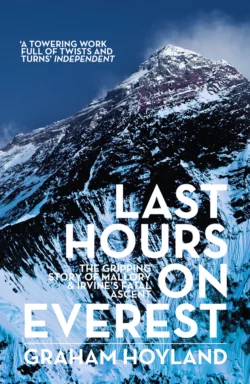

Last Hours on Everest: The gripping story of Mallory and Irvine’s fatal ascent

Last Hours on Everest: The gripping story of Mallory and Irvine’s fatal ascent

Graham Hoyland

An expert mountaineer cracks Everest’s most intriguing mystery - did Mallory and Irvine reach the summit before they perished on its slopes?

On the 6th June 1924, mountaineers George Mallory and Sandy Irvine perished in their attempt to reach the summit of Everest.

Obsessed by uncovering what happened, in 1993 Graham Hoyland became the 15th Englishman to climb Everest. His investigations led to the finding of Mallory’s body; it will be his evidence that will recover Irvine’s.

‘Last Hours on Everest’ meticulously reconstructs that fateful day. Combining his own expert insight with the clues they left behind, Graham Hoyland at last answers the most intriguing of questions – did the two men actually reach the top of Everest?

Contents

Cover (#u0553975d-9c19-5588-92d8-d3851714f638)

Title Page

Preface (#ulink_b09e8d1b-d7ec-5054-b7b9-5413c7216f8b)

Prologue (#ulink_18fdf758-a490-5dbb-9d00-161b16e76090)

1 Start of an Obsession (#ulink_ef7defd3-41b2-5a7c-87f6-635b7050e480)

2 Getting the Measure of the Mountain (#ulink_01e4e77b-8a5d-5d08-b71d-b9eed1aa6e98)

3 Renaissance Men (#ulink_86bd9722-ac74-57b8-81cf-4b23da4d1844)

4 Galahad of Everest (#ulink_bb67df26-5dff-5a87-8756-df383e9df79f)

5 The Reconnaissance of 1921 (#ulink_af799936-8373-5da5-862a-9226b3ec0687)

6 The Expedition of 1922 (#ulink_c45c8bfa-fbb7-5793-b187-3627c3f71769)

7 1922, and the First Attempt to Climb Mount Everest (#ulink_3a3b698c-0aa1-55ea-af7b-6e208c535e2b)

8 ‘No trace can be found, given up hope …’ (#ulink_7c523057-f810-574c-99d9-03ad032ade04)

9 A Pilgrim’s Progress (#ulink_8338429b-aae8-57f7-8d5c-9be93407e1e9)

10 John Hoyland and a New Clue (#ulink_36ee1d9d-1d6f-573a-946d-1007de9044fd)

11 I First Set Eyes on Mount Everest (#ulink_e774a979-b37e-5dfb-9c8b-17d6076564b0)

12 High Mountains, Cold Seas (#ulink_f2ce5fb0-3ad3-52ae-9b86-c07ddc400071)

13 The Finding of Mallory’s Body (#ulink_8511c635-9e20-55d5-aa3d-603e7328578d)

14 When Did Everest Get So Easy? (#ulink_9e112482-5235-5a17-a614-b6242746290d)

15 Why Do You Climb? (#ulink_78364cca-7de1-582b-9a50-5fa06c4b5119)

16 What Does Mount Everest Mean? (#ulink_e76a37ab-0f57-519b-b61c-600569a73962)

17 The Theorists and Their Theories (#ulink_40663a6e-4eca-534f-a85b-76c3578aa9f8)

18 Wearing Some Old Clothes (#ulink_fa06a0fd-17f2-5211-9f8c-833cf689cece)

19 Perfect Weather for the Job (#ulink_2c0874a4-feb5-5bf1-8171-03b226312dcd)

20 Utterly Impregnable (#ulink_58053ced-6940-53f0-906d-dfae1113e58e)

21 What Was in His Mind? (#ulink_205a46d8-14a9-50e1-a4e3-34a8ef432bcd)

22 Weighing the Evidence (#ulink_ee61653d-b146-5764-880d-b56bc6faac69)

23 The Last Hours (#ulink_89ac89b4-4d3f-540a-b440-4d68c1c88a4c)

Postscript: Goodbye to Everest (#ulink_15e4ebd8-9d1d-5130-a94b-e45190149e0b)

Chronology (#ulink_5152f115-a5a9-590c-9273-dd4d9120fb96)

Notes (#ulink_7d027db8-c7e8-5c0b-9135-eb24eace2eea)

Credits (#ulink_a28dd1d4-9aa8-52d0-ba84-80ea071d343a)

Acknowledgements (#ulink_c0a43ac7-fb35-5e2f-8d2d-d38c01c81754)

Picture Section (#ulink_e838afd7-c9b1-5e2f-8242-a5428ddd720b)

About the Author (#uac5cb4bc-ba80-5f6e-ac40-eb6c44e26e7c)

Copyright (#ulink_d7506bf8-c901-5ac2-b917-304819a0398e)

About the Publisher (#u20b49074-bef2-5981-a595-21ac95413c74)

Preface (#u06d386a6-a3b9-55cb-b70d-5a5c09aa74c9)

Mount Everest has been my arena. I have spent over two years of my life on the mountain, returning there again and again. I am drawn back because I see there the extremes of human experience played out in the most dramatic surroundings: greed and betrayal, loyalty and courage, endurance and defeat. It is a moral crucible in which we are tested, and usually found wanting. It has cost me my marriage, my home and half my possessions. Twice Everest has nearly killed me. But I find it utterly addictive. And so did George Mallory.

This volume is going to add to the vast pile of books about Mount Everest, a pile that must now must be higher than the mountain. I make no apology for this, for I think I have finally solved the mystery of what happened there on 8 June 1924, when Mallory and his young companion Sandy Irvine disappeared into clouds, climbing strongly towards the top.

My family had a unique relationship with Everest, and this helped me to climb the mountain and to find clues to what happened to Mallory, its most famous opponent. I spent a long time looking for his body, and then I spent a long time trying to prove that he climbed his nemesis before it killed him.

This is going to be a personal story, a detective thriller, a biography and a history book.

I hope it will set the record straight about how Mallory was found. It is about other things, too, such as why we believe in gods and mountains.

Most of all, though, it is about my life-long hunt for an answer to the greatest mystery in mountaineering: who first climbed Mount Everest?

Prologue (#u06d386a6-a3b9-55cb-b70d-5a5c09aa74c9)

Dawn broke fine on that fatal day. A couple of thousand feet above the tiny canvas tent the summit of the world’s highest mountain stood impassively, waiting for someone to have the courage to approach.

Inside the ice-crusted shelter, two forms lay as still as death. Then there was a groan, a stirring, and eventually the slow scratch of match against sandpaper. Low voices shared the high-altitude agonies of waking, the heating of water and the struggle with frozen boots.

As the sun rose through wisps of cloud beyond the Tibetan hills to the east, one of the men emerged through the tent flaps. It was a fine morning for the attempt, with only a few clouds in the sky. The two of them stood for a while, shuffling their feet and blowing into their hands. Inside the tent lay a mess of sleeping bags and food. The men lifted oxygen sets onto their backs, then turned towards the mountain and stamped off into history.

Seventy years later, above the Hillary Step on the other side of the mountain, I was teetering along the narrow icy summit ridge between Nepal and Tibet, between life and death. The sun was intensely bright and the sky was that deep blue-black of very high altitudes. All around were the icy fins of the world’s highest mountains. And somewhere along that ridge I experienced one of those existential moments that gives you the reason for gambling with your life. The intenseness of the now, the sharp savour of living wholly in the present moment: no past, no worries. The chop of the ice axe, the crunch of the crampons, the hiss of breath – this is the very essence of life. Eventually I saw a couple of figures just above me, a couple of steps … and I was there.

I can’t remember much. Now it all seems a sort of vivid dream: bright sunlight, a tearing wind, a long flag of ice particles flying downwind of us. A vast drop of two miles into Tibet. We could see across a hundred miles of tightly packed peaks, and we could see the curvature of the earth. Contorted faces shouting soundlessly, lips blue with oxygen starvation. Doctors prove with blood samples that climbers are in the process of dying up there on the summit, but I would say that is where I started to live.

As I stumbled down the mountain one thought kept recurring to me. If I, a very average climber, could stand on this summit, how could the legendary George Mallory have failed to do so?

