Songs of the Dying Earth

George Raymond Richard Martin

Gardner Dozois

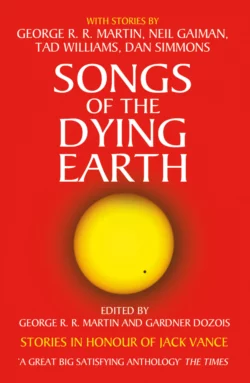

Return to the unique and evocative world of The Dying Earth in this tribute anthology featuring the most distinguished fantasists of our day. Here are twenty-one brand-new adventures set in the world of Jack Vance's greatest novel.A dim place, ancient beyond knowledge. The sun is feeble and red. A million cities have fallen to dust. Here live a few thousand souls, dying, as the Earth dies beneath them. Just a few short decades remain to the long history of our world. At the last, science and magic are one, and there is evil on Earth, distilled by time … Earth is dying.Half a century ago, Jack Vance created the world of the Dying Earth, and fantasy has never been the same. Now, for the first time, Jack has agreed to open this bizarre and darkly beautiful world to other fantasists, to play in as their very own.The list of twenty-one contributors eager to honour Jack Vance by writing for this anthology includes Neil Gaiman, Elizabeth Hand, Tanith Lee, Michael Moorcock, Terry Dowling, Lucius Shepherd, Dan Simmons, Robert Silverberg, Tad Williams, Walter Jon Williams and George R.R. Martin himself.

SONGS OF THE DYING EARTH

STORIES IN HONOUR OF JACK VANCE

Edited by

George R.R. Martin and Gardner Dozois

with an Appreciation by Dean Koontz

ROBERT SILVERBERG, MATTHEW HUGHES, TERRY DOWLING, LIZ WILLIAMS, MIKE RESNICK, WALTER JON WILLIAMS, PAULA VOLSKY, JEFF VANDERMEER, KAGE BAKER, PHYLLIS EISENSTEIN, ELIZABETH MOON, LUCIUS SHEPARD, TAD WILLIAMS, JOHN C. WRIGHT, GLEN COOK, ELIZABETH HAND, BYRON TETRICK, TANITH LEE, DAN SIMMONS, HOWARD WALDROP, GEORGE R.R. MARTIN, NEIL GAIMAN

Copyright (#ulink_f087cc7b-d8f4-56ec-86bd-4f0cf0f2e7bd)

HarperCollinsPublishers 77-85 Fulham Palace Road, Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.voyager-books.co.uk (http://www.voyager-books.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperVoyager An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 2009

Copyright © George R R Martin and Gardner Dozois 2009

Full copyright information here (#ub53d8716-ee28-4d59-b806-de0fb2928a45)

The authors assert the moral right to be identified as the authors of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007277483

Ebook Edition © SEPTEMBER 2009 ISBN: 9780007290666

Version: 2014-11-28

Dedication (#ulink_678bfa36-43cc-52f7-9d77-ccba7a681e99)

to Jack Vance, the maestro, with thanks for all the great tales, and for letting us play with your toys.

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#ub4cc6d18-3684-5733-bde5-fdf56124090f)

Title Page (#u89278272-b673-5c4c-b875-6830ee786e10)

Copyright (#uba1cddfd-52e8-5a86-a66f-94cd3aeb9333)

Dedication (#u6cbaf41a-ba2d-526f-a388-a5d1213cd033)

Thank You, Mr. Vance DEAN KOONTZ (#ufe30903f-4d20-5545-a5b5-45959a097a8e)

Preface JACK VANCE (#udb8b70c7-c180-51ea-a0dd-ed5309f58992)

The True Vintage of Erzuine Thale ROBERT SILVERBERG (#u0c072c48-2c67-5f5d-a290-d572764f96ab)

Grolion of Almery MATTHEW HUGHES (#u97b1bbb5-54e1-54b0-9c03-d59d5be636b2)

The Copsy Door TERRY DOWLING (#u63bd1195-4323-5080-862f-6929992dfa57)

Caulk the Witch-chaser LIZ WILLIAMS (#ue2f559f5-01f2-5a01-91ed-7af21262ac18)

Inescapable MIKE RESNICK (#u92902d46-4be2-5667-9a58-5f76894a08fb)

Abrizonde WALTER JON WILLIAMS (#u17f76722-85b7-5fea-bd72-7b6fa5d9271b)

The Traditions of Karzh PAULA VOLSKY (#u36728a5c-21cc-5073-a3dd-a09c7f64841a)

The Final Quest of the Wizard Sarnod JEFF VANDERMEER (#ucc400cb6-12f0-5f36-beb8-ec675354732d)

The Green Bird KAGE BAKER (#u86c4ce98-678a-5faf-932d-2916a35becbc)

The Last Golden Thread PHYLLIS EISENSTEIN (#uf098235b-dbf1-5cc5-9668-02cf48a5919e)

An Incident in Uskvosk ELIZABETH MOON (#u90634e10-34ef-5c18-9924-ad7b8ebf11b0)

Sylgarmo’s Proclamation LUCIUS SHEPARD (#u29d775d0-4fa5-5e63-ae76-293e603fafd4)

The Lamentably Comical Tragedy (or The Laughably Tragic Comedy) of Lixal Laqavee TAD WILLIAMS (#u0fbc00f1-051c-56a1-89d6-fcf9509a1bb3)

Guyal the Curator JOHN C. WRIGHT (#u1191372f-34b0-5913-8339-34edc8be478a)

The Good Magician GLEN COOK (#u53b00b9d-8fa3-5034-b9d7-bd8eee81afc4)

The Return of the Five Witch ELIZABETH HAND (#u7a86e883-3a2c-506e-9a60-f7b25ef122c4)

The Collegeum of Mauge BYRON TETRICK (#u1c3da895-03e6-572b-bf29-520ea7e82da6)

Evillo the Uncunning TANITH LEE (#ueb48bd19-0263-5c6b-9ca2-65d936f3ede2)

The Guiding Nose of Ulfänt Banderōz DAN SIMMONS (#u3ab8b92d-8685-5aa5-bb2e-56a837212f87)

Frogskin Cap HOWARD WALDROP (#u84063d7c-533c-569a-beaf-2061ee1ded53)

A Night at the Tarn House GEORGE R.R. MARTIN (#u0c7ffcb9-982d-52be-855f-05ee85410319)

An Invocation of Incuriosity NEIL GAIMAN (#ufafa8e88-3b27-56bc-9914-4ca5b8e4dfa4)

About the Publisher (#u6750903b-7eb3-50dc-bf7f-028cab72f0fc)

THANK YOU, MR. VANCE By Dean Koontz (#ulink_21fc2ad5-7405-5911-82c3-75a74e3c9d04)

IN 1966, at 21, fresh from college, I was a fool and possibly deranged, although not seriously dangerous. I was a well-read fool, especially in science fiction. For twelve years, I pored through at least a book a week in that genre. I felt that I belonged in one of the other worlds or far futures of those tales more than I did in the world and time in which I’d been born, less because I had a wide romantic streak than because I had low self-esteem and longed to shed the son-of-the-town-drunk identity that fate had given me.

During the first five years that I wrote for a living, I produced mostly science fiction. I was not good at it. I sold what I wrote—twenty novels, twenty-eight short stories—but little of that work was memorable, and some was execrable. All these years later, only two of those novels and four or five of those stories might not raise in me a suicidal urge if I reread them.

As a reader, I could tell the difference between great science fiction and the mediocre stuff, and I was drawn to the best, which I often reread. Considering that I was inspired by quality, I should not have turned out so many dreary tales. I was driven to write fast by economic necessity; Gerda and I had been married with $150 and a used car, and though bill collectors were not breaking down the door, the specter of destitution haunted me. A need for money, however, is an insufficient excuse.

In November of 1971, as I moved toward suspense and comic fiction and away from writing SF, I discovered Jack Vance. Considering the hundreds of science fiction novels I had read, I am amazed that I had not until then sampled Mr. Vance’s work. With the intention of reading him, I bought numerous paperbacks of his novels but never opened one, partly because the covers gave me a wrong impression of the contents. On my shelves today is an Ace edition of The Eyes of the Overworld, with a cover price of 45 cents, featuring Cugel the Clever in a flaring pink cape against a background of cartoonish mushrooms like giant genitalia. A 50-cent Ace edition of Big Planet features well-rendered men with ray guns riding badly drawn alien beasts of dubious anatomy. The first book I read by Jack Vance, in November 1971, was Emphyrio, published at the budget-busting price of 75 cents. The cover illustration—perhaps by Jeff Jones—was sophisticated and mystical.

