Harold Wilson

Peter Hennessy

Ben Pimlott

Reissued with a new foreword to mark the centenary of Harold Wilson’s birth, Ben Pimlott's classic biography combines scholarship and observation to illuminate the life and career of one of Britain's most controversial post-war statesmen.Harold Wilson is one of the most enigmatic personalities of recent British history. He held office as Prime Minister for longer than any other Labour leader, and longer than any other premier in peacetime apart from Mrs Thatcher. His success at winning General Elections – four in all – has so far not been matched. His grasp of economic policy was better than that of any other Prime Minister, and he enjoyed a high reputation among foreign leaders. Yet, in retrospect, he seems a master tactician rather than a strategist – and he is regarded today with more curiosity than respect, when he is not treated with contempt.

BEN PIMLOTT

Harold Wilson

Copyright (#ulink_30f1536e-004f-5dc5-82f6-752a2ff51269)

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com (http://www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins in 1992

This edition first published by William Collins in 2016

Copyright © Ben Pimlott 1992

Foreword copyright © Peter Hennessy 2016

Ben Pimlott has the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

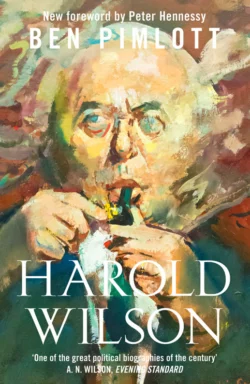

Cover image: Harold Wilson, c. 1974 (oil on canvas), Spear, Ruskin (1911–90)/National Portrait Gallery, London, UK/© Stefano Baldini/Bridgeman Images

Illustrations: p. 40 (#ulink_67387039-4a62-55af-9b48-5dcf3336d609), courtesy of the Wilson family. All cartoons courtesy of the Centre for the Study of Cartoons and Caricature, University of Kent, Canterbury: p. 97, Junior minister, 1945; p. 195, ‘We’re washing our dirty linen in public’ (Vicky) (Daily Mirror); p. 230, Blackpool, 1959 (Vicky) (Solo Syndication); p. 358, ‘When he is worried he walks up and down and hums’ (Vicky) (Solo Syndication); p. 538, ‘It’s not easy’ (Garland) (© Telegraph plc); p. 599, Follow my Leadership (Garland) (© Telegraph plc).

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008182618

Ebook Edition © March 2016 ISBN: 9780008182625

Version: 2016-03-10

Dedication (#ulink_ad745850-d957-51ae-a975-d350cb5c95b0)

FOR

DANIEL, NATHANIEL AND SETH

Contents

Cover (#u7c01325c-7ff1-502d-b7fd-ee1b73f19057)

Title Page (#ub6e22893-c70f-5491-9e2a-6443e6c0a16b)

Copyright (#ulink_2bab04d2-dd45-5916-b586-3ec8f607168c)

Dedication (#ulink_26f57a8e-4246-5419-aba7-5241cf2932be)

Foreword by Peter Hennessy (#ulink_f56a4c4a-da2d-5e3b-93f1-967210ab8d7f)

Preface (#ulink_fa449008-275c-532b-90eb-459ee01b1161)

Part One (#ulink_2bfa361a-464e-5777-aab1-8a598d0742ec)

1 Roots (#ulink_92435c66-fa1e-5e4b-a3ab-2d4378789dc4)

2 Be Prepared (#ulink_d284d781-51ca-5edc-be8c-5c344611a651)

3 Jesus (#ulink_d7c170b7-5dbf-509e-abdb-aedf1b1fe195)

4 Beveridge Boy (#ulink_26b8d91e-626b-54f7-8d89-63a15efa8a01)

5 Mines

6 Vodka

7 Bonfire

8 Three Wise Men

9 Nye’s Little Dog

10 The Dog Bites

11 The Man Who Changed His Mind

12 Spherical Thing

13 Leader

14 Heat

Part Two

15 Kitchen

16 Fetish

17 Quick Kill

18 Super-Harold

19 Dog Days

20 Personal Diplomat

21 Aching Tooth

22 Style

23 Strife

24 Carnival

25 Indiarubber

26 Second Coming

27 Slag

28 Birthday Present

29 Vendetta

30 Tricks

31 Ghost

Notes

Sources and Select Bibliography

Index

By the Same Author

About the Author

About the Publisher

Foreword (#ulink_0a8cdb10-2bdc-5fc1-ba35-dc02a4c396af)

by Peter Hennessy (#ulink_0a8cdb10-2bdc-5fc1-ba35-dc02a4c396af)

‘In the cycle to which we belong we can see only a fraction of the curve.’

So wrote the statesman and novelist John Buchan of The Thirty-Nine Steps fame.

Harold Wilson dominated the political curve during my late adolescence and early manhood and, later, my first years as a journalist. To borrow Winston Churchill’s line on Joseph Chamberlain, Wilson made the political weather

for the great bulk of his thirteen years as leader of the Labour Party between 1963 and 1976, during which he won four of the five general elections he contested and occupied 10 Downing Street from October 1964 to June 1970 and from March 1974 until April 1976.

The UK and its politics have travelled a huge arc on Buchan’s curve since Harold Wilson gave way to an older man, Jim Callaghan, as leader of the Labour Party and Prime Minister in the spring of 1976. Ben Pimlott’s fine biography described that curve superbly up to 1992. It was an instant classic and has become an enduring one from one of Britain’s master biographers of the post-war years, and it is a great sadness to me that Ben is not here to update it to mark the centenary of Wilson’s birth.

How do the politics and policies of the years of the Wilsonian ascendancy strike one now? Excessive hindsight can be a historical blight; but fresh perspectives shaped by elapsed time are a stimulating part of the historian’s tradecraft. For example, there are in the middle of the second decade of the twenty-first century plentiful resonances from all phases of the Wilson years, between his succeeding Hugh Gaitskell as Labour Party leader in 1963 and his final handing in of his seals of office to the Queen in 1976.

Merely to list some of them tells a story:

• The internal condition of Labour; the tussles between its competing philosophies and factions; the party’s relationships with the trade unions and constituency activists.

• Europe and the referendum question; Britain’s place in the wider world; of punching heavier than its weight

militarily and diplomatically, plus the deployment of soft power, with the often neuralgic sub-theme of The Bomb and remaining a nuclear weapons state always a lurking question.

• Employment, productivity, the imbalance between finance, services and manufacturing; the state’s role in shaping an industrial strategy and sustaining the country’s scientific and technological base; plus the UK’s thinking above its weight in terms of research and the universities.

This inventory is by no means complete, and how it would intrigue Wilson to revisit it as he absorbed the current scene through the clouds of his trademark pipe smoke were he still with us.

In his absence, let us linger on a few key Wilsonian themes. First, Labour Party management. Wilson was a supple and serpentine party manager. He was a quantum physicist among politicians in his understanding of what it took to keep its volatile subatomic particles together. For these gifts he was often derided – dismissed as a tactician who would all too readily sacrifice long-term strategy to the imperative of the immediate and the pressing. But now, at a time when the Corbyn-led Labour Party is demonstrating fortissimo its most powerful centrifugal tendencies, to the detriment of its indispensable constitutional function of providing sustained and effective opposition to the government, Harold-the-party-manager seems positively lustrous – a reminder that at least a semblance of party coherence is more often than not a first-order matter for Labour. The party’s relations with the unions and the wider Labour movement are integral to this.

Wilson knew how to juggle with and arbitrate between the political philosophies that perpetually compete for the soul of the Labour Party: social democracy; democratic socialism; and a variety of hard-left factions. This skill was matched by his sense of party structure: the constituency membership base and its affiliated trade unionists; the relationship with the Trades Union Congress; the Parliamentary Labour Party; the Shadow Cabinet and the Party’s National Executive Committee and its annual conference. His word power, his sharp wit and his plethora of personal relationships enabled him to pursue his ambition, with considerable success, of turning Labour into the natural party of government, rather than operating in ‘a Conservative country that sometimes votes Labour’, as Reggie Maudling, a former Tory Chancellor of the Exchequer, liked to put it.

For all his striking achievement in the course of a single summer in 2015 in capturing the base and the leadership apex of the Labour Party (with considerable support from the leaders of the fewer yet larger conglomerate trade unions), Jeremy Corbyn is simply not in the Wilson class. Crucially for Corbyn, his wit, his style, his policies simply do not run in the crucial middle, including the bulk of the PLP. In terms of jumping and clearing the Labour Party’s internal fences, Wilson was a Grand National winner; Corbyn has yet to win a local point-to-point. The gap between them as parliamentary performers in the House of Commons similarly yawns chasm-like. Wilson was born to excel at Prime Minister’s Questions.