1

Start of an Obsession (#u06d386a6-a3b9-55cb-b70d-5a5c09aa74c9)

Mountaineering is in my blood. My father started taking me out into the hills of Arran when I was five, and I can still remember the moment when we scrambled to the top of the island’s highest mountain. I saw the sea laid out almost three thousand feet beneath us like a polished steel floor. Down there was Brodick Bay, with the ferry steaming in from the mainland like a toy boat.

Climbing was filled with sensation: the sheer agony of panting up steep slopes in the summer sun, the sharp smell of my father’s sweat as we lay resting in the heather, the hard coldness of a swim in the burn. Then the gritty feel of the granite under your fingers, and the blast of wind in your face as you breasted the summit.

It must have been a double-edged pleasure for my father, though. His brother, John Hoyland had been killed on Mont Blanc in 1934. Jack Longland, a famous climber of the day who was on the 1933 Everest expedition, described John as ‘potentially the best mountaineer of his generation … there was no young English climber since George Mallory of whom it seemed safe to expect so much’.1 (#u1985ee65-27cf-4aee-9e08-3b1ab548d30e)

John had hoped to go on the next expedition to Everest, but his death at the age of nineteen had put paid to those hopes. Even I could feel the loss at thirty years’ distance.

My father told me about another climbing hero in our family, a man who had been close to the summit of Mount Everest in 1924. He called him ‘Uncle Hunch’, and Dad said that one day I would meet him. He said he’d been a close friend of George Mallory, and again that name was mentioned. Mallory, the paragon of climbers. My young mind took it all in.

I lived and dreamed mountains on those summer holidays. To me Goat Fell, the highest of the Arran hills, looked uncannily like Mount Everest when viewed from the south; indeed it does to me even now. And it is almost exactly a tenth of Everest’s height. I remember cricking my neck back and back on the Strabane shore and trying to count out ten Goat Fells standing on top of each other. I couldn’t imagine anything so impossibly vast. How could anyone climb so high?

Eventually, when I was 13 and he was 81, I met Uncle Hunch.

We were at the memorial service of my great-aunt Dolly, who was one of the Quaker Cadburys. She was wealthy and lived in a large country mansion. I remember her house had a wide, open, red-carpeted spiral staircase for the family, inside of which was an enclosed stone staircase for the servants. I would race up the outer stairs past glass-cased model steam engines and then clatter down the inner, hidden stairs. We, the poor relations, used to receive a huge box of Cadbury’s chocolates every Christmas from Aunt Dolly, and I was particularly fond of her for her gentleness and the P. G. Wodehouse books she used to pass on to me.

Her death was a shame, I thought, a further distancing from a more romantic past. But oddly enough, I was about to be more firmly connected with that past.

I remember standing on the lawn outside Verlands and looking up at Uncle Hunch – the legendary Howard Somervell, who was actually a cousin, not an uncle.

He really was an extraordinarily gifted man: a double first at Cambridge, a talented artist (his pictures of Everest are still on the walls of the Alpine Club) and an accomplished musician (he transcribed the music he heard in Tibet into Western notation). He served as an army surgeon during the First World War and was one of the foremost alpinists of the day when he was invited to join the 1922 Mount Everest expedition. He took part in the first serious attempt to climb the mountain, and his oxygen-free height record stood for over 50 years. General C. G. Bruce, the expedition leader, described his strength on the mountain: ‘Stands by himself … an extraordinary capacity for going day after day.’2 (#u1985ee65-27cf-4aee-9e08-3b1ab548d30e)

Furthermore, the great explorer Sir Francis Younghusband said that of all the Everest men he met he liked Somervell the best.3

At that stage in my life I knew nothing about this, I was only interested in the incredible story he was telling me. He was a stout old man by then, with the slight stoop that gave him his family name, but his voice still contained the excitement of his twenties youth.

‘Norton and I had a last-ditch attempt to climb Mount Everest, and we got higher than any man had ever been before. I really couldn’t breathe properly and on the way down my throat blocked up completely. I sat down to die, but as one last try I pressed my chest hard’ – and here the old man pushed his chest to demonstrate to his fascinated audience – ‘and up came the blockage. We got down safely. We met Mallory at the North Col on his way up. He said to me that he had forgotten his camera, and I lent him mine. So, if my camera was ever found,’ said Uncle Hunch to me, ‘you could prove that Mallory got to the top.’ It was a throw-away comment that he probably had made a hundred times in the course of telling this story, but this time it found its mark.

Gripped by Uncle Hunch’s story, I discussed it endlessly with my father. The mystery seemed simple enough. Mallory and his young companion Sandy Irvine, on their desperate last attempt to climb Mount Everest in 1924, had just disappeared into the clouds. No one knew whether they had succeeded or not. When a British expedition finally got two men to the top in 1953 they looked for signs of the pair but found nothing. The only way of proving their success would be to find Somervell’s camera on a dead body, develop the film and discover a photograph of them on the summit. The story of Mallory and Irvine gripped my imagination. I read all the climbing books I could lay my hands on, and dreamed of being a mountaineer.

I had an idyllic boyhood in some ways. We were living in Rutland then, a rural part of England where rolling hills modulate into the flat lands of the Fens. This, the smallest of all the counties, is a secret Cotswolds of golden limestone villages, Collyweston stone slate roofs and fine churches. Our home was an archetypal English village, with a beautiful squire’s hall, a spired church and a huge vicarage dominating a cluster of alms cottages, pubs and farm houses. I went to a Victorian primary school that taught Victorian religion.

My brother Denys and I once scrambled on to the church roof in an attempt to climb the steeple with its conveniently placed stone croquets, intricately carved ornamental bosses about four feet apart. The reason for our climb was a village legend that a drinker in the Boot and Shoe public house had one evening wagered that he could shin up the slender steeple and bring down the weathercock from the very top. He had done so, and had then returned it to its place. The thought of climbing to that ultimate stone point, up there in the pale moonlight, filled me with excitement and dread. We had to try! After getting up a drainpipe in a corner we crossed the lead roof and started up the square tower on the east side. About ten feet up I grasped a stone corbel – and it came off in my hand. We hastily rammed it back into place. The climb was over.

Years later I found out that George Mallory had climbed the roof of his father’s parish church in Cheshire in a very similar way. Boys will be boys.

This idyll ended when I was sent to a local public school. The headmaster was an ex-Guards officer and, like Mallory, I was drafted into the Officer Training Corps as soon as I could polish a pair of boots. I got into trouble because my army boot toe-caps were scuffed by the Scottish heather.

Denys and my father had started taking me out climbing in the summer holidays on the Isle of Arran around the time we moved to Rutland. George Mallory went to Arran in August 1917 to climb with his friend David Pye and test a healing ankle. It was the first time he had walked in the Scottish hills and he enjoyed it:

The mountains themselves are so lovely, and when one gets high … the view of the islands and peninsulas in these parts is like being in some enchanting country – nothing I have seen beats it for colour.4

He stayed in Corrie, a small village on the east coast of the island, from which some of my ancestors came. My Scottish mother was brought up on Arran, and our family decamped to the island every summer holiday to stay with my grandmother. We didn’t live in the Front House, her solid sandstone terraced house in Brodick, but camped in the Back, a tiny, two-roomed cottage with wooden cabins behind it in another, recessive Back. Grandmother came with us, as well. From here, in an atmosphere of paraffin lamps and the smell of damp, come my oldest memories of the island.

The reason for my grandmother’s seasonal move was to make room for ‘the Folk’. Nearly everyone in Arran seemed to let their houses to holiday-makers from Glasgow. Lying in a dominant position in the Firth of Clyde made the island an attractive holiday destination from the late 19th century, but somehow its very popularity blinds people to the fact that it is one of the real gems of the British Isles.

The Scottish poet Robert Burns seemed indifferent to Arran, too. He must have seen its hills from the inland Ayrshire farms where he spent his youth, but he fails to mention the island in any of his writings. I became curious about this: could it be that a love of mountain beauty was just not fashionable in his time and place? Today Burns’s omission seems unaccountable; arriving at the dismal town of Ardrossan to catch the ferry it’s hard not to be impressed by the view across 14 miles of sea – if it is not raining. Then you might just see a dirty, grey smudge. But on a clear day, the island floats there in all her glory.

Arran is ancient. It was an island before the mainland of Britain parted company with Europe, and the mountains here were once as high as the Himalayas, which are youngsters by comparison at only 55 million years old. Now Goat Fell has worn down to just under 3,000ft, and so it is not even big enough to qualify as a Munro, a Scottish mountain over that height. This serves to point out the absurdity of a system based on size.

