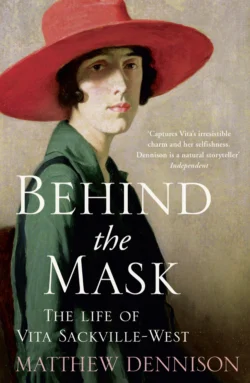

Behind the Mask: The Life of Vita Sackville-West

Matthew Dennison

Matthew Dennison creates a revealing portrait of the brave and charismatic Vita, in the first biography of her to be written for thirty years.Vita Sackville-West was a woman who defied categorisation. She was the dispossessed girl whose lonely childhood at Knole inspired enduring feats of imagination, the celebrated author and poet, the adored and affectionate wife whose marriage included passionate homosexual affairs (most famously with Virginia Woolf ), and the recluse who found in nature and her garden at Sissinghurst Castle solace from the contradictions of her extraordinary life. In this dazzling new biography, Matthew Dennison traces these complexities, depicting a prolific, radical, sensitive and uncompromising figure in all her depth.

Matthew Dennison

Behind the Mask: The Life of Vita Sackville-West

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com (http://www.williamcollinsbooks.com/)

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2014

Copyright © Matthew Dennison 2014

Matthew Dennison asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Front cover shows Lady with a Red Hat (oil on canvas), Strang, William (1859–1921) / Art Gallery and Museum, Kelvingrove, Glasgow, Scotland © Culture and Sport Glasgow (Museums) / Bridgeman Images; Shutterstock.com (http://www.shutterstock.com/) (roses)

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007486960

Ebook Edition © October 2014 ISBN: 9780007486977

Version: 2015-05-20

Dedication

For Gráinne, with all love

‘… he told her that he could find no words to praise her; yet instantly bethought him how she was like the spring and green grass and rushing waters.’

(Orlando, Virginia Woolf)

‘All the coherence of her life belonged to Condaford; she had a passion for the place … After all she had been born there … Every Condaford beast, bird and tree, even the flowers she was plucking, were a part of her, just as were the simple folk around her in their thatched cottages, and the Early-English church, where she attended without belief to speak of, and the grey Condaford dawns which she seldom saw, the moonlit, owl-haunted nights, the long sunlight over the stubble, and the scents and sounds and feel of the air.’

John Galsworthy, Maid in Waiting (1931)

‘… we write, not with the fingers, but with the whole person. The nerve which controls the pen winds itself about every fibre of our being, threads the heart, pierces the liver.’

Virginia Woolf, Orlando (1928)

List of Illustrations

1. Vita by Philip Alexius de László, oil on canvas, 1910 (© National Trust Images/John Hammond)

2. Vita with her mother; Vita with her father

3. Knole; King’s Bedroom, Knole (© English Heritage)

4. Harold, Vita, Rosamund Grosvenor and Lionel Sackville on their way to court; Vita and her parents (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

5. Vita as Portia by Clare Atwood, oil on canvas, 1910 (© National Trust Images)

6. Vita and Mrs Walter Rubens (© Illustrated London News Ltd/Mary Evans); Vita (© Illustrated London News Ltd/Mary Evans)

7. Sir Harold Nicholson, c.1920 (© Private Collection/Bridgeman Images); Vita at Ascot with Lord Lascelles (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

8. Violet Keppel by Sir John Lavery, oil on canvas, 1919 (© National Trust Images)

9. Vita and her two sons (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

10. View of Long Barn, Kent, in Winter by Mary Margaret Garman Campbell, oil on paper, c.1927–8 (© National Trust/Charles Thomas)

11. Vita at the BBC (© BBC/Corbis); Vita in sitting room at Long Barn with her sons (© Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS)

12. Vita (© Mary Evans/Everett Collection)

13. Dorothy Wellesley by Madame Yevonde (© The Yevonde Portrait Archive); Virginia Woolf (Photo by Mondadori Portfolio via Getty Images); Hilda Matheson by Howard Coster (© National Portrait Gallery, London)

14. Sissinghurst Tower (© Niek Goossen/Shutterstock); White Garden at Sissinghurst (© Eric Crichton/CORBIS)

15. Vita by John Gay, 1948 (© National Portrait Gallery, London); Vita in the Sissinghurst Tower by John Hedgecoe, 1958 (© 2006 John Hedgecoe/Topham/The Image Works)

16. Vita’s desk by Edwin Smith, 1962 (© Edwin Smith/RIBA Library Photographs Collection)

Preface

VITA SACKVILLE-WEST ONCE described herself as someone who loved ‘books and flowers and poetry and travel and trees and dragons and the wind and the sea and generous hearts and spacious ideals and little children’.[1 - Vita to Harold, 30 July 1919, quoted in Nigel Nicolson, ed., Vita & Harold: The Letters of Vita Sackville-West & Harold Nicolson 1910–1962 (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 1992), p. 97.] Later she added that she loved ‘literature, and peace, and a secluded life’.[2 - Vita to Harold, 13 December 1928, quoted in ibid., p. 210.]

There is no reason to doubt her. ‘Books and flowers and poetry’ became the outward purpose of her life: at the time of her death she was famous twice over, as a writer and a gardener. She never lost the taste for travel that began during her enormously privileged childhood; at home, she balanced curiosity and wanderlust with a powerful need for solitude (‘peace, and a secluded life’). Her love of nature – ‘trees and … the wind and the sea’ – is among her defining attributes as a poet and a novelist. It also shaped her understanding of the role of the landowning aristocracy to which she belonged, and in particular of her own role as a dispossessed aristocrat in the twentieth century. I interpret those ‘dragons’ symbolically. Vita was an extravagant dreamer. Her self-perception was shaped by myths and fairy tales. Intensely imaginative, like many artists she realised early in her life the subjectivity both of reality and realism. She valued intensity of feeling. She once described the ideal approach to life as ‘the ardour that [lights] the whole,/ Not expectation of that or this’.[3 - V. Sackville-West, The Garden (Michael Joseph, London, 1946), p. 10.] And she admired – and inclined to – lavishness. ‘I like generosity wherever I find it.’[4 - V. Sackville-West, In Your Garden (Michael Joseph, London, 1951), p. 49.]

As in most lives, Vita defined ‘spacious ideals’ to suit herself. So too, although with greater particularity, ‘generous hearts’. These are the qualities which overwhelm Vita’s posthumous reputation. Since publication more than forty years ago of her confessional autobiography, written in 1920, in which she described her passionate affair with her childhood friend Violet Keppel, Vita’s literary achievements and the plantsmanship of her garden at Sissinghurst Castle have played second fiddle to her role as lesbian icon. Vita’s affair with Violet Keppel, described in Portrait of a Marriage, changed her life; it altered the course of what has become one of the best-known marriages of the last century, to diplomat, politician and writer Harold Nicolson, himself predominantly homosexual.

I suggest that this affair defines Vita as a person only to the extent that it demonstrates her determination to realise in her life the fullest possible understanding of the terms ‘spacious ideals’ and ‘generous hearts’. In arriving at working definitions of those terms, Vita hurt herself and others too, including her husband and her own ‘little children’, Ben and Nigel Nicolson. She was occasionally selfish, occasionally cruel. Jilted lovers threatened physical violence and legal action; on one occasion, Vita was forced to wrestle a pistol out of a lover’s grip; amorous entanglements forced Vita to deception and concealment. Neither her selfishness nor her cruelty was deliberate; blind to the small scale, she was without pettiness. ‘To hope for Paradise is to live in Paradise, a very different thing from actually getting there,’ she once wrote.[5 - Jane Brown, Vita’s Other World: A Gardening Biography of V. Sackville-West (Viking, London, 1985), p. 87.] She was a lifelong romantic, who understood herself well enough to recognise the slipperiness of her grasp on happiness. Her quest was for ‘beauty and comprehension, those two smothered elements which hide in all souls and are so seldom allowed to find their way to the surface’.[6 - V. Sackville-West, Grand Canyon (Michael Joseph, London, 1942), p. 206.]

We should not lose sight of the ‘irresistible charm’, remembered by those closest to her, her ‘nobility and grandeur … largeness and generosity in everything she did or said or felt’ – but must set against it the vehemence of her need for privacy and her obsessive secrecy.[7 - Sackville-West/Evelyn Irons Archive, The Dobkin Collection of Feminism and Judaica, Dobkin Collection Item 4655540, Glenn Horowitz Bookseller, New York.] Even her immediate family sometimes had no idea of Vita’s current literary project.