Their pre-leadership formation and experience also make for the starkest of contrasts. Wilson, like the classic scholarship boy he was, had prepared meticulously for the Labour leadership and ultimately for the premiership. He knew the Civil Service intimately as a temporary official in the War Cabinet Office,

and rose rapidly through the junior ranks of the Attlee government to become President of the Board of Trade in 1947, at thirty-one the youngest member of a Cabinet since Pitt. A seemingly principled resignation in April 1951, alongside Nye Bevan and John Freeman, in response to health service cuts and the cost of rearmament when the outbreak of conflict in Korea chilled the Cold War still further, opened his credentials to the left of the party in a way his previous technocratic prowess had not.

In opposition Wilson shadowed nearly all the big portfolios, including the Treasury and Foreign Affairs, chaired the premier select committee in the Commons (Public Accounts) and taught himself to be a sharp and often bitingly funny speaker at the despatch box and on the platform alike (he had been rather pedestrian at the Board of Trade). He retained his technocratic edge and, as a trained economist and statistician, was numerate as well as literate. By the time of Gaitskell’s sudden and unexpected death, Wilson had all the gifts and fitted to perfection the mould of the gritty grammar school meritocrat – part of the rising generation that would sweep away the last vestiges of amateurism in Whitehall committee rooms and industrial boardrooms alike.

Wilson, however, never acquired the full trust or affection of many of the right of the Labour Party (several of whom thought he took careerism and opportunism to new heights), but he was admired, respected and feared, especially by his opponents. He was a stunningly effective Leader of the Opposition between February 1963 and October 1964. First Harold Macmillan, in his last, no longer ‘Supermac’ phase, and then the aristocratic Alec Douglas-Home were almost out of central casting as foils for Wilson.

Jeremy Corbyn’s CV on assuming the leadership of the Labour Party was entirely lacking in job experience. His apprenticeship placement had been on Labour’s outer-left rim, as narrow and rigid (if principled) as Wilson’s had been wide, fluid and adaptive. He neither planned for nor expected the party leadership. He was without ministerial or Opposition front-bench experience. In the summer of 2015 it merely seemed Corbyn’s turn to be the traditional tethered goat that the Labour hard left offers up for mainstream leadership candidates to savage. Far from being the sacrificial quadruped, he turned out – to his and everyone else’s surprise – to be the lion of the contest. There could not be a greater contrast of formations than between those of Wilson and Corbyn, this intriguing and unproven figure with carnivorous views and herbivorous ways. Jeremy Corbyn may turn out to be a more effective Labour leader than many expect, but his long-term mission, one suspects, will not include a Wilsonian appetite for capturing the centre of the British electorate and turning Labour into the natural party of government. For that to happen, the fulcrum of British politics would have to shift several degrees to the left.

Wilson, however, did set out in the early months of 1963 to offer himself and his party as a transforming instrument to his country. Like Corbyn’s – though in a very different way – his was a transformative pitch, a blueprint (to use a noun fashionable at the time) for a New Britain. If office fell into his and his party’s hands it would not be a status quo or a ‘better yesterday’ (to adapt a phrase of Ralf Dahrendorf’s

) premiership or administration. His stall, which he laid out with great verve throughout the election year of 1964, was both brilliantly simple and fiendishly difficult – to project the British economy onto a new and sustained trajectory of science, technology and export-led growth substantially higher than achieved so far in the years since 1945. Wilson set himself a very high bar against which he and his ministry would be judged, and the brilliance of his language, the grittiness of his style and the seemingly comprehensive approach to ‘purposive’ (a favourite adjective) government and planning plainly persuaded a sizeable slice of the electorate as to its achievability. At the October 1964 general election a Conservative majority of nearly a hundred in the House of Commons was converted to a Labour one of six.

It was a dazzling performance and, for all the frustrations and underachievement that followed, it still has a tingle to it today that echoes in the latest approaches to growth, science and technology and the planning of long-term investment that are the currency of industrial and infrastructural politics in 2016. If Wilson were taking a centenarian’s look at British politics today he might allow himself a dash of I-told-you-soing.

In what I still regard as the signature speech of Harold Wilson’s long political life, he found a theme at the Labour Party Conference in Scarborough on 1 October 1963 that served not only to unite all shades of Labour opinion but also caught the wider appetite for a modernity that would replace privilege with meritocracy. We learned from Ben Pimlott’s biography when it was first published that Wilson did not finally decide on this theme until the night before he delivered his conference peroration, and that he did so at the prompting of his Political Secretary, Marcia Williams, now Lady Falkender.

Wilson’s speech built upon his analysis of the deeper causes of Britain’s relative economic slippage by providing an outline of the attitudes and the ‘new industries which would make us once again one of the foremost industrial nations of the world’. As Ben wrote, ‘The climax was a declaration that enraptured his audience, made a profound impact on the press, and was frequently to be quoted – at first in his favour and then against him, in later years’:

In all our plans for the future, we are re-defining and we are restating our Socialism in terms of the scientific revolution. But that revolution cannot become a reality unless we are prepared to make far-reaching changes in economic and social attitudes which permeate our whole system of society.

The Britain that is going to be forged in the white heat of this revolution will be no place for restrictive practices or for outdated methods on either side of industry … In the Cabinet room and the board room alike those charged with the control of our affairs must be ready to think and to speak the language of our scientific age.

From that autumn day on the Yorkshire coast, any political word-association game would twin ‘white heat’ with ‘Harold Wilson’.

As a country we are still searching for that Holy Grail of full employment, high productivity, export-led prowess sustained by the technical ingenuity and the applied little grey cells of a well-trained, flexible, agile and highly motivated world-class workforce. Today, in, for example, Michael Heseltine’s highly influential report on growth for the Cameron coalition government, No Stone Unturned,

the ingredients of such a strategy would be different, stressing a far greater charge of private sector input within a public/private mix and no trace of the revived or new state enterprises that animated Wilson’s view from the Scarborough Conference Hall. But the clarion call to embrace new technology and the rekindling of once great industrial powerhouses has more than a dash of Scarborough about it.

The failure to make manifest the promise of Scarborough has blighted Wilson’s reputation from the late 1960s until today, I think now (though once I did not) to probably an excessive degree. It’s not just that Britain or ‘England’, as Disraeli called it, is ‘a very difficult country to move … and one in which there is more disappointment to be looked for than success!’.

The very nature of the state did not lend itself to becoming the production engineer of such a transformation. We simply did not possess what the economist Chalmers Johnson later called the kind of ‘developmental state’ required.

In my judgement, Wilson knew this when he rose to bathe his Scarborough audience in the warmth of the ‘white heat’ of the longed-for technological revolution. He said as much in an agenda-setting speech he called ‘The New Britain’ in Birmingham Town Hall on 19 January 1964: ‘We must reconstruct our institutions … This means a new sense of drive in the higher direction of our national affairs; it means changes in our departmental structure to reflect the scientific and technological realities of the new age.’

For a fundamental change in the structure of Whitehall’s economic and industrial ministries was also central to the plan. In October 1964 he split the Treasury, leaving it a ministry of finance and public spending and placing responsibility for growth and planning in a new Department of Economic Affairs under his mercurial deputy, George Brown, whom he had defeated in the race to succeed Gaitskell. A second new department, the Ministry of Technology, was created as the ‘white heat’ department and placed in the charge of the left-wing leader of the Transport and General Workers’ Union, Frank Cousins. The hope was that these institutional innovations would fuel a take-off for the British economy as laid out in the French-style National Plan unveiled by Brown in September 1965.

A foreword is not the place for an autopsy on the failure of Wilson’s grand design. Ben’s pages carefully and vividly anatomise how it played out, not least how the anticipated ‘creative tension’ between Jim Callaghan’s Treasury and George Brown’s DEA produced more tension than creativity, especially when the showdown came between keeping the pound at $2.80 on the exchanges rather than devaluing and dashing for growth during the economic crisis of July 1966, when the balance of payments (the great economic totem of the age) worsened on the back of a protracted seamen’s strike and the government resorted to deflationary measures and an incomes policy.

