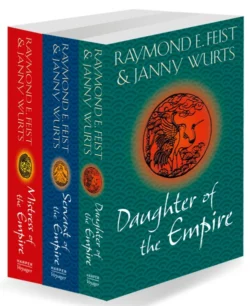

The Complete Empire Trilogy: Daughter of the Empire, Mistress of the Empire, Servant of the Empire

Janny Wurts

Raymond E. Feist

The critically acclaimed and bestselling Empire Trilogy by Raymond E. Feist and Janny Wurts, is now available in this ebook bundle.The bundle includes Daughter of the Empire (1), Servant of the Empire (2), and Mistress of the Empire (3).At age 17, Mara's ceremonial pledge of servantship to the goddess Lashima is interrupted by the news that her father and brother have been killed in battle on Trigia, the world through the rift.Now Ruling Lady of the Acoma, Mara finds that not only are her family's ancient enemies, the Minwanabi, responsible for the deaths of her loved ones, but her military forces have been decimated by the betrayal and House Acoma is now vulnerable to complete destruction…The bundle includes Daughter of the Empire (1), Servant of the Empire (2), and Mistress of the Empire (3).

RAYMOND E. FEIST

and

JANNY WURTS

The Empire Trilogy

Daughter of the Empire

Servant of the Empire

Mistress of the Empire

Copyright (#ulink_52984c41-ec21-5d3c-a7e2-aac4751bda8f)

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

HarperVoyager An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/)

First published in Great Britain by

Grafton Books 1987

Daughter of the Empire First published in Great Britain by Grafton Books 1987

Copyright © Raymond E. Feist and Janny Wurts 1987

Servant of the Empire First published in Great Britain by Grafton Books 1990

Copyright © Raymond E. Feist and Janny Wurts 1990

Mistress of the Empire First published in Great Britain by Grafton Books 1992

Copyright © Raymond E. Feist and Janny Wurts 1992

The Authors assert the moral right to be identified as the authors of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Ebook Edition © MARCH 2013 ISBN: 9780007518760

Version: 2018-5-14

Table of Contents

Cover (#u587bc474-9b41-5f88-925b-9128bcdd0e28)

Title Page (#ue6deb634-ff16-5f4f-b978-e566b1e04f9c)

Copyright (#u1e2dcee1-2afb-5453-9911-845597f15ab7)

Daughter of the Empire

Servant of the Empire

Mistress of the Empire

About the Author (#ue4318ba7-7503-511f-9c7b-8b82720e53d1)

Also by the Author (#u8dfa71b1-65c3-5e8d-a3b7-7534d22b2fc5)

About the Publisher (#u39e4fa02-ac42-52ca-ae1c-b9de51453a23)

(#u704a7d19-3888-52e9-98d9-f14115391196)

RAYMOND E. FEIST

and

JANNY WURTS

Daughter of the Empire

Book One of the Empire Trilogy

This book is dedicated to

Harold Matson

with deep appreciation, respect, and affection

Table of Contents

Cover (#u4072c0d2-90de-5bc0-b217-c19f58f8d579)

Title Page (#udbb469d1-b6b5-58bb-ae96-0609fcc31c20)

Dedication (#u9e9d6a1b-f771-5865-98ca-77eb6ba97ca2)

Map

Chapter One: Lady (#ub1e541a8-75d0-559a-b5ee-52f83e1a33ca)

Chapter Two: Evaluations (#u13745e9a-4898-58a3-9150-fe09be04c214)

Chapter Three: Innovations (#ub5a32616-03fa-583d-ac87-7713d4b53f73)

Chapter Four: Gambits (#u965e0734-25ed-583e-ab62-e58047d15086)

Chapter Five: Bargain (#ud1a52063-6b86-5989-8da6-91d8da8027d5)

Chapter Six: Ceremony (#ue8f06290-ba2d-5066-826f-fdf90a26b983)

Chapter Seven: Wedding (#u330062c7-82a9-51da-a225-6418895343b9)

Chapter Eight: Heir (#u6d2c8656-a290-5c92-b692-e1e8bd2ab688)

Chapter Nine: Snare (#ua7eb2844-2f30-531d-b522-a4c888bca8ec)

Chapter Ten: Warlord (#uc5d96dda-5c09-5f00-8c72-0bb8be161ea2)

Chapter Eleven: Renewal (#udfa4f526-7738-5b42-b52c-e504b1d919ea)

Chapter Twelve: Risks (#uefd09f40-7071-576a-973d-a135d8a75ff6)

Chapter Thirteen: Seduction (#uf2b7d3e9-029d-5966-9024-9fdf7050939b)

Chapter Fourteen: Acceptance (#u627fc210-bae9-547d-87f9-2fcf51673838)

Chapter Fifteen: Arrival (#u06054009-9ba8-5c91-ab57-e88746029f0a)

Chapter Sixteen: Funeral (#uc261d900-649d-5eb4-99f3-a5155ad2efc2)

Chapter Seventeen: Revenge (#ufc3d9452-69d1-5da4-92b5-c09843ace762)

Acknowledgements (#ud392da63-9c1c-5ee1-8d6d-402494a683e3)

Map (#u9d3ccd27-ceed-58d3-b624-10cd9d99a147)

• Chapter One • Lady (#ulink_202e0807-8ea7-5daa-9b40-8cf601ec2a32)

The priest struck the gong.

The sound reverberated off the temple’s vaulted domes, splendid with brightly coloured carvings. The solitary note echoed back and forth, diminishing to a remembered tone, a ghost of sound.

Mara knelt, the cold stones of the temple floor draining the warmth from her. She shivered, though not from chill, then glanced slightly to the left, where another initiate knelt in a pose identical to her own, duplicating Mara’s movements as she lifted the white head covering of a novice of the Order of Lashima, Goddess of the Inner Light. Awkwardly posed with the linen draped like a tent above her head, Mara impatiently awaited the moment when the headdress could be lowered and tied. She had barely lifted the cloth and already the thing dragged at her arms like stone weights! The gong sounded again. Reminded of the goddess’s eternal presence, Mara inwardly winced at her irreverent thoughts. Now, of all times, her attention must not stray. Silently she begged the goddess’s forgiveness, pleading nerves – fatigue and excitement combined with apprehension. Mara prayed to the Lady to guide her to the inner peace she so fervently desired.

The gong chimed again, the third ring of twenty-two, twenty for the gods, one for the Light of Heaven, and one for the imperfect children who now waited to join in the service of the Goddess of Wisdom of the Upper Heaven. At seventeen years of age, Mara prepared to renounce the temporal world, like the girl at her side who – in another nineteen chimings of the gong – would be counted her sister, though they had met only two weeks before.

Mara considered her sister-to-be: Ura was a foul-tempered girl from a clanless but wealthy family in Lash Province while Mara was from an ancient and powerful family, the Acoma. Ura’s admission to the temple was a public demonstration of family piety, ordered by her uncle, the self-styled family Lord, who sought admission into any clan that would take his family. Mara had come close to defying her father to join the order. When the girls had exchanged histories at their first meeting, Ura had been incredulous, then almost angry that the daughter of a powerful Lord should take eternal shelter behind the walls of the order. Mara’s heritage meant clan position, powerful allies, an array of well-positioned suitors, and an assured good marriage to a son of another powerful house. Her own sacrifice, as Ura called it, was made so that later generations of girls in her family would have those things Mara chose to renounce. Not for the first time Mara wondered if Ura would make a good sister of the order. Then, again not for the first time, Mara questioned her own worthiness for the Sisterhood.

The gong sounded, deep and rich. Mara closed her eyes a moment, begging for guidance and comfort. Why was she still plagued with doubts? After eighteen more chimes, family, friends, and the familiar would be forever lost. All her past life would be put behind, from earliest child’s play to a noble daughter’s concern over her family’s role within the Game of the Council, that never-ending struggle for dominance which ordered all Tsurani life. Ura would become her sister, no matter the differences in their heritage, for within the Order of Lashima none recognized personal honour or family name. There would remain only service to the goddess, through chastity and obedience.

The gong rang again, the fifth stroke. Mara peeked up at the altar atop the dais. Framed beneath carved arches, six priests and priestesses knelt before the statue of Lashima, her countenance unveiled for the initiation. Dawn shone through the lancet windows high in the domes, the palest glow reaching like fingers through the half-dark temple. The touch of sunrise seemed to caress the goddess, softening the jewel-like ceremonial candles that surrounded her. How friendly the lady looked in morning’s blush, Mara thought. The Lady of Wisdom gazed down with a half-smile on her chiselled lips, as if all under her care would be loved and protected, finding inner peace. Mara prayed this would be true. The only priest not upon his knees again rang the gong. Metal caught the sunlight, a splendid burst of gold against the dark curtain that shrouded the entrance to the inner temple. Then, as the dazzling brilliance faded, the gong rang again.

