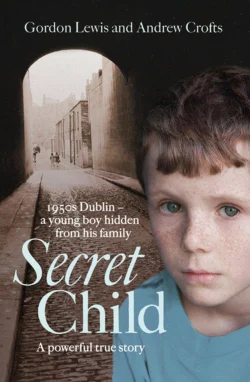

Secret Child

Andrew Crofts

Gordon Lewis

The shocking true story of a young boy hidden away from his family and the world in a Catholic home for unmarried mothers in 1950s Dublin.Born an 'unfortunate' onto the rough streets of 1950s Dublin, this is the incredible true story of a young boy, a secret child born into a home for unmarried mothers in 1950s Dublin and a mother determined to keep her child, even if it meant hiding him from her own family and the rest of the world.Despite the poverty, hardship and isolation, the pride and hope of a community of women who banded together to raise their children would give this boy his chance to find his real family.A wonderfully heartwarming and evocative tale of working class life in 1950s Dublin and 1960s London.

(#u4c1b79c5-3336-5fdc-9577-0913ed0e4e2b)

Copyright (#u4c1b79c5-3336-5fdc-9577-0913ed0e4e2b)

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

www.secretchild.com (http://www.secretchild.com)

First published by HarperElement 2015

FIRST EDITION

© Gordon Lewis and Andrew Crofts 2015

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Cover photographs © Ableimages/Alamy (boy, posed by model); Hugh Doran/Irish Architectural Archive (Dublin background)

Gordon Lewis and Andrew Crofts assert the moral

right to be identified as the authors of this work

A catalogue record of this book

is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/green)

Source ISBN: 9780008127336

Ebook Edition © April 2015 ISBN: 9780008127299

Version: 2015-03-16

Contents

Cover (#u86a4dddf-6834-5a62-8c38-eb27f93e1e64)

Title Page (#ulink_5b90b031-e6c2-5bc0-bde7-9c8350ce13d2)

Copyright (#ulink_f425c312-3273-5f6d-9525-5ecf03a7e2fc)

Chapter One: Going Home (#ulink_903834cd-d1ec-57c6-8479-7d0ab6231b39)

Chapter Two: Divine Intervention (#ulink_d9bd7a53-250d-58a2-9002-75082e0caa77)

Chapter Three: A New Start (#ulink_dd76d23c-678a-5998-a826-6ddb008f4402)

Chapter Four: Decision Time (#ulink_0ffb2ad6-a872-5376-bfbb-4f0e37361227)

Chapter Five: Back to the Beginning (#ulink_610ec305-c2c1-5665-ba2a-46c3d89b9080)

Chapter Six: So Long, Francis (#ulink_70ac2b5f-9bca-5b04-bc95-7009e6b3b33c)

Chapter Seven: He Who Dares (#ulink_498a17e3-a0f5-5acd-b02b-0fc03c778ca1)

Chapter Eight: Off the Rails (#ulink_412bd109-541f-5dd0-ac62-7c5caff1e064)

Chapter Nine: Moving On (#ulink_212d8686-333c-587c-8a2a-5d2eaaa90988)

Chapter Ten: Brave New World (#ulink_f9ab7e93-69fb-5e72-bc65-cfe18b500996)

Chapter Eleven: Happy Families (#ulink_451b15e8-ae49-5458-b318-bdad042e0899)

Chapter Twelve: Hard Times (#ulink_45625042-dfd5-5089-89c3-1ea09d13c430)

Chapter Thirteen: A Real Education (#ulink_48a8df58-821f-5061-ba5b-4229cd364ce7)

Chapter Fourteen: A Hard Day’s Night (#ulink_3397a410-b636-5014-b990-875d237eacf2)

Chapter Fifteen: Lessons (#ulink_97b6bdab-a9d6-5a9b-adcf-928f55da9d32)

Chapter Sixteen: The Story of My Mother and Father (#ulink_b01e7e49-c8f1-55d0-b89b-c778345035e8)

Acknowledgements (#ulink_37baed40-8889-5bcb-93a4-f282bd89667b)

Exclusive sample chapter (#u7422b45f-c8dd-57d3-82e6-52b2db78ae2a)

If you like this, you’ll love … (#u95b370e4-4bb8-57aa-9bc4-ce36c0e0df89)

Moving Memoirs eNewsletter (#u03a0e02c-a5fa-5930-99b8-f89cea21b870)

Write for Us (#u02ba4c1e-6897-589f-89be-42fa397a065b)

About the Publisher (#ud2ca4c8f-7f07-5f69-b293-f7317e489be5)

Chapter One

Going Home (#u4c1b79c5-3336-5fdc-9577-0913ed0e4e2b)

The flight was delayed but none of the passengers milling around the lounge seemed to mind too much. There was something of a party atmosphere at that end of the terminal at JFK that day, which added to my own sense of excitement at my impending adventure.

I felt strangely nervous considering how many times I had boarded flights before. This trip, however, was going to be different to the usual round of international business meetings and holidays. This was literally a trip into the unknown, back into a past filled with dark secrets.

