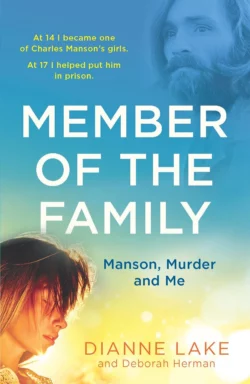

Member of the Family: Manson, Murder and Me

Dianne Lake

Following the recent death of Charles Manson – the leader of the sinister 60s cult – Dianne Lake reveals the true story of life with Manson and his ‘family’, who became notorious for a series of shocking murders during the summer of 1969.In this poignant and disturbing memoir of lost innocence, coercion, survival, and healing, Dianne Lake chronicles her years with Charles Manson, revealing for the first time how she became the youngest member of his Family and offering new insights into one of the twentieth century’s most notorious criminals and life as one of his “girls.”At age fourteen, Dianne Lake—with little more than a note in her pocket from her hippie parents granting her permission to leave them—became one of “Charlie’s girls,” a devoted acolyte of cult leader Charles Manson. Over the course of two years, the impressionable teenager endured manipulation, psychological control, and physical abuse as the harsh realities and looming darkness of Charles Manson’s true nature revealed itself. From Spahn ranch and the group acid trips, to the Beatles’ White Album and Manson’s dangerous messiah-complex, Dianne tells the riveting story of the group’s descent into madness as she lived it.Though she never participated in any of the group’s gruesome crimes and was purposely insulated from them, Dianne was arrested with the rest of the Manson Family, and eventually learned enough to join the prosecution’s case against them. With the help of good Samaritans, including the cop who first arrested her and later adopted her, the courageous young woman eventually found redemption and grew up to lead an ordinary life.While much has been written about Charles Manson, this riveting account from an actual Family member is a chilling portrait that recreates in vivid detail one of the most horrifying and fascinating chapters in modern American history.

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_fa15eb37-7dfa-50c2-9fa2-d9a4331191fa)

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in the US by William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

This UK edition HarperElement 2018

FIRST EDITION

Text © Dianne Lake 2017

All photos courtesy of the author

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Cover photographs © Vladimir Serov/Getty Images (model); Bettmann/Getty Images (Charles Manson)

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Dianne Lake asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN: 9780008274764

Ebook Edition © October 2017 ISBN: 9780008261481

Version 2018-03-09

DEDICATION (#ulink_cd8f2828-64fa-5989-b60a-d0b56eb0fbf1)

To the victims and their families; those who needlessly

lost their lives and those who continue to suffer because of

the madness of this dark time in our shared history. May

God’s grace prevail and heal the pain that remains.

CONTENTS

Cover (#uf6fdc071-8d2b-567a-a7c4-0f57e042c438)

Title Page (#u55755292-5fe6-5e0f-96d7-e9826af763d7)

Copyright (#ulink_93888085-bcee-52ea-ac34-31c777344b37)

Dedication (#ulink_f76ca89a-c3b3-5fc0-95fd-418e7ff93ea2)

Author’s Note (#ulink_2b7588bd-17d7-5c5b-a937-d0d65d797954)

Prologue (#ulink_1ac80443-76a3-54c1-8ae8-3dffaa3a0447)

PART I. TURN ON

1 A Minnesota Childhood (#ulink_ecdbdf97-0e39-5bc2-97b0-fb0e8d4be795)

2 Family Matters (#ulink_aea34423-14f0-5c47-aafd-22963196b7db)

3 One Stray Ash (#ulink_6a588239-6c74-5c13-91c4-6bc1ef999066)

4 California (#ulink_f76cd7e3-1775-5e63-acd8-416f9b2caefd)

5 How to Be-In (#ulink_b4708f3a-21a7-5a57-80b6-48b7d4c2ba37)

6 Hippies in Newsprint (#ulink_1eb45332-6df2-5088-b8fd-14d044ab0f81)

7 The Note (#ulink_58833945-c3c6-5d85-970b-67df45b47dfb)

8 Welcome to the Hog Farm (#ulink_112baca4-f704-5609-a8c0-d6e60fe9a1b7)

9 Someone Groovy (#ulink_b1f2ed93-7525-5c70-a1f0-382ce6223c14)

PART II. TUNE IN

10 The Black Bus (#ulink_d8003c61-b416-58b9-8ef8-f7517a3cfccb)

11 We Are All One (#ulink_837fe3c5-3a95-50cc-a488-1d99b05c282d)

12 Panhandling and Postulating (#ulink_cd9b1734-c52f-5b09-9f3c-f40643a74a07)

13 Snake (#ulink_5e4bebb6-0138-51ed-82ac-872e0b6e3e0f)

14 Spahn Ranch (#ulink_1bf89653-79f6-5707-a5ce-3321b7008b48)

15 Beach Boy (#ulink_dd242641-0263-5bf0-9eb2-0fe678e3afa2)

16 A Little Monkey (#ulink_7da69a07-e7f1-5f0e-824e-e6ddf29e0501)

17 A Door Closes (#ulink_26c56018-8735-581f-85e0-e2be45a8d175)

18 On the Edge (#ulink_7cdbbb77-f3e0-5816-b0b5-3766c0e65aea)

19 Baking Soda Biscuits (#ulink_0ff755b0-a610-5761-843b-7ea5b486b303)

20 Out of Sight (#ulink_14c6ad01-06e3-5ad0-8b08-e38795d00751)

21 Preaching the White Album (#ulink_e4f96c64-b2e6-516c-9cfc-1a69056a6f41)

22 A Simple Bag of Coins (#ulink_511fb243-5a5f-53e2-bfd5-8498113c67c7)

PART III. DROP OUT

23 The Witches’ Brew (#ulink_b234d22d-be8a-5ce8-8024-99107d04d951)

24 Reclaiming My Name (#ulink_6ad860ee-57d4-5763-8e78-2124c6029db4)

25 My Day in Court (#ulink_e9d9223d-8d6c-5ba0-b4e9-341d7f10afaa)

Epilogue (#ulink_948fc29f-9f55-5310-8960-729ea11bbcb1)

Acknowledgments (#ulink_086b7f47-81a1-514f-8913-2a7f09e2e8d0)

Photos Section (#ulink_42ee032c-e0e0-5ff3-8d0e-6ec1b5588322)

About the Publisher

AUTHOR’S NOTE (#ulink_35b2962a-1f13-5a5c-975d-10d82c90d9d9)

It is time for me to exorcise my own demons and to face the truth as much as I can remember it. In this book, I have shared what I can re-create through straining my memory muscle, research, corroboration from people who knew me, and my own words from trial and interrogation transcripts. They tell only my piece of the story from personal experience and perception. I was with the Manson Family from the age of fourteen until my arrest at Barker Ranch at the age of sixteen. My memories by necessity reflect the mind of a teenager. Everything in this book is true. Some of the names and identifying details have been changed to protect people’s privacy. Some conversations are re-created to the best of my ability, as no memory is perfect. This is my perspective. This is my story and this is my confessional.

PROLOGUE (#ulink_29225559-b78f-56f8-a612-a27e0fc72fe6)

2008

It began, as these stories often do, with a phone call, one that I had been dreading for decades.

“Are you Dianne Lake?” the voice asked.

The question stopped me in my tracks. I hadn’t heard that name for years. This could be about only one thing.