Wilson still sought new ways of stimulating the British economy to rise to a higher and more productive trajectory after the setback of July 1966 and the inevitable – but still humiliating – devaluation of the pound in November 1967 from $2.80 to $2.40. With his favourite minister, the dazzling Barbara Castle, at the Department of Employment and Productivity (the old Ministry of Labour by another name), Wilson sought to curb the power of the unions and the rash of ‘wildcat’ strikes that were such a familiar Sixties phenomenon with a set of proposals in a white paper they called In Place of Strife. This went down in flames in June 1969, battered by hostile ordnance hurled by the National Executive Committee, the wider Labour movement and, finally, a Cabinet prepared to settle for a feeble ‘solemn and binding’ undertaking from the TUC to spare no effort in curbing industrial action. The ‘white heat’ speech of 1963 and the promise of 1964 were tarnished for ever.

They were also unfulfilled. As Sir Alec Cairncross, Head of the Government Economic Service from 1964 to 1969, put it in his audit of the British economy since 1945, ‘the target assumed’ by the 1965 National Plan was ‘an average 3.8% rate of growth compared with an average rate of only 2.9% from 1950 to 1964 and a rate actually achieved between 1964 and 1970 of only 2.6%’.

There was no leap to growth; no new trajectory for the British economy.

Wilson did not reach the benchmark he had drawn for himself and his governments. In pursuit of his grail of growth, Wilson also cut against his own Commonwealth instincts and turned to what at that stage was the unarguable economic success story of the Common Market of the six original members of the European Economic Community led by West Germany and France. He and Brown (moved to the Foreign Office from the DEA after the 1966 crisis) determined to persuade sceptical Cabinet colleagues of the EEC route to economic salvation. They set off for a round of conversations across the European capitals, declaring that they would not take ‘No’ for an answer as Harold Macmillan had been forced to by President Charles de Gaulle of France in January 1963, following the first UK application. De Gaulle rather liked Brown calling him ‘Charlie’ when the Harold and George show passed through Paris – but he said ‘No’ again anyway.

At heart Wilson was a Commonwealth and an Atlanticist man, not a European man. A strong believer in the NATO alliance (very much a creation of Ernest Bevin, Foreign Secretary in the Attlee administration in which Wilson was so proud to have served). Wilson is remembered fondly by today’s Labour left for setting his face against sending British troops to fight in the Vietnam War despite intense pressure from President Lyndon Johnson in Washington, who repeatedly said that even a platoon of Black Watch bagpipers would do. Wilson’s argument was partly that the UK was doing its duty in Asia fighting (and winning) the ‘Confrontation’ with Indonesia.

His handling of the perennial question of Labour and The Bomb was also masterly. Even though it was initially Labour’s bomb (Attlee took the decision to procure a UK atomic weapon in a Cabinet committee in January 1947; though the first test took place under a restored Churchill premiership in October 1952), the H-bomb era brought the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament into existence in 1958, which, briefly, captured the Labour Party Conference in 1960–61. For a time as Leader of the Opposition, Wilson gave the left the impression that though he was a multilateral disarmer, he did not believe Britain should accept the high level of dependence on the United States implicit in the purchase of submarine-launched Polaris missiles in the deal Macmillan struck with Kennedy at Nassau in December 1962. Labour’s manifesto for the 1964 general election, Let’s Go with Labour for the New Britain, said of the new system: ‘it will not be independent, it will not be British and it will not deter’ and pledged ‘the renegotiation of the Nassau Agreement’.

Yet, in office, he persuaded successive Cabinet committees and finally the full Cabinet that Polaris should be purchased for the Royal Navy, whose submarine service would operate four boats to ensure that at least one was at sea at all times – so-called ‘continuous at-sea deterrence’, which has been maintained from 14 June 1969 to today, ever since the Navy took over the strategic deterrent role from the ‘V’ bombers of the Royal Air Force.

Once more there are resonances for the present era of Labour leadership. Jeremy Corbyn, currently Vice-President of CND, has been a unilateral disarmer all his political life. His shadow Foreign Secretary, Hilary Benn, and his shadow Defence Secretary, Maria Eagle (at the time of writing), are adherents of the still current Labour policy of replacing the Trident missile-carrying Vanguard-class submarines with sufficient so-called ‘Successor’ boats to sustain continuous at-sea deterrence into the 2050s. Yet the nuclear policy with which Labour will fight the 2020 general election is far from clear given its leader’s connections (he has already made plain he would never authorise its use

) and the party’s current defence review jointly led by Maria Eagle and the anti-nuclear Ken Livingstone. The names may have changed but the nature and line-ups of this debate would be deeply familiar to Wilson.

So would another nerve-stretching element in the 2016 political season – Europe and the referendum. Vernon Bogdanor has made the very shrewd observation that Harold Wilson is one of the very few British prime ministers who has not, in one way or another, been eaten up by the European Question (despite the failure of that second EEC application) because of the way he handled the 1975 referendum on whether the UK should leave the EEC or remain, just two and a half years after acceding to it in January 1973. Bogdanor believes that this was ‘perhaps Wilson’s greatest triumph’,

a bold claim that has much in it, especially as he also described Wilson’s position on the EEC in the early 1970s as ‘unheroic’. Professor Bogdanor recalled that when Roy Jenkins, then Deputy Leader of the Labour Party, resigned from the Shadow Cabinet in 1972, after Labour promised a referendum on Common Market membership if returned to power, with others following,

Wilson told the Shadow Cabinet that while they had been indulging their consciences, it had been left to him to wade through s**t [to keep the Labour Party together]. Yet Bernard Donoughue, head of Wilson’s Policy Unit after 1974, was surely right to say that while Heath had taken British Establishment into Europe,

it was Wilson who brought in the British people.

A justifiable claim given the two-thirds-to-one-third vote in 1975 to stay in. But, as Professor Bogdanor noted, in the run-up to the coming remain/leave referendum in 2016 or 2017, ‘the British establishment remains firmly attached to Europe, even though the people remain full of doubts’.

The European question has been a near-perpetual of the UK’s national political conversation since Jean Monnet turned up almost out of the blue in London from Paris in May 1950 bearing his and Robert Schuman’s plan for a Coal and Steel Community.

It has been a particularly vexing element in our political biorhythms ever since, not least because it cannot be cast in the traditional left–right mould that normally shapes our party political competition.

Gazing wider than Europe, how does Harold Wilson fit the standard model of British politics since he entered the House of Commons in 1945? First of all, what is the ‘standard model’? In my judgement, it’s this: post-war UK electoral competitions have seen a jostling for pole position between liberal capitalism (in my view, the best instrument for innovation and economic growth so far discovered) and social democracy (the best mechanism so far created for redistribution and a measure of social justice). The voting public tends to wish for a judicious mix of each, and the job of Parliament and Whitehall is to attempt to achieve this by reconciling and blending these two philosophies. Occasionally, the electorate votes for a sharp dose of one rather than the other.

Early Wilson benefited from a ‘sharp dose’ phase if you take the general elections of 1964 and March 1966 (when Labour’s majority shot up to ninety-seven) together. It was, along with 1945 and, perhaps, 1997, one of the shining opportunities for radical centre-leftist policies in the UK. In June 1970 when, to near universal surprise, Wilson lost to Ted Heath, who was propelled into Downing Street by a Conservative majority of forty-four, it appeared the electorate had plumped for a shot of liberal capitalism (if the Tory manifesto A Better Tomorrow22 was to be believed). But the Heath U-turns, in the face of unemployment nudging a million people (a shocking statistic for the first fifteen or twenty years after the war), rather belied the free-market impulses of the 1970 prospectus.

The general election of February 1974, which Heath called on the back of the second miners’ strike inside two years, did not produce a shining hour for either of the competing political philosophies. Heath went to the country in a mood of ‘Who governs?’, and the electorate replied ‘Not sure’ twice, with Wilson taking office at the head of a minority government in March 1974 and with the slimmest of overall majorities in October 1974. Though his last administration tried to reach a new deal with the trade unions (the ‘social contract’) and offered a mildly interventionist industrial strategy, it was a time for coping, for getting by rather than for white – or any other – heat. With inflation around 25 per cent and the balance of payments reeling from a quadrupling of world oil prices following the 1973 Yom Kippur War, Wilson’s extraordinary array of political gifts was almost entirely devoted to holding the line through yet another incomes policy (which is why it is easy to forget just how skilfully he played his party and the country in the run-up to the 1975 referendum on Europe).

