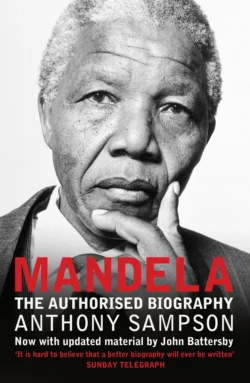

Mandela: The Authorised Biography

Anthony Sampson

Widely considered to be the most important biography of Nelson Mandela, Antony Sampson’s remarkable book has been updated with an afterword by acclaimed South African journalist, John Battersby.Long after his presidency of South Africa, Nelson Mandela remained an inspirational figure to millions – both in his homeland and far beyond. He has been, without doubt, one of the most important figures in global history. His death, on 5 December 2013 at the age of 95, resonated around the world.Mandela’s opposition to apartheid and his 27 year incarceration at the hands of South Africa’s all-white regime are familiar to most. In this utterly compelling book, eminent biographer Anthony Sampson draws on a fifty year-long relationship to reveal the man who rocked a continent – and changed its future.With unprecedented access to the former South African president – the letters he wrote in prison, his unpublished jail autobiography, extensive conversations, and interviews with hundreds of colleagues, friends, and family – Sampson depicts the realities of Mandela’s private and public life, and the tragic tension between them. Updated after Sampson’s death with a new afterword by distinguished South African journalist John Battersby, this is the ultimate biography of one of the twentieth century’s greatest statesmen.

Mandela

The Authorised Biography

Anthony Sampson

Now with updated material by John Battersby

Contents

Title Page

Map: Apartheid South Africa

Introduction

Prologue: The Last Hero

Part I: 1918–1964

1 Country Boy: 1918–1934

2 Mission Boy: 1934–1940

3 Big City: 1941–1945

4 Afrikaners v. Africans: 1946–1949

5 Nationalists v. Communists: 1950–1951

6 Defiance: 1952

7 Lawyer and Revolutionary: 1952–1954

8 The Meaning of Freedom: 1953–1956

9 Treason and Winnie: 1956–1957

10 Dazzling Contender: 1957–1959

11 The Revolution that Wasn’t: 1960

12 Violence: 1961

13 Last Fling: 1962

14 Crime and Punishment: 1963–1964

Part II: 1964–1990

15 Master of my Fate: 1964–1971

16 Steeled and Hardened: 1971–1976

17 Lady into Amazon: 1962–1976

18 The Shadowy Presence: 1964–1976

19 Black Consciousness: 1976–1978

20 Prison Charisma: 1976–1982

21 A Family Apart: 1977–1980

22 Prison Within a Prison: 1978–1982

23 Insurrection: 1982–1985

24 Ungovernability: 1986–1988

25 The Lost Leader: 1983–1988

26 ‘Something Horribly Wrong’: 1987–1989

27 Prisoner v. President: 1989–1990

Part III: 1990–1999

28 Myth and Man

29 Revolution to Cooperation

30 Third Force

31 Exit Winnie

32 Negotiating

33 Election

34 Governing

35 The Glorified Perch

36 Forgiving

37 Withdrawing

38 Graca

39 Mandela’s World

40 Mandela’s Country

41 Image and Reality

Afterword: Living Legend, Living Statue

Source Notes

Select Bibliography

Searchable Terms

About the Author

Praise

Other Books by Anthony Sampson

Copyright

About the Publisher

Map

INTRODUCTION

I am conscious of both the unusual opportunity and the responsibility in undertaking this book. When I wrote to President Mandela in 1995 suggesting an authorised biography he invited me to breakfast in his house in Johannesburg, and told me he would like me to write it because of our long friendship – ‘Provided,’ he joked, ‘that you don’t mention that we first met in a shebeen.’ He reminded me that he had read my book Anatomy of Britain when he was awaiting trial in 1962. He promised to discuss critical questions with me, to try to ensure that the facts were accurate, and to let me see relevant letters and documents. But he would leave me free to make my own judgements and criticisms: it was important, he said, for the movement to learn from mistakes; and, he insisted, ‘I’m no angel.’

It had been my good luck to have first known Mandela in Johannesburg in 1951, and to have seen him at several decisive moments over the next decade before he went to prison. I first encountered him after I had come out to South Africa to edit the black magazine Drum, which opened all doors into the vibrant and exciting world of black writers, musicians and politicians in the Johannesburg in which Mandela moved, and gave me a front seat from which to observe the mounting black opposition to the apartheid government which had come to power in 1948. I attended the ANC conference which approved the Defiance Campaign of 1952; I watched Mandela organising the first volunteers, and mobilising resistance in 1954 to the destruction of Sophiatown, the multi-racial slum where I had spent many happy evenings. In 1957 I saw him frequently at the Treason Trial, about which I later wrote a book; and in 1960, as a correspondent of the Observer, I covered the Sharpeville crisis and interviewed Mandela in Soweto just after the massacre. My last, poignant sight of him was in 1964, when I was observing the Rivonia trial in Pretoria, which gave me a chance to see the final speech he was then preparing (see pp. 192–3). As a journalist I could not see Mandela during his twenty-seven years in prison, but I revisited black South Africa and kept in touch with exiles in London and elsewhere. In the mid-1980s, when the conflict was escalating, I saw much of Oliver Tambo, the ANC President, in London, and arranged meetings for him with British businessmen. I also talked often to Winnie Mandela by telephone. I returned to Johannesburg for the crises of 1985 and 1986, preparing a book about black politics and business, Black and Gold, before the South African government in 1986 banned me from returning. My ban was temporarily lifted just in time for me to return before Mandela’s release from jail in February 1990; later, I visited him twice a week in his Soweto house. Over the next four years I saw him many times, both in London – where he asked me to introduce him at fund-raising receptions – and in Johannesburg, to which I often returned, and where I watched the elections of April 1994.

Since beginning this book I have made several journeys through South Africa with my wife Sally, trying to piece together the jigsaw of Mandela’s varied life, while immersing myself in the fast-changing contemporary scene. I have seen President Mandela in contrasted settings: in his offices and mansions in Pretoria and Cape Town, in his own house in Houghton, on Robben Island, at banquets and conferences, in Parliament in Cape Town, at the UN in New York or at state occasions in London. I have travelled to the Great Place where he was brought up in the Transkei, and to his new house in Qunu. I have talked to scores of his old friends and colleagues, but also to his former opponents, whether warders, officials or political leaders – including ex-President P.W. Botha in Wilderness, ex-President F.W. de Klerk in Cape Town, and the former Foreign Minister Pik Botha in the Transvaal.

Mandela’s moving autobiography Long Walk to Freedom, published in 1994, has provided his own invaluable record of his political development; I have had generous advice from his collaborator Richard Stengel, whose recorded interviews with Mandela have also been useful. I have also been given access to the unpublished memoir which Mandela wrote in jail, and have seen the original manuscript in his own hand. But Mandela’s own autobiography, published when he had first become President, with political discretion and modesty, leaves all the more scope for a many-sided picture which can describe him as others saw him, show how he interacted with friends and enemies, and put his life into a global context.

In writing this book I have tried to show the harsh realities of Mandela’s long and adventurous life as they appeared to him and to his friends at the time, stripped of the gloss of mythology and romance; but also to trace how the glittering image of Mandela was magnified while he was in jail, acquiring its own power and influence across the world; and to show how the prisoner was able to relate the image to reality.

I have given special emphasis to the long years in prison, with the help of extensive interviews, unpublished letters and documents; for Mandela’s prison story has unique value to a biographer, with its human intensity and tests of character, providing an intimate play rather than a wide-ranging pageant; and Mandela’s relationships with his friends and warders became a universal drama, with a significance that transcended African politics. The prison years are often portrayed as a long hiatus in the midst of Mandela’s political career; but I see them as the key to his development, transforming the headstrong activist into the reflective and self-disciplined world statesman.

I also try to put Mandela’s life into a wider global context, with the help of his letters and hitherto unpublished diplomatic and intelligence sources. I trace how the Western world misunderstood and mishandled the gathering South African crisis in the 1960s and seventies, and was misled about Mandela and his friends through the obsessions and crusades of the Cold War; how he so nearly disappeared from the world’s radar screens, and how governments and individuals contributed to his triumphant return. I have tried to trace the changing and contradictory perceptions of South Africa in the outside world, providing first dire predictions of an imminent bloodbath, then a model of negotiation and reconciliation, with Mandela at the centre.