“Uh-huh,” I said hesitantly. “What do you want?”

Immediately after the words left my mouth, I regretted saying them. I’d done nothing wrong, committed no crimes, but I had a reason to hide. So many people out there had looked for me over the years—reporters writing about the crimes, journalists seeking sources for books about the Family—and of course the worst were the crazies obsessed with Charles Manson. For the most part, I’d been able to evade them all—flying under the radar all these years, hiding in plain sight with my husband’s last name. I immediately wished I had hung up the phone right at that moment, but it happened too fast, my answer a reflex. Even after all these years, I still wasn’t prepared.

I had buried my history so well I’d almost forgotten that once I was someone else: a young girl named Dianne Lake who was only fourteen when Charles Manson had inducted her into his Family of followers. A girl who had spent almost two years being manipulated by him before a moment of clarity broke the spell, and who then went on to testify against him on November 3, 1970, helping to put him in prison forever. Over the course of the eight years that followed, I’d been in and out of the courtroom through the Manson trial and two retrials of fellow Family member Leslie Van Houten, coming of age on the witness stand and telling my story to the juries and the judges, as well as to the gawkers who obsessed over the gruesome acts that were committed by Charles Manson and members of his Family on two nights in August 1969. I’d told stories of life with the Family, of the things we’d done and the drugs we’d taken, of how I’d joined with the blessing of my parents, hippies themselves, thinking that I was in control of my life, only to discover a reality darker than I ever could have imagined.

And in 1978, after my final appearance on the witness stand for Leslie Van Houten’s retrial, I put away these stories of Charles Manson and the Family and left them behind for good. In a case that had captured the attention of people around the world, where spectators waited all night for one of the fifteen seats in the courtroom, I was the last witness.

From then on, Charles Manson and his Family were a part of my past—they had nothing to do with my present or my future. By that point, I was already being courted by my husband, with whom I spent the next thirty-five years. He knew about my past, but we decided to create a life without ties to that former identity. We never told his family or the three children we went on to have together about what I’d been through. Even when my daughter brought in a stray cat and named it Charlie, I never acknowledged why I suggested she call him something else.

Over time, my memories of the Manson Family became watercolors, the lines soft and blurry without clear definition. Whenever I was reminded of the Family, either because of events in the news or anniversary retrospectives, I disconnected, all too willing to forget the events of my own life. Until the phone rang.

“I am Paul Dostie,” the voice said. “I am a detective and my partner is a cadaver dog named Buster.”

“What is this about?” I asked.

“I know that you told investigator Jack Gardiner that you thought there were more bodies buried up by Barker Ranch.”

Barker Ranch. It was where we’d hidden out after the murders, in Death Valley, the middle of nowhere and as far away as Charlie could take us. A place where they weren’t supposed to find us. Only they did. Two months after the killings, with a warrant for an unrelated charge of vandalism, the police raided Barker Ranch, rounding up all of us. In the interim it was Family member Susan Atkins, one of the killers, then in jail on another charge, who made the connection between these crimes and Charlie. I kept my identity secret as I shared a cell with the other girls in the Family. When it came time to testify before the grand jury, I admitted my real age of only sixteen and gave them my true name. Confessing my true age made me a ward of the court and landed me in a mental institution, an interesting twist for a teenage girl who’d experienced all that the counterculture of the 1960s had to offer.

Jack Gardiner, the cop who’d been my arresting officer, must have seen something in me worth saving, because when I was institutionalized he began visiting me there. When it was time for me to be released, he and his wife took me in as a foster child. They were the first people who helped me feel safe enough to speak about what I’d been through, what I’d seen and heard. I lived securely with them until I testified.

As I cradled the phone in my hand, I strained to recall what I might have said to Jack all those years ago. Maybe I had told him there were other bodies. There could have been. People would often come and go from the Barker Ranch, disappearing at random. Maybe they were passing through or maybe something more sinister happened to them; Charlie and the others were obviously capable of murder.

“Dianne, there are people who may never have been brought to justice. My dog has alerted to some possible human remains.”

I didn’t respond. While in the moment I couldn’t be sure if he was telling the truth, I’d later learn this was indeed the case. In February of 2008, a team of investigators including former Inyo County detective John Little, who had worked for Jack in the early 1970s, went with Dostie and others to see if they could find anything at the old Barker Ranch.

“Do you know that undersheriff Jack Gardiner back in 1974 sent Detective Little to Barker to investigate possible human remains buried there? He was your foster father during the trial. Now why would he do that if he had nothing to base it upon?”

My hands began to sweat. For the first time in many years, Charlie’s face appeared in my mind, along with the words: “Don’t talk to no one in authority.” I felt as though I was going into a tunnel and could hear the small voice of my sixteen-year-old self somewhere in the distance.

“What do you want with me, Mr. Dostie? I don’t remember anything I might have said to Jack back then.”

“I am calling you out of courtesy. We are going back there to dig. And we are going to tape it and show it on television. If anything is discovered out there, we are going to have to trace it back to tip-offs you likely gave to Jack Gardiner.”

“Please, I am not that person anymore,” I said. “I have a family and children. I go to church. I sing in the choir. I teach autistic children, for heaven’s sake. My children don’t know anything about my past.”

“That is why I am giving you a heads up,” he said coolly. “I know you were not a killer, but you were part of something bigger than you are. And it is news and it is history. I think we are going to find things out there that are going to be gruesome. It is up to you how you want to handle this with your family.”

“Can’t you just keep me out of this?”

“I am sorry, Dianne, but from what I have read, you became a part of it the second you got on that bus with Charles Manson.”

That night I told my husband about the call. We both knew this day would come—it had to. It was a terrible secret to keep from my children, but I knew that I couldn’t bring myself to tell them any other way; I’d buried the past too carefully. Nothing about their upbringing would suggest what I’d hidden. For most of my children’s lives, I enjoyed the privilege of being home with them, taking care of them. We lived modestly but well, and I made sure the house was clean, dinner was on the table, and I was in the front row at their every school function. My children never spent a day thinking I was not there for them. But now the front was going to collapse under the weight of my former life and the shame I’d concealed for years. Now I would have to tell my children what had really happened during those two treacherous years in California.

But first I myself would have to face the truth. Memories fade, but trauma remembers. It is stored in your body, your senses, your synapses and cells. It would take strength to tell my story, but more importantly, it would take strength to tell myself, and to remember.

PART I (#ulink_139ba251-6d01-5e14-91f8-2dd67a2a4415)

1 (#ulink_4ceb973c-96e0-5646-98f7-619ad5b42394)

A MINNESOTA CHILDHOOD (#ulink_4ceb973c-96e0-5646-98f7-619ad5b42394)

This is how my real story begins. Not with sunny southern california, hippies, and drugs, but as white-bread and middle class as it gets: 1950s Minnesota.

Born in 1953, I was my parents’ first child. My father, Clarence, was a sturdy man with a wide, crooked smile. He’d followed his father’s footsteps into the house painting trade to put the food on the table, but art was his passion. He began art school after his marriage, using painting as an outlet for his creativity—house painter by day, artist by night. My mom, Shirley, was a housewife who made every effort to look her best each day and keep a lovely home. As a little girl, I would follow her around the house and try to imitate everything she did. If she was washing a dish in the sink, I would beg to be picked up. “I do it!” I would squeal until she gave me my own sponge to wash with. I was her little shadow and became a “mini momma” when my brother, Danny, and then later my sister, Kathy, were born.