I have concentrated in this foreword on the special selling points Wilson displayed before the electorate in the promising glow of his first leadership of the Opposition and his early days as Prime Minister, as well as the extraordinary feat of party and wider political management he exhibited in 1975 (‘and people say I have no sense of strategy’, he said to his Principal Private Secretary, Ken Stowe, once the result was in

). But rereading Ben’s biography brings back just how relentlessly demanding the job of prime minister is. The crises are endless and Pimlott’s pages crackle with Wilson-the-crisis-manager. There was the perpetual problem of holding the thin red line of the sterling exchange rate in the 1964–70 government, when the seemingly constant balance of payments problems placed, as soon as they seriously deteriorated, instant pressure on the pound as the world’s second reserve currency after the US dollar in that age of Fixed exchange rates From November 1965 there was the running sore of Rhodesia after the Smith government unilaterally declared independence, presenting Wilson in both his Downing Street spells with one of the most stretching problems created by the withdrawal from Empire. And from 1968–69 a recrudescence of the Troubles in Northern Ireland was another great absorber of time and political nervous energy. And all the while, throughout his premiership, the ever-present perils of the Cold War lurked.

It is not surprising, therefore, that when he finally announced he was standing down, just days after his sixtieth birthday, he was worn out – if still chirpy in his pawkier moments – having sat almost continually on Labour’s front bench since the late summer of 1945. His longevity at or near the top of his party, his temperament, his gifts, his cockiness combined with social edginess – the sheer variety of Harolds he could put on display according to need or taste – made him the richest of characters for the biographer’s art. And in Pimlott on Wilson, subject and biographer were supremely well met.

Rereading his Harold Wilson serves only to remind us what a huge loss Ben Pimlott was to the historians’ trade and to political commentary. Tracing the Buchanite curves of contemporary British history as we travel them is so much harder without Ben. ‘What would Ben have made of this?’ is a thought that still crosses my mind when an event breaks or a political shift becomes apparent, as, for example, the weekend in September 2015 when Jeremy Corbyn won the Labour leadership race. But, above all, what would Ben Pimlott have made of the Wilson legacy in the centenary year of Harold’s birth? It is a matter of great regret – personal and professional – that this question must go unanswered.

Peter Hennessy, FBA,

Attlee Professor of Contemporary British History,

Queen Mary, University of London.

South Ronaldsay, Walthamstow and Westminster.

December–January 2015–16

Preface (#ulink_fa2b6eec-553b-5f4c-b8cd-c88f3d0b3d4f)

In the old days, writing the life of a public figure was frequently part of a process of canonization. Only after the subject was respectably dead would it be attempted, and then by arrangement between the executors and a suitable admirer, with the implicit purpose of enhancing the reputation of the deceased. A customary part of the ritual was for the author to declare at the beginning of the book that the co-operation of the family had been provided unconditionally, and that no pressure had been exerted whatsoever. Such a work was known as the ‘official’ or ‘authorized’ biography.

This book is neither official nor authorized, but it would be untrue to say that I have not been under any pressure while writing it. Pressure – from Lord Wilson’s former supporters and opponents in politics, from Whitehall and Fleet Street confidants and critics, and from his personal friends and enemies – has been unremitting. At the same time, it has always been courteous, usually charming and often – unless I was very careful – beguiling. Indeed, as a way of getting to know and understand my subject, it has been invaluable, as much for the appreciation of the feelings which he and the politics of his time aroused, as for the details of the arguments that were put to me.

I have a great many debts. The first is to the Wilsons who have been unfailingly kind and helpful. In particular, I have greatly benefited from conversations with Lord and Lady Wilson, and Robin Wilson. I am also most grateful to them for family papers, photographs and other documents.

Several people have helped with the research. I would especially like to thank Anne Baker, who investigated a number of collections of private papers on my behalf with the greatest sensitivity and professional skill. I am also grateful to Andrew Thomas, who conducted interviews in Huddersfield and Huyton, and Gerard Daly, who examined Labour Party papers at the Labour Museum in Manchester. Among the many archivists and librarians who responded to my queries and were generous with their time, I should like to thank, in particular, Stephen Bird, formerly at the Labour Party Library in Walworth Road and now at the National Museum of Labour History; Dr Angela Raspin, at the British Library of Political and Economic Science; Helen Langley, at the Bodleian Library, Oxford; Christine Woodland, at the Modern Records Centre at Warwick University; Dr Correlli Barnett at Churchill College, Cambridge; Caroline Dalton at New College, D.A. Rees at Jesus College and Christine Ritchie at University College, Oxford; and Ruth Winstone, editor of the Tony Benn Diaries. I am grateful to the large number of people who helped me by correspondence or on the telephone. For sending me documentary material, I should like to thank Michael Crick, Francis Wheen, Sir Alec Cairncross, Lord Young of Dartington, Lord Jay, David Edgerton, Mervyn Jones and Ron Hayward. I am most grateful to Lord Jenkins for allowing me to see a manuscript copy of his autobiography, before it was published, and to Tony Benn, for letting me rummage around in his basement archive.

I am grateful to the following for permission to quote copyright material: Jonathan Cape (B. Pimlott (ed.), The Political Diary of Hugh Dalton; P.M. Williams (ed.), The Diary of Hugh Gaitskell), Hamish Hamilton Ltd (J. Morgan (ed.), The Diaries of a Cabinet Minister, 3 Vols.; Richard Crossman, The Backbench Diaries of Richard Crossman), David Higham Associates (Barbara Castle, The Castle Diaries, 2 Vols.), Hutchinson (Mary Wilson, New Poems; Tony Benn, Diaries), Michael Joseph (H. Wilson, Purpose in Politics, and Memoirs: the Making of a Prime Minister), Macmillan Publishers Ltd (Roy Jenkins, A Life at the Centre), and Manchester University Press (M. Dupree (ed.), Lancashire and Whitehall: The Diary of Raymond Streat). For the use of unpublished papers and documents I am grateful to Harold Ainley (Ainley papers), Tony Benn (Tony Benn papers), Bodleian Library (Attlee papers, Lord George-Brown papers, Goodhart papers, and Anthony Greenwood papers), British Library of Political and Economic Science (Beveridge papers, Dalton papers, and Shinwell papers), Lord Cledwyn (Cledwyn papers), John Cousins (Frank Cousins papers), Susan Crosland (Crosland papers), Anne Crossman (Crossman papers), Livia Gollancz (Victor Gollancz papers), the Gordon Walker family (Gordon-Walker papers), Lady Greenwood (Anthony Greenwood papers), Lord and Lady Kennet (Kennet papers), Labour Party Library (Labour Party archives), Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick (Maurice Edelman papers and Clive Jenkins papers), the Warden and Fellows of Nuffield College, Oxford (Cole papers, Fabian Society papers and Herbert Morrison papers), Hon. Francis Noel-Baker (Noel-Baker papers), National Museum of Labour History, Manchester (Parliamentary Labour Party papers), Frieda Warman-Brown (Lord George-Brown papers), Ben Whitaker (Ben Whitaker papers), the Wilson family (Wilson family papers).

I am extremely grateful to the following people, who have talked to me in connection with this book: Harold Ainley, Lord Armstrong of Ilminster, Tony Benn, Sir Kenneth Berrill, H.A.R. Binney, Lord Bottomley, Professor Arthur Brown, Sir Max Brown, Sir Alec Cairncross, Lord Callaghan, Bridget Cash, Baroness Castle, Lord Cledwyn, Brian Connell, John Cousins, Lord Cudlipp, Tam Dalyell, Lord Donoughue, Baroness Falkender, Peggy Field, Michael Foot, Paul Foot, John Freeman, Lord Glenamara, Geoffrey Goodman, Lord Goodman, Joe Haines, Lord Harris of Greenwich, the late Dame Judith Hart, Roy Hattersley, Ron Hayward, Lord Healey, Janet Hewlett-Davies, Lord Houghton, Lord Hunt of Tamworth, Henry James, Lord Jay, Lord Jenkins of Hillhead, the late Peter Jenkins, Jack Jones, Lady Kennet, Lord Kennet, Lord Kissin, David Leigh, Lord Lever, Sir Trevor Lloyd-Hughes, Lord Longford, Lord Lovell-Davies, David Marquand, Lord Marsh, Lord Mayhew, Lord Mellish, Ian Mikardo, Jane Mills, Sir Derek Mitchell, Sir John Morgan, Lord Murray, Sir Michael Palliser, Enoch Powell, Merlyn Rees, William Reid, Jo Richardson, George Ridley, Lord Rodgers, Andrew Roth, A.J. Ryan, Lord Scanlon, Lord Shawcross, Peter Shore, Professor Robert Steel, Sir Sigmund Sternburg, Sir Kenneth Stowe, Lord Thomson of Monifieth, Alan Watkins, Ben Whitaker, Sir Oliver Wright, Lord Wyatt of Weeford and Sir Philip Woodfield. I also interviewed a number of other people who prefer not to be named. Where it has not been possible to give the source of a quotation in the notes, I have used the words ‘Confidential interview’. I apologize for the frequency with which I have had to resort to this formula. Andrew Thomas interviewed Harold Ainley in Huddersfield, and Jim Keight, Ron Longworth and Phil MacCarthy in the North-West. I would like to thank them as well.

