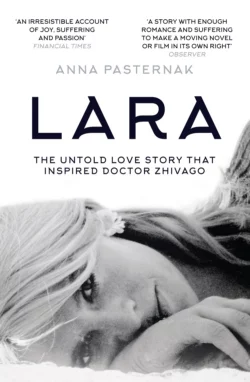

Lara: The Untold Love Story That Inspired Doctor Zhivago

Anna Pasternak

The heartbreaking story of the passionate love affair between Boris Pasternak and Olga Ivinskaya – the tragic true story that inspired Doctor Zhivago.‘Doctor Zhivago’ has sold in its millions yet the true love story that inspired it has never been fully explored. Pasternak would often say ‘Lara exists, go and meet her’, directing his visitors to the love of his life and literary muse, Olga Ivinskaya. They met in 1946 at the literary journal where she worked. Their relationship would last for the remainder of their lives.Olga paid an enormous price for loving ‘her Boria’. She became a pawn in a highly political game and was imprisoned twice in Siberian labour camps because of her association with him and his controversial work. Her story is one of unimaginable courage, loyalty, suffering, tragedy, drama and loss.Drawing on both archival and family sources, Anna Pasternak’s book reveals for the first time the critical role played by Olga in Boris’s life and argues that without Olga it is likely that Doctor Zhivago would never have been completed or published.Anna Pasternak is a writer and member of the famous Pasternak family. She is the great-granddaughter of Leonid Pasternak, the impressionist painter and Nobel Prize winning novelist Boris Pasternak was her great-uncle. She is the author of three previous books.

(#u13a841ec-62b0-54d6-bb0d-64135e14a6de)

COPYRIGHT (#u13a841ec-62b0-54d6-bb0d-64135e14a6de)

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com (http://www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com)

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2016

Copyright © Anna Pasternak 2016

Anna Pasternak asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

Cover image © Ullstein Bild/Getty

Interior images courtesy of the author unless otherwise attributed

Map and family tree © Martin Brown

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008156787

Ebook Edition © August 2016 ISBN: 9780008156800

Version: 2017-03-27

DEDICATION (#u13a841ec-62b0-54d6-bb0d-64135e14a6de)

In loving memory of my mother,

Audrey Pasternak

EPIGRAPH (#u13a841ec-62b0-54d6-bb0d-64135e14a6de)

Writers can be divided into two types: meteors and fixed stars. The first produces a momentary effect: you gaze up and cry ‘Look!’ – and they vanish forever. Whereas fixed stars are unchanging, they stand firm in the firmament, shine by their own light and influence all ages equally; they belong to the universe. But it is precisely because they are so high that their light usually takes so many years to reach the eyes of the dwellers on earth.

Arthur Schopenhauer

It is not for nothing that you stand at the end of my life, my secret, forbidden angel, under the skies of war and turmoil, you who arose at its beginning under the peaceful skies of childhood.

Yury Zhivago to Lara, Doctor Zhivago

CONTENTS

Cover (#uadc4a15b-d809-52e9-86b1-461ce03111e4)

Title Page (#u92761a91-6c3b-5e7c-9a01-9396296e4a4c)

Copyright (#u04dc03ad-0232-5432-8d8b-14f2a13350af)

Dedication (#u01358ce1-5dbb-5d8d-9a48-9375b4a31a1f)

Epigraph (#u97a2f94f-5d49-5e78-9fd4-cd70639d62fb)

Map (#u3e63e2f0-00da-5964-ba20-0cd508b7f23d)

Family Tree (#u1329c84d-64d3-5055-84a0-d588c92a300e)

Prologue: Straightening Cobwebs (#u692deb7d-fd52-5063-a4ae-4f25aee0e381)

1. A Girl from a Different World (#u230a7089-9f74-5ab6-bd48-38e76249d26f)

2. Mother Land and Wonder Papa (#u2df75df5-3020-51ec-9be2-c2dceeee89bd)

3. The Cloud Dweller (#u4dc8c177-f42b-5d39-9758-06ac52fa77ef)

4. Cables under High Tension (#u4e51844b-057f-59c2-b326-8967d6022d3f)

5. Marguerite in the Dungeon (#u0238f3c6-713d-5171-8e5f-07c05155fdcd)

6. Cranes Over Potma (#u89862ba1-5fa9-53e3-b920-6c5e8b6604c6)

7. A Fairy Tale (#udddf8612-f7f0-5a0f-80f3-42fd53ec5aa5)

8. The Italian Angel (#u3c33c80a-40a1-5895-87e8-b32dd19ba13d)

9. The Fat is in the Fire (#uc9b6acf3-2585-513a-a05f-cdb14680ba7f)

10. The Pasternak Affair (#u0508e5bc-ccd8-5158-8465-c5966d57e9ee)

11. A Beast at Bay (#uff995a73-c003-52f3-a1b7-96fe26fe5b32)

12. The Truth of Their Agony (#uc707c7f0-2ac9-55b2-b164-8797e5de787a)

Epilogue: Think of Me Then (#ua6196a9c-4f45-5796-920e-f57e22871e25)

Notes (#u0ce27a19-e491-513c-8dbf-d4842bed0969)

Select Bibliography (#udc0eecb1-a5d7-5e97-b699-6c8c96172724)

Acknowledgements and Note on Sources (#u87a8c918-6d46-5b68-8ab0-a67def2cb6a6)

Picture Section (#u07a7f0f1-5520-5499-88bc-df07deb58b5e)

Index (#u384fc0dc-26ed-5652-8fb6-1221c1a45c73)

About the Publisher (#uce77eb33-692a-53b3-a86c-9de87f0a68c4)

(#u13a841ec-62b0-54d6-bb0d-64135e14a6de)

(#u13a841ec-62b0-54d6-bb0d-64135e14a6de)

PROLOGUE

Straightening Cobwebs (#u13a841ec-62b0-54d6-bb0d-64135e14a6de)

It is almost impossible, by today’s standards of celebrity, to comprehend the level of fame that Boris Pasternak engendered in Russia from the 1920s onwards. Pasternak may be most famous in the West for writing the Nobel Prize-winning love story Doctor Zhivago, yet in Russia he is primarily recognised, and still hugely feted, as a poet. Born in 1890, his reputation escalated during his early thirties; soon he was filling large auditoriums with young students, revolutionaries and artists who gathered to hear recitals of his poems. If he paused for effect or for a momentary memory lapse, the entire crowd continued to roar the next line of his verse in unison back at him, just as they do at pop concerts today.

‘There was in Russia a very real contact between the poet, and the public, greater than anywhere else in Europe,’ Boris’s sister, Lydia, wrote of this time; ‘certainly far greater than is ever imaginable in England. Books of poetry were published in enormous editions and were sold out within a few days of publication. Posters were stuck up all over the town announcing poets’ gatherings and everyone interested in poetry (and who in Russia did not belong to this category?) flocked to the lecture room or forum to hear his favourite poet.’ The writer had immense influence in Russian society. In a time of unrest, with an absence of credible politicians, the public looked to its writers. The influence of literary journals was prodigious; they were powerful vehicles for political debate. Boris Pasternak was not only a popular poet hailed for his courage and sincerity. He was revered by a nation for his fearless voice.

