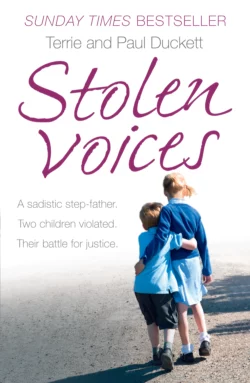

Stolen Voices: A sadistic step-father. Two children violated. Their battle for justice.

Terrie Duckett

He beat them, he abused them, and he tortured them. He broke their dreams. But they came back stronger.‘Terrie and Paul are two of the bravest people I have ever met. I have only shared the briefest glimpse into the true horrors this brother and sister have endured, but I rarely come across cases this bad. After the unspeakable abuse and shocking betrayals, two incredible human beings came through – to inspire us all.’Sara Payne OBE, co-founder of Phoenix SurvivorsTerrie and Paul’s step-father had been living with them for six months when the abuse and grooming began. What started as innocent conversations and goodnight kisses quickly developed into something far darker and depraved.Everyday Terrie was assaulted and abused; her rapes were photographed, filmed and shared. Paul was regularly taunted and mercilessly beaten. But despite the bruises and the scars, and the desperate pleas for help, no one saw their pain.But through it all they stuck together, battling for their childhoods for over a decade and masterminding creative ways to outwit their stepfather and buy themselves fleeting moments of joy.In March 2013, thirty years on, Terrie and Paul made the brave decision to give up their right to anonymity to tell of the years of abuse they endured at the hands of their recently convicted step-father and raise awareness for the ongoing battle for justice for victims of child abuse. A powerful testament of what can be achieved through courage and love, this is their inspiring story.

(#u8c3278d8-cde6-50c1-809b-e54a04f9df02)

Contents

Cover (#u3db53ae0-ad8f-542e-bc3f-d34e1d041009)

Title Page (#ulink_0850af03-c3a2-5148-979c-2f6f4f16e493)

Dedication (#ulink_a099e6b5-d971-5b63-934c-c6da081432b4)

Prologue (#ulink_7f0fed5a-1c86-5dd2-8158-ac9bed522824)

Chapter 1: ‘Humble Beginnings’ (#ulink_1276699c-bd9c-5d31-ae5b-fc860e9afd59)

Chapter 2: ‘In the Picture’ (#ulink_36d8702d-32ae-5d8c-8a8e-d0da0cd8e1f6)

Chapter 3: ‘Last Laugh’ (#ulink_542c5c8f-a35f-5709-afbc-26f85b2a4b38)

Chapter 4: ‘New Beginnings’ (#ulink_ebd95fc4-c99c-5fb3-bb08-f48809fb7a84)

Chapter 5: ‘Family Games’ (#ulink_ee3a4f0b-f013-5962-90e2-631c9c8bf1b0)

Chapter 6: ‘Eye of the Storm’ (#ulink_7efdb55f-cda0-538a-9138-ca49c9e778a4)

Chapter 7: ‘A Dog’s Life’ (#ulink_f391c4f8-20be-5bd7-b92d-c9b811213073)

Chapter 8: ‘Hidden Hurt’ (#ulink_9df62ab7-8d03-5931-908f-cceebb132ac8)

Chapter 9: ‘Fighting Back’ (#ulink_8ef909ff-a77f-56ef-b265-1a3d42ea2d62)

Chapter 10: ‘Tipping Point’ (#ulink_88dfd70b-7bf6-5ad5-915c-e7581cdc882e)

Chapter 11: ‘Down not out’ (#ulink_3105689d-316c-53e7-a368-9d91b143d4c8)

Chapter 12: ‘Into an Abyss’ (#ulink_676994c6-30f4-560b-b5f0-742ebb332ba7)

Chapter 13: ‘An Eye for an Eye’ (#ulink_e999cbea-4996-5c24-be4c-edeb8e19e168)

Chapter 14: ‘Holiday Hell’ (#ulink_78c53e02-44b7-56ca-ac84-b705604f874e)

Chapter 15: ‘Timed Torment’ (#ulink_21ab731f-2f87-5e88-998b-7cc0dac6a4e3)

Chapter 16: ‘Fresh Hell’ (#ulink_9c6f2f19-b022-54c1-94cb-1d943b64707f)

Chapter 17: ‘Betrayal’ (#ulink_e37a724f-d953-51fe-bf57-cf51396c38df)

Chapter 18: ‘Best-laid Plans’ (#ulink_a4fb4345-565b-5cc0-ae65-1c4b5886ef0d)

Chapter 19: ‘Thwarted’ (#ulink_597f42da-74ce-57da-9a9b-995207d62e60)

Chapter 20: ‘Thumbscrews’ (#ulink_1ed7075a-45f3-5a39-b4a8-512c825284ed)

