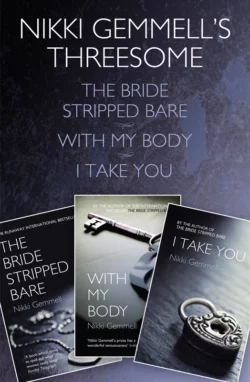

Nikki Gemmell’s Threesome: The Bride Stripped Bare, With the Body, I Take You

Nikki Gemmell

For fans of ‘Fifty Shades of Grey’, discover the author who dares to spell out what women really want; succumb to Nikki Gemmell’s smartly seductive Threesome.This sensational ebook collection includes Nikki’s latest book, ‘I Take You’.‘The Bride Stripped Bare’On honeymoon, a young wife makes a shocking discovery that will free her to explore her most dangerous desires.‘With My Body’A mother escapes from married life in overwhelmingly passionate memories of her first love.‘I Take You’A woman consents to submit to her husband’s every desire, but can she bear to remain under lock and key when true intimacy beckons?

Nikki Gemmell’s Threesome

The Bride Stripped Bare

With My Body

I Take You

Nikki Gemmell

Table of Contents

Title Page (#u77c3a4ff-4d49-529b-9021-45f391ccdcc2)

The Bride Stripped Bare (#uaaaf2ea0-de4c-5545-b3a2-89ce72cff5ca)

With My Body (#u382bd74f-f152-5574-82b3-5413b4e0cae9)

I Take You (#u0c988db5-82e3-5da5-a781-5dcb06747f84)

About the Author

Also by Nikki Gemmell

Copyright

About the Publisher

The Bride Stripped Bare (#ulink_5685a801-9322-585b-99ef-52f5e83dcf29)

The Bride Stripped Bare

Nikki Gemmell

Dedication (#ulink_02c849c4-93b0-572d-9a1f-48a4193339eb)

For my husband. For every husband.

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Dear sir (#ulink_7fead6a8-a462-5f4b-b38c-a0a5c8d128b9)

I

Lesson 1

Lesson 2

Lesson 3

Lesson 4

Lesson 5

Lesson 6

Lesson 7

Lesson 8

Lesson 9

Lesson 10

Lesson 11

Lesson 12

Lesson 13

Lesson 14

Lesson 15

Lesson 16

Lesson 17

Lesson 18

Lesson 19

Lesson 20

Lesson 21

Lesson 22

Lesson 23

Lesson 24

Lesson 25

Lesson 26

II

Lesson 27

Lesson 28

Lesson 29

Lesson 30

Lesson 31

Lesson 32

Lesson 33

Lesson 34

Lesson 35

Lesson 36

Lesson 37

Lesson 38

Lesson 39

Lesson 40

Lesson 41

Lesson 42

Lesson 43

Lesson 44

Lesson 45

Lesson 46

Lesson 47

Lesson 48

Lesson 49

Lesson 50

Lesson 51

Lesson 52

Lesson 53

Lesson 54

Lesson 55

Lesson 56

Lesson 57

Lesson 58

Lesson 59

Lesson 60

Lesson 61

Lesson 62

Lesson 63

Lesson 64

Lesson 65

Lesson 66

Lesson 67

Lesson 68

Lesson 69

Lesson 70

Lesson 71

Lesson 72

Lesson 73

Lesson 74

Lesson 75

Lesson 76

Lesson 77

III

Lesson 78

Lesson 79

Lesson 80

Lesson 81

Lesson 82

Lesson 83

Lesson 84

Lesson 85

Lesson 86

Lesson 87

Lesson 88

Lesson 89

Lesson 90

Lesson 91

Lesson 92

Lesson 93

Lesson 94

Lesson 95

Lesson 96

Lesson 97

Lesson 98

Lesson 99

Lesson 100

Lesson 101

Lesson 102

Lesson 103

Lesson 104

Lesson 105

Lesson 106

Lesson 107

Lesson 108

Lesson 109

Lesson 110

Lesson 111

Lesson 112

Lesson 113

Lesson 114

Lesson 115

Lesson 116

Lesson 117

Lesson 118

Lesson 119

Lesson 120

Lesson 121

Lesson 122

Lesson 123

Lesson 124

Lesson 125

Lesson 126

Lesson 127

Lesson 128

Lesson 129

Lesson 130

Lesson 131

Lesson 132

Lesson 133

Lesson 134

Lesson 135

Lesson 136

Lesson 137

Lesson 138, the last

Postscript (#ulink_63fbb246-e7f6-5686-869f-e1781ce8ecbc)

Author’s Note

Dear sir (#ulink_51b5e48a-4c6e-576a-9f39-0cbe2d0e9ad6),

I am taking the liberty of sending you this manuscript, which I am hoping may interest you.

It was written by my daughter. Twelve months ago she vanished. Her car was found at the top of a cliff in the south of England, yet her body was never recovered. Despite extensive questioning of several people close to her the police concluded it was a case of suicide and closed their file. Others speculate that she may have staged her disappearance. I’m not sure about either scenario and the uncertainty of it all, I must admit, has consumed my life.

She was completing a book at the time of her disappearance. It was in her laptop which the police returned to me. I’m the only person, as far as I know, whom she told about what she’d been working on. It’s about a married woman’s secret life, and my daughter wished to remain anonymous because she wanted to write with complete candour; she feared she’d only end up censoring herself if her name was attached. She also wanted to protect the people around her, and herself.

I read through her manuscript in the hope of finding a reason for her vanishing, and I felt her life open up before me like a flower. How much I didn’t know. How much I didn’t want to know. She was a stranger to me in many ways and yet the person closest to me.

My first instinct, I must admit, was to just delete her book and forget about it, but it’s been a long time since her going, and even though I’ve never stopped hoping it will be her on the end of the line when the phone rings, I feel, now, that I owe it to her to help if I can and find a publisher for her work. I believe it’s what she wanted, very much. Her happiness is, ultimately, all I ever wanted for her.

So, here is The Bride Stripped Bare. Thank you for your time.

I (#ulink_d676508c-ffaa-55a1-840e-397310ce4277)

I have a feeling that inside you somewhere, there’s somebody nobody knows about.

Alfred Hitchcock and Thornton Wilder,

Shadow of a Doubt

Lesson 1 (#ulink_68a5f456-7720-53e2-b175-1a309a376f6f)

honesty is of the utmost importance

Your husband doesn’t know you’re writing this. It’s quite easy to write it under his nose. Just as easy, perhaps, as sleeping with other people. But no one will ever know who you are, or what you’ve done, for you’ve always been seen as the good wife.

Lesson 2 (#ulink_96fff8ff-ff00-5384-a7ff-42842e869706)

cold water stimulates, strengthens and braces the nerves

A honeymoon. A foreign land.

There you are, succumbing to the sexual ritual and remembering the day as a seven-year-old when you discovered water. You’d never been in a swimming pool before; there were none where you were growing up. You’re remembering a summer holiday and a swimming pool with the water inching up your belly as you stepped forward gingerly and the slow creep of the cold and the breath collected in the knot of your stomach and your mother always there ahead of you, smiling and coaxing and holding out her hands and stepping back and back. Then suddenly, pop, you’re floating and the water’s holding your belly and legs like sinews of rope, it’s muscular and balming and silky and the memory’s as potent as a first kiss.

As for the first time you fucked, well, you remember the sound, as his fingers readied you between your legs, not much else. Not even a name now.

Lesson 3 (#ulink_3258318a-4f22-5467-a2c1-23746c47264d)

making a comfortable bed is a very important part of household work

In the night air of Marrakech, on your belated honeymoon, the first scrum of morning birds sounds like fat spitting and crackling in a kitchen. It’s still dark but the birds have taken over from the frogs as crisply as if a conductor’s lowered his baton. The call to prayers has pulled you awake and you can’t fall back into sleep, you want to fling the french doors wide, as wide as they’ll go, and inhale the strange desert dawn. But your husband, Cole, will wake and complain if you do.

So. You lay your hand on the jut of his hip and breathe in his sleeping, the sour, sweet smell of it, and smile softly in the dark. The tip of your nose nuzzles his scent on the back of his neck.

You’ve never loved anyone more in your life.

You slip on to the balcony. It’s hot, twenty-eight degrees at least. A wondrous child-smile greets a great spill of stars, for the vast orange glow from London’s lights means you never see stars at home, scarcely know when there’s a full moon. The night flowers exhale their bloom, bougainvillaea and hibiscus and magnolia are still and shadowy in the night. You feel fat with content. Cole calls out, plaintive, and you slip back inside and his arm wings your body and clamps you tight.

