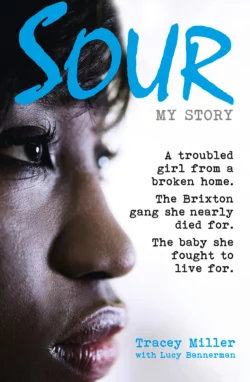

Sour: My Story: A troubled girl from a broken home. The Brixton gang she nearly died for. The baby she fought to live for.

Tracey Miller

Lucy Bannerman

They call me Sour. The opposite of sweet. Shanking, stabbing, steaming, robbing, I did it all, rolling with the Man Dem. I did it because I was bad. I did it because I had heart. And the reason I reckon I got away with it for so long? Because I was a girl.SOUR is the true story of a former Brixton gang girl, drug dealer and full-time criminal. A member of the Younger 28s, a notorious gang that terrorised the postcodes around Brixton in the 90s, Sour escapes a troubled family life to immerse herself in the street life of likking and linking. She never leaves her house without a knife. At the age of fifteen, she stabs an innocent man in the street, earning her unrivalled respect and ‘Top-Dog’ status amongst her crew. She believes she is invincible.But the consequences of her actions are soon to catch up with her. Waking for the second time in two weeks in a hospital bed, to the news that she is pregnant, she realises it’s time to turn her life around. Motherhood will be a rude awakening, but it may also be her saving grace.Told with raw emotions and ferocious honesty, this is the real, on-the-record, story of one woman’s descent down the rabbit hole of gangland, and her efforts, as a daughter, mother and girlfriend, to claw herself out.

(#uef9f014c-c9dd-51ca-9f69-4ae5148c68e5)

Copyright (#uef9f014c-c9dd-51ca-9f69-4ae5148c68e5)

Certain details in this book, including names, places and dates, have been changed to protect those concerned. Some events have been dramatised

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

77–85 Fulham Palace Road,

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperElement 2014

FIRST EDITION

© Tracey Miller and Lucy Bannerman 2014

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2014

Cover photograph © Kazunori Nagashima/Getty Images (posed by model)

Tracey Miller and Lucy Bannerman assert the moral

right to be identified as the authors of this work

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/green)

Source ISBN: 9780007565047

Ebook Edition © August 2014 ISBN: 9780007565054

Version 2014-07-29

Contents

Cover (#uf609d773-2ace-5934-b45f-2d29081e9c00)

Title Page (#ubb246329-70c9-55c1-8078-4b60553c7d04)

Copyright (#ulink_622a4f15-f343-5157-8f0d-ee175dbf0f0f)

Acknowledgements (#ulink_79f7ded1-baf3-5ad9-9b61-44e915d03103)

Introduction (#ulink_62ba632f-cbae-53a8-9e44-3947ffef21da)

Mum and Dad (#ulink_aa287a0d-8c5e-5e3e-ba78-956f7de7196b)

The Estate (#ulink_ad8816ff-34da-5001-a4b7-ad10f7c59e86)

Gangland (#ulink_77974a9d-5658-5277-bd82-50e594462572)

Islam (#ulink_cc761468-3781-5a4e-915a-5e9bba701b4d)

I’m Gonna Be a Name (#ulink_b457546b-7c16-52bc-a96f-09f4e526f99d)

Dick Shits (#ulink_c087a654-5005-5e91-8b51-4bf7d2eda2e1)

Steaming (#ulink_0ba064d4-d0d5-513f-8a9b-75694252d772)

Real Gangs (#ulink_ffca5548-7fe6-568f-b1ab-289896c5eb75)

Meeting the Youngers (#ulink_6913f452-a096-59a6-990a-46f0282b2782)

Welcome to the Younger 28s (#ulink_da819c10-784f-5727-96ed-0830a613c1c9)

The Secret (#ulink_ede4b2f9-5ca5-50c1-b1fc-4c98f16e8584)

Entertainment (#ulink_8ef9a2bc-268b-5856-9a6f-83b8f67ffc34)

High Life (#ulink_51da2bf1-d560-5d6f-ac56-840ffa172d5b)

Kitchen Drawer (#ulink_60eecd23-6bcd-52f4-83af-5fd13414e8df)

Mysteries (#ulink_97d767f1-44ae-5cad-88ae-53800868ef0f)

Right Girl, Wrong Crime (#ulink_f3883b32-6ed1-59b3-95e6-325f0f3298e7)

Getting in Deeper (#ulink_89930d80-6e68-545c-8d87-5bca9726d75b)

Betrayal (#ulink_b592b260-75d8-51b6-8b20-b12715ad21a2)

The Art of Stabbing (#ulink_4176f523-c3ff-51e3-992c-352f27e0ea50)

Playing Hardball (#ulink_70ff9a71-8e33-5d63-976a-193c698b9935)

Yout Club (#ulink_92b87f56-6df5-5cec-97b9-187d062605c5)

In For a Shock (#ulink_a606198f-5fa3-5c38-9e08-3f00bb64c9b3)

Holloway (#ulink_0f5f5391-3490-5b06-ad27-6b07e472e4a7)