2

Getting the Measure of the Mountain (#u06d386a6-a3b9-55cb-b70d-5a5c09aa74c9)

As a schoolboy I had become curious about how the height of Mount Everest was calculated. You could hardly bore a hole in the summit and drop a tape measure from the top until you hit the bottom. So how was it done? I found the answer in Aunt Dolly’s 1920s Encyclopaedia Britannica, and I found it even more amazing than the story of the attempts to climb the mountain.

The British in the 19th century were fascinated by exploring their world, measuring its features and naming them. They were making an inventory of their empire, but perhaps they were also trying to make sense of a planet of rock and sea whirling through the universe. They were particularly captivated by India. My missionary grandfather and his medical cousin Somervell – and I in turn – all fell in love with the sub-continent, and my father was born in Nagpur. India is a great, exotic, bohemian mother of our imagination, and the England of my childhood seems a pale reflection of her culture and peoples.

The Great Trigonometrical Survey was commissioned by the East India Company to survey all their lands in the sub-continent. The survey started in 1802, and it was initially estimated it would take just five years to complete the work. In the end, it took more than sixty years, and cost the Company a fortune.

Imaginary triangles were to be drawn all over India, starting at the southern end and eventually reaching the Himalayas over 1,500 miles away. A great arc of 20° would be drawn along the earth’s surface. This would also establish how much the earth flattened towards the poles. The measurements had to be extremely accurate otherwise errors would build up by the time they reached the Himalayas.

The precision the surveyors attained was remarkable. A baseline between two points visible to each other about seven miles apart would be carefully measured with 100ft chains. Later, special metal bars that compensated for the expansion due to temperature were used. If there was a village in the way it would be moved, and 50ft masonry towers were built at the end of the baseline if there wasn’t a convenient hill available. Then a huge brass theodolite would be hoisted to the top of the tower, and the exact angle between the baseline and the sightline to a third point would be measured. Sightings were made using mirrors to flash sunshine at far-distant colleagues, and blue lights were used at night if the heat of the day caused refraction.

A triangle was thus formed and, as every schoolchild knows, if the length of the baseline and the two angles are known, the length of the other two sides can be worked out. This meant that surveyors didn’t have to measure them on the ground.

The height of a mountain was calculated by measuring its angle of elevation from several different places, drawing vertical imaginary triangles this time. This was important, as it meant that the surveyors could now work out the height of distant unclimbed mountains in an inaccessible country.

A typical expedition employed four elephants for the surveyors and 30 horses for the military officers – both groups wishing to avoid encounters with tigers – and more than 40 camels for the equipment. The 700 accompanying labourers travelled on foot and clearly had to take their chance with the tigers.

The survey was begun in the southernmost point of the sub-continent, at Cape Cormorin, very close to where Somervell’s hospital at Neyyoor would later be built.

Begun by Major William Lambton, the survey was supervised for most of its extent by Colonel George Everest, a man noted for his exacting accuracy. When he took over the job the survey equipment used by Lambton was worn out. There was the great brass 36-inch theodolite made in London by Cary, weighing 1,000lb (which had been accidentally dropped a couple of times), a Ramsden 100ft chain that hadn’t been calibrated in 25 years, a zenith sector also by Jesse Ramsden, now with a worn micrometer screw, and a chronometer. These were all repaired by an instrument maker brought in from London, and Everest pressed on with his life’s work.

Ill-health, the bane of many a Briton in India, eventually caught up with Everest, and so Andrew Waugh had to finish off the job. Interestingly, he re-measured the Bidar baseline with the special Colby compensating bars. The error after 425 miles and 85 triangles was only 4 inches in a line length of 41,578ft.

What is not generally acknowledged is that the surveyors often became rich. Knowledge of the terrain was clearly useful. The Chamrette dynasty of surveyors – grandfather, father and son – owned over 1,800 acres, and George Everest bought 600 acres of land near Dehra Dun. The British Empire became wealthy, too, with the possession of this fabulous land. If I were an Indian citizen reading this now I would be feeling fairly angry. The only (poor) defence is that other nations were also playing the Great Game in the region, and partly what drove the British Empire to survey its borders was fear of invasion from the Russian Empire.

Eventually this great endeavour reached the border with Nepal, a land that was forbidden to the British. The surveyors focused their instruments on the far Himalayas, drew their triangles and measured 79 of the highest mountains, including K2 and Kangchenjunga. Eventually they computed in 1854 that the most lofty was a mountain on the remote border between Nepal and Tibet. They had to allow for the gravitational pull of the Himalayan range (which will even distort the surface of a puddle), the refraction of the atmosphere and a number of other variables, and it is a wonder to me that they got the height so close: 29,002ft. It took over 150 years to pin down a more accurate result, although still no one agrees on exactly how high the mountain is. All measurements are now made in metric units, and China insists that the measurement should be made up to the topmost rock, at 8,844m (29,015ft), whereas Nepal measures to the top of the overlying snow-cap, at 8,848m (29,028ft). The US National Geographic Society measurement using satellites came to 8,850m (29,035ft) – a difference of 33ft from the original Great Trigonometrical Survey result, or around 0.1 per cent error. Not bad, considering the pioneers were using telescopes and brass theodolites, aimed from across the border.

The first scrawl on the map announcing Mount Everest styled it as ‘Peak B’, then ‘Peak XV’, somewhat in the manner of K2 in the Karakorum, which after a brief existence as Mount Godwin-Austen reverted to its surveyor’s notation. There has been much debate about the name of Mount Everest. Traditionally, British surveyors always tried to use the local name for geographical features. This was an honourable intention, as otherwise the world’s maps would be plastered with the names of British dignitaries. In Mount Everest’s case, however, they found that there were several possible local names. The Swedish explorer Sven Hedin claimed that it was called Tchoumou Lancma, and said that the name had been recorded by French Jesuit priests who had been in China in the 18th century. When spelled as Chomolungma, the name has been fancifully translated by imaginative writers as ‘Goddess Mother of the World’, but this has little connection with the truth. Charles Bell, who knew a thing or two about Tibetan culture, insisted that the local name was Chamalung. David Macdonald, the trade agent who dealt with the early Everest expeditions, claimed the mountain was called Miti Guti Chapu Longnga, which translates rather more convincingly as ‘the mountain whose summit no one can see from close-up [true only from the south], but can be seen from the far distance, and which is so high that birds go blind when they fly over the summit’. I rather like this name, except that my companion on the summit in 1993 saw an alpine chough fly right over us. It didn’t appear to go blind. This name would also make all the innumerable books about the mountain even longer. In the end, though, the British chose the name of the former Surveyor-General Sir George Everest.

It is unlikely that Everest himself ever laid his eyes on the mountain that bears his name, but Andrew Waugh, Everest’s successor as Surveyor-General in India, wrote: ‘… here is a mountain most probably the highest in the world without any local name that I can discover …’, so he proposed ‘to perpetuate the memory of that illustrious master of geographical research … Everest’.

This went completely against contemporary cartological practice, and it was the start of the long story of the mountain being hijacked for ulterior motives. Everest himself said his name could not be written in either Hindi or Persian, and nor could the local people pronounce it. Nor can we. He pronounced his name Eeev-rest, as in Adam and Eve, while the rest of us happily mispronounce it as Ever-rest, as in double-glazing.

At the beginning of the 19th century the British wanted to know how the Russian Empire might plan to invade India, and they were not going to be deterred by forbidden frontiers. Geographical knowledge was power. Heights of mountains were important, and even more important was the accessibility of the passes between them. In 1800 the Surveyor-General of Bengal permitted British officers to enter and survey any country they chose. Unfortunately, some were caught in Afghanistan and murdered, but not before some spectacular heights were reported among the Himalayan giants. It was clearly unwise to send blue-eyed, fair-haired young men into these parts, and Captain Montgomerie of the Survey (who surveyed and named K2) soon realised it would be better to employ local men from the Indian Border States as surveyors. They were given two years of training in the use of the instruments and were then sent over the border disguised as holy men or traders. They were known as pandits, Hindi for ‘learned man’. We derive our word ‘pundit’ from these remarkable men.

Perhaps the most remarkable was Pandit 001, Nain Singh, a Bhotian school teacher. He left Dehra Dun in 1865 and entered Nepal, travelling through the country into Tibet, where he reached Lhasa and met the Panchen Lama. Using a sextant (I wondered where he hid it) and a boiling-point thermometer he calculated the location and the altitude of the forbidden city.

