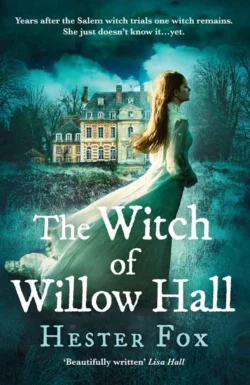

The Witch Of Willow Hall: A spellbinding historical fiction debut perfect for fans of Chilling Adventures of Sabrina

Hester Fox

‘This debut recalls Georgette Heyer, with extra spookiness’The Times‘Beautifully written… The Witch of Willow Hall will cast a spell over every reader’Lisa Hall, author of Between You and MeThe must-have historical read for the autumn, perfect for fans of A Discovery of Witches and Outlander.Years after the Salem witch trials one witch remains. She just doesn’t know it… yet.Growing up Lydia Montrose knew she was descended from the legendary witches of Salem but was warned to never show the world what she could do and so slowly forgot her legacy. But Willow Hall has awoken something inside her…1821: Having fled family scandal in Boston Willow Hall seems an idyllic refuge from the world, especially when Lydia meets the previous owner of the house, John Barrett.But a subtle menace haunts the grounds of Willow Hall, with strange voices and ghostly apparitions in the night, calling to Lydia’s secret inheritance and leading to a greater tragedy than she could ever imagine.Can Lydia confront her inner witch and harness her powers or is it too late to save herself and her family from the deadly fate of Willow Hall?‘Steeped in Gothic eeriness it’s spine-tingling and very atmospheric.’Nicola Cornick, author of The Phantom Tree‘With its sense of creeping menace… this compelling story had me gripped from the first page… ’Linda Finlay, author of The Flower Seller‘Creepy, tense, heartbreaking and beautifully, achingly romantic.’Cressida McLaughlinReaders are spellbound by the The Witch of Willow Hall!‘I could NOT put this thing down!’‘The ULTIMATE page turner!’‘What a story! It absolutely captivated me’‘Historical fiction with a side of romance and major helping of creepiness, this debut novel hits the mark!’‘The book pulls you in from the beginning with many twists and turns. I didn't want to put it down, and could not wait to see what was going to happen next.’

Take this as a warning: if you are not able or willing to control yourself, it will be not only you who suffers the consequences, but those around you, as well.

New Oldbury, 1821

In the wake of a scandal, the Montrose family and their three daughters—Catherine, Lydia and Emeline—flee Boston for their new country home, Willow Hall.

The estate seems sleepy and idyllic. But a subtle menace creeps into the atmosphere, a remnant of a dark history that calls to Lydia, and to the youngest, Emeline.

All three daughters will be irrevocably changed by what follows, but none more than Lydia, who must draw on a power she never knew she possessed if she wants to protect those she loves. For Willow Hall’s secrets will rise, in the end…

Everyone is enchanted byThe Witch of Willow Hall!

‘Beautifully written, with an intriguing plot full of suspense and mystery, The Witch of Willow Hall will cast a spell over every reader.’

Lisa Hall, bestselling author of Between You and Me

‘A wonderful debut novel.’

Linda Finlay, author of The Flower Seller

‘I hope Hester Fox goes on to write many more such novels. I for one will be buying them.’

Kathleen McGurl, author of The Girl from Ballymor

‘I love the novel, and will be looking forward to all new works by this talented author!’

Heather Graham, New York Times bestselling author

And readers have fallen under the spell too!

‘I could NOT put this thing down!’

‘The book pulls you in from the beginning with many twists and turns. I didn’t want to put it down, and could not wait to see what was going to happen next.’

‘Historical fiction with a side of romance and major helping of creepiness, this debut novel hits the mark!’

‘The ULTIMATE page turner!’

HESTER FOX comes to writing from a background in the museum field as a collections maintenance technician. This job has taken her from historic houses to fine art museums, where she has the privilege of cleaning and caring for collections that range from paintings by old masters, to ancient artefacts, to early American furniture.

She is a keen painter and has a master’s degree in historical archaeology, as well as a background in medieval studies and art history. Hester lives outside of Boston with her husband and two cats.

The Witch of Willow Hall is her debut novel.

Copyright (#ua60ad93e-1d40-597b-88ab-6f854e21b3d8)

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2018

Copyright © Tess Fedore 2018

Tess Fedore asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © October 2018 ISBN: 9781474083737

Version: 2018-09-10

For Donna

(and Roland, too)

Not lost, but gone before.

Contents

Cover (#uc6ffd26d-7f58-59ea-b257-de33f230286a)

Back Cover Text (#u34bd7101-8306-5c19-a8fd-d01acf3bfe92)

Praise (#u7eee81a1-a480-54ec-be45-2ee5f6731d8c)

About the Author (#u479d5254-302e-5c70-a4c4-32344dc3b980)

Title Page (#ua3bcc53f-f5a4-5525-ab44-7d6df4bef7c0)

Copyright (#uc26c5907-b9c7-5c6e-8ae9-8bfcc678c048)

Dedication (#ubdaebcc9-0c9a-56a9-9cdf-0d411dc3d785)

Chapter 1 (#u7882c929-df4c-5920-8208-1fc5230004ef)

Chapter 2 (#u9b813992-29d1-527d-944d-472a74c10c16)

Chapter 3 (#ua430ebad-5b7d-58a5-a37b-0badf080e5ae)

Chapter 4 (#ucface779-091b-59ed-9b1a-fe657038b87b)

Chapter 5 (#ucb7085b7-d13b-5a13-9ed3-dbe7aa1d886a)

Chapter 6 (#ub42c4ddd-7497-5dea-a210-2e3d4c979bae)

Chapter 7 (#u79008189-fe48-55bb-9181-b2d0a76d300a)

Chapter 8 (#uf226d8c7-62a0-5a03-85ea-fd98ddadb406)

Chapter 9 (#uc9c0e9a1-2637-5db8-b95d-bc6a2d1343a0)

Chapter 10 (#u6d4399e8-d7b9-580b-a596-a1ade2e1d10a)

Chapter 11 (#u1b95f6c1-ffee-536a-99fe-8c25b415636e)

Chapter 12 (#uea8356d4-810f-5a23-9ffe-21c57f89bb4a)

Chapter 13 (#uc4482732-a7dd-5b18-bdb4-a5a26d2ae526)