Safe Haven (#ulink_4816ec89-15ed-560d-b924-c0657f91d849)

Change of Occupation (#ulink_abc36a4e-21ed-567f-acd5-965e84613381)

Going Professional (#ulink_7de4d2c1-f60c-50b4-96c0-ee837613f5f0)

Losing It (#ulink_cab7b47c-dc17-55e8-b0d3-a6b9651b1952)

David (#ulink_a93ea840-1042-5313-be28-0a3e13b5897e)

Inshallah (#ulink_091281a1-8e37-5970-b557-0af128542a9f)

No Such Thing as Justice (#ulink_031532a4-1190-56ff-ae51-6e02bde3f049)

The Mosque (#ulink_820bcc17-6a2c-5494-adbf-17830b30bf76)

The Raid (#ulink_5e6b0b1f-00ca-5128-ab34-da75f29b9554)

Riots (#ulink_e803370b-fee8-5d49-91f6-b69bde4ef78e)

Point of No Return (#ulink_606deed8-144d-533c-86d0-93a1750eeffc)

Overdose (#ulink_19ceb80a-76d7-5769-b571-81388c702c41)

Shock (#ulink_e547421b-87ba-5af5-8faa-f476f9332739)

Epilogue (#ulink_db5b6c0c-187d-53b7-8511-17b7f99df153)

A Note From Montana (#ulink_6245833a-0985-5329-89c8-733fdcfddb60)

A Note From Brooke Kinsella (#ulink_197c59fe-c7cd-557d-8cc7-17aee41c38b7)

Exclusive sample chapter (#ua6d756c5-d3be-5d6b-bd4b-f912cb4a00df)

Moving Memoirs eNewsletter (#ue5dc334c-6ebd-547a-91af-974351538080)

About the Publisher (#u0d98dcd6-6b82-532b-ae1c-0b66ff1ed8dc)

Acknowledgements (#uef9f014c-c9dd-51ca-9f69-4ae5148c68e5)

A big thank-you to my editors Vicky Eribo and Carolyn Thorne; my literary agent Jessie Botterill; my wonderful co-author Lucy Bannerman and the rest of the team at HarperCollins.

A special thank-you to my mum, for giving me life – I Love You! My brother, my sisters, my nieces, my family, who have always been there for me. My two daughters who keep me focused – I love you both dearly. Not forgetting my close friends who have kept me strong in one way or another.

A final thank-you to Brooke Kinsella, Hellie Ogden, Temi Mwale, Elijah ‘Jaja’ Kerr and Saadiya Ahmed.

Introduction (#uef9f014c-c9dd-51ca-9f69-4ae5148c68e5)

They call me Sour. The opposite of sweet. Shanking, steaming, robbing – I did it all, rolling with the Man Dem.

I did it because I was bad. I did it because I had heart. And the reason I reckon I got away with it for so long? Because I was a girl.

Sour was my brand-name. How should I put this? I was quite influential round my endz. In my tiny, warped world, where rude boys were the good boys and exit routes non-existent, I was top dog. I want to give people outside the lifestyle some insight into lives like mine. I want parents to think about what their kids really get up to. For them, let this be an education, an eye-opener.

I want to lay myself bare to all the people who knew me when I was bad. I am not offering this as an excuse. I’m offering an explanation.

Above all, for all the youngers like me, the kids without a home who become kids without a conscience, the ones living the streetlife who know the thrill of likking the tills or steaming a shop, the young bucks who don’t need to be told how easily a blade slides out of punctured flesh, let this be a warning.

Youth workers could argue I had no chance. Politicians could blame my parents. Others might say the choices I made were mine and mine alone. Maybe they’re all right.

Me? I think badness is genetic. With a manic depressive for a mother and a convicted rapist for a father, I ain’t never gonna be Little Bo Peep.

So this is my story, the real story of how I fell down the rabbit hole of gangland. There are no real excuses. I did what I did and I live with what happened. I have a lot to be thankful for.

The hard part is not working out where it all went wrong. The hard part is making it right.

Mum and Dad (#uef9f014c-c9dd-51ca-9f69-4ae5148c68e5)

My mum’s first memory of her childhood in Jamaica begins with a broom. Mum was eight; her little sister, Rosie, must have been five. They lived in Kingston, in a one-bedroom shack with their nana.

“Yuh pickney have tings easy,” she always used to tell us. “When we did young we had to work fucking hard to keep the yard clean bwoy, wash fi we own clothes and dem ting dere, cook our own food and ting. None ah dis mordern shit, yuh ah gwarn wid.”

It was the day before Christmas. Mum was outside, scrubbing the yard. She had left Rosie dancing in the dust by the stove, a skinny girl grappling with a broom twice her size. Mum was down on her knees with a scrubbing brush, when she heard the screams.

She’d knocked over the pot of bubbling oil that had been cooking on the stove.

“Burned all the hair clean aff her head,” she’d say. “Her little dress stuck to her skin.”

Mum, still such a small child herself, rushed for scissors to cut the cotton from the blistering skin and tried to calm the hysterical girl, but it was too late. Boiling oil is too strong an adversary for five-year-old girls.