Vita consistently legitimised her peccadilloes in her writing. Internal debates, the need for secrecy among them, were played out in black and white on the printed page, albeit in the case of her sexuality in necessarily disguised form. Of the heroine of her best novel, All Passion Spent, Vita wrote in 1930, ‘Pleasure to her was entirely a private matter, a secret joke, intense, redolent, but as easily bruised as the petals of a gardenia.’[8 - V. Sackville-West, All Passion Spent (The Hogarth Press, London, 1931), p. 268.] It was Vita’s own mission statement as faithless wife and lover. Through concealment, she achieved the compartmentalisation of her life that was essential to her. She rationalised it unapologetically as ‘carry[ing] one’s life inside oneself’.[9 - Victoria Glendinning, Vita: The Life of V. Sackville-West (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 1983, repr. Penguin, London, 1984), p. 195.]

The equation of pleasure and privacy was fundamental to Vita. She rebelled behind closed doors or within the safety of a small circle of friends gathered frequently from her own elite background. She did not advertise her transgressions, but maintained her ‘secluded life’. She once described the literary hostess Lady Ottoline Morrell as ‘a very queer personality … with masses of purple hair, a deep voice, teeth like a piano keyboard and the most extraordinary assortment of clothes, hung with barbaric necklaces … a born bohemian by nature’.[10 - Vita to Margaret Howard, undated, quoted in Observer, 13 July 2008.] Vita never imagined herself ‘a born bohemian’. Her identity as daughter of Knole, the great Sackville house in Kent, overruled all other personae.

On 27 June 1890, less than two years before Vita’s birth, her mother Victoria Sackville-West wrote in her diary, ‘What a heavenly husband I have and how different our love and union is from that of other couples.’[11 - Victoria Sackville diary, 27 June 1890, Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington.] In time – and repeatedly – Vita would say something similar; Harold told her that ‘our love is something which only two people in the world can understand’ and that ‘the thought of you is a little hot water bottle of happiness which I hug in this cold world’.[12 - Harold to Vita, 12 May 1926 and 21 December 1944, quoted in Nicolson, ed., Vita & Harold, pp. 139, 360.] There is a variant on these statements for every happy marriage.

Vita claimed that hers was not an intellectual background, but she was mistaken when she insisted that analysis did not intrude upon her parents’ lives. Her mother’s diary contradicts her. Happily the trait, like many in Vita’s makeup, was inherited. The result is that Vita’s was a thoughtful and thought-provoking life, even if, surprisingly, she excluded the bulk of her questioning from her diary or, in some cases, her letters, choosing instead to resolve her conflicts in her poetry and prose (unpublished as well as published). She was a consistently autobiographical author, even in her nonfiction; in the best of her writing this autobiographical element was skilfully handled and subtly nuanced. Through role-play scenarios in her writing, Vita expanded and explained her sense of herself. I suggest that it was these varied roles, recognised and understood by those nearest to her, which provided this shy but uncompromising woman with the masks she needed to live the several lives she almost succeeded in uniting.

In her introduction to the diary of her redoubtable seventeenth-century kinswoman Lady Anne Clifford, Vita stated, ‘Few tasks of the historian or biographer can be more misleading than the reconstruction of a forgotten character from the desultory evidence at his disposal.’[13 - V. Sackville-West, The Diary of Lady Anne Clifford (William Heinemann, London, 1923), p. xxiv.] She indicated the danger of posthumous judgements based on ‘a patchwork of letters, preserved by chance, independent of their context’. That argument is a truism of all biography. In revisiting Vita’s own life story, I have supported the evidence of letters and her diary with the textual evidence of so much of her writing: poetry, novels, plays, short stories, travel books, books of literary criticism, biography and journalism. The sections of this book are named after Vita’s own novels and poems (or, in the case of Part Four, a book written about Vita during her lifetime by Virginia Woolf, who knew her well and loved her). Such recourse, I recognise, is a commonplace of literary biography; it is particularly apt in Vita’s case. ‘Few things are more distasteful than veiled hints,’ Vita wrote once, addressing head on rumours of lesbianism on the part of the Spanish saint, Teresa of Avila.[14 - V. Sackville-West, The Eagle and the Dove (Michael Joseph, London, 1943), p. 22.] I believe that her writing is full of hints – sometimes veiled, sometimes otherwise – indicative of her state of mind, her emotional dilemmas, the nature of her engagement with herself and the world around her. I have used these ‘hints’ to support more conventional evidence in order to reach the fullest possible picture of this remarkable woman. As Vita herself concluded about St Teresa, ‘every point concerning so complex a character and so truly extraordinary a make-up is of interest as possibly throwing a little extra light on subsequent behaviour’.[15 - Ibid.]

Vita never fully succeeded in explaining herself to herself. In one of her poems she imagined staring at her reflection in a mountain pool: ‘seen there my own image/ As an upturned mask that floated/ Just under the surface, within reach, beyond reach’.[16 - V. Sackville-West, ‘Black Tarn’, Collected Poems: Volume One (The Hogarth Press, London, 1933), p. 139.] I hope that the present account, which does not attempt a blow-by-blow chronology of her life, helps to bring reflections of Vita closer within reach.

PROLOGUE

Heritage

‘Those brief ten years we call Edwardian … were a gay and yet an earnest time … Money nobly flowed. Ideals changed … “Respectability”, that good old word, … sank into discredit … Among most of the wealthy, most of the titled, most of the gay and extravagant classes, a wider liberty grew.’

Rose Macaulay, Told by an Idiot, 1923

THE SUM OF money at stake was impressively large. At his death on 17 January 1912, Sir John Murray Scott, sixty-five-year-old great-grandson of Nelson’s captain of the fleet Sir George Murray, left estate valued at £1.18 million (the equivalent, at today’s values, of around £80 million).[17 - Calculation based on £5 in 1912 being equivalent to the purchasing power in 2014 of £330.] The challenge to Sir John’s will brought by his family the following year was heard in a packed courtroom. An eight-day trial conducted by England’s foremost barristers, it made headlines on both sides of the Atlantic. It transformed its plaintiffs – a family notable for reserve and taciturnity – into reluctant celebrities. In the process, it exposed the deceits and compromises of Edwardian morality, stripping away the veneer of well-mannered discretion to reveal a cynical culture of avarice and lust, a preference for appearances over truth.

Like many rich men, Sir John had enjoyed playing a cat-and-mouse game with family and friends over the contents of his will, which extended to numerous bequests. Principal legatees were his brothers and sisters – middle-aged, unmarried, overweight: the sober-minded offspring of a Scottish doctor. Collectively they inherited £410,000 and the family’s London home in Connaught Place plus contents. Further legacies, to the tune of £223,000, benefited a series of recipients. A single large legacy provided the bone of contention. In addition to furniture and works of art valued at the enormous total of £350,000, childless bachelor Sir John left £150,000 in cash to the woman he described as ‘ma chère petite amie’.

Victoria Sackville-West was fifty years old. Of mixed English and Spanish parentage, she had the wide-eyed gaze of a languorous fawn, a complexion which, with care, had retained its lustre into middle age and an ample bosom ideally suited to the role of Edwardian grande dame. In her youth, she claimed she had received twenty-five proposals of marriage before accepting her husband, who was also her first cousin and heir to one of the greatest houses in England; she was a vain and fanciful woman. At twelve stone, her height five feet seven inches, she may no longer have been as ‘petite’ as formerly: undimmed were her powers of persuasion and her theatricality. She was also prone to an unpredictable Latin exactingness. This trait appears to have had an invigorating rather than an alienating effect on admirers including the American millionaire banker John Pierpont Morgan, hero of the Sudan, Lord Kitchener, and Observer editor J. L. Garvin. Rudyard Kipling described Victoria as ‘on mature reflection the most wonderful person I have ever met’; throughout her life she attracted rich and powerful men.[18 - Susan Mary Alsop, Lady Sackville: A Biography (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 1978), p. 147.] Even less sympathetic onlookers acknowledged her distinctive allure. ‘In her too fleshy face, classical features sought to escape from the encroaching fat. An admirable mouth, of a pure and cruel design, held good. It was obvious that she had been beautiful.’[19 - Violet Trefusis, Don’t Look Round (Hutchinson, London, 1952), p. 43.] Counsel for the prosecution described her damningly as possessing all ‘the fascinations of an accomplished woman’.[20 - The New York Times, 27 June 1913.] Unspoken accusations of immorality added a tang to the courtroom proceedings.

In fact the ‘affair’ of Sir John Murray Scott and Victoria Sackville-West was a sentimental friendship of rare intensity, a compromise at which the latter excelled. Their relationship was almost certainly unconsummated. In her diary Victoria claimed to be ‘much too fond of [her] husband to flirt with anybody’;[21 - Robert Sackville-West,Inheritance: The Story of Knole and the Sackvilles (Bloomsbury, London, 2010), p. 198.] the frisky baby talk of her letters to Scott suggests otherwise. Bachelor Sir John may have been over-fastidious in the matter of sex.