Chapter 14 (#ubf75e2d8-7e87-52f7-908e-19e0b37821b4)

Chapter 15 (#ua72bc344-1164-5d09-a54b-ca3d0b5dc0c7)

Chapter 16 (#u5b728491-51d1-5942-b003-4aaa4738ba81)

Chapter 17 (#ue8aaf8e7-2c24-5117-9cac-ab59bc4d6d8e)

Chapter 18 (#u401dbb2c-a26f-52f6-9b1c-f4a072f98c31)

Chapter 19 (#u57fb4a67-f67a-59a4-bb35-d73323b47878)

Chapter 20 (#u3306250e-d491-5261-8540-ea263add9872)

Chapter 21 (#u38be40c2-d241-5ad8-8ef8-628ae80d86eb)

Chapter 22 (#u89889e5b-2e6f-5a4a-990d-61f021eb317c)

Chapter 23 (#u06a29522-17ce-59c4-999d-30dd2ffca802)

Chapter 24 (#uc7b4f260-8dbc-544c-8ee9-d928ae5be420)

Chapter 25 (#uef7677e4-2e1b-5c63-94d8-42f34a7dfbf0)

Chapter 26 (#u564086f6-aee7-5ee8-b897-70b13381d1ca)

Chapter 27 (#u85026014-8c35-56cb-bd55-dbee3d77d239)

Chapter 28 (#u98f3d810-1e4e-51c1-9396-5229adceb52a)

Chapter 29 (#ufbefa6c0-7b57-5d2e-9f5a-550c7d36a911)

Chapter 30 (#uc6e4523f-6711-5a94-9206-33eac61d323b)

Chapter 31 (#u11367ea3-9551-5e05-98af-a335716a7848)

Chapter 32 (#uaf80223c-d8c4-5523-aeb0-73d8a3167254)

Chapter 33 (#u582f6928-ab51-589a-bda6-80179f37402e)

Chapter 34 (#u8f8b68dd-d17f-57ed-aeae-6e3761648318)

Chapter 35 (#u27a452c2-d619-501e-af46-9edb03865e33)

Acknowledgments (#u7c3becf1-77f8-5cc9-a653-13d51e1cd95b)

Extract (#u9305c294-86cc-5a21-b820-33258030bc65)

About the Publisher (#u2286a1ef-188e-5c25-b2a0-77867278d9fe)

1 (#ua60ad93e-1d40-597b-88ab-6f854e21b3d8)

1811

IT WAS THE Bishop boy who started it all.

He lived one house over, with his snub nose and dusting of freckles, and had a fondness for pelting stones at passing carriages. We were the same age and might have been friends, but he showed no interest in books, exploring the marshy fens of Boston, or taking paper kites to the Commons—unless of course it was the rare occasion of a public hanging. Catherine would sit in the window, watching him flee from angry coachmen, shaking her head. “That Bishop boy,” she would say. “It’s a wonder his pa doesn’t put a belt to him, the vicious little imp.”

I’d follow her gaze from the safety of the drapes, ducking back if I thought he might catch me looking at him. In my small, sheltered world the Bishop boy came to symbolize the murky edge of a larger evil of which I had no understanding. When Father lamented British aggression toward American ships, I imagined a fleet of freckled boys with sandy hair, identical in their blue coats as they drew their swords in unison. If there was news of a killer in the city, then he took on a slight frame, a shadowy figure with a snub nose protruding from his hood. The Bishop boy lurked around every dark corner, responsible for every terrible thing in the world that my young mind could not comprehend.

One day, Father—this was before he had made his fortune and he was still our “Pa”—found a little black cat under the steps at his office, and brought it home as a pet for Catherine and me with the stipulation that it wouldn’t come in the house. Catherine said she was too old to play nursemaid to a kitten, though sometimes when she thought I wasn’t looking I saw her sneak out to the stable with a bit of bread soaked in milk. This was before our little sister, Emeline, came along, so I was hungry for a companion, as Catherine and our brother, Charles, were practically joined at the hip. Every morning as soon as I could be excused from the breakfast table, I would rush out to the stable with a precariously balanced saucer of milk and a tattered hair ribbon that I had appropriated as an amusement for the cat.

It must have been spring, because I remember the heady scent of wet earth and lilacs as I emerged from the house into the garden, my heart light and happy to be free. To this day I can’t smell lilac without a pit hardening in my stomach. And it must have been a Thursday, because Mrs. Tucker who came on that day to teach us French was there; I remember later the way her severe black eyebrows shot upward, her thin lips that never did anything except press into a tight frown, thrown open forming a perfect O, emitting that awful scream.

So it was a Thursday in spring. Usually Bartholomew—I thought myself very clever for this name until Catherine pointed out that Bartholomew was, in fact, a she—squeaked in greeting before I even got to the straw-filled crate that Mother had made for her. The only sounds that greeted me that day were the gossiping swallows and soft whickering of the horses. I slowed my step, not wanting to wake Bartholomew if she was sleeping. I rounded the corner to the empty stall and peeked over into the crate.

I think I knew what I would find there before I even saw it. There was something heavy and terrible about the silence, a disturbance in the air, quivering with secrets. I shouldn’t have been surprised when I saw the blood-flecked straw. Something pure and loving made base, a pile of inert organs and tufts of black fur.

I don’t know how long I stood there, unable to comprehend what lay in front of me, and after this it gets hazy.

I found myself outside, storming into the street with pounding ears and a film of red behind my eyes. It’s funny, because for all the racing of my heart and the tightness of my throat, I have the recollection that I was remarkably calm. I had a sense of purpose, of what needed to be done. But for all that, I still didn’t know how I was going to do it.

The Bishop boy was there. He blinked when he saw me coming, the slow, lazy blink of someone who either doesn’t know what they’ve done, or else doesn’t care. Why, he didn’t even try to hide the fact that there was fur on his cuffs, that his brown shoe was damp with splattered blood. He just gave me that infuriating blink and then turned back to the stash of pebbles he was collecting.

There must have been at least a dozen people gathered around on the cobblestones by the time Tommy Bishop lay whimpering and crying out for his mother. That was when I came back to myself, when I realized just how many eyes were on me and what I had done. From somewhere behind the crowd Mother was calling to be let through, elbowing her way past a fainted Mrs. Tucker and snatching me up before a mob could form.

