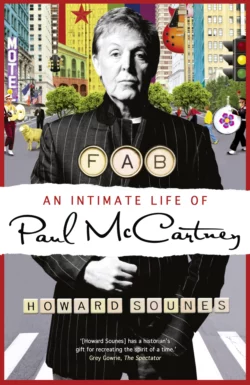

Fab: An Intimate Life of Paul McCartney

Howard Sounes

The living embodiment of The Beatles, a musical juggernaut without parallel, Paul McCartney is undoubtedly the senior figure in pop music today. In this authoritative biography, journalist and acclaimed author Howard Sounes leaves no stone unturned in building the most accurate and extensive profile yet of music's greatest living legend.He is one of the biggest stars that has ever existed, the only key member left from the unquestioned 'biggest band of all time'. But despite the almost unprecedented press coverage he has received throughout his lifetime, the private personality of Paul McCartney remains a source of intrigue and relative mystery to the public.Spanning the entirety of McCartney's life from early childhood right up to the present day, FAB delves deep into the life of this remarkable and often surprising man, revealing the often dark reality behind his consistently positive, relaxed public image. For the first time, Sounes will examine in detail the lifestyle of one of the richest men on the planet, the truth behind his much publicized divorce from Heather Mills, as well as his tempestuous relationship with the other Beatles, with startling revelations.Drawing on countless interviews, legal records and public documents, Howard Sounes' meticulous approach and brilliant powers of research reveal the real Paul McCartney, like you've never known him before.

FAB:

AN INTIMATE LIFE OF

Paul McCartney

HOWARD SOUNES

Playlist (#ulink_1c22c5b3-68dc-5c4c-9726-834fc4992427)

To hear a playlist of music by Paul McCartney, chosen by the author and discussed in Fab, please visit www.fabplaylist.co.uk

Contents

Cover (#u71f47329-566b-5bbc-b54f-7984c53586be)

Title Page (#ubf13333d-4736-553c-b711-1eebd6fa1e84)

Playlist

PART ONE - WITH THE BEATLES

CHAPTER 1 - A LIVERPOOL FAMILY

CHAPTER 2 - JOHN

CHAPTER 3 - HAMBURG

CHAPTER 4 - LONDON

CHAPTER 5 - THE MANIA

CHAPTER 6 - AMERICA

CHAPTER 7 - YESTERDAY

CHAPTER 8 - FIRST FINALE

CHAPTER 9 - LINDA

CHAPTER 10 - HELLO, GOODBYE

CHAPTER 11 - PAUL TAKES CHARGE

CHAPTER 12 - WEIRD VIBES

CHAPTER 13 - WEDDING BELLS

CHAPTER 14 - CREATIVE DIFFERENCES

PART TWO - AFTER THE BEATLES

CHAPTER 15 - ‘HE’S NOT A BEATLE ANY MORE!’

CHAPTER 16 - THE NEW BAND

CHAPTER 17 - IN THE HEART OF THE COUNTRY

CHAPTER 18 - THE GOOD LIFE

CHAPTER 19 - GO TO JAIL

CHAPTER 20 - INTO THE EIGHTIES

CHAPTER 21 - TRIVIAL PURSUITS

CHAPTER 22 - THE NEXT BEST THING

CHAPTER 23 - MUSIC IS MUSIC

CHAPTER 24 - A THREE-QUARTERS REUNION

CHAPTER 25 - PASSING THROUGH THE DREAM OF LOVE

CHAPTER 26 - RUN DEVIL RUN

CHAPTER 27 - THAT DIFFICULT SECOND MARRIAGE

CHAPTER 28 - WHEN PAUL WAS SIXTY-FOUR

CHAPTER 29 - THE EVER-PRESENT PAST

SOURCE NOTES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

About the Author

Praise

Also by Howard Sounes

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher (#u705993c8-aa2a-53a5-9586-abac64b3471d)

PART ONE WITH THE BEATLES (#ulink_5d042d7b-09a7-5f33-80de-16bb799d6cde)

CHAPTER 1 A LIVERPOOL FAMILY (#ulink_c51a331c-1670-5f7c-a4f4-36dc194f02d6)

AT THE START OF THE ROAD

‘They may not look much,’ Paul would say in adult life of his Liverpool family, having been virtually everywhere and seen virtually everything there is to see in this world. ‘They’re just very ordinary people, but by God they’ve got something – common sense, in the truest sense of the word. I’ve met lots of people, [but] I have never met anyone as interesting, or as fascinating, or as wise, as my Liverpool family.’

Liverpool is not only the city in which Paul McCartney was born; it is the place in which he is rooted, the wellspring of the Beatles’ music and everything he has done since that fabulous group disbanded. Originally a small inlet or ‘pool’ on the River Mersey, near its confluence with the Irish Sea, 210 miles north of London, Liverpool was founded in 1207, coming to significance in the seventeenth century as a slave trade port, because Liverpool faces the Americas. After the abolition of slavery, the city continued to thrive due to other, diverse forms of trade, with magnificent new docks constructed along its riverine waterfront, and ocean liners steaming daily to and from the United States. As money poured into Liverpool, its citizens erected a mini-Manhattan by the docks, featuring the Royal Liver Building, an exuberant skyscraper topped by outlandish copper birds that have become emblematic of this confident, slightly eccentric city.

For the best part of three hundred years men and women flocked to Liverpool for work, mostly on and around the docks. Liverpool is and has always been a predominantly white, working-class city, its people made up of and descended in large part from the working poor of surrounding Lancashire, plus Irish, Scots and Welsh incomers. Their regional accents combined in an urban melting pot to create Scouse, the distinctive Liverpool voice, with its singular, rather harsh pronunciation and its own witty argot, Scousers typically living hugger-mugger in the city’s narrow terrace streets built from the local rosy-red sandstone and brick.

Red is the colour of Liverpool – the red of its buildings, its left-wing politics and Liverpool Football Club. As the city has a colour, its citizens have a distinct character: they are friendly, jokey and inquisitive, hugely proud of their city and thin-skinned when it is criticised, as it has been throughout Paul’s life. For Liverpool’s boom years were over before Paul was born, the population reaching a peak of 900,000 in 1931, since when Liverpool has faded, its people, Paul included, leaving to find work elsewhere as their ancestors once came to Merseyside seeking employment, the abandoned city becoming tatty and tired, with mounting social problems.

Paul’s maternal grandfather, Owen Mohin, was a farmer’s son from County Monaghan, south of what is now the border with Northern Ireland, and it’s likely there was Irish blood on the paternal side of the family, too. McCartney is a Scottish name, but four centuries ago many Scots McCartneys settled in Ireland, returning to mainland Britain during the Potato Famine of the mid-1800s. Paul’s paternal ancestors were probably among those who recrossed the Irish Sea at this time in search of food and work. Great-grandfather James McCartney was also most likely born in Ireland, but came to Liverpool to work as a housepainter, making his home with wife Elizabeth in Everton, a working-class suburb of the city. Their son, Joseph, born in 1866, Paul’s paternal grandfather, worked in the tobacco trade, tobacco being one of the city’s major imports. He married a local girl named Florence Clegg and had ten children, the fifth of whom was Paul’s dad.

Aside from Paul’s parents, his extended Liverpool family, his relatives – what Paul would call ‘the relies’ – have played a significant and ongoing part in his life, so it is worth becoming acquainted with his aunts and uncles. John McCartney was Joe and Flo McCartney’s firstborn, known as Jack. Paul’s Uncle Jack was a big strong man, gassed in the First World War, with the result that after he came home – to work as a rent collector for Liverpool Corporation – he spoke in a small, husky voice. You had to lean in close to hear what Jack was saying, and often he was telling a joke. The McCartneys were wits and raconteurs, deriving endless fun from gags, word games and general silliness, all of which became apparent, for better or worse, when Paul turned to song writing. McCartney family whimsy is in ‘Maxwell’s Silver Hammer’ and ‘Rocky Raccoon’, also ‘Rupert and the Frog Song’.

There was a son after Jack who died in infancy; then came Edith (Edie) who married ship steward Will Stapleton, the black sheep of the family; another daughter died in infancy; after which Paul’s father, James, was born on 7 July 1902, known to all as Jim. He was followed by three girls: Florence (Flo), Annie and Jane, the latter known as Gin or Ginny, after her middle name Virginia. Ginny, who married carpenter Harry Harris, was Paul’s favourite relative outside his immediate family and close to her younger sister, Mildred (Milly), after whom came the youngest, Joe, known as Our Bloody Joe, a plumber who married Joan, who outlived them all. Looking back, Joan recalls a family that was ‘very clannish’, amiable, witty people who liked company. In appearance the men were slim, smartly dressed and moderately handsome. Paul’s dad possessed delicate eyebrows which arched quizzically over kindly eyes, giving him the enquiring, innocent expression Paul has inherited. The women were of a more robust build, and in many ways the dominant personalities. None more so than the redoubtable Auntie Gin, whom Paul name-checks in his 1976 song ‘Let ’em In’. ‘Ginny was up for anything. She was a wonderful mad character,’ says Mike Robbins, who married into the family, becoming Paul’s Uncle Mike (though he was actually a cousin). ‘It’s a helluva family. Full of fun.’