From his early years Pasternak longed to write a great novel. He told his father, Leonid, in 1934: ‘Nothing I have written so far is of any significance. Hurriedly I am trying to transform myself into a writer of a Dickensian kind, and later – if I have enough strength to do it – into a poet in the manner of Pushkin. Do not imagine that I dream of comparing myself with them! I am naming them simply to give you an idea of my inner change.’ Pasternak dismissed his poetry as too easy to write. He had enjoyed unexpected, precocious success with his first published volume of poetry, Above the Barriers, in 1917. This became one of the most influential collections ever published in the Russian language. Critics praised the book’s biographical and historical material, marvelling at the contrasting lyrical and epic qualities. A. Manfred, writing in Kniga I revolyutsiya, observed a new ‘expressive clarity’ and of the author’s prospects of ‘growing into the revolution’. Pasternak’s second collection of twenty-two poems, My Sister, Life, published in 1922, received unprecedented literary acclaim. The exultant mood of the collection delighted readers as it conveyed the elation and optimism of the summer of 1917. Pasternak wrote that the February Revolution had happened ‘as if by mistake’ and everyone suddenly felt free. This was Boris’s ‘most celebrated book of poems’, observed his sister Lydia. ‘The more sophisticated younger generation of literary Russians went wild over the book.’ They considered that he wrote the finest love poetry, in thrall to his intimate imagery. After reading My Sister, Life, the poet Osip Mandelstam declared: ‘To read Pasternak’s verse is to clear your throat, to fortify your breathing, to fill your lungs: surely such poetry could provide a cure for tuberculosis. No poetry is more healthful at the present moment! It is koumiss [mare’s milk] after evaporated milk.’

‘My brother’s poems are without exception strictly rhythmical and written mostly in classical metre,’ Lydia wrote later. ‘Pasternak, like Mayakovsky, the most revolutionary of Russian poets, has never in his life written a single line of unrhythmic poetry, and this is not because of pedantic adherence to obsolete classical rules, but because instinctive feeling for rhythm and harmony were inborn qualities of his genius, and he simply could not write differently.’ In a poem written shortly after My Sister, Life was published, Boris bids farewell to poetry: ‘I will say so long to verse, my mania – I have an appointment with you in a novel.’ Still though, he glorified prose-writing as being too difficult. Yet the two modes of writing actually shared an intrinsic relationship in his work, regardless of the genre. In his autobiography Safe Conduct, published in 1931, a mannered account of his early life, travels and personal relationships, he wrote: ‘We drag everyday things into prose for the sake of poetry. We draw prose into poetry for the sake of music. This, then, I called art, in the widest sense of the word.’

It was in 1935 that Pasternak first spoke of his intent to fulfil his artistic potential by writing an epic Russian novel. And it was to my grandmother, his younger sister, Josephine Pasternak* (#ulink_642bad51-1574-517c-8a74-2a7beba3378c), that he first confided his ideas at their last meeting at Friedrichstrasse station in Berlin. Boris told Josephine that the seeds of a book were germinating in his mind; an iconic, enduring love story set in the period between the Russian Revolution and the Second World War.

Doctor Zhivago is based on Boris’s relationship with the love of his life, Olga Vsevolodovna Ivinskaya, who was to become the muse for Lara, the novel’s spirited heroine. Central to the novel is the passionate love affair shared by Yury Zhivago, a doctor and poet (a nod to the writer Anton Chekhov, who was also a doctor) and Lara Guichard, the heroine, who becomes a nurse. Their love is tormented as Yury, like Boris, is married. Yury’s diligent wife, Tonya, is based on Boris’s second wife, Zinaida Neigaus. Yury Zhivago is a semi-autobiographical hero; this is the book of a survivor.

Doctor Zhivago has sold in its millions yet the true love story behind it has never been fully explored before. The role of Olga Ivinskaya in Boris’s life has been consistently repressed both by the Pasternak family and Boris’s biographers. Olga has regularly been belittled and dismissed as an ‘adventurous’, ‘a temptress’, a woman on the make, a bit part in the history of the man and his book. When Pasternak started writing the novel, he had not yet met Olga. Lara’s teenage trauma of being seduced by the much older Victor Komarovsky is a direct echo of Zinaida’s experiences with her sexually predatory cousin. However, as soon as Boris met and fell in love with Olga, his Lara changed and flowered to completely embody her.

Historically both Olga and her daughter, Irina, have received a bad rap from my family. The Pasternaks have always been keen to play down the role of Olga in Boris’s life and literary achievements. They held Boris in such high esteem that for him to have had two wives – Evgenia and Zinaida – and a public mistress was indigestible to their staunch moral code. By accepting Olga’s place in Boris’s life and affections, they would have had to further acknowledge his moral fallibility.

Shortly before she died, Josephine Pasternak told me furiously: ‘It is a mistaken idea that this … acquaintance ever appeared in Zhivago.’ In fact, her feelings for ‘that seductress’ were so strong that she refused to ever sully her lips with her name. She was in denial, blinded by her reverence for her brother. Even though in Boris’s last letter to her, written on 22 August 1958, he tells his sister that he hopes to travel in Russia ‘with Olga’, underlining the importance of his mistress in his life, Josephine would not acknowledge her existence. Evgeny Pasternak, Boris’s son by his first wife, was more pragmatic. He may not have liked Olga, displaying little warmth towards her, yet he was more accepting of the situation. ‘It was lucky that my father had the love of Lara,’ he told me shortly before he died in 2012, aged eighty-nine. ‘My father needed her. He would say “Lara exists, go and meet her.” This was a compliment.’

It was not until 1946 that fate intervened, when Boris was fifty-six years old. As he later wrote in Doctor Zhivago, ‘From the bottom of the sea the tide of destiny washed her up to him’. It was at the offices of the literary journal Novy Mir that he met thirty-four-year-old Olga Ivinskaya, an editorial assistant. She was blonde and cherubically pretty, with cornflower-blue eyes and enviably translucent skin. Her manner was beguiling – highly strung and intense, yet with an underlying fragility, hinting at the durability of a survivor. She was already a dedicated fan of Pasternak the ‘poet hero’. Their attraction was mutual and instant, and it is easy to see why they were drawn to each other. Both were melodramatic romantics given to extraordinary flights of fantasy. ‘And now there he was at my desk by the window,’ she later wrote, ‘the most unstinting man in the world, to whom it had been given to speak in the name of the clouds, the stars and the wind, who had also found eternal words to say about man’s passion and woman’s weakness. People say that he summons the stars to his table and the whole world to the carpet at his bedside.’