Your feet manoeuvre free of the sheet’s smother and dangle off the edge of the bed, as they always do, finding the coolness and the air.

Lesson 4 (#ulink_7a5c7dc5-c562-5134-915e-9a9d8a936680)

very few people have many friends; as the word is generally used, it has no meaning at all

On the day before you leave for Marrakech Mrs Theodora White tells you she has no passion in her life, for anything. It’s such a shock to hear, but she dismisses your concern with a smile and a flick of her hand. She picks a sliver of tobacco off her tongue and throws back her head to gulp the last of her flat white. She was born thirty-five whereas you haven’t gained definition yet, haven’t hardened into adulthood. You’re also in your thirties but still stamp through puddles and sing off-key too much, as if tucked inside you is a little girl who refuses to die.

The only thing I’ve ever had a passion for was Jesus, Theo tells you. When I was eleven. It was something to do with the hips.

She was expelled from your convent school because the Mother Superior decided she had more influence over the students than the nuns did. She has many stories like this. You do not. She’s called Diz by the people closest to her. She’s always rolling her cigarettes from a battered silver case and this only adds to her charm, as does her air of being constantly in heat. Your friend is lush, ripe, her body a peachy size fourteen. She’s one of those women who look like they enjoy an abundance of everything, food, fresh air, sex, laughter, love. When alongside Theo you feel pale, like a leaf left too long in the water, bleached of colour and life.

But you don’t envy her for you know too much about her. She’s your oldest friend in the world, you’ve loved her since you were thirteen. You’re not sure why it’s so disturbing to hear she has no passion in her; perhaps it’s because your life, in contrast, on the cusp of your honeymoon, seems bathed in love. As you walk home from the cafe you smile out loud at that thought, you can’t help it, you smile widely as you walk down the street.

Lesson 5 (#ulink_35d0d194-6182-59bb-8bbd-b3eb2854190e)

it is absolutely necessary to wash the armpits and hips every day

You’ve laughed with Theo that your husband always sleeps with his T-shirt and boxer shorts on, even when it’s hot. That he doesn’t appreciate the sweetness of skin to skin, the softness of it and the smell, the warmth. Just the sight of a man’s chest can make you wet. You’d never say an expression like that to him, makes me wet. You would to Theo. Cole would be horrified at how much she knows.

You love placing your palm on Cole’s chest when you’re lying in bed, curving your torso around the crescent of his back, the jigsaw fit of it. You love the smell of him when he hasn’t washed, especially the softness under his arms. If he knew, he’d describe it as unseemly. Sometimes in bed Cole doesn’t allow your hand to stay on his chest, he brusques it away. Sometimes he lets your hand rest there. Sometimes he clamps your hand like it’s caught in a trap and when you drag it away he clutches it tight and it becomes a game to disentangle yourself.

But only you’re giggling, in the close dark.

Lesson 6 (#ulink_7dc3622f-7ff1-5d2d-a953-e3dca61029e6)

girls can never be too thoughtful

Why are you putting on your socks, you ask.

Because I’m going back to the room, Lovely.

But we’ve just got here, Donkey. Your swimmers are still wet.

I know, but there’s a very important meeting in front of the telly. Are you coming?

No, I’ll stay a bit longer.

You feel guilty saying no for Cole needs you a lot and he’s loud with his want, it’s almost a petulance, like a boy’s. But you can feel your skin absorbing this hard Moroccan light like the desert does rain, can feel it uncurling something within you. Here the light bashes you; in England, it licks you. Cole’s skin and eyes recoil from it; his skin is very pale, almost translucent; he’s away, inside, a lot. Not only on holidays but in London too. He sequesters himself by habit. At work, until late, or in front of the television, or in the bathroom. He can stay on the toilet for three-quarters of an hour or more, if you sit next to him on the couch he’ll make his way to the armchair without even realising what he’s doing, if you put your hand on his groin in bed he’ll shrug it away. He sleeps with the curve of his back to you more often than not.

Yet even when he’s away he needs you nearby: he’s told you that you’re his life. You love the ferocity in his need, to be wanted so much. Cole is the only man you’re attracted to whom you can talk to without a fear of silence, like an empty highway, right through the middle of the conversation. Or of saying something ridiculous and telling, or of your lip trembling, or of blushing. Your body stays obedient around Cole, you’re in control, you can relax. It’s one of the reasons why you married him. That you’re comfortable with him, that you don’t have to act too much, you can be, almost, yourself. No one else is allowed so close.

Lesson 7 (#ulink_9ffab8d9-f012-5a82-b12e-4c162e79194a)

dance away with all your might

Your big toe’s kissed, indulgently, when you throw back your arms like a diva on the sunlounger and declare you’ll be staying by the pool a little longer. Neither Cole nor yourself has seen anything, yet, of the new city you’re in, even though you’ve been here for four days. Theo would berate you for this but marriage has made you soft, dulled your curiosity. The crush of robed and veiled people at the airport, the mountains of luggage and squealing children and machine-guns on guards were all a little overwhelming, so both Cole and yourself are content to stay wrapped within the hotel for a while. It’s like the one in the movie The Shining, with wide, deco corridors and a surreally spare lobby and the regret of some long-ago lost decadence. A bastion of French colonialism that’s now frequented by wealthy Europeans, but there are not enough of them to plump out its space. There are no Muslims. Perhaps they find it too ridiculous, or unwelcoming, or odd, but there’s no one to ask.

You would’ve sought the answers once, you shone with curiosity once. Now you’re almost too languid to care, for you’re distracted, deliciously so. You sit on the edge of the pool and dawdle your fingertips in its coolness and remember something from the day-old Times, that the urge to think rarely strikes the contented. You smile—so what?—and wave over a pool waiter for another Bellini. How you love them. You’ve never allowed yourself the luxury of laziness, or four Bellinis in a row before.

A donkey pulls a cart of clippings up a rose-bowered path of the hotel’s gardens. A man flicks a whip lazily over the animal’s back. It’s something of this land at least. You must photograph it.

Lesson 8 (#ulink_3b433eba-6ae8-51e5-92e2-c74972c3e6aa)

it is a wife’s duty to make her husband’s home happy

Midnight is thick with heat and humming with stillness before the assault of the frogs and the birds and your eyes are shut but you can sense Cole’s gaze, can feel his greed and there’s a tightness in your throat. Your relationship works delightfully, easily, in so many ways, except for the sex.

But that is not what you married Cole for.

A tongue hits your eye, slug-wet and heavy. Your husband strips away the recalcitrant sheet wound about your legs and nudges, insistently, his knee between your thighs. He must make love on his terms, which isn’t often. You usually make love in the mornings to take advantage of his hardness upon waking. Cole’s penis often doesn’t feel hard enough, as if it’s thinking of something else. He doesn’t come very often. Both of you usually give up before he has and it’s always with relief on your part. You wonder if Cole has a condition that causes him to take so long to come, or if he’s undersexed, or just tired. Like you have been, a lot.

As Cole is on top of you on this wide hotel bed you’re looking at the numbers of the clock radio by the bed flicking over their minutes and you’re thinking of Marilyn Monroe who said I don’t think I do it properly – you read it in a newspaper once with astonishment and relief: so, someone else, and what a someone else. You’re not sure if Cole does it properly, you don’t know what properly is. Theo would, for she is a sex therapist with a discreet Knightsbridge office and a Sunday magazine column. You suspect she finds you both innocent and ridiculous and sweet. Cole and you have never done any of that making love twice in a row or knocking over lamps or pulling each other’s hair. When you do make love you could describe each other as tidy.

The numbers on the clock radio are taking too long to flip over as you lie on the bed, with Cole on top of you. Something has slid away, deep in you. You don’t make love often; you’ve read articles in women’s magazines about how frequently most couples do and it always seems such a lot. But no one’s completely honest about sex.

Thirteen minutes past midnight. Cole has come. This is rare. He wipes the cum across your breasts and your cheeks and dabs it on your forehead, as if he’s blooding you. He’s pleased. You’re pleased. Perhaps it worked this time. Cole turns on the bedside lamp to assess the soakage on the sheets and any items of clothing; he always does this, he wants it cleaned up as quickly as possible, he hates mess.

You push his face towards you. He’s surprised at the boldness, he wants his face back but you hold him firm for you’re remembering walking down the aisle and looking ahead to him and your heart swelling with love like an old dried sponge that’s been dropped into a bath. When your husband enfolds you in his arms it’s a haven, a harbour, to rest from all the toss of the world. It’s what you’ve always wanted, you have to admit, the place of refuge, the cliché.