Chapter 21: ‘Work Life’ (#ulink_d84784c9-3aeb-54c8-8cb7-2486b706c59c)

Chapter 22: ‘Triggered’ (#ulink_90a80b41-12c3-5a37-af41-8cabbf7224d9)

Chapter 23: ‘Cycle of Life’ (#ulink_daa320eb-cf0e-5344-b0f4-afe02d877db2)

Chapter 24: ‘Taking the Bullet’ (#ulink_bf728e7c-5acc-5336-b4a5-21dbeb5e4666)

Chapter 25: ‘Hope’ (#ulink_d730330c-25e0-5f80-80bf-59880dd81738)

Chapter 26: ‘Straightjacket’ (#ulink_5ac20ba1-a4ea-5faa-a236-1d26a80f2dfb)

Chapter 27: ‘Gloves Off’ (#ulink_2db866a9-033d-5844-8bf9-2eca26e86843)

Chapter 28: ‘Shadow in Sun’ (#ulink_956ad2c0-e754-591b-9061-00946d451303)

Chapter 29: ‘The Truth’ (#ulink_bc899349-11ca-52db-bc43-f8727b5ed132)

Chapter 30: ‘Police Searches’ (#ulink_e6686711-fcb9-51a2-b111-0c112dca0de3)

Chapter 31: ‘The Trial’ (#ulink_32d69c3b-1d67-59b5-ad47-be0869e73e33)

Afterword (#ulink_30b39048-4885-584c-8199-973039c8237e)

Exclusive sample chapter (#u33b2ee8f-11e4-5ee0-bce5-f684beb0e79f)

Moving Memoirs eNewsletter (#ud6f41165-2f12-5428-a3b5-d2b2a98225c3)

Copyright (#ulink_fa747ee6-e787-5008-9883-3d951c715f32)

About the Publisher (#u69a479ce-e2c9-5deb-8b27-f57f6ac30d5a)

Dedication (#u8c3278d8-cde6-50c1-809b-e54a04f9df02)

We dedicate this book to each other and to every other brother and sister struggling to survive: with strength, humour and love we came through this together. Our bond is unbreakable.

Prologue (#u8c3278d8-cde6-50c1-809b-e54a04f9df02)

June 2012

‘What’s up?’ I yawned into the phone to my brother Paul. It was almost 1 a.m. and I was feeling bloody tired.

‘I’ve just got off the phone to the police,’ Paul blurted out. ‘You know they arrested Peter today and searched the house? Well, you’re just not going to believe this!’ He took a breath. ‘Apparently, it’s been designated a crime scene and they’ve left police outside all night, to make sure no one gets in. There was so much evidence they ran out of time and need to go back and collect the rest. They reckon it’s an “Aladdin’s cave”. Their words, not mine.’ There was a slight pause. ‘I’m gonna drive over. Do you wanna come?’

I didn’t even have to think twice. ‘Yes! Come and get me. I’ll be waiting outside.’ I hung up, threw on some clothes and ran outside. I stood waiting impatiently by the side of the road, trying to calm my breathing. A few moments later, Paul’s car turned the corner and pulled up next to me. I jumped in and we screeched away.

‘Fasten seat belt,’ Paul’s car lectured me repeatedly in a mechanical monotone.

‘All right, all right, shut the fuck up,’ I muttered, cutting the car off as I clicked the belt in place. Paul rolled his eyes and drove on.

We drove silently towards our childhood home, lost in our thoughts. We were both feeling numb, not able to believe they had finally arrested him. We had had a couple of intensely stressful weeks waiting for the police to call, and now here we were driving towards the place we had barely survived as children, not knowing quite what to expect.

None of the events of the past few weeks had actually sunk in; whether it was the police telling us it was the worst case they had dealt with in a long time, the pitying looks we had received as we gave our interview, or the fact that we’d been brave enough to tell anyone at all.

My thoughts snapped back into focus as the car turned into Churchill Avenue, an ordinary estate filled with neat council houses; a place we’d avoided for over 10 years because it evoked so many traumatic memories. As the well-trodden pavements swept past, my stomach twisted into a hard knot.

In the distance the familiar silhouette of our childhood home loomed: the box-shaped porch, the white wooden cladding, the thin paving snaking from the public footpath to the front door. Such an innocent-looking house, yet one that hid so many dark secrets. Today Number 59 looked tardy and neglected.

As we approached, we saw a police car parked opposite the house with two men inside it. With a quick glance at Paul, I could tell we both felt weird and in some ways wrong to pass by the empty house. The reality was starting to sink in, and although neither of us was sure how as victims we were meant to act, we knew that together we’d get through it, just as we did through our childhood.

Paul accelerated so that we passed the house at normal speed.

‘Well, it looks like we’ve got the ball rolling now,’ breathed Paul as he sucked long and hard on his roll-up.

‘I’ve got a feeling this isn’t going to be an easy journey.’ I sighed.

