Matt Dawson: Nine Lives

Matt Dawson

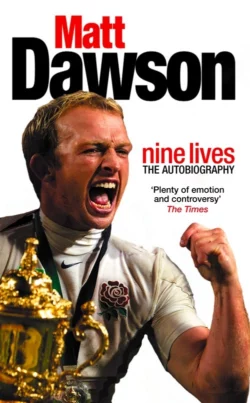

The most capped England rugby scrum-half of all time, a captain of his country, and a two-times British Lions tourist, Matt Dawson’s career story is a colourful tale spiced with controversy, from club rugby at Northampton to England winning the Rugby World Cup in Australia.The boy from Birkenhead learnt the game the hard way, working as a security guard and an advertising salesman in his formative years, in the days when rugby players found relief in an active and alcoholic social life. (Dawson: ‘The drinking started on Saturday night, continued all Sunday and most nights until Thursday.’)Despite the frequent visits to the operating theatre and the physio’s table, hard graft for his club Northampton eventually heralded international recognition. Dawson talks about the influential, and occasional obstructive figures in his blossoming career: the likes of John Olver, Will Carling, Ian McGeechan and, more recently, Wayne Shelford, Kyran Bracken and Clive Woodward.In typically opinionated mode, he also reflects on the successes and failures of the England team and, famously, the Lions in Australia in 2001. After speaking out against punishing schedules, disenchanted players and lack of management support in a tour diary article, Dawson was almost sent home in disgrace. He revisits that bitterly disappointing period in his life and is still not afraid to point out where everything went wrong.Following England’s Rugby World Cup 2003 success, Dawson provides a first-hand account of all the dressing room drama – including a troubled Jonny Wilkinson – and the memorable final itself, followed by the stunning reaction to this historic win back home. And in a new updated chapter for this paperback edition, he reveals how the World Champions have overcome the retirement of key players, reviews the 2004 Six Nations, and looks at his own future in the game.

MATT DAWSON

nine lives

THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY

with ALEX SPINK

To my late Grandad Sam. I know you’ve been watching Grandad, and I hope I’ve made you as proud as the rest of the Dawson–Thompson clan. We never did find that eight iron!!!

Contents

Cover (#ufe106c77-3c6f-5bda-a308-50d6eb0d40b9)

Title Page (#ud15d4193-288f-55fa-952f-638e8d84f912)

Prologue (#ulink_f4546a1b-b9dc-594b-9a23-a2ba35983f6b)

1 Growing Up (#ulink_9b9919ce-b92a-5ddb-b5be-13858019b778)

2 Losing Ground (#ulink_3f2c3573-c844-55a5-96d0-c77408d02a8d)

3 Return of the Artful Dodger (#ulink_698aafe5-aee5-5d80-8fef-f3a94d739e80)

4 Heaven and Hell (#ulink_d2edff2d-c698-5b3f-a360-6524338fab78)

(i) Lion Cub to King of the Pride (#ulink_d2edff2d-c698-5b3f-a360-6524338fab78)

(ii) The Making of a Captain (#ulink_37c1fb2b-31eb-5cfd-bcff-d7b95db84a12)

5 Misunderstood (#ulink_b7661744-7529-502e-82bc-90c88aadc26f)

(i) Hate Mail, Hated Male (#ulink_b7661744-7529-502e-82bc-90c88aadc26f)

(ii) Striking Progress, Strike in Progress (#ulink_3880640d-9026-5e55-a65a-b2cf21b3ac87)

6 Foot in Mouth (#ulink_61659f93-c87c-52b6-acb1-ab856dbcff2c)

7 Going Off the Rails (#ulink_684e7736-4b9a-50b7-adc5-deeec54782c8)

8 Headstrong to Humble (#ulink_8573bdf8-caff-5b91-b24b-948d1dde4b85)

(i) Bashed by the Boks (#ulink_8573bdf8-caff-5b91-b24b-948d1dde4b85)

(ii) Grand Slam at Last (#ulink_e89a4f6c-f744-56f2-bda9-0c7301be6670)

9 Shooting for the Pot (#ulink_8fc83a40-add9-565a-aacd-bca2ebfd70a5)

(i) History Lesson Down under (#ulink_8fc83a40-add9-565a-aacd-bca2ebfd70a5)

(ii) The Greatest Day of All (#ulink_5eeaea33-ff71-529c-bc55-f49e7d5dd0da)

10 Celebration Time (#ulink_7d46e1fa-cf58-52f6-aafe-2b2e628507f6)

11 A Step into the Unknown (#ulink_77019df7-435a-569b-a45f-4e1a0f07a16c)

Plate Section (#u3ed48d2a-7f59-56c2-9f8d-f71c5b6309fc)

Career Statistics (#ulink_71c6a172-cb65-5b76-a47b-39f6b340c60c)

Index (#ulink_c23117a4-6bcf-5eb7-a829-90e74c341103)

Acknowledgements (#ulink_2b16cfa7-6ec9-5e54-a4e6-eefc45dfb811)

Copyright (#ulink_a0b44859-f0a2-5b57-b206-18a5af5f7c64)

About the Publisher (#ulink_fa814d7d-9a3d-5868-ad3f-3bf32bf963a2)

Prologue (#ulink_8614abdf-de14-58d9-8088-374c44ad5b55)

Kick it to the shit-house …

That was the last thing I remember saying before the whistle blew, before I dropped to my knees, before my life changed forever.

There was no time left on the clock inside the Olympic Stadium, my very own theatre of dreams. Extra time had come and was now gone. We just had to get the ball out of play. It came to me and I flung it to Mike Catt: the ball and that less than eloquent line.

Paul Grayson, my best pal, got to me first. We shouted and screamed at each other as the raw emotion of the moment took over. I looked up into the stand to where I knew Mum, Dad and my girlfriend Joanne were sharing our joy. For a moment I was overwhelmed. It had been a long journey to the summit and the realisation that I had finally arrived stole my breath away. Almost exactly a year ago to the day I had been told my career was over due to a neck injury. Yet here I was on top of the world.

If there really is a place called Heaven on earth then I was there. I floated over to the end of the stadium occupied by the thousands upon thousands of England fans. They were singing my song, Wonderwall by Oasis. Well, of course they were. I was in dreamland. I stood in front of the bank of white shirts conducting the singing and mouthing the words along with them. ‘Sing my tune, baby,’ I yelled, as though I was on stage at Knebworth. I could see nobody I knew but I was picking people out – watching them cry, watching them hug each other – and revelling in their joy.

‘Suck it all in,’ I told myself. ‘Remember what you are seeing, remember what you are hearing. Lock away these images forever.’ It was awesome, simply awesome. It also seemed too good to be true. Because for as long as I could recall, my rugby life hadn’t been like this. For me, and those who care for me, there had been a lot of rough to go with the smooth.

I have won two World Cups and a host of titles with England but am still remembered for being captain of the side which ‘snubbed the Princess Royal’ when we didn’t go up to collect the Six Nations Cup after we had lost at Murrayfield in 2000.

I have not only won a series with the British Lions but scored the try which some say was the defining moment of our triumph over South Africa in 1997. Yet it sometimes seems I am as well known for the Lions diary I wrote in the Daily Telegraph four years later in Australia.