Lesson 9 (#ulink_18387483-1815-520f-85d5-5a33588e8201)

the prevention of waste a duty

Before you found Cole you hadn’t slept with a man for four years. It’s hard, you’d say to Theo, it’s really hard. There were the endless birthday nights and New Year’s Eves of just you in your bed and no one else. There was the welling up at weddings, the glittery eye-prick, when all the couples would get up to dance. Sometimes it felt like your heart was crazed with cracks like your grandmother’s old saucers. Sometimes the sight of a Saturday afternoon couple laughing in a park would splinter it completely. Young couples who’d been together for many years were intriguing, hateful, remote. What was their secret? You’d reached the stage where you couldn’t imagine ever being in a loving partnership.

Theo had warned you that any person who lives by themselves for more than three years becomes strange and selfish and has to be hauled back into the world. She said she had to intervene. You told her no, you were beyond help, you’d convinced yourself of this. All your life people had been leaving: you were a child of divorced parents and you never grew up with the expectation that someone would look after you, and stay.

But then Cole McCain.

An old acquaintance from university, a friend, just that. One summer you were house-sitting in Edinburgh during the festival and he asked if he could come to stay; there were some shows he wanted to catch. You remember marching him to his room, a little girl’s, with its narrow bed and pink patchwork quilt. You remember his dubious look.

I think you better sleep in the big bed with me, you said.

It was meant to be two friends bunking down for the sake of convenience. You both had your pyjamas on, you made sure of that. But then his sudden fingers on your skin were like a trickle of water on a sweltering summer’s day. A strangeness shot through you, you turned to him, kissed. Cole stripped off his pyjamas, quick, and then yours were off too and something took over you, you were gone. Within a week you were both rolling up in the sheets and falling off the bed in a giggly cocoon. Within two years you were married.

I’ve known for years, you wally, said Theo in gleeful hindsight, it was always so obvious.

I never saw it.

It had taken you a long time to wake up to some sense. You used to sleep with men you were uncomfortable with in an attempt to make yourself comfortable with them; you married the one you forget yourself with.

But there was a moment of invisibility when you tried on the wedding dress, as if you were disappearing into that swathe of ivory and tulle, being wiped away. It was only fleeting and it was worth it, of course, not to have the prickle behind the eyes of those laughing Saturday afternoon couples again, the heart-crack.

Lesson 10 (#ulink_7b5299dd-bdc4-5d57-b5f1-3a30aaa4a00a)

garments worn next to the skin are those which require frequent washing

Men you have slept with. What you remember the most:

The one who loved women.

The one who never took off his socks.

The one whose hands were so big they seemed to be in three places at once.

The one whose touch hummed, who seemed to know exactly what he was doing and stood out because of that. He seemed only to derive pleasure from the experience if you were, whereas none of the others seemed too fussed. He asked what your fantasies were but you didn’t have the courage to speak out. Back then, you’d never have the courage for that.

The one who sent you a polaroid of his very big cock.

(#ulink_af0b6d1d-e046-557c-9fda-4e251d37a7cf) But size means little to you, you don’t know why they go on about it. You much prefer a comfortable fit than a penis that’s too big; you don’t want to feel you’re being split apart.

The one who’d say take me as he came and groaned like he was doing a big shit.

The one who tickled you behind your knees and licked you on the face, who forced you to swallow his cum and rubbed it through your hair; who was aroused by all the things you didn’t like.

The one who said yes, when you asked him to marry you, half joking, half not, on a February the twenty-ninth. You’re embarrassed you had to ask Cole McCain. You wish he’d never mention it, but he does, in a teasing way, a lot.

(#ulink_85471880-7452-50c7-a1bc-a1cdf8ebe336)You’re more than happy to write the word cock; saying it aloud, however, is another matter. It even feels a little odd to say vagina but you’re not sure what else to use. You hate pussy, you don’t know any woman who says it, and as for cunt, you always think it’s used by men who don’t like women very much. You want some words that women have colonised for themselves; maybe they exist but you haven’t heard them yet. You can’t say down there for the rest of your life.

Lesson 11 (#ulink_baa54f86-3b05-56db-9e44-39a4214c2c1a)

a sacred and delicate reticence should always enwrap the pure and modest woman

Early morning.

A bird flaps into the room and you wake, panicked at the flittering above your head and run to the bathroom and slam the door, begging Cole to do something, quick. The bird’s swiftly gone. It hasn’t crashed wildly into mirrors or windows. You couldn’t bear that—you witnessed it once as a child, the droppings out of fright, the too-bright blood, the crazed thump, the shrill eye.

But now there’s just quiet hovering in the room. You step into it from the bathroom and kiss Cole on the tip of his nose. He envelopes you in his arms with a great calm of ownership and laughs: he likes you vulnerable. And to teach you, to introduce you to new things. You didn’t look closely at a penis until you were married, didn’t know what a circumcised one looked like. You wonder, now, how you could’ve had the partners you’ve had and never really looked. You always wanted the lights off quick because you never liked your body enough, and dived under the sheets, and felt it was rude to study a man’s anatomy too intently: you favoured eye contact and touch. Cole forced you to look, right at the start, he taught you to get close. He likes to direct your life, to guide it.

You let him think he is.

Lesson 12 (#ulink_d3b6f2de-adc7-540c-83d1-53dcdefbbb32)

it is our greatest happiness to be unselfish

Cole fell asleep inside you once. He laughs at the memory, finds it erotic and silly and comforting. The morning after, to soothe your indignation, he’d said that falling asleep inside a woman was a sign of true love.

What? Shaking your head as if rattling out a fly.

It means that the man’s truly comfortable with the woman, so comfortable that he can fall asleep in the process of making love to her. I could never do that to anyone else. Think yourself honoured, Lovely.

Hmm, you’d replied.

You love Cole in a way you haven’t loved before. Calmly. It glows like a candle rather than glitters. You love him even when he falls asleep in the process of making love to you. You’d never loved calmly before, in your twenties. That was the time of greedy love, full of exhilaration and terror, and when you said I love you you always felt stripped; there was no sense, ever, of love as a rescue. Sometimes, now, you wonder what happened to the intensity of your youth, when everything seemed so vivid and desperate and bright. Sometimes you imagine a varnisher’s hand whipping over the quietness of your life now and flooding it with brightness, combusting it, in a way, with light.

But Cole. When he enfolds you in his arm you feel his love running as quiet and strong and deep as an underground river right through you. He stills your agitation in the way a visit to Choral Evensong does, or a long swim after work. The bond between you seems so clear-headed: the marriage is not perfect, by any means, but you’re old enough now to know you cannot demand perfection from the gift of love. It’s a lot more than most people have. Like Theo.

Your dear, restless, vivid-hearted friend. Sometimes you feel a sharp envy at the sensuality of her home, all candles and wood and stone, her fluid working hours, weekly massages, Kelly bags. But you remind yourself that she isn’t happy and probably never will be and it’s a comfort, that. For no matter how much Theo achieves and acquires and out-dazzles everyone else, she never seems content. She’s taught you that people who shine more lavishly than everyone else seem to be penalised by discontent, as if they’re being punished for craving a brighter life. I’ve been knocked down so many times I can’t remember the number plates, she said once.

Many people are afraid of Theo but you’ve never been, perhaps that’s why you’re so close. All the noise of her personality is a mask and when it slips off, on the rare occasion, the vulnerability riddled through her is always a shock.

Lesson 13 (#ulink_3bdbd20e-2b17-5fcb-9380-10748dbe8471)

it cannot be rational enjoyment to go where you would not like to have your truest and best friend go with you

Hold my hand, Cole says as he steers you through the twilight crush of Marrakech. Neither of you knows the pedestrian etiquette of this city; the cars are coming in all directions, the dusky streets teem like rush hour in New York but everything’s faster, cheekier, more reckless; exhilarating, you think. Mopeds and tourist coaches and donkeys and carts stop and start and weave and cut each other off without, it seems, any rules and the scrum of people funnels you into the great sprawling square at the city’s heart, Djemma El Fna, and you lift your head to the low ochre-coloured buildings around you and break from Cole’s grasp and swirl, gulping the sights, for you feel as if all of life’s in this place. There are snake-charmers with arms draped by writhing snake necklaces, wizened storytellers ringed by attentive men, water sellers with belts of brass cups like ropes of ammunition, veiled women offering fortunes, jewellery, hennaed hands. It’s a movie set of the glorious, the bizarre, the deeply kitsch.