‘Can’t be any harder than what we’ve been through,’ Paul commented.

‘Don’t you wish we could have told our younger selves how things would work out?’

‘I wouldn’t change a thing; the struggles we went through have made us the people we are today. I believe if we changed one thing in our past it would change who we are now.’

I glanced at Paul and nodded. ‘True.’ I was full of apprehension about the days and weeks ahead. I was just glad we had each other.

Chapter 1

‘Humble Beginnings’ (#u8c3278d8-cde6-50c1-809b-e54a04f9df02)

Terrie

My parents, John and Cynthia, were childhood sweethearts. Their relationship had begun like a storybook romance, but with their marriage their dreams died.

Mum intended to follow in her father’s footsteps in Northampton’s traditional calling, designing shoes, until she naively showed her designs to a local shoe manufacturer during one lunchtime, who stole them. Dad joined the parachute regiment and aspired to be part of the SAS – until he failed their selection course.

In 1968, with both their dreams in tatters, life was to change irreparably again. Mum discovered she’d accidentally fallen pregnant. To say Dad was not best pleased was an understatement, but in 1968 pregnancy meant marriage and that was that. So Mum abandoned her place in college and went up the aisle – or at least the corridor – of Northampton register office.

She didn’t tell her parents, my Nan and Pap – Gladys and George – at first. Not only had she let them down, but they believed she could do better than my dad. However, by the time she told them the damage had been done, and at the very least they felt he’d done the honourable thing.

I arrived on 27 June 1969 in Aldershot, the garrison town where Dad was based. For the first month of my life we lived in married quarters, though Dad was desperate to be released back to Civvy Street, not being able to face being returned to his parachute regiment after failing the SAS selection course. The only way he could be discharged was to buy himself out, so Mum raided her savings and stumped up the required £200 – a prohibitive sum, but a small price to pay to keep her new husband happy.

Mum and I lived my first year with my Nan and Pap in their cosy two-bedroom house. But the first home I remember clearly was a council maisonette in Moat Place. It was a bit sparse; the kitchen and lounge were downstairs and the bedrooms were up a white-painted stairway that had a thin carpet runner tacked loosely to the wood. Two wooden slats ran down the side of the stairs, with a narrow gap between them, so that as a small child I could peer through. I spent a fair bit of time sitting in nervous silence on those stairs, listening to Mum and Dad argue their way through life.

Dad worked away a lot of the time, stopping home for clean clothes and food maybe once a fortnight. When he wasn’t there to argue with Mum, I felt happy and relaxed. I had my mum all to myself and we had our routine. We didn’t have a lot of money, or many belongings, but she had time for me – even though I could be more of a hindrance than a help, as a simple trip to the shops could turn into an adventure.

At the age of four, whilst I was dawdling back from the shops with a loaf of bread for tea, I thought of Hansel and Gretel. ‘I wonder what would happen if I dropped a trail of bread slices?’ Imagining a magical creature might appear, I pulled slices of bread out of the bag and began placing them carefully on the pavement. Skipping along, I looked over my shoulder, pleased at the snowy trail … until Mum suddenly appeared, looking up the road for me. ‘Terrie!’ she cried. ‘What are you doing? That’s our tea!’

I held a slice of bread mid-air and my face crumpled. ‘Sorry, Mummy.’

She scurried to scoop up the slices and put them carefully back into the bread bag for later.

The weekends Dad came home left their impression on me. One such weekend, when I was three, I was sitting in the kitchen waiting for Mum to dish up dinner when he arrived. I looked up as he walked in, but he didn’t seem to notice me.

‘Hurry up, I’m hungry,’ he complained to Mum. Mum seemed flustered and rushed to place the plates of macaroni cheese in front of us. ‘Is this it?’

Mum looked up. ‘I have some Spam if you’d like some?’

He laughed sneeringly. ‘This’ll do.’

I was actually relieved. I hate Spam – no, I detest Spam. Poor Mum was running out of new ways to cook it. Fried, battered and deep-fried, diced and sliced. For me any way was disgusting, and I would often gag trying to swallow the pink sludge.

I hated macaroni too. I couldn’t stop thinking about slugs as I tried to swallow the slimy pasta pieces. Dad would become frustrated with the faces I was pulling and send me up to my room, telling me not to come back downstairs until they had both finished dinner.

A few minutes later, as I cautiously slid back down the stairs on my bum, I could hear our budgie was squawking loudly. Dad was standing up shouting as Mum turned to look at me. He followed her gaze and saw me. ‘Get out! This is adult talk. Get out, now!’

I ran and sat on the stairs, scared and alone, peering through the gap.