Music played a large part in family life. Granddad Joe played in brass bands and encouraged his children to take up music. Birthdays, Christmas and New Year were all excuses for family parties, which involved everybody having a drink and a singsong around the piano, purchased from North End Music Stores (NEMS), owned by the Epstein family, and it was Jim McCartney’s fingers on the keys. He taught himself piano by ear (presumably his left, being deaf in his right). He also played trumpet, ‘until his teeth gave out’, as Paul always says. Jim became semi-professional during the First World War, forming a dance band, the Masked Melody Makers, later Jim Mac’s Band, in which his older brother Jack played trombone. Other relatives joined the merriment, giving enthusiastic recitals of ‘You’ve Gone’ and ‘Stairway to Paradise’ at Merseyside dance halls. Jim made up tunes as well, though he was too modest to call himself a songwriter. There were other links to show business. Younger brother Joe Mac sang in a barber-shop choir and Jack had a friend at the Pavilion Theatre who would let the brothers backstage to watch artists such as Max Wall and Tommy Trinder perform. As a young man Jim worked in the theatre briefly, selling programmes and operating lights, while a little later on Ann McCartney’s daughter Bett took as her husband the aforementioned Mike Robbins, a small-time variety artiste whose every other sentence was a gag (‘Variety was dying, and my act was helping to kill it’). There was a whiff of greasepaint about this family.

Jim’s day job was humdrum and poorly paid. He was a salesman with the cotton merchants A. Hannay & Co., working out of an impressive mercantile building on Old Hall Street. One of Jim’s colleagues was a clerk named Albert Kendall, who married Jim’s sister Milly, becoming Paul’s Uncle Albert (part of the inspiration for another of Paul’s Seventies’ hits, ‘Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey’). It was perhaps because Jim was having such a grand old time with his band and his extended family that he waited until he was almost forty before he married, by which time Britain was again at war. It was Jim’s luck to have been too young to serve in the First World War, and now he was fortunate to be too old for the Second. He lost his job with Hannay’s, though, working instead in an aircraft factory during the day and fire-watching at night. Liverpool’s docks were a prime German target during the early part of the war, with incendiary shells falling almost nightly. It was during this desperate time, with the Luftwaffe overhead and Adolf Hitler’s armies apparently poised to invade from France, that Jim McCartney met his bride-to-be, Paul’s mother Mary.

Mary Mohin was the daughter of Irishman Owen Mohin, who’d left the old country to work in Glasgow, then moving south to Liverpool, where he married Mary Danher and had four children: a daughter named Agnes who died in childhood, boys Wilfred and Bill, the latter known as Bombhead, and Paul’s mother, Mary, born in the Liverpool suburb of Fazakerley on 29 September 1909. Mary’s mother died when she was ten. Dad went back to Ireland to take a new bride, Rose, whom he brought to Liverpool, having two more children before dying himself in 1933, having drunk and gambled away most of his money. Mary and Rose didn’t get on and Mary left home when still young to train as a nurse, lodging with Harry and Ginny Harris in West Derby. One day Ginny took Mary to meet her widowed mother Florence at her Corporation-owned (‘corpy’) home in Scargreen Avenue, Norris Green, whereby Mary met Gin’s bachelor brother Jim. When the air-raid warning sounded, Jim and Mary were obliged to get to know each other better in the shelter. They married soon after.

Significantly, Paul McCartney is the product of a mixed marriage, in that his father was Protestant and his mother Roman Catholic, at a time when working-class Liverpool was divided along sectarian lines. There were regular clashes between Protestants and Catholics, especially on 12 July, when Orangemen marched in celebration of William III’s 1690 victory over the Irish. St Patrick’s Day could also degenerate into street violence, as fellow Merseysider Ringo Starr recalls: ‘On 17th March, St Patrick’s Day, all the Protestants beat up the Catholics because they were marching, and on 12th July, Orangeman’s [sic] Day, all the Catholics beat up the Protestants. That’s how it was, Liverpool being the capital of Ireland, as everybody always says.’ Mild-mannered Jim McCartney was agnostic and he seemingly gave way to his wife when they married on 15 April 1941, for they were joined together at St Swithin’s Roman Catholic Chapel. Jim was 38, his bride 31. There was an air raid that night on the docks, the siren sounding at 10:27 p.m., sending the newlyweds back down the shelter. Bombs fell on Garston, killing eight people before the all-clear. The Blitz on Liverpool intensified during the next few months, then stopped in January 1942. Britain had survived its darkest hour, and Mary McCartney was pregnant with one of its greatest sons.

JAMES PAUL McCARTNEY

Although the Luftwaffe had ceased its bombing raids on Liverpool by the time he was born, on Thursday 18 June 1942, James Paul McCartney, best known by his middle name, was very much a war baby. As Paul began to mewl and bawl, the newspapers carried daily reports of the world war: the British army was virtually surrounded by German troops at Tobruk in North Africa; the US Navy had just won the Battle of Midway; the Germans were pushing deep into Russian territory on the Eastern Front; while at home Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s government was considering adding coal to the long list of items only available on ration. Although the Blitz had passed for Liverpool, the war had three years to run, with much suffering and deprivation for the nation.

As his parents were married in a Catholic church, Paul was baptised into the Catholic faith at St Philomena’s Church, on 12 July 1942, the day the Orange Order marches. Though this may have been coincidental, one wonders whether Mary McCartney and her priest, Father Kelly, chose this day to baptise the son of a Protestant by way of claiming a soul for Rome. In any event, like his father, Paul would grow up to have a vague, non-denominational faith, attending church rarely. Two years later a second son was born, Michael, Paul’s only sibling. The boys were typical brothers, close but also rubbing each other up the wrong way at times.

Paul was three and Mike one when the war ended. Dad resumed his job at the cotton exchange, though, unusually, it was Mum’s work that was more important to the family. The 1945 General Election brought in the reforming Labour administration of Clement Attlee, whose government implemented the National Health Service (NHS). Mary McCartney was the NHS in action, a relatively well-paid, state-trained midwife who worked from home delivering babies for her neighbours. The family moved frequently around Merseyside, living at various times in Anfield, Everton, West Derby and over the water on the Wirral (a peninsula between Liverpool and North Wales). Sometimes they rented rooms, other times they lodged with relatives. In 1946, Mary was asked to take up duties on a new housing estate at Speke, south of the city, and so the McCartneys came to 72 Western Avenue, what four-year-old Paul came to think of as his first proper home.

Liverpool had long had a housing problem, a significant proportion of the population living in slums into the 1950s. In addition to this historic problem, thousands had been made homeless by bombing. In the aftermath of the war many Liverpool families were accommodated temporarily in pre-fabricated cottages on the outskirts of the city while Liverpool Corporation built large new estates of corporation-owned properties which were rented to local people. Much of this construction was undertaken at Speke, a flat, semi-rural area between Liverpool and its small, outlying airport, with huge industrial estates built simultaneously to create what was essentially a new town. The McCartneys were given a new, three-bedroom corpy house on a boulevard that leads today to Liverpool John Lennon Airport. In the late 1940s this was a model estate of new ‘homes fit for heroes’. Because the local primary school was oversubscribed, Paul, along with many children, was bussed to Joseph Williams Primary in nearby Childwall. Former pupils dimly recall a friendly, fat-faced lad with a lively sense of humour. A class photo shows Paul neatly dressed, apparently happy and confident, and indeed these were halcyon days for young McCartney, whose new suburban home gave him access to woods and meadows where he went exploring with the Observer Book of Birds and a supply of jam butties, happy adventures recalled in a Beatles’ song, ‘Mother Nature’s Son’.

In the evening, Mum cooked while Dad smoked his pipe, read the newspaper or did the garden, dispensing wisdom and jokes to the boys as he went. There were games with brother Mike, and the fun of BBC radio dramas and comedy shows. Wanting to spend more time with her sons, Mary resigned from her job as a midwife in 1950, consequently losing tenure of 72 Western Avenue. The family moved one mile to 12 Ardwick Road, a slightly less salubrious address in a part of the estate not yet finished. On the plus side the new house was opposite a playing field with swings. Resourceful Mary got a job as a health visitor, using the box room as her study. One of Jim’s little home improvements was to fix their house number to a wooden plaque next to the front doorbell. When Paul came by decades later with his own son, James, he was surprised and pleased to see the number still in place. The current tenant welcomed the McCartneys back, but complained to Paul about being pestered by Beatles fans who visited her house regularly as part of what has become a Beatles pilgrimage to Liverpool, taking pictures through the front window and clippings from her privet hedge. Paul jokingly asked, with a wink to James, whether she didn’t feel privileged.