When I was in first grade, my parents must have felt prosperous enough to buy a sizable house outside Minneapolis with a huge backyard. Our neighbors had a greenhouse, in which they grew all kinds of fragrant flowers. When you opened the door, you were greeted with the smell of potted perennials, herbs, and colorful annual flowers for every season. I kept an eye on my younger brother and sister while my father worked and my mother took care of the house. Kathy was a baby, so I would wheel her in her stroller across the lawn or carry her in my arms so she could smell the blooms.

My mother continued to let me help around the house, and in many ways, the housework was exciting to me. There were new household gadgets available and we had a top-of-the-line Hoover Constellation, a round, space-age-looking vacuum that was supposed to float on its own exhaust. You almost wanted to throw dirt on the floor just so you could see how it worked. Our home was always clean, but sometimes I vacuumed just to have something to do.

My mom taught me how to sew on the toy sewing machine I got one year for Christmas, setting me up at a table next to her Singer sewing machine, showing me how to thread the needle and guide the fabric to make the stitches stay straight. In the weeks that followed, she gave me scraps of fabric so I could create outfits for my dolls and little quilts. Eventually I got so good at this that she got me a pattern so I could sew clothes for myself.

From the outside, ours was a traditional family, but there was a restlessness beneath the surface. Before I was born, my father had served in the Korean conflict, and although I wouldn’t have known the difference, my mother always said it had changed him. A father’s dissatisfaction is not always expressed out loud, but it is certainly felt. Over time I came to understand how the currents of his behavior affected our family life. After coming home from work, he would disappear into the corner of the living room that he had set aside for painting, and we weren’t allowed to go near him when he was working. We had our own playroom, and whenever Danny and Kathy tried to bother him, I would catch them so he wouldn’t be disturbed. Even at that age, I understood that he needed room to create.

Even young as I was, I sensed that there was a distance to him, a detachment that made him different. When he smiled, the sun would shine, and my earliest memories are of him laughing and playing with me. But when he was depressed, it was as if the air had been sucked out of the room; he was sullen unless he was working on a project. On those sad days, he would sit quietly in a dark room staring off into space smoking cigarette after cigarette, the smoke thick in the air around him.

I must have taken my cues from my mother because she largely allowed him the space to indulge his whims. Despite his moodiness, he could do no wrong in her eyes. She interacted with him in a manner that bordered on worship and defined much of our domestic lives. She watched him closely, gauging his expressions before she would interact with him. When he got home from work she would wait until he settled in before beginning any conversation. She wouldn’t present him with our misdeeds the minute he walked in the door. Instead we were instructed to greet him cheerfully. He was the stoic king of our castle and we learned to wait until he addressed us before sharing too much with him. I wanted him to notice me, and if he did, I held on to the moment in my heart and in my memory. My remembrances of the times he would grumble and tease me about something that would make me feel bad or tell me “I’ll give you something to cry about” would be countered by his moments of playfulness even if they were not directed at me.

Perhaps because of my father’s unpredictability, my mother controlled the money in the house, as she was the more responsible person. At the end of the week my father handed her whatever money he’d earned painting houses, and I would watch as she paid all the bills. Each month my mom would make sure that the mortgage on the house was paid along with every other bill, spreading the envelopes on the table, writing out checks, and asking me to lick the stamps. Then she would take them to the post office in town to mail them.

Each week she would give my father an allowance in cash and set aside our money for our food. She did all the shopping for us and prepared all our meals. She would pack his lunch in the morning, sometimes putting a little note in his brown bag. She also made dinner every night. Though my dad always seemed busy, he did take time to have dinner with us. This was my favorite time of day because he led the discussion and included me just as if I were a grown-up.

“Dianne, what are you learning in school?” he’d ask me.

“Be right back,” I’d reply, running off to gather a stack of papers. “Look, Daddy, I got good grades on these.” I’d spread out my spelling tests, writing practice books, and math papers, showing him my schoolwork and my achievements and trying to impress him.

“That’s great. Keep up the good work.”

At dinner, my father would often bring up the books he was reading, eager to discuss them with my mother, and always somehow disappointed that she didn’t share his interest in them. For my part, I was excited in anything that interested him.

“I am reading a great book, Shirley. I think you should read it too,” he said one night while we were eating.

“You know I don’t have that much time to read,” my mother responded.

“What is it about, Daddy?” I asked. “I can read now.” I was in the top reading group in my class.

“Oh, honey, I think this is a little too old for you,” he said. “But I will tell you about it. It’s by this guy named Jack Kerouac, and it’s about two friends who go on this road trip to find out more about themselves.”

“Read it to me.” I liked hearing my father’s voice whether he was reading me Horton Hatches the Egg, which I could now read myself, or if he read to me from his own books that I didn’t really understand.

“Well, actually, I just got another book by Jack Kerouac,” he said, getting up from the table and reaching into the pocket of his jacket, which was hanging on a hook by the door. The book cover had funny writing and a man with a woman riding on him piggyback.

“This book is called The Dharma Bums,” he informed me. “Here is something he says in the book: ‘One man practicing kindness in the wilderness is worth all the temples this world pulls.’”

“I like that, Daddy.” I had no idea what it meant, but I liked that it had the word kindness in it. It must have been something good. I gave my daddy a hug, and he left the table to continue working on a painting.

Another night after dinner, he had retreated to the living room to paint when he noticed I was sitting outside the room. I didn’t want to disturb him but wanted to watch him work.

“Hey, little girl, do you like this music?” he asked suddenly. We had a small record player, and while he painted, he usually would play something from his collection.

“What is that?” I had never heard sounds like the ones coming from the record. There wasn’t really any singing, just music.

“It’s jazz,” he replied. “Isn’t it cool?”

My dad showed me the album cover. It was wild. Then he took out another record and showed me how to carefully clamp an album between my hands by the edges so it wouldn’t get scratched. He used a black brush on the record’s surface before he put it on the record player, placing the needle delicately on the first groove and inviting me to sit down with him.

We sat on a love seat next to his easel. I watched as the smoke rose from his cigarette, curling its way toward the ceiling. Every so often he would blow a smoke ring just to get me to laugh.

“Listen to this part—bah bah bah,” he sang along with the trumpet. After a while we were both bobbing our heads up and down in time to the beat. The music changed with each instrument. I liked the timpani and the cymbals; I had never heard anything like them.

“Dianne, that is Buddy Rich. He is arguably the best drummer in history.”

Now I was rocking back and forth.

After a while my eyelids got heavy. The last thing I remembered were the sands of a trumpet. In the morning, I woke up in my bed, the beat still ringing in my ears.

One morning during the early months of my second-grade year, I was in the kitchen with my mother when my father walked in.

“Do you want some coffee? I brewed a fresh pot,” my mom said, apron tied around her waist.

“Sure, honey,” he replied, and then, as if it was part of an ongoing discussion, he said, “Too bad we don’t live in California. Do you know they get to listen to jazz all the time?”

“I thought if you want to talk about jazz, the scene is in New York?” she asked.

“There is a happening scene for artists and poets in Venice Beach, California. I read about this place called the Gas House. Everyone goes there, including Jack Kerouac. They opened it last year, and it is an exciting place for artists to get started. I could get my master’s degree out there and get somewhere.”