At three years old, I was confused. I still wanted and needed to be loved by my dad, but I felt anger towards both of my parents for letting him come home and ruining my time with Mum. The rage had to get out somehow, so I began destroying things Mum had lovingly made for me. I picked apart a crocheted waistcoat made with squares of colourful pansies all sewn together. I cut the silky lining out of the green felt coat she’d made. And I carefully hacked my way across my fringe.

Dad’s presence at home meant rows and arguments, slammed doors and tears. Mum never really explained why it happened; I just thought it was my fault, because I was stupid and ugly.

It may have been that Dad felt trapped at home and would rather have been back amongst the camaraderie and banter of his army friends. Dad had joined the Territorial Army after being discharged out of the service, as it was more relaxed than the regular army. I enjoyed watching him with his mates in the TA, laughing and joking, so very different to how he was at home. Drill weekends often included family gatherings, lots of delicious food and kids running about, playing games amongst the lorries and heavy gear outside the drill hall.

But Dad did let a glimmer of his home face show there occasionally. Like the time he was supposed to be keeping an eye on me while Mum was inside with the other mums setting up for dinner. I was on my hands and knees pushing my new green plastic train that had two carriages attached. He warned me not to go near a large stack of bricks by the wall, but, me being me, I pushed my train a little hard. It sped off behind the brick stack. The top of the pile was leaning in towards the building, but there was a me-sized gap between the stack and the wall. I squeezed between and reached out for my train. I heard Dad yelling just before the pile fell onto my legs.

As he yanked me out by my arm, I said my leg felt funny and I refused to stand on it. ‘You’re just being a baby,’ he said.

I cried and he yelled for my mum. She gave me a look over and said I needed to get my leg checked. Later that day, as I showed my broken leg, plastered to the knee, to my Nan, she was horrified. She gave me extra cuddles to make up for it.

To me, Nan and Pap were perfect. Their house was an oasis of calm and I loved every brick of it, from the Indian-style felt-covered living room, where Nan saw faces and shapes in the patterns (‘Look, Terrie, there’s a goat!’ she’d laugh), to their conservatory where Pap would proudly show off his small cucumbers hanging around the door.

Nan had blonde wavy hair and sweet, flowery perfumed skin. She was always quick to cuddle me whenever she could. Nothing was ever too much trouble, whether it was cooking up delicious treats in the kitchen, playing pretend games or re-telling every fairy story I could absorb. Nan would pull up a chair in the kitchen, so I could stand and help her make dinner. Afterwards we’d play snap, or she’d get out a big tin of assorted buttons she’d collected over the years and we’d sit and thread them onto coloured cotton.

Pap was as round and cuddly as Nan, and they adored each other. He always had a twinkle in his eyes when he told me stories of when he was a boy and how mischievous he was.

All too soon, it was time to go home.

In late 1973, I was holding Mum’s hand as we walked across the Northampton market square, when she turned and knelt in front of me.

‘Mummy is going to have a baby.’ She looked a little worried, patting her tummy. I’d seen it getting rounder and fatter.

‘Okay.’ I shrugged, not really understanding. It was obviously something I was thinking about, though, as later that afternoon I pointed to Nan and Pap’s tummies. ‘Are you both having babies too?’ They laughed.

That evening I played with my only dolly, Baby Beans, named because she was filled with dried beans. I could hear Mum and Dad downstairs, and he didn’t seem happy. I tried banging my head against the wall to block out the sound of their voices. It didn’t work, but I did eventually manage to fall asleep.

When I woke in the morning, Dad had gone again for a few weeks. Mum heard me stir and called me into her bedroom. ‘Hey, Ted,’ Mum said, using her nickname for me. ‘Come and put your hand on my tummy.’

She held my hand firmly to her stomach, and I felt something move under the skin. ‘That’s the baby’s foot,’ she said, her face lighting up.

I looked at her big belly in confusion. ‘How did it get there?’ I pointed to her belly button and she laughed.

A couple of weeks later I was taken to Nan and Pap’s. ‘The baby is on its way,’ Nan said gently, ‘so Mummy is in hospital.’

I worried. I didn’t really understand what was happening. But the next morning Nan took me on a bus to the hospital and held my hand as she led me to a bed where Mum lay, looking exhausted but happy. As we reached the bed, Nan lifted me up so I could look into the crib. There was a little baby with a screwed-up pink face, swaddled in a blue blanket.

‘Isn’t he lovely?’ said Mum. ‘His name is Paul. He’s your brother.’

I grabbed Nan’s hand again. Everything seemed too strange, and I tugged at her to leave. I’d had enough of Paul already. ‘I don’t really want a brother, thank you,’ I said as politely as I could.

Mum was in hospital for a few days, after which Nan walked me back home. I tried not to cry as she knocked on the door to our house. As we entered everything smelled different, the house seemed messier and it didn’t feel like home. Nan gave me a kiss goodbye and headed home to Pap. I ran upstairs to my room and cried; I’d desperately wanted to go back with her, but dared not say anything.