Victoria’s past was romantic and picaresque. She was illegitimate, Catholic, the daughter of a small-town Spanish dancer Josefa Durán, known as Pepita, ‘the Star of Andalusia’. Pepita had become the mistress of an English nobleman. She bore him seven children, including Victoria. In a bid for respectability, she reinvented herself as Countess West and enlisted kings and princes as godparents to her illegitimate children. At her lover’s request, she set up home on the French coast southwest of Bordeaux, away from the eyes of the world.

Like Sir John, Victoria had lived part of her life in Paris. Until her absent father reappeared to rescue her, she had been educated for a governess at the Convent of St Joseph on rue Monceau. In 1890 she became chatelaine of Knole in Kent. She described it with simple pride – and truthfully – as ‘bigger than Hampton Court’. The vast house was the ancestral home of her husband, Lionel Sackville-West. Victoria learned swiftly that the income which supported it was less splendid. That Victoria’s husband was also her first cousin was a curious twist worthy of Victorian popular fiction: the English nobleman, Pepita’s lover, was the 2nd Baron Sackville, not only Victoria’s father but her husband’s uncle. Pepita died in 1871, her lover, Lord Sackville, in 1908. In the absence of legitimate offspring the latter’s title passed to his nephew.

After ‘ten perfect years of the most complete happiness and passionate love’, Lionel and Victoria’s marriage had turned sour.[22 - Victoria Sackville, ‘The Book of Happy Reminiscences for my Old Age, Started on my 61st Birthday, 23rd Sept. 1922’, Lilly Library.] In the summer of 1913, the couple had a single child, their daughter Vita, who had lately celebrated her twenty-first birthday. Given her sex, the Sackville title would again descend collaterally. Meanwhile, out of love with his wife, Lionel took a series of mistresses: Lady Camden, Lady Constance Hatch, called Connie, an opera singer called Olive Rubens. Like miscreants on a saucy seaside postcard, Lionel and Lady Connie played a lot of golf.

Sir John Murray Scott had been a giant of a man. Measuring more than five feet around the waist and tall too, he weighed in excess of twenty-five stone. He died of a heart attack. The fortune he left behind him derived neither from his family nor his own entrepreneurialism. Instead, in 1897, he had inherited £1 million from his employer, a former shop girl who had caught the eye of Sir Richard Wallace, first as his mistress and afterwards his wife. Wallace was the illegitimate son of the 4th Marquess of Hertford. Lord Hertford left him estates in Ireland, a Parisian apartment of legendary magnificence at 2 rue Laffitte and the chateau de Bagatelle, a charming neoclassical maison de plaisance built by Louis XVI’s brother, the comte d’Artois, and surrounded by sixty acres of the Bois de Boulogne to the west of Paris. To this splendid inheritance Wallace had added a lease on Hertford House in London, today home of The Wallace Collection, which is named after him. All these glittering prizes Lady Wallace willed to John Murray Scott. For three decades he had served the Wallaces as their devoted secretary. No conditions restricted the bequest. He was free to act as he wished, which is exactly what he did.

What Sir John wished was to help his ‘chère petite amie’. In a letter delivered to Victoria after his death, he had written, ‘It will be found that I have left you in my Will … a sum of money which I hope will make you comfortable for life and cause all anxiety as to your future ways and means to cease.’[23 - Alsop, Lady Sackville, p. 172.] Gratitude inspired his generosity: ‘You did everything to make my broken life, and my last words to you are: “I am very grateful.”’[24 - Ibid.] Victoria had ensured that Sir John, or ‘Seery’ as the Sackvilles called him, was fully aware of the contrast between his own wealth and the relatively modest income generated by the Sackville estates (a sum of £13,000 a year, recently estimated at ‘perhaps a third of what was needed to support an establishment such as Knole’[25 - Sackville-West, Inheritance, p. 212.]). As an added sweetener to his £500,000 bequest, he left Victoria a diamond necklace that had once belonged to Queen Catherine Parr, a pocket book of Marie Antoinette’s and, from Connaught Place, a bust by eighteenth-century French sculptor Houdon and a chandelier. Together, chandelier and sculpture were worth a further £50,000: Sir John intended them for Knole. For good measure, he left a second diamond necklace to Victoria’s daughter Vita and a valuable pearl necklace, which became his posthumous twenty-first birthday present to her.

A fly on the wall in Connaught Place would have known the way the wind was blowing long before writs were issued. Even during Sir John’s lifetime, his siblings had referred to Lionel and Victoria as ‘the Locusts’. Sir John had made Victoria a number of ‘gifts’ in the dozen years of their friendship. Beginning with a modest single payment of £42 8s 6d, these ultimately amounted to a figure close to £84,000. In several instances the purpose of these gifts was understood to be expenses relating to Knole or the settlement of Sackville debts and mortgages (a handout of £38,600, for example, begun as a loan for this purpose, was subsequently written off). The real recipients were not Victoria but Lionel and Knole. In addition, at a cost of £17,000, Sir John had provided Victoria with a handsome London townhouse at 34 Hill Street in Mayfair. With little regard for the feelings of his unmarried sisters, who nominally kept house for him, Victoria chose to divide much of her time between Hill Street and Connaught Place. There she rearranged the furniture, instructed the servants, commandeered Sir John’s carriage and hosted dinner parties from which she excluded his sisters Miss Alicia and Miss Mary. She dismissed them both as irredeemably drab. Sir John did not object. To rub salt into the wound, he presented Victoria with a handsome and valuable red lacquer cabinet, which he had bought for his sisters’ boudoir. By the summer of 1913, in the eyes of her opponents, Victoria’s offences were manifold.

The case that began on 26 June concerned Victoria’s exercise of ‘undue influence’ over Sir John’s will. As The New York Times explained to American readers, F. E. Smith, counsel for the prosecution, ‘in concluding his nine hours’ [opening] speech, said the question was whether the testator at a vital and critical moment was in a position to give free play to his own wishes or whether he was so under the influence of Lady Sackville that the decisions he took were not his, but hers’.[26 - The New York Times, 27 June 1913.] Sir John’s siblings were clear on the matter. So, too, was Victoria. Dressed with colourful and costly panache, she gave a bravura performance in the witness box. In one of several early, unpublished novels, Vita reimagined her mother’s triumph: ‘Her evidence was miraculous in its elusiveness; she held the court’s attention, charmed the judge, took the jury into her confidence, routed the opposing counsel, wept at some moments, looked beautiful and distressed …’[27 - Sue Fox and Sarah Funke, Vita Sackville-West (catalogue of manuscript material), Glenn Horowitz Bookseller (New York, 2004), p. 24.] The jury needed only twelve minutes to reach their judgement. Victoria emerged victorious and just about exonerated. The judge, Sir Samuel Evans, acclaimed her as a woman of ‘very high mettle indeed’; afterwards Victoria made a friend of him. The Pall Mall Gazette reached a less partial assessment: ‘Sir John was ready to give, and Lady Sackville scrupled not to receive.’ In acknowledgement of her gratitude, Victoria afterwards invited all twelve jurymen to her daughter’s wedding.

As long ago as 17 June 1904, Victoria had confided to her diary ‘I hate gossiping’.[28 - Victoria Sackville diary, 17 June 1904, Lilly Library.] Later she wrote, ‘People may do what they like but it ought to be either sacred or absolutely private. It is nobody’s business to know our private life. The less said about it, the better …’[29 - Victoria Sackville, ‘Book of Happy Reminiscences’, Lilly Library.] It was fear of exposure which added a frisson to Edwardian misbehaviour. ‘The code was rigid,’ Vita later wrote in a novel about the period. ‘Within the closed circle of their own set, anybody might do as they pleased, but no scandal must leak out to the uninitiated. Appearances must be respected, though morals might be neglected.’[30 - V. Sackville-West, The Edwardians (The Hogarth Press, London, 1930), p. 100.]

Swayed by such feelings, and in an attempt to shield her husband and her daughter from scandal, Victoria had written to the Scotts’ counsel on the eve of the trial, ‘Do Spare Them, and attack me as much as you like.’[31 - Alsop, Lady Sackville, p. 160.] Her plea fell on deaf ears. Her victory involved the very public airing of family secrets she had hoped to conceal; even Lady Connie was called on to give evidence. Among unwelcome revelations were those concerning the Sackville finances, aspersions on Victoria’s own morality and rapacity, and an exposé of Lionel’s relationship with Lady Connie, with all the associated inferences to be drawn about the Sackvilles’ marriage. In Leicester Square, the Alhambra Theatre, home of popular music-hall entertainment, staged a musical revue based on the trial. One of Victoria’s maxims confided to Vita was, ‘One must always tell the truth, darling, if one can, but not all the truth; toute verité n’est pas bonne à dire.’[32 - V. Sackville-West, Pepita (The Hogarth Press, London, 1937), p. 230.] With hindsight, it sounds like closing the stable door when the horse had already bolted. The public display of the Sackvilles’ dirty linen offended every stricture of aristocratic Edwardian conduct: it would mark them for the remainder of their lives. Both Lionel and Victoria paid a high price for the latter’s hard-fought riches. As Vita wrote afterwards, they would realise ‘that innocence was no shield against the pointed fingers of the crowd’.[33 - V. Sackville-West, The Death of Noble Godavary and Gottfried Künstler (Ernest Benn, London, 1932), p. 148.]

