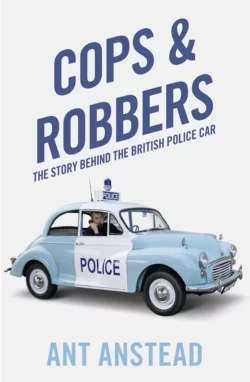

Cops and Robbers: The Story of the British Police Car

Ant Anstead

TV presenter and all-round car nut Ant Anstead takes the reader on a journey that mirrors the development of the motor car itself from a stuttering 20mph annoyance that scared everyone’s horses to 150mph pursuits with aerial support and sophisticated electronic tracking.The British Police Force’s relationship with the car started by chasing after pioneer speeding motorists on bicycles. As speed restrictions eased in the early twentieth century and car ownership increased, the police embraced the car. Criminals were stealing cars to sell on or to use as getaway vehicles and the police needed to stay ahead, or at least only one step behind. The arms race for speed, which culminated in the police acquiring high-speed pursuit vehicles such as Subaru Impreza Turbos, had begun.Since then the car has become essential to everyday life. Deep down everyone loves a police car. Countless enthusiasts collect models in different liveries and legendary police cars become part of the nation’s shared consciousness.Ant Anstead spent the first six years of his working life as a cop. He was part of the armed response team, one of the force’s most elite units. In this fascinating new history of the British police car, Ant looks at the classic cars, from the Met’s Wolseleys to the Senator, the motorway patrol car officers loved most, via unusual and unexpected police vehicles such as the Arial Atom. It’s a must-read for car enthusiasts, social historians and anyone who loves a good car chase, Cops and Robbers is a rip-roaring celebration of the police car and the men and women who drive them.

Copyright (#u34e54ef2-e84b-5007-9aef-133c3f149e8b)

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com (http://WilliamCollinsBooks.com)

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2018

Text © Ant Anstead Limited, 2018

Photographs © Individual copyright holders

Cover photograph © John Lakey

Ant Anstead asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008244514

eBook Edition © May 2018 ISBN: 9780008245061

Version: 2018-05-11

Contents

Cover (#u6e6fedcb-a471-5fcc-9900-447ca1c6651f)

Title Page (#uf345382f-bd4b-5e0f-a78c-3de0e366f04c)

Copyright

Introduction

Chapter One – Creating the Blue Line: The Birth of the British Police Force (#u7ced6d57-8f56-506b-b757-20817abec968)

Chapter Two – These Devilish Machines Scare the Horses, You Know (#ub8e1d4cb-a1d7-55d2-b886-550d8ecacec9)

Chapter Three – Adapt and Arrest (#u754fd2ac-1157-58a9-b38d-3739abf04df6)

Chapter Four – Post-War Peace; London Sets the Way (#u73d2890b-c391-55d8-9f92-6c43019ff93e)

Chapter Five – Send the Area Car (#u1d370b09-e299-570c-a5d7-eed7649dc72f)

Chapter Six – Panda Cars (#u7b175320-d3a9-5771-9437-ff954f6cac27)

Chapter Seven – Traffic Cars (#u182fda03-bfda-5caf-9536-a4389247c149)

Chapter Eight – Police Car Livery and Equipment (#u0256896f-89fc-521a-9320-52d8dd11868d)

Chapter Nine – Commercial Break (#u3dc67e86-6b85-5882-9d03-e8bc40b0e154)

Chapter Ten – Performance Cars (#u763904c6-a377-5da5-be22-c3341fcad04d)

Chapter Eleven – It’s Got Cop Shocks (#uc0262d27-eaa7-544e-b973-6a664727cd98)

Chapter Twelve – Buying Cars – Police Vehicle Procurement and Demonstration Vehicles (#u9c57f049-261e-5412-adfc-a8ee0e112f8f)

Chapter Thirteen – Fantasy Cars (#uf223e8d6-6ac0-579a-8d88-71ad10e8263f)

Chapter Fourteen – Police Driving (#u3cfc23a9-d2ee-5656-9bb8-4cbe82abd00c)

Chapter Fifteen – Policing on the Screen (#u26757a3a-f779-5170-8e30-a726e81599e0)

Plate Section

Footnotes

Acknowledgements

Picture Credits

About the Publisher (#u42d40f69-84a5-5237-9999-b41fa89dcdc8)

INTRODUCTION (#u34e54ef2-e84b-5007-9aef-133c3f149e8b)

I am hugely proud of my police career, and when I look back on the years that I spent as a police officer I do so with a great sense of pride and achievement, knowing that I played a small part in what I firmly believe to be the best police service in the world; an institution that puts the great into Great Britain.

Like any typical teenager, in my youth I never really knew what I wanted to do when I was older, except that I didn’t want to follow my father into the hospitality sector. I was the second oldest of four boys; my two younger brothers were still at school, but my older brother was working as a scaffolder on building sites. I would often join him at weekends to earn extra pocket money, which I blew on car parts for the numerous classic cars I was restoring and selling from home. I had an auntie in the police, though, who was cool and I looked up to her, so I started to research joining the police. At 18 and a half I was just old enough to apply. I never told anyone what I was doing, and it was only in the week that I was packing my bags to go to police college that I told my parents of my chosen career. I was young and full of enthusiasm, and I developed a passion for the law. I loved being within the police family and still consider myself, somehow, part of that; l look back on that section of my life with great affection.

Being a police officer also taught me a lot, much of which I was able to use once I left the service, and that knowledge has given me a great sense of perspective. At the age of 23 I became one of the UK’s youngest armed officers and a full-time member of the TFU (Tactical Firearms Unit). I hold two commendations for bravery and I can recall countless incidents that took my breath away with either fear, laughter, tears or amazement. I look back at those dangerous incidents now in a positive way, as moments of great luck, and I still have the scars from them, which remind me how lucky I am. I owe a lot to the police and I am grateful for the years I spent with them. It helped me to mature, and I have the utmost respect, admiration and affection for my fellow officers.

The police service in the UK is truly a service. I think of it as a service for the people of the nation, which was the original aim, unlike in many other countries where police work has a different ethos. The police taught me about self-discipline, gave me a work ethic and, I’d like to think, some empathy (after all, the best coppering is not always about arrests or box ticking). Also, it taught me, perhaps less usefully in civilian life, firearms training. I learned how to deal with people in all different circumstances. I became fascinated by human behaviour and I use all that learning today in a positive way in my own life. People often ask me if I get nervous hosting live television to millions of viewers, and I simply say ‘No. I’ve had a gun pointed at my face, this is easy’.