It seemed like the whole flight was going to be packed with Irish Americans heading home for the St Patrick’s Day celebrations, many of them wearing something green for the occasion, and some of them already cheered by a couple of pints of Guinness, taken to pass the time. I deliberately avoided eye contact with everyone, wanting to keep myself to myself, protecting my thoughts, preparing myself for whatever might be awaiting me at the other end of the transatlantic flight. The last thing I wanted was to fall into a conversation where someone started asking me questions about my plans for the next few days.

To give myself something to do I pulled the small envelope out of my jacket pocket and stared for the hundredth time at the modest collection of black-and-white photographs it contained. I had stared at them so long and so hard over the previous few months I knew every faded detail by heart. It was like looking into a different world; one that should have been joined to mine by memories and stories shared by previous generations, but was in fact quite alien. I might as well have been looking at pictures of strangers, and those pictures on their own were never going to give up their secrets, however many times I studied them.

‘American Airlines flight to Dublin, Ireland is ready for boarding.’ The announcement made me jump and raised a jovial cheer from some of the revellers at the bar. ‘Will First and Business Class passengers please proceed to the boarding gate.’

I slipped the photos back into my pocket and stood up, walking through to my seat without talking to anyone, only half hearing the conversations going on around me and gratefully accepting a glass of champagne from the smiling stewardess as I settled down and stared out of the window at the tarmac, wanting the flight to be over so that I could get my adventure started. I realised that my nerves were partly caused by fear of what I was about to find out and partly by the thought that I might not find out anything at all. I did not want to have to return to New York none the wiser as to the events surrounding my birth and the early years, which my family seemed determined to keep shrouded in mystery.

Extracting even the barest facts from my cousin, Denis, had been an agony. Anyone would have thought I was trying to pull his teeth out rather than ask a few questions, as each one was met with a sigh and the barest of monosyllabic answers that he could get away with. If it hadn’t been for the fact that I was buying him dinner and that he was bound by politeness to stay at the restaurant table for the duration of the meal, he would have made his excuses and left the moment I raised the subject of the past. When I finally had to let him off the hook he swore blind he had told me everything he knew, but I was not at all sure he was telling the truth. That generation seemed to find it an agony to talk about anything personal or emotional, however far in the past it might be. Maybe he had buried some things so deep he had actually lost them for ever.

‘What do you want to be digging up all that old stuff for?’ he wanted to know. ‘It’s so long ago.’

‘That’s why I want to know,’ I persisted. ‘What harm can it do?’

‘You don’t want to be going over all that again,’ he muttered, ‘best to let sleeping dogs lie.’

‘I’ve been trying to piece together what happened,’ I went on, ‘and there are a few gaps that I need to fill in.’

I had refused to give up with the gentle interrogation, however much he evaded answering, and I doubted he would be accepting another dinner invitation from me for a long time. I pulled the pictures out again as the cabin crew went through their familiar rituals and the plane roared into life and lifted off from the runway. Despite the few things that Denis had reluctantly divulged, I was still having trouble getting a clear picture, which was why I had decided I had to make the trip back into the past for myself. I had to actually go to the streets where it had all started to see if they would jog my own memory, unlocking some of the doors in my head.

I had received the call from Patrick Dowling in Dublin two days before and had booked the flight immediately. He had been meticulously careful not to raise my hopes by making any promises, but I had grabbed at the straws he was holding out with all the desperation of a drowning man. He worked in some sort of public relations capacity for the Children’s Courts, and as a younger man he had also been a social worker in Dublin, so might know more about the sort of place that I had been kept for those early years. I felt sure the Court must have records from the time when I was born. Patrick was the best lead I had at the moment.

‘If you were to come in to see me next time you are in Dublin,’ he had said, ‘we could see what we can find out.’

I’m sure he was just being polite, hoping to put me off from what seemed to him like a lost cause. He certainly didn’t expect me to ring back a few hours later and tell him that I had booked my flight and would be with him in three days’ time.

‘I can’t promise anything …’ he’d said quickly, probably horrified to think he might not be able to help me after I had travelled all the way from New York to see him.

‘I understand,’ I assured him, ‘I’m just grateful that you are willing to help.’

I did understand how slim the chances of success were, and how little information I was going to be able to give him to go on, but that didn’t stop me from being ridiculously optimistic – and nervous.

I was aware that the Dublin taxi driver was watching me in his mirror and I tried to avoid his eyes, not wanting to be drawn into the conversation that he was obviously keen to have.

‘Can I ask,’ he said eventually, ignoring all the signals I must have been giving off, ‘do I hear an Irish or an American accent?’

‘Probably a mixture,’ I replied, giving up all hope of being able to remain alone with my thoughts for the duration of the ride from the airport into the city centre. ‘I’ve been living in New York for a long time, but I was born in Ireland.’

‘I thought as much,’ he crowed, obviously pleased with his own powers of perception. ‘You dress like a Yank, in your smart suit, and you have that American twang about your voice. But then I thought you must be Irish with those deep blue eyes and your looks.’