More than anything else I was frightened of what would happen to me. Would she tell Father? Would I be sent away? Catherine had told me that bad children were often sent to Australia, a desert land where they were forced to build their own prisons out of sunbaked mud bricks. The only food was rats roasted on spits, and there wasn’t a book on the whole island.

Mother installed me on a bench in the garden and I drew my knees up to my chest, willing myself to disappear. A tear welled up as I thought about the little body in the stable. Would they at least let me give her a proper burial before shipping me off to Australia? I hastily wiped the tear away and braced myself for my sentencing.

But it never came. Mother took my hand in her own, her soft brown eyes studying my face, the lines around her mouth tight with worry.

“So,” she said at last, “that answers that.”

I had no idea what the question was, or even what exactly had been resolved, but something in her tone told me I wasn’t going to be punished, and in my young mind that was all that really mattered.

She went on to tell me that I must never speak of what happened in the street again. If anyone were to ask about it, we would say only that it was a scuffle. Children get into scrapes all the time and sometimes they get out of hand.

“And Lydia,” she added before I could dart away back to the stable, “you must never show the world what it is that you have inside of you.”

So I carry it like a little locket, tucked deep down beneath my breast, never taking it out to open, but knowing that it will always be there should I choose to peep inside. We would never speak of it again after that day, but Mother made it clear that should it come bubbling out of me again, that we could find ourselves turned out of our home, or worse.

No, I never considered that we might be turned out for other reasons, and certainly not for the rumors that surround us now—which are just that: rumors.

2 (#ua60ad93e-1d40-597b-88ab-6f854e21b3d8)

1821

“IT MIGHT AS well be the edge of the world,” Catherine says with disgust. “As if being banished weren’t humiliation enough.” She huffs and throws herself back against the padded carriage seat.

Mother assures us that it is neither banishment, nor the edge of the world, and that if it hadn’t been for the horse that went lame outside Concord it would be a three-day journey from Boston. It might only be a matter of a few days, but as our new house looms into view, all I can think of is how isolated it is, how utterly cut adrift we are from everything familiar. No more rows of neat brick houses, no more cobblestone roads filled with the traffic of a bustling city, no more safe and sheltered existence.

“You’ll be real country girls now.” Mother follows my gaze out the carriage window to the jutting silhouette of our new home. Ever since that spring day ten years ago, there’s been a pooling of sadness behind Mother’s dark eyes, a heaviness to her once pretty face that has only worsened with the events of the recent months. “There’s a ballroom on the third floor, and we’ll hold parties and dinners. You’ll be surrounded by fresh air and good, simple people.” Desperation tinges her words, and Emeline stirs in my lap, looking up at me to confirm that this is something good, something that we sought out rather than were forced into. I force a thin smile for her sake.

“A ballroom?” Catherine perks up a little, craning her head to get a better look as the carriage lurches up the drive.

Willow Hall is fine, I will give Father that. Three stories of pristine white clapboard, and windows flanked with crisp green shutters. A carriage house abuts it on one side, a barn on the other. It stands in defiant contrast to the forested, sloping hill behind it. I try to imagine the windows glowing yellow in welcome, a stream of merry visitors jostling and laughing their way up the winding drive and I fail. It may be a handsome house, but this place will never be home. Yet at the same time I want to untether my heart, toss it up into the sky and let it take wing. There’s a wildness here that, if nothing else, holds promise, possibility. Who needs society? What has it ever done for us?

A cloud passes over Catherine’s face and she must be thinking the same thing, though for different reasons. She slides the little curtain closed. “There won’t be any parties though, will there? No one will come. Fifty miles from Boston is still too close. We could be in Egypt and still it would be too close. We should have at least gone to London,” she says with a wistful sigh. “If we were going to run out of town with our tail between our legs we might have at least gone there.”

Everything is London with her these days, a faraway Mecca or Xanadu where the world is bright and polished, gleaming with possibilities.

Mother doesn’t say anything, just wipes at her perspiring brow and twists the handkerchief through her hands over and over. Her ideas for painting our situation in a rosy light ended with the balls, and now she has given up. Poor Mother, who has sacrificed her prized garden and the house she called home for near on two decades. Catherine, Emeline and I are young and adaptable, but she is like an uprooted oak, and I fear she will wither and fade. And Charles...well, I’m sure Charles is fine, wherever he is.

It’s nearly dusk when the carriage comes to a stop. Apricot and coral streak the country sky, and fireflies flit across the broad lawn, blinking at us from the surrounding trees. My neck prickles under the scrutiny of a thousand eyes.

Emeline is the first to alight, throwing the door open before Joe even has a chance to come around. She’s running ahead, up to the imposing white house. I follow her, slowly, stretching my aching back and wiping the sweat from my lip.

We put our feet on the hard ground, take in the night air and look around as if this whole place has sprung up for us and us alone. Not just the house, but the ancient trees, the watching insects, the stars and even the moon. But they have all lived without us for lifetimes that make our own look like the blink of the eye. The house, with its strict walls and severe lines, is shamefully out of place, something modern dropped down somewhere as soft as feathers, as twisty and spreading as willow roots. How do the trees and the insects and the stars and the moon like it, I wonder? How do they like to have to share their secret lives with us now?

Catherine unfolds herself, complaining of a headache. It was fatigue earlier in the day, and before that nausea. She calls out to Emeline to slow down, but Emeline is already running around the side of the house, free as a colt feeling grass under its hooves for the first time, her little spaniel Snip chasing at her heels. I haven’t seen her so happy and carefree for months. Mother gives directions for the trunks to be unloaded and brought in, then sweeps up to where Catherine and I are standing. She catches Catherine’s grimace.

“Our nearest neighbor isn’t for some distance and she won’t bother anyone.” All the same Mother yells after Emeline to mind her dress.

Catherine grumbles something, and then picks up her skirts and stalks off to the front door where Father has finally emerged. He stands aside as the trunks are loaded in, and gives Mother a cursory peck on the cheek in greeting. When Catherine passes he affords her a chilly “Hello,” and then looks away.

“How lucky for us that your father had this house built as a summer home,” Mother had said last month when it became clear that the rumors were not going to abate, that Father was not going to be able to continue with his business in Boston anymore.