Our framework of laws and the ability to enforce them is what makes modern civilised society function – without this we would have no hospitals, roads or even an economy in which to find useful work. The police are the bedrock of a civilised society; we need them in order to function and make our world bearable. We hope we never need them, or meet them, yet we feel reassured that they are there just in case. A great deal of police work goes under the radar because proper policing isn’t shouted about, it mops up the bad in favour of the good. My tutor, Terry Walker, who was about to retire after 30 years’ service when I joined, taught me about humanity and caring for the public that we aimed to protect. I joined in 1999, at a time when he had seen the worst of people during a changing police service that meant officers had to adapt too. Terry always wore his helmet, never carried a baton, never raised his voice and never asked for anything in return. He was an old-school gentleman. I remember him fondly.

I carried with me into the police a great affliction. I was a petrol-head, and the truth is I always have been. From my days pushing Corgi toys around the carpet as a four-year-old, I turned to Lego as a boy and at the age of 14 made my own go-kart from a lawnmower I bought at a flea market. I paid £2 and dragged it the three miles home before taking it apart and putting the engine into a wooden chassis. I never did get it working. I built my first car when I was 16 and bought a vermillion orange MG Midget the moment I passed my test at 17. Cars were where it was at for me. At an early age I was totally and utterly besotted with the looks, sounds, smells and shapes of cars. I had it bad! I could recognise every car on the road and I yearned to drive them. In fact, it was the cars used in police dramas on TV that also helped steer me into policing – who doesn’t love Bodie and Doyle handbrake-turning a Capri (see chapter fifteen on film/TV police cars) and who wouldn’t want to be them when you are 12 years old? I certainly did.

The British police’s relationship with the car and the motorist has at its very heart a central issue that is both contradictory and conflicting. When policing and motoring were both in their nascent stages, PCs were set to catch this new breed of people, the motorists, who were terrorising horses and the public with their frightening and, frankly, it seemed, death-defying 15mph machines. Horseless carriages (the term ‘car’ did not catch on until the early twentieth century) would be an increasingly common feature of UK life for some years before the police started thinking about using them as tools themselves.

Since then the, car has become essential to everyday life. However, it has also become a source of friction between the police and the public. Think about it; if you get burgled or attacked, the police action in catching the criminal and putting them behind bars is supported by 99.9 per cent of the public, but if a traffic cop pulls someone over for doing 83mph on the M1 at 3am, that person is quite likely to feel aggrieved, even though they have, pure and simple, broken the law, just as a shoplifter has. Society’s attitudes still mean that the speeding driver is quite likely to moan about the police to their friends and family, or even on social media, in a way that would be unacceptable for a burglar or mugger, almost as if motoring offences are kind of accepted. The number of times I pulled a car over and I was met with ‘Have you not got anything better to do?’ was alarming. And I’ll let you into a secret. The police feel some sympathy with that, too, because most cops love cars!

Motoring, whether it’s dealing with driving offences or clearing up accidents, represents the vast majority of UK police interaction with the public and is the biggest cause of friction, too. Yet deep down everyone loves a police car, even when they have been done for speeding! Whether it’s a Wolseley cornering on its door handles at 25mph, a Senator spearing down a motorway, or a Morris Minor Panda, the cars used by the police take on a special quality, so much so that countless enthusiasts collect model police cars in different liveries and particular legendary police cars have become part of the nation’s shared consciousness.

That love for the police car and the men and women who drive them is exactly what this book investigates and celebrates.

And, like many people today, I share that love affair with the Great British police car.

So I joined the police …

There have been a number of stand-out moments during my time as a police officer. I joined in what I can only describe as a period of ‘pre-red tape’. Lots of crazy stuff happened. While the police service brought me great enjoyment and I experienced some incredible events, I also saw great hurt and sadness. People can be damaging to each other, and I have witnessed at first hand the very worst of human behaviour. Researching this book and revisiting this period of my life has brought back many positive and negative memories, but I will share with you just a handful of those lighter memories, which whilst writing have made me laugh out loud and cry at the same time. The truth is, in the years I spent in the police, most of those stories are unrepeatable in a book celebrating police cars, and some events I have simply emotionally moved on from, blocking them from my mind. I was young, and revisiting this period in my life has made me reflect on the small impact that I made on public safety and that quite often the day-to-day role of the police officer needs to be secret. In truth, the public cannot know, and I think deep down they don’t want to know, what it is that the police really do.

When I joined, a senior officer described being in the police as 95 per cent mundane boredom and 5 per cent total utter fear. And in some ways he was right. As an officer of Hertfordshire Constabulary I spent the early part of my career in the affluent, rural area of Bishop’s Stortford. Staffing levels were so low I spent the majority of my two years there policing solo. The public perception was that there was a whole army of police officers patrolling the streets. Truth is, there were often only three of us. Three! Covering an area from the Essex border to the east, Cambridgeshire border to the north and as far south as Ware, the town in which I lived. This huge amount of space was known as part of ‘A Division’.

A Division was so vast that to police it effectively we needed to drive – quickly! Hertfordshire Police allowed you to drive cars based on passing various levels of driving qualifications. The entry level driving qualification was known in-house as a ‘G Ticket’. Pass this basic test and you can drive a marked police vehicle – but that’s all: no blue lights, no rapid response and certainly no car chases. It was simply a marked police taxi to get from A to B. I spent many months policing Bishop’s Stortford on a G ticket, and I remember the car of choice fondly, my first ever police car. It was a P-registered Vauxhall Astra – the rubbish one with rounded rear end and awful plastic bumpers. It had grey velour seats with that familiar generic car pattern, and the heater didn’t work. It was the most basic of cars, with a single cone blue light on the roof. This car was slow – so slow – but it got me around my patch brilliantly, never missed a beat. Boy, that car could tell some stories …

There’s something remarkable about driving a police car. It stops everyone. People stare, people behave differently, people certainly drive differently when near a marked police car. I became all too familiar with the varying degrees of public reaction and relied on that response when policing. The car, and of course the uniform, became my asset every day. The car itself became a tool for me in so many different ways; it carried a vast amount of items, it blocked roads when needed, and it became an ambulance when called upon, a refuge for victims, a safe place for informants, an escape when in danger and even a weapon when all else failed. It felt like an armoured vehicle because of everything it stood for, yet all it had was a badge on the door and a blue light on the roof – a blue light I couldn’t even use! For me it was what the car represented that made it invincible. I drove that car across every inch of A Division. I got to know my patch so well, and got to know its residents, too. In the UK we are very lucky; we police with consent, with the majority of the public behaving like law-abiding citizens and crime being committed by a small minority. It meant I saw the same offenders over and over. I got to know them, and they got to know me, too.