Yet rich Victoria undoubtedly was. Disregarding Sir John’s unspoken wish that she transfer the contents of the rue Laffitte apartment to Knole, Victoria sold them en bloc to French antiques dealer Jacques Seligmann for £270,000. They were dispersed across the globe, the memory of their rich assembly confined to a short story, Thirty Clocks Strike the Hour, which Vita published in 1932. ‘There were silence and silken walls, and a faint musty smell, and the shining golden floors, and the dimness of mirrors, and the curve of furniture, and the arabesques of the dull gilding on the ivory boiseries.’[34 - Mary Ann Caws, ed., Vita Sackville-West: Selected Writings (Palgrave, New York, 2002), p. 59.]

Extravagant as she was covetous, Victoria settled down to living off the interest on the sum of £150,000. The capital itself became part of the Sackville Trust, in accordance with the terms of her marriage settlement. Only Vita emerged from the courtroom unscathed. Jurymen and journalists had discovered that Sir John had called her by the pet name ‘Kidlet’. Harmless enough, the label stuck.

In her diary for 7 July, Vita wrote briefly in Italian: ‘Triumphant day! All finished!’[35 - Vita’s diary, 7 July 1913, Lilly Library.] She invested the short word ‘all’ with considerable feeling. Her mother’s ‘triumph’ concluded what threatened to be costly legal action with a magnificent windfall. It also brought to an end a troubling five-year period in which the Sackvilles had been continuously involved in, or threatened with, court proceedings.

Three years earlier, in February 1910, Victoria had found herself with Lionel and, briefly, Vita, in London’s High Court. In order to defend her husband’s inheritance of the Sackville estates and title in preference to her brother, Pepita’s son Henry, Victoria was forced publicly to attest her own illegitimacy and that of her siblings. The Daily Mail called the case ‘The Romance of the Sackville Peerage’. It was anything but a romantic interlude for Victoria. Proud and spoilt, she habitually masked deep embarrassment about the circumstances of her birth behind ferocious snobbery. Had it not been for her greedy possessiveness towards Knole, she would have found it a more painful experience. Her mother and father were dead, her husband unfaithful and indifferent to her. In the cold light of the High Court she battled the treachery of her brother Henry and her spiteful, disaffected sisters Amalia and Flora. Only one of Pepita’s surviving children, Victoria’s brother Max, kept clear of the fray. As in the Scott case, Victoria and Lionel won. Knole remained theirs. They retained too the Sackville title, which assured the illegitimate Victoria the respect and deference she craved. In Sevenoaks, their victory was celebrated with a public holiday. They returned to Knole in a carriage drawn by men of the local fire brigade. Bouquets covered the seats. Defeated and deeply in debt, Henry subsequently committed suicide. Expenses associated with the case cost the Sackvilles the enormous sum of £40,000.

In a poem called ‘Heredity’, written in 1928, Vita Sackville-West asked: ‘What is this thing, this strain,/ Persistent, what this shape/ That cuts us from our birth,/ And seals without escape?’ To her cousin Eddy she would write: ‘You and I have got a jolly sort of heredity to fight against.’[36 - Glendinning, Vita, p. 124.] Dark shadows clouded Vita’s adolescence. On two occasions, crises in the life of her family became public spectacles, she herself – as ‘Kidlet’ – an unwitting heroine of the illustrated papers. Exposed to public gawping were the sexual foibles of her parents and her grandparents, and a world in which love, sex, money and rank coexisted in a greedy system of barter and plunder. Set against this was the feudal loyalty of Sevenoaks locals, the splendour of life in the rue Laffitte, where Seery entertained European royalty, and the majesty and mystery of Knole itself. It was, for Vita, a varied but not a straightforward existence: courtroom exposure of its flaws increased a tendency to regard herself as distinct and apart, which began in her childhood. Ultimately she longed to retreat from view. Inheritance became a vexed issue for Vita, and one that dominated chapters of her life and facets of her mind. Over time she regarded heredity as immutable and inescapable, but unreliable. This in turn coloured her sense of identity: an element of bravado underpinned her stubborn pride. She did not struggle to escape. Her understanding of her inheritance – temperamental, physical, material – shaped the person she became.

PART I

The Edwardians

‘While he was still an infant John learned not to touch glass cases and to be careful with petit-point chairs. His was a lonely but sumptuous childhood, nourished by tales and traditions, with occasional appearances by a beautiful lady dispensing refusals and permissions …’

Violet Trefusis, Broderie Anglaise, 1935

‘IN LIFE,’ WROTE Vita Sackville-West in her best-known novel, The Edwardians, ‘there is only one beginning and only one ending’: birth and death.[37 - V. Sackville-West, The Edwardians, p. 9.] So let it be in this retelling of Vita’s own life.

Imagine her as a newborn baby, as she herself suggested, ‘lying in a bassinette – having just been deposited for the first time in it … surrounded by grown-ups … whose lives are already complicated’.[38 - Ibid., pp. 9–10.] The bassinette stands temporarily in her mother’s bedroom. The grown-ups are Mrs Patterson the nurse and Vita’s mother and father, Victoria and Lionel Sackville-West. We have already seen something of the complications: more will reveal themselves by stages.

In the early hours of 9 March 1892, the grey and green courtyards of Knole were not, as Vita later described them, ‘quiet as a college’.[39 - V. Sackville-West, English Country Houses (William Collins, London, 1941), p. 42.] Howling and shrieking attended her birth. Outside the great Tudor house, once the palace of the Archbishop of Canterbury, once a royal palace and expansive as a village with its six acres of roof, seven courtyards, more than fifty staircases and reputedly a room for every day of the year, darkness hung heavy, ‘deepening the mystery of the park, shrouding the recesses of the garden’;[40 - V. Sackville-West, The Heir: A Love Story (William Heinemann, London, 1922; Virago repr. 1987), p. 52.] the Virginia creeper that each year crimsoned the walls of the Green Court clung stripped of its glowing leaves. Inside, a night of turmoil dragged towards dawn. Dizzy with her husband’s affection, less than two years into their marriage, Vita’s mother confessed to having ‘drunk deep at the cup of real love till I felt absolutely intoxicated’:[41 - Victoria Sackville, ‘Book of Happy Reminiscences’, Lilly Library.] not so intoxicated that the experience of childbirth was anything but terrible. Its horrors astonished Victoria Sackville-West. She wept and she yelled. She begged to be killed. She demanded that Lionel administer doses of chloroform. It was all a hundred times worse than this charming egotist had anticipated. Lionel could not open the chloroform bottle; Mrs Patterson was powerless to prevent extensive, extremely painful tearing. And then, within three quarters of an hour of giving birth, she succumbed to ‘intense happiness’. Elation displaced agony. She was dazzled by ‘such a miracle, such an incredible marvel’: ‘one’s own little baby’. She was no stranger to lightning changes of mood.

Her ‘own little baby’ was presented to Victoria Sackville-West by her doting husband. Like a precious stone or a piece of jewellery, Vita lay upon a cushion. Her tiny hands, her miniature yawning, entranced her mother. So, too, her licks and tufts of dark hair. Throughout her pregnancy Victoria had been certain that her unborn child would be a daughter. Long before she was born, Victoria and Lionel had taken to calling her Vita (they could not refer to her as ‘Baby’ since ‘Baby’ was Victoria’s name for Lionel’s penis); her wriggling in the womb had kept Victoria awake at night. On the day of Vita’s birth, Victoria headed her diary entry ‘VITA’: bold capitals indicate that she considered the name settled, inarguable. It was, of course, a contraction of Victoria’s own name, just as the daughter who bore it must expect to become her own small doppelgänger. For good measure Victoria christened her baby Victoria Mary. Mary was a sop to the Catholicism of her youth. It was also a tribute to Mary, Countess of Derby, Lord Sackville’s sister, who had once taken under her wing Pepita’s bastards when first Lord Sackville brought Victoria and her sisters to England. Vita was the only name she would use. Either way, the identities of mother and child were interwoven. Even-tempered and still infatuated, Lionel consented.