Believing that the ice had been broken between us he continued to chatter and I was able to drift in and out of the conversation as he pointed out local landmarks and buildings that he felt had probably arrived since I was last in the city. I could see there had been a lot of changes, but the essence of the city remained the same, with street after street of red-brick houses, every corner seeming to boast a pub. What surprised me was how small everything seemed after New York. The buildings had seemed so huge when I was a child, the roads so wide.

‘Is this your first time at the famous Shelbourne Hotel?’ he enquired.

‘Yes,’ I nodded and smiled at him in the mirror. It wasn’t completely true; I had been there before, more than fifty years ago. Although I had only been visiting for tea, it was an event that was etched deeply on my memory. It was the day when I first met Bill and realised that everything in my life was about to change and that nothing about my past was quite as I had believed it to be. I had never experienced anything like that tea before, and wouldn’t again for many years. It had been like arriving unexpectedly on a different planet.

‘Hello and welcome to the Shelbourne Hotel,’ the young receptionist beamed, ‘may I have your name, please, sir?’

‘Gordon Lewis,’ I replied, handing over a credit card.

She scanned her screen with well-practised speed. ‘Ah, yes, Mr Lewis, we have a nice suite for you, overlooking the park.’

I didn’t need a suite, but because I had booked at such short notice it had been all they could offer me. She signalled a bellboy to take my case up.

‘How long do you plan to stay with us, Mr Lewis?’ she continued as she typed.

‘It’s a little open-ended,’ I confessed, ‘I will know better in a few days.’

‘That’s fine, Mr Lewis,’ she said. ‘Enjoy your stay with us.’

I walked to the lift with the bellboy, looking forward to being alone behind a closed door with my thoughts. Once the bellboy had gone I pulled back the net curtains and stared out at the green of the trees opposite. Even though I had been living in the nicest parts of New York and other cities, the little boy in me was still impressed to find myself in the best hotel on the south side of the river in Dublin.

I had thought I would rest a little and then go out for a walk to acclimatise myself to the city of my birth, maybe find a noisy bar where I could lose myself in a dark corner and allow my mind to wander back over the years; but as the rain started tapping gently on the elegant old Georgian window I seized the excuse to stay where I was, turning on the television to watch the St Patrick’s Day parade. I would be spending plenty of time in the coming days pounding the streets and sitting in the bars as I tried to unearth the truth.

The next morning I rose early, too wired to sleep despite the time difference with New York. The rain had lifted and sun streamed into the room as I pulled back the curtains and ordered breakfast. An hour later I was down in reception, struggling with a map of the city.

‘Good morning, sir.’ I looked up to find a bellboy smiling at me. ‘Do you need any help? Do you know where you want to go?’

‘Yes,’ I said, a little too quickly. ‘I know where I’m going. Thanks all the same.’

I folded the map into my pocket and walked briskly out of the hotel, hoping that I looked like a man who knew where he was heading. I didn’t feel like sharing any information with anyone, however well-meaning they might be. The habit of secrecy was too ingrained for me to be able to shrug it off that easily after so many years. The boy’s accent had brought back unsettling memories. My friends and I must have sounded exactly like that when we were the little ‘unfortunates’, running wild on the streets of north Dublin. Anyone who comes from Dublin knows the difference between those from the ‘north side’ of the River Liffey and those from the more prosperous ‘south side’.

Once I was out of sight of the hotel I slowed down, my heart still thumping in my chest as I forced myself to stroll at a more leisurely pace towards the O’Connell Bridge with its ornate stone carvings and elegant Victorian street lanterns. I believe it is the only bridge in Europe that is as wide as it is long. Half-way across the bridge I stopped amid the bustle of people and traffic. Little had changed, except for me. Last time I had stood there, waiting with my mother for the meeting that was going to totally alter the course of my life, I had been too small to see over the side, peering through the stone balustrades and jumping impatiently up and down, wanting to get a better view of the detritus of the city as it drifted in the waters flowing under the bridge.

I leaned for a few moments on the rough stone which had then been taller than me and looked down at the flotsam and jetsam moving in the water below, the memories flooding my brain in a confusing montage of images and emotions which seemed more like half-remembered dreams, making my heart crash in my chest. Every direction I looked triggered more memories; the bridges, the buildings, the people. Every church spire seemed familiar, probably because I had been inside most of them at one time or another. Even the buses, which had been my first passport to the outside world, were parked in the same place on the embankment, or ‘Quays’, as they were known.

Now I might be able to stay in a hotel suite in the best hotel on the south side, but it was the north side that I came from; that was where my roots were, and that was where Patrick Dowling was waiting for me with whatever information he had managed to glean from the archives of half a century before. Breathing deeply, I steadied myself and continued on my way to my appointment at the old City Hall building where the children’s courts used to be, checking the map at every turn.

I felt like a small boy again as I announced myself to the receptionist and told her I had an appointment with Patrick Dowling. She made a call but hung up without saying anything.

‘He’s on the phone,’ she told me. ‘Take a seat and I’ll try again in a minute.’