Luck doesn’t have much to do with our new circumstances, but it calmed her to speak of it in such terms. Father had come out to New Oldbury the week before to meet with his new business partner here and tour the mill in which he was investing. It was a mercy that he was able to furnish the house and make it all ready for Mother; I don’t think her nerves could have taken the prospect of starting over in an empty house.

Once the trunks are all inside, Father bids us good-night and disappears back into his study, leaving us to explore our new home.

“New Oldbury,” Catherine says with a grimace. “Whoever heard of such a ridiculous name?” She’s inspecting the rooms, running a gloved finger over the white mantel in the parlor. The house is more opulent, grander than I ever could have imagined. There’s even a room for the sole purpose of dining. It’s papered in a panoramic scene of people enjoying a French garden, some in boats drifting past marble ruins, others lounging on grassy banks with parasols and baskets. I imagine myself slipping into that static glimpse of paradise. Could I row the little boat out past the horizon? Or would I find that the world ends where the artist’s brush had painted a thin blue line?

Everything is the best, the newest. Father has spared no expense, and yet my heart only drops deeper as I wander through each room. All the silk drapes and woodblock wallpaper in the world can’t mask the fact that we’re here as outcasts. All this wealth, and to what purpose?

I move to the library. A stern ancestor of Mother’s on the Hale side glowers down at the finery from beneath her starched white cap. When I was little Catherine told me that the woman was hanged as a witch in Salem, and tried to frighten me by saying the eyes of the painting could see everything I did. I was never scared of the woman herself, but of her fate. Her face, to me, always held more of a grim warning than anger. “Do not make the mistakes I made,” she seemed to say. What those mistakes were, I have no idea. To this day I can’t pass under her portrait without a shiver running down my spine.

Mother hardly notices the decorations and furnishings, and bids us good-night and retreats to find her bedchamber. Dark rings hang under her eyes and her color is poor. It’s hardly surprising; the house is stifling in the July heat. Father hasn’t aired the rooms and it feels as though the gray, paneled wallpaper and golden drapes are closing in on me. I’m just about to step outside for some air when Emeline comes bounding back in, cheeks flushed, Snip bouncing at her side.

“There’s a tiny house up the hill behind the house! It doesn’t have any walls but there are benches and a little steeple. And a pond! Lydia,” she says, taking my hand in hers, “a pond. Do you think there’s mermaids in it? Can we go back and look for them?”

I’ve been reading to her from a book of poems, and one of them mentioned the mythical creatures. All she can think about since then is finding a mermaid and then no doubt exhausting it with a list of questions about life beneath the water.

“Why don’t we take a look tomorrow in the daylight? It must be well past your bedtime now. Let’s find your trunk and get you into bed.”

Catherine has thrown herself down onto one of the plush, upholstered chairs, her hand resting on her stomach. “Let Ada do it, that’s what she’s for.”

Emeline is on the floor playing with Snip, the mermaids apparently forgotten already. I lower my voice so that she can’t hear. “Do you have to be so harsh? Everything she ever knew was in Boston. I can make it easier by tending to her myself.”

Catherine rolls her eyes. “Oh, please. It’s a grand house in the country, she’ll be fine. Soon she’ll completely forget what it was like to live in the city anyway.”

A headache is coming on, and perspiration drips down my neck. All I want to do is get out of my dress and into a bed with cool, clean sheets, not argue with impossible Catherine. But I can’t help myself. “So you’ll be happy here then? In your grand house in the country?”

She bristles. “Boston was becoming tiresome. I—”

“It was tiresome because of the situation you put us in,” I snap.

There’s a tug at my skirt, Emeline is staring up at me. Catherine presses her lips and looks away. I sigh. “I’m taking her to bed. Good night, Catherine.”

Catherine nods, her shoulders slumping forward. She looks so tired, and for a moment I almost feel sorry for her. But then I remember why we’re here in the first place, and my sympathy evaporates.

* * *

The eerie stillness of this new place makes falling asleep almost impossible. I don’t know how long I lay in my new bed, my body tensed, flinching at every faraway hoot of an owl that punctuates the night like a gunshot. It feels like hours later when the owl finally grows weary of its endless mourning and takes wing. My eyes are just starting to grow heavy when a terrible sound cuts through the silence.

Sitting bolt upright, I hold my breath as it comes again. It’s a slow moan, a keening wail. The sound is so wretched that it’s the culmination of every lost soul and groan of cold wind that has ever swept the earth.

My blood goes cold despite the stifling heat. I don’t know where my parents’ bedchamber is, and although the wail comes again and sounds as if it were in every plank of wood and every pane of glass, it must be Mother. She hasn’t cried like this since Charles left, but the stress of the move must have taken its toll. I slump back into my pillows, guilty that I can’t gather the strength to go to Mother and comfort her.

Kicking off the sticky sheets, I lie back down and close my eyes, trying to block out the awful noise. At last the wail builds and crescendos, trailing off into nothing more than an echoing sob.

The first dim light of morning is breaking when I finally drift off to a fitful sleep, unsure that the cries were anything more than a dream.

3 (#ua60ad93e-1d40-597b-88ab-6f854e21b3d8)

FATHER IS OUT on business, so it’s just Catherine, Emeline, Mother and me around the breakfast table the next morning. Some of the color has returned to Mother’s face, and she’s smiling as she butters her toast, listening to Emeline chatter on about the pond and all the merpeople that are just waiting to make her acquaintance. Perhaps Mother’s crying last night was what she needed, a cathartic release of all the stress and sadness that has led up to this move. Catherine is looking less well, her face pale and drawn as she sips her tea. I’m sure I don’t look much better after my waking night.

I give Emeline’s head a light pat before slipping into my seat and reaching for the teapot.

“...and Lydia is going to take me to the pond today so I’ll probably be late for dinner if the mermaids are out and we get to talking,” Emeline finishes triumphantly.

Before I can tell her that it looks like rain, Ada inches her way to the table, clutching a letter in her trembling hands. I catch Mother’s eye. We used to have a bustling household that included five servants, a cook, a gardener, a host of rotating tutors, and drawing, painting, and dancing instructors. It was hard enough to hold on to the tutors before, but then the rumors started and one by one they all resigned. Now, we only have Joe and Ada, and I have taken Emeline’s education into my own hands.

“Ada, what do you have there?” Mother puts down her napkin and holds out her hand for the letter.