The next few weeks were filled with nappies, washing, bottles and crying. Gently I stroked his fuzzy peach scalp while he was asleep. I was growing to like him. He always seemed to like me reading my picture books to him, so perhaps having a baby brother wasn’t going to be so bad after all.

Dad hated Paul crying and escaped out with his friends as much as he could. Tired from night feeding, Mum would let me take Paul out by myself in a big second-hand Silver Cross pram she’d borrowed. I proudly paraded him to my friends. ‘He’s my brother,’ I said proudly. ‘And it’s my job to look after him.’

Starting primary school gave me a chance to show off my reading skills. I loved going to school, though I did hate leaving Mum and Paul alone. I was used to having Mum’s time; now all of a sudden I had none.

Eventually we moved to a new council house in Churchill Avenue. Mum wanted us to go to a better school and live in a nicer area. The house was much bigger, with room for Paul and me to run around. By then Mum worked all hours, doing day and night shifts in a shoe factory. She always groaned when the bills arrived, and while Dad worked away we never had much food in the cupboards.

Mum walked me to my first day at lower school, only the second time she ever took me. I hated the mornings before school. My long hair was always knotted and tangled, and Mum had to yank the brush through. By the end of lower school Mum had had enough of the morning battle to brush my hair, so she placed a bowl on my head and cut around it.

I looked like a boy. I hated it. I clutched at my head, wondering what had happened. From that point on my hair was always kept short, Mum cutting it herself in the kitchen. ‘I’m not very good at this,’ she sighed. ‘But it’s just easier this way.’

The kids at school laughed at my hairstyle. They taunted me for having a boy’s name and tatty hair. At the age of six, I realised I didn’t fit in. My clothes were threadbare and my shoes worn to the sole. I was never invited back to anybody’s house for tea.

The closest person to me was my little brother, and I loved playing with him. He’d grown into a mischievous, adorable toddler with a mop of blond hair and a cheeky smile. He tried to follow me everywhere on his little red tricycle. He was always looking for attention from Mum – I’d just got used to not having any. In the evenings, if Dad was away, we’d be passed between babysitters and Nan and Pap while Mum worked until 9 p.m. But although Mum worked a lot, she, Paul and I were happy together.

Despite my age I could sense Mum and Dad’s marriage was falling apart, but occasionally we were able to pretend we were a happy family. At family barbecues or at TA events, sometimes Dad would chase us around with water pistols, laughing, and for a few minutes I could pretend everything was okay at home. On occasion he would surprise us all. Once he turned up after a few weeks away with a puppy, a beautiful tortoiseshell-coloured mongrel. We decided to name him Sam. We all loved him. Another time he brought us the biggest hand-made Easter eggs I’d ever seen.

I was eight when we met Dad’s friend Peter Bond-Wonneberger at one of the TA functions. Peter was in his early thirties, with dark hair brushed to the side and a wiry moustache. A smiling, happy guy, he always seemed up for a joke or laugh. He was married to Anne and they didn’t have kids. Anne didn’t seem that comfortable with our energy and playfulness, like Peter did.

‘Hello, Terrie and Paul!’ he beamed and crouched down to our height whenever he saw us. ‘Want to have a look at my camera?’ Peter was always snapping away.

Sometimes I wished Dad was more like him. Often they went off together to the TA Centre to develop photographs in a lab. Sometimes we were allowed in and saw them hanging on the line, dripping and smelling of chemicals.

Dad had gone off on a trip to Zimbabwe to see an old army friend, and asked Peter to pick him up from the airport. Peter arrived to collect us first. He was in a chatty mood, as usual, pulling on our seat belts, making sure we were comfortable.

‘What planes you hoping to spot, Paul?’ he asked.

‘Big ones!’ Paul giggled.

‘Great! I’ll get a shot of a jumbo for you,’ he replied.

It felt good to have an adult, especially a man, showing interest in our lives. On the way back we stopped off at Dunstable Downs for a breath of fresh air when Peter pulled out a cine camera.

‘Wow!’ said Paul. At four he didn’t quite understand it, but was impressed by all the buttons.

‘Hey, I know,’ said Peter with a huge grin. ‘Why don’t I take a film of both of you, eh? You can act, can’t you? Be fun to see yourself like in the movies!’

Mum and Dad laughed as Peter concentrated through the viewfinder, and Paul and I sprinted off, dancing hand in hand. I was in a light green dress with big sleeves that made me feel girly for once, despite my cropped hair.

That afternoon, Peter captured a rare moment: us, a happy family on film. As our mum and dad held hands, watching their giggling children playing in the fields, for half an hour we were genuinely a family.

Chapter 2

‘In the Picture’ (#u8c3278d8-cde6-50c1-809b-e54a04f9df02)

Paul

The summer before I started school, Peter came over, a camera slung around his neck like always. Peter went to chat with Mum in the kitchen and we overheard him.