As I sat staring at the sweeping metal staircase, not knowing what I was about to find out about my own past, my heart was thumping like it used to when I was a boy running wild around town in search of an adventure. It was like I was waiting for the curtain to rise on an eagerly anticipated new show. Every time someone came down I watched to see if they were likely to be looking for me, and after what seemed like an age a smartly dressed man with slightly wild grey hair descended and walked towards me with his hand extended.

‘Would you be Gordon Lewis?’ he asked with a friendly smile. ‘I’m Patrick Dowling. Welcome to Ireland. I hope it wasn’t too difficult to find us; we’re a bit tucked away from the other buildings in this area.’

He was tall and slim and I guessed he was in his forties, dressed in a dark two-piece suit, white shirt and tie, carrying a file in his other hand. He kept pushing strands of hair out of his face as he guided me towards a door on the ground floor, making polite conversation as he went, putting me at ease with typical Dublin humour.

Once inside the small room he closed the door and indicated for me to sit across the desk as he opened the file in front of him.

‘So, Gordon, you want to locate the home you lived in when you were a child?’

‘Yes,’ I nodded, hardly able to breathe in my anxiety to know what the file was going to reveal.

‘You would be amazed how many people like you come here looking for information about their past in Ireland. We do our best to keep records, but sometimes there are details which may be lost, or just not recorded.’

What was he saying? I felt a twinge of anxiety. Was he preparing me for disappointment? I nodded my understanding but couldn’t think of anything to say. After a moment he looked down at the file again.

‘A home for single mothers in Dublin in the 1950s, you say?’

‘Yes,’ I said, clearing my throat to stop the emotions from choking me. ‘My home, where my mother brought me up until the beginning of the sixties.’

‘The most infamous one, of course, was the Magdalene Laundries, where we now know that the girls and women were treated very badly, worked like slaves until they were old in order to atone for their sins. But those mothers weren’t allowed to keep their children. Usually the newborn babies were taken away for adoption or put into orphanages. But as I understand it, this didn’t happen to you?’

‘No.’ I didn’t trust my voice to say any more.

‘You were a lucky boy to have your mother to take care of you. Is there anything else you can remember about it?’

‘There were a lot of single women there, lots of us children too. Boys and girls. It was on the north side of the river and it was run by nuns.’ He was staring at me blankly as I racked my brains for more details. ‘I distinctly remember there was a mental hospital next door.’

He looked back down at his file for a moment. ‘There was a mental hospital in the area near this one.’ He pushed a map across the table and pointed to an area on the north side. ‘The institution was closed many years ago and the building is due for demolition. I don’t know what you’ll find if you go up there. The whole area is very run-down. It is bound to have changed a great deal since the fifties.’

He fell silent for a moment as I picked up the map and stared at it, trying to make sense of it, searching for names that might ring a bell, but to my confused eyes it just looked like a mess of lines and letters. Nothing made sense. I needed time to calm down and digest the information.

‘Does the name Morning Star Avenue, mean anything to you?’ he asked. I thought for a moment before shaking my head. ‘How about the Morning Star Hostel for Men? Or the Regina Coeli Hostel for Women?’

Regina Coeli. Was that a bell ringing somewhere at the back of my most distant memories? Or was it just that I wanted so much for something to sound familiar?

‘No,’ I said, ‘I don’t think so.’

‘I’m sorry we don’t have more details. There should have been files for every woman and every child in all these homes, but we had a burst water pipe about ten years ago and many files were ruined. All the names from that period were lost. I’m sorry that I can only give you so little to go on after you’ve come so far.’

At that moment I pictured myself going back to the hotel, picking up my stuff and catching the next flight back to New York, and the feeling of disappointment was overwhelming. I could see that Patrick was genuinely sorry not to be able to be of more help as he said goodbye at the door. I stood for a few moments on the pavement outside, not sure what to do next. I was still holding Patrick’s map. There didn’t seem any harm in at least going to look at the area he was talking about. Something there just might trigger my memories. I found Morning Star Avenue amid the jumble of print, worked out which direction I should be going in and set off.

It wasn’t long before the landscape began to change, all signs of the prosperity of the city centre gradually fading into areas of industrial wasteland. I don’t know how long I had been walking before I felt some vague stirrings of recognition. None of the street names rang a bell (though I wouldn’t have been able to read them when I was a boy anyway), but every now and then I saw a building or a view which I thought was familiar among the ruins and the occasional new developments. Then I would dismiss the idea again, telling myself I was imagining these things just because I wanted so much for them to be true.

Reaching the end of a long road I saw a large red-brick building, very different to everything that surrounded it. It looked imperial, like it had been a British headquarters of some sort. It seemed so familiar but no matter how hard I concentrated I couldn’t quite bring the memory into focus. The sound of loud voices caught my attention and I saw a group of people gathered on a litter-strewn piece of land further down the street. There seemed to be something familiar about them as well. As I drew closer I could see that they were men and women of different ages, but they were all drinking from bottles and I realised they had the same shabby, shambling look of the destitute, people who have ‘fallen through the net’ in society and ended up at this desolate roadside. Despite the bleakness of the scene, however, it felt strangely like home.