Fifteen more times it would be struck. Mara bit her lip, certain the kind goddess would forgive a momentary lapse. Her thoughts were like flashing lights from broken crystals, dancing about here and there, never staying long in one place. I’m not very good material for the Sisterhood, Mara confessed, staring up at the statue. Please have patience with me, Lady of the Inner Light. Again she glanced at her companion; Ura remained still and quiet, eyes closed. Mara determined to imitate her companion’s behaviour outwardly, even if she couldn’t find the appropriate calm within. The gong sounded once more.

Mara sought that hidden centre of her being, her wal, and strove to put her mind at rest. For a few minutes she found herself successful. Then the beat of the gong snatched her back to the present. Mara shifted her weight slightly, rejecting irritation as she tried to ease her aching arms. She fought an urge to sigh. The inner calm taught by the sisters who had schooled her through her novitiate again eluded her grasp, though she had laboured at the convent for six months before being judged worthy of testing here in the Holy City by the priests of the High Temple.

Again the gong was struck, as bold a call as the horn that had summoned the Acoma warriors into formation. How brave they all had looked in their green enamelled armour, especially the officers with their gallant plumes, on the day they left to fight with the Warlord’s forces. Mara worried over the progress of the war upon the barbarian world, where her father and brother fought. Too many of the family’s forces were committed there. The clan was split in its loyalty within the High Council, and since no single family clearly dominated, blood politics bore down heavily upon the Acoma. The families of the Hadama Clan were united in name only, and a betrayal of the Acoma by distant cousins who sought Minwanabi favour was not outside the realm of possibility. Had Mara a voice in her father’s counsel, she would have urged a separation from the War Party, even perhaps an alliance with the Blue Wheel Party, who feigned interest only in commerce while they quietly worked to balk the power of the Warlord …

Mara frowned. Again her mind had been beguiled by worldly concerns. She apologized to the goddess, then pushed away thoughts of the world she was leaving behind.

Mara peeked as the gong rang again. The stone features of the goddess now seemed set in gentle rebuke; virtue began with the individual, she reminded. Help would come only to those who truly searched for enlightenment. Mara lowered her eyes.

The gong reverberated and through the dying shiver of harmonics another sound intruded, a disturbance wholly out of place. Sandals scuffed upon stone in the antechamber, accompanied by the dull clank of weapons and armour. Outside the curtain an attending priest challenged in a harsh whisper, ‘Stop, warrior! You may not enter the inner temple now! It is forbidden!’

Mara stiffened. A chilling prescience passed through her. Beneath the shelter of the tented headcloth, she saw the priests upon the dais rise up in alarm. They turned to face the intruder, and the gong missed its beat and fell silent.

The High Father Superior moved purposefully towards the curtain, his brow knotted in alarm. Mara shut her eyes tightly. If only she could plunge the outside world into darkness as easily, then no one would be able to find her. But the sound of footfalls ceased, replaced by the High Father Superior’s voice. ‘What cause have you for this outrage, warrior! You violate a most holy rite.’

A voice rang out. ‘We seek the Lady of the Acoma!’

The Lady of the Acoma. Like a cold knife plunged into the pit of her stomach, the words cut through Mara’s soul. That one sentence forever changed her life. Her mind rebelled, screaming denial, but she willed herself to remain calm. Never would she shame her ancestors by a public display of grief. She controlled her voice as she slowly rose to her feet. ‘I am here, Keyoke.’

As one, the priests and priestesses watched the High Father Superior cross to stand before Mara. The embroidered symbols on his robes of office flashed fitfully as he beckoned to a priestess, who hastened to his side. Then he looked into Mara’s eyes and read the contained pain hidden there. ‘Daughter, it is clear Our Mistress of Wisdom has ordained another path for you. Go with her love and in her grace, Lady of the Acoma.’ He bowed slightly.

Mara returned his bow, then surrendered her head covering to the priestess. Oblivious to Ura’s sigh of envy, she turned at last to face the bearer of those tidings which had changed her life.

Just past the curtain, Keyoke, Force Commander of the Acoma, regarded his mistress with weary eyes. He was a battle-scarred old warrior, erect and proud despite forty years of loyal service. He stood poised to step to the girl’s side, provide a steadying arm, perhaps even shield her from public view should the strain prove too much.

Poor, ever-loyal Keyoke, Mara thought. This announcement had not come easily for him either. She would not disappoint him by shaming her family. Faced with tragedy, she maintained the manner and dignity required of the Lady of a great house.

Keyoke bowed as his mistress approached. Behind him stood the tall and taciturn Papewaio, his face as always an unreadable mask. The strongest warrior in the Acoma retinue, he served as both companion and body servant to Keyoke. He bowed and held aside the curtain for Mara as she swept past.

Mara heard both fall into step, one on each side, Papewaio one pace behind, correct in form to the last detail. Without words she led them from the inner temple, under the awning that covered the garden court separating the inner and outer temples. They entered the outer temple, passing between giant sandstone columns that rose to the ceiling. Down a long hall they marched, past magnificent frescos depicting tales of the goddess Lashima. Desperately attempting to divert the pain that threatened to overwhelm her, Mara remembered the story each picture represented: how the goddess outwitted Turakamu, the Red God, for the life of a child; how she stayed the wrath of Emperor Inchonlonganbula, saving the city of Migran from obliteration; how she taught the first scholar the secret of writing. Mara closed her eyes as they passed her favourite: how, disguised as a crone, Lashima decided the issue between the farmer and his wife. Mara turned her eyes from these images, for they belonged to a life now denied her.

All too soon she reached the outer doors. She paused a moment at the top of the worn marble stairs. The courtyard below held a half company of guards in the bright green armour of the Acoma. Several showed freshly bandaged wounds, but all came to attention and saluted, fist over heart, as their Lady came into view. Mara swallowed fear: if wounded soldiers stood escort duty, the fighting must have been brutal indeed. Many brave warriors had died. That the Acoma must show such a sign of weakness made Mara’s cheeks burn with anger. Grateful for the temple robe that hid the shaking in her knees, she descended the steps. A litter awaited her at the bottom. A dozen slaves stood silently by until the Lady of the Acoma settled inside. Then Papewaio and Keyoke assumed position, one on each side. On Keyoke’s command, the slaves grasped the poles and lifted the litter on to sweating shoulders. Veiled by the light, embroidered curtain on either side of the litter, Mara sat stiffly as the soldiers formed up before and after their mistress.

The litter swayed slightly as the slaves started towards the river, threading an efficient course through the throng who travelled the streets of the Holy City. They moved past carts pulled by sluggish, six-legged needra and were passed in turn by running messengers and trotting porters with bundles held aloft on shoulder or head, hurrying their loads for clients who paid a premium for swift delivery.

The noise and bustle of commerce beyond the gates jolted Mara afresh; within the shelter of the temple, the shock of Keyoke’s appearance had not fully registered. Now she battled to keep from spilling tears upon the cushions of the litter as understanding overwhelmed her. She wanted not to speak, as if silence could hide the truth. But she was Tsurani, and an Acoma. Cowardice would not change the past, nor forever stave off the future. She took a breath. Then, drawing aside the curtain so she could see Keyoke, she voiced what was never in doubt.

‘They are both dead.’

Keyoke nodded curtly, once. ‘Your father and brother were both ordered into a useless assault against a barbarian fortification. It was murder.’ His features remained impassive, but his voice betrayed bitterness as he walked at a brisk pace beside his mistress.

The litter jostled as the slaves avoided a wagon piled with jomach fruit. They turned down the street towards the landing by the river while Mara regarded her clenched hands. With focused concentration, she willed her fingers to open and relax. After a long silence she said, ‘Tell me what happened, Keyoke.’

‘When the snows on the barbarian world melted we were ordered out, to stand against a possible barbarian assault.’ Armour creaked as the elderly warrior squared his shoulders, fighting off remembered fatigue and loss, yet his voice stayed matter-of-fact. ‘Soldiers from the barbarian cities of Zun and LaMut were already in the field, earlier than expected. Our runners were dispatched to the Warlord, camped in the valley in the mountains the barbarians call the Grey Towers. In the Warlord’s absence, his Subcommander gave the order for your father to assault the barbarian position. We –’

Mara interrupted. ‘This Subcommander, he is of the Minwanabi, is he not?’