Once I had established myself as a local police officer I pestered my sergeant on a daily basis to let me qualify to drive with blue lights. I cannot emphasise enough how frustrating it was for me to listen to the car radio for crime and public calls for assistance, knowing I had to drive there like another car in the daily traffic, to be literally sitting at the lights while a burglary was in progress was not what I joined the cops for! The ‘Yankee’ car was qualified to attend on ‘blues and twos’ and it would often pass my Astra, waving at me while weaving through traffic. I wasn’t in the police long before I knew that I needed to drive a police car properly. I needed to get myself a Yankee ticket. And quick.

The Yankee qualification was a great course. I remember my instructor Vince really well. He was a very dry man who spoke in a monotone, and who, truth be told, really just wanted to ride police motorbikes and tell bad jokes. It took me two weeks to pass the course, which I did whilst driving up and down the country in an unmarked car with two other officers also itching to be allowed to be let loose in some county metal. After the initial days we all became quite familiar with each other, as you would when spending all day together trapped in a car. We covered various aspects of driving and I learned a lot from Vince, including how dark one man’s sense of humour can be. Once Vince felt confident that we were competent, we would BLAT (blues and twos) in a police car to different locations across the UK. Vince would start each day declaring our intention, ‘Today we are going to Southend to buy chips’. And that’s what we did. I still look back and think I had the coolest job. The Yankee course was all about passing; the humiliation of not passing would have been career-ending, and my group would never have let me live it down. Plus they all knew I was a car guy! I had to pass. At the end of the course I was handed a certificate, a piece of paper that said: ‘Anthony Anstead. Response Driver’. I still have it, in fact. And that was it, my ticket to get me to the front line of policing. My police career was about to change forever.

Once I was a response driver, A Division policing instantly became different. I could now attend all incidents as a first response. I could stop cars and chase vehicles. So far I had by default been somewhat protected from the public, but now the safety catch was off and I saw the real side of front-line policing. The really bad bits.

My first fatal car crash was horrific. It was on the A120 between Little Hadham and Bishop’s Stortford. It was a night shift, around 3am, and three young lads had stolen a lorry, set fire to it and left it in the layby, making off in a second stolen vehicle. In their haste the driver lost control of the car within 100 yards of the dumped lorry and turned it upside down. Both front passengers left by the windscreen. The driver was killed instantly and was lying in the road when we arrived, while the other was alive but had serious head injuries. He was holding his face together like it was a latex mask split down the middle. The rear passenger somehow managed to crawl free and he ran off, nice chap.

As I got closer to the scene, I used my car to block the road at the Bishop’s Stortford end and radioed for a roadblock the other side, but I knew assistance was a fair distance away. I could see the lorry on fire at the top of hill and assumed it was involved in the crash. I ran to see if there was anyone inside but the flames were so bad I couldn’t get close. I passed the lorry and used cones from my car to block the road. I asked for fire brigade and ambulance while sitting in the road with the injured man, near his dead friend. I was bandaging his head with blood pouring everywhere. He was silent, and it must have been the shock that prevented him from feeling the pain from his injuries. And the sight of his friend’s body. It was a strange moment. It felt like hours until assistance arrived, and once I was cleared from the scene I had a few moments to clean myself back at the station before I was then sent at 6am to a report of a broken window at the local Tesco. My Yankee ticket took me to the coal face of incidents and that night became the start of familiar relationship with RTAs, which I attended on an almost daily basis, as Hertfordshire has some fast open roads. I’m often asked if, as a car guy, I like motorbikes, and there’s no doubt that, because of this period of my life, and attending numerous bike crashes, my answer is a resounding no.

I conducted numerous traffic stops, mostly mundane for small incidents of speeding or poor driving, and often I just had to have a peek at a car that didn’t quite look or feel right. One stop that stands out was in South Street on a sunny afternoon. I was at the traffic lights and an estate car passed me going the other way. The boot was wide open, hinged upwards, and a young man was sitting on the tail of the car with his legs dangling over the edge towards the road and holding the front of a 15-foot rowing boat on his lap which had some wheelbarrow wheels on the rear. No tow bar, no trailer, just this kid holding a boat that was being pulled along by a car. It was one of those ‘what did I just see?’ moments. I quickly spun my car round and pulled the car over as it got to over 40mph. Just a bump in the road, a clip of the kerb would have dragged that kid out of the car. And they couldn’t really see what the issue was – what was wrong with dragging a boat by hand out of the back of the car? There’s no real obvious ticket for such an offence, but, needless to say, I didn’t allow them to drive a moment longer.

One evening around midnight I was patrolling the edge of the A Division near the M11 junction when a blue BMW roared past me. I instantly gave chase with blue lights, giving the details of my pursuit on the radio. Past the industrial estate I was doing my best to keep contact and get sight of the number plate. I was struggling to keep up and knew the car would be long gone once it was on open roads, and the M11 was nearby. I called for assistance from our faster Traffic cars and requested further help from our neighbours in Essex. I was losing the car but still revving the nuts off my little Astra, trying my very best to keep up. The BMW entered the slip road for the M11, and I was several hundred yards behind. Then the car suddenly braked, screeching to a halt as I sped closer. The driver got out, waving his arms as I closed in on my target, I jumped out to be met by this furious man who shoved an ID in my face and screamed ‘I’m fucking Special Branch you fucking prick, check the fucking number plate.’ Then he ran back into his BMW and drove off. Yes, I got my ass handed to me by my sergeant for that. But hey, the thought was there. Whoops …

I had an appetite for policing, and soon I wanted to leave the rural scene, so I transferred to the very busy K Division, covering Cheshunt and Waltham Cross. There were no green fields and farms; it was a totally different style of policing. And it was busy!

I’ve had numerous memorable police chases, but one sticks out purely because I’m a car man. It was a normal afternoon on a normal weekday and I was patrolling alone in a slightly newer W-reg Astra. I passed a silver Porsche 911 convertible with the roof down, and instantly recognised the driver – a well-known local toerag. And I knew that there was no way he could afford a 911! I followed for a few hundred yards, requesting a PNC check on the plate and the status of the known villain’s driving situation. The car came back normal, owned and registered locally to an address in Little Berkhamsted. Weird how I remember that little detail? Still, it didn’t add up, and whatever the information, I was stopping that car. The moment I put my blue lights on he was off. It was now a Porsche 911 versus a 1.4 Astra – mmmm … Had he stuck to the A roads he would have left me for dust, but he didn’t. He entered a housing estate, weaving in and out of the roads and losing his back end on almost every corner. His lack of car control meant I kept up easily, and we raced around the estate until we reached a dead end, where he jumped out of the car and ran off into a park. I gave chase, and as I was a pretty quick runner back then. He was arrested within a few minutes and we walked back to the car. Of course, he had a perfectly reasonable story: the car was his friend’s, etc, etc. But I know cars pretty well, and having a simple look around it I found the poorly modified chassis number concealing that it was, in fact, a stolen car and he had just copied the number plate from another local 911 he saw to avoid suspicion. However, he couldn’t resist the temptation of some roof-down cruising. Sure enough, I had caught red-handed one of our most notorious local offenders in a stolen Porsche 911, which was then reunited with its owner, and I’d had a pretty cool police chase, too. That was a good day.