Diz would love all this, you laugh.

Thank God you didn’t bring her.

You’d almost invited her on the spot when she said she was so low. You wanted her to join you just for a couple of days, as a treat: it’s her birthday in three days, June the first. But you knew you’d have to check with Cole first and he wouldn’t stand for it, of course.

She’s weird, he says of her.

You say that about all my friends.

She’s weirder than the rest.

You can’t argue with that. Theo takes the train to Paris just for a haircut. Has a tattoo of a gardenia below her pubic line. Can’t poach an egg. Never watches television. Gets her favourite flowers delivered to herself every Monday and Friday: iceberg roses, November lilies, exquisite gardenia knots. Is married to a man called Tomas, twenty-four years her senior, whom she’s rarely made love to. She has a condition.

What, you’d asked, when she first told you.

Vaginismus. It sounds vile, doesn’t it? Like something you’d pick up in Amsterdam. It means that when anyone tries to fuck me the muscles around my vagina go into spasms. It’s excruciatingly painful.

Theo, darling Theo, of all people. You wrapped her in a hug, your face crumpled, you began to cry.

Hey, it’s OK, she laughed, it’s OK. It’s actually been rather fun.

And she leant back and smiled her trademark grin, one side up, one side down. Took out her little silver case. Lit a cigarette. Said that she’d decided to investigate the whole situation, a woman’s pleasure, and it was so deliriously consuming that it eventually slipped into being a job. Said that most women never climaxed from vaginal penetration: all the fun was in the clit. You’d blushed back then, at hearing the bluntness of that word, there were some things you couldn’t help.

I can’t tell you how many clients get absolutely no pleasure whatsoever out of bog-standard penetration, she said, punctuating her words with savage little taps that made the cutlery jump. We just don’t know how to please ourselves enough. We’ll never learn. We’re still too intent on the man’s pleasure at the expense of our own.

You weren’t entirely comfortable with this talk, it was a little close to the bone. You wanted to know more of her condition, for it was a strange relief to hear that your arrestingly sensual friend also had stumbling blocks over sex: so, Theo was human, too.

Did you get some help, for the vagi, vagis—

Mm, I did. It involved a horrible thing called a dilator.

Did it work?

Well, yes, but when I finally had the sex I’d been waiting for it was such a let-down. It’s so dull compared with everything else. Why didn’t anyone tell me this?

Theo’s wonderful laugh curdled from deep in her belly but there was no joy in her eyes. Her marriage to Tomas was so odd, you couldn’t figure it out. He had other relationships with men as well as women and she had relationships with women as well as men, that was their life. And yet they stayed together. I don’t have any passion in my life, for anything. Not for her husband, whom she says she’s too clever to love. Nor for London, the city of fractious energy you both fled to as teenagers from the same boarding school, almost twenty years ago. Nor for her job, for she says she’s been doing it so long that the stories are now all the same, there aren’t many new plots in people’s lives and she’s found, lately, she’s switching off.

You suspect you attract extreme people like her because you’re so stable, as is Cole. She described the two of you once as eerily content and for some this means unforgivably beige but for others you’re an anchor, always there if needed, even on Sunday evenings, and birthdays, and Christmas Day.

Theo and you have shared your lives since the age of thirteen; swapping Arabian stud magazines for the pictures of the horses, camping overnight for tickets to Duran Duran, devouring books in tandem, from Little House on the Prairie to The Thorn Birds and Story of 0. Having your first cigarette together and the last shower you’ve ever shared with a girl. Standing to the left of each other at wedding altars, knowing you’ll be godmothers to each other’s children.

You met in the same class at a minor boarding school in Hampshire, a place where mediocrity was encouraged. You were not meant to be clever, since being clever did not make you a good wife. If you excelled at anything it was seen as a mild perversion but Theo was stunningly oblivious to that. Not many people liked her at first. She came to the class in the middle of term. She’d developed earlier than the other girls and had foreign parents, New Zealanders, who’d made their money only recently, and not nearly enough. But through force of personality she turned her fortune round and was made a prefect, as were you.

Don’t get too excited, she told you, practically everyone’s been made one. They’ve only done it because they forgot to educate us—it’s something to put on our CVs.

She was expelled for writing to the Pope, explaining to him why the rhythm method of contraception, for a lot of girls, just didn’t work. (She’d learnt this lesson from her older sister, who’d had an abortion in secret.) Her mistake was to sign the letter with the name of a blond classmate who was going to be a model when she grew up and was promised a car, by her father, if she stopped biting her nails. And was extremely accomplished at looking down on you both. The scandal made Theo a heroine-in-exile but she always remained supremely faithful to you, the lady-in-waiting who’d fallen in love with her first.

Here, in Marrakech, you just wish your friend were as happy as you for you want others to be joyous, to bring them joy, you get such a deep satisfaction from that. You’d love to have Theo here, to cheer her up; it’d be someone to see the sights with while Cole was off by himself. You’re always doing small kindnesses; your grandmother told you never to suppress a kind thought and you always try not to. You snap a shot of a snake man in the square and he rushes towards you, hustling for coins and waving his snakes and you squeal away from him, pulling Cole with you. You must tell her.

Lesson 14 (#ulink_f55ff301-5156-5a21-abc2-4e3857e1c863)

be respectable girls, all of you

Dinner’s dared in the square on rough wooden benches at a smoky stall. Cole and you pick at the couscous but ignore the gnarled-looking meat on kebabs and gritty salad, and have your photo taken as proof of your courage. Cole’s tetchy and irritable and wants to get back to the too-quiet hotel but you feel like you’re at the centre of a vast meeting place of African tribes from the south and Arabs from the north and Berber villagers from the mountains and you hold your head high and drink in the smells and heat and smoke. All these wondrous people! You look across at your husband and stroke his arm, his thin, sensual wrist, and there’s a stirring of desire: you want him, really want him, in that way, in this crowded place. You do nothing but hold your lips to his skin in the clearing behind his ear and breathe in. It’s usually enough, some small gesture like this, just to touch him, to inhale him, to remind you of what you’ve got.

But here, now, something dormant within you is stretching awake, is arching its back. You think of the hotel room and the expanse of the bed. For just a fleeting moment you imagine yourself naked with your legs wide and several anonymous, assessing men and their hands running over you. You imagine being filmed, being bought.

You smile at Cole.

What are you thinking, he asks.

Nothing, you murmur.

Lesson 15 (#ulink_9e3b712e-1ef4-5de2-a11e-ea3ea7b82fd7)

there are few wives who do not heartily desire a child

As you laze on your deckchairs a heavily pregnant woman strides to the swimming pool like a galleon in full sail, robust and proud and complete. You’ll be trying for a baby soon, once the first year of marriage is done.

Let’s just enjoy ourselves for a while, Cole has said.

But thank goodness a pregnancy is secure in the plans. Man, house, child: such happiness is obscene in one person, isn’t it? There’s such an audacity in the joy you now feel. How could anyone bear you? You glance across at Cole: he looked too young for so long, not fully formed, but now, in his late thirties, when a lot of his peers are losing hair and gaining weight, it’s all starting to work. He’d been in a state of arrested adolescence but now he’s filled out and he’s handsome, at last. He has the potential to age into magnificence and you’re only just seeing it.

Shouldn’t it be wearing off, this fullness in your heart fit to burst? When’s it meant to wilt? You throw down your Vogue and place your body on Cole’s, belly to belly, and breathe in his skin like a mother does with a child. Will that scent ever sour for you? You can’t imagine how. He pushes you off, mock grumpy, and slaps you on the bum. You shriek and settle again on your lounger. A young waiter walks by. You narrow your eyes like a cat and laze your arms over your head and tell Cole that if you’re not treated properly it’s the waiter you’ll be marrying next.

Yeah, and all he’ll have to do to get rid of you is say I divorce thee three times. I wish it were that easy for me.

You laugh; you’re filled up with joy, it’s all bubbling out. The pregnant woman steps out of the pool. People have begun asking when Cole and you are going to start a family and your husband always replies that he’ll have a child when he considers himself grown-up, and God knows when that will be. You tell them soon.

All women must want children eventually, you’re sure, that furious need is deep in their bones, you don’t quite believe any woman who says she doesn’t. The urge has begun to harangue you as your thirties march on, it’s an animal instinct grown bold. Your heart will now tighten whenever you see the imprint of a friend in her child’s face. It’s something that’s in danger of overtaking your life, the want.