‘No,’ the owner told him firmly. ‘I’ve had enough!’

Her ordeal is evidence of the fact that, alongside that of Elvis Presley, the Beatles are now the object of the most obsessive cult in popular music.

THE BLACK SHEEP

As we have seen, the McCartneys were a large, close-knit family who revelled in their own company, getting together regularly for parties. Jim would typically greet his nearest and dearest with a firm handshake, a whimsical smile, and one of his gnomic expressions. ‘Put it there,’ he’d say, squeezing your hand, ‘if it weighs a ton.’ What this meant was not entirely clear, but it conveyed the sense that Jim was a stalwart fellow. And if the person being greeted was small, they would often take their hand away to find Jim had slipped a coin into their palm. Jim was generous. He was also honest, as the McCartneys generally were. They were not scallies (rough or crooked Scousers), until it came to Uncle Will.

Considering how long Paul McCartney has been famous, and how closely his life has been studied, it is surprising that the scandalous story of the black sheep of the McCartney family has remained untold until now. Here it is. In 1924 Paul’s aunt Edie, Dad’s sister, married a ship steward named Alexander William Stapleton, known to everybody as Will. Edie and Will took over Florence McCartney’s corporation house in Scargreen Avenue after she died, and Paul saw his Uncle Will regularly at family gatherings. Everybody knew Will was ‘a bent little devil’, in the words of one relative. Will was notorious for pinching bottles from family parties, and for larger acts of larceny. He routinely stole from the ships he worked on. On one memorable occasion Will sent word to Edie that she and Ginny were to meet him at the Liverpool docks when his ship came in. Gin wondered why her brother-in-law required her presence as well as that of his wife. She found out when Will greeted her over the fence. As Ginny told the tale, Will kissed her unexpectedly on the lips, slipping a smuggled diamond ring into her mouth with his tongue as he did so. That wasn’t all. When he cleared customs, Will gave his wife a laundry bag concealing new silk underwear for her, while he presented Ginny with a sock containing – so the story goes – a chloroformed parrot.

Will boasted that one day he would pull off a scam that would set him up for life. This became a McCartney family joke. Jack McCartney was wont to stop ‘relies’ he met in town and whisper: ‘I see Will Stapleton’s back from his voyage.’

‘Is he?’ the relative would ask, leaning forward to hear Jack’s wheezy voice.

‘Yes, I’ve just seen the Mauretania* (#ulink_63036d7d-dfc9-52a5-baa5-082b1f81e27e) halfway up Dale Street.’ Joking aside, Will did pull off a colossal caper, one sensational enough to make the front page of the Liverpool Evening News, even The Times of London, to the family’s enduring embarrassment.

Will was working as a baggage steward on the SS Apapa, working a regular voyage between Liverpool and West Africa. The outward-bound cargo in September 1949 included 70 crates of newly printed bank notes, destined for the British Bank of West Africa. The crates of money, worth many millions in today’s terms, were sealed and locked in the strongroom of the ship. Will and two crewmates, pantry man Thomas Davenport and the ship’s baker, Joseph Edwards, hatched a plan to steal some of this money. It was seemingly Davenport’s idea, recruiting Stapleton to help file down the hinges on the strongroom door, tap out the pins and lift the door clear. They then stole the contents of one crate, containing 10,000 West African bank notes, worth exactly £10,000 sterling in 1949, a sum equal to about £250,000 in today’s money (or $382,500 US

(#ulink_6075c1b1-311f-59b7-a478-3583ab69e69d)). The thieves replaced the stolen money with pantry paper, provided by Edwards, resealed the crate and rehung the door. When the cargo was unloaded at Takoradi on the Gold Coast, nothing seemed amiss and the Apapa sailed on its way. It was only when the crates were weighed at the bank that one crate was found light and the alarm was raised.

The Apapa had reached Lagos, where the thieves spent some of the stolen money before rejoining the ship and sailing back to England. British police boarded the Apapa as it returned to Liverpool, quickly arresting Davenport and Edwards, who confessed, implicating Stapleton. ‘You seem to know all about it. There’s no use in my denying it further,’ Paul’s Uncle Will was reported to have told detectives when he was arrested. The story appeared on page one of the Liverpool Evening Express, meaning the whole family was appraised of the disgrace Will had brought upon them.

‘Jesus, it’s the bloody thing he always said he was going to have a go at!’ exclaimed Aunt Ginny.

Stapleton and his crewmates pleaded guilty in court to larceny on the high seas. Stapleton indicated that his cut was only £500. He said he became nervous when he saw the ship’s captain inspecting the strong room on their return voyage. ‘As a result I immediately got rid of what was left of my £500 by throwing it through the porthole into the sea. I told Davenport and he called me a fool and said he would take a chance with the rest.’ The judge sentenced Uncle Will to three years in prison, the same with Davenport. Edwards got 18 months.

The police only recovered a small amount of the stolen money. Maybe Davenport and Stapleton had indeed chucked the rest in the Atlantic, as they claimed, but within the McCartney family there was speculation that Will hung onto some of that missing currency. It was said that the police watched him carefully after he got out of jail, and when detectives finally tired of their surveillance Will went on a spending spree, acquiring, among other luxuries, the first television in Scargreen Avenue.

GROWING UP

Paul’s parents got their first TV in 1953, as many British families did, in order to watch the Coronation of the new Queen, 27-year-old Elizabeth II, someone Paul would see a lot of in the years ahead. Master McCartney distinguished himself by being one of 60 Liverpool schoolchildren to win a Coronation essay competition. ‘Coronation Day’ by Paul McCartney (age: 10 years 10 months) paid patriotic tribute to a ‘lovely young Queen’ who, as fate would have it, would one day knight him as Sir Paul McCartney.

Winning the prize showed Paul to be an intelligent boy, which was borne out when at the end of his time at Joseph Williams Primary he passed the Eleven Plus – an exam taken by British schoolchildren aged 11–12 – which was the first significant fork in the road of their education at the time. Those who failed the exam were sent to secondary modern schools, which tended to produce boys and girls who would become manual or semi-skilled workers; while the minority who passed the Eleven Plus typically went to grammar school, setting them on the road to a university education and professional life. What’s more, Paul did well enough in the exam to be selected for Liverpool’s premier grammar school, indeed one of the best state schools in England.

The Liverpool Institute, or Inny, looked down on Liverpool from an elevated position on Mount Street, next to the colossal new Anglican cathedral. Work had started on what is perhaps Liverpool’s greatest building, designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, in 1904. The edifice took until 1978 to finish. Although a work in progress, the cathedral was in use in the early 1950s. Paul had recently tried out for the cathedral choir. (He failed to get in, and sang instead at St Barnabas’ on Penny Lane.) Standing in the shadow of this splendid cathedral, the Inny had a modest grandeur all its own. It was a handsome, late-Georgian building, the entrance flanked by elegant stone columns, with an equally fine reputation for giving the brightest boys of the city the best start in life. Many pupils went on to Oxford and Cambridge, the Inny having produced notable writers, scientists, politicians, even one or two show business stars. Before Paul, the most famous of these was the comic actor Arthur Askey, at whose desk Paul sat.

Kitted out in his new black blazer and green and black tie, Paul was impressed and daunted by this new school when he enrolled in September 1953. Going to the Inny drew him daily from the suburbs into the urban heart of Liverpool, a much more dynamic place, while any new boy felt naturally overwhelmed by the teeming life of a school that numbered around 1,000 pupils, overseen by severe-looking masters in black gowns who’d take the cane readily to an unruly lad. The pupils got their own back by awarding their overbearing teachers colourful and often satirical nicknames. J.R. Edwards, the feared headmaster, was known as the Bas, for Bastard. (Paul came to realise he was in fact ‘quite a nice fella’.) Other masters were known as Cliff Edge, Sissy Smith (an effeminate English master, related to John Lennon), Squinty Morgan, Funghi Moy and Weedy Plant. ‘He was weedy and his name was Plant. Poor chap,’ explains Steve Norris, a schoolboy contemporary of Paul’s who became a Tory cabinet minister.