Keyoke’s weathered face showed a hint of approval as if silently saying, you’re keeping your wits despite grief. ‘Yes. The nephew of Lord Jingu of the Minwanabi, his dead brother’s only son, Tasaio.’ Mara’s eyes narrowed as he continued his narrative. ‘We were grossly outnumbered. Your father knew this – we all knew it – but your father kept honour. He followed orders without question. We attacked. The Subcommander promised to support the right flank, but his troops never materialized. Instead of a coordinated charge with ours, the Minwanabi warriors held their ground, as if preparing for counterattack. Tasaio ordered they should do so.

‘But just as we were overwhelmed by a counterattack, support arrived from the valley, elements of the forces under the banner of Omechkel and Chimiriko. They had no hint of the betrayal and fought bravely to get us out from under the hooves of the barbarians’ horses. The Minwanabi attacked at this time, as if to repulse the counterattack. They arrived just as the barbarians retreated. To any who had not been there from the start, it was simply a poor meeting with the barbarian enemy. But the Acoma know it was Minwanabi treachery.’

Mara’s eyes narrowed, and her lips tightened; for an instant Keyoke’s expression betrayed concern that the girl might shame her father’s memory by weeping before tradition permitted. But instead she spoke quietly, her voice controlled fury. ‘So my Lord of the Minwanabi seized the moment and arranged for my father’s death, despite our alliance within the War Party?’

Keyoke straightened his helm. ‘Indeed, my Lady. Jingu of the Minwanabi must have ordered Tasaio to change the Warlord’s instructions. Jingu moves boldly; he would have earned Tasaio the Warlord’s wrath and a dishonourable death had our army lost that position to the barbarians. But Almecho needs Minwanabi support in the conquest, and while he is angry with Jingu’s nephew, he keeps silent. Nothing was lost. To outward appearances, it was simply a standoff, no victor. But in the Game of the Council, the Minwanabi triumph over the Acoma.’ For the first time in her life, Mara heard a hint of emotion in Keyoke’s voice. Almost bitterly, he said, ‘Papewaio and I were spared by your father’s command. He ordered us to remain apart with this small company – and charged us to protect you should matters proceed as they have.’ Forcing his voice back to its usual brisk tone, he added, ‘My Lord Sezu knew he and your brother would likely not survive the day.’

Mara sank back against the cushions, her stomach in knots. Her head ached and she felt her chest tighten. She took a long, slow breath and glanced out the opposite side of the litter, to Papewaio, who marched with a studied lack of expression. ‘And what do you say, my brave Pape?’ she asked. ‘How shall we answer this murder visited upon our house?’

Papewaio absently scratched at the scar on his jaw with his left thumb, as he often did in times of stress. ‘Your will, my Lady.’

The manner of the First Strike Leader of the Acoma was outwardly easy, but Mara sensed he wished to be holding his spear and unsheathed sword. For a wild, angry instant Mara considered immediate vengeance. At her word, Papewaio would assault the Minwanabi lord in his own chamber, in the midst of his army. Although the warrior would count it as an honour to die in the effort, she shunted away the foolish impulse. Neither Papewaio nor any other wearing the Acoma green could get within half a day’s march of the Minwanabi lord. Besides, loyalty such as his was to be jealously guarded, never squandered.

Removed from the scrutiny of the priests, Keyoke studied Mara closely. She met his gaze and held it. She knew her expression was grim and her face drawn and chalky, but she also knew she had borne up well under the news. Keyoke’s gaze returned forward, as he awaited his mistress’s next question or command.

A man’s attention, even an old family retainer’s, caused Mara to take stock of herself, without illusions, being neither critical nor flattering. She was a fair-looking young woman, not pretty, especially when she wrinkled her brow in thought or frowned in worry. But her smile could make her striking – or so a boy had told her once – and she possessed a certain appealing quality, a spirited energy, that made her almost vivacious at times. She was slender and lithe in movement, and that trim body had caught the eye of more than one son of a neighbouring house. Now one of those sons would likely prove a necessary ally to stem the tide of political fortune that threatened to obliterate the Acoma. With her brown eyes half-closed, she considered the awesome responsibility thrust upon her. She realized, with a sinking feeling, that the commodities of womankind – beauty, wit, charm, allure – must all now be put to use in the cause of the Acoma, along with whatever native intelligence the gods had granted her. She fought down the fear that her gifts were insufficient for the task; then, before she knew it, she was recalling the faces of her father and brother. Grief rose up within her, but she forced it back deep. Sorrow must keep until later.

Softly Mara said, ‘We have much to talk of, Keyoke, but not here.’ In the press of city traffic, enemies might walk on every side, spies, assassins, or informants in disguise. Mara closed her eyes against the terrors of imagination and the real world both. ‘We shall speak when only ears loyal to the Acoma may overhear.’ Keyoke grunted acknowledgement. Mara silently thanked the gods that he had been spared. He was a rock, and she would need such as he at her side.

Exhausted, Mara settled back into the cushions. She must arise above grief to ponder. Her father’s most powerful enemy, Lord Jingu of the Minwanabi, had almost succeeded in gaining one of his life’s ambitions: the obliteration of the Acoma. The blood feud between the Acoma and Minwanabi had existed for generations, and while neither house had managed to gain the upper hand, from time to time one or the other had to struggle to protect itself. But now the Acoma had been gravely weakened, and the Minwanabi were at the height of their power, rivalling even the Warlord’s family in strength. Jingu was already served by vassals, first among them the Lord of the Kehotara, whose power equalled that of Mara’s father. And as the star of the Minwanabi rose higher, more would ally with him.

For a long while Mara lay behind the fluttering curtains, to all appearances asleep. Her situation was bitterly clear. All that remained between the Lord of the Minwanabi and his goal was herself, a young girl who had been but ten chimes from becoming a sister of Lashima. That realization left a taste in her mouth like ash. Now, if she were to survive long enough to regain family honour, she must consider her resources and plot and plan, and enter the Game of the Council; and somehow she must find a way to thwart the will of the Lord of one of the Five Great Families of the Empire of Tsuranuanni.

Mara blinked and forced herself awake. She had dozed fitfully while the litter travelled the busy streets of Kentosani, the Holy City, her mind seeking relief from the stress of the day. Now the litter rocked gently as it was lowered to the docks.

Mara peeked through the curtains, too numb to find pleasure in the bustle of the throngs upon the dockside. When she had first arrived in the Holy City, she had been enthralled by the multi-coloured diversity found in the crowd, with people from every corner of the Empire upon every hand. The simple sight of household barges from cities up and down the river Gagajin had delighted her. Bedecked with banners, they rocked at their moorings like proudly plumed birds amid the barnyard fowl as busy commercial barges and traders’ boats scurried about them. Everything, the sights, the sounds, the smells, had been so different from her father’s estates – her estates now, she corrected herself. Torn by that recognition, Mara hardly noticed the slaves who toiled in the glaring sun, their sweating, near-naked bodies dusted with grime as they loaded bundled goods aboard the river barges. This time she did not blush as she had when she had first passed this way in the company of the sisters of Lashima. Male nudity had been nothing new to her; as a child she had played near the soldiers’ commons while the men bathed and for years she had swum with her brother and friends in the lake above the needra meadow. But seeing naked men after she had renounced the world of flesh seemed somehow to have made a difference. Being commanded to look away by the attending sister of Lashima had made her want to peek all the more. That day she had to will herself not to stare at the lean, muscled bodies.

But today the bodies of the slaves failed to fascinate, as did the cries of the beggars who called down the blessings of the gods on any who chose to share a coin with the less fortunate. Mara ignored the rivermen, who sauntered by with the swaggering gait of those who spent their lives upon the water, secretly contemptuous of land dwellers, their voices loud and edged with rough humour. Everything seemed less colourful, less vivid, less captivating, as she looked through eyes suddenly older, less given to seeing with wonder and awe. Now every sunlit façade cast a dark shadow. And in those shadows enemies plotted.

Mara left her litter quickly. Despite the white robe of a novice of Lashima, she bore herself with the dignity expected of the Lady of the Acoma. She kept her eyes forward as she moved towards the barge that would take her downriver, to Sulan-Qu. Papewaio cleared a path for her, roughly shoving common workers aside. Other soldiers moved nearby, brightly coloured guardians who conducted their masters from the barges to the city. Keyoke kept a wary eye upon them as he hovered near Mara’s side while they crossed the dock.