Lesson 16 (#ulink_6f6117bd-5638-5752-9db9-47348015f25c)

all nature is lovely and worthy of our reverent study

On a day trip to the Atlas Mountains you hold your head out the car window, to the sky, the scent of eucalyptus on the baked breeze. Cole reads the Herald Tribune and dozes and snaps awake.

He works extremely hard as a picture restorer, specialising in paintings from the fifteenth to the nineteenth centuries. He now travels the globe, preparing condition reports for paintings to be sold and working on site, for since September eleventh the insurance premiums have skyrocketed and it’s often cheaper to fly the restorer to the job. Cole’s days are long but the rewards are great—you no longer have to work. Indolence is something you’ve always wanted to try and this is your second month of doing nothing. Cole encouraged you to quit your job as a lecturer in journalism at City University; he’d bulldozed your trepidation with his enthusiasm. Redundancies were on offer and the sum cleared the mortgage for you both. None of your colleagues wanted you to go; you were a stabilising presence in a temperamental faculty, you kept your head down, worked hard. But you’d been worn thin by years of teaching, the relentless routine of work eat sleep and little else, it had become like a net dragging you down. Theo said you’d been so noble, so selfless as a teacher that it was bound to take its toll. You didn’t tell her it felt cowardly that you’d never actually left university and entered the real world; you just teased that she was a teacher also and every bit as noble as yourself.

God no, I do my job purely for me and no one else. It’s utterly selfish what I get from it.

And what, my dear, is that?

This secret thrill, she grinned, as my clients tell me all their deepest, darkest thoughts.

Your job had stopped being gratifying in any way and you delight in the strange feeling of satisfaction from doing this new wifely life well. You weren’t expecting your days to be swallowed by so many mundanities but you’re oddly enjoying, for the moment, cooking fiddly Sunday meals on week nights and painting the kitchen and sorting through clothes. The days gallop by even though you know that boredom and a loss of esteem could one day yap at your heels. But not now, not yet.

You have little left in the way of savings but Cole pays you an allowance of eight hundred pounds a month. It’s meant a subtle change: he now has a licence to expect darned socks and home-made puddings, to comment a touch too often on your rounded stomach or occasional spots. But his small cruelties are a small price to pay for the luxury of resting. He’s giving you something you’ve never had before: a chance to recuperate and to work out what you want to do with the rest of your life. You’ve been so tight and controlled for so long, always on time and everything just so. During the first month of unemployment you gulped sleep and suspect it’s years of exhaustion catching up on you, all the trying to please, the never being able to say no. Anyway, Cole’s teasing is done in a silly, childlike way and you never mind very much.

On this day trip to the Atlas Mountains he’s here under protest, he wants to go back. He hates activity and the outdoors of any sort, he pretends to be so fusty and curmudgeonly, at such a young age, but you find it adorable, he makes you laugh so much. And there’s an intriguing flip side to his crustiness, the little boy who watches Star Trek and buys Coco Pops. You love the kid in the T-shirt under the Italian suits; you’re the only one, you suspect, who knows anything of it.

On the narrow dirt road the car winds and slows and you want to jump out and whip off your shoes and feel the ochre as soft as talcum powder claiming your feet. You know deep in your bones this type of land, for you visited places not dissimilar, with your mother, when you were young. The Sahara is just over the mountains, the desert of smoking sand and tall skies.

It’s a desert the colour of wheat, says Muli, the driver and guide.

How lovely, and you clap your heavily hennaed hands. The sight of them entrances you. You must take us, Muli, you say.

Cole glances across.

Next time.

You smile and lick your husband under the ear, like a puppy, he’s so funny, it’s all a game, and you’re filled like a glass with love for him, to the brim.

Lesson 17 (#ulink_271d4550-7b93-5e57-9ae3-2ccf423b6462)

the duty of girls is to be neat and tidy

Cole more often than not dislikes fingers touching his bare skin, he’ll flinch at contact without warning. Your fingertips are always cold: in winter when you want to touch him you’ll warm your fingers beforehand on the hot-water bottle, he insists.

Cole’s life is very neat. He re-irons his shirts after the cleaning lady has, shines his shoes every Sunday night, leaves for work promptly at eight fifteen, jumps to the bathroom soon after sex to mop up the spillage.

There are some things you suspect Cole prefers to making love. Like his head being scratched so hard that flakes of skin gather under your nails, which you detest. And having the skin of his back stroked with a comb like a soft rake through soil, reaping goose bumps. And resting his head on the saddle of your back as you lie on your stomach in a summer park.

And going down on him. This, only this, is guaranteed to make him come. Sometimes you go down on him just to get it all over with quickly. Cole pushes your head on to him as far as he can and then a little further, and when you bob up for air he measures with his thumb and finger how far you’ve gone and duly you marvel, the good wife, and bob down again. You often gag, or have to break the rhythm to come up for air, your jaw always aches, it goes on too long. You hate the taste of sperm, you recoil from it, like a tongue on cold metal in winter.

Go home and give him one, Theo said once, after a cinema night. The poor thing, it’s been so long.

God no, please, not that.

If you give them blow jobs they love you for life.

But it’s such a chore.

I see it as a challenge.

You took Theo’s advice: Cole told you, when it was done, that he couldn’t wait for the next movie night with your mate.

Calm down, you laughed, and rolled over and went to sleep.

It wasn’t always like this. In the early days you’d make love almost every single night. Cole would sing and dance around in his underwear and be completely stupid before he dived into bed. Have you laughing so much that it hurt. You’d always be completely naked down to the removal of watches, there was a gentle courtesy to that. You’d have sex, daringly for you both, in sleeper carriages from London to Cornwall, as giggly as teenagers as you tried to be quiet for the children next door. Or in your teenage bed that your mother has kept, with Cole’s hand clamped on your mouth to keep you quiet. You cried tears of happiness and he kissed them up, his palms muffing your cheeks and you still have, pocketed in your memory, the tenderness in his touch.

But those moments, now, seem like scenes from a movie; not quite real. The woman in them is removed, someone else. This is real, now: you’ve shut down, there are other things you’d rather do. It’s such a bother removing all your clothes and finding time to do it and making sure you smell sweet and clean. It never seems to be the best time, for both of you at once, there’s always something that’s not quite right. Either you’re not in the mood or Cole isn’t and it’s become easy to make an excuse. You both, it seems, would prefer to be reading newspapers, or watching TV, or sleeping. Most of all that.

Cole doesn’t protest too much. The marriage is about something else. He’s kind, is always doing astonishingly kind things, it’s as if he’s binding you to him with kindness. There are subscriptions to favourite, frivolous magazines, unexpected cups of tea, frog-marching you to bed when you’re overtired, the gift of a new book that he’s wedged somewhere in the bookshelf and says you must find. All these little gestures force you into kindness too, kindness begets kindness, the marriage is almost a competition of kindness. So there’s scratching his head so hard that flakes of skin gather under your nails, and acquiescence in bed, and blow jobs. These small kindnesses buy Cole time alone, away from you, away from the world, within his halo of light in front of the television or in the bathroom or studio until late. You don’t mind the alone either, you need it too, to breathe again, to uncurl.

It’s a strange beast, your marriage, it’s irrational, but it works. It’s traditional, and how judgemental your mother is of that. She was divorced young and raised you by herself until you were sent to boarding school. She instilled in you that you should never rely on a man; you had to be financially independent, you mustn’t succumb. But it’s a relief, to be honest, this surrendering of the feminist wariness. It feels naughty and delicious and indulgent, like wearing a bit of fur.

Lesson 18 (#ulink_29616e4b-dc16-5a90-84eb-bfae8cff3f47)

sound sleep is a condition essential to good health

One a.m. You’re reading the first Harry Potter. It’s Cole’s, you found it among the rest of his holiday books, weighty tomes on history and art. You’re in the armchair by the french doors to the balcony, a leg dangling over the arm.

A spider of sweat slips down your torso. You’d love to feel a storm breaking the back of the heat, to hear it rumbling in the floorboards and smell it in the lightning. You look across at Cole, sleeping on the sheet with his shoes still on. You slip them off like a mother with a toddler and roll him over to remove his shirt; he’s stirring, reaching for you, scrabbling at your skirt. Sssh, you tell him, and you hold your lips to the dip in the back of his neck. You don’t want him properly waking, don’t want anything to start. For you’ve begun menstruating and the blood’s leaking out of you, hot, and you know he’d be appalled by this. He doesn’t like blood.