In this ambitious task I owe an obvious huge debt to President Mandela himself, who has been generous with his precious time, not only by giving personal interviews, but by reading the draft typescripts. He has corrected points of fact and detail, while honouring the agreement not to interfere with my own judgements; and his lively comments have added rather than subtracted from the original draft. It has been a rare experience to have such exchanges with a major historical figure in his own lifetime, which I hope compensates for any of the limitations of a contemporary biographer.

I also owe debts to Mandela’s close friends, some of whom have been friends of mine since the early fifties. Ahmed Kathrada, Mandela’s colleague in jail for twenty-five years, has been my chief adviser and a major source throughout the enterprise, and has unlocked doors which would otherwise have remained closed; he has selflessly given long interviews and allowed me to see his valuable letters – which will soon be published. Walter Sisulu, whom I often interviewed in the fifties and sixties, has patiently given his time for long, reflective talks, adding his special insights into the political background and thinking over fifty years. Mac Maharaj has been through the drafts and has added his unique knowledge of events in and out of jail. Professor Jakes Gerwel, the Secretary of the Cabinet, has given me many ideas and perceptions about Mandela and his government. Nadine Gordimer, my oldest and most valued white South African friend, with whom I usually stayed in Johannesburg, has contributed her unique observations as a close friend of the President and as witness to many historical events. Frank Ferrari, the most distinguished American authority on South Africa, has shared many experiences with me and has added his own judgements. Dr Nthato Motlana, another veteran of the fifties, has been forthcoming with his own witty recollections and insights. Adelaide Tambo, the widow of Oliver Tambo, who has been a friend in both London and Johannesburg, has provided reminiscences and letters which throw new light on the friendship between the Mandelas and the Tambos. George Bizos, Mandela’s chief lawyer whom I first met at the Rivonia trial and whom I have seen on every successive visit to South Africa, has been generous with his wisdom and vivid memories from the front line.

Old Drum colleagues, who have witnessed the extraordinary changes in South Africa over five decades, have provided their varied recollections and views. They include Jim Bailey, the former owner of Drum; Es’kia Mphahlele, the former literary editor; Jürgen Schadeberg, the pioneering photographer and picture editor, and Peter Magubane, his distinguished successor; Arthur Maimane, the versatile writer whom I first lured into journalism in 1951; Esme Matshikiza, widow of the brilliant composer and journalist Todd Matshikiza, together with their son John Matshikiza; and Sylvester Stein, my immediate successor as editor in 1955.

Two former biographers of Mandela, both lifelong friends of the President, have been wonderfully unselfish and forthcoming with advice and documents: Mary Benson, the veteran campaigner against apartheid in London, has had unique insights into the ANC and the Mandela family over forty years; while Fatima Meer, who has seen Mandela through many critical experiences since the fifties, has given me invaluable advice and precious documentation. My old friend Joe Menell generously allowed me to see transcripts of the extensive original interviews for his documentary film about Mandela. For more general advice on difficult problems of biography I am grateful to Michael Holroyd and Arthur Schlesinger.

Among the many new friends who have helped me I am especially grateful to Gail Gerhart, the uniquely well-informed editor of the five-volume history of black politics in South Africa, From Protest to Challenge, which is indispensable to any student of the subject. She has been unstinting in her advice and in sharing her sources, including unpublished documents and interviews. I am grateful to Iqbal Meer, President Mandela’s London lawyer, both for making the arrangements for the book, and for very constructive suggestions. I have appreciated the help of Ismail Ayob, the President’s long-standing attorney in Johannesburg. And I have learnt much from Guy Berger and his colleagues at Rhodes University, where I enjoyed a very productive stay.

I have had wonderful assistance from librarians and archivists in South Africa who have put previously unseen documents at my disposal. They include the Brenthurst Library, with its unique collection in Johannesburg; the Cullen Library at Witwatersrand University; the ANC archives in Shell House, Johannesburg and also at Fort Hare University; the valuable Cory Library at Rhodes University, Grahamstown; the Harry Oppenheimer Library at the University of Cape Town; the Mayibuye archive at the University of the Western Cape; and the admirable press cuttings of the Johannesburg Star and the Cape Times. I have also been given access to government archives which must remain more discreet. In London my researcher has used the libraries of the School of Oriental and African Studies and the Institute of Commonwealth Studies; while in Washington the National Security Archive has been wonderfully helpful.

My whole task has been made much easier by the energy and resourcefulness of my research assistant Dr James Sanders, who has been persistent in tracking down documents, checking sources, and finding new avenues of investigation which have unearthed remarkable new information from archives in London, Washington and Pretoria. His contribution has gone far beyond research, and I owe much to his creative and scholarly mind, which provided ideas, questions and solutions to difficult problems, and made the whole enterprise less lonely and more enjoyable.

Through the stressful process of editing and preparing the book for publication I have enjoyed marvellous support and cooperation from the team at HarperCollins. The first idea of the book came from Stuart Profitt, without whom it would not have happened; but after he left HarperCollins in 1998 it was strongly backed by the chairman Eddie Bell, by my long-suffering editors Richard Johnson and Robert Lacey, and by Helen Ellis the publicity director, all wonderfully committed to the project. I have also benefited from the encouragement and long experience of my American editor, Charles Elliott of Alfred A. Knopf. I am grateful to Jonathan Ball, my publisher in South Africa, for his help and enthusiasm. My indexer Douglas Matthews has, as with previous books, added his scholarship. As always I have been loyally supported by my agent Michael Sissons, who has now seen me through over twenty books. And I could not have got through the task without my assistant Carla Shimeld, who has once again remained efficient and unflappable in producing order out of chaos. Above all, my enjoyment and human understanding of the subject has been magnified by having my wife Sally with me through many of my travels and interviews.

I have been indebted to many people for corrections and clarifications, but I must take full responsibility for any surviving errors; and I will be grateful for any rectifications and suggestions from readers which I can incorporate in subsequent editions.

I would like to thank all the following people in South Africa who have generously contributed interviews and conversations with myself or my assistant James Sanders (marked with an asterisk):

Rok Ajulu, Neville Alexander, Charles Anson, Kader Asmal, Ismail Ayob, Beryl Baker, Fikile Bam, Niël Barnard, John Battersby, David Beresford, Guy Berger, Hyman Bernadt, George Bizos, Tony Bloom, Alex Boraine, Pieter Botha, Pik Botha, P.W. Botha, Lakhtar Brahimi, Christo Brand, Jules Browde, Gordon Bruce

, Brian Bunting, Mangosuthu Buthelezi, Amina Cachalia, Andrew Cahn, Luli Callinicos, Arthur Chaskalson, Frank Chikane, Colin Coleman, Keith Coleman, Jeremy Cronin, Eddie Daniels, Apollon Davidson, F.W. de Klerk, Ebbe Demmisse, Robin Denniston, Helena Dolny, John Dugard, Barend du Plessis, Tim du Plessis, Dick Endhoven, Ivan Fallon, Barry Feinberg, Ilse Fischer, Maeve Fort, Amina Frense, Phillippa Garson, Mark Gevisser, Angus Gibson, Frene Ginwala, Pippa Green, James Gregory, Louisa Gubb, Adrian Hadland, Anton Harber, Tony Heard, Rica Hodgson, Bantu Holomisa, Evelyn Holtzhausen, John Horak, Verna Hunt, Charlayne Hunter-Gault, Zubeida Jaffer, Joel Joffe, R.W. Johnson, Shaun Johnson, Pallo Jordan, Ronnie and Eleanor Kasrils, Mark Katzenellenbogen, Liza Key, Martin Kingston, Horst Kleinschmidt, Mavis Knipe, Wolfie Kodesh, Alf Kumalo, Terror Lekota, Hugh Lewin, Tom Lodge, Raymond Louw, Enos Mabuza, Graca Machel, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, Peter Magubane, Stryker Maguire, Arthur Maimane, Evelyn Mandela, Maki Mandela, Parks Mankahlana, Barbara Masekela, Nathaniel Masemola, Kaiser Matanzima, Don Mattera, Joe Matthews, Govan Mbeki, Thabo Mbeki, Iqbal Meer, Irene Menell, Roelf Meyer, Raymond Mhlaba, Abdul Minty, Joe Mogotsi, Ismail Mohammed, Popo Molefe, Eric Molobi, Ronnie Momoepa, Ruth Mompati, Murphy and Martha Morobe, Shaun Morrow, Mendi Msimang, Mary Mxadana, Beyers Naude, Joel Netshitenzhe, Lionel Ngakane, Carl Niehaus, Wiseman Nkhuhlu, Kaizer Nyatsumba, Andre Odendaal, Chloe O’Keefe, Marie Olivier, Dullah Omar, Harry Oppenheimer, Tony O’Reilly, Aziz Pahad, Essop Pahad, Sophie Pedder, Benjamin Pogrund, Cyril Ramaphosa, Narissa Ramdani, Mamphela Ramphele, Dolly Rathebe, Bryan Rostron, Anthony Rowell, John Rudd, Albie Sachs, Peter Saraf, Raks Seakhoa, Jeremy Seekings, Ronald Segal, Michael Seifert, Wally Serote, Tokyo Sexwale, Lazar Sidelsky, Mike Siluma, Albertina Sisulu, Elinor Sisulu, Zwelakhe Sisulu, Gillian Slovo, Mungo Soggott, Roger Southall, Allister Sparks, Tim Stapleton, Hendrik Steyn, John Sutherland, Helen Suzman, Tony Trew, Ben Turok, Desmond Tutu, Philip van Niekerk, Xolisa Vapi, Ben Verster, Esther Waugh, Enid Webster, Leon Wessels, General Johan Willemse, Moegsien Williams, Jacob Zuma.