The A-stream was for the brightest boys, who studied classics. A shining example and contemporary of Paul’s was Peter ‘Perfect’ Sissons, later a BBC newsreader. The C-stream was for boys with a science bent. Paul went into the B-stream, which specialised in modern languages. He studied German and Spanish, the latter with ‘Fanny’ Inkley, the school’s only female teacher. Paul had the luck to have an outstanding English teacher, Alan ‘Dusty’ Durband, author of a standard textbook on Shakespeare, who got his pupils interested in Chaucer by introducing them to the sexy passages in the Canterbury Tales. ‘Then we got interested in the other bits, too, so he was a clever bloke.’ Paul’s other favourite classes were art and woodwork, both hobbies in adult life. Before music came into his life strongly, Paul was considered one of the school’s best artists. Curiously, Neddy Evans’s music lessons left him cold. Although Dad urged Paul to learn to read music, so he could play properly, Paul never learned what the dots meant. ‘I basically never learned anything at all [about music at school].’ Yet he loved the Inny, and came to recognise the head start it gave him in life. ‘It gave you a great feeling of the world was out there to be conquered, that the world was a very big place, and somehow you could reach it from here.’

It was at the Inny that Paul acquired the nickname Macca, which has endured. Friends Macca made at school included John Duff Lowe, Ivan ‘Ivy’ Vaughan (born the same day as Paul) and Ian James, who shared his taste in radio shows, including the new and anarchic Goon Show. In the playground Macca was ‘always telling tales or going through programmes that were on the previous night,’ James recalls. ‘He’d always have a crowd around him. He was good at telling tales, [and] he had quite a devilish sense of humour.’ Two more schoolboys were of special significance: a clever, thin-faced lad named Neil ‘Nell’ Aspinall, who was in Paul’s class for art and English and became the Beatles’ road manager; and a skinny kid one year Paul’s junior named George.

Born on 25 February 1943,* (#ulink_3bb79e2e-d694-5491-ba67-844d3109a1b2) George Harrison was the youngest of a family of four, the Harrisons being a working-class family from south Liverpool. Mum and Dad were Louise and Harold ‘Harry’ Harrison, the family living in a corpy house at 25 Upton Green, Speke. Harry drove buses for a living. It was on the bus home from school that Paul and George first met properly, their conversation sparked by a growing mutual interest in music, Paul having recently taken up the trumpet. ‘I discovered that he had a trumpet and he found out that I had a guitar, and we got together,’ George recalled. ‘I was about thirteen. He was probably late thirteen or fourteen. (He was always nine months older than me. Even now, after all these years, he is still nine months older!)’ As this remark implies, George always felt that Paul looked down on him and, although he possessed a quick wit, and was bright enough to get into the Inny in the first place, schoolboy contemporaries recall George as being a less impressive lad than Paul. ‘I remember George Harrison as being thick as a plank – and completely uninteresting,’ says Steve Norris bluntly. ‘I don’t think anybody thought George would ever amount to anything. A bit slow, you know [adopting a working-class Scouse accent], a bit You know what I mean, like.’

Paul’s family moved again with Mum’s work, this time to a new corpy house in Allerton, a pleasant suburb closer to town. The address was 20 Forthlin Road, a compact brick-built terrace with small gardens front and back. One entered by a glass-panelled front door which opened onto a parquet hall, stairs straight ahead, lounge to your left, with a coal fire, next to which lived the TV. The McCartneys put their piano against the far wall, covered in blue chinoiserie paper. Swing doors led through to a small dining room, to the right of which was the kitchen, and a passageway back to the hall. Upstairs there were three bedrooms with a bathroom and inside loo, a convenience the family hadn’t previously enjoyed. Paul bagged the back room, which overlooked the Police Training College, brother Mike the smaller box room. The light switches were Bakelite, the floors Lino, the woodwork painted ‘corporation cream’ (magnolia), the doorstep Liverpool red. This new home suited the McCartneys perfectly, and the first few months that the family lived here became idealised in Paul’s mind as a McCartney family idyll: the boy cosy and happy with his kindly, pipe-smoking dad, his funny kid brother, and the loveliest mummy in the world, a woman who worked hard at her job bringing other children into the world, yet always had time for her own, too. Paul came to see Mum almost as a Madonna.

What happened next is the defining event of Paul McCartney’s life, a tragedy made starker because the family had only just moved into their dream home, where they expected to be happy for years to come. Mum fell ill and was diagnosed with breast cancer. It seems Mary knew the prognosis was not good and kept this a secret, at least from her children. One day, in the summer of 1956, Mike found his mother upstairs weeping. When he asked her what was wrong, she replied, ‘Nothing, love.’

At the end of October 1956 Mary was admitted to the Northern Hospital, a gloomy old building on Leeds Street, where she underwent surgery. It was not successful. Paul and Mike were packed off to Everton to stay with Uncle Joe and Auntie Joan. Jim didn’t own a car, so Mike Robbins, who was selling vacuum cleaners between theatrical engagements, gave Jim lifts to the hospital in his van. ‘He was trying to put on a brave front. He knew his wife was dying.’ Finally the boys were taken into the hospital to say goodbye to Mum. Paul noticed blood on her bed sheets. Mary remarked to a relative that she only wished she could see her boys grow up. Paul was 14, Mike 12. Mum died on 31 October 1956, Hallowe’en, aged 47.

Aunt Joan recalls that Paul didn’t express overt grief when told the news. Indeed, he and his brother Mike played rambunctiously that night in her back bedroom. ‘My daughter slept in a camp bed,’ says Joan, ‘and the boys had the double bed in the back bedroom and they were pulling arms off a teddy bear.’ When he did address the fact that his mother had died, Paul did so by asking Dad gauchely how they were going to manage without her wages. Stories like this are sometimes cited as evidence of a lack of empathy on Paul’s part, and it is true that he would react awkwardly in the face of death repeatedly during his life. It is also true that young people often behave in an insensitive way when faced with bereavement. They do not know what death means. Over the years, however, it became plain that Paul saw his world shattered that autumn night in 1956. The premature death of his mother was a trauma he never forgot, nor wholly got over.

* (#ulink_e1b1dcd2-d12c-5dc4-8992-1a3acab93176) One of the largest ships in the world.

† (#ulink_fca03bc3-566a-5017-aeea-8ab4c84c54cc)Unless indicated, sterling/dollar exchange values are as of the time of writing.

* (#ulink_7866ce4f-d10d-5a75-bf7f-dff0b0d4c8ae) It is sometimes said that Harrison was born on 24 February 1943, but his birth and his death certificate clearly state his birthday as the 25th.

CHAPTER 2 JOHN (#ulink_3e823d67-c728-55af-aa91-3bcfac1dfdc6)

HAIL! HAIL! ROCK ’N’ ROLL

A dark period of mourning and adjustment followed the death of Mary McCartney, as widower Jim came to terms with the untimely loss of his wife and tried to instigate a domestic regime at Forthlin Road whereby he could be both father and mother to his boys. This was not easy. Indeed, Paul recalls hearing his father crying at night. It was thanks to the ‘relies’ rallying round, especially Aunts Ginny, Milly and Joan, that Jim was able to carry on at Forthlin Road, the women taking turns to help clean and cook for this bereaved, all-male household.

Crucially, as far as the history of pop is concerned, Paul reacted to the death of his mother by taking comfort in music. He returned the trumpet his father had given him for his recent birthday to Rushworth and Dreaper, a Liverpool music store, and exchanged it for an acoustic Zenith guitar, wanting to play an instrument that would also allow him to sing, and not liking the idea of developing a horn player’s callous on his lips. Learning guitar chords proved challenging because Paul was left-handed and he tried at first to play as a right-hander. It was only when he saw a picture of Slim Whitman playing guitar the other way around (Whitman having taught himself to play left-handed after losing part of a finger on his left hand) that Paul restrung his instrument accordingly and began to make progress. Schoolmate Ian James also played guitar, with greater proficiency, and gave Paul valuable lessons on his own Rex acoustic.* (#ulink_94e64c81-d888-598b-b944-a935b2f92974) As to what the boys played, there was suddenly a whole new genre of music opening up.

Until 1955, the music Paul had heard and enjoyed consisted largely of the jazz-age ballads and dance tunes Mum and Dad liked: primarily the song books of the Gershwins, Cole Porter and Rodgers and Hart; while trips to the movies had given Paul an appreciation of Fred Astaire, a fine singer as well as a great dancer who became a lifelong hero. Now bolder, more elemental rhythms filled his ears. The first real musical excitement for young people in post-war Britain was skiffle, incorporating elements of folk, jazz and blues. A large part of the genre’s appeal was that you didn’t need professional instruments to play it. Ordinary household objects could be used: a wooden tea chest was strung to make a crude bass, a tin washboard became a simple percussion instrument, helping define the rasping, clattering sound of the music. Despite being played on such absurd household items, skiffle could be very exciting, as Scots singer Lonnie Donegan proved in January 1956 when he scored a major hit with a skiffle cover of Leadbelly’s ‘Rock Island Line’ (though the recording features a standard double bass). Almost overnight, thousands of British teenagers formed skiffle bands of their own, with Paul among those Liverpool skifflers who went to see Donegan perform at the local Empire theatre in November, just a few days after Mary McCartney died.