Ada is a slip of a thing, and her perpetual nervousness has only intensified since all the trouble began. Only a couple of years older than me, she’s been with us since I was Emeline’s age, and sometimes feels more like a sister than a servant. She hesitates before surrendering the envelope. “Letter from Mr. Charles, ma’am.”

Catherine’s knife clatters to her plate.

Mother’s face freezes, and she drops her hand like a lead weight. She gives a little sniff, and turns away, folding and smoothing her napkin over and over. This has been Mother’s way of dealing with everything lately; if she pretends there’s no problem then it simply doesn’t exist.

“Give it to me,” Catherine whispers.

Mother gives Ada a tight nod, and Ada slowly extends the envelope; she jumps as Catherine snatches it and runs back up to her bedchamber.

Emeline narrows her eyes. “Charlie did a bad thing,” she says.

Mother doesn’t say anything, but begins peeling an orange as if it’s responsible for all our family’s woes, juice squirting onto the tablecloth. I will her to explain everything to Emeline, to take some control. Her head is bent low, fingers digging into the pulpy flesh. I wait. But as usual she says nothing.

“Charlie didn’t do anything bad,” I say. “Those stories weren’t true. Look.” I point out the window at the gathering clouds. “It might not be the best day for the pond, but we could take the carriage into town and take a peek at the shops.” What kind of shops there are in a little village like New Oldbury I have no idea, but I want to get out of the house. We’ve been here only a day, but it already feels too full of ghosts of a happy family that might have been.

* * *

The town center proves to be that in name only. A run-down dry goods store with peeling letters advertises coffee, and a little white church sits at one end of the town green. That’s it. No theaters, no gardens and, worse yet, no bookshops. Yet there’s something charming about the simplicity of the square and the dirt roads that wind up and around it; there’s no stink of fish wafting off nearby docks, nor cobblestones caked with horse droppings. I take a deep breath and smile encouragingly to Emeline. Here’s our fresh start, not in the suffocating walls of Willow Hall with all its pretensions, but in the blue sky above it, the little town surrounding it.

It doesn’t take long for our fresh start to lose its rosy glow.

Two middle-aged women walk arm in arm, stopping to watch us unload from the carriage, Snip nipping at our dresses. They share a whispered word or two, and then creep a little closer to get a better look.

The first woman lowers her voice and leans in toward her companion. “Those are the Montrose girls, you know. The family just came from Boston.”

“Oh?” The other throws a glance back at us over her shoulder, greedily drinking us in. She remarks that Catherine is a true beauty with her auburn hair and green cat eyes. “Wasn’t there some unpleasantness, some scandal involving her?”

The first woman puffs at the chance to explain, to be the one who knows all the sordid details. “Well,” she says, “the whole business makes my stomach turn, I can hardly speak of it.” But that’s a lie, she’s thrilling at the taboo of it, reveling in the currency of a juicy story. “The middle one had to break off her engagement because of it, poor thing. She’s so plain and it was such a good match too. Not likely she’ll find anything better, not likely she’ll find anything at all now.”

My heart drops at the oblique mention of Cyrus. I’ve hardly thought about him these past weeks, except in passing flashes of anger. I don’t miss him. I don’t care what he thinks. But their words sting because they’re true; the only reason we were engaged was because our fathers were business partners. I’m not like Catherine who could have her choice of suitors.

“Yes,” the other commiserates, impatient, “but is what everyone’s saying true? It can’t possibly be.”

They’re too far away now, their voices too low for me to hear anymore, but I understand enough to know what she’s saying. She will embroider it a bit of course, make Catherine younger, more wanton. When she’s done they’ll both go home, feeling very well about themselves indeed.

My eyes bore into their backs as they walk away until Emeline tugs at my sleeve. Thunder rumbles in the distance and I put on a brave face for her, taking her by the hand. If Catherine noticed the two women and their sharp eyes, she doesn’t say anything, instead she fans herself with her gloves and looks around at the little town. “I can’t fathom why on God’s green earth Father had to choose this forsaken place over all others. There isn’t even a dress seller.”

He chose it because of the river that runs through the town, powering the mills. Father doesn’t know the first thing about milling—he made his fortune on a series of brilliant speculations—but he has a keen nose for business and knows a good investment when he sees it. The river towns up this way weren’t affected the way the city was during the war in 1812, and a quick profit can still be turned. Knowing this, he had planned to build a small office, and Willow Hall as our seasonal residence. I doubt Catherine would care, let alone understand any of this, so I just point to the little shop across the street. “Maybe they sell ribbons there. Shall we look?”

Mother had wanted to make calls on some of our new neighbors, so I give orders to Joe to return with the carriage in an hour. Joe grumbles something about rain, but there’s nothing to be done for it so I lead Emeline across the street, Snip tugging at his leash, Catherine trailing us.

Inside the shop it’s musty, a comfortable smell of old leather and dried tea leaves. Emeline leaves Snip tied up outside, and he whines as the heavy glass door swings shut, his claws scratching at the window.

“He’ll be fine,” I say, directing her attention elsewhere. “Look there.” Behind the counter a variety of silk and lace ribbons hang from spools. They’re pretty, if not a little faded, but Emeline doesn’t notice and is already running over to look for a pink one.

Catherine, who tried to feign indifference at first, is beside Emeline, unable to resist the prospect of a new trifle. I watch her running the silk through her fingers, holding different colors against her auburn hair.

The shopkeeper, an affable enough looking man with thinning brown hair, leans over the counter and gives Emeline a smile, the kind adults give children when they aren’t quite sure how to interact with them. “It’s not often I have ladies of such quality in my humble little shop,” he tells her. “I’m very flattered indeed that you and your lovely sisters have chosen to patronize me on this gray day.”

Emeline looks up at him with unmasked curiosity, studying him. I can see the wheels in her head turning as she tries to decide what he means by this. Before she can say anything, I hurry to her rescue. The shopkeeper can laud his insincere platitudes on me or Catherine, but he shouldn’t direct them to a little child.

I give him a tight smile. “We’re newly arrived in New Oldbury, and thought to explore the town today.”

Even though my tone should make it clear that I’m not looking for a conversation, he turns his smile on me. “Is that so?” He couldn’t care less if we had just dropped out of the sky, but his eyes are trained on the pearl earrings on Catherine’s earlobes, the fine weave of her shawl. “And how do you find New Oldbury? Where in town are you living?”