As her officers ushered her up the gangplank, Mara wished for a dark, quiet place in which to confront her own sorrow. But the instant she set foot upon the deck, the barge master hustled to meet her. His short red and purple robe seemed jarringly bright after the sombre dress of the priests and sisters in the convent. Jade trinkets clinked on his wrists as he bowed obsequiously and offered his illustrious passenger the finest accommodation his humble barge permitted, a pile of cushions under a central canopy, hung round by gauzy curtains. Mara allowed the fawning to continue until she had been seated, courtesy requiring such lest the man unduly lose face. Once settled, she let silence inform the barge master his presence was no longer required. Finding an indifferent audience to his babble, the man let fall the thin curtain, leaving Mara a tiny bit of privacy at last. Keyoke and Papewaio sat opposite, while the household guards surrounded the canopy, their usual alertness underscored by a grim note of battle-ready tension.

Seeming to gaze at the swirling water, Mara said, ‘Keyoke, where is my father’s … my own barge? And my maids?’

The old warrior said, ‘The Acoma barge is at the dock in Sulan-Qu, my Lady. I judged a night encounter with soldiers of the Minwanabi or their allies less likely if we used a public barge. The chance of surviving witnesses might help discourage assault by enemies disguised as bandits. And should difficulty visit us, I feared your maids might prove a hindrance.’ Keyoke’s eyes scanned the docks while he spoke. ‘This craft will tie up at night with other barges, so we will never be upon the river alone.’

Mara nodded, letting her eyes close a long second. Softly she said, ‘Very well.’ She had wished for privacy, something impossible to find on this public barge, but Keyoke’s concerns were well founded.

Lord Jingu might sacrifice an entire company of soldiers to destroy the last of the Acoma, certain he could throw enough men at Mara’s guards to overwhelm them. But he would only do so if he could assure himself of success, then feign ignorance of the act before the other Lords of the High Council. Everyone who played the Game of the Council would deduce who had authored such slaughter, but the forms must always be observed. One escaped traveller, one Minwanabi guard recognized, one chance remark overheard by a poleman on a nearby barge, and Jingu would be undone. To have his part in such a venal ambush revealed publicly would lose him much prestige in the council, perhaps signalling to one of his ‘loyal’ allies that he was losing control. Then he could have as much to fear from his friends as from his enemies. Such was the nature of the Game of the Council. Keyoke’s choice of conveyance might prove as much a deterrent to treachery as a hundred more men-at-arms.

The barge master’s voice cut the air as he shouted for the slaves to cast off the dock lines. A thud and a bump, and suddenly the barge was moving, swinging away from the dock into the sluggish swirl of the current. Mara lay back, judging it acceptable now to outwardly relax. Slaves poled the barge along, their thin, sun-browned bodies moving in time, coordinated by a simple chant.

‘Keep her to the middle,’ sang out the tillerman.

‘Don’t hit the shore,’ answered the poleman.

The chant settled into a rhythm, and the tillerman began to add simple lyrics, all in tempo. ‘I know an ugly woman!’ he shouted.

‘Don’t hit the shore!’

‘Her tongue cuts like a knife!’

‘Don’t hit the shore!’

‘Got drunk one summer’s evening!’

‘Don’t hit the shore!’

‘And took her for my wife!’

The silly song soothed Mara and she let her thoughts drift. Her father had argued long and hotly against her taking vows. Now, when apologies were no longer possible, Mara bitterly regretted how close she had come to open defiance; her father had relented only because his love for his only daughter had been greater than his desire for a suitable political marriage. Their parting had been stormy. Lord Sezu of the Acoma could be like a harulth – the giant predator most feared by herdsmen and hunters – in full battle frenzy when facing his enemies, but he had never been able to deny his daughter, no matter how unreasonable her demands. While never as comfortable with her as he had been with her brother, still he had indulged her all her life, and only her nurse, Nacoya, had taken firm rein over her childhood.

Mara closed her eyes. The barge afforded a small measure of security, and she could now hide in the dark shelter of sleep; those outside the curtains of this tiny pavilion would only think her fleeing the boredom of a lengthy river journey. But rest proved elusive as memories returned of the brother she had loved like the breath in her lungs, Lanokota of the flashing dark eyes and ready smile for his adoring little sister. Lano who ran faster than the warriors in his father’s house, and who won in the summer games at Sulan-Qu three years in a row, a feat unmatched since. Lano always had time for Mara, even showing her how to wrestle – bringing down her nurse Nacoya’s wrath for involving a girl in such an unladylike pastime. And always Lano had a stupid joke – usually dirty – to tell his little sister to make her laugh and blush. Had she not chosen the contemplative life, Mara knew any suitor would have been measured against her brother … Lano, whose merry laughter would no more echo through the night as they sat in the hall sharing supper. Even their father, stern in all ways, would smile, unable to resist his son’s infectious humour. While Mara had respected and admired her father, she had loved her brother, and now grief came sweeping over her.

Mara forced her emotions back. This was not the place; she must not mourn until later. Turning to the practical, she said to Keyoke, ‘Were my father’s and brother’s bodies recovered?’

With a bitter note, Keyoke said, ‘No, my Lady, they were not.’

Mara bit her lip. There would be no ashes to inter in the sacred grove. Instead she must choose a relic of her father’s and brother’s, one favourite possession of each, to bury beside the sacred natami – the rock that contained the Acoma family’s soul – that their spirits could find their way back to Acoma ground, to find peace beside their ancestors until the Wheel of Life turned anew. Mara closed her eyes again, half from emotional fatigue, half to deny tears. Memories jarred her to consciousness as she unsuccessfully tried to rest. Then, after some hours, the rocking of the barge, the singing of the tillerman, and the answering chant of the slaves became familiar. Her mind and body fell into an answering rhythm and she relaxed. The warmth of the day and the quietness of the river at last conspired to lull Mara into a deep sleep.

The barge docked at Sulan-Qu under the topaz light of daybreak. Mist rose in coils off the river, while shops and stalls by the waterfront opened screened shutters in preparation for market. Keyoke acted swiftly to disembark Mara’s litter while the streets were still free of the choking press of commerce; soon carts and porters, shoppers and beggars would throng the commercial boulevards. In scant minutes the slaves were ready. Still clad in the white robes of Lashima’s sisterhood – crumpled from six days’ use – Mara climbed wearily into her litter. She settled back against cushions stylized with her family’s symbol, the shatra bird, embroidered into the material, and realized how much she dreaded her return home. She could not imagine the airy spaces of the great house empty of Lano’s boisterous voice, or the floor mats in the study uncluttered with the scrolls left by her father when he wearied of reading reports. Mara smiled faintly, recalling her father’s distaste for business, despite the fact he was skilled at it. He preferred matters of warfare, the games, and politics, but she remembered his saying that everything required money, and commerce must never be neglected.

Mara allowed herself an almost audible sigh as the litter was hoisted. She wished the curtains provided more privacy as she endured the gazes of peasants and workers upon the streets at first light. From atop vegetable carts and behind booths where goods were being arrayed, they watched the great lady and her retinue sweep by. Worn from constantly guarding her appearance, Mara endured the jostling trip through streets that quickly became crowded. She lapsed into brooding, outwardly alert, but inwardly oblivious to the usually diverting panorama of the city.

Screens on the galleries overhead were withdrawn as merchants displayed wares above the buyers. When haggling ended, the agreed price was pulled up in baskets, then the goods lowered. Licensed prostitutes were still asleep, so every fifth or sixth gallery remained shuttered.

Mara smiled slightly, remembering the first time she had seen the ladies of the Reed Life. The prostitutes showed themselves upon the galleries as they had for generations, robes left in provocative disarray as they fanned themselves in the ever-present city heat. All the women had been beautiful, their faces painted with lovely colours and their hair bound up in regal style. Even the skimpy robes were of the costliest weave, with fine embroidery. Mara had voiced a six-year-old girl’s delight at the image. She had then announced to all within earshot that when she grew up she would be just like the ladies in the galleries. This was the only time in her life she had seen her father rendered speechless. Lano had teased her about the incident until the morning she left for the temple. Now his playful jibes would embarrass her no further.

Saddened nearly to tears, Mara turned from memory. She sought diversion outside her litter, where clever hawkers sold wares from wheelbarrows at corners, beggars accosted passersby with tales of misery, jugglers offered antics, and merchants presented rare, beautiful silk as they passed. But all failed to shield her mind from pain.

