Français, the latter representing his country twice against England, while one of her sisters married the captain of the French team that won a gold medal at the 1900 Olympics. Another sister went to Algeria and married an Arab. Another brother ran a well-known Parisian fish restaurant. Yet another was an auctioneer. Marie was the most beautiful. Waiflike, elfin and delicate, she had a pale complexion, a mop of thick dark hair and sad, serious eyes. Fifteen years her senior, Harald must have had enormous charm, as well as good financial prospects, to succeed in stealing her away from her warm and adoring family. A snapshot of her on her wedding day, on a sunny veranda in the French countryside, beaming with delight and surrounded by admirers, suggests that she was very much in love. But it also suggests her innocence. She can surely have had little sense of what life in industrial Cardiff would offer her. Perhaps to counteract any potential feelings of homesickness, Marie brought some reminders of France with her to South Wales. Her trousseau boasted a diverse collection of jewellery, paintings and furniture, including a rosewood bedstead, various antique tables, chairs, secretaires, cabinets, an astronomical clock and an elaborate Louis XVI timepiece. Touchingly there was also a gilt mirror “carved by Mr Dahl and presented to Mrs Dahl”.

Shortly after the newlyweds returned to Cardiff, Harald went into business with another expatriate Norwegian, three years younger than he was: Ludvig Aadnesen. The two men had become acquainted with each other in Paris, but the Aadnesens, who came from Tvedestrand, near Krager0, the birthplace of Edvard Munch, were already part of Harald’s extended family. One of them had married Harald’s sister Clara, and emigrated to South Africa with her.† (#ulink_aca0a189-6ea6-5a29-a0c7-35e467506f3e) Ludvig, a lifelong bachelor, shared Harald’s fascination for painting and became his confidant and closest friend.

Financially, it was a good move. Over the next two decades the ship-broking firm of Aadnesen & Dahl, which supplied the ships that arrived in the docks with fuel and a host of other items, would expand from its small room in Bute Street to acquire offices in Newport, Swansea and Port Talbot, as well as large premises in Cardiff, which at one point also housed the Norwegian Consulate. Gradually the partnership began to trade in coal as well as simply supplying ships, and both men became rich. Dahl and Aadnesen were business partners, but they were also immensely close, and Ludvig occupied “an incredibly special place”

in Harald’s affections. In the family he was always referred to as “Parrain” (the French for “Godfather”), and when Harald died, he bequeathed to his “good old friend and partner” the only named object in his will: a painting by Frits Thaulow called Harbour Scene. The painting, now lost, must have symbolized many shared memories for the two men. It spoke, of course, of ships and the sea that had caused them both to move to Wales, but it also evoked their youth together in Norway.

Harald’s marriage to Marie began promisingly. He rented an Arts and Crafts seafront house near the docks in Barry, round the corner from where he had been lodging, with a first-floor balcony that offered a fine view of the bay. There, their first child, Ellen Marguerite, named after Harald’s mother, was born in 1903, and a son Louis, named perhaps after her elder brother, three years later in 1906. Those are the bare statistics. Yet while archival research can reconstruct the landmark events of a vanished life — its births, marriages and deaths — it cannot bring to life the personality that lived between these records without more personal, idiosyncratic evidence. Harald left diaries, letters, paintings, odd pieces of carving, and other artefacts that hint at his character. The contents of the expensive French leather wallet that was in his pocket when he died, for example, now carefully preserved at the Roald Dahl Museum and Story Centre in Great Missenden, complete with postal orders and railway season ticket, testify both to his good taste and meticulous habits. Of Marie, however, nothing remains. Even the gilt mirror is no longer in the family.‡ (#ulink_ad84a855-c4b1-5c10-b7de-b7b7f29ddd92) It is consequently hard to hypothesize how she coped with her new life in Barry. But it’s more than likely she suffered. Far away from her family and from the world she loved, the grime and dust of Cardiff Docks must have seemed a poor replacement for the elegance of Paris or the delights of summer days in Compiègne. Living with a Norwegian husband, fifteen years older than she was and accustomed to solitude, also cannot have been easy.