Driving police cars is dangerous and I have had numerous scrapes along the way. I once parked my police car on the A10 to direct the flow of traffic down the very tight Theobalds Lane and to block a crash scene. While waving a lorry on, the back of his rig caught the front bumper of my car, dragging it for about 20 yards while I was frantically waving my arms to get him to stop. Then ‘PING’, he pulled my front bumper clean off. It was a light and funny moment, looking back. However, that same road was also the scene of my first serious POLAC (police accident). I was a passenger in a marked police car with a member of my team driving. We were on ‘blues and twos’, pulling onto the A10 when – BANG – we were smashed into by a silver BMW. We spun off and hit a fence and he went into the oncoming traffic. It was a heavy hit. My partner Sue was stunned. I turned the sirens off and ran to the car that had hit us, trying to get the man out of the car. He wouldn’t leave the vehicle, even as I was pulling at him harder and harder to get him out. It was only when a member of the public came over and said ‘he has his seatbelt on’ that I realised what an idiot I was. Whoops. The next moment I was in an ambulance on the way to hospital. Shock is a weird thing.

K Division was crazy, a busy place to police, with varying crime and a melting pot of cultures. It was on the fringes of north London, making it a Metropolitan police area until Herts took over the patch. I was on the transition team for that takeover, sharing the patrols with the Met until they slowly thinned out to being all Herts officers. A memorable period for policing at this time was that of the petrol strikes, which crippled the nation. It was chaos! Only priority motorists were allowed access to fuel (which meant that, as a member of the emergency services, I was okay). Seeing the public descend into chaos and the queues and distress at the pumps made it clear how important the motor car is to the daily lives of so many people.

My time in K Division was great; I saw and did some crazy things in that period; there was a lot of crime and violence, but I knew that I wanted to lean towards more action, so I applied for probably the most specialist role in the police: the TFU, the Tactical Firearms Unit. That decision changed my life forever.

It’s important to remain focused on the fact that this is a book about police cars, and although I have numerous stories from my time in the police, as I’ve already said, many are not fit for this publication. There was, however, for me, a changing relationship with the police car at the moment when I was handed a gun. I learned very quickly that the police car was now both an effective weapon and a place of safety. Before being armed, I had never really considered the ballistic properties of a car, such as, when the shots start coming which areas are effectively bulletproof? It’s not like the movies; the door of a Volvo T5 won’t stop a bullet! The engine bay, however, would, and that Volvo bonnet became a regular vantage point to lean over while armed with either an MP5 or a G36 weapon. It was the Volvo that became my favourite police car. It was amazing! We used Volvos and Mercedes as ARV (Armed Response Vehicles); both were estate versions, providing more space to carry the extra equipment. The only real performance upgrades were ceramic brake discs and fancy callipers, otherwise it was pretty much a standard car. Between the front seats there was a gun safe that carried larger weapons. First the MP5, a small, compact assault weapon that was really accurate, then some months later we changed to a G36, which was more of a rifle. The safe was locked and the weapons unloaded. We would have to ‘self-arm’ when en route to incidents, and of course for immediate issues we would use our side arm (in my case a Sig Sauer 9mm self-loading pistol) that we carried each day in a holster. Open the boot of the car and there was a huge locked pull-out tray that contained loads more goodies: baton guns, flash bangs (Stun grenades), shotguns with varying types of cartridges, CS rounds and a bunch of other cool non-firearm stuff. Under this tray we carried additional equipment like first-aid kits, a defibrillator, a stinger (a bed of nails for puncturing car tyres) and so on. This ARV was basically a mobile armoury, and therefore it was heavy! The Volvo seemed the perfect choice, and I could not believe that car’s performance ability; it was rapid, but ever so reliable. I can’t remember a single moment when that car let us down – and we put her through her paces, we did not hold back! As we patrolled with two ARVs at a time there was always a race to grab the Volvo ahead of the Mercedes, as all the TFU team knew the Volvo had the edge. Strangely, of the standard road-going cars the Mercedes would be superior, but I guess the Volvo just carried the extra weight better. It was a reliable Swede. The TFU had a host of other unmarked cars, and I spent many hours concealed in the back of a green unmarked Mercedes Sprinter van, in particular. It’s amazing how dark the humour is when there are half a dozen armed coppers trapped in the back of a van. Now if that van could talk …!

The TFU also had an armoured Land Rover 90. I was told it was an ex RUC (Royal Ulster Constabulary) vehicle from Northern Ireland, and it certainly looked the part. Constructed with fully riveted flat steel panels and thick bulletproof glass, it weighed tons. It was also the slowest car I think I have ever driven, taking minutes to get up to 40mph, and it barely went round a corner. I drove it several times but only ever used it operationally once. It was in December one year when we received a report of a man at the Christmas-tree-sales place brandishing a gun. We entered the farm in the Land Rover using the loud-hailer to give the chap instructions. Turned out the gun was a toy.

In 2005 I left the police to follow my true passion of building and restoring cars. My television career kicked off with the Channel 4 car show For the Love of Cars, which ironically was hosted by a TV police legend Philip Glenister, who is well known for playing Detective Inspector Gene Hunt in Ashes to Ashes and Life on Mars. In For the Love of Cars I restored an ex-Scottish Police Rover SD1 known as ‘The Beast’, which went on to sell at auction for a new auction world record for a SD1. Working on that car brought back many police memories, and in the show we retraced the infamous ‘Liver Run’ in the car as a tribute to the original SD1’s dash through London with an organ that was urgently required for a patient mid-surgery.

This book was written in order to share not only my passion for the Great British police car but as a nod back to those proud and amazing years I spent serving the British public.

This is a Hertfordshire Vauxhall Astra Mk3 just like the one I started my policing career driving, only mine didn’t have a bonnet box. It wasn’t fast, but it was a faithful servant and I loved it at the time.

CHAPTER ONE (#ulink_6356ba71-9fd1-595f-aa2d-b70f19307444)

CREATING THE BLUE LINE: THE BIRTH OF THE BRITISH POLICE FORCE (#ulink_6356ba71-9fd1-595f-aa2d-b70f19307444)

In modern times we take the police for granted, don’t we? Politicians wrangle about bobbies on the beat, budgets or efficiency savings (which even in my time in the force was a euphemism for cuts!), and if a serious crime happens we’re used to seeing the police going about their business on the news. We all know we should pull over for a police car rushing to an emergency on ‘blues and twos’, and we take this sight for granted, because it is now expected that in a civilised democracy we will have a police service that will enforce the rule of law on the criminal few for the good of the law-abiding many.