Close on the heels of skiffle came the greater revelation of rock ’n’ roll. The first rumble of this powerful new music reached the UK with the 1955 movie The Blackboard Jungle, which made Bill Haley a fleeting sensation. In the flesh Haley proved a disappointment, a mature, heavy-set fellow, not a natural role model for teens, unlike the handsome young messiah of rock who followed him. Elvis Presley broke in Britain in May 1956 with the release of ‘Heartbreak Hotel’. The singer and the song electrified Paul at the age when boys become closely interested in their appearance. Elvis was his role model, as he was for boys all over the world, and Paul tried to make himself look like his hero. Paul and Ian James went to a Liverpool tailor, who took in their trousers to create rocker-style drainpipe legs; Paul grew his hair, sweeping it back like ‘El’, as they referred to the star; Paul began to neglect his school work, and spent his free time practising Elvis’s songs, as well as other rock ’n’ roll tunes that came fading in and out over the late-night airwaves from Radio Luxembourg. This far-away European station, together with glimpses of music idols on TV and in jukebox movies at the cinema, introduced Paul to the charismatic Americans who sat at Elvis’s feet in the firmament of rock: to the great black poet Chuck Berry, wild man Jerry Lee Lewis, the deceptively straight-looking Buddy Holly, crazy Little Richard and rockabilly pioneer Gene Vincent, whose insistent ‘Be-Bop-A-Lula’ was the first record Paul bought.

Paul started to take his guitar into school. Former head boy Billy Morton, a jazz fan with no time for this new music, recalls being appalled by Paul playing Eddie Cochran’s ‘Twenty-Flight Rock’ in the playground at the Inny. ‘There must have been 150 boys around him, ten deep, whilst he was singing … There he was, star material even then.’ Paul imitated his heroes with preternatural skill. But he was more than just a copyist. Almost immediately, Paul started to write his own songs. ‘He said, “I’ve written a tune,”’ recalls Ian James. ‘It was something I’d never bothered to try, and it seemed quite a feat to me. I thought, He’s written a tune! So we went up to his bedroom and he played this tune, [and] sang it.’ Created from three elementary chords (C, F and G), ‘I Lost My Little Girl’ was of the skiffle variety, with simple words about a girl who had Paul’s head ‘in a whirl’. By dint of this little tune, Paul McCartney became a singer-songwriter. Now he needed a band.

THE QUARRY MEN

The Beatles grew out of a schoolboy band founded and led by John Lennon, an older local boy, studying for his O-levels at Quarry Bank High School, someone Paul was aware of but didn’t know personally. As he says: ‘John was the local Ted’ (meaning Lennon affected the look of the aggressive Teddy Boy youth cult). ‘You saw him rather than met him.’

John Winston Lennon, named after Britain’s wartime leader, was a full year and eight months older than Paul McCartney, born on 9 October 1940. Like Paul, John was Liverpool Irish by ancestry, with a touch of showbiz in the family. His paternal Irish grandfather Jack had sung with a minstrel show. More directly, and unlike Paul, John was the product of a dysfunctional home. Dad was a happy-go-lucky merchant seaman named Freddie Lennon, a man cut from the same cloth as Paul’s Uncle Will. Mum, Julia, was a flighty young woman who dated various men when Fred was at sea, or in prison, as he was during part of the Second World War. All in all, the couple made a poor job of raising their only child,* (#ulink_38d975c6-8b7c-50e7-afb4-9d86daae096a) whom Julia passed, at age five, into the more capable hands of her older, childless sister Mary, known as Mimi, and Mimi’s dairyman husband George Smith.

The relationship between John and his Aunt Mimi is reminiscent of that between David Copperfield and his guardian aunt Betsey Trotwood, an apparently severe woman who proves kindness itself when she gives the unhappy Copperfield sanctuary in her cottage. The likewise starchy but golden-hearted Mimi brought John to live with her and Uncle George in their cosy Liverpool cottage, Mendips, on Menlove Avenue, just over the hill from Paul’s house on Forthlin Road. Much has been made of the social difference between Mendips and Paul’s working-class home, as if John’s was a much grander household. As both houses are now open to the public, courtesy of the National Trust, anyone can see for themselves that Mendips is a standard, three-bedroom semi-detached property, the ‘semi’ being a type of house built by the thousands in the 1920s and ’30s, cosy suburban hutches for those who could afford to take out a small mortgage but couldn’t stretch to a detached property. The essential difference between Mendips and 20 Forthlin Road was that the Smiths owned their home while Jim McCartney rented from the Liverpool Corporation, by dint of which the McCartneys were defined as working-class. It is also fair to say that Menlove Avenue was considered to be a much more desirable place to live.

John’s childhood was upset again when Uncle George died in 1955. Thereafter John and Aunt Mimi shared Mendips with a series of male lodgers whose rent allowed Mimi to make ends meet and who, in one case, shared her bed. One way or another, this was an eccentric start in life, and John grew to be an eccentric character. Like Paul, John was clever, with a quick wit and an intense stare that was later mistaken for a sign of wisdom – he seemed to stare into your soul – whereas in fact he was just short-sighted. He also had a talent for art and a liking for language. Like many solitary children who have suffered periods of loneliness, John was bookish, more so than Paul. John’s voracious reading accounts in part for his lyrics being generally more interesting than Paul’s. The literary influence of Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll is strongly felt in John’s penchant for nonsense, for example, which first found expression in the Daily Howl, a delightful school magazine he wrote and drew for fun. The tone is typified by his famous weather forecast: ‘Tomorrow will be Muggy, followed by Tuggy, Weggy and Thurgy and Friggy’. This is also the humour of the Goon Show, which Paul and John both enjoyed. Above all else, the boys shared an interest in music. John was mad for rock ’n’ roll. Indeed many friends thought John more or less completely mad. In researching the story of Paul’s life it is remarkable that people who knew both Paul and John tend to talk about John most readily, often with laughter, for Lennon said and did endless amusing things that have stuck in their memory, whereas McCartney was always more sensible, even (whisper it) slightly dull by comparison.

Like Paul, John worshipped Elvis Presley. ‘Elvis Presley’s all very well, John,’ Aunt Mimi would lecture her nephew, ‘but I don’t want him for breakfast, dinner and tea.’ (Her other immortal words on this subject were: ‘The guitar’s all very well, John, but you’ll never make a living out of it.’) In emulation of Elvis, John played guitar enthusiastically, but badly, using banjo chords taught him by his mum, who was living round the corner in Blomfield Road, with her current boyfriend, and saw John regularly. Playing banjo chords meant using only four of the guitar’s six strings – which was slightly easier for a beginner. Having grasped the rudiments, John formed a skiffle group with his best mate at Quarry Bank High, Pete Shotton, who was assigned washboard. The band was named the Quarry Men, after their school. Another pupil, Eric Griffiths, played guitar, and Eric recruited a fourth Quarry Bank student, Rod Davis, who’d known John since they were in Sunday school together. Rod recalls: ‘He was known as that Lennon. Mothers would say, “Now stay away from that Lennon.”’ Eric found their drummer, Colin Hanton, who’d already left (a different) school to work as an upholsterer. Finally, Liverpool Institute boy Len Garry was assigned tea chest bass. Together, the lads performed covers of John’s favourite skiffle and rock ’n’ roll songs at parties and youth clubs, sometimes going weeks without playing, for one of John’s signal characteristics was laziness. Indeed, the Quarry Men may well have come to nought had they not agreed to perform at a humble summer fête.

Woolton Village is a short bike ride from John’s house, just east of Liverpool, its annual fête being organised by the vicar of St Peter’s Church, in the graveyard of which reside the remains of one Eleanor Rigby, who as her marker states died in 1939, aged 44. Starting at 2 o’clock on Saturday 6 July 1957, a procession of children, floats and bands made its way through Woolton to the church field, the procession led by the Band of the Cheshire Yeomanry and the outgoing Rose Queen, a local girl who sat in majesty on a flatbed truck. The Quarry Men followed on another, similar truck. Around 3 o’clock the new Rose Queen was crowned on stage in the church field, after which there was a parade of local children in fancy dress, and the Quarry Men played a few songs for the amusement of the kids as the adults mooched around the stalls. Looking at photographs taken that summer afternoon one is reminded that, although John’s band was named the Quarry Men, they were mere boys, gangly youths in plaid shirts, sleeves rolled up, their expressions betraying almost total inexperience as they haltingly sought to entertain an audience comprised mostly of even younger children. Typically, one little girl in a brownie uniform is captured on camera sitting on the edge of the stage looking up at John with the mildest of interest.