I am deeply grateful to Professor David Marquand who has read the whole of my manuscript, and to Dr Hugh Davies who has read the sections which touch on economic questions. Their careful and detailed comments, based on wide experience and expert knowledge, have been an invaluable help. More than is usually the case, however, it needs to be stressed that the opinions expressed in this book are those of the author alone. I am greatly indebted to Anne-Marie Rule, who typed the manuscript with her usual speed, care and professional skill, who I always have in mind as my first audience, and whose many kindnesses are part of the background to my work. I am grateful for secretarial and other much valued assistance, at various stages of the project, to Audrey Coppard, Harriet Lodge, Susan Proctor, Kim Vernon, Terry Mayer and Joanne Winning. I would also like to thank my colleagues and students at Birkbeck, who have provided an intellectual atmosphere, at once stimulating and relaxed, that creates the ideal conditions for research.

I wish to express my gratitude to Stuart Proffitt, the ideal publisher, at HarperCollins; to Rebecca Wilson, my hawk-eyed, perfectionist and tireless editor, who has been a joy to work with; and to Melanie Haselden for imaginative picture research. I would also like to thank Giles Gordon, my friend, literary agent and therapeutic counsellor. It was Giles who – over a very pleasant lunch in 1988 – was pretty much responsible for setting the whole thing in motion.

Other friends have helped in ways too numerous to mention. I should like, however, to express my special gratitude to David and Linda Valentine, and to Susannah York, who – with immense kindness – lent me their respective houses on the Ionian island of Paxos, where a large part of this book was written.

Most of all I wish to thank my wife, Jean Seaton, my cleverest and most inspiring critic, about whom I do not have words to say enough. Her insight and her passion for ideas have been vital to this book, as to everything I write.

Ben Pimlott

Gower Street

London WC1

September 1992

Part One (#ulink_2dde6fe5-e892-50a2-964d-981980023eff)

1 (#ulink_63fb9125-eb35-5ccb-910f-35fb86aaffab)

ROOTS (#ulink_63fb9125-eb35-5ccb-910f-35fb86aaffab)

When James Harold Wilson was born in Cowersley, near Huddersfield, on 11 March 1916, his father Herbert was as happy and prosperous as he was ever to be in the course of a fitful working life. The cause of Herbert’s good fortune was the war. Nineteen months of conflict had turned Huddersfield into a boom town, putting money into the pockets of those employed by the nation’s most vital industry, the production of high explosives for use on the Western Front. Before Harold had reached the age of conscious memory, the illusion of wealth had been destroyed, never to return, by the Armistice. Harold’s youth was to be dominated by the consequences of this private set-back and by a defiant, purposeful, family hope that, through virtuous endeavour, the future might restore a lost sense of well-being.

Behind the endeavour, and the feeling of loss, was a sense of family tradition. Both Herbert and his wife Ethel had a pride in their heritage, as in their skills and their religion, which – they believed – set them apart. When, in 1963, Harold Wilson poured scorn on Sir Alec Douglas-Home as a ‘fourteenth Earl’, the Tory Prime Minister mildly pointed out that, if you came to think about it, his opponent was the fourteenth Mr Wilson. It was one of Sir Alec’s better jokes. But it was also unintentionally appropriate. The Wilsons, though humble, were a deeply rooted clan.

They came originally from the lands surrounding the Abbey of Rievaulx, in the North Riding of Yorkshire. The connection was of very long standing: through parish records a line of descent can be traced from a fourteenth-century Thomas Wilson, villein of the Abbey lands.

The link with the locality remained close until the late nineteenth century, and was still an active part of family lore in Harold’s childhood: as a twelve-year-old, Harold submitted an essay on ‘Rievaulx Abbey’ to a children’s magazine. Herbert knew the house near to the Abbey where his forebears had lived. In his later years in Cornwall, he called his new bungalow ‘Rievaulx’,

and Harold included the name in his title when he became a peer.

‘When Alexander Lord Home was created the first Earl of Home and Lord Dunglass, in 1605’, researchers into Harold’s ancestry have pointed out, ‘there had already been seven or eight Wilsons in direct line of succession at Rievaulx.’

Through many generations, Wilsons seemed to celebrate the antiquity of their family in the naming of their children. Herbert and Ethel called their son Harold, after Ethel’s brother Harold Seddon, a politician in Australia. But Harold’s first name, James, belonged to the Wilsons, starting with James Wilson, a weaver who farmed family lands at Helmsley, near Rievaulx, and died in 1613.

Thereafter James was the most frequently used forename for eldest or inheriting sons. Thus James the weaver begat William, whose lineal descendants were Thomas, William, William, James, John, James, James, John, James, James, John, James, before James Herbert, father to James Harold, whose first son, born in 1943, was named Robin James, and grew up knowing that there had been James Wilsons for hundreds of years. Indeed, Harold was not just the twentieth or so Mr Wilson, but the ninth James Wilson in the direct line since the accession of the Stuarts.

Wilsons did not stray more than a few miles from the Abbey for several centuries. The religious upheaval of the Civil War in the mid-seventeenth century brought a conversion from Anglicanism to Nonconformity, an affiliation which the family retained and retains. Otherwise there were few disturbances to the pattern of a smallholding, yeoman existence, in which meagre rewards from farming were eked out by an income from minor, locally useful, crafts. Not until the nineteenth century did the importance of agriculture as a means of livelihood decline for the Wilson family.

It was Harold’s great-grandfather John, born in 1817, who first loosened the historic bond with the Abbey garth. John started work as a farmer and village shoemaker, taking over from his father and grandfather the tenancy of a farm in the manor of Rievaulx and Helmsley, and living a style of life that had altered little for the Wilsons since the Reformation. John married Esther Cole, a farmer’s daughter from the next parish of Old Byland, close to Rievaulx. (During Harold’s childhood, Herbert took his family to visit Old Byland, where they stayed with Cole cousins who ran the local inn.) In the harsh economic climate of the 1840s, however, it became difficult to make an adequate living from the traditional family occupations. At the same time, the loss of trade that had thrown thousands out of work and onto the parish in many rural areas of England, created new opportunities of a securely salaried kind. John Wilson had the good fortune, and resourcefulness, to take one of them.

In 1850, Helmsley Workhouse was in need of a new Master and Relieving Officer (for granting ‘outdoor’ relief). The incumbent had been forced to resign after an enquiry into his drunkenness and debts. At first, John Wilson agreed to take his place for a fortnight, pending the choice of a successor. The election which followed was taken with the utmost seriousness by the Helmsley Parish Guardians. An advertisement in the local newspaper produced fourteen husband-and-wife teams for the joint posts of Master and Matron of the Workhouse, which took both male and female paupers. References were submitted, all fourteen were interviewed and six were shortlisted. The ensuing contest, by the exhaustive ballot system, was tense. Though Wilson was well known locally, and had the advantage of being Master pro tem, there was strong opposition to his appointment. After the first vote, he was running in third place. After the second, with four candidates still in the race, Wilson tied with a Mr Jackson at 14 each. In the run-off, Wilson and Jackson tied again. Fortunately, Wilson was still owed two weeks’ salary by the previous Master, for the period in which he had replaced him. This tipped the scales. The minutes of the meeting record that the Chairman gave his casting vote in favour of Wilson, and declared John Wilson and Esther his wife duly elected.

It was scarcely an elevated appointment. The accommodation was so restricted that the new Master and Matron were permitted to take only one of their children in with them. Yet, it was a decisive turning-point.