Cole usually sleeps soundly, the sleep of a man content. He’s not a snorer, you could never marry him if he were. How could you secure a decent night’s sleep with a man who snores? Cole laughed when you told him this on your wedding night; it’s the only reason why I married you, you said. Cole responded that if he did snore he’d borrow one of your bras and put tennis balls in it and wear it back to front, to stop him from sleeping on his back, that’s how much he loved you.

One thing you could never tell your husband is that his coming takes too long. And that his penis seems bent, and often goes soft in you, as if it’s thinking of something else. And that the reason he got blow jobs all the time, when the relationship was young, was to butter him up. And to make him think you were someone else.

Lesson 19 (#ulink_2883dcac-016f-5d24-93d0-ce7bf7f20541)

good habits are best learnt in youth

You sit by the concierge desk in the vast almost empty lobby while Cole changes some cash. A man passes, he wears the sun in his face, he’s a boy really, a decade or so younger than you and he smiles right into your eyes and you feel something you haven’t for years: it’s to do with university parties with bathtubs of alcohol and the smell of hamburgers on fingers and beer in a kiss. You should have been disgusted by all that but you weren’t. You’d be wet so quick; to get their clothes off, to have their weight upon you, to be rammed against a wall with your leg curled up.

You’re singing inside as you saunter back with Cole to your room of fresh roses. Every second day new roses await you, they’re never allowed to wilt in the heat. Inside, you kiss your husband fully on the mouth, surprising yourself as much as him with the ferocity of it. You taste him, drink him, and you so rarely do that. He kisses you back in his way, as if inside your mouth is the most exquisite, expensive morsel imaginable. You don’t like him kissing you on the lips very much; often you secretly wipe away the track that’s left by his mouth.

The last time Cole and you had made love, before this holiday, was your wedding night. The vintage Bugatti you’d borrowed wouldn’t start and all Cole’s distant relatives had to be met and Theo got too drunk. Cole and you had ended up giddy and sweaty back at your hotel room, ravenous, with just a Mars Bar from the mini bar to share between you. Still, there was a new sweetness to making love, even though it was soaked in a sudden tiredness and a little clumsy, and you didn’t get far: almost an afterthought to the end of a long day. It didn’t matter that the sex on that night wasn’t the best you’d ever had, for you’d been together for so long before that.

The honeymoon had been delayed because Cole was always accepting another commission and getting tied up. He finally found a window of escape four months after you’d tied the knot. You didn’t complain, you appreciate his attachment to his job, it’s so solid, so dependable: he’ll never let you down.

He’s never given you an orgasm. He assumes he has. You’re a good actress—a lot of women are, you suspect. You know what you’re supposed to do, the sounds you make and the arching of the back and the clenched face: it’s in a thousand movies to mimic, it’s everywhere but your own life. You’ve never had an orgasm by yourself or with any man that you’ve slept with. You’ve lied to every one of them that you have, that it’s worked. You’re curious about them but not curious enough. It’s like a language you don’t speak; you know you should make an attempt at it but you can get by perfectly happily without it, it’s not going to impede your life. You’re in your mid-thirties and have never even looked down there, at yourself. Cole could tell you about it if you were curious enough, but the intimacies of your own body are for someone else, you feel, not yourself.

Lesson 20 (#ulink_22e2affd-c061-5ba3-a519-0feb27342068)

to be delicate is considered by some ignorant people as an enviable distinction

Gin and tonics by the pool.

Cole reads aloud an extract from the historical section of the Herald Tribune. A woman in New Jersey in 1925, a mother of eight, was inspired by Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves to heat a cauldron of olive oil and pour it over her sleeping husband.

Oil, Lovely, can you believe it, oil.

But you’re hardly listening for you’re thinking of the man in the lobby and your very first fuck, with the TV show The Young Ones flicking mute in the background and how tight and dry and uncomfortable it had been. You’re thinking of the boy’s distasteful triumph afterwards, with his mates, and the TV turned up too loud. You’re thinking of Theo—but it all sounds so…squalid – as she dragged on her cigarette with uncommon ferocity. How strange you can’t recall her own account of her loss of virginity. It’s something you can’t remember talking about, in fact, with any of your girlfriends. Were a lot of the experiences as disappointing as yours, is that why they’re never discussed; do you all want to move on? You’re remembering that Theo had put copper lipstick in her hair back then to highlight the colour because she’d read it in a magazine but you’re not remembering, for the life of you, the boy’s name.

You’re thinking of Sean, the student Theo and you shared a flat with. He was still hopelessly, consumingly in love with an older woman who’d broken his heart and he never made an effort to become a part of the household; his days were spent moping, alone. One day he disappeared. The police came to your front door a week later and told you that he’d taken a train to Scotland and hitched to a remote beach where his lover had her holiday cottage and he’d swum out to sea and had never swum back. You were haunted by that for years afterwards, the wild, jagged love that Sean had, and of the outside leaking into him, the water swelling his flesh and lapping at his bones. He was brave in a way, to do that, you’d thought that for so long. Now, you just wish he’d grown up and known other women, that he’d journeyed to a point in his life where he could look back and laugh.

Lesson 21 (#ulink_1d7bff3c-38a8-5b0a-9e4c-e78af998d57f)

exercise is quite as requisite for girls as it is for lions and tigers

Muli takes you to Yves St Laurent’s public garden, sheltered and cool within high walls. The noise of Marrakech falls away as you enter. This would be Theo’s kind of place. It’s spiky and seductive with cacti and palms and splashes of blue paint and bougainvillaea-pink cascading over walls. You take a photo for her. You’ll tuck it in an envelope, with some rose petals from the room.

You escape the press of the heat in the winding coolness of the market alleyways. You love the souks, the instrument shop that could have existed several hundred years ago next to a shop selling live iguanas next to one crammed with Sylvester Stallone T-shirts. Love the donkeys in the alleys and skinny cats and red Coca-Cola signs in Arabic, the attacking light, the dust heavy on your skin and clotting your hair, the mountains rimming the city, the talking dark, the crickets and dogs and frogs. There’s the call to prayers and Muli excuses himself for ten minutes. You love the pervasiveness of religion in this place, how the chant wakes you in darkness and plots your day. Cole admires the colours of the city, the vaulting blue of the sky and rich ochres and pinks but he can’t bear the dust and the cram and the heat, he’s very loud about all that, he’s not enjoying being dragged around.

Your confidence is softly leaking as a wife. You’d never tell him. That you sometimes feel as if all the men through your life, the lovers, colleagues, bosses, with their clamour and demand, have been rubbing you out.

Cole’s in another meeting. He’s resorted to watching Pokemon cartoons in French, a language he doesn’t understand, for the English stations carry just rolling news and the stories aren’t changing enough. There are also local news broadcasts with items that run for twenty minutes and seem to be made up entirely of long shots of the King on parade or men in suits on low chairs. The news anchor’s young, with the most beautiful eyes, it’s as if they have kohl round them. You wonder what he’d be like as a lover, if he’d be different. You’ve heard that Muslim women are shaved and all at once you feel a soft tugging between your legs, thinking of that; and of being robed, for your husband’s eyes only. Muli told you both that no one’s ever laid eyes on the Queen, she’s not seen in public, is hidden.

I like that, Cole had laughed.

And was playfully hit.

Later, over gin and tonics in the piano bar Cole holds his cheek to yours and whispers that he wants to lock you up and never allow you out and he wants another wife as well as you, whom you’ll have to sleep with, while he’s watching, and your hands cup his face: You are so predictable, McCain, you chuckle and kiss him gently on each cheek and it stirs something in you, memories of Edinburgh and rolling off a bed and making love with a hand clamped across your mouth.

Lesson 22 (#ulink_d4d38c09-d3ec-5615-a2bc-172c363e6fa4)

making a noise is of itself healthy, when no one is inconvenienced or annoyed by it

Sometimes you wonder if your husband really likes women. He speaks dismissively of your girlfriends and female colleagues, doesn’t want a wife who’s pushy or loud, gets annoyed if you talk to your girlfriends too boomingly on the phone and winces if you shriek. He doesn’t like excesses in women of any kind. He niggles when you don’t dry yourself thoroughly after the bath, says it’s so moist down there you must be growing a jungle. His genitals smell unoffensive, milder than your own.

Cole’s parents are very together, very solidly, defensively middle class. They don’t think you’ll look after their son well enough. His mother communicates all her vigour through her cooking and is horrified you’ve only recently learnt how to do a roast. She sends correspondence, persistently, to Mr and Mrs C. McCain despite you telling her you haven’t changed your name.