I used the boiling-point technique to determine altitude at Base Camp on Mount Everest in 2007 while filming a science programme for the BBC. The first thing we did was to get a big pan of water to a good rolling boil, as Mrs Beeton would call it (she was writing her cookbook just as the pundits were setting off in the 1860s). I then stuck the big glass thermometer into the water and got a reading of only 85°C. Water boils at 100°C at sea level. This meant the altitude was around 4,600m (15,000ft). The reason that water boils at a lower temperature at higher altitude is that water is trying to turn into a gas (steam) when it boils, and it is easier for the steam to push against the air molecules when there are fewer of them (lower pressure). Bubbles – or boiling – are the result. When I got frostbitten fingers on the summit in 1993 I was able to dangle them in a pan of boiling water at Camp II. It only felt hot, rather than painfully hot.

If someone were to boil up a kettle for tea on the summit of Mount Everest – and I’m sure they will sooner or later – it would start boiling at only 68°C. And it wouldn’t make very good tea. Incidentally, it was hard to keep the long glass thermometer unbroken on our journey into Base Camp in 2007. Pundit Nain Singh concealed his in a walking-staff, but how he didn’t break it is beyond me.

The map-makers of British India now had a mystery on their hands. As well as locating the city of Lhasa, Nain Singh had also mapped a large section of a huge river in Tibet, the Tsangpo, which plunged into a gorge and disappeared. Hundreds of miles away the sacred river Brahmaputra issued from the Himalayas, but there were thousands of feet of height between them. Were they the same river? Nain Singh thought they were. So was there an undiscovered giant waterfall, many times higher than the Victoria Falls? That was the riddle of the Tsangpo.

It was partly solved by another pundit, Kinthup, in a truly amazing journey. In 1880 he was sent into Tibet in the company of a Chinese lama, to whom he would act a servant. They were to throw marked logs into the Tsangpo and surveyors on the Brahmaputra would wait to see if any logs came through. Unfortunately, the lama was a less than ideal master. He womanised and drank, then sold Kinthup into slavery. The pundit eventually escaped, but was captured and resold to another lama.

It took Kinthup four years to get to the point on the Tsangpo from which he had to send his timber signal. He prepared five hundred logs and threw fifty into the river per day. Eventually he got back to India, where he asked if anyone had seen the logs. But all of those who had sent him on his mission had either left India or died. ‘Which logs?’ the men of the Survey said, and poor, disillusioned Kinthup left to become a tailor. One can only imagine his chagrin after so many years of work, and what a modern employment tribunal might make of it all. In the end the surveyors Morshead and Bailey explored the river from the south, and at last, in 1913, Kinthup’s reports were believed. The Tsangpo and the Brahmaputra were accepted as the same river, and this great explorer was at last recognised with a pension, grants of land and a medal.

I have a personal theory about the pundits: I think they were partly the inspiration for James Bond, Agent 007. Consider this: they were numbered 001, 002, 003, etc., and were spies in enemy territory. They carried maps hidden in prayer wheels, and counted their carefully practised 2,000 paces a mile on special Buddhist rosaries on which every tenth bead was slightly larger …

At about the time Mount Everest was being measured, thousands of miles away in Europe the leisure sport of alpinism was being invented by the sons of English gentlemen who had been enriched by the Industrial Revolution. Before then, most sensible mountain-travellers regarded the high peaks as dangerous wastelands inhabited by demons. All this started to change in the early 19th century, when Samuel Taylor Coleridge, the Romantic poet, wrote about his climb on Broad Stand, in England’s Lake District.

In June 2010 three friends and I retraced Coleridge’s route to try to experience exactly what he felt. He was on the summit of Scafell, England’s second highest mountain (Scafell Pike is the highest), having scrambled up a safe route. He then decided to experiment with the then fashionable sublime feelings of terror by picking a descent route that looked possible – but only just – down through a series of tumbling rock terraces. Later, boasting to his girlfriend (as we all do), he wrote:

I began to suspect that I ought not to go on, but then unfortunately tho’ I could with ease drop down a smooth Rock 7 feet high, I could not climb it, so go on I must and on I went. The next 3 drops were not half a Foot, at least not a foot more than my own height, but every Drop increased the Palsy of my Limbs – I shook all over, Heaven knows without the least influence of Fear, and now I had only two more to drop down, to return was impossible – but of these two the first was tremendous, it was twice my own height, and the Ledge at the bottom was so exceedingly narrow, that if I dropt down upon it I must of necessity have fallen backwards and of course killed myself.

I was impressed by Coleridge’s boldness. The route descends over downward-sloping ledges that are separated by higher and higher rock walls, with a deadly drop-off onto the jagged scree below. It all feels rather intimidating. Halfway down an irreversible descent he got himself completely stuck above a big drop, unable to return upwards or progress downwards. This same predicament has since led to the deaths of climbers. He then experienced those feelings of terror that are only too familiar to us:

My Limbs were all in a tremble – I lay upon my Back to rest myself, and was beginning according to my Custom to laugh at myself for a Madman, when the sight of the Crags above me on each side, and the impetuous Clouds just over them, posting so luridly and so rapidly northward, overawed me. I lay in a state of almost prophetic Trance and Delight – and blessed God aloud, for the powers of Reason and the Will, which remaining no Danger can overpower us!1 (#ubc25fa01-b82c-4570-b23d-a2d4c9763196)

I lay in exactly the same spot and thought about Coleridge’s power of Reason. He was clearly not just an excitable Romantic. He had calmed himself down and thought about how to get out of his predicament. Just below and to the left of this final ledge there is a narrow chimney that is not immediately obvious. In the event he was able to explore sideways and slither down this chimney, which is now known as Fat Man’s Peril. If there had been no exit we may have lost one of our most interesting literary figures. This just goes to show the importance of careful reading. If only British climbers had stuck to Coleridge’s idea of rock-climbing downwards, modern mountaineering would be very different.

His wasn’t the first rock climb in Britain, though. There are modern routes that were first climbed long before the sport evolved, some by shepherds rescuing crag-fast sheep, some by birds-nesters, and some just by young dare-devils. In 1695 men were described using ropes for rock climbing on traditional fowling expeditions in the St Kilda archipelago. Slowly, rock climbing evolved into an activity in its own right, and as with many cultural movements it is hard to pin down a moment when rock climbing as a sport began. It started in at least three areas: the sandstone crags of the Elbsandsteingebirge, near Dresden; the Dolomites in Italy; and the Lake District in England, where a small group of climbers started rock climbing above the valley of Wasdale, beneath Scafell Pike.

Many were serious-minded, middle-class Victorian gentlemen who sought an escape from the industrial northern towns of Liverpool and Manchester. The father of English rock climbing was Walter Parry Haskett Smith, who, 84 years after Coleridge’s climb, made a solo first ascent (upwards instead of downwards) of Napes Needle, an obelisk-like pillar just across the Wasdale valley from Broad Stand. An early climb that is in touch with modern standards was O. G. Jones’s 1897 climb of Kern Knotts Crack, graded Very Severe, and significantly Jones was attracted by a photograph of Napes Needle that he saw in a shop on the Strand in London. Similarly, the television films that we make on Mount Everest draw new recruits to mountaineering. And if they learn about the fun of climbing, then why not?

The British are usually credited with inventing the sport of alpinism, and it was largely because of leisure. Britain was ‘an island of coal surrounded by a sea of fish’, and happened for many reasons to be the first nation to industrialise (it could so easily have been the Romans, who were close to steam power, or the Indians, who had even more resources). The Industrial Revolution provided many a wealthy man’s son with ample time and money while the average Swiss peasant was far too busy scraping a living off the mountainsides to waste time raising his eyes to the summits.

Sir Alfred Wills, who was Edward Norton’s grandfather, kicked off the Golden Age of Alpinism with his 1854 ascent of the Wetterhorn (although it wasn’t actually the first ascent, which had been made ten years earlier by Stanhope T. Speer with his Swiss guides). There then followed an explosion of climbing, with most of the major peaks being bagged within ten years. There was a similar period in the Himalayas a century later, when all the 14 peaks over 8,000m (26,247ft) were climbed within 11 years of each other.