‘We’ve got more rabbits than you can imagine. Would Terrie and Paul like to come over and choose one?’

I leapt up and down excitedly, clapping my hands with Terrie. Dad didn’t like pets, but he hadn’t been home for weeks, so maybe we could persuade Mum? We both ran out to the kitchen. The excitement must have been showing all over our faces.

Mum sighed, looking at us both. ‘I guess you heard Peter’s news.’ She paused. ‘All right, let’s go and see them this afternoon.’

Terrie and I leapt up and down cheering, and Sam joined in, barking loudly.

Peter drove us to his house later that afternoon. It was bigger than ours and had cats everywhere, on every chair, surface and floor.

‘It’s like a cattery in here,’ laughed Peter. ‘Would you like a glass of orange squash, kids?’

‘Yes please,’ we chimed in unison.

We sat at a table sipping our drinks and nibbling a digestive biscuit Anne had offered from an exciting-looking tin. Terrie was pulling funny faces at me while the adults were busy talking. I tried not to laugh as my mouth was filled with squash, but I choked and sprayed squash all over the table.

‘Paul!’ I heard Mum scold.

‘It’s okay, Cynth,’ Peter said, smiling at me, ‘he’s just excited. Maybe we should go out into the garden.’

I held Terrie’s hand as Peter led us outside into his big grassy garden with a fence around it. There was a small open enclosure in the middle and there were baby rabbits of all colours hopping around. Peter lifted us over and we crouched down. I couldn’t believe how small they were.

I felt really excited and I tapped Terrie’s arm. ‘Can we choose one?’ I mouthed silently.

‘I think so,’ whispered Terrie back.

We started gently stroking them as they jumped past, nibbling grass. My eyes quickly scanned every bunny. I wanted to find mine.

Terrie fell in love with a beautiful fluffy black one. I had my eye on a grey speckled one that was snuffling at my finger. I giggled as the whiskers tickled me.

As we fussed over them, Peter appeared with his camera. Click, click.

‘Hey kids, smile for the camera!’ he said.

Proud in my favourite Superman T-shirt, I gave him my best grin.

After about an hour of deciding, we finally picked our bunnies. Terrie named hers Sooty and mine was Smokey.

Mum couldn’t thank Peter enough. ‘You’re so kind,’ she said repeatedly.

Peter ruffled the top of my head.

‘You’re more than welcome, Cynth.’ He smiled down at us both. ‘The look on these twos faces makes it worth it.’

Peter also gave Mum the things we’d need: a small hutch, sawdust, food, hay and a drinking bottle each. We excitedly set up our new pets’ home that afternoon.

They were so gentle, and soon grew used to us picking them up and stroking them. Every morning I jumped out of bed and went to poke grass through the wire of the cage as a treat. Then I sat and cuddled mine, rubbing my face against Smokey’s silky fur.

A few months after we’d got our new pets, something was wrong with Smokey. He was trying to hop, but looked lopsided. I gently picked him up, but he didn’t want to eat any grass and looked miserable.

‘Muuuuum!’ I cried, calling her to look.

‘Hmm,’ she said, looking upset. ‘He needs to go to a vet.’

We walked to the local vet, carrying Smokey in a box. The vet took one look at his leg and shook his head.

‘He’s broken it,’ he said.

‘What?’ gasped Mum. ‘How did he do that?’

The vet asked if we’d dropped him recently from a height or grabbed his leg in some way. Mum said absolutely not. The vet shrugged and plastered the leg up.

Mum was quiet on the way home. ‘Are you sure you haven’t been too rough with Smokey?’ she asked.

I was completely confused about how Smokey had done this. I kept thinking, maybe it was something I’d done.

My first day at school was traumatic as I hated leaving Mum. The thought of spending all day long without her was too hard and I cried so much in the classroom she had to come and get me. On the second day I was given a pedal bike to race around on in the playground, but when no teachers were looking I pedalled straight out of the gate and home.

‘What’re you doing here?’ asked Mum, her eyebrows shooting up to her hairline.

‘I don’t like school,’ I said simply.

She let me have that afternoon off, but in the morning I was back there. I found it hard to make friends and preferred sitting under a tree or hanging out in the dinner hall, instead of playing tag, or hopscotch or skipping.

My name didn’t do me any favours either. ‘Duckett, Duckett, there’s a hole in my bucket,’ kids chanted in the playground if I did dare show my face.

Kids always found it easy to be mean about me. From my scuffed shoes to my second-hand uniform that didn’t fit properly. Even the two slices of bread and butter I brought for lunch made kids laugh.

‘Is that it?’ taunted one little boy, waving a packet of crisps and a Wagon Wheel at me, as he tore off the plastic wrapper of the chocolate biscuit and stuffed it into his mouth.

‘Mmmhmm!’ he smiled, chomping into the chocolate.