On October 16, 1907, while heavily pregnant with their third child, Marie died. She was twenty-nine years old. Her death certificate indicates that she collapsed and died of a massive haemorrhage caused by placenta praevia — an obstetric complication, where the placenta lies low in the uterus and can shear off from it, causing sometimes fatal bleeding. Someone called Mary Henrich, probably a nurse or nanny as she was also living at the house, was present when Marie died and reported her death to the authorities. Marie’s granddaugther Bryony however remembers a rumour whispered in the family (perhaps stemming from Roald’s mother, Sofie Magdalene) that Marie had been depressed and died from a failed abortion.

While it is possible that an attempt to terminate the pregnancy artificially might produce similar symptoms to placenta praevia haemorrhage, the risks for the abortionist if the pregnancy was advanced would have been enormous. So, unless Marie had attempted somehow to do it herself, the official version seems a good deal more plausible.

Marie’s death left Harald devastated. He had almost completed building a splendid new whitewashed house for his family, far from the commotion and noise of the docks, in leafy Llandaff — a medieval town that the railway had made a suburb of Cardiff. Harald had designed many of the building’s details himself and proudly named his new home “Villa Marie” in honour of his young wife. Sadly, she never saw it finished. It survives today, though its name has changed,

but its steeply sloping gables and idiosyncratic Arts and Crafts appearance, with leaded windows and faux medieval buttresses, suggest how much Harald himself had contributed to the design and how much he must have looked forward to a settled and happy family life there. Instead, at forty-four, he found himself suddenly on his own — left to raise two tiny children, aged three and one, neither of whom would ever remember the dusky, wide-eyed waif whose beauty had so bewitched him.

Following Marie’s death, her mother Ganou came over from Paris to help look after Ellen and Louis. Harald drowned his sorrows in hard work, spending long hours in his office and obsessively tending Villa Marie’s substantial garden.

Four years passed. Then, one summer, Harald went away to visit his sister Olga, who was now living in Denmark.

Whether he was lonely and went consciously in search of a new bride, as Roald maintained in his memoir Boy, is uncertain, but it was in Denmark, not Norway, as Roald later claimed, that the Dahls and the Hesselbergs finally connected. Sofie Magdalene Hesselberg, who was visiting friends, had strong, almost masculine features that were in sharp contrast to Marie’s delicate, almost doll-like appearance. Within a matter of weeks she and Harald were engaged.

It was a convenient match for both of them. She was twenty-six years old, sturdy, strong-willed and eager to break the tie with her parents. He was prosperous, established, and old enough to have been her father. Harald however had to overcome strong opposition from Sofie Magdalene’s parents. Karl Laurits and his wife Ellen were by now wealthy in their own right. He was treasurer of the Norwegian Public Service Pension Fund and both were very controlling personalities. Their only son had recently died, and their three daughters were now the focus of their attention. Sofie Magdalene was considered the least attractive of them, and felt herself in some ways the “Cinderella” of the trio.

Nevertheless Karl Laurits was disconcerted that his eldest wanted to marry a man only ten years younger than he was. Worse still was the fact that she planned to leave Kristiania and live in Wales. But Sofie Magdalene was determined, and her parents were eventually forced to consent grudgingly to the wedding.

Her stubbornness in doing so may also have been farsighted. Ahead of her, she may have seen the fate that would befall Ellen and Astri, her two younger sisters. They failed to escape their father’s thrall and were destined to live out their entire lives in the parental home. Increasingly eccentric, they became a growing source of curiosity and amusement for their younger relations, who remembered them, either drunk or drugged, sitting on the veranda of their home in Josefinegate, like characters in an Ibsen play, methodically picking maggots out of raspberries with a pin.