And so, at five o’clock in the morning, in her comfortable Green Court bedroom with its many mirrors and elegant four-poster bed reaching right up to the ceiling, Victoria Sackville-West welcomed with open arms the baby she regarded for the moment as a prize chattel. ‘I had the deepest gratitude to Lionel, who I was deeply in love with, for giving me such a gift as that darling baby,’ she remembered many years later.[42 - Ibid.] She omitted to mention the lack of mother’s milk which prevented her from feeding Vita: her thoughts were not of her shortcomings but her sufferings. ‘I was not at all comfy,’ she recorded with simple pique. She was ever self-indulgent. The combination of intense love, possessiveness and an assertive sort of self-absorption imprinted itself on Vita’s childhood. In different measure, those same characteristics would re-emerge throughout her life.

In the aftermath of Vita’s birth, Lionel Sackville-West retreated to his study to write letters. He may or may not have been disappointed in the sex of his child, for which Victoria, with a kind of sixth sense, had done her best to prepare him. On 9 March, he conveyed news of his new daughter to no fewer than thirty-eight correspondents. The habit of entrusting intense emotions to the page and ordering those emotions through the written word would similarly form part of Vita’s make-up. As would his daughter, Lionel wrote quickly but with care. Later he shared with her his advice on how to write well.

When Lionel was not writing he read. In the fortnight up to 27 March, he offered his French-educated bride an introduction to the works of Victorian novelist William Makepeace Thackeray. Beginning with The Book of Snobs, he progressed, via Vanity Fair, to The History of Henry Esmond. Appropriately it was Becky Sharpe, self-seeking heroine of Vanity Fair, ‘a wicked woman, a heartless mother and a false wife’, who captured Victoria’s interest. The women shared coquetry, worldliness, allure. In time Victoria would indeed prove herself capable of falsity, heartlessness and something very like wickedness. But it was the story of Henry Esmond that ought to have resonated most powerfully for Lionel and his family.

Victoria’s diary does not suggest that either husband or wife drew parallels between the novel and their own circumstances. Those are for us to identify. As the illegitimate son of an English nobleman, Henry Esmond is unable to inherit the estate of his father, Viscount Castlewood, and ineligible as a suitor for his proud but beautiful cousin Beatrix: the paths to happiness, riches, respectability and title are liberally strewn with thorns. As we have seen, the legal and social ramifications of illegitimacy would for a period dominate the married life of Lionel and Victoria Sackville-West: their affection did not survive the struggle. In turn, Vita’s own life would be shaped, indeed distorted, by her inability as a daughter to inherit her father’s title and estates. In the early hours of 9 March 1892, wind buffeted the beeches of Knole’s park, ‘dying in dim cool cloisters of the woods’ where deer huddled in the darkness;[43 - V. Sackville-West, ‘Night’, Collected Poems, p. 144.] the grey walls of the house, which later reminded Vita of a medieval village, stood impassive. All was not, as Vita wrote glibly in the fictional account of Knole she placed at the centre of The Edwardians, ‘warmth and security, leisure and continuity’:[44 - V. Sackville-West, The Edwardians, p. 51.] in her own life it seldom would be. There were very real threats to the security of her infant world. In addition, it was ‘continuity’ that demanded the perpetuation of that system of male primogeniture which was to cause her such lasting unhappiness. She once claimed for Knole ‘all the quality of peace and permanence; of mellow age; of stateliness and tradition. It is gentle and venerable.’[45 - V. Sackville-West, Knole and the Sackvilles (William Heinemann, London, 1922), p. 2.] But that statement was for public consumption. On and off, what Vita expressed publicly and what she felt most strongly failed to overlap. She was born at Knole, but died elsewhere. She would struggle to reconcile that quirk of fate.

In the short term, within days of her birth, baby Vita’s left eye gave cause for concern. Boracic lotion cleared up the problem and Victoria Sackville-West complacently committed to her diary the similarity between the blue of her daughter’s eyes and those of her great-uncle by marriage, Lord Derby. A smoking chimney in Vita’s bedroom resulted in her being moved back into her mother’s room. It was a temporary solution. Victoria’s diary frequently omits any mention of her daughter, even in the first ecstatic days which she celebrated afterwards as more wonderful than anything else in the world. Her thoughts were of herself, of Lionel, of how much she loved him. Most of all she recorded the extent of his love for her. It would be more than a month before she witnessed for the first time Mrs Patterson giving Vita her bath, a sight that nevertheless delighted her. In the meantime she rested, cocooned and apparently safe in her husband’s adoration.

These were happy days, as winter gave way to spring and Vita made her first sorties outdoors. She was accompanied on these excursions by Mrs Patterson, by her father or her grandfather, Lord Sackville. As the little convoy passed, clouds of white pigeons fluttered on to the roof, startled by the opening and closing of doors. ‘You have to look twice before you are sure whether they are pigeons or magnolias,’ Vita remembered.[46 - Ibid., p. 20.] March faded into April and ‘underfoot the blossom was/ Like scattered snow upon the grass’;[47 - V. Sackville-West, ‘April’, Collected Poems, p. 150.] in the Wilderness, close to Knole’s garden front, daffodils and bluebells carpeted the artful expanse of oak, beech and rhododendron. Sometimes, indoors, Vita was placed on her mother’s bed, with its hangings embroidered with improbably flowering trees, ‘and I watched her for hours, lying or sitting on my lap. Her little sneezes or yawning were so comic. I hugged her till she screamed.’ At other times, husband and wife lay next to one another with their baby between them. When Vita cried, Lionel walked up and down Victoria’s bedroom, cradling her in his arms. In time, when Vita had learnt to talk, ‘she used to look at each of us in turn and nod her head, saying “Dada – Mama –”. This went on for hours and used to delight us.’[48 - Victoria Sackville, ‘Book of Happy Reminiscences’, Lilly Library.]

These are common enough pictures, albeit the surroundings were uncommonly sumptuous. The air was densely perfumed with a mix of Victoria’s scent (white heliotrope, from a shop off the rue St Honoré in Paris), potted jasmine and gardenias that stood about on every surface, apple logs in the grate and, on window ledges and tables, ‘bowls of lavender and dried rose leaves, … a sort of dusty fragrance sweeter in the under layers’: the famous Knole potpourri, made since the reign of George I to a recipe devised by Lady Betty Germain, a Sackville cousin and former lady-in-waiting to Queen Anne.[49 - V. Sackville-West, Knole and the Sackvilles, p. 12.] Such conventional domesticity – husband, wife and baby happy together – is unusual in this chronicle of fragmented emotions. ‘She loved me when I was a baby,’ Vita wrote of her mother in the private autobiography that was published posthumously as Portrait of a Marriage.[50 - Nigel Nicolson, Portrait of a Marriage (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 1973, repr. 1990), p. 20.] In her diary, which she kept in French, Victoria described her baby daughter as ‘charmant’, ‘adorable’, ‘si drôle’: ‘toujours de si bonne humour’ (always so good humoured). On 17 June, she and Vita were photographed together by Mr Essenhigh Corke of Sevenoaks. But it was Lionel’s name, ‘Dada’, that Vita uttered first. It was 4 September. She was six months old.

Victoria’s diary charts Vita’s growth and progress. Some of it is standard stuff. There are tantalising glimpses of the future too. On 19 April 1892, Victoria opened a post office savings account for her daughter. Her first deposit of £12 was partly made up of gifts to Vita from Lionel and Lord Sackville. The sum represented the equivalent of nearly a year’s wages for one of Knole’s junior servants, a scullery maid or stable boy. Until her death in 1936, Victoria would continuously play a decisive role in Vita’s finances: her contributions enabled Vita to perpetuate a lifestyle of Edwardian comfort. Later the same year, Victoria introduced her baby daughter to a group of women at Knole. Vita’s reaction surprised her mother. Confronted by new faces, she behaved ‘wildly’ and struggled to get away. It is tempting to witness in her response first flickers of what the adult Vita labelled ‘the family failing of unsociability’.[51 - V. Sackville-West, Knole and the Sackvilles, p. 11.] In Vita’s case, that Sackville ‘unsociability’ would amount to virtual reclusiveness.