None of them gave me a second look. It was like I was an invisible ghost passing them by. I crossed over the road to the corner of the imperial-looking building and found a street sign announcing that I was standing in Morning Star Avenue. So was this the mental institution that I remembered? The one that Patrick said was due for demolition? Another street sign told me that the road would lead to a dead end. As I walked further along I noticed there was a slight slope, just enough to make my leg muscles ache, bringing back a memory of walking up a steep hill when I was a boy. Was this the same hill, turned into little more than a slope now that my legs were longer? I stopped and looked around at every view, desperately trying to recall distant pictures from the past.

I noticed grey railings along an overgrown garden to my right and a picture flashed up in my head. The narrow front garden had a statue of Our Lady Mary, the Virgin Mother, and on the wall beside a drainpipe a blue plaque announcing ‘Regina Coeli Hostel’. I felt a lurch of excitement in my chest. That was the name Patrick had given me which had rung a distant bell. Now that I was actually standing in front of it that bell was becoming clearer. This had to be the right place.

Behind the garden stood a long, two-storey, red-brick house. This was it – my first home! Regina Coeli was still standing after all these years. It was much smaller than the giant, rambling premises that I remembered as a small child, but now that I focused on it I could see details which reminded me of specific events. As I stared past the railings the memories came flooding back. I took my time looking around the garden at all the corners and spaces where I had played and hidden as a child, seeing them from a different perspective. Now the grounds which had seemed so enormous appeared quite modest. Something was missing. I concentrated hard and realised that next to the small house there should have been two huge wooden gates adjoining the building but they had gone. It didn’t matter. I was that little boy again. I had found my childhood home, the place which had seemed to me to be paradise, and now I would be able to unravel the rest of the story.

Chapter Two

Divine Intervention (#u4c1b79c5-3336-5fdc-9577-0913ed0e4e2b)

The steady drizzle had soaked through Cathleen’s coat, making the bite of the cold wind even sharper as it stabbed at her fingers, which had locked painfully around the handle of the modest suitcase containing all the possessions she had in the world. Her feet were wet inside her shoes and the water was dripping down her face from her drenched headscarf and hair. The clouds had extinguished the last vestiges of light from the moon and no lights shone from any of the closed or abandoned buildings that loomed up around her.

Turning into Morning Star Avenue, every muscle in her body aching from the long walk and the heavy case, she saw a group of people huddling round a bonfire, swathed in layers of ragged clothes, their faces lit eerily by the flames licking up from the fiercely burning rubbish. They all seemed to be holding bottles in hands bandaged with layers of grubby mittens, swigging as they talked, trying to warm themselves from the inside as well as the outside. They all turned to stare at her as she walked towards them. Her heart was thumping in her ears. She had no experience of people like this, no way of gauging whether they would resent her straying into their area. Would they ask for money? She had none to give them. Would they attack her? There were too many of them and they would easily be able to overcome her. Should she turn and run? If she did that she would have to drop her case in order to stand any chance of escaping in her current state, and where would she run to anyway? This place was her last chance.

Holding her nerve she kept walking, trying not to look in their direction, trying not to look scared. She could hear the crackling of their fire as she drew closer, the sparks struggling up into the sky before being extinguished by the rain.

‘You looking for someone?’ a voice called out. It sounded angry.

‘You lost?’ another asked.

She turned and looked straight at them, facing up to her fear, telling herself that they were just people like her, currently down on their luck. ‘I’m looking for Regina Coeli,’ she replied.

They all laughed, as if they had guessed as much. They exchanged comments, which she couldn’t hear but guessed were lewd from the way they cackled and jeered at their own wit, apparently enjoying her discomfort.

‘Keep walking up the hill,’ a woman’s voice called out to her once the noise had subsided. ‘It’s the only house up there. You can’t miss it.’

One of the men made another comment and they all cackled again, turning their faces back to the warm, orange glow of the flames and the comfort of their bottles. Cathleen walked on into the darkness until a glow of a single lamppost appeared ahead of her. As she drew closer she saw a lone figure standing stock still beneath the light. She glanced back to see if any of the down-and-outs were following her, but everything was silent and black and wet.

Moving the suitcase to her other hand she took a deep breath and kept going towards the still figure. As she drew closer she realised the figure was a statue of the Virgin Mary, standing behind some railings in the front garden of a red-brick house that she guessed must be her destination.

‘You silly woman,’ she muttered to herself, relieved to have arrived but now nervous about the reception that might await her inside. She paused for a second, putting down the case and stroking her stomach, stretching the muscles in her shoulders and back, raising her face to the rain for a few seconds as she composed herself for the giant step she was about to take into the unknown.

She spotted a small door set into high wooden gates, with a bell beside it. As she reached up to ring it the gate opened and a woman appeared, throwing a heavy overcoat over her shoulders, her head down in preparation for walking in the rain. She almost bowled Cathleen over in her hurry.

‘Can I help you, ma’am?’ the woman asked. ‘Are you looking for somebody?’

‘Is this the Regina Coeli Hostel?’ Cathleen enquired.