And to the following in London and elsewhere abroad:

Heribert Adam, David Astor, Mary Benson, Rusty and Hilda Bernstein, Betty Boothroyd, Lord Camoys, Cheryl Carolus, Lady (Lynda) Chalker, John Colvin, Ethel de Keyser, David Dinkins, John Doubleday, Richard Dowden, Marcus Edwards, Eleanor Emery

, Sir Patrick Fair-weather, Michael Gavshon, Dennis Goldberg, Denis Healey, Sir Edward Heath, Denis Herbstein, Eric Hobsbawm, George Houser

, Trevor Huddleston, Lord (Bob) Hughes, Paul and Adelaide Joseph, Glenys Kinnock, Brian Lapping, Colin Legum, Martin Leighton

, Freda Levson, Anthony Lewis, John Longrigg

, Trevor Macdonald, Sir Kit McMahon, Shula Marks, Jacques Moreillon, Lionel Morrison, Lady (Emma) Nicholson, Robert Oakeshott, Thomas Pakenham, Nad Pillay, Vella Pillay, Elaine Potter, Sir Charles Powell, Lord Renwick, Jon Snow, Lady (Mary) Soames, George Soros, Richard Stengel, John Taylor, Noreen Taylor, Michael Terry, Stanley Uys, Randolph Vigne, Per Wastberg, Brian Widlake

, Donald Woods, Ann Yates, Andrew Young, Michael Young.

In this revised paperback edition I have made some corrections and additions to the original text. I am grateful to all those correspondents who have taken the trouble to suggest changes.

ANTHONY SAMPSON

London, December 1999

PROLOGUE

The Last Hero

WESTMINSTER HALL in London, the ancient heart of the Houses of Parliament, is preparing to honour a visiting head of state, in a ceremony which happens only once or twice in a lifetime. The last such guest of honour was General de Gaulle in 1960; this time, in July 1996, it is President Nelson Mandela. The comparison is apt, for both were solitary, lost leaders who came to be seen as saviours of their country. But Mandela’s transformation is much more surprising than de Gaulle’s. In the past, many of the politicians in the audience had regarded him as their enemy, who should never be permitted to lead his country. Many Conservative Members of Parliament had condemned him as a terrorist; the former Prime Minister Lady Thatcher, who is sitting near the front, had said nine years before that anyone who thought the African National Congress was ever going to form the government of South Africa was ‘living in cloud-cuckoo land’. Now cloud-cuckoo land has arrived in Westminster Hall. But the ceremonials in this medieval hall have legitimised many awkward shifts of loyalty over the centuries, whether from Richard II to Henry IV in 1400 or from Charles I to Oliver Cromwell in 1649. And now all recriminations are drowned in a fanfare of trumpets.

It is like a scene from grand opera, with Beefeaters lining the steps and helmeted guardsmen at the back of the hall. The Lord Chancellor, Lord Mackay of Clashfern, arrives in his robes of state. Then, at last, the tall, lean figure of Nelson Mandela appears and walks shakily down the grand staircase, holding the hand of the Speaker of the House, Betty Boothroyd: she says afterwards it was the most memorable five minutes of her life. The Labour peer sitting in front of me allows tears to flow down his cheek. The band of the Grenadier Guards plays ‘Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika’, for decades the hymn of South Africa’s black revolutionaries. The Lord Chancellor makes a modest speech, recalling how this hall has witnessed the slow evolution of democracy, ever since the Magna Carta in 1215, and how Britons and South Africans share the democratic right to one person, one vote. Then he warmly introduces the former revolutionary, who now looks as benign as an old-fashioned English gentleman.

Mandela speaks slowly, with his usual formal emphasis. Although most guests cannot hear him through the echoing acoustics, it is a tough speech which does not please Lady Thatcher, as she says afterwards. He looks back two hundred years, to when Britain first colonised South Africa and seized the land of his forebears. He reminds his audience how the ANC first petitioned the British parliament eight decades ago, in protest against being left to the mercy of the white rulers of the new Union of South Africa. But now, he says, he comes as a friend of Britain, to the country of allies like William Wilberforce, Fenner Brockway, Archbishop Trevor Huddleston. He goes on to refer to the horrors of racism, whether in South Africa or in Nazi Germany – ‘How did we allow these to happen?’ – and the appalling massacres and miseries in other parts of Africa; but he ends by looking ahead to the closing of the circle, to Britain and South Africa joining hands to construct a humane Africa.

This is the historic Mandela: the last of the succession of revolutionary leaders in Asia and Africa who fought for their freedom, were imprisoned and reviled, and were eventually recognised as heads of state. But the Afrikaner nationalists were much more ruthless enemies, and he now shows more magnanimity than his predecessors, giving hope both to his own people and to others that they can bridge their own racial chasms. He has become a universal hero at the end of the twentieth century. In a time of vote-counters, spin-doctors and focus groups, he conjures up an earlier age of liberators, war leaders and revolutionaries. To conservative traditionalists he evokes memories of great men who personified their own country; to the liberal left, battered by lost causes, he brings new hope that righteous crusades can still prevail; his three decades in jail cut him off from the surge of materialism and consumerism that swept through the Western world.

As Mandela goes through the pompous routines of a state visit, he even brings new life to the British monarchy itself, under siege with its own troubles. Some of the audience go straight from Westminster Hall to the Dorchester Hotel, where he is giving a banquet for the Queen. He arrives with her, looking both more regal and more at ease than the monarch as he lopes between the guests. At the end of the lunch he gives another brief speech, reminding the Queen that he’s just a country boy, thanking her for opening all doors to British society and for letting him walk in her garden early in the morning. The Queen’s relaxation in his company is obvious as they talk. ‘She’s got a lot in common with him,’ one courtier explains. ‘You see, they’ve both spent a lot of time in prison.’

In the evening another Mandela is presented to the young generation: the showbiz idol and friend of pop stars. He is the guest of Prince Charles, together with most of the royal family, for a concert attended by five thousand people at the Albert Hall. Mandela has always praised musicians for their role in confronting racism, and for agitating for his release from jail; now they have gathered to pay him tribute, beginning with Phil Collins’ Big Band and ending with a triumphant finale led by the South African trumpeter Hugh Masekela. The whole audience clap and sway. In the royal box Mandela jumps to his feet and begins jiving, jauntily swinging his arms. Prince Charles awkwardly begins to shuffle, the Queen makes some cautious claps, and even Prince Philip is seen to tilt. Beside them Mandela seems like a fantasy monarch: the man with rhythm who can swing and dance with his subjects.

The next morning there is another Mandela: the champion of the underdog, the people’s president who can bring all the races together. With Prince Charles he makes a tour of the multi-racial south London suburb of Brixton, where he is greeted by a huge crowd of black and white Londoners. From there he goes on to Trafalgar Square, dominated on one side by South Africa House, the old fortress of apartheid which is now the symbol of liberation. The square is closed to traffic, and is packed solid with people wearing Mandela T-shirts and waving flags. As he walks slowly through the crowd children gaze in wonder, and reach out to touch him. When he appears on the balcony of South Africa House he seems more like a pope blessing the crowd than a politician: ‘I would like to put each and every one of you in my pocket.’ He talks about love, without embarrassment: ‘I am not very nervous of love, for love is very inspiring.’