I looked at my soggy white bread and nibbled it miserably. At least I’m not going to be a fat fucker, I thought to myself.

Mum always did her best, but you don’t get a lot of choice when you don’t have money. Thankfully I started getting free school dinners and quickly learned that making friends with the dinner ladies was the way forward. I loved any food. Lumpy custard with the skin on top was a treat to me.

‘Can I have more, please?’ I beamed gratefully, as an extra spoonful slopped on my plate.

‘You’re a good boy,’ said the kindly dinner lady. When no one was around I’d get slipped an extra biscuit too; coconut ones with a cherry on top were my favourite.

Having dinner ladies as allies made up for the fact I didn’t have many others. While the girls always refused to let me play kiss chase, teachers were more likely to appreciate the nice side of me. I could think up things to get myself out of most sticky situations too.

One escape from school and home was my Nan and Pap’s. It was always warm and welcoming, full of hugs, kisses and food, unlike our own. Here I felt loved and normal.

Pap had worked in a shoe factory all his life while Nan kept the house, but she used to tell us all her stories about life in the munitions factory, or when she watched Coventry burning down in a huge bombing raid while close by in the park called ‘The Racecourse’.

I could tell Nan loved me by the way her face softened as she looked at me, and how she looked after me and made sure I was never hungry in her house.

‘We need to fatten you up, Paul,’ she’d frown worriedly. ‘You’re all skin and bone.’

Nan piled my plate high with favourites like bacon and onion roly-poly, or a dish that was pastry over meat, gravy and veg; I never knew what that was called. Ground rice for afters. Me and Terrie would eat until our stomachs hurt. And Pap was a whiz at making wine; he’d joke he could make anything from the sole of his shoe to potato, raspberry, rose hip, blackberry or any fruit he laid his hands on.

Mum adored her parents as much as we did. Sitting around that table with all of them was the place I felt safest in the world. One person who never came join us there, however, was Dad – something both me and Terrie were glad about.

Dad’s own parents, Nin and Bill Duckett, didn’t have any more patience for us than he did. They lived just up the road from Nan and Pap, but they couldn’t be any more different. When we popped around there we often saw our cousins Nicky and Claire, Dad’s sister Ruth’s kids, but we all stayed out of Pap’s way. He sat by himself in the living room, barking orders at Nan for food or drink. Nan had a terrible temper, too; however, she would at least give us a biscuit when we arrived and she never ever left us alone with Pap Duckett either. Not for a single second.

At the end of November 1979, Dad came home from another working jaunt. For once he came through the door with a proper grin on his face.

‘We’re going to South Africa on holiday,’ he announced. ‘It’ll be for four weeks over Christmas.’

We both jumped up and down with real excitement. This wasn’t something the likes of our family ever did. It seemed too good to be true!

We flew out to Johannesburg and caught a train to Kimberley. It was all scary yet exciting. We stayed with Dad’s friends Kevin and Sylvia, who had two kids, James and Anne, a bit younger than us. They showed us the sights, including a diamond mine that completely captured my imagination as we watched the glinting metal sparkle on conveyor belts through metal fences.

Despite being on holiday, Dad was meticulous with time keeping. He was like this at home and now we were away he arranged a very strict schedule. We were up every day for breakfast at 7.30 a.m. on the dot, then out the door by 8 a.m. Dad would time how long everything took. While visiting a museum about the Afrikaaners Dad tapped his watch at the entrance and looked us all individually in the eye.

‘You have precisely 40 minutes to look around,’ he said.

It wasn’t just schedules Dad liked to stick to; the way we looked was important too, despite our hand-me-downs.

‘It’s not acceptable for girls to slouch or have dangly bits of hair in front of the face, Terrie,’ he told her, pulling her shoulders back and yanking back her fringe. ‘And when you speak, speak up clear and loudly so we can all hear.’

So her fringe was kept neatly pinned back, and whenever I walked past Dad I’d square my shoulders a little more.

All too soon, we had to go home. Dad was in a foul mood on the trip back. He had been ill most of the holiday. When we arrived back in England, everywhere was covered in snow. Dad didn’t talk all the way home. Terrie and me slept most of the way back. As soon as we arrived home we were sent straight to bed. It was so cold.

In the morning Mum said Dad had gone to Portsmouth for work. A few weeks later, when it was the half-term holiday, Mum told us we were going to go and visit him. We had to catch a coach. My insides just clenched at the thought of a coach. I got terribly car sick on the shortest journey and knew I’d end up throwing up on a two-hour trip.

We packed a small bag and set off. I sat next to Terrie. She seemed miserable.

I tried to cheer her up. I patted the seat with my hand. ‘Look, bum dust.’ I giggled as a cloud of dust erupted from the seat.

She patted her seat, laughing hard. ‘Fat bum dust.’