‘Yes, come in,’ the woman said, retracing her steps through the doorway and leading her into the hallway of the house. ‘I’m Sister Kelly. Let’s get you out of that wet coat.’

Cathleen was aware that a puddle was forming around her on the stone floor as she shrugged off the coat and untied the scarf, attempting to mop some of the water from her blonde hair.

‘Take a seat, my dear,’ Sister Kelly said, glancing down at Cathleen’s belly. ‘I was just on the way home myself, so I will fetch Sister Peggy to take care of you.’

Cathleen sat on a wooden bench as Sister Kelly bustled out of the room, and took several deep breaths. The kindness of the older woman and the relief of taking the weight off her legs and back made her want to cry, but she held back the tears and composed herself for whatever was going to happen next.

A few minutes later a small woman in thick glasses and a big blue apron bustled into the room, carrying a worn piece of towel.

‘Oh, you poor thing,’ she exclaimed, ‘you’re wet through.’ She handed Cathleen the thin towel. ‘Dry your hair before you catch your death. I’m Sister Peggy.’

Sister Peggy watched for a moment as Cathleen attempted to dry her face and head a little. This was not the sort of girl she was used to seeing at the gates of Regina Coeli. To start with she was obviously older – Sister Peggy guessed she was probably in her mid thirties – whereas most of them were teenagers when they first arrived. Her clothes looked better than the others too. They were certainly not grand in any way, but even in their drenched state she could see that this was a woman who looked after herself and cared about her appearance.

‘Let’s get you through to the fire,’ Sister Peggy said. ‘What shall I call you?’

‘My name’s Cathleen Crea.’

When she stood up Sister Peggy could see that Cathleen was several inches taller than her and she guessed, from looking at her stomach, that she was about seven months pregnant. She led her through to a sitting room where a fire gave off a welcoming glow. Cathleen sat close to the grate and her wet feet began to steam gently in the warmth.

‘How are you feeling, my dear? Nervous, I dare say.’

Cathleen smiled, not trusting herself to speak in case she started to cry, afraid that if she let even one tear out she would not be able to stop the torrent.

‘You’ll be fine; you have nothing to fear here. We’re not going to be asking you any questions or making any judgements. You don’t even have to use your real name if you would prefer not to. You will simply be “Cathleen” to us, if that is what you would prefer. Let’s have a pot of tea.’

‘I want to keep the baby,’ Cathleen said once the tea had been brewed and she was beginning to thaw.

‘Sure, you do,’ Sister Peggy patted her hand reassuringly, ‘and so you will. Let me tell you a little bit about who we are. We’re all volunteers working here from the Legion of Mary. We like to be known as “Sisters”, but we’re not nuns. You won’t find any of us walking about in black.’ She gave a little chuckle at the thought. ‘We all understand and respect the need for privacy and anonymity. If you want to keep your child a secret from the world, that is fine. You can live here while you prepare for the birth without anyone else knowing, and you and the child can stay afterwards as part of the community. If you have a boy you can stay until he is fourteen. If it is a girl then you can stay a little longer.’

‘I have no money, Sister,’ Cathleen confessed.

‘I’m sure that’s right, my dear. Everyone here is in the same boat. Once you have had the baby we would ask you to pay for your board and lodgings by going out to work. The child can be looked after here while you are out and provided with one free meal every day.’

‘Who would take care of the child?’ Cathleen asked, hardly able to believe her luck at finding such a refuge from the storm.

‘Some of our single mothers do not go out to work, preferring to stay here during the day and look after their own children and those of the mothers who do go out to work. The working mothers pay the ones who care for their children from their wages.’

‘I see,’ Cathleen said, taking another sip of her tea and staring into the fire.

‘We do have a few rules,’ Sister Peggy went on. ‘There can be no pets, no alcohol and no men in the hostel or in the grounds. There can be no exceptions to those rules.’

‘I understand,’ Cathleen replied.

‘Shall I show you where you will be staying?’ Sister Peggy asked, putting down her cup and saucer. ‘Do you feel up to it?’

‘Yes.’ Cathleen stood up, despite her legs feeling a little wobbly, and followed Sister Peggy up a staircase.

‘Until the baby is born you will be staying upstairs in this house,’ Sister Peggy explained, opening a door into a large open dormitory. There were ten neatly made beds on each side of the room. Beside each of the twenty beds was a baby’s cot. ‘That is the only spare bed we have at the moment,’ she said, pointing to the furthest bed, ‘so that will be yours. The mothers are all having supper with their babies at the moment. In a few minutes they will all be coming up here and it won’t be so peaceful. Let me show you the facilities.’

They went back downstairs and Sister Peggy showed her the open washrooms with three bathtubs and four toilet cubicles. ‘All these walls could do with a lick of paint, for sure,’ she said, seeing the expression on Cathleen’s face as she looked around the shabby facilities, ‘but everything is spotlessly clean.’

‘It all looks just fine to me, Sister,’ Cathleen said quickly. The whole of Regina Coeli felt to her like a sign from God, as if he had heard her prayers and decided to give her and her baby a second chance. She certainly didn’t want to show even a hint of ingratitude in the face of such kindness.