Why should an elderly African politician attract such unique affection – not just in Britain, but throughout Europe, America and Asia – at a time when politicians everywhere are more distrusted than ever before? What has happened, I cannot help wondering, to the stiff, proud young lawyer and revolutionary whom I first knew in Johannesburg in the fifties, who looked so suspiciously at the hostile white world and made fierce speeches denouncing the British imperialists? What has changed that young man’s flashing smile into the welcoming grin which seems so genuinely warm?

From Trafalgar Square he goes on to the Dorchester, where I have the chance to talk to him briefly in private. He is in a euphoric mood, delighted by his welcome from the Queen and from the crowd in Brixton. He recalls how he first visited London in 1962 when he was on the run as a ‘raw revolutionary’, two months before he went to jail for twenty-seven years. I ask him why he seems so transformed. He laughs: ‘Perhaps I was defensive then.’ Now he seems totally at ease with everyone, including himself; but he makes it clear, as always, that he does not wish to talk about his own feelings.

It is not easy for a biographer to portray the Nelson Mandela behind the icon: it is rather like trying to make out someone’s shape from the wrong side of the arc-lights. The myth is so powerful that it blurs the realities, turning everything into show business and attracting Hello! magazine as much as the New York Times. It is a myth which fascinates children as much as adults, the world’s favourite fairy-tale: the prisoner released from the dark dungeon, the pauper who turns out to be a prince, the bogeyman who proves to be the wizard. Cynical politicians also wipe away tears in Mandela’s presence, perhaps seeing him as a secular saint who makes their own profession seem noble, who rises above their failings. Some have warned me: ‘I don’t want to hear anything bad about him.’

But it is not realistic to portray Mandela as a saint, and he himself has never pretended to be one: ‘I’m no angel.’ No saint could have survived in the political jungle for fifty years, and achieved such a worldly transformation. Mandela has his share of human weaknesses, of stubbornness, pride, naïveté, impetuousness. And behind his moral authority and leadership, he has always been a consummate politician. ‘I never know whether I’m dealing with a saint or with Machiavelli,’ one of his closest colleagues has said. His achievement has been dependent on mastering politics in its broadest and longest sense, on understanding how to move and persuade people, to change their attitudes. He has always been determined, like Gandhi or Churchill, to lead from the front, through his example and presence; and he learnt early how to build up and understand his own image.

For all his international acclaim, Mandela remains very African: and in Africa he emerges even more clearly than elsewhere as the master of politics. A week after his visit to Britain he is giving a birthday party in the grounds of his official mansion in Pretoria for ‘veterans of the struggle’. Coachloads of guests, including ancient grandmothers and grandfathers, converge on the huge marquee. Mandela appears at one end, towering above them, luminous in a brightly coloured loose shirt, while his bodyguards dart to and fro to cover his highly visible back. He works the room like any presidential candidate, revelling in the love from the crowd, spotting distant faces, remembering names, radiating goodwill and reaching out with his big boxer’s hands. He fixes each guest with an intimate look, a personal smile, listening apparently intently – ‘I see, I see’ – leaving them glowing with pride and pleasure. He moves to the middle of the marquee to welcome his special guests, enfolding them in his bony embrace, including his cabinet and a few white friends like Helen Suzman and Nadine Gordimer. He sits between two friends of fifty years’ standing, Walter Sisulu and Ahmed Kathrada. But he remains the arch-politician, showing little difference between his political and private self, relating to everyone in the same hearty style.

And he has his own agenda of nation-building, which he explains in an impromptu speech, without spectacles, with no journalists to report it. He has invited his guests, he says, because each of them has made some contribution to South Africa’s peaceful transformation; but also to remind them where they came from: ‘The history of liberation heroes shows that when they come into office they interact with powerful groups: they can easily forget that they’ve been put in power by the poorest of the poor. They often lose their common touch, and turn against their own people.’ Here Mandela is playing his last political game, for the highest stakes: to hold together the disparate South African nation. ‘I’m prepared to do anything,’ he says later ‘to bring the people of this country closer together.’

As the band strikes up and the real party begins, the old man at the top table surveys the scene. The musicians and singers include stars of the fifties like Dolly Rathebe and Thandi Klaasens, who conjure up memories of Mandela’s youth in Johannesburg. The guests come from every stage of his long political career: country tribespeople who still see him as a traditional ruler; white and Indian communists who shared his struggle in the fifties and sixties; ex-prisoners from Robben Island who hacked limestone with him in the quarry; white businessmen who condemned him as a terrorist until the nineties, then welcomed him to their dinner parties. With each group he extended his political horizons, and he moves casually between them all, slipping easily from township slang to financial jargon. But in repose, he suddenly gives a glimpse of another Mandela, with a turned-down mouth and a weary gaze of infinite loneliness, as if the scene around him is only a show. And behind all his gregariousness he still maintains an impenetrable reserve, defending his private hinterland, which seems much deeper than that of other politicians.

A few days after the party, in his sombre presidential office in the Union Buildings in Pretoria, he reflects quietly about the hectic past two weeks. He happily remembers the warmth and enthusiasm of his welcome in Britain, but he becomes much more intimate when he goes on to talk about his twenty-seven years in jail. He recalls again how he came to realise in prison that the warders could be good or bad, like any other people. ‘It was a tragedy to lose the best days of your life, but you learnt a lot. You had time to think – to stand away from yourself, to look at yourself from a distance, to see the contradictions in yourself.’

He still seems to keep his prison cell inside him, protecting him from the outside world, controlling his emotions, providing a philosopher’s detachment. It was in jail that he developed the subtler art of politics: how to relate to all kinds of people, how to persuade and cajole, how to turn his warders into his dependants, and how eventually to become master in his own prison. He still likes to quote from W.E. Henley’s Victorian poem ‘Invictus’: ‘I am the master of my fate, I am the captain of my soul.’

In this book I try to penetrate the Mandela icon, to show the sometimes harsh realities of his long and adventurous journey, stripped of the gloss of mythology; and to discover how this most private man relates to this most public myth. I try to penetrate into the prison years, when for almost three decades he was hidden from the glare of public politics, and gained the detachment which steeled him for the ordeals ahead. And I try to trace the unchanging man behind all the Mandelas in his bewildering and wide-ranging career: the son of an African chief who retained many of his rural values while bestriding the global stage.

PART I

1918–1964

1

Country Boy

1918–1934

FEW PARTS of South Africa are more remote from city life than the Transkei, six hundred miles south of Johannesburg. It is one of the most beautiful but also one of the poorest regions of the country. The limitless vistas of rolling hills, pale green grass and round thatched huts, with herdboys and shepherds driving their flocks between them, present an almost Biblical vision of a timeless, idyllic, pastoral life. But the beauty is skin-deep: the land is desperately overpopulated, and the thin soil is so eroded that it can only sustain scattered groups of scrawny cattle or sheep and sporadic crops of maize.

It is here that Nelson Mandela was born and brought up, and here that he has built the house to which he retreats for Christmases and holidays, and where he intends to retire. It is a large red-brick bungalow with Spanish-style arches alongside the main road, the N2 from Durban to Cape Town, a few miles south of Umtata, Transkei’s biggest town. It stands at the end of an avenue of cypresses, surrounded by a wall and a bushy garden which cuts it off from the open countryside. Mandela conceived the house during his last year in jail, and based its floor-plan on the warder’s house in the prison compound where he was living. He chose the site, which looks over his home district of Qunu, in the belief that ‘a man should die near where he was born’.

Mandela’s actual birthplace is several miles south, in the small village of Mvezo on the banks of the winding Mbashe (Bashee) river, where his father was hereditary chief. (The family’s group of huts, or kraal, is no longer there: in 1988 Mandela, then in jail, would ask a local lawyer to locate it, but he could find no trace.

) Rolihlahla Mandela was born in Mvezo on 18 July 1918 – at a time, he would later reflect, when the First World War was coming to an end, the Bolshevik revolution in Russia was being consolidated, and the newly-formed African National Congress sent a deputation to London to plead for the rights of black South Africans. The British Cape Colony, which included the ‘native reserve’ of the Transkei, had been absorbed into the Union of South Africa in 1910, and three years later the Native Land Act dispossessed hundreds of thousands of black farmers, many of whom trekked to the Transkei, the only large area where Africans could own land. The Transkei has produced more black leaders than any other region of South Africa, and it was with this history that they were brought up.