The Alpine Club was founded in London in 1857. Simon Schama in his Landscape and Memory notes that the members of the Club were predominantly upper-middle-class rather than aristocratic, and that they thought of themselves as a caste apart, a Spartan phalanx, tough with muscular virtue, spare with speech, seeking the chill clarity of the mountains just because, as Leslie Stephen, who became the club’s president in 1865, put it, ‘There we can breathe air that has not passed through a million pairs of lungs.’2

It is curious that so many writers had brothers who became Himalayan climbers: Greene, Spender, Auden. It is interesting, too, that it seemed to be the left-wing intellectuals who wanted to place themselves above the masses. John Carey writes:

The cult of mountaineering and alpine holidays among English intellectuals … seems to have been encouraged by Nietzschean images of supremacy. Climbing a mountain gave, as it were, objective expression to the intellectual’s sense of superiority and high endeavour, which otherwise remained rather notional.3

There is a danger in this search for purity that surfaced later in the Nazi fascination with mountain climbing.

The pace of Alpine climbing accelerated, with Edward Whymper knocking off the Col de Triolet, the Aiguille de Tré-la-Tête and the Aiguille d’Argentière in one week in 1864 with guide Michel Croz. His 1865 book Scrambles in the Alps was a sensation, describing the first ascent of the Matterhorn and the ensuing accident that killed four of his companions. Suddenly, the new sport assumed a dangerous new edge in the public mind, and the short but golden age of Alpine climbing was over.

Back in England there was a disaster high on Scafell Pinnacle in 1903 that Somervell and Mallory would have been very well aware of, as it was much discussed at the time. The tradition then was that ‘the leader must not fall’, because the hemp ropes climbers used were not strong enough to take much of a shock, and modern protection devices such as Friends – camming devices that expand into cracks in the rock and to which a climbing rope can be attached – were as yet undreamt of. All that the climbers could do was to loop the rope over a spike of rock, if available, or jam a rock into a crack and pass the rope behind it. In the 1903 accident, there was no belay point available, and four men fell 200ft to their deaths.

As we shall see, George Mallory would have had the need for a belay very much in mind on 8 June 1924 as he scanned the cliffs above him for a route to the top of Mount Everest.

3

Renaissance Men (#u06d386a6-a3b9-55cb-b70d-5a5c09aa74c9)

I was a bookish child, and rather shy. I didn’t quiz Uncle Hunch about his story, but when we got home from Aunt Dolly’s memorial service I found out more about him, Mount Everest and his friend Mallory in the memoir that he wrote titled After Everest. I have the book next to me, still wrapped in my grandmother’s sewn cover. His climbing life, including Mount Everest, takes up less than a third of the pages, and he makes it clear that his medical missionary work was far more important to him. So many Everesters keep going back and back to the mountain of their obsession, and it is entirely typical of him that he was able to develop himself away from it.

One of the problems of assessing multi-talented individuals is that most of us can only appreciate one aspect of them at a time. If anyone has heard of T. H. Somervell nowadays they might think of him as one of Mallory’s fellow-climbers on Everest, or maybe as a painter of mountain landscapes. Some readers in India might still remember his medical work in their country, but he excelled in several fields and was one of the most interesting characters on those early Everest expeditions.

He was born in 1890 to a well-to-do evangelical family in Kendal who owned K Shoes, a prosperous boot-making company. At Cambridge he at first derided modern art, then adopted it. Similarly, he toyed with atheism, joining a society named the Heretics, and ‘for two years I strenuously refused to believe in God, especially in a revealed God’.1 (#ue21d0783-4941-44eb-a743-f1c43792d677) Afterwards he felt there was something missing from his life, and felt that his atheist fellow students were ‘wallowing in an intellectual nowhere’. After a chance prayer-meeting he rediscovered his faith and became for a while a passionate evangelical. This mellowed into a steady religious faith that remained with him and informed all the major decisions of his life. It is almost as if the young Somervell had to experiment with opposites, push hard in contrary directions, before he could find his place in both art and religion. Perhaps the extreme horror of his war-time experiences swung him towards extreme faith.

I wanted to know how he began climbing. The 18-year-old Somervell had taken to solitary walking in his native Lake District, and one day saw a party of rock climbers. He followed them up their route on his own, and when he reached the top he was ticked off for climbing without either a companion or a rope. On buying one of the Abraham brothers’ guidebooks he was delighted to realise he’d done a climb described as ‘Difficult’. He continued going rock climbing, and this eventually led to the Alps, where one of his early climbs had an ecclesiastical flavour: he teamed up with a parson and the Bishop of Sierra Leone. Unfortunately, the bishop slipped off an overhang and dangled in mid-air, swinging like a pendulum. Somervell started to lower him but the noose around his waist was loose, the unfortunate cleric raised his arms and the rope slid off. He hung by his hands alone, and ‘certain death was beneath him if he could not hold on.’2 (#ue21d0783-4941-44eb-a743-f1c43792d677) Somervell redoubled his lowering, and got the bishop to the safety of a snow-slope before his strength gave out. This calm rescue of another climber foreshadowed his rescue of porters on Everest in 1924.

Next came his experience of the army. After Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge, and qualification as a surgeon at University College Hospital, London, he joined up in early 1915 and went to the Front. This experience had a profound effect on him, as it did on other members of the Everest expeditions. His casualty-clearing station, the 34th, was on the Somme Front, at Vecquemont, between Amiens and Albert. Another Cambridge man, Second Lieutenant George Mallory of the 40th Siege Battery, was not far away at Pioneer Road, Albert. Mallory’s job as an artillery officer was to pound the enemy lines with high-explosive shells in preparation for the greatest British offensive of the war, when 300,000 men attacked the Germans on 1 July 1916.

It was a disaster. Somervell’s clearing station, with its two surgeons per six-hour shift, was expected to deal with a thousand casualties; instead, streams of motor-ambulances a mile long brought nearly 10,000 terribly wounded young men after the attack. The camp, in a field of five or six acres, was completely covered with stretchers. The surgery was a hut with only four tables, and Somervell had to walk among the victims and choose which they could try to save.

Occasionally, we made a brief look around to select from the thousands of patients those few fortunate ones whose life or limbs we had time to save. It was a terrible business. Even now I am haunted by the touching look of the young, bright, anxious eyes, as we passed along the rows of sufferers.

Hardly ever did any of them say a word, except to ask for water or relief from pain. I don’t remember any single man in all those thousands who even suggested that we should save him and not the fellow next to him … There, all around us, lying maimed and battered and dying, was the flower of Britain’s youth – a terrible sight if ever there was one, yet full of courage and unselfishness and beauty.3 (#ue21d0783-4941-44eb-a743-f1c43792d677)

Beauty seems an odd word to use about this most grotesque of wars, and it is worth being alert to it, as it is relevant to our subject. Somervell goes on to explain:

I know that, again and again, when, sick of casualties and the wilfulness of man that maims these poor bodies, I did see an unselfishness, a fine spirit, and a comradeship, that I have never seen in peace-time. But in spite of all that, the very gloriousness of the spirit of man is a call to the nations to renounce war and give love a chance to bring forth the best that is in mankind.4 (#ue21d0783-4941-44eb-a743-f1c43792d677)

Note the reference to the spirit of man. The Poet Laureate Robert Bridges chose The Spirit of Man as the title for an anthology of prose and poetry, published in 1915. It is a curious book, written during the war under the auspices of the War Propaganda Bureau, and full of exhortations to self-sacrifice. ‘We can therefore be happy in our sorrows,’ writes Bridges, ‘happy even in the death of our beloved who fall in the fight; for they die nobly, as heroes and saints die; with heart and hands unstained by hatred or wrong.’5 (#ue21d0783-4941-44eb-a743-f1c43792d677) Mallory and Somervell were to read selections from the book as they lay in their shared tent on Everest in 1922.

It was not noble to die chopped up by a machine-gun or gassed. The Spirit of Man was an encouragement towards self-sacrifice. Like the older members of my family, these men had a culture of public-spiritedness and Christian unselfishness that would be inconceivable to most of today’s Everest climbers. I think it might have influenced the climbing choices that Mallory and Somervell made, and partly explains the extreme guilt they felt when seven Sherpas died in the accident that ended that expedition of 1922, a guilt I have rarely seen in the carnage of a modern Everest season.