I have spent 13 years with Northampton, helping them to four cup finals, yet was never offered the captaincy and was instead rewarded for my loyalty by being hauled in front of an internal disciplinary committee after a nothing incident in the 2002 Powergen Final, and then effectively forced out of the club in the summer of 2004.

Through it all I have never given anything but my best, and yet it feels my motives and I have often been misunderstood. I have been called arrogant and worse. I have been upset by it, I have come close to chucking it all in. But I have also learned from it and, I think, become a better person for it.

‘Gradually,’ my mother said recently, ‘people are realising that Matthew is not the arrogant sod he appears on the pitch.’ Thanks for that, Mum. Seriously though, it has taken a lot of effort. And I admit that I have not always helped myself because I have not always let people in.

About 18 months before the World Cup I decided to do something about it. Fined by the Lions, dropped by England, in the doghouse at Northampton and out of love in my personal life, I was pretty close to rock bottom. I was completely miserable. Inspired by Wayne Smith, the new head coach at Saints, I arrived at the conclusion that if people didn’t understand me I would work harder to help them get to know me. Smithy told me that while it probably was no more my fault than that of other people, I needed to be the one who went out and made more of an effort.

A team-mate had described me as a lost soul who seemed happier away from people. Goodness knows what others were thinking. I had been neglecting my family, to the point where I could not be bothered to pick up the phone and speak to Mum and Dad and see how they were, or to tell them when I was injured. My attitude was that they would find out soon enough on teletext.

I like people to be comfortable, but I hadn’t made the effort to make those around me feel that way. Fortunately I realised before it was too late. Fortunately those around me stuck by me: my family, my friends – particularly Paul Grayson and Nick Beal – and my girlfriend Joanne. Which is why as I stood in the middle of the pitch inside the Olympic Stadium, my thoughts were not for me and for what I had achieved. The medal around my neck was for all those who had contributed to getting me there.

My story is a tale of ups and downs, of triumph and despair, of happiness and sadness, of being revered and reviled. Looking back it feels like I have lived nine lives, rather than just the one. But I wouldn’t swap it for the world; nor the people around me.

1 Growing Up (#ulink_fed4cb36-1eac-5baf-b548-49d25e6e4743)

They didn’t hear the first knock. The radio was on and Dad was up a ladder. Mum was up to her arms in wallpaper paste, her stare locked on the pattern taking shape before her eyes in the upstairs bedroom.

It came again. More urgent this time. Ra-ta-tat-tat. Dad looked at Mum for a clue as to who it could be. We had only been in the house a week. We didn’t know anyone. Mum crept to the window and peered down. All of a sudden she froze.

‘Oh my God, Ron. It’s Matthew.’

Dad shot down the stairs to the hall where packing cases stood piled on top of one another, still half full after the move south from Birkenhead to Blackfield in Hampshire, where Dad’s new job had brought us. He opened the front door, and there, standing on the doorstep in front of him, was a lad wearing a motorcycle helmet. But this was no pizza delivery; in his arms was a distraught five-year-old. Me.

Our new home was at the end of a little lane on the edge of the New Forest. The day was warm and bright, and my sister Emma and I had been playing on our pushbikes up and down the leafy lane. You could not imagine a safer place to be. At least until the scooter hit me.

The shaken rider handed me over to Dad. I had a broken collarbone and a gashed head. He was all apologies, insisting I had come out of nowhere and he’d had no time to react.

By now Mum, who’d followed Dad down the stairs, was frantic with worry. As we were new to the area neither of my parents knew where the hospital was. Still, they laid me across the back seat of the car and set off, hazard lights flashing and Dad waving a white handkerchief out of the driver’s window. It must have been quite a sight, as must the expression on Dad’s face when we arrived at the local hospital in Hythe to find a notice pinned to the entrance which stated that they were shut and that we needed to go to Southampton, a further half an hour away.

We laugh about it now, particularly at the memory of the lad on the scooter returning to our house a week later to present me with a Tufty Road Safety board game. But it was not remotely funny at the time. My career could have been over before it had even begun.

I was born to Ron and Lois Dawson on 31 October 1972, and almost from the day I arrived kicking and screaming into the world at Grange Mount Hospital in Birkenhead I was a worry to them. They did not know then that I would go on to have lumps knocked out of me for a living, but based on the early evidence they might well have guessed. As a toddler I never used to walk anywhere; I was always running around on my toes and falling downstairs. One day I tumbled into a wrought-iron gate and emerged with a lump on my head and the clearly visible imprint of one of the gate’s bars. Another time, I got a wine gum stuck in my throat and stopped breathing.

Dad worked shifts at Mobil Oil, and my problems always seemed to come in the evening when he was away on the two till ten beat, so it was Mum who often had the traumatic task of scooping me up in one arm while using her free hand to point Emma, three years older than me, in the direction of the car for yet another mercy dash.

He was at work the day I performed a disappearing act which so alarmed Mum that she called in the police. Mind you, I was only two and a half at the time. She had left me playing barefooted with my first girlfriend, Elspeth, on a patch of grass at the end of the cul-de-sac in which we lived. But by the time she next turned round to check on us we’d decided to walk to our nursery school, through the estate and up and over the main road using the footbridge. Mum swears she realized we were missing within seconds of us leaving. Whatever the truth, she had the police around pretty smartish. They searched our house and then Elspeth’s before combing the neighbourhood, eventually spotting the two of us walking hand in hand on the other side of the main road.

Mum nearly suffocated me with her hug when she got me home. Then she lost it a bit. She was embarrassed that so many policemen had been called out to look for me. And there was another reason for her red face: her dad, Sam Thompson, was a chief inspector with the Birkenhead Police. The following day, Grandad went into work to find a note pinned to the noticeboard with his name on it: ‘Would C.I. Thompson please keep his grandson under control and stop providing extra work for half the Birkenhead police force!’

It didn’t get any easier for Mum and Dad as I grew older. Two days before my seventh Christmas Mum was wrapping presents in the upstairs bedroom when I charged through the door with my best friend, Spencer Tuckerman, in tow to ask if we could go sledging on a snow-covered slope down the road. So keen was Mum that I didn’t see my unwrapped gifts that she nodded straight away, without thinking through the possible consequences. Half an hour later, Spencer’s mum was on the phone. ‘Lois,’ she said, ‘bad news I’m afraid. Matt’s had an accident. His face has been run over by a sledge.’ Mum arrived at the scene of the head-on smash to find Mrs Tuckerman crouched over me trying to hold my nose together and staunch the flow of blood. I was once again rushed to Casualty where I had to have 16 stitches.

In a desperate attempt to keep me out of mischief, if not harm’s way, Dad turned to rugby union, the sport he had played as a centre for the Old Boys team at Rock Ferry High School during his younger days in Birkenhead. He took me along to the Esso Social Club where a shortage of lads of my age resulted in me being thrown in with the under-10s. I was very small for that age group, so in an effort to make me look mean Dad wrapped a towelling bandage round my head. They then stuck me out on the wing in the hope that I wouldn’t get involved too much (Mum still thinks that’s the best place for me during a match).