Having become fascinated with my great-uncle’s love story, I feel passionately that if it were not for Olga, not only would Doctor Zhivago never have been completed but it would never have been published. Olga Ivinskaya paid an enormous price for loving ‘her Boria’. She became a pawn in a highly political game. Her story is one of unimaginable courage, loyalty, suffering, tragedy, drama and loss.

From the mid-1920s, as Stalin came to power after Lenin’s death, it was established that communism would not tolerate individual tendencies. Stalin, an anti-intellectual, described writers as the ‘engineers of the soul’ and regarded them as having an influential potency that needed to be channelled into the collective interests of the state. He began his drive for collectivisation and with it mass terror. The atmosphere for poets and authors, expressing their own individual creativity, became unbearably oppressive. After 1917 nearly 1,500 writers in the Soviet Union were executed or died in labour camps for alleged infractions. Under Lenin, indiscriminate arrests had become part of the system, as it was believed to be in the interest of the state to incarcerate a hundred innocent people rather than let one enemy of the regime go free. The atmosphere of fear, of people informing on colleagues or former writer friends, was actively encouraged in Stalin’s new stifling regime where everyone was fighting to survive. Many writers and artists, terrified of persecution, committed suicide. Where Pasternak’s semi-autobiographical hero Yury Zhivago dies in 1929, Boris himself survived, though refusing to kowtow to the literary and political diktats of the day.

Stalin, who had a special admiration for Boris Pasternak, did not imprison the controversial writer; instead he harassed and persecuted his lover. Twice Olga Ivinskaya was sentenced to periods in labour camps. She was interrogated about the book Boris was writing, yet she refused to betray the man she loved. The leniency with which Stalin treated Pasternak did not diminish the author’s outrage towards his country’s leader; he was, he lamented, ‘a terrible man who drenched Russia in blood’. During this time an estimated 20 million people were killed, and 28 million deported, most of whom were put to work as slaves in the ‘correctional labour camps’. Olga was one of the millions sent gratuitously to the gulag, precious years of her life stolen from her due to her relationship with Pasternak.

In 1934 Alexei Surkov, a poet and budding party functionary, gave a speech at the First Congress of the Soviet Writers’ Union that summed up the Soviet view: ‘The immense talent of B. L. Pasternak will never fully reveal itself until he has attached himself fully to the gigantic, rich and radiant subject matter [offered by] the Revolution; and he will become a great poet only when he has organically absorbed the Revolution into himself.’ When Pasternak saw the reality of the Revolution, that his beloved Russia had had its ‘roof torn off’, as he put it, he wrote his own version of history in Doctor Zhivago, defiantly criticising the tyrannical regime. In it Yury says to Lara:

Revolutionaries who take the law into their own hands are horrifying, not as criminals, but as machines that have got out of control, like a run-away train … But it turns out that those who inspired the revolution aren’t at home in anything except change and turmoil: that’s their native element; they aren’t happy with anything that’s less than on a world scale. For them, transitional periods, worlds in the making, are an end in themselves. They aren’t trained for anything else, they don’t know about anything except that. And do you know why there is this incessant whirl of never-ending preparations? It’s because they haven’t any real capacities, they are ungifted.

In the last century few literary works created such a furore as Doctor Zhivago. It was not until 1957, over twenty years after Pasternak first confided in Josephine, that the book was published, initially in Italy. Despite being an instant, international bestseller, and even though Pasternak was then seen as Russia’s ‘greatest living writer’, it was over thirty years later, in 1988, that his book, regarded as anti-revolutionary and unpatriotic, was legitimately published in his adored ‘Mother Russia’. The cultural critic Dmitry Likhachev, who was considered the world’s foremost expert in Old Russian language and literature in the late twentieth century, said that Doctor Zhivago was not really a traditional novel but was rather ‘a kind of autobiography’ of the poet’s inner life. The hero, he believed, was not an active agent but a window on the Russian Revolution.

In 1965 David Lean made film history with his adaptation of Pasternak’s novel, in which Julie Christie was cast as the heroine, Lara, and Omar Sharif as the hero, Yury Zhivago. The film won five Academy Awards and was nominated for five more. Lean’s Hollywood classic has left millions of viewers with images as magic and endurable as Pasternak’s prose. It is the eighth highest-grossing film in American film history. Robert Bolt, who won an Academy Award for the screenplay, said of adapting Pasternak’s work: ‘I’ve never done anything so difficult. It’s like straightening cobwebs.’ Omar Sharif said of it: ‘Doctor Zhivago encompasses but does not overwhelm the human spirit. That is Boris Pasternak’s gift.’ Of the enduring quality of the story, he concluded: ‘He proves that true love is timeless. Doctor Zhivago was and always will be a classic for all generations.’

There is a Russian proverb: ‘You cannot know Russia through your head. You can only understand her through your heart.’ When I visited Russia for the first time, walking around Moscow was like being haunted, as I had the sense not of being a tourist but of coming home. It was not that Moscow was familiar to me but it did not feel foreign either. I marched through the snow one wintry February night, up the wide Tverskaya Street, to dinner at the Café Pushkin restaurant, acutely conscious that Boris and Olga had used the same route many times during their courtship, over sixty years earlier, treading the very same pavements.

Sitting amid the flickering candlelight of the Café Pushkin, which is styled to resemble a Russian aristocrat’s home of the 1820s – with its galleried library, book-lined walls, elaborate cornices, frescoed ceilings and distinct grandeur – I felt the hand of history gently resting on me. The restaurant is close to the old offices of Novy Mir, Olga’s former workplace on Pushkin Square. I imagined Olga and Boris walking past, their heads bowed low and close against the snow, wrapped in heavy coats, their hearts full of desire.

Five years later, on another visit to Moscow, I went to the Pushkin statue, erected in 1898, where Boris and Olga frequently rendezvoused during the early stages of their relationship. It was here that Boris first confessed the depth of his feelings to Olga. The vast statue of Pushkin was moved in 1950 from one side of Pushkin Square to the other, so they would have started their courtship on the west side of the square and moved to the east side in 1950 where I stood, looking up at the giant bronze folds of Pushkin’s majestic cape tumbling down his back. My Moscow guide, Marina, a fan of Putin and the current regime, looked at me standing under Pushkin’s statue, envisaging Boris at that very spot, and said: ‘Boris Pasternak is an inhabitant of heaven. He is an idol for so many of us, even those who are not interested in poetry.’

This reverential view echoed my meeting with Olga’s daughter, Irina Emelianova, in Paris a few months earlier. ‘I thank God for the chance to have met this great poet,’ she told me. ‘We fell in love with the poet before the man. I always loved poetry and my mother loved his poetry, just as generations of Russians have. You cannot imagine how remarkable it was to have Boris Leonidovich [his Russian patronymic name† (#ulink_38859b4f-a444-510e-a369-fd41b8902049)] not just in the pages of our poetry but in our lives.’