At the funeral, she arranged the pillow in her coffin to make sure she was comfortable.

“Me did do her hair real nice fi church, well, what was left ah it,” she said.

They buried her on Christmas Day.

Her own mother didn’t make it to the church that day. She had already long left Kingston, leaving behind her daughters with their grandmother, to chase the tailwinds of the Windrush Generation to the UK.

No one had heard from her mother, but there was a rumour she’d found a job in an office. Mum said she spent years in that old, broken-down yard, waiting for the day she would send for her to join her.

While she waited, her grandmother started taking on lodgers.

That’s her other memory – of the lodger. He worked in the garage during the day, and drank beer from his bed by night. He persuaded her to go away with him one afternoon after school, and took her to the cemetery.

“The bloodclart smelled of grease and chicken fat. Laid me on a tombstone and put his finger up me.”

Lord have mercy, things weren’t right in that house. I never met Mum’s grandmother, but maybe that’s for the best – I have a feeling me and her wouldn’t have got on.

She was too strict for a start. No loitering after school, no free time, no fun.

She would tell my poor mum, “When school done, if mi spit pon de floor, yuh better reach home before it dry.”

If not, a beating was waiting. I didn’t believe Mum when she told me about the grater.

“She put a grater in the yard, till it got hot, hot, hot in di sun.”

Then she’d make Mum kneel on it. Oh my days, what a wicked witch! I’d have put that grater where the sun don’t shine.

Weird thing is, my mum still sticks up for the woman who raised her.

“Cha man, her heart did inna di right place.”

And where exactly would that be?

Still, I’ll give her something. She taught my mum to cook all the hardcore soul food that me and my brother love. Chicken, rice and peas, all the meats – no one cooks it better than my mum.

Aged 12, Mum finally got the call. Her mother finally sent a plane ticket for London. She said in the letter she was doing well and life was good. Mum dreamed of a big house with servants. She dreamed of the high life, in a country where people drove shining cars, girls wore short skirts and their wallets overflowed with Queen’s head.

But Brixton in the early 1970s wasn’t quite the paradise she’d imagined. For starters, she stepped off the plane in a cheap, yellow dress and was welcomed by snow. It pretty much got worse from there.

“In Jamaica we went to church because we suffered so much,” she said. “When we came to London, nobody went to church no more.”

“Me did know seh dere was a God in Kingston, becah he used to answer my prayers. Nobody nah answer no prayers inna Brixton.”

Oh yeah, quite a character, my mum. On her good days, she likes watching EastEnders, Coronation Street and Al Jazeera.

Whenever there’s something on the news about “feral youths”, as all those suited-and-tied BBC broadcasters like to call ’em, she always shakes her head and mutters, “Yuh pickney haffi learn to rass.”

Or, in other words, people’s kids need to learn to behave.

She loves baking, and makes a mean Jamaican punch. Oh my days! Nestlé milk mixed with pineapple juice, nutmeg, vanilla, ice cubes. Mix in rum or brandy and you’ve got a wicked pineapple punch. And a good chance of getting Type 2 diabetes, just like her.

I know I shouldn’t laugh, because of her illness, but there were wild times too.

Like that time she insisted on driving me and my brother to school in her speedy little Ford Capri, instead of letting us take the bus.

“Hold on!” she screamed, leaning back and putting one arm across my brother in the front seat and one arm on the steering wheel, as she slammed down her foot on the accelerator.

“Me taking di kids to school!”

She whizzed down Coldharbour Lane that day like she was bloody Nigel Mansell, cutting up cars and swerving wildly down the street. I remember screaming as we jumped the red lights and brought a big-assed bus screeching to a halt. She crashed into a van and folded up the front of the car. Mum didn’t even notice.

She just turned the radio up full volume and started chanting whatever weird shit came into her head. Oh my days, it was like Mrs Doubtfire meets Grand Theft Auto.

Yusuf and I clung on to our seatbelts and just prayed to God to get there safely. I swear I’ve never been so happy to get to school.

“Me go pick yuh up later,” she shouted, depositing the pair of us, shaking, traumatised heaps at the no-parking zone by the gates. “Make sure yuh did deh when me reach at tree tirty!”

With that, we heard the wheels spin, the engine roar, then she was gone.

Lo and behold, 3.30pm came and went, but Mum and her Ford Capri were nowhere to be seen.

The policeman told us later they had to give high-speed chase through Brixton.

“Rassclat!” she said, when we told her what happened. “Me did what? Yuh sure? I just remember seh me ah drive tru traffic, me put dung me foot annah drive fast, one minute me ah get weh, next minute dem got me.”

We tried not to giggle.

“Den I had to fight a whole heap ah policeman, and dem fling me down inna dem bloodclart van and take me down the station, bastards. Den dem take me go ahahspital.”

That was my first day at a police station. We spent the whole day there. They fed us, showed us the horses, the police cars. I’m not gonna lie – it was like a fun day out.

It was less fun, I imagine, for that poor Ford Capri.

She was remorseful about some things. Like the time she dangled my sister off the balcony.