I enjoyed the rugby, but I also loved football, which I started playing when we moved to Marlow in 1980, and it was the only sport on offer at the Holy Trinity primary school. My grandfather on Dad’s side had played for Garston Gas Works, later to become Liverpool. I supported Everton. I continued to play rugby on Sundays at Marlow RFC, where Dad coached me (he’d initially just come along to watch, but after a while standing on the touchline someone asked him to help out; he agreed, he worked hard for his certificates and coached for the next 11 years), but football was my main love and before too long I was picked up by Chelsea Boys. A Chelsea scout had seen me and Spencer playing locally for Flackwell Heath, and the pair of us were invited to play for the baby Blues. To this day, Spencer’s dad, Alec, is convinced I would have gone all the way had I stuck with it. I was a right-back, ‘fearless yet quite skilful at the same time’ in Alec’s opinion – which, of course, I value. The reports coming back to my parents also suggested I had a good chance of making it. I was very dedicated and I wanted it badly.

But by that time I had left primary school and started at the Royal Grammar School, Wycombe, where rugby was the main sport, and I had only played a handful of games for Chelsea when I got the nod from RGS that I needed to concentrate on my work and rugby rather than go to Chelsea twice a week. I was reluctant to give up football, though, even when Dad told me I had more chance of making it in rugby because ‘every kid wants to play football’.

As far as I was concerned, it wasn’t as simple as that. I was a typical teenager and I wanted to break away from Dad’s rugby coaching. We got on, but we were often at each other’s throats. ‘God, why are you always having a go at me?’ was the sort of attitude I’d quickly developed. He worked so hard, getting up at five o’clock every day to fight the M25 en route to either Heathrow or Gatwick and not getting home until seven or eight o’clock in the evening. And then he would have me to contend with. I had no appreciation at all for what he was trying to do for me. On Sundays I just wanted to enjoy myself playing, but he was the coach and we did things his way. It always seemed to me that he spoke to me in a way he didn’t to the other boys. Whenever I’d had enough of it I would walk off and tell him to leave me alone; he would then get angry with me. Football, however, was a totally different experience. Mum would come and watch while Dad was busy with the rugby team.

My cause with Dad was not helped when I was arrested for petty theft. I was kicking around with a dodgy bunch of boys who were teaching me bad habits. One was that you save money if you don’t pay for goods. So there I was in a shop on the high street in Marlow, stuffing one of those party streamer sprays into a pocket in my jeans, when I felt a tap on my shoulder. The two lads I was with bolted out of the shop and got away but I was banged to rights. The police were called, and I was ushered into the back of their car and driven all of 200 yards down the road to the police station. I thought the world was going to end. Mum, who was working part-time at the local post office, got the call to come and get me, and I felt so ashamed that I could not look her in the eyes.

I was given only a warning by the police, and was grounded by Dad, but neither hurt me as much as the reaction of Mum, the daughter of Chief Inspector Thompson, someone I had an unbelievable amount of respect for. ‘What is your grandfather going to think?’ she sobbed. She made me feel about two feet tall. In fact, the experience would haunt me for years. When I turned 18 I applied to join the police force but panicked when the application form asked for any previous convictions. It was only when Mum and Dad assured me that I didn’t have a criminal record that I put it in the post. (In the end I was turned down on medical grounds as I had just undergone a knee operation and they felt I wasn’t fit enough.)

Being grounded was an annual feature of my childhood. I would take my summer exams, my report would follow me home on the last day of term and my first week’s holiday would be spent paying for my poor results alone in my room.

‘This is not good enough, Matthew,’ Dad, it seemed, always said on opening the envelope. ‘You’re grounded. Go to your room.’

‘Right. Whatever.’

I was under orders to read for an hour each morning, but that was way beyond my powers of concentration. So I waited until my parents had both left the house for work and then jumped on my bike and went to meet my mates. It required military precision to get back home, return the bike to exactly the same position I’d found it in the garage, then to jump onto my bed and open the book 50 pages on from where I’d left it before Mum’s car turned into the drive.

As I got older I gradually began to realize what a fool I was being, in my rebellious attitude towards Dad in particular. He was my biggest supporter; nobody wanted better things for me than him. But that realization took time to dawn on me; initially I agreed to go back to rugby only if he stopped coaching. With time, though, I welcomed his support and indeed sought his approval, even if his vociferous backing wasn’t to the liking of everyone. In assembly one day at RGS he was named and shamed for over-exuberance on the touchline during a school match. I was so proud of him. I thought it was hilarious. It was the one and only time my name was read out during assembly without me being told off as a result. On another occasion he was warned for shouting at a referee. He liked to tell them why they were wrong (and you wonder where I got it from!).

When I played rugby during my teenage years I could always hear Dad’s voice. Whenever I passed the ball from the base of a ruck I’d hear him bark, ‘Follow the ball!’ I would have thought something was wrong had I not been able to pick out his voice. And, being a coach, his enthusiasm extended beyond the playing field, so keen was he that I got the most out of myself. When I was selected for England 16 Group Dad felt I was too much of a couch potato at home, so he organized ‘training’ sessions in our back garden. He would try to get me doing press-ups and shuttle sprints. I would go out for five minutes to humour him, then return to the sofa. Happily, certainly from Dad’s point of view, I became more committed once I turned 17. Two or three times a week I would go on an eight-mile run, up to the M40 roundabout, back down a little lane, then all along Marlow Bottom. I’d get home from school, change into my kit and set out. The best times were always in the summer when I could wear a vest and run past the girls coming home on the school buses. It was both a pleasure and a pain.

Dad wasn’t the only guiding light during my formative rugby-playing days. From the age of 13 through to the first XV my coach at RGS was Colin Tattersall, and he had a huge influence on my game. We were a successful school side, losing only two or three games a season, but when I was in the sixth form we played against hardly any public schools. They wouldn’t take our fixture because we were a state school, albeit a very good one with a strong set-up. That has since changed. RGS now plays against the likes of Radley, Millfield and Harrow, but at that time we only got to play against those sides in the Daily Mail Cup.

It was probably a good thing that I showed promise in sport because my academic accomplishments were average, as most of my tutors never tired of telling me. How I ever got into the Royal Grammar School in the first place I will never know. We had to take a 12-plus to secure a place, and how I passed that remains a mystery to me. Me and exams don’t get on. To this day I hate the words ‘exam’ and ‘test’. I managed to scrape four GCSEs first time round, adding another four later on, but I failed all my A levels, primarily because I was away playing with the England 18 Group for six to seven weeks during the lead-up to the exams. I came back not much more than a week before my first paper, so it was hardly perfect preparation. And believe me, I needed perfect preparation. Fortunately, the school allowed it, but mine was a poor show academically. It’s not something I’m proud of, but at that time of my life I was just not tuned in to working, be it homework or writing essays. All I wanted to do was play rugby. Or football, or snooker, or golf, or cricket …

I played all five matches for England under-18s in that 1990–91 season, forming a half-back partnership with Epsom’s soon-to-be-Irish Paul Burke. We narrowly lost to the touring Australians 8–3 at Twickenham (no disgrace as they won all 12 matches they played), but we beat Ireland, France and Scotland in successive matches, conceding only 16 points in the process. However, our campaign ended on a depressing note in Colwyn Bay when we lost to a Wales side that had been thrashed 44–0 by the Aussies. We had seemed on course for a Junior Grand Slam when we led 10–4 well into the second half, but we let them back in, gifted them a really soft try and Chris John’s boot did the rest. Wales won the match 13–10 and with it the Triple Crown.