The faces little Vita loved unhesitatingly belonged to her dolls. Shortly after her first birthday, Victoria made an inventory of her daughter’s dolls. It included those which she herself had bought at bazaars, a French soldier and ‘a Negress’ given to Vita by Victoria’s unmarried sister Amalia, as well as Scottish and Welsh dolls. ‘Vita adores dolls,’ Victoria wrote. In the ‘Given Away’ column of her list of expenses at the end of her diary for 1896, she included ‘Doll for Vita’, for which she paid five shillings. It is the only present Victoria mentions for her four-year-old daughter and contrasts with the many gifts she bestowed on her friends, her expenditure on clothing and the sums she set aside for tipping servants. Happily Vita could not have known of this imbalance. The following year she was photographed on a sturdy wooden seat with three of her dolls, Boysy, Dorothy and ‘Mary of New York’. Wide-eyed, Vita gazes uncertainly at the viewer. She is wearing a froufrou bonnet reminiscent of illustrations in novels by E. Nesbit; her ankles are neatly crossed in black stockings and buttoned pumps. She was two months short of her fifth birthday then and had ceased to ask her mother when she would bring her a little brother;[52 - Victoria Sackville diary, 17 September 1894, Lilly Library.] she was still too young to be told of Victoria’s fixed resolve that she would rather drown herself than endure childbirth for a second time. Vita’s dolls had become her playmates and surrogate siblings. She had quickly grown accustomed to being alone: eventually solitude would be her besetting vice. For the moment her favourite doll was tiny and made of wool: Vita called him Clown Archie. He was as unlike ‘Mary of New York’, with her flaxen curls and rosebud mouth, as Vita herself, though there was nothing clown-like about the serious, dark-haired child. There never would be.

By the age of two, Vita was a confident walker. Earlier her grandfather had described to Victoria watching her faltering progress across one of Knole’s courtyards. On that occasion a footman attended the staggering toddler. In the beginning, Vita’s world embraced privilege and pomp. ‘My childhood [was] very much like that of other children,’ she afterwards asserted, itemising memories of children’s games, dressing up and pets.[53 - Nicolson, Portrait of a Marriage, p. 17.] She was mistaken. Granted, there were universal aspects to Vita’s formative years: her love for her dogs and her rabbits; her fear of falling off her pony; her disappointment at the age of five, on witnessing Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee procession from the windows of a grand house in Piccadilly, that the Queen was not wearing her crown; her frustration at her parents’ strictures; even the ugly, homemade Christmas presents she embroidered for Victoria in pink and mauve. Too often her childhood lacked a run-of-the-mill quality. Hers was a distinctive upbringing, even among her peers. Its atypical aspects shaped her as a person and a writer; shaped too her feelings about herself, her family and her sex; shaped her outlook and her sympathies, her moral compass, her emotional requirements.

The trouble lay mostly with her mother. At thirty, recovering at her leisure from her confinement, Victoria Sackville-West remained beguilingly contrary; she had not yet been wholly spoiled. On the one hand she was capricious and snobbish (she described Queen Victoria as looking ‘very common and red-faced’[54 - V. Sackville-West, Pepita, p. 181.]); on the other she was passionate and romantic, still the same eager, loving young woman who had confided to her diary with cosy delight, ‘Every day the same thing, walking … reading, playing the piano, making love’; still capable of enchantment.[55 - Alsop, Lady Sackville, p. 117.] With her hooded dark eyes and hair that tumbled almost to her knees, she was lovely to look at. In the right mood, she was exhilarating company. Like Juliet Quarles in Vita’s novel The Easter Party, ‘she was irresponsible, unstable, intemperate, and a silly chatterer – but … under all these things she possessed a warm heart’.[56 - V. Sackville-West, The Easter Party (Michael Joseph, London, 1953), p. 189.] In time the combination of beauty, wealth and position encouraged less attractive facets to her character, but this illegitimate daughter of a poor Spanish dancer had yet to forget her good fortune in marrying her cousin. Hers was the zeal of a convert, leavened at this stage with apparently boundless joie de vivre: she embraced with gusto the life of an aristocratic chatelaine that had come to her like the happy ending to a fairy tale. As she herself repeated with justification, ‘Quel roman est ma vie!’ (My life is just like a novel). No one ever persuaded her to relinquish the heroine’s role.

Victoria’s year consisted of entertaining at Knole, country house visits and extended Continental holidays; her favourite days were those she spent alone with Lionel. These were leisurely days of flirtation and passionate lovemaking, of arranging and rearranging the many rooms she thrilled to call her own. She papered one room entirely with used postage stamps and made a screen to match. She installed bathrooms, the first for Lord Sackville, one for herself and another for Vita, close to the nursery. Along the garden front of the house, she rearranged furniture in the Colonnade Room to complete its transformation into an elegant if draughty sitting room. Its walls were painted in grisaille with grand architectural trompe l’oeil; seventeenth-century looking glasses and silver sconces threw light on to deep sofas. There Vita’s fifth birthday was celebrated with a Punch and Judy show; Vita dressed on that occasion with appropriate smartness in ‘an embroidered dress with Valenciennes insertion over [a] blue silk slip’, the sort of dress Victoria herself might have worn.[57 - Victoria Sackville diary, 9 March 1897, Lilly Library.] As would her daughter, Victoria Sackville-West exulted in her splendid home. ‘Everybody says that I made Knole the most comfortable large house in England, uniting the beauties of Windsor Castle with the comforts of The Ritz, and I never spoilt the real character of Knole,’ she claimed for herself.[58 - Victoria Sackville, ‘Book of Happy Reminiscences’, Lilly Library.] Knole became her passion and filled her with a pride that was essentially vanity; she delighted in her ‘improvements’ to its vast canvas. ‘No one knew how, when the day was over and the workmen had gone home, she would lay her cheek against the panelling, marked like watered silk, and softer to her than any lips,’ imagined one of her observers.[59 - Trefusis, Violet, Broderie Anglaise (English trans., Methuen, London, 1986, repr. Minerva, London, 1992), p. 61.] She had no intention of allowing motherhood to unsettle a routine that suited her so admirably. Inevitably, her manner of life affected her daughter.

Vita’s first Christmas was spent in Genoa. It was a family party of Victoria, Lionel, Lord Sackville, Vita, and Vita’s nurse, Mrs Brown. After Christmas, Mrs Brown took Vita to the South of France to stay with Victoria’s former chaperone, Mademoiselle Louet, known as Bonny; Lionel and Victoria continued on to Rome. Vita’s parents did not cut short their travels in order to celebrate her first birthday in March 1893: they were more than 1,600 miles from their baby daughter, in Cairo. In subsequent years they exchanged Cairo for Monte Carlo, their destination for Vita’s third, fourth and sixth birthdays. On those occasions Vita remained at Knole. On 9 March 1896, Victoria enumerated in her diary her losses and winnings, and those of Lionel, at the Casino: only as a parting shot did she note ‘Vita is four today.’ She did not suggest that she missed her daughter or regretted their separation; on the same day two years later, she admitted: ‘I think so much of my Vita today.’[60 - Victoria Sackville diary, 9 March 1898, Lilly Library.] Every year there were visits to nearby London and a trip to Paris in the spring, ‘with the chestnut trees coming out and the spring sunshine sparkling on the river’.[61 - V. Sackville-West, Pepita, p. 210.]

Accommodated within this routine, Vita’s childhood was by turns permissive and repressive. From infancy she was frequently left alone at Knole with her shy and silent grandfather. Lord Sackville believed in fairies. Morose and uncommunicative in adult company, he enjoyed the companionship of a tame French partridge and a pair of ornamental cranes called Romeo and Juliet, who accompanied him on his walks outdoors. His presence in Vita’s early years was benign if detached. Together they played draughts in the hour after nursery tea: as time passed, a shared antipathy to parties and smart society types sharpened their bond. Vita endeavoured to please her grandfather: ‘She is very busy gardening and cultivates mostly salad and vegetables for her Grand Papa,’ noted Victoria when Vita was eleven.[62 - Victoria Sackville diary, 6 May 1903, Lilly Library.] Nurses and governesses oversaw Vita’s days; they were overseen in turn by Victoria, whose volatility ensured that none remained long at their post and that each dismissal could be traumatic and painful for Vita. When Vita was five, ‘Nannie’ was dismissed for theft. The truth was somewhat different. After the unexplained disappearance of three dozen quail, ordered for a dinner party, Victoria decided that Nannie had secretly consumed the entire order and acted accordingly.

With her parents abroad, as soon as she could walk Vita was free to lose herself in the self-contained fastness of Knole. She remembered ‘[splashing] my way in laughter/ Through drifts of leaves, where underfoot the beech-nuts/ Split with crisp crackle to my great rejoicing’.[63 - V. Sackville-West, ‘Beechwoods at Knole’, Collected Poems, p. 142.] She climbed trees and stole birds’ eggs. She ran wild in ‘wooded gardens with mysterious glooms’ and on one occasion she fell into a wishing well. Indoors, even the frayed and faded curtains of Knole’s state rooms possessed a peculiar power of enchantment over her. After nightfall, beginning as a small child, she wandered through the rooms with only a single candle to hold fear at bay. Hers was a playground like few others.