“Me can’t believe seh mi woulda do dat to yuh,” she told Althea, once she came back down to earth. “I’m so sorry, girl, please forgive me, yuh mum wasn’t well.”

Althea and her always had problems after that.

Then there were the afternoons she used to pick up her baseball bat and walk through the streets, speaking to herself. Or the time she stripped stark naked and walked calmly down the road at rush hour. Or the time – this is my favourite – when she brought an elderly Russian lady home, and held her hostage.

How many other kids come home from school to find a confused and frail old woman perched on the settee, saying they’ve been kidnapped by your mum?

“Mum, what you doing?” we screamed.

“Me ah ask de woman, where ye live? And she come with me. Me haffi look after her.”

I looked at the frail old woman, clutching an untouched plate of rice and peas in her trembling hands.

Mum came into the front room, brandishing more food.

“Yuh hungry? Eat dis cake, it’s nice. Drink some tea. If yuh want, gwarn go sleep and drink.”

The sweet old lady reached up for my hand.

“Please,” she whispered, “I want to go home.”

Yusuf helped her escape, while I kept Mum distracted. She was horrified when she found the front room empty.

“Which one ah yuh let her out? Where’s she gaarn? I’m looking after her!”

Oh yeah, every year it was something, and it always seemed to be round Christmas.

You know that song, “Love and only love will solve your problems” by Fred Locks?

That’s the one she liked to listen to during her episodes. That’s the one she’d listen to over and over again and all through the night. The bass would shake the house.

Whenever that came on, and the volume was turned up, we knew to brace ourselves.

As for my dad, well, he was a proper little bad boy.

Mum’s first two babydaddies had been and gone before she met the man I have the misfortune to call my dad.

I’ve only ever known my mum as a medicated woman but she must have been an attractive lady. She could get the boys.

Althea’s dad was young too. His family were having none of it, and he soon scarpered.

Melanie’s dad, he was rich. He had money, but he was married, so Mum was his sidepiece. Not that she knew that at the time. He left her heartbroken and went back to the wife.

But me and Yusuf’s dad? Woah, Mum really hit the jackpot there.

In Brixton they called his crowd the “Dirty Dozen”. They travelled in a pack.

Marmite liked to play dominoes. Runner, Sanchez and the rest liked drinking. Irie was a school bus driver by day, getaway driver by night. There were rumours he used to lock up girls in the bathroom at parties and assault them. Charmer. Monk was sweet, the quietest of the lot, so it took them by surprise when he ran his babymother down and stabbed her one night on the way home.

Then there was ’Mingo. Short for Flamingo – when things got naughty, that man could fly away and never get caught. And, finally, in his knitted Rasta hat and moccasins was Pedro, aka Wellington Augustus Miller. Or, as I no longer call him: Dad.

He’d break Mum’s nose and black out her eyes, gamble away the wages she earned as an admin clerk in an office. He lost me a baby sister too. Kicked Mum in the belly till she dropped her in a toilet. She once ended up jumping through a glass door to escape him. Doctors said she only had a 50–50 chance if they tried to remove the shards from her skull, so they left them inside. They must have done the right thing, coz she’s still here.

The X-rays revealed a freshly fractured skull, and a long, unhappy marriage’s worth of broken bones and damaged organs. I was six weeks old.

Oh yeah, he was a proper nuisance, my dad. And you know the irony? With the stepdads who followed, I still remember Mum as being the violent one.

She was working in two jobs – clerk during the day, a cleaner in the evenings – living for the weekends when she and her friends would follow the sound systems round south London, stealing drinks and befriending bouncers.

The Dirty Dozen weren’t Yardies. They weren’t in that league. Sure, they’d beat up an ice-cream van man with a chain, but their crime wasn’t organised, not in the way the Yardies’ was.

Still, anywhere they got to was pure war.

The first night my parents met, Mum watched Dad beat up a bouncer so bad they took him to the hospital. He had taken offence at being asked to pay an entry fee.

Next time they met in the Four Aces nightclub in north London.

“He had cut off his locks, he looked like a proper gentleman,” she recalled.

Not quite gentlemanly enough, of course, to hang around for my birth.

“Not one of those fathers was by my side when I was pushing dem babies out,” she still complains, as if that was the worst they did.

He popped in and out of our lives.

We lived in and out of mother and baby units, as she moved in with him and moved out again. I remember a garden, a Housing Association house in Tooting, with pears and apples and strawberries. But the council got a bit fed up with Mr Miller’s illegal gambling nights in the front room, so we lost that too.

The punches went both ways. Dad was once lay waited outside a club, after bursting a chain off this girl’s neck. Her friends tried to attack him with a samurai sword. They were the ones who ended up in the dock. Would you believe that it was poor, innocent Wellington who took to the witness stand to testify as the victim?

It wasn’t long before he was in court again.

I still remember the day those blueshirts stampeded into our house to take him away.

“BATH RAPIST GETS JAIL TERM” it said later in the News of the World.

Let me share it with you. It’s enough to make you proud.