However, it wasn’t always like this, and although this book will concentrate on the service cars, some background to the police is both instructive and interesting, especially when you learn how the police first dealt with the early motorists on the roads! The story starts long before the famed ‘Peelers’; although they are often seen as the origin of the British police, in fact local areas had, from the earliest days of society, utilised some form of law either by force or consent. The Roman conquest of Britain, which began in 43 AD and lasted until around 420 AD, brought with it a monetary system and a form of organised policing. The Anglo-Saxon kingdoms also had a police service of sorts, based on the regional system known as a hundred or (and I love this word) ‘wapentake’. The first Lord High Constable of England was established during the reign of King Stephen, between 1135 and 1154, and those who filled this position became the king’s representatives in all matters dealing with military affairs of the realm.

The Statute of Winchester in 1285, which summed up and made permanent the basic obligations of government for the preservation of peace and the procedures by which to do this, really marks the beginning of the concept of nationwide policing in the UK. Two constables were appointed in every hundred, with the responsibility for suppressing riots, preventing violent crimes and apprehending offenders. They had the power to appoint ‘Watches’, often of up to a dozen men, or arm a militia to enable them to do this. The Statute Victatis London was passed in the same year to separately deal with the policing of the City of London, and, amazingly, today the City of London Police, dealing only with the ‘square mile’, remain a separate entity to the larger Metropolitan Police. The current City Police Headquarters is built on part of the site of a Roman fortress that probably housed some of the London’s first ‘police’, and these ‘square mile’ officers can be distinguished out on the streets by the red in their uniform and by their red cars.

By the end of the thirteenth century the title ‘Constable’ had acquired two distinct characteristics: to be the executive agent of the parish and a Crown-recognised officer charged with keeping the king’s peace. This system reached its height under the Tudors, then the oath of the Office of Constable was formerly published in 1630, although it had been enacted for many years previous to that. Sadly, this arrangement disintegrated somewhat during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and nationally nothing replaced it fully until the Victorian era. However, all police officers still hold the Office of Constable, and when I was appointed as a Constable, in 1999, I too had to take a similar oath in a rather splendid passing-out parade.

London led the way in the development of policing because by 1700 one in ten of England’s population lived in the metropolis, and the population of the area would rise to over a million before the century was out. Sir Thomas de Veil, a silk merchant-turned-soldier-turned-political lobbyist, became a Justice of the Peace in 1729 and worked out of his office in Scotland Yard. He conducted criminal hearings, moving to Bow Street in 1740, and as the first magistrate to set up court there effectively created the Bow Street Magistrates’ Court. His ideas for curtailing crime were ambitious, and, following his death in 1746, the novelist Henry Fielding was appointed Principal Justice for the City of Westminster in 1748 together with his brother, Sir John Fielding. They appointed a group of ‘thief takers’ as they were initially called, who were paid a retainer to apprehend criminals on the orders of the magistrates. These men soon became known as the Bow Street Runners; by 1791 they had adopted a uniform, and by 1830 over 300 officers were based in Bow Street, some using horses in the battle against crime.

A similar process happened in Scotland, where the first body in Britain to actually be called a police force was set up by Glasgow magistrates in 1779. It was led by Inspector James Buchanan and consisted of eight officers, but by 1781 it had failed, through lack of finance. However, the force was revived in 1788 and each of its members was kitted out withuniformswith numbered‘police’ badges on, in return for lodging £50 with magistrates to guarantee their good conduct. The force of eight provided 24-hour patrols(supplementing the police watchmen, who were on static points throughout the night) toprevent crime and detect offenders. Their list of duties, which would fit comfortably into the basic duties of policing today, included:

• Keeping record of all criminal information.

• Detecting crime and searching for stolen goods.

• Supervising public houses, especially those frequented by criminals.

• Apprehending vagabonds and disorderly persons.

• Suppressing riots and squabbles.

• Controlling carts and carriages.

Thus Glasgow had established the concept of preventative policing, and it’s hard not to wonder just how much knowledge of this Robert Peel had or how much inspiration he perhaps took from Glasgow’s pioneering force when he brought this idea into Parliament forty years later. On 30 June 1800, the Glasgow Police Act 1800 received Royal Assent, and John Stenhouse, a city merchant, was appointed Master of Police in September 1800. He immediately set about organising and recruiting a force, appointing three sergeants and six police officers and dividing them into sections of one sergeant and two police officers to each section – to some extent copying military practice while also pioneering a line of command that is not unfamiliar today.

However, in order to understand the history of policing in England we must also look at the most efficient freight vehicles of the eighteenth century – boats. The modern police service has its roots in a river security force that was set up by Patrick Colquhoun in 1798. He persuaded fellow merchants to pay into the scheme, which was designed to combat the epidemic of cargo thefts in the Pool of London (a stretch of the Thames), and which, in 1799 remember, amounted to over half a million pounds. The area was so congested it was said to be possible (most of the time) to walk across the Thames simply by stepping from ship to ship. The government absorbed this service in 1800 and renamed it the Thames River Police.

When reformist Robert Peel (whose Christian name is the reason why police are still commonly referred to as bobbies) became Home Secretary in 1822, his initial attempts to create a national police force failed. However, he succeeded in putting through the Metropolitan Police Act in 1829, creating a force with just over a thousand officers. Peel was determined to establish professional policing in the rest of England and Wales, and the Special Constables Act of 1831 allowed Justices of the Peace (JPs) to conscript men as special constables to deal with riots, and this was built on by the Municipal Corporations Act 1835, which established regular police forces under the control of new democratic boroughs, 178 in all. It was not a great success and was often ignored; however, the later County and Borough Police Act 1856 built on the idea, committed proper financing and decreed that a rural police force was to be created in all counties; it was one of these, the county force of Hertfordshire, that I joined.

At this point in history there was still a way to go to achieve the police force that we have today, but the beginnings of our modern policing system could be seen in the counties and in Glasgow. By the 1860s a nationwide force of separate bodies acting to one set of rules and connected by transport links (horse-drawn initially, but increasingly using the railway system, which was expanding rapidly by 1850) existed. The car would eventually be invented in 1885, but police forces all over the world simply weren’t ready to manage this new and politically divisive mode of transport. Britain was no exception.