Every writer has a short list of novels that electrified him, that inspired him to try new narrative techniques and fresh stylistic devices. For me, Emphyrio and The Dying Earth are such books. Enthralled with the former, I finished the entire novel without getting up from my armchair, and the same day I read the latter. Between November of 1971 and March of 1972, I read every Jack Vance novel and every piece of his short fiction published to that time—and although many more books were to come, even then he had a long bibliography. Only two other authors have so captivated me that for a time I became immersed in their work to the exclusion of all other reading: on discovering John D. MacDonald, I read thirty-four of his novels in thirty days; and after stubbornly avoiding the fiction of Charles Dickens through high school and college, I read A Tale of Two Cities in 1974 and, over the next three months, every word of fiction Dickens published.

Three things in particular fascinate me about Mr. Vance’s work, the first being a vivid sense of place. Far planets and distant future Earths are so well portrayed that they expand like real and fully colored vistas in the mind’s eye. This is achieved by many means, but primarily by close attention to architecture, first the architecture of key buildings; and in architecture I include interior design. The opening chapters of The Last Castle or The Dragon Masters contain excellent examples of this. Furthermore, when Jack Vance describes the natural world, he does so in the manner neither of a geologist nor a naturalist, nor even as a poet might describe it, but again with an eye for the architecture of nature, not merely of its geological features but also of its flora and fauna. The appearance of things does not intrigue him as much as does their structure. Consequently, his descriptions have depth and complexity from which images arise in the reader’s mind that are in fact poetic. This fascination with structures is evident in every aspect of his fiction, whether it is the structure of languages in The Languages of Pao or the structure of a system of magic in The Dying Earth; and in every novel and novelette he has written, alien cultures and far-future human societies ring true because he gives us the matrix and the lattice, the foundation and the framing on which the visible walls are stood and hung.

The second quality of Mr. Vance’s fiction that fascinates me is his masterly evocation of mood. Each of his works features a subtly modified syntax, scheme of imagery, and coherent system of figures of speech unique to that tale, usually in the service of the implicit meaning but always in the service of mood, which itself grows from his subtext, as it should. I am a sucker for mood. I can forgive a writer many faults if he has the capacity to weave a warp and weft of mood from page one to the end of his story. One of the great things about Jack Vance is that the reader is enthralled by the mood of each piece without having to overlook any faults.

Third, although the people in a Vance science-fiction novel are less real than those in the few mystery novels that he wrote, and are constricted by the conventions of a genre that for many decades valued color and action and cool ideas above characters with depth, they are memorable and, over the body of his work, reveal that the author puts much of himself in the cast members of his tales. The recognition of the author intimately threaded through the tapestry of key characters exposed to me, back there in 1971 and ‘72, a primary reason why my science fiction often failed: as a child raised in poverty and always-pending violence, I had read science fiction largely for escape; therefore, as a writer, I was loath to draw upon my most intense life experiences when writing SF, but instead usually wrote it as sheer escapism.

In spite of the exotic and hypercolorful nature of Jack Vance’s work, reading so much of his fiction in such a short time led me to the realization that I was withholding my soul from the stories that I wrote. If I had remained in science fiction after this moment of enlightenment, I would have written books radically different from those that I had produced between 1967 and 1971. But I immersed myself in the Vance universe as I was moving on to suspense novels like Chase and comic novels like Hanging On; consequently, the lesson I learned from him was applied to everything I wrote after leaving his preferred genre.

I know nothing about Jack Vance’s life, only the fiction that he has written. During those five months in 1971 and ’72, however, and every time I have read a Vance novel in the years since, I have known I am reading the work of someone who enjoyed a largely happy childhood and perhaps an idyllic one. If I’m wrong about this, I don’t want to be corrected. When I settle into a Vance story, I see the sense of wonder and the confidence and the generous spirit of someone who was given a childhood and adolescence free from fear and without want, who used those years to explore the world and, through that exploration, came to embrace it with exuberance. Although my journey to a happy adulthood followed a dark and sometimes desperate path, I do not envy Jack Vance if his route was sunnier; instead, I delight in the worlds of wonder that his experiences made it possible for him to create, and not least of all in that singular world that awaits its end under a fading sun.

The Dying Earth and its sequels comprise one of the most powerful fantasy/science-fiction concepts in the history of the genre. They are packed with adventure but also with ideas, and the vision of uncounted human civilizations stacked one atop another like layers in a phyllo pastry thrills even as it induces a sense of awe—awe in the purest sense of the word—the irresistible yielding of the mind to something so grand in character that it cannot be entirely grasped in all its ramifications but necessarily harbors an ineffable mystery at its heart. The fragility and transience of all things, the nobility of humanity’s struggle against the certainty of an entropic resolution, gives The Dying Earth a poignancy rare in novels of fantastic romance.

Thank you, Mr. Vance, for so much pleasure over the years and for an important moment of enlightenment that made my writing better than it would have been if I had never read Emphyrio, The Dying Earth, and all your other marvelous stories.

PREFACE By Jack Vance (#ulink_33ee018a-04f5-5395-aa63-f664b4292f5d)

I WAS happily surprised when I learned that so many high-echelon, top-drawer writers had undertaken to produce a set of stories based upon some of my early work. Here I must insert a caveat: some may regard the above sentiment as the usual boilerplate. In no way! For a fact, I am properly flattered by this sort of recognition.

I wrote The Dying Earth while working as an able seaman aboard cargo ships, cruising, for the most part, back and forth across the Pacific. I would take my clipboard and fountain pen out on deck, find a place to sit, look out over the long rolling blue swells: ideal circumstances in which to let the imagination wander.

The influences which underlie these stories go back to when I was ten or eleven years old and subscribed to Weird Tales magazine. My favorite writer was C. L. Moore, whom to this day I revere. My mother had a taste for romantic fantasy, and she collected books by an Edwardian writer called Robert Chambers, who is now all but forgotten. He wrote such novels as The King in Yellow, The Maker of Moons, The Tracer of Lost Persons and many others. Also on our bookshelves were the Oz books of L. Frank Baum, as well as Tarzan of the Apes and the Barsoom sequences of Edgar Rice Burroughs. Around this same time Hugo Gernsback began publishing Amazing Stories Monthly and Amazing Stories Quarterly; I devoured both on a regular basis. The fairy tales of Lord Dunsany, an Irish peer, were also a substantial influence; and I cannot ignore the great Jeffery Farnol, another forgotten author, who wrote romantic swashbucklers. In short, it is fair to say that almost everything I read in my early years became transmuted into some aspect of my own style.

Many years after the first publication of The Dying Earth, I used the same setting for the adventures of Cugel and Rhialto, although these books are quite different from the original tales in mood and atmosphere. It is nice to hear that these stories continue to live in the minds of readers and writers alike. To both, and to everyone concerned with the production of this collection, I tip my hat in thanks and appreciation. And to the reader specifically, I promise that you, upon turning the page, will be much entertained.

—Jack Vance

Oakland, 2008

ROBERT SILVERBERG The True Vintage of Erzuine Thale (#ulink_09472186-d8c6-5381-8d09-73829169ab97)

ROBERT SILVERBERG is one of the most famous SF writers of modern times, with dozens of novels, anthologies, and collections to his credit. As both writer and editor (he was editor of the original anthology series New Dimensions, perhaps the most acclaimed anthology series of its era), Silverberg was one of the most influential figures of the Post New Wave era of the ‘70s, and continues to be at the forefront of the field to this very day, having won a total of five Nebula Awards and four Hugo Awards, plus SFWA’s prestigious Grandmaster Award.

His novels include the acclaimed Dying Inside, Lord Valentine’s Castle, The Book of Skulls, Downward to the Earth, Tower of Glass, Son of Man, Nightwings, The World Inside, Born With The Dead, Shadrack In The Furnace, Thorns, Up the Line, The Man in the Maze, Tom O’Bedlam, Star of Gypsies, At Winter’s End, The Face of the Waters, Kingdoms of the Wall, Hot Sky at Morning, The Alien Years, Lord Prestimion, Mountains of Majipoor, two novel-length expansions of famous Isaac Asimov stories, Nightfall and The Ugly Little Boy, The Longest Way Home, and the mosaic novel Roma Eterna. His collections include Unfamiliar Territory, Capricorn Games, Majipoor Chronicles, The Best of Robert Silverberg, The Conglomeroid Cocktail Party, Beyond the Safe Zone, and the ongoing program from Subterranean Press to publish his collected stories, which now runs to four volumes, and Phases of the Moon: Stories from Six Decades, and a collection of early work, In the Beginning. His reprint anthologies are far too numerous to list here, but include The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume One and the distinguished Alpha series, among dozens of others. He lives with his wife, writer Karen Haber, in Oakland, California.