The market fell behind and they left the city. Beyond the walls of Sulan-Qu, cultivated fields stretched towards a line of bluish mountains on the horizon; the Kyamaka range was not so rugged or so high as the great High Wall to the north, but the valleys remained wild enough to shelter bandits and outlaws.

The road to Mara’s estates led through a swamp that resisted all attempts to drain it. Here her bearers muttered complaints as they were plagued by insects. A word from Keyoke brought silence.

Then the road passed through a stand of ngaggi trees, their large lower branches a green-blue canopy of shade. The travellers moved on into hillier lands, crossing over brightly painted bridges, as the streams that fed the swamp continually interrupted every road built by man. They came to a prayer gate, a brightly painted arch erected by some man of wealth as thanks to the gods for a blessing granted. As they passed under the arch, each traveller generated a silent prayer of thanks and received a small blessing in return. And as the prayer arch fell behind, Mara considered she would need all the grace the gods were willing to grant in the days to come, if the Acoma were to survive.

The party left the highway, turning towards their final destination. Shatra birds foraged in the thyza paddies, eating insects and grubs, stooped over like old men. Because the flocks helped ensure a good harvest, the silly-looking creatures were considered a sign of good luck. So the Acoma had counted them, making the shatra symbol the centrepiece of their house crest. Mara found no humour in the familiar sight of the shatra birds, with their stilt legs and ever-moving pointed ears, finding instead deep apprehension, for the birds and workers signalled she had reached Acoma lands.

The bearers picked up stride. Oh, how Mara wished they would slacken pace, or turn around and carry her elsewhere. But her arrival had been noticed by the workers who gathered faggots in the woodlands between the fields and the meadow near the great house. Some shouted or waved as they walked stooped under bundles of wood loaded on their backs and secured with a strap across their foreheads. There was a warmth in their greeting, and despite the cause of her return they deserved more than aloofness from their new mistress.

Mara pulled herself erect, smiling slightly and nodding. Around her spread her estates, last seen with the expectation she would never return. The hedges, the trimmed fields, and the neat outbuildings that housed the workers were unchanged. But then, she thought, her absence had been less than a year.

The litter passed the needra meadows. The midday air was rent by the herds’ plaintive lowing and the ‘hut-huthut’ cry of the herdsmen as they waved goading sticks and moved the animals towards the pens where they would be examined for parasites. Mara regarded the cows as they grazed, the sun making their grey hides look tawny. A few lifted blunt snouts as stocky bull calves feinted charges, then scampered away on six stumpy legs to shelter behind their mothers. To Mara it seemed some asked when Lano would return to play his wild tricks on the ill-tempered breeding bulls. The pain of her losses increased the closer she came to home. Mara put on a brave face as the litter bearers turned along the wide, tree-lined lane that led to the heart of the estate.

Ahead lay the large central house, constructed of beams and paper-thin screens, slid back to open the interior to any breezes in the midday heat. Mara felt her breath catch. No dogs sprawled among the akasi flowers, tongues lolling and tails wagging as they waited for the Lord of the Acoma to return. In his absence they were always kennelled; now that absence was permanent. Yet home, desolate and empty though it seemed without the presence of loved ones, meant privacy. Soon Mara could retire to the sacred grove and loose the sorrow she had pent up through seven weary days.

As the litter and retinue passed a barracks house, the soldiers of her home garrison fell into formation along her line of travel. Their armour was polished, their weapons and trappings faultlessly neat, yet beside Keyoke’s and Papewaio’s, only one other officer’s plume was in evidence. Mara felt a chill stab at her heart and glanced at Keyoke. ‘Why so few warriors, Force Commander? Where are the others?’

Keyoke kept his eyes forward, ignoring the dust that clung to his lacquered armour and the sweat that dripped beneath his helm. Stiffly he said, ‘Those who were capable returned, Lady.’

Mara closed her eyes, unable to disguise her shock. Keyoke’s simple statement indicated that almost two thousand soldiers had died beside her father and brother. Many of them had been retainers with years of faithful service, some having stood guard at Mara’s crib side. Most had followed fathers and grandfathers into Acoma service.

Numbed and speechless, Mara counted those soldiers standing in formation and added their numbers to those who had travelled as bodyguards. Thirty-seven warriors remained in her service, a pitiful fraction of the garrison her father had once commanded. Of the twenty-five hundred warriors to wear Acoma green, five hundred were dedicated to guarding outlying Acoma holdings in distant cities and provinces. Three hundred had already been lost beyond the rift in the war against the barbarians before this last campaign. Now, where two thousand soldiers had served at the height of Acoma power, the heart of the estate was protected by fewer than fifty men. Mara shook her head in sorrow. Many women besides herself mourned losses beyond the rift. Despair filled her heart as she realized the Acoma forces were too few to withstand any assault, even an attack by bandits, should a bold band raid from the mountains. But Mara also knew why Keyoke had placed the estate at risk to bring such a large portion – twenty-four out of thirty-seven – of the surviving warriors to guard her. Any spies of the Minwanabi must not be allowed to discover just how weak the Acoma were. Hopelessness settled over her like a smothering blanket.

‘Why didn’t you tell me sooner, Keyoke?’ But only silence answered. By that Mara knew. Her faithful Force Commander had feared that such news might break her if delivered all at once. And that could not be permitted. Too many Acoma soldiers had died for her to simply give up to despair. If hopelessness overwhelmed her, their sacrifice in the name of Acoma honour became a mockery, their death a waste. Thrust headlong into the Game of the Council, Mara needed every shred of wit and cunning she possessed to avoid the snares of intrigue that lay in wait for her inexperienced feet. The treachery visited upon her house would not end until, unschooled and alone, she had defeated the Lord of the Minwanabi and his minions.

The slaves halted in the dooryard. Mara drew a shaking breath. Head high, she forced herself to step from the litter and enter the scrolled arches of the portico that lined the perimeter of the house. Mara waited while Keyoke dismissed the litter and gave the orders to her escort. Then, as the last soldier saluted, she turned and met the bow of the hadonra, her estate manager. The man was new to his post, his squint-eyed countenance unfamiliar to Mara. But beside him stood the tiny, wizened presence of Nacoya, the nurse who had raised Mara from childhood. Other servants waited beyond.

The impact of the change struck Mara once again. For the first time in her life, she could not fly into the comfort of the ancient woman’s arms. As Lady of the Acoma, she must nod formally and walk past, leaving Nacoya and the hadonra to follow her up the wooden steps into the shady dimness of the great house. Today she must bear up and pretend not to notice the painful reflection of her own sorrow in Nacoya’s eyes. Mara bit her lip slightly, then stopped herself. That nervous habit had brought Nacoya’s scolding on many occasions. Instead the girl took a breath, and entered the house of her father. The missing echoes of his footfalls upon the polished wooden floor filled her with loneliness.

‘Lady?’

Mara halted, clenched hands hidden in the crumpled white of her robe. ‘What is it?’

The hadonra spoke again. ‘Welcome home, my Lady,’ he added in formal greeting. ‘I am Jican, Lady.’

Softly Mara said, ‘What has become of Sotamu?’

Jican glanced down. ‘He wasted in grief, my Lady, following his Lord into death.’

Mara could only nod once and resume her progress to her quarters. She was not surprised to learn that the old hadonra had refused to eat or drink after Lord Sezu’s death. Since he was an elderly man, it must have taken only a few days for him to die. Absently she wondered who had presumed to appoint Jican hadonra in his stead. As she turned to follow one of the large halls that flanked a central garden, Nacoya said, ‘My Lady, your quarters are across the garden.’

Mara barely managed another nod. Her personal belongings would have been moved to her father’s suite, the largest in the building.

She moved woodenly, passing the length of the square garden that stood at the heart of every Tsurani great house. The carved wooden grille work that enclosed the balcony walkways above, the flower beds, and the fountain under the trees in the courtyard seemed both familiar and inescapably strange after the stone architecture of the temples. Mara continued until she stood before the door to her father’s quarters. Painted upon the screen was a battle scene, a legendary struggle won by the Acoma over another, long-forgotten, enemy. The hadonra, Jican, slid aside the door.

Mara faltered a moment. The jolt of seeing her own belongings in her father’s room nearly overcame her control, as if this room itself had somehow betrayed her. And with that odd distress came the memory: the last time she had stepped over this threshold had been on the night she argued with her father. Though she was usually an even-tempered and obedient child, that one time her temper had matched his.