The Office of Constable: the basis of UK policing

On appointment, each police officer makes a declaration to ‘faithfully discharge the duties of the Office of Constable’, and all officers in England and Wales hold the Office of Constable, regardless of rank. They derive their powers from this and are servants of the Crown, not employees. The oath of allegiance that officers swear to the Crown is important as it means they are independent and cannot legally be instructed by anyone to arrest someone; they must make that decision themselves. The additional legal powers of arrest and control of the public that are given to them come from the sworn oath and warrant, which is as follows:

‘I do solemnly and sincerely declare and affirm that I will well and truly serve the Queen in the office of constable, with fairness, integrity, diligence and impartiality, upholding fundamental human rights and according equal respect to all people; and that I will, to thebest of my power, cause the peace to be kept and preserved and prevent all offences against people and property; and that while I continue to hold the said office I will to the best of my skill and knowledge discharge all the duties there of faithfully according to law.’

This is the oath that I myself took.

CHAPTER TWO (#ulink_3d85e6f4-73d8-5b60-9ec5-39a988f6d5a0)

THESE DEVILISH MACHINES SCARE THE HORSES, YOU KNOW (#ulink_3d85e6f4-73d8-5b60-9ec5-39a988f6d5a0)

On Monday 20 January 1896, Mr Walter Arnold, who worked for his family’s agricultural machine-engineering concern in East Peckham, Kent, was driving along the Maidstone Road through the neighbouring village of Paddock Wood at an estimated 8mph, 4mph or so below the maximum speed of the ‘Arnold Motor Carriage Sociable’ (a Benz copy produced under licence) that he was driving. Local constable J.C. Heard, of the Kent County Constabulary, saw this outrageous behaviour from the front garden of his cottage and set off in hot pursuit on a single-speed bicycle. In that one moment the relationship between the UK police and the motorist was, partially at least, set.

The speed limit in the area was a mere 2mph, so Arnold was thus exceeding it fourfold – although how Constable Heard measured this accurately enough to definitely state this is, of course, unknown. Arnold was chased (on the bicycle) and eventually caught by the presumably quite fit local bobbie after a five-mile pursuit! It is recorded, with some understatement I suspect, that Constable Heard had to pedal at his hardest for quite some time (at 8mph that’s just under 40 minutes’ pedalling time) before catching the unfortunate Mr Arnold. Arnold was charged with four offences; three pertaining to the Locomotives Act and one offence of speeding. The case went to trial, and although Arnold’s barrister, a Mr Cripps, argued that the law shouldn’t apply to the new lightweight ‘autocars’ and that Arnold had a carriage licence (a system designed for horse-drawn carriages), Arnold was found guilty on all counts and ordered to pay a total fine of £4 6 shillings, of which only a 1 shilling fine and 9 shilling costs was for the speeding offence. When you take into account that his car sold for £130, this fine seems quite paltry, but remember that cars back then were a luxury, and the average weekly wage was less than £1 for a 56-hour working week.

Arnold was not only the first motorist fined for speeding in the UK, but it is believed that he was the first person in the world to claim this dubious honour. The car as a concept was young, and, much like laws surrounding the internet in the early twenty-first century, the legislators took some time to draft new laws that applied to these vehicles. Some eminent politicians of the time even felt it wasn’t worth the bother, as they deemed that these horseless carriages were bound to be just a phase, the attitude being that they would be short-lived as they frightened the horses for goodness sake!

Arnold probably wasn’t too unhappy with the publicity that his case generated, because he was in fact one of the country’s first car manufacturers and dealers. His career began by selling new, imported Benz cars from Germany, then between 1896 and 1899 he manufactured a licensed copy of the Benz called the Arnold Motor Carriage. At this point demand for these newfangled machines was high and Arnold is quoted as saying in a newspaper report towards the end of 1896 that, ‘if we had twenty in stock they could be disposed of in a week’. No documents exist hinting in any way that he deliberately drove through Kent intending to get caught, but you have to wonder, don’t you? If he did do it deliberately he was a marketing genius and well ahead of his time. He apparently sped past the Constable’s house, and as a local himself he would surely have known where the local bobbie lived. If he did get caught deliberately, he exhibited an understanding of the media and the gentle art of car marketing at least fifty years ahead of his time – secretly, I kind of hope he knew exactly what he was doing, and thus Arnold placed down a permanent marker for all car sales people to follow. Take a bow, my man.

Arnold kept a scrapbook of press cuttings about his cars and their exploits that still belongs to the owner of the very car that he was driving when he was apprehended, so it’s a real possibility that this was a deliberate act. Having said that, that scrapbook also shows that he and other family members committed similar offences at least twice more, so perhaps they just considered this the price paid for the freedom to ‘motor’ at will. This was certainly the prevailing wisdom among motoring pioneers of the time, and the pages of the first editions of The Autocar (which began circulation in 1895) are full of motorists testing the judicial system in one way or another, using their new machines. Newspapers also picked up on this, carrying drawings of ‘future townscapes’ showing horseless carriages and stating that science had made this possible but the law was preventing it happening.

Arnold Motor Carriage Sociable, Chassis Number 1, MT20

Engine: 1200cc single cylinder with open crank case and separate water jacket.

Power: 1.5bhp@650rpm.

Range: 60–70 miles on one tank of ‘Benzoline’ oil, as early petrol was called. This cost 2s 6d per gallon in 1896.

Ignition: Electric, with enough current stored in two 2-volt accumulators to run the car for approximately 600 miles. The concept of a charging system was not initially included.

Max speed: Approximately 12mph, able to average 10mph comfortably.

Transmission: Fiat belt with movable bearings to take up slack.

Production: 12 examples made between 1896 and 1898, plus a small number of related vans.

After being development-tested in Ireland in order to avoid further persecutions by the local constabulary, Arnold Number 1 was sold to engineer H. J. Dowsing and became the first car ever fitted with an electric starter motor, called a Dynomotor. Amazingly, this was originally designed as an electric ‘help motor’ to give the car greater power when needed for hills. Yes, the concept of the petrol-electric hybrid so trumpeted by the Toyota Prius in recent years was in fact invented in 1897 by Dowsing, although its development was not pursued at that time.

Remarkably, this original car has still only had five owners from new: the Arnold Company, Dowsing, a Captain Edward de W. S. Colver, RN (Rtd), who partially restored the car after buying it from Dowsing in 1931 and whose family sold the car to the Arnold family at auction in 1970. In the mid-1990s it was sold to Tim Scott, who retains ownership today and uses it regularly on the London to Brighton run and other events.

With pollution from cars a regular topic in the TV news, and even a consideration in political campaigning, it seems counter-intuitive to say that the car was bound to catch on because it was so much cleaner than the alternative, but that’s exactly what happened. The alternative, which had existed for many years, consisted of wading through a horse-manure-based, and extremely pungent, soup. Period dramas on TV skim over this, but it was definitely a factor in the growth of motor-car use, and compared to getting horse manure all over your skirt or trousers, car exhausts must have seemed amazingly clean and green!