“Willow Hall,” I say shortly with another tight smile, trying to make it clear that the conversation is over.

He’s watching Emeline running her finger over a pink velvet ribbon, but at this he looks sharply back at me. “Is that so? Hadn’t thought that anyone was going to live there. I’d heard something about it being a summer house.” He bends over again to Emeline and dramatically raises his brows. “There are stories around here that the place is haunted. All manners of ghosties and goblins.”

I could slap him for trying to scare her. But Emeline just returns his patronizing gaze with wide, unblinking eyes. “Ghosts? What kinds of ghosts?”

“It seems that every town has its local ghost stories,” I hurry to interject, but I already know that Emeline will be demanding ghost stories now in addition to the mermaids. “It’s so very quaint.” This time I firmly turn my back on him and confer with Emeline on the different merits of the ribbons while Catherine joins in to agree or disagree with me.

Rain begins to patter on the roof, first soft and indecisive, then a steady drumming. For a moment everything is normal and right; I’m shopping for hair ribbons with my sisters. It’s cozy, and I can almost forget the two women in the street and their greedy eyes, the overly eager shopkeeper.

Emeline drops her ribbon and frowns. “We can’t leave Snip out there, he’s going to get drenched.”

Mother won’t be pleased to have a wet, smelly dog in the house so I pay for Emeline’s ribbon and we plunge out into the sticky July rain, only to find that he’s gone.

“He probably just went in search of somewhere dry. He can’t be far.” But as I look up and down the deserted street, I’m not quite sure where that would be.

Catherine frowns, pulling her fine Indian shawl—a gift from Charles before he left—up over her head to keep her hair dry. I think she’s going to say something snide about just letting him go, but instead she points to the town green where a flash of white cuts through the downpour. Without waiting for us, Emeline hitches up her skirt and takes off.

Snip thinks it’s a game. As soon as Emeline draws near, he freezes, wags his tail and then bounds off again. Catherine and I struggle to keep up with Emeline who has the speed of a gazelle, our dresses longer and heavier in the rain.

As if on cue, thunder cracks in a long, grumbling roll. A moment later the sky flashes yellow. We’re well out of the center of town now, and Catherine is breathing heavily trying to keep up. “We can’t stay out here, we have to get inside,” she says, panting.

I have no idea where we are, Snip has taken several sharp turns on his merry romp. We’re on a narrow road—really more of a dirt track—crowded with angry trees that threaten to crack in the heavy rain. Joe may be back with the carriage soon, but he won’t know where we’ve gone.

“There!” Catherine points to a little footpath that cuts through the trees and brush. I can just make out a shingled roof through the clearing.

“Emmy!” I call out after Emeline, who has lost some of her stamina and is suddenly looking overwhelmed in the unfamiliar surroundings. “Leave him for now.”

Reluctantly, she follows as we run toward the building, some kind of old factory or mill. Overgrown with ivy and weeds, the mortar is crumbling around the foundation and the door lintel sags with rotting wood. At the very least it doesn’t look as though we’ll be bothering anyone.

My feet are cold and slippery inside my shoes and my dress is completely plastered to my body. Catherine and Emeline haven’t fared much better, their hair undone and straggling down their necks. So much for our diverting trip to town.

We huddle under a little overhang on the side of the building, empty barrels and upturned crates with old straw the only furniture. Outside the rain comes down in sheets.

“Poor Snip,” Emeline says. “He’s probably so frightened. And how will he find his way home? We’ve only been here a day. He doesn’t know the way back.”

Seeing the way Snip was enjoying himself, I doubt he is afraid and tell Emeline as much. “He has a keen nose, I’m sure he can sniff his way back.”

“The rain will have washed all the scents away though,” Catherine unhelpfully volunteers, and I give her a sharp look over the top of Emeline’s head.

We watch in silence as the trees thrash and bow, and jump when a particularly large branch snaps to the ground. The thunder eventually rolls off into the distance, the lightning following in its wake.

“Look!”

Emeline jumps off her seat and points out into the woods, where I can just make out the outline of Snip before he disappears into the trees. “We have to go get him!”

“I’m done chasing that stupid dog. My feet are wet and blistering, and there’s no telling how much farther he’ll go.” Catherine looks to me for agreement. “Let’s wait for the rain to stop and then try to find Joe.”

The lightning and thunder might have moved off, but the rain is still drumming down fast and steady. I look between Emeline’s expectant face and Catherine, already steeling myself for what I know I have to do. “You stay here. I’ll go follow him, but if I can’t catch him right away then I’m coming back.”

Emeline pipes up to say something, but I stop her with a stern look. “Mother won’t be happy if you come back even dirtier and with a cold. Catherine, stay with her, and give me your shawl.”

4 (#ua60ad93e-1d40-597b-88ab-6f854e21b3d8)

WHY COULDN’T MOTHER have gotten her a cat, I think as I set off into the thicket behind the old building, wiping rain from my eyes. Cats don’t go romping about in downpours. Cats stay warm and dry in front of a fire, just like I wish I was right now.

Plunging farther into the woods, I give a half-hearted yell for Snip, followed by an indelicate word as my shoe catches against a slick root. There’s no time to stop myself as I go sprawling headfirst into the wet leaves and mud. A rock breaks my fall. My hand smarts, and when I struggle to my knees to inspect the damage, there’s an angry cut running down my palm. It’s no use trying to wipe the dirt from it on my soaking dress, so I gingerly heave myself up the rest of the way, only to step on my hem in the process. There’s a loud tearing noise. Just my luck. I curse again as I stumble forward, reaching for tree trunks to steady myself as I go.

The rain isn’t as heavy here under the thick canopy of trees, but each severe plop still snakes its way down my clothes, vanquishing the last few dry spots on my body.

More than once I stop in my tracks, frozen by the snap of a branch or a clump of leaves falling to the ground. My neck prickles, just like last night when we arrived to an audience of fireflies and forest creatures. I’m a city girl, an intruder, unused to the thousand little sounds of a close woods.

“You’re lucky you have such a sweet little master,” I grumble to Snip, wherever he is. If it weren’t for the fact that Emeline will be heartbroken if I come back empty-handed, I’d be tempted to leave Snip out here to fend for himself.