Rolihlahla’s father, Hendry Mandela, suffered his own dispossession. The year after his son was born the local white magistrate summoned Hendry to answer a tribesman’s complaint about an ox. Hendry refused to come, and was promptly charged with insubordination and deposed from the chieftainship, losing most of his cattle, land and income. The family moved from their ancestral kraal in Mvezo to the nearby village of Qunu, where the boy Mandela would spend his next few years. Although their fortunes had suddenly declined, they kept together without too much hardship. They shared food and simple pleasures with cousins and friends, and Mandela never felt alone: in later life he would look back warmly on that collective spirit and sense of shared responsibility, before Western influences began to introduce competition and individualism.

Hendry Mandela was a strict father, with a stubbornness which his son suspects he inherited. He was illiterate, pagan and polygamous; but he was tall and dignified, darker than his son, and with no sense of inferiority towards whites. He inhabited a self-contained rural world with its own established customs and rituals. He had four wives, of whom Mandela’s mother, Nosekeni Fanny, was the third. Each had her own kraal, which was more or less self-sufficient, with its own fields, livestock and vegetables.

Hendry would move between the different kraals visiting his wives, who appear to have been on good terms with each other. He kept some home-brewed liquor in his hut, with a bottle of brandy in the cupboard which would last three or four months. He respected tribal customs: when a baby was born he slaughtered a goat and erected its horns in the house.

Hendry never became a Christian, but he had some Christian friends, including the Reverend Tennyson Makiwane, a scholarly community leader who was part of the elite of the Transkei (his offspring were later to be controversial members of the ANC).

He was also close to the Mbekela brothers, George and Ben, who belonged to the separate tribal group called Amamfengu, or ‘Fingoes’; this group remained apart from the Xhosa people, and were more influenced by missionaries and Western customs, many of them becoming teachers, clergymen or policemen. The Mbekela brothers converted Mandela’s mother to Methodism, after which she began wearing Western dresses instead of Xhosa garb. She had her son baptised as a Methodist, and later the brothers persuaded both parents that Mandela should go to the local mission school – the first member of the family to do so.

Mandela’s sisters Mabel and Leabie would recall with pleasure the simple country life of their childhood in Qunu, revolving around the three round huts or rondavels in their mother’s kraal – one for sleeping, one for cooking, one for storing food – fenced off with poles. The rondavels were made by their mother from soil moulded into bricks; the simple chairs and cupboards were also made of soil, and the stove was a hole in the ground. There were no beds or tables, only mats. The roofs were made of grass held together with ropes.

They lived largely on maize, which was stored in holes (izisele) in the kraals. The boys spent the day herding the cattle, and the girls and women of the family prepared the food together in one of the houses, grinding the maize between stones, cooking it in black three-legged metal pots and mixing it with sour milk. The family would all take the main meal together in the evening, sitting on the ground eating from a single dish.

Mandela’s father already had three sons by other wives, but they had already left home. As a boy, he had much more freedom than his sisters. He was very close to his mother, but would often stay with another of his father’s wives, with whom he felt the same security and love as with Nosekeni Fanny. Throughout his life he would always feel most at ease with women – particularly with strong women who could provide rewarding friendships, which may be linked to his childhood experience. He thrived within his extended family of cousins, stepmothers and half-brothers and-sisters (Bantu languages have no words for stepsisters or stepmothers, so he called all his father’s wives his ‘mothers’). ‘I had mothers who were very supportive and regarded me as their son,’ he recalled. ‘Not as their stepson or half-son, as you would say in the culture amongst whites. They were mothers in the proper sense of the word.’ His happy experience as a son loved by four mothers made his childhood very secure, and he sometimes talks nostalgically about polygamy at that time, although he firmly rejects it in today’s conditions: ‘Quite inexcusable. It shows contempt for women, and it’s something I discourage totally.’

In his letters and memoirs Mandela often harks back to his life as a country boy. From his prison cell he wrote vividly about the splendour of the hills and streams, the pleasures of swimming in the pools, drinking milk straight from the cows’ udders or eating maize roasted on the cob. Many world leaders, caught up in power-politics in the capitals, have played up their romantic rural roots, like Lloyd George revisiting his Welsh village or Lyndon Johnson longing for his Texas ranch. But President Mandela would be more insistent in calling himself a country boy; and with more reason, for the security and simplicity of his rural upbringing played a crucial part in forming his political confidence.

He was also fortified by his knowledge of his ancestors. His father was the grandson of Ngubengcuka, the great king of the Tembu people who died in 1832, before the British finally imposed their power on Tembuland, the southern part of the Transkei. The Tembu royal family, however poor and dependent they might seem to whites, retained a special grandeur in the Transkei, commanding the loyalty and respect of their people. Mandela was a minor royal, and he always stressed that he was never in the line of succession to the throne.

He was only one of scores of descendants of King Ngubengcuka, and he came from a junior line. But his father was a trusted friend and confidant of King Dalindyebo, who had succeeded to the Tembu throne, and later of his son King Jongilizwe. Hendry in fact was a kind of prime minister, and the boy Mandela commanded respect in his community.

His was a royal family, as they saw it, but under an occupying force, for since the time of Ngubengcuka their powers had been circumscribed: first by the British government, then after 1910 by the new Union of South Africa, and the Transkei monarchs were torn between their duties to their people and the demands of an alien power. However proud and respected the Tembu royals remained, they were always conscious that the new patricians, the British and the Afrikaners, had deprived them of their authority and wealth. When the young Mandela began to travel beyond his home district, he saw that the towns in the Eastern Cape – Port Shepstone, King William’s Town, Port Elizabeth, Alice – were named after British, not Xhosa, heroes, and that the white men were the real overlords.

Many mission-educated children of Mandela’s generation were named after British imperial heroes and heroines like Wellington, Kitchener, Adelaide or Victoria, and at the age of seven Mandela acquired a new first name, to precede Rolihlahla. ‘From now on you will be Nelson,’ said his teacher. His mother pronounced it ‘Nelisile’, while others would later call him ‘Dalibunga’, his circumcision name. His later city friends called him ‘Nelson’ or ‘Nel’, until he expressed a preference for his clan name, ‘Madiba’, which the whole nation was to adopt.

In 1927 Mandela, then aged nine, came closer to royalty. His father had been suffering from lung disease, and was staying in Mandela’s mother’s house. His friend Jongintaba, the Regent of the Tembu people, was visiting, and Mandela’s sister Mabel overheard Hendry telling him: ‘Sir, I leave my orphan to you to educate. I can see he is progressing and aims high. Teach him and he will respect you.’ The Regent replied: ‘I will take Rolihlahla and educate him.’ Soon afterwards Hendry died. His body was carried on a sledge to his first wife’s house, and a cow was slaughtered; but he was also given a Christian funeral conducted by the Mbekela brothers, and was buried in the local cemetery.

Mandela was taken by his mother on a long journey by foot from Qunu to the ‘Great Place’ of Mqhekezweni. It was from here that the Regent presided over his people as acting king, since the heir apparent, Sabata, was too young to rule. Jongintaba, who was also head of the Madiba clan, was indebted to Mandela’s father for recommending him as Regent, which may explain why he so readily agreed to adopt Mandela as if he were his own son. But the tradition of the extended family was much stronger in rural areas than in the towns, for which Mandela remained grateful. As he wrote from jail: ‘it caters for all those who are descended from one ancestor and holds them together as one family’.

The Great Place at Mqhekezweni hardly conforms to the European image of a royal palace. Even today it remains ruggedly inaccessible, and is difficult to reach by car. From the main road a rough, deeply-rutted dirt track twists across the landscape, down into dried-up riverbeds and up stony banks, passing isolated clusters of rondavels and huts and a deserted railway station. At last a small settlement appears: two plain houses facing a group of rondavels, with an overgrown garden between them, a school building and some huts beyond. From one house a fine-looking, naturally dignified man emerges and reveals himself as the local chief, the grandson of Jongintaba; he still presides over the local community. He points out the plain rondavel where President Mandela lived as a boy. A photograph on the wall of one of the houses shows the fine face of Jongintaba, with a trim moustache. Nearby is a solemn-looking young Mandela, alongside his smiling face on an election poster of 1994.