Irina was immortalised by Pasternak as Lara’s daughter, Katenka, in Doctor Zhivago. Growing up, Irina became incredibly close to Boris. He loved her as the daughter he never had and was more of a father figure to her than any other man in her life. Irina got up from the table we were sitting at and retrieved a book from her well-stocked shelves. It was a translation of Goethe’s Faust which Boris had given her, and on the title page was a dedication in Boris’s bold, looping handwriting in black ink, ‘like cranes soaring over the page’ as Olga once described it. Inside, Boris had written in Russian to the then seventeen-year-old Irina: ‘Irochka, this is your copy. I trust you and I believe in your future. Be bold in your soul and mind, in your dreams and purposes. Put your faith in nature, in the spirit of your destiny, in events of significance – and only in such few people as have been tested a thousand times, and are worthy of your confidence.’

Irina proudly read the final inscription to me. Boris had written: ‘Almost like a father, Your BP. November 3, 1955, Peredelkino.’ As she ran her hand affectionately across the page, she said sadly: ‘It’s a shame that the ink will fade.’

It was a timeless moment, as we both stared at the page, considering perhaps that everything precious in life eventually ebbs away. Irina closed the book, straightened her shoulders, and said: ‘You cannot imagine how knowing Boris Pasternak altered our lives. I would go and listen to his poetry recitals and I was the envy of my friends at school and my English professor and the teachers. “You know Boris Leonidovich?” they would ask me in awe. “Can you get the latest poem from him?” I would ask his typist if we could just have one line of his verse and sometimes he would distribute a poem for me to hand out. That gave me incredible prestige at school and in a way his glory rubbed off on me.’

The Russian people’s reverence for Pasternak, which remains to this day, is not just because of the enduring power of his writing, but because he never wavered in his loyalty to Russia. His great love was for his Motherland; in the end, that was stronger than everything. He renounced the Nobel Prize for Literature when the Soviet authorities threatened that if he left his country, he would not be allowed to return. And he never became an émigré, refusing to follow his parents to Germany, then England, after the 1917 Revolution.

When I went to Peredelkino, to the writer’s colony, a fifty-minute drive from central Moscow, where Boris spent nearly two decades writing Doctor Zhivago, I felt a profound sadness. As I sat at Boris’s desk in his study on the upper floor of his dacha, I traced the faint ring marks his coffee cups had left on the wood over fifty years earlier. Icicles hung outside the window, reminiscent of David Lean’s film: I was reminded of Varykino, the abandoned estate in the novel, where Yury spends his last days with Lara, dazzling in the sun and snow; the lacework of hoar frost on the frozen window panes; the crystalline magic conjured on screen; Julie Christie, embodying his Lara, effortlessly beautiful beneath her fur hat. I thought of my great-uncle Boris looking out of the window, across the garden he adored, past the pine trees to the Church of Transfiguration. In the distance lies Peredelkino cemetery, where he is buried. Earlier that day, my father, Boris’s nephew, and I had trudged through deep snowdrifts in the cemetery to visit his grave, where I was touched to find a bouquet of frozen long-stemmed pink roses carefully placed against his headstone. They must have been left there by a fan. I was struck that no words of Boris’s adorn his grave. Just his face etched into the stone. Powerful in its simplicity, nothing more needs to be said.

I leaned back in Boris’s chair in his study and considered how often he must have turned back from the undulating view to his page (he wrote in longhand), inspired, to create scenes of longing between Yury and Lara. When I was there the snow was gently falling outside, enhancing the stillness. The room is almost painful in its plainness. In one corner stands a small wrought-iron bed with a sketch of Tolstoy hanging above it and family drawings by Boris’s father, Leonid, to each side. With its drab grey patterned cover and the reddish brown cut-out square of carpet close by, the bed would not have been out of place in a monastic cell. Opposite, a bookcase: the Russian Bible, works by Einstein, the collected poems of W. H. Auden, T. S. Eliot, Dylan Thomas, Emily Dickinson, novels by Henry James, the autobiography of Yeats and the complete works of Virginia Woolf (Josephine Pasternak’s favourite author), along with Shakespeare and the teachings of Jawaharlal Nehru. Facing the desk, on an artist’s easel, a large black and white photograph of Boris himself. Wearing a black suit, white shirt and dark tie, I considered that he looked about my age, mid-forties. Pain, passion, determination, resignation, fear and fury emanate from his eyes. His lips are almost pursed, set with conviction. There was nothing soft or yielding about his sanctuary; he saved his sensuousness for his prose.

I thought about Boris’s courage, a courage that meant he could sit there and write his truth about Russia. How he defiantly stared the Soviet authorities in the face, and how persecution and the threat of death eventually took its toll. How, despite outliving Stalin, in spite of his colossal literary achievements, he lived his last years here in imposed isolation, the Soviet authorities watching and monitoring his every move. His study became his personal quarantine: writing upstairs; his wife Zinaida downstairs, chain-smoking as she played cards or watched the clunky antique Soviet television, one of the first ever made.

And I imagined his lover Olga Ivinskaya, in the last years of Boris’s life, anxiously waiting for him every afternoon to join her in the ‘Little House’ across the lake at Izmalkovo, a kilometre away. Here she would soothe and support, encourage and type up his manuscripts. Not visible in his home by way of cherished photograph or painting, her absence is jarring. For what is the love story in Doctor Zhivago if it is not his passionate cri de coeur to Olga? I thought of her endlessly reassuring him of his talent when the authorities taunted that he had none; how she brought fun and tenderness into his life when everything else was so strategic, harsh, political and fraught. How she loved him but, just as crucially, how she understood him. Many artists are selfish and self-indulgent, as he was. It would be easy to conclude that Boris used Olga. It is my intention to show that, rather, his great omission was that he did not match her cast-iron loyalty and moral fortitude. He did not do the one thing in his power to do: he did not save her.

Looking around his study for the last time, I knew that I wanted to write a book which would try to explain why he performed this uncharacteristic act of moral cowardice, putting his ambition before his heart. If I could understand why he behaved as he did and appreciate the extent of his suffering and self-attack, could I forgive him for letting himself and his true love down? For not publicly claiming or honouring Olga – for not marrying her – when she was to risk her life loving him? As he writes in Doctor Zhivago: ‘How well he loved her, and how loveable she was in exactly the way he had always thought and dreamed and needed … She was lovely by virtue of the matchlessly simple and swift line which the Creator at a single stroke had drawn round her, and in this divine outline she had been handed over, like a child tightly wound up in a sheet after its bath, into the keeping of his soul.’

* (#ulink_18a3bc60-6d8e-5245-8182-f754e34a8776) Josephine married her cousin, Frederick Pasternak, hence the continuation of the surname.

† (#ulink_544d593f-9238-5b87-8a42-3e1d31e88ec7) Every Russian has three names. A first name, a patronymic and a surname. The patronymic name is derived from the father’s first name. The usual form of address among adults is the first name and the patronymic.