However, UK legislation initially made the technical and physical progress of mechanised transportation difficult, whether powered by gasoline (the word petrol did not enter use until it was patented by Messrs Carless, Capel and Leonard of Hackney Wick in 1896), steam, electricity or even coal dust. In 1865 the Locomotive Act (Red Flag Act) had introduced a speed limit of 2mph in towns and villages and 4mph elsewhere. It stipulated that self-propelled vehicles should be accompanied by a crew of three: the driver, a stoker, and a man with a red flag walking 60 yards ahead of each vehicle. The man with a red flag or lantern (when dark) enforced a walking pace, and warned horse riders and horse-drawn traffic of the approach of a self-propelled machine. After centuries of animal training and use, both the politicians and general population trusted a well-trained horse far more than these newfangled steam-driven road locomotives!

Parliament thus effectively framed legislation that trusted the established system, horse-drawn wagons, and prevented the scaring of horses, which were then the backbone of commerce. The country’s legislators put more trust in the behaviour of horses than in the safety of human-designed and built machinery … This seems amusing to modern sensibilities, but perhaps they were right to create these laws, for these early machines weighed an enormous amount, had little in the way of brakes and made all sorts of scary clanking and hissing noises which could spook even the best-trained horse. However, the development of smaller petrol and electric carriages made this law outdated by 1890, and it was this law that was most often tested by pioneer motorists who claimed they could use an Autocar on a standard (horse-drawn) carriage licence rather than the much more restrictive Locomotive Licence. Arnold also claimed this and was convicted of this offence as well as speeding. This Arnold chap is my type of guy. I like to think we would have been friends.

Although the use of motor cars was growing in the 1890s, the horse was king and would effectively remain so (at least in volume terms) until after World War I, which was, like so many conflicts, the catalyst that drove change technically, economically and socially.

The world’s first petrol-powered proper road trip …

Britain’s legislation did not help our nascent car industry to grow, but it also didn’t stop the rest of the world coming to a collective consensus about the fuel of the future. Karl Benz produced the first gasoline-engined car in 1885, and in August 1888, without his knowledge, his wife Bertha made the first ever car journey of significant length using an improved version of his design, to prove its worth to the less-than-confident Benz as well as the world.

Bertha and their two sons, Eugen (15) and Richard (14), travelled from Mannheim to Pforzheim, her place of birth, and although Bertha apparently used a hatpin to unblock a fuel line, she demonstrated the practicality of the gasoline motor vehicle to the entire world – and perhaps should have to put to bed any criticism of women drivers at the same time … Without her daring – and that of her sons – this book might have been about steam-powered police cars!

Left: Portrait of Bertha Benz. Right: Bertha Benz and her sons buy petrol during their long-distance journey in 1888.

Some UK pioneer motorists deliberately challenged the Red Flag Act, believing their new lightweight steam-, electric-or gasoline-powered vehicles should be classed as ‘horseless carriages’ and therefore be exempt from the need for a preceding pedestrian and could be operated using a carriage licence. A case was brought against motoring pioneer John Henry Knight in 1895; he lost and was convicted of using a locomotive without a licence and fined 2 shillings and 6d. However, he had neither a carriage nor a locomotive licence, so the law had two ways to turn, which meant that he was guilty of using a locomotive without a licence whichever decision was made!

Early editions of The Autocar (a weekly magazine, the first edition of which was published on 2 November 1895 and whose cover proclaimed: ‘A journal published in the interest of the mechanically propelled road carriage’) were full of lengthy reports of court proceedings being taken against motoring pioneers for a variety of reasons. Legislators caught up with the reality of mechanical development before the law created any real precedents, and the Red Flag Act was repealed on Saturday 14 November 1896, when the speed limit was raised to 14mph; a fact that was celebrated on the day by an Emancipation Day Run (in which our speeding friend Arnold took part in the very same car in which he had been done for speeding) and which today’s London to Brighton Veteran Car Run (often incorrectly called a race) celebrates.

Sadly, the first recorded automotive road fatality in the UK was also in 1896, when Bridget Driscoll, 44, was killed in the grounds of the Crystal Palace on 17 August. She was walking with her 16-year-old daughter, May, and a friend when she was run over by a Roger-Benz car being driven by Arthur Edsall. At the inquest, Florence Ashmore, a domestic servant, gave evidence that the car went at a ‘tremendous pace’, like a fire engine – ‘as fast as a good horse could gallop’.

The driver, working for the Anglo-French Motor Co., who were part of an automotive exhibition taking place at the Crystal Palace, said that he was doing 4mph when he killed Mrs Driscoll and that he had rung his bell and shouted ‘Stand Back!’ as he approached. However, it was suggested that Mrs Driscoll seemed bewildered in front of the car. She may not have interacted this closely with a motor vehicle before. Who knows? There were then fewer than twenty in the whole of the UK and the public were certainly not educated in how to cross roads safely. Edsall had been driving for only three weeks at the time, and as no licence was required, the fact that he apparently had not been told which side of the road he needed to travel on was overlooked … The case went to court, but with conflicting evidence about the speed and manner of Mr Edsall’s driving, the jury returned an accidental death verdict. Interestingly, there was no outrage in the newspapers at the time, just a sense that it was an unfortunate accident. It would be some years before the press became powerful enough to express outrage in the way that we take for granted today. It’s also worth noting that, although people had been killed by horses or carriages for many years, high-profile autocar accidents did start to bring up some public discussion of these dangerous new machines, which were loved by those who had them and often feared by those unfamiliar with them. For that reason accidents were reported perhaps a trifle more vociferously than they would have been if someone had simply fallen off a horse and broken their neck. It was, after all, the start of the unknown.

Perhaps ironically, the first death in an autocar accident was during an incident with an International Co. electric vehicle on 12 February 1898, when Mr Henry Lindfield of Brighton tried to stop his vehicle in order that his passenger, his 19-year-old son Bernard, could retrieve his bag, which had fallen off as they descended the hill off Purley Corner, in Croydon. When the brakes were applied the vehicle began to weave, before eventually hitting a post and then a tree, sandwiching poor Henry between the carriage and the tree. Son Bernard was thrown over his father and survived with relatively minor injuries, but, sadly, his father died in hospital the following day. Just over a year later the first fatal accident involving the driver of a petrol motor vehicle was recorded; 31-year-old engineer Edwin Sewell’s 6HP Daimler Wagonette crashed into a wall after a rear wheel collapsed following a rim breakage when the brakes were applied too harshly while descending a steep hill at speed. He died almost instantaneously. At the time he was demonstrating the vehicle to three passengers who were assessing it for possible purchase by their company, the Army and Navy Stores, then a well-known department store. The front-seat passenger, 63-year-old Major James Stanley Richer, was thrown clear of the vehicle with Sewell and suffered such serious injuries that he died three days later in hospital. The other two passengers were injured but survived.