To the Western visitor today the Great Place may seem small and remote, but to the young Mandela in 1927 it was the centre of the world, and Mqhekezweni was a metropolis compared to the huts of Qunu. It was here that Mandela spent his most formative years and gained the impressions of kingship which were to influence his whole life. He would never forget the moment when he first saw the Regent arriving in a spectacular motor car, welcomed by his people with shouts of ‘Aaah! Jongintaba!’ (The scene would be re-enacted seventy years later when President Mandela was hailed by cries of ‘Aaah! Dalibunga!’) Mqhekezweni was more prosperous then, and almost self-sufficient; its chief was then also regent, attracting tribesmen from all over Tembuland to consult him.

The nine-year-old boy arrived with only a tin trunk, wearing an old shirt and khaki shorts roughly cut from his father’s old riding breeches, with a piece of string as a belt. His cousin Ntombizodwa, four years older, remembered him as shy, lonely and quite silent, but he was immediately welcomed by Jongintaba and his wife No-England.

Mandela shared with their son Justice a small whitewashed rondavel containing two beds, a table and an oil lamp. He was treated as one of the family, together with Jongintaba’s daughter Nomafu, and later with Nxeko, the elder brother of Sabata, the heir to the kingdom. He saw himself as a member of a royal family, with a much grander style of life than that of Qunu; but he did not altogether belong to it – which may have spurred his ambition.

The Regent, Jongintaba, otherwise known as David Dalindyebo, became Mandela’s new father-figure. He was a handsome man, always very well-dressed; Mandela lovingly pressed his trousers, inspiring his lifelong respect for clothes. Jongintaba was a committed Methodist – though he enjoyed his drink – and prayed every day at the nearby church run by his relative the Reverend Matyolo. His son Justice, four years Mandela’s elder, was to be his role model for the next decade, the ideal of worldly prowess and elegance, as sportsman, dandy and ladies’ man. Justice was an all-rounder, excelling in team sports like cricket, soccer and rugby. Mandela, less well co-ordinated, made his mark in more rugged and individual sports like boxing and long-distance running. A photograph shows Justice as bright-eyed, confident and combative, while the young Mandela was less assertive, and strove to acquire Justice’s assurance. Justice was after all the heir to the chieftaincy, while Mandela depended on the Regent’s favours.

Mandela loved the country pleasures at Mqhekezweni, which were more numerous in those days than they are now, and included riding horses and dancing to the tribal songs of Xhosa girls (how different, he reflected in jail, from his later delight in Miriam Makeba, Eartha Kitt or Margot Fonteyn). But Mandela was also more serious and harder-working than the other boys. He thrived at the local mission school, where he began to learn English from Chambers’ English Reader, writing on a slate and speaking the words carefully, with a slow formality and the local accent which never left him.

Whites were hardly visible at Mqhekezweni, except for occasional passers-by. Mandela’s sister Mabel remembers being impressed when he and his schoolfriends met a white man who needed help because his motorbike had broken down, and Mandela was able to speak to him in English.

But Mabel could also be quite frightened of Mandela: ‘He didn’t like to be provoked. If you provoked him he would tell you directly … He had no time to fool around. We could see he had leadership qualities.’

A crucial part of Mandela’s education lay in observing the Regent. He was fascinated by Jongintaba’s exercise of his kingship at the periodic tribal meetings, to which Tembu people would travel scores of miles on foot or on horseback. Mandela loved to watch the tribesmen, whether labourers or landowners, as they complained candidly and often fiercely to the Regent, who listened for hours impassively and silently, until finally at sunset he tried to produce a consensus from the contrasting views. Later, in jail, Mandela would reflect:

One of the marks of a great chief is the ability to keep together all sections of his people, the traditionalists and reformers, conservatives and liberals, and on major questions there are sometimes sharp differences of opinion. The Mqhekezweni court was particularly strong, and the Regent was able to carry the whole community because the court was representative of all shades of opinion.

As President, Mandela would seek to reach the same kind of consensus in cabinet; and he would always remember Jongintaba’s advice that a leader should be like a shepherd, directing his flock from behind by skilful persuasion: ‘If one or two animals stray, you go out and draw them back to the flock,’ he would say. ‘That’s an important lesson in politics.’

Mandela was brought up with the African notion of human brotherhood, or ‘ubuntu’, which described a quality of mutual responsibility and compassion. He often quoted the proverb ‘Umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu,’ which he would translate as ‘A person is a person because of other people,’ or ‘You can do nothing if you don’t get the support of other people.’ This was a concept common to other rural communities around the world, but Africans would define it more sharply as a contrast to the individualism and restlessness of whites, and over the following decades ubuntu would loom large in black politics. As Archbishop Tutu defined it in 1986: ‘It refers to gentleness, to compassion, to hospitality, to openness to others, to vulnerability, to be available to others and to know that you are bound up with them in the bundle of life.’

Mandela regarded ubuntu as part of the general philosophy of serving one’s fellow men. From his adolescence, he recalled, he was viewed as being unusually ready to see the best in others. To him this was a natural inheritance: ‘People like ourselves brought up in a rural atmosphere get used to interacting with people at an early age.’ But he conceded that, ‘It may be a combination of instinct and deliberate planning.’ In any case, it was to become a prevailing principle throughout his political career: ‘People are human beings, produced by the society in which they live. You encourage people by seeing good in them.’

Mandela’s admiration for tribal traditions and democracy was reinforced by the Xhosa history that he picked up from visiting old chiefs and headmen. Many of them were illiterate, but they were masters of the oral tradition, declaiming the epics of past battles like Homeric bards. The most vivid story-teller, Chief Joyi, like Mandela a descendant of the great King Ngubengcuka, described how the unity and peace of the Xhosa people had been broken by the coming of the white men, who had divided them, dispossessed them and undermined their ubuntu.

Mandela would often look back to this idealised picture of African tribal society. He described it in a long speech in 1962, shortly before he began his prison sentence:

Then our people lived peacefully, under the democratic rule of their kings and their amapakati, and moved freely and confidently up and down the country without let or hindrance. Then the country was ours, in our own name and right. We occupied the land, the forests, the rivers; we extracted the mineral wealth below the soil and all the riches of this beautiful country. We set up and operated our own government, we controlled our own armies and we organised our own trade and commerce.

It was, in his eyes, a golden age without classes, exploitation or inequality, in which the tribal council was a model of democracy:

The council was so completely democratic that all members of the tribe could participate in its deliberations. Chief and subject, warrior and medicine man, all took part and endeavoured to influence its decisions. It was so weighty and influential a body that no step of any importance could ever be taken by the tribe without reference to it.

The history of the Xhosas was very much alive when Mandela was a child, and old men could remember the time when they were still undefeated. The pride and autonomy of the Transkei and its Xhosa-speaking tribes – the Tembus, the Pondos, the Fingoes and the Xhosas themselves – had survived despite the humiliations of conquest and subjection over the previous century. Some Xhosas had intermarried with other peoples, including the Khoikhoi (called ‘Hottentots’ by white settlers), which helped to give a wide variety to their physical features: Mandela’s own distinctive face, with his narrow eyes and strong cheekbones, has sometimes been explained by Khoikhoi blood.

But the Xhosas retained their distinctive culture and language. Many white colonists who first encountered them in the late eighteenth century were impressed by their physique, their light skin and sensitive faces, and their democratic system of debate and government: ‘They are equal to any English lawyers in discussing questions which relate to their own laws and customs,’ wrote the missionary William Holden in 1866. In the 1830s the British Commander Harry Smith called the Xhosa King Hintsa ‘the very image of poor dear George IV’.

But, over the course of a hundred years and nine Xhosa wars, the British forces moving east from the Cape gradually deprived the Xhosas of their independence and their land. By 1835 Harry Smith had crossed the river Kei to begin the subjugation of the Transkei. By 1848 he had imposed his own English system on the Xhosa chiefs, informing them that their land ‘shall be divided into counties, towns and villages, bearing English names. You shall all learn to speak English at the schools which I shall establish for you … You may no longer be naked and wicked barbarians which you will ever be unless you labour and become industrious.’

In the eighth Xhosa war in 1850 the British Army – after setbacks which strained it to its limit and atrocities committed by both sides – drove the Xhosa chiefs out of their mountain fastnesses and firmly occupied ‘British Kaffraria’, later called the Ciskei. The Tembu chiefs who ruled the southern part of the Transkei had been relatively unscathed by the earlier wars, but now they were subjugated and sent to the terrible prison on Robben Island, just off the coast from Cape Town, which became notorious in Xhosa folklore.