I could see my mother’s body tense as she went about making breakfast for him. Her fingers tightly gripped the handle of the pan as she scraped his eggs onto his plate. “Look, we have a nice house here and the kids are all settled,” my mother said. “It is hard enough to take care of three kids, a house, and a husband. Can’t you do your master’s here?”

My dad relented and the conversation petered out. He continued working as a house painter during the day, keeping his desire for a change of scenery mostly to himself. While I never knew exactly what he was thinking, it was clear there were things about our life, about his life, that were not satisfying him. Still, beyond my mother, he really had no one he could talk to about this desire to break from the mold of his life that was gradually hardening around him. He couldn’t tell his father about how he felt. Grandpa’s reply would have been “house painting kept food in your mouth and kept you alive. Do you think you are better than me?”

My father remained largely silent on the matter, but none of this eased his malaise. It’s hard to say exactly what impact his reading had on him, but there’s no doubt that it influenced him and enhanced his impatience. The Beats. Jazz music. These were the first sounds of the underground reverberating out from the coasts toward Middle America and making men like my father question the choices they’d made.

The tipping point came from something that seemed innocent enough. Somewhat impulsively, my father ordered a hi-fi, a high-fidelity stereo system, by mail. He couldn’t wait to get the thing—he thought it was going to fill the entire house with sound, in contrast to the little phonograph, music from which barely carried into the next room. But when the hi-fi arrived, he looked at the bill, apparently for the first time, and freaked out at the cost. Shortly after that, he broke from their usual pattern of letting my mother handle the finances and instead sat down with her while she was writing out the bills. He turned them over and read them one at a time, eventually stopping at the mortgage bill. As he stared at it, he figured out the interest on the mortgage, becoming more and more upset. Perhaps the mortgage became a symbol of his frustration with our situation. The perpetual responsibility, the way it tied us down in Minnesota, and the fact that our house and family would apparently be his life’s work—all of it seemed to weigh on him.

“How the hell are we going to keep up with these payments?” he shouted at my mother, who was surprised that he had suddenly started caring about the money they spent. His response might also have had something to do with the books he was reading, because he was telling her that they were being pulled into, as he put it, “the establishment trap of materialism.”

“This house and this stuff is going to steal our soul!” He slammed the bill on the table and knocked the other papers on the floor.

“It was your idea to get the hi-fi,” Mom shouted back. It was not really a shout, so much as a mix of utter surprise and confusion. She never raised her voice to him, because to her, he was always right. But his reaction was puzzling, even for her. She had never wanted the hi-fi in the first place. He’d wanted to play his music as well as records by people he had been reading about like Timothy Leary and Allen Ginsberg. He wanted her to spend time with him listening to them, but she always had her hands full and only feigned interest.

This debate over our mortgage and our “stuff” went on. My father held fast to the idea that the house was a problem for us, refusing to let it go. And in the end, he impressed my mother with what she believed was his sincerity about materialism. What my father really wanted, and which we’d seen glimpses of already, was to move to Berkeley, get his master’s degree, teach art, and paint. California was where it was happening, and that was where he wanted to be.

My parents put the house on the market, and instead of a Realtor or an actual buyer, one of the neighbors approached them about the house. My father was being very impulsive and wanted to get out from under the stress of the mortgage, so when they offered their travel house trailer as a trade, he and my mother agreed it was a clever idea. That was that. It wasn’t even considered a down payment. They simply traded this lovely home with the big lawn, room to play, and a greenhouse next door, on a handshake and a whim.

Like many decisions made during those years my parents just did it and that was that. It all happened quickly, and before the end of a year that had started out calmly enough, before Christmas of the year I was in second grade, we gave away most of our things, took what we could, like my toy sewing machine, and packed the trailer. We didn’t even have anyone to tell that we were leaving. We didn’t have family in the area and I just had my teachers and friends from school. My mom even had to leave her own sewing machine behind. On the day we moved, they hitched up the trailer to our car and we all got in, resigned to the fact that we would be headed west to California and to the new life my father craved, setting out for the promised land of California, like pioneers in a wagon train.

Except that’s not what happened. As we drove away, the car kept stalling. My father finally pulled over to the side of the road and got out. We stayed in the car, huddled together against the Minnesota wind, which penetrated fiercely through the windows. In the back seat I held baby Kathy close to my chest to keep her calm as I watched my father jiggle things under the hood of the car.

My mother was already sobbing and mumbling about how she would miss her sewing machine. She vested all her regrets on the one thing she couldn’t bear to leave behind. My father was cursing and stomping around, chain-smoking. I didn’t typically see my father this angry. Usually he would withdraw rather than yell. There were times when he was drunk when he would lose his temper, and I saw him hit my mother a few times. But this felt different. It was scary to watch as he unraveled. Clearly he was upset about more than an aborted trip to California. With this useless trailer came a useless dream and more disappointment than he was ready to accept.

As my mother continued to cry, I wished that I could calm her, but I had the baby asleep in my arms. Meanwhile Danny was surprisingly relaxed considering the histrionics happening all around us. My father saw her crying and yelled at her to stop blubbering, which only made her cry even louder. At this point I think she was just exasperated. Everything was happening so fast and she hated to be so out of control.

My parents eventually figured out that we weren’t going to be taking this trailer to California and found someone to tow us to the nearest trailer park, which was in a suburb south of Minneapolis called Burnside. Mostly dirt and mud, the trailer park was not really set up for permanent living, but we stayed where we landed, next to a few other trailers that must have met the same fate.

About twenty-three feet long and without many amenities, our trailer was not set up for such permanent living either. The five of us learned to squeeze into the small space, my father still chain-smoking in our tin-can home. The trailer had a galley kitchen and a living room, where we put the baby’s crib. Danny and I had bunk beds in the back of the trailer and my mom and dad had their own little room. We had a small living room area where we could play games at night and do homework. We had a potbelly stove at the entrance to the trailer, on which I could easily iron my hair ribbons. All I had to do was run them along the heated top and they came out wrinkle free.

We all did our best to settle into Burnside. My brother and I were enrolled at a funky little country school and had to take a bus, where I spent the second half of second grade and the first half of third grade. I got used to the situation, but my mom still missed her sewing machine. She never mentioned the house and her stove, but we all knew that she missed them as well. The impulsive trading of our house had been done with a handshake, and since we were not that far away, one day my parents went back for some of the belongings they’d left behind. But when they arrived, no one was home. The new owners were not just out for the day—it appeared they hadn’t been living there for a while. There were no belongings to reclaim, no house to trade back, and my parents had no one to blame but themselves. It wouldn’t be the last time my parents’ idealism was betrayed by reality, or the placing of trust in the wrong people. But that didn’t mean they’d learn from it.

We lived in the trailer park until my father found a patron of the arts to support his painting. He had been searching for someone to believe in his art for quite a while, so meeting this wealthy art-loving couple was the break he had been waiting for. They owned a gallery and asked my father to provide them with some paintings. When they found out about our living situation, they invited him to become a regular artist for them. They loved his style and couldn’t stand that my father was an artist without a studio or a proper home. The arrangement would be that he would provide them a certain number of canvases for the gallery to sell and he could work on other projects if they did not conflict.