Cole thinks your family is eccentric. It used to be delightfully, exotically so, until he got to know them. Your great-great-grandfather made his fortune importing tea from India and your father’s cousin frittered away the remains of the family wealth on drinking and drugs. Your father was from the poor side of the family and was meant to work but never got around to it. He was charming and roguish, all blond hair and cheekbones in his youth, until drink sapped his looks. You adored him because you never saw him enough. He survived by periodically cashing in shares of the family business until he died, when you were nineteen, of drunkenness and poverty and a spineless life.

It broke your heart. Seeing him during your teenage years seemed to consist, almost entirely, of a series of journeys to and from school. He’d pick you up in his old black Mercedes that looked like a relic from some totalitarian regime, and drive and drive, picking the smallest, most winding country lanes to get you to London. It was only in the car that you ever seemed to talk, because his girlfriend, Karen, always made it difficult when you were in their flat; butting into your time and crying over God knows what. Your father’s affection was reserved for the road or the odd moments when Karen was out of the room, when he’d lean across and whisper I love you as if it was a secret between you. His voice, now, is what you remember most.

Your parents’ marriage lasted four months. Your mother left its volatility two weeks after you were conceived, left it to hunt for fossils. She’d studied palaeontology at university but had halted the career to be the wife. Your father refused to live anywhere but London even though your mother was an asthmatic who dreamt of a light that would sing in her lungs. Work provided that, and so as a child you lived in a succession of places that were singed by the sky until the courts intervened, at your father’s orders (the only thing he ever managed to do in his life, snapped your mother, more than once) and you were sent back to England, the land of soft days, and, when you grew up, orgasmless fucks.

People who know nothing of your family find it fascinating and charming and extreme but Cole now knows the truth, that little of that extremity has rubbed off on you; it’s only reinforced your own caution. You’ve had to be sensible, had to make a living amid all the chaos.

Cole says your mother is bruised by bitterness, that she’s menopausal and mad and he fears you’ll turn into her. He doesn’t enjoy visiting her cottage on the north Yorkshire coast, an area that’s rich in the fossils of marine reptiles and fish. It’s wilfully remote and she’s hardly ever home because she’s always off on a dig. He doesn’t enjoy the way she absently picks up his toothbrush to scrub at a piece of sandstone she’s working on (or perhaps deliberately, but you could never tell Cole that) and clutters her house with old bones and rocks. Cole finds her selfish and sloppy: she’s the type of person who washes up in lukewarm water, he said once, and you laughed at the time but didn’t forget.

You’ve tried hard to be nestled within Cole’s family, to be the good wife, but they never trust you enough. Cole doesn’t understand that a stable family’s one of the most desirable things of all when you’ve come from a fractured childhood, doesn’t understand the terrible, Grand Canyon loneliness you feel within his. But you have each other, a sure path, a certainty. Home fills his heart when Cole’s on the road, he just longs for the vivid tranquillity of your flat. It’s his sanctuary from all the anxiety of the world: paintings too traumatised to repair and canny fakes and deadlines impossible to meet. You’re careful not to butt anything too unsettling into his stressful life for you’re so lucky, you know that. Your husband’s a modern man who’s generous and thoughtful, who cooks and cleans; who’s devoted, Theo says, you’re one of the few couples who are truly happy. And she should know. She’s seen a lot of couples. When the women bring their men for coaching sessions to her studio she literally gets into the bed with them both, armed with a pair of latex gloves and a vibrator.

I’d love to have a session with you guys, she’s said, as if she wants to bottle the secrets of why your relationship works.

God no, you’d replied, laughing, appalled. You’ve never been able to shit in a public loo if another woman was in the room, let alone have sex. When you shared a shower with Theo, at the age of thirteen, it was so excruciating that you vowed you’d never get yourself into such a situation again. You could strip off at a doctor’s surgery or in a public gym, where you were utterly anonymous, but it was another matter entirely with someone you knew, and so well.

No one, though, has any idea of the churn of a secret life. Your desire to crash catastrophe into your world is like a tugging at your skirt. But only sometimes, and then it’s gone. With the offer of a bath, or a cup of tea, or the dishes done.

Lesson 23 (#ulink_695f2ede-4b57-532d-9828-4db92bd30888)

the importance of needlework and knitting

You have a book given to you by your grandfather that’s a delicious catalogue of unseemly thoughts:

That a wife should take another man if her husband is disappointing in the sack.

That a woman’s badness is better than a man’s goodness.

That women are more valiant than men.

That Adam was more sinful than Eve.

It was written anonymously, in 1603. It’s scarcely bigger than the palm of your hand. The paper is made of rag, not wood pulp, and the pages crackle with brittleness as they’re turned. You love that sound, it’s like the first lickings of a flame taking hold. The book is tided A Treatise proveinge by sundrie reasons a Woemans worth and its words were contained once by two little locks that at some point have been snapped off. It smells of confinement and secret things.

You imagine a chaste and good wife writing secretly, gleefully, late at night and in the long hours of the afternoon. A beautiful, decorative border of red and black ink hems each page. It’s a fascinating, disobedient labour of love. You wear cotton gloves to open it. You’ll never sell it.

It’s been in the family for generations. A rumour persists that the author’s skeleton was found in some cupboard under a staircase, that she’d been locked into it after her husband discovered her book. Your father told you stories of her scrabbling at a door and crying out and of her despairing nail marks gouged into the wood, but you suspect the reality is much more prosaic: that your great-grandfather acquired the book at auction, as a curiosity, and it may even have been written by a man, as an enigmatic joke.

Cole calls it The Heirloom, or alternatively, The Scary Book. He teases that he’ll toss it in the bin if you’re naughty, or lock you in the cupboard and never let you out. You love all this banter between you; he makes you laugh so much. You never see any irony in it. He calls the bits and pieces of your father’s furniture dotted about the flat The Ruins. And you, affectionately, The Old Boot. It never fails to get a rise out of you; Cole loves seeing that.

Lesson 24 (#ulink_8c16855e-8e1a-5043-b1f0-2c01efe7fb06)

the chief causes of the weak health of women are silence, stillness and stays; therefore learn to sing and dance, and never wear tight stays

The hanging sky. The air smelling of the sea. You don’t even need an umbrella as you lie on a sunlounger next to the pool. The breeze blowing in from the desert plays havoc with your Herald Tribune and you give up and watch the people around you, you’re more interested in the women’s bodies than the men’s, all women are, Theo has said and she’s right. You remember exactly her body when she was sixteen, the short waist and long legs and moles on her chest, and yet you can hardly remember the men you’ve slept with, any of them. The names or the bodies, only the faces, just, and the shape, vaguely, of penises, whether they were long, or too thick—God, you dreaded that, the grate of it.

The attendant presents you with a gin and tonic on a silver tray and you look around, startled. The man from the lobby smiles his beautiful boy smile from a distant sunlounger and you lower your head and do nothing more, don’t drink, don’t look, you’re confused and you know that Theo’d be cross at this, a missed opportunity.

Theo. Such a pirate of a woman, with a different energy to her. She’s thirsty and needs to drink, it’s in the way she walks and listens and leans and talks. She’s a woman who overlives, she has so much life in her, it shines under her skin. Does that mean you underlive? Your heart dips with panic as if a cloud has skimmed across it.

You look across to the man on the sunlounger now reading his Tribune and tilt back your head and close your eyes. You’re living your days at the moment how a sheep grazes, meandering, not engaged with anything much. And yet, and yet, you’d never wish for Theo’s kind of existence. She’s so free, so answerable to no one that she’s lost.

The sky deepens, bathers pack up their suntan lotion and one by one leave, the baked breeze stiffens and umbrellas are snapped down for fear they’ll cartwheel away. You slip into the pool. The water’s ruffled like corrugated iron. You’re the only one in it and you slide through the coolness and strike out for the first time in years, feel unused muscles creaking into working order and think of your mother and her strong, confident hands and the ribbons of water when you were seven. You’ve no family consistently around you now, your friends have become your closest relations: Cole, of course, and Theo, your sister of sorts, although at times there’s the intensity of lovers between you.

It’s her birthday today, you must call.

You smile as you pull your body through the water and at the end of the pool look up to great plumes of ochre dust blown in from the desert; it’s as if the dusk is being hurried centre stage. The attendants move with crisp deliberation now, clearing towels and cushions from chairs. Most people have gone. Palm trees toss their branches like the manes of recalcitrant ponies, twigs and leaves blow into the pool and you climb out of the water at the first fat splats. You smell the earth opening up as if it’s breathing, feel the thundery day sparking you alive and you lift your chin to it and inhale deep and gather up, reluctantly, your sun gear. You pass the man from the lobby, still reading valiantly. He looks up at you.