“A man was jailed yesterday for raping a woman in her home, after a court heard his victim was so terrified she allowed him to have a bath and scrubbed his back. Wellington Miller, 33, unemployed of Dulwich, denied raping the woman.”

She was 24. It was a summer’s day in June, 1983, when my dad broke into her home in Tooting.

He told the Old Bailey he only intended to rob the place, but insisted that this kindly housewife had offered him a coffee and ran him a bath.

Because that’s what women do when men’s robbing them, ain’t it? Offer them a bath!

What actually happened was that he forced the woman to scrub his back then raped her once in the bathroom and again in the bedroom, in front of her four-year-old son. His defence lawyer blamed his drinking.

You know what he said?

“When he drinks, he goes for walks early in the morning and can’t remember what he’s done.”

I ain’t never heard of that drink – y’know, the one that turns you into an amnesiac rapist.

The judge called him an “insensitive bulldozer”.

I can think of other words. He got three years and three months.

So why is he still in prison now? Because two weeks after being released on parole, no word of a lie, he left his bail hostel in Islington and in the early hours of the morning battered down the door of a house just a few yards away, and tried to rape the mother and three girls who had barricaded themselves in a bedroom. The police arrived just in time.

He’s still in jail for that one. I’ve lost track where – he’s been moved around that much.

He got life. Could have been out by now if he’d admitted his guilt. He still insists he is innocent. Deep down I think he’s scared. I don’t think he wants to come out.

He wouldn’t be able to use a mobile phone. He wouldn’t be able to drive, or use a computer. Hell, the year my dad went down, Alan Sugar was bringing out his Amstrads. The first cool ones with the computer games, remember them? But the world has moved on while he’s been inside and my dad knows it.

So maybe it’s easier to lie about being innocent, than face the world outside.

He wrote to me when I became a bad girl. “Heard you become a gangster,” he said. “Whassat all about?”

There was no lecture. No judgement. Not even disappointment. It sounded like he was simply curious. Maybe he wanted to know what kind of gangster his daughter had become.

If I’m totally honest, for most of my young life it felt glamorous to have an incarcerated dad. No one said “rapist”, of course. It would be a long time before I found out exactly what he had done. I didn’t trouble myself to find out. All I knew was that having a dad in prison felt like something to boast about. It felt cool and rebellious. It felt like an assertion of status.

The last time I went to visit him, he claimed I wasn’t his. Said he had something to tell me, a secret he’d been keeping. He said he was convinced I must be Marmite’s. I never saw him again after that. One day, I’ll take that DNA test, but not now. Truth is, I’m scared to find out. Which result would be worse? Finding out you do have a rapist for a father. Or discovering you’d wasted all those tears and anger on a rapist who was no relation at all?

So, that’s me – a by-product of fuckery. Beyond those black marks, my past is blank. Or maybe there are no good bits to know about. As they say, badness is genetic. I think they might be right.

The Estate (#uef9f014c-c9dd-51ca-9f69-4ae5148c68e5)

They call it bipolar now, but it was manic depression back then. Mum’s episodes meant my brother and I would be shipped out around foster carers and care homes a couple times every year, a few months here, six months there, but we always ended up back in the same place in south London: the Roupell Park estate.

Althea was nine years older than me. I’ll be honest, there were times that she got on my nerves, but sometimes she could be a cool sister to have. She didn’t take no shit. Her hair was always nice. She wore beehives, French plaits and Cain rows and had a nice boyfriend. She had a good job in WH Smith and went to work every day. When Mum was ill, she had our backs. She wasn’t afraid to cuss people off, tell them to mind their own business. But as Mum’s episodes became more frequent, Althea’s patience ran out. Then of course, there was the balcony incident.

Besides, she was pregnant. Did I mention that? Not heavily – can’t imagine Mum would have had the strength to dangle two – but it was enough to make her pack her bags. I couldn’t blame her for getting out when she did. She left home early, coming back to visit now and then.

We’d started fighting a lot by that point, so can’t say I missed her.

Now Melanie. She was a different story. Mel was seven years older, and a virtual stranger. Althea he could cope with, but my dad took a dislike to this younger child taking all Mum’s attention away from him, so she was sent to live with her dad. He had married this white lady in Clapham, so yeah, Mel got lucky.

When she walked back into our lives as a teenager, after a fight with her dad, it was like having Naomi Campbell coming to visit. I remember when I first set eyes on her I couldn’t believe it.

She was modelesque, man. She had long, glossy hair and pale skin. She was tall and slim and beautiful. Nothing like Althea in her WH Smith shirt with her silver name tag. I liked the swagger of this new person I was going to have to get to know.

At last, a breath of fresh air in our claustrophobic yard. Best of all, she worked in fashion. OK, so she was a sales assistant at an Army and Navy surplus store, but don’t matter if it’s camouflage gear. Clothes are fashion, innit?

She had her own money and her uniform, man, I’ll never forget it – she had sexy tops and pencil skirts that were cowled round the waist. I thought, wow, this looks exciting. She seemed like girly fun.