The casualty work was exhausting, and on one occasion Somervell had to operate for two and a half days on end, without sleep. One day during the Somme campaign he went for a short walk on the battlefield and sat down on a sandbag. He saw a young lad asleep in front of him, looking very ill. After a while, with horror, he realised what he was looking at:

My God, he’s not breathing! He’s dead! I got a real shock. I sat there for half an hour gazing at that dead boy. About eighteen … For a moment he personified this madness called War … Who killed him? The politicians, the High Command, the merchants and financiers, or who? Christian nations had killed him by being un-Christian. That seemed to be the answer.

Somervell’s view was that the two world wars were simply one prolonged war, with the failure of the Versailles Treaty to curtail German aggression meaning that it reasserted itself during the 1930s. Somervell felt that if Germany had been occupied and stabilised, the horror and madness of the Third Reich could have been contained.

A few miles away, Mallory’s experience as an artillery officer was somewhat different, as he would not have seen as much of the bloody consequence of shelling as would a surgeon. Although the two men’s roles were different, the common experience of the Great War formed a similar outlook and cemented their later friendship.

It is difficult to exaggerate the effect the conflict would have had on those survivors of the Great War. Gas was used on the Somme on 18 July:

Gas! Gas! Quick, boys! – An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling,

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime …

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie; Dulce et Decorum est

Pro patria mori.6

Wilfred Owen, the author of this poem, was losing his Christian faith by the time he was killed, just a week before the end of the war. Arthur Wakefield, another Lake District surgeon at the Somme who experienced the same horrors as Somervell, and who also went to Everest, completely lost his faith. So did another Everester, Odell, who was also at the Somme. Many others lost their confidence in the solidity of things, and perhaps those first attempts to climb Mount Everest tried to put things right for an empire that had taken such a grievous battering.

For Howard Somervell, however, the horrific work somehow made his faith stronger, not weaker. His sons both said to me that it was the most important thing about him; it was the key to his character.

After the war Somervell resumed climbing. He went to Skye in June 1920 and made the first solo traverse of the Cuillin Ridge, from Sligachan to Gars Bheinn at the south end. I have done this route – but not all in one day – and it is a tough proposition. Like others of Somervell (and Mallory’s) climbs that I have repeated, it is surprisingly extended and sometimes poorly protected – that is to say, the rope running out behind the leader goes a long way back to an attachment to the rock, and those attachments are not very secure.

We modern climbers like to think we are better than our predecessors because we do harder climbs, but when we strip out the technology we realise they were probably tougher and braver. They lived harder lives in unheated houses, and maybe just walked more than we do.

After Skye, Somervell returned to the Alps in 1921, where he climbed nearly 30 Alpine peaks in one holiday. Here he was accompanied by Bentley Beetham, who went to Everest in 1924. He climbed in the Alps with Noel Odell and Frank Smythe a couple of years later, and these trips were a way of testing climbers for an Everest expedition. Some modern pundits tell us that these men formed an exclusive upper-class clique devoted to keeping colonials and the lower classes out of their club, but I think they just chose to climb with congenial people they knew, just as the rest of us do. Later on, Irvine was selected, because he also knew Odell. Then Somervell thought his big chance had come:

Everyone who is keen on mountains … must have been thrilled at the thought – which only materialised late in 1920 – that at last the world’s highest summit was going to be attempted. And by no means the least thrilled was myself … I had at least a chance of being selected to go on an expedition which was then being planned for 1921.7

Somervell applied to join the 1921 reconnaissance expedition to Mount Everest, but was not chosen. However George Mallory was taken, as he was considered the foremost alpinist of the day. They did not know each other well at that stage since Somervell had gone up to Cambridge after the older man. So, for the moment Howard Somervell had to stand on the sidelines and watch.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/graham-hoyland/last-hours-on-everest-the-gripping-story-of-mallory-and-irv/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Graham Hoyland

An expert mountaineer cracks Everest’s most intriguing mystery - did Mallory and Irvine reach the summit before they perished on its slopes?

On the 6th June 1924, mountaineers George Mallory and Sandy Irvine perished in their attempt to reach the summit of Everest.

Obsessed by uncovering what happened, in 1993 Graham Hoyland became the 15th Englishman to climb Everest. His investigations led to the finding of Mallory’s body; it will be his evidence that will recover Irvine’s.

‘Last Hours on Everest’ meticulously reconstructs that fateful day. Combining his own expert insight with the clues they left behind, Graham Hoyland at last answers the most intriguing of questions – did the two men actually reach the top of Everest?

Contents

Cover (#u0553975d-9c19-5588-92d8-d3851714f638)

Title Page

Preface (#ulink_b09e8d1b-d7ec-5054-b7b9-5413c7216f8b)

Prologue (#ulink_18fdf758-a490-5dbb-9d00-161b16e76090)

1 Start of an Obsession (#ulink_ef7defd3-41b2-5a7c-87f6-635b7050e480)

2 Getting the Measure of the Mountain (#ulink_01e4e77b-8a5d-5d08-b71d-b9eed1aa6e98)

3 Renaissance Men (#ulink_86bd9722-ac74-57b8-81cf-4b23da4d1844)

4 Galahad of Everest (#ulink_bb67df26-5dff-5a87-8756-df383e9df79f)

5 The Reconnaissance of 1921 (#ulink_af799936-8373-5da5-862a-9226b3ec0687)

6 The Expedition of 1922 (#ulink_c45c8bfa-fbb7-5793-b187-3627c3f71769)

7 1922, and the First Attempt to Climb Mount Everest (#ulink_3a3b698c-0aa1-55ea-af7b-6e208c535e2b)

8 ‘No trace can be found, given up hope …’ (#ulink_7c523057-f810-574c-99d9-03ad032ade04)

9 A Pilgrim’s Progress (#ulink_8338429b-aae8-57f7-8d5c-9be93407e1e9)

10 John Hoyland and a New Clue (#ulink_36ee1d9d-1d6f-573a-946d-1007de9044fd)

11 I First Set Eyes on Mount Everest (#ulink_e774a979-b37e-5dfb-9c8b-17d6076564b0)

12 High Mountains, Cold Seas (#ulink_f2ce5fb0-3ad3-52ae-9b86-c07ddc400071)

13 The Finding of Mallory’s Body (#ulink_8511c635-9e20-55d5-aa3d-603e7328578d)

14 When Did Everest Get So Easy? (#ulink_9e112482-5235-5a17-a614-b6242746290d)

15 Why Do You Climb? (#ulink_78364cca-7de1-582b-9a50-5fa06c4b5119)

16 What Does Mount Everest Mean? (#ulink_e76a37ab-0f57-519b-b61c-600569a73962)

17 The Theorists and Their Theories (#ulink_40663a6e-4eca-534f-a85b-76c3578aa9f8)

18 Wearing Some Old Clothes (#ulink_fa06a0fd-17f2-5211-9f8c-833cf689cece)

19 Perfect Weather for the Job (#ulink_2c0874a4-feb5-5bf1-8171-03b226312dcd)

20 Utterly Impregnable (#ulink_58053ced-6940-53f0-906d-dfae1113e58e)

21 What Was in His Mind? (#ulink_205a46d8-14a9-50e1-a4e3-34a8ef432bcd)

22 Weighing the Evidence (#ulink_ee61653d-b146-5764-880d-b56bc6faac69)

23 The Last Hours (#ulink_89ac89b4-4d3f-540a-b440-4d68c1c88a4c)

Postscript: Goodbye to Everest (#ulink_15e4ebd8-9d1d-5130-a94b-e45190149e0b)

Chronology (#ulink_5152f115-a5a9-590c-9273-dd4d9120fb96)

Notes (#ulink_7d027db8-c7e8-5c0b-9135-eb24eace2eea)

Credits (#ulink_a28dd1d4-9aa8-52d0-ba84-80ea071d343a)

Acknowledgements (#ulink_c0a43ac7-fb35-5e2f-8d2d-d38c01c81754)

Picture Section (#ulink_e838afd7-c9b1-5e2f-8242-a5428ddd720b)

About the Author (#uac5cb4bc-ba80-5f6e-ac40-eb6c44e26e7c)

Copyright (#ulink_d7506bf8-c901-5ac2-b917-304819a0398e)

About the Publisher (#u20b49074-bef2-5981-a595-21ac95413c74)

Preface (#u06d386a6-a3b9-55cb-b70d-5a5c09aa74c9)

Mount Everest has been my arena. I have spent over two years of my life on the mountain, returning there again and again. I am drawn back because I see there the extremes of human experience played out in the most dramatic surroundings: greed and betrayal, loyalty and courage, endurance and defeat. It is a moral crucible in which we are tested, and usually found wanting. It has cost me my marriage, my home and half my possessions. Twice Everest has nearly killed me. But I find it utterly addictive. And so did George Mallory.