Here he takes us south of Almery to languid Ghiusz on the Claritant Peninsula adjoining the Klorpentine Sea, a place as balmy as it gets on The Dying Earth, to meet a poet and philosopher who takes to heart the ancient adage, Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we die. Especially drink.

The True Vintage of Erzuine Thale ROBERT SILVERBERG (#ulink_09472186-d8c6-5381-8d09-73829169ab97)

Puillayne of Ghiusz was a man born to every advantage life offers, for his father was the master of great estates along the favored southern shore of the Claritant Peninsula, his mother was descended from a long line of wizards who held hereditary possession of many great magics, and he himself had been granted a fine strongthewed body, robust health, and great intellectual power.

Yet despite these gifts, Puillayne, unaccountably, was a man of deep and ineradicable melancholic bent. He lived alone in a splendid sprawling manse overlooking the Klorpentine Sea, a place of parapets and barbicans, loggias and pavilions, embrasures and turrets and sweeping pilasters, admitting only a few intimates to his solitary life. His soul was ever clouded over by a dark depressive miasma, which Puillayne was able to mitigate only through the steady intake of strong drink. For the world was old, nearing its end, its very rocks rounded and smoothed by time, every blade of grass invested with the essence of a long antiquity, and he knew from his earliest days that futurity was an empty vessel and only the long past supported the fragile present. This was a source of extreme infestivity to him. By assiduous use of drink, and only by such use of it, he could succeed from time to time in lifting his gloom, not through the drink itself but through the practice of his art, which was that of poetry: his wine was his gateway to his verse, and his verse, pouring from him in unstoppable superiloquent abundance, gave him transient release from despond. The verse forms of every era were at his fingertips, be they the sonnet or the sestina or the villanelle or the free chansonette so greatly beloved by the rhyme-loathing poets of Sheptun-Am, and in each of them he displayed ineffable mastery. It was typical of Puillayne, however, that the gayest of his lyrics was invariably tinged with ebon despair. Even in his cups, he could not escape the fundamental truth that the world’s day was done, that the sun was a heat-begrudging red cinder in the darkening sky, that all striving had been in vain for Earth and its denizens; and those ironies contaminated his every thought.

And so, and so, cloistered in his rambling chambers on the heights above the metropole of Ghiusz, the capital city of the happy Claritant that jutted far out into the golden Klorpentine, sitting amidst his collection of rare wines, his treasures of exotic gems and unusual woods, his garden of extraordinary horticultural marvels, he would regale his little circle of friends with verses such as these:

The night is dark. The air is chill.

Silver wine sparkles in my amber goblet.

But it is too soon to drink. First let me sing.

Joy is done! The shadows gather!

Darkness comes, and gladness ends!

Yet though the sun grows dim, My soul takes flight in drink.

What care I for the crumbling walls?

What care I for the withering leaves?

Here is wine!

Who knows? This could be the world’s last night.

Morning, perhaps, will bring a day without dawn.

The end is near. Therefore, friends, let us drink!

Darkness…darkness…

The night is dark. The air is chill.

Therefore, friends, let us drink!

Let us drink!

“How beautiful those verses are,” said Gimbiter Soleptan, a lithe, playful man given to the wearing of green damask pantaloons and scarlet sea-silk blouses. He was, perhaps, the closest of Puillayne’s little band of companions, antithetical though he was to him in the valence of his nature. “They make me wish to dance, to sing—and also…” Gimbiter let the thought trail off, but glanced meaningfully to the sideboard at the farther end of the room.

“Yes, I know. And to drink.”

Puillayne rose and went to the great sideboard of black candana overpainted with jagged lines of orpiment and gambodge and flake blue in which he kept the wines he had chosen for the present week. For a moment, he hesitated among the tight-packed row of flasks. Then his hand closed on the neck of one fashioned from pale-violet crystal, through which a wine of radiant crimson glowed with cheery insistence.

“One of my best,” he announced. “A claret, it is, of the Scaumside vineyard in Ascolais, waiting forty years for this night. But why let it wait longer? There may be no later chances.”

“As you have said, Puillayne. ‘This could be the world’s last night.’ But why, then, do you still disdain to open Erzuine Thale’s True Vintage? By your own argument, you should seize upon it while opportunity yet remains. And yet you refuse.”

“Because,” Puillayne said, smiling gravely, and glancing toward the cabinet of embossed doors where that greatest of all wines slept behind barriers of impenetrable spells, “this may, after all, not be the world’s last night, for none of the fatal signs have made themselves apparent yet. The True Vintage deserves only the grandest of occasions. I shall wait a while longer to broach it. But the wine I have here is itself no trifle. Observe me now.”

He set out a pair of steep transparent goblets rimmed with purple gold, murmured the word to the wine-flask that unsealed its stopper, and held it aloft to pour. As the wine descended into the goblet it passed through a glorious spectrum of transformation, now a wild scarlet, now deep crimson, now carmine, mauve, heliotrope shot through with lines of topaz, and, as it settled to its final hue, a magnificent coppery gold. “Come,” said Puillayne, and led his friend to the viewing-platform overlooking the bay, where they stood side by side, separated by the great vase of black porcelain that was one of Puillayne’s most cherished treasures, in which a porcelain fish of the same glossy black swam insolently in the air.

Night had just begun to fall. The feeble red sun hovered precariously over the western sea. Fierce eye-stabbing stars already blazed furiously out of the dusky sky to north and south of it, arranging themselves in the familiar constellations: the Hoary Nimbus, the Panoply of Swords, the Cloak of Cantenax, the Claw. The twilight air was cooling swiftly. Even here in this land of the far south, sheltered by the towering Kelpusar range from the harsh winds that raked Almery and the rest of Grand Motholam, there was no escape from the chill of the night. Everywhere, even here, such modest daily warmth as the sun afforded fled upward through the thinning air the moment that faint light was withdrawn.

Puillayne and Gimbiter were silent a time, savoring the power of the wine, which penetrated subtly, reaching from one region of their souls to the next until it fastened on the heart. For Puillayne, it was the fifth wine of the day, and he was well along in the daily defeat of his innate somberness of spirit, having brought himself to the outer borderlands of the realm of sobriety. A delightful gyroscopic instability now befuddled his mind. He had begun with a silver wine of Kauchique flecked with molecules of gold, then had proceeded to a light ruby wine of the moorlands, a sprightly sprezzogranito from Cape Thaumissa, and, finally, a smooth but compelling dry Harpundium as a prelude to this venerable grandissimus that he currently was sharing with his friend. That progression was a typical one for him. Since early manhood he had rarely passed a waking hour without a goblet in his hand.

“How beautiful this wine is,” said Gimbiter finally.

“How dark the night,” said Puillayne. For even now he could not escape the essentially rueful cast of his thoughts.

“Forget the darkness, dear friend, and enjoy the beauty of the wine. But no: they are forever mingled for you, are they not, the darkness and the wine. The one encircles the other in ceaseless chase.”

This far south, the sun plunged swiftly below the horizon. The ferocity of the starlight was remorseless now. The two men sipped thoughtfully.

Gimbiter said, after a further span of silence, “Do you know, Puillayne, that strangers are in town asking after you?”

“Strangers, indeed? And asking for me?”

“Three men from the north. Uncouth-looking ones. I have this from my gardener, who tells me that they have been making inquiries of your gardener.”

“Indeed,” said Puillayne, with no great show of interest.

“They are a nest of rogues, these gardeners. They all spy on us, and sell our secrets to any substantial bidder.”

“You tell me no news here, Gimbiter.”

“Does it not concern you that rough-hewn strangers are asking questions?”

Puillayne shrugged. “Perhaps they are admirers of my verses, come to hear me recite.”

“Perhaps they are thieves, come from afar to despoil you of some of your fabled treasures.”

“Perhaps they are both. In that case, they must hear my verses before I permit any despoiling.”

“You are very casual, Puillayne.”