1

A Girl from a Different World (#u13a841ec-62b0-54d6-bb0d-64135e14a6de)

Novy Mir, meaning ‘New World’, the leading Soviet literary monthly where Olga Ivinskaya worked, was set up in 1925. Literary journals such as Novy Mir, the official organ of the Writers’ Union of the USSR, enjoyed huge influence in the Stalinist period and had a readership of tens of millions. They were vehicles for political ideas in a country where debate was harshly censored, and the contributors held enormous sway in Russian society. The offices in Pushkin Square were situated in a grand former ballroom, painted a rich dark red with gilded cornices, where Pushkin once danced. The magazine’s editor, the poet and author Konstantin Simonov, a flamboyant figure with a silvery mane of hair who sported chunky signet rings and the latest style of American loose-fitting suits, was keen to attract ‘living classics’ to the journal, and counted Pavel Antokolsky, Nicolai Chukovski and Boris Pasternak among its contributors. Olga was in charge of the section for new authors.

On an icy October day in 1946, just as a fine snow was beginning to swirl outside the windows, Olga was about to go for lunch with her friend Natasha Bianchi, the magazine’s production manager. As she pulled on her squirrel fur coat, her colleague Zinaida Piddubnaya interrupted: ‘Boris Leonidovich, let me introduce one of your most ardent admirers,’ gesturing to Olga.

Olga was stunned when ‘this God’ appeared before her and ‘stood there on the carpet and smiled at me’. Boldly, she held out her hand for him to kiss. Boris bent over her hand and asked what books of his she had. Astounded and ecstatic to be face-to-face with her idol, Olga replied that she only had one. He looked surprised. ‘Oh, I’ll get you some others,’ he said, ‘though I’ve given almost all my copies away …’ Boris explained that he was mainly doing translation work and hardly writing any poems at all due to the repressive strictures of the day. He told her that he was still translating Shakespeare plays.

Throughout his writing career, Pasternak earned the bulk of his income through commissioned translation work. Proficient in several languages, including French, German and English, he was deeply interested in the intricacies and dilemmas of translating. Gifted in interpreting, and conveying a colloquial essence, he was to become Russia’s premiere translator of Shakespeare, and would be nominated for the Nobel Prize six times for his accomplishments in this area. In 1943 the British embassy had written to him with compliments and gratitude for his efforts translating the Bard. The work provided several years of steady income. He told a friend in 1945: ‘Shakespeare, the old man of Chistopol, is feeding me as before.’

‘I’ve started on a novel,’ he told Olga at Novy Mir, ‘though I’m not yet sure what kind of thing it will turn out to be. I want to go back to the old Moscow – which you don’t remember – and talk about art, and put down some thoughts.’ At this stage, the novel’s draft title was ‘Boys and Girls’. He paused, before adding a little awkwardly: ‘how interesting that I still have admirers …’. Even at the age of fifty-six, more than twenty years Olga’s senior, Pasternak was considered handsome in a strong, striking way, despite the fact that his elongated face was often likened to an Arab horse’s – hardly flattering – partly because he had long yellowish teeth. It seems slightly disingenuous that Boris should have questioned that he had admirers – a faux modesty – when he knew perfectly well that he had a hypnotic effect on people, and that men and women everywhere were in awe of him. The Russian poet Andrei Voznesensky, to whom Pasternak would become a mentor figure, was captivated by the poet’s dazzling presence the first time he met him, that same year, 1946:

Boris Leonidovich started talking, going straight to the point. His cheekbones would twitch, like the triangular shaped cases of wings pressed tight shut, prior to opening. I worshipped him. There was a magnetic quality about him, great strength and celestial otherworldliness. When he spoke, he would jerk his chin, thrusting it up, as if trying to break free of his collar and body. His short nose hooked right from the bridge, then went straight, making one think of the butt of a gun in miniature. The lips of a sphinx. Grey hair, cropped short. But, overshadowing everything else, was the pulsating wave of magnetism that flowed from him.

All through his life women pursued Boris Pasternak. Yet he was no quasi-Don Juanesque character; quite the opposite. He revered women, feeling an innate empathy for them because he saw that for women, as for poets, things could often become complex and entangled in their emotional and sentimental lives. His fateful meeting with Olga at Novy Mir was to become the greatest entanglement, enmeshing his emotional and creative lives.

After exchanging a few words with Zinaida Piddubnaya, he kissed both women’s hands and left. Olga stood there, speechless. It was one of those life-changing moments when she felt the axis of her world tilt. ‘I was simply shaken by the sense of fate when my “god” looked at me with his penetrating eyes. The way he looked at me was so imperious, it was so much a man’s appraising gaze that there could be no mistake about it; here he was, the one person I needed more than any other, the very one who was in actual fact already part of me. A thing like this is stunning, a miracle.’

In Doctor Zhivago the reader is introduced to Lara in chapter two, ‘A Girl from a Different World’. Yury Zhivago’s first impressions of Lara are based on Boris’s early meetings with Olga: ‘“She has no coquetry,” he thought. “She does not wish to please or to look beautiful. She despises all that side of a woman’s life, it’s as though she were punishing herself for being lovely. But this proud hostility to herself makes her more attractive than ever.”’

There was an instant attraction between Boris and Olga, recalled Irina: ‘Boris was sensitive to my mother’s kind of beauty. It was a tired beauty. It wasn’t the beauty of a brilliant victor, it was almost the beauty of a defeated victim. It was the beauty of suffering. When Boris looked into my mother’s beautiful eyes, he could probably see many, many things in them.’

The following day, Pasternak sent Olga a parcel. Five slim volumes of his poems and translations appeared on her desk at the offices at Novy Mir. His tenacious pursuit of her had begun.

Olga had first set eyes on him fourteen years earlier, when, as a student at the Moscow Faculty of Literature, she went to one of Pasternak’s poetry recitals. She was hurrying through the corridor to get to her seat at Herzen House, Moscow, anxious to hear the ‘poet hero’ recite his famous poem ‘Marburg’, which chronicled his first experience of love and rejection. Suddenly, as the bell rang to announce the performance, the nervous black-haired poet rushed past her. He had an electric energy, she thought, which made him seem ‘dishevelled and on fire’. When he finished his recital, the excitable crowd surged forwards to surround him. Olga watched as a handkerchief belonging to him was torn to shreds and even the remaining crumbs of tobacco from his cigarette butts were snatched up by fans as meaningful keepsakes.

Over a decade later, in 1946, when Olga was thirty-four, she was given a ticket to an evening in the library of the Historical Museum where Pasternak was to read from his Shakespeare translations. The Russian writer had been first introduced to the works of the English playwright by his first love, Ida Davidovna Vysotskaya, when he was at Marburg University; Ida was the inspiration for his poem ‘Marburg’. The daughter of a wealthy Moscow merchant, she had been tutored by Boris as a young girl. Ida and her sister visited Cambridge in 1912, where she discovered Shakespeare and English poetry. She spent three days with Boris in Marburg later that summer, presenting her serious-minded friend with an edition of Shakespeare’s plays and indirectly giving birth to a fresh calling.