The following season I moved up to the England under-21 side, leaving behind scrum-half Andy Gomarsall to captain England 18 Group to the Junior Grand Slam we had missed out on. My debut came at centre in a 21–21 draw with the French Armed Forces in a match at Twickenham played as a curtain raiser to the Pilkington Cup final between Bath and Harlequins.

It was my first game at Headquarters, and Mum and Dad were in the stands. They have barely missed a game since, a habit born out of Mum’s fear that she should always be on hand in case I suffered a bad injury. It dates back to when she used to make the sandwiches at Marlow. If any of the kids were injured she would accompany them to hospital in the ambulance, and the first thing they would always say to her was ‘I want my mum’, and that stuck with her. I know she’ll be an awful lot happier when I retire from rugby. She finds the whole experience torture, and it has never become any easier for her. But she feels that if she misses a game, I’ll get injured. I can only guess at the number of games she and Dad have missed throughout my career across the world – less than 10 certainly. I am unbelievably lucky, because although the majority of parents support their kids, very few do to the extent mine have. Dick Greenwood, father of Will and a former England player and coach, once told Mum that he knew exactly how she feels. ‘It’s like a little spotlight follows Matt around the field, isn’t it, Lois?’ he said. He couldn’t have put it better. Because of the position I play I am often trapped under piles of players while play carries on. Mum keeps watching me rather than following the ball, which she leaves to Dad. She feels that if she takes her eye off me something bad will happen. She doesn’t usually have a clue about how the game is going, but if I go down because I’ve got a fly in my eye, she’ll be the first to know.

All this support at times made for a difficult relationship between me and my sister. As kids, Emma and I lived very different lives. Socially we had different sets of friends: she went to a school in Maidenhead and had friends in Marlow whereas mine tended to be more in High Wycombe and Aylesbury. She saw her brother playing for England and getting the odd write-up in newspapers and her Mum and Dad following me everywhere. Looking back, it must have been hard for her, and I can fully appreciate her frustrations. I’m sure she would have welcomed some of that attention herself. It was only later, after we had both left home, that I consciously tried to make up for lost time. Emma is now married to Martin, with two children, Daniel and Ellen, and we often meet up for barbecues.

At the end of August 1991 I was invited to join Northampton Rugby Club. I accepted, and this marked the point at which my relationship with my parents changed. Up until then they were my support group; any problems I had, I turned to them. But at Northampton I met Keith Barwell, a wealthy local businessman, and he took me under his wing.

Northampton had approached me after seeing me play at scrum-half for England 18 Group against France at Franklin’s Gardens in April. When I returned from a tour to New Zealand with Marlow, it was to a message from Saints’ youth-team coach Keith Picton asking me to call him. I had already had a look at Wasps and there had been interest in me shown by Harlequins and Saracens, but I liked what I saw at Northampton.

Within weeks I was an 18-year-old commuting to the East Midlands to play for Saints under-19s. It was an expensive business, but Keith sorted me out with a job, working as a security guard for one of his companies, Firm Security. I was what is known in the trade as a ‘flyer’, which meant I had to be ready at the drop of a hat to go anywhere and offer security back-up. For example, one evening they phoned me up to say I was needed in Worcester by 10 o’clock the following morning to patrol Littlewoods.

Keith and my parents have since become the best of friends, but after I moved up to Northampton in January 1992 Mum and Dad felt a little bit left out. An awful lot of things were being sorted out for me by Keith during this period, things which parents would ordinarily do, like helping to arrange mortgages. My new place was about an hour and a half from home, which I didn’t think was all that far, but as far as Mum and Dad were concerned I could have been on the moon.

By August of that year I had moved into the head office of Firm Security and was being paid £10,000 a year. I stayed there until September 1993, when I went to work for the MiltonKeynes Herald, another of Keith’s interests, selling £15 adverts over the telephone. From there it was on to a career of sorts in teaching, a fact that will amuse my tutors at RGS who wrote me off as intellectually challenged. At the time I was sharing a house with clubmate Brett Taylor, and he was teaching at Spratton Hall prep school in Northampton. I had spent a lot of time at RGS coaching junior teams, so when an opportunity came up to help out with PE lessons and generally to be an odd-job man around the school, I jumped at it. It was obviously good for the school to have me around for the rugby and PE, but I was keen to do more, so they allowed me to teach basic geography and maths to kids up to the age of 10. I surprised myself with how smoothly it went. I got on well with the kids, made them understand the subjects and found it easy to teach them.

I was at my happiest, however, when I was outside, and one summer I was asked to strip the paint off all the school’s football and rugby posts, sand them down and then rust-coat and paint them. Many saw it as a thankless task as it was a three-week job, but the weather was gorgeous. I finished it in two months, and I’ve never been so tanned.

Brett and I, known as the ‘terrible twosome’ (or ‘pretty boys’ to Keith Barwell), were very sporty and quite fit and athletic with all the training we did. As soon as the first ray of sunshine appeared we would be out in our shorts and sleeveless T-shirts to volunteer for car-park duty. It was no chore at all. You wouldn’t believe how many mothers turned up in open-top cars, fully made up and wearing short little skirts. We of course thought we were God’s gifts to the world.

Nothing altered that view when we were roped into taking part in the summer production of a Victorian music-hall show. Our particular scene required us to pretend to be two weight-lifters, complete with big moustaches and all-in-one leotards, lifting black balloons disguised as cannonballs on the end of a weight bar. Half an hour before we were due on stage we pumped ourselves up with circuit weights and clap press-ups in the dressing room, and then covered ourselves in bronzing lotion and got fully oiled up. The looks we got from the mums as we took off our dressing gowns on stage in the music hall were truly memorable.

Life was good for me in the early 1990s, and it was about to get a whole lot better.

Defence in football, midfield in rugby. That seemed to be my fate when, after joining Saints as a scrum-half, coach Glen Ross picked me at centre. Having been selected for the bench as a scrum-half for a second-team game, I’d come on in the centre and scored a couple of tries. Before I knew it I was in the first team, making my debut at Gloucester and playing quite well in a Northampton victory.

That night, I went out with Ian Hunter and Brett Taylor and got so wrecked that I ended up sleeping in the wardrobe of a room in the Richmond Hill Hotel. The next morning I woke with a very stiff neck and rushed out to get the papers, expecting huge ‘Dawson is fantastic’ type headlines. I was rather taken aback to find no such thing. The only reference to me in any of the reports was that I had missed a 22-man overlap! But the England selectors took a more positive view, and picked me to represent the under-21 team at centre for the game against the French Armed Forces. Kyran Bracken was scrum-half that day, but this time I did make the headlines, snatching the draw by scoring and converting a last-gasp try.

I still saw my future in the game as a scrum-half though, and that summer Glen Ross set me up with a spell in his native New Zealand, playing scrum-half for a club called Te Awamutu in Waikato. I spent my first two weeks living with Glen at his place in Hamilton; then, once I’d found my feet, I moved on to a farm deep in Waikato country which was owned by Te Awamutu coach John Sicilly. Also staying on the farm were two Scots boys from Melrose, Rob Hule and Stewart Brown, and together we just had the greatest time. Every day would be spent driving quad bikes up the mountain and then erecting fences. We had this big ram hammer with which to drive in the fence posts, but I was barely strong enough to pick it up let alone ram it down.