The roadside plaque (unveiled on 25 February 1969) records the site of Britain’s first fatal road accident, on 25 February 1899.

As a result, the UK police started to take cars seriously, and the weight of public pressure – and in some cases outrage – meant that they had to. As far as research can prove, it was the Met that led the way, acquiring a Léon Bollée Voiturette in 1896, or possibly early 1897. The arrival of the Bollée, as it was usually called, is important because it represented the moment when the British police moved from enforcing legislation on motorists to becoming motorists themselves. Quite what those early Met police pioneer drivers would think of today’s high-speed chases on the M25 we shall never know, but to modern eyes the pioneering car does seem almost laughably poor in both performance and engineering terms. At that time the template for what makes an acceptable usable car, as opposed to an experiment down a dead-end avenue of design, was yet to be set, and the Mercedes-badged Daimler that made every other autocar old-fashioned overnight, and so set the car on its course to dominate transportation in developed nations by the early 1920s, would not appear until 1901.

1896 Léon Bollée Voiturette

The birth of the Léon-Bollée Voiturette light autocar goes back to the 1870s, when Amédée Bollée, son of a foundry owner specialising in bells, started making steam vehicles in Le Mans, France, way before the town became part of motor-racing folklore after Renault’s victory in the 1906 French Grand Prix there.

Although Amédée Bollée was a steam enthusiast, he could see the potential in gasoline-engined cars and helped both his sons, Amédée Junior and Léon, design and build them. Léon’s design was immediately successful, although I suspect anyone who ever crashed into anything while sitting on that front-mounted chair may have disagreed! The vehicle was considered fast in its day; even in their early days the police bought the fastest car they could afford, kicking off the arms race between the good and the bad guys earlier than most of us had realised!

Bollée’s design for a very short-wheelbased, 3-seater motor-tricycle, the Voiturette, weighed only 264lbs, used a tubular frame and featured a single back wheel, making it far more stable than having the single wheel at the front. The engine was an air-cooled, horizontal, single-cylinder unit of 650cc that was hung beside the back wheel on the near-side and used a large, heavy flywheel. It featured suction-opened inlet valves and mechanical exhaust valves with plain bronze bearings, hand-lubricated by grease for the main bearings and a splash-lubricated big-end. A tubular con-rod kept the weight down, while hot-tube ignition and a single-jet carburettor were so close to the float chamber that fires were common. The 3-speed transmission was by three virtually unlubricated gears on the end of the crank, which could be meshed with the three layshaft gears. The drive was by flat belt, a mechanism that was commonly used then to drive lathes and other machines in workshops. There was no actual clutch; the mechanical movement of the back wheel tightened or loosened the driving belt so that drive was achieved or neutral was obtained. Full-forward movement of the back wheel applied the belt rim to a stationary brake block. In some ways it was an elegantly simple solution; one fore and aft movement of the rear wheel achieved one of three outcomes. However, the Bollée was apparently quite tricky to actually drive, partly because it featured a small steering wheel on the driver’s right with a handle familiar to traction-engine drivers, which actuated an early rack-and-pinion steering system. Meanwhile, the left hand had to ease the gear stick gingerly back and forth to engage the drive or free it. Turning the spade grip at the top of this lever engaged a gear, and, in order to stop, the lever had to be hastily pulled backwards. I can’t imagine many of my former police colleagues (or myself, for that matter) taking it easily, but perhaps sheer fear would have engendered that on this device …

The Voiturette was powerful for its size and weight, and its low build made it stable, but the short wheelbase made spinning on slippery cobbled roads quite common, and comfort was not a priority because they had no suspension, relying on pneumatic tyres and a C-sprung seat to provide a modicum of relief. However, driven by what we must assume were men made of granite, they dominated their class in early motor races, famously occupying the top four places in the 1896 Paris-Mantes-Paris race, and winning their class in the 1897 Paris-Dieppe race with a time that was 0.6mph faster than the best four-wheeled car. Legendary English racing driver and Le Mans winner S.C.H. Sammy Davis bought an example in 1929 to use in the London to Brighton Veteran Car Run (a Léon Bollée Voiturette was apparently the first car across the line on the original Emancipation Run in 1896) and was pleased to achieve a maximum speed of 19mph when testing it at Brooklands! This would have been impressive in 1896; the first Land Speed Record was recorded in 1898 at 39mph. Amazing to think now how far we have come.

After being developed in the family’s Le Mans workshop, the car was produced in Paris, at 163 Avenue Victor Hugo, and at Le Harve by Diligent et Cie. It’s believed that around 750 units were made; Michelin ordered 200 and the Hon Charles Rolls (we all know who he was) was a customer in 1897. By 1899 new four-wheeled Bollées were being produced, some with much larger 4.6-litre engines, but the marque was bought by UK maker Morris in 1924, who produced the Morris-Léon Bollée until 1931. It finally faded away for good in 1933.

What’s in a name?

Léon Bollée’s tricycle may have been short-lived, but the word he appears to have invented to name it, Voiturette, lived on and became the generally accepted term for a small lightweight car. It comes from the French word for automobile, voiture, and became so ubiquitous that it was used to name a specific Voiturette racing class for lightweight cars with engines of 1.5 litres or smaller. The supercharged Alfa Romeo 158/159 Alfetta that so dominated F1 on its inception was, in fact, originally designed as a Voiturette class racer.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/ant-anstead/cops-and-robbers-the-story-of-the-british-police-car/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Ant Anstead

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Техническая литература

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: TV presenter and all-round car nut Ant Anstead takes the reader on a journey that mirrors the development of the motor car itself from a stuttering 20mph annoyance that scared everyone’s horses to 150mph pursuits with aerial support and sophisticated electronic tracking.The British Police Force’s relationship with the car started by chasing after pioneer speeding motorists on bicycles. As speed restrictions eased in the early twentieth century and car ownership increased, the police embraced the car. Criminals were stealing cars to sell on or to use as getaway vehicles and the police needed to stay ahead, or at least only one step behind. The arms race for speed, which culminated in the police acquiring high-speed pursuit vehicles such as Subaru Impreza Turbos, had begun.Since then the car has become essential to everyday life. Deep down everyone loves a police car. Countless enthusiasts collect models in different liveries and legendary police cars become part of the nation’s shared consciousness.Ant Anstead spent the first six years of his working life as a cop. He was part of the armed response team, one of the force’s most elite units. In this fascinating new history of the British police car, Ant looks at the classic cars, from the Met’s Wolseleys to the Senator, the motorway patrol car officers loved most, via unusual and unexpected police vehicles such as the Arial Atom. It’s a must-read for car enthusiasts, social historians and anyone who loves a good car chase, Cops and Robbers is a rip-roaring celebration of the police car and the men and women who drive them.