On 5 November 1939, Pasternak’s translation of Hamlet, which had been commissioned by the great theatre director Vsevolod Meyerhold, had been accepted for staging at the Moscow Art Theatre. This made Pasternak immeasurably proud, not least because the 1930s had been a decade filled with terror and frustration for him. Just as Pasternak had warmed to the task of writing his novel, external circumstances kept him from fulfilling his creative dream. At first, he was hampered by financial need, later by isolation, depression and fear. In 1933 he had written to Maksim Gorky, the godfather of Soviet letters and the founder of the ‘socialist realism’ literary style, that he needed to write short works and publish quickly in order to support his family, which after divorce and remarriage had doubled in size. Already, Pasternak’s attitude to his work was one of risk-taking. Completely against being any sort of mouthpiece for Soviet propaganda, he believed it a moral imperative that he write the truth about the age. He considered it dishonest to be in a privileged position against a backdrop of universal deprivation. Yet publication of his work was regularly delayed by censorship problems.

In August 1929, the whole literary community were affected by an issue that broke out in the press. During the 1920s it was frequent practice among Soviet authors to publish works abroad to secure international copyright (the USSR was not a signatory to any international copyright convention) and to circumvent official censorship. On 26 August the Soviet press accused two authors, Evgenyi Zamyatin and Boris Pilnyak, who published abroad, of major acts of treachery involving anti-Soviet slander. The party- and state-organised campaign of vilification played out in the press lasted several weeks, leaving the writing community in a state of fear and insecurity. In the end Zamyatin emigrated to France and Pilnyak was forced to resign from the Writers’ Union. Pasternak took these cases closely to heart as he shared stylistic features and close personal relations with the two writers. These literary witch hunts coincided with the collectivisation of agriculture. Over the next few years, its violent enactment would devastate the rural economy and destroy the lives of millions.

On 21 September 1932 Pasternak added a note to a collection of poems under preparation at the Federatsiya state publishing house. ‘The Revolution is so unbelievably harsh towards the hundreds of thousands and the millions: yet so gentle towards those with qualifications and those with assured positions.’ Openly voicing the struggles of this oppressive and cruel period of post-revolutionary Russia through his poetry quickly brought counterattacks and noises of displeasure from Soviet authorities. Boris continued fearlessly. As his son Evgeny commented: he ‘had to become the witness to truth and the conscience-bearer for his age’. Perhaps this is because Boris took his own father’s advice to heart. ‘Be honest in your art,’ Leonid Pasternak had encouraged him; ‘then your enemies will be powerless against you.’

During the summer of 1930 Pasternak composed the poem ‘To a Friend’, bravely addressing it ‘To Boris Pilnyak’ whose recent novella, Mahogany, which presented an idealised portrait of a Trotskyite communist, had been published in Berlin and banned in the Soviet Union. Pasternak’s poem was published in Novy Mir in 1931 and in a reprint that year of Above the Barriers. Written as a statement of solidarity with Pilnyak, and as a warning that writers were under assault, it drew damning comment from Pasternak’s orthodox colleagues and critics. Paradoxically it caused more controversy than the stance taken by Pilnyak and his novella. In ‘To a Friend’, Pasternak wrote:

And is it not true that my personal measure

Is the Five-Year Plan, its rise and its fall?

Yet what can I do with my rib-cage’s pressure

And with my inertia, most sluggish of all?

In vain in our day, when the Soviet’s at work

By high passion all seats on the stage have been taken.

But the poet has forsaken the place they reserved.

When that place is not vacant, the poet is in danger

By 1933, it had become clear that collectivisation – during which at least five million peasants died – had been a terrible and irreversible disaster. As Pasternak would write in Zhivago: ‘I think that collectivisation was both a mistake and a failure, and because that couldn’t be admitted, every means of intimidation had to be used to make people forget how to think and judge for themselves, to force them to see what wasn’t there, and to maintain the contrary of what their eyes told them … And when the war broke out, its real horrors, its real dangers, its menace of real death, were a blessing compared with the inhuman power of the lie, a relief because it broke the spell of the dead letter.’ At another point Yury says to Lara: ‘everything established, settled, everything to do with home and order and the common round, has crumbled into dust and been swept away in the general upheaval and reorganisation of the whole of society. The whole human way of life has been destroyed and ruined. All that’s left is the bare, shivering human soul, stripped to the last shred … ’

During the Great Terror in the 1930s, during which much of the old Bolshevik elite, generals, writers and artists perished, Pasternak was increasingly forced to retreat into silence, sure that he too would not have to wait long for the late-night knock at his door. His fear and distress were compounded when soon after Vsevolod Meyerhold had invited him to translate Hamlet, the director and his wife, Zinaida Raikh, perished at the hands of the secret police. Boris valiantly persisted in his translation, finding in it ‘the mental space to escape constant fear’.

His courage paid off. On 14 April 1940 he was asked to read his Hamlet aloud at the Moscow Writers’ Club. Of the evening, he wrote to his cousin Olga Freidenberg: ‘The highest incomparable delight is to read aloud, without cuts, even though it is only half of your work. For three hours you are feeling Man in the highest sense, independent, hot for three hours, you are in spheres you know from the day you were born, from the first half of your life, and then, exhausted, with your energy spent, you are falling back down, nobody knows where to come back to reality.’

The first time that Olga Ivinskaya saw Boris properly, at close range, and ‘feeling Man’ and ‘hot for three hours’, was the autumn evening in 1946 when he read out his Shakespeare translations at the Moscow museum library. She found him ‘tall and trim, extraordinarily youthful, with the strong neck of a young man, and he spoke in a deep, low voice, conversing with the audience as one talks with an intimate friend or communes with oneself’. In the interval some of the audience summoned up the courage to ask him to read work of his own, but he declined, explaining that the evening was supposed to be devoted to Shakespeare and not to himself. Olga was too nervous to join the ‘privileged people’ brave enough to approach the writer, and left. She arrived home after midnight and, having forgotten her door key, was forced to wake her mother. When her mother angrily reprimanded her, Olga retorted: ‘Leave me alone, I’ve just been talking to God!’