Soon we were lost in laughter and patting seats, when Mum leaned over from behind.

‘Pack it in, you two,’ she hissed menacingly. ‘Just sit quietly.’

‘Yes Muuuum,’ we chimed in unison, grinning cheekily.

I turned to look at Terrie. She was doing her best not to look at me. I knew all I had to do was catch her eye and she’d start laughing again.

I closed my eyes, trying to sleep, to escape the waves of nausea. I could feel the bile rising just 20 minutes after we set off.

‘Oh, not again, Paul,’ Mum said as I turned green.

She stood up, wobbling and holding onto seats as she made her way to the driver. ‘Excuse me, but my son is going to be sick,’ she said.

The driver half turned around.

‘Oh,’ he said. ‘Right, well, grab that newspaper by the side of my seat and make him sit on it.’

‘Eh? Sit him on the newspaper?’ quizzed Mum with a puzzled look on her face.

The driver gave a laugh. ‘Yeah, I don’t know why, but it does often stop people feeling sick.’

Willing to try anything, Mum picked up a few sheets and came back.

‘Pop this under you, Paul. The driver says it will stop you chucking up.’

She pushed it under my bum. I struggled, thinking I would look silly and not believing for one moment that the paper would make me better. However, the next thing I remember is waking up, having dozed off, the sickness passed as if by magic and I felt much better. When we arrived in Portsmouth we had to stand and wait a few hours before Dad’s friend Gerry picked us up.

‘Sorry, Cynth.’ He looked embarrassed.

He took us to the house where Dad was staying. A few of the construction men rented the place between them. Dad was sitting at the table; he nodded at us both and handed us 50p each. ‘Go and entertain yourselves until six.’

Terrie had to check her watch was wound up and said the right time. We both then turned and walked down the hallway. On the way out we had to walk past a big glass bowl full of 10ps and 50ps. I looked at Terrie and she raised her eyebrow as we both had the same thought: 50p wasn’t going to last us eight hours. We’d be starving by the time we got back. Terrie grabbed us a handful of change each and we scurried out of the door.

Side by side we set off for the seafront. First stop was the sweet shop. We filled little white bags with sherbet pips, jawbreakers, fruit salads and chewy peanuts. Then we walked to the seafront 15 minutes away and sat down and gorged ourselves. Next, we went roaming on the rocks, grabbing tiny crabs with our hands and chasing each other. We took off our shoes and socks, rolled up our trousers and ran along the sea edge, splashing each other with the cold salty water.

‘I’m cold, Terrie.’ I was shivering; I’d got wetter than I had intended. I was also feeling hungry.

‘Me too,’ agreed Terrie.

We sat on a bench and shared some hot chips. Then we spent the afternoon playing in the amusement arcade.

‘Time to go back, Paul,’ Terrie said resignedly, looking at her watch. She knew I felt the same and squeezed my hand harder as we trudged back. This time the house was quiet as we turned up. No yelling; that was good.

But as soon as we walked in, one look at Mum, her face red and swollen with tears, told us the visit wasn’t going well. Terrie led me off to our room and we quickly got changed. Dad took us to his favourite Chinese restaurant for dinner, but told us we were only allowed crab and sweetcorn soup.

As the pretty Chinese waitress showed us to our seats she looked a bit confused. ‘Hello, John,’ she smiled, bowing. ‘And Karen …?’

Mum visibly bristled, glaring at Dad, as we were ushered to our seats with Dad trying to laugh it off.

I’d heard of Karen a few times by now, but I still had no clue who she was.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/terrie-duckett/stolen-voices-a-sadistic-step-father-two-children-violated/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Terrie Duckett

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 28.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: He beat them, he abused them, and he tortured them. He broke their dreams. But they came back stronger.‘Terrie and Paul are two of the bravest people I have ever met. I have only shared the briefest glimpse into the true horrors this brother and sister have endured, but I rarely come across cases this bad. After the unspeakable abuse and shocking betrayals, two incredible human beings came through – to inspire us all.’Sara Payne OBE, co-founder of Phoenix SurvivorsTerrie and Paul’s step-father had been living with them for six months when the abuse and grooming began. What started as innocent conversations and goodnight kisses quickly developed into something far darker and depraved.Everyday Terrie was assaulted and abused; her rapes were photographed, filmed and shared. Paul was regularly taunted and mercilessly beaten. But despite the bruises and the scars, and the desperate pleas for help, no one saw their pain.But through it all they stuck together, battling for their childhoods for over a decade and masterminding creative ways to outwit their stepfather and buy themselves fleeting moments of joy.In March 2013, thirty years on, Terrie and Paul made the brave decision to give up their right to anonymity to tell of the years of abuse they endured at the hands of their recently convicted step-father and raise awareness for the ongoing battle for justice for victims of child abuse. A powerful testament of what can be achieved through courage and love, this is their inspiring story.