Mara moved woodenly forward. She stepped onto the slightly raised dais, sank down onto the cushions, and waved away the maids who waited upon her needs. Keyoke, Nacoya, and Jican then entered and bowed formally before her. Papewaio remained at the door, guarding the entrance from the garden.

In hoarse tones Mara said, ‘I wish to rest. The journey was tiring. Leave now.’ The maids left the room at once, but the three retainers all hesitated. Mara said, ‘What is it?’

Nacoya answered, ‘There is much to be done – much that may not wait, Mara-anni.’

The use of the diminutive of her name was intended in kindness, but to Mara it became a symbol of all she had lost. She bit her lip as the hadonra said, ‘My Lady, many things have gone neglected since … your father’s death. Many decisions must be made soon.’

Keyoke nodded. ‘Lady, your upbringing is lacking for one who must rule a great house. You must learn those things we taught Lanokota.’

Miserable with memories of the rage she had exchanged with her father the night before she had left, Mara was stung by the reminder that her brother was no longer heir. Almost pleading, she said, ‘Not now. Not yet.’

Nacoya said, ‘Child, you must not fail your name. You –’

Mara’s voice rose, thick with emotions held too long in check. ‘I said not yet! I have not observed a time of mourning! I will hear you after I have been to the sacred grove.’ The last was said with a draining away of anger, as if the little flash was all the energy she could muster. ‘Please,’ she added softly.

Ready to retire, Jican stepped back, absently plucking at his livery. He glanced at Keyoke and Nacoya, yet both of them held their ground. The Force Commander said, ‘Lady, you must listen. Soon our enemies will move to destroy us. The Lord of the Minwanabi and the Lord of the Anasati both think House Acoma defeated. Neither should know you did not take final vows for a few days more, but we cannot be sure of that. Spies may already have carried word that you have returned; if so, your enemies are even now plotting to finish this house once and finally. Responsibilities cannot be put off. You must master a great deal in a short time if there is to be any hope of survival for the Acoma. The name and honour of your family are now in your hands.’

Mara tilted her chin in a manner unchanged from her childhood. She whispered, ‘Leave me alone.’

Nacoya stepped to the dais. ‘Child, listen to Keyoke. Our enemies are made bold by our loss, and you’ve no time for self-indulgence. The education you once received to become the wife of some other household’s son is inadequate for a Ruling Lady.’

Mara’s voice rose, tension making the blood sing in her ears. ‘I did not ask to be Ruling Lady!’ Dangerously close to tears, she used anger to keep from breaking. ‘Until a week ago, I was to be a sister of Lashima, all I wished for in this life! If the Acoma honour must rely upon me for revenge against the Minwanabi, if I need counsel and training, all will wait until I have visited the sacred grove and done reverence to the memories of the slain!’

Keyoke glanced at Nacoya, who nodded. The young Lady of the Acoma was near breaking, and must be deferred to, but the old nurse was ready to deal with even that. She said, ‘All is prepared for you in the grove. I have presumed to choose your father’s ceremonial sword to recall his spirit, and Lanokota’s manhood robe to recall his.’ Keyoke motioned to where the two objects lay atop a richly embroidered cushion.

Seeing the sword her father wore at festivals and the robe presented to her brother during his ceremony of manhood was more than the exhausted, grief-stricken girl could bear. With tears rising, she said, ‘Leave me!’

The three hesitated, though to disobey the Lady of the Acoma was to risk punishment even unto death. The hadonra was first to turn and quit his mistress’s quarters. Keyoke followed, but as Nacoya turned to go, she repeated, ‘Child, all is ready in the grove.’ Then slowly she slid the great door closed.

Alone at last, Mara allowed the tears to stream down her cheeks. Yet she held her sobbing in check as she rose and picked up the cushion with the sword and robe upon it.

The ceremony of mourning was a private thing; only family might enter the contemplation glade. But under more normal circumstances, a stately procession of servants and retainers would have marched with surviving family members as far as the blocking hedge before the entrance. Instead a single figure emerged from the rear door of her quarters. Mara carried the cushion gently, her white robe wrinkled and dirty where the hem dragged in the dust.

Even deaf and blind she would have remembered the way. Her feet knew the path, down to the last stone fisted into the gnarled ulo tree root beside the ceremonial gate. The thick hedge that surrounded the grove shielded it from observation. Only the Acoma might walk here, save a priest of Chochocan when consecrating the grove or the gardener who tended the shrubs and flowers. A blocking hedge faced the gate, preventing anyone outside from peering within.

Mara entered and hurried to the centre of the grove. There, amid a sculptured collection of sweet-blossomed fruit trees, a tiny stream flowed through the sacred pool. The rippled surface reflected the blue-green of the sky through curtains of overhanging branches. At water’s edge a large rock sat embedded in the soil, worn smooth by ages of exposure to the elements; the shatra bird of the Acoma was once carved deeply on its surface, but now the crest was barely visible. This was the family’s natami, the sacred rock that embodied the spirit of the Acoma. Should the day come when the Acoma were forced to flee these lands, this one most revered possession would be carried away and all who bore the name would die protecting it. For should the natami fall into the hands of any other, the family would be no more. Mara glanced at the far hedge. The three natami taken by Acoma ancestors were interred under a slab, inverted so their carved crests would never see sunlight again. Mara’s forebears had obliterated three families in the Game of the Council. Now her own stood in peril of joining them.

Next to the stone a hole had been dug, the damp soil piled to one side. Mara placed the cushion with her father’s sword and her brother’s robe within. With bare hands she pushed the earth back into the hole, patting it down, unmindful as she soiled her white robe.

Then she sat back on her heels, caught by the sudden compulsion to laugh. A strange, detached giddiness washed over her and she felt alarm. Despite this being the appointed place, tears and pain so long held in check seemed unwilling to come.

She took a breath and stifled the laughter. Her mind flashed images and she felt hot flushes rush up her breasts, throat, and cheeks. The ceremony must continue, despite her strange feelings.

Beside the pool rested a small vial, a faintly smoking brazier, a tiny dagger, and a clean white gown. Mara lifted the vial and removed the stopper. She poured fragrant oils upon the pool, sending momentary shimmers of fractured light across its surface. Softly she said, ‘Rest, my father. Rest, my brother. Come to your home soil and sleep with our ancestors.’

She laid the vial aside and with a jerk ripped open the bodice of her robe. Despite the heat, chill bumps roughened her small breasts as the breeze struck suddenly exposed, damp skin. She reached up and again ripped her gown, as ancient traditions were followed. With the second tear she cried out, a halfhearted sound, little better than a whimper. Tradition demanded the show of loss before her ancestors.

Again she tore her robe, ripping it from her left shoulder so it hung half to her waist. But the shout that followed held more anger at her loss than sorrow. With her left hand she reached up and tore her gown from her right shoulder. This time her sob was full-throated as pain erupted from the pit of her stomach.

Traditions whose origins were lost in time at last triggered a release. All the torment she had held in check came forth, rushing up from her groin through her stomach and chest to issue from her mouth as a scream. The sound of a wounded animal rang in the glade as Mara gave full vent to her anger, revulsion, torment and loss.

Shrieking with sorrow, nearly blinded with tears, she plunged her hand into the almost extinguished brazier. Ignoring the pain of the few hot cinders there, she smeared the ashes across her breasts and down her exposed stomach. This symbolized that her heart was ashes, and again sobs racked her body as her mind sought final release from the horror left by the murder of her father, brother, and hundreds of loyal warriors. Her left hand shot out and grabbed dirt from beside the natami. She smeared the damp soil in her hair and struck her head with her fist. She was one with Acoma soil, and to that soil she would return, as would the spirits of the slain.

Now she struck her thigh with her fist, chanting the words of mourning, almost unintelligible through her crying. Rocking back and forth upon her knees, she wailed in sorrow.

Then she seized the tiny metal dagger, a family heirloom of immense value, used only for this ceremony over the ages. She drew the blade from its sheath and cut herself across the left arm, the hot pain a counterpoint to the sick ache in her chest.

She held the small wound over the pool, letting drops of blood fall to mix with the water, as tradition dictated. Again she tore at her robe, ripping all but a few tatters from her body. Naked but for a loincloth, she cast the rags away with a strangled cry. Pulling her hair, forcing pain to cleanse her grief, she chanted ancient words, calling her ancestors to witness her bereavement. Then she threw herself across the fresh soil over the place of interment and rested her head upon the family natami.