You don’t look at him. You walk inside, to your husband, a fluttery anticipation within you.

Lesson 25 (#ulink_35ef62cd-5ce7-5b1e-b554-e5fab74836e4)

lending is, as a rule, the greatest unkindness we can be guilty of, unless we can give

The elderly man who looks after the roses lets you into the room, bowing and smiling his gentle smile. He’s presented you, gallantly, with a single stem and you’ve accepted it graciously; it’s a game played with some seriousness. The petals are deep red, almost black, and you plunge your nose into their oddness: it’s a wild plump garden scent from your childhood, not the tight manufactured whiff from the buds you buy at the supermarket. You enter the room soundlessly, you’ll surprise Cole, he’ll throw you on the bed and make you laugh and kiss you in his special way and you’ll melt, succumb, even though you’re still menstruating. Sexy sex, hmm, grubby, spontaneous, impolite kind of sex, you haven’t done that for years and all of a sudden it seems necessary. The room’s dim from the darkening sky and you can taste the thunder outside and lift your chin to it. Cole’s on the phone. You’re cross, he shouldn’t be doing any work during this trip, he promised.

I can’t wait to get out of here, it’s driving me crazy, the heat, and he says this in his special voice, your voice, but there’s a playfulness, a lightness, it’s a tone you haven’t heard for so long. All she wants to do is run off to the markets and have rides in those fucking carts, I can’t stand it, I get so bored, I just want to relax. He pauses. Diz, Diz, no, you can’t. He chuckles. Yeah, me too. I’ll see you soon, thank God.

Lesson 26 (#ulink_39f0eee8-1a60-5a03-9f2b-e6e692334bb8)

air ventilation oxygen

You’re very still. You walk past Cole without looking at him. You walk through the french doors, to the veranda, and sit, very carefully, on the wicker chair.

Your thudding heart, your thudding heart.

You sit for a very long time, soundlessly, into the rich silence after the storm. At the end of it the sun feebles out and nothing has cooled down, nothing, it is as hot as it ever was.

II (#ulink_80a34184-ae96-5bec-b43e-33ed1425f22d)

My soul waiteth on thou more than they that watch for the morning,

I say more than they that watch for the morning.

Psalm 130

Lesson 27 (#ulink_2929b38f-0006-5213-a02d-a27a76a63663)

there ought to be no cesspool attached to the dwelling

The Monday after the return from Marrakech. A cafe in Soho, alone. An old London chophouse selling beans on toast and Tetley’s tea in stainless-steel pots, the menu padded and plastic covered. Reading the paper but not.

Like you are skinned.

I can’t explain it, he has said, reddening, every time. When you’ve asked him again and again. You’re overreacting, he has said. She’s a friend, our friend, we’d just have a drink now and then. And then he stops.

As if what he wants to say can never be said, as if it will never be prised out. But you will not let up.

Just a friend. Uh huh.

You sit back at his words, you fold your arms. At his explanations that are scattered bits of bone, that are never enough.

You haunt the cafe in Soho. Want to crawl away from the world, curl up; want to shrink from the summery lightness in the air, the flirty pink on the girls in the streets.

Within this God-tossed time he’s never stopped telling you he loves you but you’ve no desire to listen any more. For the relationship has been doused in a cold shower and you are chilled to the bone with the shock.

Just a friend. Uh huh.

You will not let up.

Now it’s a week since you’ve known; now two. Everything is changed and nothing is changed, you’re reading the paper but not. You prefer this cafe in Soho over the American coffee chains that seem of late to be everywhere, despite Cole’s certain horror at the choice. Before, you’d let his likes and dislikes shape the movement of your day, even when he wasn’t with you. But you’re disobedient often now, in little ways. For realisation of the affair has snapped upon you as fast as a rabbit trap, and you are exiled from your marriage and home and life.

The elderly man behind the till senses something of all this; he smiles warmly in greeting, now, and hands you your cup of tea without waiting to be asked.

We’d. just. have, a drink, now. and. then. All right?

I don’t believe you. I’m sorry, I can’t.

It’s the truth, I am so sick of telling you that.

I don’t believe you. I can’t.

Your hands hover, frozen, by your head. Your fingers are clawed, your knuckles are bone-white. You have turned into someone else. You do not recognise the voice.

Day after day you shelter in this cafe in London’s red light district. It’s a small indication of something that’s burst within you. You’re not sure why you’ve picked this place, you never go to cafes or restaurants by yourself, it’s too exposing. All you know is that the two people closest to you have gone from your heart, it’s flinched shut. And it’s only as you spread your newspaper and pour the milk into your tea that you feel the tin foil ball, tight within you, unfurling. No one would guess just by looking at you, the quiet, suburban housewife, that recently in a hotel room in Marrakech your entire future had been crushed by a single blow from a rifle butt.

And all that’s left is rawness, too deep for tears.

She’s a friend, just a friend, it’s all he can ever say and in this Soho cafe, the third week of your purgatory, your teacup is slammed down. So hard, the saucer cracks.

Lesson 28 (#ulink_f3d70df5-2fbd-5a99-85c6-60f8e5076948)

disease is the punishment of outraged nature

A month after your return from Marrakech. A stagnation sludges up. You’re not bored or angry but stopped; nothing engages, nothing interests, you’re at a loss over what to do next, with the next hour and with all the days of your life. Sleep is the short-term solution. London’s good for that. Its light is milky, filtered, unlike the light from your childhood that stole through the shutters in bold blocks in the morning, nudging you awake and pushing you out. The sky in London is like the water-bowed ceiling of an old house and you doze whole mornings away now and on waking there’s a panicky sickness in your gut. Then you walk the streets, seeing but not seeing, husked.

Selfridges lures you inside, its sleek promise. You haven’t been here for so long, you used to trawl it with Theo, she’d always have you trying on things you didn’t want. You browse the accessories counters. Buy six rings. Space them out on your fingers, blurring your marital status; your engagement and weddings rings are swamped and you smile as you stretch out your hand.

But then it’s back, his voice. It always comes back. The tone of it as he spoke to her on the phone. It’s not so much the thought of them physically together, it’s the intimacy in his voice. It wasn’t until you overheard it in the hotel room that you realised how long it’d been since you had heard it. And you missed it, violently so.

Your voice.

Your teeth are clenched as you walk to the tube and with effort you soften your jaw and rub at your brow, at a new wrinkle between your eyes. At the end of each night you knead it, your fingertips dipped in the chilly whiteness of Vitamin E cream. Beyond you, the flat ticks. The rooms are dark except for the bedroom. Cole’s away a lot now, working late; that’s his excuse. There’s no light in the hallway to welcome him home. At the end of each night, seated at the dressing table, your fingertips prop your forehead like scaffolding. For it’s the long, long nights that defeat you.

When you are blown out like a candle.

Lesson 29 (#ulink_cfda4735-dfb0-5ed3-8567-ec7cf61f972d)

friends are too scarce to be got rid of on any terms if they be real friends

The buzzer, too loud, blares into your morning. You groan: you’re still in bed. The intercom’s broken, you’ll have to go down three flights of stairs and open the front door to find out who it is; in your old bathrobe, without your face.

Theo. Red lips and red shirt, the colour of blood. On her way to work.

You close the door. This is ridiculous, she says, come on, we need to talk. You lean your hands on the door with your arms outstretched. Can’t we just talk, she pleads. Her knocks become thumps, they vibrate through your palms. You straighten, walk up the stairs, do not look back; your fingers, trembling, at your mouth.

Theo’s betrayal is magnificent, astounding, incomprehensible. It’s her actions you can’t understand, not Cole’s. You always assumed she was the one person you’d have your whole life, not, perhaps, your mother or your husband. She’s a woman, she knows the rules. Men do not. You’re not interested in an excuse, nothing can put it right, for anything she says will be overwhelmed by the violence of the loyalty ruptured and your howling, pummelled heart.

You can’t bear to think of them together. You have no idea how Theo is with a man. How she operates, if she turns into someone else; if she changes her manner and voice. It’s a side of your girlfriends you’ve never intruded upon. All you know is that your husband is trapped in her hungry gravitational pull: his voice told you that.

As you were once. Theo was sloppy with your relationship—never turned up to dinner parties with a bottle of wine, never sent thank you cards, cancelled nights out at the last minute, was often late – but she was always forgiven for she made your hours luminous with the gift of her presence; as soon as you saw her all the irritation would be lost.