This volume is going to add to the vast pile of books about Mount Everest, a pile that must now must be higher than the mountain. I make no apology for this, for I think I have finally solved the mystery of what happened there on 8 June 1924, when Mallory and his young companion Sandy Irvine disappeared into clouds, climbing strongly towards the top.

My family had a unique relationship with Everest, and this helped me to climb the mountain and to find clues to what happened to Mallory, its most famous opponent. I spent a long time looking for his body, and then I spent a long time trying to prove that he climbed his nemesis before it killed him.

This is going to be a personal story, a detective thriller, a biography and a history book.

I hope it will set the record straight about how Mallory was found. It is about other things, too, such as why we believe in gods and mountains.

Most of all, though, it is about my life-long hunt for an answer to the greatest mystery in mountaineering: who first climbed Mount Everest?

Prologue (#u06d386a6-a3b9-55cb-b70d-5a5c09aa74c9)

Dawn broke fine on that fatal day. A couple of thousand feet above the tiny canvas tent the summit of the world’s highest mountain stood impassively, waiting for someone to have the courage to approach.

Inside the ice-crusted shelter, two forms lay as still as death. Then there was a groan, a stirring, and eventually the slow scratch of match against sandpaper. Low voices shared the high-altitude agonies of waking, the heating of water and the struggle with frozen boots.

As the sun rose through wisps of cloud beyond the Tibetan hills to the east, one of the men emerged through the tent flaps. It was a fine morning for the attempt, with only a few clouds in the sky. The two of them stood for a while, shuffling their feet and blowing into their hands. Inside the tent lay a mess of sleeping bags and food. The men lifted oxygen sets onto their backs, then turned towards the mountain and stamped off into history.

Seventy years later, above the Hillary Step on the other side of the mountain, I was teetering along the narrow icy summit ridge between Nepal and Tibet, between life and death. The sun was intensely bright and the sky was that deep blue-black of very high altitudes. All around were the icy fins of the world’s highest mountains. And somewhere along that ridge I experienced one of those existential moments that gives you the reason for gambling with your life. The intenseness of the now, the sharp savour of living wholly in the present moment: no past, no worries. The chop of the ice axe, the crunch of the crampons, the hiss of breath – this is the very essence of life. Eventually I saw a couple of figures just above me, a couple of steps … and I was there.

I can’t remember much. Now it all seems a sort of vivid dream: bright sunlight, a tearing wind, a long flag of ice particles flying downwind of us. A vast drop of two miles into Tibet. We could see across a hundred miles of tightly packed peaks, and we could see the curvature of the earth. Contorted faces shouting soundlessly, lips blue with oxygen starvation. Doctors prove with blood samples that climbers are in the process of dying up there on the summit, but I would say that is where I started to live.

As I stumbled down the mountain one thought kept recurring to me. If I, a very average climber, could stand on this summit, how could the legendary George Mallory have failed to do so?

1

Start of an Obsession (#u06d386a6-a3b9-55cb-b70d-5a5c09aa74c9)

Mountaineering is in my blood. My father started taking me out into the hills of Arran when I was five, and I can still remember the moment when we scrambled to the top of the island’s highest mountain. I saw the sea laid out almost three thousand feet beneath us like a polished steel floor. Down there was Brodick Bay, with the ferry steaming in from the mainland like a toy boat.

Climbing was filled with sensation: the sheer agony of panting up steep slopes in the summer sun, the sharp smell of my father’s sweat as we lay resting in the heather, the hard coldness of a swim in the burn. Then the gritty feel of the granite under your fingers, and the blast of wind in your face as you breasted the summit.

It must have been a double-edged pleasure for my father, though. His brother, John Hoyland had been killed on Mont Blanc in 1934. Jack Longland, a famous climber of the day who was on the 1933 Everest expedition, described John as ‘potentially the best mountaineer of his generation … there was no young English climber since George Mallory of whom it seemed safe to expect so much’.1 (#u1985ee65-27cf-4aee-9e08-3b1ab548d30e)

John had hoped to go on the next expedition to Everest, but his death at the age of nineteen had put paid to those hopes. Even I could feel the loss at thirty years’ distance.

My father told me about another climbing hero in our family, a man who had been close to the summit of Mount Everest in 1924. He called him ‘Uncle Hunch’, and Dad said that one day I would meet him. He said he’d been a close friend of George Mallory, and again that name was mentioned. Mallory, the paragon of climbers. My young mind took it all in.

I lived and dreamed mountains on those summer holidays. To me Goat Fell, the highest of the Arran hills, looked uncannily like Mount Everest when viewed from the south; indeed it does to me even now. And it is almost exactly a tenth of Everest’s height. I remember cricking my neck back and back on the Strabane shore and trying to count out ten Goat Fells standing on top of each other. I couldn’t imagine anything so impossibly vast. How could anyone climb so high?

Eventually, when I was 13 and he was 81, I met Uncle Hunch.

We were at the memorial service of my great-aunt Dolly, who was one of the Quaker Cadburys. She was wealthy and lived in a large country mansion. I remember her house had a wide, open, red-carpeted spiral staircase for the family, inside of which was an enclosed stone staircase for the servants. I would race up the outer stairs past glass-cased model steam engines and then clatter down the inner, hidden stairs. We, the poor relations, used to receive a huge box of Cadbury’s chocolates every Christmas from Aunt Dolly, and I was particularly fond of her for her gentleness and the P. G. Wodehouse books she used to pass on to me.

Her death was a shame, I thought, a further distancing from a more romantic past. But oddly enough, I was about to be more firmly connected with that past.

I remember standing on the lawn outside Verlands and looking up at Uncle Hunch – the legendary Howard Somervell, who was actually a cousin, not an uncle.

He really was an extraordinarily gifted man: a double first at Cambridge, a talented artist (his pictures of Everest are still on the walls of the Alpine Club) and an accomplished musician (he transcribed the music he heard in Tibet into Western notation). He served as an army surgeon during the First World War and was one of the foremost alpinists of the day when he was invited to join the 1922 Mount Everest expedition. He took part in the first serious attempt to climb the mountain, and his oxygen-free height record stood for over 50 years. General C. G. Bruce, the expedition leader, described his strength on the mountain: ‘Stands by himself … an extraordinary capacity for going day after day.’2 (#u1985ee65-27cf-4aee-9e08-3b1ab548d30e)

Furthermore, the great explorer Sir Francis Younghusband said that of all the Everest men he met he liked Somervell the best.3

At that stage in my life I knew nothing about this, I was only interested in the incredible story he was telling me. He was a stout old man by then, with the slight stoop that gave him his family name, but his voice still contained the excitement of his twenties youth.

‘Norton and I had a last-ditch attempt to climb Mount Everest, and we got higher than any man had ever been before. I really couldn’t breathe properly and on the way down my throat blocked up completely. I sat down to die, but as one last try I pressed my chest hard’ – and here the old man pushed his chest to demonstrate to his fascinated audience – ‘and up came the blockage. We got down safely. We met Mallory at the North Col on his way up. He said to me that he had forgotten his camera, and I lent him mine. So, if my camera was ever found,’ said Uncle Hunch to me, ‘you could prove that Mallory got to the top.’ It was a throw-away comment that he probably had made a hundred times in the course of telling this story, but this time it found its mark.

Gripped by Uncle Hunch’s story, I discussed it endlessly with my father. The mystery seemed simple enough. Mallory and his young companion Sandy Irvine, on their desperate last attempt to climb Mount Everest in 1924, had just disappeared into the clouds. No one knew whether they had succeeded or not. When a British expedition finally got two men to the top in 1953 they looked for signs of the pair but found nothing. The only way of proving their success would be to find Somervell’s camera on a dead body, develop the film and discover a photograph of them on the summit. The story of Mallory and Irvine gripped my imagination. I read all the climbing books I could lay my hands on, and dreamed of being a mountaineer.

I had an idyllic boyhood in some ways. We were living in Rutland then, a rural part of England where rolling hills modulate into the flat lands of the Fens. This, the smallest of all the counties, is a secret Cotswolds of golden limestone villages, Collyweston stone slate roofs and fine churches. Our home was an archetypal English village, with a beautiful squire’s hall, a spired church and a huge vicarage dominating a cluster of alms cottages, pubs and farm houses. I went to a Victorian primary school that taught Victorian religion.