“Friend, the sun itself is dying as we stand here. Shall I lose sleep over the possibility that strangers may take some of my trinkets from me? With such talk you distract us from this unforgettable wine. I beg you, drink, Gimbiter, and put these strangers out of your mind.”

“I can put them from mine,” said Gimbiter, “but I wish you would devote some part of yours to them.” And then he ceased to belabor the point, for he knew that Puillayne was a man utterly without fear. The profound bleakness that lay at the core of his spirit insulated him from ordinary cares. He lived without hope and therefore without uneasiness. And by this time of day, Gimbiter understood, Puillayne had further reinforced himself within an unbreachable palisade of wine.

The three strangers, though, were troublesome to Gimbiter. He had gone to the effort of inspecting them himself earlier that day. They had taken lodgings, said his head gardener, at the old hostelry called the Blue Wyvern, between the former ironmongers’ bazaar and the bazaar of silk and spices, and it was easy enough for Gimbiter to locate them as they moved along the boulevard that ran down the spine of the bazaar quarter. One was a squat, husky man garbed in heavy brown furs, with purple leather leggings and boots, and a cap of black bearskin trimmed with a fillet of gold. Another, tall and loose-limbed, sported a leopardskin tarboosh, a robe of yellow muslin, and red boots ostentatiously spurred with the spines of the roseate urchin. The third, clad unpretentiously in a simple gray tunic and a quilted green mantle of some coarse heavy fabric, was of unremarkable stature and seemed all but invisible beside his two baroque confederates, until one noticed the look of smouldering menace in his deep-set, resolute, reptilian eyes, set like obsidian ellipsoids against his chalky-hued face.

Gimbiter made such inquiries about them at the hostelry as were feasible, but all he could learn was that they were mercantile travelers from Hither Almery or even farther north, come to the southlands on some enterprise of profit. But even the innkeeper knew that they were aware of the fame of the metropole’s great poet Puillayne, and were eager to achieve an audience with him. And therefore Gimbiter had duly provided his friend with a warning; but he was sadly aware that he could do no more than that.

Nor was Puillayne’s air of unconcern an affectation. One who has visited the mephitic shores of the Sea of Nothingness and returned is truly beyond all dismay. He knows that the world is an illusion built upon a foundation of mist and wind, and that it is great folly to attach oneself in any serious way to any contrary belief. During his more sober moments, of course, Puillayne of Ghiusz was as vulnerable to despair and anxiety as anyone else; but he took care to reach with great speed for his beloved antidote the instant that he felt tendrils of reality making poisonous incursions through his being. But for wine, he would have had no escape from his eternally sepulchral attitudinizing.

So the next day, and the next, days that were solitary by choice for him, Puillayne moved steadfastly through his palace of antiquarian treasures on his usual diurnal rounds, rising at day-break to bathe in the spring that ran through his gardens, then breakfasting on his customary sparse fare, then devoting an hour to the choice of the day’s wines and sampling the first of them.

In mid-morning, as the glow of the first flask of wine still lingered in him, he sat sipping the second of the day and reading awhile from some volume of his collected verse. There were fifty or sixty of them by now, bound identically in the black vellum made from the skin of fiendish Deodands that had been slaughtered for the bounty placed upon such fell creatures; and these were merely the poems that he had had sufficient sobriety to remember to indite and preserve, out of the scores that poured from him so freely. Puillayne constantly read and reread them with keen pleasure. Though he affected modesty with others, within the shelter of his own soul he had an unabashed admiration for his poems, which the second wine of the day invariably amplified.

Afterward, before the second wine’s effect had completely faded, it was his daily practice to stroll through the rooms that held his cabinet of wonders, inspecting with ever-fresh delight the collection of artifacts and oddities that he had gathered during youthful travels that had taken him as far north as the grim wastes of Fer Aquila, as far to the east as the monsterinfested deadlands beyond the Land of the Falling Wall, where ghouls and deadly grues swarmed and thrived, as far west as ruined Ampridatvir and sullen Azederach on the sunset side of the black Supostimon Sea. In each of these places, the young Puillayne had acquired curios, not because the assembling of them had given him any particular pleasure in and of itself, but because the doing of it turned his attention for the moment, as did the drinking of wine, from the otherwise inescapable encroachment of gloom that from boyhood on had perpetually assailed his consciousness. He drew somber amusement now from fondling these things, which recalled to him some remote place he had visited, summoning up memories of great beauty and enchanting peace, or arduous struggle and biting discomfort, it being a matter of no importance to him which it might have been, so long as the act of remembering carried him away from the here and now.

Then he would take his lunch, a repast scarcely less austere than his morning meal had been, always accompanying it by some third wine chosen for its soporific qualities. A period of dozing invariably followed, and then a second cooling plunge in the garden spring, and then—it was a highlight of the day—the ceremonial opening of the fourth flask of wine, the one that set free his spirit and allowed the composition of that day’s verses. He scribbled down his lines with haste, never pausing to revise, until the fervor of creation had left him. Once more, then, he read, or uttered the simple spell that filled his bayside audifactorium with music. Then came dinner, a more notable meal than the earlier two, one that would do justice to the fifth and grandest wine of the day, in the choosing of which he had devoted the greatest of care; and then, hoping as ever that the dying sun might perish in the night and release him at last from his funereal anticipations, he gave himself to forlorn dreamless sleep.

So it passed for the next day, and the next, and, on the third day after Gimbiter Soleptan’s visit, the three strangers of whom Gimbiter had warned him presented themselves at last at the gates of his manse.

They selected for their unsolicited intrusion the hour of the second wine, arriving just as he had taken one of the vellum-bound volumes of his verse from its shelf. Puillayne maintained a small staff of wraiths and revenants for his household needs, disliking as he did the use of living beings as domestic subordinates, and one of these pallid eidolons came to him with news of the visitors.

Puillayne regarded the ghostly creature, which just then was hovering annoyingly at the borders of transparency as though attempting to communicate its own distress, with indifference. “Tell them they are welcome. Admit them upon the half hour.”

It was far from his usual custom to entertain visitors during the morning hours. The revenant was plainly discommoded by this surprising departure from habit. “Lordship, if one may venture to express an opinion—”

“One may not. Admit them upon the half hour.”

Puillayne used the interval until then to deck himself in formal morning garb: a thin tunic of light color, a violet mantle, laced trousers of the same color worn over underdrawers of deep red, and, above all the rest, a stiff unlined garment of a brilliant white. He had already selected a chilled wine from the Bay of Sanreale, a brisk vintage of a shimmering metallicgray hue, for his second wine; now he drew forth a second flask of it and placed it beside the first. The house-wraith returned, precisely upon the half hour, with Puillayne’s mysterious guests.

They were, exactly as Gimbiter Soleptan had opined, a rough-hewn, uncouth lot. “I am Kesztrel Tsaye,” announced the shortest of the three, who seemed to be the dominant figure: a burly person wrapped in the thick shaggy fur of some wild beast, and topped with a gold-trimmed cap of a different, glossier fur. His dense black beard encroached almost completely on his blunt, unappealing features, like an additional shroud of fur. “This is Unthan Vyorn”—a nod toward a lanky, insolentlooking fellow in a yellow robe, flamboyantly baroque red boots, and an absurd betasseled bit of headgear that displayed a leopard’s spots—“and this,” he said, glancing toward a third man, pale and unremarkably garbed, notable mainly for an appearance of extreme inconsequence bordering on nonpresence, but for his eyes, which were cold and brooding, “is Malion Gainthrust. We three are profound admirers of your great art, and have come from our homes in the Maurenron foothills to express our homage.”

“I can barely find words to convey the extreme delight I experience now, as I stand in the very presence of Puillayne of Ghiusz,” said lanky Unthan Vyorn in a disingenuously silken voice with just the merest hint of sibilance.

“It seems to me that you are capable of finding words readily enough,” Puillayne observed. “But perhaps you mean only a conventional abnegation. Will you share my wine with me? At this hour of the morning, I customarily enjoy something simple, and I have selected this Sanreale.”

He indicated the pair of rounded gray flasks. But from the depths of his furs, Kesztrel Tsaye drew two globular green flasks of his own and set them on the nearby table. “No doubt your choice is superb, master. But we are well aware of your love of the grape, and among the gifts we bring to you are these carboys of our own finest vintage, the celebrated azure ambrosia of the Maurenrons, with which you are, perhaps, unfamiliar, and which will prove an interesting novelty to your palate.”