Olga had spent her adolescent years, along with her friends at school and ‘everybody else of my age’, infatuated with Boris Pasternak. As a teenager she frequently wandered through the streets of Moscow repeating the seductive lines of his poetry over and over to herself. She knew ‘instinctively that these were the words of a god, of the all-powerful “god of detail” and “god of love”.’ When as a teenager she went for her first trip to the sea, in the south, a friend gave her a small volume of Pasternak’s prose, The Childhood of Luvers. Lilac-coloured and shaped like an elongated school exercise book, the binding was rough to the touch. This novella, which Boris started writing in 1917 and had published in 1922, was his first work of prose fiction. Originally published in the Nashia Dni almanac, Pasternak wanted this to be the first part of a novel about the coming-into-consciousness of a young girl, Zhenia Luvers, the daughter of a Belgian factory director in the Urals. Although Zhenia Luvers has typically been viewed as the prototype for Lara in Doctor Zhivago, Pasternak based much of the characterisation on the childhood of his sister, Josephine.

Lying on the upper bunk of her sleeping compartment, as the train sped south, Olga tried to fathom how a man could have such insight into a young girl’s secret world. Like many of her peers, she often found it hard to understand Pasternak’s poetic images, as she was accustomed to more traditional verse. ‘But the answers were already in the air all around us,’ she wrote. ‘Spring could be recognised by its “little bundle of laundry/of a patient leaving hospital”. Those “candle-drippings” stuck on the branches in springtime did not have to be called “buds” – it was sorcery and a miracle. It gave you the feeling of personally discovering something hitherto unknown and locked away by a god behind a closed door.’ Olga could now barely believe that the ‘magician who had first entered my life so long ago, when I was sixteen, had now come to me in person, living and real’.

Their courtship moved at a furious pace. Not for one moment did Boris attempt to hide his attraction for the beguiling editor, nor fight his desire for her. He phoned her every day at her offices, where Olga, ‘dying of happiness’ yet fearing to meet or talk with the poet, always told Pasternak that she was busy. Undeterred, her suitor arrived at the offices every afternoon. He walked her home through the boulevards of Moscow to her apartment in Potapov Street, where she lived with her son and daughter, Mitia and Irina, and her mother and stepfather.

As both Boris and Olga had family at home, most of their initial romance was spent walking the wide streets of Moscow, talking. They met at the memorials of great writers; their usual rendezvous was by the Pushkin statue in Pushkinskaya Square, at the crossing of Tverskoy Boulevard and Tverskaya Street. On one of their city walks, they passed a manhole cover with the name of the industrialist ‘Zhivago’ written on it. The translation of Zhivago is ‘life’ or ‘Doctor Lively’ and Boris was suitably inspired by the name. As he fell in love with Olga, finding his true Lara, he changed the working title of the novel, from Boys and Girls to Doctor Zhivago.

In the new year, on 4 January 1947, Olga received her first note from Boris: ‘Once again I send you all best wishes from the bottom of my heart. Wish me godspeed (cast a spell over me in your thoughts!) with the revision of Hamlet and 1905, and a new start on my work. You are very marvellous, and I want you to be well. B.P. ’ Although Olga was pleased to have her first written communication from her esteemed admirer, she was a little disappointed by the tone of cool formality. The romantic in her, hoping for something warmer, worried that this was his way of warding her off. She need not have been concerned. For the obsessive writer wooing his young beauty, soon even daily contact with Olga was not enough.

Because Olga had no telephone in her apartment, and as Boris wanted to speak to her in the evenings as well, she boldly gave him the number of her neighbours, the Volkovas, who lived below them on the same staircase and were the proud owners of a telephone – rare in Moscow at that time. Every evening Olga would hear a Morse code-like knocking on the hot-water pipes, a signal that Pasternak was on the telephone for her. She would knock back on the damp walls of her apartment, before rushing downstairs, eager just to hear the distinctive voice of the man she was falling in love with. ‘When she would come back a few moments later, her face would be somewhere else, like it was facing inwards,’ remembered Irina. ‘For a whole year, their meetings would take place in the midst of reproaches, knocks on walls, constant surveillance until one day, faced with the ineluctability of their passion, it was decided that our family would officially meet Pasternak.’

The day before, Boris had called Olga at her office and told her that he had to see her as he had two important things to say to her. He asked her to meet him as soon as she could at the Pushkin statue. When Olga arrived, taking a quick break from work, Boris was already there, pacing up and down, agitated. He spoke in an awkward tone, quite unlike his usual voice of bellowing confidence. ‘Don’t look at me for a moment, while I tell you briefly what I want,’ he instructed Olga. ‘I want you to say “thou” to me because “you” is by now a lie.’

In terms of their courtship, this was a significant step forwards, away from the formality of ‘you’, to the familiarity of ‘thou’.

‘I cannot call you “thou” Boris Leonidovich,’ Olga pleaded. ‘It’s just impossible for me. I am afraid still …’

‘No, no! You’ll get used to it,’ he commanded. ‘Very well, then, go on saying “you” to me for the time being but let me call you “thou”.’

Flattered and concerned by this new intimacy, Olga returned to work, flustered. At about nine in the evening, she heard the familiar tapping on the pipes in her apartment. She raced downstairs to speak. ‘I didn’t get to the second thing I wanted to tell you,’ he said. ‘And you didn’t ask me what it was. Well, the first thing was that we should say “thou” to each other. The second thing was; I love you. I love you and this is my whole life now. I won’t come to your office tomorrow but to your house instead – I’ll wait for you to come down and we’ll walk round the town.’

That night, Olga wrote out a ‘confession’ to Boris; a letter that filled a whole notebook. In it she detailed her past history, sparing no detail of her two marriages and the difficulties that she had already endured in her life. She told him that she was born in 1912 in a provincial town where her father had been a high school teacher. The family moved to Moscow in 1915. In 1933 she graduated from the Faculty of Literature of Moscow University. Both her previous marriages had ended in tragedy.

Olga’s past was colourful and complex, a fact her detractors in Moscow literary circles leapt upon when gossip of her affair with Boris began to circulate. She told Boris every detail, writing in her confessional notebook about the deaths of both her previous husbands. She could not be accused of hiding anything from him. However, it is odd that even her daughter, Irina, was unsure whether Ivan Emelianov was her mother’s first or second husband. ‘Ivan [Vania] Emelianov is the man I got my name from,’ Irina wrote later. ‘He was my mum’s second husband (or maybe third) and posed as my father. When you look at his face in photographs, it is hard to believe that he was a mere farmer and that his mother, wrapped up in a black scarf, was illiterate. There was something classy about his family, some kind of elegance.’

Ivan Emelianov hanged himself in 1939, when Irina was nine months old, apparently because he suspected Olga was having an affair with his rival and enemy, Alexander Vinogradov. According to Irina, her father was ‘a man from a different era, a good family man, a principled husband and difficult to live with. Their marriage was destined to fail.’ In family photographs her father was a ‘tall man with a sombre face and doleful expression but handsome’.

Although Olga mourned Ivan’s death, Irina noted wryly that her sorrow did not last very long. The forty-day mourning period was barely over when a man in a long leather coat (Vinogradov) was seen standing outside the family home, waiting for her mother. Olga and Vinogradov soon married and had a son, Dimitri (known by the family as Mitia). From a large impoverished family ‘worn down by diseases and alcohol’, Vinogradov was ‘brilliant and strong-willed’. He embraced the new Soviet order, working his way up from being in charge of a poor farmer committee at the age of fourteen. He was quickly promoted to run a collective farm, then moved to Moscow, where he gained a managerial position on the editorial board of a magazine called Samolet. It was there that he had first met Olga, who was working as a secretary.