Boy, was I wrong. Melanie liked partying, she liked her freedom, and she didn’t have no time for irritating siblings. Most of all, she really didn’t appreciate taking orders from an unhinged reggae fan who liked to walk round the estate naked. Her rows with Mum were vicious. She might not have been dangled off a balcony, but soon Melanie too realised Roupell Park was not for her. She lasted about six months before storming out and slamming the door behind her, without so much as a goodbye.

“Two bulls cyaan’t live inna one pen.”

That was all I remember Mum saying about the matter of another lost daughter, and Mel was soon forgotten as quickly as she had appeared. Thankfully, she left behind at least one spangly top in the washing machine.

I’d pose in front of the mirror, with socks stuffed down my front, looking forward to the day I’d be able to get dressed, look fly and hit the dancehall scene.

“You was such a lovely-looking baby,” she used to tell us at least once a day.

I preferred Yusuf’s company to the girls’. He should have been a comedian, man. We would stay up and talk all goddamn night. When we got the car bed – all red wooden wheels and a spoiler instead of a headboard – we’d spend so long wrestling over the quilt, we’d end up falling asleep in it together. Eventually, we forgot about the nightly fight for the driver’s pillow, and just topped and tailed it together.

As all baby brothers should, he worshipped his big sister. Quite right too. Anything I did, he wanted to do too.

If I wanted to take conkers and throw them at passers-by from the balcony, he would join in.

Ice cubes, eggs, anything we could get our hands on. What’s the point of having a balcony, if you can’t throw shit at people walking by?

We’d wait for the distant explosion of rage to come from the kitchen – “Where’s my fucking eggs?” – then hightail it to the caged football pitch area we called the Pen.

Ivy, the old Jamaican lady who was our first foster carer, was a spiteful old witch. She lived in Peckham, and looked elderly and sweet like somebody’s nan, but truly was the meanest woman I’d ever met. She salted our food to stop us eating too much and keep the food bills down – even over-salted the Wotsits, the bitch.

Her house smelled medieval, like the scent of an old woman, with everything velvet. Velvet curtains, velvet tablecloth, velvet wallpaper. She beat up her grandson, poor kid. He could barely look you in the eye. Made him hoover the house every day, the mad old bat. Once he made the mistake of using the hoover to try and remove a stain from her precious velvet wallpaper, so she caught him and beat him with a stick.

I ain’t letting my little brother stay some place like this, I decided. So we packed our bags and got ready to escape. Her poor grandkid pleaded to come with us.

“Please,” he said. “I don’t have money now, but when I do, I’ll pay you, hand up to God.”

He held his right hand up to the wallpapered ceiling, just in case we didn’t believe him.

“We don’t want to leave you here, honest we don’t, but we can’t take you with us.”

I told him we had to think about ourselves. He didn’t argue much after that.

We must have told the social workers about it, because later we heard that Ivy had been shut down. Wonder what happened to that poor kid. I hope he strangled the old witch and buried her in a velvet coffin in the back garden.

The next time we were sent to Birmingham to stay with a nice Muslim family, that was much more like it.

The woman’s husband looked like a real-life gorilla, big and fat and hairy, but he was lovely. They had twin daughters who they treated real nice. It felt like the middle of nowhere, though, and we couldn’t understand a word anyone was saying, so we were glad to get back home, where we understood people. Still, I missed their garden and the pistachio cakes the mother made.

Yusuf liked the residential care home the best, well, until, that is, the others discovered he still sucked his thumb. It was just like the “Dumping Ground” in the Tracy Beaker books, but with a lot more toast. Toast, toast, toast – that was all there was to eat in between meals, but at least they let you make your own meals and do your own thing. Felt like a proper little adult.

It wasn’t perfect, but it was better than living on eggshells, waiting for that music to be cranked up.

Sure, there were other angry kids raging against the system and setting off the alarms, but mostly it was just peace and quiet, innit. I was disappointed the day they came to take us home from there, but like it or not all roads led back to Roupell Park.

Mum was standing in the front room waiting for us. On the glass table was a bumper pack of Squares, and steaming plates of chicken, rice and plantain. I could see she’d spent the day cleaning. The whole house was shining.

“My babies!” She put an arm round each of us and pulled us close. “De doctors say I’m better. Gonna take my medication and mi ago do much better this time.”

She hugged us tight, and pressed her face into our hair.

“What you smelling us for?”

“I missed your smell.”

It wasn’t long after we returned from the care home that Mum made her big announcement.

We were going to move. Our eyes lit up.

“For real?”

“For real.”

We spent the whole day packing up our stuff, asking questions about our new home.

“You’ll see,” said Mum, with a smile on her lips.

“How are we going to take the car bed? We can’t go without the car bed,” said Yusuf, sensibly.

“Don’t worry about dem things. Removal men will pick ’em up later.”

We took our bags outside.

“Please, please,” we begged. “Tell us where we’re going.”

“OK. You ready?”

She pointed across the Pen.

“Tird floor. Block D.”

Our hearts sank. So much for the Big Move. We weren’t even making it out of the estate. We carried our stuff in boxes 100 metres across the grass of the courtyard, to the opposite block on the other side of the estate. We were moving from the ground floor of Elmstead House to the third floor of Deepdene House. We were moving up in the world, if only literally.