The company of her mother, ‘maddening and irresistible by turns’,[64 - V. Sackville-West, Pepita, p. 201.] was predictably more stringent. Victoria’s sharp tongue was quick to wound, particularly on the subject of Vita’s looks, which proved an ongoing source of disappointment. ‘Mother used to hurt my feelings and say she couldn’t bear to look at me because I was so ugly’:[65 - Nicolson, Portrait of a Marriage, p. 10.] it was Vita’s hair, with its stubborn resistance to curling, that exercised Victoria above all. She may have spoken more from pique than conviction – on 20 February 1903 she recorded in her diary, ‘The drawing of Vita by Mr Stock is finished and is quite pretty, but the child is much prettier and has far more depth and animation in her face;’[66 - Victoria Sackville diary, 20 February 1903, Lilly Library.] it was all the same to Vita. Vita subsequently categorised her mother ‘more as a restraint than anything else in my existence’,[67 - Nicolson, Portrait of a Marriage, p. 19.] but as a small child she delighted her with her quick affection and her loving nature. ‘She is always putting her little arm round my neck and saying I am the best Mama in the world,’ Victoria wrote on 1 August 1897.[68 - Victoria Sackville diary, 1 August 1897, Lilly Library.] Vita grew up to regard her mother as compelling but incomprehensible: she dreaded her unpredictability and her ability to humiliate with a look or word. ‘She wounded and dazzled and fascinated and charmed me by turns.’[69 - Diana Souhami, Mrs Keppel and her Daughter (HarperCollins, London, 1996, repr. Flamingo, London, 1997), p. 82.] Mutual misunderstanding coloured their relationship almost from the first: Vita was probably thinking of her mother when, in an essay about art composed in her late teens, she wrote, ‘It is possible, and indeed common, to possess personality allied to a mediocre soul.’[70 - Fox and Funke, Vita Sackville-West, p. 14.] In one letter, written in a round, childish hand, Vita implored Victoria to ‘forgive me. Punish me, I deserve it, but forgive me if you can and please don’t say you are sorry to have me and go on loving me.’[71 - Vita to Victoria Sackville, undated, Berg Collection (Album 1), New York Public Library.] Vita learned from Victoria that so-called loving relationships could embrace indifference, pain and even hatred, and that equality was not assured between partners in love. As she wrote in 1934 of one particularly mismatched couple in her novel The Dark Island, ‘She liked him, yet she hated him. She was surprised to find how instantly she could like and yet hate a person, at first sight.’[72 - V. Sackville-West, The Dark Island (The Hogarth Press, London, 1934), p. 42.] For Vita that model of loving and hating existed in the first instance not in stories but her family life. It was a dangerous lesson.

It was Victoria, not Lionel, who administered punishments, and Victoria who ordered Vita’s life. When Vita was five, Victoria forced her to eat dinner upstairs: ‘she is always eating raw chestnuts and they are so bad for her’.[73 - Victoria Sackville diary, 27 October 1897, Lilly Library.] Instead she insisted on simple food typical of nursery regimes of the period; Vita’s particular hatred was for rice pudding. The following year, Vita was again punished by dining upstairs: the six-year-old tomboy with the post office savings account had escaped her nursemaid in Sevenoaks in order to buy herself a ball and a balloon. Accustomed to extravagant flattery and naturally autocratic in all her relationships, Victoria inclined to high-handedness: where Vita was concerned she expected obedience. As it happened, her treatment of her daughter hardly differed from her behaviour towards her husband or her father. In each case she preferred to jeopardise affection rather than yield control.

Until Vita was four, Knole was home not only to her parents and her grandfather, but also her Aunt Amalia, ‘very Spanish and very charming’ in one estimate,[74 - Alsop, Lady Sackville, p. 139.] remembered by Vita only as ‘a vinegary spinster … [who] annoyed Mother by giving me preserved cherries when Mother asked her not to’.[75 - Nicolson, Portrait of a Marriage, p. 16.] (She annoyed Victoria more with her constant requests for money. The women were temperamentally incompatible and ‘endless rows and quarrels’ made both miserable.[76 - Sackville-West, Inheritance, p. 184.]) Also in the great house, hugger-mugger within its far-flung walls and ‘rich confusion of staircases and rooms’,[77 - V. Sackville-West, The Edwardians, p. 11.] lived Vita’s other families: four centuries of Sackville forebears, ‘heavy-lidded, splenetic’,[78 - Trefusis, Don’t Look Round, p. 42.] preserved in heraldic flourishes and the rows of portraits in which Vita would glimpse ‘our faces cut/ All in the same sad feature’;[79 - Michael Stevens, V. Sackville-West (Michael Joseph, London, 1973), p. 116.] and Knole’s servants and retainers. All influenced the small girl in their midst.

From the outset of her marriage, Victoria Sackville-West had set about rationalising Knole’s running costs. By 1907, she would successfully reduce the annual household expenditure by a third to £2,000.[80 - Alsop, Lady Sackville, p. 120.] She did so while retaining a staff of sixty, including twenty gardeners; their combined wage bill cost her father and afterwards her husband a further £3,500.[81 - Sackville-West, Inheritance, p. 191.] Few of these servants were known personally to Victoria, Lionel or Lord Sackville, or even recognised by them by sight. To Vita, free to explore regions of the house her parents seldom visited, they formed an extended kinship.

‘As a mere child, I was privileged. I could patter about, between the housekeeper’s room and the servants’ hall,’ Vita recalled in an article written for Vogue in 1931. ‘The Edwardians Below Stairs’ examines the elaborate staff hierarchies of her childhood. It also demonstrates how much of Vita’s time was spent among Knole’s servants, whom she knew by name, who shared her games and who omitted to lower their voices or silence their gossip in front of the dark-haired little girl who moved among them so easily. ‘I could help to stir the jam in the still-room or to turn the mangle in the laundry; I could beg a cake in the kitchen or a bottle of cider in the pantry; I could watch the gamekeeper skinning a deer or the painter mixing a pot of paint; my comings and goings remained unnoticed; conversation and comment were allowed to fall uncensored on my childish ears.’[82 - V. Sackville-West, ‘The Edwardians Below Stairs’, Vogue, 25 November 1931, p. 55.] As Vita wrote of Sebastian and Viola in The Edwardians, ‘As children in the house, they had of course been on terms of familiarity with the servants, particularly when their mother was away.’[83 - V. Sackville-West, The Edwardians, p. 24.] So it was in her own case.

On the surface Vita’s childhood world was one of order and stability. Foresters cut timber and sawmen sawed logs – different lengths for different fires. Melons, grapes and peaches ripened in hothouses. Victoria’s guests enjoyed clean linen sheets daily; the flowers in their rooms were rearranged with similar frequency. Extravagance was endemic, splendid in its excess – as Vita remembered it in The Edwardians, ‘the impression of waste and extravagance … assailed one the moment one entered the doors of the house’.[84 - Ibid.] It contributed the necessary note of magnificence to this feudal environment of fixed places and shared loyalties. For Knole and its denizens, the world of 1892 appeared to differ from that of 1592 only in refinement and ease: given the estate’s modest income, it was a gorgeous charade. On the shell of Victoria’s pet tortoise, as it shuffled between sitting rooms, glittered her monogram, a liquid swirl of diamonds. It was a fantastical detail, afterwards appropriated by Evelyn Waugh in the lushest of his novels, Brideshead Revisited.

That the childish Vita should take for granted these insubstantial cornerstones of her parents’ existence is inevitable. Her memories indicate something more, a window on to Vita’s position as Knole’s only child: at home upstairs and downstairs, nowhere fully at home, everywhere proprietorial, keenly aware of her connection to the house and its history – as she herself offered, ‘Small wonder that my games were played alone; …/ I slept beside the canopied and shaded/ Beds of forgotten kings./ I wandered shoeless in the galleries …’[85 - V. Sackville-West, ‘To Knole’.] Knole dominates all Vita’s memories of her childhood. She regarded it as her own munificent present and disdained to share it; later she would claim that a house was ‘a very private thing’.[86 - V. Sackville-West, All Passion Spent, p. 90.] It was also an irresistible compulsion and seeped into so many of her thoughts. ‘At the centre of all was always the house,’ she wrote in an early story: ‘the house was at the heart of all things.’[87 - V. Sackville-West, The Heir, p. 75.] It occupied voids left by the absence of more conventional emotional outlets. That she learned early on that one day she must relinquish it, that as a girl she was prevented from inheriting what she already considered her own, served only to quicken those feelings which transcended ordinary love, feelings which went too deep to be put into words, so deep that throughout her life she hardly dared examine them.