‘Over there,’ Sister Peggy said, pointing through the window at a dark building across the grounds, ‘is where the older children and their mothers live. I’ll show you all around tomorrow, when it’s light. We just have a little bit of paperwork to do now, so let’s get that out of the way.’

Leading Cathleen into a tiny office space she handed her a form and a pen. ‘If you can just register here, then we can get you settled in and introduce you to the others. You don’t have to put your real name, just decide what you would like to be known as while you are with us.’

Cathleen stared at the form for a few moments before making a decision and carefully writing down the name ‘Kay McCrea’. This was a new name for a new life. Cathleen Crea had disappeared from sight in this new world. Now it was just Kay McCrea and her unborn baby starting again, safe, secure, hidden from the outside world and the baby’s existence a secret from everyone in her past life.

By the time she took her suitcase up to the dormitory all the other women were already there. Many of them seemed little more than children themselves as they chattered to one another, some of them bouncing babies on their hips while others were settling theirs down in their cots, trying to rock them to sleep despite the surrounding noise of voices and crying. Cathleen felt very grown up as she walked all the way down the middle of the room. None of them looked as if they had been taking care of themselves, their hair was lank and unwashed, and their pasty complexions in need of some healing rays of sunshine. Dark shadows ringed their tired eyes and none of them seemed to have the energy to smile. Cathleen felt almost maternal towards them. A few of them nodded to her as she made her way to her designated bed and she smiled in return, but none of them introduced themselves or spoke to her. She was happy with that, wanting nothing more than to lie down and sink into a deep, exhausted sleep.

She was pulled back to consciousness just before dawn by the cries of the first baby to stir and demand attention. One or two of the girls let out muffled curses as they tried to cling to sleep for as long as possible. Gradually they started up conversations as they lifted their babies out of their cots to feed them. Cathleen lay quiet, putting off the moment when she would have to talk to anyone.

‘Good morning, ladies,’ Sister Peggy said, moving through the dormitory to check that everyone was alright. ‘Have you all met Kay, who joined us last night?’

Cathleen pulled herself up, her bump making it an awkward manoeuvre, aware that all the girls were now looking in her direction, still without smiles, or even much interest.

‘I thought you might like a bit of a tour round the rest of the grounds this morning, Kay,’ Sister Peggy said, ‘to familiarise yourself with your new home.’

The other mothers were going about their business again, any vestige of curiosity they might have had about the newcomer apparently sated already. ‘That would be nice,’ Kay said. ‘Thank you.’

After joining in the bustle of washing and having some breakfast, Cathleen and Sister Peggy ventured out into the bright winter sunshine. Many of the younger children had already burst out of the confines of the buildings and were running around the damp grass as happily as in any school playground anywhere in the world.

‘This is Bridie,’ Sister Peggy said, taking her to a woman with sad eyes. She was dressed all in traditional black, reminding Cathleen of her own mother and aunts. Cathleen guessed she was probably in her forties, her dark hair peppered with grey. She was watching over a group of about five children. It was a relief to see someone closer to her own age. ‘She will be looking after your baby once you are ready to go out to work.’

‘Do you have a child here yourself?’ Cathleen asked, and the other woman’s sad eyes lit up.

‘My Joseph is five now,’ she said proudly. ‘He’s just started going to school.’

‘He’s a lovely boy,’ Sister Peggy said, ‘a credit to you, Bridie. You can be sure your baby will be in safe hands, Kay.’

Without knowing any more about Bridie, Cathleen knew instinctively that that was true.

‘Let me show you the chapel,’ Sister Peggy said, leading Cathleen back into the house and up to a door next to the dormitory where she had slept. ‘We have services on Sundays and Holy Days, which I hope you will join us for. The local priest leads them for us.’

Sister Peggy knelt down in front of the small altar, slowly crossed herself and whispered a prayer so quietly that Cathleen could not make out the words. After a few seconds she knelt down beside her, placed her palms together, lowered her head and closed her eyes. The two women remained there for several minutes, silently thanking the Lord for everything they had.

‘Now,’ Sister Peggy said, pulling herself to her feet, ‘let me show you the rest of the hostel.’

The buildings, which had once been a British army barracks, were set in three acres of grounds. There were several blocks of forbidding, three-storey, grey stone buildings. Some parts were depressingly run-down, with broken windows and missing doors.

‘It’s enormous,’ Cathleen said as they walked towards the first of the buildings.

‘So it is,’ Sister Peggy agreed. ‘We don’t fill every building, just a few of the more habitable floors. About a hundred and fifty women live here at any one time, usually with one child each. You will come across to one of these buildings once you are up and about after the birth.’

The wide open spaces on the inhabited floors had been turned into gigantic open dormitories, their stone walls and high ceilings blackened by smoke from the open fireplaces which burned Irish turf all day long and provided both warmth and basic cooking facilities, heating pans of water for washing and making tea. In these blocks there was only one toilet for every forty people, less if there was a blockage, and to make life easier many of the women kept their own enamel basins and chamber pots under their beds.