After a couple of weeks our job descriptions changed from fence erectors to tree surgeons. John needed all his pine trees trimmed, explaining that while the top third has to be branches and leaves, the second third has to be clean so that when it gets cut there are no knots in the wood. He then sent three muppets into the forest and left us to get on with it. Ladders against trees, taking no safety precautions at all, we took massive saws and secateurs up into the branches with us. It was extremely dangerous, and every quarter of an hour or so one of us would fall a good 20 feet to the ground. But there were no serious injuries, and as the days turned into weeks my body got stronger.

Life on a farm at the end of a long single-track road miles away from civilization was simple but wickedly good. One day the three of us were driving home with John and he got to a corner where he knew there would be wild turkeys sitting on the fence. On went the headlights, the turkeys froze in the beam, and out got John with a crowbar. The next day we were instructed to dunk the carcasses in water and pluck them.

‘Why?’ I asked.

‘Try plucking one without wetting it first,’ came the reply.

I did, and within seconds there were feathers absolutely everywhere. By the time we’d finished plucking this turkey, John’s front lawn was obliterated. The wind had picked up and blown the feathers all over his house too.

‘Wet them and they stick. You can then grab them and throw them in a bag,’ he explained. ‘Got it?’

We stayed on that farm for a month, the three of us living in a little annexe. After that we moved into a house in town and went from one labour job to another. We laid a resin concrete floor in a factory one day, landscaped a garden on another. No two days were the same.

All the while I was developing as a rugby player in general and as a scrum-half in particular. I learned some hard rugby lessons in New Zealand, the most important of them never to make the same mistake twice. New Zealanders are passionate rugby people and they want you to do well, but they are very unforgiving. If you make a mistake, they’ll tell you all about it.

When Te Awamutu failed to make the end-of-season playoffs I said my goodbyes, but not before meeting up in Hamilton with the touring England B squad. I also took the opportunity to hook up with Wayne Shelford, the former All Blacks captain who was playing for Northampton but had flown home during the off-season. We went to the B Test together at Rugby Park and an amazing thing happened. As we walked into the stand and up to our seats the whole place stopped to look at Buck. Talk about a national icon.

No rugby player has impressed me more than Buck. I have played rugby with some hard men, but Buck was in a league of his own, to the point of being slightly mental. He came into the changing room one day at Northampton with really long hair tied in a ponytail, having vowed not to get it cut until Phil Pask’s wife Janice had given birth. He was late for the pre-match meet and in a hurry. He took off his shirt to change into a training top, and we saw that his back and arms were covered in scars. There must have been hundreds of them, each with a couple of stitches in. He explained that that morning he had been to hospital to have surgically removed all the bits of gristle and scar tissue that had built up over the years of his playing career. His back was like a bloody road map. It was horrendous. He then put his shirt on and went out and played.

Another time Buck played in a game against Rugby where he got the most almighty shoeing – real proper stuff in the days when a player would really get it if he was on the wrong side of a ruck. Most people would have got up and started throwing punches, but Buck just clambered to his feet, looked at the fella with the guilty feet and smiled. I swear the guy shat himself. We didn’t see him for the rest of the game. We knew Buck was just biding his time until opportunity knocked, and so did he.

That stay in New Zealand was a crucial time for me, because when I got back to England my scrum-half apprenticeship was complete. I was selected by the Midlands at number 9 and was set on a course which would soon lead me to a place on the full England bench and a World Cup winner’s medal.

‘England,’ said Andy ‘Prince’ Harriman, ‘were a scratch side who hadn’t played together before, an unknown quantity even to ourselves.’ Then he went off to collect the Melrose Cup as captain of the winning side of the inaugural World Cup Sevens. The day was 18 April 1993, and according to those present at Murrayfield, at the time the half-built home of Scottish rugby, it should be remembered as one of the greatest in English rugby. Not only was I there, I was a member of the triumphant squad.

Over the course of three extraordinary days that April the 10-man England squad lived out a Cinderella-style fantasy. Unloved and unrated, we took on the world’s best in a format of rugby barely recognized by the powers-that-be at Twickenham and came out on top. We had been given so little chance by the Rugby Football Union that they hadn’t considered it worth sending us to the Hong Kong Sevens beforehand. Unlike Scotland, who had warmed up for the tournament by globetrotting around the sevens circuit and promptly fell at the first hurdle, we just turned up in Edinburgh that spring. I wouldn’t say that we gave ourselves as little chance of winning as everyone else, but it did start out as a bit of a jolly – until it dawned on us that we were actually good enough to go all the way.

To this day, few people remember who played for England in that tournament, other than Andy Harriman and maybe Lawrence Dallaglio. It was not that we had a weak squad, because we didn’t, despite the fact that only Prince and Tim Rodber had been capped. It was more that we had relatively little experience of sevens at the very highest level. I had made the squad because I was naturally fit and could keep running all day. I could also play anywhere in the back line, as well as kick goals. Nick Beal, Ade Adebayo, Dave Scully, Chris Sheasby, Justyn Cassell and Damian Hopley completed our squad, and we were put up in the George Hotel in Edinburgh, which was the nicest hotel I had ever stayed in. I shared a room with Hoppers. There was a Playstation plugged into the television, we had all our laundry paid for, and we ate some lovely seafood. I was there for the ride really, a wide-eyed 20-year-old not really able to believe that I was playing for my country in a World Cup.

In the days preceding the tournament all the other teams seemed to be locked into the sevens mentality. We were more likely to be locked in bars. We had a bit of a tour mentality, and that was how we bonded, from the first evening when Prince declared, ‘Right, boys, we’re going out to have a good night.’ A good night? It was carnage. But when we eventually woke some time the next day we were all mates. Then, all of a sudden, we were a really good team.

In Prince we had the fastest man in the tournament and, as it turned out, its outstanding player. He was extraordinary in every way. Our training drill was one-on-one over five and ten metres, trying to step your man. Andy would be skinning people. It was phenomenal. You just couldn’t catch him. He was more elusive than Jason Robinson. Jason has very small steps, but Harriman was bang, bang, gone – big steps like Iain Balshaw, very explosive and powerful. Awesome, actually.

After the first and second days we started to believe. Drawn in Group D, we made light work of Hong Kong (40–5), Spain (31–0), Canada (33–0) and Namibia (24–5) with me playing in all but the Canada game. We lost to Western Samoa (10–28), who had come into the tournament on the back of winning the Hong Kong Sevens for the first time, but still went through to the quarter-finals, which were contested in two round-robin groups of four. We were drawn in Group 2 with New Zealand, Australia and South Africa, while Western Samoa joined Ireland, Fiji and Tonga in Group 1.