John was a man of restless ambition. He continued to farm the lands at Helmsley, and the appointment was partly a way of supplementing a small income. But there was more to it than that, as his later career shows. John not only became the first Helmsley Wilson to take a public office: he was also the first of his line with a vision of a future that extended beyond the parish. In 1853 he and his wife applied for and obtained posts as Master and Matron at the York Union Workhouse, Huntingdon Road, York, at salaries of £40 and £20 each, with the prospect of an increase to £50 and £30 after a year. This was appreciably more than the £55 in total which they had received at Helmsley, though it involved moving away from the small community, and the lands, which Wilsons had farmed for centuries.

The Wilsons’ desire to better themselves did not stop there. Two years after arriving at York Union, they felt secure enough to bargain their joint salaries up from £80 to £100. With this they were prepared to rest content, turning the York Union into a family undertaking, in which one of their daughters was also involved as Assistant Matron. They retired in 1879 when John Wilson became seriously ill. He died two years later. Esther survived him, and lived in York until her own death in 1895. Both she and her husband had received a pension in recognition of twenty-six years at the Workhouse in which they had ‘most efficiently, successfully and to the satisfaction of this Union discharged their duties …’

John and Esther’s son James, Harold’s grandfather, was the last of Harold’s forebears to be born at Rievaulx. James finally severed the ancient link, becoming the first to give up the husbandry of the lands around the Abbey ruins. He moved to Manchester in 1860, at the age of seventeen, apprenticed as a draper, and later worked as a warehouse salesman. He was also the first to wed out of the locality. It was a significant match: his marriage to Eliza Thewlis was a socially aspirant one. Eliza’s father, Titus Thewlis, was a Huddersfield cotton-warp manufacturer who employed 104 workers (including, as was later revealed, some sweated child labour). This might have meant a generous dowry. Unfortunately for the Wilsons, however, Eliza was one of eight children.

The James Wilsons themselves had five children and were never well off.

Though the Thewlis connection brought little money, it provided a new influence, with a vital impact on the next generation: an interest in political activity. ‘Why are you in politics?’ Harold was asked in an interview when he became Labour Leader. ‘Because politics are in me, as far back as I can remember,’ he replied. ‘Farther than that: they were in my family for generations before me …’

Harold was not the fourteenth political member of his family, but he was far from being the first. According to Wilson legend, Grandfather James had been an ardent radical who celebrated the 1906 Liberal landslide by instructing the Sunday school of which he was superintendent to sing the hymn, ‘Sound the loud timbrel o’er Egypt’s dark sea/Jehovah hath triumphed, his people are free.’

There were Labour, as well as Liberal, elements in the family history. Herbert Wilson’s brother Jack (Harold’s uncle), who later set up the Association of Teachers in Technical Institutions and eventually became HM Inspector of Technical Colleges, had an early career as an Independent Labour Party campaigner. In the elections of 1895 and 1900, he had acted as agent to Keir Hardie, the ILP’s founder. The most notable politician on Herbert’s side of the family, however, was Eliza Wilson’s brother, Herbert Thewlis, a Manchester alderman who became Liberal Lord Mayor of the city. Harold’s great-uncle Herbert happened to be constituency president in northwest Manchester, when Winston Churchill fought a by-election there in 1908, caused by the need to recontest the seat (in accordance with current practice) following his appointment as President of the Board of Trade. Alderman Thewlis assisted as agent, and Herbert Wilson, Harold’s father, helped as his deputy. It was a famous battle rather than a glorious one. Churchill lost the seat, and had to find another in Dundee. Nevertheless, the Churchill link was a source of gratification in the Wilson family, as the fame of the rising young politician grew, and Harold was regaled with stories about it as a child.

Herbert Wilson’s main period of political involvement had occurred before the Churchill contest. Herbert’s story was one of promise denied. Born at Chorlton-upon-Medlock, Lancashire, on 12 December 1882, he had attended local schools, and had been considered an able pupil, remaining in full-time education until he was sixteen – an unusual occurrence for all but the professional classes. There was talk of university, but not the money to turn talk into reality. Instead, he trained at Manchester Technical College and entered the dyestuffs industry in Manchester. Though he acquired skills and qualifications as an industrial chemist, it was an uncertain trade. In the early years of the century fluctuations in demand and mounting competition brought periods of unemployment. It was during these that Herbert became involved in political campaigning.

In 1906, at the age of twenty-three, Herbert Wilson married Ethel Seddon, a few months his senior, at the Congregational Church in Openshaw, Lancashire. Ethel also had political connections, though of a different kind. Her father, William Seddon, was a railway clerk, and she had a railway ancestry on both sides of her family. The working-class element in Harold’s recent background, though already a couple of generations distant, was more Seddon than Wilson: Ethel’s two grandfathers had been a coalman and a mechanic on the railways, and her grandmothers had been the daughters of an ostler and a labourer.

Where Wilsons had been individualists, Seddons were collectivists. William Seddon was an ardent supporter of trade unionism, and so was his son Harold, the apple of the family’s eye. Ethel’s brother, of whom she was immensely proud, had emigrated to the Kalgoorlie goldfields in Western Australia, worked on the construction of the transcontinental railway, and made his political fortune through the Australian trade union movement.

As tales of Harold Seddon’s prosperity filtered back in letters, other Seddons joined him, including his father William, who got a job with the government railways.

During Harold Wilson’s childhood, Ethel’s thoughts were always partly with the Seddon relatives, to whom she was devoted, and who, in her imagination, inhabited a world of sunshine and plenty.

Such links with the world of public affairs – actively political uncles on both sides – added to the Wilsons’ sense of difference. Yet there was nothing grand about the connections, and there was no wealth. Social definitions are risky, because they mean different things in different generations. The Wilsons, however, are easy enough to place: they were typically, and impeccably, northern lower-middle-class. Their stratum was quite different from that of Harold’s later opponent, and Oxford contemporary, Edward Heath, whose manual working-class roots are indisputable.

But Herbert and Ethel did not belong, either, to the world of provincial doctors, lawyers and headteachers. In modern jargon, they were neither C2S nor ABs, but CIS.

On 12 March 1909, a year after the Churchill excitement, Ethel gave birth to her first child, Marjorie. Herbert’s political diversions now ceased, and for seven years the Wilsons’ attention was taken up by their cheerful, intelligent, rotund only daughter. Perhaps it was the unpredictable nature of the dyestuffs industry which deterred them from enlarging their family. At any rate, in 1912 the vagaries of the trade uprooted them from Manchester – the first of a series of nomadic moves that punctuated their lives for the next thirty years. Herbert’s search for suitable employment took him to the Colne Valley, closer to Wilson family shrines. Here he obtained a job with the firm of John W. Leitch and Co. in Milnsbridge, later moving to the rival establishment of L. B. Holliday and Co. Milnsbridge was one mile west of the boundary of Huddersfield. Herbert rented 4 Warneford Road, Cowersley, a small terraced house not far from the Leitch works and adequate for the family’s needs: with three bedrooms, a sitting-room, dining-room, and lavatory and bathroom combined, as well as small gardens back and front.

The chemical industry was already fast expanding in Huddersfield and the outlying towns. Established early in the nineteenth century, local manufacturing had been built up partly by Read Holliday (founder of L. B. Holliday) and partly by Dan Dawson (whose successors were Leitch of Milnsbridge), who developed the use of coal tar. By 1900 Huddersfield was proudly claiming to be the nation’s chief centre for the production of coal-tar products, intermediates and dyestuffs. There were a score of factories servicing the woollen and worsted mills, providing a series of complex processes which went into the dyeing of cloth, including ‘scouring, tentering, drying, milling, blowing, raising, cropping, pressing and cutting’.

Huddersfield, like other industrial towns, felt the disturbing impact of German rivalry in the years before the First World War. What seemed a threat to the area in peacetime, however, became a golden opportunity as soon as the fighting began. Dyestuffs were needed for the textile and paper industries. With German supplies no longer available, British production had to increase. ‘It was not until after War had broken out with Germany’, a Huddersfield handbook observed, and the humiliating fact of our too great dependence upon that country for many valuable, nay, vital products, became unpleasantly manifest that the general British public, and even Government circles, began to realize how essential to the life of a great nation was a well-organized and highly developed coal tar industry.’ There was also another, fortuitous aspect: namely, that most high explosives used in modern warfare, in particular picric acid, trinitrotoluene (TNT) and trinitrophenylmethylmitramine (tetryl), were derivatives of coal tar, whose use and properties were familiar to the dyestuffs industry. Thus, Herbert’s first employer in Milnsbridge, Leitch and Co. (which described itself as a firm of ‘Aniline Dye Manufacturers and Makers of Intermediate Products, and Nitro Compounds for Explosives’) claimed to have been the first makers of TNT in Britain, having started to manufacture the substance as early as 1902.