John, who had let his hair grow long at the front, then swept it back in a quiff, was standing at a stick microphone, strumming his guitar and singing the Dell-Vikings’ ‘Come Go With Me’. Unsure of the correct words, never having seen them in print, John was improvising lyrics to fit the tune, singing: ‘Come and go with me, down to the penitentiary …’ Paul McCartney thought this clever. Paul had been brought along to the fête by Ivan Vaughan, who knew John and thought his two musical friends should get together. The introduction was made in the church hall where the Quarry Men were due to play a second set. A plaque on the wall now commemorates the historic moment Lennon met McCartney. John recalled: ‘[Ivan] said, “I think you two will get along.” We talked after the show and I saw that he had talent. He was playing guitar backstage, doing “Twenty-Flight Rock”.’ In emulation of Little Richard, Paul also played ‘Long Tall Sally’ and ‘Tutti-Frutti’. Not long after this meeting Pete Shotton stopped Paul in the street and asked if he’d like to join the Quarry Men. He was asking on behalf of John, of course. ‘He was the leader because he was the guy who sang the songs,’ explains Colin Hanton, who was surprised how quickly John made up his mind about this new boy. ‘[Paul] must have impressed him.’

EARLY SHOWS

That summer Rod Davis went to France on holiday and never rejoined the Quarry Men. John Lennon left Quarry Bank High, having failed his O-levels, and was lucky to get a place at Liverpool College of Art, which happened to be next door to Paul’s grammar school on Hope Street. In their summer holidays, Paul and Mike McCartney attended scout camp, where Paul accidentally broke his brother’s arm mucking about with a pulley, after which Jim McCartney took his sons to Butlins in Filey, Yorkshire, where Paul and Mike performed ‘Bye Bye Love’ on stage as a duo.

Girls started to feature in Paul’s life around this time. A pale, unsporty lad with a tendency to podginess, Paul was no teenage Adonis, but he had a pleasant, open face (with straight dark brown hair and hazel eyes) and a confidence that helped make him personable. Meeting Sir Paul today it is his winning confidence that strikes one most strongly. Initially he just buddied around with girls in a group, girls like Marjorie Wilson, whom he’d known since primary school. Likewise he knocked about with Forthlin Road neighbour Ann Ventre, despite getting into a fight with her brother Louis after Paul made a derogatory remark about the Pope (indicating that he didn’t see himself as a Catholic). Paul said one interesting thing to Ann. ‘I’ll be famous one day,’ he told her boldly.

‘Oh yes. Ha! Will you now?’ she replied, astounded by that confidence. Like many people who become very successful, Paul knew at a young age that he would do well. No doubt the fact he had come from such a happy and supportive home helped, being the apple of Mother’s and Father’s eyes. We must also credit him with natural musical talent, some genius even, of which he was himself already aware. If not misplaced, confidence is very attractive and by the time he was 15 Paul had his pick of girlfriends. He lost his virginity to a local girl he was babysitting with, the start of what became a full sexual life.

Being in a band was an excellent way to meet girls; it is one of the primary reasons teenage boys join bands. But early Quarry Men gigs brought the lads more commonly into the company of the men who operated and patronised the city’s social clubs: the Norris Green Conservative Club and the Stanley Abattoir Social for example. Small-time though these engagements were, Paul took every gig seriously. It was he who first acquired a beige stage jacket, John following suit, and it was Paul who got the Quarry Men wearing string ties. ‘I think Paul had more desire to be successful than John,’ comments drummer Colin Hanton. ‘Once Paul joined there was a movement to smarten us up.’ Paul was also quick to advise his band mates on their musicianship. Having taught himself the rudiments of drumming, he gave Colin pointers. ‘He could be a little bit pushy,’ remarks Colin, a sentiment many musicians have echoed.

Of an evening and at weekends Paul would cycle over to John’s house to work on material. It was a pleasant bike ride across Allerton Golf Course, up through the trees and past the greens, emerging onto Menlove Avenue, after which Paul had to cross the busy road and turn left to reach Mendips. ‘John, your little friend’s here,’ Aunt Mimi would announce dubiously, when Master McCartney appeared at her back door. The boys practised upstairs in John’s bedroom, decorated with a pin-up of Brigitte Bardot, whom they both lusted after. Sometimes they played downstairs in the lounge, a large, bright room with a cabinet of Royal Albert china. Uneasy about the boys being in with her best things, Mimi preferred them to practise in the front porch, which suited John and Paul, because the space was acoustically lively. Here, bathed in the sunlight that streamed in through the coloured glass, Lennon and McCartney taught each other to play the songs they heard on the radio, left-handed Paul forming a mirror image of his right-handed, older friend as they sat opposite each other, trying to prevent the necks of their instruments clashing, and singing in harmony. Both had good voices, John’s possessing more character and authority, which Paul made up for by being an excellent mimic, particularly adept at taking off Little Richard. Apart from covering the songs of their heroes, the boys were writing songs, the words and chord changes of which Paul recorded neatly in an exercise book. He was always organised that way.

During term time, Paul and John met daily in town, which was easy now with John studying next door at the art college. Here, Lennon fell in with a group of art students who styled themselves self-consciously the Dissenters, meeting over pints of beer in the pub round the corner, Ye Cracke. Like students the world over, the Dissenters talked earnestly of life, sex and art. Beatnik culture loomed large, the novels of Jack Kerouac and the poetry of Allen Ginsberg and Lawrence Ferlinghetti being very fashionable. The work of these American writers was of great interest to the Dissenters up to the point, significantly, where they decided they didn’t have to be in thrall to American culture. ‘We sat there in the Cracke and thought Liverpool is an exciting place,’ remembers Bill Harry, a founder member of this student group. ‘We can create things and write music about Liverpool, just as the Americans [do about their cities].’ Although the Quarry Men, and later the Beatles, would play rock ’n’ roll in emulation of their American heroes, importantly John and Paul would create authentic English pop songs, with lyrics that referred to English life, sung in unaffected English accents. The same is also true of George Harrison.

When Paul slipped next door to the art college to have lunch with John, his friend Georgie would often tag along. John treated Paul more or less as his equal, despite the age difference, but George Harrison was a further year back, and he seemed very young: a skinny, goofy little kid with a narrow face, snaggly teeth and eyebrows that almost met in the middle. Lennon regarded this boy with condescension. Paul did, too, but he was shrewd enough to see that George was becoming a good guitar player, telling George to show John how well he could play the riff from the song ‘Raunchy’. John was sufficiently impressed to invite Harrison to join the band. George’s relationship with Paul and John was thus established. Ever afterwards the two senior band members would regard George as merely their guitarist. ‘The thing about George is that nobody respected him for the great [talent] he was,’ says Tony Bramwell, a Liverpool friend who went on to work for the Beatles (John Lennon called Bramwell ‘Measles’ because he was everywhere they went). ‘That’s how John and Paul treated George and Ringo: George is [just] the lead guitarist, and Ringo’s [only] the drummer.’

Ringo is not yet in the group. But three of the fab four are together in John’s schoolboy band, Paul and George having squeezed out most of John’s original sidemen. When the resolutely unmusical Pete Shotton announced his decision to quit the group, John made sure of it by breaking Pete’s washboard over his head, though they stayed friends and, like Measles Bramwell, Shotton would work for the boys when they made it. Eric Griffiths was displaced by the arrival of George, while Len Garry dropped out through ill-health. Only the drummer, Colin Hanton, remained, with Paul’s school friend, John Duff Lowe, sitting in as occasional pianist. Of a Sunday, the boys would sometimes rehearse at 20 Forthlin Road while Jim McCartney sat reading his paper. ‘The piano was against the wall, and his father used to sit at the end of the piano facing out into the room, and if he thought we were getting too loud he’d sort of wave his hand. Because he was concerned the neighbours were gonna complain,’ says Duff Lowe, noting how patient and kindly Paul’s dad was. ‘At four o’clock we’d break and he’d go and make [us] a cup of tea.’

Despite Paul’s drive to make the Quarry Men as professional as possible, they were still rank amateurs. So much so that Duff Lowe got up from the piano and left halfway through one show in order to catch his bus home. It is also a wonder that their early experiences of the entertainment industry didn’t put them all off trying to make a living as musicians. On one unforgettable occasion, auditioning for a spot at a working men’s club in Anfield, the Quarry Men watched as the lad before them demonstrated an act that was nothing less than eating glass. The boy cut himself so badly in the process he had to stuff newspaper into his mouth to staunch the blood. Paul’s show business dreams were not quelled. Indeed, he seemed ever more ambitious. At another audition at the Locarno Ballroom, seeing a poster appealing for vocalists, Paul told John, ‘We could do that.’

‘No, we’re a band,’ replied John severely. It was clear to Colin Hanton that Paul would do anything to get ahead in what he had seemingly decided would be his career; or at least as much of a career as music had been for Dad before he settled down and married Mum. It is important to remember that in going into local show business in this way Paul was following in the footsteps of his father, Jim, who had entertained the people of Merseyside between the wars with his Masked Melody Makers. The fact Dad had been down this road already also accounts for Paul’s extra professionalism.