No removal van ever did pick up the car bed.

Gangland (#uef9f014c-c9dd-51ca-9f69-4ae5148c68e5)

You see, gangland is a small, claustrophobic place. It exists in small, sealed bubbles, squatting in boarded-up worlds no bigger than a postcode. It doesn’t like big, wide battlefields. It’s the smallness it likes, lurking in the dead ends and shadows of shortened ambitions, conducting its business underneath stunted horizons.

No shit. They don’t call them “the endz” for nothing.

For me, gangland began in that third floor flat, flanked by the concrete blocks of Roupell Park estate.

Later, my mental map would expand along the south London bus routes to include the lawless walkways and basement garages of the Angell Town estate, and the bored evenings making trouble around Myatt’s Fields and Brockwell Park. Feuds would stretch to Peckham and Stockwell, New Cross and Brixton.

But as a young teenager, the meaning of those postcodes beyond Roupell Park simply didn’t exist. I had not yet learned that language. They were not yet “territories”. They were still simply postcodes.

I liked Roupell Park. It didn’t feel like complete poverty, not like some of the slums in Peckham and Stockwell, the ones with the dark, dismal feeling that you’re too scared to walk through.

In Roupell Park, there was still a mixture of cultures, black and white. Some people still took pride in their window boxes, spiking them with those windmill sticks and dangling chimes from their doors. A caretaker kept the Pen tidy, and the Quaker meeting house round the corner gave us a spiritual veneer.

Less than two miles away was the house where David Bowie was born. Half a mile further, Vincent Van Gogh (both ears still intact) fell in love with a South London girl, while living briefly in a house in SW9.

Even closer was Electric Avenue, the first market street to have the luxury of lighting. “Now in the street, there is violence.” That’s how the song starts. Sounds so upbeat, but listen to it properly next time. It’s about poverty and anger and taking to the street. People forget that. They think it’s about bloody lampposts.

I remember a poster campaign during the General Election, just as I was beginning life on the road. It must have been 1992. The posters showed a smiling John Major.

“What does the Conservative Party offer a working-class kid from Brixton?” they asked.

“They made him Prime Minister.”

Good for him, innit. But I couldn’t see anyone boasting about what they were offering a cute black girl, like me.

My parents had divorced in 1981, the same year Brixton went up in flames. A decade later, a new generation had grown up to hate the boydem.

Brixton had already been bombed and blasted and cleared of slums. By the time I was growing up, it was all about failed social housing and plain-clothes policemen and their hated campaign of stop and search.

Of course, I didn’t care about any of that. I had my mum to worry about.

I would learn three important lessons living on Roupell Park. First, Fireworks Night is always the best time to buss a ting in the air. Second, getting caught ain’t cool. And third, one day your luck is going to run out.

Everyone knew us as the madwoman’s kids.

There was the white kids, who lived in a smelly flat on the fifth floor. We felt sorry for them coz their place stank, man, but they was nice kids. Then there was lovely Peggy next door, always willing to lend a bag of sugar, and Shelley and Andrew, the mixed-race kids on the fifth floor. They were popular. Everyone liked Shelley and Axe, as he’d later be known. People knew each other and helped each other when they could.

There was one newsagent who served the estate. We’d go there for ice poles in the summer. We never stole from Jay. No need. He was a good guy. If you went in there and said you were a little bit short, he would say bring it in next time. There was no point defrauding him.

He got robbed once or twice. Soon after he got a big Alsatian. No one bothered Jay after that.

At night, we’d watch the flashing lights from our window. There was always running kids and commotion. It was usually Tiefing Timmy, an Irish boy with lips like a duck, who’d speed his stolen cars around the courtyard.

Datsuns, Nissans, motorbikes. There was nothing that guy couldn’t lift. When it was dark, that’s when Tiefing Timmy and his boys would come out to play. We’d watch the nightly blue light show as the boydem chased Tiefing Timmy round the Pen. We’d laugh when he got away, and we’d throw coins at the Feds when they hauled him out and handcuffed him over the battered front of whatever car he’d stolen this time.

Obviously, some of the neighbours didn’t like us. Mum took pride in her music system. The Abyssinians, Frankie Paul, Dennis Brown, Marcia Griffiths. Old skool Jamaican reggae. She played it loud and she played it proud.

It wasn’t all bad. There were the prison visits to look forward to. They were our holiday. As soon as a letter came through the post with HMPS on the envelope we got excited: it meant there was going to be a bus journey or coach trip and a fun day out to the Isle of Wight or Dartmoor or wherever Dad had been moved to this time. We’d always get a tray of cakes. Oh yeah, it was delightful.

Depending on how recently Mum had folded up the car, sometimes we would drive.

They lay waited him in the Upper Cuts barber shop in West Norwood. Yeah, people was real upset when Axe died.

They said it was a drugs connection but Axe wasn’t one of the naughty ones. Rafik Alleyne was the guy who did it. He was 21. Axe was 25. They knew each other. People saw them knocking knuckles outside before Andrew went into Upper Cuts on Norwood High Street to get his hair cut.