With the ceremony now complete, Mara’s grief flowed like the water streaming from the pool, carrying her tears and blood to the river, thence to the distant sea. As mourning eased away pain, the ceremony would eventually cleanse her, but now was the moment of private grief when tears and weeping brought no shame. And Mara descended into grief as wave after wave of sorrow issued from the deepest reservoir within her soul.

A sound intruded, a rustling of leaves as if someone moved through the tree branches above her. Caught up in grief, Mara barely noticed, even when a dark figure dropped to land next to her. Before she could open her eyes, powerful fingers yanked on her hair. Mara’s head snapped back. Jolted by a terrible current of fear, she struggled, half glimpsing a man in black robes behind her. Then a blow to the face stunned her. Her hair was released and a cord was passed over her head. Instinctively she grabbed at it. Her fingers tangled in the loop that should have killed her in seconds, but as the man tightened the garrotte, her palm prevented the knot in the centre from crushing her windpipe. Still she couldn’t breathe. Her attempt to shout for aid was stifled. She tried to roll away, but her assailant jerked upon the cord and held her firmly in check. A wrestler’s kick learned from her brother earned her a mocking half-laugh, half-grunt. Despite her skill, Mara was no match for the assassin.

The cord tightened, cutting painfully into her hand and neck. Mara gasped for breath, but none came and her lungs burned. Struggling like a fish on a gill line, she felt the man haul her upright. Only her awkward grip on the cord kept her neck from breaking. Mara’s ears sang from the pounding of her own blood within. She clawed helplessly with her free hand. Her fingers tangled in cloth. She yanked, but was too weak to overbalance the man. Through a roar like surf, she heard the man’s laboured breathing as he lifted her off the ground. Then, defeated by lack of air, her spirit fell downwards into darkness.

• Chapter Two • Evaluations (#ulink_14c8be77-1765-5b9d-aebc-7f0a403003d9)

Mara felt wetness upon her face.

Through the confusion of returning senses, she realized Papewaio was gently cradling her head in the crook of his arm as he moistened her face with a damp rag. Mara opened her mouth to speak, but her throat constricted. She coughed, then swallowed hard against the ache of injured neck muscles. She blinked, and struggled to organize her thoughts; but she knew only that her neck and throat hurt terribly and the sky above looked splendid beyond belief, its blue-green depths appearing to fade into the infinite. Then she moved her right hand; pain shot across her palm, jolting her to full memory.

Almost inaudibly she said, ‘The assassin?’

Papewaio inclined his head toward something sprawled by the reflecting pool. ‘Dead.’

Mara turned to look, ignoring the discomfort of her injuries. The corpse of the killer lay on one side, the fingers of one hand trailing in water discoloured with blood. He was short, reed-thin, of almost delicate build, and clad simply in a black robe and calf-length trousers. His hood and veil had been pulled aside, revealing a smooth, boyish face marked by a blue tattoo upon his left cheek – a hamoi flower stylized to six concentric circles of wavy lines. Both hands were dyed red to the wrists. Mara shuddered, still stinging from the violence of those hands upon her flesh.

Papewaio helped her to her feet. He tossed away the rag, torn from her rent garment, and handed her the white robe intended for the end of the ceremony. Mara clothed herself, ignoring the stains her injured hands made upon the delicately embroidered material. At her nod, Papewaio escorted her from the glade.

Mara followed the path, its familiarity no longer a comfort. The cruel bite of the stranger’s cord had forced her to recognize that her enemies could reach even to the heart of the Acoma estates. The security of her childhood was forever gone. The dark hedges surrounding the glade now seemed a haven for assassins, and the shade beneath the wide limbs of the ulo tree carried a chill. Rubbing the bruised and bloody flesh of her right hand, Mara restrained an impulse to bolt in panic. Though terrified like a thyza bird at the shadow of a golden killwing as it circles above, she stepped through the ceremonial gate with some vestige of the decorum expected of the Ruling Lady of a great house.

Nacoya and Keyoke waited just outside, with the estate gardener and two of his assistants. None spoke but Keyoke, who said only, ‘What?’

Papewaio replied with grim brevity. ‘As you thought. An assassin waited. Hamoi tong.’

Nacoya extended her arms, gathering Mara into hands that had soothed her hurts since childhood, yet for the first time Mara found little reassurance. With a voice still croaking from her near strangulation, she said, ‘Hamoi tong, Keyoke?’

‘The Red Hands of the Flower Brotherhood, my Lady. Hired murderers of no clan, fanatics who believe to kill or be killed is to be sanctified by Turakamu, that death is the only prayer the god will hear. When they accept a commission they vow to kill their victims or die in the attempt.’ He paused, while the gardener made an instinctive sign of protection: the Red God was feared. With a cynical note, Keyoke observed, ‘Yet many in power understand that the Brotherhood will offer their unique prayer only when the tong has been paid a rich fee.’ His voice fell to almost a mutter as he added, ‘And the Hamoi are very accommodating as to whose soul shall offer that prayer to Turakamu.’

‘Why had I not been told of these before?’

‘They are not part of the normal worship of Turakamu, mistress. It is not the sort of thing fathers speak of to daughters who are not heirs.’ Nacoya’s voice implied reprimand.

Though it was now too late for recriminations, Mara said, ‘I begin to see what you meant about needing to discuss many things right away.’ Expecting to be led away, Mara began to turn toward her quarters. But the old woman held her; too shaken to question, Mara obeyed the cue to remain.

Papewaio stepped away from the others, then dropped to one knee in the grass. The shadow of the ceremonial gate darkened his face, utterly hiding his expression as he drew his sword and reversed it, offering the weapon hilt first to Mara. ‘Mistress, I beg leave to take my life with the blade.’

For a long moment Mara stared uncomprehendingly. ‘What are you asking?’

‘I have trespassed into the Acoma contemplation glade, my Lady.’

Overshadowed by the assassination attempt, the enormity of Papewaio’s act had not registered upon Mara until this instant. He had entered the glade to save her, despite the knowledge that such a transgression would earn him a death sentence without appeal.

As Mara seemed unable to respond, Keyoke tried delicately to elaborate on Pape’s appeal. ‘You ordered Jican, Nacoya, and myself not to accompany you to the glade, Lady. Papewaio was not mentioned. He hid himself near the ceremonial gate; at the sound of a struggle he sent the gardener to fetch us, then entered.’

The Acoma Force Commander granted his companion a rare display of affection; for an instant the corners of his mouth turned up, as if he acknowledged victory after a difficult battle. Then his hint of a smile vanished. ‘Each one of us knew such an attempt upon you was only a matter of time. It is unfortunate that the assassin chose this place; Pape knew the price of entering the glade.’

Keyoke’s message to Mara was clear: Papewaio had affronted Mara’s ancestors by entering the glade, earning himself a death sentence. But not to enter would have entailed a fate far worse. Had the last Acoma died, every man and woman Papewaio counted a friend would have become houseless persons, little better than slaves or outlaws. No warrior could do other than Papewaio had done; his life was pledged to Acoma honour. Keyoke was telling Mara that Pape had earned a warrior’s death, upon the blade, for choosing life for his mistress and all those he loved at the cost of his own life. But the thought of the staunch warrior dying as a result of her own naïveté was too much for Mara. Reflexively she said, ‘No.’

Assuming this to mean he was denied the right to die without shame, Papewaio bent his head. Black hair veiled his eyes as he flipped his sword, neatly, with no tremor in his hands, and drove the blade into the earth at his Lady’s feet. Openly regretful, the gardener signalled his two assistants. Carrying rope, they hurried forward to Papewaio’s side. One began to bind Papewaio’s hands behind him while the other tossed a long coil of rope over a stout tree branch.

For a moment Mara was without comprehension, then understanding struck her: Papewaio was being readied for the meanest death, hanging, a form of execution reserved for criminals and slaves. Mara shook her head and raised her voice. ‘Stop!’

Everyone ceased moving. The assistant gardeners paused with their hands half-raised, looking first to the head gardener, then to Nacoya and Keyoke, then to their mistress. They were clearly reluctant to carry out this duty, and confusion over their Lady’s wishes greatly increased their discomfort.

Nacoya said, ‘Child, it is the law.’

Gripped by an urge to scream at them all, Mara shut her eyes. The stress, her mourning, the assault, and now this rush to execute Papewaio for an act caused by her irresponsible behaviour came close to overwhelming her. Careful not to burst into tears, Mara answered firmly. ‘No … I haven’t decided.’ She looked from face to impassive face and added, ‘You will all wait until I do. Pape, take up your sword.’