Even more generously, this new couple set my father up with his own studio where he could paint and create, and placed us in a small house with a nice yard where we could live more comfortably. Kind as these actions were, they were also part of the patron’s role. Gallery owners were supposed to take diligent care of their artists. When word spread of their generosity, other artists would be enticed into joining their stable.

All of us loved our new little house, and once again it felt like home, but more important, it felt like home to my father, a place where he could pursue his art to his content. Gradually his fixation with moving to California abated, and life returned to some sort of normal. At least for a time.

2 (#ulink_9e418b1f-f47b-5314-bc7d-1f152346e336)

FAMILY MATTERS (#ulink_9e418b1f-f47b-5314-bc7d-1f152346e336)

With my dad occupied painting for his patrons, our family settled into a routine of sorts, and he threw himself into his work. He spent the days in his studio, which was filled with supplies, canvases, and a drafting table. It smelled like a combination of linseed oil, India ink, cigarette smoke, and creativity. He smiled and listened to jazz records while he worked

Christmas Day during my third-grade year, when we lived in this little house, was the best time I can remember ever having with my entire family. That morning I awoke to the smell of fresh cinnamon buns that my mother had made from scratch and raced Danny downstairs to see what was under the tree. Beside the presents from Grandma, Grandpa, and my parents that had been under the tree the night before, there was a new one. There it was in all its glory, the Barbie Dreamhouse I had wanted—a gift from Santa Claus.

I ripped through my other presents, opening gifts from my father’s parents from Milwaukee. Our only close family, they would be visiting us in the summer now that we were settled into a proper home. Finally, I got to a present that was marked To Dianne, from Dad. I tore into the package and couldn’t believe what was in it. My father had made a bed for my Barbie to fit into the house that Santa had sent me. On the verge of tears with excitement, I went to hug my dad; always a bit awkward at affection, he turned away, giving me a sideways hug.

Later that day, we had a Christmas dinner with some of my parents’ friends. My parents had settled into our new home, our new life, and had added new people. My father had collected a new crowd matching the life he was creating and his new persona as a professional artist. Around the table this year was an Ethiopian artist who wore a dashiki. The dark-skinned man chewed on toothpicks made of orange sticks and used them to clean his teeth. He told us about how in his country they did not use forks and knives when they ate. Instead, he explained, they used a special bread to scoop food into their mouths and into the mouths of others sharing the table. This Christmas meal would be strictly American, and he was looking forward to our traditions. My parents were also friends with a Ukrainian couple who joined us. They brought us pysanky as a gift and explained that they were typically for Easter. These were eggs decorated with Ukrainian folk designs. The wife promised to show me how the eggs were created during the holiday.

It was a remarkably special day, but sadly it was also one of the last of its kind. We never were that happy and secure again in Minnesota. Things always had a way of changing, especially in a family like mine.

My parents seemed content with their friends, but my mother encouraged us to keep in touch with my father’s parents as well. Sometimes I would hear them arguing about having them come visit us, with my mother insisting it was good for children to know their family and my father saying he didn’t need to see his parents. During the summer between first and second grade my grandparents had come out to visit us back in our big old house. It was a fun visit, and I’d enjoyed having them around, eating meals together and going places. I was proud when during dinnertime one evening, my father hung a portrait he had painted of me on the wall for everyone to see. My dad and grandpa worked on the car together and we all seemed to get along.

Still, in the aftermath of the visit, there seemed to be some residual tension between Grandpa and my father. It was obvious that my grandparents didn’t share my father’s interests, and that Grandpa in particular never liked my father’s desire to be an artist, looking down on him for it. The following summer we didn’t see my grandparents, and I don’t think my parents ever let them know that we had been living in a trailer park. But now that we were back in a real house and my father was becoming successful, my mother began encouraging him to contact them again.

“The children miss their grandparents, Clarence, we should invite them out.”

“I’m too busy to take the time with them. Besides, I am finally enjoying myself,” he said. Father and son exasperated each other, which made it difficult for the two wives, who made it their mission to keep their husbands happy. Any tension that could not be relieved by copious amounts of beer would have repercussions for both women after dark.

“Your mother called and really wants to see Dianne. She said she will be all grown up before you know it. Your father agrees.”

“Well then, maybe she could go to see them,” he suggested.

“By herself?” Mom asked, not so sure she should allow my unsupervised independence. She had grown to love her mother-in-law, who had become something of a Rosetta stone to help her understand her son, but she still had reservations about sending her daughter so far away on the train.

“She’ll be fine, and we can have a break from at least one child for a few weeks. And it will get them off our backs for a while.”

And so, in the summer of 1962, when I was nine years old, my parents made plans for my visit to Wisconsin. When my parents told me I would be visiting my grandparents in Milwaukee, I wasn’t even scared of being by myself, just excited to have all the attention without my brother and sister being around all the time. I planned everything out. The first things I carefully packed were my Barbie and Ken dolls, along with the clothing I had sewn for them. I didn’t want to go on this adventure without them. Like me, my Barbie had red hair that she wore in a bouffant hairdo. I wrapped her hair in tissue so it wouldn’t get mussed during the long train ride. I dressed Ken in a makeshift suit so he would be properly attired for the visit. I also packed some of my favorite books, National Velvet and Nancy Drew, my hairbrush, and some Max Factor lip gloss my mom let me buy. It was shiny but tasteless, and it made me feel beautiful. Mom helped me carefully fold my clothes, as well as some pink clip curlers for my hair, a robe, and a pair of pink fluffy slippers.

When I got to Milwaukee, my grandma and grandpa met me at the station.

“You’ve gotten so big,” Grandma said. “You look so grown up since we saw you last.” It had been two years and I had been more like a baby during their last visit. Grandma pulled me into a hug against her soft chest; she smelled of a combination of lilac powder and beer.

Grandpa patted me on the head and grabbed my bag. He was about the same height and size as Grandma, but his arms were much stronger. The years of house painting had preserved a muscularity more common in a younger man. Now they owned an apartment building together and he did all the maintenance while Grandma collected the rent and kept the tenants happy.

When we got to the building, they gave me my own room across from theirs and Grandma helped me unpack. We put my Barbie, Ken, and books on the oak highboy next to the bed that they said used to belong to my dad. Then we carefully placed my folded clothes in the now-empty drawers. I thought about my dad’s clothes in those same drawers when he was a little boy. Sitting on the highboy was a framed picture of Grandpa and me taken during their last visit.

When we got settled, Grandpa and Grandma took me right across the street to a bar.

“Hey, Dutch,” Grandpa said, “two brews for us and a Shirley Temple for our little Shirley Temple.” I liked that they were showing me off. This would not be the only time that they took me to the local bars. They liked their beer and I liked my Shirley Temples. The room was smoky and dark, but I liked that they let me be in there with the grown-ups. The later it got, the louder they got. Then we walked home and Grandma helped Grandpa into bed.

That first night after I had gone to bed I heard Grandpa rustling around in the kitchen. I found him by himself at the small dinette with a glass of milk and a box of graham crackers. He crumbled the graham crackers into the milk until it was thick as pudding.

“You want some, little girl?” It looked lumpy, but I was happy he was offering me some of his snack.

“Sure.”

“Get a glass and I will show you how it is done.”

I poured some milk from the bottle in the Frigidaire and grabbed two graham crackers. “You got to have just the right number of crackers to make it good,” he explained. It seemed like a delicate operation, but I got it right the first time.