The Samoans surprisingly lost two of their three matches, the Irish pulling off a major shock by beating them 17–0 before Fiji edged them 14–12 to put the tournament favourites out. No such problems for England: we began the second phase by scoring three tries against New Zealand in the first seven minutes, through Harriman, Scully and Beal, and won the game 21–12. Against South Africa we had to come from behind following Chester Williams’s early score for the Boks, but managed it with Prince and then Hoppers crossing and Bealer converting for a 14–7 win. When the Aussies were wiped out 42–0 by New Zealand in their last game before we met them, conceding six tries in the process, the omens looked promising, but against us David Campese escaped for an early try and the Wallabies led by 14 points before we got on the scoreboard. Despite tries by Justyn Cassell and Dave Scully, we went down 12–21.

Annoyed at a result which meant Australia topped the group even though we’d both finished on seven points, we went into our semi-final with Fiji determined to regain our momentum. We decided to introduce some real physicality, and to get hard with it. Sheasby, Rodders, Hoppers and Lawrence outscrummaged the Fijians from the outset and they didn’t really react to it. We started to press them and put them under pressure, and opened up a 14–7 lead through tries by Prince and Lawrence. Fiji came back at us and threatened to draw level when Rasari went on the charge, but Dave Scully planted a spectacular tackle on the big man which knocked him backwards. The ball sprang loose and Ade put Prince away for the try which settled the issue in our favour (21–7). Dave was awarded the Moment of the Tournament for that tackle, and he deserved it.

That said, it could have gone to Andy Harriman for his opening try in the final against Australia, who had come so close to losing to Ireland in their semi before stealing victory in the last move of the match through a try by Willie Ofahengaue. Prince absolutely flew past Campo and his mates as if they were wading in treacle. It was his twelfth try of the tournament which, not surprisingly, made him top try scorer.

I was not involved in the final; instead, I played the role of cheerleader on the sidelines. And there was much to shout about as tries by Lawrence and Rodders, who outran Campo to score under the posts, extended the England lead to 21 points before half-time. It seemed too good to be true and, sure enough, the Aussies powered back after the break, scoring three tries as our legs went. Critically, though, Nick Beal had converted all three England tries, whereas Michael Lynagh managed only one for the Wallabies. After a frantic final minute in which they threatened our line again, the whistle brought blessed relief, and the small matter of a World Cup winner’s medal.

2 Losing Ground (#ulink_e6b46a39-a82a-5380-887a-fa4096409fb3)

Anything and everything seemed possible when I returned from Edinburgh in triumph with the Magnificent Seven. I was even talked about in some quarters as a candidate for the forthcoming Lions tour to New Zealand. I had never even heard of the Lions. As it turned out, that summer of 1993 I was named in the England A squad to tour Canada, and I flew out to Vancouver as first choice ahead of Kyran Bracken. With 16 Englishmen on Lions duty, including scrum-half Dewi Morris, it was an opportunity to really put my name in the frame. It turned into a nightmare.

The tour opener was a game against British Columbia in Victoria. Ahead of us were four further fixtures including two non-cap Tests, and if things went well there was always the possibility of a call-up to join the Lions (as happened to Martin Johnson when Wade Dooley came home early following the death of his father). But things did not go well. Not for me, at any rate. I had felt a hamstring twinge in training before the first game, and we were only 10 minutes in when it tore and my tour was over. Worse still, Kyran took full advantage. Although England went on to lose the first ‘Test’, they bounced back to tie the series, and Rothmans Rugby Union Yearbook was in no doubt who was responsible. Its tour review read: ‘Kyran Bracken was the only tourist who really enhanced a claim for a full international place. In the chase for Dewi Morris’s scrum-half shirt he leapfrogged Matt Dawson. Bracken’s distribution and vision in the second international definitely gave the tourists the necessary edge to tie the series.’

At the time I didn’t think too much of it. I still thought I was the bee’s knees. I returned to Northampton with Tim Rodber, whose tour had also been cut short by a wrecked hamstring, and we had a cracking time for the rest of that summer, playing golf and drinking beer. Only later did I really look back on that period as a missed opportunity. It could have been a big turning point in my career; instead, it proved to be exactly that for Kyran as his really took off.

Kyran had been to university and had done the ‘wild’ phase I was now in, so while I was forever thinking about which mate at which university I could go and visit next, he was far more tuned in to the rugby. On his return from Canada he was sent to Australia to join up with the England under-21 tour. Kyran went straight into the ‘Test’ team and scored two of England’s three tries in a 22–12 win over Australia. There was now no stopping him. A few months later, when the South-West narrowly lost out to the touring All Blacks at Redruth, he again caught the eye, and when he followed that up with another smart display for England A against the same opposition seven days later the selectors knew he was ready to step up. What they didn’t know, however, was that Dewi Morris would be forced out of the Test team to face New Zealand on 27 November 1993 with a bout of flu after he had been named in the starting line-up. As the next in line, Kyran was handed his full international debut. I was summoned on to the replacements’ bench for the first time, but by now there was clear daylight between the two of us in the rankings. I was still talking a good game, but I was half the player I had been earlier in the year. I was away with the fairies and I didn’t really understand why.

Kyran enjoyed a startling England debut. It had everything, including an England win over an All Blacks side that had gone into the game as 1/6 favourites. Kyran had his ankle stamped on after just two minutes by New Zealand flanker Jamie Joseph but refused to come off, ending the day on crutches as one of the heroes of the 15–9 triumph. Afterwards his profile was massive. All of a sudden, from having been in the box seat months earlier, I watched him sail over the horizon. He was a big star, appearing on the Big Breakfast and being pictured in the newspapers walking out of a hotel with his girlfriend. I thought, ‘Holy shit, what about me?’ Kyran was the only show in town, and it hurt. I felt that the number 9 shirt should be mine and that I should be getting all the attention. I was still a young lad and I just didn’t know how to react. Rather than earn it, I wanted it given to me. It was just an immaturity within me. I had a lot of work to do to get the shirt back, but I didn’t know how to go about it. I tried to get on with playing rugby but I couldn’t find any form. I tried to force everything, lost my way, and ended up getting dropped by the club.

And yet I’d come within a whisker of winning my first cap at the age of 21 against the All Blacks. From the moment Joseph’s boot had come down on Kyran’s ankle I’d thought I was on. I’d warmed up for the whole bloody game expecting Kyran to hobble off any minute. There is no way in this day and age he would or could have carried on; the instruction would have come down to ‘get him off’. But that day there was no budging him, even though when he did come off the pitch he was on crutches for months afterwards. At the time, I didn’t understand why he had been so obstinate, why he’d showed so much doggedness and determination. Only later did I come to appreciate what an outstanding effort it was. It was Kyran’s way of saying, ‘This is my shirt and I’m not giving it up.’ I don’t know whether he realized the sort of precedent he was setting for us both, but from that day on I knew he was going to be a major factor in my career.

It was probably a blessing in disguise that Kyran did not leave the field that day at Twickenham because I now know I wasn’t ready, in the same way that I can now admit to myself that for two years, until December 1995, when I finally made my full debut, I thought I was a lot better than I was. The season before that All Blacks match I was flying, really flying, but then I started to believe my own publicity. Even when I came back from Canada early I consoled myself with the thought that I was still the best scrum-half around. I simply didn’t realize how much work was needed. I am naturally a confident sort of person, fortunate to have been born with great self-belief. But there was probably too much an element of arrogance in my make-up when I was younger. I didn’t get the balance right.