Puillayne had not, in truth, ever tasted the so-called ambrosia of the Maurenrons, but he understood it to be an acrid and deplorable stuff, fit only for massaging cramped limbs. Yet he maintained an affable cordiality, studiously examining the nearer of the two carboys, holding it to the light, hefting it as though to determine the specific gravity of its contents. “The repute of your wines is not unknown to me,” he said diplomatically. “But I propose we set these aside for later in the day, since, as I have explained, I prefer only a light wine before my midday meal, and perhaps the same is true of you.” He gave them an inquisitive look. They made no objection; and so he murmured the spell of opening and poured out a ration of the Sanreale for each of them and himself.

By way of salute, Unthan Vyorn offered a quotation from one of Puillayne’s best-known little pieces:

What is our world? It is but a boat

That breaks free at sunset, and drifts away

Without a trace.

His intonation was vile, his rhythm was uncertain, but at least he had managed the words accurately, and Puillayne supposed that his intentions were kindly. As he sipped his wine, he studied this odd trio with detached curiosity. They seemed like crude ruffians, but perhaps their unpolished manner was merely the typical style of the people of the Maurenrons, a locality to which his far-flung travels had never taken him. For all he knew, they were dukes or princes or high ministers of that northern place. He wondered in an almost incurious way what it was that they wanted with him. Merely to quote his own poetry to him was an insufficient motive for traveling such a distance. Gimbiter believed that they were malevolent; and it might well be that Gimbiter, a shrewd observer of mankind, was correct in that. For the nonce, however, his day’s intake of wine had fortified him against anxiety on that score. To Puillayne, they were at the moment merely a puzzling novelty. He would wait to see more.

“Your journey,” he said politely, “was it a taxing one?”

“We know some small magics, and we had a few useful spells to guide us. Going through the Kelpusars, there was only one truly difficult passage for us,” said Unthan Vyorn, “which was the crossing of the Mountain of the Eleven Uncertainties.”

“Ah,” said Puillayne. “I know it well.” It was a place of bewildering confusion, where a swarm of identical peaks confronted the traveler and all roads seemed alike, though only one was correct and the others led into dire unpleasantness. “But you found your way through, evidently, and coped with equal deftness with the Gate of Ghosts just beyond, and the perilous Pillars of Yan Sfou.”

“The hope of attaining the very place where now we find ourselves drew us onward through all obstacles,” Unthan Vyorn said, outdoing even himself in unctuosity of tone. And again he quoted Puillayne:

The mountain roads we traveled rose ten thousand cilavers high.

The rivers we crossed were more turbulent than a hundred demons.

And our voices were lost in the thunder of the cataracts.

We cut through brambles that few swords could slash.

And then beyond the mists we saw the golden Klorpentine

And it was as if we had never known hardship at all.

How barbarously he attacked the delicate lines! How flat was his tone as he came to the ecstatic final couplet! But Puillayne masked his scorn. These were foreigners; they were his guests, however self-invited they might be; his responsibility was to maintain them at their ease. And he found them diverting, in their way. His life in these latter years had slipped into inflexible routine. The advent of poetry-quoting northern barbarians was an amusing interlude in his otherwise constricted days. He doubted more than ever, now, Gimbiter’s hypothesis that they meant him harm. There seemed nothing dangerous about these three except, perhaps, the chilly eyes of the one who did not seem to speak. His friend Gimbiter evidently had mistaken bumptiousness for malversation and malefic intent.

Fur-swathed Kesztrel Tsaye said, “We know, too, that you are a collector of exotica. Therefore we bring some humble gifts for your delight.” And he, too, offered a brief quotation:

Let me have pleasures in this life

For the next is a dark abyss!

“If you will, Malion Gainthrust—”

Kesztrel Tsaye nodded to the icy-eyed silent man, who produced from somewhere a sack that Puillayne had not previously noticed, and drew from it a drum of red candana covered with taut-stretched thaupin-hide, atop which nine red-eyed homunculi performed an obscene dance. This was followed by a little sphere of green chalcedony out of which a trapped and weeping demon peered, and that by a beaker which overflowed with a tempting aromatic yellow liquid that tumbled to the floor and rose again to return to the vessel from which it had come. Other small toys succeeded those, until gifts to the number of ten or twelve sat arrayed before Puillayne.

During this time, Puillayne had consumed nearly all the wine from the flask he had reserved for himself, and he felt a cheering dizziness beginning to steal over him. The three visitors, though he had offered them only a third as much apiece, had barely taken any. Were they simply abstemious? Or was the shimmering wine of Sanreale too subtle for their jackanapes palates?

He said, when it appeared that they had exhausted their display of gewgaws for him, “If this wine gives you little gratification, I can select another and perhaps superior one for you, or we could open that which you have brought me.”

“It is superb wine, master,” Unthan Vyorn said, “and we would expect no less from you. We know, after all, that your cellar is incomparable, that it is a storehouse of the most treasured wines of all the world, that in fact it contains even the unobtainable wine prized beyond all others, the True Vintage of Erzuine Thale. This Sanreale wine you have offered us is surely not in a class with that; but it has much merit in its own way and if we drink it slowly, it is because we cherish every swallow we take. Simply to be drinking the wine of Puillayne of Ghiusz in the veritable home of Puillayne of Ghiusz is an honor so extreme that it constringes our throats with joy, and compels us to drink more slowly than otherwise we might.”

“You know of the True Vintage, do you?” Puillayne asked.

“Is there anyone who does not? The legendary wine of the Nolwaynes who have reigned in Gammelcor since the days when the sun had the brightness of gold—the wine of miracles, the wine that offers the keenest of ecstasies that it is possible to experience—the wine that opens all doors to one with a single sip—” Unshielded covetousness now gleamed in the lanky man’s eyes. “If only we could enjoy that sip! Ah, if only we could merely have a glimpse of the container that holds that wondrous elixir!”

“I rarely bring it forth, even to look at it,” said Puillayne. “I fear that if I were to take it from its place of safekeeping, I would be tempted to consume it prematurely, and that is not a temptation to which I am ready to yield.”

“A man of iron!” marveled Kesztrel Tsaye. “To possess the True Vintage of Erzuine Thale, and to hold off from sampling it! And why, may I ask, do you scruple to deny yourself that joy of joys?”

It was a question Puillayne had heard many times before, for his ownership of the True Vintage was not something he had concealed from his friends. “I am, you know, a prodigious scribbler of minor verse. Yes,” he said, over their indignant protests, “minor verse, such a torrent of it that it would fill this manse a dozen times over if I preserved it all. I keep only a small part.” He gestured moodily at the fifty volumes bound in Deodand vellum. “But somewhere within me lurks the one great poem that will recapitulate all the striving of earthly history, the epic that will be the sum and testament of us who live as we do on the precipice at the edge of the end of days. Someday I will feel that poem brimming at the perimeters of my brain and demanding release. That feeling will come, I think, when our sun is in its ultimate extremity, and the encroaching darkness is about to arrive. And then, only then, will I broach the seal on the True Vintage, and quaff the legendary wine, which indeed opens all doors, including the door of creation, so that its essence will liberate the real poet within me, and in my final drunken joy I will be permitted to set down that one great poem that I yearn to write.”

“You do us all an injustice, master, if you wait to write that epic until the very eve of our doom,” said Unthan Vyorn in a tone of what might almost have been sorrow sincerely framed. “For how will we be able to read it, when all has turned to ice and darkness? No poems will circulate among us as we lie there perishing in the final cold. You deny us your greatness! You withhold your gift!”

“Be that as it may,” Puillayne said, “the time is not yet for opening that bottle. But I can offer you others.”

From his cabinet, he selected a generous magnum of ancient Falernian, which bore a frayed label, yellowed and parched by time. The great rounded flask lacked its seal and it was obvious to all that the container was empty save for random crusts of desiccated dregs scattered about its interior. His visitors regarded it with puzzlement. “Fear not,” said Puillayne. “A mage of my acquaintance made certain of my bottles subject to the Spell of Recrudescent Fluescence, among them this one. It is inexhaustibly renewable.”

He turned his head aside and gave voice to the words, and, within moments, miraculous liquefaction commenced. While the magnum was filling, he summoned a new set of goblets, which he filled near to brimming for his guests and himself.

“It is a wondrous wine,” said Kesztrel Tsaye after a sip or two. “Your hospitality knows no bounds, master.” Indeed, such parts of his heavily bearded face that were visible were beginning to show a ruddy radiance. Unthan Vyorn likewise displayed the effects of the potent stuff, and even the taciturn Malion Gainthrust, sitting somewhat apart as though he had no business in this room, seemed to evince some reduction of his habitual glower.