“You’re a natural,” he said. We spent the next twenty minutes in silence as we slurped down our graham cracker mush. “You ought to get back to bed. We are taking you to the zoo tomorrow.” I was so excited to go that I didn’t even plead to stay up later with him. I shuffled away in my pink shag slippers and went right to sleep.

The zoo was everything I’d hoped it would be, and I spent the next few days after that with Grandma, going to an elderly neighbor’s apartment to check on her and taking a trip to the salon, where I got a rather unfortunate perm. One morning at breakfast, Grandma told me that this day would be a bit different.

“You’re going to spend the day with Grandpa today,” she said, giving me a hug. “Be good and do what he says. I have some shopping and errands to do. I will be back for supper.”

I was eager to spend the day with my grandpa—watching TV, reading the funny papers, and crumbling graham crackers into our milk. We sat together on the couch for a while and I leaned my head on his shoulder. We were watching a Western. It was such a treat to watch a television that I didn’t mind that it turned out to be old Zorro reruns. Grandpa smelled like green grass. He wore a kind of aftershave called something like old bay rum. I could have stayed like that for hours.

“I have an idea for what we can do together.” Grandpa broke the silence.

“What’s that, Grandpa?” I replied excitedly. “Do you want to play Parcheesi?” We had been having a running competition.

“Let’s take a bath together.”

“A bath?” The idea seemed kind of strange. I had never taken a bath with my father or even my brother except when we were little.

“It will be great,” he added. “It is a natural thing to do and you will like it. It is how I like to relax.”

He turned on the faucet while I went to my room to put on my bathing suit.

“You won’t need a bathing suit in a bath. You can take off your clothes in here,” he added, gesturing for me to come into the bathroom with him.

When the bathtub was full, he took off his clothes and got in. Then he told me to take off my clothes and join him. I took off my shorts and top and folded them. I put them on the floor in the corner by the sink. The last thing I took off were my panties. I got in the warm water facing him and it felt good.

“See how relaxing this is.” He sat in the water with his eyes closed for a few minutes with his hands along the tub rim. I closed my eyes too but peeked out of one open eye. I watched him put his hands under the water. His breathing changed. It became deeper and faster. Then he opened his eyes and grabbed my hand. I barely moved.

“You know, Dianne, you are old enough now to know where babies come from.”

“I do know where they come from, Grandpa,” I proudly answered. “God puts a seed into the mom’s belly and the baby grows in there.” I thought I was clever to know this fact already. Grandpa laughed and held my hand more tightly.

“That is not how the seed is put into the mom, Dianne. There is more to it and I need to tell you the truth.” He stood up and his body looked different than what little I had seen when he got into the bath. His boy-part was big and he touched it with both his hand and mine. The skin felt warm and soft. When he began to move our hands over what he explained was what the man used to plant his seed in the woman, I pulled my hand away. I couldn’t picture that what he was saying was true. How could that go into what I believed was a very small hole?

He explained how the man and the woman would make the seed come out and then demonstrated with his hand. “It is just like blowing on a dandelion.” Then this milky liquid dripped out from between his fingers as he made a heavy sigh. It landed in the tub, so I didn’t move. I didn’t want to be near the seeds. He got out of the bathwater and wrapped himself in a towel. When he left the bathroom, I gathered up my clothes and quickly got dressed. I couldn’t wait to tell my best friend back home what I had learned.

Grandpa did tell me not to mention my lesson to Grandma. He said they disagreed on when a girl should learn the important facts of life. I promised.

The train ride home felt different than the trip there. I left Barbie and Ken in their box, but now they faced each other in case they wanted to make a baby.

My mother picked me up from the train, and as soon as we got home I asked if I could go to see my best friend, Emily. She lived down the street, and since she was a late-in-life child with much older siblings, she had the best of everything, including a playroom that was just for her.

When I arrived, Emily hugged me as if I had been gone forever and we went into the playroom. We took out all the dolls and clothes and set out to create their lives in miniature.

“I know how babies are made,” I told Emily matter-of-factly.

“I do too,” she bragged. She explained the same “God planting the seed” story that we both must have heard at church, and so I decided to show her with our dolls.

“That can’t be true.” She seemed shocked.

“No, it is true. My grandpa took a bath with me and showed me how the man makes the seeds in his penis that are planted inside the woman. He said it was time for me to learn the right way.”

“Did you see his penis?” Emily asked with her eyes opened wide.

“Of course, I did, silly. How else would he have shown me how it all worked?” Emily disappeared for a few minutes, and I continued to pretend that Barbie was cooking a casserole in the Barbie kitchen. After a while Emily returned with her mother, a stylish woman who wore her hair piled up on top of her head like a movie star.

“Dianne, come join us for a snack,” she said, guiding us up to the kitchen. She had made peanut butter and jelly sandwiches on Wonder Bread and added Bosco to our milk. We chewed on our sandwiches as we had many times, but Emily’s mother kept staring at me.

“Dianne, Emily told me about what happened at your grandfather’s house. You do know that grown men are not supposed to take baths with little girls and tell them about where babies come from?”

I knew it felt weird when it happened, but it was my grandpa, and if he thought it was time for me to know the truth, then it must have been time.

“Dianne, you need to tell your mother what happened at your grandpa’s house. She needs to know.”

I had not thought about telling my mom. Even though I didn’t think much of what had happened, I had a feeling that telling my mother would be embarrassing.

“If you don’t tell her, I will,” Emily’s mother insisted. I knew that she would too, because she and my mother were friends who often went to each other’s houses for coffee.

“Okay, I will tell her,” I promised.

When I got home my mother was in the kitchen by herself. She was making soup and asked me if I would like to stir the pot.

“Can I talk to you, Mom,” I said softly. She turned off the stove and we went into the dining room.

“If it is about your hair, I already told Grandma she should not have permed it without asking me first.” She reached for my hair. I started to cry. “It will grow back soon enough,” she reassured me. This only made me sob more.

I told her about Grandpa and the bath and watched her expression change. Tears streamed down her cheeks and she held me close. We both cried.

“That wasn’t your fault,” she reassured me. I didn’t understand what she meant. But I knew by her reaction that something bad had happened, something that could never be taken back.

Later that night I overheard my parents arguing. I knew it had to do with my grandpa telling me about where babies come from. I was very confused. Why was it wrong for my grandpa to tell me the truth? He didn’t make it sound like it was wrong. Maybe I did something wrong to make everyone so upset. I wished I had never said anything to Emily.

The next day I overheard my father calling my grandpa on the phone. I wasn’t even trying to listen, but he was yelling for most of the call. I could hear only his side of the conversation, but he seemed very angry. “It’s me. You know why I am calling. You expect me to believe you over my own child? I know what a sick old bastard you are!”

I wasn’t used to hearing my father curse since the car broke down, and especially not at Grandpa. But I knew my father meant what he said. I felt awful about Grandpa and somehow felt sad for Grandma. If I hadn’t gone to see them, no one would have been upset. I ran into my room before my dad could see that I had been eavesdropping on his phone call.

Like most kids who have been sexually abused, I didn’t understand at the time what was going on or how I’d just been violated. Still something felt off, and I felt different—about my grandpa, about myself. Something had changed, I knew that much, even if I didn’t fully understand what it was. Thankfully, unlike what happens in many situations of sexual abuse, they didn’t blame me, but they didn’t know how to talk to me about the abuse either, so they avoided it. And without more reassurance from them, I fully blamed myself and dealt with the consequences of that guilt for years.