After this humiliation and impoverishment, in 1856 the Xhosas accomplished their own self-destruction. A young prophetess, Nongqawuse, told them to kill all their cattle and to prepare for a resurrection. As a result, over half the population of the Ciskei starved to death. By the end of the ninth Xhosa war in 1878 the two chief houses of the Xhosa people, the Ngqika and the Gcaleka, had been subjugated and were forced into a new exodus across the Kei. Successive leaders were sent to Robben Island, in keeping with the order of Sir George Grey, the Governor of the Cape, ‘for the submission of every chief of consequence; or his disgrace if he were obdurate’.

It was not till 1894 that Pondoland, in the northern part of the Transkei, came under the Cape administration. But after the Union of South Africa came into being in 1910, the Xhosas faced growing controls by white magistrates. The whites, as Mandela came to see it, captured the institution of the chieftaincy, and ‘used it to suppress the aspirations of their own tribesmen. So they almost destroyed the chieftaincy.’

In the later nineteenth century the Zulus, the other major tribal power to the north, became more famous among whites and foreigners as ruthless fighters than the Xhosas, particularly the Zulu warrior-king Shaka, who had set out to conquer and unify all the southern tribes in the 1820s. The Zulus attracted the admiration of many British churchmen, including the dissident Bishop John William Colenso of Natal; but they acquired unique military fame in January 1879 when the British provoked a war with Shaka’s successor Cetewayo, whose army completely destroyed a British force of 1,200 at the battle of Isandhlwana. When the British sent out reinforcements they included the Prince Imperial, son of Louis Napoleon, who was ambushed and speared to death by Zulu assegais. (‘A very remarkable people the Zulus,’ said Disraeli. ‘They defeat our generals, they convert our bishops, they have settled the fate of a great European dynasty.’

) The humiliation of Isandhlwana was finally avenged in July when the British crushed Cetewayo at the battle of Ulundi and subjugated the Zulus; but their reputation for fighting spirit remained.

The Xhosa chiefs appeared less martial and intransigent than the Zulus, and after the Xhosa wars they seemed defeated and demoralised – sometimes with the help of alcohol. But out of the desolation of the Xhosa wars another tradition was growing up, that of mission schools and Christian culture, which gradually produced a new Xhosa elite of disciplined, well-educated young men and women. While embracing Western ideas, they still aspired to restore the rights and dignity of their own people. The British liberal tradition was reasserting itself in the Cape, with the expansion of the mission stations and the introduction of a qualified vote for blacks. Educated young Xhosas were exploiting the aptitude for legal argument, analysis and debate which early white visitors had observed. It was a route that would in time lead some of them into the political campaigns of the black opposition in the 1960s – sometimes called the tenth Xhosa war – and, like their predecessors, to Robben Island; but they would win their battle, and not through military might, but through their skills in argument and reasoning.

Like other conquered peoples such as the Scots or the American Indians, the Xhosas retained their own version of history which, being largely oral, was easily ignored by the outside world. ‘The European insisted that we accept his version of the past,’ said Z.K. Matthews, the African professor who would teach Mandela. But ‘it was utterly impossible to accept his judgements on the actions and behaviour of Africans, of our own grandfathers in our own lands’.

Mandela, despite all his Western education, would always champion oral historians, and would continue to be inspired by the spoken stories of the Xhosas which he had heard from his elders: ‘I knew that our society had produced black heroes and this filled me with pride: I did not know how to channel it, but I carried this raw material with me when I went to college.’

While most white historians regarded the Xhosa rebellions as firmly placed in the past, overlaid by the relentless logic of Western conquest and technology, Mandela, like other educated Xhosas, saw the white occupation as a recent interlude, and would never forget that his great-grandfather ruled a whole region a century before he was born.

2

Mission Boy

1934–1940

IN 1934, when he was sixteen, Mandela went with twenty-five other Tembu boys, led by the Regent’s son Justice, to an isolated valley on the banks of the Bashee river, the traditional setting for the circumcision of future Tembu kings. No rural Xhosa could take office without this ritual. Mandela would vividly remember the ceremony which marked the coming of manhood: the days spent beforehand with the other boys in the ‘seclusion lodges’; singing and dancing with local women on the night before the ceremony; bathing in the river at dawn; parading in blankets before the elders and the Regent himself, who watched the boys to see that they behaved with courage.

The old circumcisor (incibi) appeared with his assegai, and when their turn came the boys had to cry out ‘I am a man!’

Mandela was tense and anxious, and when the assegai cut off his foreskin he remembered it as feeling like molten lead flowing through his veins. He briefly forgot his words as he pressed his head into the grass, before he too shouted out, ‘I am a man!’ But he was conscious that he was not naturally brave: ‘I was not as forthright and strong as the other boys.’

After the ceremony was over, when they had buried their foreskins, covered their faces in white ochre and then washed it off in the river, Mandela was proud of his new status as a man, with a new name – Dalibunga, meaning the founder of the council – who could walk tall and face the challenges of life. He still felt himself to be part of a proud tribe, and was shocked when Chief Meligqili told the boys that they would never really be men because they were a conquered people who were slaves in their own country.

It was not until ten years later that Mandela would recognise that chief as the forerunner of brave politicians like Alfred Xuma and Yusuf Dadoo, James Phillips and Michael Harmel. In the meantime he would take great pride in his circumcised manliness and the superiority it implied; at university he was shocked to learn that one of his friends had not been circumcised. Only when he later became immersed in politics in Johannesburg did he, as he put it, ‘crawl out of the prejudice of my youth and accept all people as equals’.

Mandela soon had to make a more fundamental social transition – into the midst of a rigorous missionary schooling. The Regent was determined to have him properly educated, as a prospective counsellor to Sabata, the future king, so he sent him to board at the great Methodist institution of Clarkebury, across the Bashee river, which had educated both the Regent and his son Justice, and would educate Sabata. For the Tembu royal family Clarkebury had a special resonance: it was founded in 1825, when King Ngubengcuka, Mandela’s great-grandfather, had met the pioneering Methodist William Shaw and promised to give him land to set up a mission.

The station was duly founded by the Reverend Richard Haddy, some miles from the king’s Great Place, and named in honour of a distinguished British theologian, Dr Adam Clarke.

The Methodists were the most adventurous and influential of the missionaries who had penetrated the Eastern Cape at the same time as the British armies – sometimes in league with them, sometimes at odds. To many Xhosa patriots missionaries were essentially the agents of British governments, who used them to divide and disarm the rival chiefs: the Trotskyist writer ‘Nosipho Majeke’ wrote in 1952 that the Wesleyan missions were ‘ready at all times to co-operate with the Government’, and were able to surround the great King Hintsa, turning other chiefs against him.

But the mission teachers were frequently in opposition to white administrations, and played an independent role in the development of the Xhosa people. By 1935 the mission schools throughout South Africa registered 342,181 African pupils, and as the historian Leonard Thompson records, they ‘reached into every African reserve community’.

Mandela would retain a respect for the missionary tradition, while criticising its paternalism and links with imperialism. ‘Britain exercised a tremendous influence on our generation, at least,’ he has said, ‘because it was British liberals, missionaries, who started education in this country.’

Sixty years after his schooling, in a speech at Oxford University, he explained: ‘Until very recently the government of our country took no interest whatsoever in the education of blacks. Religious institutions built schools, equipped them, employed teachers and paid them salaries; therefore religion is in our blood. Without missionary institutions there would have been no Robert Mugabe, no Seretse Khama, no Oliver Tambo.’

In jail he would argue with Trotskyists who quoted Majeke’s attacks on the missionaries, and would welcome priests who brought encouragement and news from outside.

And he would write to some of his old mission teachers, to reminisce and to thank them. In prison he became more aware of the political influence of both the chieftaincy and the missions: ‘I have always considered it dangerous to underestimate the influence of both institutions amongst the people,’ he wrote. ‘And for this reason I have repeatedly urged caution in dealing with them.’