Guy pulled a gun from a takeaway box and shot him in the back of the head as he sat in the barber’s chair. He went running to a minicab office in a panic looking for a getaway car, begging a driver to take him to Stockwell. He got 22 years.

His mum wrote a really sad poem for the funeral. They said she stood up, wearing big dark sunglasses, to recite it.

Who is the one that took my son,

do you really know what you have done?

This is a wake-up call to all of you,

who wants to belong to the devil’s crew.

The devil’s crew indeed. I wished I had listened to her. It would be a long time before I truly understood what she meant.

One afternoon, I had been sitting by the Pen, probably not far from Shelley’s and Andrew’s flat. I’d bunked off school as usual, and had grown bored of hopscotch and the games we drew in chalk on the crumbling surface of the court. The goal nets and basketball rings were long gone – that is, if they’d ever been there in the first place – so we used to entertain ourselves inside the cage.

The only other kid kicking around that day was Jerome. He was just one of the kids around the way. I didn’t much like him, but beggars, choosers and all that.

Was it the first time I’d ever been stabbed? I honestly can’t remember. Getting stabbed is not like getting married or buying a new car, darling. It’s just not something that sticks in your mind. Shit happens.

What I do remember is that Jerome taught me an important lesson that day.

“Hey Sour!” he’d shouted over, spying me at a loose end. “Wanna play a game?”

I shrugged.

“It’s called Flick.”

He cast a quick look around and huddled me into a corner where he felt sure no one was watching. Now he had got my attention.

Then he pulled out two flick knives.

“Here, take it.”

I took it.

The handle fitted neatly into my palm. The chrome felt smooth and polished. It was still warm from his pocket.

“Look, do what I’m doing. Flick in, flick out.”

I smiled. The mechanism was quick and light.

“Let’s ramp,” he said. Let’s muck about.

We started making phantom jabs for each other’s fists.

Imagine fencing with flick knives and you’re getting close. Some kids play it with tennis racquets. Some kinds pretend they’re on Star Wars. And some kids in Tulse Hill fence with knives.

He was quicker than me to start, but I soon caught up, matching every flick of the wrist and jolt of the fist.

I wasn’t afraid.

“See? Good, isn’t it?”

I took my eye off his blade. He jabbed towards me. As he did, I went to block.

“What the fuck are you doing, you idiot?”

He had caught my hand, piercing the fleshy pad beneath my thumb.

“You folly?” he said. “S’just a flesh wound.”

“That’s how you lose.”

You’re not playing, are you, I thought. We carried on. I was angrier this time and he knew it.

It was just me and him. I started jabbing harder, more forcefully, but he was too practised, too quick.

My pride had been hurt. I needed to make a wound for a wound. The game had now extended beyond striking the other fist. Now, the whole body was in play. We pranced back and forth, dodging contact with ragged swipes of chrome.

A warm trickle of blood was streaming down my wrist. It wasn’t gushing. It was just a gash, but enough to catch Jerome’s eye.

I got him. In the hand. While he was flinching I got him again, by the knee.

“Ah, you fucking bitch! You stabbed me.”

“That’s the point, innit? You a batty boy?”

It was just a graze.

“It’s not even deep.”

This was getting boring. I put down the knife, stepped back and examined my wound. It was deeper that I thought. The rest of my hand felt tender to touch.

Jerome seemed agitated, but tried not to show it. He wiped both knives on the grass and put them back into his pocket.

“Call it quits, yeah?”

“Whatever. Next time, bring a better knife.”

I went home and told Mum some cock and bull story about cutting myself on the fence. I ended up having to get stitches.

I decided there and then I wouldn’t be play fighting again – it was annoying and inconvenient. We had only been mucking about, but if that had been a serious situation I’d have been in trouble.

But I was grateful to Jerome for teaching an important lesson. Next time, I learned, I’d better bring a bigger knife.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/lucy-bannerman/sour-my-story-a-troubled-girl-from-a-broken-home-the-brixto/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Tracey Miller и Lucy Bannerman

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 28.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: They call me Sour. The opposite of sweet. Shanking, stabbing, steaming, robbing, I did it all, rolling with the Man Dem. I did it because I was bad. I did it because I had heart. And the reason I reckon I got away with it for so long? Because I was a girl.SOUR is the true story of a former Brixton gang girl, drug dealer and full-time criminal. A member of the Younger 28s, a notorious gang that terrorised the postcodes around Brixton in the 90s, Sour escapes a troubled family life to immerse herself in the street life of likking and linking. She never leaves her house without a knife. At the age of fifteen, she stabs an innocent man in the street, earning her unrivalled respect and ‘Top-Dog’ status amongst her crew. She believes she is invincible.But the consequences of her actions are soon to catch up with her. Waking for the second time in two weeks in a hospital bed, to the news that she is pregnant, she realises it’s time to turn her life around. Motherhood will be a rude awakening, but it may also be her saving grace.Told with raw emotions and ferocious honesty, this is the real, on-the-record, story of one woman’s descent down the rabbit hole of gangland, and her efforts, as a daughter, mother and girlfriend, to claw herself out.