H. H. Asquith, Liberal Prime Minister in 1914, was a Huddersfield man. By leading his government into the Great War, he transformed the economy of his home town. As the importance of artillery bombardment during the great battles in Flanders and northern France grew, so the demand for high-explosive shells became insatiable. Production in Huddersfield increased tenfold, with John W. Leitch and Co. a major beneficiary. By the summer of 1915, when Harold was conceived, both the firm and the town were booming (the word seems particularly appropriate) as never before.

Herbert Wilson was in charge of the explosives department of Leitch and Co. Before the war, this was a job of limited importance and modest pay. The starting wage of £2.10s. per week provided for the Wilsons’ needs, but permitted few luxuries. The sudden boost in production changed all that, and Herbert’s value to the firm, and his salary, rapidly increased. By 1916 Herbert was earning £260 per annum, plus an annual profit bonus of £100. Herbert and Ethel responded to their good fortune in two ways. They decided to have another child, partly in the hope (as it was said) of a son to carry on the family name, for Herbert’s married brother only had daughters. They also decided to move to a better neighbourhood. A year after Harold’s birth, as the big guns before the Somme threw into the German trenches the best that Huddersfield and Milnsbridge had to offer, Herbert, Ethel, Marjorie and Harold moved to 40 Western Road, Milnsbridge, a more salubrious address and a larger, semidetached house with a substantial garden. Such was the Wilsons’ new-found affluence that Herbert became an owner-occupier, paying £440 for the house – £220 from savings, the rest on a mortgage.

For Ethel and Marjorie, it seemed like a gift from heaven. Marjorie had a large room of her own. There was a cellar, where Ethel did the laundry, and a spacious attic, which in due course became Harold’s lair, with ample room to set up his Hornby train. It was, as a school-friend says, a middle-class dwelling in a middle-class area.

The peak of Herbert’s success, however, had not yet been reached. Eighteen months after the move, and doubtless anticipating the changed pattern of production after wartime needs had ceased, Herbert accepted a job as works chemist in charge of the dyes department at L. B. Holliday and Co., the nation’s biggest supplier of dyestuffs, at a salary of £425 per annum.

Prices had risen during the war, but even allowing for inflation, the mortgage and the baby, the Wilsons were now very much better off than they had been in 1914. At the age of thirty-six, Herbert had reached a plateau from which there would be no further ascent. His move to Holliday and Co. coincided almost exactly with the ending of the war. A contraction of the chemical industry followed, long before the onset of the national depression – placing a pall of uncertainty over all who worked in it. Yet there was no immediate cause for concern. Though demand for explosives fell sharply, it was some time before the dyestuffs industry faced pre-war levels of competition.

During Harold’s early childhood, the Wilson home was a visibly contented one, busily absorbed in the voluntary and community activities that were typical of a well-ordered, Nonconformist household. On the surface, it was not a complicated family. There were no rifts or rows or vendettas or mistresses or black sheep that we know of: and, perhaps, no wild passions or romances. If there were tensions, they were well hidden from each other and from the world. Although the Wilsons were healthy – surprisingly so, in Herbert’s case, for a man who worked with noxious chemicals – they were not handsome. Early, faded photographs display a benign, asexual chubbiness on both sides, the parents appearing undatably middle-aged before their time, the children plain, plump and bland. They were as they seemed: a family preoccupied by dutiful routines, kindly, fond, well-meaning. Were the Wilsons too good to be true? There is a lace-curtain, speak-well-of-your-neighbours, aspect to the early years of Harold which makes the sceptical modern observer uneasy, as though it masked a pent-up rage, like a coiled spring.

Eager striving best describes the Wilsons’ way of life. Frivolity had little place. Harold was taught to self-improve from a very tender age: when, at six, he wrote a letter to Father Christmas, accompanied by thirty hopeful kisses, his list of requests began with a tool box, a pair of compasses, a divider and a joiner’s pencil.

Religious observance was of central importance. Both Herbert and Ethel were Congregationalists, but, in the absence of a chapel of their denomination in the locality, they went to Milnsbridge Baptist Church. Much of their Christianity was formal: grace was said before meals, and the family regularly attended church and Sunday school. ‘I would not say there was an atmosphere of religious fervour,’ Harold later maintained.

Nevertheless, an interest in Church and faith suffused the atmosphere of the Wilson household, providing a framework for their social activities. These filled every leisure hour. Herbert ran the Church Amateur Operatic Society, Ethel founded and organized the local Women’s Guild, both taught in Sunday school. Pride of place was taken by the Scouts and Guides, in which all four members of the family were earnestly and devotedly involved.

The Boy Scout Movement, a last, moralizing echo of Empire, reached its nostalgic zenith as Harold was growing up. There was much in the Scouting ideal to appeal to the Nonconformist conscience: a simple, universal code, an emphasis on practical knowledge, on healthy, outdoor living, and on a rejection of what Lord Baden-Powell, in Scouting for Boys, called ‘unclean thoughts’. Scouting gave the Wilsons, newcomers to Cowersley and Milnsbridge, companionship and a sense of belonging to a wide, international network. It also provided an alternative ladder of promotion, with its own quaint hierarchy of quasi-military grades and positions of authority. Herbert became a District Commissioner, and is to be seen, proudly cherubic and clad in ridiculous wide-brimmed hat and neckerchief, in the local newspaper photographs which marked ritual occasions. Ethel was a Guide Captain; when Marjorie grew up she became a District Commissioner as well; and Harold rose to the level of King’s Scout.

Harold’s first serious ambition was to be a wolf cub. He joined the Milnsbridge Cubs just before his eighth birthday and in due course graduated to the 3rd Colne Valley Milnsbridge Baptist Scouts, later part of the 20th Huddersfield.

It was a large, active troop, which met every Friday and boasted a drum-and-bugle band. Harold was not just a keen scout, he was a passionate one. He always claimed the Scouting Movement as a formative influence, and the snapshots tell their own tale: Harold enthusiastically cooking sausages, or thrusting himself to the forefront of a group photograph, cheerful, perky, eager, and enjoying the campfire convivialities more seriously than his companions. It was in the Milnsbridge Cubs that Harold first met Harold Ainley, a school contemporary who became a Huddersfield councillor and made a speciality of giving interviews to journalists and biographers about his recollections of the future Prime Minister. Ainley is in no doubt about the importance of the Scouts, for both of them. ‘It gave us ideals and standards,’ he says.

Harold was a dedicated camper. He once travelled under the supervision of the local Baptist minister (who was also the scoutmaster) on a camping trip to a site near Nijmegen in Holland. On another occasion, as a senior patrol leader, Harold helped to wait at a scout dinner given for the Assistant County Commissioner, a Colonel Stod-dart Scott. They next met in the House of Commons as members of the parliamentary branch of the Guild of Old Scouts. Harold remained a faithful scouting alumnus. As a resident of Hampstead Garden Suburb he became chairman of the North London Scout Association, and as Labour Leader he liked to equate the Scouting Code with his own brand of socialism, quoting the Fourth Scout Law: ‘A Scout is a friend to all and a brother to every other Scout.’

He was fond of remarking that the most valuable skill he acquired was an ability to tie bowline knots behind his back and tenderfoot knots wearing boxing gloves: invaluable for handling the Labour Party.

His more relaxed fellow scouts may have found him a bit over-keen, and there is an aspect to some of the anecdotes which makes him sound like Piggy in a Huddersfield version of Lord of the Flies. ‘He was a good [patrol] leader and always got the best out of his lads,’ recalled Jack Hepworth, a member of the same troop, who later worked for the Gas Board. ‘But in some ways he was not popular. He tended to be swottish and seemed to know a lot and, naturally, some of the lads didn’t always like this.’

At the age of twelve he entered a Yorkshire Post competition which called for a hundred-word sketch of a personal hero. Harold wrote about the founder of the Boy Scouts, Baden-Powell, and won.

Fired by this triumph, he wrote a helpful letter to the Scouting Movement’s newspaper, The Scout. ‘I should like to use your little hint for strengthening a signalling flag in my column “Things We All Should Know”,’ replied the kindly editor, and sent him a Be Prepared pencil case as a reward.