A journalist in Vita’s lifetime described Knole as ‘too homely to be called a palace, too palatial to be called a home’[88 - Nicolson, Portrait of a Marriage, p. 14.] – an outsider’s view. For Vita, even as a child, Knole was more than either home or palace. It was a living organism, ‘to others dormant but to me awake’:[89 - V. Sackville-West, ‘To Knole’.] she lavished upon it the quick affection children usually reserve for their parents. ‘God knows I gave you all my love,’ she wrote later, ‘Scarcely a stone of you I had not kissed.’[90 - See Stevens, V. Sackville-West, p. 115.] ‘So I have loved thee, as a lonely child/ Might love the kind and venerable sire/ With whom he lived,’ she claimed in a poem she dedicated to Knole.[91 - V. Sackville-West, ‘To Knole’.]

Finding her way through passages and galleries, crossing courtyards, peeping into workshops and domestic offices, what was Vita looking for and what did she see? Why did she give over her days to wandering and exploring, save for the pleasure of escaping her nursemaid or eluding her mother? At times, the connection she forged with Knole was the strongest bond of her life: to strengthen her conviction of reciprocity she endowed the house and its park with human attributes. ‘I knew thy soul, benign and grave and kind/ To me, a morsel of mortality,’ she wrote self-consciously, the night before she left Knole as a married woman for a new home of her own;[92 - Ibid.] in a later unpublished poem she went a step further and claimed that she was Knole’s soul. From a precociously young age, she was nourished and sustained by Knole’s accumulated memories: swaggering, picturesque, tragic or simply humdrum. The history she learned she read in its tapestries and portraits. In the first instance it was companionship Vita sought in the cavernous house: the romantic distraction of the past came next. ‘I knew all the housemaids by name … [and] was on intimate terms with the hall-boy … The hall-boy and I used to play cricket together.’[93 - V. Sackville-West, ‘The Edwardians Below Stairs’.] They also indulged in wrestling bouts, for which Vita was punished by being made to keep her diary in French. But the hall-boy’s name is lost and we question the intimacy of those terms.

Day by day Vita absorbed an inflated, erroneous sense of Knole’s importance. Its place in British life – the prestige of her own family – overwhelmed her imagination. That sense persisted. A novel written when she was fourteen included the question, from father to son, ‘And you can bear that name, the name of Sackville, and yet commit a disgraceful action?’[94 - V. Sackville-West, Tale of a Cavalier, quoted in Nicolson, Portrait of a Marriage, p. 63.] In fact, in the 850 years since Herbrand de Sackville had journeyed from Normandy with William the Conqueror, the Sackville achievement had been middling. Knole suggested otherwise, and it was Knole’s version of her family history that the young Vita unquestioningly imbibed and the mature Vita avoided revising.

As a child events conspired to delude her. In 1896, after Lord Sackville had persuaded the prime minister, Lord Salisbury, to make Lionel a temporary honorary attaché to the British embassy in Moscow, Lionel and Victoria set off from Knole to the coronation of Nicholas II of Russia; on the eve of departure their neighbours flocked to admire Victoria’s dresses and her jewels laid out for display like wedding presents. Two years later, the Prince and Princess of Wales lunched at Knole, in a party that included the Duke and Duchess of Sparta, heirs to the throne of Greece. Photographs show Vita and the Princess of Wales holding hands, an intimacy few six-year-olds could rival; they had stood side by side at the inevitable tree-planting ceremony. In his thank-you letter written afterwards, the prince admired Knole as ‘so beautifully kept’, a state he attributed to ‘the tender care “de la charmante Chatelaine!”’.[95 - Sackville-West, Inheritance, p. 189.] In the summer of 1897, Victoria had recorded in her diary the visit to Knole of ‘Thomas the Bond Street jeweller’. She had summoned him to examine the silver. ‘He said that we had not the largest, but the best collection of silver in England.’[96 - Alsop, Lady Sackville, p. 142.] Her life at Knole turned Victoria’s head. Knole turned Vita’s head too. In Vita’s case she knew no alternative.

The child shaped by parental absenteeism, maternal whim and her extraordinary surroundings was all angles and corners, ‘all knobs and knuckles’, ‘with long black hair and long black legs, and very short frocks, and very dirty nails and torn clothes’.[97 - Trefusis, Don’t Look Round, p. 70; Vita to Harold, 27 February 1912, quoted in Nicolson, ed., Vita & Harold, p. 23.] She regarded her mother – indeed everyone outside the closed Knole–Sackville circle – with unavoidable hesitancy. Like the Godavarys in her later novella, The Death of Noble Godavary, she mistrusted any alien element within the family circle. From an early age, she took on her grandfather’s role of showing the house to visitors: the task exacerbated a tendency to unsociability. Although by modern standards Knole’s visitor numbers were low – on a ‘busy’ August day in 1901, the tally reached twenty-seven[98 - Brown, Vita’s Other World, p. 26.] – Vita’s guide work stimulated her sense of possessiveness towards the house that would never be hers, and a rigid, atavistic pride in its glories. Showing the house was an exercise in showing off. Even as a teenager, travelling through Warwickshire en route to Scotland, Vita measured everything she saw against Knole’s yardstick. Of Anne Hathaway’s cottage she noted only its ‘very small, low rooms’, and she poured scorn on the idea that ruined Kenilworth Castle, covering three acres, had any claim to be considered ‘enormous’: ‘Knole covers between four and five acres.’[99 - Vita’s diary, 13 August 1907, Lilly Library.]

The ‘tours’ she led even as quite a young child sealed the imaginative pact Vita made with Knole. She was reluctant and unskilled at making friends, sullen and shy confronted by unknown visitors, hostile and bullying to local children to the extent that ‘none of [them] would come to tea with me except those who … acted as my allies and lieutenants’.[100 - Norman Rose, Harold Nicolson (Jonathan Cape, London, 2005), p. 42.] Knole superseded Clown Archie as her childhood love; perhaps it precluded – or prevented – other intimacies. ‘Vita belonged to Knole,’ Violet Keppel remembered; ‘to the courtyards, gables, galleries; to the prancing sculptured leopards, to the traditions, rites, and splendours. It was a considerable burden for one so young.’[101 - Trefusis, Don’t Look Round, p. 42.]

Unsurprisingly, given her surrounds, while her social instincts faltered, her imagination blossomed: her taste was for adventure. Vita was a scruffy, despotic, busy child. Her inclinations were starkly at odds with late-Victorian ideas about little girls. Victoria did her best. She commissioned elaborate fancy dress costumes, including a tinsel fairy dress, a May queen dress complete with a maypole made from wild flowers, and a flower-encrusted frock intended to transform Vita into a basket of wisteria (Victoria herself had been ‘very much admired’ when she wore a dress of similar design, with added diamonds, to a costume ball in 1897[102 - Alsop, Lady Sackville, p. 142.]). It was not enough. Neither in appearance nor character would Vita achieve conventional prettiness and all that it implied; Victoria’s diary does not suggest she always troubled to sympathise with the daughter whose nature and instincts were so different from her own. Of a seaside holiday in August 1898, her mother recorded simply: ‘Vita was much impressed by seeing a runaway horse smashing a butcher’s cart.’[103 - Victoria Sackville diary, 21 August 1898, Lilly Library.] Victoria and Lionel’s presents to Vita that year included a costly tricycle and a balloon. Even Vita’s greedy passion for chocolates and bonbons challenged Victoria’s ideas of appropriate behaviour. Concerned for her daughter’s complexion, and the figure she would later cut in the marriage market, Victoria ‘put away mercilessly what I thought was bad for her’.[104 - Victoria Sackville, ‘Book of Happy Reminiscences’, Lilly Library.]

Although she was not aware of it, Vita learnt cruelty from her mother. It was not simply that isolation bred introspection or that Knole itself made Vita a dreamer, uninterested in those outside her gilded cage. Victoria’s exactingness threatened to deprive those closest to her both of autonomy and their sense of themselves. Her unconditional love for her daughter, whose birth she had regarded as a ‘miracle’, an ‘incredible marvel’, ceased with Vita’s babyhood. In time Vita learned to fear the mother whose love was so contrary, ‘so it was really a great relief when she went away’[105 - Nicolson, Portrait of a Marriage, p. 11.]: she never stopped loving her mother extravagantly. The family name for Victoria, ‘BM’ (Bonne Mama), contained no deliberate irony. ‘I love thee, mother, but thou pain’st me so!/ Thou dost not understand me; it is sad/ When those we love most, understand us least,’ Vita’s Chatterton exclaims in the verse drama she wrote about the doomed poet in 1909.[106 - V. Sackville-West, Chatterton (repr. The Through Leaves Press, 2002), p. 10.] Vita wrote the part of Chatterton for herself. Like many who are bullied, she responded by becoming herself a bully. Children invited to Knole to play with Vita were left in little doubt of the value she placed on their companionship.