By the time of Mandela’s matriculation in 1934, Clarkebury had become the biggest educational centre in Tembuland, with a proud tradition of teaching, mainly by British missionaries. It had expanded into an imposing group of solid stone buildings, including a teacher-training college, a secondary school and training shops for practical courses, with boys’ and girls’ hostels, sports fields and tennis courts – a self-contained settlement dominating an isolated hillside in the Engcobo district, with its own busy community. Its past achievement would look all the more remarkable after the coming of Bantu Education in 1953, when it lost its funds and became a ruined shell, with only a small school and a Methodist chapel to maintain its continuity. Today it presents a tragic vista of crumbling buildings, collapsed roofs and gutted schoolrooms, burnt down by pupils rioting against the Transkei Bantustan government. There are still memorials of its past glory, including a plaque commemorating the Dalindyebo Mission School built in 1929. And some of the buildings are being restored, to provide a revived school: the rector explains that it will train Xhosas in how to create jobs, rather than to seek them, and that Mandela inspires local people to realise that small communities can produce great leaders. Mandela still revisits Clarkebury, talks and writes about it with warmth, and chose it as the location from which to launch a new version of his autobiography.

In 1934 Clarkebury was near the peak of its achievement. It was run by a formidable pedagogue, the Reverend Cecil Harris, who was closely involved with the local Xhosa communities and their chiefs. The Regent warned Mandela to treat Harris with suitable respect as ‘a Tembu at heart’, and Mandela shook his hand with awe – the first white hand he had ever shaken. Harris ruled Clarkebury with an iron hand, more like a field commander than a school head.

He had an aristocratic style, and walked like a soldier, which he had been in the First World War. ‘He was very stern dealing with the students,’ Mandela recalled; ‘severe with no levity.’

But Mandela also saw a much more human and friendly side of Harris and his wife when he worked in their garden. Years later, while in jail, he traced the address of the Harrises’ daughter Mavis Knipe, who had been a child when he was at Clarkebury. She was ‘flabbergasted’ to receive a letter from the famous prisoner.

Mandela reminded her how her mother would often bring him ‘a buttered scone or bread with jam, which to a boy of sixteen was like a royal feast’, and asked her for information about the Dalindyebo family: ‘At our age one becomes deeply interested in facts and events which as youths we brushed aside as uninteresting.’

Mandela was expecting the other pupils to treat him with respect, as a royal whose great-grandfather had founded the school. Instead he was mocked by one girl pupil for his country-boy’s accent, his slowness in class and for walking in his brand-new boots ‘like a horse in spurs’.

He found himself in a community which respected merit and intelligence more than hereditary status. But after the first shock he held his own, and with the benefit of his retentive memory he passed the Junior Certificate in two years. He also made some lasting friends, including Honourbrook Bala, later a prosperous doctor who joined the opposition in the Transkei and corresponded with Mandela in jail; Arthur Damane, who became a journalist on the radical paper the Guardian and was in jail with Mandela in Pretoria in 1960; Sidney Sidyiyo, the son of a teacher at Clarkebury who became a prominent musician; and Reuben Mfecane, who became a trades unionist in Port Elizabeth and, like Mandela, ended up on Robben Island.

Mandela was occasionally critical of the hierarchy at Clarkebury, and particularly of the food, which was minimal and at times almost inedible. But his first alma mater opened his eyes to the value of scientific knowledge, and introduced him to a much wider world than Tembuland, including as it did students from Johannesburg and beyond of both sexes – for unlike British public schools Clarkebury was co-educational. Even so, he still saw himself as a Tembu at heart, destined to advise his royal family, and continued to believe that ‘My roots were my destiny.’

After two years at Clarkebury Mandela was sent further away to Healdtown, a bigger Methodist institution, again following in the footsteps of Justice, the Regent’s son. Healdtown was almost as remote as Clarkebury: to reach it students had to walk ten miles from Fort Beaufort along a dirt road which wound through the valley, crossing and recrossing the stream, until it reached a cluster of fine Victorian buildings with red corrugated roofs, looking over a ravine. Today, like Clarkebury, the school is largely ruined. The handsome central block, with its picturesque clock-tower, has been restored and, sponsored by Coca-Cola, revived as the comprehensive high school; but most of the schoolrooms and houses are empty shells with smashed windows, rusty roofs and overgrown gardens, occupied by nothing but the ghosts of the old community on the hillside.

Healdtown, thirty years younger than Clarkebury, had an even more resonant history. It was established in 1855, after Sir Harry Smith had subjugated the surrounding Xhosa tribes, in the midst of the battle-areas. It was well placed as a British outpost, below the great escarpment of the Amatola hills where the defeated Xhosa had taken refuge, and surrounded by old military frontier-posts – Fort Beaufort, Fort Hare, Fort Brown. It was strictly Methodist, named after James Heald, a prominent Wesleyan Methodist British Member of Parliament, but it was also intended to serve as a practical experiment in training Fingo Christians in crafts and industry. That first experiment failed, but the college widened its scope and intake to become a teacher-training college and an important secondary school. By the 1930s it had over eight hundred boarders.

It was close to other great missionary educational centres such as Lovedale, St Matthew’s and Fort Hare, and together they comprised the greatest concentration of well-educated black students in Southern Africa.

Healdtown, like Clarkebury, offered an uncompromising British education with few concessions to Xhosa culture. The missionary and imperialist traditions often converged, particularly on Sundays, when the schoolboys and girls, in separate ranks, marched to church in their white shirts, black blazers and maroon-and-gold ties. The Union Jack was hoisted and they all sang ‘God Save the King’ and ‘Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika’, accompanied by the school brass band and watched by admiring visitors who came from far and wide.

The school governor since 1927 had been the Reverend Arthur Wellington – whom Mandela would always enjoy mimicking – a diehard English patriot who boasted of his descent from the victor of Waterloo. Wellington inculcated British history and literature in his students, assisted by a mainly English staff, and publicised the school by inviting eminent Britons to visit it, among them Lord Clarendon, the Governor-General of South Africa, who shortly before Mandela’s arrival had laid the foundation stones for the new dormitories and dining hall.

Wellington was a hard-driving autocrat – though he protested that he was naturally lazy – who claimed to run the largest educational institution south of the Sahara (Lovedale was in fact bigger).

He banned alcohol at Healdtown. His staff called him ‘the Duke’, and regarded him as a missionary-statesman. Under Wellington, wrote Jack Dugard, who ran the teacher-training school after 1932, ‘within a short time the once rather dowdy mission was transformed into an attractive education centre’.

The Methodism of Healdtown and Clarkebury did not make a deep religious impact on Mandela. He would never be a true believer, although many of his later friends, including his present wife, were educated by Methodists. But he would always be influenced by the schools’ puritanical atmosphere, the strict discipline and mental training, the Wesleyan emphasis on paring down ideas to their bare essentials, avoiding frills and distractions. He would always disapprove of heavy drinking or swearing; and the self-reliance in these boarding-school surroundings would add to his fortitude.

Mandela was immersed not just in Methodism, but in British history and geography. ‘As a teenager in the countryside I knew about London and Glasgow as much as I knew about Cape Town and Johannesburg,’ he would recall from jail fifty years later, writing to the Provost of Glasgow and mentioning Scots patriots like William Wallace, Robert the Bruce and the Earl of Argyll.

But he was resistant to becoming a ‘black Englishman’, and took great pride in his own Xhosa culture, encouraged by his history teacher, the much-liked Weaver Newana, who added his own oral history to the accounts of the Xhosa wars already familiar to the boy. Mandela won the prize for the best Xhosa essay in 1938; and he was thrilled when the famous Xhosa poet Krune Mkwayi visited the college, appearing in a kaross of hide, with two spears, to recite his dramatic poems in praise of the Xhosas.

Mandela made close friendships with several Xhosa boys who subsequently joined the ANC, including Jimmy Njongwe, with whom he later ‘starved and suffered in Johannesburg’, and who became a doctor and later a key organiser of the Defiance Campaign.

He also made friends outside his tribe among Sotho-speakers like Zachariah Molete, who later befriended him in Alexandra township in Johannesburg, and the zoology teacher Frank Lebentlele.

Mandela was much impressed by another Sotho-speaker, his housemaster the Reverend Seth Mokitimi, who later became the first black president of the Methodist Church; Mokitimi pushed through reforms to give students more freedom and better food.

The white teachers at Healdtown kept aloof from the black teachers, eating separately: one even had to resign after other teachers complained that he was fraternising with blacks. ‘What a racist place Healdtown was and continued to be!’ wrote Phyllis Ntantala, who was a student till 1935, and whose son Pallo Jordan would later join Mandela’s cabinet.

A few of the younger white teachers, though, were beginning to make friends with black colleagues and some students.