That was how I was in 1993, riding on the seat of my pants, giving thought to only what was right in front of my eyes. So when England called me on to the bench for the New Zealand game I took it all in my stride. I wasn’t particularly nervous, because in those days you never saw a replacement unless there was a major injury, so I didn’t expect to play. I joined up with the squad on the Thursday and didn’t know any of the moves. On Friday there was a light team run. I think I probably had 30 seconds’ running, one scrum and one lineout. That was it. But so what? It wasn’t as though Kyran was going to get injured.

Come the day, cue Jamie Joseph and the instruction from England coach Dick Best to me to go down and warm up.

‘You know the moves, right, Daws?’

‘Dick, I don’t know any moves, or any calls. What’s going on?’

It would have been laughable had it not been so serious. There I was, sitting in the tunnel with Dick Best, and he was telling me the lineout calls. I was totally crapping myself. I did some stretches and nervously laughed to myself.

‘I haven’t got a clue here, Dick. I haven’t got a clue what’s going on here, mate.’

‘Don’t worry,’ said the coach of the England rugby team. ‘Just give it to Rob Andrew.’

Sometimes I wonder what would have happened to my career had I got on the pitch that day. Never mind 50-plus England caps, I would have needed a miracle to win a second. I would have been toast. That said, after the way Kyran played that day, I thought my England career might be brown bread anyway.

The first lash caught me by surprise. I was not tensed, my body was relaxed. Then he hit me again, and I cried out. Blood poured down my legs as a gang of rugby players stood around me laughing.

It had always been a dream of mine to play for the Barbarians, probably more so even than for England, because they had such an aura about them. The history of the club, the players who had worn the shirt, the great games, The Try Gareth Edwards scored against the All Blacks in 1973. Everything seemed magical. As a youngster, my black and white hooped replica shirt was my pride and joy. I wore it everywhere.

But I will not play for the Barbarians again. Not after my experience in Zimbabwe in May and June 1994. Not after what happened on that tour. Not after being assaulted by a Welshman wielding a cactus leaf.

I was very much a social animal at the time. My attitude was that all my success in rugby was purely down to natural talent and I didn’t have to work at it. Despite having lost ground to Kyran Bracken in the previous 12 months I was still a World Cup winner enjoying life to the full. I had a prima donna attitude in training as well, basically thinking that because I’d got close to an England cap it was just going to happen for me sooner or later. Lording it about Northampton on nights out with pretty girls was pretty much par for the course. I had some wild times. I was 21 years old, so who could blame me? So when the invitation arrived from the Barbarians it sounded like another good crack with another good bunch of lads, as well as the chance to fulfil a lifelong ambition to wear the shirt. There was a club tour to Chicago scheduled for the end of the season, but that wasn’t even a consideration for me.

Not too many big names went on the tour. Neil Back, Richard Cockerill and Darren Garforth went from Leicester, but otherwise the squad was mainly composed of Welsh boys, really good lads. We played three games, beating Zimbabwe Goshawks 53–9 and Matabeleland 35–23, and losing to Zimbabwe 23–21 in Harare. But my memories are not of the rugby, nor of the sights and sounds of a country I had never before visited. Rather, they are of what I took at the time to be the ‘Barbarian way’. It was a case of old boys treating us like schoolchildren. And then at the end of the tour, to top it all off, we had a session ‘in court’ which was just horrendous.

Nick Beal, one of my best mates, was also on the tour and we spent quite a lot of time together. So of course we got fined for being mates.

‘Yeah, fair enough. I’ll down half a pint of tequila.’

But that wasn’t what they had in mind at all. I was told to take my trousers down, bend over a chair and prepare to be spanked by a massive cactus leaf.

‘What? What are you talking about?’

As the youngest player on tour I expected them to have a bit of fun at my expense, even if standing in front of the whole squad with my shorts round my ankles, leaning forward over a chair, preparing to be hit by a seriously spiky object, was not exactly what I had in mind. Still, Bealer played along with it and waved the leaf close to my backside. But that was not good enough for the others. They wanted pain. Derwyn Jones, the towering Cardiff and Wales second row, grabbed the leaf off Bealer and whacked my arse. The blow cut me, blood started to ooze from my cheeks, and I exploded in rage.

‘What the fucking hell do you think you’re doing?’

My backside was full of cactus splinters and it hurt like hell. And still the ordeal wasn’t over. It was now Nick’s turn to feel the pain.

‘No,’ I said. ‘There’s no way I’m doing that. I’m the first to enjoy a bit of a giggle but no, I’m not having any of that.’

There and then I switched off. I lost interest in the Barbarians. I hadn’t minded the other stuff – the drinking games, and the Circle of Fire challenge where toilet paper is rolled up tight and you have to clench it between your bum cheeks, set a light to it and run around the room before the paper burns out. That was okay, but the cactus lark I thought was well out of order. I swore to myself there and then that I would never play again. If I was asked now, almost a decade later, my answer would still be no because I promised myself that I wouldn’t and I am a man of my word. Not only physically, but mentally I was scarred by that experience. It was very, very odd indeed. It upset me. They didn’t treat me with any respect at the time. Nick’s a little bit more forgiving, but then he didn’t get whacked so it’s easier for him to be that way. You don’t easily forgive or forget after having to lie on the bed in your hotel room while your mate pulls splinters out of your arse. I was angry, really mad. I had thought it would be good for a few photos, that everyone else would wet themselves, and that the cactus leaf would just skim my backside. But Derwyn, who was basically a good lad but due to his size was employed as ‘the enforcer’, got carried away. I didn’t want to show any pain but I couldn’t help it. There was blood running down my legs and onto my shorts.

If that wasn’t bad enough, when we got home it was a real battle to keep my Barbarians shirt. They wanted to take them all back. I couldn’t believe it. We didn’t receive a bean for going; the only reason I went was to get the shirt and to be able to say I had played for the Barbarians. I got one in the end, though, so at least I have a shirt to go with the memory.

Back in Northampton I wasted no time getting back into the swing of things, even if my backside was still too sore to plonk on a barstool. People were starting to recognize me around town, so it was always easy to be out, even on a Friday night before a game, when I would head to Aunty Ruth’s in town for a cup of coffee. But I was always out for out’s sake; my focus was not on rugby. Saturday night I would always go out to get hammered and just be a boy.

The game was still amateur in 1994, let’s not forget, and this sort of behaviour wasn’t particularly frowned upon. But, with hindsight, it hurt my career. England were preparing to change the guard at number 9; the selectors were looking for the player to take the scrum-half baton from Richard Hill and Dewi Morris and carry it into a new era. I had played in England’s two A-team victories over Italy and Ireland, yet Wasps’ Steve Bates was selected for the summer tour to South Africa. I was absolutely gutted. The alarm bells should have rung then. I should have realized that I obviously wasn’t good enough. Instead, I chose to believe it was the selectors who were at fault. Jack Rowell, the new England manager, had simply got it wrong.