Something white flashes in the corner of my eye, but when I turn and look closer it’s gone. A shudder runs through my body. “Snip?”

A moment later there’s a rustle behind me and I close my eyes, letting out a sigh of relief. Maybe the end of this unpleasant day is finally in sight. “Well, you certainly took your sweet time. I hope you’re happy with your—”

I freeze at the sound of a heavier tread, my words dying in my throat. The hairs on the back of my neck stand on end, and I don’t have to turn around to know that it’s not Snip behind me.

Do they have bears out here? Or maybe it’s a moose. I once saw a picture of a moose in a book. They’re taller than a man and they can toss you up into the air with their great antlers. But even as I curl my fingers into my skirts, preparing to turn around, I know that it’s not an animal.

I take a deep breath and spin around.

It doesn’t matter that I knew there would be someone there when I looked, I still almost jump out of my skin when my eyes land on the young man that has seemingly appeared out of thin air behind me.

“I’m sorry,” he says quickly, taking a tentative step forward. “I didn’t mean to startle you.” He must see my heart pounding in my throat, because he stops, and his lips twitch up at the corner. “I think I failed on that account.”

My breath comes out in a hiss. “Yes, well, in the state I was in I think anything would have startled me.” I lean back against the wet bark of a tree and close my eyes, waiting for my heart to slow.

I open my eyes. He doesn’t look dangerous. Despite the rain having its way with him, his clothes are fine, and there’s something warm and familiar about his face. I probably look a good deal more suspicious in my torn and muddy dress and bedraggled hair.

He takes his hat off and rakes his fingers through his wet hair, brushing it out of his eyes. “Are you all right, miss? Are you lost?”

“Quite all right,” I lie. I’m not used to anyone—let alone a handsome young man—talking to me as if I weren’t part of the most reviled family in Boston, or an unchaperoned woman wandering the woods in a torn and muddy dress for that matter. “And it’s my dog—or rather my sister’s dog—who is lost. I’m trying to find him.”

“Ah.” He rocks back on his heels, hands in pockets. “A noble reason to be out in such conditions. Mine are much more foolish.”

He doesn’t give me a chance to ask what his reasons might be, and he doesn’t elaborate before asking, “Perhaps I could be some assistance in your search? I’m quite familiar with these woods.”

I should thank him and tell him that it’s not necessary. I should say good-day, turn around, and go find Catherine and Emeline. There is no good and proper reason for me to accept the company of a strange man I found wandering in the woods, even if the man in question looks like he just stumbled out of one of my novels with his fair good looks, a Lancelot. Yet when I open my mouth, the only words that come out are, “I think he went up that way.”

I gesture up the bank and the man’s gaze fixes on my hand. “You’re hurt.”

It isn’t a question so much as an accusation, as if I should have told this stranger the moment I set eyes on him that I had a small scrape on my palm. I open my mouth to protest, but he closes the small distance between us in three long strides.

“May I?” Before I know what’s happening, he’s taking my hand in his gloves, gently wiping away the dirt from the cut. His movements are deft and quick. “You’ll have to wash it when you get home, but this will at least keep any more dirt from it.” He takes his cravat off and I watch him wind the white linen round and round my hand until I can barely flex my fingers.

“There now, that’s better,” he says with a smile as fast and brilliant as the lightning. When he’s done he ties it off neatly. My hand lingers in his for a moment, relishing the warmth, before I remember myself and pull away.

“Thank you,” I mumble.

Perhaps realizing just how close we’re standing, the man steps back with a brisk nod. “If we’re going to find your dog we should do it now while we have a break in the rain.”

I’d hardly noticed that the rain has lightened to nothing more than a misty drizzle while his strong fingers held my hand. “Do you think you can manage...?” He trails off, looking discreetly at the ground. The cool breeze on my ankles reminds me that between my dress and the cut on my hand, I probably look like I’ve been mauled by wolves.

I tug at my bodice and adjust Catherine’s shawl in a vain attempt at modesty. “Perfectly fine,” I assure him, and, as if accepting a challenge, add, “I love a good walk in the woods.”

He inclines his head, a glimmer of amusement in his eyes, and we set off.

We crest the little embankment, the man shortening his strides so that I don’t have to run to keep up with his long legs. I chance a sidelong glance at my knight, wondering what on earth brought him to the woods in a storm at the same time as me.

“He can’t have gotten far. The river cuts through over there, and if he has any sense he’ll have stayed put on this side.”

“I’m not sure sensibility is Snip’s strong point. Chasing his tail, maybe. Or barking at shadows.”

The man’s eyes—arresting eyes, which are somehow blue and green at the same time—settle on me and he flashes me a grin before putting a light hand on my elbow and guiding me up the bank.

I’ve nearly forgotten about my sodden shoes and the stinging from my cut. The fresh, resinous smell of the woods fills me with renewed energy. We’re Lancelot and Guinevere, fleeing through the forest from a jealous King Arthur. Any moment we’ll come upon a white steed and Lancelot will swing me up upon its jeweled saddle and we’ll gallop off together.

“There!”

My dream comes to a halt as I follow Lancelot’s pointing finger down to the edge of the water. It’s not a white steed, but a muddy Snip. He’s gnawing on something, a piece of rotted wood it looks like, as we slowly approach.

Snip eyes the man suspiciously as he slowly advances with one outstretched arm, but doesn’t make any move, just pants contentedly with his tongue lolling out. “I suppose he’s had enough adventure for one day,” Lancelot says as he scoops up the unprotesting Snip and hands him to me.

I almost wish Snip did have some chase left in him so that I could prolong my adventure with this handsome stranger. But he just wriggles around in my arms and plants me with a sloppy kiss, and we head back to the old building.

* * *

“There you are! I was just about to...” Catherine’s words trail off as the man steps into the little porch behind me. Her mouth falls open as her gaze swings up to him, then narrows suspiciously on me.

“Snip!” Emeline is up in a flash, arms outstretched, receiving her wayward pet among a tangle of dirty paws and frantic licks.

“Remember your manners,” I say as I try to brush off Snip’s dirt from my already ruined dress. “Thank Mr....” I flush. The man bandaged up my hand, helped me find our dog, and escorted me back to my sisters and I never even thought to ask his name.

“Barrett,” he says with a small inclination of the head. “John Barrett.”