Puillayne smiled benignly, sat back, let tranquility steal over him. He had not expected to be drinking the Falernian today, for it was a forceful wine, especially at this early hour. But he saw no harm in somewhat greater midday intoxication than he habitually practiced. Why, he might even find himself producing verse some hours earlier than usual. These uncouth disciples of his would probably derive some pleasure from witnessing the actual act of creation. Meanwhile, sipping steadily, he felt the walls around him beginning to sway and glide, and he ascended within himself in a gradual way until he felt himself to be floating slightly outside and above himself, a spectator of his own self, with something of a pleasant haze enveloping his mind.

Somewhat surprisingly, his guests, gathered now in a circle about him, appeared to be indulging in a disquisition on the philosophy of criminality.

Kesztrel Tsaye offered the thought that the imminence of the world’s demise freed one from all the restraints of law, for it mattered very little how one behaved if shortly all accounts were to be settled with equal finality. “I disagree,” said Unthan Vyorn. “We remain responsible for our acts, since, if they transgress against statute and custom, they may in truth hasten the end that threatens us.”

Interposing himself in their conversation, Puillayne said dreamily, “How so?”

“The misdeeds of individuals,” Unthan Vyorn replied, “are not so much offenses against human law as they are ominous disturbances in a complex filament of cause and effect by which mankind is connected on all sides with surrounding nature. I believe that our cruelties, our sins, our violations, all drain vitality from our diminishing sun.”

Malion Gainthrust stirred restlessly at that notion, as though he planned at last to speak, but he controlled himself with visible effort and subsided once more into remoteness.

Puillayne said, “An interesting theory: the cumulative infamies and iniquities of our species, do you say, have taken a toll on the sun itself over the many millennia, and so we are the architects of our own extinction?”

“It could be, yes.”

“Then it is too late to embrace virtue, I suspect,” said Puillayne dolefully. “Through our incorrigible miscreancy we have undone ourselves beyond repair. The damage is surely irreversible in this late epoch of the world’s long existence.” And he sighed a great sigh of unconsolable grief. To his consternation, he found the effects of the long morning’s drinking abruptly weakening: the circular gyration of the walls had lessened and that agreeable haze had cleared, and he felt almost sober again, defenseless against the fundamental blackness of his intellective processes. It was a familiar event. No quantity of wine was sufficient to stave off the darkness indefinitely.

“You look suddenly troubled, master,” Kesztrel Tsaye observed. “Despite the splendor of this wine, or perhaps even because of it, I see that some alteration of mood has overtaken you.”

“I am reminded of my mortality. Our dim and shriveled sun—the certainty of imminent oblivion—”

“Ah, master, consider that you should be cheered by contemplation of the catastrophe that is soon to overcome us, rather than being thrust, as you say, into despond.”

“Cheered?”

“Most truly. For we each must have death come unto us in our time—it is the law of the universe—and what pain it is as we lie dying to know that others will survive after we depart! But if all are to meet their end at once, then there is no reason to feel the bite of envy, and we can go easily as equals into our common destruction.”

Puillayne shook his head obstinately. “I see merit in this argument, but little cheer. My death inexorably approaches, and that would be a cause of despair to me whether or not others might survive. Envy of those who survive is not a matter of any moment to me. For me, it will be as though all the cosmos dies when I do, and the dying of our sun adds only an additional layer of regret to what is already an infinitely regrettable outcome.”

“You permit yourself to sink into needless brooding, master,” said Unthan Vyorn airily. “You should have another goblet of wine.”

“Yes. These present thoughts of mine are pathetically insipid, and I shame myself by giving rein to them. Even in the heyday of the world, when the bright yellow sun blazed forth in full intensity, the concept of death was one that every mature person was compelled to face, and only cowards and fools looked toward it with terror or rage or anything else but acceptance and detachment. One must not lament the inevitable. But it is my flaw that I am unable to escape such feelings. Wine, I have found, is my sole anodyne against them. And even that is not fully satisfactory.”

He reached again for the Falernian. But Kesztrel Tsaye, interposing himself quickly, said, “That is the very wine that has brought this adverse effect upon you, master. Let us open, instead, the wine of our country that was our gift to you. You may not be aware that it is famed for its quality of soothing the troubled heart.” He signalled to Malion Gainthrust, who sprang to his feet, deftly unsealed the two green carboys of Maurenron ambrosia, and, taking fresh goblets from Puillayne’s cabinet, poured a tall serving of the pale bluish wine from one carboy for Puillayne and lesser quantities from the other for himself and his two companions.

“To your health, master. Your renewed happiness. Your long life.”

Puillayne found their wine unexpectedly fresh and vigorous, with none of the rough and sour flavor he had led himself to anticipate. He followed his first tentative sip with a deeper one, and then with a third. In very fact, it had a distinctly calmative effect, speedily lifting him out of the fresh slough of dejection into which he had let himself topple.

But another moment more and he detected a strange unwelcome furriness coating his tongue, and it began to seem to him that beneath the superficial exuberance and openheartedness of the wine lay some less appetizing tinge of flavor, something almost alkaline that crept upward on his palate and negated the immediately pleasing effect of the initial taste. Then he noticed a heaviness of the mind overtaking him, and a weakness of the limbs, and it occurred to him, first, that they had been serving themselves out of one carboy and him out of another, and then, that he was unable to move, so that it became clear to him that the wine had been drugged. Fierce-eyed Malion Gainthrust stood directly before him, and he was speaking at last, declaiming a rhythmic chant which even in his drugged state Puillayne recognized as a simple binding spell that left him trussed and helpless.

Like any householder of some affluence, Puillayne had caused his manse to be protected by an assortment of defensive charms, which the magus of his family had assured him would defend him against many sorts of immical events. The most obvious was theft: there were treasures here that others might have reasons to crave. In addition, one must guard one’s house against fire, subterranean tremors, the fall of heavy stones from the sky, and other risks of the natural world. But, also, Puillayne was given to drunkenness, which could well lead to irresponsibility of behavior or mere clumsiness of movement, and he had bought himself a panoply of spells against the consequences of excessive intoxication.

In this moment of danger, it seemed to him that Citrathanda’s Punctilious Sentinel was the appropriate spirit to invoke, and in a dull thick-tongued way Puillayne began to recite the incantation. But over the years, his general indifference to jeopardy had led to incaution, and he had not taken the steps that were needful to maintain the potency of his guardian spirits, which had dimmed with time so that his spell had no effect. Nor would his household revenants be of the slightest use in this predicament. Their barely corporeal forms could exert no force against tangible life. Only his gardeners were incarnate beings, and they, even if they had been on the premises this late in the day, would have been unlikely to heed his call. Puillayne realized that he was altogether without protection now. Gently his guests, who now were his captors, were prodding him upward out of his couch. Kesztrel Tsaye said, “You will kindly accompany us, please, as we make our tour of your widely reputed treasury of priceless prizes.”

All capacity for resistance was gone from him. Though they had left him with the power of locomotion, his arms were bound by invisible but unbreakable withes, and his spirit itself was captive to their wishes. He could do no other than let himself be led through one hall after another of his museum, staggering a little under the effect of their wine, and when they asked him of the nature of this artifact or that, he had no choice but to tell them. Whatever object caught their fancy, they removed from its case, with Malion Gainthrust serving as the means by which it was carried back to the great central room and added to a growing heap of plunder.

Thus they selected the Crystal Pillow of Carsephone Zorn, within which scenes from the daily life of any of seven subworlds could be viewed at ease, and the brocaded underrobe of some forgotten monarch of the Pharials, whose virility was enhanced twentyfold by an hour’s wearing of it, and the Key of Sarpanigondar, a surgical tool by which any diseased organ of the body could be reached and healed without a breaching of the skin. They took also the Infinitely Replenishable Casket of Jade, once the utmost glory of the turban-wearing marauders of the frigid valleys of the Lesser Ghalur, and Sangaal’s Remarkable Phoenix, from whose feathers fluttered a constant shower of gold dust, and the Heptachromatic Carpet of Kypard Segung, and the carbuncle-encrusted casket that contained the Incense of the Emerald Sky, and many another extraordinary objects that had been part of Puillayne’s hoard of fabulosities for decade upon decade.

He watched in mounting chagrin. “So you have come all this way merely to rob me, then?”