But guilt was just one piece of my emotional chaos. Though I wouldn’t understand it fully until much later, this upsetting and disturbing encounter enabled years of sexual confusion to come, as a part of me would spend the rest of my youth seeking a level of safety in the wrong people and for the wrong reasons. Sexual abuse creates an emptiness in the darkest places within. From now on, things would never be the same for me.

3 (#ulink_a7deaf95-eb64-5e1f-bc30-c68ee5c17c0e)

ONE STRAY ASH (#ulink_a7deaf95-eb64-5e1f-bc30-c68ee5c17c0e)

As fall of 1962 rolled around, my parents and I were glad to put the events of the summer behind us, and with the new school year under way, by all appearances things had returned to normal or whatever our version of that was. Beneath the surface, though, all was not well with us. My father was becoming restless once more. He wasn’t speaking about California or philosophy or change, but that didn’t stop fate, or something like it, from intervening.

One night before leaving his studio my father must have put out a cigarette in a trash can. The next day we went to his now-charred sanctuary to dig through the rubble and ashes to salvage anything of his work. We found scraps of his illustrations and charred canvases. I found the portrait of me that used to hang in our big beautiful home completely ruined and burned. The only thing I recognized was some of my hair and the wicker chair I had been sitting on when I posed for him.

Only in retrospect did I question whether he might have thrown the cigarette in the can on purpose. He’d been sullen ever since the confrontation with Grandpa, and while he’d continued to paint, he’d been melancholy and lacking in purpose, at least in part because he had been forced to accept that his own father was a miscreant. As I would learn years later, there had been other suspicions about his father’s behavior, but people either didn’t believe it or looked the other way. It wasn’t until years after Grandpa’s death that other people spoke up about how he’d isolated Grandma from her own relatives, verbally abused her, and had been caught molesting the daughter of his own brother.

My father may have been angry at his father, but he also never seemed to like it when things were going too well. He was a five-pack-a-day chain-smoker, so he should have known better than to put his cigarette out where it could set things ablaze—unless of course that was what he wanted to do. I’ve long wondered if my father, the man who traded our house for a trailer, was looking for another way out of a normal family life when he left his studio that night.

Whether the fire was an accident or not, the blaze accentuated how my father was outgrowing his surroundings. Around the same time, he started receiving some backlash for his artwork, which had begun to border on the controversial. We belonged to a Lutheran church that had always welcomed his contributions, at least until he painted a dark-skinned Jesus. This caused a scandal among the staid Christian community who couldn’t imagine such a heretical statement. Then they came to our house to try to force a greater tithe, which only upset my father more.

After the fire and the rejection from the church, my father fell into a deep depression. I would overhear the grumblings after my parents thought we were all asleep. He made it clear the drive and desire to go to California had never disappeared. He implied that it was our fault that he had been forced to settle in Minneapolis again after his first try for freedom. His unhappiness was visible on his face and in his body, the tension trapped in his muscles. At first his books and music had fanned the flames of his wanderlust. When they could no longer distract him, he focused on blaming the people of Minnesota for being too small-minded to “get it” or to “get him.” My mother, in her reverence for my father and his genius, would agree with him, while encouraging him not to make any more waves.

My father had a complex relationship with the church. A seeker by nature, he was inspired by the teachings of Christ. At one point he had even tried studying for the ministry but had felt stifled by the dogma of Christianity. The people of our church made sure there was no home for him there. My mother had been brought up in a Norwegian family with a conspicuous lack of outward affection. She had a strong faith in God but was looking for a way to define this that was inclusive and loving. She seemed torn between pleasing my father by being avant-garde and fitting in with the church crowd. She liked the artists in our home but also enjoyed the community the church had afforded her.

But my father’s depression this time was not just petulance at things not going his way. He was drinking and staying out until all hours. My mother covered for him and told us that he was just working through the loss of his studio and we had to give him time. Then I would hear her cry at night while I listened to the clock ticking the seconds until dawn. I didn’t know how to comfort her, so I would bury myself in cleaning and vacuuming the house. We didn’t have any relatives to visit, and our eclectic mix of creatives must have sensed the tension—they no longer came around.

We had only one car, and my mother encouraged my father to take it when he needed to get away. He would often stay out late, eventually stumbling home sometime during the early morning hours. I have always been a light sleeper, so I would mark the time in my mind and then listen for any conversation between my parents. There typically wasn’t much. My mother would let Clarence into the bed or if he passed out on the couch would cover him with a blanket. She was desperate for him to show some sign of happiness. She made few demands and gave him a very wide berth as she went to her now full-time job as an executive secretary by bus.

I am not sure how long this went on, but finally one night he didn’t come home at all. I heard my mother toss and turn, but she didn’t get up. The next day we all went to school as usual, and she left for the bus.

That night at dinner there was no sign of Clarence. My mother’s red-rimmed eyes betrayed that she had been crying. She still held her composure. “Children, your father has decided to leave us. He is going to California to pursue his art studies.”

Danny didn’t say anything and Kathy started to cry, mostly because she was confused. She was too young to fully understand what was happening and knew only that Daddy wasn’t going to come home. I wanted to tell her that things would be much as they were, but I knew that she wouldn’t understand what I meant. I simply held her to me and calmed her enough so I could ask my mother some questions.

“What does this mean for us?” I asked in my most grown-up tone. There had been signs of his unhappiness, so I wasn’t completely surprised; I put together that we were living in a house that was given to us by Clarence’s art patron and that we would have to leave. I was right, of course. My mother explained that we would have to move, but that when our dad had time to sort out his career and his work after the fire, we could be a family again. That seemed simple enough and Danny and Kathy took it at face value, but all I heard was that he had left us. He was taking time away from us to sort out his life—but we were his life.

My mother got some boxes at the local grocery store and told each of us, in a line that was becoming increasingly familiar, that we could bring only the things that were necessary or really important to us. Once again, we were paring down our belongings and starting over in a new place. I helped Kathy pack her things into a box. If Kathy could stay busy, she might not realize that we were starting over. Perhaps she could be more resilient if I showed her that everything would be fine.

“How is the packing coming?” my mother called from her bedroom. I walked over to her room, where she was putting some photo albums into a box and covering them with a few shirts my father had left behind, holding one of them up to her cheek. I sat on her bed and said nothing.

My mother was the first to break the silence. “Dianne, your father left us for another woman,” she said, breaking down in tears. “It’s my fault that he is leaving us.”

I hadn’t seen my mother cry this way before. I was used to her sobbing out of frustration and screaming at us when we were out of control, but I had never seen her in such deep pain. As I’d learn later, the other woman was my mother’s best friend, Barbara. My father had been living a double life for quite a while, it turned out. My mother took it as a rejection of her as a woman and a wife, but apparently we were all holding him back from the life he wanted.

As we sat folding sweaters and wrapping paper around the few knickknacks that had survived our many moves, my mother told me how she found out about the affair.

“Remember the morning your father didn’t come home,” Mom said. I nodded and listened, even though I wanted to put my hands over my ears. That morning did stick in my mind because my mother was very upset and concerned. My first thought was to worry that he was in the hospital, but my mother never mentioned anything like that. She just got dressed for work and caught an early bus.