The next step was to make a record. In the spring of 1958, John, Paul, George, John Duff Lowe and Colin Hanton chipped in to record two songs with a local man named Percy Phillips, who had a recording studio in his Liverpool home. For seventeen shillings and sixpence (approximately £13 in today’s money, or $19 US) they could cut a 78 rpm shellac disc with a song on each side. The chosen songs were Buddy Holly’s ‘That’ll Be the Day’ and ‘In Spite of All the Danger’, credited to McCartney and Harrison, but essentially Paul’s song. ‘It was John’s band, but Paul was [already] playing a more controlling part in it,’ observes Duff Lowe. ‘It’s not a John Lennon record [sic] that we are gonna play, it’s a Paul McCartney record.’ This original song is a lugubrious country-style ballad, strongly reminiscent of ‘Trying to Get to You,’ from Elvis’s first LP, which was like the Bible to the boys. John and Paul sang the lyric, George took the guitar solo, the band striking the final chord as Mr Phillips waved his hands frantically to indicate they were almost out of time. ‘When we got the record, the agreement was that we would have it for a week each,’ Paul said. ‘John had it a week and passed it to me. I had it a week and passed it on to George, who had it a week. Then Colin had it a week and passed it to Duff Lowe – who kept it for twenty-three years.’ We shall return to this story later.

A COMMON GRIEF

Despite living with the redoubtable Aunt Mimi, John kept in close touch with his mother, who was more like a big sister to him than a mum. Julia Lennon attended Quarry Men shows, with the band sometimes rehearsing at her house in Blomfield Road, where the boys found her to be a good sport. Paul was fond of Julia, as he was of most motherly women, feeling the want of a mother himself. John also slept the night occasionally at Julia’s. He was at Mum’s on 15 July 1958, while Julia paid a visit to sister Mimi. As Julia left Mendips that summer evening, and crossed busy Menlove Avenue to the bus stop, she was knocked down and killed by a car. The effect on John was devastating. In later years he would remark that he felt like he lost his mother twice: when Julia gave him up when he was 5; and again when he was 17 and she was killed.

In the wake of this calamity, John, always something of a handful, became wilder and more obstreperous, while his friendship with Paul strengthened. The fact that Paul had lost his mother, too, meant both boys had something profound in common, a deep if largely unspoken mutual sadness. It was at this time that they began to write together more seriously, creating significant early songs such as ‘Love Me Do’. Paul would often ‘sag’ off school now to write with John at Forthlin Road when Dad was at work. But Paul was not dependent on John to make music. He wrote alone as well, composing the tune of ‘When I’m Sixty-Four’ on the family piano around this time, ‘thinking it could come in handy in a musical comedy or something’. Unlike John, whose musical horizon didn’t go beyond rock ’n’ roll, Paul had wider tastes and ambitions.

The Quarry Men played hardly any gigs during the remaining months of 1958, and performed only sporadically in the first half of the next year, including an audition for a bingo evening. The boys were to play two sets with a view to securing a regular engagement. The first set went well enough, even though the MC got the curtain stuck, and the management rewarded the lads with free beer. They were all soon drunk, with the result that the second set suffered. ‘It was just a disaster,’ laments Colin Hanton. John started taking the piss out of the audience, as he had a tendency to do, and the Quarry Men weren’t asked back. John was often sarcastic and downright rude to people, picking on their weaknesses. He had a particularly nasty habit of mocking and mimicking the disabled. On the bus home that night, this same devilment got into Paul, who started impersonating the way deaf and dumb people speak. ‘I had two deaf and dumb friends in the factory [where I worked] and that just got me so mad I sort of rounded on him and told him in no uncertain terms to stop that and shut up,’ says Colin, who picked up his drums and left the bus, and thereby the band. Steady drummers were hard to come by – few boys could afford the equipment – and the loss of Colin was a bigger blow than they realised. John, Paul and George would struggle to find a solid replacement right up to the point when they signed with EMI as the Beatles.

WHY A SHOW SHOULD BE SHAPED LIKE A W

After George Harrison left school in the summer, without any qualifications, to become an apprentice electrician, the drummerless Quarry Men started playing the Casbah Coffee Club, a homemade youth club in the cellar of a house in Hayman’s Green, east of Liverpool city centre. This was the home of Mona ‘Mo’ Best, who had turned her basement into a hang-out for her teenage sons Pete and Rory and their mates. The Quarry Men played the Casbah on its opening night, in August 1959, and regular Saturday evenings into the autumn. It was at one of these rave-ups that Paul met his first serious girlfriend, Dorothy ‘Dot’ Rhone, a shy grammar school girl who fancied John initially, but went with Paul when she discovered John was going steady with fellow art student Cynthia Powell.

While playing in the band with Paul and George, John maintained a parallel circle of college friends, headed by art student Stuart Sutcliffe, who becomes a significant character in our story. Born in Edinburgh in 1940, Stu was the son of a Scottish merchant seaman and his teacher wife, who came to Liverpool during the war. John and Paul were both artistic, with a talent for cartooning. Paul was given a prize for his artwork at the Liverpool Institute speech day in December 1959. But Stuart Sutcliffe was really talented, a true artist whose figurative and abstract work made Paul’s drawings look like doodles. Around the time Paul won his school prize, Stuart had a painting selected for the prestigious John Moores Exhibition at the Walker Art Gallery. What’s more, the painting sold for £65 ($99), part of which John and Paul persuaded Stu to invest in a large, German-made Höfner bass guitar, which he bought on hire-purchase. So it was that Paul found himself in a band with John’s older, talented and rather good-looking college friend, someone John grew closer to as he and Stu moved into student digs together in Gambier Terrace, a short walk from the Inny. There was naturally some jealousy on Paul’s part.

Still, John and Paul remained friends, close enough to take a trip down south to visit Paul’s Uncle Mike and Aunt Bett, who, between theatrical engagements, were managing the Fox and Hounds at Caversham in Berkshire. Mike regaled the boys with stories of his adventures in show business and suggested they perform in his taproom. The locals could do with livening up. He billed John and Paul the Nerk Twins – meaning they were nobodies – asking his young cousin what song he planned to open with. ‘It’s got to be a bright opening,’ Mike told Paul. ‘What do you know?’

‘I know, “The World Is Waiting for the Sunrise”,’ replied Paul, citing an old song. ‘Me dad used to play it on the piano.’

Uncle Mike sanctioned the choice, giving the lads some advice. ‘A good act is shaped like a W,’ he lectured, tracing the letter W in the air. It should start strong, at the top of the first stroke of the W, lift the set in the middle, and end high. ‘Too many acts are shaped like an M,’ Mike told the boys: they started quietly at the foot of the M, built to a climax in the middle, then faded at the end. With this advice fixed in their heads, the Nerk Twins did well at the Fox and Hounds, and Paul never forgot Uncle Mike’s alphabetical advice. All his shows from now on would be shaped like Ws.

THE MAN WHO GAVE THE BEATLES AWAY

One of the places Paul and his friends hung out in Liverpool was the Jacaranda coffee bar on Slater Street, managed by an ebullient Welshman named Allan Williams. Born in 1930, Williams was a former encyclopaedia salesmen, who sang tenor in Gilbert & Sullivan operettas, and had recently begun to dabble in concert promotion. His first big show was to feature the American stars Eddie Cochran and Gene Vincent. Cochran died in a car crash before he could fulfil the engagement. The concert went ahead with Vincent and a cobbled-together support bill.

Williams’s partner in this enterprise was the London impresario Larry Parnes, known for his stable of good-looking boy singers, one of whom nicknamed his parsimonious manager ‘Parnes, Shillings and Pence’. Parnes’s modus operandi was to take unknown singers and reinvent them as teen idols with exciting stage names: Reg Smith became Marty Wilde, a fey Liverpudlian named Ron Wycherley was transformed into Billy Fury. When he came to Liverpool for the Gene Vincent show, Parnes discovered that hundreds of local groups had formed in the city in the wake of the skiffle boom. These were mostly four-or five-piece outfits with a lead singer, typically performing American blues, rock and country records they heard in advance of other people around the country because sailors working the trans-Atlantic shipping routes brought the records directly from the USA to Merseyside. While Parnes had plenty of groups in London to back his singers on tours of the southern counties, he wasn’t so well provided with backing groups in the North and Scotland. So he asked Allan Williams to line up a selection of local bands with a view to sending them out on the road with his boy singers. John Lennon had been asking if Williams could get the Quarry Men work, so Williams suggested the Quarry Men audition for Parnes.