My brother Denys and I once scrambled on to the church roof in an attempt to climb the steeple with its conveniently placed stone croquets, intricately carved ornamental bosses about four feet apart. The reason for our climb was a village legend that a drinker in the Boot and Shoe public house had one evening wagered that he could shin up the slender steeple and bring down the weathercock from the very top. He had done so, and had then returned it to its place. The thought of climbing to that ultimate stone point, up there in the pale moonlight, filled me with excitement and dread. We had to try! After getting up a drainpipe in a corner we crossed the lead roof and started up the square tower on the east side. About ten feet up I grasped a stone corbel – and it came off in my hand. We hastily rammed it back into place. The climb was over.

Years later I found out that George Mallory had climbed the roof of his father’s parish church in Cheshire in a very similar way. Boys will be boys.

This idyll ended when I was sent to a local public school. The headmaster was an ex-Guards officer and, like Mallory, I was drafted into the Officer Training Corps as soon as I could polish a pair of boots. I got into trouble because my army boot toe-caps were scuffed by the Scottish heather.

Denys and my father had started taking me out climbing in the summer holidays on the Isle of Arran around the time we moved to Rutland. George Mallory went to Arran in August 1917 to climb with his friend David Pye and test a healing ankle. It was the first time he had walked in the Scottish hills and he enjoyed it:

The mountains themselves are so lovely, and when one gets high … the view of the islands and peninsulas in these parts is like being in some enchanting country – nothing I have seen beats it for colour.4

He stayed in Corrie, a small village on the east coast of the island, from which some of my ancestors came. My Scottish mother was brought up on Arran, and our family decamped to the island every summer holiday to stay with my grandmother. We didn’t live in the Front House, her solid sandstone terraced house in Brodick, but camped in the Back, a tiny, two-roomed cottage with wooden cabins behind it in another, recessive Back. Grandmother came with us, as well. From here, in an atmosphere of paraffin lamps and the smell of damp, come my oldest memories of the island.

The reason for my grandmother’s seasonal move was to make room for ‘the Folk’. Nearly everyone in Arran seemed to let their houses to holiday-makers from Glasgow. Lying in a dominant position in the Firth of Clyde made the island an attractive holiday destination from the late 19th century, but somehow its very popularity blinds people to the fact that it is one of the real gems of the British Isles.

The Scottish poet Robert Burns seemed indifferent to Arran, too. He must have seen its hills from the inland Ayrshire farms where he spent his youth, but he fails to mention the island in any of his writings. I became curious about this: could it be that a love of mountain beauty was just not fashionable in his time and place? Today Burns’s omission seems unaccountable; arriving at the dismal town of Ardrossan to catch the ferry it’s hard not to be impressed by the view across 14 miles of sea – if it is not raining. Then you might just see a dirty, grey smudge. But on a clear day, the island floats there in all her glory.

Arran is ancient. It was an island before the mainland of Britain parted company with Europe, and the mountains here were once as high as the Himalayas, which are youngsters by comparison at only 55 million years old. Now Goat Fell has worn down to just under 3,000ft, and so it is not even big enough to qualify as a Munro, a Scottish mountain over that height. This serves to point out the absurdity of a system based on size.

2

Getting the Measure of the Mountain (#u06d386a6-a3b9-55cb-b70d-5a5c09aa74c9)

As a schoolboy I had become curious about how the height of Mount Everest was calculated. You could hardly bore a hole in the summit and drop a tape measure from the top until you hit the bottom. So how was it done? I found the answer in Aunt Dolly’s 1920s Encyclopaedia Britannica, and I found it even more amazing than the story of the attempts to climb the mountain.

The British in the 19th century were fascinated by exploring their world, measuring its features and naming them. They were making an inventory of their empire, but perhaps they were also trying to make sense of a planet of rock and sea whirling through the universe. They were particularly captivated by India. My missionary grandfather and his medical cousin Somervell – and I in turn – all fell in love with the sub-continent, and my father was born in Nagpur. India is a great, exotic, bohemian mother of our imagination, and the England of my childhood seems a pale reflection of her culture and peoples.

The Great Trigonometrical Survey was commissioned by the East India Company to survey all their lands in the sub-continent. The survey started in 1802, and it was initially estimated it would take just five years to complete the work. In the end, it took more than sixty years, and cost the Company a fortune.

Imaginary triangles were to be drawn all over India, starting at the southern end and eventually reaching the Himalayas over 1,500 miles away. A great arc of 20° would be drawn along the earth’s surface. This would also establish how much the earth flattened towards the poles. The measurements had to be extremely accurate otherwise errors would build up by the time they reached the Himalayas.

The precision the surveyors attained was remarkable. A baseline between two points visible to each other about seven miles apart would be carefully measured with 100ft chains. Later, special metal bars that compensated for the expansion due to temperature were used. If there was a village in the way it would be moved, and 50ft masonry towers were built at the end of the baseline if there wasn’t a convenient hill available. Then a huge brass theodolite would be hoisted to the top of the tower, and the exact angle between the baseline and the sightline to a third point would be measured. Sightings were made using mirrors to flash sunshine at far-distant colleagues, and blue lights were used at night if the heat of the day caused refraction.

A triangle was thus formed and, as every schoolchild knows, if the length of the baseline and the two angles are known, the length of the other two sides can be worked out. This meant that surveyors didn’t have to measure them on the ground.

The height of a mountain was calculated by measuring its angle of elevation from several different places, drawing vertical imaginary triangles this time. This was important, as it meant that the surveyors could now work out the height of distant unclimbed mountains in an inaccessible country.

A typical expedition employed four elephants for the surveyors and 30 horses for the military officers – both groups wishing to avoid encounters with tigers – and more than 40 camels for the equipment. The 700 accompanying labourers travelled on foot and clearly had to take their chance with the tigers.

The survey was begun in the southernmost point of the sub-continent, at Cape Cormorin, very close to where Somervell’s hospital at Neyyoor would later be built.

Begun by Major William Lambton, the survey was supervised for most of its extent by Colonel George Everest, a man noted for his exacting accuracy. When he took over the job the survey equipment used by Lambton was worn out. There was the great brass 36-inch theodolite made in London by Cary, weighing 1,000lb (which had been accidentally dropped a couple of times), a Ramsden 100ft chain that hadn’t been calibrated in 25 years, a zenith sector also by Jesse Ramsden, now with a worn micrometer screw, and a chronometer. These were all repaired by an instrument maker brought in from London, and Everest pressed on with his life’s work.

Ill-health, the bane of many a Briton in India, eventually caught up with Everest, and so Andrew Waugh had to finish off the job. Interestingly, he re-measured the Bidar baseline with the special Colby compensating bars. The error after 425 miles and 85 triangles was only 4 inches in a line length of 41,578ft.

What is not generally acknowledged is that the surveyors often became rich. Knowledge of the terrain was clearly useful. The Chamrette dynasty of surveyors – grandfather, father and son – owned over 1,800 acres, and George Everest bought 600 acres of land near Dehra Dun. The British Empire became wealthy, too, with the possession of this fabulous land. If I were an Indian citizen reading this now I would be feeling fairly angry. The only (poor) defence is that other nations were also playing the Great Game in the region, and partly what drove the British Empire to survey its borders was fear of invasion from the Russian Empire.

Eventually this great endeavour reached the border with Nepal, a land that was forbidden to the British. The surveyors focused their instruments on the far Himalayas, drew their triangles and measured 79 of the highest mountains, including K2 and Kangchenjunga. Eventually they computed in 1854 that the most lofty was a mountain on the remote border between Nepal and Tibet. They had to allow for the gravitational pull of the Himalayan range (which will even distort the surface of a puddle), the refraction of the atmosphere and a number of other variables, and it is a wonder to me that they got the height so close: 29,002ft. It took over 150 years to pin down a more accurate result, although still no one agrees on exactly how high the mountain is. All measurements are now made in metric units, and China insists that the measurement should be made up to the topmost rock, at 8,844m (29,015ft), whereas Nepal measures to the top of the overlying snow-cap, at 8,848m (29,028ft). The US National Geographic Society measurement using satellites came to 8,850m (29,035ft) – a difference of 33ft from the original Great Trigonometrical Survey result, or around 0.1 per cent error. Not bad, considering the pioneers were using telescopes and brass theodolites, aimed from across the border.