Harold’s behaviour in the Scouts, as in school and at home, was that of a child who expects his best efforts to be warmly appreciated and applauded. There was plenty of applause at home where, from the beginning, Harold was the favourite child, almost a family project, in whom all hope was invested. Marjorie seems to have taken her usurpation in good part, at least on the surface. Harold was born the day before she was seven. ‘It was a sort of birthday present,’ she would tell interviewers, doubtless repeating what her parents said to her at the time. Even when Harold was Prime Minister, she used to speak of him as if he were half-doll, half-baby, the family adornment to be cosseted and treasured. ‘With the Press slating him left, right and centre I always feel very protective,’ she said in 1967. ‘You see, he’s always my younger brother.’

Marjorie never married. She stayed close both to her parents and to Harold. Christmases and holidays were often spent together. She became a frequent visitor at No. 10, and proudly boasted of her brother’s achievements to friends in Cornwall, where she lived in later years. But there was another side. Harold had been a birthday present, but he could also seem like a cuckoo’s egg in the cosy nest at Western Road. Fondness was combined with tension, which sprang from an inequality that was there from the beginning. Harold was the adored baby of the family: Marjorie was large, strong, sisterly but not always good-tempered. As Prime Minister, Harold confided to a Cabinet colleague that she had bullied him mercilessly.

One particular incident stuck in Harold’s own memory. It took place during a summer holiday at a northern seaside resort. Like Albert and the stick with the horse’s head handle, Harold met with a nasty accident – caused, not by a lion, but by Marjorie. Walking along the shore, brother and sister had a fight. Marjorie overpowered him, and flung him, fully clad, into the sea. Harold was badly scared, and his thick flannel suit was soaked through. Cold and shaken, he was taken off to a shop to buy new clothes.

Such events happen in most families. It did not amount to much. Yet it was the violence that shocked him. ‘He was terribly frightened,’ says a friend to whom he related the story. ‘In a sense, she was taking her revenge for all the attention he got.’

Her lot cannot, indeed, have been an easy one: she was expected to watch Harold’s brilliant successes and be enthusiastic about them, almost like a third parent.

Marjorie’s own achievements were automatically regarded as less important than her brother’s. There was a family story (such stories tend to encapsulate a truth) that when Marjorie exclaimed ‘I’ve won a scholarship!’ on winning an award to Huddersfield Girls’ High School, her four-year-old brother lisped: ‘I want a “ship” too!’

The point of this tale is, of course, the precocity of Harold, rather than the success of Marjorie. Later, when Herbert made a famous sightseeing trip to London, visiting Downing Street, it was Harold who accompanied him and had his photograph taken outside the door of No. 10, not his sister. When Ethel travelled to Australia to visit her father and brother, Harold went with her – Marjorie stayed in Milnsbridge to look after Herbert.

Marjorie played her part cheerfully. ‘Really they all joined together in worship of this young boy who was going to perform those great feats,’ says a friend. But Harold never forgot his sister’s ability to pounce. As an adult, he continued to regard her with wariness and awe, as well as affection. ‘I used to tease him by asking “How is Marjorie?”’ recalls a former prime ministerial aide. ‘He would put on a peculiar persecuted look and say: “Ah, Marjorie!” He saw Marjorie as somebody telling him what to do, making him do this or that.’

Marjorie was not the only powerful female member of the family. The other was Ethel, whom Harold resembled physically, while Marjorie looked like Herbert. Ethel Wilson was a source of calm and reassurance. Harold once described her as ‘very placid’.

She ‘always gave the impression of having no personal worries’,

and almost never lost her temper (a characteristic her son inherited). She had trained as a teacher, but no longer worked as such, throwing her energies into managing a family budget that was not always easy to keep in surplus, and into voluntary activities. Because she died before Harold became Labour Leader, she escaped press attention, and Herbert – who attended Labour Party Conferences and loved being interviewed – became the publicly known parent. But Ethel was the dominant figure in the family, and also the closest to Harold. ‘He had a strong bond with her,’ says Mary, Harold’s wife. ‘He was devoted to her. She was a very quiet woman with firm views.’

According to a friend, ‘Harold loved his mother more than his father.’

When Ethel died in 1957, her son felt the loss deeply. Years later, he told an interviewer: ‘I found I couldn’t believe – and I reckon I’m a pretty rational kind of man – that death was the end of my mother.’

Harold’s relationship with Herbert was affectionate, respectful yet detached: later he tended to indulge the old man’s whims, and treat him like an elderly and beloved pet, rather than look up to him. To outsiders, Herbert had a prickly Yorkshire reserve – he could seem withdrawn, aloof, even cold. He was always more volatile than Ethel, and more ambitious. Herbert’s most famous attribute, which he took little prompting to show off, was a quirky ability to do large arithmetical sums rapidly in his head. This was displayed as a party trick, but it was also an emotional defence. He loved numbers, perhaps more than people, and resorted to them in times of stress. One story (also revealing in unintended ways) recounts how, on the night before Harold’s birth, Herbert was working on some difficult calculations to do with his job. During a long and (for Ethel) painful night, he divided his time between attending to his wife, and attending to his calculations.

Harold inherited an interest in numbers, and also a freakish memory, from his father, though his Grandfather Seddon had a remarkable memory as well.

Herbert’s most important influence was political. Harold turned to his mother for comfort, to his father for information and ideas. There was an element of the barrack-room intellectual about Herbert, whose romantic interest in progressive politics was linked to his own professional frustrations. Herbert felt a strong resentment towards ‘academic’ chemists who, armed with university degrees, carried a higher status within the industry. The need for qualifications became an obsession, as did his concern to provide better chances for his son. One symptom of Herbert’s bitterness was an inverted snobbery, according to which, although privately he saw himself as lower-middle-class (an accurate self-attribution), he ‘always described himself as “working-class” to Tory friends’.

Another was a growing interest in the egalitarian Labour Party, which fought a general election as a national body for the first time in 1918, and had an especially notable history in the Colne Valley.

Harold entered New Street Council School in Milnsbridge in 1920, at the age of four and a half, joining a class of about forty children, mainly destined for the local textile mills. His schooldays did not start well: his first encounter with scholastic authority so upset him that he used to fantasize about jumping out of the side-car of his father’s motor cycle on the way to school and playing truant. The cause of his unhappiness was a school mistress who set the children impossible tasks and chastised them enthusiastically with a cane when they failed to carry them out. He concluded later that she was ‘either an incompetent teacher or a sadist, probably both’.

After the first year Harold’s life improved, and he quickly established himself as a brighter-than-average child, though not a remarkable one. He played cricket badly and football quite well, taking the position of goalkeeper in games on a makeshift pitch on some wasteland. In cold weather he used to skate with the other children in their wooden clogs on the sloping school playground. Harold Ainley recalls Wilson as a ‘trier’ at football, rather than a natural games player, and as a ‘very timid’ child. But he was methodical in the classroom. ‘I would say that he was a swot, definitely,’ says Ainley. He used to compete with a little girl called Jessie Hatfield. Usually, she beat him.

Harold was not a delicate or weakly boy, but illness stalked his childhood, as it did many of his contemporaries in the 1920s, before the availability of antibiotics or vaccination for many infectious diseases. ‘It is wise to bear in mind constantly that children are frail in health and easily sicken and die, in measure as they are young,’ a Huddersfield Public Health Department pamphlet warned, chillingly, a few years before Harold’s birth.

Harold came from a sensible, nurturing family. Nevertheless, his health aroused anxiety several times, and once gave cause for serious alarm.

1923, at the age of seven, he underwent an operation for appendicitis. For any little boy such an event (though in this case straightforward enough) would be upsetting, as much for the separation from his parents as for the discomfort. It is interesting that Wilson family legend links it to Harold’s earliest political utterance. ‘The first time I can remember thinking systematically about politics was when I was seven,’ he told an interviewer in 1963. ‘My parents came in to see me the night after my operation and I told them not to stay too long or they’d be too late to vote – for Philip Snowden.’

This anecdote appears in several accounts. Its point is to establish, not only that he was an advanced seven-year-old, but also (what critics often doubted) that he had been politically-minded from an early age. Yet even an exceptional child does not snatch such a remark out of the air. If Harold was talking about politics and Philip Snowden at the age of seven, one reason was that he happened to live in an unusual constituency.