At this juncture, John Lennon’s group didn’t have a fixed name, being in transition between the Quarry Men and the Beatles. Lennon’s friend Bill Harry recalls a discussion with John and Stuart about wanting a name similar to Buddy Holly and the Crickets. They worked through a list of insects before selecting beetles. During the first half of 1960 the band would be known variously as the Beetles, the Silver Beetles, Silver Beets, Silver Beatles (with an a) and the Beatals, before finally becoming the Beatles. The precise sequence of these names and how exactly they decided on their final name has become confused over the years, with many claims and counter-claims as to how it happened. An obscure British poet named Royston Ellis, who spent an evening with John and Stuart at Gambier Terrace in June 1960, says that he suggested the spelling as a double pun on beat music and the beat generation.

There have been several explanations advanced about how the Beatles got their name. I know, because it was my idea. The night when John told me the band wanted to call themselves ‘the Beetles’ I asked how he spelt it. He said, ‘B – e – e – t – l – e – s’ … I said that since they played beat music and liked the beat way of life, and I was a beat poet and part of the big beat scene, [why didn’t they] call themselves Beatles spelt with an a?

Yet Bill Harry says nobody used terms like ‘big beat scene’ on Merseyside before he started his Mersey Beat fanzine in 1961, and he chose the magazine’s name because he saw himself as a journalist with a beat, like a policeman’s beat, covering the local music scene. ‘Once we’d started [publishing] Mersey Beat, after a while we started calling the [local bands] beat groups,’ says Harry. ‘That’s where the ‘beat group’ [tag] came about, after the name Mersey Beat, the paper.’

However, the phrase ‘big beat’ had already been used: The Big Beat was, for example, a 1958 comedy-musical featuring Fats Domino. Paul himself says that it was John Lennon who dreamed up the final band name, with an A. It was certainly John who explained it best by turning the whole subject into a piece of nonsense for the début issue of Mersey Beat, published in July 1961, writing:

Many people ask what are Beatles? Why Beatles? Ugh, Beatles, how did the name arrive? So we will tell you. It came in a vision – a man appeared on a flaming pie and said unto them ‘From this day on you are Beatles with an A’. Thank you, Mister Man, they said, thanking him.

Even this explanation gives rise to debate, because Royston Ellis further claims that the night he gave John and Stuart the name Beatles he heated up a chicken pie for their supper, and the pie caught fire in the oven. Thus Ellis was the man with the flaming pie. All that can be said for sure is that John’s band didn’t call themselves ‘the Beatles’ consistently until August 1960.

Three months prior to this, at the Larry Parnes audition, they were the Silver Beetles, a band without a drummer. To enable his young friends to audition for Parnes, Allan Williams hooked them up with a part-time drummer, 26-year-old bottle-factory worker Tommy Moore. As it happened, Moore was late for the Parnes audition, so the boys borrowed Johnny Hutchinson from another auditioning band, Cass and the Casanovas. In the end the Silver Beetles were not selected by Mr Parnes to back Billy Fury on a northern tour, as they had hoped, but they were offered a chance to back one of the impresario’s lesser acts, Liverpool shipwright John Askew, who, in light of the fact he sang romantic ballads, had been given the moniker Johnny Gentle. The Silver Beetles were to go with Johnny on a seven-date tour of provincial Scotland. It was not what they wanted, but it was something, and in preparation for this, their first foray into life as touring musicians, the boys chose stage names for themselves. Paul styled himself Paul Ramon. In mid-May 1960 they took the train from Liverpool Lime Street to the small town of Alloa, Clackmannanshire.

There was only a brief opportunity to rehearse before Johnny Gentle and the Silver Beetles went on stage for the first time in Alloa on Friday 20 May 1960. Johnny explained his act to the boys: he said he came on like Bobby Darin, in a white jacket, without a guitar, and stood at the mike singing covers such as ‘Mack the Knife’, before ending with a sing-along to Clarence Henry’s ‘I Don’t Know Why I Love You But I Do’. Paul was the first to grasp what Johnny required from his backing band. ‘He just seemed to know what I was trying to get over. He was one step ahead of John in that sense.’ After Johnny’s set, which went over well enough, the star signed autographs for his girl fans. The Silver Beetles played on, so everybody could have a dance. Johnny noticed that, as he signed, the girls were looking over his shoulder at his backing band, as much if not more interested in them than him.

On tour, Johnny’s hotel bills were paid direct from London by Larry Parnes. The Silver Beetles were not so well looked after, and soon ran out of cash. Lennon called Parnes, demanding help. The promoter referred him to their ‘manager’ Allan Williams, who belatedly sent money, but not before the boys had been obliged to skip out of at least one hotel without paying their bill. Talking with Gentle, Lennon asked if Parnes would be interested in signing them permanently; he seemed more professional than Williams. Gentle asked Parnes, but he declined: ‘No, they’ll be fine for any gigs I get for you lads up North. But I don’t want to take on any more groups. We’ve got enough down here [in London].’

‘At the moment he’s a bit tied up,’ Johnny reported diplomatically.

‘Never mind,’ replied Lennon. ‘We’ll make it some other way.’ It was that confidence again. Not just with Paul. The whole band possessed remarkable self-assurance. They didn’t have a regular drummer ‘and they had a bass player that was fairly useless’, as Johnny observes of Stuart Sutcliffe, ‘[but] they had that belief that they were going to make it’.

Driving from Inverness to Fraserburgh on 23 May Johnny crashed their touring van into an oncoming car, causing drummer Tommy Moore to bash his face against the seat in front of him, breaking some teeth. The boys took the injured man to hospital, but Lennon soon had Moore out of bed, telling him: ‘You can’t lie here, we’ve got a gig to do!’ Tommy played the Fraserburgh show with his jaw bandaged but, not surprisingly, quit the Silver Beetles when they all got home to Liverpool a few days later. He went back to his job in the bottle factory. The boys went round to Tommy’s to plead with him to change his mind, but his girlfriend gave them short shrift. ‘You can go and piss off!’ she shouted out the window. ‘He’s not playing with you any more.’

Broke and drummerless, the boys asked Williams if he had any more work, and were rewarded with perhaps the lowliest gig in their history. Allan had a West Indian friend, nicknamed Lord Woodbine for his partiality to Woodbine cigarettes, who was managing a strip club on Upper Parliament Street. Lord Woodbine had a stripper coming in from Manchester named Janice who would only work to live music. The Silver Beetles were persuaded to accompany Janice. ‘She gave us a bit of Beethoven and the Spanish Fire Dance,’ Paul recalled. ‘… we said, “We can’t read music, sorry, but instead of the Spanish Fire Dance we can play the Harry Lime ChaCha, which we’ve arranged ourselves, and instead of Beethoven you can have “Moonglow” or “September Song” – take your pick … So that’s what she got.’

The boys got a little more exposure when they filled in at the Jacaranda for Williams’s house band, a Caribbean steel band, who had upped-sticks and left one night, deciding they could do better elsewhere. The band eventually called Williams to tell him they’d gone to Hamburg in Germany, which was pulsating with life, the local club owners crying out for live music. Allan and Lord Woodbine went to see for themselves. In the city’s red light district they met a club owner named Bruno Koschmider, a former First World War airman and circus clown with a wooden leg (some said his leg had been shot off in the war). A sinister impression was emphasised by the fact that Koschmider’s staff addressed him as Führer. Herr Koschmider told Williams that his Hamburg customers were mad for rock ’n’ roll music, but Germany lacked good, home-grown rock bands. He needed English bands. No agreement was reached at this meeting, but some time later Williams ran into Koschmider in London and this time Williams persuaded the German to take a young Liverpool act he nominally managed named Derry and the Seniors, featuring Howard ‘Howie’ Casey on saxophone. Derry and the Seniors did so well in Hamburg that Koschmider asked for an additional Liverpool act. This time Allan suggested the Silver Beetles. Howie Casey, who had seen the boys give their amateurish audition for Larry Parnes, advised Williams against sending a second-rater over in case they spoilt things. The matter would be moot, anyway, unless Allan could persuade the boys’ guardians to let them go.

The Silver Beetles were all under 21, and a trip to Germany would disrupt what plans their families had for their future. Paul had started out as a promising student at the Liverpool Institute, passing O-level Spanish a year early. But music soon displaced hard study, and he did so poorly in his main O-levels he was kept back a year. Paul had just taken his A-levels, with half a hope of going to teacher-training college. It was an ambition Jim McCartney wanted to hold him to. ‘All the families were against them going,’ says Allan Williams, who drew upon his experience as an encyclopaedia salesman to talk the adults round. ‘I sort of described Hamburg as a holiday resort!’ Jim McCartney was a particularly hard sell, knowing Mary would have wanted her son to get on with his studies and become a teacher, or something else in professional life. Still, if Paul really meant to go, his father knew it would be a mistake to try and stop him.