Both my fitness and my attitude to rugby were slack. There was no structure to my training. I’d do a bit, but I was always naturally fit so I didn’t push myself. I was dogged and determined and brave, and because I’d cause a little bit of havoc at the base of the scrum, making breaks and scoring the odd individual try, I got more than my fair share of attention. I got away with it because I was still something of an unknown quantity, but that all changed in the 1994–95 season when the rest of the First Division wised up, saw that I wasn’t a bad player and decided to get on my case. I thought I could weather the storm, but I got battered. I was frequently injured and lost my form pretty quickly. Over the winter I needed someone in my life to say to me, ‘The 1995 World Cup is there for you if you really work at it,’ but I didn’t have a mentor on the playing side in that way until I’d formed a relationship with Ian McGeechan, who replaced Glen Ross as head coach and director of rugby at Northampton midway through the season.

I wasn’t alone at Northampton in being a prima donna; there were probably three or four of us who thought we were above it. Even to the point that we didn’t bother going to the final league game at West Hartlepool. I didn’t travel with the team; I played golf instead. I look back now and think it’s no bloody wonder we got relegated. It was a predicament all of our own making. We were a good-time club, cruising around town like big fish in a small pond. The alcohol-and-party lifestyle we led was symptomatic of an attitude problem which brought about our downfall. Because we thought we were too good to go down people failed to work on the little things which seemed minor but, when added together, amounted to a big problem. I know I didn’t work hard enough. We didn’t make sufficient effort with the supporters, or in training, or in preparation for a game. We just expected everything to happen. Nobody said how we were going to go about staying up in 1995, just that we would.

Our fate was sealed on the final day of the season when Harlequins won at Gloucester, which rendered irrelevant our victory over West Hartlepool. I saw the result in the clubhouse after finishing my round. Finally, the penny dropped.

There were a lot of very embarrassed people within the playing staff when we assembled for a meeting the following Monday, because there was no one else to blame other than ourselves. Ian McGeechan was scathing in his criticism. ‘You lot are living in a comfort zone,’ he said, and we were. It was too comfortable playing for Northampton. We had good crowds and good facilities, we were well known in the town, and we could get in as many bars as we liked. But, of course, when you’re in a comfort zone you don’t see it. It’s not until somebody comes along and points it out to you that you twig. After Geech had spoken it was the turn of club captain Tim Rodber to have his say. ‘This comfort zone disappears now and it never returns,’ he said. ‘None of us are going to walk away from this. We put the club in this mess and we are all going to get it out, right? We are going to blitz the Second Division. We are not going to lose a game. Right?’

A few days later I was sat at home, no longer so keen to go out given that the whole of the town seemed to be asking the same question (‘How the hell did you lot manage to get relegated, then?’), when the post arrived. It was my Saints’ end-of-season report, penned by coach Paul Larkin. ‘A very frustrating and eventful year you have had,’ he began.

Inevitably you must have suffered the full range of emotions, but there is always some consolation. After the previous season when you had supposedly suffered loss of form, you were able to concentrate your efforts in order that you regained your confidence as first-choice scrum-half. Frustrated with injury at least you were still able to achieve this. And despite injury, you were able to grab consolation with England A selections.

Next season you will have to contend with different problems, but if you are able to shrug off the injury doubts then you will be ready psychologically. I also feel that with Dewi Morris retiring from the England scene there is much to prove. Kyran Bracken may have the edge, but I feel that nothing is definite. You need to concentrate your efforts and work on your range of skills. That means non-stop passing practices prior to sessions and kicking drills. Because we are in the Second Division you will have to be at the top of your game to get the recognition.

Our gameplan will continue to expand next season. We must take on board the wider game through the hands; the mobility of our back row will legislate for any breakdown. You should be looking to snipe and penetrate from third, fourth and fifth phases etc. Inevitably you will be involved in the occasional back-row move to keep the opposition occupied.

The most important factor is that we are confident. Not complacent, but prepared to win through hard graft. Prepared to accept that the team will win the championship, not the individual. Prepared from the onset for every possibility.

Larkin ended his report with the words, ‘You have it all in your grasp.’

Little did I know, but in the early summer of 1995 I still had a place in England’s World Cup squad within my grasp. In March, on the same weekend that Kyran Bracken helped England to a 24–12 Five Nations victory over Scotland at Twickenham, I had been sent on a mission with England A to South Africa to check out the World Cup facilities in Durban. We played one match, against Natal, and I played the full 80 minutes in a 33–25 defeat at King’s Park. Although England opted for Dewi and Kyran as their World Cup scrum-halves, Kyran picked up an injury during the tournament which meant Jack Rowell needed to send for a replacement. I was next in line, but I was touring Australia and Fiji with England A. Jack’s Mayday call coincided with a game against Queensland during which I was boomed by a big Fijian centre and suffered major-league concussion, and as I was away at the races, so to speak, England were forced into a decision. With me out of the reckoning, they plumped for Andy Gomarsall, my understudy on the A tour.

Even though Andy would actually play no part in the tournament, I was beside myself when I heard. Fortunately that was not for a while, thanks to a combination of a friend’s sensitivity and a case of mistaken identity. Paul Grayson, my Northampton and England A half-back partner, had heard the news while I was under observation, suffering from impaired vision and various other side effects and thus unable to travel on to Melbourne with the rest of the squad. For the best part of a week he sat on it while I recuperated in Manly with Tim Stimpson, who had also left the tour having gone down with glandular fever. When we were given the all-clear by the doctors to fly home we headed for Sydney airport, only to discover that I was attempting to travel on Grays’s passport. I phoned him to say that he must have mine as I had his, and that I couldn’t leave the country. We then chewed the fat about rugby and about life, which gave him ample opportunity to say, ‘Oh, and by the way …’ But being the mate he didn’t, suspecting that I would have gone walkabout had I heard about Gomars.

He was absolutely right. It was a nightmare end to what had been an utterly forgettable season.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/matt-dawson/matt-dawson-nine-lives/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Matt Dawson

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 28.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The most capped England rugby scrum-half of all time, a captain of his country, and a two-times British Lions tourist, Matt Dawson’s career story is a colourful tale spiced with controversy, from club rugby at Northampton to England winning the Rugby World Cup in Australia.The boy from Birkenhead learnt the game the hard way, working as a security guard and an advertising salesman in his formative years, in the days when rugby players found relief in an active and alcoholic social life. (Dawson: ‘The drinking started on Saturday night, continued all Sunday and most nights until Thursday.’)Despite the frequent visits to the operating theatre and the physio’s table, hard graft for his club Northampton eventually heralded international recognition. Dawson talks about the influential, and occasional obstructive figures in his blossoming career: the likes of John Olver, Will Carling, Ian McGeechan and, more recently, Wayne Shelford, Kyran Bracken and Clive Woodward.In typically opinionated mode, he also reflects on the successes and failures of the England team and, famously, the Lions in Australia in 2001. After speaking out against punishing schedules, disenchanted players and lack of management support in a tour diary article, Dawson was almost sent home in disgrace. He revisits that bitterly disappointing period in his life and is still not afraid to point out where everything went wrong.Following England’s Rugby World Cup 2003 success, Dawson provides a first-hand account of all the dressing room drama – including a troubled Jonny Wilkinson – and the memorable final itself, followed by the stunning reaction to this historic win back home. And in a new updated chapter for this paperback edition, he reveals how the World Champions have overcome the retirement of key players, reviews the 2004 Six Nations, and looks at his own future in the game.