“It is not so simple,” said Kesztrel Tsaye. “You must believe us when we say that we revere your poetry, and were primarily motivated to endure the difficulties of the journey by the hope of attaining your actual presence.”

“You choose an odd way to demonstrate your esteem for my art, then, for you would strip me of those things which I love even while claiming to express your regard for my work.”

“Does it matter who owns these things for the upcoming interim?” the bearded man asked. “In a short while, the concept of ownership itself will be a moot one. You have stressed that point frequently in your verse.”

There was a certain logic to that, Puillayne admitted. As the mound of loot grew, he attempted to assuage himself by bringing himself to accept Kesztrel Tsaye’s argument that the sun would soon enough reach its last moment, smothering Earth in unending darkness and burying him and all his possessions under an obdurate coating of ice twenty marasangs thick, so what significance was there in the fact that these thieves were denuding him today of these trifles? All would be lost tomorrow or the day after, whether or not he had ever admitted the caitiff trio to his door.

But that species of sophistry brought him no surcease. Realistic appraisal of the probabilities told him that the dying of the sun might yet be a thousand years away, or even more, for although its inevitability was assured, its imminence was not so certain. Though ultimately he would be bereft of everything, as would everyone else, including these three villains, Puillayne came now to the realization that, all other things being equal, he preferred to await the end of all things amidst the presence of his collected keepsakes rather than without them. In that moment, he resolved to adopt a defensive posture.

Therefore, he attempted once more to recite the Efficacious Sentinel of Citrathanda, emphasizing each syllable with a precision that he hoped might enhance the power of the spell. But his captors were so confident that there would be no result that they merely laughed as he spoke the verses, rather than making any effort to muffle his voice, and, in this, they were correct: as before, no guardian spirit came to his aid. Puillayne sensed that unless he found some more effective step to take, he was about to lose all that they had already selected, and, for all he knew, his life as well; and in that moment, facing the real possibility of personal extinction this very day, he understood quite clearly that his lifelong courtship of death had been merely a pose, that he was in no way actually prepared to take his leave of existence.

One possibility of saving himself remained.

“If you will set me free,” Puillayne said, pausing an instant or two to focus their attention, “I will locate and share with you the True Vintage of Erzuine Thale.”

The impact of that statement upon them was immediate and unmistakable. Their eyes brightened; their faces grew flushed and glossy; they exchanged excited glances of frank concupiscence.

Puillayne believed he understood this febrile response. They had been so overcome with an access of trivial greed, apparently, once they had had Puillayne in their power and knew themselves free to help themselves at will to the rich and varied contents of his halls, that they had forgotten for the moment that his manse contained not only such baubles as the Heptochromatic Carpet and the Infinitely Replenishable Casket, but also, hidden away somewhere in his enormous accumulation of rare wines, something vastly more desirable, the veritable wine of wines itself, the bringer of infinitely ecstatic fulfillment, the elixir of ineffable rapture, the True Vintage of Erzuine Thale. Now he had reminded them of it and all its delights; and now they craved it with an immediate and uncontrollable desire.

“A splendid suggestion,” said Unthan Vyorn, betraying by his thickness of voice the intensity of his craving. “Summon the wine from its place of hiding, and we will partake.”

“The bottle yields to no one’s beck,” Puillayne declared. “I must fetch it myself.”

“Fetch it, then.”

“You must first release me.”

“You are capable of walking, are you not? Lead us to the wine, and we will do the rest.”

“Impossible,” said Puillayne. “How do you think this famed wine has survived so long? It is protected by a network of highly serviceable spells, such as Thampyron’s Charm of Impartial Security, which insures that the flask will yield only to the volition of its inscribed owner, who at present is myself. If the flask senses that my volition is impaired, it will refuse to permit opening. Indeed, if it becomes aware that I am placed under extreme duress, the wine itself will be destroyed.”

“What do you request of us, then?”

“Free my arms. I will bring the bottle from its nest and open it for you, and you may partake of it, and I wish you much joy of it.”

“And then?”

“You will have had the rarest experience known to the soul of man, and I will have been cheated of the opportunity to give the world the epic poem that you claim so dearly to crave; and then, I hope, we will be quits, and you will leave me my little trinkets and take yourselves back to your dreary northern caves. Are we agreed?”

They looked at one another, coming quickly and wordlessly to an agreement, and Kesztrel Tsaye, with a grunt of assent, signalled to Malion Gainthrust to intone the counterspell. Puillayne felt the bonds that had embraced his arms melting away. He extended them in a lavish stretching gesture, flexed his fingers, looked expectantly at his captors.

“Now fetch the celebrated wine,” said Kesztrel Tsaye.

They accompanied him back through chamber after chamber until they reached the hall where his finest wines were stored. Puillayne made a great show of searching through rack after rack, muttering to himself, shaking his head. “I have hidden it very securely,” he reported after a time. “Not so much as a precaution against theft, you realize, but as a way of making it more difficult for me to seize upon it myself in a moment of drunken impulsiveness.”

“We understand,” Unthan Vyorn said. “But find it, if you please. We grow impatient.”

“Let me think. If I were hiding such a miraculous wine from myself, where would I put it? The Cabinet of Meritorious Theriacs? Hardly. The Cinnabar Vestibule? The Chrysochlorous Benefice? The Tabulature? The Trogonic Chamber?”

As he pondered, he could see their restiveness mounting from one instant to the next. They tapped their fingers against their thighs, they moved their feet from side to side, they ran their hands inside their garments as though weapons were hidden there. Unheeding, Puillayne continued to frown and mutter. But then he brightened. “Ah, yes, yes, of course!” And he crossed the room, threw open a low door in the wall at its farther side, reached into the dusty interior of a service aperture.

“Here,” he said jubilantly. “The True Vintage of Erzuine Thale!”

“This?” said Kesztrel Tsaye, with some skepticism.

The bottle Puillayne held forth to them was a gray tapering one, dustencrusted and unprepossessing, bearing only a single small label inscribed with barely legible runes in faint grayish ink. They crowded around like snorting basilisks inflamed with lust.

Each in turn puzzled over the writing; but none could decipher it.

“What language is that?” asked Unthan Vyorn.

“These are Nolwaynish runes,” answered Puillayne. “See, see, here is the name of the maker, the famed vintner Erzuine Thale, and here is the date of the wine’s manufacture, in a chronology that I fear will mean nothing to you, and this emblem here is the seal of the king of Gammelcore who was reigning at the time of the bottling.”

“You would not deceive us?” said Kesztrel Thale. “You would not fob some lesser wine off on us, taking advantage of our inability to read these scrawls?”

Puillayne laughed jovially. “Put all your suspicions aside! I will not conceal the fact that I bitterly resent the imposition you are enforcing on me here, but that does not mean I can shunt aside thirty generations of family honor. Surely you must know that on my father’s side I am the Eighteenth Maghada of Nalanda, and there is a geas upon me as hereditary leader of that sacred order that bans me from all acts of deceit. This is, I assure you, the True Vintage of Erzuine Thale, and nothing else. Stand a bit aside, if you will, so that I can open the flask without activating Thampyron’s Charm, for, may I remind you, any hint that I act under duress will destroy its contents. It would be a pity to have preserved this wine for so long a time only to have it become worthless vinegar in the moment of unsealing.”

“You act now of your own free will,” Unthan Vyorn said. “It was your choice to offer us this wine, nor was it done at our insistence.”

“This is true,” Puillayne responded. He set out four goblets and, contemplating the flask thoughtfully, spoke the words that would breach its seal.

“Three goblets will suffice,” said Kesztrel Tsaye.

“I am not to partake?

“If you do, it will leave that much less for us.”

“You are cruel indeed, depriving me even of a fourth share of this wine, which I obtained at such expense and after negotiations so prolonged I can scarcely bear to think of them. But so be it. I will have none. As you pointed out, what does it matter, or anything else, when the hour of everlasting night grows ineluctably near?”

He put one goblet aside and filled the other three. Malion Gainthrust was the first to seize his, clutching it with berserk intensity and gulping it to its depths in a single crazed ingurgitation. Instantly, his strange chilly eyes grew bright as blazing coals. The other two men drank more judiciously, frowning a bit at the first sip as though they had expected some more immediate ebullition, sipping again, frowning again, now trembling. Puillayne refilled the goblets. “Drink deep,” he abjured them. “How I envy you this ecstasy of ecstasies!”