“There I was on the bus on my way to work and I saw our car in Barbara’s driveway.”

“There could have been a lot of reasons for him to be there, Mom.” I was trying to make her feel better, but I wasn’t even sure what the problem was.

“I caught your father and Barbara in bed together,” she went on. Now her tears were streaming uncontrollably. I sat there stunned. While I was pleased that I was enough of a comfort that she would confide in me, I would have preferred not knowing all the dirty details. I didn’t understand sex beyond what my grandpa had told me, and that was frightening enough. It scared me to know that sex had played a role in why we were now living without my father. I had never thought of my mother and father in bed together, and the thought of him with another woman made me sick. I put my arms around her and held her while she gasped for air. After she calmed down, we both finished putting some of my father’s remaining items into a box and taped it shut, the reality sinking in that he’d left my mother, Danny, Kathy, and me alone in Minneapolis with little money and no car. From that moment on he was not my father, he was “Clarence”—and I would never forgive him.

The life we’d been living came to a sudden and abrupt end. We moved into the projects and my mother went to work full-time, but it still was not enough for a single mother to support three children, so we had to go on welfare as well. At age ten, I was now the wife to my mother as husband. I would do the wife and mother things for the family while my mother went out into the world to earn the money to take care of us. While I’d always been a mini momma to my siblings and helped with housework, now I felt a whole new kind of responsibility toward my family. Almost overnight I grew up. I no longer had time for the fantasy world of Barbie and Ken. The normal interests of other children my age were no longer important. It was my job to step into the adult role left vacant by my selfish and unreliable father. I played my part with fervor and felt much older than my ten years.

Of course, I didn’t understand the full extent of the toll this would take both on me and on our family. But though I couldn’t articulate my feelings, I somehow understood that our family possessed an instability that was different from others. In 1963 parents weren’t splitting up every day. There weren’t many homes without fathers. We had all held on through the moves, the trailer home, the burned studio, but now we were fragmented. Clearly family was a fragile thing, and preserving that sense of family meant finding it within myself and others—because my father could not be trusted.

Strange as it may sound, our time in the projects and on welfare produced some of my best memories of growing up. This was low-income housing, but it was not a bad or unsafe place to live. We didn’t have very much, but we had a home that was not living under a gray cloud. We could rely on my mother’s moods from one day to the next and this gave us some respite.

My mother was working and making her own decisions, so one of the first things she did once she could afford it was buy us a television. Not only was it a luxury purchase from money she had saved, it was a clear sign she was exerting her independence. Clarence would never have allowed an “idiot box,” as he called it, saying it would rot our minds. There weren’t many things to watch in 1963, but it was a great distraction that we could all enjoy. It was also a connection to the world. Similarly, my personal prized possession was a white transistor radio. The Beatles had just crossed the pond and were filling the airwaves with excitement beyond anything any of us had heard before. We all sang “I Want to Hold Your Hand” to the radio that became my constant companion.

At school, no one said anything about my family’s financial status. My mother made sure we were all clean and nicely dressed every day just like any other student. Instead they focused on what they said were my squinty eyes and Big Bertha butt. I think sometimes children have radar for locating the weakest animal in the herd. They zeroed in on me, the big-butt, squinty-eyed project kid whose father didn’t even care enough to stick around.

During that first year without my father, being second-in-command at home gave me the confidence that I couldn’t find in school. My mom confided in me and continued giving me extra responsibilities, so that I felt important in our home. Eventually that confidence spilled over to school as well. The 1964–1965 school year began with my blossoming into a great student, with a love for science in particular, working with Bunsen burners and making things out of pipettes. I even had a boyfriend. Because the projects were a diverse place with different kinds of people, I met a young black boy named Michael who was also very studious and lived nearby. We would take walks together after school and talk about everything under the sun. We would listen to Wee-Gee, WDGY on the AM dial, and make lists of our favorite songs.

Meanwhile, my mom was relaxed and focused on us. Even when she dated a few men, it was evident that my sister, brother, and I were her top priority. We had fun together. One night in June of 1965, we all piled into my mother’s bed to watch The Ed Sullivan Show. Herman’s Hermits were making their debut, and I was so excited I was squealing. Then my mother started to giggle. Then she started to laugh. Then she laughed so hard I thought she was going to pee her pants. She was laughing so much she could hardly breathe.

“Mom, why are you laughing?” I started laughing with her, and Kathy and Danny joined in. “Come on, what is so funny?”

“Don’t you see them?” she asked.

“What do you mean? That’s Herman’s Hermits. Aren’t they fab?”

“Fab? They’re hilarious,” she snorted. “Look at those mop tops!” It was so funny seeing my mother in hysterical abandon that I couldn’t take offense at what she was saying about my new favorite musical group.

Ultimately, though, all the independence I’d achieved started to change things with my mother. Every night my mother’s ritual would be to kiss us good night. She would go room to room. One night she skipped me.

“Mom, you forgot to kiss me good night,” I called to her at her apparent oversight.

“No, I didn’t,” she replied. I lay there for a few minutes contemplating her returning for our nightly ritual so I could go to bed.

“Mom, are you coming?” I shouted again.

“Dianne, you are too old to kiss good night. It is time for you to go to sleep on your own.”

I was dumbfounded. I couldn’t believe that my mother had decided I didn’t need my good-night kiss. This had been our routine since I could remember, and now because of some arbitrary passage of time of which I was completely unaware, this expected sign of love and affection would be withheld from me. At the time, I was deeply wounded, but I swore to myself that I wouldn’t show it. I was eleven years old, but I’d felt older than my age ever since my father had left home. Now, as the tears rolled down my cheeks, I decided that if this was what was expected of me, it was time to grow up. Only babies needed good-night kisses from their mothers.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/dianne-lake/member-of-the-family-manson-murder-and-me/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Dianne Lake

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Исторические детективы

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Following the recent death of Charles Manson – the leader of the sinister 60s cult – Dianne Lake reveals the true story of life with Manson and his ‘family’, who became notorious for a series of shocking murders during the summer of 1969.In this poignant and disturbing memoir of lost innocence, coercion, survival, and healing, Dianne Lake chronicles her years with Charles Manson, revealing for the first time how she became the youngest member of his Family and offering new insights into one of the twentieth century’s most notorious criminals and life as one of his “girls.”At age fourteen, Dianne Lake—with little more than a note in her pocket from her hippie parents granting her permission to leave them—became one of “Charlie’s girls,” a devoted acolyte of cult leader Charles Manson. Over the course of two years, the impressionable teenager endured manipulation, psychological control, and physical abuse as the harsh realities and looming darkness of Charles Manson’s true nature revealed itself. From Spahn ranch and the group acid trips, to the Beatles’ White Album and Manson’s dangerous messiah-complex, Dianne tells the riveting story of the group’s descent into madness as she lived it.Though she never participated in any of the group’s gruesome crimes and was purposely insulated from them, Dianne was arrested with the rest of the Manson Family, and eventually learned enough to join the prosecution’s case against them. With the help of good Samaritans, including the cop who first arrested her and later adopted her, the courageous young woman eventually found redemption and grew up to lead an ordinary life.While much has been written about Charles Manson, this riveting account from an actual Family member is a chilling portrait that recreates in vivid detail one of the most horrifying and fascinating chapters in modern American history.