‘Do they have no privacy?’ Cathleen asked as she looked around.

‘You soon get used to it, my dear.’

Sister Peggy introduced her to a few of the women, but none of them seemed particularly interested, doggedly carrying on with their daily chores.

‘These are care mothers,’ Sister Peggy explained, ‘the ones like Bridie who are looking after the children for those who go out to work.’

Cathleen was relieved to think that it was going to be Bridie who was looking after her baby rather than any of these morose and silent girls.

‘What happens on the other side of the perimeter walls?’ Cathleen asked as they walked back to the red brick building.

‘You mean outside our prison walls?’ Sister Peggy said, her eyes twinkling mischievously. ‘There’s a wood mill over there. It’s more like a warehouse for the timber. The Dublin bus depot is over there. That,’ she said pointing to particularly dark and forbidding-looking building, ‘is part of the Grange Gorman Mental Institution. We call them “the crazy ones”, Lord bless their souls. The children are terrified of them. They think they’re going to escape over the walls and attack them.’

‘Oh,’ Cathleen couldn’t hide her own disquiet.

‘Don’t worry, my dear, they can’t get out. They’re locked up tight for their own good. Sometimes you will hear their screams in the night, poor creatures. You’ll get used to the sounds. Would you like to go back to the dormitory now and rest? You look a little tired.’

Cathleen was grateful for a chance to lie down and think about everything she had seen. However sweet Sister Peggy had been to her, and however grateful she was to find a refuge from the cold, wet streets of Dublin, the idea of bringing her child into such a place brought a chill to her heart. She racked her brain to try to come up with a better solution to her predicament, but could think of nothing. There was one person who might help, of course, but she could never ask that of him. At least here she had a bed and food and they would let her keep the baby. She told herself she must be grateful for such mercies and that she would find a way to get out once the baby was born and she had regained her strength. If all these young girls could bear to live here, then surely to God she could manage it too.

Over the next two months she threw herself into the routine of the hostel, never leaving the premises and making herself as useful as possible with the other mothers in the kitchen or in the dormitories, gradually making some sort of contact with those who were willing to talk to her and spending as much time as she could with Bridie.

One evening, when the two of them were sharing a well-earned cigarette by the fireplace, Cathleen confided some of her fears about the impending birth.

‘It’ll be fine,’ Bridie assured her. ‘Before long you’ll have a beautiful baby and that will make everything you’ve gone through worthwhile.’

‘I’m not so worried about the birth, it’s more the future that concerns me. I want so much more than this for my child and I don’t know if I will be able to provide it.’

‘Love the child, Kay, that’s all you have to do. Material things don’t matter. Children don’t know the difference between expensive clothes and cheap ones.’

‘In here they might not,’ Cathleen agreed, ‘but what about outside? There’s a big heartless world out there where people will judge my child for not knowing who his father is.’ Bridie reached over and squeezed her hand, not able to think of any words of comfort. ‘Your Joseph is such a lovely boy,’ Cathleen went on, ‘so kind and considerate with the other children, and so helpful to you. You’ve brought him up well. Thank God it’s going to be you looking after my child.’ Bridie gave her friend’s hand another squeeze, embarrassed by the praise.

Most of the other girls paid Cathleen little attention but there was one, Bridget Murphy, who seemed to have taken an instant dislike to her. Bridget was a big, fat bully of a woman who seemed to see Cathleen as some sort of challenge to her authority. Cathleen had seen her reducing one of the youngest girls to tears.

‘Empty my piss pot,’ Murphy had instructed the girl.

‘Empty your own piss pot,’ the girl retorted, her bravado undermined by the tremble in her voice.

‘Empty my piss pot you fucking whore,’ Murphy screamed as the girl scuttled tearfully from the room. Everyone else averted their eyes, not wanting to attract Murphy’s vitriol onto them.

‘And you …’ Murphy screamed at Cathleen. ‘You need to watch yourself around here with all your airs and graces. Who do you think you are? Think you’re too good for the rest of us, you do.’

Cathleen didn’t respond, and from then on Murphy referred to her as ‘the Lady’, a nickname that the others also started to use for her, but as a show of respect rather than a term of abuse.

On 25 February 1953, Cathleen gave birth to Francis Gordon – that’s me – her secret child, and my life at Regina Coeli was under way.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/andrew-crofts/secret-child/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Andrew Crofts и Gordon Lewis

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 28.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The shocking true story of a young boy hidden away from his family and the world in a Catholic home for unmarried mothers in 1950s Dublin.Born an ′unfortunate′ onto the rough streets of 1950s Dublin, this is the incredible true story of a young boy, a secret child born into a home for unmarried mothers in 1950s Dublin and a mother determined to keep her child, even if it meant hiding him from her own family and the rest of the world.Despite the poverty, hardship and isolation, the pride and hope of a community of women who banded together to raise their children would give this boy his chance to find his real family.A wonderfully heartwarming and evocative tale of working class life in 1950s Dublin and 1960s London.