Malion Gainthrust now fell to the floor, thrashing about oddly, and, a moment later, Kesztrel Tsaye did the same, toppling like a felled tree and slapping his hands against the tiles as though to indicate some extreme inward spasm. Long-legged Unthan Vyorn, suddenly looking deathly pale, swayed erratically, clutched at his throat, and gasped, “But this is some poison, is it not? By the Thodiarch, you have betrayed us!”

“Indeed,” said Puillayne blandly, as Unthan Vyorn joined his writhing fellows on the floor. “I have given you not the True Vintage of Erzuine Thale, but the Efficacious Solvent of Gibrak Lahinne. The strictures of honor placed upon me in my capacity as Eighteenth Maghada of Nalanda do not extend to a requirement that I ignore the need for self-defense. Already, I believe, the bony frame of your bodies has begun to dissolve. Your internal organs must also be under attack. You will shortly lose consciousness, I suspect, which will spare you from whatever agonies you may at the moment be experiencing. But do you wonder that I took so harsh a step? You thought I was a helpless idle fool, and quite likely that scornful assessment was correct up until this hour, but by entering my sanctum and attempting to part me from the things I hold precious, you awakened me from my detachment and restored me to the love of life that had long ago fled from me. No longer did the impending doom of the world enfold me in paralysis. Indeed, I chose to take action against your depredations, and so—”

But he realized that there was no reason for further statements. His visitors had been reduced to puddles of yellow slime, leaving just their caps and boots and other garments, which he would add to his collection of memorabilia. The rest required only the services of his corps of revenants to remove, and then he was able to proceed with a clear mind to the remaining enterprises of a normal afternoon.

“But will you not now at last permit yourself to enjoy the True Vintage?” Gimbiter Soleptan asked him two nights later, when he and several other of Puillayne’s closest friends had gathered in a tent of sky-blue silk in the garden of the poet’s manse for a celebratory dinner. The intoxicating scent of the calavindra blossoms was in the air, and the pungent odor of sweet nargiise. “They might so easily have deprived you of it, and who knows but some subsequent miscreant might have more success? Best to drink it now, say I, and have the enjoyment of it before that is made impossible for you. Yes, drink it now!”

“Not quite yet,” said Puillayne in a steadfast tone. “I understand the burden of your thought: seize the moment, guarantee the consumption while I can. By that reasoning, I should have guzzled it the instant those scoundrels had fallen. But you must remember that I have reserved a higher use for that wine. And the time for that use has not yet arrived.”

“Yes,” said Immiter of Glosz, a white-haired sage who was of all the members of Puillayne’s circle the closest student of his work. “The great epic that you propose to indite in the hour of the sun’s end—”

“Yes. And I must have the unbroached True Vintage to spur my hand, when that hour comes. Meanwhile, though, there are many wines here of not quite so notable a puissance that are worthy of our attention, and I propose that we ingest more than a few flasks this evening.” Puillayne gestured broadly at the array of wines he had previously set out, and beckoned to his friends to help themselves. “And as you drink,” he said, drawing from his brocaded sleeve a scrap of parchment, “I offer you the verses of this afternoon.”

The night is coming, but what of that?

Do I not glow with pleasure still, and glow, and glow?

There is no darkness, there is no misery

So long as my flask is near!

The flower-picking maidens sing their lovely song by the jade pavilion.

The winged red khotemnas flutter brightly in the trees.

I laugh and lift my glass and drain it to the dregs.

O golden wine! O glorious day!

Surely we are still only in the springtime of our winter

And I know that death is merely a dream

When I have my flask!

AFTERWORD:

I BOUGHT the first edition of The Dying Earth late in 1950, and finding it was no easy matter, either, because the short-lived paperback house that brought it out published it in virtual secrecy. I read it and loved it, and I’ve been re-reading it with increasing pleasure in the succeeding decades and now and then writing essays about its many excellences, but it never occurred to me in all that time that I would have the privilege of writing a story of my own using the setting and tone of the Vance originals. But now I have; and it was with great reluctance that I got to its final page and had to usher myself out of that rare and wondrous world. Gladly would I have remained for another three or four sequences, but for the troublesome little fact that the world of The Dying Earth belongs to someone else. What a delight it was to share it, if only for a little while.

—Robert Silverberg

MATTHEW HUGHES Grolion of Almery (#ulink_24ca1c66-f612-5d7f-92f0-f7ed6667425d)

ALLOWING A stranger to take refuge from the dangers of a dark and demon-haunted night in your house always involves a certain amount of risk for both stranger and householder. Particularly on the Dying Earth, where nothing is as it seems—including the householder and the stranger!

Matthew Hughes was born in Liverpool, England, but spent most of his adult life in Canada before moving back to England last year. He’s worked as a journalist, as a staff speechwriter for the Canadian Ministers of Justice and Environment, and as a freelance corporate and political speechwriter in British Columbia before settling down to write fiction full-time. Clearly strongly influenced by Vance, as an author Hughes has made his reputation detailing the adventures of rogues like Henghis Hapthorn, Guth Bandar, and Luff Imbry who live in the era just before that of The Dying Earth, in a series of popular stories and novels that include Fools Errant, Fool Me Twice, Black Brillion, and Majestrum, with his stories being collected in The Gist Hunter and Other Stories. His most recent books are the novels Hespira, The Spiral Labyrinth, Template, and The Commons.

Grolion of Almery MATTHEW HUGHES (#ulink_24ca1c66-f612-5d7f-92f0-f7ed6667425d)

When next I found a place to insert myself, I discovered the resident in the manse’s foyer, in conversation with a traveler. Keeping myself out of his sightlines, I flew to a spot high in a corner where a roof beam passed through the stone of the outer wall, and settled myself to watch and listen. The resident received almost no visitors—only the invigilant, he of the prodigious belly and eight varieties of scowl, and the steagle knife.

I rarely bothered to attend when the invigilant visited, conserving my energies for whenever my opportunity should come. But this stranger was unusual. He moved animatedly about the room in a peculiar bent-kneed, splay-footed lope, frequently twitching aside the curtain of the window beside the door to peer into the darkness, then checking that the beam that barred the portal was well seated.

“The creature cannot enter,” the resident said. “Doorstep and lintel, indeed the entire house and walled garden, are charged with Phandaal’s Discriminating Boundary. Do you know the spell?”

The stranger’s tone was offhand. “I am familiar with the variant used in Almery. It may be different here.”

“It keeps out what must be kept out; your pursuer’s first footfall across the threshold would draw an agonizing penalty.”

“Does the lurker know this?” said the visitor, peering again out the window.

The resident joined him. “Look,” he said, “see how its nostrils flare, dark against the paleness of its countenance. It scents the magic and hangs back.”

“But not far back.” The dark thatch of the stranger’s hair, which drew down to a point low on his forehead, moved as his scalp twitched in response to the almost constant motion of his features. “It pursued me avidly as I neared the village, growing bolder as the sun sank behind the hills. If you had not opened…”

“You are safe now,” said the resident. “Eventually, the ghoul will go to seek other prey.” He invited the man into the parlor and bade him sit by the fire. I fluttered after them and found a spot on a high shelf. “Have you dined?”

“Only forest foods plucked along the way,” was the man’s answer as he took the offered chair. But though he no longer strode about the room, his eyes went hither and thither, rifling the many shelves and glass-fronted cupboards, as if he cataloged their contents, assigning each item a value and closely calculating the sum of them all.

“I have a stew of morels grown in the inner garden, along with the remnants of yesterday’s steagle,” said the resident. “There is also half a loaf of bannock and a small keg of brown ale.”

The stranger’s pointed chin lifted in a display of fortitude. “We will make the best of it.”

They had apparently exchanged names before I had arrived, for when they were seated with bowls of stew upon their knees and spoons in their hands, the resident said, “So, Grolion, what is your tale?”

The foxfaced fellow arranged his features into an image of nobility beset by unmerited trials. “I am heir to a title and lands in Almery, though I am temporarily despoiled of my inheritance by plotters and schemers. I travel the world, biding my moment, until I return to set matters forcefully aright.”

The resident said, “I have heard it argued that the world as it is now arranged must be the right order of things, for a competent Creator would not allow disequilibrium.”

Grolion found the concept jejeune. “My view is that the world is an arena in which men of deeds and courage drive the flow of events.”

“And you are such?”

“I am,” said the stranger, cramming a lump of steagle into his mouth. He tasted it then began chewing with eye-squinting zest.