The name is familiar, but I can’t place it. Before I can ask him why I might know it, Catherine is sliding off her crate, her gaze fixed on Mr. Barrett. She’s regained her composure and is twirling a damp lock of hair around her finger. “Catherine,” she says with an unnecessarily deep curtsy. “We’re indebted to you for returning Lydia to us in one piece.” The sharp look she throws my way and tight tone suggest otherwise.

For some reason I color deeper when Catherine tells him my name. “And the young lady who’s so busy playing with her dog is Emeline,” I hastily pipe up to divert attention away from my flaming cheeks.

Emeline looks up from scratching Snip’s muddy belly. “We got stuck in the storm.”

“Well, I can’t say you’ve chosen the most hospitable of places to seek shelter.” He gestures to the little porch, hat in hand. “This was my father’s mill, and as you can see it’s fallen into disrepair some time ago.”

“A mill!” Catherine exclaims. “How very exciting. We’ve just come from Boston and I don’t think I’ve ever seen a proper mill before.”

Mr. Barrett raises a brow at Catherine’s enthusiasm for mills. “And what brings you to New Oldbury?”

Catherine clamps her mouth shut, so I answer. “Our father has just invested in the cotton mill here.” It’s not a lie, I’m just omitting the other reason. All the same I feel a little stab of guilt.

“You don’t mean...” His smile fades. “You’re Samuel Montrose’s daughters? And he’s brought you here?” He isn’t asking me, he’s talking to himself. “Mr. Montrose never told me that he was planning on bringing a family with him,” he says, his voice roughening at the edges.

He knows. Despite my best efforts at hemming the truth, he already knows who we are and about the scandal.

“Willow Hall was just to be a summer home,” Catherine chimes in, “but we’ll be living here permanently now.” Her voice is light and she’s twirling that damp lock of hair between her fingers like an idiot again.

“You’re to live at Willow Hall permanently,” he echoes, as if hardly processing the words.

“If you’re going to tell us it’s haunted, you’re too late,” Catherine says with a little laugh. “We quite got all the gossip on that score from the shopkeeper.”

Mr. Barrett gives her a sharp look. “What did he say?”

Before Catherine has a chance to answer, something clicks into place in my mind and I know where I’ve heard his name before. “You’re our father’s new business partner.”

He gives a tight nod. “I am.” The mood has shifted in the little porch, and the only one among us oblivious to the tension in the air is Emeline who is singing to Snip while she tries to clean the mud from his ears.

“Ghosts live in our house,” Emeline says, pausing from her ministrations to look up at Mr. Barrett with solemn eyes. “The whole place is full of ghosts. And goblins. You can’t throw a rock but hit a ghost there.”

“Emeline! He never said that.” I give Mr. Barrett an apologetic look. “She likes to embroider the truth.” Emeline starts to protest but I hush her.

But he hardly hears me anyway, and I dare not say anything else. He stands awkwardly in the silence, taking out a soaked handkerchief from his pocket and then putting it back in again. He runs a hand through his thick hair, shaking out some of the lingering wetness. It’s the same color as the golden fields of shimmering hay, which we passed yesterday on our journey.

“Well, I must go, but you’re welcome to stay and dry off as long as you need. Good day.”

“Wait!” Mr. Barrett stops at my cry, looking at me expectantly. “Your cravat,” I say, raising my bandaged hand as if he would possibly want it back, dirty and bloody as it is now.

He opens his mouth, hesitates and then says shortly, “Keep it.” He gives a brief dip of the head, and then he’s gone.

Catherine and I sit in stunned silence. “John Barrett,” she murmurs. “Why wouldn’t Father have mentioned bringing his family to New Oldbury?”

Why indeed? Father was never much for home life, and that was before the scandal. Now he probably wishes he weren’t burdened with us. No, what’s stranger to me is that Mr. Barrett should look so troubled at our arrival. It would be one thing if it had to do with the scandal, but the more I think about it, the more I’m convinced it’s not that. He was surprised to learn that our father had a family at all, and that he brought us here. If he had already known about us, then it would follow that he knew about the scandal.

“Well,” says Catherine standing and briskly shaking out her damp skirts, “I can’t believe Father could be so shortsighted. He might have mentioned that his new business partner was young. And handsome.”

I roll my eyes, and the little chill that had settled in my spine dissipates. The sun is inexplicably burning through the clouds, and the air is heavy with humidity. Steam rises from the road and the prospect of walking back in the stickiness is even more daunting than walking back in the rain. Despite that, there’s a nagging tug in my chest, a rough edge that won’t be smoothed down.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/hester-fox/the-witch-of-willow-hall-a-spellbinding-historical-fiction-debu/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Hester Fox

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Семейная психология

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: ‘This debut recalls Georgette Heyer, with extra spookiness’The Times‘Beautifully written… The Witch of Willow Hall will cast a spell over every reader’Lisa Hall, author of Between You and MeThe must-have historical read for the autumn, perfect for fans of A Discovery of Witches and Outlander.Years after the Salem witch trials one witch remains. She just doesn’t know it… yet.Growing up Lydia Montrose knew she was descended from the legendary witches of Salem but was warned to never show the world what she could do and so slowly forgot her legacy. But Willow Hall has awoken something inside her…1821: Having fled family scandal in Boston Willow Hall seems an idyllic refuge from the world, especially when Lydia meets the previous owner of the house, John Barrett.But a subtle menace haunts the grounds of Willow Hall, with strange voices and ghostly apparitions in the night, calling to Lydia’s secret inheritance and leading to a greater tragedy than she could ever imagine.Can Lydia confront her inner witch and harness her powers or is it too late to save herself and her family from the deadly fate of Willow Hall?‘Steeped in Gothic eeriness it’s spine-tingling and very atmospheric.’Nicola Cornick, author of The Phantom Tree‘With its sense of creeping menace… this compelling story had me gripped from the first page… ’Linda Finlay, author of The Flower Seller‘Creepy, tense, heartbreaking and beautifully, achingly romantic.’Cressida McLaughlinReaders are spellbound by the The Witch of Willow Hall!‘I could NOT put this thing down!’‘The ULTIMATE page turner!’‘What a story! It absolutely captivated me’‘Historical fiction with a side of romance and major helping of creepiness, this debut novel hits the mark!’‘The book pulls you in from the beginning with many twists and turns. I didn′t want to put it down, and could not wait to see what was going to happen next.’