Vinogradov died in 1942 from lung congestion, leaving Olga a widow for the second time. ‘I had already gone through more than enough horrors,’ she later wrote: ‘The suicide of Ira’s father, my first husband Ivan Vasilyevich Yemelyanov; the death of my second husband, Alexander Petrovich Vinogradov – who had died in my arms in hospital. I had had many passing affairs and disappointments in love.’ Olga concluded in her confessional letter to Boris: ‘If you have been a cause of tears [she was still addressing him as ‘you’ as opposed to ‘thou’] so have I! Judge for yourself the things I have to say in reply to “I love you” – which gives me more joy than anything that has ever happened to me.’

The next morning, when she went down from her apartment to work, Boris was already waiting for her by an empty fountain in their courtyard. She gave him the notebook and eager to read it, he embraced her and left soon afterwards. Olga was hardly able to concentrate at work all day, jittery inside as to how he would react to the highly personal details she had chronicled. If on some level, her confessional was a bid to push him away, she failed miserably, underestimating Boris’s admiration for the plight of wronged womanhood.

That night, Olga was summoned by a knock on the pipe at half past eleven. Her grumpy, long-suffering neighbour, clad in her nightgown, led Olga into her apartment to speak to her amour. Olga felt terribly embarrassed for her neighbour but did not have the heart to tell Boris not to ring at such an unsociable hour as his voice sounded so joyous.

‘Olia, I love you,’ Boris declared. ‘I try to spend my evenings alone now, and I think of you sitting in your office – where for some reason I always imagine there must be mice – and of the way you worry about your children. You have come tripping right into my life. This notebook will always be with me, but you must keep it for me – I dare not leave it at home in case it is found there.’

During that call, Olga knew that they had crossed a boundary line and now nothing could stop them from being together, no matter how challenging the obstacles. There was little doubt that they had found each other. Boris needed the miracle of love at first sight as much as Olga did. They were both lonely, full of yearning for romance and in difficult, emotionally unsatisfying domestic situations.

On 3 April 1947 Boris was invited to Olga’s apartment, on the top floor of a six-storey building, to meet her family. Irina, who was nine years old, was wearing a smart pink dress with matching ribbons. Used to the ‘misery that comes with war and post war time’ she felt uncomfortable trussed up. She also felt under considerable pressure, as the night before Olga had read and reread Pasternak’s poems to her, which she wanted her daughter to learn and recite to their esteemed visitor. Irina, who did not understand a word she was saying, became flustered: ‘Even words I knew like “garage” and “taxi depot” have an unusual meaning in those verses and it felt like I had never seen them before. I became so disarmed; I was incapable of pronouncing them. Mum was distraught, what could she do?’

Olga had placed a bottle of cognac and a box of chocolates on the table before Boris. According to Irina, her mother had decided to go for the ‘minimalistic option’, concerned that the writer would judge their eating habits, which were ‘not really worthy of a man like him’. Boris sat at the oversized wax cloth that covered the table and, as always, kept his long black coat on and did not remove his well-worn astrakhan black cap. As conversation was a little awkward to begin with, Olga told him that Irina wrote verse too. Irina blushed, embarrassed, especially when Boris promised that he would look at her poetry at a later date.

Irina, however, was smitten. There was ‘something remarkable about him. His booming voice interrupting with its famous “yes, yes, yes”. He had a magnetic, magic quality.’

Although Irina felt nervous and intimidated in front of her mother’s ‘idol’, their first meeting was to have an equally indelible impact on the burgeoning novelist: ‘The day came when my children saw BL for the first time,’ Olga later wrote. ‘I remember how Irina, stretching out her thin little arm to hold on to the table, recited one of his poems to him. It was a difficult one, and Lord knows how and when she had managed to learn it.’ Afterwards, Boris wiped away a tear and kissed her: ‘What extraordinary eyes she has!’ he exclaimed. ‘Look at me, Ira. You could go straight into my novel!’

She did go straight into the pages of his book. In Doctor Zhivago Pasternak describes Lara’s daughter Katenka: ‘A little girl of about eight came in, her hair done up in finely braided plaits. Her narrow eyes had a sly, mischievous look and went up at the corners when she laughed. She knew her mother had a visitor, she had heard his voice outside the door, but she thought it necessary to put on an air of surprise. She curtsied and looked at Yury with the fearless, unblinking stare of a lonely child who had started to think early in life.’

From the moment that Boris entered Olga’s family’s life, he felt torn – torn between his love and loyalty to them, and to his wife Zinaida and their son Leonid. Just as years before he had previously been torn between Zinaida and his first wife, Evgenia, and their son, Evgeny. Almost a decade earlier, on 1 October 1937, Pasternak had written to his parents about the unsettled air of regret in his home: ‘A divided family, lacerated by suffering and constantly looking over our shoulders at that other family, the first ones.’

Although Boris was tortured by guilt for the suffering he caused Zinaida (and to Evgenia before her), part of him seemed to enjoy – or at least need – the drama of anguish. Renouncing Olga was never something he seriously considered. Early into his affair with Olga he told his artist friend Liusia Popova that he had fallen in love. When asked about Zinaida, he replied: ‘What is life if not love? She [Olga] is so enchanting, such a radiant, golden person. And now this golden sun has come into my life, it is so wonderful. So wonderful. I never thought I would still know such joy.’

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/anna-pasternak/lara-the-untold-love-story-that-inspired-doctor-zhivago/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Anna Pasternak

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The heartbreaking story of the passionate love affair between Boris Pasternak and Olga Ivinskaya – the tragic true story that inspired Doctor Zhivago.‘Doctor Zhivago’ has sold in its millions yet the true love story that inspired it has never been fully explored. Pasternak would often say ‘Lara exists, go and meet her’, directing his visitors to the love of his life and literary muse, Olga Ivinskaya. They met in 1946 at the literary journal where she worked. Their relationship would last for the remainder of their lives.Olga paid an enormous price for loving ‘her Boria’. She became a pawn in a highly political game and was imprisoned twice in Siberian labour camps because of her association with him and his controversial work. Her story is one of unimaginable courage, loyalty, suffering, tragedy, drama and loss.Drawing on both archival and family sources, Anna Pasternak’s book reveals for the first time the critical role played by Olga in Boris’s life and argues that without Olga it is likely that Doctor Zhivago would never have been completed or published.Anna Pasternak is a writer and member of the famous Pasternak family. She is the great-granddaughter of Leonid Pasternak, the impressionist painter and Nobel Prize winning novelist Boris Pasternak was her great-uncle. She is the author of three previous books.