Her command was a blatant flouting of tradition; Papewaio obeyed in silence. To the gardener, who stood fidgeting uneasily, she said, ‘Remove the assassin’s body from the glade.’ With a sudden vicious urge to strike at something, she added, ‘Strip it and hang it from a tree beside the road as a warning to any spies who may be near. Then cleanse the natami and drain the pool; both have been defiled. When all is returned to order, send word to the priests of Chochocan to come and reconsecrate the grove.’

Though all watched with unsettled eyes, Mara turned her back. Nacoya roused first. With a sharp click of her tongue, she escorted her young mistress into the cool quiet of the house. Papewaio and Keyoke looked on with troubled thoughts, while the gardener hurried off to obey his mistress’s commands.

The two assistant gardeners coiled the ropes, exchanging glances. The ill luck of the Acoma had not ended with the father and the son, so it seemed. Mara’s reign as Lady of the Acoma might indeed prove brief, for her enemies would not rest while she learned the complex subtleties of the Game of the Council. Still, the assistant gardeners seemed to silently agree, such matters were in the hands of the gods, and the humble in life were always carried along in the currents of the mighty as they rose and fell. None could say such a fate was cruel or unjust. It simply was.

The moment the Lady of the Acoma reached the solitude of her quarters, Nacoya took charge. She directed servants who bustled with subdued efficiency to make their mistress comfortable. They prepared a scented bath while Mara rested on cushions, absently fingering the finely embroidered shatra birds that symbolized her house. One who did not know her would have thought her stillness the result of trauma and grief; but Nacoya observed the focused intensity of the girl’s dark eyes and was not fooled. Tense, angry, and determined, Mara already strove to assess the far-reaching political implications of the attack upon her person. She endured the ministrations of her maids without her usual restlessness, silent while the servants bathed her and dressed her wounds. A compress of herbs was bound around her bruised and lacerated right hand. Nacoya hovered anxiously by while Mara received a vigorous rub by two elderly women who had ministered to Lord Sezu in the same manner. Their old fingers were surprisingly strong; knots of muscular tension were sought out and gradually kneaded away. Afterwards, clothed in clean robes, Mara still felt tired, but the attentions of the old women had eased away nervous exhaustion.

Nacoya brought chocha, steaming in a fine porcelain cup. Mara sat before a low stone table and sipped the bitter drink, wincing slightly as the liquid aggravated her bruised throat. In the grove she had been too shocked by the attack to feel much beyond a short burst of panic and fear. Now she was surprised to discover herself too wrung out to register any sort of reaction. The slanting light of afternoon brightened the paper screens over the windows, as it had throughout her girlhood. Far off, she could hear the whistles of the herdsmen in the needra meadows, and near at hand, Jican’s voice reprimanding a house slave for clumsiness. Mara closed her eyes, almost able to imagine the soft scratch of the quill pen her father had used to draft instructions to distant subordinates; but Minwanabi treachery had ended such memories forever. Reluctantly Mara acknowledged the staid presence of Nacoya.

The old nurse seated herself on the other side of the table. Her movements were slow, her features careworn. The delicate seashell ornaments that pinned her braided hair were fastened slightly crooked, as reaching upwards to fix the pin correctly became more difficult with age. Although only a servant, Nacoya was well versed in the arts and subtlety of the Game of the Council. She had served at the right hand of Lord Sezu’s lady for years, then raised his daughter after the wife’s death in childbirth. The old nurse had been like a mother to Mara. Sharply aware that the old nurse was waiting for some comment, the girl said, ‘I have made some grave errors, Nacoya.’

The nurse returned a curt nod. ‘Yes, child. Had you granted time for preparation, the gardener would have inspected the grove immediately before you entered. He might have discovered the assassin, or been killed, but his disappearance would have alerted Keyoke, who could have had warriors surround the glade. The assassin would have been forced to come out or starve to death. Had the Hamoi murderer fled the gardener’s approach and been lurking outside, your soldiers would have found his hiding place.’ The nurse’s hands tightened in her lap, and her tone turned harsh. ‘Indeed, your enemy expected you to make mistakes … as you did.’

Mara accepted the reproof, her eyes following the lazy curls of steam that rose from her cup of chocha. ‘But the one who sent the killer erred as much as I.’

‘True.’ Nacoya squinted, forcing farsighted vision to focus more clearly upon her mistress. ‘He chose to deal the Acoma a triple dishonour by killing you in your family’s sacred grove, and not honourably with the blade, but by strangulation, as if you were a criminal or slave to die in shame!’

Mara said, ‘But as a woman –’

‘You are Ruling Lady,’ snapped Nacoya. Lacquered bracelets clashed as she thumped fists on her knee in a timeworn gesture of disapproval. ‘From the moment you assumed supremacy in this house, child, you became as a man, with every right and privilege of rulership. You wield the powers your father did as Lord of the Acoma. And for this reason, your death by the strangler’s cord would have visited as much shame on your family as if your father or brother had died in such fashion.’

Mara bit her lip, nodded, and dared another sip of her chocha. ‘The third shame?’

‘The Hamoi dog certainly intended to steal the Acoma natami, forever ending your family’s name. Without clan or honour, your soldiers would have become grey warriors, outcasts living in the wilds. All of your servants would have finished their lives as slaves.’ Nacoya ended in bitterness. ‘Our Lord of the Minwanabi is arrogant.’

Mara placed her chocha cup neatly in the centre of the table. ‘So you think Jingu responsible?’

‘The man is drunk with his own power. He stands second only to the Warlord in the High Council now. Should fate remove Almecho from his throne of white and gold, a Minwanabi successor would assuredly follow. The only other enemy of your father’s who would wish your ruin is the Lord of the Anasati. But he is far too clever to attempt such a shameful assault – so badly done. Had he sent the Hamoi murderer, his instructions would have been simple: your death by any means. A poison dart would have struck from hiding, or a quick blade between the ribs, then quickly away to carry word of your certain death.’

Nacoya nodded with finality, as if discussion had confirmed her convictions. ‘No, our Lord of the Minwanabi may be the most powerful man in the High Council, but he is like an enraged harulth, smashing down trees to trample a gazen.’ She raised spread fingers, framing the size of the timid little animal she had named. ‘He inherited his position from a powerful father, and he has strong allies. The Lord of the Minwanabi is cunning, not intelligent.

‘The Lord of the Anasati is both cunning and intelligent, one to be feared.’ Nacoya made a weaving motion with her hand. ‘He slithers like the relli in the swamp, silent, stealthy, and he strikes without warning. This murder was marked as if the Minwanabi lord had handed the assassin a warrant for your death with his own family chop affixed to the bottom.’ Nacoya’s eyes narrowed in thought. ‘That he knows you’re back this quickly speaks well of his spies. We assumed he would not find out you were Ruling Lady for a few more days. For the Hamoi to have been sent so soon shows he knew you had not taken your vows from the instant Keyoke led you from the temple.’ She shook her head in self-reproach. ‘We should have assumed as much.’

Mara considered Nacoya’s counsel, while her cup of chocha cooled slowly on the table. Aware of her new responsibilities as never before, she accepted that unpleasant subjects could no longer be put off. Though dark hair curled girlishly around her cheeks, and the robe with its ornate collar seemed too big for her, she straightened with the resolve of a ruler. ‘I may seem like a gazen to the Lord of the Minwanabi, but now he has taught this eater of flowers to grow teeth for meat. Send for Keyoke and Papewaio.’

Her command roused the runner, a small, sandal-clad slave boy chosen for his fleetness; he sprang from his post by her doorway to carry word. The warriors arrived with little delay; both had anticipated her summons. Keyoke wore his ceremonial helm, the feather plumes denoting his office brushing the lintel of the doorway as he entered. Bare-headed, but nearly as tall, Papewaio followed his commander inside. He moved with the same grace and strength that had enabled him to strike down a killer only hours before; his manner betrayed not a single hint of concern over his unresolved fate. Struck by his proud carriage, and his more than usually impassive face, Mara felt the judgment she must complete was suddenly beyond her resources.

Her distress was in no way evident as the warriors knelt formally before her table. The green plumes of Keyoke’s helm trembled in the air, close enough for Mara to touch. She repressed a shiver and gestured for the men to sit. Her maidservant offered hot chocha from the pot, but only Keyoke accepted. Papewaio shook his head once, as though he trusted his bearing better than his voice.